Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based and Colorimetric Technologies for Detecting Illicit Drugs and Environmental Toxins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Nanoparticles and Nanotube-Based Methods for Illicit Substance Detection: Array and Surface Functionalization

2.1. Methods for Gold Nanoparticle-Based Detection

2.2. Methods for Gold Nanorod-Based Detection

2.3. Methods for Carbon Nanotube-Based Detection

3. Nanosheet-Based Methods: Graphene and Borophene

4. MXene and MOF-Based Illicit Substances Detection

| Materials | Methods | Limit of Detection | Target Drugs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zr-MOF | fluorescence sensor | 1.15 nM | amphetamine | [51] |

| Zn(II)-MOF/SPCE | DPV | 0.3 µM | fentanyl | [55] |

| Cu-MOF/CPE | DPV | 0.02 µM | methocarbamol | [56] |

| MOF@MWCNTs/GCE | DPV | 0.0112 µM | codeine | [57] |

5. Methods for Colorimetric Detection of Illicit Substances

5.1. Principles and Mechanisms of Colorimetric Detection

5.2. POCT and Reagent-Based Colorimetric Detection

- (i) A distinct blue color if fentanyl is present;

- (ii) A pale blue color if fentanyl is absent.

5.3. Aptamer-Dye Complex and μPAD-Based Colorimetric Detection

6. Chemical Sensor Technologies for Environmental Toxin Detection

7. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2024; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Siefried, K.J.; Acheson, L.S.; Lintzeris, N.; Ezard, N. Pharmacological Treatment of Methamphetamine/Amphetamine Dependence: A Systematic Review. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, M.; Sadeghirad, B.; Bach, P.; Crabtree, A.; Javadi, S.; Sadeghi, E.; Moradi, S.; Mirzayeh Fashami, F.; Nakhaeizadeh, M.; Salehi, S.; et al. Management of Amphetamine and Methamphetamine Use Disorders: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 23, 4768–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, M.; Rees, V.W.; Lee, H.; Jalali, M.S. Assessment of Epidemiological Data and Surveillance in Korea Substance Use Research: Insights and Future Directions. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2024, 57, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Hyun, J.U.; Jang, H.W. Drug Sensors for Detecting Illegal Substances: Mechanisms, Materials, and Detection Methods. J. Sens. Sci. Technol. 2025, 34, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, N.; Suleman, S.; Singh, Y.; Kumari, S.; Parvez, S.; Pilloton, R.; Narang, J. The Evolution of Illicit-Drug Detection: From Conventional Approaches to Cutting-Edge Immunosensors-A Comprehensive Review. Biosensors 2024, 14, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzuk, M. Chemical Sensors for Toxic Chemical Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibi, C.; Liu, C.H.; Anandan, S.; Wu, J.J. Recent Advances on Electrochemical Sensors for Detection of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs). Molecules 2023, 28, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Stoll, S.; Singh, R.; Lee, W.H.; Hwang, J.-H. Recent advances in illicit drug detection sensor technology in water. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 168, 117295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jeon, Y.; Na, M.; Hwang, S.J.; Yoon, Y. Recent Trends in Chemical Sensors for Detecting Toxic Materials. Sensors 2024, 24, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendo, L.M.; Antunes, M.; Simao, A.Y.; Brinca, A.T.; Catarro, G.; Pelixo, R.; Martinho, J.; Pires, B.; Soares, S.; Cascalheira, J.F.; et al. Sensors in the Detection of Abused Substances in Forensic Contexts: A Comprehensive Review. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Niu, G.; Wu, H.; Coulon, F.; Yang, Z. Advances in Biosensor Technology for Illicit Drug Detection Enable Effective Wastewater Surveillance. Chem. Bio Eng. 2025, cbe.4c00188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gan, Y.; Chen, J.; Zheng, H.; Chang, Y.; Lin, C. Recent reports on the sensing strategy and the On-site detection of illegal drugs. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 6917–6929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; You, E.M.; Hu, R.; Wu, D.Y.; Liu, G.K.; Yang, Z.L.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, X.; et al. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: A half-century historical perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 1453–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boroujerdi, R.; Paul, R. Graphene-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Psychoactive Drugs. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Dong, T.; Bian, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, A. Metal-organic frameworks based fluorescent sensing: Mechanisms and detection applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 529, 216470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.Q.; Ge, L. Colorimetric Sensors: Methods and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 9887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loima, T.; Yoon, J.Y.; Kaarj, K. Microfluidic Sensors Integrated with Smartphones for Applications in Forensics, Agriculture, and Environmental Monitoring. Micromachines 2025, 16, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Pan, D.; Song, S.; Boey, F.Y.C.; Zhang, H.; Fan, C. Visual Cocaine Detection with Gold Nanoparticles and Rationally Engineered Aptamer Structures. Small 2008, 4, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y. Fast colorimetric sensing of adenosine and cocaine based on a general sensor design involving aptamers and nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005, 45, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, A.; Blues, E.; Williamson, P.; Cardona, M.; Gray, L.; Corrigan, D.K. SAM Composition and Electrode Roughness Affect Performance of a DNA Biosensor for Antibiotic Resistance. Biosensors 2019, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Sorescu, D.C.; Liu, Z.; Star, A. Machine Learning Discrimination and Ultrasensitive Detection of Fentanyl Using Gold Nanoparticle-Decorated Carbon Nanotube-Based Field-Effect Transistor Sensors. Small 2024, 20, e2311835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.; Wang, C.; Song, X.; Li, N.; Zheng, X.; Wang, C.; Su, M.; Liu, H. Strong pi-Metal Interaction Enables Liquid Interfacial Nanoarray-Molecule Co-assembly for Raman Sensing of Ultratrace Fentanyl Doped in Heroin, Ketamine, Morphine, and Real Urine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 12570–12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, K.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Hu, J. A novel colorimetric biosensor based on non-aggregated Au@Ag core-shell nanoparticles for methamphetamine and cocaine detection. Talanta 2017, 175, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.I.; Nanda, S.S.; Cho, S.; Lee, B.; Kim, B.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Yi, D.K. Gold Nanorod Density-Dependent Label-Free Bacteria Sensing on a Flake-like 3D Graphene-Based Device by SERS. Biosensors 2023, 13, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuknecht, F.; Kolataj, K.; Steinberger, M.; Liedl, T.; Lohmueller, T. Accessible hotspots for single-protein SERS in DNA-origami assembled gold nanorod dimers with tip-to-tip alignment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.T.; Lin, S.H.; Liu, K.K. A flexible plasmonic substrate for sensitive surface-enhanced Raman scattering-based detection of fentanyl. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 13903–13906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.; Bae, S.H.; Cao, S.; Wang, Z.; Raman, B.; Singamaneni, S. Gold-Nanorod-Based Plasmonic Nose for Analysis of Chemical Mixtures. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 3897–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynttinen, E.; Wester, N.; Lilius, T.; Kalso, E.; Mikladal, B.; Varjos, I.; Sainio, S.; Jiang, H.; Kauppinen, E.I.; Koskinen, J.; et al. Electrochemical Detection of Oxycodone and Its Main Metabolites with Nafion-Coated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Electrodes. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 8218–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, N.; Mynttinen, E.; Etula, J.; Lilius, T.; Kalso, E.; Kauppinen, E.I.; Laurila, T.; Koskinen, J. Simultaneous Detection of Morphine and Codeine in the Presence of Ascorbic Acid and Uric Acid and in Human Plasma at Nafion Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Thin-Film Electrode. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 17726–17734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Mohammadnia, M.S.; Ghalkhani, M.; Aghaei, M.; Sohouli, E.; Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M.; Arbabi, M.; Banafshe, H.R.; Sobhani-Nasab, A. Development of an electrochemical fentanyl nanosensor based on MWCNT-HA/Cu-H3BTC nanocomposite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 114, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, D.; Sammis, G.; Rezazadeh-Azar, P.; Ginoux, E.; Bizzotto, D. Development of a Graphene-Oxide-Deposited Carbon Electrode for the Rapid and Low-Level Detection of Fentanyl and Derivatives. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12706–12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Chen, H.; Xu, A.; Duan, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wang, S.; Bai, H. High-performance fentanyl molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensing platform designed through molecular simulations. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1312, 342686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Rana, M.; Geiwitz, M.; Khan, N.I.; Catalano, M.; Ortiz-Marquez, J.C.; Kitadai, H.; Weber, A.; Dweik, B.; Ling, X.; et al. Rapid, Multianalyte Detection of Opioid Metabolites in Wastewater. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3704–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rycke, E.; Stove, C.; Dubruel, P.; De Saeger, S.; Beloglazova, N. Recent developments in electrochemical detection of illicit drugs in diverse matrices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasscott, M.W.; Vannoy, K.J.; Iresh Fernando, P.U.A.; Kosgei, G.K.; Moores, L.C.; Dick, J.E. Electrochemical sensors for the detection of fentanyl and its analogs: Foundations and recent advances. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 132, 116037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Duan, S.; Chen, H.; Zou, F.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zeng, X.; Bai, H. A promising and highly sensitive electrochemical platform for the detection of fentanyl and alfentanil in human serum. Mikrochim. Acta 2023, 190, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truta, F.; Dragan, A.M.; Tertis, M.; Parrilla, M.; Slosse, A.; Van Durme, F.; de Wael, K.; Cristea, C. Electrochemical Rapid Detection of Methamphetamine from Confiscated Samples Using a Graphene-Based Printed Platform. Sensors 2023, 23, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.H.; Kadakia, S.; Agiwal, D.; Keshari, T.; Kumar, S. Borophene nanomaterials: Synthesis and applications in biosensors. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 1803–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimal, R.; Maridevaru, M.C.; Dube, A.; Wu, J.J.; Sambandam, A.; Ashokkumar, M. Borophene Nanosheet-Based Electrochemical Sensing toward Groundwater Arsenic Detection. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 15418–15427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, A.; Malode, S.J.; Alruwaili, M.; Alodhayb, A.N.; Maiyalagan, T.; Shetti, N.P. Borophene and Its Composite-Based Electrochemical Sensors. ChemElectroChem 2025, 12, e202400670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhu, Z. A Wearable Patch Sensor for Simultaneous Detection of Dopamine and Glucose in Sweat. Analytica 2023, 4, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Dkhar, D.S.; Singh, N.; Azad, U.P.; Chandra, P. Exploring the Potential Applications of Engineered Borophene in Nanobiosensing and Theranostics. Biosensors 2023, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, M.H.; Pervaiz, W.; Asif, M.; Huang, Z.; Dai, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, T.; Rao, Z.; Li, G.; et al. Engineering MXenes for electrochemical environmental pollutant sensing. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnath, K.; Selvi Gopal, T.; Josephine Malathi, A.C.; Pandiaraj, S.; Alruwaili, M.; Alshammari, A.; Alodhayb, A.N.; Abeykoon, C.; Grace, A.N.; Kumar, V.G. Electrochemical Detection of Dopamine and Uric Acid with Annealed Metal–Organic Framework/MXene (CuO/C/Ti3C2Tx) Nanosheet Composites for Neurotransmitter Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 12661–12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masekela, D.; Dlamini, L.N. Molecularly imprinted and MXene-based electrochemical sensors for detecting pharmaceuticals and toxic compounds: A concise review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhu, B.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Su, B. Recent Advances in MXene-Based Electrochemical Sensors. Biosensors 2025, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Sisican, K.M.; Ramos, R.M.C.; Judicpa, M.; Qin, S.; Zhang, J.; Yao, J.; Razal, J.M.; Usman, K.A.S. Progress towards efficient MXene sensors. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kim, H. Recent advances in MXene gas sensors: Synthesis, composites, and mechanisms. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2025, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Mishra, A. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Detection of Drugs of Abuse. In Metal-Organic Frameworks as Forensic Detectors; Mishra, V., Mishra, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Tufa, L.T.; Yan, X.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Ogawa, K.; Lee, J.; Hu, X. Ultrafast detection of an amphetamine-type derivative employing benzothiadiazole-based Zr-MOF: Fluorescence enhancement by locking the host molecular torsion. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Kan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, W. MOFs-Modified Electrochemical Sensors and the Application in the Detection of Opioids. Biosensors 2023, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hui, K.N.; San Hui, K.; Peng, S.; Xu, Y. Recent progress in metal-organic framework/graphene-derived materials for energy storage and conversion: Design, preparation, and application. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 5737–5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-N.; Shen, C.-H.; Huang, C.-W.; Tsai, M.-D.; Kung, C.-W. Defective Metal–Organic Framework Nanocrystals as Signal Amplifiers for Electrochemical Dopamine Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 3675–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghian, E.; Marzi Khosrowshahi, E.; Sohouli, E.; Ahmadi, F.; Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M.; Safarifard, V. A new electrochemical sensor for the detection of fentanyl lethal drug by a screen-printed carbon electrode modified with the open-ended channels of Zn(ii)-MOF. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 9271–9277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Harandi, M.-H.; Shabani-Nooshabadi, M.; Darabi, R. Cu-BTC Metal-Organic Frameworks as Catalytic Modifier for Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Determination of Methocarbamol in the Presence of Methadone. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 097507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousaabadi, K.Z.; Ensafi, A.A.; Rezaei, B. Simultaneous determination of some opioid drugs using Cu-hemin MOF@MWCNTs as an electrochemical sensor. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, G.; Kumar, K.S.; Chappanda, K.N.; Aggarwal, H. Zr-NDI MOF Based Optical and Electrochemical Dual Sensor for Selective Detection of Dopamine. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 8864–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer. Bestimmung der Absorption des rothen Lichts in farbigen Flüssigkeiten. Ann. Der Phys. 2006, 162, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.S.; Li, D.Y.; Li, N.T.; Liu, P.N. A concise synthesis of tunable fluorescent 1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran derivatives as new fluorophores. Dye. Pigment. 2015, 114, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Sanjay, S.T.; Zhou, W.; Brekken, R.A.; Kirken, R.A.; Li, X. Exploration of Nanoparticle-Mediated Photothermal Effect of TMB-H2O2 Colorimetric System and Its Application in a Visual Quantitative Photothermal Immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 5930–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, J.M.; Iglesias, B.A.; Martins, P.R.; Angnes, L. Recent advances in electroanalytical drug detection by porphyrin/phthalocyanine macrocycles: Developments and future perspectives. Analyst 2021, 146, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishchalnikov, R.Y.; Chesalin, D.D.; Kurkov, V.A.; Shkirina, U.A.; Laptinskaya, P.K.; Novikov, V.S.; Kuznetsov, S.M.; Razjivin, A.P.; Moskovskiy, M.N.; Dorokhov, A.S.; et al. A Prototype Method for the Detection and Recognition of Pigments in the Environment Based on Optical Property Simulation. Plants 2023, 12, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.S.; Pan, Y.; Pan, W.; Liu, S.; Li, N.; Tang, B. Bioimaging agents based on redox-active transition metal complexes. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 9468–9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuma, S.A.F.; Harmonis, J.A.; Pratiwi, R.; Hasanah, A.N. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Sensors: Properties and Application in Detection of Heavy Metals and Biological Molecules. Sensors 2023, 23, 8172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shellaiah, M.; Sun, K.-W. Review on Anti-Aggregation-Enabled Colorimetric Sensing Applications of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kaner, R.B. The intrinsic nanofibrillar morphology of polyaniline. Chem. Commun. 2006, 4, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Chen, Z.; Duan, C.; Wang, Z.; Yin, Q.; Huang, F.; Cao, Y. Polythiophene derivatives compatible with both fullerene and non-fullerene acceptors for polymer solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona-Villalpando, R.A.; Viveros-Palma, K.; Espinosa-Lagunes, F.I.; Rodriguez-Morales, J.A.; Arriaga, L.G.; Macazo, F.C.; Minteer, S.D.; Ledesma-Garcia, J. Comparative Colorimetric Sensor Based on Bi-Phase gamma-/alpha-Fe2O3 and gamma-/alpha-Fe2O3/ZnO Nanoparticles for Lactate Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, R.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Madhaiyan, K.; Amutha Barathi, V.; Lim, K.H.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrosprayed nanoparticles and electrospun nanofibers based on natural materials: Applications in tissue regeneration, drug delivery and pharmaceuticals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 790–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.K.; Late, D.J.; Morgan, H.; Rout, C.S. Recent developments in 2D layered inorganic nanomaterials for sensing. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 13293–13312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Cuc, T.T.; Nhien, P.Q.; Khang, T.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Hue, B.B.; Li, Y.K.; Wu, J.I.; Lin, H.C. Controllable FRET Behaviors of Supramolecular Host-Guest Systems as Ratiometric Aluminum Ion Sensors Manipulated by Tetraphenylethylene-Functionalized Macrocyclic Host Donor and Multistimuli-Responsive Fluorescein-Based Guest Acceptor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 20662–20680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligler, F.S. Fluorescence-Based Optical Biosensors. In Biophotonics; Pavesi, L., Fauchet, P.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Feng, J.; Hu, G.; Zhang, E.; Yu, H.H. Colorimetric Sensors for Chemical and Biological Sensing Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, D.; Wang, R. DNA-Based Biosensors for the Biochemical Analysis: A Review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.H.; Hong, G.L.; Lin, F.L.; Liu, A.L.; Xia, X.H.; Chen, W. Colorimetric detection of urea, urease, and urease inhibitor based on the peroxidase-like activity of gold nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 915, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panferov, V.G.; Liu, J. Optical and Catalytic Properties of Nanozymes for Colorimetric Biosensors: Advantages, Limitations, and Perspectives. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, E.; Lee, D.Y. Nanozyme-based colorimetric biosensor with a systemic quantification algorithm for noninvasive glucose monitoring. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6308–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philp, M.; Shimmon, R.; Tahtouh, M.; Fu, S. Development and validation of a presumptive color spot test method for the detection of synthetic cathinones in seized illicit materials. Forensic Chem. 2016, 1, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, J.R.; Agarwal, S.; Fortener, S.K.; Sprague, J.E. Fentanyl Detection Using Eosin Y Paper Assays. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.C.; Vara, M.; Reust, P.; Code, A.; Oliver, P.; Mace, C.R. Colorimetric Detection of Fentanyl Powder on Surfaces Using a Supramolecular Displacement Assay. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 3198–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y. Cu, I-doped carbon dots as simulated nanozymes for the colorimetric detection of morphine in biological samples. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 680, 115313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canoura, J.; Alkhamis, O.; Venzke, M.; Ly, P.T.; Xiao, Y. Developing Aptamer-Based Colorimetric Opioid Tests. JACS Au 2024, 4, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Navariya, S.; Gupta, P.; Singh, B.P.; Chopra, S.; Shrivastava, S.; Agrawal, V.V. A novel approach to low-cost, rapid and simultaneous colorimetric detection of multiple analytes using 3D printed microfluidic channels. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 231168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, K.A.; Basu, H.; Singhal, R.K.; Kailasa, S.K. Simultaneous colorimetric detection of four drugs in their pharmaceutical formulations using unmodified gold nanoparticles as a probe. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 19924–19932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, O.; Zolotovskaya, S.; Abdolvand, A.; Daeid, N.N. Biomimetic graphene oxide-cationic multi-shaped gold nanoparticle-hemin hybrid nanozyme: Tuning enhanced catalytic activity for the rapid colorimetric apta-biosensing of amphetamine-type stimulants. Talanta 2020, 216, 120990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfi, A.; Karimi, S.; Hassanzadeh, J. Molecularly imprinted polymers on multi-walled carbon nanotubes as an efficient absorbent for preconcentration of morphine and its chemiluminometric determination. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 93445–93452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrill, A.J.; Reily, N.E.; Macpherson, J.V. Addressing the practicalities of anodic stripping voltammetry for heavy metal detection: A tutorial review. Analyst 2019, 144, 6834–6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyburg, S.; Goryll, M.; Moers, J.; Ingebrandt, S.; Bocker-Meffert, S.; Luth, H.; Offenhausser, A. N-Channel field-effect transistors with floating gates for extracellular recordings. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 21, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Si, C.; Qiu, C.; Wang, G. Microplastics analysis: From qualitative to quantitative. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 1652–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-López, M.; Aguilar-Garay, R.; González-Rodriguez, D.E.; Mejía-Lopez, V.I.; Gamboa-Lugo, M.M.; Garibay-Febles, V.; Reyes-Guzmán, M.A.; Gordillo-Sol, Á.; Mendoza-Pérez, J.A. A Portable Optical Sensor for Microplastic Detection: Development and Calibration. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajan, R.I.; Manchu, M.; Felsy, C.; Joselin Kavitha, M. Microplastic predictive modelling with the integration of Artificial Neural Networks and Hidden Markov Models (ANN-HMM). J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, A.; Gandra, U.R.; Jaoudé, M.A.; Qurashi, A.; Price, G.J.; Burrows, A.D.; Mohideen, M.I.H. Advances in synthesis pathways towards metal-organic frameworks-fiber composites for chemical warfare agents and simulants degradation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 541, 216842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandra, U.R.; Pandey, R.P.; Palanikumar, L.; Irfan, A.; Magzoub, M.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Hasan, S.W.; Mohideen, M.I.H. Cu-TCPP Metal-Organic Nanosheets Embedded Thin-Film Composite Membranes for Enhanced Cyanide Detection and Removal: A Multifunctional Approach to Water Treatment and Environmental Safety. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 9563–9574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandra, U.R.; Lo, R.; Managutti, P.B.; Butt, A.M.; Reddy, P.S.; Qurashi, A.U.H.; Mohamed, S.; Mohideen, M.I.H. ICT-based fluorescent nanoparticles for selective cyanide ion detection and quantification in apple seeds. Analyst 2025, 150, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekkaramkodi, D.; Gandra, U.R.; Mettu, S.; Butt, H. Integration of rhodamine-based compounds into 3D-Printed structures for selective formaldehyde detection and food spoilage monitoring. Chemosphere 2025, 391, 144720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Mahajan, P.; Alsubaie, A.S.; Khanna, V.; Chahal, S.; Thakur, A.; Yadav, A.; Arya, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, G. Next-generation nanomaterials-based biosensors: Real-time biosensing devices for detecting emerging environmental pollutants. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 29, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Kim, N.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Hwang, H.; Kim, C.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.H.; et al. Peptide-Decorated Microneedles for the Detection of Microplastics. Biosensors 2024, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

