1. Introduction

Maintaining balance under static and dynamic conditions represents an integral part of human locomotion. It reflects a complex function involving afferent signals from peripheral receptors (proprioceptive muscle spindles, tactile receptors of plantar skin, and visual and statoacoustic organs), their processing by the central nervous system (specifically, the cerebellum), and the necessary corrective movement of the locomotor system.

Any distortion of these functions may lead to an impairment of the capability to maintain balance. On the afferent side, disruption of input information from specific peripheral receptors—such as proprioceptive muscle spindles, tactile receptors of the plantar skin, visual organs, or vestibular apparatus—can be partially compensated by the remaining sensory systems through central integration. For example, loss of visual input may be offset by enhanced reliance on proprioceptive and vestibular feedback. However, when motor function diminishes, particularly in muscles responsible for postural adjustments, this compensatory mechanism becomes insufficient. Reduced strength or delayed activation of postural muscles compromises corrective responses, resulting in a clear deterioration of balance control and an increased risk of instability.

Impairment of balance has been reported in diseases, e.g., Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke [

1], as well as after traumatic brain injury [

2], and after injuries like burns [

3] and operations involving central nervous system trauma or peripheral damage [

4].

Also, physical inactivity, e.g., related to aging, leads to deterioration of the capability to maintain balance under static and, namely, unstable conditions [

5,

6,

7]. Loss of this capability is considered one of the major factors contributing to the increasing incidence of falls and resulting injuries in the elderly population [

8].

On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that balance capabilities can be improved by means of various interventions such as, for example, systematic resistance exercise [

9,

10] or proprioceptive training [

11,

12]. In fact, restoration of the impaired balance control function is nowadays considered an important component of rehabilitation.

To evaluate the actual level and, namely, deficit of balance capabilities, a sufficiently reliable method for its quantification is needed. The same also applies to the evaluation of intervention efficiency focused on the improvement of balance.

The attempts to quantify postural sway have a fairly long history. Textbooks of neurology traditionally mention the Romberg sign (occurrence or augmentation of subjectively evaluated postural movements after blocking visual perception), which has already been described in the 19th century [

13,

14]. This test, however, in addition to being largely subjective, only enables the detection of rather serious impairment of balance and is not suitable for the fine quantitative assessment of postural function.

Later on, various more demanding tests have been proposed and used. As a typical example, the motor test called “Flamingo” can be used. The subject’s task is to stand with eyes closed on one leg as long as they can. However, the problem with this test, in addition to its poor reliability, is that results from larger groups do not follow a normal distribution [

15,

16].

With further developments, more advanced methods based on objective recording of horizontal sway movements have been applied. At the beginning of the 20th century, mechanical registering employing a pencil mounted to the vortex of the head was used [

14]. Being fairly impractical, this approach has not been widely utilized in clinical practice.

Nowadays, the most popular method is based on registering vertical force in the corners of dynamometric plates equipped with highly sensitive tensometers. Both three- and four-corner plates can be used for this purpose. Calculation of the instant position of the center of pressure is based on the distribution of vertical force into a particular corner of the plate. Instant values of force and the horizontal distance between the sensors are taken into account, creating the equations for the calculations. Sufficiently frequent sampling of instant position, e.g., at the rate of 100 Hz, enables the construction of the COP trace in the horizontal plane, called a posturographic curve.

To quantify the quality of stance, a posturographic curve can be analyzed to obtain parameters like the mean velocity of horizontal movement of COP, the mean distance of particular points of the curve from its theoretical center, the amount of movement on the mediolateral or anteroposterior axis, and others. Among those, as shown by Zemková (2014) [

17], the highest reliability for mean velocity (COP) (r = 0.89) and the mean distance from the center (r = 0.87) were described. In fact, the reliability of parameters obtained by such systems is high enough for their use in clinical settings.

Due to the wide accessibility of posturographic equipment in recent decades, quantitative assessments of postural sway during stance have become available as clinical tools, and an increasing number of physical therapists and physicians are customizing treatments for their patients based on the information from posturography [

18,

19,

20].

