Extended Realityin Construction 4.0: A Systematic Review of Applications, Implementation Barriers, and Research Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the main applications of XR in the construction industry?

- RQ2: Which XR technologies are most frequently used?

- RQ3: What devices and platforms are commonly adopted for XR implementation?

- RQ4: What software engines support XR applications in construction?

- RQ5: What are the main barriers hindering XR adoption in real-world construction settings?

2. Literature Background

2.1. Extended Reality and BIM in Construction 4.0

2.2. XR Technologies and Devices in the AEC Sector

2.3. Prior Reviews on Construction 4.0 and XR in Construction

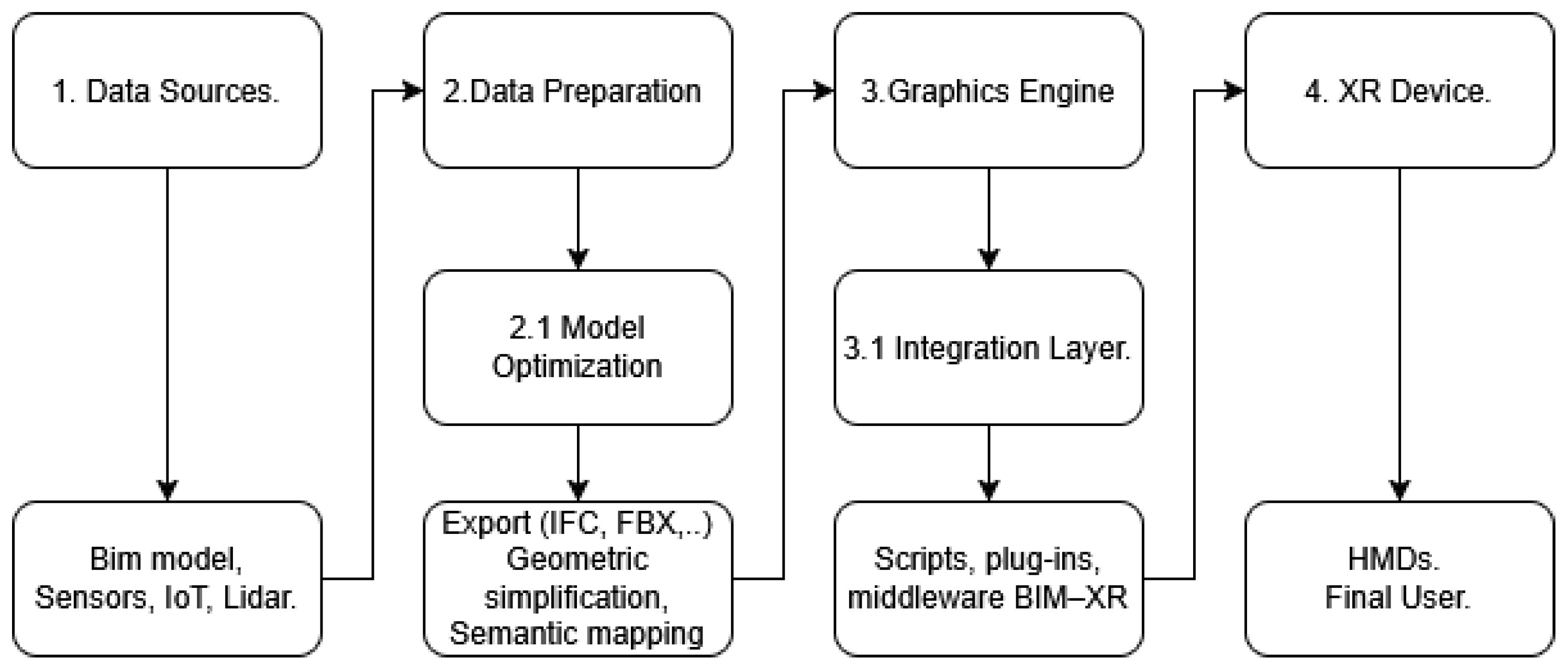

2.4. BIM-to-XR Workflows and Interoperability Challenges

3. Study Methodology

3.1. Bibliometric Review Methodology

3.2. Systematic Review

3.2.1. Eligibility Criteria

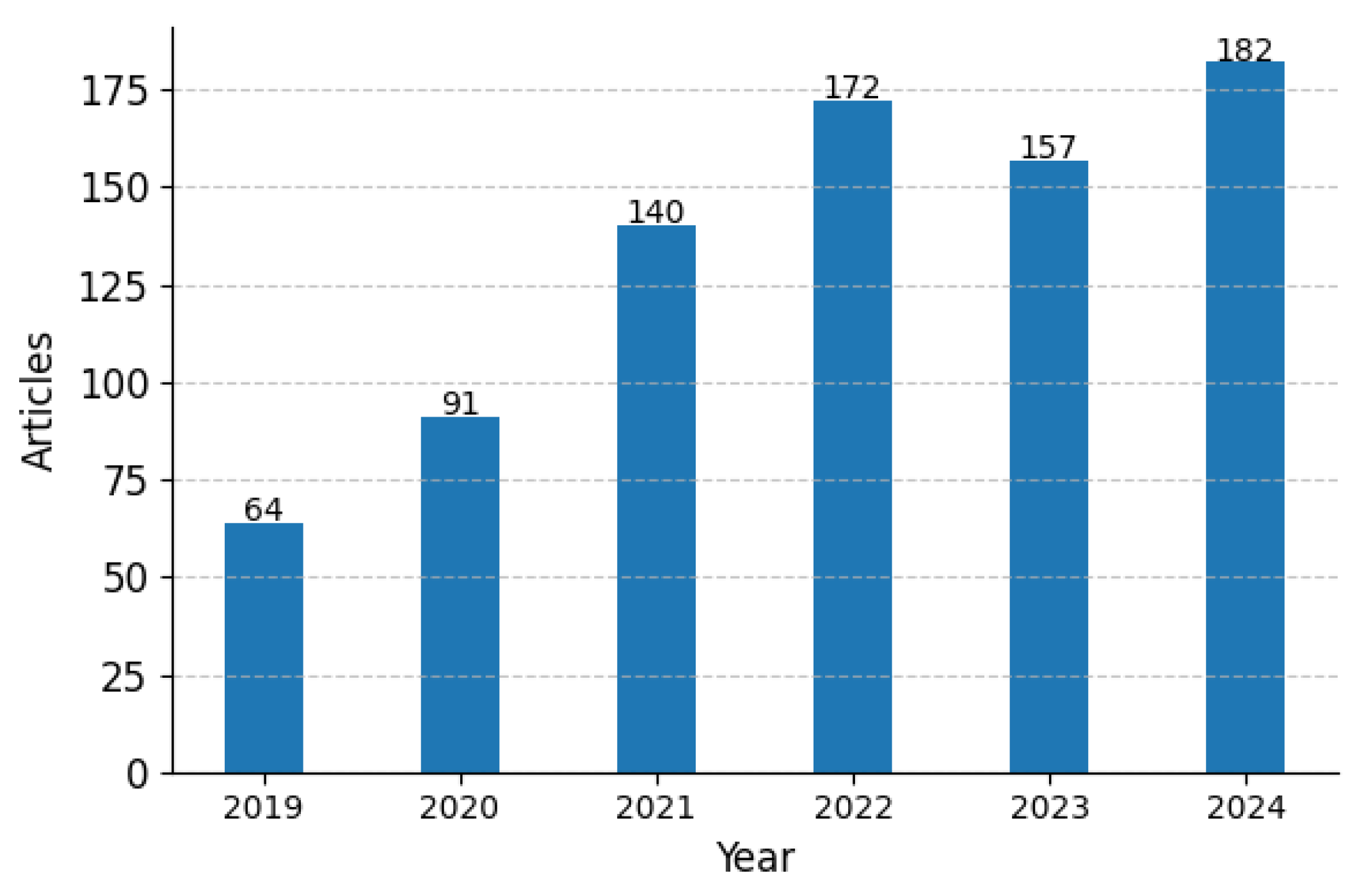

3.2.2. Search Strategy

3.2.3. Data Collection Process

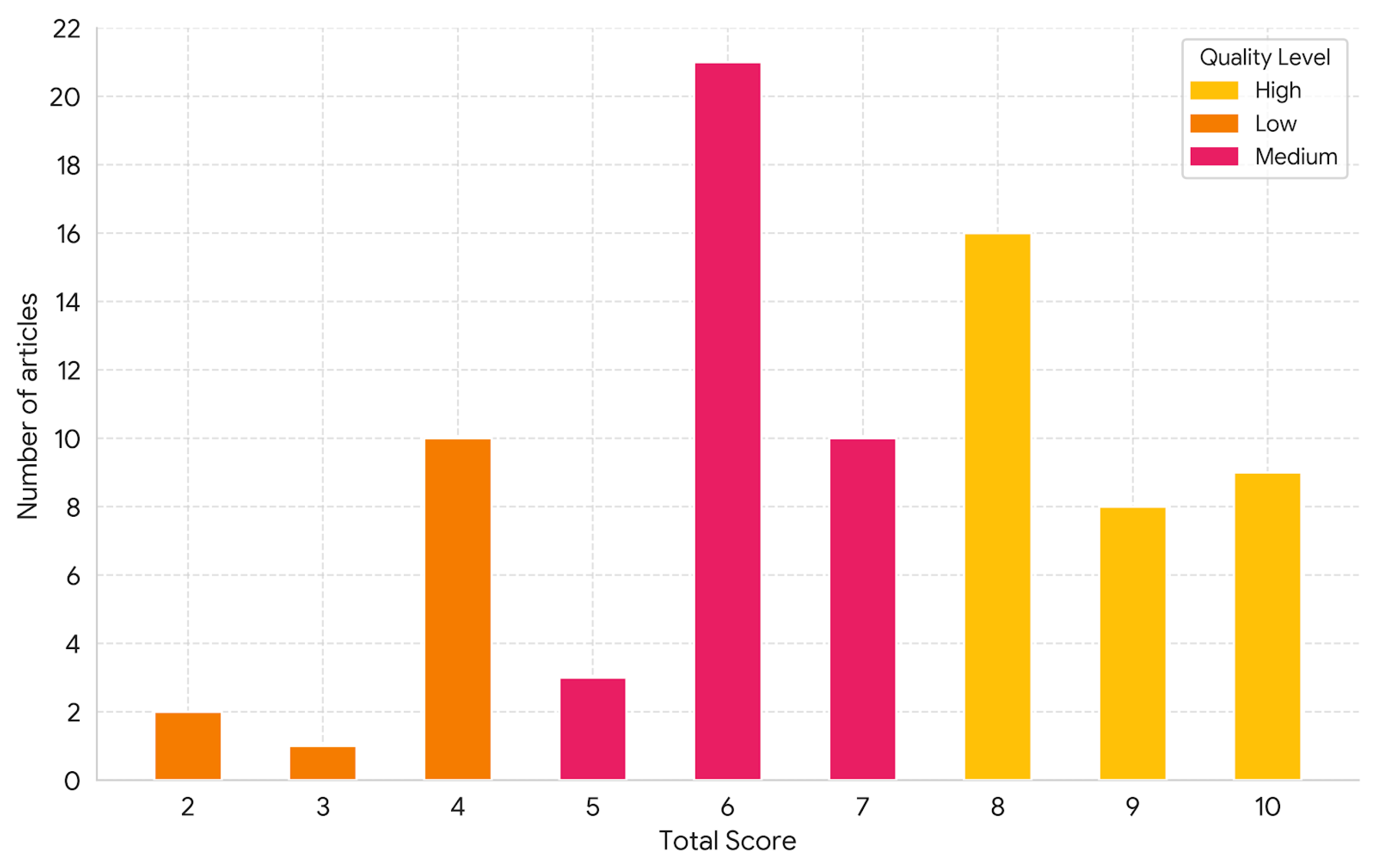

3.2.4. Study Quality Appraisal, Risk of Bias, and Synthesis Method

