The Concept of a Hierarchical Digital Twin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Digital Twin Concept

- Physical layer—the actual object or system;

- Data layer—collects raw data from sensors and devices;

- Connectivity layer—transmits data to a centralized system;

- Data processing layer—cleanses and organizes data for usability;

- Modeling and simulation layer—creates digital replicas using models and simulations;

- Data analysis and intelligence layer—uses artificial intelligence and analytics to obtain actionable insights;

- Control and automation layer—provides feedback and control of the physical system;

- User interaction layer—interfaces for engaging users;

- Visual layer—presents data and models visually.

2.1. Frames of Reference and Standardization

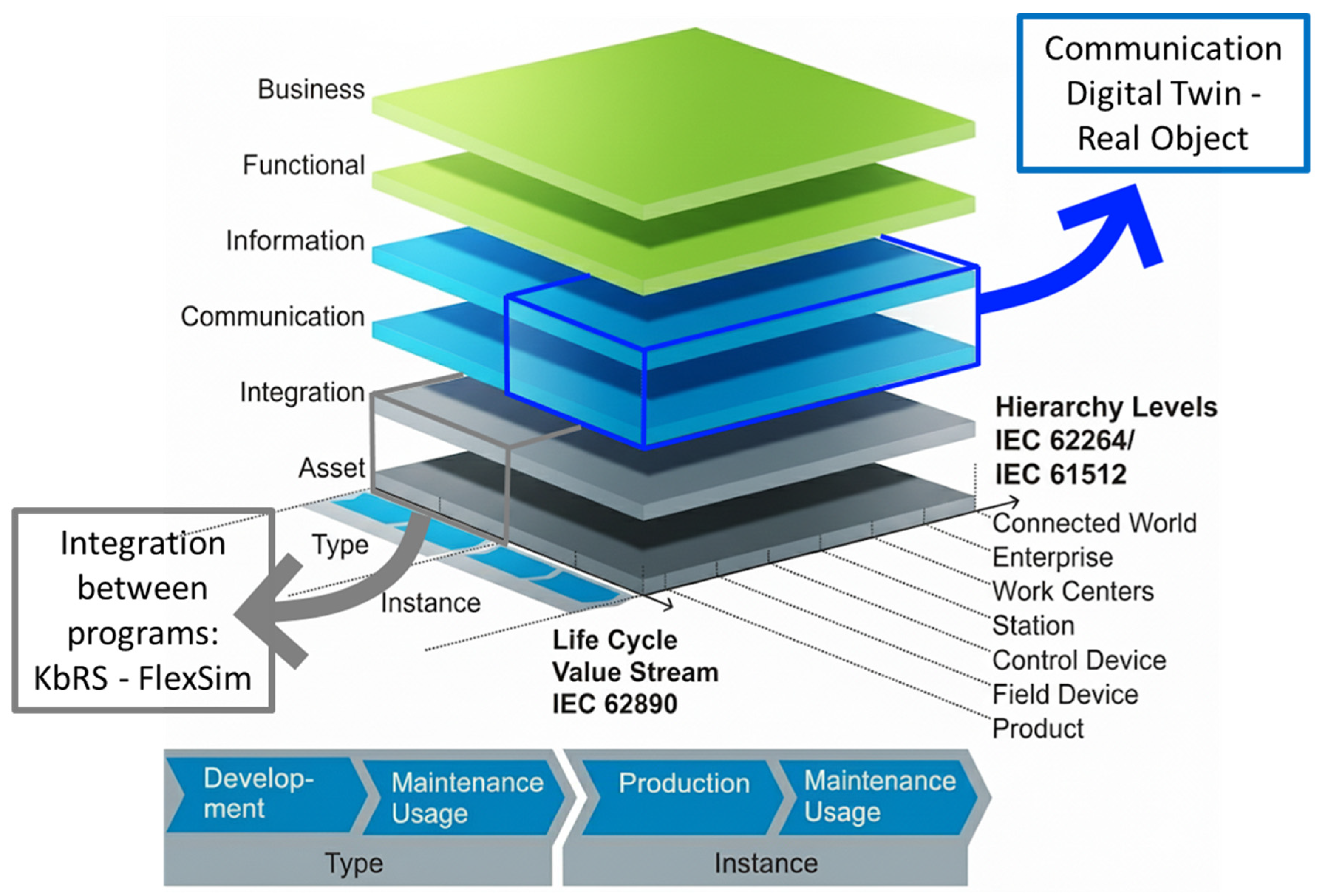

- RAMI 4.0. (Reference Architectural Model of Industry 4.0) is a reference architecture model for Industry 4.0 that defines the structures and relationships between various system components. Its task is to organize interoperability and integration along three axes: (1) layers (from resource to business), (2) IEC 62264 [52]/IEC 61512 [53] hierarchies (from field to enterprise), and (3) the product life cycle according to IEC 62890 [54]. RAMI 4.0 combines existing standards (including OPC UA, IEC/ISO) and defines an I4.0 component as a functional “wrapper” of a resource with semantics and interfaces [3].

- ISO 23247 (Digital Twin Framework for Manufacturing) is a series of standards (from 2021) defining a framework for the creation and operation of manufacturing twins, covering terminology, stakeholder roles, logical and component architecture, mechanisms for identifying “observable elements” (product/process/resource), and data flows and synchronization. Additionally, NIST literature presents an analysis of the 23247 series and how it can be specialized for discrete, batch, and continuous manufacturing [55].

2.2. Digital Twin in Production—Overview of Concepts and Taxonomies

- Representation object (product, process, resource, production system);

- Lifecycle stage (design, planning, commissioning, operation, service);

- Functions (monitoring, diagnostics, optimization, prediction, control);

