1. Introduction

The image data acquired through high-resolution remote sensing imaging technology contains detailed spatial information that is vital for numerous applications, such as urban planning [

1], disaster assessment [

2], intelligent traffic systems [

3], and land use monitoring [

4]. The precise segmentation of these images is therefore a task of significant practical importance. Historically, segmentation has relied on conventional techniques, including region growing [

5], thresholding [

6], and methods based on handcrafted features [

7]. These approaches, however, often demand considerable manual effort for parameter tuning and feature design. More critically, their underlying feature extraction mechanisms frequently exacerbate intra-class heterogeneity while weakening inter-class separability within the image data, ultimately leading to suboptimal segmentation accuracy.

The methodological evolution in the remote sensing image analysis field has been increasingly dominated by deep learning techniques over recent years, most notably through the widespread adoption and success of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The pioneering work of AlexNet [

8] marked a significant shift towards deep learning in image-related tasks, subsequently inspiring a substantial body of research applying advanced networks to various remote sensing challenges, including object detection [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], semantic segmentation [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], and environmental monitoring [

19]. While traditional CNNs were limited in handling spatial context, fully convolutional networks (FCNs) [

20] overcame this by enabling pixel-wise prediction and preserving spatial information. However, a key limitation of FCNs is their tendency to lose detailed information during upsampling, as they do not explicitly model pixel-level relationships, often resulting in imprecise object boundaries. To address these issues, several enhanced architectures derived from the FCN framework have been proposed, such as UNet [

21], DeepLabV3+ [

22], and SegNet [

23]. These models are designed to mitigate the problem of weakly correlated features across different network depths and positions, as well as the difficulty in fusing multi-level feature maps directly. Among them, UNet has established itself as a fundamental architecture for image segmentation. Its design leverages skip connections to integrate high-resolution features from the encoder path with the upsampled output from the decoder path. This mechanism effectively preserves fine-grained spatial details alongside high-level semantic information during the reconstruction phase. Drawing inspiration from UNet’s symmetrical design, SegNet [

23] also employs an encoder–decoder structure. In its encoder, pooling operations progressively reduce feature map resolution, while the corresponding decoder utilizes memorized pooling indices from the encoder to perform deconvolution operations, thereby recovering spatial details and original dimensions. The superior segmentation capability of UNet has motivated considerable further research, yielding numerous high-performing network variants. For instance, MF-UNet [

24] introduces an innovative multi-scale feature extraction block. This module aggregates shallow features at various scales, and by substituting the original skip connections, it alleviates the semantic gap, particularly evident in building segmentation tasks. In another advancement, Dense-UNet [

25] incorporates a median-frequency-balanced focal loss function to enhance segmentation accuracy for underrepresented or small object categories. Nonetheless, these advanced methods still exhibit certain shortcomings. A primary limitation lies in their insufficient capacity to model and incorporate global contextual relationships among all pixels, which can lead to the loss of important long-range information. Additionally, they often fail to fully exploit the contextual dependencies between different semantic categories. This inadequacy frequently causes misclassification in the segmentation outputs, blurring inter-class distinctions and reducing overall separability.

Segmenting large-scale targets in high-resolution remote sensing imagery presents significant challenges, primarily due to scene complexity, varying illumination conditions, and diverse imaging perspectives. These difficulties stem mainly from two inherent issues: (1) High intra-class heterogeneity: The substantial variability in the visual characteristics of objects, when observed across different temporal periods and geographical locations, poses significant challenges for consistent analysis. Urban building types, such as residential blocks and commercial complexes, possess distinct spectral characteristics influenced by architectural design and materials. Similarly, cultivated land in mountainous and plains has various properties, despite being classified under the same land use category. (2) Low inter-class separability: Different object categories frequently exhibit overlapping or similar feature representations, which can induce misclassification during the segmentation process. For instance, in urban settings, roads are prone to being confused with building shadows due to their spectral and textural resemblance. Likewise, residential gardens or courtyards are often misidentified as buildings. These elements collectively make it challenging to accurately judge the category of pixels along object boundaries, resulting in blurred edges and segmentation inaccuracies. Conventional convolutional stacking methods struggle to capture precise semantic information at object boundaries, thereby failing to achieve accurate target delineation.

To address these issues, the attention mechanism [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30] has emerged as a key strategy, leading to the development of a variety of advanced image segmentation models that extend the powerful UNet framework. Attention UNet [

31], for instance, incorporates an attention gate to focus adaptively on target structures of varying shapes and sizes. It selectively suppresses irrelevant areas in the input image and preserves and enhances features that are critical to the given task. Subsequent models like [

32,

33] employ multi-scale and multi-branch attention modules, respectively, to better unify semantic features and capture contextual dependencies. To mitigate information loss in skip connections, [

34] introduces a spatial-channel attention gate, while [

35] enhances skip connections by combining a linear attention mechanism with residual connections. Further refinements include the modified attention gate proposed by [

36], which relocates the resampler with a sigmoid function to bridge multi-level features, culminating in the attention gate UNet architecture. For high-resolution remote sensing imagery, the holistic nested attentional UNet [

37] integrates attention with multi-scale nested modules to significantly improve the extraction of fine edge details.

Nevertheless, current attention-based models designed for segmentation in remote sensing imagery continue to face difficulties in retaining fine structural details and producing segmentation results with crisp boundaries. This limitation becomes particularly pronounced in complex scenes containing various interfering elements, such as tree shadows and parking areas, which often lead to insufficient extraction of accurate features and consequently cause numerous segmentation errors. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel hybrid multi-attention architecture and introduces HMA-UNet, an attention-enhanced network specifically optimized for high-resolution remote sensing image segmentation. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

(1) We construct a feature extractor named lightweight channel spatial attention (LCSA). It utilizes attention mechanisms to capture channel-level features from the input feature map in the channel dimension and spatial-level feature information in the spatial dimension, respectively. The LCSA module integrates channel-wise and spatial-wise attention in a coordinated manner, applying each mechanism independently to the feature maps. This design effectively combines the complementary strengths of the two attention forms, significantly enhancing the network’s ability to screen and prioritize informative features. Consequently, it achieves a more precise and comprehensive feature representation.

(2) Building on the concept of adaptive feature refinement through attention, this paper proposes a multi-scale feature fusion module named lightweight split and fuse attention (LSFA). The LSFA module first divides the input features into two branches with varied receptive fields, then selectively recalibrates and aggregates them. This enables the network to dynamically adjust the emphasis on different spatial scales and contextual cues per channel. As a result, the module yields a more flexible and discriminative feature representation, which improves the model’s ability to recognize objects across diverse scales.

(3) We propose HMA-UNet, which incorporates a reinforced backbone network to address the semantic spatial gap between lower-level and higher-level feature representations in the standard UNet architecture. Specifically, we redesign the backbone by embedding the LSFA module in residual form at shallow stages to enhance multi-scale feature aggregation, and integrating the LCSA module at deeper stages to refine channel-wise and spatial feature responses. This structured enhancement enables the network to progressively emphasize foreground relevant information while suppressing background interference, ultimately leading to improved segmentation accuracy.