4. Results

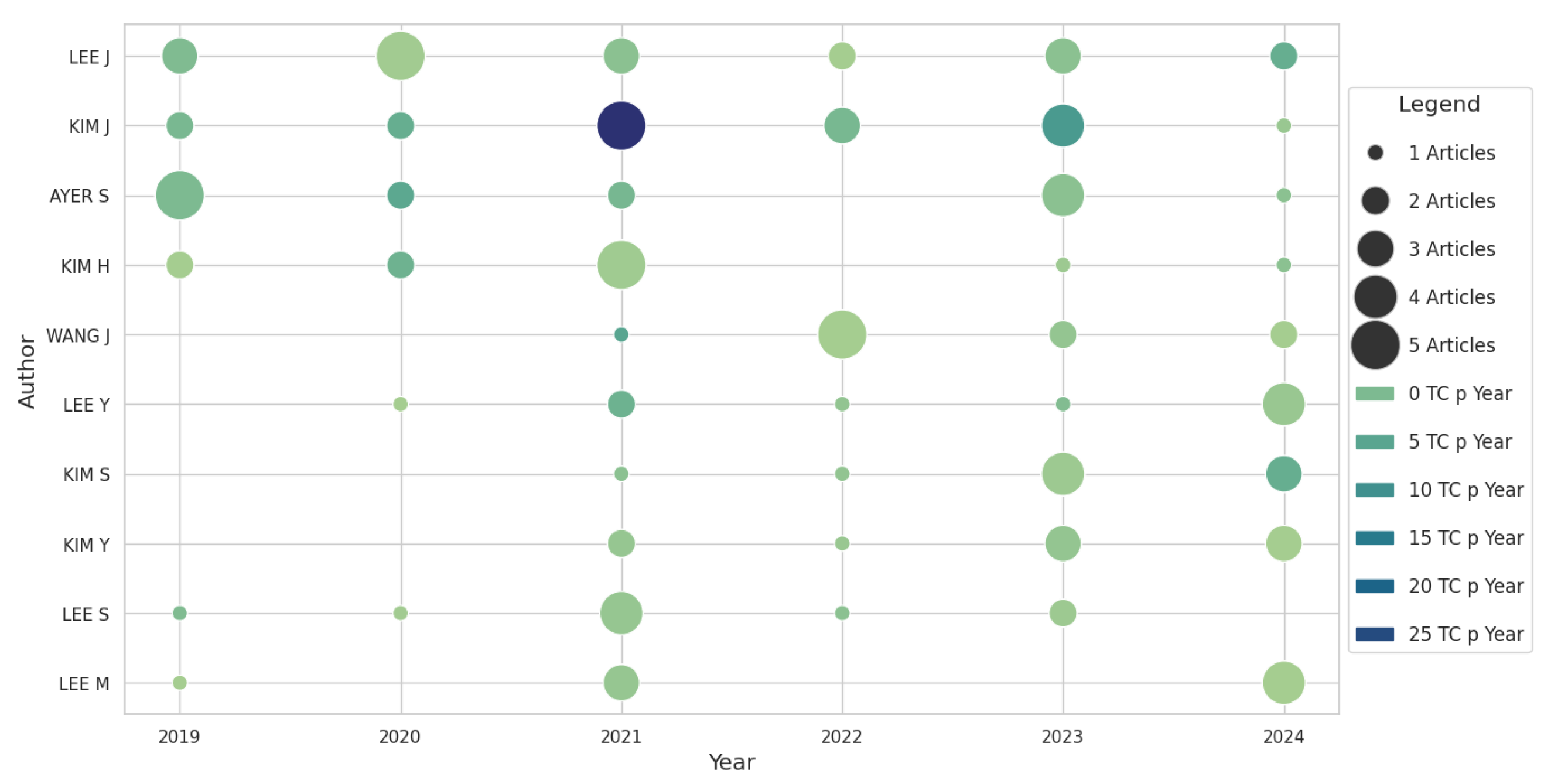

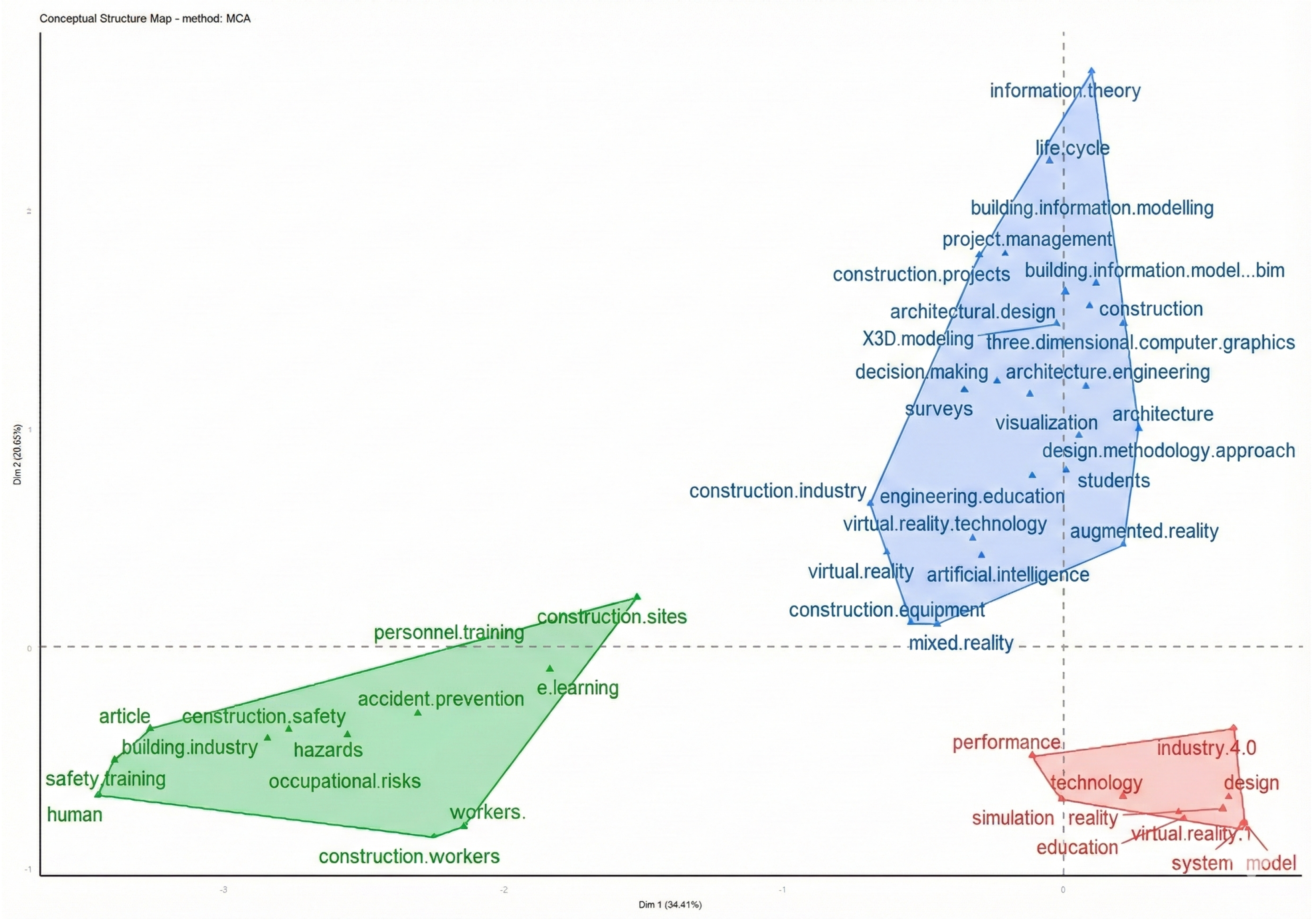

4.1. Bibliometric Review

4.2. Systematic Review Results

4.2.1. RQ1—Main Application Areas of XR in Construction

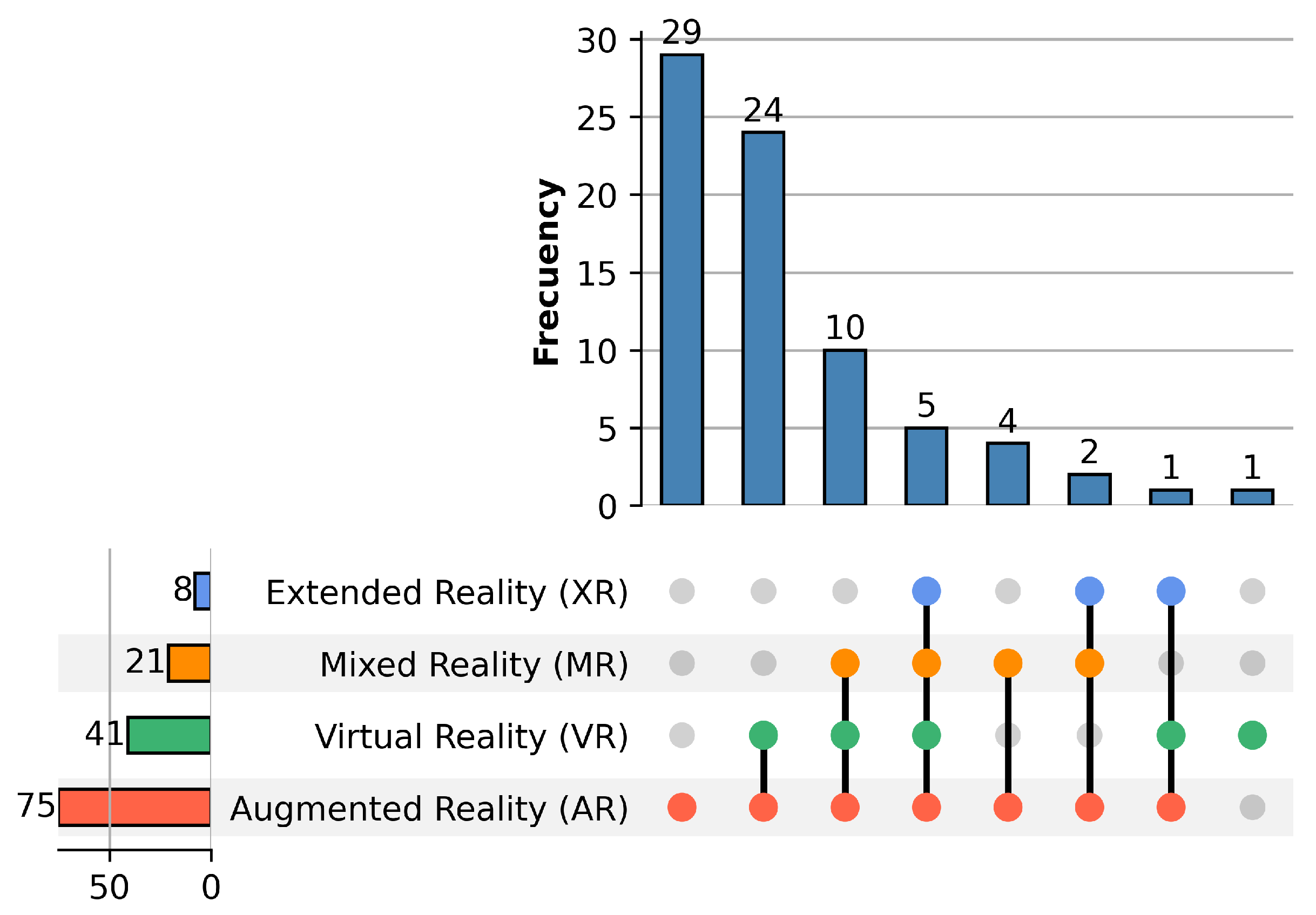

4.2.2. RQ2—XR Technology Types

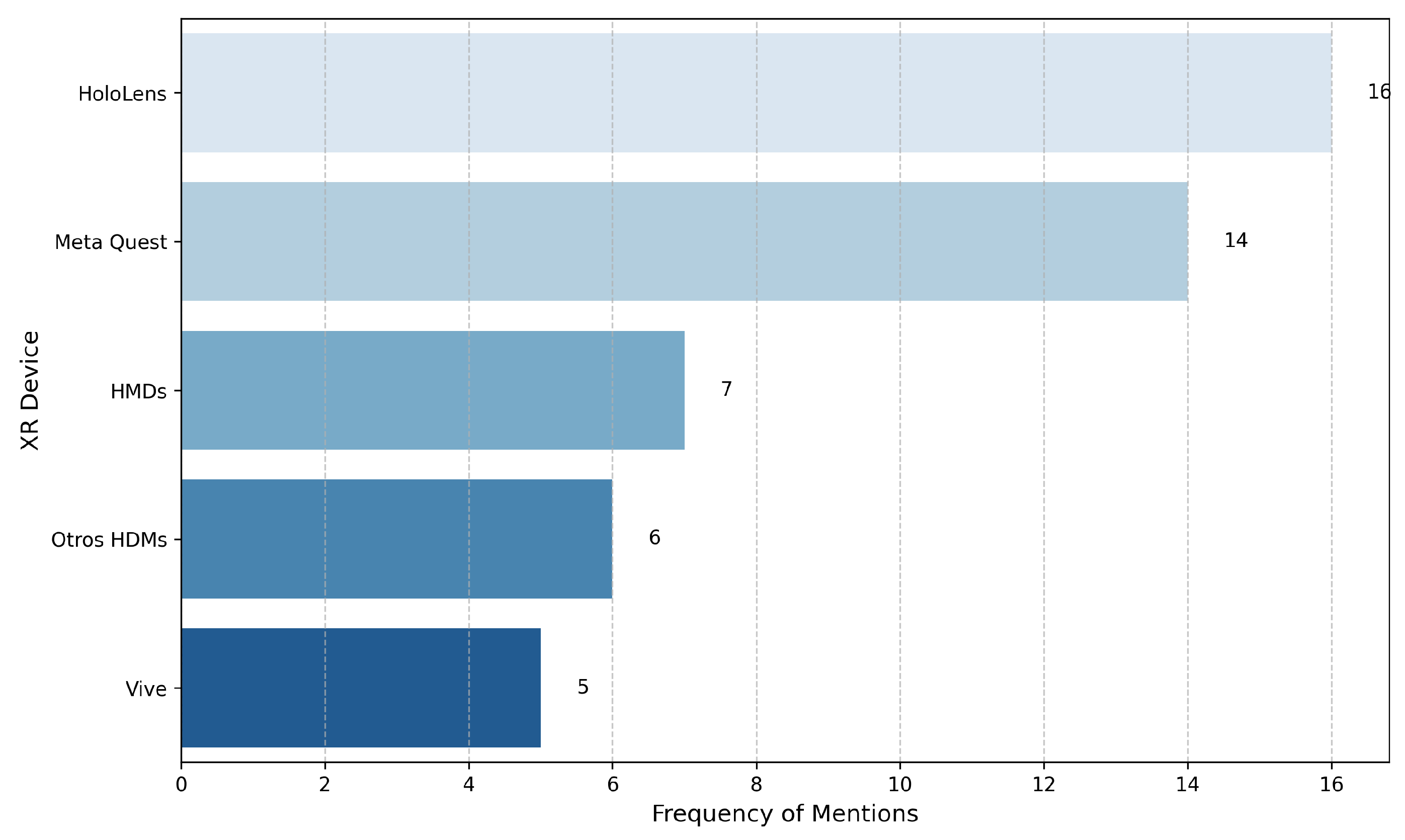

4.2.3. RQ3—XR Devices

4.2.4. RQ4—Graphics Engines

4.2.5. RQ5—Implementation Barriers

5. Discussion

5.1. Applications, Technologies, and the XR Ecosystem (RQ1–RQ4)

5.2. Implementation Barriers and XR Maturity (RQ5)

5.3. Implications for Practice and Comparison with Other Sectors

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Ref. | Obj. | Meth. | Res. | Appl. | XR Rel. | Total | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [76] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [44] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [40] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [82] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [88] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [62] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [78] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [73] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [34] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | High |

| [85] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | High |

| [10] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 9 | High |

| [87] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 | High |

| [47] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 | High |

| [19] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 | High |

| [35] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | High |

| [61] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | High |

| [29] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | High |

| [95] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [74] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [96] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [41] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [89] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 | High |

| [27] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [97] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [64] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [37] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [68] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | High |

| [31] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 | High |

| [60] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | High |

| [45] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | High |

| Ref. | Obj. | Meth. | Res. | Appl. | XR Rel. | Total | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Medium |

| [11] | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Medium |

| [51] | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Medium |

| [26] | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Medium |

| [75] | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | Medium |

| [71] | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | Medium |

| [50] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | Medium |

| [52] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | Medium |

| [57] | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | Medium |

| [39] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | Medium |

| [79] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [98] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [86] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | Medium |

| [77] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [53] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [59] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Medium |

| [36] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [42] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [30] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | Medium |

| [99] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | Medium |

| [100] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [38] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [43] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | Medium |

| [63] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [71] | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [34] | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [47] | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [58] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 | Medium |

