1. Introduction

In the field of biotechnology, the growth of a living organism is not only a significant phenotype in itself [

1,

2], but also a crucial factor determining the productivity of valuable biomass-derived components such as nutrients, proteins, and metabolites. Therefore, measuring the growth of organisms is one of the fundamental tasks that researchers must perform. Growth is typically measured by tracking biomass or volumetric size over time [

3]. For microorganisms, it is common to measure growth by assessing optical density to determine cell concentration [

2], or by counting the number of microorganisms per unit volume using a microscope. If an organism or a specific part of it (e.g., a leaf in the case of plants) grows in two dimensions along the x and y axes, while growth along the third z-axis can be neglected, monitoring growth by measuring frond count or surface area on a plane is feasible. However, manual measurement is time-consuming, prone to errors, and can be challenging when the number of samples to be measured is large. In such cases, it may be difficult for a human to perform these tasks without the assistance of automated equipment.

As an alternative, taking images with a digital camera and analyzing them using image analysis software can provide a fast, accurate, and reliable method of analysis. This approach is also non-destructive, requiring no manipulation of the organisms [

4], and is non-invasive which preserves aseptic growth. Using image analysis to measure area and subsequently analyze growth has been successfully applied to various organisms, including plants such as

Arabidopsis thaliana [

5],

Gymnaster savatieri K. [

6], and

Nicotiana tabacum [

7], as well as fungi such

as Gloeophyllum trabeum and

Trametes versicolor [

8], and

Coniophora puteana,

Gloeophyllum trabeum, and

Rhodonia placenta [

9]. Additionally, the duckweed (

Lemna japonica) studied in this paper is a free-floating aquatic plant that primarily reproduces vegetatively through asexual budding or division, where the fronds detach from the parent plant. The area derived from overhead images of the entire duckweed population demonstrates a strong linear correlation with fresh weight [

10,

11], thereby enabling non-destructive growth assessment based on area measurements.

Conventional imaging systems involve capturing images with a digital camera and then analyzing them on a computer, or connecting the camera to the computer via a wired connection [

5,

6,

7,

9,

11,

12,

13]. For example, GROWSCREEN captures plant images to calculate leaf area and analyze growth using a CCD camera directly connected to a PC [

7]. Although effective, such systems lack wireless transmission capability and are limited in scalability due to their dependence on wired setups. Other systems, such as that developed by Li et al. [

14], use smartphone cameras to capture and wirelessly upload images for analysis in MATLAB R2021b (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA) or Python 3.12. While wireless transmission is supported, the use of costly smartphones and non-GUI software limits practicality. Müller-Linow et al. also utilized smartphones and developed an app that captures images and computes plant leaf area [

15]. Most of these imaging systems use conventional image processing techniques, such as Otsu [

16] or adaptive thresholding [

17] to detect organisms, but these methods struggle when contrast between the subject and background is low. Overall, although these systems demonstrate the feasibility of image-based plant growth monitoring, they are difficult to scale for large-area or high-throughput applications because deploying multiple high-cost cameras and wired connections across wide monitoring areas, such as large scale raceways used in duckweed growth systems, is impractical.

With the advent of the Arduino platform (

www.arduino.cc), it has become feasible to create imaging devices with affordable microcontrollers [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Among Arduino-compatible imaging devices, the ESP32-CAM (Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China) has emerged as one of the most widely used solutions. This microcontroller board is based on the ESP32 and features a 2-megapixel UXVGA (1600 × 1200 pixels) OV2640 camera module, which is the configuration adopted by most commercially available ESP32-CAM units. The OV2640 is also supported by extensive firmware and library support, enabling straightforward integration into ESP32-based imaging platforms. The ESP32 microcontroller has a dual-core processor with a clock speed of up to 240 MHz and 520 KB of SRAM memory, enabling a variety of processing tasks. Despite these capabilities, as of 2024, the purchase cost is approximately

$10 USD per unit, making it an attractive imaging device. Most notably, the ESP32-CAM supports Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, allowing images and various messages to be wirelessly transmitted to a computer or online server. Additionally, it can be programmed to perform specific functions and operations, making it highly adaptable to the user’s needs. Therefore, it meets the essential requirements for a scalable microcontroller-based imaging system, offering low cost, wide commercial availability, compatibility with Arduino-based development environments, built-in wireless communication capability, and stable long-term operation.

Similar to the ESP32-CAM, there have been cases in which imaging systems were constructed using Raspberry Pi with Wi-Fi capability for plant phenotyping and laboratory time-lapse imaging [

24,

25]. Although these systems support wireless transmission, the Raspberry Pi, as a single-board computer, is approximately four- to eight-times more demanding in both cost and power consumption compared to the ESP32-CAM microcontroller, resulting in substantially higher installation and maintenance costs. Moreover, these Raspberry Pi–based systems do not provide dedicated automated image-analysis software integrated with the hardware.

In this study, we developed a GUI–based system named SIPEREA (version 1.2; Scalable Imaging Platform for Measuring Area), an imaging platform that utilizes cost-effective ESP32-CAM modules wirelessly connected to a computer. SIPEREA’s software enables asynchronous, sequential image acquisition and automated analysis of collected images. By eliminating the need for traditional wired connections between cameras and computers, SIPEREA supports the development of a scalable, flexible imaging system capable of operating multiple ESP32-CAM modules simultaneously.

The SIPEREA platform also includes an image analysis program capable of processing the acquired images. This software employs a deep neural network (DNN) to perform automatic segmentation of biological regions and calculates their area. The incorporation of a DNN overcomes limitations of conventional binarization techniques. In biological culture images—such as those of duckweed grown in Petri dishes or multi-well plates—non-biological structures such as plate edges and reflections often appear alongside the organism. As mentioned earlier, traditional binarization methods, which rely solely on global or adaptive thresholding, struggle to distinguish the target organism from such background artifacts, resulting in the inclusion of unwanted regions in the binary output. In contrast, the trained DNN learns complex spatial and textural patterns, selectively excluding background artifacts while preserving only the organism, thereby improving the precision of area quantification. This leads to more precise quantification of the biological area in images. A built-in training module allows users to refine the segmentation model using paired RGB images and ground truth mask images.

