Finite Element Analysis of Tire–Pavement Interaction Effects on Noise Reduction in Porous Asphalt Pavements

Abstract

1. Introduction

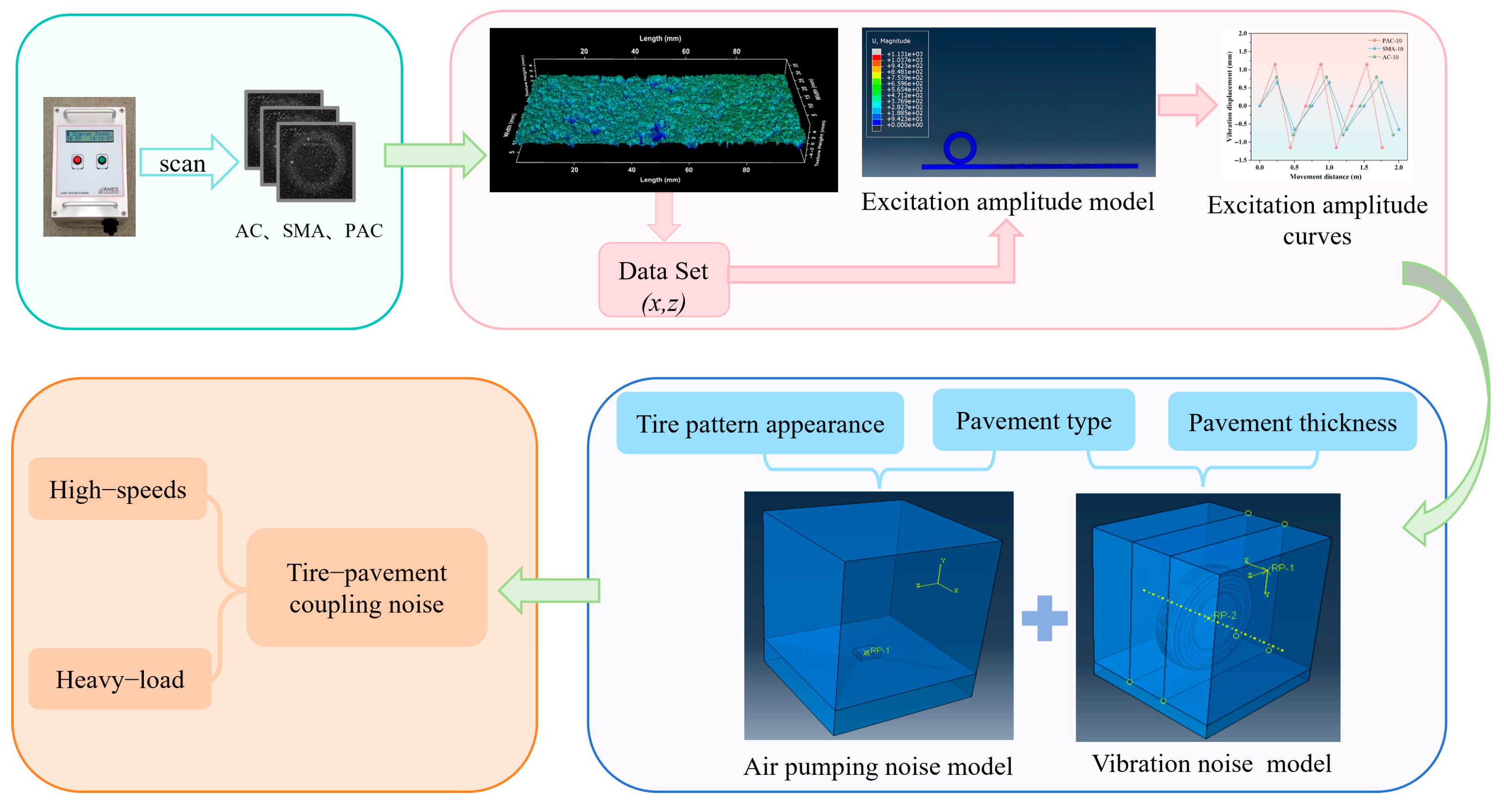

2. Materials and Methods

3. Tire–Pavement Coupling Noise Finite Element Modeling

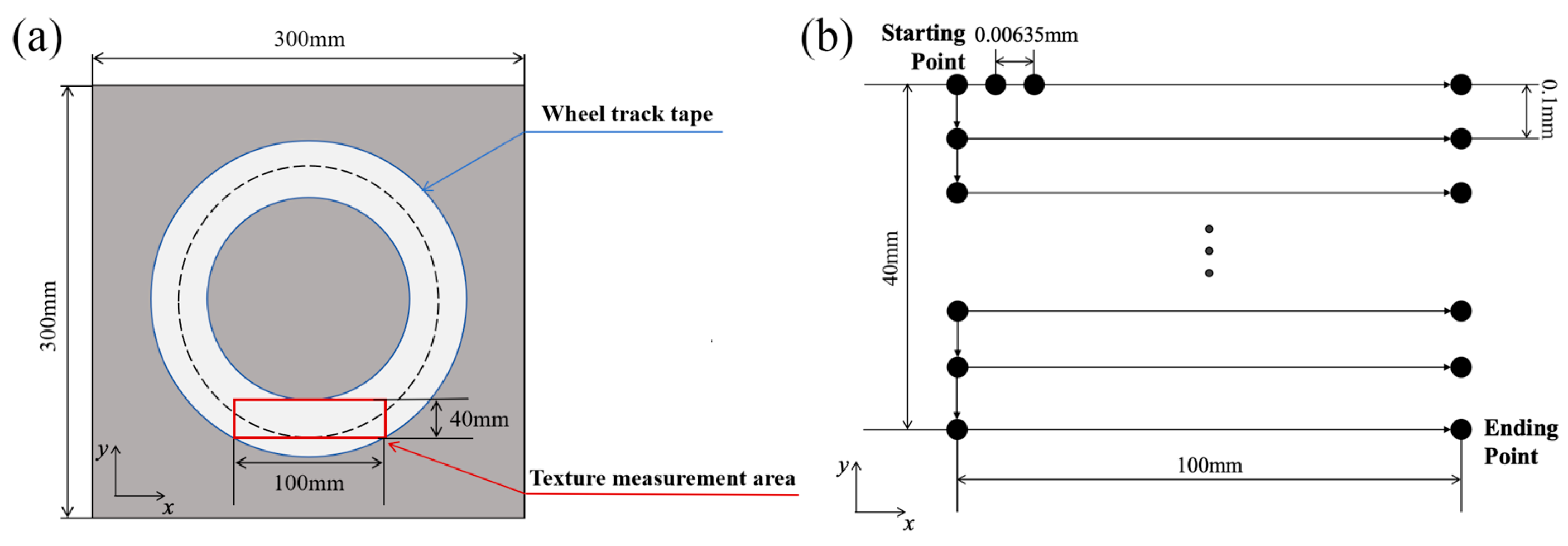

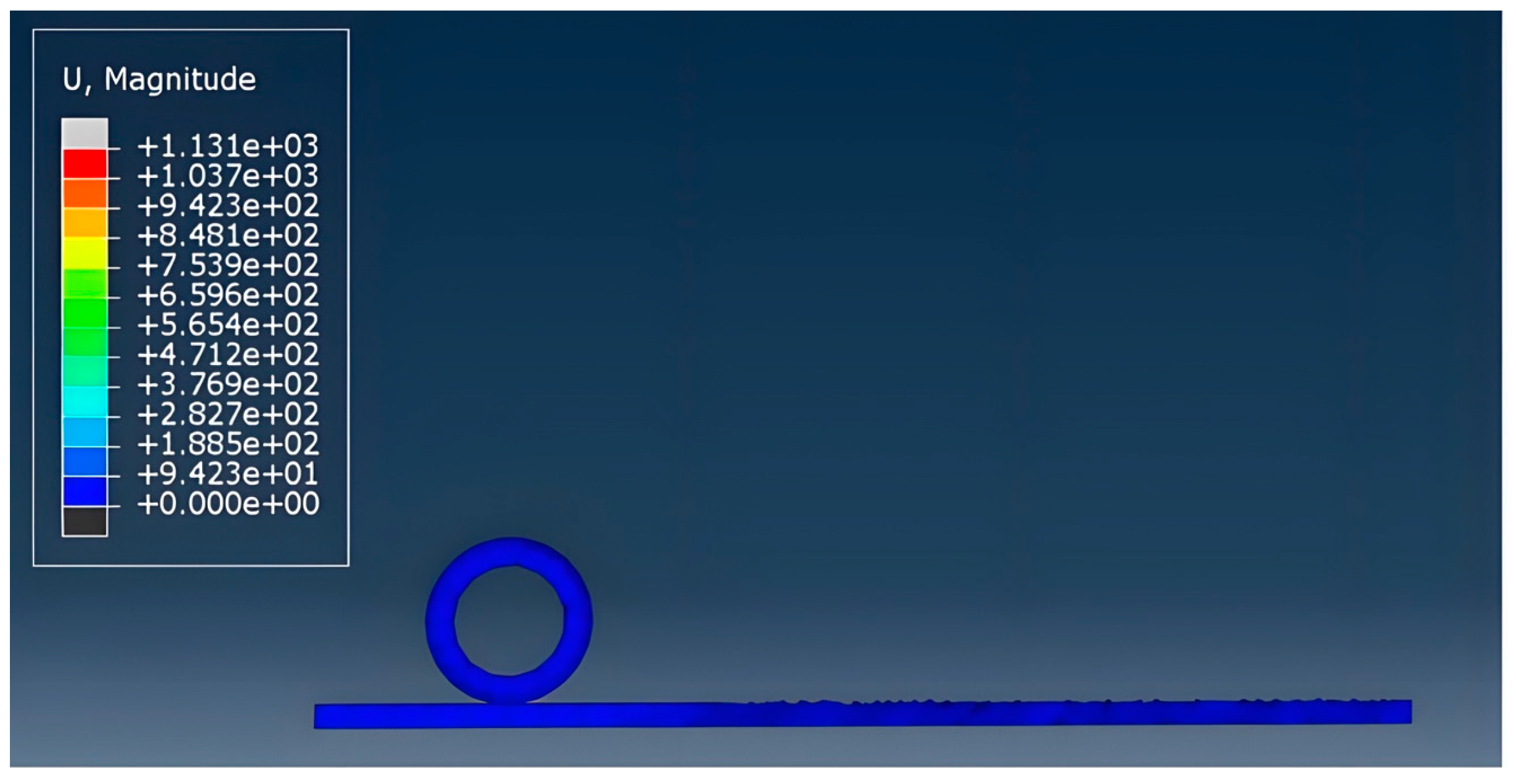

3.1. Finite Element Modeling of Tire–Pavement Vibrational Excitation Based on Surface Texture

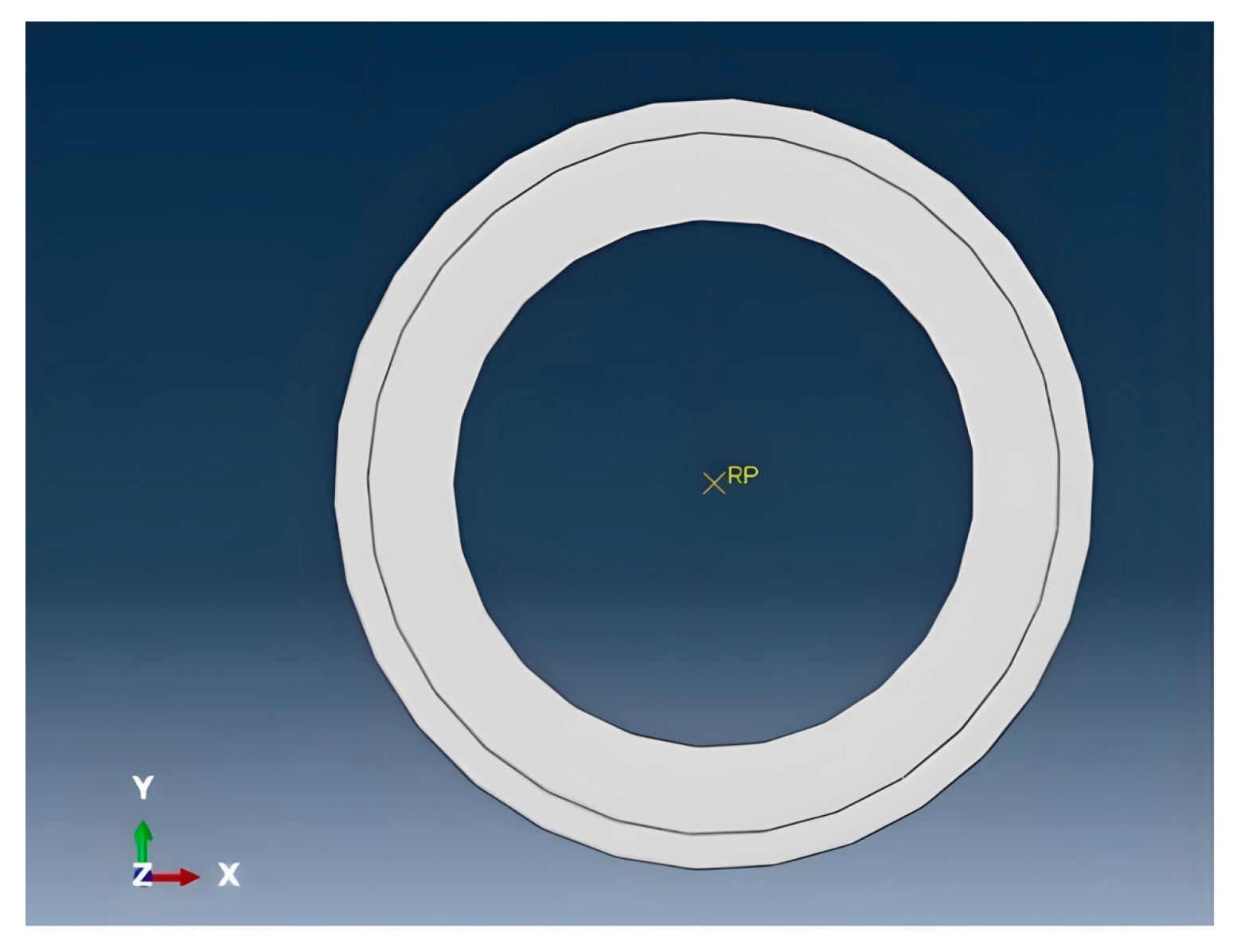

3.1.1. Two-Dimensional Tire Model

3.1.2. Two-Dimensional Pavement Model

3.1.3. Extraction of Pavement Excitation Amplitude Curves

3.2. Finite-Element Modeling of Tire–Pavement Vibration Noise

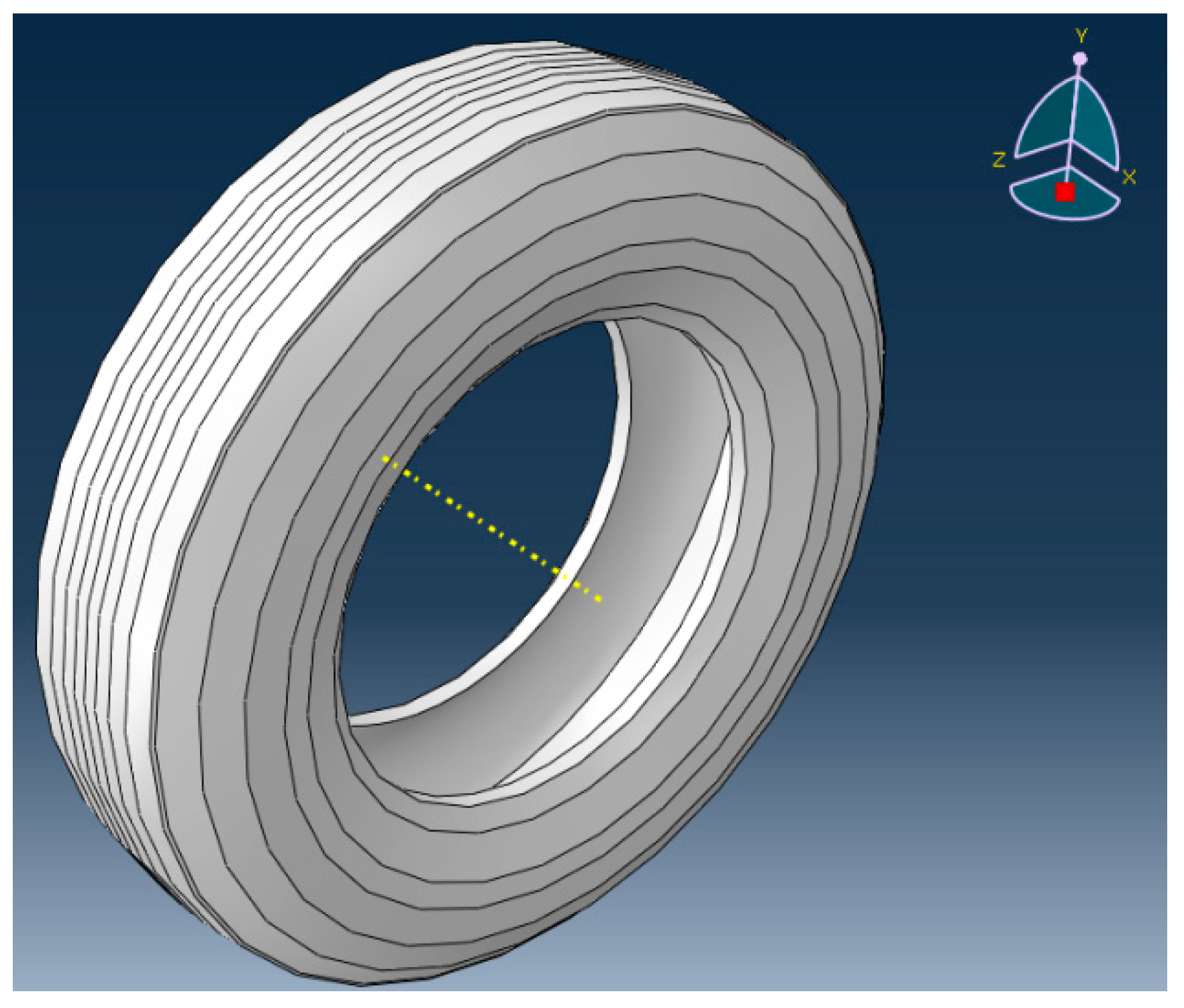

3.2.1. Three-Dimensional Tire Model

3.2.2. Three-Dimensional Pavement Model

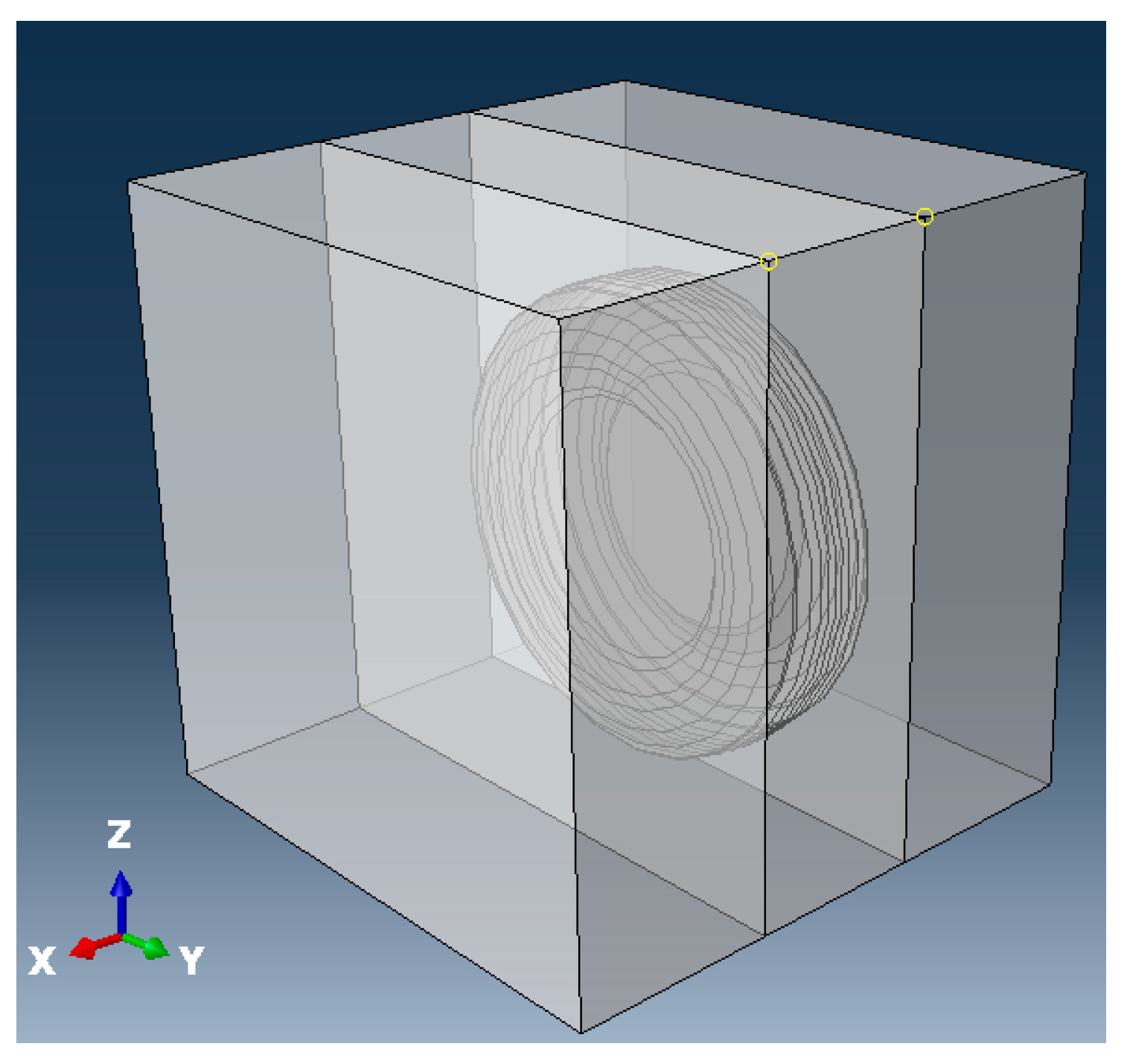

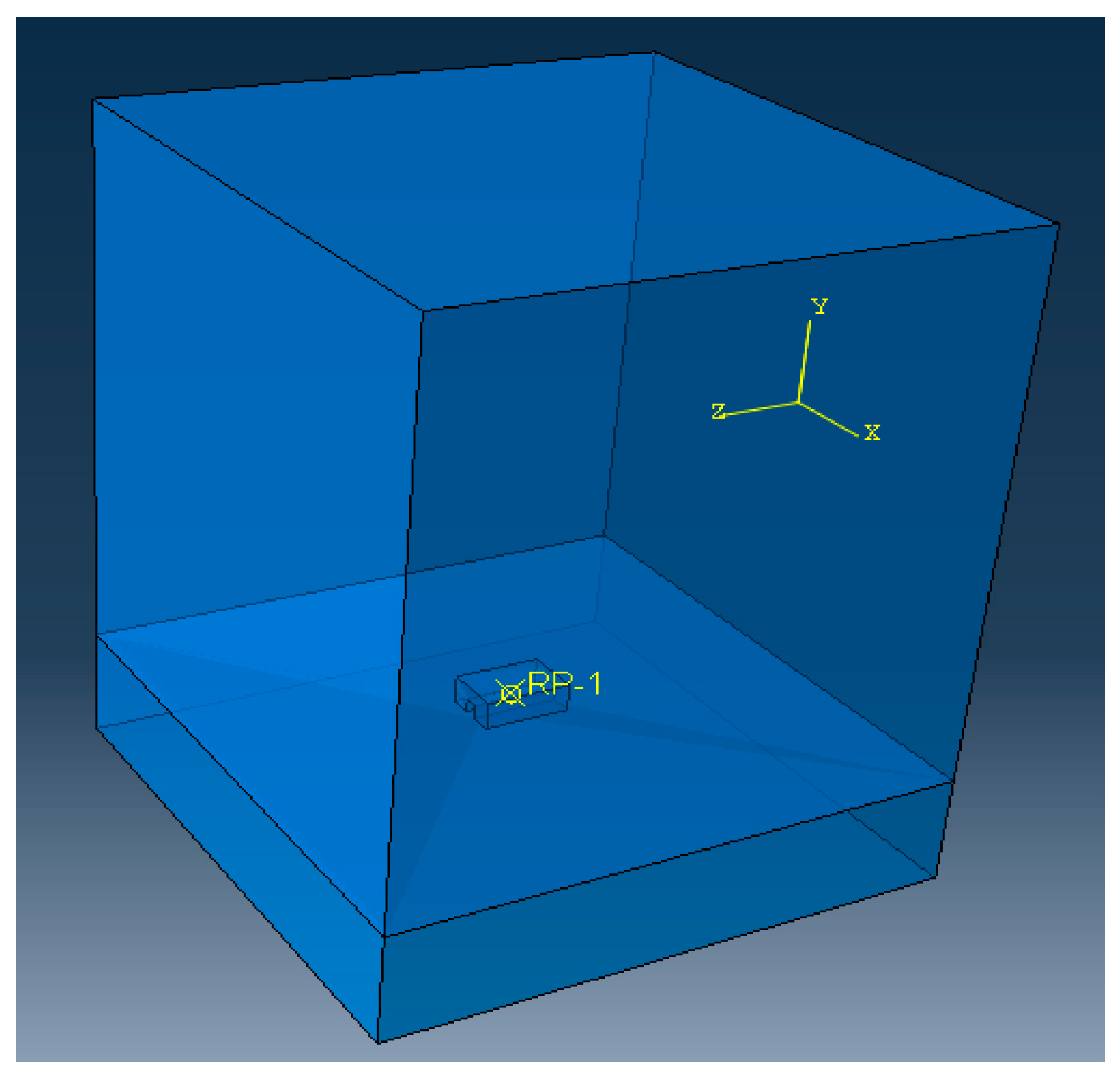

3.2.3. Three-Dimensional Air Model

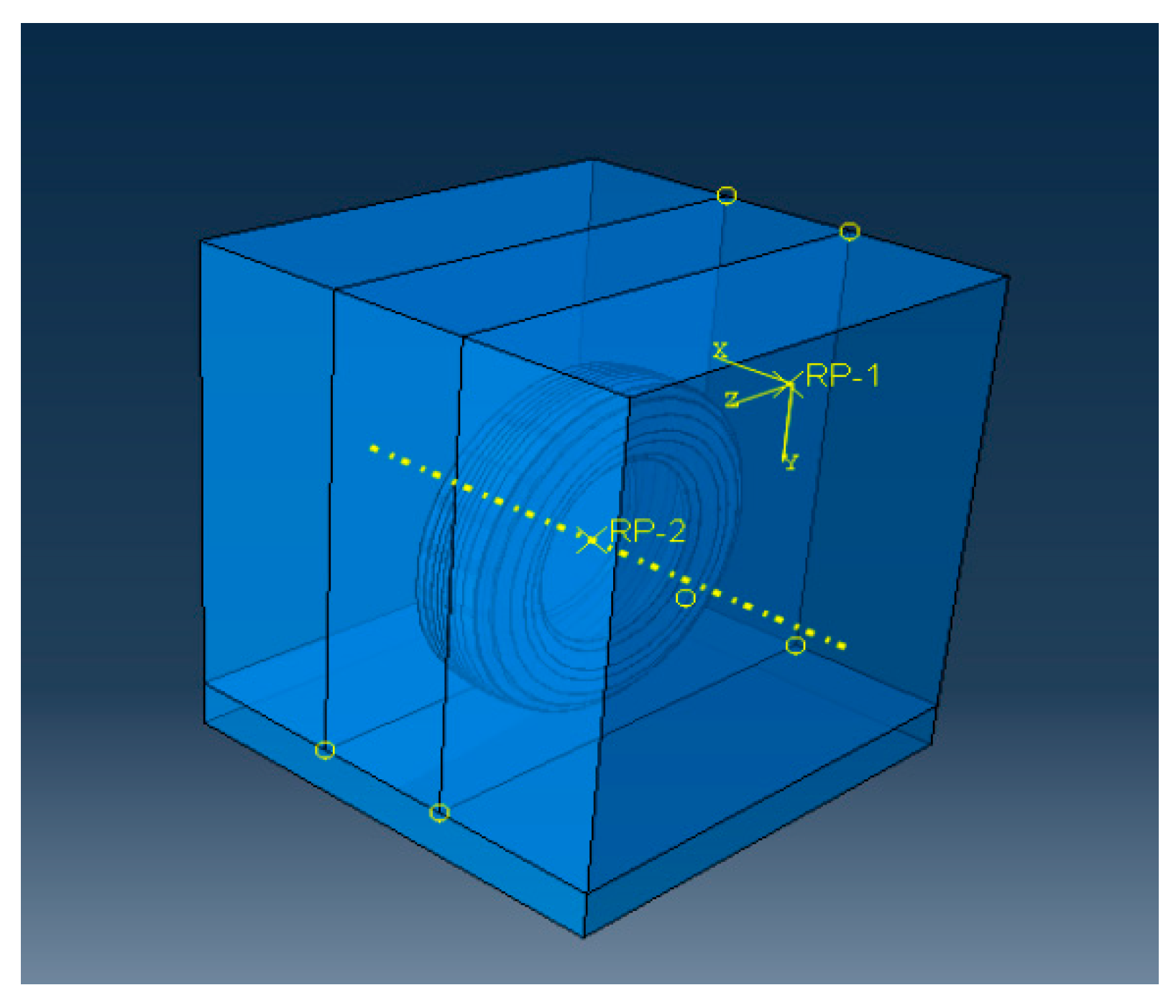

3.2.4. Assembly Model and Boundary Condition Configuration

3.3. Finite Element Modeling of Air Pumping Noise

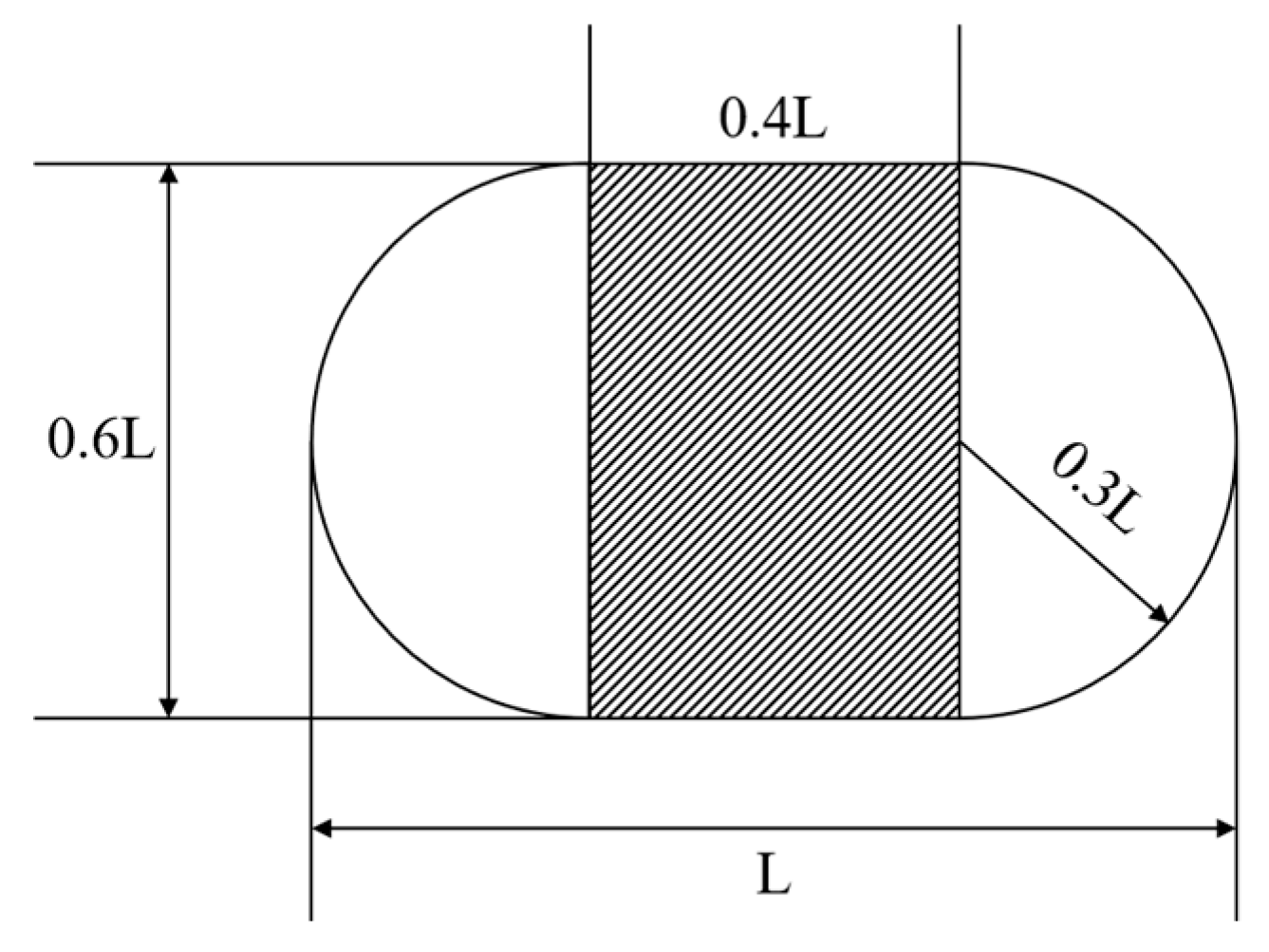

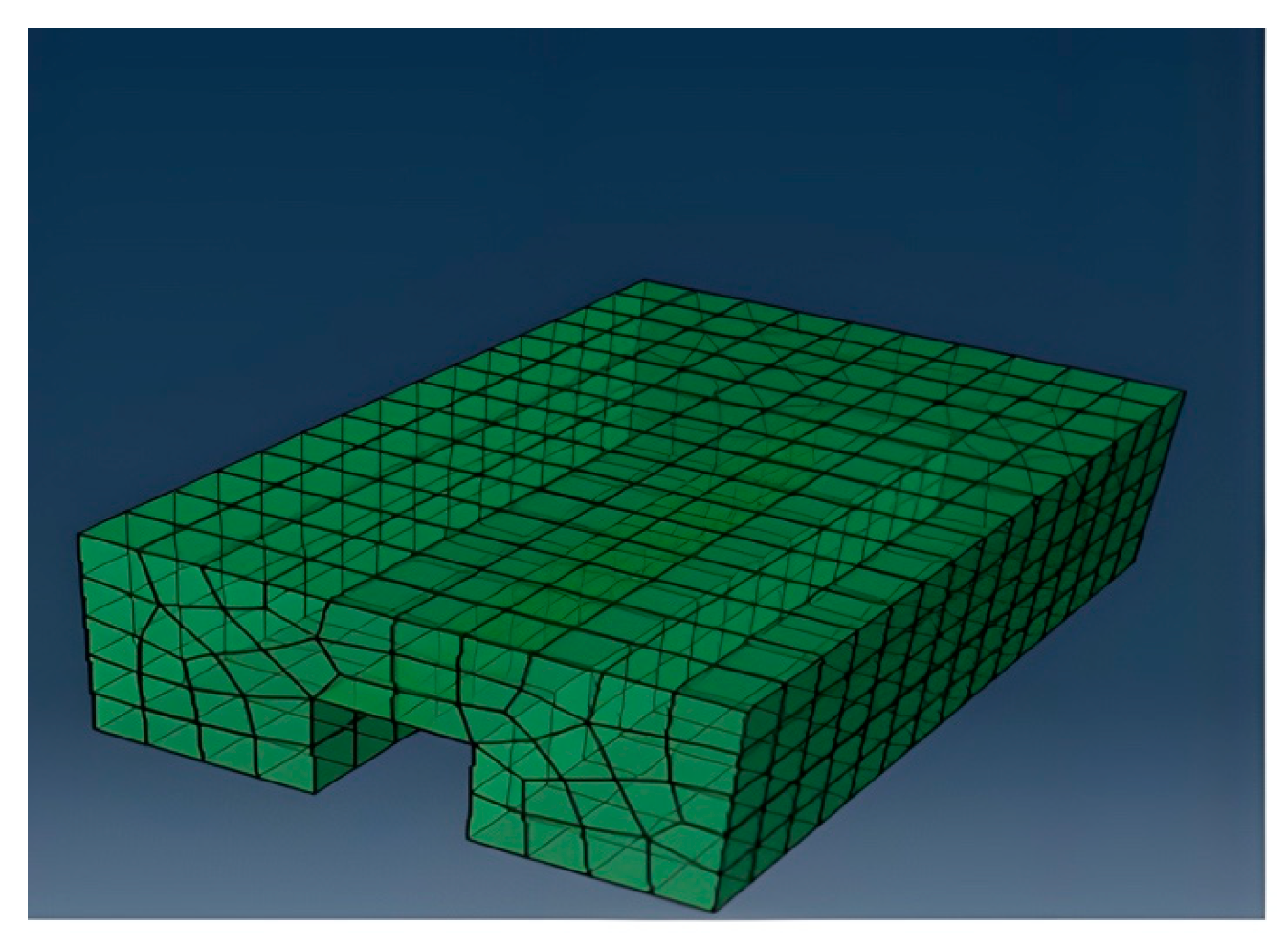

3.3.1. Tire Pattern Block Model

3.3.2. Model Assembly and Boundary Condition Configuration

3.4. Synthesis of Noise

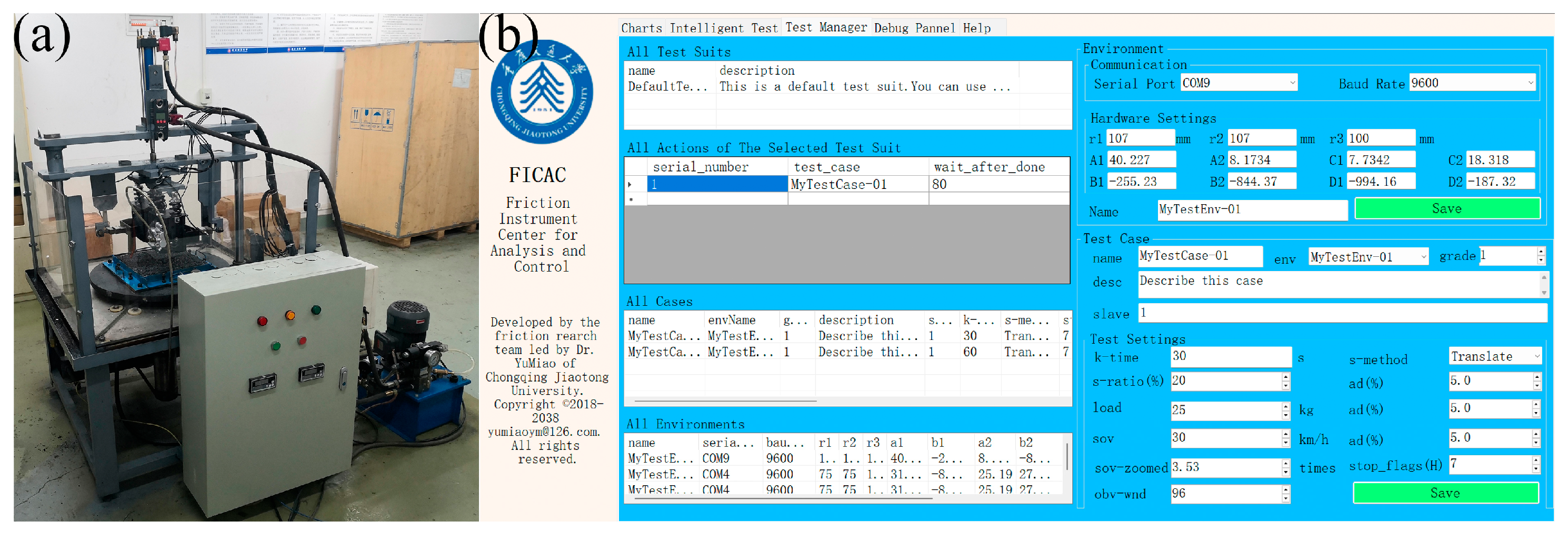

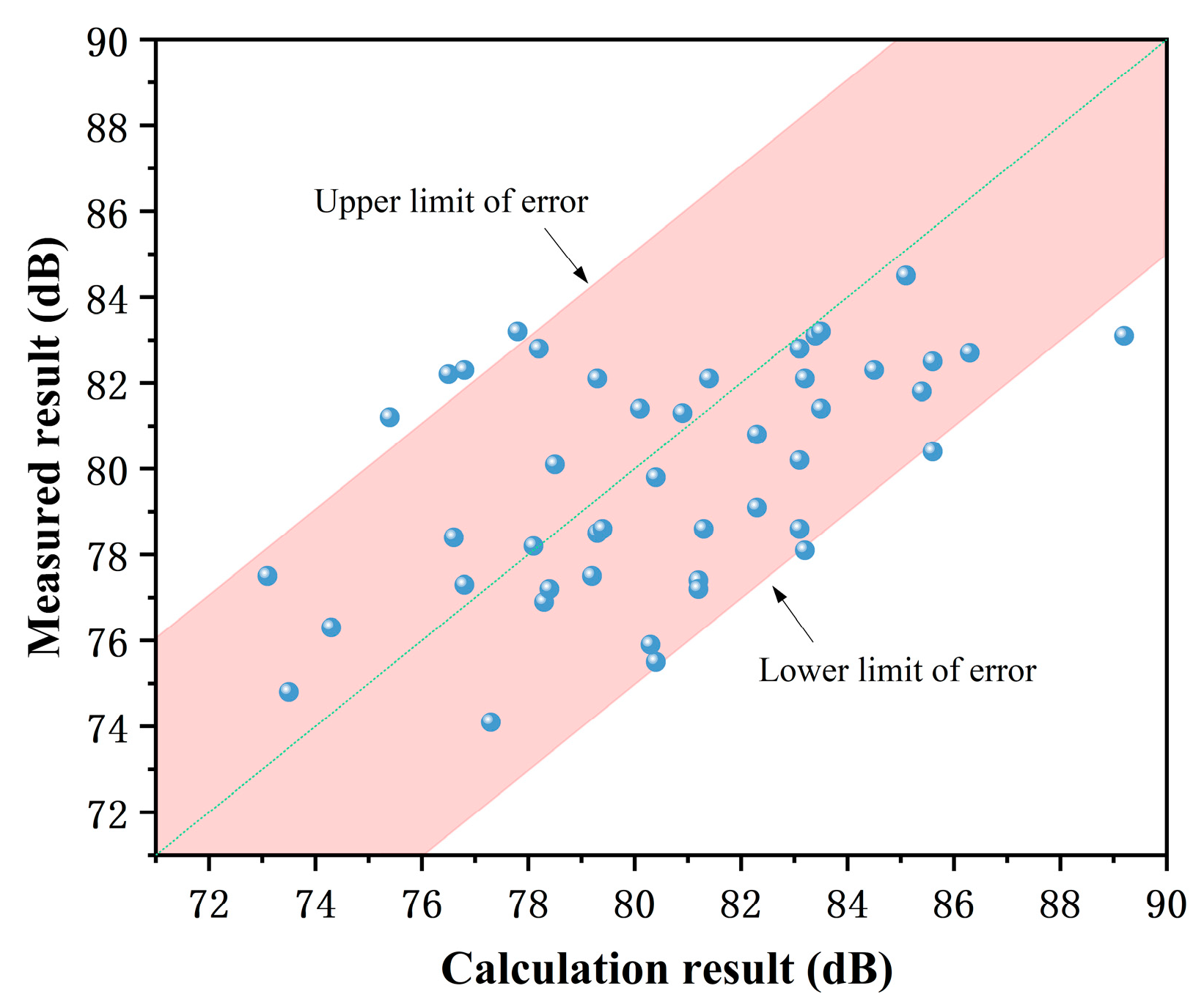

3.5. Model Validity Test

4. Results and Analysis

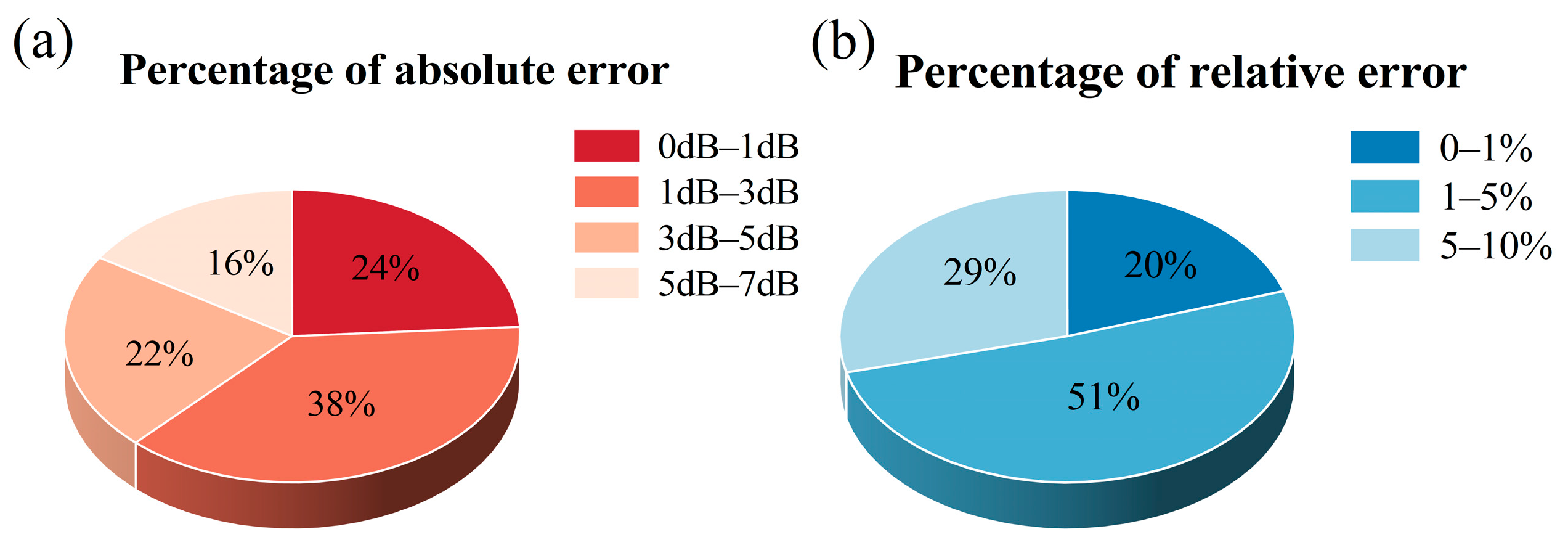

4.1. Model Validity Verification

4.2. Excitation Amplitude Curves

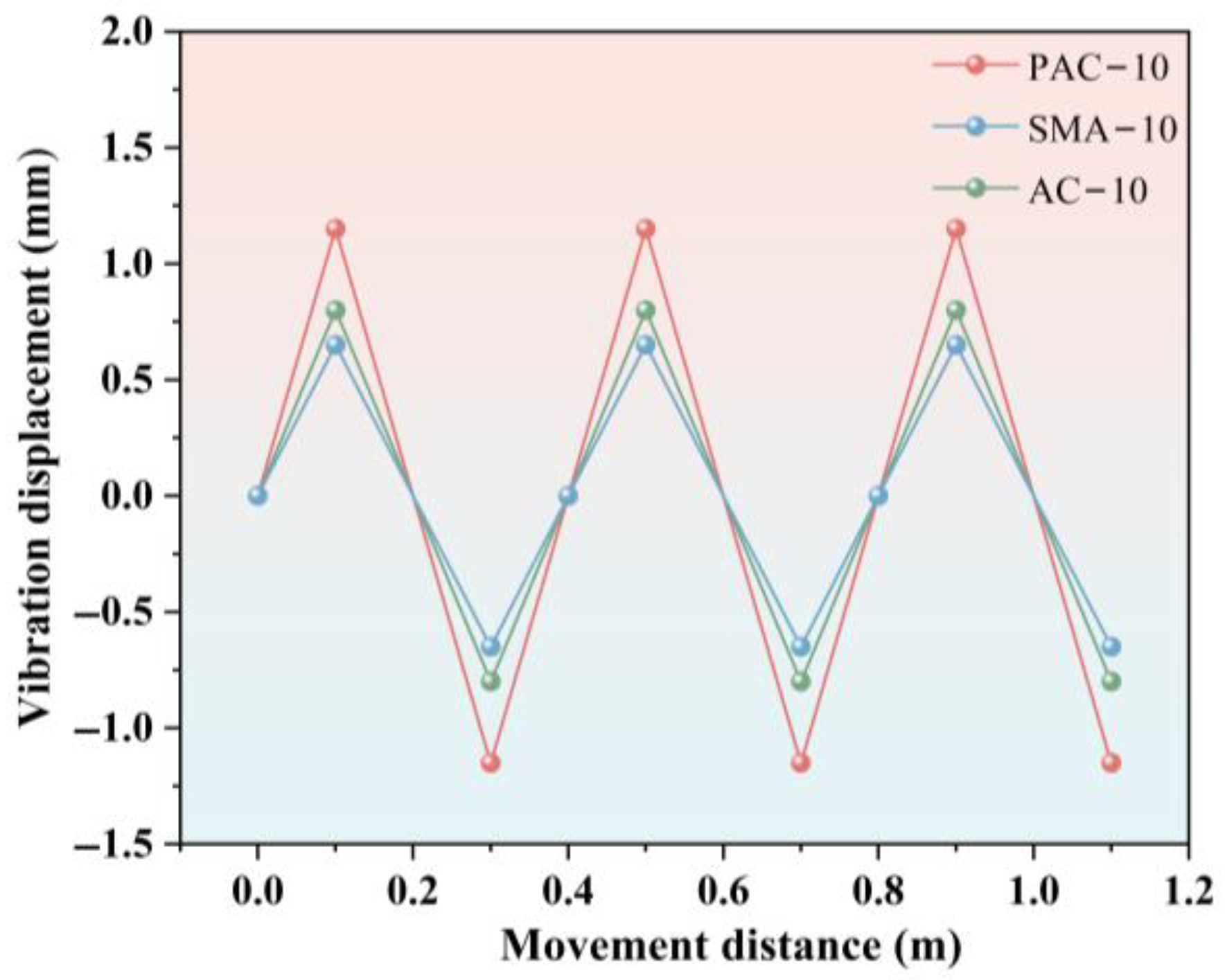

4.3. Vibration Noise Analysis

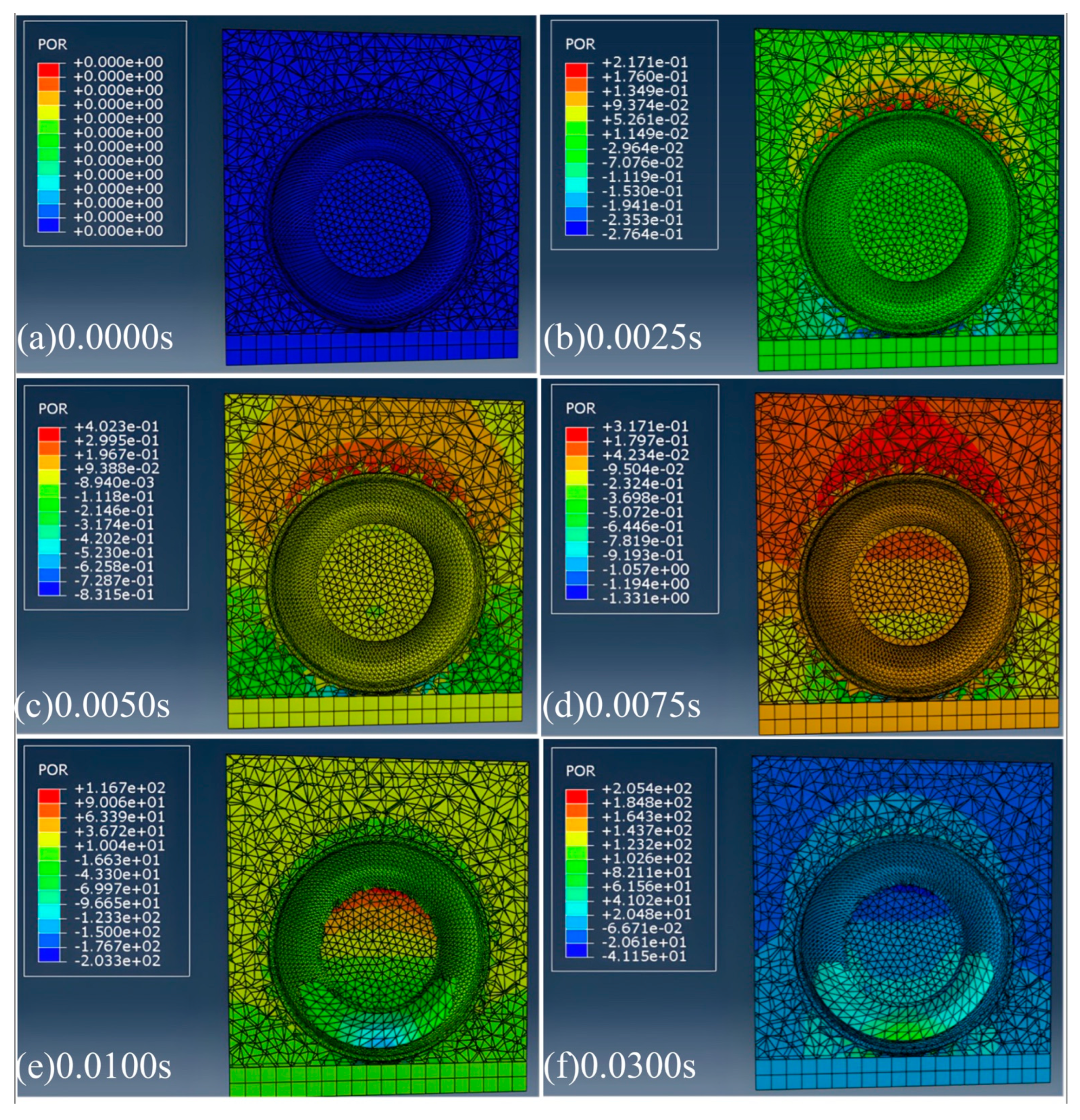

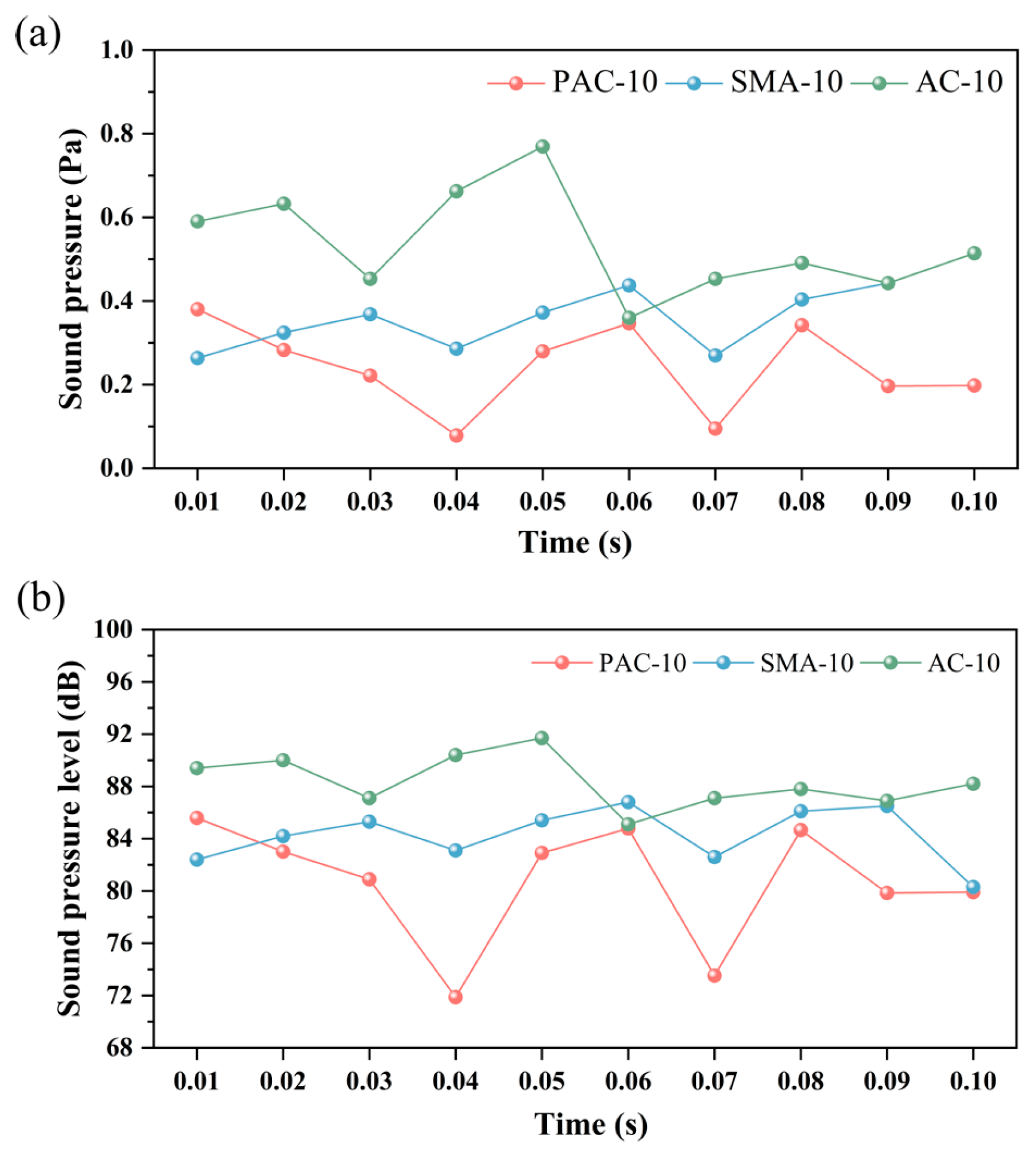

4.3.1. Vibration Noise Sound Pressure Contour Analysis

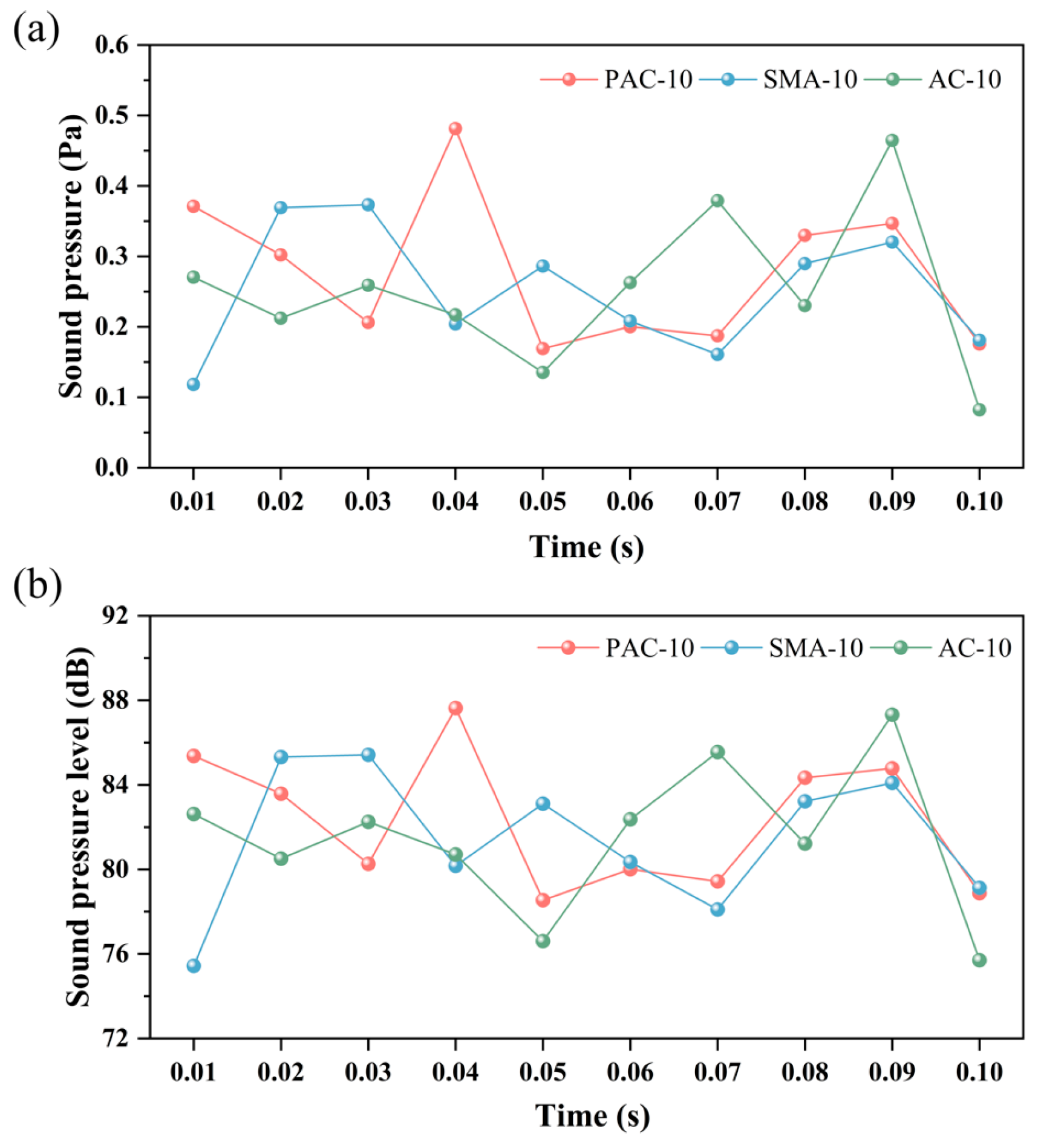

4.3.2. Comparative Analysis of Vibration Noise of Different Pavement Types

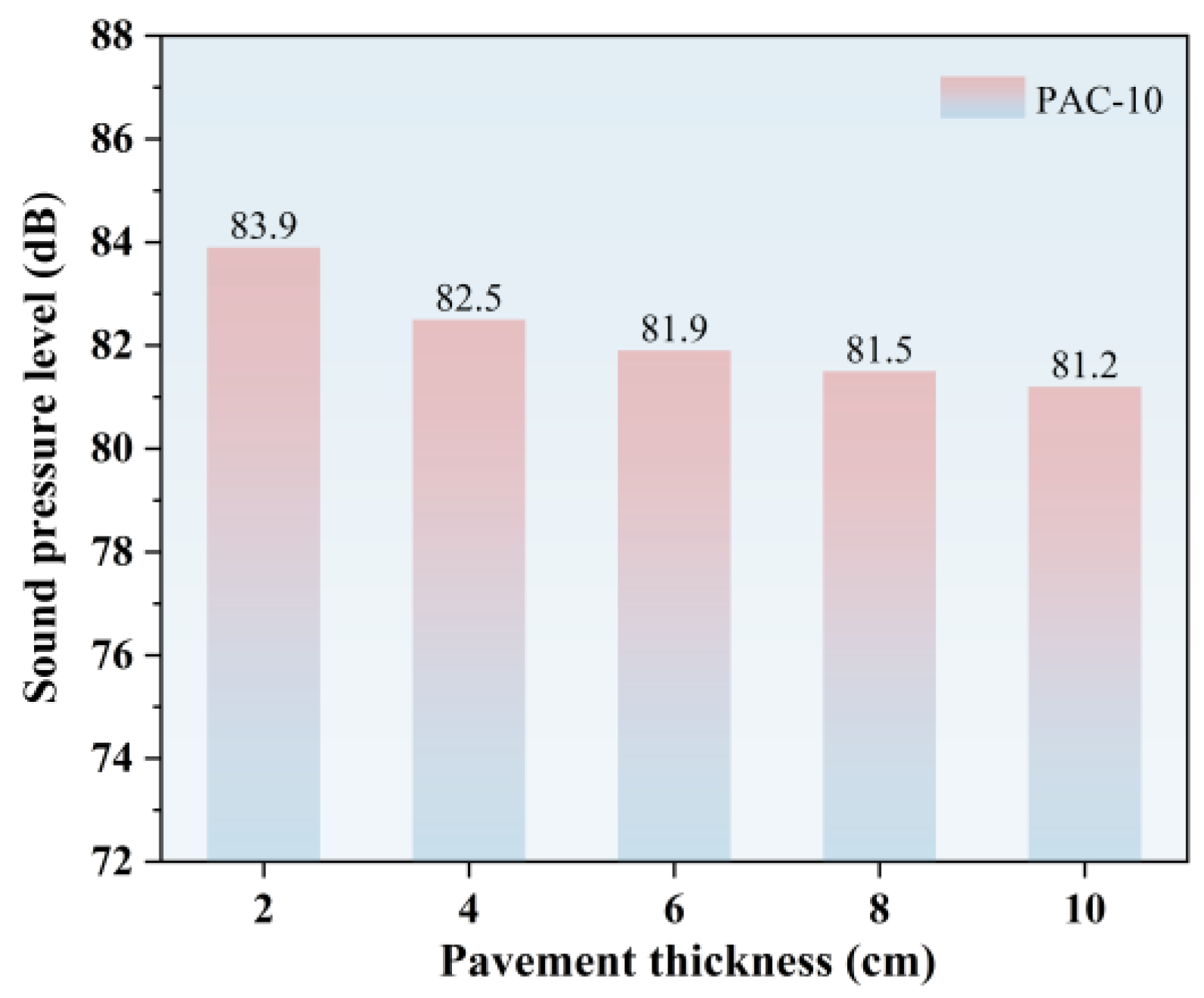

4.3.3. Influence of Pavement Thickness on Vibration Noise

4.4. Air Pumping Noise Analysis

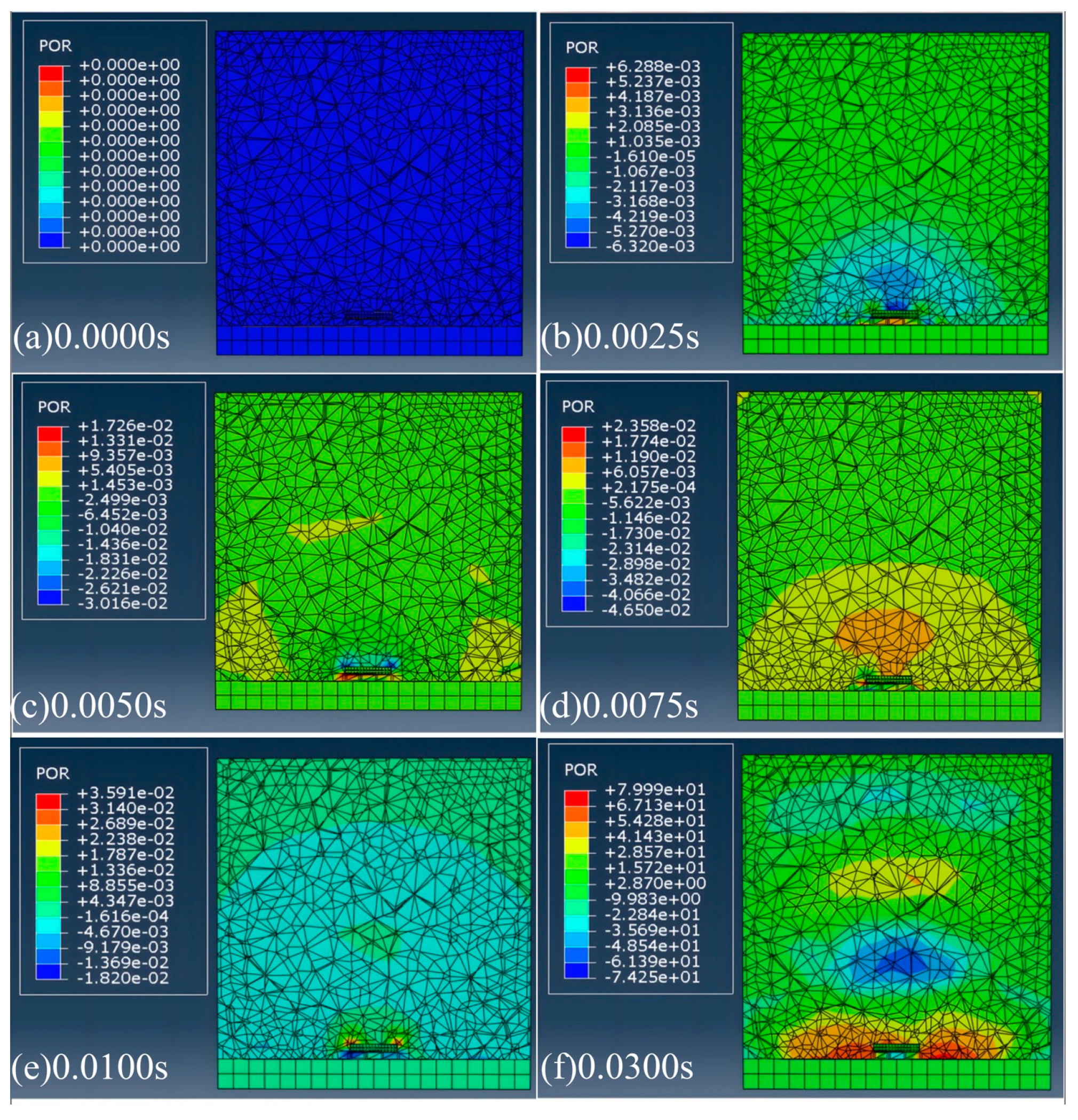

4.4.1. Air Pumping Noise Sound Pressure Contour Analysis

4.4.2. Comparative Analysis of Air Pumping Noise of Different Pavement Types

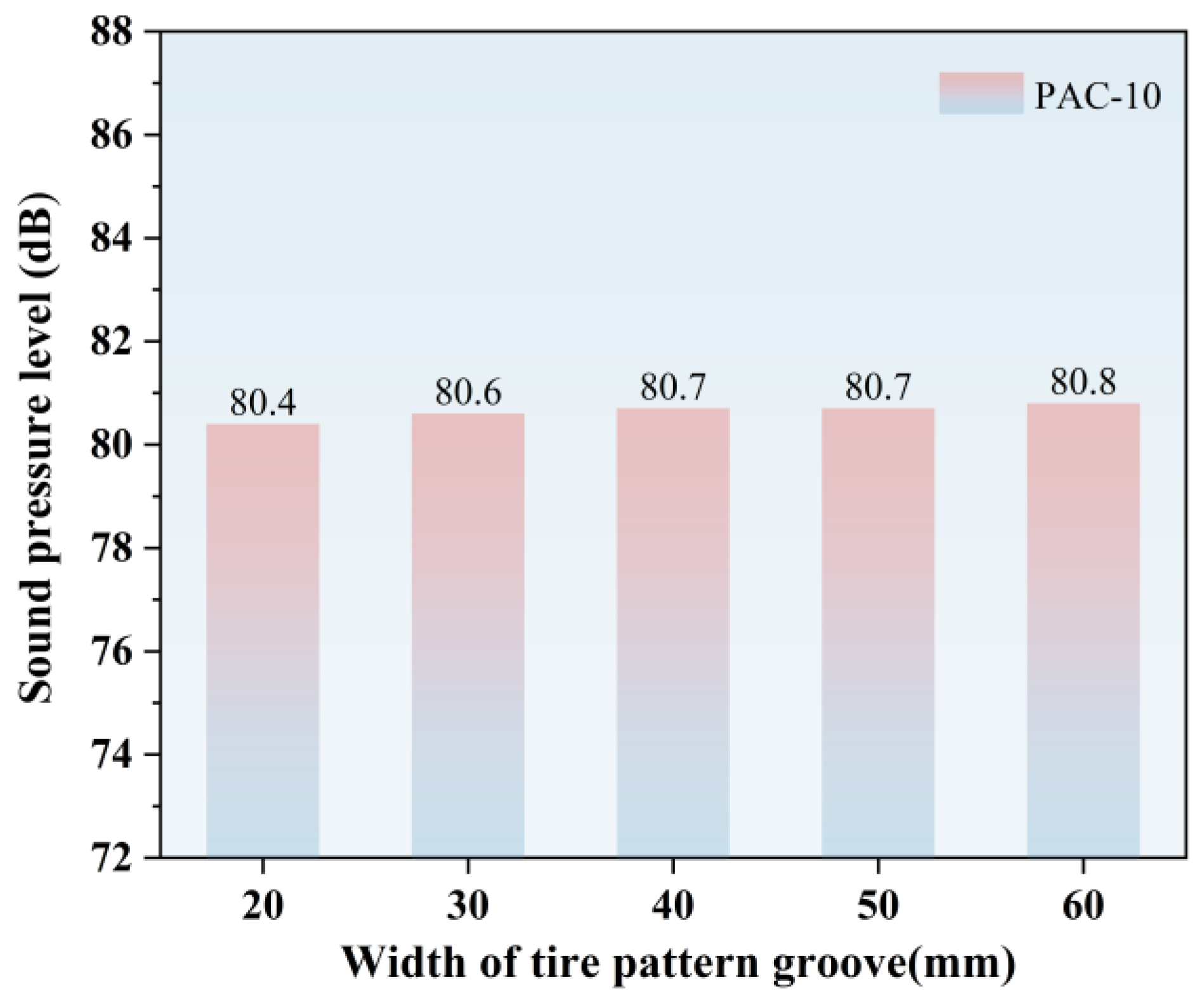

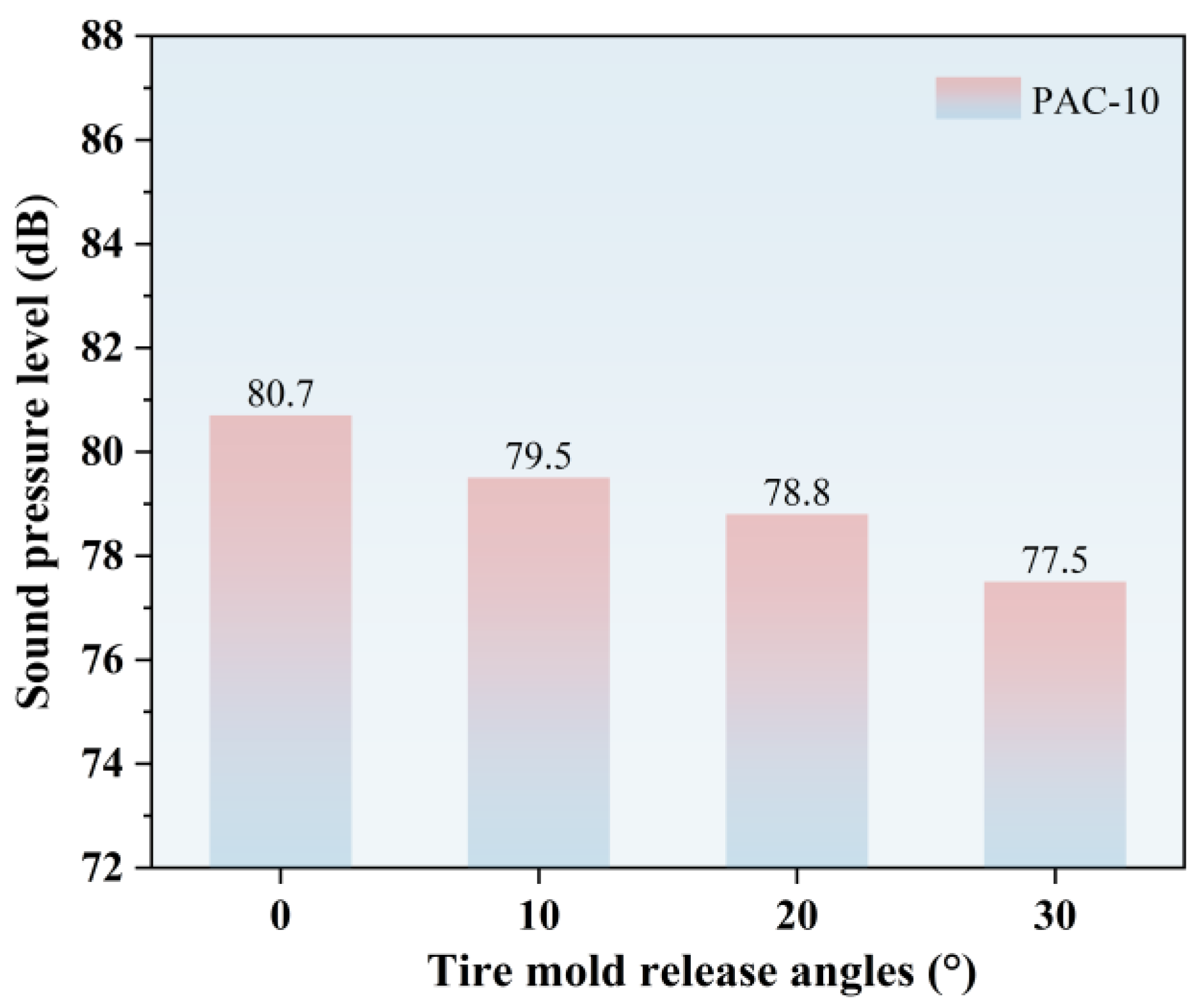

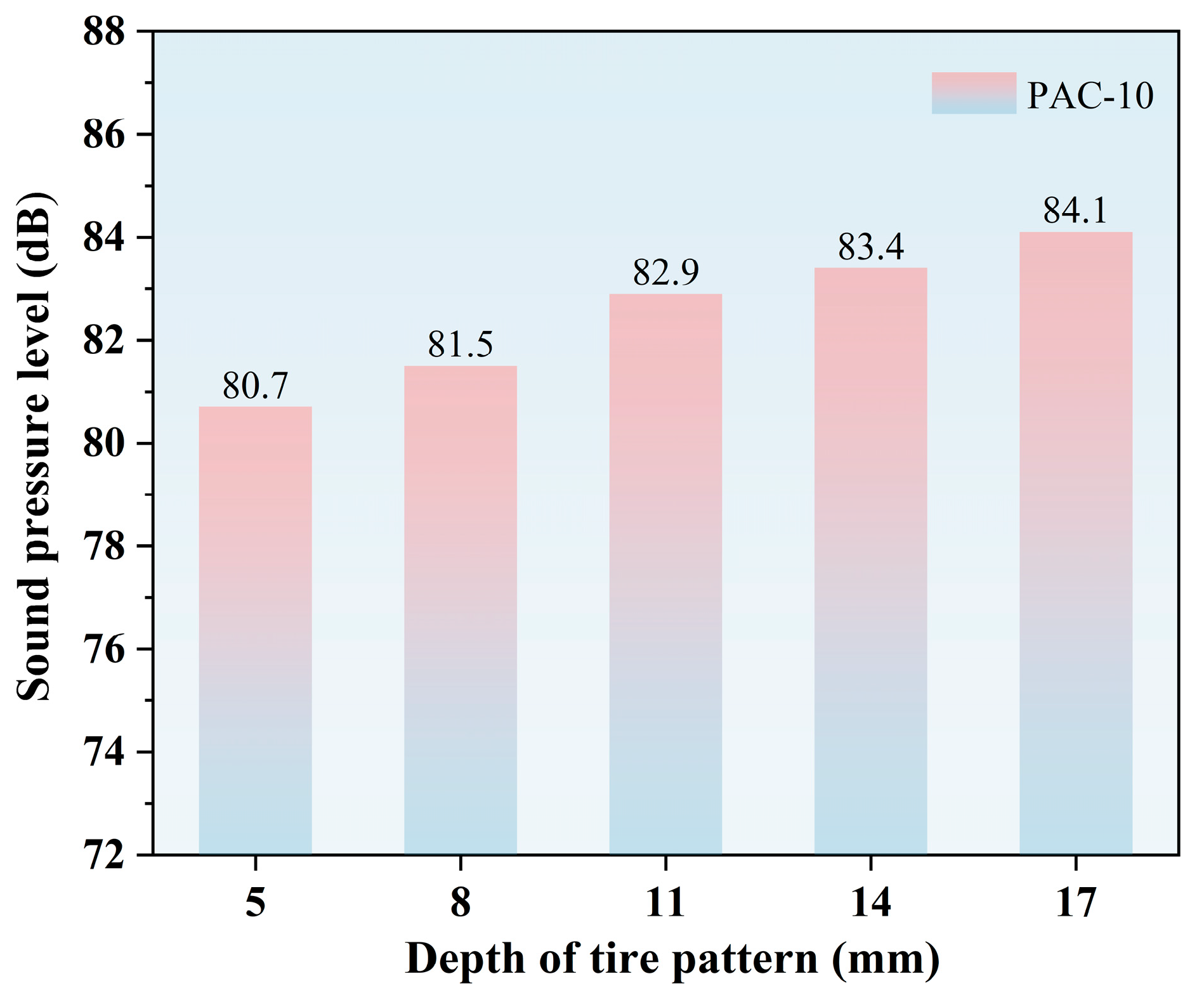

4.4.3. Influence of Tire Pattern Appearance on Air Pumping Noise

4.5. Tire–Pavement Coupling Noise Analysis Based on Simulation Models

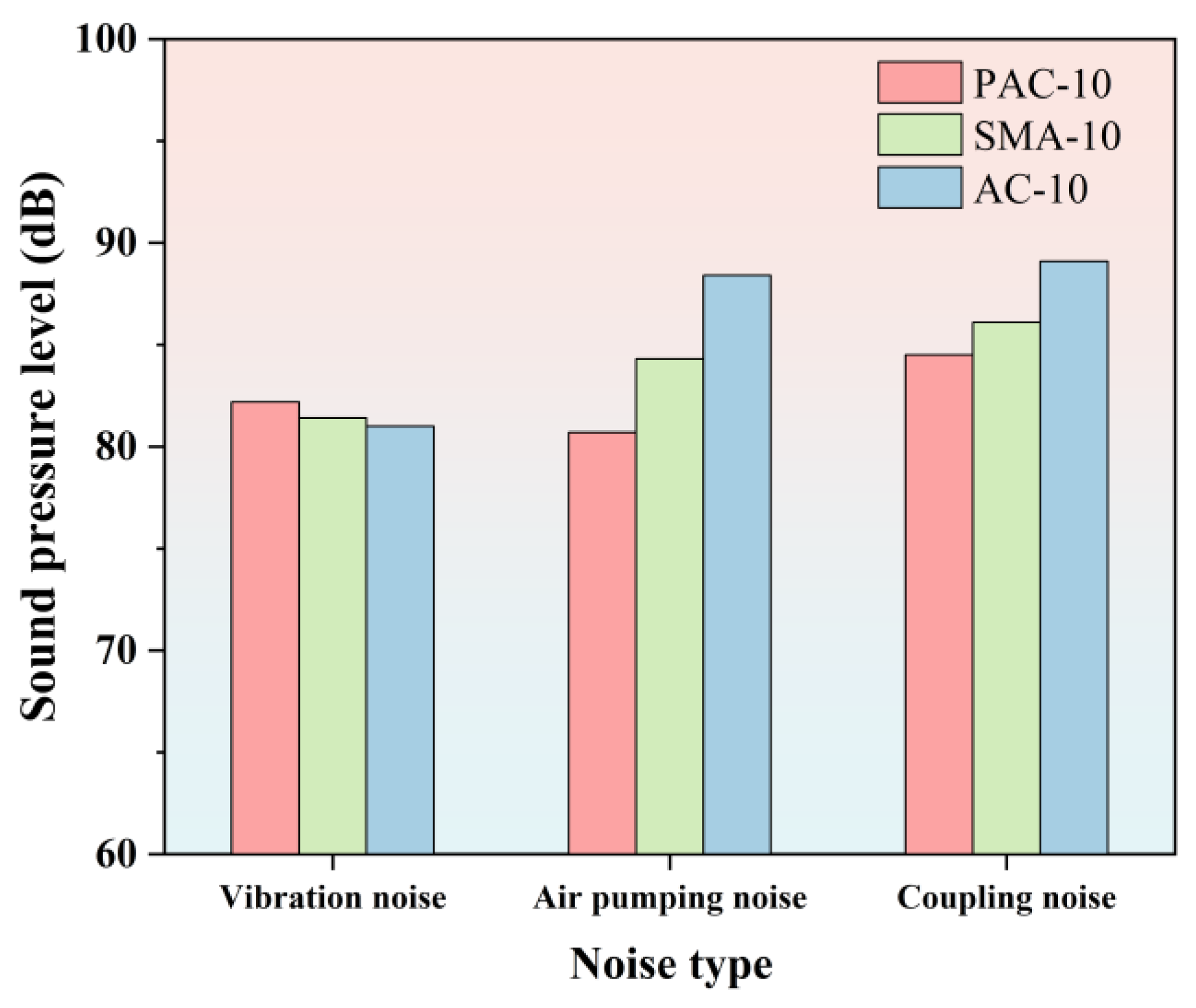

4.5.1. Comparative Analysis of Tire–Pavement Coupling Noise of Different Pavement Types

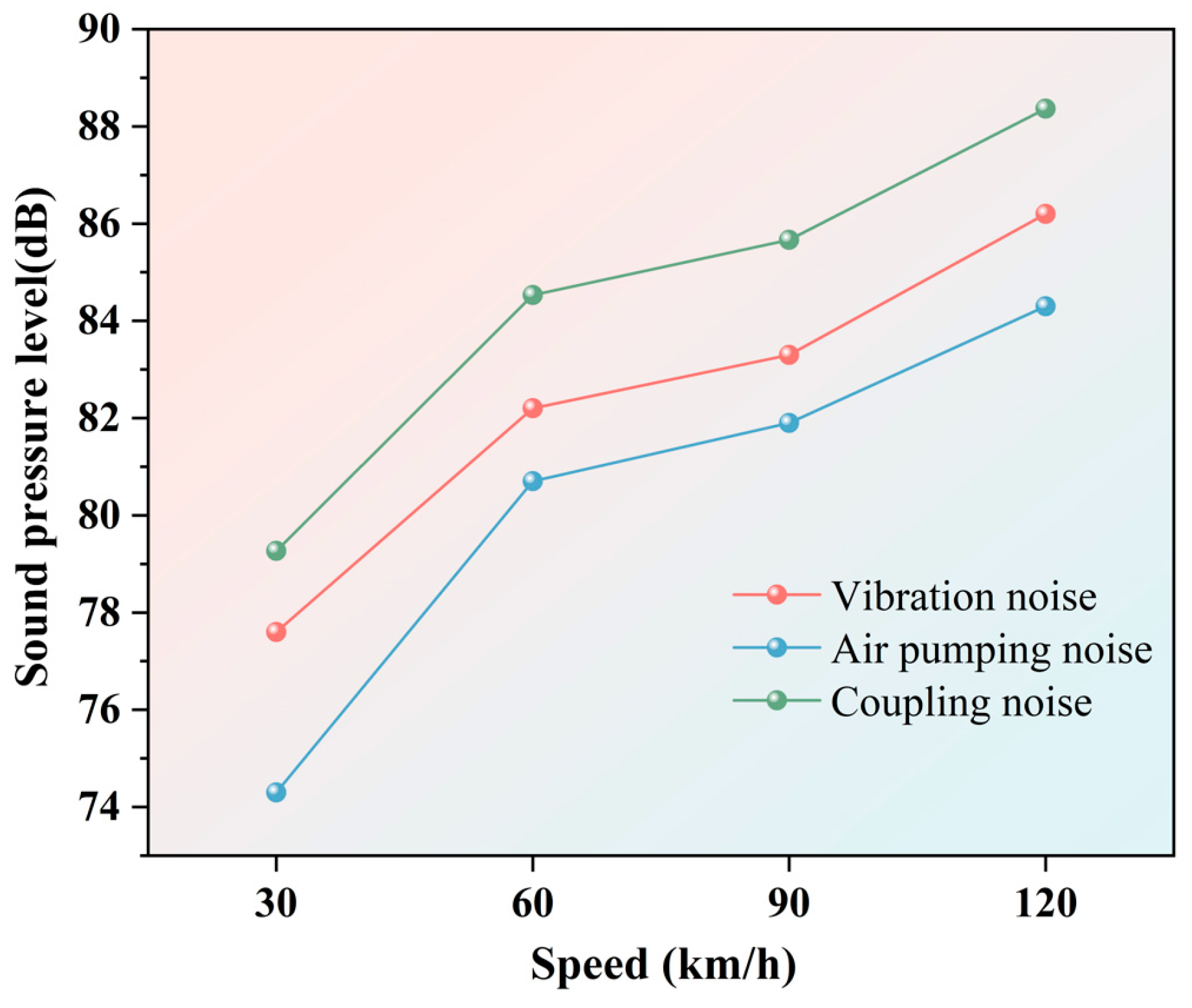

4.5.2. Influence of Vehicle Speed on Tire–Pavement Coupling Noise

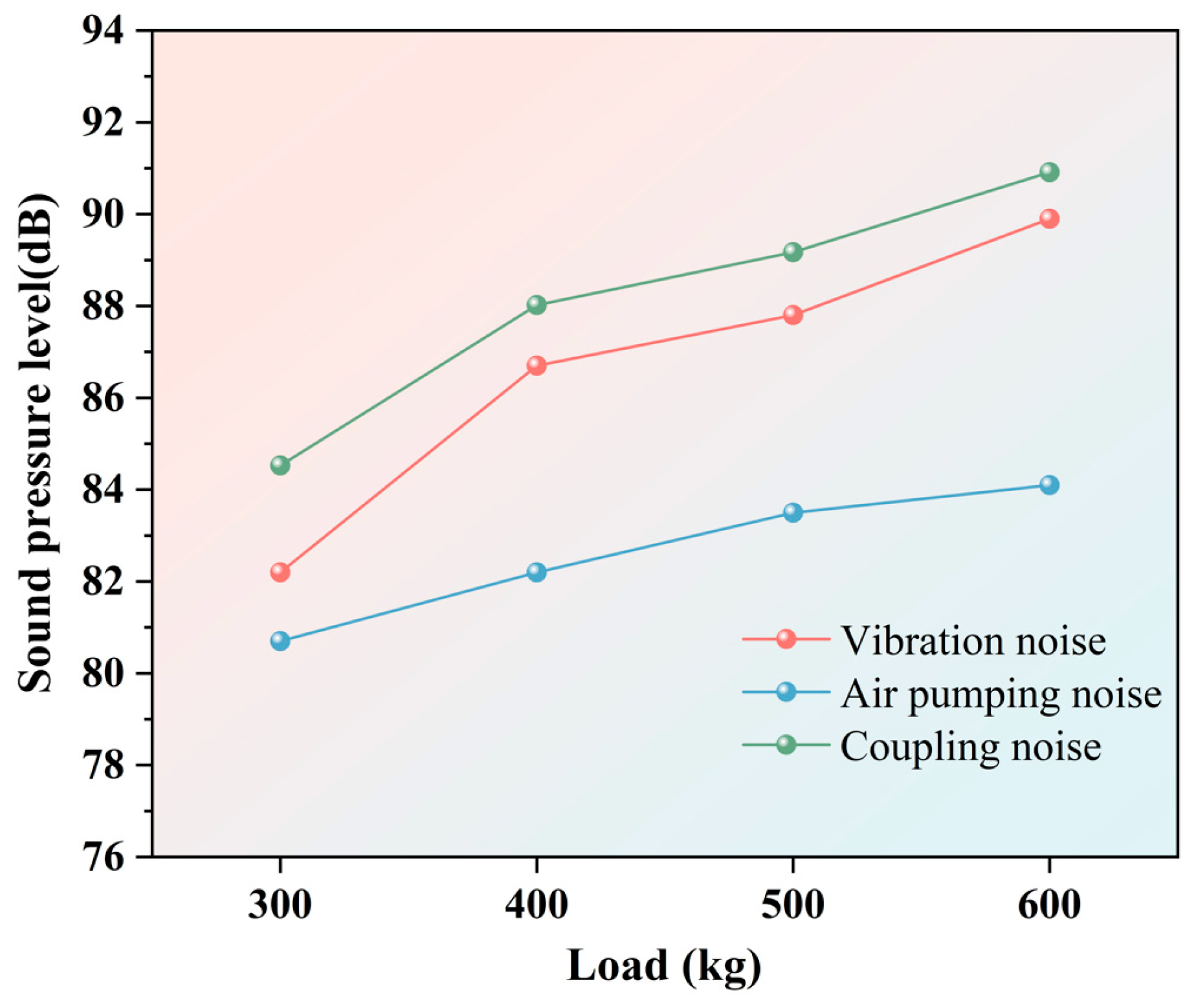