| [80] | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | Medium |

| [84] | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | Medium |

| [69] | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | Medium |

References

- Balasubramanian, S.; Shukla, V.; Islam, N.; Manghat, S. Construction industry 4.0 and sustainability: An enabling framework. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Guo, F. Towards sustainable development through the perspective of construction 4.0: Systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Buildings 2022, 12, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabidin, N.S.; Belayutham, S.; Ibrahim, C.K.I.C. A bibliometric and scientometric mapping of industry 4.0 in construction. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2020, 25, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Robledo, L.A.; Hernández-Uribe, O.; Reta, C.; Cantoral-Ceballos, J.A. Extended reality applications in industry 4.0.—A systematic literature review. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 73, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehsalehi, S.; Hadavi, A.; Huang, J.C. From bim to extended reality in AEC industry. Autom. Constr. 2020, 116, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehsalehi, S.; Hadavi, A.; Huang, J.C. Virtual reality for design and construction education environment. In Proceedings of the Architectural Engineering National Conference 2019, Tysons, VA, USA, 3–6 April 2019; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begić, H.; Galić, M. A systematic review of construction 4.0 in the context of the bim 4.0 Premise. Buildings 2021, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.P.; Chen, K.; Chen, W. State-of-the-art review on mixed reality applications in the aeco Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontier, J.C.; Wong, P.S.; Teo, P. Towards the implementation of immersive technology in construction—A swot analysis. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.O.; Nnaji, C.; Okoro, C. Immersive technology implementation in the construction industry: Modeling paths of risk. Buildings 2022, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Razkenari, M.; Li, J.; Costin, A.; Kibert, C.; Qian, S. Investigating u.s. industry practitioners’ perspectives towards the adoption of emerging technologies in industrialized construction. Buildings 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekan, A.; Clinton, A.; Stella, E.; Moses, E.; Biodun, O. Construction 4.0 application: Industry 4.0, internet of things and lean construction tools’ application in quality management system of residential building projects. Buildings 2022, 12, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F. The evolution of interactivity, immersion and interoperability in hbim: Digital model uses, vr and ar for built cultural heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Demian, P.; Osmani, M. Immersive technology and building information modeling (bim) for sustainable smart cities. Buildings 2024, 14, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, P.B.; Rajan, A.J. Smart Manufacturing Technologies for Industry 4.0; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Klotz, E.; Newman, S.T. Intelligent manufacturing in the context of industry 4.0: A review. Engineering 2017, 3, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, M.; Royan, E.N.J.G.; Ramaswamy, G.; Rajendran, M.; Vadivelu, V. Fourth industrial revolution. In Integration of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering with IOT; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 41–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kora, H.; Beluli, R. Industrial revolution 4.0 and its impact on the evolution of the firm’s organization and management. Intercult. Commun. 2022, 7, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Shafiq, M.T.; Al Jassmi, H. Improving construction safety with virtual-design construction technologies—A review. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassereddine, H.; Hanna, A.S.; Veeramani, D.; Lotfallah, W. Augmented reality in the construction industry: Use-cases, benefits, obstacles, and future trends. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 730094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, M.U.; Pradel, P.; Sinclair, M.; Bibb, R. A bibliometric analysis of research in design for additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimo Aria, C.C. Bibliometrix: Una herramienta r para el análisis integral de mapas científicos. Rev. Inf. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software survey: Vosviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2009, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Muñoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M.J. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-year review. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración prisma 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. EspañOla Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asmar, P.G.; Chalhoub, J.; Ayer, S.K.; Abdallah, A.S. Contextualizing benefits and limitations reported for augmented reality in construction research. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 720–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, S.Y. Implementing virtual reality–building information modeling in the construction management curriculum. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2020, 27, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, T.; Ichwanto, M.A.; Muhammad, D.F. vr-Based Learning Media of Earthquake-Resistant Construction for Civil Engineering Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, H.; Pelikan, G.; Schranz, C. Augmented reality in aec Education: A Case Study. Buildings 2022, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzarrad, A.; Miller, M.; Chowdhury, S.; McIntosh, J.; Perry, T.; Shen, R. Harnessing virtual reality to mitigate heat-related injuries in construction projects. Civileng 2023, 4, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, S. Concept of using the bim technology to support the defect management process. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2021, 67, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, A.; Mahamadu, A.M.; Mahdjoubi, L.; Boguslawski, P. bim-based immersive collaborative environment for furniture, fixture and equipment design. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getuli, V.; Capone, P.; Bruttini, A.; Isaac, S. bim-based immersive Virtual Reality for construction workspace planning: A safety-oriented approach. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunseiju, O.O.; Akanmu, A.A.; Bairaktarova, D. Mixed reality based environment for learning sensing technology applications in construction. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.E.; Kineber, A.F.; Elshaboury, N.; Ekundayo, D.; Bello, S.A. Exploring the benefits of virtual reality adoption for successful construction in a developing economy. Buildings 2023, 13, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, C.S.; Song, J.; Lee, K.; Lee, S.; Kwon, S. Smart facility management system based on open bim and augmented reality technology. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdatikhaki, F.; El Ammari, K.; Langroodi, A.K.; Miller, S.; Hammad, A.; Doree, A. Beyond data visualization: A context-realistic construction equipment training simulators. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Hurtado, J.; Muñoz-La Rivera, F.; Mora-Serrano, J.; Deraemaeker, A.; Valero, I. Proposal for the deployment of an augmented reality tool for construction safety inspection. Buildings 2022, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boos, U.C.; Reichenbacher, T.; Kiefer, P.; Sailer, C. An augmented reality study for public participation in urban planning. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2023, 17, 48–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhoum, E.S.; Younis, A.A.; Aboulata, H.K.; Bekhit, A.R. Impact assessment of implementing virtual reality in the egyptian construction industry. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messi, L.; Spegni, F.; Vaccarini, M.; Corneli, A.; Binni, L. Seamless augmented reality registration supporting facility management operations in unprepared environments. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2024, 29, 1156–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Roupé, M. Real-world applications of bim and immersive VR in construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzarrad, A.; Miller, M.; Durham, L.; Chowdhury, S. Revolutionizing construction safety: Introducing a cutting-edge virtual reality interactive system for training us construction workers to mitigate fall hazards. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1320175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafey, A.; Saar, C.C.; Aminudin, E.B.; Gheisari, M.; Usmani, A. Technology acceptance model for augmented reality and building information modeling integration in the construction industry. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2020, 25, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhady, A.; Alanany, M.; Khodair, Y.; Salem, S.; El Maghraby, Y. Integrating building information modelling (bim) and extended reality (XR) in the transportation infrastructure industry. Adv. Bridge Eng. 2024, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Gu, N.; Masoumzadeh, S. Exploring the impact of digital technologies on team collaborative design. Buildings 2024, 14, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassereddine, H.; Veeramani, D.; Hanna, A.S. Design, development, and validation of an augmented reality-enabled production strategy process. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 730098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassereddine, H.; Schranz, C.; Hatoum, M.B.; Urban, H. Mapping the capabilities and benefits of ar construction use-cases: A comprehensive map. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. 2022, 14, 2571–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Park, S.; Lee, K.; Bae, J.; Kwon, S.; Cho, C.S.; Chung, S. Augmented reality-based bim Data Compatibility Verification Method for FAB Digital Twin implementation. Buildings 2023, 13, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Afsari, K.; Serdakowski, J.; DeVito, S.; Ensafi, M.; Thabet, W. Real-time and remote construction progress monitoring with a quadruped robot using augmented reality. Buildings 2022, 12, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbett, J.; Hartley, T.; Heesom, D. A multi-user collaborative bim-AR system to support design and construction. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, B.A.; Dossick, C.S. Immersive vr versus BIM for AEC Team Collaboration in Remote 3D Coordination Processes. Buildings 2022, 12, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schranz, C.; Urban, H.; Gerger, A. Potentials of augmented reality in a bim based building submission process. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.H.; Isnaeni, N.N. Integration of augmented reality and building information modeling for enhanced construction inspection—A case study. Buildings 2024, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.Y.; Juan, Y.K.; Lu, S. Comparing bim-Based XR and Traditional Design Process from Three Perspectives: Aesthetics, Gaze Tracking, and Perceived Usefulness. Buildings 2022, 12, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarini, M.; Spegni, F.; Giretti, A.; Pirani, M.; Carbonari, A. Interoperable mixed reality for facility management: A cyber-physical perspective. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2024, 29, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Rashidi, A.; Talei, A.; Kong, D. Innovative point cloud segmentation of 3d light steel framing system through synthetic bim and Mixed Reality Data: Advancing Construction Monitoring. Buildings 2024, 14, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamiase, V.; Jrade, A. A cloud-based integration of building information modeling and virtual reality through game engine to facilitate the design of age-in-place homes at the conceptual stage. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2024, 29, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, J.; Riedl, M.; Matt, D. bim-based and AR Application Combined with Location-Based Management System for the Improvement of the Construction Performance. Buildings 2019, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harode, A.; Ensafi, M.; Thabet, W. Linking bim to Power BI and HoloLens 2 to Support Facility Management: A Case Study Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Zaidi, S.F.A.; Yang, J.; Park, C.; Lee, D. Construction work-stage-based rule compliance monitoring framework using computer vision (cv) Technology. Buildings 2023, 13, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Jin, R.; Jeon, C.H.; Shim, C.S. bim-based mixed-reality application for bridge inspection and maintenance. Constr. Innov. 2022, 22, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalek, I.A.; Chalhoub, J.M.; Ayer, S.K. Augmented reality for identifying maintainability concerns during design. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatoishi, M.; Fruchter, R. Construction management in space: Explore solution space of optimal schedule and cost estimate. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2023, 28, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Zhang, J. A new framework to address bim Interoperability in the AEC Domain from Technical and Process Dimensions. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, P.; Costa, C.M.; Rocha, L.; Malaca, P.; Costa, P.; Moreira, A.P.; Sousa, A.; Veiga, G. Collaborative welding system using bim for Robotic Reprogramming and Spatial Augmented Reality. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerger, A.; Urban, H.; Schranz, C. Augmented reality for building authorities: A use case study in austria. Buildings 2023, 13, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallgren, M.V.; Roupe, M.; Johansson, M. 4D modelling using virtual collaborative planning and scheduling. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potseluyko, L.; Pour Rahimian, F.; Dawood, N.; Elghaish, F.; Hajirasouli, A. Game-like interactive environment using bim-based virtual reality for the timber frame self-build housing sector. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gong, S.; Tan, Z.; Demian, P. Immersive technologies-driven building information modeling (bim) in the Context of Metaverse. Buildings 2023, 13, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, J.; Ayer, S.K.; Ariaratnam, S.T. Augmented reality for enabling un- and under-trained individuals to complete specialty construction tasks. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Y.P.; Mukul; Gupta, N. Deep learning model based multimedia retrieval and its optimization in augmented reality applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 8447–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. A theoretical analysis method of spatial analytic geometry and mathematics under digital twins. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getuli, V.; Bruttini, A.; Sorbi, T.; Fornasari, V.; Capone, P. Integrating spatial tracking and surveys for the evaluation of construction workers’ safety training with virtual reality. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2024, 29, 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, K.W.; Kc, C.; Ochoa, J.J.; Gu, N.; Walsh, J.; Smith, R.T.; Thomas, B.H. The identification, development, and evaluation of bim-ARDM: A BIM-Based AR Defect Management System for Construction Inspections. Buildings 2022, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Gu, C.; Sun, J. A study of factors influencing the continuance intention to the usage of augmented reality in museums. Systems 2022, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omaran, S.; Al-Zuheriy, A. Integrating building information modeling and virtual reality to develop real-time suitable cost estimates using building visualization. Int. J. Eng. Trans. Appl. 2023, 36, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.C.; Sousa, H.; Gondim, I.A. smarts-Based Decision Support Model for CMMS Selection in Integrated Building Maintenance Management. Buildings 2023, 13, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Louis, J.; Albert, A. Incorporating worker awareness in the generation of hazard proximity warnings. Sensors 2020, 20, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkiewicz, A.; Salach, M.; Strzałka, D.; Budzik, G.; Nikodem, A.; Wójcik, H.; Witek, M. vr Education Support System—A Case Study of Digital Circuits Design. Energies 2022, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, E.; Sjöström, M. Camera and lidar-based view generation for augmented remote operation in mining applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82199–82212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian Jelodar, M.; Wilkinson, S.; Kalatehjari, R.; Zou, Y. Designing for construction procurement: An integrated decision support system for building information modelling. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2022, 12, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J. Application of traditional architectural decoration elements in modern interior design based on 3d virtual imaging. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 9957151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, M.; Beyea, D.; Leith, A.P.; Ratan, R.A.; Chen, V.H.H.; Klebig, B. Beyond genre: Classifying virtual reality experiences. IEEE Trans. Games 2022, 14, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dong, L. Virtual reality technology in landscape design at the exit of rail transit using smart sensors. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 6519605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Muñoz-La Rivera, F.; Mora-Serrano, J. Virtual reality training for occupational risk prevention: Application case in geotechnical drilling works. Int. J. Comput. Methods Exp. Meas. 2023, 11, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenais, A.; Ariaratnam, S.T.; Ayer, S.K.; Smilovsky, N. Integrating geographic information systems and augmented reality for mapping underground utilities. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.A.; Yitmen, I.; Alizadehsalehi, S.; Celik, T. Adoption of virtual reality (vr) for site layout optimization of construction projects. Tek. Dergi/Technical J. Turk. Chamb. Civ. Eng. 2020, 31, 9833–9850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, S.M.; Castronovo, F.; Ciribini, A.L. A design review session protocol for the implementation of immersive virtual reality in usability-focused analysis. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2020, 25, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.; Boag-Hodgson, C.; Ryley, T.; Mavin, T.J.; Potter, L.E. Using extended reality in flight simulators: A literature review. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2023, 29, 3961–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einloft, J.; Meyer, H.L.; Bedenbender, S.; Morgenschweis, M.L.; Ganser, A.; Russ, P.; Hirsch, M.C.; Grgic, I. Immersive medical training: A comprehensive longitudinal study of extended reality in emergency scenarios for large student groups. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annabestani, M.; Sriram, S.; Caprio, A.; Janghorbani, S.; Wong, S.C.; Sigaras, A.; Mosadegh, B. High-fidelity pose estimation for real-time extended reality (xr) visualization for cardiac catheterization. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishehgarkhaneh, M.B.; Keivani, A.; Moehler, R.C.; Jelodari, N.; Laleh, S.R. Internet of things (iot), building information modeling (bim), and digital twin (dt) in construction industry: A review, bibliometric, and network analysis. Buildings 2022, 12, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehsalehi, S.; Hadavi, A.; Huang, J.C. Assessment of aec students’ performance using BIM-into-VR. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, I. Mechatronic system used in the laboratory for complex analysis applied and used in industry; [Sistem mecatronic utilizat in laborator pentru analize complexe aplicate Și utilizate În industrie]. Inmateh-Agric. Eng. 2022, 68, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Keung, C.; Suh, M.; Kim, T.W. Evaluation framework for bim-based VR applications in design phase. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2021, 8, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hire, S.; Sandbhor, S.; Ruikar, K. A conceptual framework for bim-Based Site Safety Practice. Buildings 2024, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, Y. Research on the intelligent construction of the rebar project based on bim. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.M.L.; Mora-Serrano, J.; Oñate, E. Virtual reality for the creation of stories and scenarios for construction safety: Social distancing in the covid-19 Pandemic Context. Int. J. Comput. Methods Exp. Meas. 2023, 11, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatanov, O.; Bykov, A.; Serginko, M.; Miroshnichenko, D. Implementation of augmented reality technologies in the training process with the design of aircraft equipment. Radioelectron. Comput. Syst. 2021, 1, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Query |