To demonstrate the utility of SIPEREA, we cultured the aquatic plant duckweed (Lemna japonica), captured time-lapse images over multiple days, and analyzed the collected images to compute frond area. From these measurements, we determined the plant’s relative growth rate and doubling time.

To our knowledge, a platform that combines (a) reliable asynchronous, sequential wireless acquisition from multiple ESP32-CAM modules, (b) robust DNN-based segmentation, and (c) automated biological growth quantification within a unified and reproducible workflow has been rarely reported in the scientific literature. Notably, all three components are implemented as user-friendly GUI programs, making the system accessible and practical even for users without specialized expertise. While individual components such as ESP32-CAM imaging, wireless data transmission, or U-Net–based segmentation have been studied independently, integrating these GUI-based elements into a fully operational biological monitoring pipeline remains highly uncommon, and we were unable to identify studies demonstrating this level of multi-layer system integration.

2. Software Description

2.1. Platform Overview

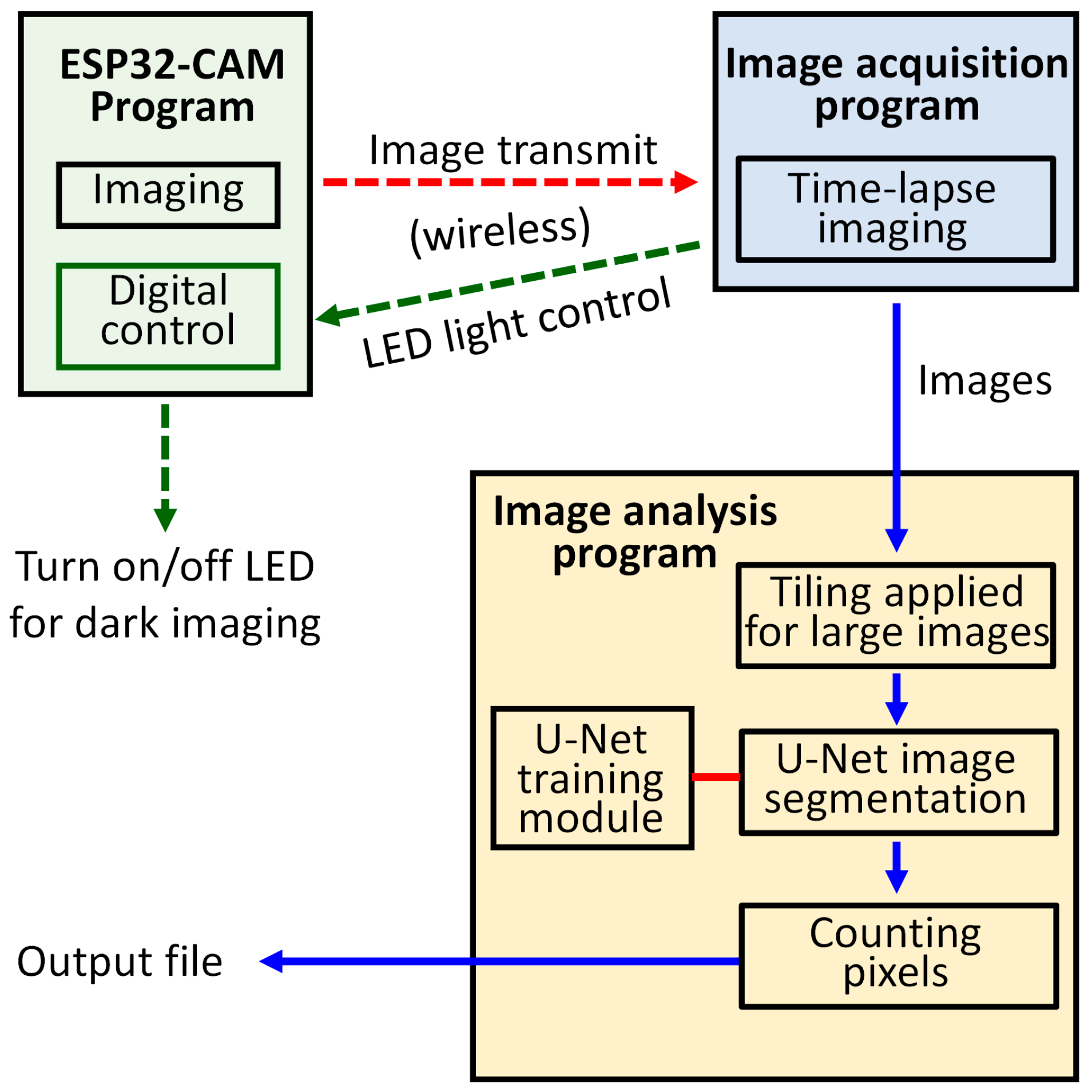

The SIPEREA platform consists of three software tools (

Figure 1). The first tool is the firmware program running on the ESP32-CAM, which captures images and transmits them via Wi-Fi. It also includes functionality for controlling the auxiliary LED light source used for dark imaging, where plants are grown under day and night lighting cycles, and during the night phase, the LED, with very low brightness, is briefly turned on for imaging before being switched off again to minimize disruption to the night cycle. The second tool is the image acquisition program, which periodically receives images wirelessly from multiple ESP32-CAMs and stores them on the computer’s hard drive. The third tool is the image analysis program, which employs a DNN to perform automatic segmentation of the organisms in time-lapse images, and then computes their total area for the construction of growth curves. The source codes, executable files, and manuals can be downloaded for free from

https://vgd.hongik.ac.kr/Software/SIPEREA,

https://mcdonald-nandi.ech.ucdavis.edu/tools, or

https://github.com/QuantSKhong/SIPEREA3 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

2.2. ESP32-CAM Program

The firmware program for the ESP32-CAM is responsible for capturing images and performing wireless transmission. This program was developed by modifying the official ESP32 camera example sketch (program) provided by Espressif, the manufacturer of the ESP32 board. The official ESP32 camera example sketch enables the ESP32-CAM to connect to an internet access point (AP), allowing users to wirelessly access the ESP32-CAM through a web browser using the camera’s IP address. It offers a convenient GUI interface for users to view real-time video and change various camera settings.