The following presents a roadmap of this paper:

Section 2 offers a comprehensive overview of the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules, describing their architectural design and core principles. We then present HMA-UNet, a hybrid multi-attention segmentation network that integrates the LCSA and LSFA modules, specifically developed for segmentation in remote sensing imagery.

Section 3 elaborates on the experimental configuration, encompassing descriptions of the benchmark datasets (i.e., the WHDLD Dataset [

38] and the DeepGlobe Dataset [

39]), the implementation environment, and the evaluation indicators.

Section 4 is dedicated to the experimental findings, where we discuss the performance of HMA-UNet in various segmentation scenarios. Finally, the study culminates in

Section 5 with a summary of the principal outcomes and insights obtained from the comprehensive experiments.

2. Methodology

To achieve precise target segmentation and effective background suppression in remote sensing imagery, this paper employs the attention mechanism as a core strategy. The mechanism facilitates dynamic feature recalibration by guiding the model to emphasize regions of interest while attenuating irrelevant background content, thereby enhancing the discriminative power of target representations. To mitigate persistent issues such as segmentation ambiguity, inadequate target feature extraction, and frequent false positives in complex scenarios, we propose the LCSA and LSFA modules, which are specifically engineered to address the heterogeneous and variable characteristics inherent to remote sensing images.

2.1. LCSA Module

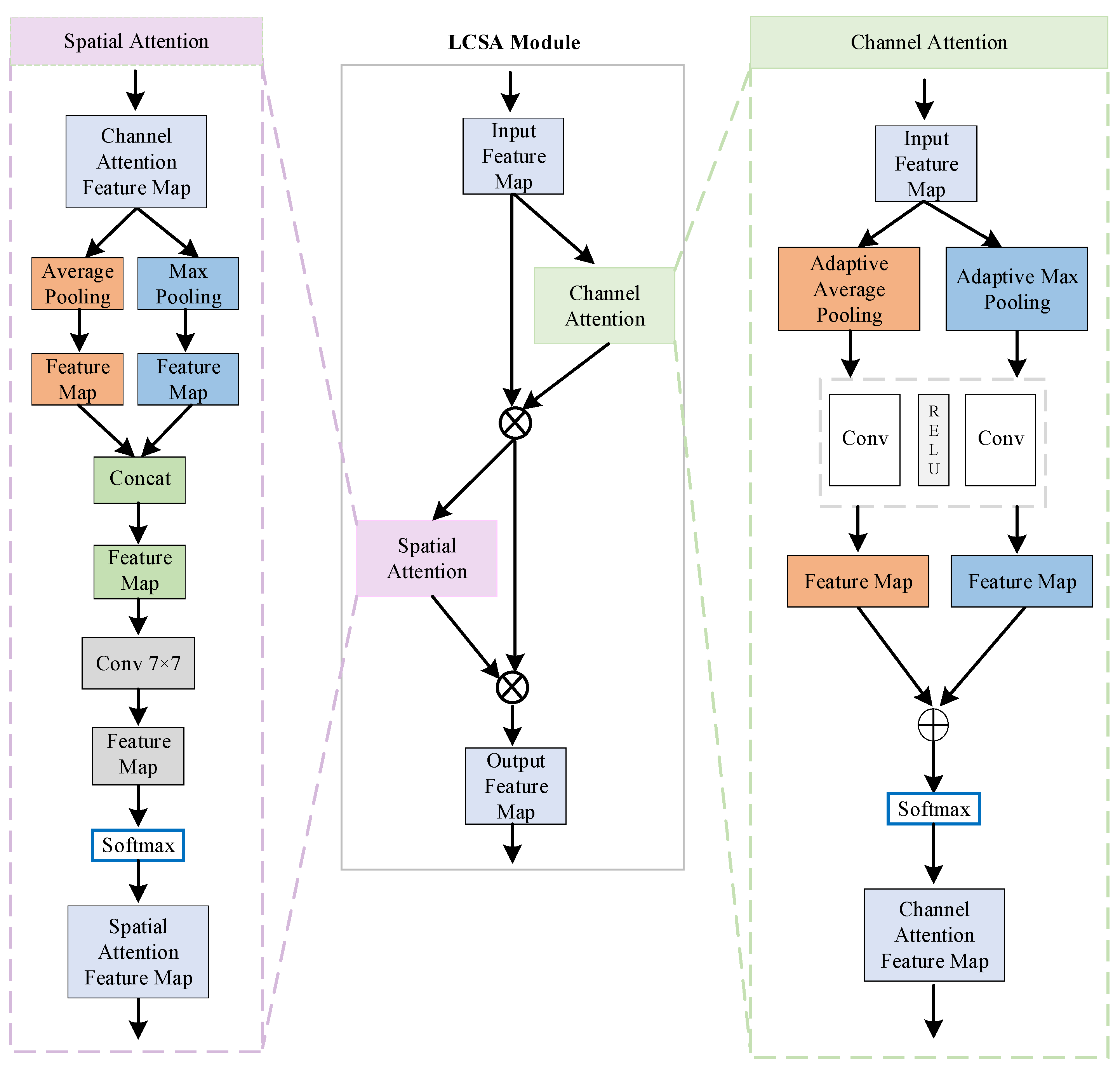

The LCSA module integrates two sequentially connected attention units, a channel attention unit and a spatial attention unit. The channel attention mechanism employs adaptive max pooling and adaptive average pooling followed by a convolution operator and activation function to generate a channel-wise weighting vector, thereby highlighting the most informative feature channels. Subsequently, the spatial attention unit utilizes channel-reduced global features, going through another similar processing link, to produce a spatial weighting map that enhances salient regions across all feature layers. The detailed architecture of the LCSA module is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The channel attention unit initiates processing by transforming the input feature tensor with dimension into a compact representation through global average pooling applied across spatial dimensions. This operation aggregates spatial information from all channels, yielding a channel-wise descriptor of size . The descriptor is subsequently refined by a convolution operation that reduces its dimensionality. A Sigmoid activation function is subsequently applied to the convolution output for producing the channel-level weights, a vector of size where each element indicates the importance of the corresponding channel for feature representation. Feature refinement is achieved by performing element-wise multiplication between the above weights and the original feature tensor, thereby generating a refined feature map, which serves as the input to the subsequent spatial attention stage.

We then apply a global max pooling operation on the input feature tensor along the channel dimension to obtain an output feature with a size of and select the maximum activation at each spatial location . The resulting single-channel feature map undergoes a convolution operation using a kernel with a stride of 1, which is subsequently normalized by a Sigmoid function, yielding the spatial attention stage weight with a size of . This weight map encodes the relative importance of each spatial position. Finally, the output feature map is obtained by performing an element-wise multiplication between the spatial attention weight map and the input feature map, thereby emphasizing informative regions while suppressing less relevant areas.