4.5.3. Influence of Vehicle Load on Tire–Pavement Coupling Noise

5. Conclusions

- When compared to conventional dense-graded asphalt concrete (AC), PAC demonstrated enhanced noise reduction efficacy owing to its interconnected void structure, which effectively suppresses air pumping noise. High void ratios were observed to absorb and scatter sound waves, leading to attenuating noise propagation. However, increased vibration noise at the tire–pavement interface was attributed to the rough surface texture of PAC-10. Consequently, design optimization should prioritize balancing these competing mechanisms to maximize noise reduction benefits of PAC while mitigating vibration noise.

- Within the experimentally designed range of 2 cm to 10 cm, vibration noise was significantly reduced as the pavement surface layer thickness was increased, with the noise reduction effect tending to plateau when the thickness exceeded 6 cm. Considering both economic efficiency and noise reduction effects, the pavement thickness design is recommended to be no less than 6 cm.

- The sensitivity analysis of tire tread geometry indicates that the mold release angle (0~30°) and tread depth (5~17 mm) exert a pronounced influence on the air pumping noise and should be prioritized in optimization, whereas the groove width within the 20~60 mm range has only a minor effect. Nevertheless, tread design must balance noise reduction with traction performance. Accordingly, it is recommended to adjust the tread depth and mold release angle while maintaining sufficient friction to ensure both effective noise mitigation and driving safety.

- Tire–pavement coupling noise increases markedly with higher vehicle speeds and axle loads. In particular, within the 30~60 km/h range, tire–pavement coupling noise exhibits the most pronounced growth. This finding underscores the necessity of targeted optimization of tread aerodynamic characteristics and their interaction with porous asphalt pavements in this transitional speed range to achieve more effective noise mitigation.

6. Discussion

- The two-stage approach, which derives excitation from a 2D rolling model and applies the amplitude to a 3D vibration noise model, overlooks factors such as lateral pressure redistribution, lateral tread block interactions, and the anisotropy of pavement textures.

- The simplification of fixing the tire position while applying rotation and amplitude inputs introduces physical approximations. Specifically, this method may fail to account for the transient contact phenomena and the precise phase synchronization between aerodynamic air-pumping pulses and structural oscillations. The absence of real-time dynamic rolling contact may consequently affect the synchronization and spectral distribution of the predicted tire–pavement coupling noise.