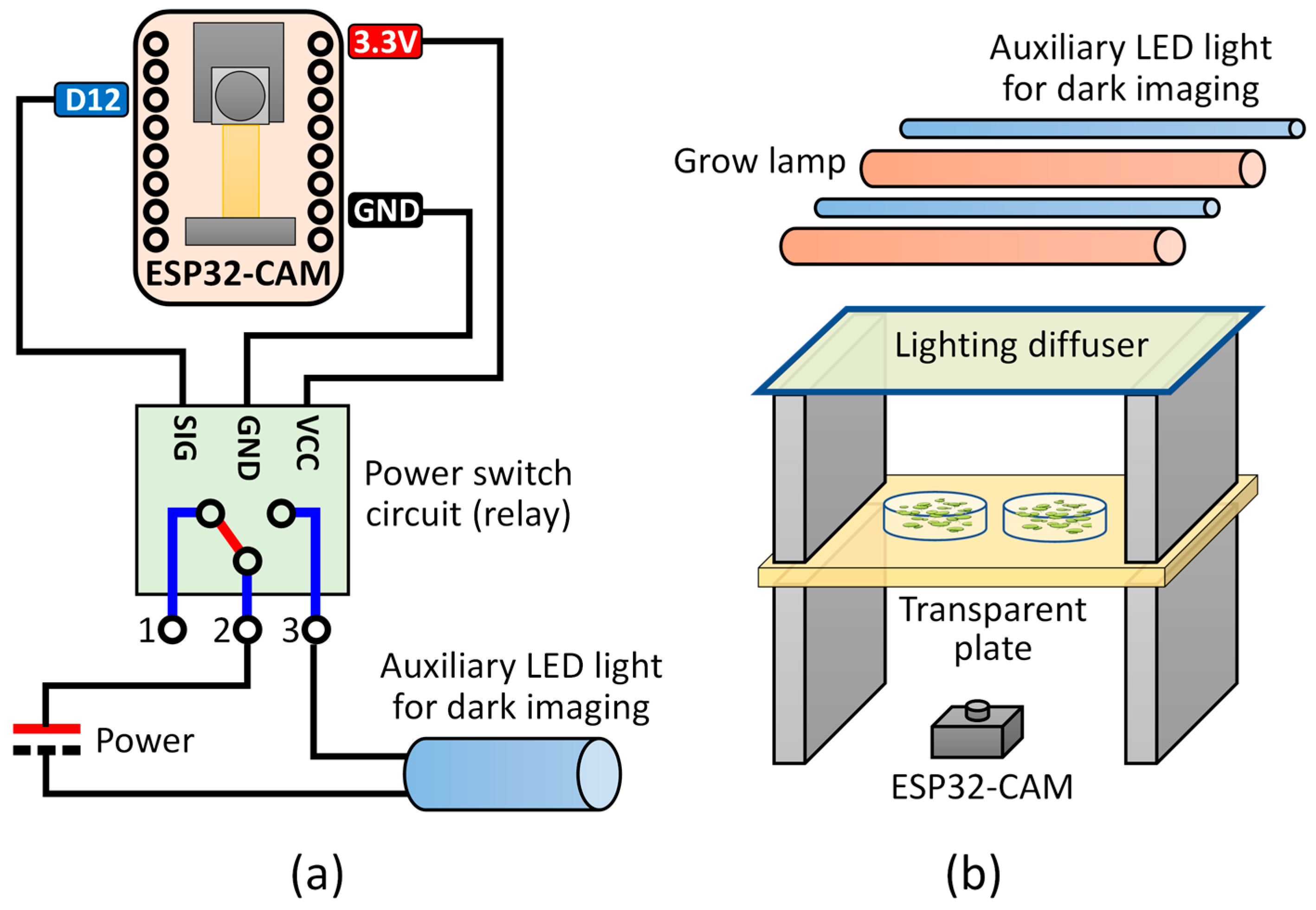

For SIPEREA, modifications were made to the official example sketch to ensure that each ESP32-CAM has a fixed IP address assigned. Additionally, functionality was implemented to control an auxiliary LED light for dark imaging using the ESP32-CAM’s digital port (digital pin 12) (

Figure 2a). Furthermore, the program periodically checks the access point (AP) connection status and automatically reconnects if the connection is lost. In the firmware program, an individual ESP32-CAM is configured to have a unique static IP address when connected to an AP for control. The ESP32-CAM allows real-time monitoring and optional LED control during imaging.

Regarding the camera settings of the ESP32-CAM, various settings are preset in the program by default. Brightness, contrast, exposure rate, etc., are set to change automatically, which generally yields high-quality images in most imaging environments without the need for further modification. However, users can make changes, if necessary, through the GUI screen or the program source code.

After connecting to the access point, the ESP32-CAM enters a standby mode. When users enter the IP address of the ESP32-CAM (e.g.,

http://192.168.0.100) into their internet browser, a GUI appears. Through this GUI, users can preview live images and adjust various camera settings such as image size, brightness, and contrast. Furthermore, the program allows users to turn the auxiliary LED on or off.

The ESP32-CAM can be installed in various positions and angles according to the imaging scenario. For example, to take images while cultivating plants, the LED can be installed above the target object below it, and the ESP32-CAM can be positioned beneath the object (

Figure 2b). Aiming the light source directly at the digital camera may cause problems with excessive brightness in the central area where the light directly strikes. Installing a light diffuser beneath the LED can alleviate this problem, although it may slightly reduce the light intensity at the plant location.

