1. Introduction

Buildings extracted from high-resolution remote sensing imagery provide fundamental information for characterizing the human-built environment from local to global scales. Building maps are essential for various geospatial applications, including urban change monitoring, disaster management, map updating, and smart city development. Recent deep learning-based building segmentation methods have demonstrated strong performance on various benchmark datasets. However, models trained on specific regions or sensors often suffer from substantial performance degradation when applied to images from different regions, sensors, or acquisition conditions. Cross-domain building segmentation, which seeks to maintain consistent performance under such domain shifts, therefore remains a core challenge in the field of remote sensing, and the demand for robust automatic extraction of reliable building information from high-resolution imagery continues to grow.

Recent work in change detection and map updating has introduced fully transformer-based U-Net frameworks [

1] that integrate aerial imagery, digital surface models (DSMs), and vector information; self-supervised models that jointly address change detection and damage assessment; and compressed-sensing-based strategies that reduce feature dimensionality for efficient map updating [

2,

3,

4]. Complementary studies have also proposed fusion models combining GIS maps and high-resolution satellite images to generate accurate building outline information, as well as automatic building-outline extraction pipelines for large-scale map processing [

5,

6]. Building semantic segmentation further plays a critical role in disaster response by enabling rapid mapping of the spatial distribution of damaged buildings and supporting timely damage assessment across diverse scenarios [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. In urban planning and smart city applications, its value for urban analysis, urban management, and planning decision-making has been demonstrated through GIS-based high-precision building-outline generation frameworks, building footprints derived from LiDAR and very-high-resolution (VHR) imagery, and segmentation models designed for complex backgrounds [

5,

14,

15].

However, building segmentation models typically perform best when the target dataset is statistically similar to the training data. When the target dataset differs from the training dataset in sensor type, acquisition time, season, weather conditions, or other factors, performance often deteriorates due to domain gaps between source and target distributions; this issue is amplified in satellite and aerial imagery, where building shape, scale, and materials vary substantially across regions. Domain adaptation aims to improve target-domain performance by reducing these distributional differences between a labeled source domain and an unlabeled target domain.

In remote sensing semantic segmentation, Yu et al. categorized domain adaptation methods into discrepancy-based, adversarial, and pseudo-label/self-training approaches [

16]. Discrepancy-based methods compensate for cross-domain differences in class distribution and class sets via distribution matching and clustering strategies, or by identifying common, additional, and missing classes [

17,

18]. Adversarial approaches use discriminators and generative adversarial networks (GANs) to align global and class-specific distributions in feature and output spaces, and have been applied to maintain structural consistency and reduce inter-city domain gaps through output-space alignment, multi-stage adversarial learning, and scale-aware discrimination [

19,

20,

21]. Related GAN-based domain adaptation studies have improved segmentation and cloud detection performance by mitigating spectral and resolution differences between cities and sensors through frequency–space transformation, color–spectrum mapping, semantic-label-based reconstruction, and cycle-consistent style transformation [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Finally, pseudo-labeling and self-training strategies exploit target-domain predictions to improve generalization under high class asymmetry and inter-city domain heterogeneity, including multi-source knowledge integration, dynamic co-learning frameworks, and image-level weakly supervised domain adaptation [

27,

28,

29].

These domain adaptation studies have made significant progress in reducing domain gaps. They do so by minimizing distributional mismatch, aligning styles and features through adversarial learning, and leveraging self-training with pseudo-labels and weak supervision. Nevertheless, many approaches still rely primarily on image-level statistics or style alignment. As a result, structural (geometric) differences—such as building shape, size, and density—are often handled only implicitly, even though they can vary substantially with geographic region, sensor type, and acquisition conditions [

16,

17,

18]. Pixel-level style transfer and related adversarial frameworks (e.g., CycleGAN- or ColorMapGAN-based methods) can effectively mitigate texture differences. However, several studies report that these methods may distort building boundaries or roof structures during training [

23,

25]. Pseudo-labeling and self-learning techniques help alleviate the lack of target-domain labels. Yet, when the domain gap is large, pseudo-label errors can accumulate during iterative training, and class asymmetry or background semantic shifts can further degrade performance [

27,

30,

31,

32]. Moreover, remote sensing imagery exhibits wide geographic, seasonal, and sensor diversity. This diversity makes it difficult to sufficiently represent shifts in broader scene context, such as land-cover patterns and backgrounds, using a single alignment mechanism [

28,

32,

33]. Finally, many studies emphasize aggregate metrics such as mean intersection-over-union (mIoU) and F1-score. In contrast, relatively few provide interpretive analyses that explain how specific domain mismatches (e.g., color, structure, and context) relate to performance changes [

16,

34].

Given the limitations of existing domain adaptation studies, building segmentation in remote sensing requires a data-centric strategy that can simultaneously address (i) geometric diversity (e.g., building shape, area, layout, and orientation) and (ii) radiometric characteristics (illumination and color). This need arises because, when the region, sensor, or imaging conditions change, variations in building structure and background scene context occur together, making it difficult for simple style-transfer or feature-alignment schemes alone to capture such multidimensional domain shifts.

To better cope with structural discrepancies, object-based augmentation (OBA) has been explored as a way to directly expand structural diversity by manipulating training samples. Prior work has reported that synthesizing extracted objects onto diverse backgrounds, cut-and-paste operations, and adversarial instance insertion can improve performance in semantic segmentation and building change detection tasks [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In addition, the effects of combining geometric and photometric augmentations have been examined for SAR-based building footprint segmentation [

40]. However, most OBA-oriented studies primarily expand object distributions within a single sensor and region, which limits their ability to reduce domain gaps or explicitly interpret coupled changes in structure and scene context under cross-domain settings with different sensors, regions, and imaging conditions.

In parallel, histogram- or statistics-based normalization provides a simple yet effective data-driven approach for mitigating domain shift by directly aligning pixel-intensity distributions. Examples such as randomized histogram matching, multi-center/multi-vendor histogram matching, photometric alignment, and class-wise histogram matching suggest that global- or class-level statistical alignment can reduce performance degradation across sensors and scenes [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Nonetheless, these techniques largely focus on source-to-target radiometric alignment and do not explicitly integrate object-level synthetic sampling to jointly bridge structural and radiometric gaps.

Based on this motivation, this study proposes Hybrid OBA–HM, a hybrid framework that combines OBA (to expand object-level structural diversity) with histogram matching (HM) (to perform global radiometric normalization). The proposed approach aims to simultaneously reduce inter-domain differences in luminance/color and geometry. To minimize structural distortion and mitigate side effects of global transformations often observed in GAN-based style transfer or feature-alignment-based adaptation, the method analyzes statistical characteristics of building objects and backgrounds separately, while applying the final radiometric transformation at the entire-image level.

Existing object-based augmentation methods expand the distribution of building instances, but they are often tuned to a single sensor or region and may provide limited control over local context consistency and tile-level building coverage in cross-domain settings [

35,

36,

37]. In contrast, histogram- or statistics-based normalization aligns global intensity distributions but cannot capture geometric shifts such as changes in building density, size, or dominant orientation. Hybrid OBA–HM therefore combines complementary mechanisms: object-based augmentation increases plausible structural diversity and coverage, while histogram matching regularizes brightness and color toward the target domain, jointly mitigating the coupled structure–appearance gap in cross-domain building segmentation.

Furthermore, to systematically verify the effectiveness of the proposed technique under various source–target combinations using OEM global and KOMPSAT-3A regional scenarios, we introduce domain indicators that help characterize domain gaps and analyze their association with segmentation performance. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

We propose a hybrid data-centric framework that integrates object-based augmentation with histogram matching to jointly mitigate geometric and radiometric domain gaps in cross-domain building segmentation.

We design an object-based augmentation mechanism that increases structural diversity and building coverage through multi-stage object replacement, object-count-based coverage filtering, and geometric transformations, while preserving object-level geometric consistency across domains.

We introduce domain indicators based on brightness, color, and directionality and propose an analysis protocol that quantitatively relates domain discrepancies to segmentation behavior across transfer scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the study areas and datasets and details the proposed Hybrid OBA–HM framework, including its object-based augmentation and histogram-based normalization components.

Section 3 presents the experimental setup, parameter configuration, and quantitative and qualitative evaluation results for global and regional cross-domain scenarios.

