Response Surface Methodology in the Photo-Fenton Process for COD Reduction in an Atrazine/Methomyl Mixture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

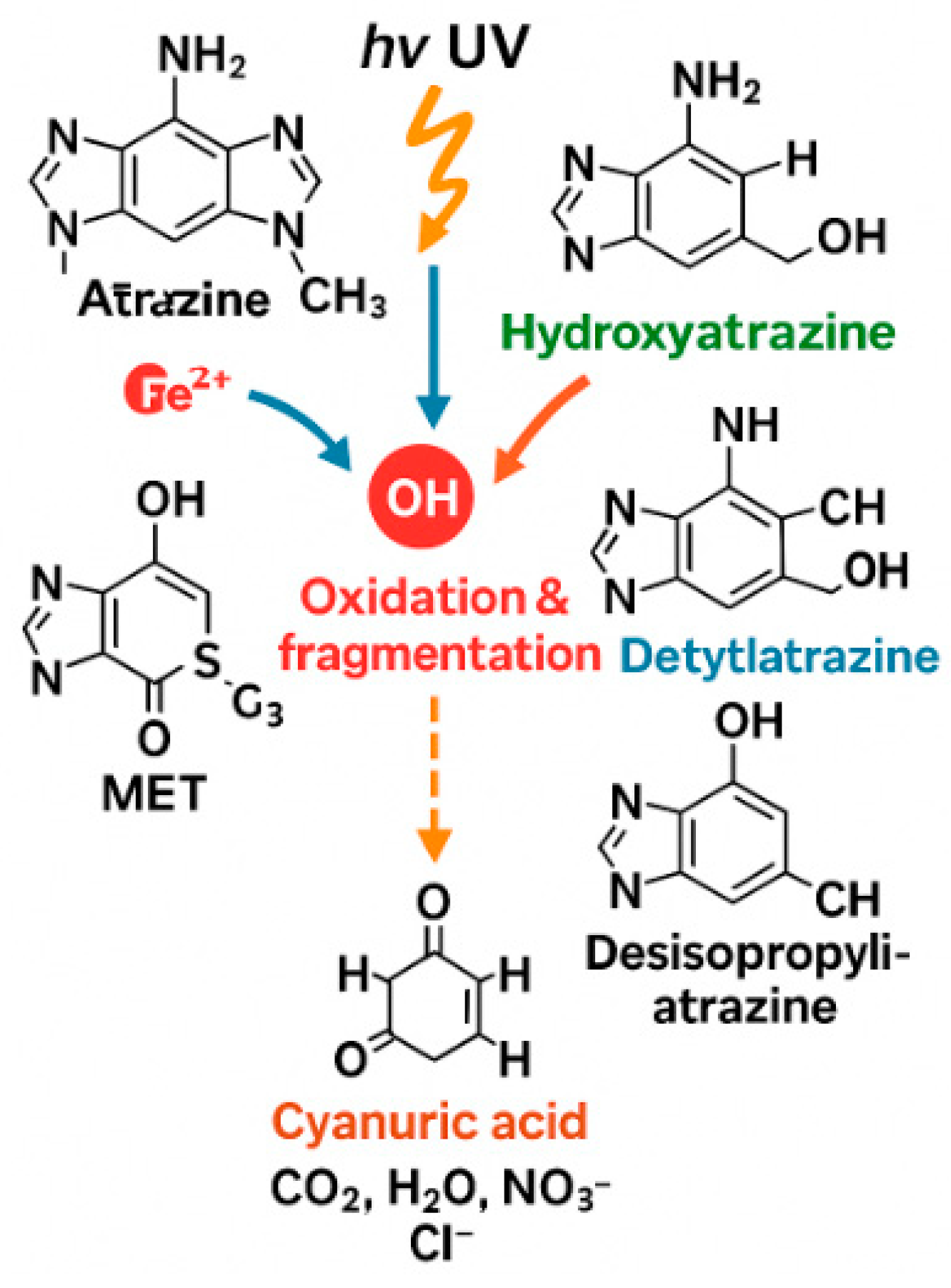

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of the Aqueous Solution of Atrazine and Methomyl

2.2. Operation of the Photo-Fenton System

2.3. Construction of the Response Surface Method Design

2.3.1. Phase 1—23 Factorial Design for Screening

2.3.2. Phase 2—Center Points for Curvature Detection

2.3.3. Phase 3—Steepest-Ascent

2.3.4. Phase 4—Central Composite Design (CCD)

2.4. Response Surface Model—Composite Central Design

3. Results

3.1. Response Surface Model Result—Composite Central Design

3.1.1. Simple Factorial Design for Screening

3.1.2. Center Points for Curvature Detection

3.1.3. Upward Scaling

3.2. CCD—RSM for Modeling and Optimization

3.3. Optimal CCD-RSM Conditions

4. Discussion

4.1. Statistical Robustness and Model Reliability

4.2. Influence of Process Variables on COD Removal

4.3. Comparison with Literature and TiO2 Systems

4.4. Mechanistic Interpretation (Radical Generation)

4.5. Reproducibility of Optimized Conditions

4.6. Limitations and Practical Implications

- Optimization of reagent dosages and recovery/reuse of iron (to reduce sludge and costs).

