Triaxial Compression of Anisotropic Voronoi-Based Cellular Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Voronoi Configurations

2.2. SLA 3D Printing Fabrication

2.3. Mechanical Testing

3. Results

3.1. Compressive Behaviour

3.2. Mechanical Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, C.; Han, Y.; Lu, J. Design and Optimization of Lattice Structures: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Cai, G.; Jin, H. Additive Manufacturing and Influencing Factors of Lattice Structures: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.Y.; Li, J.R.; Xu, Z.J.; Wang, Q.H. Parametric design of Voronoi-based lattice porous structures. Mater. Des. 2020, 191, 108607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shen, L.; Zhao, J.; Liang, H.; Xie, D.; Tian, Z.; Wang, C. Design and Compressive Behavior of Controllable Irregular Porous Scaffolds: Based on Voronoi-Tessellation and for Additive Manufacturing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Yao, D.; Wei, Y. Mechanical and permeability properties of porous scaffolds developed by a Voronoi tessellation for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 9699–9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathiadis, A.; Symeonidou, I.; Tsongas, K.; Tzimtzimis, E.K.; Tzetzis, D. 3D Printed Voronoi Structures Inspired by Paracentrotus lividus Shells. Designs 2023, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Shen, J.; Zhou, S.; Huang, X.; Xie, Y.M. Design of lattice structures with controlled anisotropy. Mater. Des. 2016, 93, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, J. Porous Scaffold Design for Additive Manufacturing in Orthopedics: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 609. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00609 (accessed on 17 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Suzuki, H.; Sawada, K.; Okada, S.; Nishimura, A.; Todoh, M. Novel strut-based stochastic lattice biomimetically designed based on the structural and mechanical characteristics of cancellous bone. Mater. Des. 2025, 251, 113657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuninetti, V.; Narayan, S.; Ríos, I.; Menacer, B.; Valle, R.; Al-lehaibi, M.; Kaisan, M.U.; Samuel, J.; Oñate, A.; Pincheira, G.; et al. Biomimetic Lattice Structures Design and Manufacturing for High Stress, Deformation, and Energy Absorption Performance. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakey-Milner, B.; Gradl, P.; Snedden, G.; Brooks, M.; Pitot, J.; Lopez, E.; Leary, M.; Berto, F.; Plessis, A.D. Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadimu, S.O.; Kourousis, K.I. Compressive Behaviour of Additively Manufactured Lattice Structures: A Review. Aerospace 2021, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Du, B.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Deformation behaviors and energy absorption of auxetic lattice cylindrical structures under axial crushing load. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, Z.; Hernandez-Nava, E.; Tyas, A.; Warren, J.A.; Fay, S.D.; Goodall, R.; Todd, I.; Askes, H. Energy absorption in lattice structures in dynamics: Experiments. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2016, 89, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, Q.M. Advanced lattice material with high energy absorption based on topology optimization. Mech. Mater. 2020, 148, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengsri, P.; Fu, H.; Kaewunruen, S. Mechanical Properties and Energy-Absorption Capability of a 3D-Printed TPMS Sandwich Lattice Model for Meta-Functional Composite Bridge Bearing Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathiadis, A.; Symeonidou, I.; Tsongas, K.; Tzimtzimis, E.K.; Tzetzis, D. Parametric Design and Mechanical Characterization of 3D-Printed PLA Composite Biomimetic Voronoi Lattices Inspired by the Stereom of Sea Urchins. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, S.; Malik, A.; Singh, N.; Raina, A.; Naveed, N.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Haq, M.I.U. Additive manufacturing technologies: Industrial and medical applications. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, J.; Dowling, K.I.; DiCecco, L.A.; McLean, G.D.; Yu, B.; Grandfield, K. Selective Voronoi tessellation as a method to design anisotropic and biomimetic implants. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 116, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, U.; Ghouse, S.; Nai, K.; Jeffers, J.R. Controlling and testing anisotropy in additively manufactured stochastic structures. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 39, 101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, L.; Goretti, G.; Magrini, G.; Vena, P. Tuning the trabecular orientation of Voronoi-based scaffold to optimize the micro-environment for bone healing. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2025, 24, 1057–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, S.; Cao, W.; Lu, W.; Lu, P. Design of 3D anisotropic Voronoi porous structure driven by stress field. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 420, 116717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.; Toribio, J.; Kreši’c, I.K.; Kaljun, J.; Rašovi’c, N.R. Controlling the Mechanical Response of Stochastic Lattice Structures Utilizing a Design Model Based on Predefined Topologic and Geometric Routines. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttridge, C.; Shannon, A.; O’Sullivan, A.; O’Sullivan, K.J.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Effects of post-curing duration on the mechanical properties of complex 3D printed geometrical parts. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 156, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1621; Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Rigid Cellular Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- Herath, B.; Suresh, S.; Downing, D.; Cometta, S.; Tino, R.; Castro, N.J.; Leary, M.; Schmutz, B.; Wille, M.L.; Hutmacher, D.W. Mechanical and geometrical study of 3D printed Voronoi scaffold design for large bone defects. Mater. Des. 2021, 212, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J. Modelling the mechanical behavior of cellular materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1989, 110, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. The properties of foams and lattices. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2006, 364, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Structure | Initial Z Dim. (mm) | Computed Porosity (%) | Mass (gr) | Calculated Porosity (%) | Porosity Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELONG | 25 | 79.96 | 32.53 ± 0.12 | 78.26 | 2.13 |

