1. Introduction

Rock slope destabilization represents a critical geohazard, threatening infrastructure, ecosystems, and human safety [

1,

2,

3]. Landslides, often preceded by gradual deformation, require precise monitoring to detect precursory signals and mitigate catastrophic failure [

4,

5,

6]. Traditional slope stability assessments, which rely on single-parameter thresholds (e.g., displacement or velocity), often overlook the complex interplay of kinematic dynamics and statistical variability inherent in progressive slope movements [

7,

8]. The convergence of high-resolution monitoring (e.g., InSAR, GNSS), advanced numerical simulation (FEM/Material Point Method (MPM)), stochastic analysis (Random Finite Element Method (RFEM)), and machine learning is creating powerful new paradigms for assessing slope stability [

9,

10]. However, a discernible gap exists between regional-scale, susceptibility-focused ML models and site-specific, mechanics-based probabilistic models. While the former excel at regional forecasting [

11], they often lack the granular, physics-based explanation needed for engineering decision-making at a specific mine or infrastructure site. The latter, while mechanically rigorous, usually struggles to efficiently assimilate real-time, high-dimensional monitoring data to update risk forecasts dynamically [

12].

Therefore, the research need is for an analytical model that tightly integrates continuous, high-frequency geodetic monitoring (like GNSS) directly into a dynamic probabilistic stability assessment [

13,

14,

15]. This framework should bridge the gap by using real-time displacement data not just as a posteriori validation but as a primary input to dynamically update parameters (like the FoS or failure probability) within a probabilistic model, thereby reducing epistemic uncertainty and enabling a true “living” risk assessment [

16,

17,

18]. The development and validation of such an integrated monitoring–probabilistic analysis system, as undertaken in the present study, addresses this critical gap in the literature. Such integration would enable the model to capture evolving slope behavior, account for measurement uncertainty through reliability indices, and provide actionable early warning thresholds calibrated to site-specific kinematic signatures. The model should incorporate multi-parameter kinematic metrics alongside statistical descriptors to characterize deformation complexity comprehensively, moving beyond simple threshold exceedance toward probabilistic risk quantification that reflects the stochastic nature of geomechanical processes and monitoring uncertainties.

Recent studies by Mei, Ma [

19] integrate topological data analysis (TDA) with monitoring data, employing persistent homology and quantifying the spatiotemporal evolution of InSAR ground motion fields through persistence diagrams capturing birth and death of topological features, with Wasserstein distance measuring temporal dissimilarity as an instability indicator demonstrating the capability to issue warnings over 100 days before collapse in historical landslides such as Xinmo, showcasing significant potential for proactive hazard management. Lv, Liu [

20] combined GNSS monitoring with crack meters to evaluate earthquake-induced slope stability, highlighting the importance of real-time deformation tracking. Similarly, Ye, Zhu [

21] used field monitoring to analyze reservoir-induced landslides, demonstrating how hydrological triggers and spatiotemporal deformation patterns interrelate. These studies underscore the need for frameworks that synthesize diverse parameters to predict failure mechanisms. Xu, Zhang [

22] developed a system reliability approach using GNSS series data to overcome the limitations of rigid body equilibrium methods, while Mantovani, Bossi [

23] coupled GNSS with numerical modeling to enhance rapid landslide hazard assessment. Such studies validate GNSS’s role in capturing high-resolution kinematic data, including velocity and acceleration, which are critical for detecting precursory signals [

24]. However, existing methods often neglect higher-order derivatives like jerk, which Yang, Lee [

25] identified as an early indicator of instability through seismic response analysis.

Ma and Mei [

26] integrated domain knowledge with spatiotemporal correlations to forecast deformation, while Cohen-Waeber, Bürgmann [

27] employed radar interferometry to identify deformation patterns modulated by precipitation. These approaches align with Yang, Liu [

28], who emphasized rainfall and reservoir water level fluctuations as drivers of slope instability. Despite these strides, most frameworks lack the probabilistic integration of spatiotemporal displacement and reliability metrics, which limits their predictive accuracy. Sadarviana, Bramanto [

24] introduced system reliability analysis for earth-rock dams, while Myint, Matori [

29] proposed stability assessments using GNSS control networks. However, these studies typically prioritize static thresholds over dynamic, time-dependent parameters.

This study aims to develop and validate the CTEDP framework, which integrates high-precision GNSS monitoring with kinematic metrics and multi-parameter reliability indices to enhance early detection of rock slope destabilization. Specifically, the research seeks to: (1) Quantify spatiotemporal deformation patterns, including cumulative displacements, extreme kinematic anomalies, and jerk signatures as precursors to failure. (2) Establish probabilistic thresholds for landslide risk by correlating reliability indices with destabilization trends. (3) Differentiate stable zones from high-risk sectors to guide targeted mitigation strategies. (4) Conduct rigorous sensitivity and multicollinearity analyses to validate the robustness and interdependence of the derived stability indices. The research provides a validated, quantitative methodology for moving beyond threshold-based alerts to a dynamic, probability-driven assessment of slope stability, with direct applications for landslide early warning systems and risk-informed decision-making in geotechnically complex mining environments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Peak Displacement from GNSS Monitoring of Rock Slope Stability

The GNSS monitoring data from mid-November 2024 to early January 2025 reveal spatially variable progressive deformation across the monitored rock slope (