- Economic and life-cycle analysis (reactant cost, sludge disposal, energy for mixing/flow).

- Pilot-scale tests under real effluent conditions (variable flow, pollutant load, matrix complexity).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOP | Advanced Oxidation Process |

| ATZ | Atrazine |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| MET | Methomyl |

| •OH | Hydroxyl Radical |

| PRESS | Predicted Residual Error Sum of Squares |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

References

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Liu, G.; Balaram, V.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Lu, Z.; Stock, F.; Carmona, E.; Teixeira, M.R.; Picos-Corrales, L.A. Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2311–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Naranjo, C.E.; Guerrero, V.H.; Villamar-Ayala, C.A. Emerging contaminants and their removal from aqueous media using conventional/non-conventional adsorbents: A glance at the relationship between materials, processes, and technologies. Water 2023, 15, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, L.; Solomon, K.; Sibley, P.; Hall, K.; Keen, P.; Mattu, G.; Linton, B. Sources, pathways, and relative risks of contaminants in surface water and groundwater: A perspective prepared for the Walkerton inquiry. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2002, 65, 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, U.; Rafi, F.; Naveed, M.; Mehdi, S.M.; Murtaza, G.; Niazi, A.G.; Mehmood, H. Pesticide pollution in an aquatic environment. In Freshwater Pollution and Aquatic Ecosystems; Apple Academic Press: Point Pleasant, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 131–163. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Chauhan, A.; Datta, S.; Wani, A.B.; Singh, N.; Singh, J. Toxicity, degradation and analysis of the herbicide atrazine. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struger, J.; Grabuski, J.; Cagampan, S.; Sverko, E.; Marvin, C. Occurrence and distribution of carbamate pesticides and metalaxyl in southern Ontario surface waters 2007–2010. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 96, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Boussetta, N.; Enderlin, G.; Merlier, F.; Grimi, N. Degradation of residual herbicide atrazine in agri-food and washing water. Foods 2022, 11, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Pang, S.; Huang, Y.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. Current approaches to and future perspectives on methomyl degradation in contaminated soil/water environments. Molecules 2020, 25, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, S.; Panghal, P.; Singh, S.; Deep, A.; Kumar, S. Biomass-based adsorbents for wastewater remediation: A systematic review on removal of emerging contaminants. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 111880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Rangabhashiyam, S.; Verma, P.; Singh, P.; Devi, P.; Kumar, P.; Hussain, C.M.; Gaurav, G.K.; Kumar, K.S. Environmental and health impacts of contaminants of emerging concerns: Recent treatment challenges and approaches. Chemosphere 2021, 272, 129492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qian, H.; Cui, J.; Ge, Z.; Shi, J.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L. Endocrine toxicity of atrazine and its underlying mechanisms. Toxicology 2024, 505, 153846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsioroski, A.; Mourikes, V.E.; Flaws, J.A. Endocrine disruptors in water and their effects on the reproductive system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, C.A.; Pereira, T.C.B.; Teodoro, L.D.S.; Altenhofen, S.; Rübensam, G.; Bonan, C.D.; Bogo, M.R. Acute toxicity of methomyl commercial formulation induces morphological and behavioral changes in larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2022, 89, 107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, F.K. Effect of Methomyl on Fetal Development in Female Rats. Egypt. J. Chem. Environ. Health 2018, 4, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörtl, M.; Kereki, O.; Darvas, B.; Klátyik, S.; Vehovszky, Á.; Győri, J.; Székács, A. Study on soil mobility of two neonicotinoid insecticides. J. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4546584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Bi, G.; Ward, T.J.; Li, L. Adsorption and degradation of neonicotinoid insecticides in agricultural soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 47516–47526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todey, S.A.; Fallon, A.M.; Arnold, W.A. Neonicotinoid insecticide hydrolysis and photolysis: Rates and residual toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, H.I.; Abdel-Latif, H.A.; ElMazoudy, R.H.; Abdelwahab, W.M.; Saad, M.I. Effect of methomyl on fertility, embryotoxicity and physiological parameters in female rats. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.-A.; Chang, S.-S.; Chen, H.-Y.; Tsai, K.-F.; Lee, W.-C.; Wang, I.-K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Liu, S.-H.; Weng, C.-H.; Huang, W.-H. Human poisoning with methomyl and cypermethrin pesticide mixture. Toxics 2023, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo Neves, T.; Camparotto, N.G.; de Vargas Brião, G.; Mastelaro, V.R.; Vieira, M.G.A.; Dantas, R.F.; Prediger, P. Synergetic effect on the adsorption of cationic and anionic emerging contaminants on polymeric membranes containing Modified-Graphene Oxide: Study of mechanism in binary systems. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavel, S.P.; Kumar, G. Recent progress in mineralization of emerging contaminants by advanced oxidation process: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 341, 122842. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, S.; Wang, R.; Wei, M.; Hu, X.; Song, X. Advanced oxidation processes mediated by Schwertmannite for the degradation of organic emerging contaminants: Mechanism and synergistic approach. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Huang, X.; Zhu, G.; Pang, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Z. Unraveling the triple mechanisms of advanced coagulation for removal of emerging and conventional contaminants: Oxidation, hydrolytic coagulation and surface hydroxylation adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.L.; Sajjadi, S.M. Predicting rejection of emerging contaminants through RO membrane filtration based on ANN-QSAR modeling approach: Trends in molecular descriptors and structures towards rejections. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 23754–23771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Tang, X.; Gong, W.; Liang, H. Insight into the role of biogenic manganese oxides-assisted gravity-driven membrane filtration systems toward emerging contaminants removal. Water Res. 2022, 224, 119111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Hu, L.; Zhang, H.; Lin, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Gong, W.; Liang, H. Toward emerging contaminants removal using acclimated activated sludge in the gravity-driven membrane filtration system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, W.; Feng, J.; Xu, H.; Zhu, C.; Yan, W.; Jia, X.; Song, H. Enhanced removal of aromatic emerging contaminants through the electrochemical co-degradation with polystyrene microplastics. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 509, 161535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Tabucanon, A.S.; Amarakoon, A.M.S.N.; Xiao, K.; Huang, X. Recent advances in membrane and electrochemical hybrid technologies for emerging contaminants removal. Water Cycle 2025, 6, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, A.S.; Lumbaque, E.C.; Radjenovic, J. Electrochemical removal of contaminants of emerging concern with manganese oxide-functionalized graphene sponge electrode. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Chang, J.; Ding, J.; Yin, Y. Impact of coexisting components on the catalytic ozonation of emerging contaminants in wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Deng, S.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y. Modelling of emerging contaminant removal during heterogeneous catalytic ozonation using chemical kinetic approaches. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bai, Z. Fe-based catalysts for heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of emerging contaminants in water and wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 312, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lei, J.; Sun, S.-P. High-valent ferryl intermediates generation, reactivity and kinetic characterization with contaminants of emerging concern via a facile photo-Fenton competition kinetic methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 492, 138216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Júnior, F.E.B.; Marin, B.T.; Mira, L.; Fernandes, C.H.M.; Fortunato, G.V.; Almeida, M.O.; Honório, K.M.; Colombo, R.; de Siervo, A.; Lanza, M.R.V.; et al. Monitoring Photo-Fenton and Photo-Electro-Fenton process of contaminants emerging concern by a gas diffusion electrode using Ca10-xFex-yWy(PO4)6(OH)2 nanoparticles as heterogeneous catalyst. Chemosphere 2024, 361, 142515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, S.; Lorca, J.; Vidal, J.; Calzadilla, W.; Toledo-Neira, C.; Aranda, M.; Miralles-Cuevas, S.; Cabrera-Reina, A.; Salazar, R. Removal of contaminants of emerging concern by solar photo electro-Fenton process in a solar electrochemical raceway pond reactor. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 169, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Baltrus, J.P.; Williams, C.; Knopf, A.; Zhang, L.; Baltrusaitis, J. Heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like degradation of emerging pharmaceutical contaminants in wastewater using Cu-doped MgO nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2022, 630, 118468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, A.; Hussain, A.; Nawaz, M.; Imran, M.; Ali, Z.; Haq, S.U. The impact of prolonged use and oxidative degradation of Atrazine by Fenton and photo-Fenton processes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Júnior, O.; Santos, M.G.B.; Nossol, A.B.S.; Starling, M.C.V.M.; Trovó, A.G. Decontamination and toxicity removal of an industrial effluent containing pesticides via multistage treatment: Coagulation-flocculation-settling and photo-Fenton process. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 147, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria Florez, P.L.; Los Weinert, P.; Lopes Tiburtius, E.R. Assessment of UV-Vis LED-assisted Photo-Fenton Reactor for Atrazine Degradation in Aqueous Solution. Orbital Electron. J. Chem. 2021, 13, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.-M.; Cheng, S.-T.; Shen, X.-F.; Pang, Y.-H. Bimetallic MOF sulfurized In2S3/Fe3S4 for efficient photo-Fenton degradation of atrazine under weak sunlight: Mechanism insight and degradation pathways. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Silva, F.; Masceno, G.P.; Panicio, P.P.; Imoski, R.; Prola, L.D.T.; Vidal, C.B.; Xavier, C.R.; Ramsdorf, W.A.; Passig, F.H.; de Liz, M.V. Removal of micropollutants by UASB reactor and post-treatment by Fenton and photo-Fenton: Matrix effect and toxicity responses. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, W.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Hussain, I.; Huang, R. Insight into the degradation of methomyl in water by peroxymonosulfate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.A.; Alwared, A.I.; Shakhir, K.S.; Sulaiman, F.A. Synthesis, characterization of FeNi3@ SiO2@ CuS for enhance solar photocatalytic degradation of atrazine herbicides: Application of RSM. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 16, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gawad, H.A.; Ghaly, M.Y.; El Hussieny, N.F.; Abdel Kreem, M.; Reda, Y. Novel collector design and optimized photo-fenton model for sustainable industry textile wastewater treatment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, M.; Pérez, J.; López, J.; Oller, I.; Rodríguez, S. Degradation of a four-pesticide mixture by combined photo-Fenton and biological oxidation. Water Res. 2009, 43, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdessalem, A.; Bellakhal, N.; Oturan, N.; Dachraoui, M.; Oturan, M. Treatment of a mixture of three pesticides by photo- and electro-Fenton processes. Desalination 2010, 250, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekkaoui, C.; Berrama, T.; Dumoulin, D.; Billon, G.; Kadmi, Y. Optimal degradation of organophosphorus pesticide at low levels in water using fenton and photo-fenton processes and identification of by-products by GC-MS/MS. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenone, A.V.; Conte, L.O.; Botta, M.A.; Alfano, O.M. Modeling and optimization of photo-Fenton degradation of 2, 4-D using ferrioxalate complex and response surface methodology (RSM). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 155, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, L.R.; Irani, M.; Pourahmad, H.; Sayyafan, M.S.; Haririan, I. Simultaneous degradation of phenol and paracetamol during photo-Fenton process: Design and optimization. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 47, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, P.; Sakkas, V.A.; Medana, C.; Vlachou, A.D.; Dal Bello, F.; Albanis, T.A. Chemometric assessment and investigation of mechanism involved in photo-Fenton and TiO2 photocatalytic degradation of the artificial sweetener sucralose in aqueous media. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, M.; Qourzal, S.; Barka, N.; Assabbane, A.; Ait-Ichou, Y. Methomyl degradation in aqueous solutions by Fenton’s reagent and the photo-Fenton system. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 61, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, S.; Tsenter, I.; Garkusheva, N.; Beck, S.E.; Matafonova, G.; Batoev, V. Evaluating (sono)-photo-Fenton-like processes with high-frequency ultrasound and UVA LEDs for degradation of organic micropollutants and inactivation of bacteria separately and simultaneously. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.A.; He, X.; Khan, H.M.; Shah, N.S.; Dionysiou, D.D. Oxidative degradation of atrazine in aqueous solution by UV/H2O2/Fe2+, UV/S2O82−/Fe2+ and UV/HSO5−/Fe2+ processes: A comparative study. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 218, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wu, D.; Hu, Z. Impact of hydraulic retention time on organic and nutrient removal in a membrane coupled sequencing batch reactor. Water Res. 2014, 55, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shannag, M.; Lafi, W.; Bani-Melhem, K.; Gharagheer, F.; Dhaimat, O. Reduction of COD and TSS from paper industries wastewater using electro-coagulation and chemical coagulation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. Multiple regression analysis: Use adjusted R-squared and predicted R-squared to include the correct number of variables. Minitab Blog 2013, 13. Available online: https://blog.minitab.com/en/blog/adventures-in-statistics-2/multiple-regession-analysis-use-adjusted-r-squared-and-predicted-r-squared-to-include-the-correct-number-of-variables (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Frost, J. How to interpret adjusted R-squared and predicted R-squared in regression analysis. Retrieved Oktober 2019, 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj, E.A.; Mulualem, Y.; Molla, F.; Yayehrad, A.T.; Belete, A. Formulation optimization of furosemide floating-bioadhesive matrix tablets using waste-derived Citrus aurantifolia peel pectin as a polymer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiralal Dhage, B.; Khedkar, N.K. Predictive machine learning and printing parameter optimization for enhanced impact performance of 3D-printed Onyx-Kevlar composites. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambom, A.Z.; Akritas, M.G. NonpModelCheck: An R package for nonparametric lack-of-fit testing and variable selection. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 77, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshraftar, Z. Modeling of CO2 solubility and partial pressure in blended diisopropanolamine and 2-amino-2-methylpropanol solutions via response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myśliwiec, P.; Szawara, P.; Kubit, A.; Zwolak, M.; Ostrowski, R.; Derazkola, H.A.; Jurczak, W. FSW optimization: Prediction using polynomial regression and optimization with hill-climbing method. Materials 2025, 18, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, M.; Claeskens, G.; Hart, J.D. Testing lack of fit in multiple regression. Biometrika 2000, 87, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-K.; Lee, Y.-J.; Son, C.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; Lee, C.-G. Alternative assessment of machine learning to polynomial regression in response surface methodology for predicting decolorization efficiency in textile wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2025, 370, 143996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesinos López, O.A.; Montesinos López, A.; Crossa, J. Overfitting, Model Tuning, and Evaluation of Prediction Performance. In Multivariate Statistical Machine Learning Methods for Genomic Prediction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.I.; Abunama, T.; Javed, M.F.; Bux, F.; Aldrees, A.; Tariq, M.A.U.R.; Mosavi, A. Modeling surface water quality using the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system aided by input optimization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.F.; Hossain, Z.; Ans, M.; Al-Anzil, B.S.; Ullah, A. Implementation of statistical response surface methodology with desirability function for ion-exchange-based selective demineralization of municipal wastewater and tap water for drinking purposes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 7753–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Gerber, J.S.; MacDonald, G.K.; West, P.C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Nobre, J.; da Motta Singer, J. Residual analysis for linear mixed models. Biom. J. J. Math. Methods Biosci. 2007, 49, 863–875. [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos, D.; Moustaki, I. Generalized latent variable models with non-linear effects. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2008, 61, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passerine, B.F.G.; Breitkreitz, M.C. Important Aspects of the Design of Experiments and Data Treatment in the Analytical Quality by Design Framework for Chromatographic Method Development. Molecules 2024, 29, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popli, D.; Gupta, M. Rotary ultrasonic machining of ni based alloys. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Technol. 2017, 3, 140–151. [Google Scholar]