2.3. Image Acquisition Program

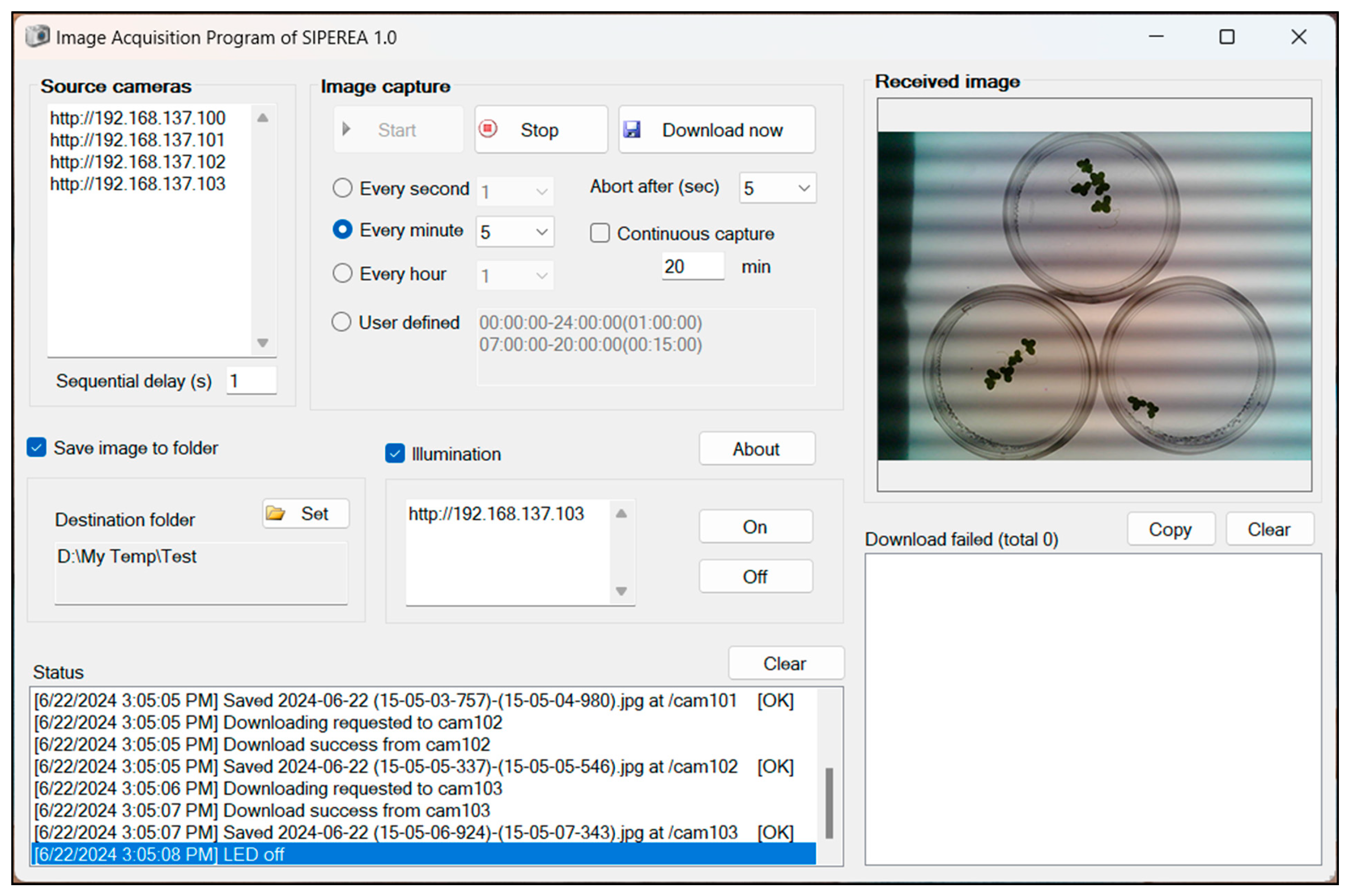

The image acquisition program is written in Microsoft Visual Basic. NET Framework 4.8 and is executable on Windows OS (

Figure 3). It can perform time-lapse imaging at regular intervals from multiple ESP32-CAM devices connected to a wireless AP, and saves the images as files on the local storage of the computer.

To receive images from the ESP32-CAM, the computer running the image acquisition program must be connected to the same wireless AP or local network as the ESP32-CAMs. The image acquisition program initiates imaging on the ESP32-CAM by accessing the static IP address of the ESP32-CAM. After capturing an image, the ESP32-CAM transmits the resulting JPG file to the image acquisition program.

The image acquisition program is designed to download images asynchronously through multi-threading, allowing simultaneous reception of images from multiple ESP32-CAMs. However, if a large number of ESP32-CAM devices transmit images simultaneously, it may temporarily overload the wireless network, causing delays or unsuccessful transmissions. Therefore, the image acquisition program does not request imaging and image transmission from all ESP32-CAMs simultaneously but performs image acquisition from the ESP32-CAMs sequentially at specified intervals (e.g., every 1 s). The asynchronous transmission of images from multiple ESP32-CAMs can occur simultaneously, but the limited number of transmission lines minimizes the overall network load impact. Users can also set the image transmission response time-out period. If the image transmission response time exceeds the time-out period, the image acquisition program forcibly terminates the image transmission, ensuring the overall stability of the operation. All these operational methods theoretically enable the imaging control of many ESP32-CAMs with just one execution of the image acquisition program.

In this system, the image timestamping is synchronized by the PC rather than by the individual ESP32-CAM units. The image acquisition program running on the PC sends a capture command to each ESP32-CAM, and the cameras capture and transmit the images back to the program over the wireless connection. Thus, the capture timing is determined by the PC’s clock, and not by any internal clock synchronization among the ESP32-CAM devices.

Figure 4 demonstrates an asynchronous image capture scenario using multiple ESP32-CAMs. Each ESP32-CAM (hereafter referred to as Cam) operates with an image capture interval of 30 min, and the six Cams are triggered sequentially at 5-s intervals from Cam 1 to Cam 6. Each Cam captures an image of approximately 100 KB in size, and the entire wireless transmission is typically completed within one second. The 30-min capture interval is chosen because aquatic plants generally exhibit relatively slow growth rates, and thus, capturing images at this interval is sufficient to accurately monitor and calculate growth trends without missing significant changes.

During the first round of image capture, all six Cams successfully capture and transmit their images, completing the entire round within approximately 26 s. The next, or second-round, image capture begins after an interval of about 30 min. In the second round, Cams 1, 5, and 6 successfully completed image transmission, whereas Cams 2, 3, and 4 required more than one second to complete the process. Although Cams 2 and 4 experienced transmission delays, they eventually succeeded in image transfer. In contrast, Cam 3 reached the time-out period of 10 s, and its image acquisition thread was forcibly terminated. Although Cam 3 failed to transmit its image, this failure did not affect the operation of the other Cams because each capture thread runs independently.