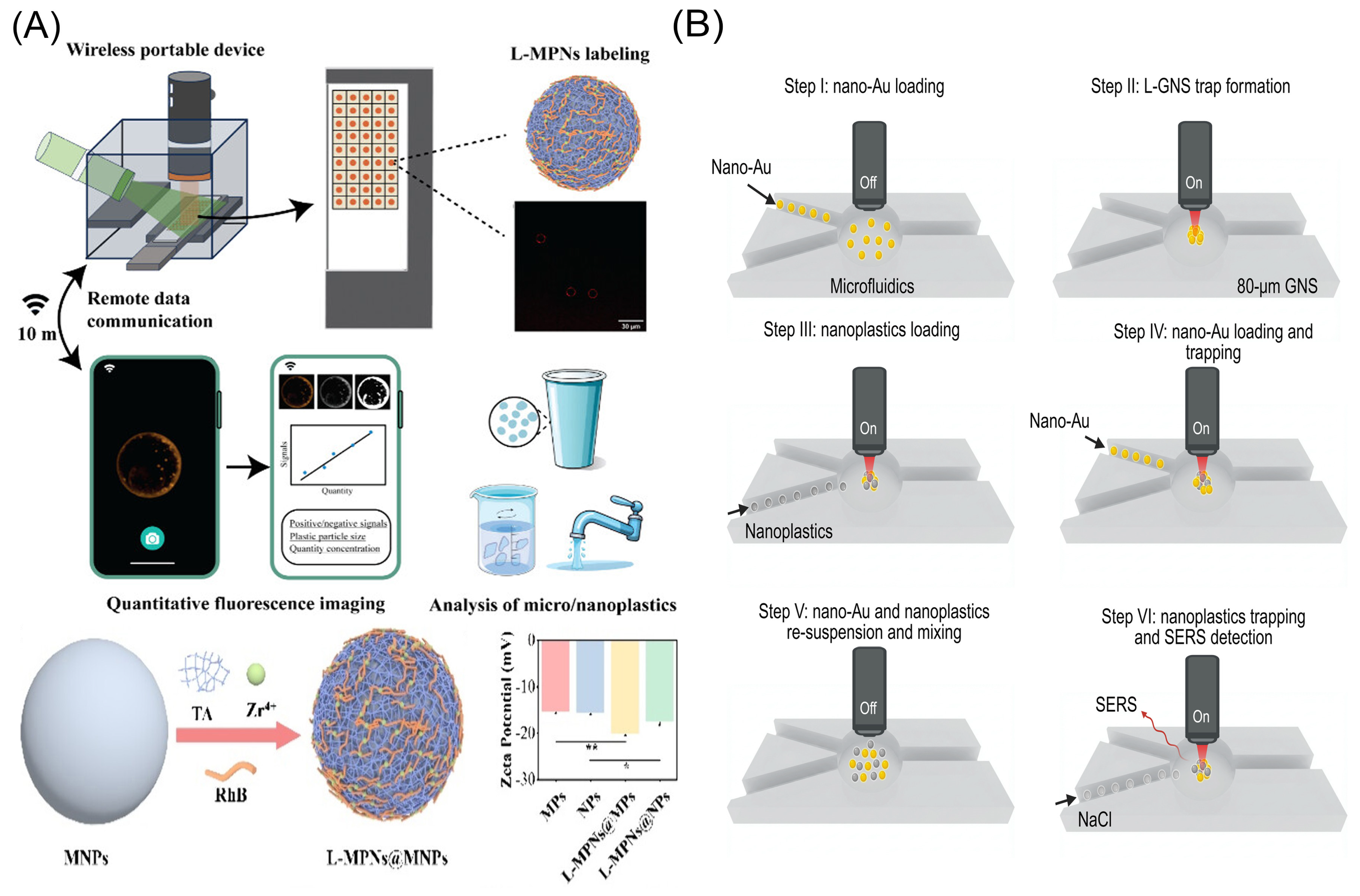

- Ye, H.; Zheng, X.; Yang, H.; Kowal, M.D.; Seifried, T.M.; Singh, G.P.; Aayush, K.; Gao, G.; Grant, E.; Kitts, D.; et al. Cost-Effective and Wireless Portable Device for Rapid and Sensitive Quantification of Micro/Nanoplastics. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 4662–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Mao, T.; Huang, X.; Shi, H.; Jiang, K.; Lan, R.; Zhao, H.; Ma, J.; Zhao, J.; Xing, B. Capturing, enriching and detecting nanoplastics in water based on optical manipulation, surface-enhanced Raman scattering and microfluidics. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, R.F.; Funk, E.; Henry, C.S.; Borch, T. Sensors for detecting per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A critical review of development challenges, current sensors, and commercialization obstacles. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omo-Okoro, P.; Ofori, P.; Amalapridman, V.; Dadrasnia, A.; Abbey, L.; Emenike, C. Soil Pollution and Its Interrelation with Interfacial Chemistry. Molecules 2025, 30, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Du, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Zhu, B.; Kitaguchi, T.; Huang, C. A Review on the Application of Biosensors for Monitoring Emerging Contaminants in the Water Environment. Sensors 2025, 25, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, M.A.; Arroyo-Curras, N. Study of surface modification strategies to create glassy carbon-supported, aptamer-based sensors for continuous molecular monitoring. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 5627–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushparajah, S.; Shafiei, M.; Yu, A. Current Advances in Aptasensors for Pesticide Detection. Top. Curr. Chem. 2025, 383, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Lian, C.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. AI-Enhanced Electrochemical Sensing Systems: A Paradigm Shift for Intelligent Food Safety Monitoring. Biosensors 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, S.; Huang, X.; Yao, C.; Chen, J.; Gao, L.; Zhou, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; et al. Aptamers-based wearable electrochemical sensors for continuous monitoring of biomarkers in vivo. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Jin, M.; Vikesland, P.J. Machine Learning-Assisted Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Detection for Environmental Applications: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 20830–20848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.A.; Abd-Elaziem, W.; Elsheikh, A.; Zayed, A.A. Advancements in nanomaterials for nanosensors: A comprehensive review. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 4015–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Methods | Limit of Detection | Target Drugs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNPs | SERS | 1 ng/mL | heroin, morphine, fentanyl, ketamine | [23] |