Most of the systems evaluate postural sway while a subject stands as still as possible on the stable platform. Alternatively, monitoring of the center of pressure movement can be carried out under unstable conditions, e.g., standing on the platform supported by springs. One such system has been designed in our laboratory. To calculate the instant position of the center of pressure, instead of force values in the four corners, the system uses the inclinations in two axes of the horizontal plane (more detailed description below). In recent years, several alternative approaches to balance assessment have been proposed, including unstable-platform systems and wearable inertial sensor-based solutions. While these approaches offer advantages in terms of portability or increased postural challenge, they often rely on complex signal processing and proprietary algorithms or do not provide direct COP-related measures comparable to force-plate outputs. As a result, their clinical interpretability and integration into established posturographic frameworks remain limited.

As with any new device, its application for practice requires evaluation of test–retest reliability.

Therefore, the aim of the paper is to describe the physical principles of a novel device, namely the calculation of horizontal COP displacement on an unstable spring-supported platform based on angle registration in two horizontal axes, and to evaluate its test–retest reliability under different visual and stability conditions in a heterogeneous adult population.

2. Materials and Methods

Instruments

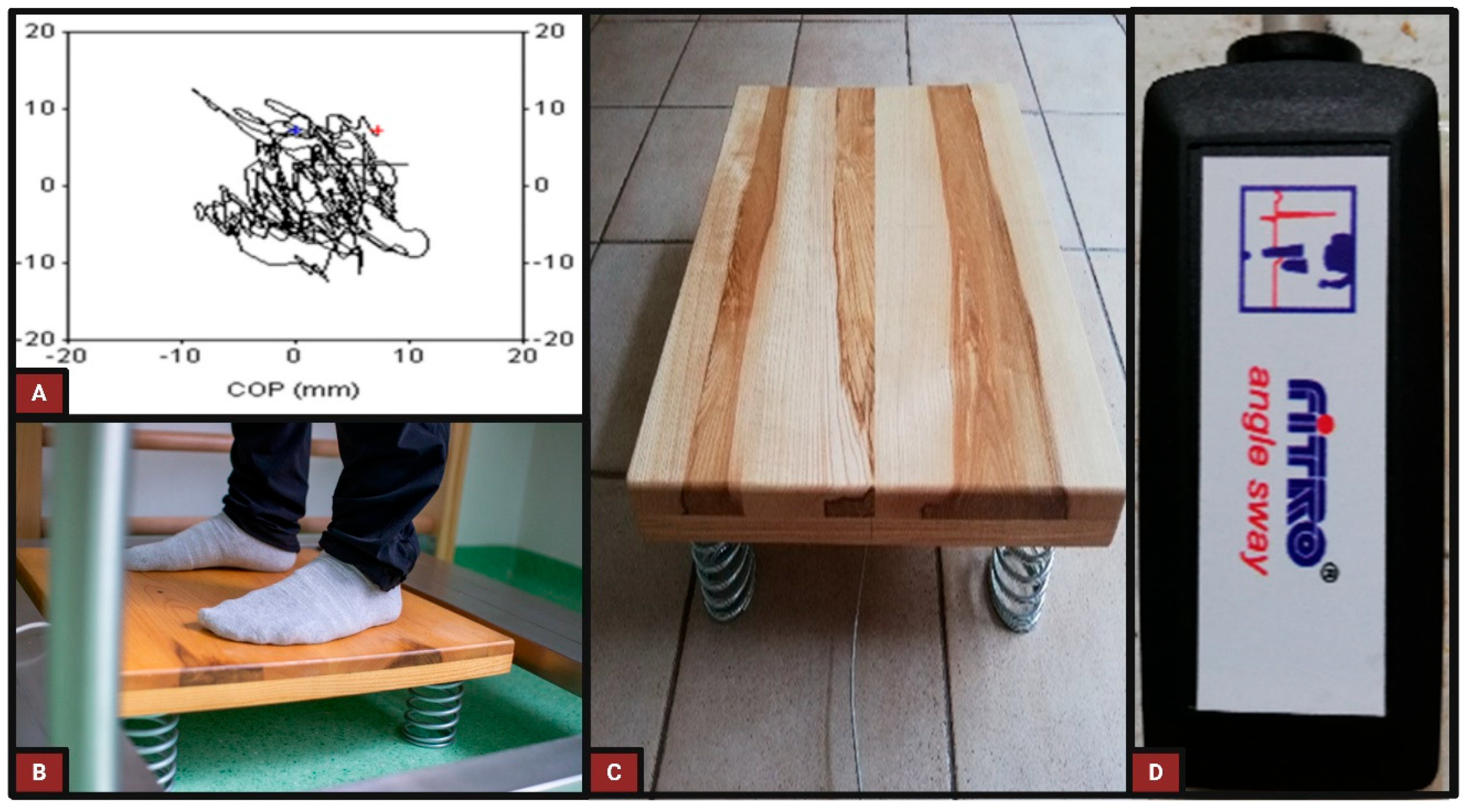

Two stabilographic systems were used for testing. A novel one, based on an unstable spring-supported platform (

Figure 1), and a traditional one using a stable platform.