- Techniques—multi-scale simulation, analytics/ML, model calibration, anomaly detection. Recent work emphasizes the need for a common taxonomy of DT applications in manufacturing, combining functional aspects and implementation maturity.

2.3. Applications in a Smart Factory

- Predictive maintenance and reliability: Real-time twins of machines, lines, and systems (e.g., robots, CNC machine tools) allow for the prediction of degradation, the planning of condition-based maintenance, and the minimization of downtime. Combining physical models (model-based) with data (data-driven) increases prediction accuracy.

- Flow and planning optimization: DT for production cells and lines supports scheduling, load balancing, layout configuration, and “what-if” scenarios (including reconfiguration of small-batch production/mass customization). In flexible production cells, DT reduces commissioning effort and shortens changeover times.

- Quality and production startup: Real-time twins of processes (e.g., welding, 3D printing, molding) enable parametric control, automatic calibration, and closing the quality loop (in-line metrology → setpoint correction).

- Safety and ergonomics: Virtual commissioning and HRI (human–robot interaction) simulations reduce the risk of accidents and enable the design of workstations with operator safety and workload in mind.

- Energy management and sustainability: Utility twins (UTs) model utility consumption, emissions, and costs, supporting ESG decisions and certifications (e.g., ISO 50001 [61]), as well as demand response management.

- Data management and security: Legal challenges (data ownership, NDAs), OT/IT cyber-security, and business continuity requirements.

- Model validation and trust: DT reliability requires continuous validation/recalibration; black-box ML applications limit auditability.

- Scalability in SMEs: Competency and investment barriers, as well as the lack of ready-made domain “templates”, hinder adoption.

- Integration complexity: Combining disparate systems and technologies into a single, coherent structure can be difficult and costly.

- Security and privacy: Storing and processing large amounts of data require appropriate security measures against cyber threats [62].

- Data management: Effective data management, quality, and timeliness are crucial to the effectiveness of digital twins.