- Alalm, M.G.; Tawfik, A.; Ookawara, S. Comparison of solar TiO2 photocatalysis and solar photo-Fenton for treatment of pesticides industry wastewater: Operational conditions, kinetics, and costs. J. Water Process Eng. 2015, 8, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Golder, A. Fenton, Photo-Fenton, H2O2 Photolysis, and TiO2 Photocatalysis for Dipyrone Oxidation: Drug Removal, Mineralization, Biodegradability, and Degradation Mechanism. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljubourya, D.; Palaniandy, P.; Aziz, H.; Feroz, S. Comparative Study to the Solar Photo-Fenton, Solar Photocatalyst of TiO2 and Solar Photocatalyst of TiO2 Combined with Fenton Process to Treat Petroleum Wastewater by RSM. J. Pet. Environ. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, S.; Afroze, S.; Roni, K. Raw Industrial Wastewater Treatment Using Fenton, Photo Fenton and Photo Catalytic: A Comparison Study. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 801. [Google Scholar]

- Gernjak, W.; Maldonado, M.; Malato, S.; Cáceres, J.; Krutzler, T.; Glaser, A.; Bauer, R. Pilot-plant treatment of olive mill wastewater (OMW) by solar TiO2 photocatalysis and solar photo-Fenton. Sol. Energy 2004, 77, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al deen Atallah, D.; Palaniandy, P.; Aziz, H.B.A.; Feroz, S. Evaluating the TiO2 as a solar photocatalyst process by response surface methodology to treat the petroleum waste water. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2015, 1, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al deen Atallah, D.; Palaniandy, P.; Aziz, H.B.A.; Feroz, S. Treatment of petroleum wastewater using combination of solar photo-two catalyst TiO2 and photo-Fenton process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, D.T.; Parikh, S.P. Solar light induced photocatalysis for treatment of high COD pharmaceutical effluent with recyclable Ag-Fe codoped TiO2: Kinetics of COD removal. Curr. World Environ. 2020, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Z.; Lin, Q. Photocatalytic improvement of Y3+ modified TiO2 prepared by a ball milling method and application in shrimp wastewater treatment. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 14609–14620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweinor Tetteh, E.; Rathilal, S. Adsorption and photocatalytic mineralization of bromophenol blue dye with TiO2 modified with clinoptilolite/activated carbon. Catalysts 2020, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós-Pérez, A.; Lillo-Ródenas, M.Á.; Román-Martínez, M.D.C.; García-Muñoz, P.; Keller, N. TiO2 and TiO2-carbon hybrid photocatalysts for diuron removal from water. Catalysts 2021, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speltini, A.; Maraschi, F.; Sturini, M.; Caratto, V.; Ferretti, M.; Profumo, A. Sorbents Coupled to Solar Light TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Olive Mill Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Photoenergy 2016, 2016, 8793841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, A.; von Sonntag, C.; Schmidt, T.C. Hydroxyl radical yields in the Fenton process under various pH, ligand concentrations and hydrogen peroxide/Fe (II) ratios. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatello, J.J.; Oliveros, E.; MacKay, A. Advanced oxidation processes for organic contaminant destruction based on the Fenton reaction and related chemistry. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 36, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Bolton, J.R.; Belosevic, M.; El Din, M.G. Photodegradation of emerging micropollutants using the medium-pressure UV/H2O2 advanced oxidation process. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2881–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, B.M.; Zyadah, M.A.; Ali, M.Y.; El-Sonbati, M.A. Pre-treatment of composite industrial wastewater by Fenton and electro-Fenton oxidation processes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbański, N.; Beręsewicz, A. Generation of · OH initiated by interaction of Fe2+ and Cu+ with dioxygen; comparison with the Fenton chemistry. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2000, 47, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.A.; Khan, A.H.; Tiwari, P.; Zubair, M.; Naushad, M. New insights into the integrated application of Fenton-based oxidation processes for the treatment of pharmaceutical wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 44, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, R.; Maleki, A.; Jafari, A.; Mazloomi, S.; Zandsalimi, Y.; Mahvi, A.H. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of natural organic matter degradation by UV/H2O2 advanced oxidation process. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Behera, B.; Babu, D.S.; Scaria, J.; Kumar, M.S. Mixed industrial wastewater treatment by the combination of heterogeneous electro-Fenton and electrocoagulation processes. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J.; Lodh, B.K.; Sharma, R.; Mahata, N.; Shah, M.P.; Mandal, S.; Ghanta, S.; Bhunia, B. Advanced oxidation process for the treatment of industrial wastewater: A review on strategies, mechanisms, bottlenecks and prospects. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, G.; Travin, S. Reactions’ mechanisms and applications of hydrogen peroxide. Am. J. Phys. Chem. 2020, 9, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amr, S.S.A.; Aziz, H.A. New treatment of stabilized leachate by ozone/Fenton in the advanced oxidation process. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1693–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norzaee, S.; Taghavi, M.; Djahed, B.; Mostafapour, F.K. Degradation of Penicillin G by heat activated persulfate in aqueous solution. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 215, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ma, W.; Song, W.; Chen, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zang, L. Fenton degradation of organic pollutants in the presence of low-molecular-weight organic acids: Cooperative effect of quinone and visible light. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.K.; Dikshit, A.K. Atrazine and human health. Int. J. Ecosyst. 2011, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çokay, E. Effects of the heterogeneous photo-Fenton oxidation and sulfate radical-based oxidation on atrazine degradation. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 252, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaquén, T.B.; Cuello, N.I.; Alfano, O.M.; Eimer, G.A. Degradation of Atrazine over a heterogeneous photo-fenton process with iron modified MCM-41 materials. Catal. Today 2017, 296, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scoy, A.R.; Yue, M.; Deng, X.; Tjeerdema, R.S. Environmental fate and toxicology of methomyl. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 222, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-C.; Trinh, C.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Chang, C.-Y.; Chiang, S.-W.; Ji, D.-R.; Tseng, J.-Y.; Chang, C.-F.; Chen, Y.-H. UV-C irradiation enhanced ozonation for the treatment of hazardous insecticide methomyl. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2015, 49, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, J.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, R.; Li, J. Heterologous expression of mlrA gene originated from Novosphingobium sp. THN1 to degrade microcystin-RR and identify the first step involved in degradation pathway. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Guillermin, C.; Pereira, S.; Della-Vedova, C.; Hinton, T.; Garnier-Laplace, J. Genotoxic and reprotoxic effects of tritium and external gamma irradiation on aquatic animals. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 220, 67–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Silva, F.; Lemos, C.R.; Naico, A.A.; Fachi, M.M.; do Amaral, B.; de Paula, V.C.S.; Rampon, D.S.; Beraldi-Magalhães, F.; Prola, L.D.T.; Pontarolo, R. Study of isoniazid degradation by Fenton and photo-Fenton processes, by-products analysis and toxicity evaluation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 425, 113671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziembowicz, S.; Kida, M. Limitations and future directions of application of the Fenton-like process in micropollutants degradation in water and wastewater treatment: A critical review. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 134041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.; Teixeira, A.; Ruotolo, L.A.M. Critical review of Fenton and photo-Fenton wastewater treatment processes over the last two decades. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 13995–14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Symbols | Rank and Levels | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Encoded | −1.68 | −1 | 0 | 1 | +1.68 | |

