1. Introduction

Effective spare parts management (SPM) is crucial in the pursuit of achieving cost-efficient equipment operation through maintenance. Organizations face persistent challenges in prioritizing the availability of spare parts, which is critical since most maintenance work cannot be undertaken without the necessary parts [

1]. If equipment fails to operate, immediate spare part availability is desired as the downtime is prone to be fixed with the part lead time [

2,

3]. Spare parts stocking is one strategy to mitigate this risk, but this locks capital, creating a trade-off between operational costs, equipment risks, and availability. As the number of spare parts and associated data volumes increase, decision-makers continue to rely on tacit knowledge and simple methods, such as single-criterion ABC classification [

4,

5].

Stochastic frequencies and irregular demand patterns driven by infrequent and fluctuating failure rates characterize spare parts demand [

1,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. These characteristics challenge the forecasting of spare parts consumption for future maintenance [

11,

12]. Equipment bills of materials (BOMs) and maintenance plans may support spare parts availability planning [

13], but as equipment ages, components become obsolete, drastically expanding the spare parts portfolios. Consequently, decision-makers need to gather and consider overwhelming variant numbers and data volumes when reviewing spare parts [

5,

14,

15].

SPM responsibilities are distributed between the maintenance, procurement, and logistics departments, each having distinct responsibilities, objectives, and data [

1,

16]. Roda et al. [

17] report that SPM data are often departmentally siloed, creating fragmented visibility often reflected in computerized maintenance management systems (CMMSs), in which the plant maintenance (PM) and materials management (MM) modules provide separate overviews of the same spare parts. This data fragmentation complicates SPM decision-making on whether and how to stock a spare part.

Despite the wide SPM methodology availability, the literature documents a persistent gap between theoretical methods and practical applications. The application of advanced data-driven models is, in practice, limited due to their mathematical complexity [

15], the misalignment in defining critical data needs between industry and research [

18], large and increasing data volumes to consider and gather [

5], and the fragmentation of data across siloed departments and IT systems [

1,

5,

10,

19]. A review of 60 SPM contributions confirmed this data siloing gap, and that research lacks the integration of data covering SPM-relevant knowledge areas collectively. Consequently, decision-makers remain challenged by extensive data-gathering requirements and a reliance on simple methods with limited data coverage of SPM knowledge areas. Bridging the research gap concerning data siloing is considered critical in the pursuit of solving current SPM challenges [

16,

17].

This study proposes an empirical SPM data model linking spare parts with maintenance, logistics, inventory, and equipment data, thereby addressing the aforementioned gap by bridging fragmented data, departmental knowledge areas, and IT system silos. The model consolidates 50 SPM-relevant data fields and aligns them with empirical CMMS data structures, forming a coherent SPM database. Furthermore, the model reduces data-gathering efforts through automation while establishing an empirical and common decision-support database across departmental knowledge area silos. The following research questions guide this study:

What data are cited in research and applied in practice to inform SPM decision-making, contributing to stock management policy decisions?

How can these data be integrated into an empirical data model linking the siloed SPM knowledge areas?

What are the effects of implementing the empirical SPM data model in decision-making practices?

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: First, the research methodology is presented. Next, SPM knowledge area data coverage is investigated through a systematic literature review. Then, the proposed empirical SPM data model is introduced, followed by a longitudinal case study assessing the effects of implementing the model in decision-making practices. Lastly, a discussion and a conclusion address the study’s implications and future research directions.

2. Research Methodology

A prescriptive research approach was applied in this study, combining a systematic literature review and a longitudinal case study in an offshore oil and gas exploration and production (E&P) company operating approximately 50 offshore installations in the North Sea. The focus of this study was phenomenon exploration, theory building, and testing, which makes the case study methodology appropriate [

20,

21]. The research was conducted in two phases, which are presented in the following subsections.

2.1. Phase 1—Exploratory Study

A preliminary exploratory study aimed to identify existing domain-specific SPM data while investigating SPM processes and interfaces across the organization. Both qualitative and quantitative methods were applied over four months. In total, 129 guidelines and procedure documents were reviewed, two warehouses were investigated, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted, and three workshops were held. The semi-structured interviews and workshops were conducted with four logistics, two procurement, two maintenance, and four warehouse employees. Data sources and process linkages were identified through qualitative work, while quantitative CMMS data supported the data model development.

This initial data model was developed from seven maintenance-related datasets containing 18,758,495 rows of data distributed across 137 fields, and 44 SPM-related datasets containing 761,437 rows of data distributed across 794 fields. The data model was iterated five times and expanded through the identification of domain-specific data, connecting data to the SPM processes, and linking data between organizational knowledge silos. This formed the basis for an empirical SPM decision-support data model that integrates data from the CMMS’s PM and MM modules.

2.2. Phase 2—Prescriptive Research

The case company required the maintenance personnel to review the repairability and stock management policy for 10,843 spare parts to increase stock reliability for equipment BOMs and reduce excess stock. Each decision-maker was required to classify parts relating to their technical expertise by determining repairability, whether to stock, and the stock type, quantity, and re-ordering point. The decisions were to be applied as updated material requirement planning (MRP) coding for each spare part. Two different approaches and decision-support databases had failed due to challenges in gathering the fragmented inventory, logistics, procurement, maintenance, and equipment data.

Based on the exploratory model, a refined empirical SPM data model was developed and implemented, enabling a third approach that yielded a successful project completion. The three different approaches and decision bases were documented through the longitudinal case study presented in this paper.

The prescriptive research spanned 19 months, with 20 semi-structured interviews and five workshops, including 25 maintenance planners, two maintenance support employees, two stock controllers, one procurement manager, two logistics support employees, and one logistics support manager. This qualitative research enabled data identification, model co-creation, and testing of the data model.

Data were extracted from the CMMS’s PM and MM modules for a 12-year period, including PM module records of 10,843 spare parts linked to BOMs of 20,096 offshore equipment items across 17 assets, 35 sectors, 211 systems, and 644 subsystems. Additionally, PM module records were extracted for 45,016 offshore equipment items where the spare parts had been consumed, across 19 assets, 42 sectors, 311 systems, and 1108 subsystems. All procurement, logistics, and inventory records for the spare parts were extracted from the MM module for the same period. The data were modeled in the business intelligence software MS Power BI version 2.131.901.0 and continuously validated by company experts and through cross-checking with the CMMS. The proposed empirical SPM data model is considered a database architecture built on top of CMMS as an analytical (read-only) layer for linking and structuring SPM data without altering the native CMMS schema. The practical model application is realized through business intelligence software, and the data pipeline utilizes routine-based front-end CMMS data table extractions stored in a secure cloud-based environment. The model automatically refreshes on these sources in a case company-defined frequency, thus eliminating data gathering for the decision-makers.

2.3. Systematic Literature Review

A literature review was conducted to identify data cited in SPM research supporting stock management policy decision-making. The systematic literature review approach was selected to ensure that the literature identification process was transparent and replicable. Scopus was adopted as the main research database, and the search was limited to English language publications between 2008 and 2025 and examined article titles, abstracts, and keywords. Subjects irrelevant to the study area, such as medicine and chemistry, were excluded.

A broad review article search addressing spare parts or inventory and maintenance yielded 809 contributions. This was reduced to 361 contributions after excluding 16 obviously irrelevant subjects. Finally, 36 were selected after screening titles, keywords, and abstracts. The term “spare parts management” (SPM) was identified and selected as the overarching term for the review, resulting in the following search yielding 329 contributions: (“Spare parts management” OR “SPM”) AND (“Maintenance” OR “Maintain*”).

Additionally, ways of mentioning data utilization were discovered over a variety of searches, first with (“spare” AND “part*”) AND “management” AND (“data” OR “empirical”)), yielding 586 contributions, and second with (“spare” AND “part*” AND “management” AND (“criteria” OR “attribute*” OR “parameter*”)), yielding 303 contributions.

An advanced search was developed from the four keyword categories presented in

Table 1 as data, spare parts, maintenance, and decisions related to SPM.

Each keyword from each of the four categories was combined into a search, yielding 3510 contributions. Keywords and titles were screened to identify potentially overlooked research areas and contributions. A total of 60 contributions were deemed relevant for this study. Systematic SPM literature review articles were also consulted to guide this review.

3. Literature Review

SPM is a branch of inventory management, supporting maintenance, repair, and operations (MROs) through planning and controlling human-capital resources, materials, processes, spare parts, and information [

10,

22]. This literature review adopts SPM as the central concept for managing spare parts in equipment-intensive industries. The review objective is to identify data cited in the current SPM literature as supporting decision-making methodologies for spare parts availability decision-making.

The review defines spare parts availability decisions, outlines SPM decision-support methodologies, identifies relevant SPM knowledge areas and decision-makers, and synthesizes data applied across SPM studies and the integration of data spanning the SPM knowledge areas.

The literature review confirms the existence of data fragmentation between siloed SPM knowledge areas. Furthermore, it highlights that current research lacks integration of data from all knowledge areas. Only a few studies integrate data across all the identified SPM knowledge areas. This demonstrates a need to establish a coherent empirical data model that increases data integration across all SPM knowledge areas, thus bridging the data siloing gap to reduce data-gathering requirements in SPM decision-making and align industry with state-of-the-art data-support methodologies.