3. Materials and Methods

- Production scheduling and resource planning using a proprietary tool (KbRS (ver. 20250524);

- Production flow simulation using simulation software (FlexSim (ver. 2025);

- Mathematical modeling of the production system (description of resources, stations, buffers, AGV trolleys, routes);

- Scenario-based disruption analysis, taking into account various potential problems (missortment, delays, transport conflicts);

- Collecting input data: Production orders, resource structure, operation times, transport routes—in the KbRS tool;

- Automatic generation of production schedules and data structures;

- Data transfer to the simulation model (FlexSim)—hierarchical integration of tools;

- Building the simulation model (stations, flows, buffers, AGV trolleys, assembly stations);

- Simulations for various scenarios (baseline, with errors, with delays, with process reorganization);

- Result analysis: assessing the impact on production lead time (Cmax), identifying bottlenecks, and assessing the cost-effectiveness of interventions (e.g., purchasing a robot, changing procedures).

- Level II—planning and engineering tools (KbRS, CAx/CAD): Generation of production data, resource plans, AGV routes, order structures, BOMs, and variants.

- Level I—simulation tool (FlexSim): Simulation of production, transportation, assembly, and internal logistics flows using data from Level II.

- Integration layer: A data exchange mechanism (e.g., Excel files, databases) between tools, and automating data transfer without repeated manual data entry.

- PPi—number of production processes;

- BPp—number of buffers at the stands;

- Mj—number of resources;

- AGk—number of AGV trolleys;

- TJm—number of routes.

- St—stand;

- iDost—resource availability;

- iKos—unit labor cost;

- iPrac—list of employees in resources;

- iKal—working time calendar.

- WS—series size (number of elements of the i-th order);

- PP—production process, (PP = 1…j—number of production processes);

- T—execution time of the i-th order;

- BS—number of elements in the production batch of the i-th order;

- TP—the period of introducing production batches of the i-th order;

- CZ—cost of executing of the i-th order.

3.1. The Concept of Creating a Hierarchical Digital Twin

- I—inputs—energy, raw materials, information;

- SO—simulation objects—machines, trolleys AGV, robots, employees, stores, conveyors;

- C—connection between simulation objects;

- CT—constraints—parameters of processes;

- T—time;

- O—outputs, finished products.

3.2. Scenario 1

3.3. Scenario 2

3.4. Scenario 3

4. Results and Discussion

- Scenario 1—The problem was that the truck either did not reach a specific machine or did not reach it at all. In this scenario, additional interlocks and controls were introduced to minimize the number of trucks that did not reach a specific machine. Signal amplification was also implemented to prevent the truck’s signal from being lost in the hall. The results obtained for the Cmax completion time were 461 min.

- Scenario 2—Machine delays. This problem poses a high risk of not completing production on time. As indicated by the schedule, the completion of production tasks has been postponed and requires urgent action. Thanks to this analysis, we know when production will be completed. In line with the just-in-time principle, the decision was made to purchase a robot that will perform the task of feeding glass to the assembly station. The purchase of the robot will solve the problem of a shortage of the required number of workers. The results regarding the Cmax completion time were 511 min.

- Scenario 3—A problem with the order in which the glass panes were delivered to the station and their proper arrangement. To this end, standardization of work at the station and Poka–Yoke were implemented to eliminate human error during glass loading. The changes introduced at the station improved the glass loading process. In this scenario, the data is exactly as is in Scenario 1, but if the times associated with a station failure due to incorrect glass loading order are added, the Cmax production completion time will increase.

5. Conclusions

- Problems with AGV trolleys’ access to station;

- Delays on selected machines in just-in-time mode;

- Incorrect sequencing of components (glass) in an assembly station.

- Improves order planning and execution;

- Enables rapid response to disruptions;

- Requires consistent data management and user training;

