1. Introduction

In Latin America, public transportation faces a series of challenges and problems inherent to the social, economic, and cultural context, affecting efficiency, accessibility, and, above all, service quality. In most cases, public administrations seek to develop and implement strategies that optimize user well-being and safety in this modal system.

Although various public administrations have developed strategies and models to address the various problems of traffic congestion, poor urban infrastructure, network disintegration, and poor service quality, efficiency and operational problems persist on the main road corridors.

According to Gonzáles et al. [

1], traffic congestion in Latin American cities often leads to severe traffic situations, causing significant delays in public transportation systems and reducing user well-being and quality of life. In most cases, cities lack adequate infrastructure for public transportation, which hinders efficient mobility for citizens. The lack of dedicated bus lanes, bicycle lanes, and well-equipped transit stations is a common problem [

2].

Adding to this problem, public transportation systems are often not integrated, making it difficult for passengers to transfer between different modes of transportation, such as buses, trains, subways, etc., efficiently and economically, reducing the well-being of daily commutes [

3,

4].

The Latin American scenario is not encouraging in terms of public policies that define guidelines and strategies that allow for the development of urban well-being assessments of the various urban elements that directly influence the proper mobility of public transportation lines.

In this context [

5], infer that most public transportation services in Latin America suffer from maintenance problems, lack of cleanliness, and the use of old and uncomfortable vehicles, leading to a poor user experience that significantly reduces the well-being of users when using this mode of transportation.

Minor attributes, such as public transportation fares, are often high relative to the average income of the population, making access to these services difficult for those with fewer resources [

6]. Ref. [

7] emphasize in their study that the lack of adequate government subsidies hinders the improvement and expansion of these services.

Safety in public transportation is a major concern in many Latin American cities due to problems such as robbery, assault, and harassment, which discourage passengers from using these services. From a Latin American and Caribbean perspective, buses are the most widely used urban transportation system due to the large volume of mobility. However, in most cases, public transport mobility efficiency is ineffective in the face of high vehicle density, reduced traffic flow in urban spaces, and, above all, the various traffic interferences caused by transport units [

8].

Regarding Brazil, the context of this study, out of the 5570 municipalities, 49% (2867 municipalities) do not have organized public bus transportation services. Among the remaining municipalities, 18% (976 municipalities) are served exclusively by inter-municipal public transport, while 33% (1727 municipalities) provide municipal public transport services. Furthermore, only 20.8% of municipalities have an approved Municipal Transportation Plan, which is mandatory for municipalities with populations exceeding 20,000 inhabitants [

9].

In this urban context, public transportation plays a fundamental role in promoting social inclusion, and the authorities are responsible for ensuring the mobility of all citizens, structuring the public transportation network to compare different project alternatives within a reasonable context, thus achieving an efficient network for the city. Each project is generated in response to a need or problem. Thus, road projects arise from the identification of the accessibility issues to be addressed.

In this context, the public administration maintains its aspirations to offer road corridors associated with public transportation with high quality standards that contribute to the well-being of users of these modes of transport. There is a need to integrate the different aspects and attributes that intervene in the proper functioning of public transportation.

Public transport indicators are key metrics used to evaluate and measure the efficiency, effectiveness, and quality of public transport systems. These indicators provide valuable information on the performance of public transport services and help decision-makers identify areas for improvement.

From a public transport system efficiency perspective, various indicators can be reviewed that suggest substantial improvements in user perception during transport use, such as punctuality rate, service frequency, unit capacity, network coverage, and user satisfaction rates, among others.

While efficiency in public transport systems is commonly associated with the optimization of resources, operational performance, and cost-effectiveness, several indicators traditionally used to assess efficiency also reflect users’ perceived service quality. Indicators such as punctuality, service frequency, network coverage, and capacity utilization are operational in nature, yet they directly influence passengers’ experience and satisfaction during system use.

These indicators are essential for evaluating and improving the quality and efficiency of public transport [

10]. They allow those responsible for planning and managing transport systems to identify problem areas and develop strategies to optimize service, improve the user experience, and create a more sustainable and accessible system for all.

In the city of Foz do Iguaçu, the quality of urban road maintenance represents a critical challenge for the efficiency and sustainability of public transport. This technical problem is exacerbated in key corridors served by the main urban bus lines, highlighting inequalities in infrastructure, accessibility, and mobility. Despite municipal efforts to improve the system’s operating conditions, deteriorating roadways, limited infrastructure for people with reduced mobility, and poor signage compromise service quality and user well-being.

Furthermore, the institutional framework reveals a fragmented reality: only a minority of Brazilian municipalities have Municipal Transportation Plans, and Foz do Iguaçu is no exception. Public administrations have focused their investments on areas with high tourist demand, neglecting peripheral neighborhoods where a large part of the working population is concentrated. This lack of comprehensive planning and sustained maintenance strategies exacerbates territorial disparities.

The juxtaposition of these types of problems arises from the configuration of criteria that are poorly associated with the proper organization of vehicular and pedestrian traffic. The quality of the public transportation system and its interaction depend essentially on sound planning, regulation by government authorities, and, above all, on the incorporation of urban indicators that directly influence user mobility. The multicriteria methodology is widely used in various fields, such as business management, urban planning, engineering, natural resource management, policy decision-making, and operational research, among others.

Within this context, this work sought to construct an evaluation of the urban public transportation network through a multicriteria model, which provides information on the various factors in the conflict zone. The development of a methodology, initially defined as a diagnostic tool for urban spaces, provides a strong component of methodological innovation, responding to current social problems.

In this scenario, the systematic evaluation of public transport corridors emerges as a critical need for supporting informed decision-making in urban mobility management. The complexity of Latin American cities—marked by heterogeneous infrastructure conditions, institutional fragmentation, and limited planning instruments—demands analytical approaches capable of integrating technical, operational, and user-oriented perspectives. Traditional assessments often address isolated variables, which restricts their ability to capture the interdependencies between road infrastructure conditions, service performance, accessibility, and user well-being. Consequently, there is a clear gap in methodologies that allow public administrations to comprehensively diagnose transport corridors and prioritize interventions based on transparent and comparable criteria.

