Study on Performance Optimization and Feasibility of No.9 Turnout with 1520 mm Gauge in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dynamic Response Analysis of Vehicle–Turnout System

2.1. Optimization of Plane Alignment

2.2. Subsection

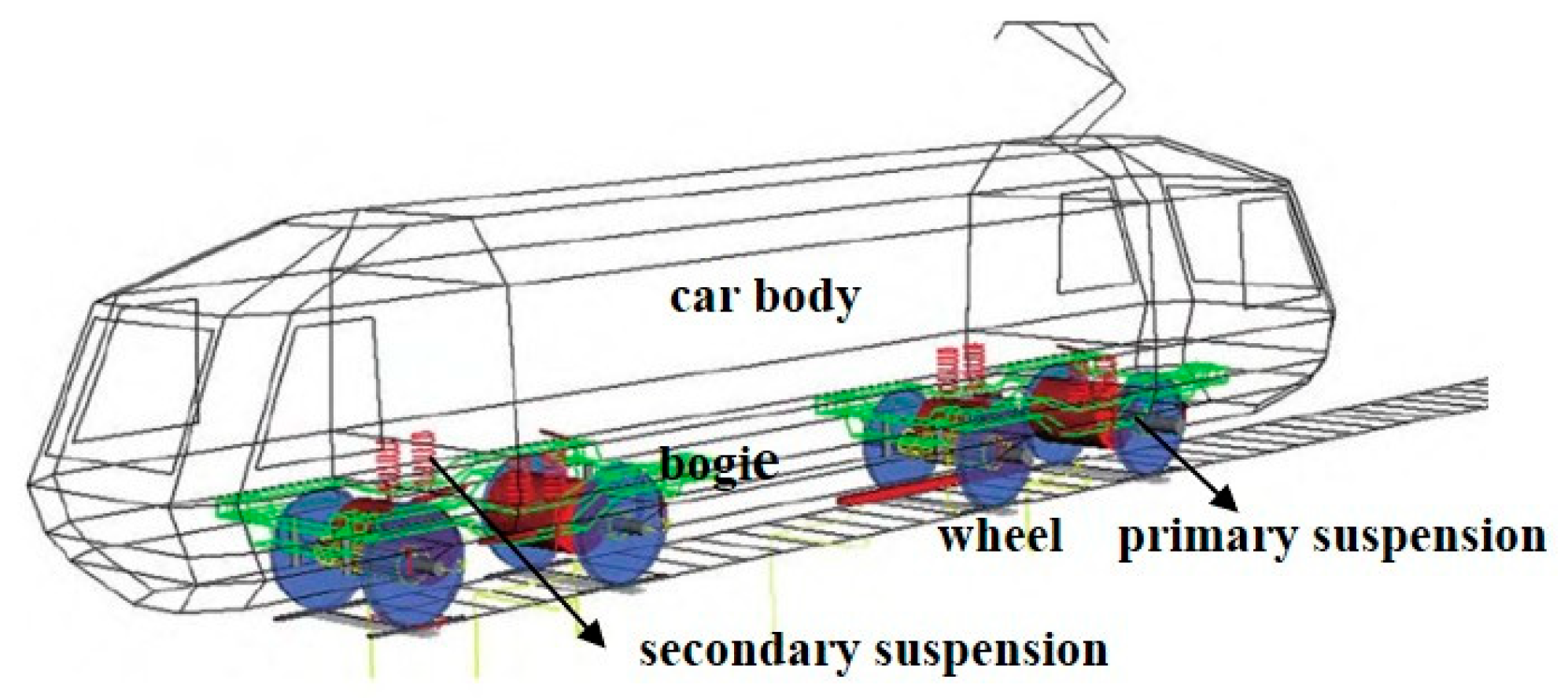

2.2.1. Vehicle Model

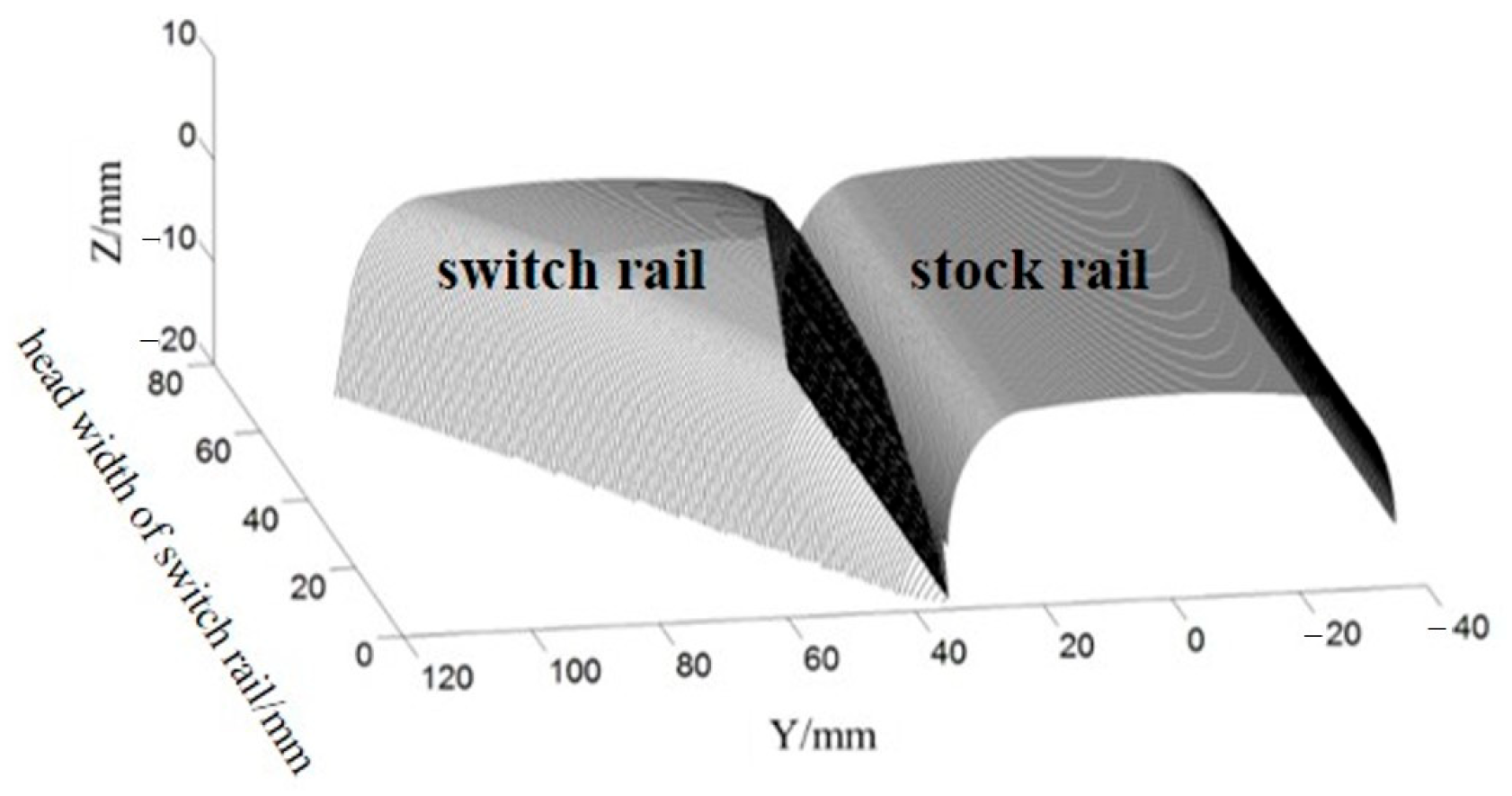

2.2.2. Turnout Model

2.2.3. Wheel–Rail Contact Model

2.3. Dynamic Calculation Results

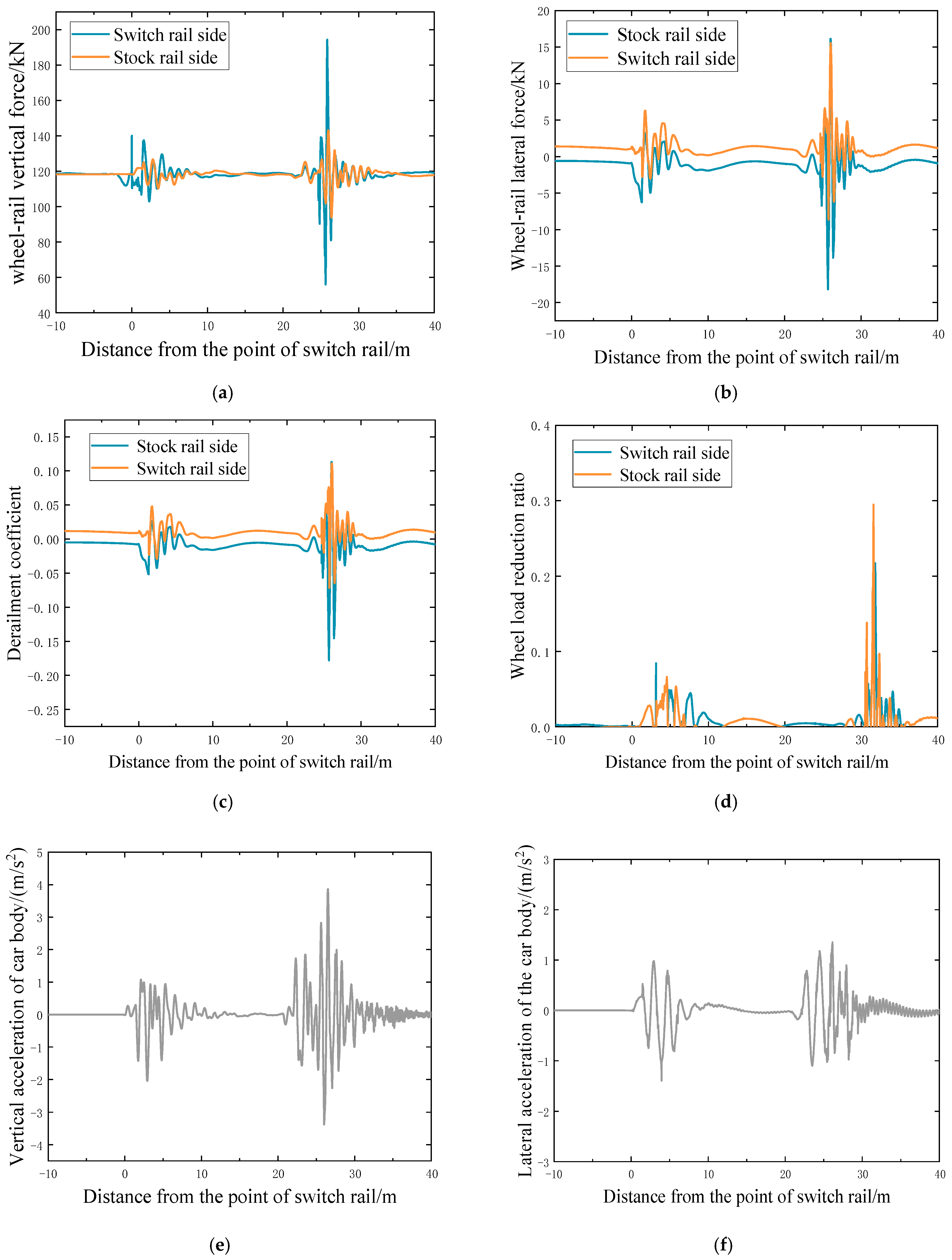