Figure 3). Point 1 exhibits the highest cumulative displacement, reaching approximately 60 mm (mean rate: 0.9 mm/day), with notable acceleration between mid-December and early January. Points 2, 3, and 5 exhibit parallel displacement trends, ranging from 37 to 45 mm, indicating coherent deformation of a substantial portion of the slope. Conversely, Point 4 remains essentially stable (<10 mm), likely representing a reference location or stable zone. The temporal patterns indicate a slope-wide acceleration beginning in mid-December 2024, potentially triggered by changes in precipitation or temperature. Short-term oscillations at Point 1 may reflect diurnal measurement variations or elastic responses of the rock mass. The substantial displacement differential between Point 1 and the other active points suggests localized weakness zones that require targeted stabilization. The parallel trends at Points 2, 3, and 5 indicate a common deformation mechanism, possibly representing a coherent sliding mass. These findings demonstrate progressive slope deformation requiring continued monitoring and potential intervention to mitigate landslide risk. The GNSS effectively captures both spatial heterogeneity and temporal evolution of slope movements, with Point 1’s accelerating displacement warranting particular concern.

Point 1, exhibiting the most critical behavior (cumulative displacement >60 mm with sustained settlement trend), is located directly above a borehole where 10 m of glacial deposits overlie weathered porphyry at the slope crest; the observed progressive deformation reflects gravitational sliding along the glacial deposit–bedrock interface, kinematically released by the Heishuitan Fault (F1), which dips 42–65° NE, creating a daylight condition with the 55–65° eastern slope face. In contrast, Points 2, 4 and 5 show oscillating displacements (±−10–44 mm) without sustained trends, corresponding to their positions where competent hornfels and diorite porphyrite (c′ = 1.58–1.62 MPa, φ′ = 34–35°, GSI = 45–55) provide superior rock mass quality compared to the glacial cover zone (GSI = 30–40); these points undergo elastic flexural response to mining-induced stress redistribution in numerical simulations rather than progressive failure. Point 3, positioned at the eastern–northern slope transition where bedrock is exposed and slope angles decrease to 35–45°, exhibits moderate stability consistent with reduced gravitational driving forces and absence of weak glacial overburden. The differential deformation patterns therefore directly reflect lithological boundaries, structural discontinuity orientations, and variable overburden thickness, with critical instability zones coinciding spatially with the convergence of weak glacial materials, fault-induced kinematic release, and high mining-induced tensile stresses—an interpretation substantiated through systematic correlation of GNSS time-series with borehole stratigraphy, geological cross-sections, and numerical geomechanical models.

3.2. GNSS-Derived Anomalous Rock Slope Velocity Measurements

The peak velocity (

Figure 4) exhibits episodic deformation behavior, with values ranging from near zero to approximately 35 mm/day across the monitoring points. Point 1 shows the most pronounced fluctuations, reaching peak velocities of 30–34.5 mm/day during distinct acceleration episodes in late November and sporadically throughout December. These high-frequency oscillations between elevated and baseline velocities indicate non-continuous, stick–slip deformation rather than steady creep. Points 2, 3, and 5 exhibit similar episodic patterns, characterized by lower peak velocities of 10–18 mm/day, which show a temporal correlation, particularly during late November and December. Point 4 maintains consistently low velocities of less than 5 mm/day, confirming its position within a stable reference zone.

The synchronized acceleration events across multiple points suggest common external triggers, most likely precipitation-induced fluctuations in pore pressure. The deformation mechanism follows a cyclic pattern: infiltration increases pore water pressure along discontinuities and potential shear surfaces, reducing effective stress and frictional resistance according to Mohr–Coulomb failure criteria, thereby triggering temporary displacement acceleration. As pore pressures dissipate through drainage, effective stress recovers, and deformation rates decrease. Background displacement between episodes indicates ongoing gravitational creep and progressive rock mass degradation through micro-fracturing.

The frequency and magnitude of acceleration episodes at Point 1, combined with peak velocities exceeding 30 mm/day, suggest that this location approaches critical stability conditions, with repeated mobilization events progressively weakening the failure surfaces. This represents transitional behavior between stable creep and accelerating pre-failure deformation, indicating an elevated landslide hazard that requires enhanced monitoring and potential stabilization measures.

The reported GNSS-derived velocity measurements from the rock slope monitoring program, when compared against the standardized velocity classification schema established in

Table 1, reveal that the monitored slope exhibits deformation spanning multiple velocity classes. Point 1 demonstrates episodic acceleration events reaching 30–34.5 mm/day (11–13 m/year), placing these episodes within Class 4 (Moderate), characterized by clearly noticeable movement. During quiescent periods, Point 1 velocities decrease to 0.5–2 mm/day (0.18–0.73 m/year), corresponding to Class 2 (Very Slow) or lower Class 3 (Slow) conditions. Points 2, 3, and 5 exhibit peak velocities of 10–18 mm/day (3.7–6.6 m/year) during acceleration phases, placing them within Class 3 (Slow), while background rates remain in Class 2 (Very Slow). Point 4 consistently maintains velocities below 5 mm/day (<1.8 m/year), within Class 1–2 (Extremely Slow to Very Slow).

The critical observation is Point 1’s periodic transition from Very Slow to Moderate velocity classes, indicating episodic behavior that approaches hazardous conditions. The recurrence of Moderate-class accelerations throughout the two months suggests progressive failure, with each cycle incrementally weakening the rock mass through accumulated damage and shear surface degradation. While catastrophic Class 5 (Rapid) velocities have not occurred, the recurring Moderate-class events constitute warning signals of deteriorating stability. The episodic pattern, driven by pore pressure fluctuations, demonstrates susceptibility to environmental triggers and potential for further acceleration under intensified hydrological conditions or upon reaching critical damage thresholds, warranting enhanced monitoring and stabilization interventions.