A novel spring-supported posturographic system, similar to the classic force-plate-based equipment, also operates on the fact that shifting the center of gravity in a horizontal plane leads to changes in body weight distribution to the four corners of the platform. Changing the force acting on the supporting springs in the corners of the plate leads to its deviation from the horizontal plane in both mediolateral as well as anteroposterior axes. Angles in both axes are recorded using a special sensor, namely an inertial measurement unit (IMU; MPU-6050, TDK InvenSense, TDK Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) consisting of a three-dimensional accelerometer and a three-dimensional gyroscope, mounted to the underside of the plate. The accelerometer operated within a range of ±4 g with a resolution of 8192 LSB/g, and the gyroscope operated within a range of ±500°/s with a resolution of 65.5 LSB/°/s. Raw sensor signals were sampled at 100 Hz and processed using an internal sensor fusion algorithm with low-pass filtering applied to attenuate high-frequency noise.

The analog signals are processed by means of a 12-bit A/D converter and sampled by a computer at a rate of 100 Hz. Raw sensor data were processed using an internal sensor fusion algorithm to estimate platform orientation, and low-pass filtering was applied to attenuate high-frequency noise.

The digitized angle signals from the sensor are used for the calculation of the instant projection of the center of gravity on the horizontal plane of the platform using physical principles as follows.

Theoretically, if body weight is distributed equally into all 4 corners, all 4 springs will be loaded and shortened equally; hence, there will be no inclination in the X (mediolateral) nor Y (anteroposterior) axis of the platform, and the center of mass will be projected into the middle of the platform.

Moving the center of gravity along the X axis to the right would lead to higher stress and more pronounced shortening of right springs, with correspondingly lower stress and less pronounced shortening of left springs. Such a stress imbalance will result in inclination of the platform from the horizontal plane in the mediolateral axis. Shifting the center of gravity to the opposite direction would lead to the inclination of the platform to the left. The same applies to the shifting of the center of gravity along the anteroposterior axis.

The amount of inclination due to a given shift in the center of mass along mediolateral and anteroposterior axes while standing on the spring-supported platform of a given size depends on the weight of the subjects as well as on the elasticity of the springs and the distance between them. However, for a subject with a defined body weight standing on the platform with given spring elasticity and dimensions, inclination reflects the amount of shift in the center of gravity. Therefore, it is possible to calculate the shift in the center of gravity from the inclination of the platform in the mediolateral and anteroposterior axes.

The following formula, respecting laws of mechanics, is used for the calculation of X and Y coordinates from angles registered in these directions, taking into account the coefficient of elasticity of springs used, the side length of the quadruple platform (distance from center to center of the supporting spring), and the body mass of the subject tested:

X—coordinate in mediolateral axis (mm);

Y—coordinate in anteroposterior axis (mm);

tan α—tangent of the platform angle in the mediolateral axis (°);

tan β—tangent of the platform angle in the anteroposterior axis (°);

k—coefficient of elasticity (N/mm);

l—distance between the center of the springs (mm);

m—body mass (kg);

g—gravitational constant (9.81 m/s2).

The calculation of horizontal displacement from platform inclination is based on static equilibrium assumptions under quasi-static standing conditions, where inclination angles reflect shifts in the projection of the body’s center of mass, consistent with established biomechanical principles [

21].

The system calculates the coordinates of the instant projection of the center of gravity on the horizontal plane, which is herein referred to as the center of pressure. Although the platform inclination is mechanically induced by shifts in the projection of the body’s center of mass, the resulting horizontal displacement is treated as a COP-equivalent measure. Under quasi-static standing conditions, the projection of the center of mass and the center of pressure are closely coupled, and their horizontal displacements can be considered functionally equivalent for the assessment of postural sway. Minor deviations between COM projection and COP may occur during rapid corrective movements; however, their influence on mean COP velocity during quiet standing is considered negligible.