| Volumetric flow rate (L/min) | X1 | 0.19 | 0.3 | 0.45 | 0.6 | 0.70 | |

| Fenton ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | X2 | 4.97 | 6 | 7.5 | 9 | 10.02 | |

| Treatment time (min) | X3 | 19.77 | 30 | 45 | 30 | 70.22 | |

| A: Volumetric Flow (L/min) | B: Treatment Time (min) | C: Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | C: Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | COD * Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | 30 | 6 | 39.6 | 61.6% |

| 0.3 | 30 | 6 | 38.4 | 62.8% |

| 0.6 | 30 | 6 | 34.4 | 66.7% |

| 0.6 | 30 | 6 | 32.9 | 68.1% |

| 0.3 | 60 | 6 | 32.0 | 69.0% |

| 0.3 | 60 | 6 | 33.4 | 67.6% |

| 0.6 | 60 | 6 | 35.8 | 65.3% |

| 0.6 | 60 | 6 | 35.2 | 65.9% |

| 0.3 | 30 | 9 | 23.1 | 77.6% |

| 0.3 | 30 | 9 | 21.1 | 79.6% |

| 0.6 | 30 | 9 | 29.1 | 71.8% |

| 0.6 | 30 | 9 | 31.1 | 69.9% |

| 0.3 | 60 | 9 | 20.0 | 80.6% |

| 0.3 | 60 | 9 | 22.2 | 78.5% |

| 0.6 | 60 | 9 | 12.9 | 87.5% |

| 0.6 | 60 | 9 | 11.5 | 88.9% |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Squares | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 1066.83 | 7 | 152.4 | 123.78 | <0.0001 |

| A—Volumetric Flow | 2.89 | 1 | 2.89 | 2.35 | 0.164 |

| B—Treatment Time | 127.69 | 1 | 127.69 | 103.71 | <0.0001 |

| C—Fenton Ratio | 720.92 | 1 | 720.92 | 585.52 | <0.0001 |

| AB | 18.06 | 1 | 18.06 | 14.67 | 0.005 |

| AC | 0.64 | 1 | 0.64 | 0.5198 | 0.4915 |

| BC | 49 | 1 | 49 | 39.8 | 0.0002 |

| ABC | 147.62 | 1 | 147.62 | 119.9 | <0.0001 |

| Error | 9.85 | 8 | 1.23 | ||

| Total | 1076.68 | 15 |

| A: Volumetric Flow Rate (mg/L) | B: Treatment Time (min) | C: Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | COD | COD Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.45 | 45 | 7.5 | 31.0 | 70.0% |

| 0.45 | 45 | 7.5 | 29.7 | 71.2% |

| 0.45 | 45 | 7.5 | 28.4 | 72.5% |

| 0.45 | 45 | 7.5 | 27.0 | 73.8% |

| 0.45 | 45 | 7.5 | 25.8 | 75.0% |

| A: Volumetric Flow (mg/L) | B: Treatment Time (min) | C: Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | A: Volumetric Flow (mg/L) | B: Treatment Time (min) | C: Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | COD Removal (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | Ai | Bi | Ci | ||

| Center | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.45 | 45 | 7.5 | 70.5% |

| Stride length | 0.042 | 0.633 | 1 | 0.006 | 9.497 | 2 | |

| Step 1 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.45 | 51.3 | 9.0 | 86.3% |

| Step 2 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 2 | 0.46 | 57.7 | 10.5 | 87.7% |

| Step 3 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 3 | 0.463 | 64.0 | 12.0 | 93.6% |

| Step 4 | 0.87 | 1.69 | 4 | 0.467 | 70.3 | 13.5 | 94.2% |

| Step 5 | 1.27 | 1.35 | 5 | 0.471 | 76.7 | 15.0 | 92.2% |

| Step 6 | 1.29 | 2.96 | 6 | 0.48 | 83.0 | 16.5 | 91.1% |

| A: Volumetric Flow (L/min) | B: Treatment Time (min) | C: Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | COD | Removal of COD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.46 | 64.0 | 12.0 | 6.6 | 93.60% |