To address this challenge, this study proposes a multicriteria-based evaluation framework for urban public transport infrastructure, applied to key bus corridors in the city of Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil. By integrating a set of indicators related to infrastructure condition, operational efficiency, and user perception, the proposed approach enables a structured assessment of corridor performance and highlights critical areas requiring intervention. The methodological contribution of this work lies in its capacity to translate complex urban dynamics into a synthetic and decision-oriented diagnostic tool, supporting sustainable transport planning and contributing to the improvement of service quality and urban well-being in medium-sized Latin American cities.

2. State of the Art: Conception of the MIVES Model

The integrated multi-criteria structural evaluation model, known as MIVES (original language Modelo integrado de valor para edificaciones sostenibles), is a methodology designed to assess alternatives associated with a given problem across its entire life cycle. This tool is grounded in multi-attribute utility theory and employs value analysis for each selected indicator, ultimately generating a sustainability index.

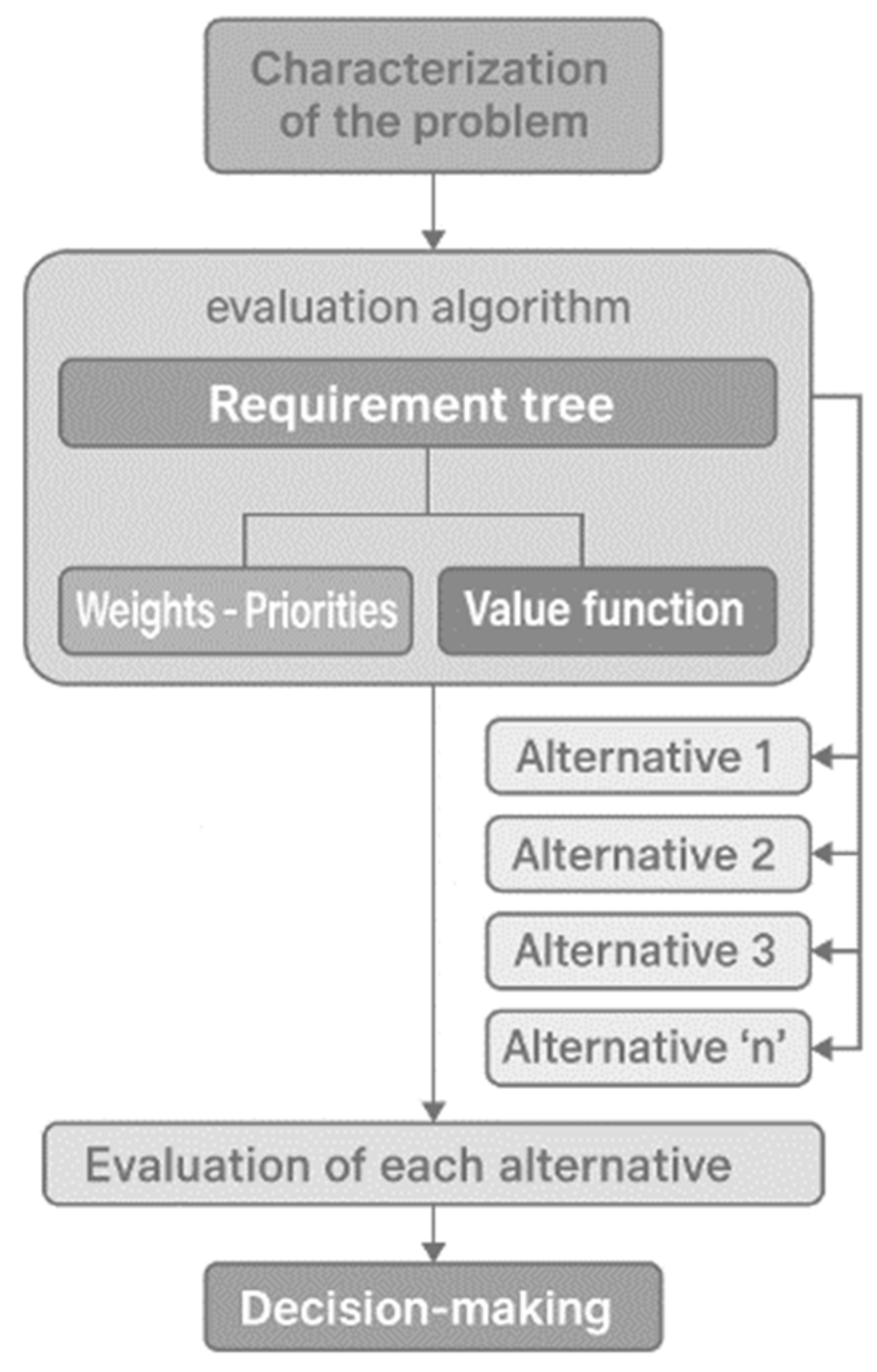

Figure 1 illustrates the general algorithm of the MIVES multi-criteria model applied in this study. The evaluation procedure comprises six fundamental stages. The initial stage, referred to as problem characterization, establishes the system boundaries and defines the boundary conditions of the issue under analysis. In other words, this phase identifies the stakeholders involved in the decision-making process. It also structures the three principal axes of the model: requirements (objectives or intended outcomes), components (elements subject to evaluation), and the life cycle of the problem.

The second stage is regarded as the core of methodology. At this point, the “requirements tree” is constructed with the purpose of organizing, grouping, and clearly identifying the variables selected during the initial phase of the study.

The third stage may be carried out concurrently with previous steps. At this point, the analytical hierarchy process (AHP) is implemented to determine the weights or relative importance of each indicator, as well as to define the utility or value functions (VF) that enable the transformation of the indicators into one-dimensional units.

The selection of indicators under this methodology requires the incorporation of variables that meaningfully contribute to the decision-making process and that effectively differentiate among the alternatives evaluated. Conversely, the inclusion of indicators with low relevance, limited importance, or redundant information increases the complexity of the model during the evaluation phase and, more critically, dilutes the perceived significance of the assigned weights when comparing attributes.

2.1. Weighting of the Variables

The analytical foundation of multicriteria evaluation models relies primarily on the examination and comparison of attributes and indicators. In practice, the interpretation and contrast of the variables under study employ methodological frameworks or mathematical structures that assist decision-makers in assigning relative importance or priority levels to each variable.