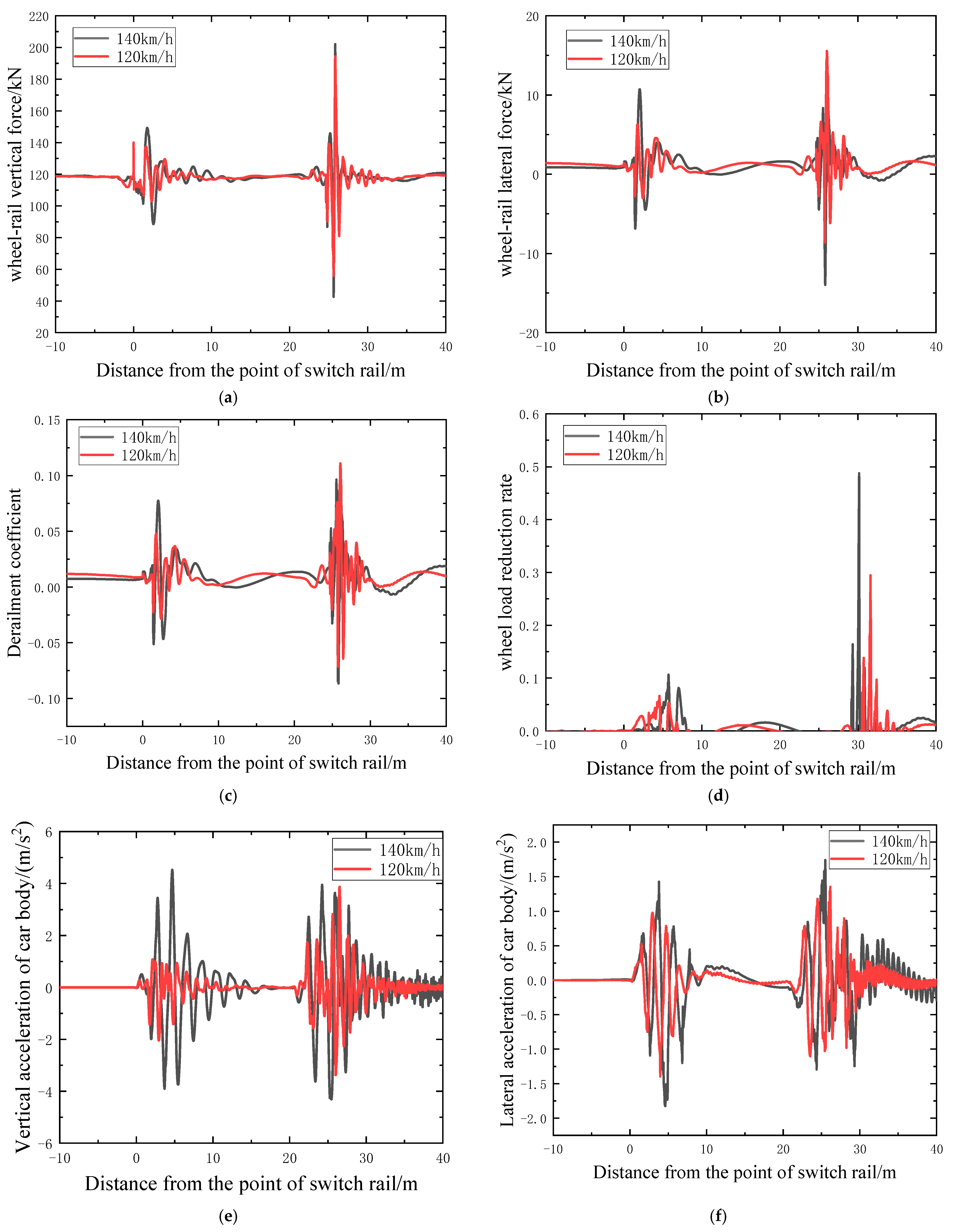

2.3.1. Straight Passage Through the Turnout

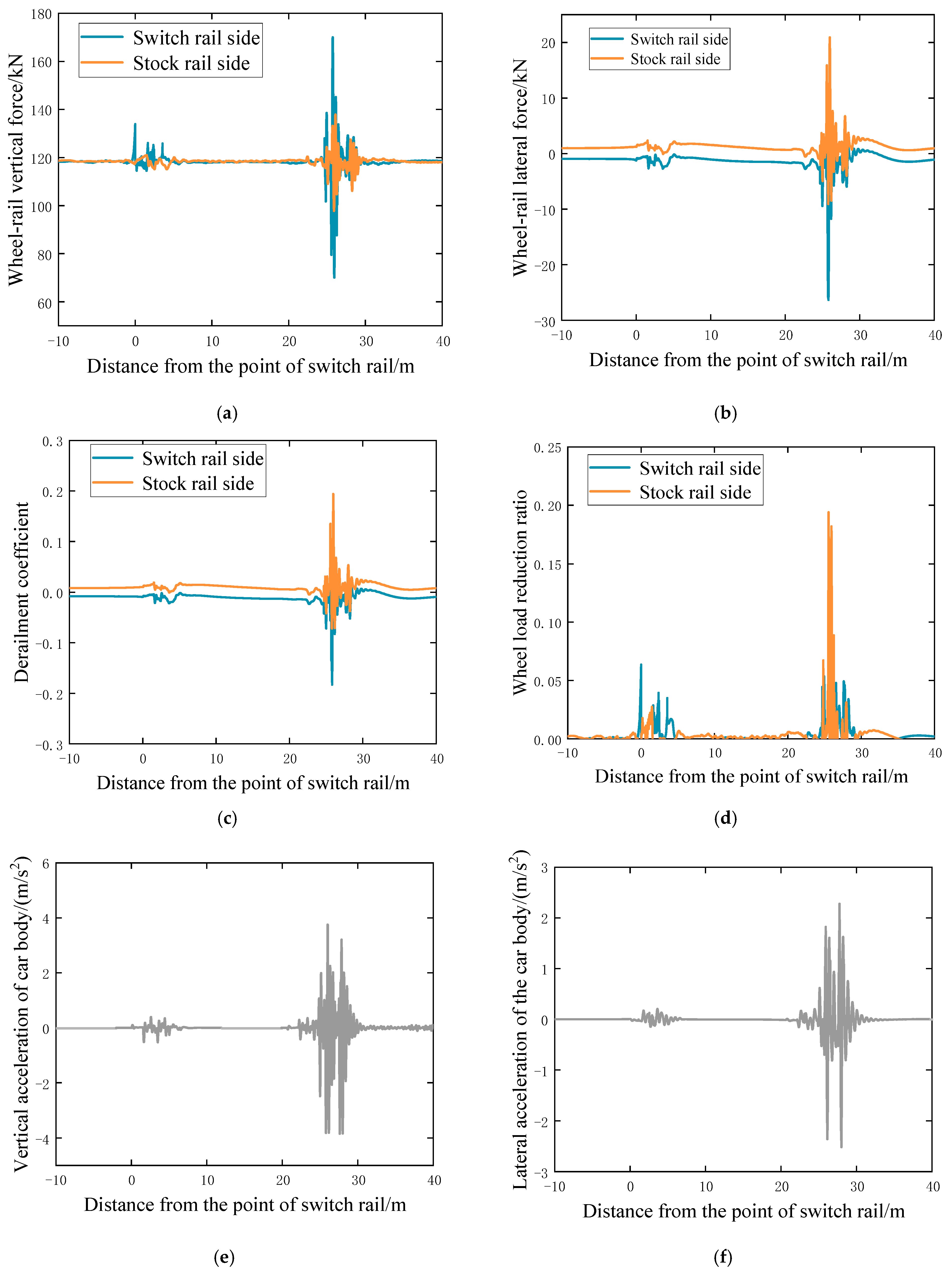

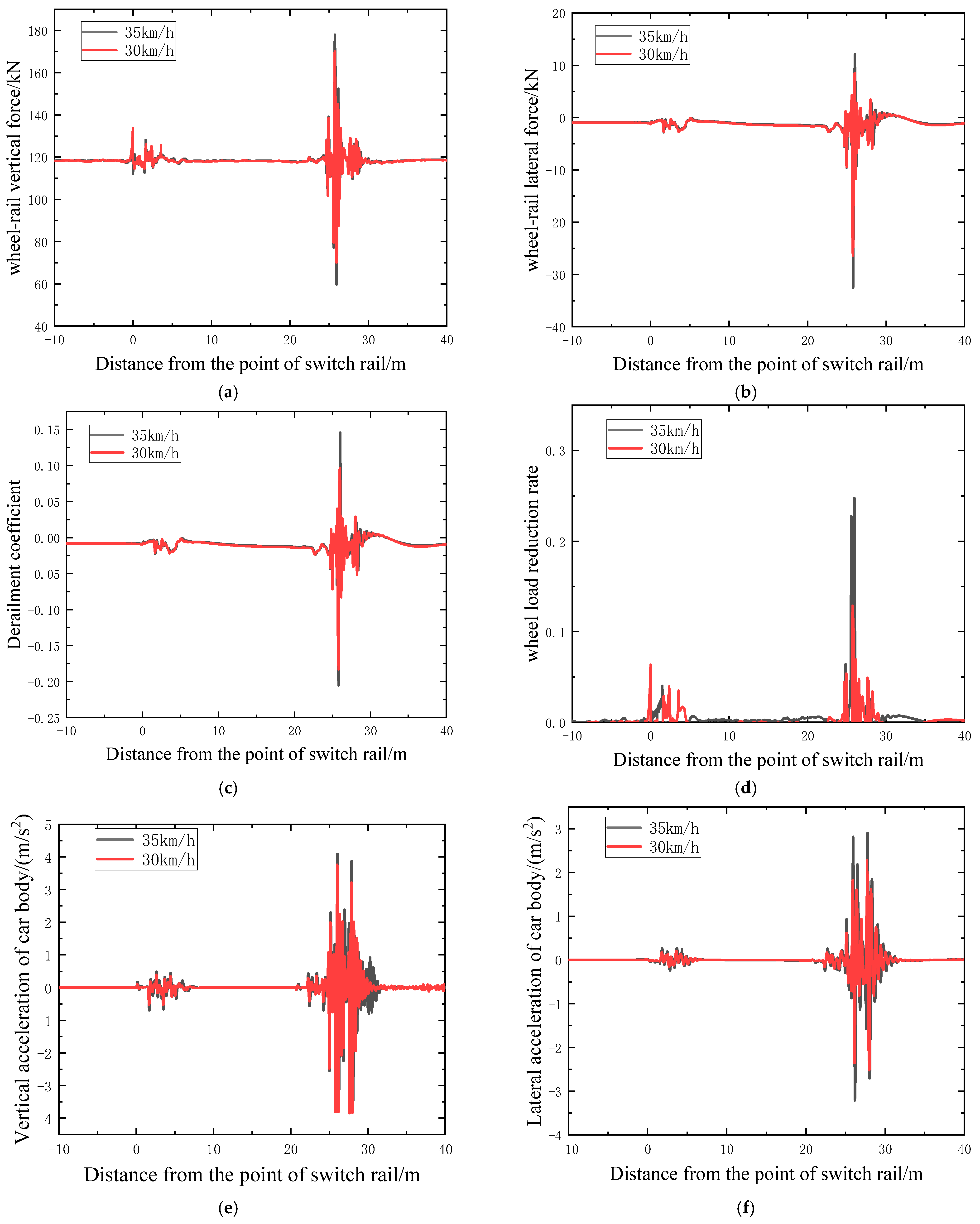

2.3.2. Lateral Passage Through the Turnout