Section 4 discusses the results and their implications, and

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research. Additional details supporting clarity and reproducibility (notation, key settings, dataset splits, and extended results) are provided in

Appendix A (

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4 and

Table A5).

2. Materials and Methods

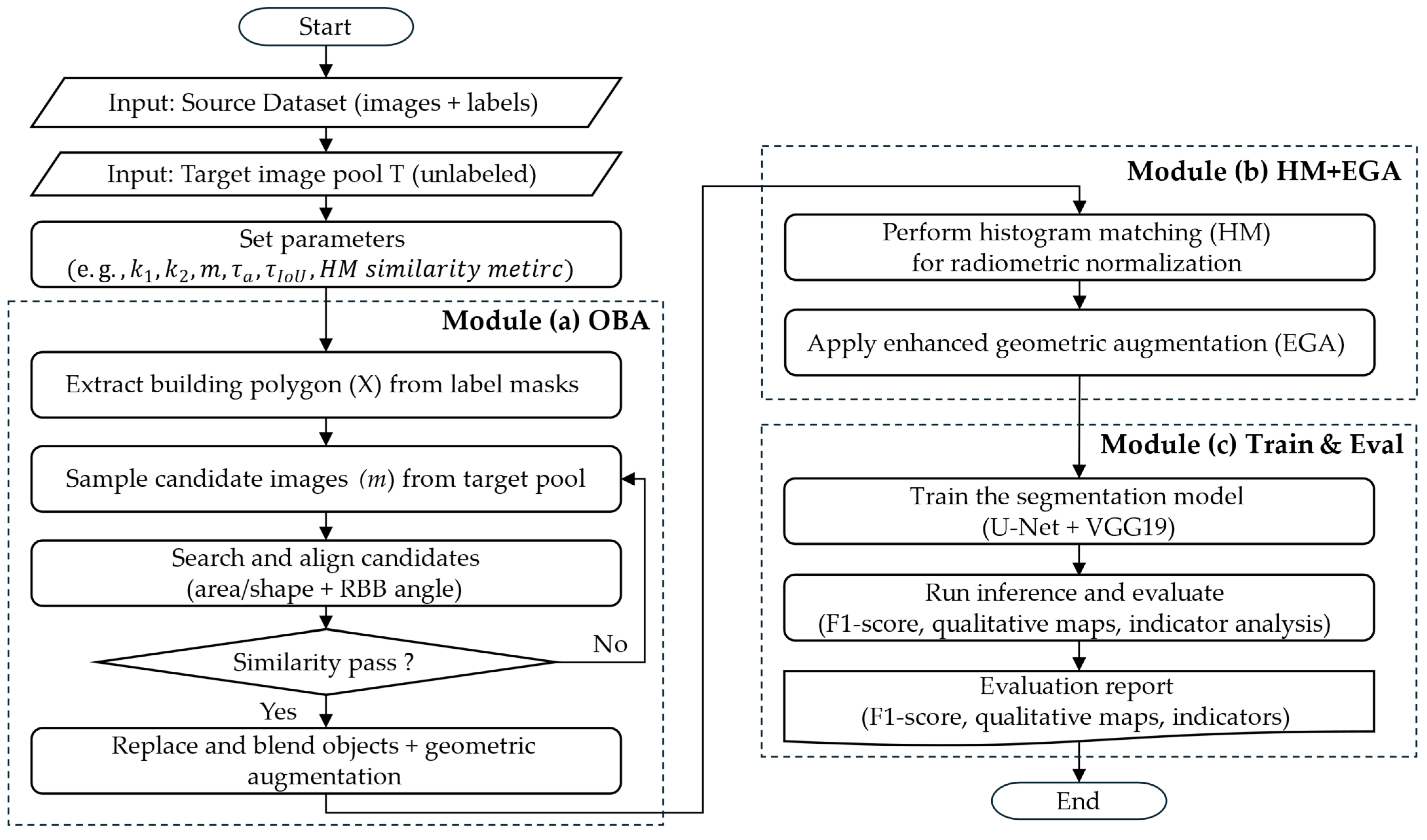

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the proposed Hybrid OBA–HM pipeline. The workflow is organized into three main modules. (a) The Object-Based Augmentation (OBA) module increases building-level structural diversity via object replacement, generating an OBA-augmented dataset. (b) The Histogram-Based Normalization and Enhanced Geometric Augmentation (HM + EGA) module takes the OBA-augmented data as input, performs radiometric alignment using EMD-based histogram analysis and Shannon entropy-based target selection, applies global histogram matching, and then conducts enhanced geometric augmentation to obtain an HM–EGA-augmented dataset. (c) The final training set is formed by combining the original images with the augmented data and is used to train a U-Net–VGG19 segmentation model; the trained model is subsequently evaluated for cross-domain generalization on OpenEarthMap and KOMPSAT-3A scenarios.

2.1. Study Areas and Datasets

The proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) framework was evaluated on two remote sensing building segmentation datasets: the OpenEarthMap (OEM) dataset [

45] for global generalization experiments and a KOMPSAT-3A dataset for regional generalization. The OEM dataset consists of high-resolution satellite and aerial imagery with spatial resolutions ranging from 0.25 m to 0.5 m, collected from 97 regions across six continents. This dataset, created by merging existing datasets from various continental regions, exhibits differences in acquisition time, weather conditions, and sensor characteristics. Consequently, regional variations in brightness and color distributions occur, as well as geometric heterogeneity resulting from differences in building architecture and urban density. The KOMPSAT-3A dataset comprises images of three South Korean cities—Seoul, Incheon, and Jeju—captured by the same optical satellite, KOMPSAT-3A. The satellite provides a panchromatic resolution of 0.55 m and a multispectral resolution of 2.2 m. In this study, we used vendor-provided pan-sharpened (PS) imagery, which yields an effective spatial resolution of approximately 0.5 m. The specific pansharpening (fusion) algorithm used to generate the PS product is not specified in the product documentation. For training, we used the PS RGB bands and converted the original 16-bit imagery to 8-bit prior to dataset construction. The dataset exhibits significant inter-city variations in brightness and color distributions, as well as geometric heterogeneity caused by differences in building shape, roof orientation, and density.