3.1. Spare Parts Availability Decisions in SPM

In SPM, spare parts availability planning is addressed through inventory control, which involves selecting stock management policies noted by Teixeira et al. [

5] as: null stock, single-item stock, multi-item stock, and just-in-time (JIT). The core of these decisions is whether and how a spare part should be stocked, ranging between no units, one and multiple units in stock, or relying on JIT supply.

If a spare part is to be stocked, the inventory control parameters are required, including the inventory type, re-ordering point (ROP), safety stock level, replenishment strategy, and review frequency [

23]. These decisions detail the part availability while balancing risks, demand variability, and stock-out, holding, and ordering costs.

3.2. Decision-Making Approaches and Methodologies in SPM

Since the 1960s, numerous methodologies have been proposed to address the inherent complexity of SPM derived from the unique characteristics of spare parts, resulting in low forecast ability [

12,

16]. High procurement, holding, and shortage costs and irregular demand mirror some of these characteristics [

5,

9,

23,

24]. The high consumption variability, the large number of spare parts in organizations, and the excessive volume of information to consider render SPM decision-making highly challenging [

5,

14,

15,

17]. Consequently, organizations continue to rely on simple methods and tacit knowledge [

4]. Roda et al. [

17] document that 71% of industry practitioners apply rule-of-thumb classification, while Cakmak and Guney [

4] highlight that simple methods, such as single-criterion ABC classification, remain dominant despite their limited data foundations.

Cavalieri et al. [

16] propose a five-phase framework as an SPM practice guideline, including part coding, part classification, part demand forecasting, stock management policy making, and policy testing and validation. Recent studies emphasize the classification and forecasting steps of the framework as the primary inventory control decision-support methodologies [

25,

26].

Despite the availability of a range of SPM decision-support methodologies, inadequate demand forecasts and policies remain major issues for several companies [

15,

27]. Only a few of the advanced forecasting models are empirically validated in industry contexts [

26]. In contrast, classification methodologies are widely tested through case studies but lack consensus on the data applied and parameter thresholds [

17,

18,

26]. Studies highlight a need for simple, empirically implementable models and the application of big data analytics in SPM [

15,

23].

3.3. Knowledge Areas and Decision-Makers in SPM

SPM decision-making in MRO organizations deviates from traditional manufacturing as it requires technical and maintenance expertise alongside the material departments [

16,

18]. Maintenance planning and inventory control are typically handled by separate departments with different objectives and limited data sharing and alignment [

1]. Linking historical and operational data across siloed organizational knowledge areas can create valuable insights and improve decision-making, but collecting and combining the data remain difficult due to the siloed objectives and data fragmentation [

5,

19,

28,

29,

30].

Several studies have organized SPM data into thematic knowledge areas, but terminology and areal data inclusion vary between studies, indicating a lack of alignment. Bacchetti and Saccani [

31] and Hu et al. [

32] identify three contextually similar areas with varying terminology and data: spare parts characteristics, spare parts demand, and supply chain factors. Tusar and Sarker [

33] and Van Horenbeek et al. [

2] emphasize maintenance, logistics, inventory, the asset area called systems or specifications, and other data. Roda et al. [

17] present the areas of usage characteristics, supply characteristics, inventory problems, and plant criticality.

These variations reflect a lack of alignment in categorization. Hu et al. [

32], Roda et al. [

17], and Bacchetti and Saccani [

31] emphasize spare parts characteristics, while Tusar and Sarker [

33] and Van Horenbeek et al. [

2] emphasize operational and maintainable asset factors. Demand data are inconsistently categorized under demand, supply, logistics, or other areas. These inconsistencies complicate cross-departmental data alignment and usage. From synthesizing these perspectives, the following six core SPM knowledge areas are derived:

Spare parts characteristics data.

Spare parts supply/logistics data.

Maintenance/demand data.

Inventory/stocking data.

Maintainable asset data (plant/system/equipment).

Costs and other data.

3.4. Data as a Decision-Support Basis in SPM

The SPM literature applies the terms criteria, factors, characteristics, and parameters as descriptors for decision-support data, and in this study, these are unified as data. To support SPM methodologies, researchers tend to document the database applied. For this study, 60 SPM contributions were reviewed, and their cited data fields were consolidated and mapped to the six knowledge areas. The identified data were compared with the data citation overviews of Bacchetti and Saccani [

31], Van Horenbeek et al. [

2], Roda et al. [

17], Hu et al. [

32], Ayu Nariswari et al. [

18], Bhalla et al. [

26], and Tusar and Sarker [

33] to consolidate the terminologies and contexts.

Data descriptions vary concerning terminology, detail level, and definition overlap. For instance, Cavalieri et al. [

16] is cited by both Bacchetti and Saccani [

31] and Roda et al. [

17], yet only the latter includes the stock-out cost and lead time. Criticality is often a proxy for cost or risk, and lead times are sometimes named supply characteristics. Furthermore, criticality varies, whereby maintenance practitioners associate it with equipment risks, while procurement and logistics practitioners associate it with stock-out or holding costs. Accordingly, criticality may be placed under knowledge area E, but it could also span areas A or D, as reflected by Bacchetti and Saccani [

31] and Roda et al. [

17]. These inconsistencies may limit study comparability and method transferability to practice.

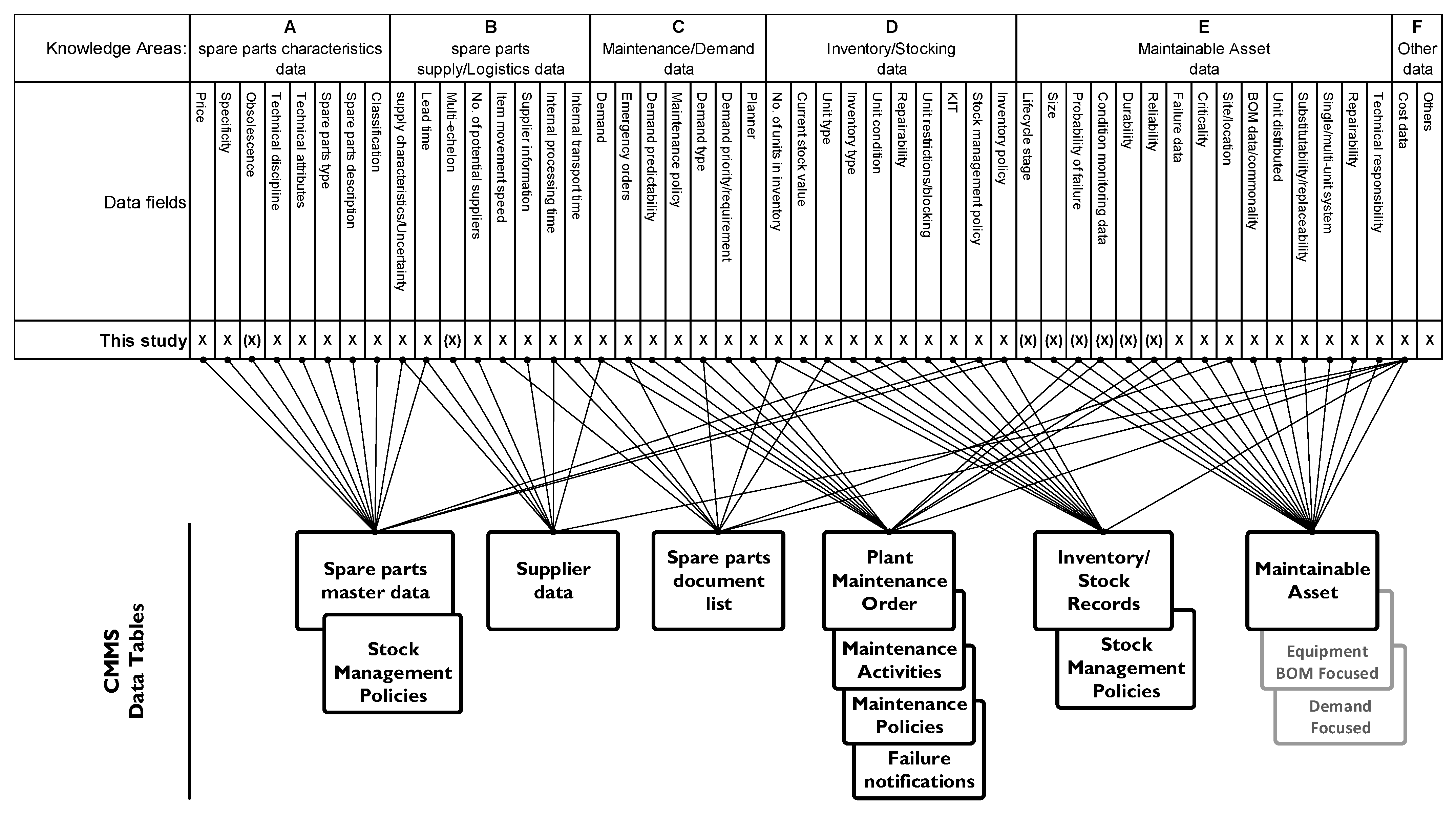

A total of 68 data field descriptions were consolidated into 30 fields through context similarities. Broad terms remain applied where separation was not possible. “Demand” covers demand, variability, volume, and usage value, while “Cost” encapsulates maintenance and inventory costs. Such consolidations formed the terms demand, cost data, no. of units in inventory, lead time, condition monitoring, site/location, specificity, and maintenance policy. The consolidated data fields are presented in

Table 2, organized by the six knowledge areas (A–F).