2.3.3. The Impact of Overspeed

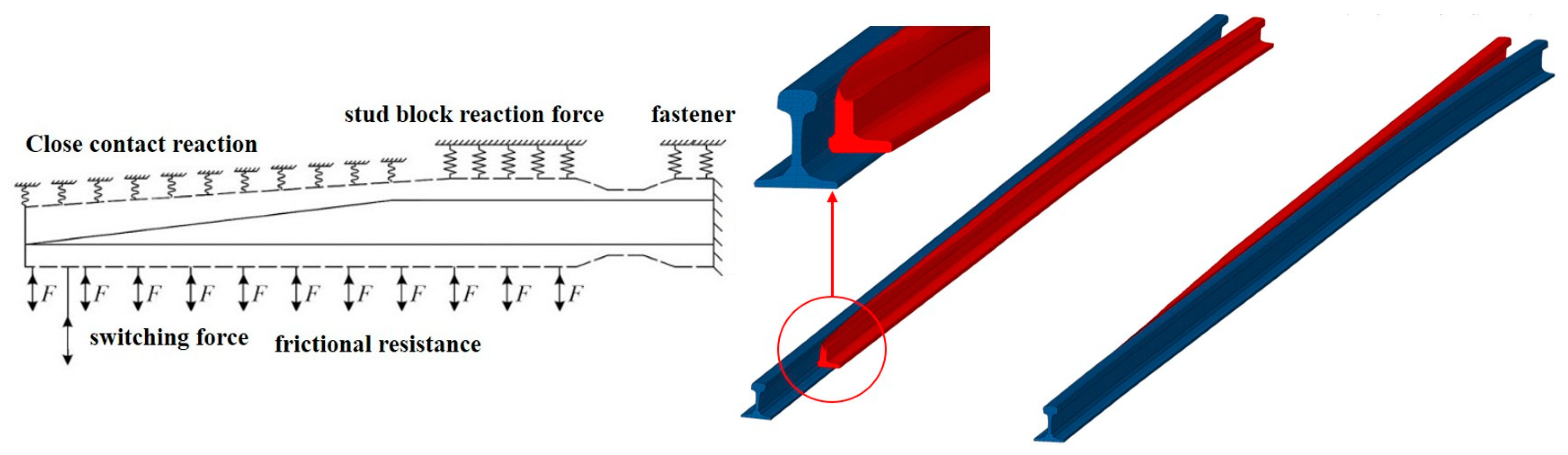

3. Switch Rail Conversion Analysis

3.1. Conversion Design

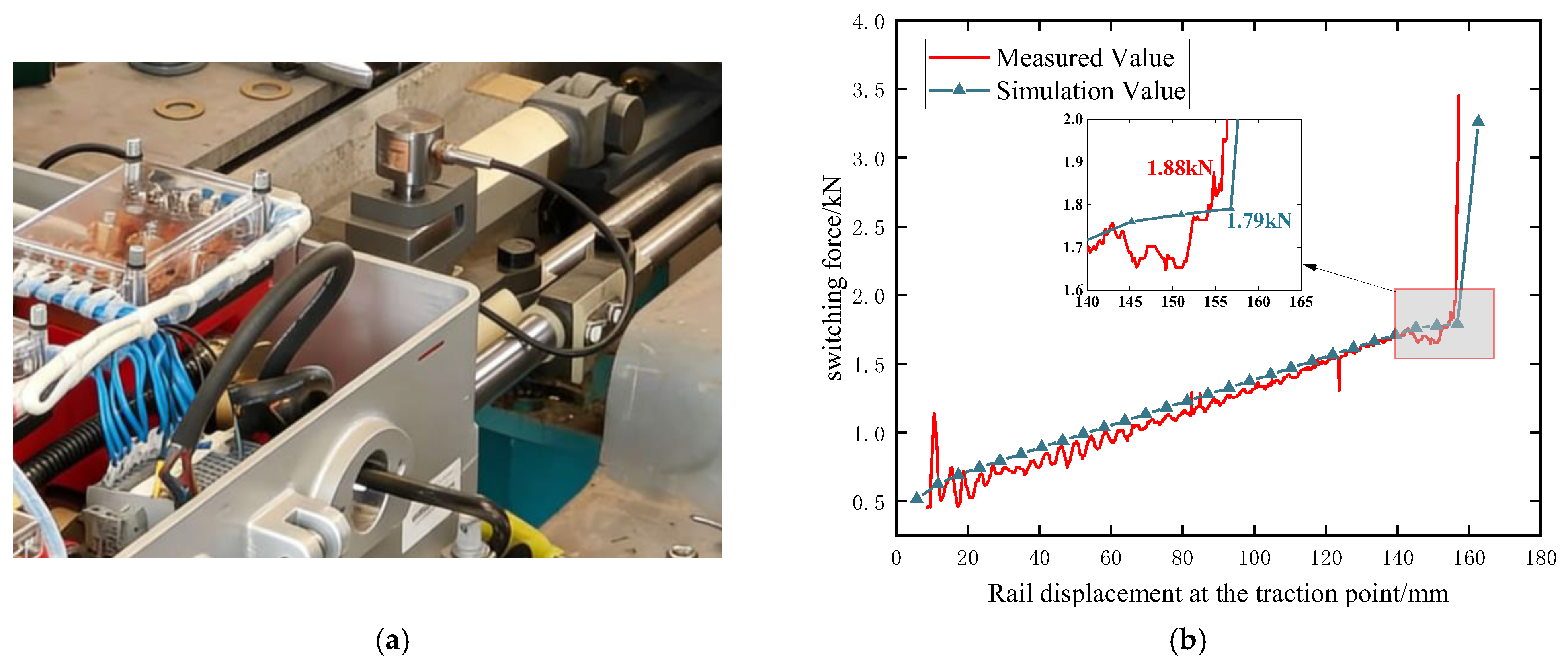

3.2. Model Establishment and Verification

3.3. Conversion Calculation Results