During the capture process, around the 30 min 10 s timepoint, the image capture threads of Cams 2 and 3 briefly overlapped for about one second, and at approximately 30 min 15 s, the threads of Cams 3 and 4 ran concurrently for about 3–4 s. Given a capture interval of 5 s and a time-out period of 10 s, threads that reach the time-out threshold are forcibly terminated; therefore, at most two image capture threads can be active simultaneously. This asynchronous yet sequentially triggered image capture method minimizes excessive wireless network traffic, even when multiple ESP32-CAMs operate concurrently. The system is designed such that temporary network congestion or partial transmission failures do not significantly affect the overall image capture process.

Meanwhile, the image acquisition program has the capability to control an auxiliary LED for dark imaging. When conducting experiments that require simulating day and night by repeatedly turning the lighting on and off, imaging during the day poses no issue due to the presence of light. However, imaging at night, when the lights are off, is not feasible. The image acquisition program addresses this by periodically sending a command to the ESP32-CAM to turn on the LED before capturing an image and turning it off afterward.

Regarding the dark horizontal bands observed in

Figure 3, these artifacts typically occur when a standard LED is imaged at close range. These thick horizontal regions of alternating brightness are primarily caused by LED flickering due to its modulation frequency (i.e., refresh rate or flicker frequency), and are commonly referred to as LED flicker or banding artifacts.

2.4. Image Analysis Program

A user-friendly image analysis program was developed in Python to quantify the area of biological regions in acquired images (

Figure 5). The program employs TensorFlow to perform image segmentation using a deep neural network (DNN) based on the U-Net architecture. Specifically, it identifies biological regions within each image and assigns a pixel value of 255 (in an 8-bit grayscale image) to these regions to represent the foreground, while all other pixels are assigned a value of 0 as background, thereby generating a binary mask. The area of the biological region is then calculated by counting the number of foreground pixels in the binary image. In batch-processing mode, the program automatically and sequentially analyzes all images within a specified folder (

Figure 5a). A built-in training module is also provided, enabling users to retrain the U-Net model using paired datasets of original color images and the corresponding binarized ground-truth masks (

Figure 5b).

The core of the image segmentation module is a convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the U-Net architecture. U-Net, originally developed for biomedical image segmentation tasks, is well known for its outstanding performance in accurately delineating complex and fine structures [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The architecture follows a symmetric encoder–decoder structure with four resolution levels [

26,

28]. In the encoder path, two 3 × 3 convolutional layers with ReLU activation are followed by a 2 × 2 max pooling operation that reduces spatial resolution while increasing the number of feature maps (32 → 64 → 128 → 256). In the decoder path, each resolution level includes upsampling, a 2 × 2 convolution layer, concatenation with the corresponding encoder output via skip connections, and two additional 3 × 3 convolutional layers. These skip connections allow the decoder to reuse fine-grained spatial features from the encoder, thereby improving localization performance, particularly along object boundaries.

The model ends with a 1 × 1 convolutional layer and a sigmoid activation function to generate a binary mask representing the probability that each pixel belongs to the biological object. Importantly, the following modifications to the original U-Net architecture represent a unique aspect of our implementation: a dropout layer (with a rate of 0.5) is included at the bottleneck (the deepest part of the network) to reduce overfitting, and an additional 3 × 3 convolution with 16 filters is inserted prior to the output layer, providing a transitional step for stable output generation.

To accommodate full-resolution images captured using ESP32-CAM modules (1600 × 1200 pixels), the program uses a tiling approach. Each input image is divided into overlapping tiles of 512 × 512 pixels, which are individually processed by the model. The outputs are then seamlessly merged through a weighted averaging method to reconstruct the full-size binary mask. This approach allows high-resolution image processing while maintaining memory efficiency.

The analysis module supports batch processing by automatically detecting and processing all images in the appropriate format in a specified input folder. For each image, the system binarizes the image, calculates the white pixel area within each user-defined region of interest (ROI), and exports results to a CSV file. If a ROI.csv file is not provided, the entire image area is analyzed by default. The CSV output includes the filename, pixel counts per ROI, the elapsed time (in days) since the first image, and the processing time (in seconds).

One of the key strengths of the program lies in its built-in training module, which enables users to train the segmentation model with custom image datasets. The training data consist of pairs of source images and their manually binarized masks, both resized to 512 × 512 pixels. To address the challenge of limited training samples and improve generalization, the program performs real-time data augmentation during training. Augmentation techniques include random rotation (±15°), horizontal flipping, translation (up to 10% shift), shearing, and zooming (range: 90–110%). These transformations are applied consistently to both the input images and their corresponding masks to preserve pixel-wise alignment. The U-Net model is trained using the Adam (adaptive moment estimation) optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0001 and a batch size of 2. Adam adaptively adjusts the learning rate for each parameter by estimating the first- and second-order moments of the gradients, enabling stable and efficient convergence even in the presence of noisy or sparse gradients [

32]. Owing to its robustness and fast practical performance, Adam is widely adopted for training deep neural networks [

33,

34]. Binary cross-entropy was used as the loss function, as it is well suited for pixel-wise binary segmentation tasks.

To further enhance model robustness and mitigate overfitting, the training process adopts K-fold cross-validation (default k = 5). In this scheme, the dataset is partitioned into k equally sized folds; the model is iteratively trained on (k − 1) folds and validated on the remaining one. A fresh model instance is initialized for each fold to ensure statistical independence, and the training–validation performance metrics are recorded separately. After completing all folds, the program selects and loads the model with the lowest validation loss as the final inference model.

During training, the program splits the dataset into training and validation subsets and tracks key performance metrics, including accuracy and loss, over epochs. These metrics are saved in CSV files and visualized as plots, helping users monitor convergence and detect signs of overfitting. A model checkpoint corresponding to the best validation loss is saved automatically and used for inference after training is complete.

3. Illustrative Application

To demonstrate the utility of SIPEREA, the aquatic plant duckweed was cultured in liquid media in a Petri dish, and the collected images were analyzed to measure the total duckweed frond area over time. The experimental procedure is described below.