The orange and blue pathways in

Figure 1 show two different attention processing patterns in the LCSA module. While both pathways share an identical architectural framework, they differ fundamentally in their feature aggregation strategies. Within the orange pathway, the channel attention sub-module employs global max pooling to generate channel-wise statistics, capturing the most salient feature response per channel, as opposed to the global average pooling utilized in the blue pathway. Conversely, for spatial attention, the orange pathway adopts global average pooling across channels to compile a spatial weight map, contrasting with the global max pooling operation applied in the blue pathway. Ultimately, the feature maps output by these two branches are aggregated via element-wise summation to produce the final output of the LCSA module.

The LCSA module’s design incorporates dual considerations. First, to mitigate errors inherent in feature extraction, primarily stemming from increased estimation variance due to limited receptive fields and bias in the estimated mean values arising from parameter inaccuracies in convolutional layers. Average pooling is utilized to suppress the variance of intra-group and retain features of interest. Max pooling, on the other hand, serves to amplify inter-group variance and retain richer texture details. These two parallel branches enable the aggregation of multi-perspective features from different pooling operations, thereby capturing more comprehensive channel-wise and spatial detail information to enhance segmentation accuracy. Second, the module sequentially emphasizes both critical channels and significant spatial locations in the feature maps. It first evaluates and recalibrates channel importance through channel attention, followed by spatial matrix operations that refine spatial information. This sequential enhancement prioritizes channel information before modulating spatial relationships, which improves the extraction and utilization of target information effectively. Consequently, it preserves better edge details and strengthens the network’s overall discriminative capability.

2.2. LSFA Module

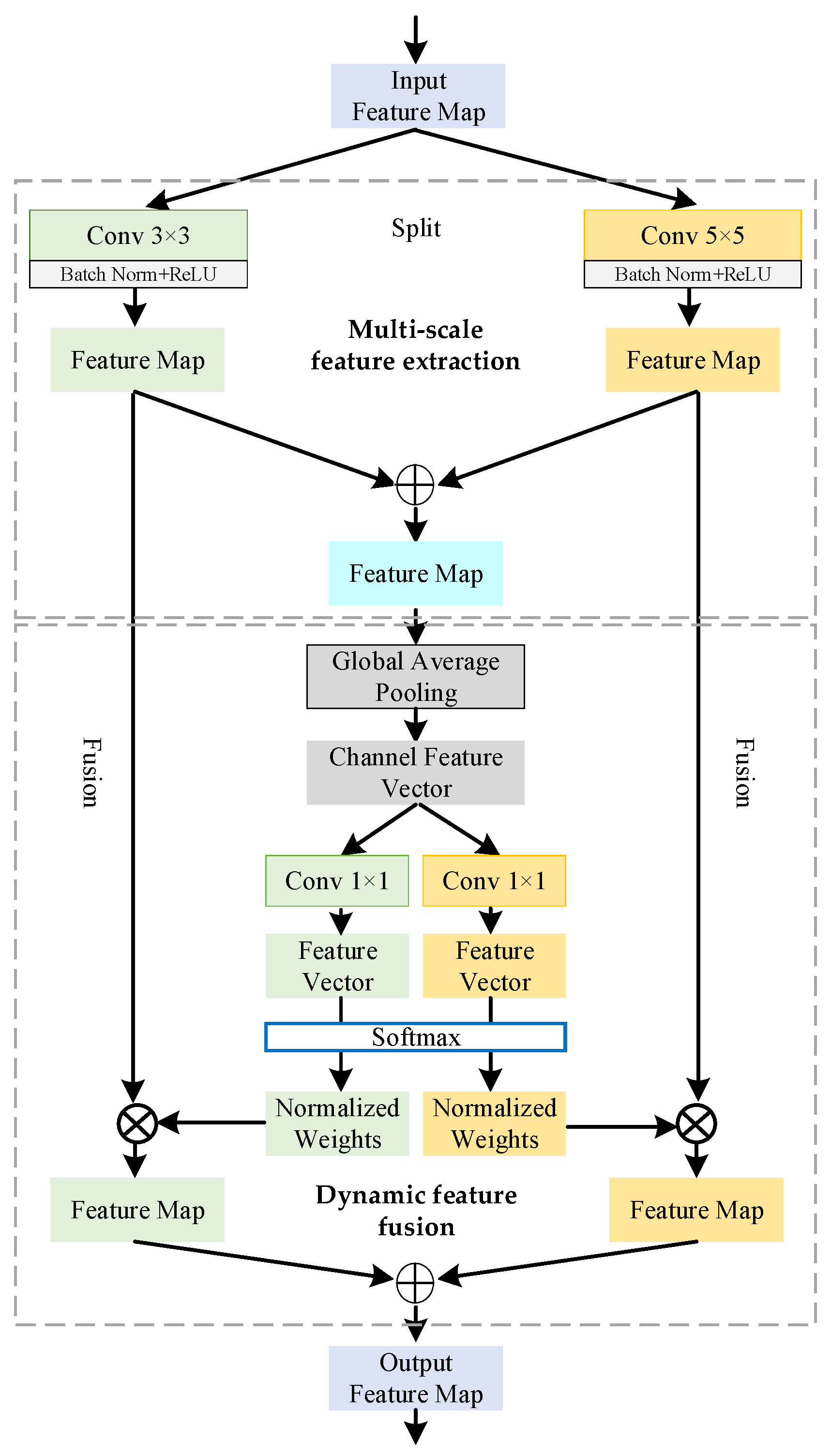

The detailed architecture of the LSFA module is illustrated in

Figure 2. The LSFA module operates through two sequential stages: multi-scale feature extraction and dynamic feature fusion. In the first stage, the input features are processed in parallel by two distinct convolutional branches to capture complementary contextual information. One branch employs a

convolutional kernel, while the other utilizes a

kernel. The resulting feature maps from both branches are then concatenated along the channel dimension, forming an integrated multi-scale feature representation.

The subsequent stage is designed to adaptively recalibrate and integrate the contributions from these multi-scale features. Initially, the feature maps from all branches are element-wise summed. Global average pooling is then applied to compress the spatial information into a channel-wise descriptor. This compact descriptor is processed by two parallel convolutional layers, which generate a set of adaptive weighting coefficients corresponding to each scale. Finally, the original multi-scale features are aggregated via a weighted summation based on these learned coefficients, followed by a SoftMax normalization to ensure a probabilistic weighting distribution. This mechanism enables the network to dynamically emphasize the most informative feature scales, thereby refining the final feature representation for enhanced discriminative capability.