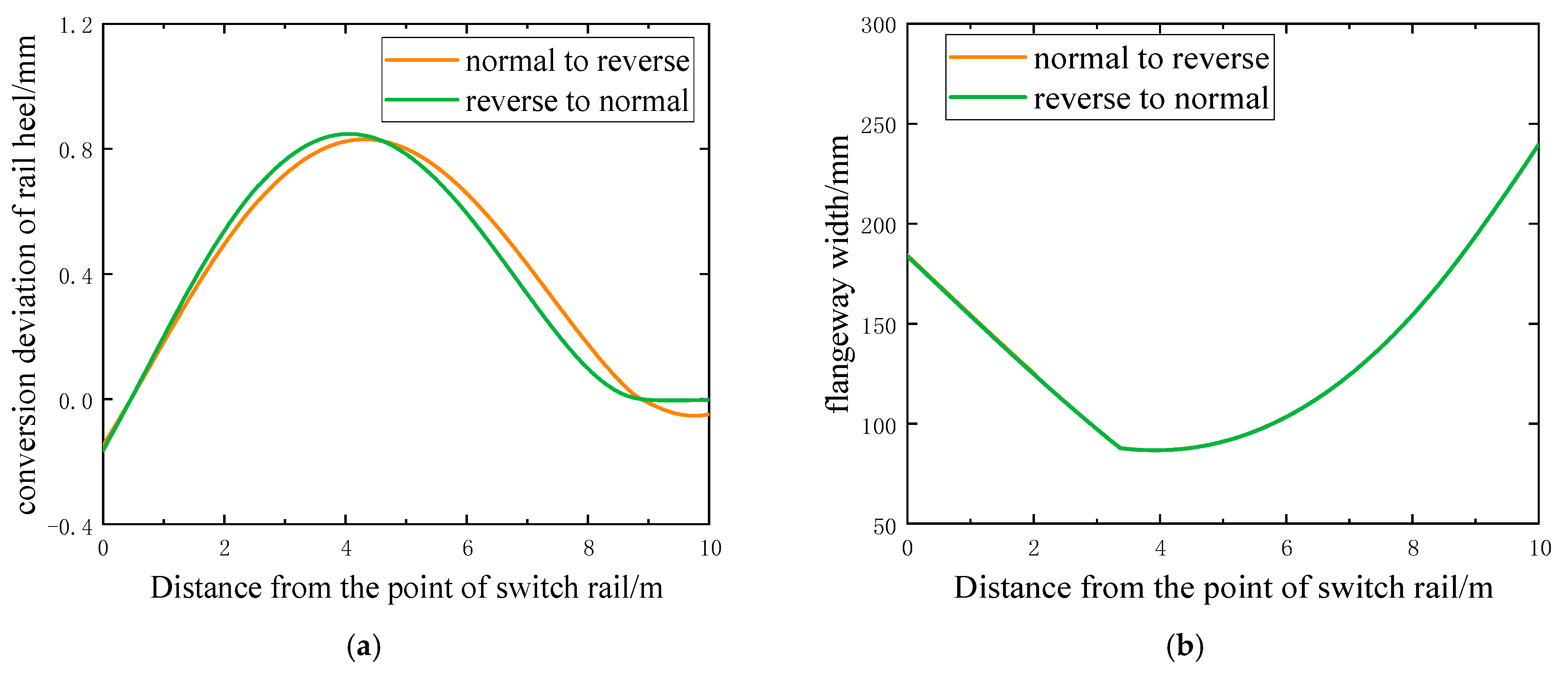

3.3.1. Conversion Deviation of Rail Heel

3.3.2. Minimum Flangeway Width

4. Calculation of CWR Turnout

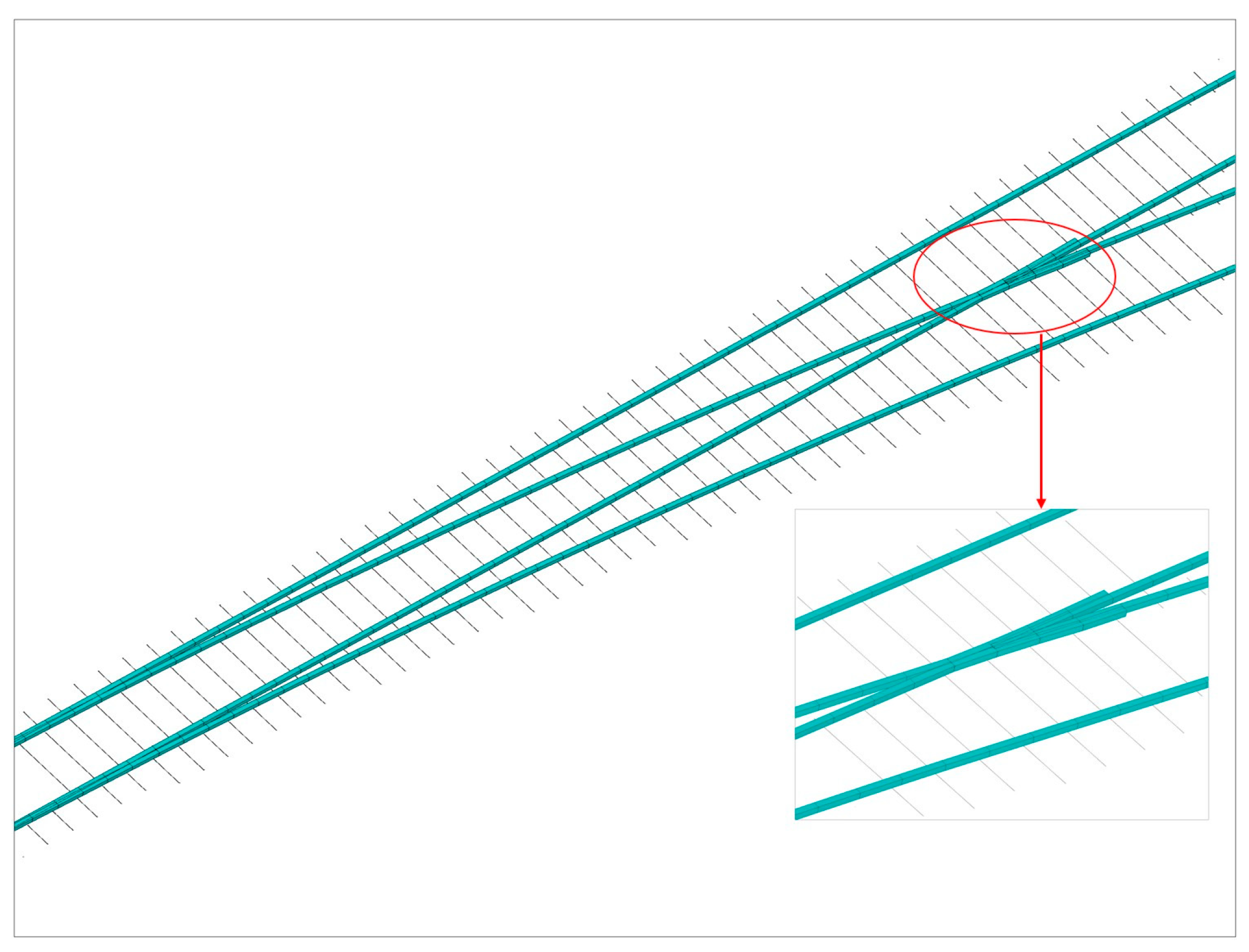

4.1. Model Establishment