Auxiliary LED strips (pink–purple 2835 chips; purchased via AliExpress, Hangzhou, China) were installed for culturing light and dark imaging. Additionally, a light diffusion film (Junkin; purchased via Amazon, Seattle, WA, USA; ASIN: B09XGZP71S) was placed beneath the lights. The intensity of the light was adjusted by modifying the number of lights and the distance between the acrylic plate and the lights. A USB power switch module (SKU: 648-1, Pi Shop Inc., New Castle, DE, USA) was used to operate the LED strips. The GND and digital pin GPIO12 of an ESP32-CAM were connected to the signal input pin of the USB switch (

Figure 2a). The culturing light was set to a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle using a power timer (BND-60/U47, BN-LINK, Santa Fe Springs, CA, USA). Experiments were performed at ~23 °C and 50% humidity.

After setting up the imaging device, wild-type duckweed (

Lemna japonica) was cultured by placing 1–2 fronds in Schenk and Hildebrand’s (SH) medium [

35] on 6-cm-diameter plates. Four ESP32-CAMs were used to perform asynchronous and sequential imaging. Light intensity was measured at the plate location below the diffuser film using a quantum photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) meter (Hydrofarm, Santa Fe Springs, CA, USA) and averaged 130 µmol m

−2 s

−1. The auxiliary LED provided an illuminance of less than 2 µmol m

−2 s

−1, sufficient for imaging purposes but evaluated as having minimal impact on plant growth due to its low light intensity. Additionally, extending the imaging interval is expected to further minimize any potential effects on plant growth. After connecting the ESP32-CAM to a power source, the camera’s IP address was accessed via a web browser to adjust the plates to their optimal positions. The image acquisition program was set to capture images at 3-min intervals. The captured image resolution was 1600 × 1200 pixels. The computer used for image acquisition was an LG notebook computer (LG Electronics, Seoul, Republic of Korea) with specifications: i5-7200U (2.5 GHz; Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 8 GB RAM, 256 GB SSD, and Intel Dual Band Wireless AC 3168 (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The notebook computer ran four ESP32-CAMs to capture images at 3-min intervals. During the two-week operational period, there were no failures in image acquisition or transmission under the condition where a Wi-Fi hotspot was enabled on the Windows computer to create a local wireless network for connecting the ESP32-CAM modules. All four ESP32-CAM units individually collected all 6853 intended images, resulting in no missing data across any device. The average time taken from the moment an image capture was requested to the completion of image transmission was 600 ± 240 ms (mean ± standard deviation).

To calculate the area of duckweed from the collected images, image segmentation was first performed by training the image analysis module of SIPEREA. The training was conducted on a consumer-grade notebook PC equipped with an Intel Core i5-11400H CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 16 GB RAM, and a 512 GB NVMe SSD, running Windows 11. All computations were executed using CPU resources only, with a 90% CPU usage limit imposed to manage system performance and thermal stability.

A total of 61 images with a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels were used for model development, of which 48 were allocated for training and 13 for validation. These images were collected from 12 plates across two independent experiments, providing variability in both biological conditions and imaging environments. The dataset covered a broad range of growth stages, from images containing a single initial frond to those captured during the exponential phase with numerous fronds, thereby offering diverse morphological patterns to support robust model training. Ground-truth masks were generated semi-manually. Briefly, binary images were initially produced using adaptive thresholding in the PhenoCapture software (version 10.3;

https://phenocapture.com; accessed on 18 August 2025). Any undesired objects, excluding duckweed, were subsequently removed through manual correction. The accuracy of the binary masks was verified by iteratively overlaying them on the original images, ensuring precise delineation of the duckweed regions.