In the present study, the square platform with a side dimension of 500 mm, supported by four springs with a coefficient of elasticity of 12 N/mm, was used. The effective side distance between the centers of the supporting springs was 390 mm.

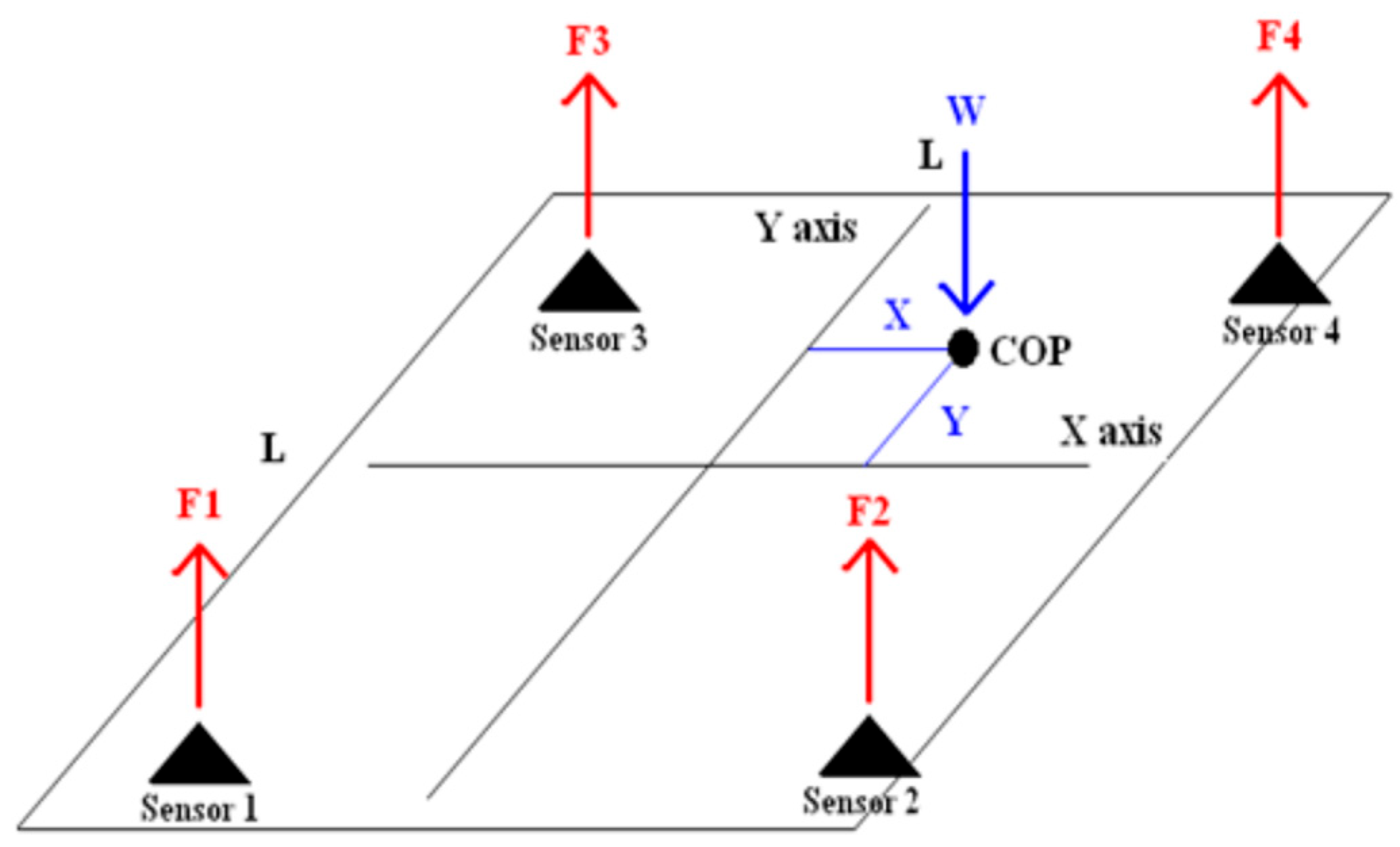

To compare the results with the traditional system, a firm quadrate platform with 4 force sensors was used. During quiet standing, the sum of vertical forces (F1 to F4) generated in the 4 corner sensors equals body weight (product of body mass m and gravitational constant g), generating a force vector, whose projection on the platform is termed as center of pressure (COP). The location of this projection depends on the force distribution among particular sensors. Its coordinates can be calculated using differences in force from pairs of sensors in the mediolateral and anteroposterior axes of a transversal plane (