- Increases production flexibility and efficiency in the context of Industry 4.0.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Digital twin |

| KbRS | Knowledge-based rescheduling system |

| IoT | Internet Of Things |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DM | Digital models |

| RMS | Reconfigurable manufacturing system |

| DS | Digital shadow |

| CNC | Computerized numerical control |

| UT | Utility twin |

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| OEE | Overall equipment effectiveness |

| SME | Small- and medium-sized enterprises |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| AGV | Automated guided vehicle |

| Cmax | Production lead time |

| CAx | Computer-aided technologies |

| CAD | Computer-aided design |

| JIT | Just-in-time |

References

- Monostori, L.; Kádár, B.; Bauernhansl, T.; Kondoh, S.; Kumara, S.; Reinhart, G.; Sauer, O.; Schuh, G.; Sihn, W.; Ueda, K. Cyber-physical systems in manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Wang, J.; Ye, L.; Gao, R.X. Digital Twin for Machining Tool Condition Prediction. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q.; Wang, L.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twins and Cyber–Physical Systems toward Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: Correlation and Comparison. Engineering 2019, 5, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiza, G.; Sanz, R. Immersive Digital Twin under ISO 23247 Applied to Flexible Manufacturing Processes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastes, R. Digital twin for smart manufacturing, A review. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2023, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gao, R.X.; Fan, Z. Cloud computing for cloud manufacturing: Benefits and limitations. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2015, 137, 040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuehlke, D. Smart Factory-towards a factory-of-things. Annu. Rev. Control 2010, 34, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagermann, H.; Wahlster, W.; Helbig, J. Securing the Future of German Manufacturing Industry: Recommendations for Implementing the Strategic Initiative Industrie 4.0; Final Report of the Industrie 4.0 Working Group; Acatech—National Academy of Science and Engineering: Munich, Germany, 2013; 678p. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A. Digital twin in industry: State-of-the-art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, M.; Xu, W.; Qi, Q. Theories and technologies for cyber-physical fusion in digital twin shop-floor. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 23, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks, T.M.; Lacy, T.E.; Pineda, E.J.; Bednarcyk, B.A.; Arnold, S.M. Computationally efficient solution of the high-fidelity generalized method of cells micromechanics relations. In Proceedings of the American Society for Composites 30th Annual Technical Conference, East Lansing, MI, USA, 28–30 September 2015; Available online: https://www.cavs.msstate.edu/publications/docs/2015/09/140441700_Ricks.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Cai, Y.; Starly, B.; Cohen, P.; Lee, Y.S. Sensor data and information fusion to construct digital-twins virtual machine tools for cyber physical manufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 10, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.; Wichert, G.V.; Lo, G.; Bettenhausen, K.D. About the importance of autonomy and digital twins for the future of manufacturing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachálek, J.; Bartalsky, L.; Rovny, O.; Sismisova, D.; Morhac, M.; Loksik, M. The digital twin of an industrial production line within the industry 4.0 concept. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Process Control (PC), Strbske Pleso, Slovakia, 6–9 June 2017; pp. 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Manufacturing Digital Twin Standards. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Engineering Digital Twins (EDTconf 2024), Linz, AT, USA, 23–24 September 2024; Available online: https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=957622 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lindner, M.; Bank, L.; Schilp, J.; Weigold, M. Digital Twins in Manufacturing: A RAMI 4.0 Compliant Concept. Sci 2023, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, E.; Fani, V.; Bandinelli, R.; Lacroix, S.; Le Duigou, J.; Eynard, B.; Godart, X. Literature Review and Comparison of Digital Twin Frameworks in Manufacturing. 2023. Available online: https://www.scs-europe.net (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Leng, J.; Wang, D.; Shen, W.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Digital twins-based smart manufacturing system design in Industry 4.0: A review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, J.F.; Qi, Q.L. Digital twin workshop: A new paradigm for future workshop. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q.; Qu, T.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, W.; Xu, J.; et al. Digital twin and its potential application exploration. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M. Digital Twin: Manufacturing Excellence Through Virtual Factory Replication. White Paper. 2014. Available online: https://www.apriso.com/library/Whitepaper_Dr_Grieves_DigitalTwin_Manufacturing Excellence.php (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Maurer, T. What Is a Digital Twin? 2017. Available online: https://community.plm.automation.siemens.com/t5/Digital-Twin-Knowledge-Base/What-is-a-digital-twin/ta-p/432960 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Tuegel, E.J. The airframe digital twin some challenges to realization. In Proceedings of the 53rd AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics and Materials Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 April 2012; p. 1812. [Google Scholar]