2.3. HMA-UNet Structure

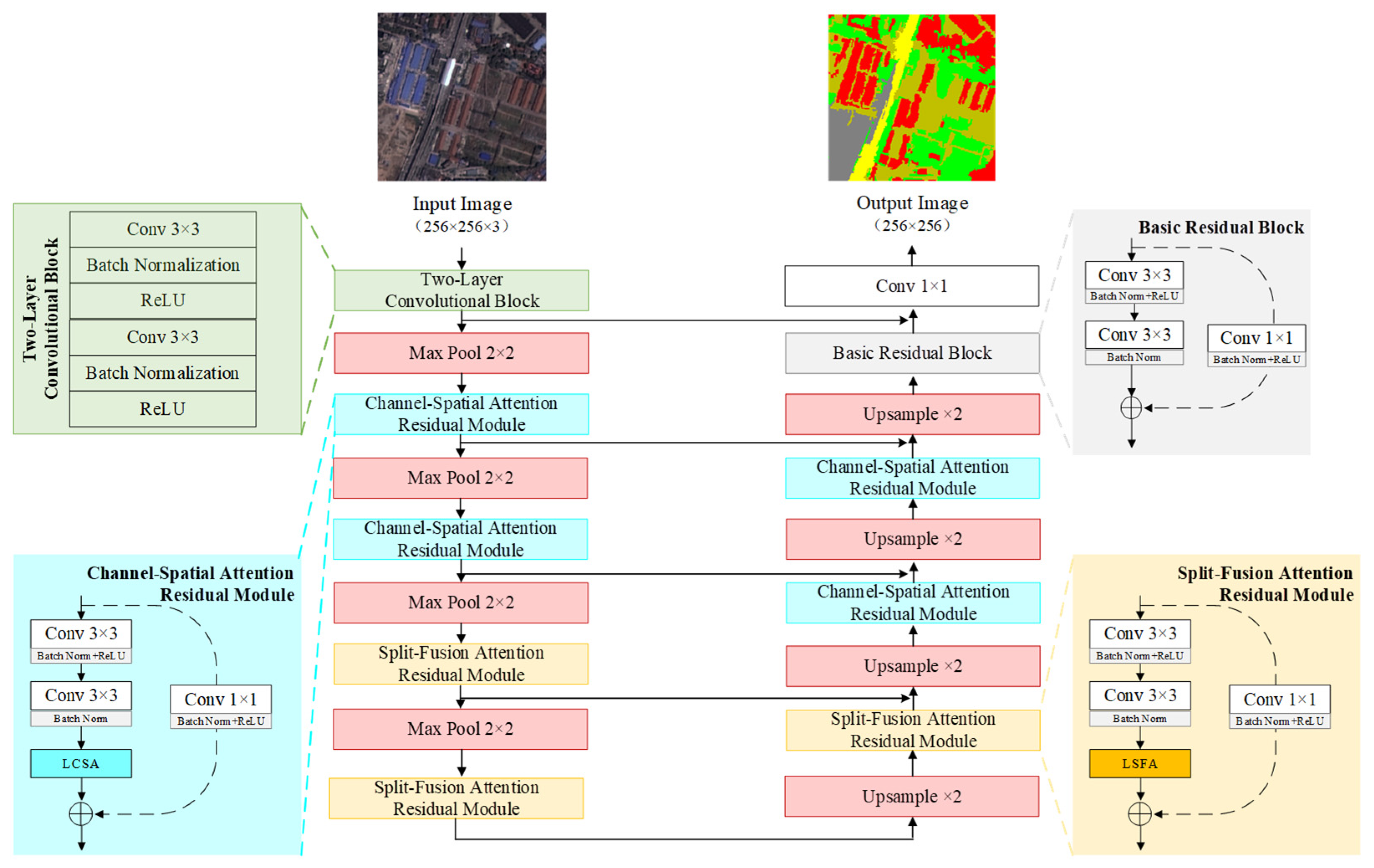

A key strength of the UNet architecture lies in its use of skip connections between the convolutional encoder–decoder architecture, which helps mitigate the loss of fine-grained detail during downsampling and feature propagation. However, conventional skip connections treat all incoming shallow features equally, without distinguishing between semantically relevant information and potentially disruptive elements. This undifferentiated fusion can limit segmentation precision and introduce artifacts in the final output. Inspired by the human visual system, which selectively attends to salient stimuli while suppressing irrelevant context, attention mechanisms provide an effective means to enhance feature selectivity. By dynamically weighting feature contributions, such mechanisms improve the efficiency of information extraction and focus computational resources on task-relevant regions. To address the limitations of standard skip connections, this study introduces learned attention weighting into the feature aggregation pathway. Specifically, the stacked convolutional layers conventionally used in the backbone of UNet are replaced with the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules. These modules adaptively assign importance weights to different components of the shallow feature maps, thereby conveying the features most relevant to the target segmentation task through skip connections. This refinement enables the network to concentrate on semantically meaningful patterns, leading to improved segmentation quality and robustness against irrelevant interference.

HMA-UNet is an end-to-end deep convolutional neural network built upon the U-Net architecture. The model comprises two primary sub-networks: a downsampling encoder for hierarchical feature extraction from input RGB images, and a corresponding upsampling decoder dedicated to progressively reconstructing the feature maps and restoring spatial resolution. The final output is a segmentation map that matches the resolution of the initial input image. The proposed LCSA and LSFA attention modules are integrated into both sub-networks via residual connections. For the LCSA mechanism, a channel-spatial attention residual module is implemented (indicated in the blue block within the architecture diagram). Correspondingly, the LSFA mechanism is realized through a split-fusion attention residual module (represented by the yellow block). Skip connections are established between corresponding layers of the encoder and decoder to preserve fine-grained spatial information. A final convolutional layer with a

kernel is applied at the network output to generate the pixel-wise segmentation result. The complete architecture of HMA-UNet is illustrated in

Figure 3.

In the encoder stage, the encoder accepts RGB remote sensing images with dimensions of as input. Initially, each image is processed by a two-layer convolutional block (represented by the green block), which incorporates two consecutive convolutional layers with a stride of 1, each followed by batch normalization and a ReLU activation function. The resulting feature map is then processed along two paths. One path applies a max pooling operation, halving the spatial dimensions, while the other forwards the feature map directly to the corresponding decoder layer via a skip connection. Subsequently, the pooled features are passed sequentially through the LCSA and LSFA residual blocks, with their outputs also being routed to the corresponding upsampling stage in the decoder. This sequence of convolution and pooling is repeated four times throughout the encoder. As a result, the number of feature channels progressively expands from an initial count of 3 to 512, while the spatial resolution is reduced to one-sixteenth of that of the initial input. Within the network architecture, at its innermost stage, the channel count is further increased to 1024, enabling the capture of higher-level semantic features essential for effective model training and yielding more precise segmentation outcomes.