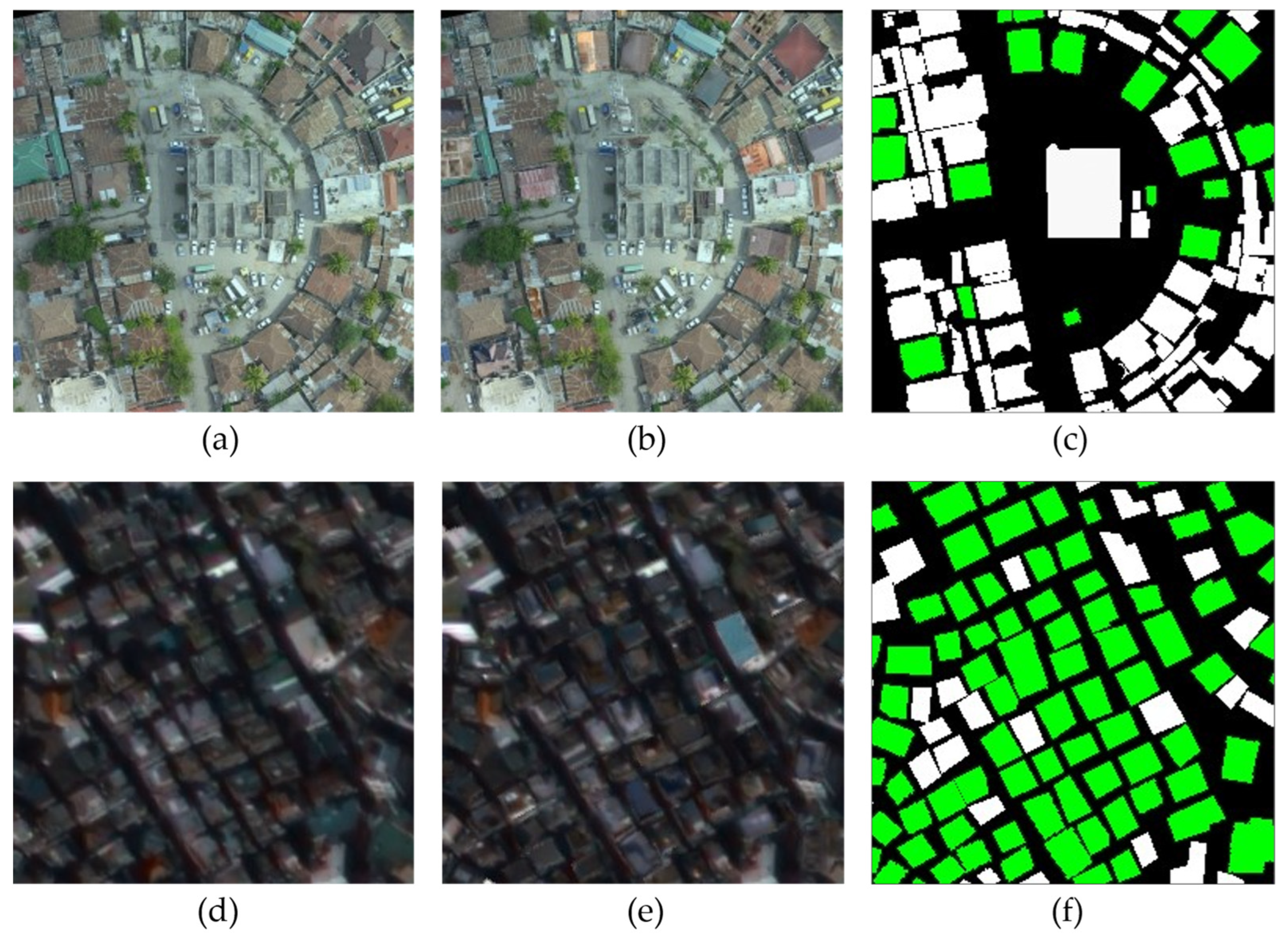

Figure 2 shows representative examples of input images from the OEM and KOMPSAT-3A datasets. A European scene from the OEM dataset displays mainly isolated buildings, whereas the KOMPSAT-3A scenes over Seoul, Incheon, and Jeju depict closely packed buildings with strong directional layout patterns, highlighting both radiometric and geometric discrepancies between the two domains.

2.2. Object-Based Data Augmentation

The objective of this study is to improve the generalization performance of a building segmentation model by reducing domain discrepancies caused by differences in region, sensor characteristics, and illumination conditions. The proposed method combines OBA and histogram-based normalization (HM) within a unified two-stage framework. In the first stage, the object-based data augmentation performs building-level object replacement, geometric alignment, and transformation to obtain greater structural diversity within the training dataset. In the second stage, the histogram-based normalization reduces photometric distribution differences between the training and target datasets. After histogram alignment, geometric transformations are further applied to the normalized data to enhance model robustness. Through this two-stage process, the proposed method strengthens the robustness and adaptability of the building segmentation model against combined photometric and geometric variations across domains, thereby improving cross-domain generalization performance.

For clarity, the proposed augmentation workflow is organized into two sequential stages. Stage 1 (Object-Based Augmentation, OBA) increases structural diversity by replacing building instances within their original footprints and applying geometric transformations. Stage 2 (Histogram Matching with Enhanced Geometric Augmentation, HM + EGA) reduces radiometric mismatch to the target domain via histogram matching and then reapplies geometric transformations to improve robustness. The details of Stage 1 are described in

Section 2.2, and Stage 2 is presented in

Section 2.3.

Existing object-based augmentation research has improved semantic segmentation and change detection performance by synthesizing building or change objects from label masks onto various backgrounds or by applying cut-and-paste and adversarial instance insertion [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Specifically, ref. [

35] is conceptually related to our work because it leverages object-level manipulation to enrich training data. However, our Stage-1 design differs from [

35] in three key respects. First, ref. [

35] selects a background image and places independent object instances onto it. In contrast, we keep the original background fixed and replace a building instance with another geometrically similar building instance within the same scene context. This design preserves local layout consistency. Second, ref. [

35] assumes separable backgrounds with sufficient free space, which can be limiting in dense urban scenes where buildings occupy most of the image. Our replacement-based design does not require large empty background regions, making it suitable for building-dense imagery. Third, our method operates at a substantially larger scale. In our experiments, the number of replaced building instances ranges from approximately 38,000 to 87,000 per scenario. By comparison, ref. [

35] reports far fewer processed instances (below 1000 in the training set). However, most existing approaches operate within a single sensor or single region. They also rely on random object replacement and simple geometric or color transformations. This limits their ability to control object-level geometric consistency and tile-level building coverage in cross-domain settings. The Stage-1 OBA module in this study addresses these limitations by combining building-polygon-based candidate selection, coverage filtering, and primary geometric augmentation. The module generates cross-domain–oriented augmented samples in which building structure and density are not unrealistically distorted, even when the source and target domains differ.

The proposed pipeline uses the original images, label images, and the polygonal building regions extracted from the label masks as inputs. The sequence of operations is as follows:

- (1)

polygon extraction and attribute computation;

- (2)

multi-stage object replacement;

- (3)

object-count-based coverage filtering;

- (4)

first-stage geometric augmentation;

- (5)

histogram-based normalization; and

- (6)

enhanced geometric augmentation.

The output dataset is constructed by combining the augmented images and labels generated after the enhanced geometric augmentation stage with the original images and label maps, thereby producing a comprehensive training dataset for model learning.

The proposed method enhances object-level structural diversity from a limited training dataset while normalizing the photometric distribution of training images. Through this combination, the method effectively mitigates the degradation of model performance caused by domain discrepancies and achieves greater generalization capability across diverse regions and sensors.

2.2.1. Polygon Extraction and Attribute Computation

The first step in object-based data augmentation is to extract building polygons from the label images of the training dataset. Each label image consists of binary labels representing buildings and non-building (background) areas. For each building polygon

k, the contour

is extracted to define the polygon boundary. From the extracted contour, the centroid

and the area

of the rotated bounding box are calculated as follows:

These geometric attributes of each building polygon are subsequently used during object similarity evaluation and object replacement processes in later stages of the augmentation pipeline.

2.2.2. Multi-Stage Object Replacement Loop

The multi-stage object replacement process replaces building objects in the training dataset with similar objects from other images within the same dataset in a sequential manner. The replacement operation is repeatedly applied to those objects that were not replaced in the first or previous stages. Compared with a single replacement step, performing replacements over multiple stages improves the overall ratio of object replacement and increases the structural diversity of the augmented dataset. From the training dataset,

candidate images are randomly selected, excluding the image that contains the target object to be replaced. Instead of searching through all available images, random selection reduces computational cost and ensures that diverse object shapes are incorporated into the augmentation process. This random sampling strategy also prevents specific images or objects from being repeatedly selected, thereby avoiding potential imbalance within the training data. Although the number of candidate images is limited to

m, the number of candidate object polygons contained in those images remains very large. Therefore, only polygons with an area similar to that of the target polygon are selected as candidate polygons. The similarity between the target object polygon and each candidate polygon is measured using the Intersection over Union (IoU) metric. Only candidate object polygons

that satisfy the following condition are retained for similarity comparison:

where

and

denote the areas of the candidate polygon

and the target polygon

, respectively, and

is the predefined area similarity threshold.

Each candidate polygon

is then rotated so that the angle of its rotated bounding box matches the rotation angle

of the target polygon

. The similarity between the target polygon

and the rotated candidate polygon

is measured using the IoU:

where

is the number of pixels common to both

and

, and

is the number of pixels contained in their union. The final candidate polygon

is selected as the rotated candidate polygon

that satisfies the following condition:

This replacement approach is not a simple random selection but a precise matching strategy that considers both the size and shape of the candidate polygons. By selecting candidate polygons that closely resemble the target polygon in size and shape, the visual consistency between the replaced polygon and its surrounding background is effectively preserved after the replacement process.

To replace the object polygon , the polygon is first removed from the image, and the pixels of the final candidate object polygon , aligned with the rotation angle of the rotated bounding box (RBB), are copied into the position corresponding to polygon .