As

Table 2 shows, all investigated studies except Cakmak and Guney [

4], Ferdinand et al. [

42], and Schuh et al. [

52] lack data from at least one SPM knowledge area. As discussed by Ayu Nariswari et al. [

18] and Cavalieri et al. [

16], adequate stock management policy decisions require data and expertise from the finance, logistics, technical, and maintenance domains. As decision-makers depend on data from these knowledge areas, a lack of areal data coverage may affect decision-making.

Table 2 shows high variability in the data applied and knowledge area coverage across studies, and most studies lack data in at least one area. Thus, this review confirms the persistent data silo gap that recent SPM methodologies and data models lack data coverage across the relevant SPM knowledge areas.

The three studies by Cakmak and Guney [

4], Ferdinand et al. [

42], and Schuh et al. [

52] include data across all the knowledge areas, thereby forming broader databases, but are still limited in data field inclusion, leaving a potential for further database expansion. Additionally, barriers of assumptive data parameters and small empirical datasets limit empirical validation.

Schuh et al. [

52] present a proportional hazards model (PHM) to estimate inventory levels and component life in wind energy systems. The model integrates data across all six knowledge areas and emphasizes conditions monitoring and environmental data; however, it relies on probabilistic data, constant parameters, low-volume empirical datasets, and limited applicability for short-lifetime parts. Furthermore, the study emphasizes the need for including more data in future studies. Ferdinand et al. [

42] present a failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) algorithm optimizing inventories for offshore wind farm substations. The database includes data across all six knowledge areas, but it depends on deterministic and assumptive cost data, probabilistic failure data, and system documentation completeness. The study by Cakmak and Guney [

4] presents an aviation-specific neutrosophic fuzzy distance from average solution (EDAS) model integrating 13 of 30 defined data fields broadly covering all six knowledge areas. The database is found to be static due to expert criteria weighting. Furthermore, it is input sensitive, elaborated by the authors as an existing potential of the rank reversal phenomenon. This impacts the database if criteria or parts are added, removed, or adjusted, resulting in a rank reversal of the relative spare part ranking.

Of the knowledge areas shown in

Table 2, area E (Maintainable Asset) includes the most data fields, but few are frequently cited. The most frequently cited are lead time, demand, and cost data, appearing in over half of the reviewed studies. Approximately 30% of the studies apply price, maintenance policy, no. of units in inventory, inventory policy, and criticality. Overall, high variability and only a few commonly cited data fields are found. While research tends to emphasize lead time, demand, and cost data, the industry emphasizes equipment criticality and operational risks, as noted by Roda et al. [

17] and Ayu Nariswari et al. [

18] as a misalignment whereby recent SPM research does not reflect industry priorities.

The literature review highlights substantial limitations regarding data fragmentation across siloed organizational knowledge areas and IT systems, combined with excessive and growing volumes of parts and data to gather, all complicating decision-making [

1,

5,

10,

19]. Despite the numerous data-driven SPM methodologies, tacit knowledge and simple methods remain dominant and preferred in practice [

1,

4,

15].

The systematic review of 60 contributions confirms the data silo gap that SPM research is limited in data integration across the SPM knowledge areas. Thus, highlighting the need for a coherent empirical data model that bridges these silos by integrating data across all six SPM knowledge areas. The aim is for this model to help lower data-gathering efforts through automation and extend the empirical basis for data-driven SPM practice and the application of large data volumes.

4. Development of an Empirical Spare Parts Management Data Model

The literature review revealed a persistent research gap in SPM in terms of data siloing and limited knowledge area coverage. In SPM practice, this data silo fragmentation is evident through separation and scattering between the PM and MM modules in the CMMS. Combined with the inconsistencies between research and industry prioritizations of critical data fields, limited information sharing, and conflicting departmental objectives, these silos lead to fragmented decision-support databases that fail to integrate data across all six SPM knowledge areas. This produces large data-gathering requirements for decision-makers and data inconsistencies in SPM research.

This section develops an empirical SPM data model consolidating and integrating 50 data fields, establishing a coherent empirical decision-support database for decision-making. The model links spare parts with maintenance, logistics, inventory, and equipment data across the six identified SPM knowledge areas, thereby addressing the data siloing and fragmentation gap to reduce data-gathering requirements in SPM decision-making.

4.1. Data Fields Important in Case Company SPM Practices

Through semi-structured interviews and workshops with logistics, procurement, and maintenance personnel in the case company, the 20 data fields presented in

Table 3 were identified as essential for SPM decision-making, in addition to those identified in the literature review. This further underlines the misalignment between research and industry in the prioritization of critical data.

Although several additional data fields exist in the case company’s CMMS, these 20 fields were underlined as essential to SPM decision-making by case company SPM experts. Combined with the 30 data fields identified from the literature and presented in

Table 2, a total of 50 SPM-relevant data fields were consolidated. The eight fields of obsolescence, multi-echelon, lifecycle stage, size, probability of failure, condition monitoring data, durability, and reliability were not available in the case company’s CMMS but are integrated into the proposed empirical SPM data model.

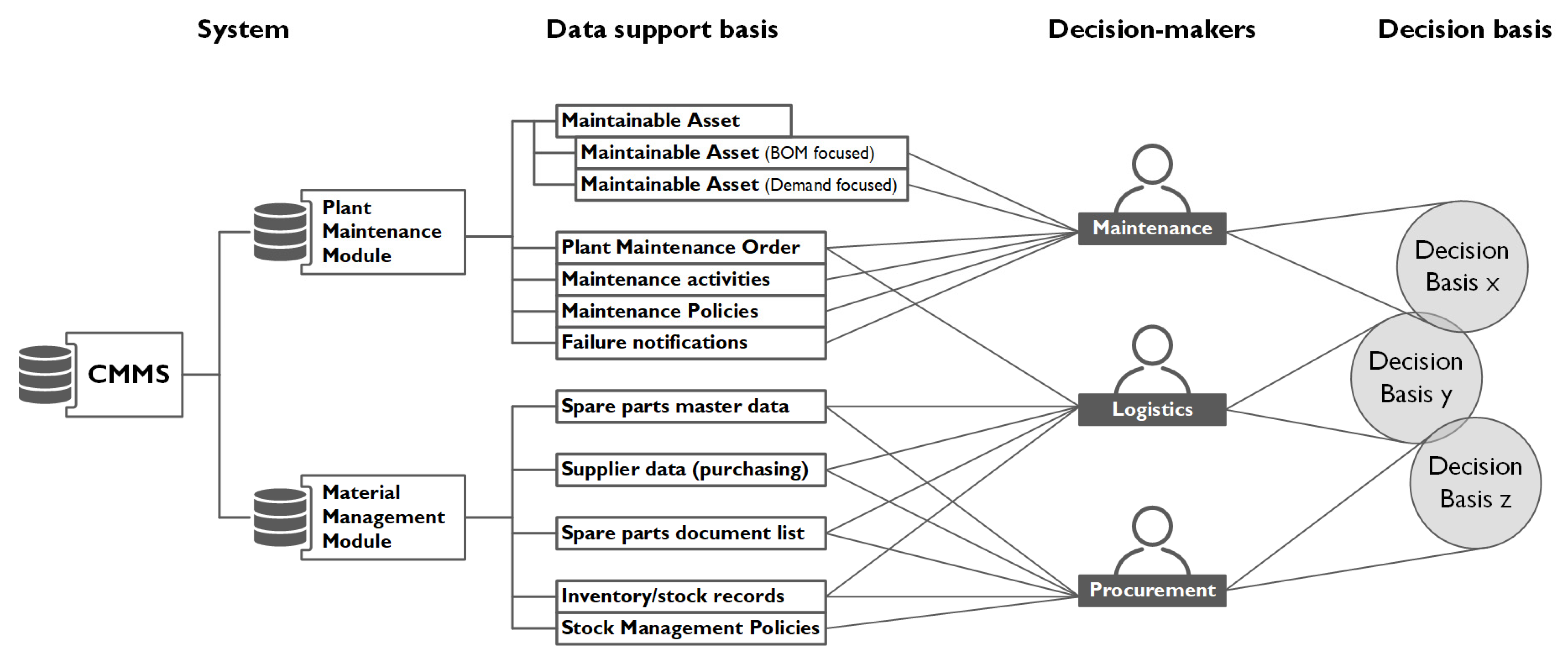

4.2. Locating Scattered Data in a CMMS

In the case company’s CMMS, maintenance demand and maintainable asset data are primarily stored in the PM module, while spare part characteristics, logistics, procurement, and inventory data are stored within the MM module. Despite partial overlaps, data remain scattered across multiple data tables, each containing fragments of the information needed for SPM decision-making. The PM module holds risk-, purpose-, and priority-related maintenance and equipment data, whereas the MM module holds availability- and supply-related spare parts data. This IT system data siloing reduces data trustworthiness and accessibility [

12], underlining the need for an integrated model that bridges the silos.