3.3. GNSS-Derived Acceleration Analysis for Slope Stability Assessment

The peak acceleration (

Figure 5) reveals episodic dynamic loading, with values ranging from near zero to approximately 1.2 mm/day

2. Point 1 exhibits the highest accelerations, reaching 1.15 mm/day

2 in early December with additional events of 0.6–0.7 mm/day

2 in late December and early January. Points 2, 3, and 5 exhibit similar patterns, with peak accelerations ranging from 0.4 to 1.0 mm/day

2, indicating a temporal correlation during late November, early December, and late December. Point 4 maintains consistently low values below 0.2 mm/day

2, confirming its stable reference status.

The acceleration patterns reflect a mechanistic process whereby precipitation or snowmelt triggers rapid increases in pore pressure along discontinuities, abruptly reducing effective stress and causing sudden velocity increases, which are manifested as acceleration spikes. High acceleration magnitudes indicate rapid mobilization when frictional resistance is overcome, while subsequent decay reflects the equilibration process as pore pressures dissipate. The clustering of high-magnitude events at Point 1 demonstrates progressive damage through repeated acceleration cycles that micro-fracture the rock mass, open discontinuities, and degrade asperity contacts along shear surfaces. Each event represents a partial mobilization that accumulates residual damage without full strain relaxation. The temporal distribution indicates intensification from late November to early December, likely corresponding to periods of enhanced precipitation. Persistent acceleration events throughout January, despite possible seasonal drainage improvements, indicate that the slope remains critically stressed, where minor perturbations trigger measurable kinematic responses, warranting continued monitoring and intervention measures.

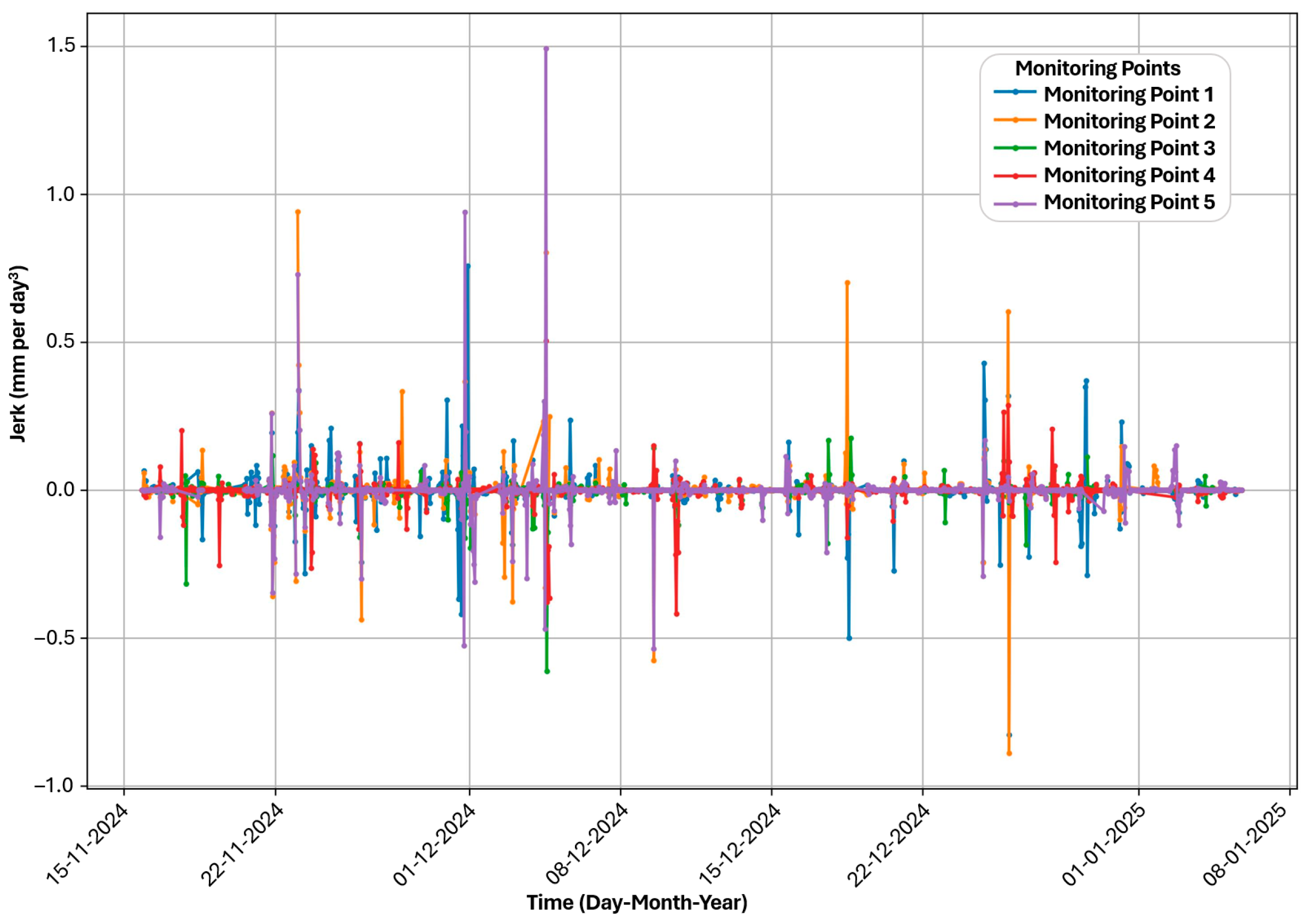

3.4. Analysis of Jerk Values from GNSS Monitoring for Rock Slope Stability Assessment

Figure 6 (rate of change of acceleration or jerk) reveals high-frequency oscillations ranging from −1.0 to +1.5 mm/day