Figure 2) using the formulas as follows:

X—coordinate in mediolateral axis (mm);

Y—coordinate in anteroposterior axis (mm);

F1—force measured in rear left sensor (N);

F2—force measured in rear right sensor (N);

F3—force measured in front left sensor (N);

F4—force measured in front right sensor (N);

l—distance between the center of the sensors (mm);

m—body mass (kg);

g—gravitational constant (9.81 m/s2).

In both systems, sensor signals were AD-converted, and COP position was calculated at the rate of 100 Hz. In addition, COP velocity was calculated from distances between subsequent positions covered in sampling intervals of 10 ms.

Subjects

With the aim of creating a heterogeneous group in terms of level of balance capabilities, 105 subjects of different sexes, ages, heights, and weights were recruited to participate in the study. Their basic characteristics are in

Table 1. All participants provided written informed consent before the beginning of the study and were notified of their rights to withdraw from the study at any time. The study protocol followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki 2000 and its later amendments from 2013.

The exclusion criteria were the following:

Present disorders, injuries, or impaired mobility related to the musculoskeletal system.

Present acute or chronic infections that would prevent individuals from participating in the study.

Present cardiovascular, neurological, cancerous, metabolic, autoimmune, or other diseases that would hinder an individual’s participation in the study.

Testing procedures

All subjects underwent, within one testing session, six 30 s stands on an unstable spring-supported platform and six on a firm platform. On each device, half of the trials were performed with the subject’s eyes open (EO) and 3 with eyes closed (EC). Tests were performed in random order and separated by a 1 min rest period, during which subjects stepped off the test platform. Subjects stood 2 m from a white wall. In order to foster the repeatability of measurements, participants were given standardized instructions to remain as still as possible [

22]. The selection of three 30 s trials was based on previously established posturographic protocols applied on a firm platform [

17], which were adopted in the present study to ensure methodological consistency between the firm and unstable conditions.

Statistical analysis

Data were screened for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov one-sample test.

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation) were computed separately for each trial for both conditions, i.e., EO and EC.

In addition to basic descriptive statistics, data from repeated measurements were analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA to obtain information on variance (total, between subjects, and between repeated measurements) as well as on the effect of trial order.

Intraclass correlation coefficients for repeated trials with EO and EC were calculated using a two-way random-effects model with absolute agreement, based on the average of three trials [ICC(2,3)], as described by McGraw and Wong (1996) [

23].

A paired t-test was employed to test the difference in results obtained on a stabilographic system based on an unstable and firm platform, as well as between results obtained under different conditions (eyes open and closed, respectively).

Measurement errors were calculated using the procedure for repeated multiple measurements as described by Renner (1970) [

24].

To account for the fully crossed within-subject design (platform × visual condition) and repeated measurements while simultaneously estimating main and interaction effects, COP mean velocity was subsequently analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) to estimate variance components underlying repeated measurements and to complement the ICC-based reliability analysis.

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows (version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs), which were obtained using conventional statistical methods.

3. Results

Mean values of all repeated measurements showed significantly higher values on the spring-supported platform compared with the firm platform under eyes-closed conditions (

Table 2), corresponding to an approximately 42% increase in COP velocity. No significant difference in mean COP velocity was observed when tests were performed under visual control. On the unstable platform, COP velocity during eyes-closed trials was more than twice as high as during eyes-open trials, representing an increase of approximately 114%.

Mean values and standard deviations of repeated trials are depicted in

Table 3. The ANOVA of test results on the firm platform revealed the significant effect of trial order under both conditions, EO as well as EC (F = 4.81,

p = 0.009; F’= 6.3,

p = 0.002). However, as proven by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests, the only significant difference was between the values from the first and the second trials. Differences between the second and third trials have not reached statistical significance. This means that though there is a certain learning effect, this only occurs between the initial two trials.