Figure 1 shows the 11 identified CMMS data tables linked to the 50 identified data fields, conceptually mapping the fragmented data across the IT system modules.

The spare parts master data table holds characteristics, supply/logistics, and inventory data as periodically updated dimensional data, such as average lead time, stock management policies, and part description. The supplier data table contains supply/logistics- and procurement-related data. The spare parts document list data table records part movements, quantities, costs, dates, and locations across multiple knowledge areas. The plant maintenance order, maintenance activities, maintenance policies, and failure notifications tables capture maintenance and maintainable asset data. The plant maintenance order table serves as the central maintenance summary table, while the other tables expand on specific details. The inventory/stocking data table holds records of inventory levels, part conditions, part types, and values. Stock management policies can also exist in this table. The maintainable asset data tables provide dimensional and periodically updated hierarchical system data on equipment and BOMs.

Several data fields appear in multiple tables due to differing predefined table purposes, indicating linkage potential through knowledge area overlaps. For instance, stock management policy and repairability data appear in both the inventory tables and the spare parts master data table. The document list data table is the only table holding data from the maintenance/demand, spare parts supply/logistics, and inventory/stocking knowledge areas, making it a potential interface for bridging these siloed areas.

The maintenance personnel navigate the PM module, while procurement and logistics personnel mainly navigate the MM module.

Figure 2 demonstrates the current decision-making practice patterns for accessing the identified data tables across the two CMMS modules. As each domain expert accesses and navigates the data differently, fragmented perspectives and domain-specific decision bases are produced. As described earlier, effective SPM decision-making requires integration of these differentiated perspectives and decision-support databases. As demonstrated in

Figure 2, the logistics domain holds a key role in bridging the CMMS modules and SPM knowledge areas due to its interface to both the procurement and maintenance decision bases and data sources. Leveraging logistics as a linking entity may enable integration of the two CMMS modules, improving data integration and usage across the knowledge area, which is essential for improving decision quality [

29,

85].

4.3. The Proposed Empirical SPM Data Model

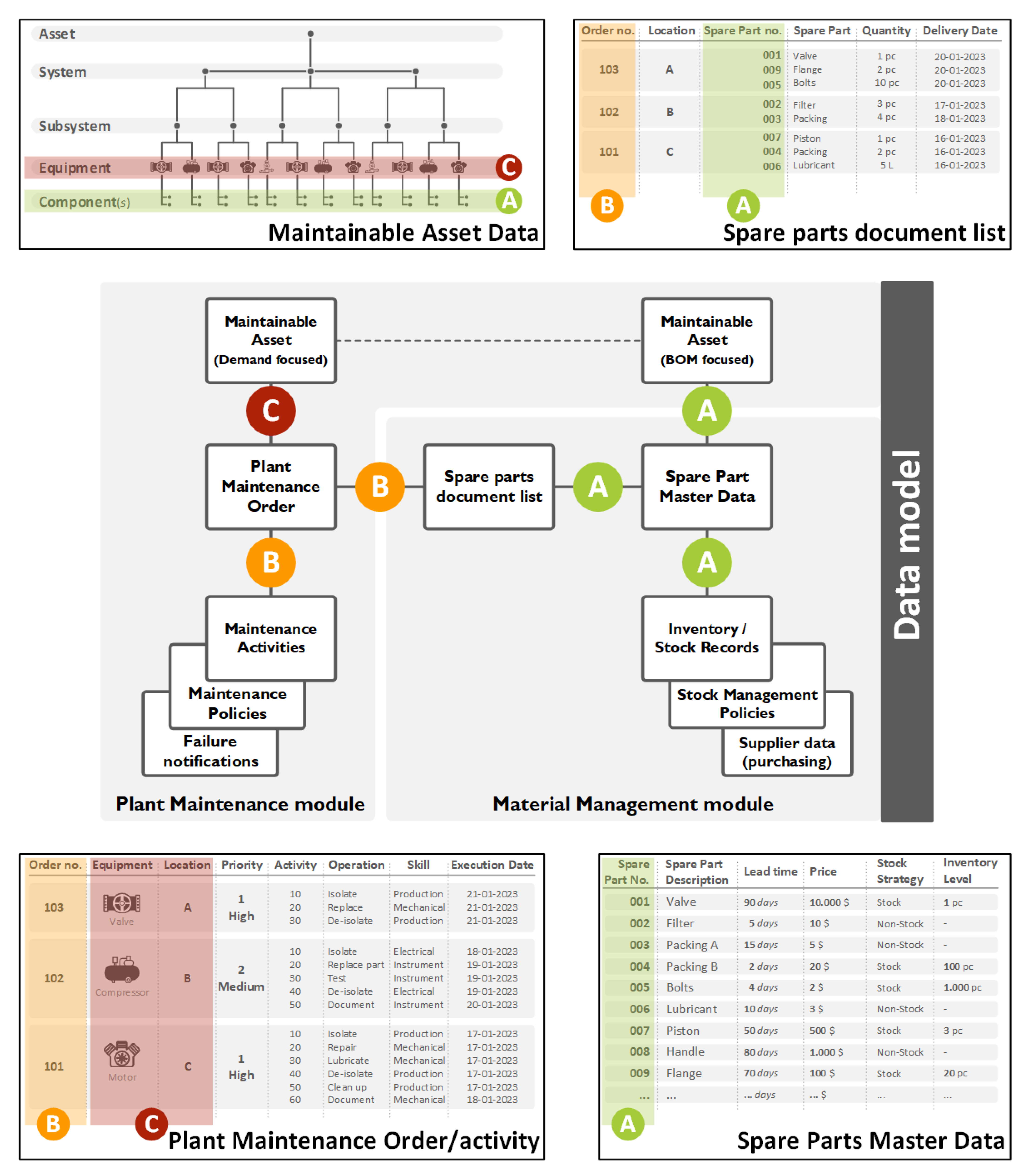

The logistics function enables a key linkage between procurement, maintenance, and the maintainable assets through the delivery of information connecting the maintenance job and the spare part procurement. The spare parts document list holds this information as a logistics-oriented data table, positioning logistics as the potential integrator for bridging the CMMS’s MM and PM modules. Building upon this and the investigation of the 11 identified CMMS data tables, the following three unique identifiers were defined to enable linkage between the CMMS modules, integrating data across the six knowledge areas and forming the proposed empirical SPM data model presented in

Figure 3:

Spare part number: a unique identifier coded in the MM module for each unique spare part added to the CMMS. In the model, this links spare parts to BOM parts, to spare parts in maintenance orders, to inventory, and to spare part movements.

Maintenance order number: a unique identifier created in the PM module for each maintenance order. In the model, this relates spare parts to maintenance and maintenance to failures and further maintenance details.

Equipment number: a unique identifier for each item of equipment in the maintainable asset. In the model, this links maintenance orders to the maintainable asset.

The model in

Figure 3 represents the conceptual linkage of the identified data table, demonstrated as the four exemplified core tables: spare parts master data, spare parts document list, plant maintenance order/activity, and maintainable asset data.

The maintenance order table aggregates related data, including order, equipment, location, order priority, maintenance activities, technical disciplines, and execution dates.

The maintainable asset data table represents a hierarchical decomposition of the physical systems and equipment as outlined by Hubka and Eder [

86], Sigsgaard et al. [

87], and Didriksen et al. [

88]. This hierarchy structure contextualizes the relationship between systems, equipment, and BOM parts while enabling a direct link between the spare parts and maintenance data. The spare parts master data table links spare parts to the BOM parts of each item of equipment, defining the spare part relationship to equipment independent of historical maintenance demand.

The spare parts document list links spare parts to maintenance orders and equipment location, capturing quantities, delivery dates, and part reservations. Two CMMS table variants exist, where one contains historical spare part movements, and the other contains historical and planned spare part reservations for maintenance orders. Combining both produces comprehensive traceability of past and future spare parts demand and consumption.

The spare parts master data table combines master data, inventory records, and stock management policies, serving as the central MM module table.

In principle, each spare part, maintenance order, and item of equipment has a unique identifier. While the equipment and the spare part numbers represent physical objects, the maintenance order number represents a service process. Conceptually, the former are static entities, while the maintenance order and part deliveries represent dynamic events that become history once processed. Linking these static entities through dynamic events provides a coherent overview of historical and current relationships between parts, equipment, and maintenance. Although the model is presented using the division of the PM and MM modules specific to the case company, its cross-knowledge area linking entities are considered universal. A core structural contribution of the model is the linkage of the static entities through the dynamic events using the three defined identifiers. Consequently, the model structure can be generalized to other industrial contexts where transactional maintenance and spare parts delivery history are recorded, regardless of the CMMS employed, as these entities are considered universal across systems.