In this research, the weighting of attributes including requirements, criteria, and indicators was established using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). According to Saaty [

11], the evaluation and calibration of such models draw on mathematical, analytical, and cognitive principles that allow for an empirical validation of pairwise comparisons among variables.

The underlying premise of AHP suggests that individuals can readily compare two attributes at a time; however, when a third element is introduced, cognitive limitations may reduce the accuracy of such judgments (1956).

Table 1 presents the numerical comparison scale employed by the AHP methodology, which includes a verbal rating scheme and its corresponding quantitative interpretation. It is important to emphasize that comparisons must be made only among indicators belonging to the same hierarchical group and of comparable nature.

2.2. MIVES Advances

The MIVES framework enables the evaluation and comparison of multiple project alternatives through a sustainability-oriented lens, producing a value or sustainability index grounded in the principles of multi-attribute decision theory.

Table 2 summarizes the different applications documented in the literature that employ the MIVES multi-criteria approach. In each case, the methodology integrates a set of attributes as a fundamental structural component, while incorporating specific methodological refinements adapted to the characteristics and requirements of each study.

It is worth emphasizing that the MIVES methodology enables the structuring and assessment of alternatives that incorporate indicators of diverse nature and heterogeneous measurement units. Its high degree of adaptability makes it possible to compare, prioritize, and evaluate a wide range of projects, regardless of whether their indicators are qualitative, quantitative, or a combination of both.

3. Materials and Methodological Approach

This section describes in detail the materials and methodological framework adopted in the study, emphasizing an applied analysis of urban mobility corridors in the municipality of Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil. The research is structured around the characterization of the study area, considering its territorial configuration, functional land-use patterns, and the operational characteristics of the public transport system. Special attention is given to the identification of strategic corridors that concentrate high passenger demand and play a central role in daily urban mobility. These elements provide the contextual basis for defining the analytical boundaries of the study and ensure that the selected corridors are representative of the city’s mobility dynamics.

Furthermore, the methodological approach establishes a set of criteria and indicators to support the systematic evaluation of the selected transport corridors. These criteria incorporate aspects related to infrastructure condition, accessibility, operational performance, and user-oriented attributes, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of corridor functionality. The framework is aligned with Transit-Oriented Development principles, promoting the integration of public transport performance with surrounding land-use characteristics and social sustainability objectives. By linking mobility efficiency to urban form and accessibility, the proposed methodology seeks to support evidence-based planning and decision-making processes aimed at improving the quality, resilience, and inclusiveness of urban transport systems.

3.1. Applied Case Study

The research was carried out in the municipality of Foz do Iguaçu, located in the western region of the state of Paraná, with an estimated population of 257,971 inhabitants [

20]. The city is ranked as the third most significant tourist destination in Brazil.

Foz do Iguaçu is widely recognized for its consolidated tourism infrastructure, broad hotel network, variety of leisure facilities, and remarkable cultural diversity, positioning it as one of the country’s most multicultural urban centers. The city is geographically shaped by the Paraná and Iguaçu rivers, natural boundaries that have contributed to its spatial growth, strongly influenced by private mobility, commerce, and service-sector activities. Demographically, Foz do Iguaçu can be classified as a medium-sized city whose economic dynamics are defined mainly by cross-border trade and tourism linked to landmarks such as Iguaçu National Park, the Iguaçu Falls, and the Itaipu Hydroelectric Plant, which reinforce its prominence among cities in the tri-border region [

23].

The urban layout follows a concentric-radial configuration, in which employment opportunities and access to goods and services are predominantly concentrated in the central area or along the main road axes that connect the city center to peripheral neighborhoods. This spatial pattern generates considerable challenges in terms of mobility and accessibility, particularly for residents living farther from the center, who often face longer travel times and limited access to essential services and opportunities located in central districts.

Regarding its public transport system, the city operates through a central urban transport terminal (TTU) positioned in the commercial core. This terminal serves as the convergence point for the main municipal bus lines and the international routes connecting Foz do Iguaçu with Ciudad del Este (Paraguay) and Puerto Iguazú (Argentina).

In recent years, the public transport network has progressively adapted to the radial configuration of the city, enabling greater connectivity across neighborhoods to serve residential and commercial demand. Despite improvements in service continuity and operational stability over the past three years, technical shortcomings persist in transport planning particularly in origin–destination structuring—resulting in route overlap and reduced operational efficiency.

The municipal public transport network comprises 34 urban bus routes, most of which depart from or pass through the TTU. Only a few lines operate independently of the terminal, such as lines 100 (Remanso Grande), 205 (Santa Rita), and 320 (Inter-neighborhood).

For this research, 20 urban routes referred to as transport corridors were selected. These corridors correspond to the main axes along which the bus lines evaluated in the study circulate. The selection process considered routes with significant tourism and operational relevance, as well as criteria such as vehicular traffic volume, pedestrian flow, and concentration of commercial and gastronomic activities.

Regarding the Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) approach, the Master Plan of the city of Foz do Iguaçu was reviewed with the aim of establishing a conceptual framework that integrates urban mobility with land-use planning, promoting compact, mixed-use, and well-connected environments around transport nodes. Under this approach, the evaluation of mobility corridors cannot be understood in isolation, but rather as part of a broader territorial system in which urban density, land-use mix, and accessibility to stations play a decisive role in the performance of the transport system. In the present study, particular emphasis was placed on conducting data collection in areas with homogeneous spatial and land-use characteristics, specifically commercial areas, to ensure comparability of the results. Previous studies indicate that higher density and greater functional diversity within station catchment areas foster more sustainable mobility patterns, reducing automobile dependence and improving the efficiency of public transport systems [

24,

25].

During the fieldwork phase, a data collection protocol was implemented to measure key parameters associated with each indicator. Data were recorded for all selected corridors while adhering to national and international technical standards.

Table 3 presents the urban roads included in the study, listing the full names of the avenues, their corresponding identification codes, and the main bus line associated with each corridor.

Data collection was carried out through on-site visits conducted on different days of the week, including weekdays and weekends. Surveys were frequently performed during periods of higher vehicular and pedestrian traffic, under normal weather conditions (i.e., without rainfall or extreme heat). Throughout the entire data collection process, the same evaluators were involved under consistent survey conditions, with equivalent knowledge and training, to minimize potential biases during data acquisition.