To replace a target building, we confine the operation to the target footprint: the candidate building content is clipped by the target polygon mask so that replacement occurs strictly within the original building boundary. This design prevents introducing additional overlaps with surrounding classes (e.g., roads or vegetation) beyond those already present in the source annotation. To reduce boundary seams and abrupt local-context changes, we apply feathering blending along the polygon boundary. Feathering blending is applied to minimize visual discontinuities between the replaced polygon

and the surrounding background near the polygon boundary. The feathering process gradually smooths the transition of color and intensity between the replaced polygon

and the original background. When the internal pixel intensity of polygon

is

and the pixel intensity of polygon

in the original image is

, the synthesized intensity

of the replaced polygon

is determined by the weighting function

, which controls the relative influence of

and

according to the pixel position

within the object:

To reduce seam artifacts after object insertion, we apply feathered blending along the building boundary. Specifically, a fixed feathering distance of 2 pixels is used to smooth the intensity transition between the replaced building object and the surrounding background while preserving boundary sharpness. Here, the background is defined by the binary building mask (label = 0), and no additional thresholding is introduced beyond the provided mask.

During visual inspection of the augmented samples, we occasionally observed a radiometric seam in bright-background scenes where both roofs and surrounding areas are highly reflective. In a small subset of augmented images, a few replaced roofs appeared slightly darker than their immediate surroundings. This artifact was rare and limited to a small number of buildings in a small portion of the augmented training set, while the building footprint and label geometry remained unchanged. After geometric replacement and blending, the subsequent histogram matching stage further regularizes brightness and color statistics at the image level.

2.2.3. Object-Count-Based Coverage Filtering

The number and density of objects in images where object polygons have been replaced can vary significantly from image to image. Some images contain a large number of object polygons, many of which have been replaced, whereas others include only a few objects and replacements. When the training dataset contains a high proportion of images with a low object-to-background ratio, the influence of background pixels becomes relatively large during loss computation, thereby reducing the contribution of object regions. As a result, the model may fail to adequately learn the shape and boundary characteristics of buildings. To alleviate this imbalance, images are ranked based on the number of building objects they contain, and those with higher object counts are preferentially selected.

After replacing objects, the number of objects in each image is counted and sorted in descending order, and the images with the highest number of objects are subsequently selected. The number of objects in the label image

is defined as

, and all boundaries detected through object contour extraction are regarded as individual objects. When the total number of label images is

and the number of objects sorted in descending order is expressed as

, the object-based coverage corresponding to the top

label images is defined as follows:

where

denotes the number of objects in the

-th image after sorting in descending order, and

represents the number of objects in the

-th image in the original (unsorted) order. Images are progressively selected and included in the training dataset until the object-based coverage

reaches or exceeds a predefined ratio

.

2.2.4. Object-Based Geometric Augmentation

The object-based augmentation contributes to improving data diversity and domain generalization by replacing building objects in the training images with other building objects of similar size and shape within the same dataset. However, OBA alone has difficulty sufficiently simulating various geometric variabilities, such as changes in orientation, scale and resolution mismatch, and positional misalignment of objects resulting from differences in acquisition angle, resolution, and projection. To enhance robustness to such spatial deformations, we apply geometric augmentation to the images generated through OBA. In this step, we use a standard 2D geometric transformation (Equation (9)) to explicitly introduce controlled variations in orientation, scale, and position. This formulation allows us to simulate spatial deformations commonly observed across domains and to improve robustness to acquisition- and projection-related geometry changes. Moreover, the same transformation is applied to both the image and its corresponding mask/polygon to preserve label–image consistency. The transformations considered are

Each transformation represents, in order, horizontal flip, vertical flip, orthogonal rotation, random rotation, scaling, and translation, and the definition of each transformation is as follows:

where

is a two-dimensional rotation matrix, and

represents a uniform distribution in the interval

,

and

represent the rotation angle range,

and

represent the scaling factor range, and

and

represent the translation distance range.

Geometric transformations are applied to both training and label images through a two-step randomization process. In the first step, one of the defined transformations is randomly selected. In the second step, the parameters of the selected transformation (e.g., rotation angle, scaling factor, translation distance) are randomly sampled within a predefined parameter range:

If the number of OBA-augmented images is , and geometric transformations are applied times to each, the total number of geometrically transformed images becomes . The value of is empirically determined by analyzing changes in model generalization performance as data diversity increases. Through these geometric transformations—such as rotation, scaling, and translation—the spatial variability of the OBA-generated images is further expanded.

2.3. Histogram-Based Normalization and Enhanced Geometric Augmentation

Differences in sensors, acquisition time, and imaging regions often cause mismatches in color distribution between the training and target datasets. Such discrepancies can intensify distributional gaps between domains. In this study, we propose a method that combines histogram matching (HM) with object-based augmentation (OBA) to align the color distribution of training images with that of target images. This approach mitigates domain discrepancies and reduces the model’s performance degradation on the target dataset.

Importantly, the proposed HM is unpaired and non-temporal: it does not require adjacent tiles, overlapping regions, or time-series image pairs. For each training image, the reference (target) image is selected from an unlabeled target-domain pool based solely on distribution similarity, and the transformation is applied globally to the entire image.

During the target candidate selection process, candidate target images are selected based on the histogram of the background regions in the training images where large inter-domain color distribution differences exist. The histogram matching transformation is then applied to the entire image to maintain consistent color tones across the scene. In this study, we use a scenario-specific, fixed number of randomly sampled target candidates (m) for EMD-based matching. The values of m (set to 10% of the training tiles per scenario) are summarized in

Appendix A (

Table A2). The histogram distribution difference between a fixed number of randomly selected target images and the background of the training image is computed using the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) metric. Target images with smaller EMD values are selected as high-ranking candidates. A smaller EMD indicates that the target image has a radiometric distribution closer to that of the training image background. This reduces the risk of unrealistic color shifts and boundary artifacts during subsequent histogram matching, resulting in more stable cross-domain normalization. Among these selected candidates, the target image exhibiting the lowest Shannon entropy—indicating a more uniform and stable color distribution—is chosen as the final target image. By performing histogram matching between this final target image and the training image, the color and luminance distribution of the training image are aligned with the statistical distribution of the target image, thereby correcting color mismatches between domains.

Finally, enhanced geometric augmentation (EGA) is applied to the histogram-normalized images. This step extends the morphological diversity of the training dataset through geometric transformations, thereby enhancing the model’s structural generalization capability. The alignment of color distributions achieved by histogram normalization, combined with the shape and structural diversity introduced through geometric augmentation, contributes to reducing the negative effects of domain gaps on overall model performance.

2.3.1. Histogram Normalization

To compare the distributions between the training and target images, we first define the normalized histogram and the cumulative distribution function (CDF). For channel

of image

, let

denote the number of pixels with intensity value

, and let

be the total number of pixels. The normalized histogram

and CDF

are given by

Various distance metrics can be considered when comparing the distributions between the training and target images. The L2 distance metric, while simple to compute, can produce large differences even when there is only a simple shift between distributions [

46]. The Kullback–Leibler divergence (KL) can precisely reflect information differences between distributions [

47] but becomes unstable in sparse data regions [

46]. The Chi-square distance is sensitive to shape differences between distributions [

46,

48] but is vulnerable to noise [

46,

49].

In contrast, the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) calculates the difference between two distributions from the perspective of transport cost, making it more stable under shifts in luminance or color distributions [

46,

50]. In this study, EMD is selected as the distance metric because it is robust to inter-domain differences in illumination and color distributions. Let

and

denote the CDFs of the training and target images, respectively. Then, the EMD for each channel

is defined as

The overall EMD, obtained by summing the distances across all three color channels, is given by

During the process of aligning the training image distribution to that of the target image through histogram matching, there is a possibility that the color distribution of the training image may become excessively distorted or overly smoothed, resulting in information loss. In particular, detailed characteristics of pixels in low-contrast regions may be lost, and excessive loss of fine visual information—such as object boundaries and texture—may occur. To address this issue, Shannon entropy is additionally applied as an evaluation metric among the EMD-based target candidates.

The Shannon entropy of an image

is defined as

where

is a small constant introduced to ensure numerical stability.

If the distribution of pixel intensities is concentrated within a specific range, the entropy value becomes low, indicating a small amount of information. Conversely, if the pixel intensity distribution is evenly spread across the entire range, the entropy value is high, implying a larger amount of information content. The difference

between the entropy of the training image

and the entropy of the histogram-matched image

serves as an indicator of the degree of information preservation in the training image before and after histogram matching, and is expressed as follows:

First, for the training image

and the target image primary candidate set

, the EMD between the training image and each target image is computed as:

Based on the EMD values, the top

target images are selected, and a secondary target candidate set

is formed as follows:

Among the images in the secondary candidate set, the target image

that minimizes the histogram entropy difference

with respect to the training image

is selected as the final target image

:

Finally, histogram matching is performed between the final target image and the training image to generate the final transformed image.