Figure 3 demonstrates how the three identifiers collectively bridge the CMMS’s MM and PM modules. While links A and B connect data tables across the modules, link C provides context by connecting the maintainable asset to the maintenance and, thereby, spare parts. This linkage allows connection of the spare parts portfolio to the equipment portfolio, BOMs, and maintenance, while enabling tracking of where and how each spare part has been used, its equipment relation, and its potential application. The structural integrity of the model is reliant on the three defined identifiers. However, while data fragmentation in SPM is an existing challenge, this model offers resilience to incomplete and inaccurate data as it links data from multiple knowledge areas to mitigate imperfections in one area. The proposed empirical SPM data model is a database architecture that can be implemented as an analytical layer on top of CMMS. This layer acts as a read-only semantic model for structuring SPM data to bridge departmentally siloed IT system data. The model aims to enhance data availability of siloed data in decision-making without structurally changing the native CMMS schema.

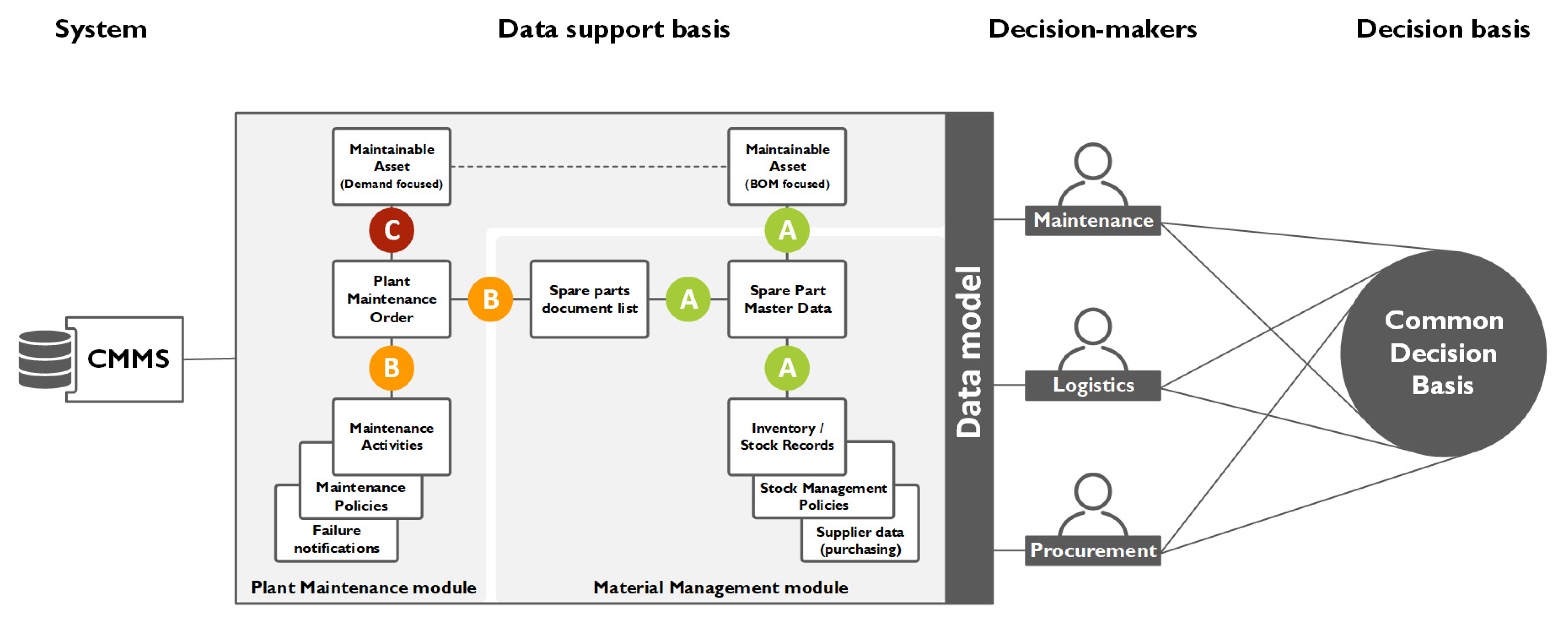

As

Figure 4 demonstrates, introducing the proposed empirical SPM data model linking the CMMS’s PM and MM modules establishes a common decision-support database across decision-makers and departmentally siloed knowledge areas. This integration improves SPM decision-making efficiency by reducing efforts spent on manual data gathering. This enables decision-makers to focus on analysis and decision-making rather than data gathering, while also enhancing decision traceability, transparency, and quality from having a coherent and shared data foundation.

By linking spare parts with maintenance, logistics, inventory, and equipment data across the CMMS’s PM and MM modules, the proposed empirical SPM data model directly addresses the identified research gap of fragmented data silos and limited knowledge area coverage in current SPM data models and methodologies. It achieves this by consolidating and integrating the 50 identified data fields from the literature and practice and extending the data foundation while ensuring data integration covering the span of the six identified SPM knowledge areas within a single model. Thus, it establishes a coherent empirical data model that bridges the data silos and lowers the required data-gathering efforts to reduce SPM decision-makers’ reliance on simple models and tacit knowledge while enhancing the potential of implementing advanced SPM methods in decision-making practice.

5. Case Study—Operationalization of the SPM Data Model

A longitudinal case study examines the effects of implementing the proposed empirical SPM data model within a major offshore oil and gas E&P company operating approximately 50 offshore plants in the North Sea. Despite the industry maturity, the company faces challenges, including increasing stock levels, ~50% stationary inventory, equipment and spare part obsolescence, and below 50% on-time part delivery compliance. Current practices rely on individual inventory reviews using simple and inconsistent methods.

This case study observed a spare part review project initiated by the maintenance department to reassess the repairability and stock management policies for 10,843 BOM-identified spare parts. Each spare part required six decisions for the repairability and the following stock management policies: null stock, single-item inventory, multi-item inventory, or JIT [

5]. The objective was to have experts manually assess the spare parts to enhance inventory reliability for BOM equipment and reduce excess inventory.

Three approaches and databases were observed as three sequential studies. Studies I and II reflect traditional company practices, while study III showcases the implementation of the proposed empirical SPM data model.

Table 4 presents the study contexts, including the approach, scope, scope stock value, stock value evolvement, study duration, decision basis data volume, data points per spare part, and data field coverage of knowledge areas.

Data points per spare part represent data points created from aggregations and variations in the combination of the data fields presented in

Figure 1. Data field coverage of knowledge areas indicates the number of data fields used from each SPM knowledge area presented in

Figure 1. Scope coverage of the total stock value was included as it indicates the maximum reachable stock impact at the time of decision-making.

Table 5 summarizes the outcomes of each study, including scope completion, stock value changes, the number of decision-makers enabled, the required full-time equivalents (FTEs) for project completion, the total decisions made, stock management policy adjustments, and decision quality.

Table 5 provides a comparative overview of the studies, demonstrating the effects of introducing the proposed empirical SPM data model and its derivative process transformational effects. Study III renders substantial improvements in project completion, decision-maker engagement, decision volume, resource efficiency, stock reduction potential, and decision quality. However, the distinction between the direct effects of the empirical SPM data model implementation and its derivative effects in the case company is to be noted. The direct effects concern the expansion of data availability for decision-making, specifically the increase in data fields, data points per spare part, and the data field coverage of knowledge areas. The derivative effects are considered the process transformation to a model-based approach, leading to the project completion, increased decision-maker engagement, higher decision volume, improved resource efficiency, stock reduction, and improved decision quality. The decision quality assessment was based on decision input compliance and completeness compared to company guidelines and the systemic CMMS requirements. This involves marking a spare part as having incompliant decisions if a decision is missing from the MRP coding, or if the decided MRP coding violates the company’s CMMS coding logic. FTEs were calculated as worked hours divided by 1776 h per year, equivalent to 37 h work weeks. The FTE baselines for studies I and II were derived based on the observed decision-making speed for the completed number of spare parts, extrapolated linearly to the remaining number of spare parts.

5.1. Study I—Document-Based and Bulk Decision Approach

In study I, the case company acquired two full-time spare parts specialists with a maintenance background to lead the project using a document-based and bulk decision-making approach on an equipment-oriented data basis. The document-based approach involved sending BOM-specific spare parts lists to equipment experts, while the bulk decision-making approach involved reviewing entire systems and conducting interviews with maintenance planners.

As presented in

Table 4, the decision basis included 22 data fields concretized to 49 data points per spare part, covering 39% of the knowledge areas. However, the decision basis was static and not updated after initial data gathering.

The project ran for six months before management terminated it due to high investment requirements, indication of stockpiling, limited progress, high resource requirements, and low decision-making transparency. While 53% of the scope was reported as completed, 26% included all required decisions. Of this 26%, ~4% were flagged as high investment risks by the company. Consequently, no decisions were implemented. As shown in

Table 5, the process yielded 7865 decisions, resulting in a 0.6% stock value increase (1.6% increase within scope stock value) and a 41% stock management policy renewal rate. Projected scope completion would have required 3.85 FTEs.

The equipment experts declined to use the static spare part lists due to data obsolescence and lack of data coverage. Post-review analysis showed blank decisions and revealed that bulk decisions applied at the system level often resulted in stockpiling and redundant stock investments.

5.2. Study II—Document-Based Approach

In study II, the project was re-initiated, leveraging internal maintenance resources. As presented in

Table 4, the decision basis was extended to 24 data fields represented by 54 data points per spare part, covering 45% of the knowledge areas. It was set to be periodically updated, and BOM-specific spare part lists were again sent to equipment experts. A project lead consolidated the final decision for management approval.