|---|---|

| Scopus (n = 350) | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“extended reality” OR “augmented reality” OR “mixed reality” OR “virtual reality”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (construction AND industry) AND PUBYEAR > 2018 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “ENGI”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”))) |

| Web of Science (n = 469) | TS = (Use of extended reality in the construction industry (Topic) AND Augmented Reality (OR – search within topic) AND Virtual Reality (OR – search within topic) AND Mixed Reality (OR – search within topic) AND English (Languages) AND Engineering (Research Areas) AND Article (Document Types) AND 2019–2024 (Publication Years), excluding 2025) |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Topic | Studies addressing extended reality (XR), augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), or mixed reality (MR) applied to the construction industry. | Studies not related to XR, AR, VR, or MR in construction. |

| Publication year | Published between 2019 and 2024 (inclusive). | Published before 2019 or after 2024. |

| Document type | Peer-reviewed journal articles (document type “ar”). | Conference papers, book chapters, reviews, reports, or other non-journal documents. |

| Language | Written in English. | Written in languages other than English. |

| Keywords | Include terms related to construction and XR (e.g., “construction industry”, “virtual reality”, “augmented reality”, “mixed reality”, “BIM”, “Building Information Modeling”, “Industry 4.0”). | Contain excluded terms that indicate a different primary focus (e.g., “digital twin” without explicit XR, “aerospace”). |

| Thematic relevance | Abstract and/or keywords explicitly address at least one research question on XR, AR, VR, or MR in construction. | Abstract and keywords do not explicitly address XR technologies applied to the construction industry. |

| Subject area | Indexed in civil engineering, construction technology, or general engineering subject areas (e.g., Scopus/WoS “Engineering”, “Civil Engineering”). | Indexed primarily in thematic areas unrelated to civil engineering, construction, or building technology. |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Application area | Primary domain, process, or task in which XR is applied within the construction lifecycle. |

| Type of extended reality used | Specific XR mode reported in the study (e.g., AR, VR, MR, or generic XR). |

| Head-mounted displays (HMDs) used | Head-mounted displays and related devices employed to deliver XR experiences, and their role in the study. |

| Graphics engine used | Real-time graphics engine or development platform used to implement the XR application (e.g., Unity, Unreal Engine). |

| XR implementation limitations | Technical, organizational, and human factors that limit or challenge the implementation of XR in construction contexts. |

| Barrier Category | Specific Barrier | Freq. | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Financial difficulties related to implementation costs and limited resources | 11 | [9,10,11,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] |

| Organizational | Lack of technical skills or specialized knowledge among users or personnel involved | 23 | [10,19,20,24,28,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] |

| Organizational | Problems related to coordination, effective communication, or collaboration among project stakeholders | 11 | [26,27,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| Organizational | Resistance to change and preference for traditional methods | 12 | [11,27,31,36,38,40,54,58,59,60,61,62] |

| Technological | Difficulties in data conversion and transfer between different platforms or formats | 22 | [5,19,39,42,45,50,52,54,55,56,58,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| Technological | Limitations related to hardware and software requirements | 35 | [9,10,11,24,26,27,29,30,31,32,34,37,38,40,44,45,53,54,56,59,65,67,69,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] |

| Technological | Interoperability or compatibility issues between systems or devices | 24 | [2,9,27,32,36,37,38,39,42,44,49,53,58,64,65,69,70,74,75,78,81] |

| Technological | Technical limitations related to hardware and software performance | 19 | [28,29,42,54,68,72,82,83,84,85,86,87] |

| Infrastructure | Insufficient technological infrastructure or adverse environmental and physical constraints | 18 | [10,28,35,37,41,42,49,50,52,70,79] |

| Methodological | Lack of previous studies, documented data or clear implementation procedures | 14 | [28,30,36,39,43,44,51,58,68,70,71,72,88,89] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gornall, J.; Peña, A.; Pinto, H.; Rojas, J.; Correa, F.; García, J. Extended Realityin Construction 4.0: A Systematic Review of Applications, Implementation Barriers, and Research Trends. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010009

Gornall J, Peña A, Pinto H, Rojas J, Correa F, García J. Extended Realityin Construction 4.0: A Systematic Review of Applications, Implementation Barriers, and Research Trends. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleGornall, Jose, Alvaro Peña, Hernan Pinto, Jorge Rojas, Fabiano Correa, and Jose García. 2026. "Extended Realityin Construction 4.0: A Systematic Review of Applications, Implementation Barriers, and Research Trends" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010009

APA StyleGornall, J., Peña, A., Pinto, H., Rojas, J., Correa, F., & García, J. (2026). Extended Realityin Construction 4.0: A Systematic Review of Applications, Implementation Barriers, and Research Trends. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010009