2.3.2. Enhanced Geometric Augmentation

Histogram matching mitigates illumination- and color-based domain discrepancies between the training and target images. However, this process may reduce color diversity and diminish the visual variations introduced by geometric transformations. To compensate for this, geometric transformations are reapplied after histogram matching to expand color-independent geometric diversity.

The enhanced geometric augmentation randomly selects

images—where

is the number of object-based augmented images—from the histogram-normalized image set

. For each selected image and its corresponding label, one of the previously defined geometric transformations is randomly chosen and applied. The transformation parameters are also randomly sampled within predefined parameter ranges. The image set generated through enhanced geometric augmentation, denoted as

, is then merged with the original image set

to form the final training dataset

:

The final training dataset enhances domain transfer adaptability by integrating the structural diversity obtained through histogram matching and geometric augmentation with the luminance and color distribution statistics of the original images.

The outputs and data format are summarized as follows. All intermediate and final outputs are organized in a structured directory hierarchy, including the original images, OBA-augmented images, histogram-normalized images, and the corresponding label masks. Data are stored in standard PNG format with one-to-one filename correspondence between images and masks. This structure is computer-friendly for common deep learning pipelines and user-friendly for visual inspection. Final predictions are exported as binary masks aligned with the input tiles; when needed, the masks can be vectorized into building polygons for GIS use. Key settings required for re-implementation and verification are summarized in

Appendix A (

Table A3).

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Experimental Setup and Parameter Configuration

3.1.1. Dataset Partitioning

The OEM dataset was partitioned following a Leave-One-Continent-Out (LOCO) strategy: five of the six continents were used as the training set, while the remaining continent served as the validation and test set. Here, “continent” refers to the OpenEarthMap metadata category used to group scenes by continent, and each continent is treated as a geographic domain. This configuration resulted in six distinct LOCO scenarios, following the OEM benchmark protocol [

45].

To avoid spatial leakage, we construct splits at the geographic-unit level rather than by randomly sampling images. For OEM, we adopt a leave-one-continent-out (LOCO) protocol; within the held-out continent, regions are partitioned into disjoint validation and test subsets (approximately half-and-half), and all images inherit the split assignment of their corresponding region. For KOMPSAT-3A, the target city is spatially partitioned into non-overlapping sub-areas that are assigned to validation and test, ensuring geographic separation between the two subsets; the resulting train/validation/test image counts are summarized in

Appendix A (

Table A4). Due to the large size of the OEM dataset, the training and validation subsets were randomly sampled at 20% of the original dataset size, while the test subset was used in full without reduction. Using these scenario-specific datasets, we analyzed the extent to which the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) technique mitigates domain mismatches and improves generalization performance under global conditions characterized by differences in acquisition time, sensor type, and illumination.

For the KOMPSAT-3A dataset, we constructed three cross-city scenarios by designating two of the three cities as training datasets and the remaining city as the validation and test dataset: Seoul + Incheon → Jeju (S + I → J), Jeju + Seoul → Incheon (J + S → I), and Incheon + Jeju → Seoul (I + J → S). In our notation, the cities on the left-hand side form the source domain used for training, whereas the city on the right-hand side is treated as the target domain for validation/testing (e.g., S + I → J trains on Seoul and Incheon and evaluates on Jeju). Using this cross-city setup, we analyze inter-city domain discrepancies driven by brightness, color, and geometric variations. Together with the OEM LOCO setting described above, this yields global (OEM) and regional (KOMPSAT-3A) transfer scenarios for evaluating Hybrid OBA–HM under diverse domain shifts.

3.1.2. Network Training and Implementation

To evaluate model accuracy, all methods were trained and tested with the same segmentation backbone to ensure a fair comparison. We used a U-Net architecture [

1] with a VGG-19 encoder [

51] initialized from ImageNet weights. Training was performed using the AdamW optimizer (decoupled weight decay) with a learning rate of 1 × 10

−4 and a weight decay of 1 × 10

−5, a batch size of 16, and 10 epochs. No early stopping was applied; instead, the final model for reporting was selected using the median F1 score over the last three epochs on the validation set. The loss function was binary cross-entropy. All experiments were repeated three times, and both the mean and standard deviation of the performance metrics were reported. All data augmentation was applied offline prior to training (

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3), and no additional online augmentation was used during training. All inputs were prepared as 256 × 256 image tiles and min–max scaled to [0, 1] before being fed to the network. Experiments were implemented in Python using TensorFlow–Keras, and all results were produced on a workstation equipped with two NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs (48 GB each), an Intel i9-10980XE CPU (3.0 GHz), and 128 GB DDR4-3200 RAM. Model predictions are exported as binary segmentation masks (uint8) aligned with the input tiles, and they can optionally be vectorized to building polygons for GIS use.

3.1.3. Augmentation Parameters

The augmentation parameters of the proposed method consisted of combinations of the number of object replacement iterations and the number of enhanced geometric augmentation iterations within the Hybrid OBA–HM pipeline. Performance analysis was conducted for each combination to determine the optimal configuration, which was then applied consistently in all subsequent experiments.

The number of candidate images for polygon replacement was set to 10% of the total number of training images in each scenario, considering both the replacement ratio and computational efficiency. The area similarity threshold and the IoU-based shape similarity threshold were each set to 0.85. The object-count-based coverage parameter was set to 0.8, and the feathering distance was set to 2 pixels to minimize color distortion within the replaced objects. The number of object replacement stages was determined considering both dataset characteristics and computational efficiency. For the OEM dataset, which includes a wide variety of building types across multiple global regions and is used in multiple domain scenarios, a single-stage replacement was performed. In contrast, for the KOMPSAT-3A dataset, which is relatively smaller and exhibits a higher degree of homogeneity among building objects in the training data, a two-stage replacement was conducted.

3.2. Object-Based Augmentation Results

We analyzed the results of applying the proposed OBA method to the OEM and KOMPSAT-3A datasets.

Table 1 presents the results of object-based augmentation on the OEM dataset (single-stage replacement). The proportion of replaced objects across the six scenarios ranged from 24.8% to 30.1%, with an average of 27.65% ± 2.06%. The mean IoU similarity of all replaced polygons across all scenarios was 0.895 ± 0.001, and the average IoU standard deviation was 0.037 ± 0.001. These results indicate that the replaced polygons exhibit a very high degree of shape similarity to the original polygons and that both geometric consistency and positional alignment were stably maintained throughout the augmentation process.

Among the augmented images, the overall average ratio of the final augmented images included within the object-count-based coverage across all scenarios was 32.95% ± 1.28%. This result demonstrates that the augmented images were stably generated at a consistent proportion across all scenarios, indicating the reliability and reproducibility of the augmentation process.

Table 2 shows the object replacement results after performing two-stage object replacement on the KOMPSAT-3A dataset. Between the first and second replacement stages, the augmented image generation rates increased from 70.95% to 73.63% for S + I → J, from 73.17% to 75.42% for J + S → I, and from 42.20% to 45.92% for I + J → S. The average increase in augmented image generation between the first and second stages was 2.88% ± 0.62%, indicating stable growth across all scenarios. The average IoU similarity of all replaced polygons was 0.887 ± 0.006, and the mean IoU standard deviation was 0.041 ± 0.006. The average proportion of object-augmented images across the three scenarios was 27.07% ± 4.37%.

Although the characteristics of the KOMPSAT-3A dataset differ significantly from those of the OEM dataset, the average IoU similarity of replaced polygons in each dataset remained close to 0.89, and the standard deviation was below 0.05. This demonstrates that the proposed object-based augmentation method performs stable polygon replacement even when domain characteristics change. Additionally, while the average augmentation rate in the KOMPSAT-3A dataset was slightly lower and its standard deviation slightly higher than that of the OEM dataset, the deviation remained below 5%, confirming that the proposed augmentation process maintains high stability across domains with differing characteristics.