Despite the document rejections in study I, the same document-based approach continued. After five months, management terminated the project due to progress stagnation and limited engagement and impact. The process yielded completion of three lists within the first month, requiring 14 days of effort. Despite updated data and an expanded decision basis, the process throughput was limited by excessive workload, high data-gathering requirements, and issues regarding data redundancy. It was reported that data comprehension issues from data complexity limited daily review processing capacity to ~20 spare parts per day. Each decision-maker verified, re-gathered, and added CMMS data to make decisions, creating inconsistent and nontransparent decision bases. Thus, data redundancy occurred as lists became obsolete before decisions were made and returned, further contributing to overwhelming data volumes and gathering requirements.

As

Table 5 shows, 666 decisions were made, resulting in a 2% scope completion with a 1% lower decision quality than in study I. The decisions rendered an 84% required stock management policy renewal rate and a 0.1% stock value reduction (a 0.3% reduction within scope stock value). Project scope completion was projected to require 9.83 FTEs, which is a 156% resource requirement increase, substantiating the decision-maker’s disengagement.

5.3. Study III—Model-Based Approach with the Proposed SPM Data Model

In study III, the case company adopted a model-based approach using an operationalized version of the proposed empirical SPM data model. As in study II, the project relied on internal maintenance department resources. The decision-makers accessed a centralized and updated data model, enabling both bulk and individual spare parts reviews requiring limited filtering and searches.

As presented in

Table 4, the model extended the decision basis to 41 data fields, resulting in 84 data points per spare part and covering 87% of the knowledge areas. The decision-makers could filter, search, and review spare parts with updated data, allowing customized overviews. Each decision-maker applied their own approach according to their expertise while working from a shared decision basis. This increased data-gathering speed and improved decision-basis commonality across decision-makers.

The project ran for 11 months and engaged 32 decision-makers. Engagement increased due to the extended data foundation linking more technical expertise to spare parts through the BOM and historical demand data. The reduced data-gathering workload increased decision-maker engagement. Consequently, the scope of spare parts was distributed among more decision-makers, each with high specialization in the individual equipment and spare parts. This increased decision-maker engagement is considered a derivative process transformation effect enabled by the empirical SPM data model. Although these expert resources were available prior to study III, they could not be activated due to high barriers of data gathering requirements and the difficulty in relating the specific spare parts to the relevant decision-makers using the previously limited databases.

As presented in

Table 5, applying the proposed empirical SPM data model resulted in project completion. The actual decision time was 114 distinct calendar days, which accumulated a total workload of 222 decision-maker workdays, as multiple decision-makers worked on the distinct calendar days.

A total of 35,898 decisions were made with 95% decision quality, which was 4% and 5% higher than for studies I and II, respectively. Only 0.93 FTEs were required, yielding 76% and 91% efficiency improvements relative to studies I and II, respectively. Consequently, this efficiency gain is considered a process transformation effect from reducing data-gathering efforts and thereby enabling more decision-makers and higher decision-making speed. Furthermore, 56% of the spare parts required a renewed stock management policy, which was much less severe compared to the prior studies. Financially, the decision-making yielded a 15.1% stock value reduction (a 45% reduction within the scope stock value). The stock value reduction represents a management-approved potential. The decisions and corresponding reductions were formally signed by company management for the execution of the MRP update in the CMMS. This management approval effectuates the reduction, and the CMMS update triggers the organizational processes of stock liquidation and purchasing, thereby transforming potential reductions to realized reductions. By the time study III was completed, and prior to implementation, the stock value had risen by 9% over 22 months since project initiation. Implementation of the study III decisions would reverse this stock value trend, leading to a 6.1% net decrease.

Company management found the model-based decision-making approach transparent, trustworthy, and to have a conservative risk level. Thus, full implementation of the revised stock management policies and their resulting implications was approved. These results produced a strong interest in the continuous adaptation of the model-based approach and data model for future SPM practices.

Collectively, the three studies demonstrate that the model-based approach applying the proposed empirical SPM data model enabled completion of the spare parts review project with a lowered resource requirement, increased decision-maker engagement, decreased stock value, increased decision quality, and improved decision basis consistency and commonality across decision-makers. Lastly, data gathering and assessment efforts were drastically reduced, while integration of data across the six identified SPM knowledge areas was improved.

6. Discussion

This study addressed three research questions through a systematic literature review, exploratory research, prescriptive research, and a longitudinal case study.

The first research question examined what data are cited in spare parts management (SPM) research and applied in industry practices to inform stock management policy decisions. Fifty data fields were identified and deemed relevant by industry experts and SPM researchers contributing to SPM methodologies over the past 18 years. These data fields were scattered across 11 computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) tables between the plant maintenance (PM) and material management (MM) modules, highlighting the gap of data fragmentation and siloing across IT systems and departmental knowledge areas [

1,

5,

10,

17,

19].

The review further confirmed the gap by demonstrating that most SPM methodologies and data models do not integrate data across the full range of SPM knowledge areas. The effects of this data siloing gap are data inaccessibility and high data-gathering requirements, leading to decision-making challenges of time pressure, limited information comprehension, low-quality decisions, and decision base inconsistencies between decision-makers. Consequently, this reinforces the growing gap between theory and practice, whereby practitioners continue to rely on simple methods and tacit knowledge [

1,

4,

15]. Research advances toward increasingly complex computational models [

15], but without adequately addressing the silos and fragmentation issues that need consideration during model development [

1].

The second research question concerned how the identified data fields could be linked to form an empirical SPM data model integrating data across the span of relevant SPM knowledge areas. To address this, the study proposed an empirical SPM data model linking 50 validated data fields across the CMMS’s PM and MM modules. The data fields were identified and assessed through CMMS data table investigation, validated by a literature review, and further validated by logistics, procurement, and maintenance experts from the case company.

The resulting empirical SPM data model consolidated and integrated the 50 data fields by linking spare parts, maintenance, logistics, inventory, and equipment CMMS data covering data across the six SPM knowledge areas. The model formed a cross-domain decision foundation that ensured that the relevant data were gathered to support SPM decision-makers in allocating stock management policies.

The third research question explored the effects derived from implementing such an empirical data model in SPM practice. The longitudinal case study examined three different study cases observing stock management policy decision-making with three different approaches and databases. The study demonstrated that introducing the operationalized empirical SPM data model expanded the database and knowledge area coverage, leading to project completion with the process transformation effects of reducing resource requirements, improving decision quality, reducing stock value, enhancing decision basis commonality, and increasing decision-maker engagement and trust.

Collectively, the three studies revealed that applying the empirical SPM data model enabled a model-based approach that increased data accessibility, reduced data-gathering efforts, and enhanced transparency, collaboration, and traceability in decision-making. While full coverage of all potential SPM data fields cannot be claimed, the proposed empirical SPM data model integrated 50 data fields across six identified SPM knowledge areas, directly addressing the gap of data fragmentation and siloing across departmental knowledge areas and IT systems.

By addressing this gap and automating data gathering, the model provided a platform for further SPM research in an industry context. Researchers and practitioners can compare the identified data fields and tables with those in their own systems to evaluate or extend data integration across the span of SPM knowledge areas. While data fields and table naming conventions depend on the specific system or industry context, the model structure offers a generalization for integrating data from CMMS environments. The generalizability of the model is derived from the three universal identifiers, spare part number, maintenance order number, and equipment number, which are common entities across industries and CMMS. Although the proposed empirical SPM data model was developed and tested in the offshore oil and gas industry context, characterized by slow-moving inventory and high asset criticality, the structural logic of the model is perceived to be transferable to other operational contexts. This includes high-velocity industries such as automotive and consumer electronics, where Just-In-Time (JIT) strategies are predominant and warehousing is minimal. In such industries, maintenance and SPM remain critical, where maintenance orders are generated requiring spare parts for equipment maintenance. The spare parts document list type of data table remains an integrative entity where the universal identifiers link and bridge SPM knowledge areas, by capturing delivery information that connects maintenance jobs, resource transportation, and the spare part procurement spanning the logistics, procurement, and maintenance domains, extending beyond warehouse movements.

The literature review highlights the limitation that SPM studies lack data integration across the six SPM knowledge areas. The case study showed that when the proposed empirical SPM data model was introduced to decision-makers, the amount of data applied in the decision-making process doubled, while the decision-making was successfully completed, yielding increased decision quality and decision-maker engagement. This indicates a notable data availability improvement and an increased decision basis commonality across decision-makers. The model automated data gathering, enabling the decision-makers to focus their resources on decision-making. Such automation may improve the facilitation of continuous policy compliance tracking and support long-term policy alignment with the dynamics of spare parts characteristics.