- Different asphalt pavements were modeled as linear-elastic slabs, with distinctions confined to surface texture and void ratio. Mixture-specific parameters, such as loss factors and frequency-dependent acoustic absorption or impedance, were not explicitly accounted for. Moreover, the complex interior pore geometry (e.g., tortuosity and connectivity) were omitted from the air-pumping model, which may limit the precision of noise-reduction mechanism analysis for PAC mixtures.

- 4.

- Future studies should transition from the current two-stage approach to a unified, fully dynamic 3D rolling contact framework. This will allow for the precise capture of lateral pressure redistributions and the complex phase synchronization between aerodynamic air-pumping pulses and structural vibrations.

- 5.

- To move beyond macroscopic air void parameters, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and X-ray Computed Tomography (CT) should be utilized to characterize the internal microstructural geometry of PAC. Integrating parameters such as pore connectivity, tortuosity, and surface geometry into the model will significantly refine the analysis of noise-reduction mechanisms.

- 6.

- Subsequent models should incorporate the frequency-dependent acoustic impedance and loss factors specific to various asphalt mixtures. Furthermore, investigating the chemical composition and aging characteristics of the binders may provide deeper insights into the long-term acoustic durability of porous pavements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Begou, P.; Kassomenos, P.; Kelessis, A. Effects of road traffic noise on the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases: The case of Thessaloniki, Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Da, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pang, H. Investigation on the healing effects of microwave heating in eco-friendly pavement using e-waste. Mater. Struct. 2025, 58, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, H.; Zhao, J. Multi-level induced healing of steel bridge deck asphalt pavement: An energy-saving and emission-reducing microwave heating method. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2025, 26, 2506680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Mohammadi, S.; Xin, K.; Yin, L.; You, Z. Laboratory performance and field demonstration of asphalt overlay with recycled rubber and tire fabric fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 136941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Yin, L.; Nedrich, S.; Boateng, K.A.; You, Z. Resurface of rubber modified asphalt mixture with stress absorbing membrane interlayer: From laboratory to field application. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 441, 137452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Xin, K.; Yin, L.; Mohammadi, S.; Cetin, B.; You, Z. Performance of rubber modified asphalt mixture with tire-derived aggregate subgrade. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Li, F.; Cai, M. Road traffic noise exposure assessment based on spatiotemporal data fusion. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 127, 104044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knar, Z.; Sinou, J.-J.; Besset, S.; Clauzon, V. An adapted two-step approach to simulate nonlinear vibrations of patterned tires rolling on a smooth surface. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 135, 477–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont, J.; Goubert, L.; Ronowski, G.; Świeczko-Żurek, B. Ultra Low Noise Poroelastic Road Surfaces. Coatings 2016, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lim, T.C.; Wu, J.; Ding, W.; Pang, J. Multitarget prediction and optimization of pure electric vehicle tire/road airborne noise sound quality based on a knowledge- and data-driven method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 197, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, C.; Wu, G.; Hou, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Jiang, N. Distribution characteristics and prediction method of tire–road AE noise in the monitoring of prestressed hollow slab bridges. Measurement 2024, 227, 114211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Chandy, A.J. Numerical Investigation of the Air Pumping Noise Generation Mechanism in Tire Grooves. J. Vib. Acoust. 2016, 138, 051002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, P.; Chandy, A.J. A Computational Fluid Dynamics Model for Investigating Air-Pumping Mechanisms in Air-Borne Tire Noise. Tire Sci. Technol. 2016, 44, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Alalade, S.; Lee, S.W. Influence of Pavement-Texture Condition on Tire-Pavement Interaction Noise. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 29, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pei, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, D.; Huang, G.; Meng, Y.; Lyu, L.; Zheng, F. Analysis of tire-pavement interaction modeling and rolling energy consumption based on finite element simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra-Rodriguez, M.; Abellán-López, D.; Simón-Portillo, F.J.; Campello-Vicente, H.; Campillo-Davo, N.; Peral-Orts, R. Numerical model for vibro-acoustics analysis of tyre-road noise generation caused by speed bumps. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 216, 109830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, G.; Shi, C.; Jiang, N.; Xu, B. Multiparameter-based separation method for acoustic emission of in-service prestressed hollow slab tire–road noise signals. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 218, 109895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Fan, X. A review on estimation of vehicle tyre-road friction. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 2024, 31, 49–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, Y. Generation mechanisms of tire/road noise. In Automotive Tire Noise and Vibrations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhong, C.; Jiang, Z.; You, D.; Cai, Y. Study on vehicle state and tire-road friction coefficient estimation based on maximum correntropy generalized high-degree cubature Kalman filter. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2024, 47, 2918–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, L.; Li, T.; Burdisso, R.; Sandu, C. An artificial neural network (ANN) approach to model Tire-Pavement interaction noise (TPIN) based on tire noise separation. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 206, 109294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Ohadi, A.; Irannejad-Parizi, M. A comprehensive study on statistical prediction and reduction of tire/road noise. J. Vib. Control 2022, 28, 2487–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardziejczyk, W. The effect of time on acoustic durability of low noise pavements—The case studies in Poland. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 44, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lou, S.; Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, W. Design Method for Air Void and Internal Drainage of Porous Asphalt Pavement at Highway Superelevation Transition Section. HJCE 2022, 11, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Xiao, Z.; Quan, W.; Ma, X.; Dong, Z. Influence of anisotropy on structural dynamic response, from the views of mechanism, analysis method, and implications for pavement design. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2025, 26, 2498618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Ding, W.; Pang, J. Prediction and optimization of pure electric vehicle tire/road structure-borne noise based on knowledge graph and multi-task ResNet. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, H. Recent German experience with open-pored surfacings. In Proceedings of the INTROC 90-International Tire/Road Noise Conference 1990, Gothenburg, Sweden, 8–10 September 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.; Hao, M.; Shen, Y.; Li, H.; Fan, J. Tire noise prediction based on transfer learning and multi-modal fusion. Proc. Insitution Mech. Eng. Part D-J. Automob. Eng. 2024, 239, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paje, S.E.; Bueno, M.; Terán, F.; Miró, R.; Pérez-Jiménez, F.; Martínez, A.H. Acoustic field evaluation of asphalt mixtures with crumb rubber. Appl. Acoust. 