Figure 3 presents sample results of applying object-based augmentation to the OEM and KOMPSAT-3A datasets. Each example consists of the original image, the augmented image, and the label image. In the label image, replaced buildings are highlighted in green, whereas unreplaced buildings are shown in white. In the OEM example (

Figure 3a–c), partial object replacements were applied, and the replaced objects were seamlessly blended into the context of the original scene, thereby preserving a high degree of visual naturalness and contextual coherence. In the KOMPSAT-3A example (

Figure 3d–f), most building objects were replaced; however, geometric consistency was successfully maintained. The replaced objects remained spatially coherent with the surrounding roads and adjacent buildings in terms of position, rotation, and orientation, demonstrating natural spatial alignment. This consistency was achieved through rotational alignment and IoU-based candidate filtering during the object replacement process. Consequently, even with OBA applied independently, the proposed method qualitatively demonstrates its capability to achieve visual and structural consistency in both partial replacement scenarios (OEM) and high-coverage replacement scenarios (KOMPSAT-3A).

3.3. Performance on Global and Regional Scenarios

We analyzed the effect of varying the object replacement repetition number and the enhanced geometric augmentation repetition number used in the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method on model performance across different domains. The experiments were conducted using the OEM dataset for the global domain and the KOMPSAT-3A dataset for the regional domain environment.

For the OEM dataset, the average accuracy was calculated by performing three trials for each parameter combination across the six LOCO scenarios, and the overall mean and standard deviation were obtained. For the KOMPSAT-3A dataset, two of the three cities were used for training and the remaining city for validation and testing; the average accuracy from three trials was calculated for each parameter combination, and the mean and standard deviation across the three cross-city scenarios were computed.

Accuracy evaluation for each parameter combination was conducted by first selecting the optimal model based on the training and validation datasets, and then applying the selected model to the test dataset to obtain the final accuracy. The average F1-score values for each parameter combination on both datasets are summarized in

Figure 4.

Figure 4a shows the results for the OEM dataset, and

Figure 4b illustrates the results for the KOMPSAT-3A dataset.

3.3.1. OEM-Scenario (Global Domains)

In the OEM scenario heatmap in

Figure 4a, the vertical axis represents the number of object replacement iterations

, the horizontal axis represents the number of geometric augmentation iterations

, and the color scale indicates the F1-score. Overall, the heatmap shows a trend in which the color intensity increases toward the right and bottom, indicating that performance improves as both

and

increase.

However, in the region where , the accuracy either stagnated or slightly decreased in some scenarios (1, 2, and 4), suggesting that excessive object replacement may cause distributional distortion. In the horizontal direction , performance consistently improved from to ; however, when , the color change became more gradual, indicating that the effect of geometric augmentation had reached saturation. The best performance was achieved at , with an average F1-score of 0.848 and a standard deviation of σ = 0.0386. Although and are both displayed as 0.848 in the heat maps due to rounding to three decimal places, their averaged F1-scores are 0.8477 and 0.8481, respectively, indicating that is the true maximum configuration. These results demonstrate that , a balanced combination of object replacement and geometric augmentation, is the most effective configuration for achieving global domain generalization.

3.3.2. KOMPSAT-3A Scenario (Regional Transfer Domains)

In the KOMPSAT-3A scenario heatmap in

Figure 4b, the color intensity also becomes progressively darker toward the right and bottom. This trend, similar to that observed in the OEM scenario, indicates that performance improves as both the number of object replacement iterations and geometric augmentation iterations increase. At the bottom-right region of the heatmap, corresponding to

, the average F1-score reached its maximum value of 0.6895. However, the improvement compared with the optimal combination derived from the OEM scenario,

, was minimal, with a difference of ΔF1 ≈ 0.008. Statistical testing confirmed that the difference in F1-score between the

and

combinations was not statistically significant (

p = 0.62, α = 0.05). The parameter combination

, identified from the OEM scenario, was thus verified to maintain statistically equivalent performance in both global and regional domain environments. Accordingly, this configuration was adopted as the optimal parameter setting for all subsequent experiments.

3.4. Comparative Evaluation and Statistical Robustness

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method, we compared it with six widely used data augmentation methods. The compared methods include RGT (Random Geometric Transform), RIC (Random Image Copy), PA (Photometric Adjustment), GHM (Global Histogram Matching), CycleGAN, and ColorMapGAN. The main characteristics of these methods and the domain aspects they target are summarized in

Table 3. Each augmentation method was independently analyzed using the same datasets and identical model parameter settings to assess performance variations attributable to the augmentation strategies.

Each comparison method was designed to address different types of domain discrepancies. RGT enhances geometric invariance by expanding diversity in scale, orientation, and spatial arrangement. RIC mitigates the imbalance between object and background classes by increasing the number of training samples through random duplication. PA improves robustness to radiometric variations such as lighting and weather conditions by randomly adjusting brightness, hue, and saturation. GHM alleviates cross-domain color mismatch by aligning the color distribution of training images to that of the target domain. CycleGAN transforms source images into the style of the target domain without requiring paired training data, thereby reducing global appearance discrepancies in color tone, texture, and illumination. ColorMapGAN employs GAN-based color mapping to align the color distribution of source images with that of the target domain, effectively mitigating color and radiometric mismatches between domains.

The proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method simultaneously achieves geometric diversity through object-based augmentation and geometric transformations, while enhancing robustness to radiometric variations through histogram normalization, thereby providing balanced domain adaptation performance that effectively compensates for both geometric and radiometric discrepancies.

The key parameters for each method were configured as follows: RGT applied rotations of ±30°, scaling between 0.8 and 1.2, translations of ±20 pixels, and a horizontal flip probability of 50%. RIC used random replication of original images with replacement allowed. PA applied random adjustments to brightness (±51), contrast (0.8–1.2), gamma (0.9–1.1), hue (±5°), and saturation (±15%). GHM performed color alignment in Lab color space using weighting factors (0.3/0.2/0.2 for L/a/b) and clipping in the 1–99% range.

3.4.1. OEM Dataset

Table 4 presents the average and standard deviation of the F1-score for each augmentation method, as well as the performance improvement compared with the baseline, using the OEM dataset under global-domain conditions. Here, Baseline denotes training on the original dataset without object-based augmentation (OBA), histogram matching (HM), or enhanced geometric augmentation (EGA), using only the standard preprocessing applied to all methods (e.g., resizing and normalization). Unless otherwise stated, this Baseline definition applies to the comparisons reported in

Table 4 and

Table 5, and all other training and evaluation settings are kept identical across methods to ensure a fair comparison.

To address the effect of combining OBA with histogram matching, we additionally report OBA-only results and compare them with the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM). The goal of this comparison is to quantify the incremental, pipeline-level benefit of adding histogram matching after object replacement, rather than to equalize the number of generated samples across pipelines. We note that OBA-only yields fewer unique augmented samples than Hybrid by design because it excludes the HM-based stage and the subsequent augmentation steps. Therefore, the OBA-only vs. Hybrid gap should be interpreted as a practical estimate of the benefit of the combined method under our two-stage framework. All methods are trained and evaluated using identical architectures, hyperparameters, and protocols.

The baseline model achieved an average F1-score of 0.808 ± 0.034. The RGT method, which randomly applied geometric transformations such as rotation, scaling, and translation, yielded a performance improvement of ΔF1 = +0.013 compared with the baseline. This improvement is attributed to the model’s enhanced ability to adapt to variations in building shape, spatial arrangement, and orientation through exposure to diverse geometric transformations. The RIC method increased the dataset size by randomly sampling images from the training dataset, resulting in a modest improvement of ΔF1 = +0.008. This indicates that, in large-scale and multi-domain environments, the effect of duplication was relatively limited, and the increase in dataset volume contributed to a modest enhancement in the stochastic stability of model training. The PA method, which applied random adjustments to brightness, contrast, gamma, hue, and saturation, achieved an improvement of ΔF1 = +0.010, enhancing robustness to variations in color and illumination conditions. The GHM method, which reduces radiometric differences through global histogram matching, showed only a limited improvement of ΔF1 = +0.004, likely because global normalization does not sufficiently capture localized radiometric characteristics present across different domains. CycleGAN provided no overall performance improvement compared with the baseline (ΔF1 ≈ −0.020), and ColorMapGAN achieved only a small improvement of ΔF1 ≈ +0.004. These results suggest that, while both methods contribute to global style and color alignment, they may not sufficiently compensate for structural domain differences and boundary information—such as building size, density, and background composition—which are important in OEM scenarios.