6.1. Implications for Research and Industry

In terms of research, the empirical SPM data model offers a coherent data foundation that links spare parts, maintenance, logistics, inventory, and equipment data across the siloed CMMS PM and MM modules. It bridges the departmentally siloed knowledge areas and IT system silos by ensuring data coverage and linkage across all six SPM knowledge areas. Bridging this data siloing gap reduces data-gathering efforts through automation. The model enables the empirical testing of SPM methodologies with large data volumes and establishes a common structure for data gathering and comparing model database coverage of knowledge areas. While the proposed empirical SPM data model is considered a database architecture for descriptive analysis, its structure enables bridging siloed SPM knowledge areas, forming a prerequisite foundation upon which advanced data-driven models for predictive analysis can be developed and trained.

For the industry, the proposed model and case study demonstrate significant potential to reduce time and resource investments in preparing and maintaining the SPM decision-support database. The model facilitates scalable, data-driven decision-making, covering important data across SPM departments. The model may serve as a guide for practitioners to initiate modeling existing data for the future application of theoretical methodologies. By implementing the model and extending the decision basis to cover data across all knowledge areas, the case study showed derivative process transformation effects of increased decision quality, decision transparency, decision trust, and decision-maker engagement. Further, it showed economic gains such as stock value and FTE resource requirement reductions. Lastly, it reduced data-gathering efforts, allowing more time for decision-making.

6.2. Study Limitations and Future Research

This study is based on a single case company, and data availability may vary across organizations. Not all identified data fields were present in the case company’s CMMS, and cost data were aggregated into a single data field due to access policy limitations. However, the proposed empirical SPM data model is developed to integrate additional data if spare parts, maintenance orders, or equipment identifiers are available. The structural integrity of the model relies on the availability of the three defined identifiers in the dataset. While addressing the data fragmentation challenges in SPM, the model cannot solve the issues of unrecorded data. However, it shows resilience to incomplete and inaccurate data by enabling data triangulation through the linking of data across the span of SPM knowledge areas. In cases of data limitation, it includes a broader coverage of data fields for triangulation relative to those identified in the literature. In cases where empirical cost data are available or distributed between multiple knowledge areas, the model may require further adaptation.

Future research should explore variations in data field definitions, data terminologies, and knowledge area coverage across industries. It should also investigate the SPM decision basis commonality between MRO organizations. Further work may also concern assessing the model’s performance when implemented in diverse operational environments. The coherent data foundation serves to address the data fragmentation challenge, considered a barrier to advanced data-driven approaches. By bridging data silos, the model serves as a prerequisite foundation for supporting future studies involving advanced computational methodologies, such as the multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) technique noted by Torre et al. [

36].

7. Conclusions

This study proposed an empirical spare parts management (SPM) data model that integrates 50 data fields covering six SPM literature-identified knowledge areas.

The recent literature reflects a persistent gap in SPM research that data siloing and fragmentation in current IT systems and departmental knowledge areas challenge decision-making by excessive data-gathering requirements. This causes decision-makers to continue to rely on simple methods and tacit knowledge despite vast and increasing volumes of data and spare parts to consider. The systematic literature review of 60 SPM contributions confirmed this data siloing gap by demonstrating that recent SPM research lacks data integration and coverage across the span of SPM knowledge areas.

The proposed model addresses this gap by integrating 50 identified data fields across all the SPM knowledge areas while linking fragmented data between the computerized maintenance management system’s (CMMS’s) plant maintenance (PM) and material management (MM) modules. By linking spare parts, maintenance, logistics, inventory, and equipment data across the two CMMS modules, the model bridges the current IT system silos and departmentally siloed knowledge areas and establishes a coherent data foundation to support data-driven SPM decision-making.

The effects of implementing the model were examined through a longitudinal case study in a major offshore oil and gas company conducting a spare parts review project. The study demonstrated a 15.1% stock value reduction, 76–91% improvement rates in full-time equivalent (FTE) resources, and a 4–5% decision quality improvement as derivative process transformation effects enabled by the model implementation. The model implementation further entailed enhanced decision-making consistency, transparency, and trust, while enabling increased decision-maker engagement and an expanded decision basis with increased commonality. The proposed empirical SPM data model offers a coherent data foundation, reducing the data-gathering efforts through automation while integrating data covering the span of SPM knowledge areas.

Author Contributions

All authors of this study made equal contributions to the development or validation of the methodology presented in this article. Conceptualization, S.K.D., K.W.S. and N.H.M.; methodology, S.K.D., K.W.S., N.H.M. and C.B.J.; software, S.K.D. and K.W.S.; validation, S.K.D., K.W.S. and N.H.M.; formal analysis, S.K.D., K.W.S., N.H.M. and C.B.J.; investigation, S.K.D., K.W.S., N.H.M. and C.B.J.; resources, S.K.D., K.W.S. and N.H.M.; data curation, S.K.D. and K.W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.D., K.W.S., N.H.M. and C.B.J.; writing—review and editing, S.K.D., K.W.S., N.H.M. and C.B.J.; visualization, S.K.D.; supervision, K.W.S. and N.H.M.; project administration, S.K.D.; funding acquisition, N.H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Danish Offshore Technology Centre (DTU Offshore), grant number 109200, and the APC was funded by the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study included an analysis of empirical process data from the case company’s CMMS and qualitative interviews and workshops involving the case company’s employees. As no health or personal data were involved in this study, no ethics committee approval was required. The Danish Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Science Research Projects (Act No. 1338 of 1 September 2020) states that ethics committee approval is only required prior to Danish health research projects.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to case company confidentiality agreements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Danish Offshore Technology Centre (DTU Offshore) for funding and supporting this study. Furthermore, the authors would like to acknowledge the case company’s employees for their contributions to this study and for allowing the authors to study their work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOM | Bill of Material |

| BI | Business Intelligence |

| CMMS | Computerized Maintenance Management System |

| EDAS | Distance from Average Solution |

| FMEA | Failure Mode and Effects Analysis |

| E&P | Exploration and Production |

| FTE | Full-Time Equivalent |

| IT | Information Technology |

| JIT | Just-In-Time |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| MM | Materials Management |