In the decoder stage of HMA-UNet, the 512-channel feature maps are first upsampled using a filter, which reduces the channel dimension to 256 while doubling the spatial size. This step ensures dimensional alignment with the corresponding encoder layer. The upsampled features are then concatenated with the output from the LSFA residual module in the encoder via skip connection. The concatenated result is subsequently processed by the LCSA residual module within the decoder. Following this, the output undergoes another upsampling operation, further reducing the channels to 128 and again doubling the spatial resolution. This sequence of upsampling and attention-based skip connection fusion is repeated four times throughout the decoder. As a result, the feature maps are progressively restored to the original input spatial dimensions of , while the channel count is gradually reduced to 32. Finally, the features are passed through a 1 × 1 convolutional layer, which produces an output with a channel number equal to the total segmentation categories.

The HMA-UNet employs a weighted combination of Dice loss and cross-entropy loss to train the network, as shown in Equation (1), where

is set to 0.6.

The Dice loss function is an important loss function in the field of image segmentation, as it directly optimizes the objective related to evaluation metrics, thereby alleviating class imbalance issues. In this paper, the multi-class Dice loss function is expressed as Equation (2).

where

denotes the number of classes,

represents the total number of pixels,

denotes the predicted probability that pixel

belongs to class

, and

indicates whether the true label of pixel

is category

. If true, the value is 1; otherwise, it is 0.

is a smoothing term introduced to reduce overfitting, thereby stabilizing the training process.

where

denotes the total number of pixels in the image,

is the number of classes,

is an indicator function that equals 1 if the ground-truth class of pixel

is

, and 0 otherwise.

represents the probability predicted by the model that pixel

belongs to class

. We combine Dice loss with cross-entropy loss to form a composite loss function, leveraging the strengths of both to achieve a more robust and accurate segmentation model.

4. Results and Analysis

This section presents the experimental results. The evaluation is designed to assess the performance of the proposed HMA-UNet and its core LCSA and LSFA modules through three primary analyses: (1) a comparative experiment pitting HMA-UNet against several typical segmentation models, including UNet [

21], SegNet [

23], HRNet [

40], ViT [

41], DeepLabv3+ [

22], U-Net++ [

42]; (2) an ablation study examining the contribution of the LCSA and LSFA modules by comparing them with alternative attention mechanisms; (3) the inference speed analysis of the above models; (4) and a comparison with the transformer based geospatial vision foundation model CrossEarth [

43].

4.1. WHDLD Dataset

4.1.1. Comparative Benchmark Experiment

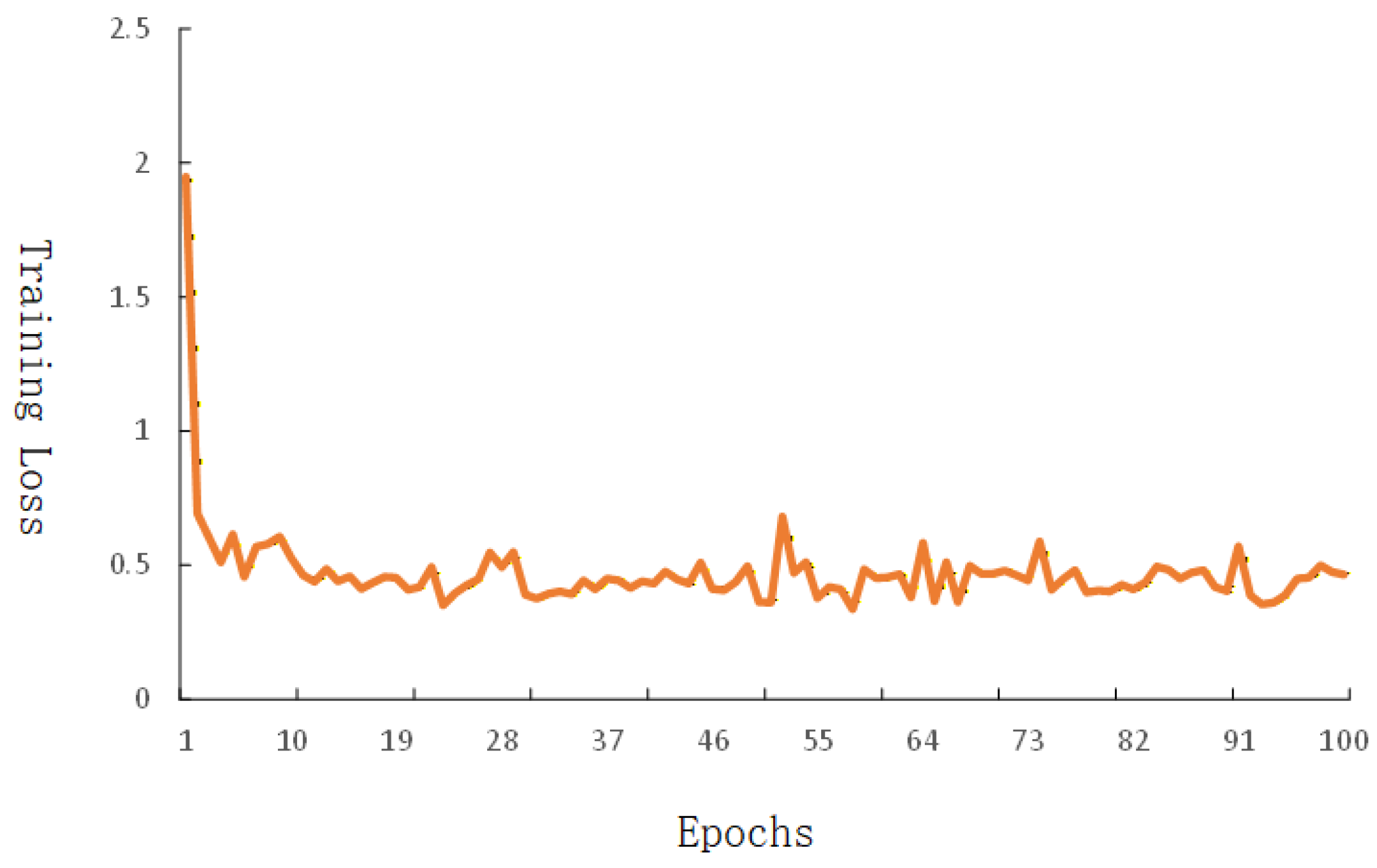

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed HMA-UNet, comprehensive comparative experiments were performed on the WHDLD dataset. Six state-of-the-art deep learning models, UNet, SegNet, HRNet, ViT, Deeplabv3+ and U-Net++ were implemented under identical experimental conditions for a fair comparison. All networks, including HMA-UNet, were initialized randomly without any transfer learning. All architectures demonstrated stable convergence during optimization. The quantitative results, including mean accuracy, mIoU, mPrecision, and mRecall, are summarized in

Table 1, while qualitative visual comparisons are provided in

Figure 5. The experimental outcomes demonstrate that HMA-UNet achieves superior performance across the evaluated metrics compared to the existing benchmark models.

