Analysis of the Travelling Time According to Weather Conditions Using Machine Learning Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Methods and Applications

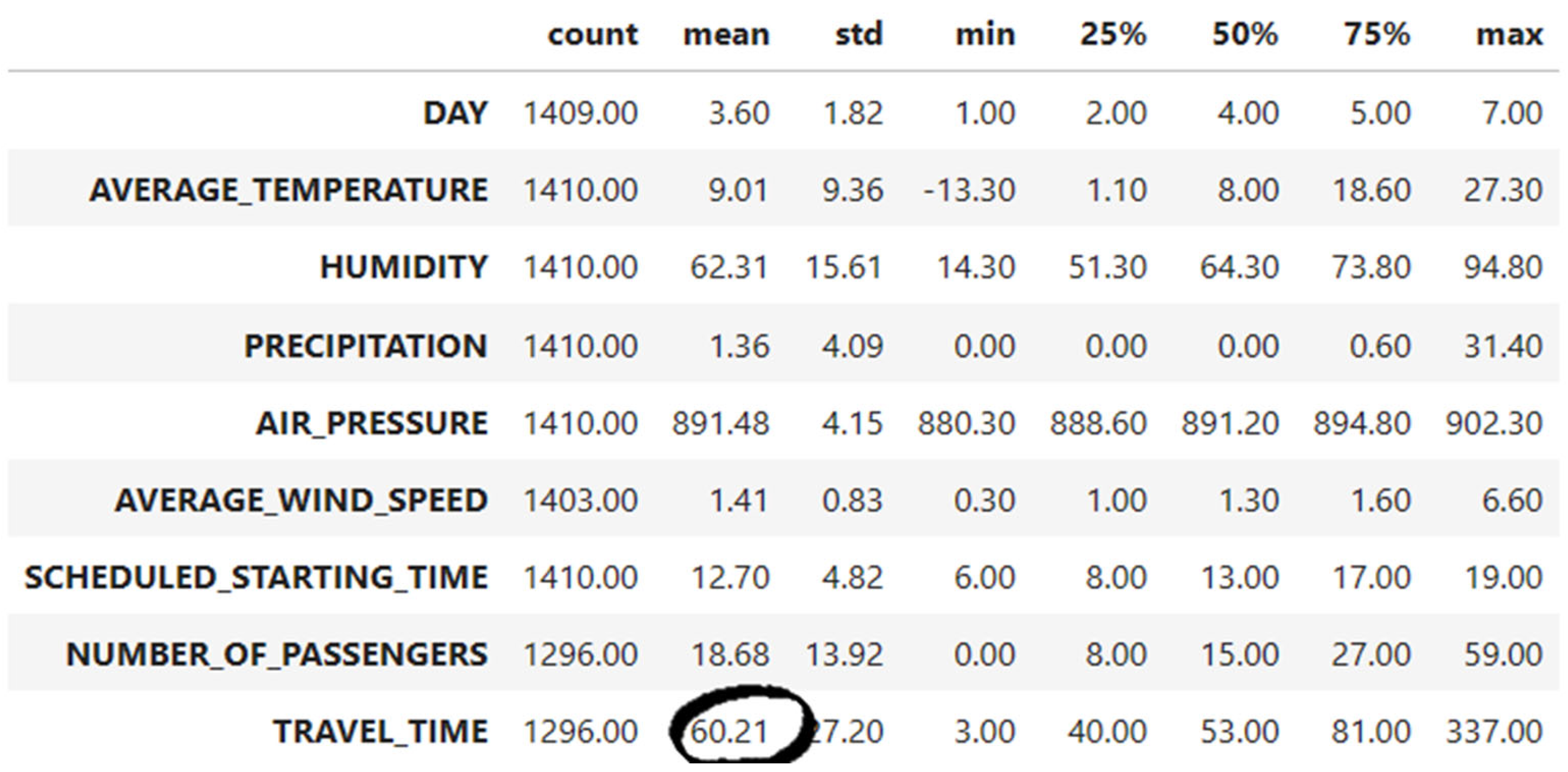