It is important to highlight that the selection of road corridors considered those roads where public transport units with the highest number of users, route length (greater than 3 km), and economic impact on the city are used.

3.2. Conception of Indicators

The study evaluates three fundamental components present within the road corridors used by public transport routes: urban infrastructure, accessibility, and mobility. The definition and organization of these attributes require a detailed examination of the physical state of urban elements, verification of compliance with international accessibility standards, and an assessment of the quality of user movement throughout the urban environment.

Table 4 outlines the methodological framework developed for diagnosing and evaluating the various corridors served by public transport, as well as the factors that influence the performance of the modal systems operating within them. Broadly, the Urban Infrastructure requirement focuses on analyzing the physical condition and overall quality of urban components. It is divided into two specific indicators: roadway quality and asphalt surface condition. These indicators measure the structural state of the elements that support public transport operations and the pedestrian environment used by individuals to reach their destinations.

The Accessibility requirement encompasses a set of indicators related to the degree of adherence to universal accessibility standards, particularly those established in Brazil by NBR 9050:2020 [

26]. This regulation defines the conditions necessary to ensure mobility and accessibility for individuals with disabilities or reduced mobility, which in turn demands the provision of appropriate urban infrastructure and adapted circulation spaces. Its central objective is to enhance the quality of urban mobility for users who depend on such adaptations.

The Mobility requirement incorporates indicators that cut across various transportation modes pedestrian, light vehicle, cycling, and public transport. For instance, within the mobility quality indicator, attributes such as roadway density, interference between users, pedestrian signage, and shading at public transport waiting points are examined.

A key aim of the study is to diagnose and evaluate the conditions that shape user mobility both while traveling on public transportation and during transfers through pedestrian networks. These indicators are quantified using parameters associated with traffic congestion, pedestrian flow intensity, and user comfort, and are scored on a 0–100 scale.

The criterion labeled physical condition of the element focuses on assessing the quality of the public transport vehicle’s trajectory, alongside the level of maintenance or deterioration of the pedestrian pathways surrounding the stops.

For the regulatory compliance criterion, indicators and parameters reflecting mobility conditions from the universal accessibility perspective were adopted [

27]. This criterion specifically examines bus stops and their associated infrastructure, assessing whether adaptations for individuals with disabilities and circulation requirements are adequately provided. Such analysis reveals the extent to which public authorities fulfill international guidelines related to socially inclusive urban environments.

The criteria associated with pedestrian and light vehicle modes evaluate the level of service provided in the spaces where pedestrians continue their journey after using public transportation. In the case of cycling, the ride quality and safety indicators were assessed using attributes such as the presence of dedicated bike lanes, cyclist-specific traffic signals, adequate lighting conditions, and drivers’ respect toward cyclists.

Finally, the public transport criterion analyzes the infrastructure and signage quality indicator, considering elements such as the availability of exclusive bus lanes, posted speed limits, bus stop conditions, service frequency, and the adequacy of transport signage.

3.3. Splitting of Indicators

This section details the parameters included and reviewed in each of the indicators defined for the study. Weights, degrees of compliance, and characteristics associated with local and international regulations have been defined for the attributes reviewed.

Table 5 shows the different parameters defined for the “roadway quality” indicator, such as deterioration, continuity, and lighting. This measurement scale represents, in a sense, the level of service (from A to E) provided for pedestrian mobility when traveling on the roadway. For each attribute reviewed, degrees of compliance have been defined based on the condition of preservation or deterioration of the element.

This methodology outlines the field data collected to assess the condition of the roadway, assigning differentiated service levels that range from excellent surface quality (Service Level A) to very poor conditions (Service Level E).

Table 6 details the specific parameters associated with each service level used to evaluate the pavement’s condition. The indicator classifies five degrees of deterioration, spanning from an optimal, well-preserved surface to advanced asphalt loss. For each level, the defining characteristics are described to ensure that inspections based on visual examination and operational performance are conducted with the highest degree of precision.

For the development of the accessibility requirement, two quantitative indicators were analyzed to determine the extent to which urban spaces comply with international accessibility standards. Among these indicators is the assessment of “infrastructure adaptations for individuals with disabilities and circulation areas,” which examines compliance with signage standards, spatial layout requirements, and the provision of appropriate access and movement areas.

Table 7 presents the parameters applied to evaluate the indicators associated with the accessibility requirement. It details both the degree of compliance in accordance with Brazilian standards [

26] and the weights assigned based on the relevance and physical presence of each urban component.

It should be emphasized that the Regulatory Compliance criterion evaluates the strategies implemented by public authorities to meet international standards and guidelines related to the quality of life of users with reduced mobility.

Table 8, for instance, outlines and encourages the adoption of measures aimed at enhancing urban elements such as signage and mobility-support infrastructure. Adhering to these parameters demonstrates a committed approach to social inclusion and contributes substantially to improving overall urban mobility conditions.

The Mobility indicator is structured around four criteria that incorporate both qualitative and quantitative dimensions: pedestrians (mobility quality and noise pollution), light vehicles (interference), cyclists (travel quality and safety), and public transport (infrastructure and signage quality). These indicators are evaluated numerically on a scale ranging from 0 to 100 points, while noise pollution levels are measured in decibels within the urban environment.

For the mobility quality indicator, four parameters are examined: roadway density, mobility interference, pedestrian signaling, and shading availability (see

Table 9). Each parameter is characterized by distinct compliance levels and is assigned to a specific weighting factor.

The roadway density parameter is defined through six service levels, each associated with an assigned weight. To determine the appropriate service level,

Table 10 is employed, which links pedestrian space availability, flow rate, and walking speed to derive the level of service based on pedestrian density.

The mobility interference parameter reflects the physical obstacles or interruptions encountered by pedestrians as they move along their routes. In practical terms, the roadway is evaluated based on elements that disrupt pedestrian flow and diminish travel quality over short distances.

Additionally, the parameters pedestrian traffic signals and shading were incorporated to assess factors that influence the overall quality of pedestrian movement from origin to destination. These parameters are analyzed through weighting schemes that consider the degree of interference, the presence of signaling devices, and the density of roadside trees.