3. Point 5 exhibits the most pronounced spikes reaching 1.5 mm/day

3 in early December and 0.7–1.0 mm/day

3 in late December, while Points 1, 2, and 3 display magnitudes of −0.5 to +1.0 mm/day

3. Point 4 maintains low values within ±0.2 mm/day

3. Episodic clusters occur during late November, early December, and late December through early January, coinciding with periods of elevated acceleration.

The oscillatory pattern reflects dynamic hydrological forcing, where a positive jerk indicates the rapid onset of acceleration from pore pressure increases, reducing effective stress, while a negative jerk represents deceleration as drainage restores frictional resistance. Pore pressure propagation through fracture networks occurs non-uniformly, creating spatiotemporal gradients that induce variable acceleration responses. Water infiltration along discrete pathways causes localized reductions in effective stress, triggering sudden mobilization, followed by lateral drainage and stress redistribution, which induces deceleration.

The elevated jerk at Point 5, despite lower cumulative displacement than at Point 1, suggests proximity to hydraulically active zones with pronounced pore pressure fluctuations. Asymmetry favoring positive jerk indicates mobilization occurs more rapidly than stabilization, consistent with threshold-controlled behavior. Persistent high-frequency oscillations indicate that slope operates in a dynamically unstable regime characterized by continuous micro-scale adjustments, rather than steady-state creep, reflecting the competition between gravitational forces and time-variable frictional resistance modulated by hydrological conditions.