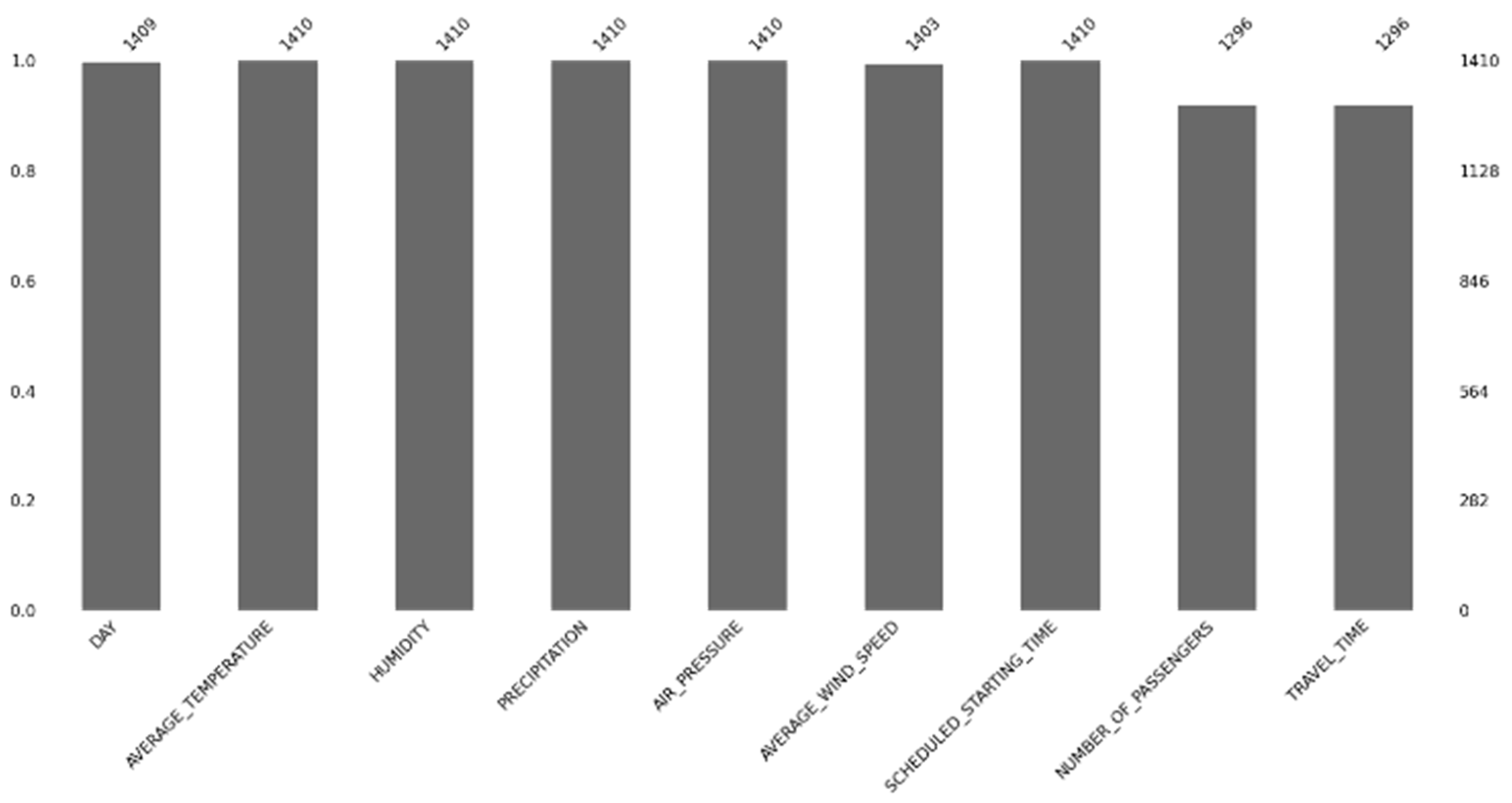

4.1. Data Collecting

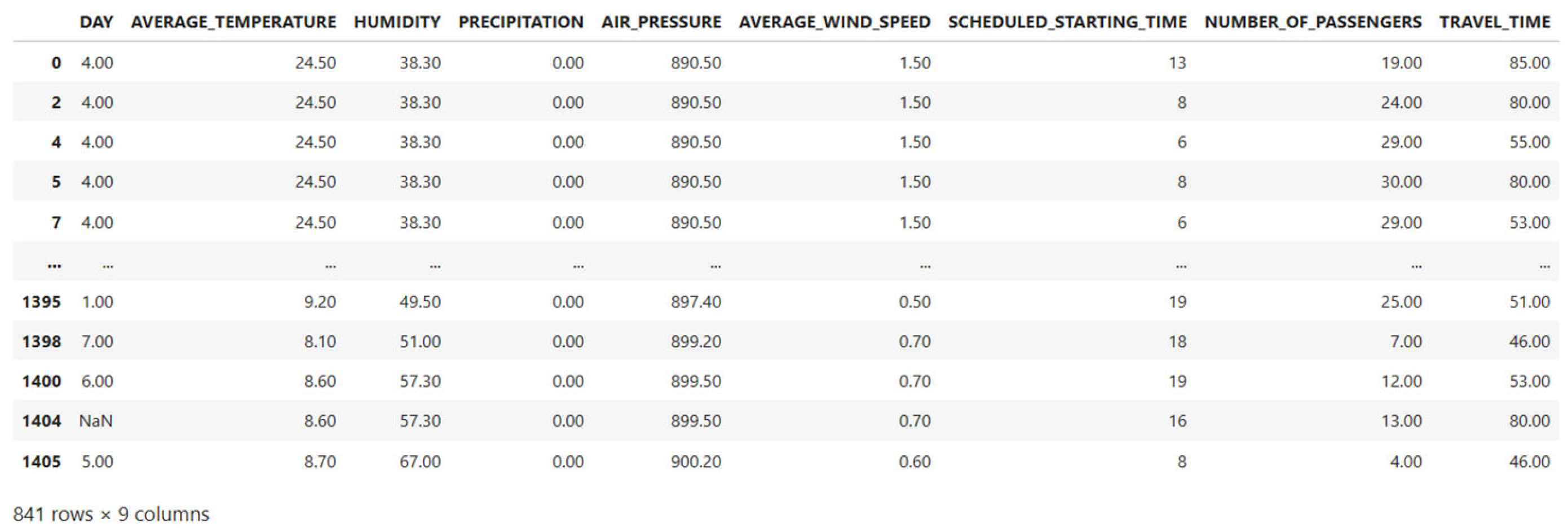

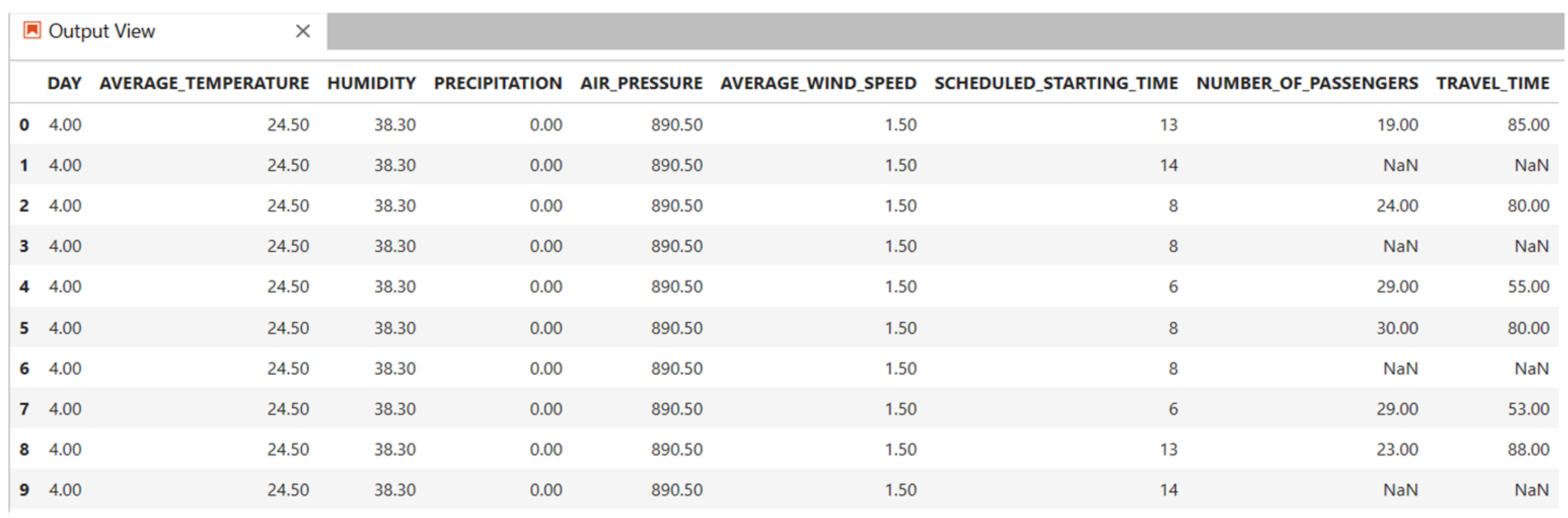