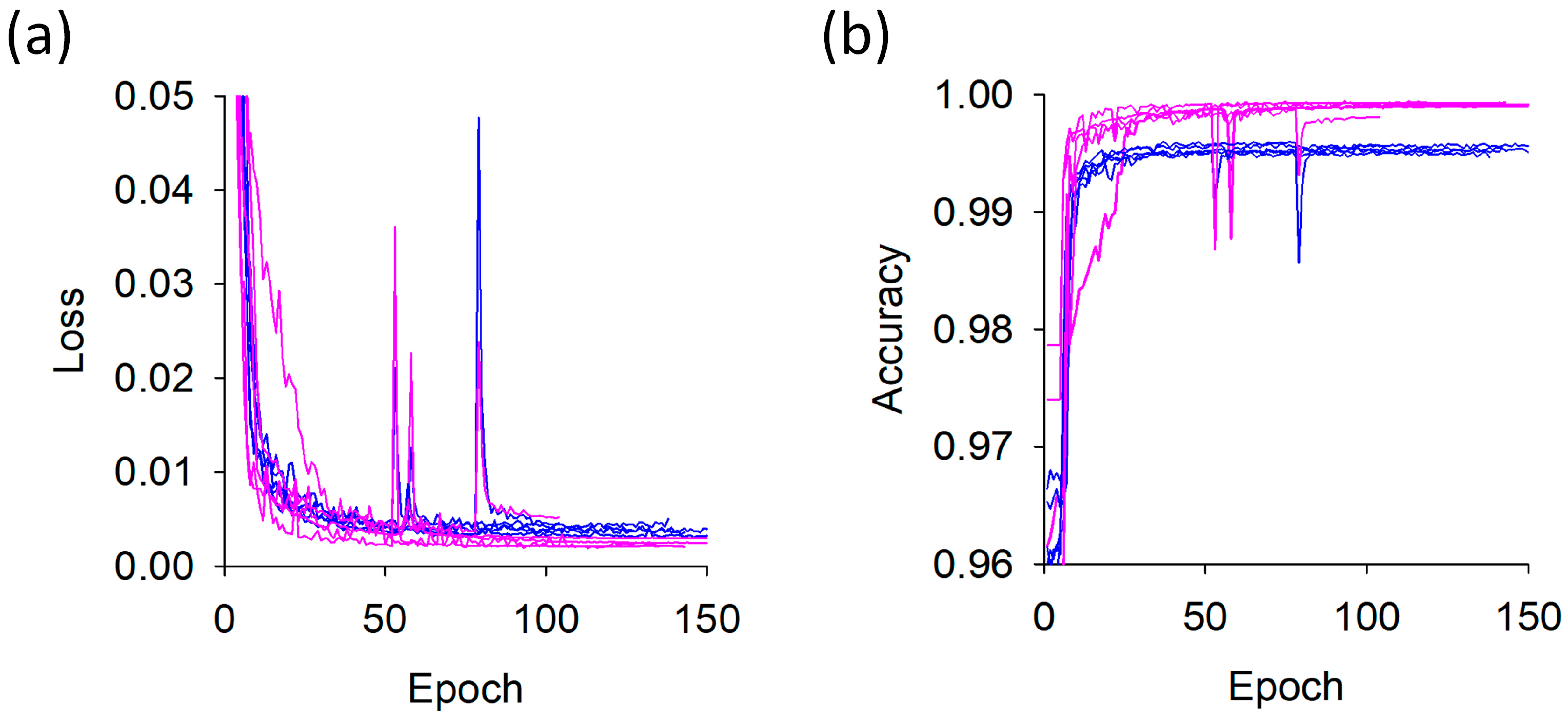

Training was performed for up to 150 epochs with an early stopping patience of 30 epochs (

Figure 6). The model was trained using k-fold cross-validation (

k = 5), where each fold required 1 h 32 min on average, with a variation of ±13 min. The total training time for all five folds was 7 h 41 min. Although the loss and accuracy curves varied slightly across folds, the training and validation trends were consistently similar, indicating the absence of fold-specific overfitting. Based on the best-trained models obtained within 100 epochs for each fold, the validation loss was 0.0026 ± 0.0007 and the validation accuracy was 0.9991 ± 0.0003. Although the dataset size was relatively limited, the task—pixel-level binary classification—is inherently less complex than multi-class or high-level semantic segmentation tasks, and the use of cross-validation further enhanced generalization. As a result, the limited number of images did not substantially impede the robustness or reliability of the training process.

Model performance was evaluated on the validation dataset using pixel-level metrics. The resulting confusion matrix consisted of 15,432,606 true negatives, 10,362 false positives, 543,522 true positives, and 4294 false negatives (unit: pixels). The segmentation model demonstrated excellent performance, achieving a pixel-wise accuracy of 99.91% (i.e., the proportion of correctly classified pixels among all pixels; correctly predicted pixels/total number of pixels). The Intersection over Union (IoU) was 0.974, measuring the overlap between predicted and ground truth regions, and the Dice similarity coefficient was 0.987, quantifying spatial agreement between prediction and reference. Additionally, the model achieved a precision of 0.981, a recall of 0.992, and a Receiver Operating Characteristic–Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) score of 1.000, indicating highly reliable foreground–background discrimination.

After completing the model training, the plate images captured during the experiment were processed using the image analysis program to calculate the area of duckweed. The average processing time per image was 4.6 ± 0.2 s (n = 110 images), measured on the same computer that was used for training the model. While the image processing time per image may seem relatively long, it is important to note that the goal of this imaging platform is not real-time analysis. Since biological growth in this application is relatively slow, capturing images every 30 min is generally sufficient to measure growth. If images are taken every 30 min, each ESP32-CAM would collect 48 images per day. Processing all these images would take less than 6 min (5.8 min = 48 images × (7.3 s/image) × (1 min/60 s)). Therefore, this level of processing time can be considered acceptable.

As shown in

Figure 7, the prediction probability map and final segmentation mask were generated, with non-biological objects (plate edges, shaded regions, LED artifacts) successfully removed, leaving only duckweed and demonstrating the high accuracy and robustness of the segmentation.