| 0.47 | 64.0 | 12.0 | 6.3 | 93.85% |

| 0.46 | 76.7 | 12.0 | 7.5 | 92.75% |

| 0.47 | 76.7 | 12.0 | 7.7 | 92.50% |

| 0.46 | 64.0 | 15.0 | 8.3 | 92.00% |

| 0.47 | 64.0 | 15.0 | 8.5 | 91.75% |

| 0.46 | 76.7 | 15.0 | 9.1 | 91.20% |

| 0.47 | 76.7 | 15.0 | 9.3 | 91.00% |

| 0.45659 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 7.2 | 93.00% |

| 0.47341 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 7.0 | 93.25% |

| 0.47 | 59.67 | 13.5 | 8.8 | 91.50% |

| 0.47 | 81.03 | 13.5 | 9.5 | 90.80% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 10.98 | 5.7 | 94.50% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 16.02 | 9.5 | 90.75% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 5.9 | 94.25% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 5.9 | 94.30% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 5.9 | 94.30% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 6.0 | 94.20% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 6.0 | 94.20% |

| 0.47 | 70.4 | 13.5 | 6.0 | 94.20% |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Squares | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 34.06 | 9 | 3.78 | 58.58 | <0.0001 |

| A—Volumetric Flow | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.9755 |

| B—Treatment Time | 1.78 | 1 | 1.78 | 27.52 | 0.0004 |

| C—Fenton Ratio | 12.48 | 1 | 12.48 | 193.22 | <0.0001 |

| AB | 0.0253 | 1 | 0.0253 | 0.3918 | 0.5454 |

| AC | 0.0253 | 1 | 0.0253 | 0.3918 | 0.5454 |

| BC | 0.0528 | 1 | 0.0528 | 0.8175 | 0.3872 |

| A2 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.9 | 29.45 | 0.0003 |

| B2 | 16.24 | 1 | 16.24 | 251.41 | <0.0001 |

| C2 | 4.2 | 1 | 4.2 | 65.08 | <0.0001 |

| Residual | 0.646 | 10 | 0.0646 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 0.634 | 5 | 0.1268 | 52.47 | 0.0003 |

| Pure Error | 0.0121 | 5 | 0.0024 | ||

| Total Cor | 34.7 | 19 |

| Standard Deviation | Mean | Coefficient of Variation (%) | R2 | R2 Adjusted | R2 Predicted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2542 | 92.90 | 0.2736 | 0.9814 | 0.9646 | 0.8591 |

| Variable | Indicator | Range or Condition | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | Independent Volumetric Flow Rate (L/min) | 0.46–0.47 | 0.466196 |

| Fenton Ratio (mg/L/mg/L) | 12–15 | 12.7132 | |

| Treatment Time (min) | 64.0–76.7 | 71.0319 | |

| Dependent | Percentage COD Removal (%) | Maximize | 94.5185% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pilco-Nuñez, A.; Rios-Varillas de Oscanoa, C.; Cueva-Soto, C.; Virú-Vásquez, P.; Milla-Figueroa, A.; Matamoros de la Cruz, J.; Vigo-Roldán, A.; Baca-Neglia, M.; Bravo-Toledo, L.; Cuellar-Condori, N.; et al. Response Surface Methodology in the Photo-Fenton Process for COD Reduction in an Atrazine/Methomyl Mixture. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020882

Pilco-Nuñez A, Rios-Varillas de Oscanoa C, Cueva-Soto C, Virú-Vásquez P, Milla-Figueroa A, Matamoros de la Cruz J, Vigo-Roldán A, Baca-Neglia M, Bravo-Toledo L, Cuellar-Condori N, et al. Response Surface Methodology in the Photo-Fenton Process for COD Reduction in an Atrazine/Methomyl Mixture. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):882. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020882

Chicago/Turabian StylePilco-Nuñez, Alex, Cecilia Rios-Varillas de Oscanoa, Cristian Cueva-Soto, Paul Virú-Vásquez, Américo Milla-Figueroa, Jorge Matamoros de la Cruz, Abner Vigo-Roldán, Máximo Baca-Neglia, Luigi Bravo-Toledo, Nestor Cuellar-Condori, and et al. 2026. "Response Surface Methodology in the Photo-Fenton Process for COD Reduction in an Atrazine/Methomyl Mixture" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020882

APA StylePilco-Nuñez, A., Rios-Varillas de Oscanoa, C., Cueva-Soto, C., Virú-Vásquez, P., Milla-Figueroa, A., Matamoros de la Cruz, J., Vigo-Roldán, A., Baca-Neglia, M., Bravo-Toledo, L., Cuellar-Condori, N., & Oscanoa-Gamarra, L. (2026). Response Surface Methodology in the Photo-Fenton Process for COD Reduction in an Atrazine/Methomyl Mixture. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 882. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020882