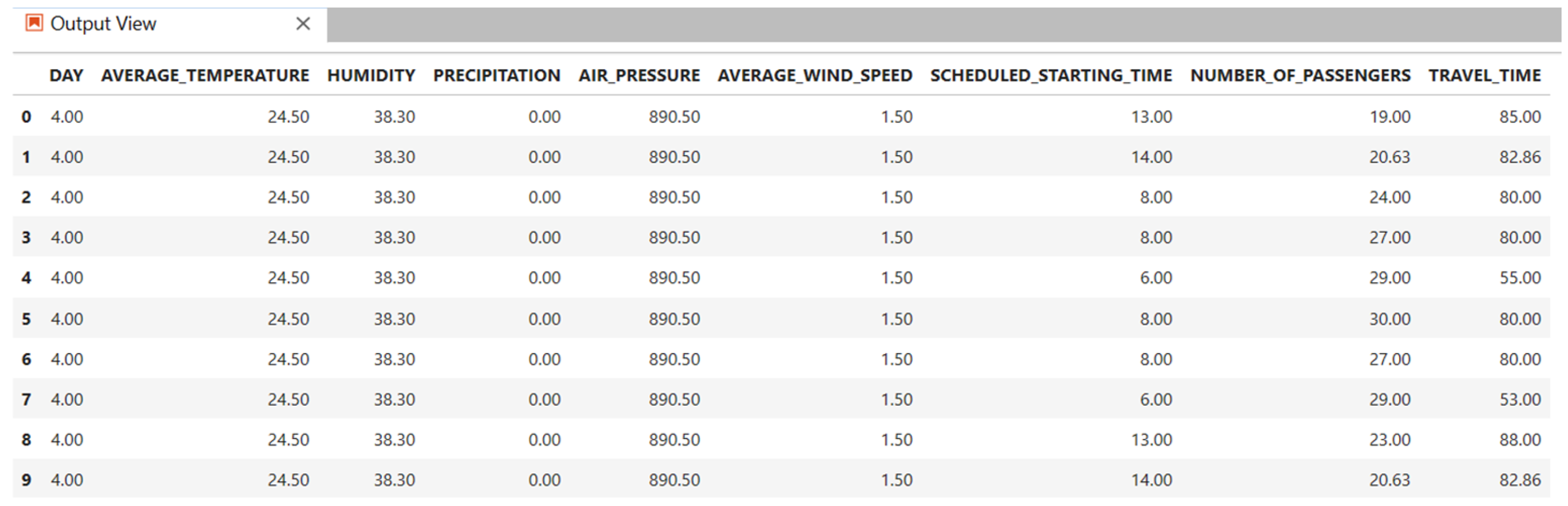

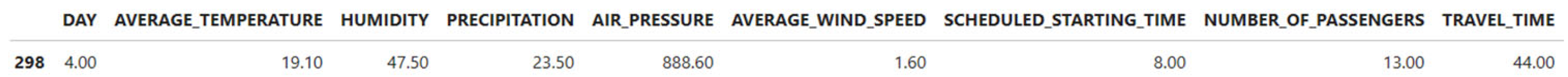

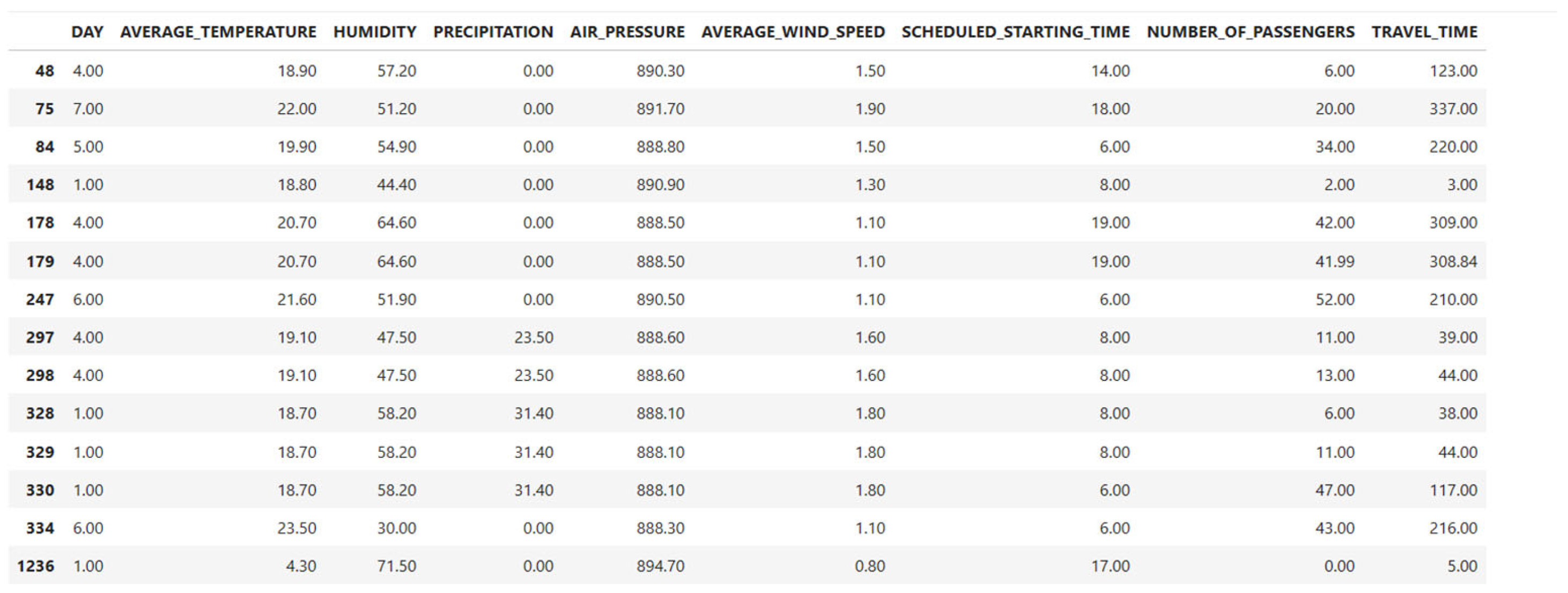

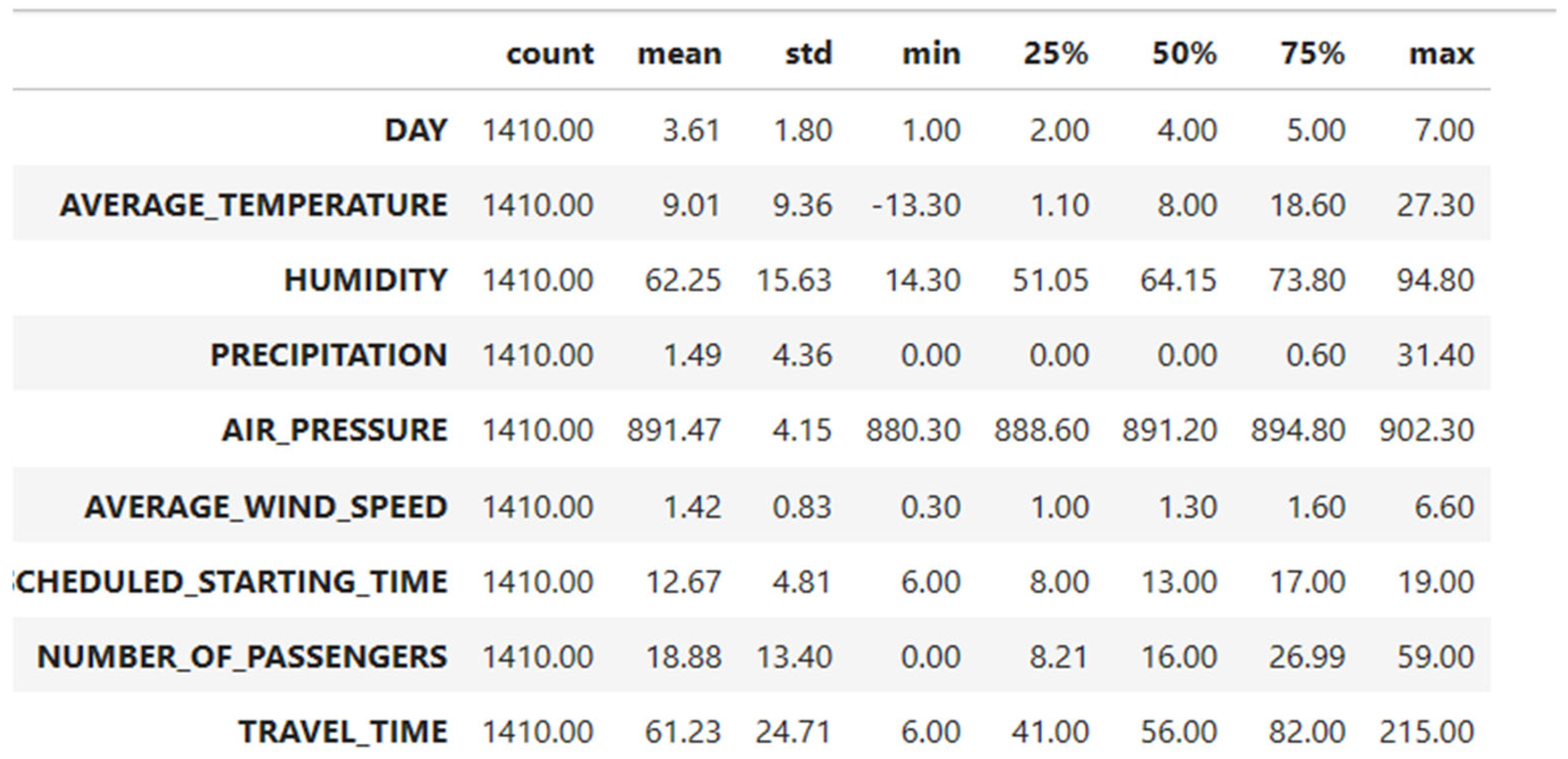

4.2. Data Preprocessing

4.3. Modeling

4.3.1. Regression Models

- Assigning an optimal k value with a fixed expert predefined value for all test samples.

- Assigning different optimal k values for different test samples.