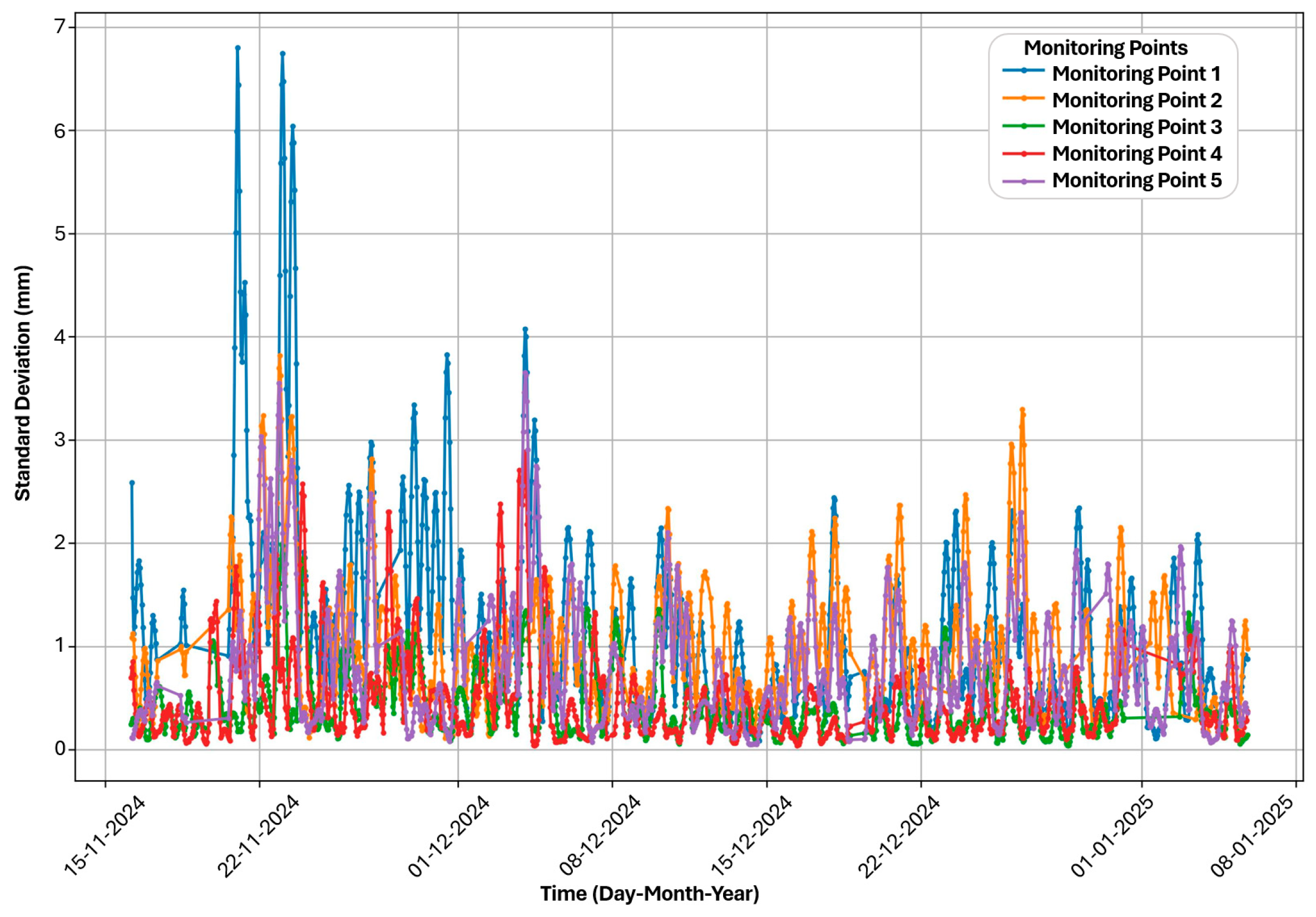

3.5. Analysis of Standard Deviation Values from GNSS Monitoring for Rock Slope Stability Assessment

Figure 7 quantifies measurement uncertainty and short-term variability, ranging from 0.2 to 7.0 mm. Point 1 exhibits the highest values, reaching 6.0–7.0 mm in late November with subsequent peaks of 3.5–4.0 mm in early December and 2.0–2.5 mm thereafter. Points 2, 3, and 5 display standard deviations of 2.0–3.5 mm during peak periods in late November and early December, while Point 4 maintains values below 1.0 mm throughout.

Elevated standard deviations coincide with periods of high velocity and acceleration, indicating increased measurement uncertainty during active deformation. The progressive decrease from late November through January suggests a stabilization of deformation rates or a reduction in short-term displacement variability. The correlation between high standard deviations and acceleration events demonstrates that rapid kinematic changes introduce greater measurement scatter, reflecting genuine physical variability in displacement rates over short intervals rather than purely instrumental noise.

The mechanism involves multiple factors: rapid displacement rates introduce temporal sampling uncertainty as discrete GNSS measurements capture positions during non-uniform motion; atmospheric conditions during precipitation events degrade signal quality through tropospheric delay and multipath effects; and genuine physical variability exists as the slope experiences micro-scale stick-slip behavior and elastic–plastic transitions, creating short-term fluctuations. Elevated standard deviations at Point 1 during peak deformation suggest complex kinematic behavior with heterogeneous displacement fields near zones of concentrated strain. The subsequent reduction, despite continued displacement accumulation, indicates a transition from episodic mobilization to more uniform creep as hydrological conditions stabilize or the slope adjusts to a new stress equilibrium.

3.6. Comparative Analysis of Cumulative Effects Across Monitoring Points in GNSS-Based Rock Slope Stability Assessment

The cumulative effect (

Figure 8) ranges from near-zero to 63 mm. Point 1 exhibits the highest accumulation, increasing from 10 mm to 63 mm (0.87 mm/day), with initial volatility (10–25 mm) during late November, followed by systematic acceleration reaching 30 mm by mid-December, 45 mm by late December, and 60–63 mm in early January. Points 2, 3, and 5 display parallel trajectories converging toward 38–45 mm, showing similar oscillations (5–20 mm) followed by coherent acceleration from mid-December. Point 4 increases to 12 mm and then decreases to near zero, confirming a stable reference status.

The cumulative effect integrates displacement magnitude, velocity, acceleration, and temporal persistence. The mechanism involves gravitational stress-driven displacement modulated by time-variable frictional resistance, where background creep contributes to incremental accumulation through micro-scale displacement, while episodic acceleration events triggered by pore pressure increases generate rapid increases, as effective stress reduction mobilizes larger displacements. Systematic acceleration from mid-December indicates a transition from episodic to continuous deformation, reflecting sustained hydrological forcing or progressive strength degradation.

Point 1’s substantially higher cumulative effect (63 mm versus 38–45 mm, approximately 40% greater) suggests a localized weakness zone or preferential sliding surface, potentially representing the toe region with maximum displacement or concentrated shear strain. Parallel trajectories of Points 2, 3, and 5, maintaining a 2–5 mm separation, indicate coherent block deformation responding uniformly to common mechanisms. A sustained positive gradient through early January without a plateau indicates ongoing progressive deformation, requiring monitoring to assess whether the slope approaches the critical acceleration characteristic of impending failure or maintains sub-critical creep conditions.

3.7. Analysis of Skewness Values from GNSS Monitoring for Rock Slope Stability Assessment

The skewness (

Figure 9) reveals asymmetry in displacement distributions, ranging from approximately −2.5 to +2.5 dimensionless units. All points exhibit high-frequency oscillations between positive and negative values throughout the period, with Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 displaying similar patterns and comparable magnitudes, while Point 4 shows slightly reduced amplitude.

Positive skewness indicates displacement distributions with extended right tails, representing periods where occasional large displacements exceed typical values during episodic acceleration events. Negative skewness represents extended left tails, indicating periods where displacement rates drop below typical values following deceleration. The rapid alternation reflects non-Gaussian, episodic deformation alternating between quasi-static creep and sudden acceleration phases.

The mechanism is related to threshold-controlled slope behavior during stable periods with uniform creep, where distributions approach symmetry (with near-zero skewness). When hydrological triggers elevate pore pressures approaching critical thresholds, occasional large displacement events create positive skewness. Following acceleration events, enhanced drainage and stress redistribution temporarily suppress displacement rates below background levels, generating negative skewness. Persistent oscillations indicate continuous transitions between these states rather than steady-state conditions.

Similar skewness patterns across Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 suggest coherent deformation mechanisms with synchronized responses to common environmental forcing. The absence of systematic trends toward increasingly positive or negative skewness indicates the slope has not entered a persistent acceleration characteristic of imminent failure. Still, it experiences repeated mobilization–stabilization cycles, consistent with a dynamically unstable regime modulated by transient hydrological conditions.