The proposed object-based augmentation alone (OBA-Only) achieved an average F1-score of 0.827 ± 0.031, corresponding to a +0.019 improvement over the baseline. This indicates that object-level replacement enhances structural diversity and improves generalization under global-domain conditions. Compared with OBA-Only, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) further increased the F1-score by 0.013 (0.840 vs. 0.827), suggesting an additional benefit from histogram-based radiometric normalization when combined with object-level augmentation.

In contrast, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method achieved an average F1-score of 0.840 ± 0.026, corresponding to a +0.032 improvement over the baseline. This superior performance is attributed to the combination of object-level structural diversity and histogram-based radiometric normalization, which jointly mitigates both geometric and radiometric mismatches. Moreover, the standard deviation (±0.026) was similar to or lower than those of the other methods, indicating that the proposed approach yields statistically stable and reproducible results.

3.4.2. KOMPSAT-3A Dataset

Table 5 presents the results of the cross-city domain transfer experiments conducted using the KOMPSAT-3A dataset. The baseline model achieved an average F1-score of 0.455 ± 0.198, exhibiting substantial performance instability caused by structural variations across cities—including differences in building density, orientation, and architectural shape. The RGT method achieved a performance improvement of ΔF1 = +0.043, indicating that geometric transformations effectively corrected inter-city geometric discrepancies and improved overall accuracy. The RIC method resulted in a performance decline of ΔF1 = −0.012, suggesting that, in small-scale and relatively homogeneous domains, simply increasing the dataset size does not enhance structural diversity and may instead lead to overfitting to specific city patterns. The PA method yielded the largest performance gain among the single augmentation methods, achieving ΔF1 = +0.046. This finding implies that, despite the use of the same sensor, differences in illumination and color still exist between domains, and compensating for radiometric diversity is effective in improving transfer performance. The GHM method resulted in a performance decrease of ΔF1 = −0.019, indicating that global histogram normalization can locally reduce image contrast, thereby degrading accuracy. CycleGAN produced a performance degradation of ΔF1 = −0.023 compared with the baseline, whereas ColorMapGAN showed a relatively small improvement of ΔF1 = +0.043. These results suggest that, while both CycleGAN and ColorMapGAN methods contribute to reducing differences in illumination and color between cities, they have limitations in independently addressing the structural domain gaps prominent in the KOMPSAT-3A dataset, such as building density, background patterns, and geometric arrangements.

The proposed object-based augmentation alone (OBA-Only) improved the baseline to 0.573 ± 0.174 (ΔF1 = +0.118), indicating that object-level replacement and geometric augmentation effectively increase structural diversity across cities. Compared with OBA-Only, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) further improved performance by 0.079 (0.652 vs. 0.573), highlighting the additional benefit of histogram-based radiometric normalization when combined with object-level augmentation.

Overall, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method achieved a significant performance improvement of ΔF1 = +0.197 over the baseline, with an average F1-score of 0.652 ± 0.119. This substantial gain can be attributed to the combined effects of object-level structural diversification through object replacement and geometric transformations, together with enhanced radiometric consistency achieved via histogram normalization. These complementary mechanisms effectively mitigate inter-city discrepancies in shape, illumination, and radiometric conditions.

To summarize the quantitative results across both OEM (

Table 4) and KOMPSAT-3A (

Table 5) scenarios, we additionally compare Hybrid OBA–HM against a pre-defined strongest baseline. Because each transfer scenario includes only three runs (

n = 3), per-scenario paired tests are underpowered; thus, we primarily interpret effect sizes and cross-scenario consistency. We pre-define the strongest baseline as the non-hybrid method with the highest overall mean F1 across all evaluated scenarios (Random Geometric TR in our experiments;

Appendix A,

Table A5). Hybrid OBA–HM improves over the strongest baseline in all nine scenarios, supported by a two-sided sign test (

p = 0.0039) and a one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test (

p = 0.00195) on the scenario-level mean differences Δ(H − Strongest) (

Appendix A,

Table A5).

Figure 5 presents a qualitative comparison of building segmentation results for each augmentation method on a sample image from the OEM dataset. Each visualization includes the original image, ground truth, and the results obtained from the baseline (no augmentation), RGT, RIC, PA, GHM, CycleGAN, ColorMapGAN, and the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method. In the segmentation maps, white represents true positives (TP), black represents true negatives (TN), red indicates false negatives (FN), and green denotes false positives (FP).

The baseline results showed the simultaneous occurrence of numerous FN and FP pixels, resulting in unstable detection of object boundaries and fine-scale structural details. The RGT method achieved the lowest FN occurrence through diverse geometric transformations, but produced the largest number of FP pixels, leading to noticeable over-segmentation. The RIC, PA, and GHM methods yielded a moderate level of FN occurrence, while FP pixels decreased compared with RGT but remained non-negligible. The GHM method produced slightly more FN pixels than the Hybrid method, while the FP pixels appeared at a nearly similar level. CycleGAN augmentation resulted in relatively few FP pixels but produced the largest number of FN pixels among all comparison methods. ColorMapGAN yielded segmentation performance comparable to that of GHM, but localized FP pixels were still observed in some regions. In contrast, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) technique yielded the fewest FN pixels and, together with PA, the lowest level of FP pixels, qualitatively confirming its geometric and radiometric correction effects.

Figure 6 shows a qualitative comparison of object-detection results for each augmentation technique using a sample image from the KOMPSAT-3A dataset. Compared with the baseline, the RGT method resulted in increased FN occurrence, and the RIC, PA, and GHM techniques also exhibited slightly larger FN pixels relative to the baseline. The CycleGAN and ColorMapGAN methods yielded the largest number of FN pixels among all the approaches. However, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method exhibited only a small number of FN pixels, with only a few FP pixels observed.

Notably, several objects that were undetected (FN) by all other methods were successfully detected by the Hybrid approach, visually demonstrating the complementary effectiveness of object-based augmentation and histogram normalization. These results indicate that the Hybrid method maintains stable and consistent object-detection performance even in the KOMPSAT-3A environment characterized by significant inter-city domain discrepancies, thereby demonstrating its superior cross-domain generalization capability.

3.5. Domain-Wise Indicator and Heatmap Analysis

In this section, we quantitatively analyze which domain indicators influence the performance improvement of the proposed method. By combining this quantitative analysis with heatmap visualization, we compare and interpret the relative characteristics of domain mismatch factors observed in the global (OEM) and regional (KOMPSAT-3A) domains. In

Section 3.5.1, the correlations between the proposed domain indicators—brightness difference (ΔMean V), color distribution (

), building variance Var(HS)_Building, and directional mismatch (

)—and the ΔF1 improvements are analyzed to evaluate the performance sensitivity to each domain discrepancy factor. Then, in

Section 3.5.2, we visually compare and interpret the types of mismatches (radiometric vs. geometric) between the OEM and KOMPSAT-3A domains using normalized domain-indicator heatmaps. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method effectively mitigates complex domain mismatches by simultaneously compensating for both radiometric and geometric discrepancies.

3.5.1. ΔF1 vs. Domain Indicators

To quantitatively analyze how the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method outperforms Photometric Adjustment (PA) across different domain dimensions such as brightness, color, and structure, the ΔF1 (=Hybrid − PA) improvement was compared with four key domain indicators: brightness difference (ΔMean V), color distribution distance (EMD(HS)), variance of building chromaticity (Var(HS)_Building), and directional mismatch (EMD(θ)). The relationships between each domain indicator and ΔF1 are illustrated in

Figure 7.

ΔF1 vs. ΔMean V (Brightness Bias): As the inter-domain brightness variation (ΔMean V) increased, ΔF1 tended to increase, indicating a positive association. This pattern is consistent with histogram matching enhancing radiometric stability compared with PA by mitigating inter-domain brightness discrepancies through global histogram normalization. For both the OEM and KOMPSAT-3A datasets, the performance gain in ΔF1 increased with greater brightness differences, suggesting that the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method helps mitigate radiometric discrepancies between domains caused by brightness variations.