4.2. Longitudinal Thermal Forces and Displacements in CWR Turnouts

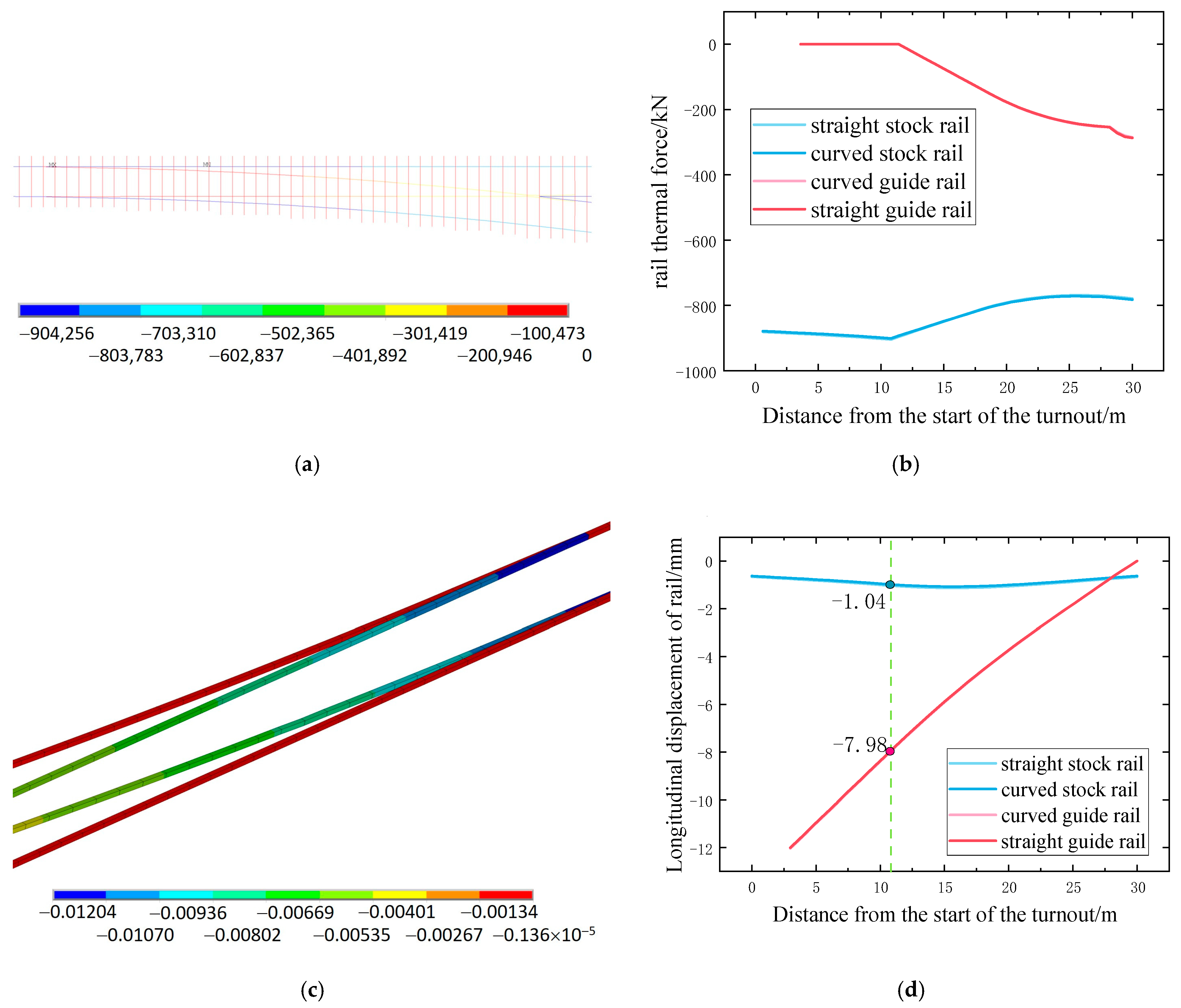

4.2.1. Temperature Rise Condition

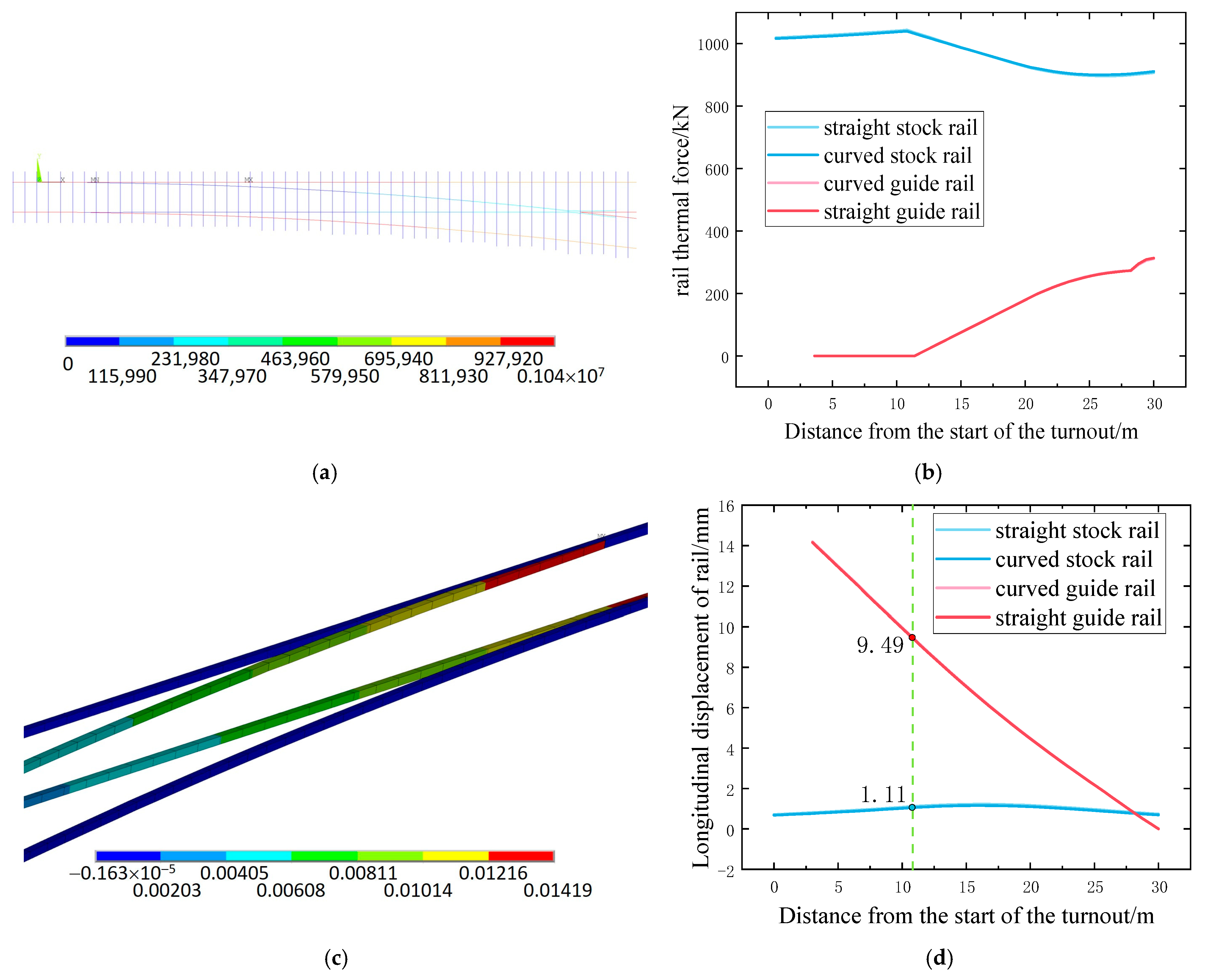

4.2.2. Temperature Drop Condition

4.3. Verification Calculation of CWR Turnout

4.3.1. Verification Calculation of Rail Strength

4.3.2. Verification Calculation of Track Stability for CWR Turnout

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CWR | Continuous welded rail |