The noise pollution indicator was quantified using portable measurement equipment (SKILL-TEC SKDEC-01 Digital Portable Sound Level Meter—Range 30 dB to 130 dB), enabling verification of compliance with the ABNT NBR 10151:2019 [

28] standard applicable to the municipality of Foz do Iguaçu, as summarized in

Table 11.

Table 12 presents the Interferences indicator associated with the light vehicle criterion, which assesses traffic and mobility quality based on three key parameters: the presence of speed-control devices (radars), the degree to which light vehicles disrupt pedestrian movement, and the proportion of light vehicles circulating on the roadway (calculated through traffic counts and vehicle-type decomposition).

In

Table 12, light-vehicle interruptions affecting pedestrians represent any type of interference on roadways or pedestrian crossings that limit or disrupt the pedestrian’s proper movement from one point to another. Accordingly, the percentage of light vehicles (greater than 50%) is intended to reflect delay phenomena associated with high traffic density, particularly in scenarios with a high concentration of heavy vehicles.

The ride quality and safety indicator encompasses parameters used to assess urban infrastructure conditions and the presence of electronic control devices along the roadway.

Table 13 details these parameters, indicating their maximum score on a 100-point scale and the corresponding weight assigned based on their level of compliance.

The urban transport criterion incorporates the infrastructure and signage quality indicator, which is assessed through five specific parameters. The purpose of this indicator is to determine the extent to which existing urban infrastructure contributes to improving mobility conditions along the roadway network.

Table 14 summarizes the parameters considered in this evaluation: the presence of dedicated bus lanes, the availability of speed-control devices, the condition of public transport waiting areas, service frequency quality, and the adequacy of transport signage.

With regard to the evaluation presented in

Table 14, each of the five parameters is reviewed and assigned a corresponding value. The sum of the five parameters assessed for each road segment constitutes the value used in the MIVES model as the response of this indicator associated with each road segment.

Each indicator, criterion, and requirement established in this study was designed with the overarching purpose of enhancing mobility conditions within the transportation systems under analysis. The weightings presented in the corresponding indicator and parameter tables were defined through a series of technical meetings involving transportation experts, specialists in urban indicators, and methodologists in project evaluation.

3.4. Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI)

To integrate the indicators selected in this research, the value-based assessment methodology MIVES (Integrated Value Model for Sustainable Assessments) was applied. This model enables the evaluation of alternatives through two core processes: the assignment of weights and the definition of value functions. In the context of this study, the alternatives correspond to the different urban road segments that accommodate public transport routes.

Within this framework, the Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI) establishes a classification system for roadway segments based on their service condition, level of preservation, and degree of deterioration of the components influencing the mobility of public transport vehicles. Consequently, the index obtained during the evaluation process reflects the quality of user experience and the safety conditions of the transport network.

During the problem characterization stage, the set of urban roads (alternatives) traversed by the public transport lines listed in

Table 1 is defined. In the requirements-tree stage, the elements to be assessed (e.g., travel lanes, bus stop conditions) are identified and structured across three hierarchical levels: requirements, criteria, and indicators.

To determine the weights associated with the criteria, the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) proposed by Saaty [

11] was employed. These weights, expressed as percentages, represent the relative importance of each aspect. It is noteworthy that the weighting process was carried out through a consensus-building approach involving experts in transportation, public administration, engineering, and public policy.

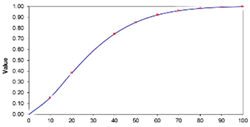

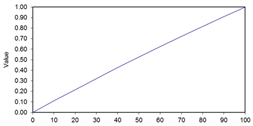

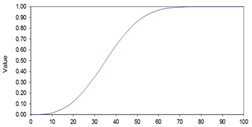

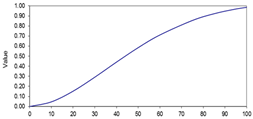

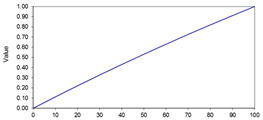

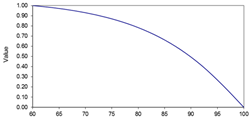

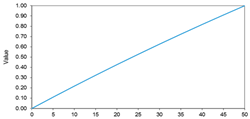

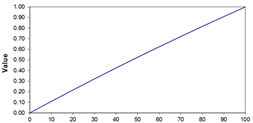

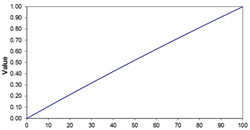

Regarding the construction of value functions,

Table 15 presents the specific functions assigned to each indicator included in the study. The table links the three hierarchical levels (requirements, criteria, and indicators) with the format (S-shaped, concave, or convex) and the trend (increasing or decreasing) of each value function. The configuration of these functions was established with the contribution of specialists in transportation, public management, engineering, and political decision-making.

Conversely, the purpose of the value function is to convert indicators originally expressed in physical units into a unified, dimensionless scale. This standardization facilitates the coherent integration of attributes with differing measurement types. The value function is determined through four adjustable parameters that, once calibrated, define various behavioral trends either increasing or decreasing as represented in Equation (1).

where,

A = value that generates the abscissa

Xmin, generally

A = 0,

Xmin = abscissa of the indicator that generates a value equal to

A,

X = abscissa of the evaluated indicator that generates a value equal to

Vind,

Pi = determines the slope of the curve at the coordinate inflection point (

Ci,

Ki), defines the shape of the curve.

Ci = for

S shaped curves, this factor establishes the value of the abscissa around the inflection point,

Ki = defines the value of the ordinate of the point

Ci. On the other hand, the parameter

B (Equation (2)) is the factor that guarantees to keep equation 1 in the interval 0 and 1 and is expressed by Equation (2).

It is important to note that each parameter indicated in the equations defines or configures the value function. The mathematical representation presented here assumes the construction of a utility function that allows specific values (e.g., meters, number of trees, interferences, etc.) to be converted into dimensionless values.

In accordance with the MIVES methodology and the structure illustrated in

Figure 2, the evaluation of urban infrastructure linked to public transport corridors is conducted hierarchically beginning with indicators, followed by criteria, and ultimately the overarching requirements.