3.8. Analysis of Reliability Indices from GNSS Monitoring of Rock Slope Stability

Figure 10a–e present the temporal evolution of reliability indices (RI

0, RI

1, RI

2, RI

combined) across five GNSS monitoring points. Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 exhibit pronounced upward trends, with individual indices (RI

0, RI

1, RI

2) increasing from approximately 10–15 to 35–62.5, while RI

combined values remain consistently lower (5–25), suggesting moderating factors in the combined assessment methodology. Point 4 exhibits anomalous declining trends (8–10 to 2–6), which contrast sharply with those at other locations and may potentially indicate localized stabilization or distinct geomechanical conditions. The strong correlation between RI

0, RI

1, and RI

2 across most stations suggests methodological consistency in capturing underlying deformation phenomena. The spatial coherence of elevated indices at four stations suggests extensive slope destabilization rather than localized instability. The acceleration from mid-December, with terminal values reaching 40–62.5 at multiple stations by January 2025, suggests a potential approach to critical thresholds warranting heightened monitoring and mitigation consideration. The divergent behavior at point 4 requires further investigation to distinguish genuine stabilization from instrument malfunction. Integration with meteorological data, geological mapping, and supplementary monitoring techniques would strengthen hazard assessment and interpretation of observed spatial heterogeneity in deformation patterns.

Comparing the class matrix (

Table 2) with reliability indices analysis reveals distinct measurement quality patterns with critical threshold exceedances at Point 1. While RI

combined at Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 progressively increases from 5–15 to 40–60, maintaining Class A status (RI < 60, Negligible Risk), RI

1 and RI

2 at Point 1 reach approximately 62.5, exceeding the Class A threshold and entering Class B (60 ≤ RI < 80, Low Risk—Trend Surveillance Required). This indicates movement within safe limits, but requires close trend monitoring and a causal investigation of rising trends. Points 2, 3, and 5 maintain all indices within Class A, with RI

combined reaching 42, 38, and 43, respectively. Point 4 exhibits oscillatory behavior with all indices below 14 units, indicating stable reference conditions. The exceedance of RI

1 and RI

2 beyond 60 units at Point 1 indicates degraded carrier phase residuals and temporal consistency, likely due to increased measurement noise during rapid displacement, atmospheric disturbances, or multipath interference. Elevated carrier phase residuals suggest difficulty maintaining phase lock during acceleration events, while compromised temporal consistency reflects increased short-term variability during episodic deformation.

The divergence of RI, which remains in Class A, while component indices enter Class B, indicates acceptable composite reliability despite specific measurement quality degradation. The threshold exceedance at Point 1, which exhibits the highest cumulative displacement (60 mm) and peak velocities (30–34.5 mm/day), demonstrates a correlation between active deformation and measurement challenges. These warrants enhanced trend surveillance, investigation of measurement anomalies, and potential refinement of data processing strategies to maintain optimal positioning precision during critical deformation episodes.

3.8.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Input Parameters on Combined Reliability Index Variance

The sensitivity analysis reveals the variance explained in RI

combined through correlation coefficients. Reliability indices RI

0, RI

1, and RI

2 dominate, with r values ranging from 0.995 to 0.999 (99.0–99.8% variance), indicating that GNSS quality metrics are primary determinants (

Figure 11). Total displacement shows r = 0.952–0.986 (90.6–97.2% variance), while cumulative effect demonstrates r = 0.908–0.986 (82.4–97.2% variance), with the highest values at Points 1, 2, and 5 and the lowest at Point 3. Standard deviation exhibits variable influence, being minimal at Points 1–2 (0.02–1.3% variance), moderate at Points 3 and 5 (7.9–12.6% variance), and negative at Point 4 (r = −0.122). Velocity shows negligible influence with r = 0.004–0.038 (<0.2% variance), except Point 3 (r = −0.114).

The mechanism reflects hierarchical reliability assessment where reliability indices directly quantify GNSS positioning quality through geometric dilution of precision, carrier phase residuals, and temporal consistency. Their dominant contribution (99.0–99.8%) indicates that RIcombined is primarily controlled by intrinsic positioning quality rather than deformation characteristics. Total displacement and cumulative effect exhibit a strong secondary influence (82.4–97.2%), as actively deforming points require higher positioning precision for displacement detection, thereby creating a correlation between deformation magnitude and reliability requirements. The variable influence of standard deviation reflects site-specific measurement conditions, with minimal impact at Points 1–2, indicating that short-term variability has a negligible effect on reliability when fundamental positioning quality is high. Velocity’s negligible influence demonstrates that instantaneous rate changes have a minimal impact on reliability compared to accumulated displacement metrics, indicating that RI primarily functions as a measurement quality indicator rather than a deformation severity metric.

3.8.2. Multicollinearity Assessment and Statistical Independence of Reliability Indices

The multicollinearity assessment reveals significant interdependencies among reliability indices (

Table 4). Chi-square testing reveals statistically substantial correlations with

p < 0.001 across all pairs. The RI

1 versus RI

2 pair exhibits the highest values (χ

2 = 168.9–185.2 at active points, χ

2 = 35.4 at Point 4), RI

0 versus RI

1 shows χ

2 = 118.7–142.5 at active points versus χ

2 = 48.2 at Point 4, while RI

0 versus RI

2 demonstrates the lowest correlations (χ

2 = 82.5–98.6 at active points, χ

2 = 62.8 at Point 4).