| MRO | Maintenance, Repair, and Operations |

| MRP | Material Requirement Planning |

| MS | Microsoft |

| PHM | Proportional Hazards Model |

| PM | Plant Maintenance |

| ROP | Re-Ordering Points |

| SKU | Stock-Keeping Unit |

| SPIM | Spare Parts Inventory Management |

| SPM | Spare Parts Management |

References

- Scarf, P.; Syntetos, A.; Teunter, R. Joint Maintenance and Spare-Parts Inventory Models: A Review and Discussion of Practical Stock-Keeping Rules. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2023, 35, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horenbeek, A.; Buré, J.; Cattrysse, D.; Pintelon, L.; Vansteenwegen, P. Joint Maintenance and Inventory Optimization Systems: A Review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Jaarsveld, W.; Dekker, R. Spare Parts Stock Control for Redundant Systems Using Reliability Centered Maintenance Data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, E.; Guney, E. Spare Parts Inventory Classification Using Neutrosophic Fuzzy EDAS Method in the Aviation Industry. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.; Lopes, I.; Figueiredo, M. Spare Parts Stock Management: Classification and Policy Assignment. FME Trans. 2024, 52, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balugani, E.; Lolli, F.; Gamberini, R.; Rimini, B.; Regattieri, A. Clustering for Inventory Control Systems. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 1174–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, L.; Meissner, J. Spare Parts Inventory Management: New Evidence from Distribution Fitting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 273, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinçe, Ç.; Turrini, L.; Meissner, J. Intermittent Demand Forecasting for Spare Parts: A Critical Review. Omega 2021, 105, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.F.; Salsabila, N.Y.; Siswanto, N.; Kuo, P.H. A Two-Stage Genetic Algorithm for Joint Coordination of Spare Parts Inventory and Planned Maintenance under Uncertain Failures. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 130, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshrestha, N.; Agrawal, S.; Shree, D. Spare Parts Management in Industry 4.0 Era: A Literature Review. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2024, 30, 248–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, N.M.; Rajgopal, J.; Needy, K.L. Managing Nuclear Spare Parts Inventories: A Data Driven Methodology. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2014, 61, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez Hernandez, J.; Elizondo Rojas, M.D. Improving Spare Parts (MRO) Inventory Management Policies after COVID-19 Pandemic: A Lean Six Sigma 4.0 Project. TQM J. 2024, 36, 1627–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stip, J.; Van Houtum, G.J. On a Method to Improve Your Service BOMs within Spare Parts Management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.A.; Agrawal, N.; Agrawal, V. Winning in the Aftermarket. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetti, A.; Plebani, F.; Saccani, N.; Syntetos, A.A. Empirically-Driven Hierarchical Classification of Stock Keeping Units. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, S.; Garetti, M.; MacChi, M.; Pinto, R. A Decision-Making Framework for Managing Maintenance Spare Parts. Prod. Plan. Control 2008, 19, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, I.; Macchi, M.; Fumagalli, L.; Viveros, P. A Review of Multi-Criteria Classification of Spare Parts. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2014, 25, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayu Nariswari, N.P.; Bamford, D.; Dehe, B. Testing an AHP Model for Aircraft Spare Parts. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Das, T.; Mishra, M.R. A Study on Challenges and Opportunities in Master Data Management. Int. J. Database Manag. Syst. 2011, 3, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, C. Research Methods for Operations Management, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 0273701487. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C.; Lopes, I.; Figueiredo, M. Multi-Criteria Classification for Spare Parts Management: A Case Study. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, K.; Yuan, Y. Spare Parts Inventory Management: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Chakhar, S.; Siraj, S.; Labib, A. Spare Parts Classification in Industrial Manufacturing Using the Dominance-Based Rough Set Approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 262, 1136–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, J.E.; Syntetos, A.A. Spare Parts Management: A Review of Forecasting Research and Extensions. IMA J. Manag. Math. 2010, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, S.; Alfnes, E.; Hvolby, H.H.; Sgarbossa, F. Advances in Spare Parts Classification and Forecasting for Inventory Control: A Literature Review. IFAC-Pap. 2021, 54, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, C.A.; Craighead, C.W.; Hanna, J.B. Critical Challenges of Inventory Management in Service Parts Supply: A Delphi Study. Oper. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokrantz, J.; Skoogh, A.; Berlin, C.; Stahre, J. Maintenance in Digitalised Manufacturing: Delphi-Based Scenarios for 2030. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 191, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkiewicz, M.; Ho, M.T.W. Cleaning Historical Maintenance Work Order Data for Reliability Analysis. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2016, 22, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J. Product Lifecycle Management; Product Data; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 145–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, A.; Saccani, N. Spare Parts Classification and Demand Forecasting for Stock Control: Investigating the Gap between Research and Practice. Omega 2012, 40, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Boylan, J.E.; Chen, H.; Labib, A. OR in Spare Parts Management: A Review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 266, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusar, M.I.H.; Sarker, B.R. Spare Parts Control Strategies for Offshore Wind Farms: A Critical Review and Comparative Study. Wind Eng. 2022, 46, 1629–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benshimol, C.; Barron, Y. Stock-out Policies of a Spare-Parts Warehouse for a Multi-Item Repairable System. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 9748–9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Ishizaka, A.; Babai, M.Z. Enhancing Multi-Criteria Inventory Classification: Resolving Boundary Issues with VIKOR-Fuzzy Sorting. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 281, 109526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, N.M.M.; Salomon, V.A.P.; Florek-Paszkowska, A.K. Multi-Criteria Classification of Spare Parts in the Steel Industry. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2025, 22, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farizal; Taurina, Z.; Endrianto, E.; Nurcahyo, R.; Yassierli. Power Plant Spare Parts Inventory Determination Using Modified Multi-Criteria Classification and the Semi-Delphi Methods. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 11313–11332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, L.R.; Conceição, S.V.; Rodrigues, L.F.; de Freitas Almeida, J.F.; Affonso, T.B. Spare Parts Inventory Management: A New Hybrid Approach. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 40–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auweraer, S.; Boute, R.N.; Syntetos, A.A. Forecasting Spare Part Demand with Installed Base Information: A Review. Int. J. Forecast. 2019, 35, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelo, N.A.; Heyns, P.S.; Wannenburg, J. Forecasting Spare Parts Demand Using Condition Monitoring Information. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2019, 26, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gao, W.; Yang, T.; Guo, S. Opportunistic Maintenance Strategy for Wind Turbines Considering Weather Conditions and Spare Parts Inventory Management. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinand, R.; Monti, A.; Labusch, K. Determining Spare Part Inventory for Offshore Wind Farm Substations Based on FMEA Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe), Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 21–25 October 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Fu, L.; Yang, Q. Optimization on Management Strategies for Spare Parts Inventories of Wind Turbine Components. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 8th Annual International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER), Tianjin, China, 19–23 July 2018; pp. 1472–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Arvesen, A.; Luderer, G.; Pehl, M.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Hertwich, E.G. Deriving Life Cycle Assessment Coefficients for Application in Integrated Assessment Modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 99, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.D.F.; Maganha, I.; Magalhães, V.S.M.; Almeida, M. A Multicriteria Decision Framework for the Management of Maintenance Spares—A Case Study. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Lolli, F.; Balugani, E.; Cavallieri, R.; Gamberini, R. DEASort: Assigning Items with Data Envelopment Analysis in ABC Classes. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 199, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, U.C.; Sarmah, S.P. Joint Replenishment of Associated Spare Parts Using Clustering Approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 2535–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahane, M.; Sahnoun, M.; Bettayeb, B.; Baudry, D.; Boudhar, H. Impact of Spare Parts Remanufacturing on the Operation and Maintenance Performance of Offshore Wind Turbines: A Multi-Agent Approach. J. Intell. Manuf. 2017, 28, 1531–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Joint Optimization of Preventive Maintenance and Spare Parts Inventory with Appointment Policy. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 3493687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, C.L.P.; van Dalen, J.; van der Laan, E.A. Exploiting Elapsed Time for Managing Intermittent Demand for Spare Parts. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 258, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykasoğlu, A.; Subulan, K.; Karaslan, F.S. A New Fuzzy Linear Assignment Method for Multi-Attribute Decision Making with an Application to Spare Parts Inventory Classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 42, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, P.; Schneider, D.; Funke, L.; Tracht, K. Cost-Optimal Spare Parts Inventory Planning for Wind Energy Systems. Logist. Res. 2015, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, J.; Kopf, R.; Schneider, J.; Lanza, G. Criticality Analysis of Spare Parts Management: A Multi-Criteria Classification Regarding a Cross-Plant Central Warehouse Strategy. Prod. Eng. 2015, 9, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, S.P.; Moharana, U.C. Multi-Criteria Classification of Spare Parts Inventories—A Web Based Approach. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2015, 21, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, J.R.D.; Mesquita, M.A.D. Demand Forecasting and Inventory Control: A Simulation Study on Automotive Spare Parts. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 161, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, F.; Ishizaka, A.; Gamberini, R. New AHP-Based Approaches for Multi-Criteria Inventory Classification. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 156, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengu, D.; Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, M.Z. Spare Parts Management: Linking Distributional Assumptions to Demand Classification. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 235, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellingrath, B.; Cordes, A.-K. Conceptual Approach for Integrating Condition Monitoring Information and Spare Parts Forecasting Methods. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2014, 2, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracht, K.; Westerholt, J.; Schuh, P. Spare Parts Planning for Offshore Wind Turbines Subject to Restrictive Maintenance Conditions. Procedia CIRP 2013, 7, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinecke, G.; Syntetos, A.A.; Wang, W. Forecasting-Based SKU Classification. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, R.; Pinçe, Ç.; Zuidwijk, R.; Jalil, M.N. On the Use of Installed Base Information for Spare Parts Logistics: A Review of Ideas and Industry Practice. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 143, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaers, A.; Baets, H.; Pintelon, L.; Waeyenbergh, G. Criticality Classification of Spare Parts: A Case Study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.-R.; Wang, L.; He, J. A Novel Approach for Evaluating Control Criticality of Spare Parts Using Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation and GRA. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2012, 14, 392–401. [Google Scholar]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, M.Z.; Altay, N. On the Demand Distributions of Spare Parts. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 2101–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, T.; Shanmugarajan, N.; Wahab, M.I.M. Classification of Critical Spares for Aircraft Maintenance. In Proceedings of the ICSSSM11, Tianjin, China, 25–27 June 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi-Vencheh, A.; Mohamadghasemi, A. A Fuzzy AHP-DEA Approach for Multiple Criteria ABC Inventory Classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 3346–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Dowlatshahi, S. A Rule-Based Multi-Criteria Approach to Inventory Classification. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 7107–7126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chu, J.; Mao, W. A Condition-Based Replacement and Spare Provisioning Policy for Deteriorating Systems with Uncertain Deterioration to Failure. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 194, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, F.; Saccani, N. Managing the After-Sales Logistic Network–a Simulation Study. Prod. Plan. Control 2009, 20, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Keyes, M.; Babai, M.Z. Demand Categorisation in a European Spare Parts Logistics Network. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2009, 29, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-W.; Liang, G.-S.; Liao, C.-T. Controlling Inventory by Combining ABC Analysis and Fuzzy Classification. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2008, 55, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Yue, C.; Xie, J. Joint Optimization of Age Replacement and Spare Ordering Policy Based on Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security, Suzhou, China, 13–17 December 2008; Volume 1, pp. 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.; Bagajewicz, M. Optimization of Preventive Maintenance Scheduling in Processing Plants. In Proceedings of the Computer Aided Chemical Engineering, Lyon, France, 1–4 June 2008; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 25, pp. 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Cakir, O.; Canbolat, M.S. A Web-Based Decision Support System for Multi-Criteria Inventory Classification Using Fuzzy AHP Methodology. Expert Syst. Appl. 2008, 35, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwany, A.H.; Gebraeel, N.Z. Sensor-Driven Prognostic Models for Equipment Replacement and Spare Parts Inventory. IIE Trans. 2008, 40, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.Q.; Brammer, C.; Bagajewicz, M. New Tool for the Evaluation of the Scheduling of Preventive Maintenance for Chemical Process Plants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 1910–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chu, J.; Mao, W. A Condition-Based Order-Replacement Policy for a Single-Unit System. Appl. Math. Model. 2008, 32, 2274–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, H. Joint Optimization of Condition-Based Preventive Maintenance and Spare Ordering Policy. In Proceedings of the 2008 4th International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Mobile Computing, Dalian, China, 12–14 October 2008; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]