To calculate the Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI) for each criterion, Equation (3) is applied. This expression represents the weighted sum of the indicators associated with a given criterion. Through this procedure, the analysis encompasses the physical condition of the infrastructure used by public transport vehicles, the degree of compliance with accessibility standards by public authorities, and the performance of the various mobility systems operating within the urban environment (pedestrian, light vehicle, and public transport).

About the attribute “

Wi,” defined as the weight of the indicator (criterion or requirement), it directly expresses the importance of this variable during the consensus process among experts and study participants. Although predefined values are presented in

Table 15 (in parentheses), these weights can be adjusted for each specific case or region where the model is applied. Ultimately, the

Wi parameter enables the final TICI values to be obtained in both equations through two main components: the weight of the attribute and its corresponding response (as defined by the value function).

The model further enables the assessment of the routes corresponding to each public transport line across its three principal dimensions: urban infrastructure, accessibility, and user mobility. Using Equation (4), the TICI value associated with each requirement is obtained by summing the products of the criteria that compose it and their respective predefined weights.

Finally, to determine the TICI value for each urban roadway segment linked to a transport line, Equation (5) is applied, which expresses the sum of the products between each global requirement and its corresponding weight.

The model developed in this research provides a diagnostic framework for assessing the conservation status or deterioration of the urban elements that support public transport routes, thereby enabling the identification of mobility quality levels experienced by users throughout their journeys. Moreover, the model quantifies these mobility conditions through the TICI (Transport Infrastructure Condition Index), evaluated across three hierarchical layers: requirements (macro-level), criteria (intermediate thematic aspects), and indicators (specific analytical components).

The purpose of the model is to offer public authorities clear guidance for detecting urban road segments that require maintenance or rehabilitation interventions. The analytical structure proposed in this study focuses on evaluating the factors that directly influence user mobility when interacting with the public transport system.

This approach allows for the examination of broad issues such as accessibility and adherence to international standards as well as more detailed elements, including the condition and influence of urban components, the interaction among different transport modes, and their combined impact on user experience.

4. Results

The study aimed to integrate all factors influencing the effective mobility of the city’s public transport corridors, considering aspects related to mobility performance, the condition of urban components, and compliance with accessibility standards. The model developed introduces an innovative analytical tool for diagnosing urban environments, particularly transport corridors with the purpose of classifying roadway segments and supporting decision-making processes concerning public investment.

The elements examined were incorporated into the Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI) through the parameters defined for each indicator. Accordingly, the results are presented at three levels: (i) a global assessment considering all roads and their respective transport lines, (ii) specific TICI values for each requirement axis, and (iii) detailed results for every indicator included in the analysis.

It is important to note that TICI values range from 0.00 to 1.00. Values approaching 1.00 represent roadway segments that provide adequate mobility conditions and promote user well-being and safety. Conversely, values close to 0.00 reflect deficiencies in the physical condition of infrastructure components, non-compliance with accessibility standards, and poor mobility conditions for public transport operations.

To support strategic decision-making regarding infrastructure investment, four levels of intervention priority were established. Roadways with TICI values between 80% and 100% are classified as low priority for intervention. Values between 79% and 60% indicate the need for corrective action. Scores between 59% and 40% denote segments requiring priority intervention by public authorities, while values below 40% signify roads in urgent need of corrective measures due to evident mobility constraints, deterioration of urban elements, and adverse impacts on user quality of life.

Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI) for Public Transport

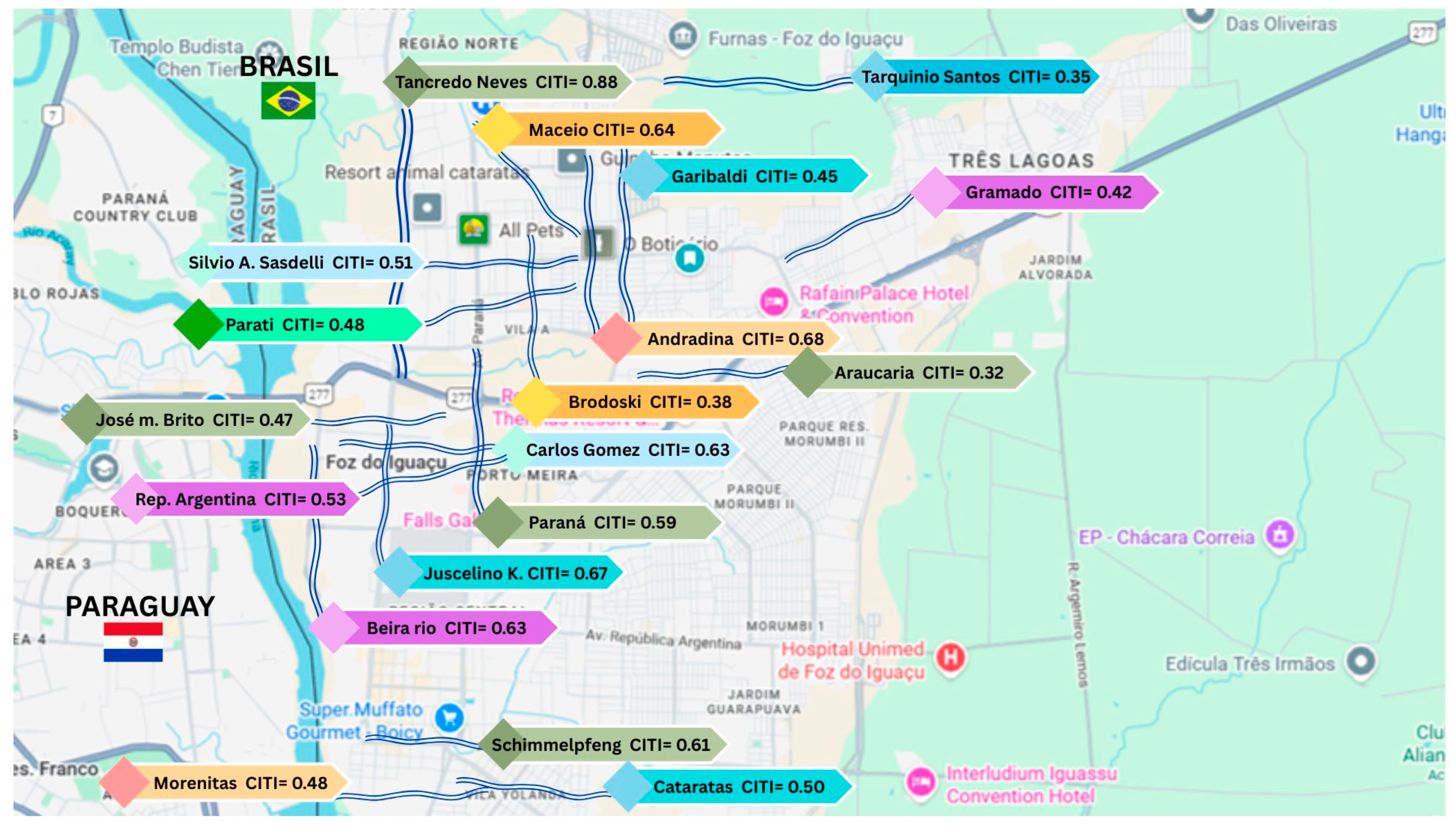

The results of the study were structured to allow the identification of the TICI value corresponding to each roadway segment served by the city’s public transport lines.

Table 16 and

Table 17 present the TICI outcomes obtained through the proposed model and validated during the field data collection phase for all analyzed urban corridors.

The two tables previously cited display the results generated by the applied model. The first column lists the criteria and indicators evaluated in the study, followed by the set of roadway segments (numbered 1 through 20) along with their corresponding overall TICI values.

It is essential to consider the specific public transport line operating on each roadway segment shown in the tables. The TICI-based classification of each route enables both a comprehensive and a detailed examination of the aspects evaluated during the study. While some urban corridors exhibit satisfactory performance, such as Roads 1, 13, and 14, with TICI values of 0.88, 0.63, and 0.67, respectively, others demonstrate critical deficiencies and require immediate maintenance interventions, including Roads 2, 6, and 7, with values of 0.35, 0.32, and 0.38.

The model also facilitates the identification of specific indicators with higher or lower levels of compliance in terms of infrastructure condition, adherence to international accessibility standards, and the mobility environment associated with each transport line. For instance, although the roadway quality indicator performs well across most corridors, parameters such as pedestrian interference and the presence of vehicle speed-control devices (radars) consistently register low performance levels along multiple segments.

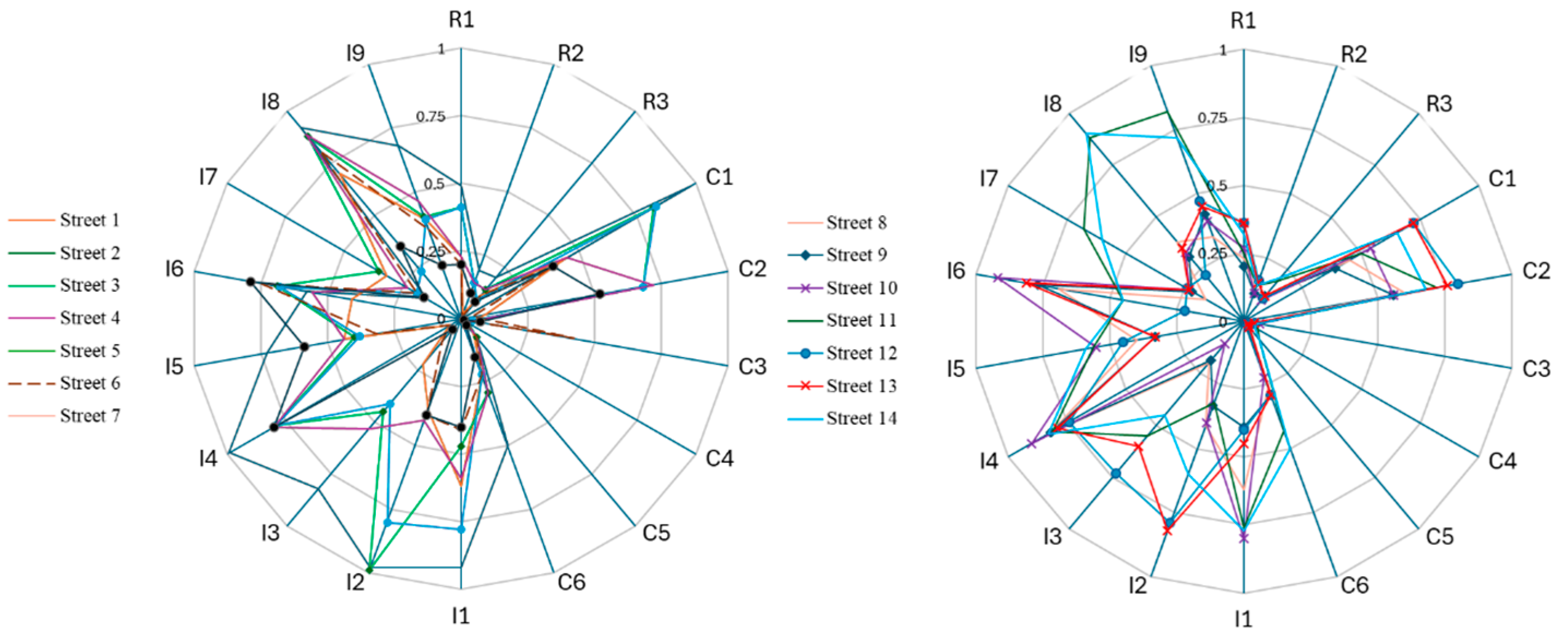

Overall, the results across the three analytical layers—requirements, criteria, and indicators—are synthesized graphically in

Figure 2. Each polygon corresponds to a roadway corridor used by one or more transport lines. Polygons approaching the outer boundary represent corridors with TICI scores nearing 1.0, indicating better mobility conditions and a well-preserved state of the urban components supporting public transport operations.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, there is a noticeable pattern in the municipal administration’s approach to addressing the various elements of the evaluated roadway segments. The similar shapes of the polygons reveal a consistent trend—whether favorable or unfavorable in the management, maintenance, and conservation of urban components.