4.3.2. Machine Learning Models

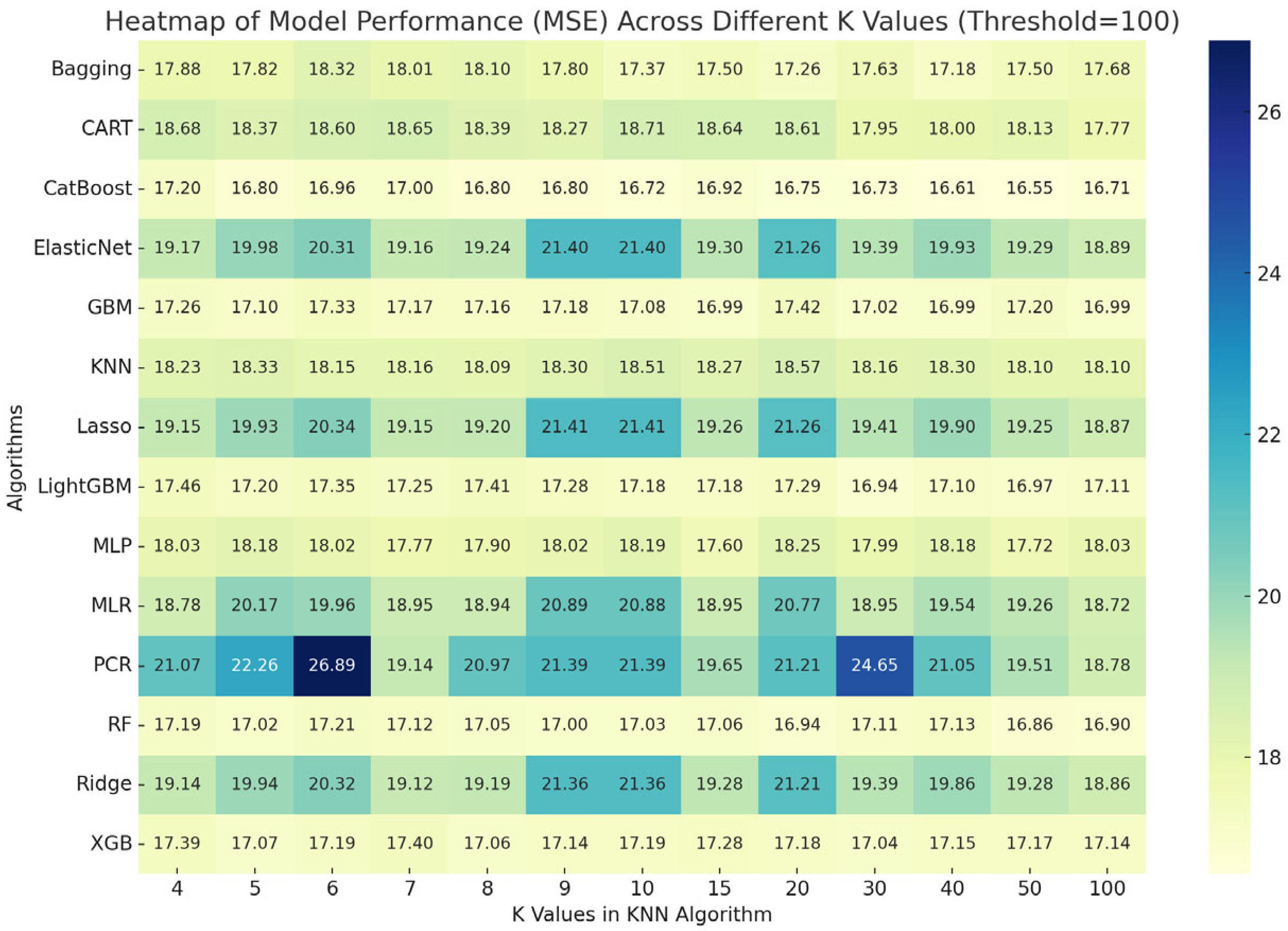

4.3.3. The Applications of Algorithms in Prediction the Travel Time

- -

- KNN: k = 4–8;

- -

- Random forest: n_estimators = 200, max_depth = 10;

- -

- XGBoost: learning_rate = 0.1, n_estimators = 300, max_depth = 8;

- -

- CatBoost: learning_rate = 0.05, depth = 8, iterations = 500;

- -

- MLP: hidden_layer_sizes = (50, 25), activation = ‘relu’, solver = ‘adam’.

4.4. Modeling Evaluation and Model Selection

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARIMA | Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average |