As shown in

Table 1, the proposed HMA-UNet outperforms all benchmark methods across all evaluated metrics. Specifically, HMA-UNet achieves an mAccuracy of 72.40%, an mIoU of 60.71%, an mPrecision of 75.46%, and an mRecall of 72.41% on the WHDLD dataset. This superior performance validates the effectiveness of the enhanced architecture in refining feature screening and integration. The original feature information from the encoder, delivered via skip connections, is retained and simultaneously supplemented by multi-dimensional features that are further harnessed from the shallow layers. This design enhances the delineation of edge details in segmentation tasks and reduces both false positives and missed detections for large objects commonly found in remote sensing imagery. In comparison, methods such as HRNet (which employs repeated cross-parallel convolutions for multi-scale fusion) and SegNet (which utilizes pooling indices) yield notably lower scores across all four metrics. The performance gap is particularly evident when compared to the baseline U-Net, which trails HMA-UNet by margins of 23.09% in mAccuracy, 26.00% in mIoU, 13.69% in mPrecision, and 23.09% in mRecall. The outcomes presented above validate the effectiveness of the proposed structural enhancements. These improvements are built on the foundational UNet architecture. Consequently, they significantly boost both the accuracy and robustness of segmentation in remote sensing image analysis.

Figure 5 provides a visual comparison of prediction results across different methods, with a focus on several representative scenarios: uniform water and vegetation, diverse urban morphologies, including areas with dispersed and dense building layouts. This qualitative examination serves to illustrate its segmentation capability. The advantages are reflected in its capability to preserve edge contours of water, vegetation, buildings, and roads, while simultaneously reducing both misclassification and omission errors. The figure comprises five sets of prediction results, each arranged in eight columns with the original image presented in

Figure 5a.

Figure 5b–h subsequently showcase the prediction results obtained from the following methods: Ground Truth, SegNet, HRNet, ViT, Deeplabv3+, U-Net++, and HMA-UNet, respectively. Through comparative visual assessment, it can be observed that the proposed method achieves more accurate segmentation of buildings, roads, vegetation, bare soil, and water bodies, delivering detailed and precise predictions across diverse scenarios.

As shown in the red box of the first image in

Figure 5, the predictions from SegNet, Deeplabv3+, and U-Net++ manifest noticeable discontinuities and misclassification points. In the first image, although SegNet, HRNet, and Deeplabv3+ can recognize the existence of water, their segmentation results are not as complete as those of our proposed method. In the second image, due to the dense distribution of buildings, the predictions of SegNet, Deeplabv3+, and U-Net++ suffer from significant inaccuracies and visual ambiguity. In contrast, our proposed HMA-UNet, enhanced by the integration of LCSA and LSFA mechanisms, effectively mitigates background interference and emphasizes critical features. This leads to superior robustness, as evidenced in the third image containing extensive water bodies within vegetated areas. While HMA-UNet accurately delineates the vegetation, the other comparative models produce evident errors, as indicated within the pink annotations. Within the blue annotations of the fourth image, the segmentation results of SegNet and Deeplabv3+ misclassified some building areas as roads, whereas HMA-UNet performed well by accurately segmenting the buildings. Moreover, the HMA-UNet can accurately identify the small water area within the white box, while other methods cannot effectively identify the target.

In the fifth image, the proposed HMA-UNet can more accurately identify road targets enclosed in water areas, with clearer segmentation edges and smoother results, while the results of SegNet, HRNet, Deeplabv3+, and U-Net++ reveal obvious misclassification. Overall, the segmentation results produced by the proposed method demonstrate greater structural integrity and contour completeness. In contrast, HRNet and ViT exhibit noticeable misclassification errors, while the outcomes from SegNet, Deeplabv3+, and U-Net++ display incomplete segmentation of buildings, roads, and vegetation. The proposed DHAU-Net proves particularly effective in complex scenes, accurately delineating target objects while suppressing irrelevant interference, which underscores its comparative advantage over the other methods examined.

4.1.2. Ablation Experiment for the Attention Module

To further demonstrate the advantages of the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules, a comparative study is conducted with several widely used attention mechanisms, such as spatial attention (SA) [

44], Nonlocal [

30], bottleneck attention module (BAM), squeeze-and-excitation (SE), convolutional block attention module (CBAM), and selective kernel (SK), when integrated into the UNet architecture. This comparison aims to evaluate the contribution of different attention mechanisms to enhancing the network’s segmentation capability. All networks are trained from scratch under identical experimental conditions, with consistent hyperparameters and without employing any pre-trained models. As summarized in

Table 2, the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules achieve superior quantitative results compared to the existing attention mechanisms. For a direct visual appraisal, the predicted results from various methods are juxtaposed in

Figure 6.

Table 2 indicates that the SA and Nonlocal mechanisms are not well-suited for this segmentation task within the UNet framework, as evidenced by the suboptimal performance of the corresponding models on the evaluation metrics. In contrast, models incorporating the BAM, SE, and CBAM modules demonstrate comparable performance levels to one another, perform much better than the baseline UNet, UNet + SA, and UNet + Nonlocal model. Among them, the UNet + SK model achieves better results than the above three models. It outperforms the UNet + BAM, UNet + SE, and UNet + CBAM methods across all evaluated metrics. Specifically, the UNet + SK achieves an mAccuracy of 70.26%, an mIoU of 62.04%, an mPrecision of 74.26%, and an mRecall of 70.94% on the WHDLD dataset. Although the UNet + SK model shows better performance than others, it still performs slightly worse than our HMA-UNet, which trails HMA-UNet by margins of 2.96% in mAccuracy, 1.98% in mPrecision, and 2.03% in mRecall. The effectiveness of our LCSA and LSFA modules is further evidenced by the comparative experimental results, confirming their positive impact on this segmentation task.

Figure 6 presents five sets of prediction results, each arranged in ten columns.

Figure 6a displays the original image,

Figure 6b displays the ground truth, while

Figure 6c–j show the prediction results from the following architectures: UNet, UNet + SA, UNet + Nonlocal, UNet + BAM, UNet + SE, UNet + CBAM, UNet + SK, and HMA-UNet, respectively.

Figure 6 presents a visual comparison of segmentation results from the baseline UNet, the proposed HMA-UNet, and six attention-based variants (SA, Nonlocal, BAM, SE, CBAM, and SK). In the first image, UNet + BAM, UNet + CBAM, UNet + SK, and HMA-UNet achieve comparable accuracy in vegetation segmentation. However, HMA-UNet better preserves the structural continuity of vegetation areas. The integration of multi-attention mechanisms consistently endows all four models with significantly enhanced robustness against noise interference in such contexts. In the second image, which includes sparse bare soil and road interference, UNet + BAM, UNet + CBAM, and UNet + SK demonstrate superior accuracy, yet lack the capability to segment bare soil regions completely. The third image, featuring dense and uniformly distributed buildings, reveals notably poor segmentation performance by UNet, UNet + SA, and UNet + SE. Although other methods detect most of the building targets, their boundaries are often blurred, and bare soil between buildings is frequently misclassified as building area. For the fourth image with sparsely distributed buildings, the proposed HMA-UNet delivers clearly superior segmentation results. In contrast, UNet, UNet + SA, and UNet + BAM produce fragmented and less coherent building segments. On road segmentation in this scene, UNet + SK and HMA-UNet perform notably better than the other compared methods. In the fifth image, UNet + SE yields the weakest road segmentation (indicated in the pink box), whereas other models perform adequately in this aspect. Additionally, UNet, UNet + SA, and UNet + Nonlocal fail to identify the bare soil region highlighted in the white box.