| Aptamer and AuNPs | visual color change | 2 µM | cocaine | [19] |

| DNA and AuNPs | visual color change | 2 mM; 50 µM | adenosine; cocaine | [20] |

| AuNPs and CNT | FET sensor | 10.8 fg/mL | fentanyl | [22] |

| Au@Ag core shell NPs | visual color change | 14.9 ng/L | methamphetamine, cocaine | [24] |

| Yolk-shell AuNR@Au/Ag | SERS | 4.89 ng/mL | fentanyl | [27] |

| Nafion/SWCNT | DPV | 0.05–50 µM | morphine, codeine | [30] |

| MWCNT-HA/Cu-H3BTC | DPV | 0.03 µM | fentanyl | [31] |

| Materials | Methods | Limit of Detection | Target Drugs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIM@ErGO | SWV | 1.28 nM | fentanyl | [33] |

| Graphene/aptamers | FET | 38, 27, 42 pg/mL | NX, EDDP, NF | [34] |

| COF@rGO | SWV | 33 nM | fentanyl, alfentanil | [37] |

| GPH-screen-printed electrodes | SWV | 0.3 µM | methamphetamine | [38] |

| Sensor Type | Detection Limit | Specificity | Target Drugs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eosin Y | 1% | medium | fentanyl | Canfield et al., 2020; [80] |

| Aptamer | 0.5 μM | high (95% acc.) | heroin | Canoura et al., 2024; [83] |

| CB Host | 10 mM | high | fentanyl | Mora et al., 2024; [81] |

| Au NPs | 0.9–9.3 nM | low–medium | venlafaxine, imipramine, | Rawat et al., 2015; [85] |

| Nanozyme | 28.6–34.1 ng/mL | high | amphetamine, methamphetamine | Adegoke et al., 2020; [86] |

| MIPs | 0.82 μg/L | medium–high | morphine | Lotfi et al., 2016; [87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hossain, M.I.; Yi, D.K.; Kim, S. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based and Colorimetric Technologies for Detecting Illicit Drugs and Environmental Toxins. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020693

Hossain MI, Yi DK, Kim S. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based and Colorimetric Technologies for Detecting Illicit Drugs and Environmental Toxins. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020693

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossain, Md Imran, Dong Kee Yi, and Sanghyo Kim. 2026. "Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based and Colorimetric Technologies for Detecting Illicit Drugs and Environmental Toxins" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020693

APA StyleHossain, M. I., Yi, D. K., & Kim, S. (2026). Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based and Colorimetric Technologies for Detecting Illicit Drugs and Environmental Toxins. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 693. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020693