VIF analysis quantifies severity: RI0 maintains acceptable values (VIF = 1.95–2.14 at active points, VIF = 1.12 at Point 4), RI1 exhibits high multicollinearity (VIF = 7.89–8.42 at active points, VIF = 1.42 at Point 4), RI2 shows moderate multicollinearity (VIF = 4.58–5.12 at active points, VIF = 1.38 at Point 4), and RIcombined demonstrates very high multicollinearity by design (VIF = 11.63–12.85 at active points, VIF = 2.18 at Point 4).

The mechanism reflects shared dependencies on GNSS error sources. RI1 quantifies carrier phase residuals influenced by atmospheric delays, multipath, and orbital errors, while RI2 assesses temporal consistency affected by similar time-varying sources. Their high correlation indicates carrier phase quality directly impacts temporal stability, as phase breaks create temporal discontinuities. RI0 represents geometric dilution controlled by satellite constellation geometry, exhibiting a lower correlation because configuration changes independently of signal quality degradation. Point 4’s substantially lower chi-square and VIF values indicate stable measurement conditions, whereas active points exhibit amplified interdependencies, as rapid displacement simultaneously degrades carrier phase tracking, temporal consistency, and geometric solutions. RIcombined’s very high VIF is expected, as this composite index mathematically integrates component indices, inherently incorporating their collinearities.

The CTEDP framework integrates deformation severity and measurement confidence into a single actionable metric, where high sensitivity of RIcombined to GNSS quality indices (RI0, RI1, RI2) is intentional rather than flawed, functioning as a “Measurement Confidence-Weighted Risk Index” that downgrades risk estimates when data quality degrades during rapid motion, atmospheric disturbances, or multipath effects, recognizing that large displacement with low precision is less actionable than smaller displacement with high confidence. While RI1 and RI2 are statistically colinear with RI0 through shared underlying error sources (carrier-phase residuals, temporal consistency), each captures different monitoring reliability aspects: RI0 reflects geometric precision, RI1 incorporates dynamic tracking performance, and RI2 adds variability assessment, with their collinearity in active zones representing physically meaningful correlation where measurement quality degrades systematically as deformation accelerates in destabilizing slopes.

3.9. Analysis of CTEDP Model Results Across Monitoring Points in GNSS-Based Rock Slope Stability Assessment

The Comprehensive Time-Dependent Evaluation of Displacement Probability Model outputs (

Figure 12) reveal displacement probabilities ranging from 0.32 to 0.61. Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 exhibit convergent behavior, increasing from initial values of 0.33–0.43 to a synchronized range of 0.56–0.61 by early January, representing approximately a 40% probability increase. Point 4 exhibits a contrasting pattern, characterized by high initial volatility (0.45–0.61) in November, followed by a systematic decrease to 0.32, indicating stable reference conditions.

The temporal pattern reveals three phases: an initial volatile period in November, characterized by high-frequency oscillations and probability ranges of 0.10–0.15 units; a transitional phase in December, showing convergence with decreasing inter-point variability; and a mature phase from late December, with synchronized high probabilities (0.56–0.61) and reduced oscillations. The CTEDP model integrates displacement magnitude, velocity trends, acceleration patterns, temporal persistence, and measurement reliability through Bayesian updating, where accumulated displacement evidence progressively revises probability estimates. Initial high variability reflects limited data and epistemic uncertainty, whereas lengthening the time series reduces uncertainty, enabling a more robust assessment.

The convergence of Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 to a narrow range (0.56–0.61, variation <0.05) indicates mechanically coupled deformation as a coherent sliding mass responding to common driving forces. Uniformly elevated probabilities approaching 0.60 indicate moderate-to-high likelihood of continued displacement, consistent with Class 3–4 velocity behavior and sustained positive cumulative effect gradients. Point 4’s declining probability, from 0.45 to 0.61 and then to 0.32, reflects Bayesian revision as accumulated evidence demonstrates stability, progressively down-weighting the likelihood of displacement based on a minimal cumulative effect. Sustained high probabilities through early January without a plateau indicate ongoing instability, requiring continued monitoring and potential intervention to mitigate the risk of progressive failure.

3.10. Positioning This Study Within the Contemporary Landslide Early Warning Systems Literature

A dominant trend in contemporary landslide research is the development of data-driven early warning models [

33,

34]. Some models often employ ML algorithms to analyze vast datasets of rainfall, topography, and historical landslide inventories to predict susceptibility over large areas. For instance, a comparative study by Liu, Ma [

35] on RF, CNN, and MLP models for rainfall-induced landslides in Fujian Province achieved high accuracy (0.930–0.957) and AUC values (up to 0.955), demonstrating the power of machine learning for regional hazard zonation. Similarly, Mei, Ma [

19] have leveraged InSAR data with topological data analysis (persistent homology) to decipher spatiotemporal deformation patterns, achieving warning lead times exceeding 100 days for specific landslides by identifying system-wide precursory signals. Our study addresses a different but equally critical niche: high-frequency, real-time monitoring and forecasting for a particular engineered high-risk slope. While regional models excel at answering “where” landslides might occur, and topological methods identify “when” based on deformation fields, our GNSS-based CTEDP framework answers “how unstable is it right now, and what is the immediate trajectory?” for a known problem area. This is through direct kinematic precursors such as episodic accelerations at Point 1 (peaking at 34.5 mm/day and 1.15 mm/day

2) correlated with precipitation, providing early warning based on real-time slope mass response rather than statistical correlation or spatial pattern evolution, with more direct and physically interpretable links to mechanical state through displacement-derived indices than emerging multi-modal integration approaches.