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LOF | Local Outlier Factor |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| PCR | Principal Component Regression |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Serin, F.; Alisan, Y.; Erturkler, M. Predicting bus travel time using machine learning methods with three-layer architecture. Measurement 2022, 198, 111403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, A.; Mandelbaum, A.; Schnitzler, F.; Senderovich, A.; Weidlich, M. Traveling time prediction in scheduled transportation with journey segments. Inf. Syst. 2017, 64, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Pereira, F.C. Multi-output bus travel time prediction with convolutional LSTM neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 120, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Peng, Z.R.; Lu, Q.C.; Sun, J. Dynamic bus travel time prediction models on roaad with multiple bus routes. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treethidtaphat, W.; Atikom, W.P.; Khaimook, S. Bus Arrival Time Prediction at Any Distance of Bus Route Using Deep Neural Network Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC): Workshop, Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 October 2017; pp. 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Chiang, H.S.; Yang, K.J. Constructing cooperative intelligent transport systems for travel time prediction with deep learning approaches. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16590–16599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, B.P.; Sumathi, R.; Sudhira, H.S. Bus Travel Time Prediction: A Comparative Study of Linear and Non-Linear Machine Learning Models. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2161, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servos, N.; Liu, X.; Teucke, M.; Freitag, F. Travel Time Prediction in a Multimodal Freight Travel Time Prediction in a Multimodal Freight Learning Algorithms. Logistics 2020, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H.; Özcan, T. Optimization of Service Frequencies in Bus Networks with Harmony Search Algorithm: An Application on Mandl's Tet Network. Pamukkale Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2018, 24, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.K.; Kumar, B.; Vanajakshi, L. Bus travel time prediction under high variability conditions. Curr. Sci. 2016, 111, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossavi, S.M.H.; Aghaabbasi, M.; Yuen, C.W. Evaluation of Applicability and Accuracy of Bus Travel Time Prediction in High and Low Frequency Bus Routes Using Tree-Based ML Techniques. J. Soft Comput. Civ. Eng. 2023, 7, 74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Cai, C. Towards Attention-Based Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory for Travel Time Prediction of Bus Journeys. Sensors 2020, 20, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Choo, S.; Choi, S.; Lee, H. Does the Inclusion of Spatio-Temporal Feature Improve Bus Travel Time Predictions? A Deep Learning-Based Modelling Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Jiang, G.; Lam, S.K.; Tang, D. Travel-Time Prediction of Bus Journey with Multiple Bus Trips. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 4192–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, B.; Ertuğrul, İ. Çoklu Regresyon, ARIMA ve Yapay Sinir Ağı Yöntemleri ile Türkiye Elektrik Piyasasında Fiyat Tahmin ve Analizi. Yönetim Ve Ekon. Araştırmaları Derg. 2022, 20, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumo, N.; Biswas, M. Regression analysis for prediction of residential energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Topal, E. Optimizing overbreak prediction based on geological parameters comparing multiple regression analysis and artificial neural network. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2013, 38, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Cripps, A. Predicting Housing Value: A Comparison of Multiple Regression Analysis and Artificial Neural Networks. J. Real Estate Res. 2021, 22, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, F.M.; Gamel, S.A. Predicting the impact of no. of authors on no. of citations of research publications based on neural networks. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022, 14, 8499–8509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Duan, X. Predicting of Gasoline Reseach Octane Number Using Multiple Feature Machine Learning Models. Fuel 2023, 333, 126510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, G.; Orsolini, G.; Fassio, A.; Viapiana, O.; Sorio, E.; Benini, C.; Gatti, D.; Bertelle, D.; Rossini, M. POS0474 Factırs Associated with Erosive Rheumatoid Arthritis, A Multimarker Principal Component analysis (PCA) and Principal Component Regression (PCR) Analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 497–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Yang, C.; Wan, Z. A Comparative Regression Analysis between Principal Component and Partial Least Squares Methods for Flight Load Calculation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, M.; Ardhyatirta, R.; Angelina, S.G.; Ohyver, M. Predict Farmer Exchange Rate in the Food Crop Sector Using Principal Component Regression. Enthusiastic Int. J. Appl. Stat. Data Sci. 2023, 3, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, D.; Dastidar, S.G.; Akram, W.; Guchhait, S.; Jana, S.N.; Banerjee, S.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Bandyopadhyay, R. A Comparative Study Between Partial Least Squares and Principal Component Regression for Nondestructive Quantification of Piperine Contents in Black Pepper by Raman Spectroscopy. In Smart Sensors Measurement and Instrumentation; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, A.; Ilyas, M. Robust Correlation Scaled Principal Component Regression. Hacet. J. Math. Stat. 2023, 52, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettink, A.; Chinapaw, M.; Wieringen, W.N. Two-Dimensional Fused Targeted Ridge Regression for Health Indicator Prediction From Accelerometer Data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2023, 72, 1064–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, O.; Nasseri, M.; Zahraie, B. A Locally Weighted Linear Ridge Regression Framework for Spatial Interpolation of Monthly Precipitation over an Orographically Complex Area. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 2601–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, W.; Yao, J.; Jiao, C.; Romero, A.; Rodriguez, T.; Hergert, H. Optimization of the generator coordinate method with machine-learning techniques for nuclear spectra and neutrinoless double- β decay: Ridge regression for nuclei with axial deformation. Pyhsical Rev. C Cover. Nucl. Phys. 2023, 107, 024304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ge, Y.; Muhsen, S.; Wang, S.; Elkamchouchi, D.H.; Ali, E.; Ali, H. New Ridge Regression, Artificial Neural Networks and Support Vector Machine for Wind Speed Prediction. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2023, 179, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Chen, J.; Ma, L.; Zhag, L.; He, S.; Du, G.; Wang, J. Research on a Working Face Gas Concentration Prediction Model Based on LASS_RNN time Series Data. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Song, N. Carbon Price Combination Forecasting Model Based on Lasso Regression And Optimal Integration. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Gupta, N.; Verma, M. Prediction of Compressive Strength of GGBFS and Flyash-based Geopolymer Composite by Linear Regression, Lasso Regression, and Ridge Regression. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 24, 3399–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didari, S.; Talebnejad, R.; Bahrami, M.; Mahmoudi, M.R. Dryland Farming Wheat Yield Prediction Using the Lasso Regression Model and Meteorological Variables in Dry and Semi-dry Region. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 3967–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, S.; Gallego, S.R.; Luengo, J.; Benitez, J.M.; Herrera, F. Big Data Preprocessing: Methods and Prospects. Big Data Anal. 2016, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Upadhyaya, S. Outlier Detection: Applications and Techniques. Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2012, 9, 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Taylor, J.; Tibshirani, R.; Walther, G. Forward Stagewise Regression and The Monotone Lasso. Electron. J. Stat. 2007, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, C. Elastic Net Regression Modeling with the Orthant Normal Prior. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011, 106, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Zong, M.; Zhu, X. Learning k for kNN Classification. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, B. Machine Learning Algorithms-A Review. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 9, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Ziapour, B.M.; Shokri, A.; Shakibi, H.; Sobhani, B. Building energy consumption prediction using multilayer perceptron neural network-assisted models; comparison of different optimization algorithms. Energy 2023, 282, 128446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, M.; Peker, S. Classification and regression tree algorithm for heart disease modeling and prediction. Helathcare Anal. 2023, 3, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kori, G.S.; Kakkasageri, M.S. Classification and regression tree (CART) based resource allocation scheme for wireless sensor networks. Comput. Commun. 2023, 197, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J. An Introduction to Classification and Regression Tree (CART) Analysis. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–25 May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karthan, M.K.; Kumar, P.N. Prediction of IRNSS User Position using Regression Algorithms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Intelligence for GeoAnalytics and Remote Sensing, Hyderabad, India, 27–29 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic, D.; Jeromela, A.M.; Pezo, L.; Loncar, B.; Grahovac, N.; Spika, A.K. Artificial neural network and random forest regression models for modelling fatty acid and tocopherol content in oil of winter rapeseed. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, A.Y.; Sasipraba, T. Flood Detection Using Gradient Boost Machne Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Knowledge Economy (ICCIKE), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 11–12 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Yun, S.; Meng, Y.; He, N.; Ye, D.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, L.; Yang, L. Prediction of heating and cooling loads based on light gradient boosting machine algorithms. Build. Environ. 2023, 236, 110252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.H.; Burhan, A.M. Hybrid machine learning approach for construction cost estimation: An evaluation of extreme gradient boosting model. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 24, 2427–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Methods | Main Conclusion/Weakness |

|---|---|---|

| Serin vd. [1] | AdaBoost Regression, Gradient Boosted Regression, Random Forest Regression, Extra-Tree Regression, KNN Regression, Support Vector Machine | Ensemble learning achieved higher accuracy than single algorithms, but no environmental or meteorological variables were included. |

| Gal vd. [2] | Queueing Theory, Machine Learning | Proposed a hybrid queueing-ML model improving predictive reliability; however, weather effects and external disturbances were not considered. |

| Peterson vd. [3] | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Network | Captured temporal and spatial dependencies effectively; interpretability was limited, and environmental variables were excluded. |

| Bai vd. [4] | Support Vector Machines, Kalman Filtering | Combined SVM and Kalman filter for dynamic prediction; effective for real-time data but sensitive to noise and parameter tuning. |

| Treethidtaphat vd. [5] | Deep Neural Network, Ordinary Least Square (OLS) Regression | DNN outperformed OLS in travel time prediction, yet the model required large datasets and lacked contextual (e.g., weather) factors. |

| Chen vd. [6] | Linear Regression, The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator, K-Nearest Neighbors Regression, Support Vector Regression, Gradient Boosting Regression, The Long Short Term Memory Network, Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory, Seasonal Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average | Comprehensive comparison of multiple ML and statistical models; improved accuracy but ignored environmental influence and interpretability. |

| Ashwini et al. [7] | Linear Regression, Ridge Regression, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator Regression, Support Vector Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors, Regression Trees, Random Forest Regression, Gradient Boosting Regression | Showed temporal and route-direction variables improve performance; however, no weather or external conditions were included. |

| Servos et al. [8] | Extremely Randomized Trees, Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Ensemble algorithms outperformed mean-based approaches; dataset limited to freight transport and lacked meteorological diversity. |