References

- Pålsson, B.A.; Nielsen, J.C.O. Track gauge optimisation of railway switches using a genetic algorithm. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2012, 50, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droździel, P.; Bukova, B.; Brumerčíková, E. Prospects of international freight transport in the East-West direction. Transp. Probl. 2015, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doński Lesiuk, J. The Importance of the 1520 mm Gauge Rail Transport System for Trans Eurasian International Trade in the Exchange of Goods. Comp. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2022, 25, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudenko, J.; Andins, M.; Pocs, R. Eu Transport Policy on the 1520mm Rail Area. In European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; Future Academy: Verona, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, K.; Li, T.; Shen, B.; Zheng, Z.; Yan, Z.; Ma, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, P.; Qian, Y. Dynamic wheel-rail interaction of a train crossing a turnout under traction/braking behaviour and research on rail wear of the turnout. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2025, 239, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, P.; Xu, J.; Chen, R. Simulation of vehicle-turnout coupled dynamics considering the flexibility of wheelsets and turnouts. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2023, 61, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, R.; Wang, P.; Wei, X. Investigation on the motion conditions and dynamic interaction of vehicle and turnout due to differential wheelset misalignment. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2022, 60, 2587–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Boogaard, A.; Núñez, A.; Li, Z.; Dollevoet, R. An integrated approach for characterizing the dynamic behavior of the wheel–rail interaction at crossings. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 2332–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Research and Development of No.8.5 Broad Gauge Simple Turnout with 60 kg/m Rails and Gauge of 1676 mm. Railw. Constr. Technol. 2023, 49–51+63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Y.; Pang, L.; Yao, L. The track design summary of high-speed railway from Moscow to Kazan. Shanxi Archit. 2020, 46, 126–127+184. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.G.; Ge, J.; Si, D.L.; Wang, M. Study on Guard Check Gauge of Fixed Frog and Design on Widening Nose Rail. China Railw. Sci. 2014, 35, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Grigonis, V.; Kaušylas, M.; Palevičius, V. Advancing Sustainable Interoperability Between Standard and Broad-Gauge Railway Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, J.M.; Liu, D.Y.; Pang, L.; Yao, L. Key Technologies of 400 km/h Broad Gauge Turnout Design for High Speed Railway. High Speed Railw. Technol. 2019, 10, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z. Design of One-ninth Fixed Obtuse Crossing between Wide Gauge and Standard Gauge. Railw. Constr. Technol. 2012, 78–80+99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, Z.H.; Mo, H.Y. Research on the Influence of Track Gauge on Stress Characteristics of Track Structure. Railw. Eng. 2020, 60, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.Q. A Comparative Study of Main Technical Standards of Railway Line Between China and Russia. Railw. Tech. Stand. 2024, 6, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, D.Q. Comparative Analysis on Railway Design Standards between China and Russia. Railw. Stand. Des. 2012, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Markine, V.; Shevtsov, I. Analysis of the effect of repair welding/grinding on the performance of railway crossings using field measurements and finite element modeling. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2018, 232, 798–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xu, T.; Tang, T.; Yuan, T.; Wang, H. A Bayesian network model for prediction of weather-related failures in railway turnout systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 69, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Markine, V.; Shevtsov, I. Improvement of vehicle–turnout interaction by optimising the shape of crossing nose. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2014, 52, 1517–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, N.; Sichani, M.S.; Enblom, R.; Berg, M.; Li, Z.; Dollevoet, R. Influence of wheel–rail contact modelling on vehicle dynamic simulation. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2015, 53, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamarat, M.Z.; Kaewunruen, S.; Papaelias, M. Contact Conditions over Turnout Crossing Noses. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 062027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrypnyk, R.; Nielsen, J.C.; Ekh, M.; Pålsson, B.A. Metamodelling of wheel–rail normal contact in railway crossings with elasto-plastic material behaviour. Eng. Comput. 2019, 35, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalo, A.; Aravinthan, T.; Karunasena, W.; Stevens, N. Analysis of a typical railway turnout sleeper system using grillage beam analogy. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2012, 48, 1376–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamarat, M.; Kaewunruen, S.; Papaelias, M.; Silvast, M. New insights from multibody dynamic analyses of a turnout system under impact loads. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Núñez, A.; Li, Z.; Dollevoet, R. Evaluating degradation at railway crossings using axle box acceleration measurements. Sensors 2017, 17, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, E.; Nielsen, J.C. Dynamic interaction between train and railway turnout: Full-scale field test and validation of simulation models. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2008, 46, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossoni, I.; Iwnicki, S.; Bezin, Y.; Gong, C. Dynamics of a vehicle–track coupling system at a rail joint. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2015, 229, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, S.; Kaewunruen, S.; An, M.; Sussman, J.M. Bayesian Network-based probability analysis of train derailments caused by various extreme weather patterns on railway turnouts. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, S.; Kaewunruen, S.; An, M.; Osman, M.H. Natural hazard risks on railway turnout systems. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, S.; Kaewunruen, S.; An, M. Identification of appropriate risk analysis techniques for railway turnout systems. J. Risk Res. 2016, 21, 974–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, S.; Kaewunruen, S.; An, M. Rail accident analysis using large-scale investigations of train derailments on switches and crossings: Comparing the performances of a novel stochastic mathematical prediction and various assumptions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 103, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeliukstis, R.; Kaewunruen, S. A Novel Separation Technique of Flexural Loading-Induced Acoustic Emission Sources in Railway Prestressed Concrete Sleepers. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 51426–51440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S. Monitoring in-service performance of fibre-reinforced foamed urethane sleepers/bearers in railway urban turnout systems. Struct. Monit. Maint. 2014, 1, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; You, R.; Ishida, M. Composites for timber-replacement bearers in railway switches and crossings. Infrastructures 2017, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Sussman, J.M.; Matsumoto, A. Grand challenges in transportation and transit systems. Front. Built Environ. 2016, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Remennikov, A.M.; Murray, M.H. Introducing a new limit states design concept to railway concrete sleepers: An Australian experience. Front. Mat. 2014, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sresakoolchai, J.; Hamarat, M.; Kaewunruen, S. Automated machine learning recognition to diagnose flood resilience of railway switches and crossings. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengsri, P.; Ngamkhanong, C.; de Melo, A.L.O.; Kaewunruen, S. Experimental and numerical investigations into dynamic modal parameters of fiber-reinforced foamed urethane composite beams in railway switches and crossings. Vibration 2020, 3, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 5599-2019; Specification for Dynamic Performance Assessment and Testing Verification of Rolling Stock. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Zhai, W.M. Vehicle-Track Coupling Dynamics; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UIC OR 518-2009; Testing and Approval of Railway Vehicles from the Point of View of Their Dynamic Behaviour-Safety—Track Fatigue—Running Behaviour. UIC: Paris, France, 2009.

- TB 10015-2012; Code for Design of Railway Continuous Welded Rail. China Railway Corporation: Beijing, China, 2012.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| axle load | 23 t |

| load | 70 t |

| self-weight | ≤25.8 t |

| weight per linear meter | 3.56 t/m |

| vehicle wheelbase | 14,640 mm |

| vehicle fixed-distance | 8650 mm |

| bogie fixed wheelbase | 1850 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, P.; Gao, Y.; Yi, Q.; Liu, C.; Ren, H. Study on Performance Optimization and Feasibility of No.9 Turnout with 1520 mm Gauge in China. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010513

Li Z, Wang S, Wang P, Gao Y, Yi Q, Liu C, Ren H. Study on Performance Optimization and Feasibility of No.9 Turnout with 1520 mm Gauge in China. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010513

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhiheng, Shuguo Wang, Pu Wang, Yuan Gao, Qiang Yi, Cuihua Liu, and Hao Ren. 2026. "Study on Performance Optimization and Feasibility of No.9 Turnout with 1520 mm Gauge in China" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010513

APA StyleLi, Z., Wang, S., Wang, P., Gao, Y., Yi, Q., Liu, C., & Ren, H. (2026). Study on Performance Optimization and Feasibility of No.9 Turnout with 1520 mm Gauge in China. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010513