ΔF1 vs. EMD(HS) (Color Distribution Distance): As the color and saturation distribution difference EMD(HS) increased, ΔF1 showed an increasing trend, indicating a positive association. This trend is consistent with histogram matching reducing color bias by normalizing the mean and variance of the color distribution in the training domain toward the statistical distribution of the target domain. Furthermore, OBA may contribute additional performance gains over PA by enhancing intra-object color diversity, resulting in improved robustness to color and radiometric variations across domains.

ΔF1 vs. Var(HS)_Building (Chroma Diversity): Regarding building chromatic diversity, ΔF1 remained stable across varying levels of chromatic variation, as shown in

Figure 7c, indicating no clear association or fluctuation between the two variables. This suggests that the proposed method maintains positive performance gains even when chromatic diversity varies. This stability is consistent with the OBA process increasing the structural diversity of objects and improving model robustness under diverse geometric and illumination conditions. Additionally, the HM stage performs global chromatic normalization, stabilizing the mean and variance of the color distribution and minimizing color variability across domains.

ΔF1 vs. EMD(θ) (Orientation Distribution Shift): As the directional distribution difference EMD(θ) increased, ΔF1 tended to increase, as illustrated in

Figure 7d, indicating a positive association. This trend is consistent with the combination of two-stage geometric enhancement

and object replacement (OBA) being beneficial under larger orientation shifts. In particular, for the KOMPSAT-3A dataset, in inter-city transfer cases such as I + J→S, where EMD(θ) values were large, ΔF1 exceeded +0.25, showing a substantial performance improvement over PA. These observations suggest that the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method can maintain strong performance gains even in domains exhibiting significant geometric discrepancies.

As the number of transfer scenarios is limited, we retained all points in

Figure 7 and interpreted high-variance cases as informative rather than removing them. As a robustness check, we computed Spearman’s rank correlation between

and each domain indicator. The rank-based associations remained positive for

Mean V (

) and EMD(HS) (

), whereas Var(HS)_Building showed no monotonic relationship (

).

Across all four domain indicators, ΔF1 exhibited positive or statistically stable performance improvements, and the proposed method consistently outperformed PA across the dimensions of brightness, color, and geometry. In particular, the largest positive slopes were observed along the EMD(HS) and EMD(θ) axes, suggesting that the relative performance advantage of the proposed method becomes more pronounced as color and directional mismatches increase. Consequently, the Hybrid (OBA + HM) method achieved improved cross-domain generalization performance over PA across diverse domain factors by combining global brightness normalization and two-stage geometric enhancement

. This trend is further supported in the normalized domain-indicator analysis presented in

Section 3.5.2, which suggests that the configuration

is a robust and broadly applicable parameter setting within the evaluated OEM and KOMPSAT-3A scenarios. We emphasize that these trends indicate correlation rather than causation; since the indicators may covary, a more rigorous multivariate analysis (e.g., partial correlation or regression with collinearity control) is left for future work.

3.5.2. Normalized Domain-Indicator Heatmap

Figure 8 shows the comparison results of the domain indicators—ΔMean V, ΔStd V, EMD(HS), Var(HS)_Building, EMD(log A), and EMD(θ)—normalized to a 0–100 range for six OEM (global) scenarios and three KOMPSAT-3A (regional) scenarios. The purpose of this analysis is to quantitatively compare the relative discrepancies of brightness, color, and directional factors across each dataset and scenario, thereby identifying the dominant discrepancy patterns of each domain group.

The normalization results showed that the OEM scenarios exhibited low values for most indicators, ranging between 0 and 25%, indicating a homogeneous domain with minimal brightness, color, and orientation discrepancies. In contrast, the KOMPSAT-3A scenarios showed values of ΔMean V, ΔStd V, EMD(HS), Var(HS)_Building, and EMD(θ) mostly ranging from 30 to 100%. Several indicators exhibited high deviations exceeding 60%, indicating a high-discrepancy domain characterized by significantly greater composite mismatches than the OEM domain. These results suggest that the OEM dataset represents a globally radiometrically consistent and structurally homogeneous environment, whereas the KOMPSAT-3A dataset represents a more complex environment with combined radiometric and geometric variations arising from urban structural diversity and differences in imaging conditions.

In the OEM scenarios, ΔMean V (0–16.9%), ΔStd V (0–24.4%), EMD(HS) (0–21.5%), and EMD(θ) (0–21.6%) all showed low levels, indicating an overall homogeneous domain with minimal inter-regional differences in illumination, color, and directionality. Var(HS)_Building showed an intermediate level (0–69%), and EMD(log A) also exhibited intermediate values; however, in some scenarios (e.g., S5, S6), relatively high values around 90% (89–100%) were observed, indicating partial deviations in building area distributions. These findings demonstrate that the OEM domain is generally a low-discrepancy environment with minimal radiometric and geometric mismatches, although certain scenarios show regional variations in building area distributions. Furthermore, the orientation mismatch EMD(θ) was nearly absent, indicating that building orientation was consistently maintained across domains. Accordingly, the HM stage of the Hybrid (OBA + HM) method contributes to maintaining radiometric consistency within the OEM domain by correcting subtle brightness and color deviations rather than applying extreme normalization.

In the KOMPSAT-3A scenarios, significantly greater deviations were observed across all major indicators compared with the OEM scenarios. ΔMean V (30.3–100%) and ΔStd V (33.7–100%) showed substantial brightness and illumination differences between cities, while EMD(HS) (24.8–100%) revealed strong radiometric mismatches due to substantial variation in color distribution range and centroid. Additionally, Var(HS)_Building (33–100%) and EMD(θ) (2.5–100%) indicated simultaneous increase in the internal chromatic diversity of buildings and mismatches in building orientations, demonstrating that radiometric and geometric factors act in a strongly coupled manner across the regional domain. To mitigate these compound mismatches, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method reduced structural and orientation discrepancies between cities by combining OBA for structural diversification and two-stage geometric enhancement . Furthermore, the HM stage globally normalized brightness and color distributions, thereby mitigating radiometric mismatches between domains and complementarily reinforcing the effects of both the OBA and geometric enhancement stages. As a result, within the KOMPSAT-3A domain, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method achieved a significantly greater radiometric and geometric adaptability gain than in the OEM domain. The combined effects of brightness and color normalization (HM) and object-based structural and directional correction (OBA and geometric enhancement) enabled stable and consistent cross-domain generalization performance, even under highly complex radiometric–geometric discrepancy conditions.

The OEM (Global) domain can be characterized as a radiometric-dominant domain, exhibiting low deviations in brightness, color, and directionality, where the HM stage effectively contributed to global brightness and color normalization. In contrast, the KOMPSAT-3A (Regional) domain can be classified as a radiometric–geometric composite domain, showing substantially greater deviations not only in brightness and color but also in internal chromatic diversity and orientation mismatches compared with the OEM domain. In this domain, OBA combined with multi-stage geometric enhancement () effectively alleviated structural and directional mismatches, while HM compensated for radiometric biases through global brightness and color normalization. Consequently, the proposed Hybrid (OBA + HM) method was identified as a globally robust configuration that adaptively responds to both radiometric and geometric factors, achieving stable and consistent cross-domain generalization performance across both global and regional domains.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role and Implications of Object-Based Augmentation

Object-based augmentation (OBA) plays a key role in ensuring structural diversity of buildings by generating diverse building instances from limited training datasets. In the OEM and KOMPSAT-3A datasets, the mean IoU between replaced and original building polygons is approximately 0.895 and 0.887, respectively, with a standard deviation below 0.05. This suggests that the size, shape, and location of the replaced objects are well aligned with those of the original buildings. This suggests that, unlike simple random replication-based augmentation, OBA increases structural diversity while maintaining object-level geometric consistency. In addition, OBA uses object-count-based coverage filtering to select augmented images with a high proportion of building objects, which alleviates the bias toward the background class during loss computation and increases the effective contribution of the building class during training.

In the KOMPSAT-3A inter-city transfer experiments, where building density and occupancy rates vary significantly, the Hybrid OBA–HM scheme substantially improved the average F1-score compared with the baseline while simultaneously reducing its standard deviation. This suggests more stable performance in our experiments even in environments with pronounced inter-domain structural variations in density, shape, and layout. In summary, OBA functions as a data-level module that compensates for structural domain differences without altering the network architecture, thereby directly contributing to improved domain generalization performance within the evaluated settings.

4.2. Hybrid Response to Radiometric-Geometric Complex Mismatch