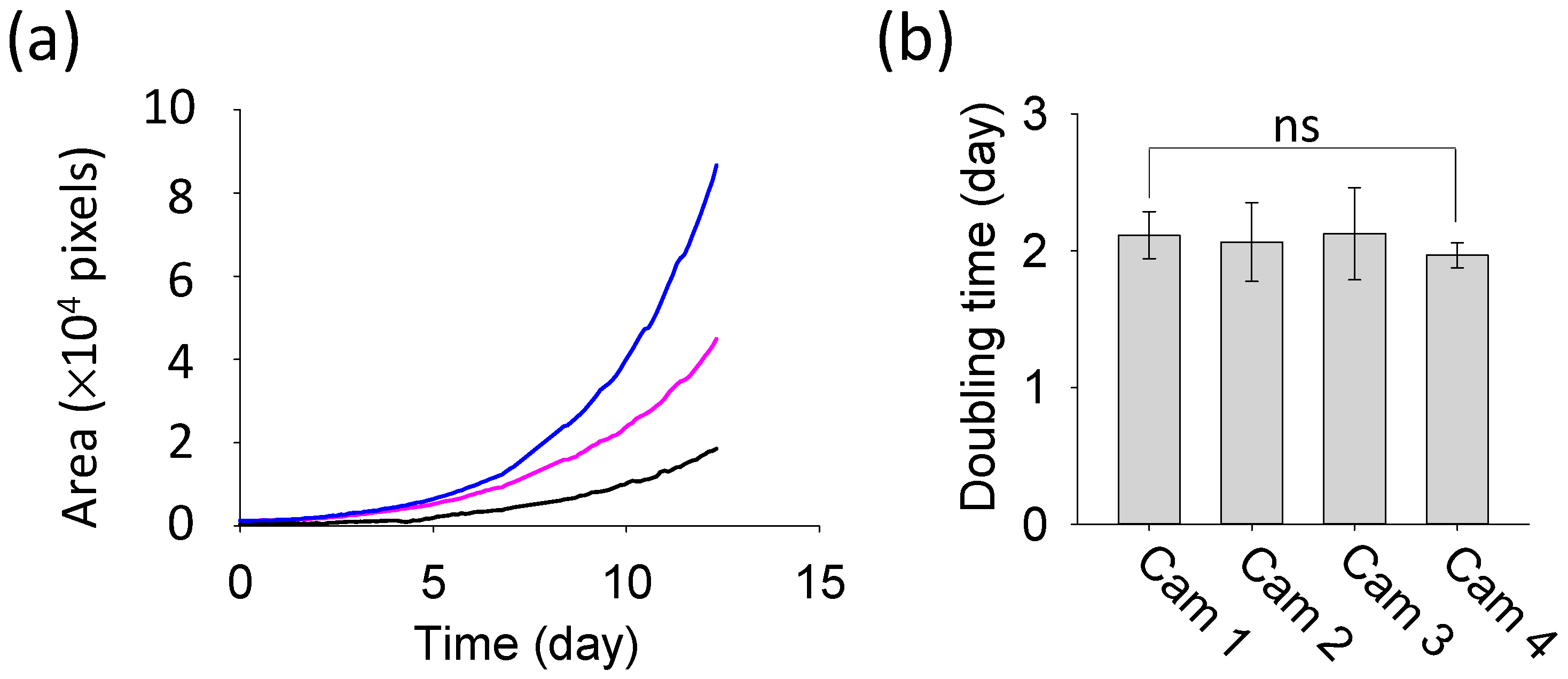

The results of duckweed area quantification, obtained through image analysis, are presented in

Figure 8. Despite differences in the initial area of duckweed, the growth curves from the three plates all exhibited an exponential pattern (R

2 > 0.99) (

Figure 8a). The relative growth rate and doubling time were calculated using the following standard equations, which are widely used in biology to model exponential growth of biomass area [

14,

36,

37,

38]:

where

t represents time (days),

At is the area at time

t (pixels),

At−Δt is the area at the previous time point (pixels), Δ

t is the time interval between consecutive measurements,

Rr is the relative growth rate (1/days), and

Td is the doubling time (days).

Using this method, the average relative growth rate across the twelve plates was calculated as 0.34 ± 0.03 days

−1, and the corresponding doubling time was 2.07 ± 0.22 days (

n = 12 plates). Each camera group consisted of three samples, corresponding to three Petri dishes of cultivated duckweed, and the doubling time values were calculated from the relative growth rate. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis detected no statistically significant differences in doubling time among the four camera groups (

p = 0.849), and both normality and equal-variance assumptions were satisfied (

Figure 8b).

There appear to be no studies that have measured the doubling time under the same conditions using the same species as in this study. However, a relevant study on the growth of 13 duckweed species reported a relative growth rate ranging from 0.15 to 0.52 days

−1 and a doubling time of 1.34 to 4.54 days [

38]. In another study, the doubling times of

Lemna minor and

Lemna gibba cultured in SH media were approximately 2.7 and 3.6 days, respectively [

39]. Since the values obtained from our experiment are similar to these reported values, it is concluded that there are no significant issues with the overall experiment.

The image analysis program employs a tiling-based strategy in which a large image is divided into multiple tiles for segmentation and then reassembled. This approach can potentially introduce artifacts such as visible seams caused by inconsistent predictions across tile boundaries, partial truncation of objects located near tile edges, and context loss resulting from limited receptive fields. Additional padding artifacts may also occur when tiles extend beyond the image boundary and require zero-padding. To mitigate these issues, we use a 64-pixel overlap between adjacent tiles and apply a weight-map–based blending scheme during tile reassembly. This strategy effectively suppresses tile-edge artifacts, making them difficult to identify even in processed images such as those presented in

Figure 7.

Meanwhile, the spatial resolution of the image acquisition setup used in the illustrative application shown in

Figure 7 was estimated on the camera sensor resolution (1600 × 1200 pixels) and the observed field of view (approximately 173 mm × 130 mm), yielding an effective spatial resolution of approximately 0.11 mm/pixel (≈110 µm/pixel). This resolution is sufficient for capturing the features of interest in the presented application. Notably, the spatial resolution depends on the field of view and thus varies with the distance between the camera and the specimen. Reducing the camera-to-object distance can enhance the spatial resolution, potentially improving the detection of fine details; however, it may also introduce image blur and amplify geometric distortions caused by the wide-angle lens. Therefore, a trade-off exists between achieving higher spatial resolution and maintaining overall image quality, which should be considered when optimizing the imaging setup.

We acknowledge several operational limitations, including the system’s sensitivity to ambient lighting fluctuations and the potential for decreased analytical accuracy when analyzing low-contrast organisms. Although the system has been reliably tested with up to 12 ESP32-CAMs using a single image acquisition program—a number expected to increase further due to the asynchronous sequential triggering strategy—we recognize the inherent risk of network congestion when deploying a larger number of units. In addition, the current image analysis approach does not separate overlapping elements, such as duckweed fronds overlapping each other or duckweed overlapping the Petri dish boundary. Accurately measuring the area of these overlapping elements is expected to further improve the precision of growth quantification and overall analytical accuracy.

Finally, regarding platform compatibility, the image acquisition program was developed in VB.NET and has been validated on Windows OS. The image analysis program was implemented in Python and tested on Windows OS; given Python’s cross-platform nature, it is expected to be compatible with other operating systems, although this has not been empirically verified.

5. Impact

Measuring the growth of living organisms is essential in research and industry, and researchers spend considerable time on this task. Technology that captures images at regular intervals and quantifies growth through image processing saves labor and time, while ensuring rapid, accurate, and reliable analysis. For adoption in research, such technology must be cost-effective, easy to use, customizable, and scalable.

SIPEREA meets these requirements as a free software platform with minimal implementation and operational costs. The ESP32-CAM, equipped with a high-resolution camera, is inexpensive, resulting in low hardware setup costs. SIPEREA’s GUI–based programs enable users to perform time-lapse imaging and batch image processing with just a few clicks, making the system intuitive for researchers.

Traditional imaging methods using wired connections have limited cost-effectiveness and complex setup requirements, especially for large areas or numerous samples. SIPEREA transmits images wirelessly, eliminating installation location restrictions. Multiple ESP32-CAMs can capture images sequentially and transmit them asynchronously. Moreover, for organism area quantification, SIPEREA employs a DNN–based segmentation algorithm instead of conventional binarization methods, allowing for accurate isolation of biological regions from the background.

SIPEREA’s source code is publicly available, allowing users to implement new functions and operations. This open-source availability makes SIPEREA a flexible, customizable, and scalable platform poised for broad adoption by researchers.

While duckweed served as an illustrative example in this study, the platform is readily extendable to other species or even non-biological samples, highlighting its broader applicability.