- Schluse, M.; Rossmann, J. From simulation to experimentable digital twins: Simulation-based development and operation of complex technical systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineering (ISSE), Edinburgh, UK, 3–5 October 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M. Digital twin shop-floor: A new shop-floor paradigm towards smart manufacturing. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 20418–20427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, B.R.; Krishnamurthy, T. Structural health management of damaged aircraft structures using the digital twin concept. In Proceedings of the 25th AIAA/AHS Adaptive Structures Conference, Grapevine, TX, USA, 9–13 January 2017; p. 1675. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, C.B.; Liu, J.H.; Xiong, H.; Ding, X.; Liu, S.; Weng, G. Connotation, architecture and trends of product digital twin. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 23, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedo, A. Industrial IoT lifecycle via digital twins. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE/ACM/IFIP International Conference on Hardware/Software Codesign and System Synthesis, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1–7 October 2016; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Fan, S.T.; Peng, G.Y.; Dai, S.; Zhao, G. Study on application of digital twin model in product configuration management. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 526, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Sui, F.; Liu, A.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Song, B.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S.C.-Y.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital twin-driven product design framework. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 57, 3935–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleich, B.; Anwer, N.; Mathieu, L.; Wartzack, S. Shaping the digital twin for design and production engineering. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 66, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, P.K.; Faisalhaider, M.; Reifsnider, K. Multi-physics response of structural composites and framework for modeling using material geometry. In Proceedings of the 54th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 8–11 April 2013; p. 1577. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, G.N.; Steinmetz, C.; Pereira, C.E.; Muller, I.; Garcia, N.; Espindola, D.; Rodrigues, R. Visualising the digital twin using web services and augmented reality. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Poitiers, France, 12–15 July 2016; pp. 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobottka, T.; Halbwidl, C.; Gaal, A.; Nausch, M.; Fuchs, B.; Hold, P.; Czarnetzki, L. Optimizing operations of flexible assembly systems: Demonstration of a digital twin concept with optimized planning and control, sensors and visualization. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 5375–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Son, Y.H.; Lee, D.; Noh, S.D. Digital Twin-Based Integrated Assessment of Flexible and Reconfigurable Automotive Part Production Lines. Machines 2022, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 23247; Automation Systems and Integration—Digital Twin Framework for Manufacturing—Part 4: Information Exchange. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:23247:-4:ed-1:v1:en33.3+18.4+22.5 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Rojas Catalán, V.; Valín, J.L.; Muñoz-La Rivera, F.; Ortega, J.; Norambuena, N.; Ramirez, E.; Galleguillos Ketterer, C.I. Virtual Reality and Digital Twins for Catastrophic Failure Prevention in Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ji, P.; Ma, H.; Xing, L. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin from the Perspective of Total Process: Data, Models, Networks and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaś, W.; Gołda, G.; Gwiazda, A.; Jarzyńska, M.; Kampa, A.; Kalinowski, K.; Olender-Skóra, M.; Stawowiak, M. The use of simulation techniques and management tools to optimize the logistics process. LogForum 2024, 20, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Leng, J.; Chen, X. Digital Twin-Driven Rapid Individualised Designing of Automated Flow-Shop Manufacturing System. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3903–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluse, M.; Priggemeyer, M.; Atorf, L.; Rossmann, J. Experimentable Digital Twins—Streamlining Simulation-Based Systems Engineering for industry 4.0. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Jiangfeng, C.; Qinglin, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Fangyuan, S. Digital Twin-Driven Product Design, Manufacturing and Service with Big Data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 3563–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.; Leong, S. The Expanding Role of Simulation in Future Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2001 Winter Simulation Conference, Arlington, VA, USA, 9–12 December 2001; IEEE Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 1478–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, G.N.; Steinmetz, C.; Pereira, C.E.; Espindola, D.B. Digital Twin Data Modeling with Automation and a Communication Methodology for Data Exchange. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.T.; Jeon, S.W.; Noh, S.D. Digital Twin Application with Horizontal Coordination for Reinforcement-Learning-Based Production Control in a Re-Entrant Job Shop. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 60, 2151–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin Driven Smart Manufacturing; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, M.G.; Ulsoy, A.G.; Koren, Y.; Heytler, P. Trends and Perspectives in Flexible and Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems. J. Intell. Manuf. 2002, 13, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pańkowska, M.; Żytniewski, M.; Kozak, M.; Tomaszek, K.; Banaś, W.; Herbuś, K. Robotic arm digital twin for pathomorphological diagnosis process. In Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development; Ziemba, E.W., Grzenda, W., Ramsza, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2026; pp. 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, X. Predictive maintenance for switch machine based on digital twins. Information 2021, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital twin: Mitigating unpredictable, undesirable emergent behavior in complex systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches, 1st ed.; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Understanding Digital Twins: How They Work and Why They Matter. Available online: https://www.prevu3d.com/news/understanding-digital-twins/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- IEC 62264; Enterprise-Control System Integration—Part 4: Objects and Attributes for Manufacturing Operations Management Integration. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iec:62264:-4:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- IEC 61512; Batch Control—Part 4: Batch Production Records. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/5531 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- IEC 62890; Industrial-Process Measurement, Control and Automation. Life-Cycle-Management for Systems and Components. Available online: https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/industrial-process-measurement-control-and-automation-life-cycle-management-for-systems-and-components (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Cao, H.; Söderlund, H.; Fang, Q.; Chen, S.; Erdal, L.; Gubartalla, A. Towards AI-based Sustainable and XR-based human-centric manufacturing: Implementation of ISO 23247 for digital twins of production systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.14580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesse, T.Y.; Di Pasquale, V.; Riemma, S. Digital Twin models in industrial operations: State-of-the-art and future research directions. IET Collab. Intellig. Manuf. 2021, 3, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Viquez, D.; Zamora-Hernandez, M.; Fernandez-Vega, M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, J.; Azorin-Lopez, J. A Comprehensive Review of AI-Based Digital Twin Applications in Manufacturing: Integration Across Operator, Product, and Process Dimensions. Electronics 2025, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abisset-Chavanne, E.; Coupaye, T.; Golra, F.R.; Lamy, D.; Piel, A.; Scart, O.; Vicat-Blanc, P. A Digital Twin use cases classification and definition framework based on Industrial feedback. Comp. Ind. 2024, 161, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zami, B.; Shaon, S.; Quy, V.K.; Nguyen, D.C. Digital Twin in Industries: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.00209v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 50001; Energy Management System Implementation Guide. Available online: https://www.nqa.com/medialibraries/NQA/NQA-Media-Library/PDFs/NQA-ISO-50001-Implementation-Guide.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Liu, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, V.; Yang, X.; Wang, L. Review of Digital Twin in the Automotive Industry on Products, Processes and Systems. Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2025, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampa, A.; Michalski, P. Virtual prototyping and implementation of a PLC-based sorting line using digital twin simulation in FlexSim. Int. J. Mod. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 17, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reference Architecture Model Industrie 4.0 (RAMI 4.0). Available online: https://www.university4industry.com/player/chapter/reference-architecture-model-industrie-40-rami-40-2?exitToUrl=https://www.university4industry.com/themenbereiche/iot-connectivity/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jarzyńska, M.; Nierychlok, A.; Olender-Skóra, M. The Concept of a Hierarchical Digital Twin. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020605

Jarzyńska M, Nierychlok A, Olender-Skóra M. The Concept of a Hierarchical Digital Twin. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):605. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020605

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarzyńska, Magdalena, Andrzej Nierychlok, and Małgorzata Olender-Skóra. 2026. "The Concept of a Hierarchical Digital Twin" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020605

APA StyleJarzyńska, M., Nierychlok, A., & Olender-Skóra, M. (2026). The Concept of a Hierarchical Digital Twin. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020605