| Ceylan and Özcan [9] | Optimized bus frequencies using a meta-heuristic algorithm; not a predictive model and did not assess real-time variability. | |

| Reddy et al. [10] | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | SVR improved prediction under variable traffic conditions; applicability restricted by small-scale data and absence of weather inputs. |

| Moosavi et al. [11] | Chi-Square Automatic Interaction Detection, Random Forest, Gradient Boost Tree | Tree-based methods performed well across routes with differing frequencies; however, interpretability remained limited. |

| Wu et al. [12] | ConvLSTM, LSTM | Integrated convolutional and recurrent structures enhanced temporal precision; required high computational cost and excluded weather factors. |

| Lee et al. [13] | ConvLSTM | Utilized spatio-temporal features for improved prediction; model complexity hindered practical deployment, and no environmental inputs were used. |

| He et al. [14] | Interval-Based Historical Average Model, The Long Short Term Memory Network | Separated riding and waiting times for greater granularity; still limited by small-scale experiments and no weather analysis. |

| Authors | Methods | Subject | Main Conclusion/Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arslan and Ertuğrul [15] | Multiple Regression Models, Artificial Neural Networks Models | Electricity Consumption | Compared to regression and ANN; ANN achieved better fit but model lacked robustness for non-linear volatility. |

| Fumo and Biswas [16] | Simple Linear Regression Model, Multiple Linear Regression Model | Energy Consumption | Regression captured linear dependence on temperature; ignored nonlinearity and multivariable interaction. |

| Jang et al. [17] | Linear Multiple Regression, Nonlinear Multiple Regression, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Geological Parameters | ANN performed better than regression for complex relationships; interpretability was weak. |

| Nguyen and Cripps [18] | Multiple Regression Models, Artificial Neural Networks Models | House Sales | ANN outperformed regression; however, limited transparency and potential overfitting noted. |

| Talaat and Gamel [19] | Correlation Coefficient, Multiple Linear Regression | No. of Authors and No. of Citations | Found strong correlation between authorship and citation; regression model lacked causal interpretation. |

| Sun et al. [20] | Random Forest Algorithm | Research Octane Number | RF effectively modeled nonlinear fuel properties; dataset domain-specific, limiting generalizability. |

| Adami et al. [21] | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Principal Component Regression (PCR) | Rheumatoid Arthritis | PCA/PCR identified key clinical factors; medical focus unrelated to transport forecasting. |

| Yan et al. [22] | Principal Component Regression, Partial Least Squares Regression | Flight Load Analysis | Demonstrated efficiency in handling multicollinearity; limited transferability to dynamic datasets. |

| Effendi et al. [23] | Principal Component Regression | Farmer Exchange Rate | Showed PCR’s strength in dimensionality reduction; agricultural data context only. |

| Sing et al. [24] | Principal Component Regression, Partial Least Squares Regression | Piperine Contents in Black Pepper | Compared regression methods for spectroscopy; not focused on time-dependent prediction. |

| Tahir and Ilyas [25] | Robust Correlation-Based Regression, Robust Correlation Scaled Principal Regression | Proposed robust approach for high-dimensional data; computationally heavy and untested in forecasting. | |

| Lettink et al. [26] | Ridge Regression | Health Indicator | Ridge regression reduced overfitting; performance limited by small sample. |

| Zandi et al. [27] | Locally Weighted Linear Regression Method | Three Large-Scale Precipitation Products | Achieved high spatial accuracy; model sensitive to regularization parameter. |

| Zhang et al. [28] | Polynomial Ridge Regression (RR) Algorithm | Atomic Nuclei | Efficient for physics-based prediction; domain-specific with limited cross-field relevance. |

| Zheng et al. [29] | Kernel Ridge Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | Wind Speed | Kernel methods showed lowest error; required careful kernel tuning and large data. |

| Song et al. [30] | Lasso Regression, Long Short-Term Memory Model (LSTM) | Gas Concentration | Lasso improved variable selection; LSTM achieved higher accuracy but at higher complexity. |

| Li et al. [31] | Lasso Regression, ARIMA, NARNN, LSTM | Carbon Price | Combined classical and deep models; limited by temporal instability of financial data. |

| Sharma et al. [32] | Linear Regression, Lasso Regression, Ridge Regression | Strength of GGBFS | Regression performed well; lacks external validation and generalizability. |

| Didari et al. [33] | Lasso Regression | Wheat Yield | Identified key meteorological variables; effective locally but not tested on larger datasets. |

| Malakouti [34] | Lasso Regression, Elastic Net Algorithms | Carbon Dioxide | Elastic net provided stable results; small dataset constrained robustness assessment. |

| Variables | Definitions |

|---|---|

| DAY | Shows the days of the week. 1: Monday, 2: Tuesday, 3: Wednesday, 4: Thursday, 5: Friday, 6: Saturday, 7: Sunday. |

| AVERAGE_TEMPERATURE | Shows the average temperature during the day. |

| HUMIDITY | Shows the humidity rate during the day. |

| PRECIPITATION | Shows the amount of precipitation per square meter during the day. |

| AIR_PRESSURE | Shows the air pressure. |

| AVERAGE_WIND_SPEED | Shows the average wind speed during the day. |

| SCHEDULED_STARTING_TIME | Shows the bus departure time scheduled by the transportation company. |

| NUMBER_OF_PASSENGERS | Shows the number of passengers who boarded the bus on the specified expedition. |

| K Values | Threshold Value | Multiple Linear Regression | Principal Component Regression | Ridge Regression | Lasso Regression | Elastic Net Regression | K-Nearest Neighbors | Multilayer Perceptron | Classification and Regression Tree | Bagging Trees Regression | Random Forest Regression | Gradient Boost Machine | Xgboost Regression | Light GBM | Catboost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 10 | 25.10 | 26.47 | 26.44 | 26.42 | 26.46 | 26.26 | 24.06 | 24.11 | 23.12 | 22.95 | 23.19 | 23.90 | 23.84 | 22.39 |

| 4 | 20 | 21.57 | 23.12 | 22.71 | 22.73 | 22.73 | 20.41 | 20.51 | 21.07 | 19.68 | 19.12 | 19.13 | 19.51 | 19.43 | 18.86 |

| 4 | 30 | 21.66 | 22.10 | 22.44 | 22.50 | 22.44 | 20.56 | 18.86 | 20.31 | 18.50 | 17.86 | 18.11 | 18.26 | 18.37 | 17.73 |