On the other hand, analyses of repeated measurements on an unstable spring-supported platform did not show any effect of trial order. Though rather surprising, there seems to be no learning effect resulting from repeating trials on an unstable spring-supported platform.

Table 4 contains intraclass correlation coefficients for the COP horizontal movement velocity of three repeated trials on the firm and unstable platform with EO and EC.

The analyses of single values of three repeated trials with eyes open demonstrated moderate repeatability of the COP movement velocity on both the firm platform (ICC = 0.794) as well as the unstable spring-supported one (ICC = 0.761).

When three repeated single measurements were performed with eyes closed, intraclass coefficients showed slightly lower values on the firm (0.723) platform but higher values on the unstable platform (0.902).

However, when the testing procedure consisted of three attempts, and average values were taken as the criterion of the test, analyses of results revealed higher ICC values for COP movement velocity on both platforms (ICC = 0.920, for the firm platform; ICC = 0.902, for the spring-supported system), indicating high reliability.

As presented in

Table 5, measurement errors for particular platforms and conditions (eyes open and closed, respectively) revealed values between 8.8 and 13.2% with rather minor differences between particular systems. However, measurement error tends to be lower if average values from three trials are used as the criterion of the test.

These reliability findings are consistent with the variance structure identified by the linear mixed-effects model, which revealed substantial between-participant variability and comparatively low within-subject variability across repeated trials.

The results of the LMM, when applied, revealed a significant main effect of the platform (β = 8.84, SE = 0.75, z = 11.75, p < 0.001), indicating substantially higher COP velocity on the unstable platform compared with the firm surface. A significant main effect of visual condition was also observed (β = −4.61, SE = 0.75, z = −6.13, p < 0.001), with lower COP velocity during EO relative to EC trials. Importantly, a significant platform × visual condition interaction was detected (β = −9.46, SE = 1.06, z = −8.89, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the stabilizing effect of visual input was condition-dependent. Specifically, the reduction in COP velocity associated with visual control was markedly greater on the unstable platform, indicating increased reliance on visual feedback when somatosensory demands were elevated.

The model intercept (β = 15.66, SE = 0.82, p < 0.001) corresponded to COP velocity measured during EC trials on the firm platform. Random-effects analysis revealed substantial between-participant variability (random intercept variance = 40.28), underscoring pronounced inter-individual differences in baseline postural sway.

When trial number was included as a covariate in an extended model, a small but significant effect of trial repetition was observed (β = −1.22, p < 0.001), indicating a modest overall reduction in COP velocity across repeated trials. This finding is consistent with the learning effect detected by repeated-measures ANOVA on the firm platform and supports the interpretation that adaptation occurs primarily during the initial repetitions. Importantly, inclusion of trial number did not materially alter the magnitude or significance of the main effects or the platform × visual condition interaction, confirming the robustness of the primary results.

4. Discussion

This study was focused on evaluating the reliability of a novel posturographic system based on a spring-supported unstable platform and comparing its performance with a traditional firm platform under different visual conditions. The aim was to determine whether the new system provides accurate and repeatable measurements of center of pressure (COP) displacement and to explore how visual input influences balance control in stable versus unstable environments.

Contrary to our expectation, testing with open eyes revealed no significant difference in COP velocity in the horizontal plane while standing on a spring-supported (10.39 mm/s) and firm platform (11.05 mm/s). However, closing the eyes led to a significant increase in COP velocity, which was significantly higher on the spring-supported platform (by 11.81 mm/s to 22.20 ± 16.9 mm/s) than on the firm system (by 4.61 mm/s to 15.66 ± 5.92 mm/s). It appears that visual information is more important under unstable than stable conditions. This is also corroborated by the fact that closing eyes leads to an average increase in COP velocity by about 42%; however, on an unstable spring-supported platform, it increases by more than 113%.

A significant difference was observed between the first and second trials, suggesting a learning effect on the firm platform. This indicates that at least two attempts should be made to obtain the best value from the subject. No learning effect has been found for repeated trials on a spring-supported unstable platform. While a small overall effect of trial repetition was detected by the linear mixed-effects model, platform-specific analyses demonstrated that learning effects were confined to the firm platform and did not affect measurements obtained on the unstable spring-supported platform. However, considering a better intraclass coefficient and lower measurement error for mean values from three trials on both systems, it can be suggested to use the average of three trials as a criterion for balance capabilities.