Overall, the HMA-UNet achieves consistently accurate segmentation across varied scenarios, including sparse or dense target distributions, unclear boundaries, and low inter-class spectral contrast. Its ability to selectively enhance relevant features plays a crucial role in obtaining robust segmentation results, especially under complex environmental interference.

Upon evaluating the aforementioned attention mechanisms, the CBAM and SK modules demonstrate notable effectiveness in remote sensing image segmentation tasks, particularly in handling large intra-class scale variations, complex background interference, and subtle inter-class differences. These two modules outperform other candidates, such as SE, BAM, Non-local, and SA, in terms of both quantitative metrics and qualitative visual fidelity. Thus, we integrate the CBAM and SK modules into the same architectural framework as the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules, constructing a model denoted as UNet + CBAM + SK. The segmentation results of this model are subsequently compared with those of HMA-UNet to further validate the efficacy of the proposed modules. The quantitative results, including mean accuracy, mIoU, mPrecision, and mRecall, are summarized in

Table 3, while qualitative visual comparisons are provided in

Figure 7.

Table 3 shows that the proposed HMA-UNet (UNet + LCSA + LSFA) performs better than UNet + CBAM + SK on most of the metrics, including mACC, mPrecision, and mRecall, but slightly worse on the mIoU metric. Specifically, the UNet + CBAM + SK model achieves an mAccuracy of 71.60%, an mIoU of 63.17%, an mPrecision of 75.46%, and an mRecall of 71.60% on the WHDLD dataset, which trails HMA-UNet by margins of 1.10% in mAccuracy, 0.40% in mPrecision, and 1.12% in mRecall. The comparison results further confirm the effectiveness of the proposed HMA-UNet.

The comparative results in

Figure 7 are organized in seven groups of four rows each. From top to bottom, these rows correspond to

Figure 7a the input image,

Figure 7b the annotation mask,

Figure 7c the prediction of UNet + CBAM + SK, and

Figure 7d the prediction of HMA-UNet. It can be seen that in the pink box of the first image, the results of the UNet + CBAM + SK model show obvious breakpoints and discontinuities. In the second and third images, the road and bare soil extraction results of the HMA-UNet still perform better than the results of UNet + CBAM + SK, which are more continuous, smooth, and completely visible. In the pink box of the fourth image, the UNet + CBAM + SK model failed to identify small bodies of water, while the HMA-UNet model could identify them effectively. In the fifth and sixth images, the UNet + CBAM + SK model misclassifies some water and bare soil as vegetation and road, respectively, while the HMA-UNet performs better. In the seventh image, the HMA-UNet can recognize more accurate road pixels than the UNet + CBAM + SK model. In general, the segmentation results obtained with the LSFA + LCSA module (HMA-UNet) are usually more accurate, capturing more correct semantic information across categories. The predicted regions appear more complete, with better-defined boundaries and fewer instances of misclassification or fragmentation. These qualitative improvements further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

4.2. DeepGlobe Road Extraction Dataset

The transferability of HMA-UNet was assessed by training all models on the DeepGlobe Road Extraction Dataset. All models were kept identical in architecture, differing only in datasets. The corresponding quantitative results are provided in

Table 4, and representative visual comparisons are shown in

Figure 8.

The performance of the proposed HMA-UNet on the DeepGlobe Road Extraction Dataset is quantitatively compared with that of other methods across multiple metrics in

Table 4. HMA-UNet achieves an accuracy of 57.87%, an IoU of 49.82%, a precision of 78.18%, and a recall of 57.87%. Compared to the original UNet, HMA-UNet demonstrates substantial improvements across most metrics. Specifically, UNet yields an accuracy of 15.21%, an IoU of 14.86%, a precision of 86.42%, and a recall of 15.21%. This indicates that HMA-UNet surpasses UNet by significant margins of 73.72% in accuracy, 70.17% in IoU, and 73.72% in recall. It is noted that UNet attains the highest precision of 86.42%, which is 9.53% higher than that of HMA-UNet. Other methods with relatively low overall accuracy, such as UNet + SA, UNet + Non-local, and SegNet, also outperform HMA-UNet in terms of precision. This can be attributed to the inherent trade-off in binary classification tasks, where a lower precision for one class often corresponds to a higher precision for the opposing class. Overall, both the UNet + CBAM + SK model and the proposed HMA-UNet deliver superior comprehensive performance compared to the other methods. Furthermore, HMA-UNet slightly outperforms the UNet + CBAM + SK model across the evaluated metrics. The capability of attention mechanisms to provide quantifiable improvements in the segmentation task is verified by these results, with the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules exhibiting the most favorable performance improvement.

Figure 8 illustrates two test images (Image 1 and Image 2), each subdivided into a 2 × 7 grid comprising 14 sub-figures. Labels (a) through (n) correspond to the segmentation results of the original image, ground truth, UNet, UNet + SA, UNet + Nonlocal, UNet + BAM, UNet + SE, UNet + CBAM, UNet + SK, SegNet, Deeplabv3+, U-Net++, UNet + CBAM + SK, and HMA-UNet, respectively.

Image 1 reveals a common limitation across all compared methods, where their segmentation results exhibit pronounced artifacts due to the interference from buildings, vegetation, vehicles, and bare soil. Specifically, certain road sections are misclassified as background. While most networks accurately identify the road in the lower-left region, notable errors persist in segmenting low-contrast road segments, which are incorrectly assigned to the background. The segmentation performance of UNet + CBAM + SK and HMA-UNet is comparable. However, HMA-UNet exhibits fewer misclassifications in the upper-right area.

In Image 2, the road segmentation performance is evaluated under conditions of extensive and uniformly distributed building coverage. Most networks fail to completely segment roads adjacent to uniformly distributed buildings, resulting in high error rates. Although UNet + BAM and UNet + SE successfully segment a majority of the road areas, partial omissions remain. U-Net + SK and U-Net + CBAM + SK demonstrate overall superior segmentation performance, accurately extracting most road sections; however, they are less effective than HMA-UNet in preserving fine details. On the DeepGlobe Road Extraction Dataset, the incorporation of the LCSA and LSFA modules into the U-Net enhances detail retention. The proposed modules improve focus on foreground road features while suppressing background interference and reducing noise impact.