2010, 71, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.A.; Wang, K.C.P.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, G.; Yang, E.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Z.; He, A.; et al. Intelligent pixel-level detection of multiple distresses and surface design features on asphalt pavements. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 37, 1654–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fan, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Lu, G.; Lv, S. Study on the influence of tire polishing on surface texture durability and skid resistance deterioration of asphalt pavement. Wear 2024, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, R. Measuring and modeling tire-pavement noise on various concrete pavement textures. Noise Control Eng. J. 2009, 57, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioduszewski, P.; Sorociak, W. Acoustic evaluation of road surfaces using different Close Proximity testing devices. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 204, 109255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Bianco, F.; Carpita, S.; Monticelli, A.; Fredianelli, L.; Licitra, G. Adjusted Controlled Pass-By (CPB) Method for Urban Road Traffic Noise Assessment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Ma, T.; Yan, E. Study on PAC-16 Gradation Composition Design and Road Performance. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2019, 36, 23–28, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Rapino, L.; Ripamonti, F.; Dallasta, S.; Baro, S.; Corradi, R. Synthesis of equivalent sources for tyre/road noise simulation and analysis of the vehicle influence on sound propagation. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 216, 109751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascari, E.; Cerchiai, M.; Fredianelli, L.; Licitra, G. Statistical Pass-By for Unattended Road Traffic Noise Measurement in an Urban Environment. Sensors 2022, 22, 8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Davo, N.; Peral-Orts, R.; Campello-Vicente, H.; Velasco-Sanchez, E. A methodology for the extrapolation of coast-by noise of tyres from sound power level measurements. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 159, 107077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clar-Garcia, D.; Velasco-Sanchez, E.; Sanchez-Lozano, M.; Campello-Vicente, H. An alternative Drum test method to UNECE Regulation 117 for measuring tyre/road noise under laboratory controlled conditions. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 151, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Feng, X.; Fuqiang, Z.; Xiang, D. Simulation of Rolling Noise Based on the Mixed Lagrangian–Eulerian Method. Tire Sci. Technol. 2016, 44, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Zheng, C. Noise Reduction Effect of Porous Asphalt Pavement Based on Acoustic-Structure Coupling Model. Environ. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2021, 8, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswat, A.; Oorath, R.; Patel, C.; Ghosh, A.; Goyal, S.; Thomas, J.; George, J.; Nair, S.; Issac, R. Tyre-Road Interaction Noise Prediction: A Simulation-Based Approach; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neithalath, N.; Marolf, A.; Weiss, J.; Olek, J. Modeling the Influence of Pore Structure on the Acoustic Absorption of Enhanced Porosity Concrete. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2005, 3, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, G.; Li, M.L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Han, D.D.; Li, P.F. Investigation on Medium-Term Performances of Porous Asphalt and Their Impacts on Tire/Pavement Noise. Buildings 2023, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhande, S.; Sakhare, D.; Dange, S.; Jain, M. A Short Review of Road Noise Barriers Focusing on Ecological Approaches. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2021, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, G.; Sakhaeifar, M.S.; Heitzman, M.; West, R.; Waller, B.; Wang, S.; Ding, Y. The effects of pavement surface characteristics on tire/pavement noise. Appl. Acoust. 2014, 76, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biligiri, K.P. Tyre/road noise damping characteristics using nomographs and fundamental vibroacoustical relationships. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 43, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.Z.H.; Hassan, N.A.; Hainin, M.R.; Ismail, C.R.; Jaya, R.P.; Warid, M.N.M.; Yaacob, H.; Mashros, N. Characterisation of microstructural and sound absorption properties of porous asphalt subjected to progressive clogging. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 283, 122654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teti, L.; de León, G.; Del Pizzo, L.G.; Moro, A.; Bianco, F.; Fredianelli, L.; Licitra, G. Modelling the acoustic performance of newly laid low-noise pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247, 118509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG E42-2005; Test Methods of Aggregate for Highway Engineering. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2005.