Calculation of intraclass correlation coefficients for repeated measurements with open eyes using an unstable spring-supported platform yielded the values of ICC in a similar range as those obtained on the same subjects on the stable platform.

However, the same testing procedure with eyes closed revealed substantially higher intraclass correlation coefficient on both platforms, namely on the unstable one. This suggests greater variability between the subjects, which means that the test with the closed eyes enables better differentiation between individuals with various levels of balance capabilities.

A similar rationale applies to the use of an accelerometer for assessing movement patterns and balance. As outlined by Welk et al. (2019) [

25] in

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, the quality of such measurement procedures can be evaluated by examining the ratio of between-subject variance (reflecting individual differences in balance capability) to within-subject variance across repeated trials (reflecting measurement reliability). A high ratio indicates strong reliability and supports the method’s suitability for clinical and field-based applications.

The fairly high coefficients of intraclass correlation on both systems indicate that the reliability of the measurements on the spring-based platform is very similar to that obtained on the standard firm platform. According to widely accepted guidelines, ICC values ≥ 0.80 indicate high reliability, while values between 0.60 and 0.79 suggest moderate reliability [

23,

26,

27]. Reporting 95% confidence intervals further enhances the interpretability of reliability estimates, as recommended by Koo and Li (2016) [

28].

ICC values for repeated trials obtained on an unstable spring-supported platform match repeatability reported for the parameters of postural sway obtained on the already established stabilographic systems used in clinical settings such as, for example, Neurocom and Biodex [

29,

30]. This comparison is indirect and based on previously reported reliability ranges.

Though there are test procedures for the assessment of functional capabilities showing higher intraclass coefficients (some procedures measuring strength up to 0.980), values around 0.900 are still considered high enough for the method to be used in the practice of functional evaluation.

Similar results were calculated for outcome measures from the NeuroCom testing, with high test–retest reliability observed for endpoint excursion (ICC [2,k] = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.73, 0.94), high reliability observed for movement velocity (ICC [2,k] = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.59, 0.91), and moderate reliability observed for directional control (ICC [2,k] = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.40, 0.86) [

31].

The lack of differences in ICC results confirms that the novel spring-supported posturographic system provides a methodologically sound alternative to traditional static platforms for balance assessment and may be particularly beneficial for populations with impaired postural control, such as older adults, individuals with neurological disorders, or patients undergoing balance-oriented rehabilitation.

Results of the linear mixed-effects modeling approach corroborated and extended the findings obtained from descriptive statistics, ANOVA, and ICC analyses by providing a unified statistical framework that simultaneously accounted for repeated measurements, inter-individual variability, and interaction effects, while avoiding inflation of Type I error associated with multiple pairwise comparisons.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study is that potential age- and sex-related effects on postural sway were not examined. Although the heterogeneous adult sample strengthens the generalizability of the reliability findings, subgroup analyses were beyond the scope of this study. In addition, criterion validity relative to a gold-standard force-plate system was not assessed, as the primary focus of the present study was test–retest reliability.

5. Conclusions

Under eyes-open conditions, the mean velocity of COP in the horizontal plane on the unstable spring-supported platform was similar to that on the firm stabilographic platform.

Closing the eyes increases COP velocity by approximately 42% on a firm platform, but by almost 113% on an unstable system, indicating that visual control plays a more important role in balance control while standing on an unstable platform than on a firm one.

Analyses of repeated measurement using a posturographic system based on vertical force measurement on the firm, stable platform and a novel system calculating center of pressure from angles of x and y axes in the horizontal plane on a spring-supported platform revealed that the novel, inexpensive unstable system offers similar reliability to traditional systems.

With eyes closed, an unstable system enables better differentiation between subjects with various levels of balance capabilities.

Data also showed that better reliability can be achieved if the mean value of three attempts is used as a criterion for balance, as compared to the value obtained by a single attempt.

A relatively low-cost, unstable stabilographic system based on inexpensive components could increase accessibility of reliable balance assessment in healthcare institutions, not only in clinical settings but also for broader screening of individuals with impaired balance and increased risk of falling. Further studies are needed to establish criterion validity and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions based on measurements obtained using this system.