Due to spatial constraints,

Figure 2 presents only 14 of the 20 corridors analyzed. It is important to highlight that indicators I2, I4, and I8 (asphalt surface quality, circulation areas, and transit quality for public transport users) generally achieve satisfactory TICI values, reflecting adequate conditions for user comfort and safety. In contrast, indicators such as I3 and I7 (urban adaptations to satisfy accessibility requirements for persons with disabilities and interference affecting pedestrian mobility) reveal shortcomings or insufficient compliance across most of the evaluated roadway segments.

Figure 3 presents the spatial distribution of the Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI) for the analyzed road corridors within the urban area of Foz do Iguaçu and its cross-border context. Each road segment is geographically represented and labeled with its corresponding TICI value, allowing for a clear visualization of the relative condition of the infrastructure across the study area. The corridors are associated with public transport lines, emphasizing their functional relevance within the urban mobility system. This spatial representation highlights the heterogeneity in infrastructure conditions, with TICI values ranging from low to high, reflecting varying levels of service and structural adequacy among the analyzed corridors.

In addition, the map enables the identification of spatial patterns and potential clusters of corridors with similar TICI performance, facilitating comparative analysis and prioritization of interventions. Road segments with higher TICI values indicate better infrastructure conditions and greater support for mobility and accessibility, whereas lower values suggest segments requiring corrective or urgent actions. By integrating geographic location, transport line alignment, and TICI performance in a single visual framework, the figure enhances the interpretability of the results and supports decision-making processes related to corridor management, urban mobility planning, and territorial sustainability.

5. Discussion

The TICI index results reveal substantial disparities in the condition of urban transport corridors in Foz do Iguaçu, exposing a fragmented and uneven mobility landscape. The wide range of values obtained between 0.32 and 0.88 demonstrates that while certain corridors adequately fulfill infrastructure, accessibility, and mobility requirements, many others exhibit severe deficiencies that demand immediate governmental intervention. This heterogeneity reflects not only differences in the physical quality of urban infrastructure but also the absence of integrated mobility planning that accounts for multimodal transport and the actual needs of daily users.

A key contribution of this research lies in the incorporation of technical, regulatory, and social dimensions through a multicriteria evaluation approach, specifically the MIVES methodology applied innovatively to the diagnosis of urban transport systems. Unlike conventional assessments limited to infrastructure conditions or service-level indicators, this study employs a holistic perspective that includes both qualitative and quantitative parameters, such as user well-being, universal accessibility, and features of the pedestrian environment. This combination not only enables a comprehensive evaluation but also supports objective prioritization of interventions across the road network.

Notably, indicators linked to accessibility, particularly those addressing adaptations for individuals with reduced mobility and the availability of adequate circulation areas, show the lowest levels of compliance. This pattern reveals a systemic shortfall in meeting urban inclusion standards and disproportionately affects vulnerable populations, thereby reinforcing social inequities in access to mobility. By identifying these gaps, the proposed model emerges as a strategic tool for designing inclusive public policies aimed at promoting territorial equity.

The analysis of the mobility component similarly highlights deficiencies in aspects such as pedestrian interference and the limited quality of cycling-related infrastructure. The scarcity of bike lanes, inadequate traffic signaling for cyclists, and insufficient signage compromise road safety and reduce the appeal of sustainable transport options. These findings underscore the need to redesign urban spaces through a truly multimodal lens, integrating diverse user profiles and promoting more resilient and accessible mobility systems.

From a governance standpoint, the application of TICI enables the creation of intervention hierarchies grounded in empirical evidence, supporting more efficient allocation of public resources. By categorizing corridors according to their urgency for maintenance or improvement, the model offers tangible inputs for planning investments and prioritizing actions based on technical and social impact. This capability is particularly relevant in Latin American cities, where fiscal limitations coexist with increasing demands for high-quality urban mobility.

In summary, both the methodological approach and the empirical results confirm the value of multicriteria analytical tools for assessing the sustainability and effectiveness of public transport infrastructure in complex urban environments. The adaptability of the model to cities with similar characteristics broadens its potential for producing robust diagnostics, guiding public policy, and advancing toward more integrated, equitable, and sustainable mobility systems across Latin America.

The model proposed in this study incorporates 10 indicators with multiple associated parameters, structured to allow replication in other urban contexts. Although the indicators were defined for the specific conditions of this case study, they can be adjusted, removed, or complemented to suit the distinctive needs of different cities. Furthermore, indicator weightings may be recalibrated in response to technical, regulatory, or institutional considerations relevant to each context of application.

Ultimately, the methodological framework introduced here combines diagnostic analysis and evaluative procedures for urban corridors that shape the performance of public transport. Its innovative character is reflected in the coherent and systematic integration of all the aspects assessed, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of urban mobility and more informed decision-making

6. Conclusions

This research, focused on assessing urban mobility linked to public transport, employs a methodological framework grounded in the MIVES model combined with hierarchical analysis (AHP). The integration of these tools enabled the development of the Transport Infrastructure Condition Index (TICI), a composite metric designed to quantify the state of urban components and evaluate their influence on the overall sustainability of the transport network.

A key contribution of the study lies in the flexibility and applicability of the proposed model, which supports the prioritization of urban intervention measures through a systematic, structured, and reproducible methodology adaptable to different urban environments. Its straightforward mathematical formulation facilitates implementation, making it a practical decision-support instrument for public administrators seeking to enhance the quality of life of public transport users.

The findings reveal notable deficits in multiple corridors, particularly in areas with low tourist activity characterized by deteriorated infrastructure, limited accessibility provisions for individuals with disabilities, and inadequate public transport service frequency. Such conditions weaken multimodal connectivity and adversely affect daily mobility. Additionally, all analyzed corridors exceeded acceptable noise pollution thresholds, signaling risks to environmental and urban health.

The study further demonstrates that public investment has largely favored central and tourist-oriented avenues, leaving peripheral neighborhoods with insufficient integration and connectivity. This imbalance hampers the development of equitable and sustainable mobility. Consequently, the results underscore the importance of adopting a holistic planning approach that recognizes the city as an interconnected system, where public transportation functions as a structural axis of urban development.

In conclusion, this work offers a meaningful contribution to urban diagnostic methodologies through the application of multicriteria analysis tools. Its framework provides a foundation for future studies, evaluations of public policies, and strategic initiatives directed toward the advancement of sustainable urban mobility.