- JTG E20-2011; Standard Test Methods of Bitumen and Bituminous Mixtures for Highway Engineering. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Ogden, R.W.; Saccomandi, G.; Sgura, I. Fitting hyperelastic models to experimental data. Comput. Mech. 2004, 34, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marckmann, G.; Verron, E. Comparison of Hyperelastic Models for Rubber-Like Materials. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2006, 79, 835–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zheng, F.; Pei, J.; Liu, Q.; Hu, D.; Wen, Y.; Kingan, M. Study on tire-road air pumping noise characteristics based on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and acoustic finite element simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 488, 142181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Du, Y.; Tong, R.; Wei, Y. An improved structural-acoustic coupling model for tire cavity noise. Noise Control Eng. J. 2018, 66, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassil, M.B.L.; Cesbron, J.; Klein, P. Tyre/road noise: A piston approach for CFD modeling of air volume variation in a cylindrical road cavity. J. Sound Vib. 2020, 469, 115140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Xiao, B.; You, Z.; Wu, G.; Li, X.; Ding, Y. Dynamic friction coefficient between tire and compacted asphalt mixtures using tire-pavement dynamic friction analyzer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258, 119492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Han, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Wang, Q. Influence of Surface Texture Characteristics on the Noise in Grooving Concrete Pavement. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhaeifar, M.; Banihashemrad, A.; Liao, G.; Waller, B. Tyre–pavement interaction noise levels related to pavement surface characteristics. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2018, 19, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Park, S.-W.; Lee, S.W. Tire-Pavement Noise Prediction Using Asphalt Pavement Texture. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 3358–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, O. State-of-the-Art Review on Sustainable Design and Construction of Quieter Pavements—Part 2: Factors Affecting Tire-Pavement Noise and Prediction Models. Sustainability 2016, 8, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, T.S.; Karakaş, A.S. Investigation of Asphalt Pavement to Improve Environmental Noise and Water Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, S. Sound absorption characteristics of porous asphalt concrete pavements. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2010, 37, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y. Improvement of acoustic model and structural optimization design of porous asphalt concrete based on meso-structure research. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 265, 120327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Influencing Parameters on Tire–Pavement Interaction Noise: Review, Experiments, and Design Considerations. Designs 2018, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, D. Study on Mathematical Models for Precise Estimation of Tire–Road Friction Coefficient of Distributed Drive Electric Vehicles Based on Sensorless Control of the Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Symmetry 2024, 16, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Huang, Z.; Guo, F. Noise Reduction Characteristics of Macroporous Asphalt Pavement Based on A Weighted Sound Pressure Level Sensor. Materials 2021, 14, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.-W.; Cheng, J.-H. Modelling of Air Pumping Noise and Study of Tread Pattern Pitch. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 24, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapino, L.; Ripamonti, F.; Baro, S.; Corradi, R. Numerical Analysis of the Tread Grooves’ Acoustic Resonances for the Investigation of Tire Noise. J. Vib. Acoust. 2024, 146, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Hu, D.; Liao, F.; Chen, J.; Su, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. A Fast Approach to Optimize Tread Pattern Shape for Tire Noise Reduction. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfosso-Lédée, F.; Do, M.-T. Geometric Descriptors of Road Surface Texture in Relation to Tire-Road Noise. Transp. Res. Rec. 2002, 1806, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, M.J.; Li, Z.; Arenas, J.P. Measurements of Tyre/Road Noise and of Acoustical Properties of Porous Road Surfaces. Int. J. Acoust. Vib. 2005, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Meyer, T.K.; Chen, S.; Boateng, K.A.; Pearce, J.M.; You, Z. Evaluation of lab performance of stamp sand and acrylonitrile styrene acrylate waste composites without asphalt as road surface materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 338, 127569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Wang, J.; You, L.; Ge, D.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; You, Z. Waste cathode-ray-tube glass powder modified asphalt materials: Preparation and characterization. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Item | Unit | Test Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crushing Value | % | 10.7 | |

| Los Angeles Abrasion Loss | % | 6.0 | |

| Relative Apparent Density | 9.5 mm~13.2 mm | g/cm3 | 2.802 |

| 4.75 mm~9.5 mm | 2.823 | ||

| 2.36 mm~4.75 mm | 2.690 | ||

| Flakiness Content | % | 9.6 | |

| Polished Stone Value | BPN | 50.9 | |

| Asphalt Adhesion | Level | 5 |

| Test Item | Unit | Test Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Apparent Density | 1.18 mm~2.36 mm | g/cm3 | 2.718 |

| 0.6 mm~1.18 mm | 2.716 | ||

| 0.3 mm~0.6 mm | 2.714 | ||

| 0.15 mm~0.3 mm | 2.714 | ||

| 0.075 mm~0.15 mm | 2.700 | ||

| Content of Material Passing 0.075 mm | % | 2 | |

| Sand Equivalent Value | % | 79 | |

| Asphalt Blue Value | g/Kg | 3 | |

| Angularity | s | 38 |

| Test Item | Unit | Technical Requirements | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration (25 °C) | 0.1 mm | 40~60 | 57 |

| Penetration Index (PI) | - | Min0 | 0.39 |

| Ductility (5 °C) | cm | Min25 | 28 |

| Softening Point (R&B) | °C | Min70 | 80 |

| Kinematic Viscosity (135 °C) | Pa.s | Max3 | 2.1 |

| Flash Point (Open Cup) | °C | Min230 | 308 |

| Loss on Heating (48 h) | °C | Max2.5 | 1.5 |

| Solubility | % | Min99 | 99.69 |

| Resilience (25 °C) | % | Min85 | 94 |

| Residual after TFOF (or RTFOT) | |||

| Quality Change | % | Max ± 1.0 | −0.085 |

| Residual Penetration Ratio | % | Min65 | 75 |

| Residual Ductility (5 °C) | cm | Min15 | 16.1 |

| Gradation Type | Percent of Aggregate Passing Through Each Sieve Size (%) | Asphalt-Aggregate Ratio | Air Voids (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 mm | 13.2 mm | 9.5 mm | 4.75 mm | 2.36 mm | 1.18 mm | 0.6 mm | 0.3 mm | 0.15 mm | 0.075 mm | |||

| PAC-10 | 100 | 100 | 94.4 | 51.3 | 16.6 | 12.1 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 19.4 |

| SMA-10 | 100 | 100 | 95.4 | 42.0 | 26.3 | 20.0 | 17.0 | 14.0 | 12.3 | 10.5 | 6.2 | 4.6 |

| AC-10 | 100 | 100 | 98 | 64.5 | 46 | 27.5 | 21 | 14.0 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Parameter Name | Numerical Value |

|---|---|

| Scan Area (mm) | 104.00 × 72.00 |

| Product Dimensions (mm) L × W × H | 152.4 × 228.6 × 205 |

| Weight (kg) | 4.2 |

| Vertical Resolution (mm) | 0.003 |

| Measurement Range (mm) | 30 |

| Maximum Length Resolution (mm) | 0.00635 |

| Maximum Width Resolution (mm) | 0.0247 |

| Triangulation Angle at center of range (°) | 22 |

| Dot size at center of range (μm) | 25 |

| Dot size at Max and Min range (μm) | 60 |

| Max laser sampling speed (Khz) | 5 |

| Parameters | C10 | C20 | C30 | D1 | D2 | D3 | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical | 0.7 × 106 | −0.27 × 106 | 0.09 × 106 | 7.25 × 10−8 | 0 | 0 | 1100 |

| Outer Diameter (m) | Inner Diameter (m) | Width (m) | Thickness (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tire tread | 0.22 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| Sidewall | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.002 | 0.05 |

| Structure Type | Density (kg/m3) | Elasticity Modulus (pa) | Poisson Ratio | Damping Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road surface | 2400 | 1.6 × 109 | 0.32 | 0.06 |

| Material | Elasticity Modulus (KPa) | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|

| Air | 142 | 1.2 |

| Item | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Calibration Source | 94 dB @1 KHz |

| Measurement Range | 30~130 dBA, 35~130 dBC |

| Accuracy | ±1.5 dB (Reference Sound Pressure Standard, 94 dB @1 KHz) |

| Frequency Response | 31.5 Hz~8.5 KHz |

| Resolution | 0.1 dB |

| Measurement Range Gear | 30~80, 50~100, 60~110, 30~130 |

| Dynamic Range | 50 dB/100 dB |

| Frequency Weighting | A and C |

| Digital Display | 4 digits |

| Sampling Rate | 20 times/second |

| AC Signal Output | 4 Vrms/full scale, output impedance about 600 ohms |

| PWM Output | Duty Cycle = |

| Perpetual Calendar Accuracy | ±30 s/day |

| Battery Capacity | 4700 entries |

| Microphone | 1/2 inch condenser microphone |

| Operating Voltage | 6 V |

| Dimensions | 67 × 30 × 183 mm |

| Battery Life | 20 h (continuous use) |

| Pavement | Sound Pressure (Pa) | Sound Pressure Level (dB) |

|---|---|---|

| PAC-10 | 0.277 | 82.3 |

| SMA-10 | 0.251 | 81.4 |

| AC-10 | 0.250 | 81.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, M.; Lv, G.; Li, A.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, J. Finite Element Analysis of Tire–Pavement Interaction Effects on Noise Reduction in Porous Asphalt Pavements. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010523

Yu M, Lv G, Li A, Yang J, Zhang Z, Jin D, Zhang R, Li J. Finite Element Analysis of Tire–Pavement Interaction Effects on Noise Reduction in Porous Asphalt Pavements. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010523

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Miao, Geyun Lv, Anqi Li, Jing Yang, Zhexi Zhang, Dongzhao Jin, Rong Zhang, and Jiqing Li. 2026. "Finite Element Analysis of Tire–Pavement Interaction Effects on Noise Reduction in Porous Asphalt Pavements" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010523

APA StyleYu, M., Lv, G., Li, A., Yang, J., Zhang, Z., Jin, D., Zhang, R., & Li, J. (2026). Finite Element Analysis of Tire–Pavement Interaction Effects on Noise Reduction in Porous Asphalt Pavements. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010523