Recent research demonstrates a clear shift towards operational, physics-based FoS forecasting. For example, an IoT-based digital twin system integrates hydrological modeling with machine learning (polynomial regression and Random Forest) to provide rolling three-day forecasts of FoS for specific slopes [

36]. This study represents the state of the art in transitioning classical geotechnical analysis into real-time decision-support tools. The CTEDP model offers an alternative probabilistic stability assessment pathway by using directly measured kinematic responses (displacement, velocity, acceleration) as primary inputs rather than forecasted hydrological parameters, with multi-tier Reliability Indices (RI

0, RI

1, RI

2) translating observed deformation into quantitative risk measures that sensitivity analysis confirmed were dominantly explained (99.0–99.8%) by foundational GNSS quality indices, making this data-driven, response-based approach particularly valuable in complex geological settings like Pulang, where accurately parameterizing full hydro-mechanical models for FoS calculation is exceptionally challenging.

Conventional slope stability rating, such as those using rock mass rating (RMR) or geological strength index (GSI) [

37,

38,

39], provide static assessments of rock mass quality but lack temporal resolution. For instance, studies employing RMR/GSI typically classify slopes into stability categories (e.g., “fair,” “poor”) without quantifying time-dependent deformation. Deterministic methods, such as FoS calculations [

40,

41], assume simplified failure mechanisms and material homogeneity. For example, numerical modeling studies by Li, Xu [

42] often report critical displacement thresholds (e.g., 50 mm) but neglect variability and cumulative effects. While velocity-based early-warning systems are widely used [

43], they often fail to detect pre-acceleration signals. Traditional seismic or radar interferometry methods capture surface deformation but lack jerk’s sensitivity to force redistribution, limiting their ability to identify incipient brittle failure [

44]. In contrast, the CTEDP model dynamically tracks displacement probabilities escalating from 0.35–0.43 to 0.57–0.60, signaling a 35–50% increase in landslide likelihood with temporal granularity, enabling proactive risk management by capturing accelerating failure precursors like jerk (1.5 mm/day

3 at Point 5) and incorporating statistical variability (standard deviation, skewness) with weighted cumulative effects (exponential decay factor) to differentiate between transient fluctuations (σ = 6.8 mm at Point 1) and persistent destabilization, reducing false alarms common in deterministic frameworks that static indices cannot achieve.

3.11. Autonomous Data Assimilation with Learning-Based Predictive Updates

The short-term monitoring establishes baseline signatures that inform adaptive strategies through recursive Bayesian updating, where evolving statistical parameters (σN(t), skewness, and kurtosis) provide confidence bounds that quantify prediction uncertainty. The framework implements adaptive monitoring frequency, where benign regimes trigger extended intervals, while anomalous patterns (accelerating rates, elevated σN(t), and positive skewness) automatically initiate high-frequency acquisition. The exponential weighting parameter λ balances responsiveness against transient noise, with periodic recalibration improving parametric estimates and narrowing confidence intervals. CTEDP coefficients a1, a2, and a3 undergo progressive refinement through maximum likelihood estimation, transforming initial judgment-based weights into empirically validated parameters. This enables a transition from conservative protocols toward optimized strategies while maintaining reliability through targeted intensification during critical transitions.

Point 1’s RI1 and RI2 transition into Class B provides quantifiable triggers for escalating monitoring and investigating causative factors, thereby moving slope management from a reactive, threshold-based alert system to a proactive, risk-informed regime. The CTEDP framework complements rather than replaces regional models or physics-based FoS forecasts within multi-layered early warning systems. Future synthesis could integrate regional ML models that identify susceptibility areas, InSAR and topological analysis for long-lead monitoring, and site-specific GNSS/CTEDP systems for real-time decision-making. This integration would also involve calibrating hydrological parameters using kinematic data in physics-based FoS models, creating feedback loops that improve both approaches.

3.12. Limitations and Future Work

The CTEDP framework advances rock slope stability assessment through spatiotemporal analysis of displacement patterns across five GNSS monitoring points, integrating displacement, velocity, variability, and cumulative effects into hierarchical reliability indices that enable probabilistic failure modeling. This calibration is achieved using quantile-based thresholds, establishing critical benchmarks validated against geotechnical standards. Limitations include measurement uncertainties reaching 6.8 mm, potentially inadequate exponential decay weighting assumptions for nonlinear geomechanical responses, temporal constraints resulting from limited monitoring periods, spatial heterogeneity as evidenced by Point 4’s anomalous stability, and velocity thresholds that require field validation against material strength parameters. The monitoring period, while capturing critical acceleration trends, is relatively short, and while hydrological triggers are inferred, direct integration of in situ pore-water pressure measurements would solidify causal links between precipitation and acceleration events. Multicollinearity between higher-order reliability indices (RI1, RI2) suggests that they share information about signal quality, warranting the exploration of orthogonal transformation techniques to obtain truly independent indices.

Future refinements should incorporate meteorological and geotechnical datasets, optimize model coefficients through machine learning, extend monitoring networks to capture seasonal variability, standardize jerk signatures for early warning criteria relative to material-specific failure thresholds, implement real-time CTEDP outputs with IoT-enabled GNSSs, and validate the framework across diverse geological settings. A significant challenge is developing methodologies for upscaling this site-specific framework across multiple slopes within mining complexes or infrastructure networks, potentially by creating libraries of kinematic signatures associated with different failure modes. This approach would enhance the robustness of the framework as a proactive tool for landslide risk management through interdisciplinary collaboration and technological innovation.