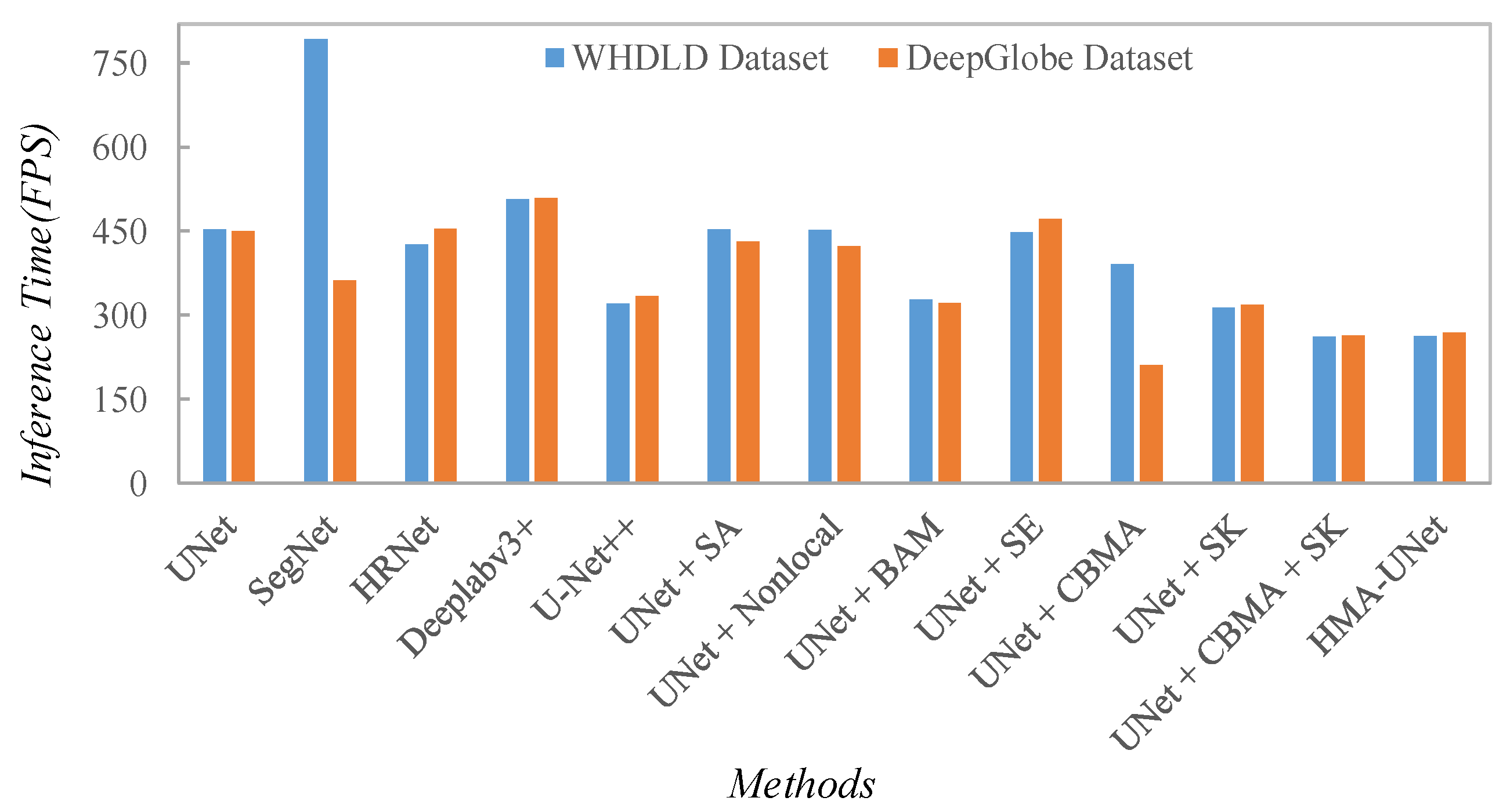

4.3. Inference Speed Discussion

Figure 9 compares the inference time of each model under identical conditions, using frames per second (FPS) as the metric. On the WHDLD and DeepGlobe datasets, HMA-UNet exhibits a 42.45% and 40.46% increase in inference time compared to the original UNet, respectively. Nevertheless, it maintains a processing speed of over 260 FPS, which satisfies the requirements for real-time application. Given the significant improvement in segmentation performance achieved by HMA-UNet on remote sensing imagery, this additional computational overhead is considered acceptable. Furthermore, compared to the UNet + CBAM + SK model, HMA-UNet shows a slight improvement in inference time while delivering superior performance on the mAccuracy, mPrecision, and mRecall metrics. Overall, HMA-UNet demonstrates robust segmentation capability for urban remote sensing images, with the gain in performance well justified within a reasonable increase in inference cost. The results confirm that the proposed LCSA and LSFA modules provide an effective and practical means of enhancing network segmentation performance.

4.4. Comparison with CrossEarth

The quantitative comparison between the proposed HMA-UNet and the geospatial vision foundation model, CrossEarth, is summarized in

Table 5. On the WHDLD dataset, HMA-UNet achieves superior performance in terms of both precision and recall. Specifically, it attains an IoU of 60.71% and a precision of 75.76%, marginally surpassing CrossEarth by 0.41% and 0.64%, respectively. On the DeepGlobe dataset, CrossEarth demonstrates superior segmentation accuracy, achieving an accuracy of 67.77%, an IoU of 78.85%, a precision of 82.25%, and a recall of 78.85%. In contrast, HMA-UNet attains an accuracy of 57.87%, IoU of 49.82%, precision of 78.18%, and recall of 57.87%. This performance gap can be attributed to the vastly greater model capacity of CrossEarth, which possesses 327.77 million parameters, enabling it to learn richer and more complex feature representations from large-scale pre-training.

However, this high accuracy comes at a significant computational cost. CrossEarth has a model size of approximately 1.25 GB and an inference speed of only 60–70 FPS on standard hardware. Such requirements hinder its deployment in resource-constrained scenarios, particularly for on-board satellite processing where power, memory, and computational budgets are strictly limited. In stark contrast, the proposed HMA-UNet exemplifies a lightweight design. With merely 15.43 million parameters, about one-twentieth of CrossEarth’s size and a compact model footprint of 58.87 MB, it achieves a remarkably high inference speed of 260–270 FPS. This efficiency makes it a compelling candidate for real-time or on-board Earth observation applications. Notably, on the WHDLD dataset, HMA-UNet achieves highly competitive performance relative to CrossEarth, HMA-UNet even slightly surpasses the foundation model in terms of IoU and precision, while matching it closely in accuracy and recall, despite its drastically smaller model size.

This comparison highlights a critical trade-off in remote sensing segmentation between pure accuracy and practical deployability. While large vision foundation models based on transformer structure, like CrossEarth, set the state-of-the-art in accuracy, their computational footprint is prohibitive for edge deployment. The proposed HMA-UNet offers a balanced alternative, delivering comparable and, on some datasets, superior precision with a fraction of the computational cost and model size. This design aligns with the growing trend towards lightweight, efficient algorithms for geospatial intelligence, proving that a carefully designed compact model can achieve a favorable balance between performance and practicality for specific operational contexts.