| 4 | 50 | 19.13 | 20.04 | 19.77 | 19.79 | 19.83 | 18.96 | 18.57 | 19.45 | 18.65 | 17.83 | 17.89 | 18.05 | 18.07 | 17.62 |

| 4 | 100 | 18.78 | 21.07 | 19.14 | 19.15 | 19.17 | 18.23 | 18.03 | 18.68 | 17.88 | 17.19 | 17.26 | 17.39 | 17.46 | 17.20 |

| K Values | Threshold Value | Multiple Linear Regression | Principal Component Regression | Ridge Regression | Lasso Regression | Elastic Net Regression | K-Nearest Neighbors | Multilayer Perceptron | Classification and Regression Tree | Bagging Trees Regression | Random Forest Regression | Gradient Boost Machine | Xgboost Regression | Light GBM | Catboost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 10 | 22.70 | 25.79 | 25.15 | 25.17 | 25.14 | 25.27 | 24.20 | 23.25 | 23.24 | 23.03 | 22.88 | 23.96 | 23.35 | 22.52 |

| 5 | 20 | 20.24 | 25.14 | 21.60 | 21.62 | 21.63 | 20.47 | 20.66 | 20.93 | 20.08 | 19.27 | 19.44 | 19.60 | 19.65 | 19.09 |

| 5 | 30 | 20.01 | 21.62 | 20.52 | 20.50 | 20.54 | 19.70 | 18.64 | 19.27 | 18.67 | 17.84 | 17.96 | 17.83 | 17.99 | 17.95 |

| 5 | 50 | 20.81 | 21.77 | 21.33 | 21.29 | 21.36 | 19.21 | 18.44 | 19.33 | 18.64 | 17.86 | 18.05 | 18.09 | 18.05 | 17.59 |

| 5 | 100 | 20.17 | 22.26 | 19.94 | 19.93 | 19.98 | 18.33 | 18.18 | 18.37 | 17.82 | 17.02 | 17.10 | 17.07 | 17.20 | 16.80 |

| K Values | Threshold Value | Multiple Linear Regression | Principal Component Regression | Ridge Regression | Lasso Regression | Elastic Net Regression | K-Nearest Neighbors | Multilayer Perceptron | Classification and Regression Tree | Bagging Trees Regression | Random Forest Regression | Gradient Boost Machine | Xgboost Regression | Light GBM | Catboost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 100 | 18.7758 | 21.0668 | 19.1381 | 19.1539 | 19.1665 | 18.2300 | 18.0274 | 18.6750 | 17.8805 | 17.1935 | 17.2576 | 17.3929 | 17.4580 | 17.1993 |

| 5 | 100 | 20.1716 | 22.2621 | 19.9354 | 19.9318 | 19.9821 | 18.3324 | 18.1830 | 18.3747 | 17.8195 | 17.0247 | 17.1034 | 17.0672 | 17.1977 | 16.7975 |

| 6 | 100 | 19.9567 | 26.8876 | 20.3238 | 20.3413 | 20.3111 | 18.1531 | 18.0175 | 18.6016 | 18.3199 | 17.2081 | 17.3279 | 17.1931 | 17.3498 | 16.9579 |

| 7 | 100 | 18.9454 | 19.1356 | 19.1208 | 19.147 | 19.1613 | 18.1592 | 17.7727 | 18.6512 | 18.0104 | 17.1203 | 17.1721 | 17.3995 | 17.2529 | 16.9975 |

| 8 | 100 | 18.9375 | 20.9714 | 19.1898 | 19.2011 | 19.2376 | 18.0917 | 17.8998 | 18.3897 | 18.1027 | 17.0496 | 17.1558 | 17.0621 | 17.4066 | 16.7994 |

| 9 | 100 | 20.8862 | 21.3898 | 21.3553 | 21.4084 | 21.3990 | 18.3022 | 18.0237 | 18.2731 | 17.8038 | 16.9951 | 17.1753 | 17.1409 | 17.2827 | 16.7951 |

| 10 | 100 | 20.8755 | 21.3905 | 21.3571 | 21.4095 | 21.3993 | 18.5103 | 18.1871 | 18.7065 | 17.3708 | 17.0292 | 17.0780 | 17.1868 | 17.1771 | 16.722 |

| 15 | 100 | 18.9470 | 19.6539 | 19.2751 | 19.2633 | 19.2960 | 18.2728 | 17.5958 | 18.6351 | 17.4969 | 17.0611 | 16.9917 | 17.2837 | 17.1807 | 16.9158 |

| 20 | 100 | 20.7664 | 21.2142 | 21.2089 | 21.2622 | 21.2595 | 18.5742 | 18.2516 | 18.6117 | 17.2602 | 16.9403 | 17.4187 | 17.179 | 17.2928 | 16.7505 |

| 30 | 100 | 18.9485 | 24.6539 | 19.3945 | 19.4052 | 19.3943 | 18.1641 | 17.9939 | 17.9480 | 17.6267 | 17.1106 | 17.0197 | 17.0441 | 16.9391 | 16.7295 |

| 40 | 100 | 19.5432 | 21.0539 | 19.8611 | 19.8998 | 19.9326 | 18.3028 | 18.176 | 18.0005 | 17.1836 | 17.1334 | 16.9885 | 17.1486 | 17.1024 | 16.6134 |

| 50 | 100 | 19.2573 | 19.5114 | 19.2834 | 19.2550 | 19.2904 | 18.1027 | 17.7176 | 18.1323 | 17.5025 | 16.8580 | 17.1984 | 17.1723 | 16.9679 | 16.5454 |

| 100 | 100 | 18.7193 | 18.7824 | 18.8567 | 18.8676 | 18.8943 | 18.0978 | 18.0318 | 17.7718 | 17.6758 | 16.9005 | 16.9857 | 17.1425 | 17.1054 | 16.7129 |

| Hypothesis | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Null hypothesis | H0: All treatment effects are zero | |

| Alternative hypothesis | H1: Not all treatment effects are zero | |

| DF | Chi-Square | p-Value |

| 12 | 148.54 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Canbulut, G. Analysis of the Travelling Time According to Weather Conditions Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010006

Canbulut G. Analysis of the Travelling Time According to Weather Conditions Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanbulut, Gülçin. 2026. "Analysis of the Travelling Time According to Weather Conditions Using Machine Learning Algorithms" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010006

APA StyleCanbulut, G. (2026). Analysis of the Travelling Time According to Weather Conditions Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010006