| ISOTR | 50 | 80.18 | 32.27 ± 0.18 | 78.43 | 2.18 |

| COMPR | 75 | 79.80 | 32.62 ± 0.15 | 78.20 | 2.01 |

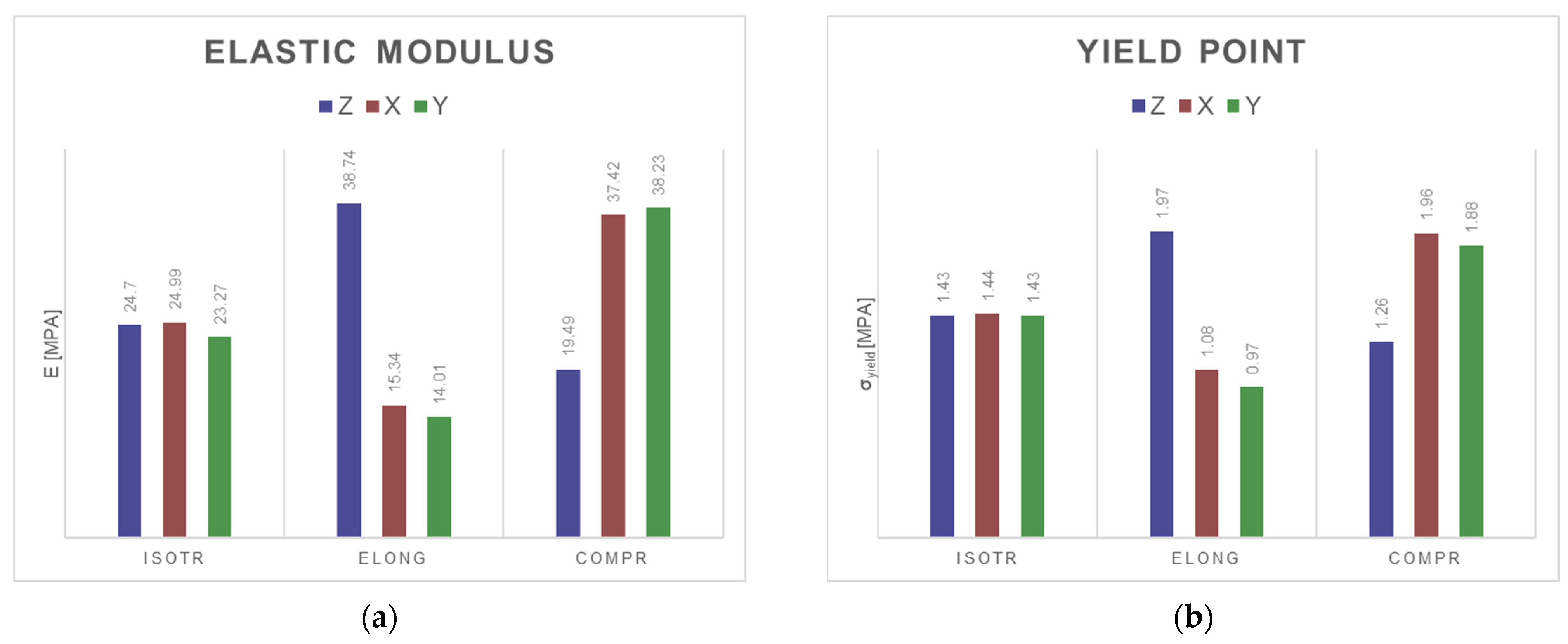

| Elastic Modulus [MPa] | Yield Point [MPa] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Z | X | Y | Z | X | Y |

| ISOTR | 24.70 ± 0.11 | 24.99 ± 0.24 | 23.27 ± 0.15 | 1.43 ± 0.02 | 1.44 ± 0.03 | 1.43 ± 0.02 |

| ELONG | 38.74 ± 0.41 | 15.34 ± 0.35 | 14.01 ± 0.37 | 1.97 ± 0.05 | 1.08 ± 0.05 | 0.97 ± 0.04 |

| COMPR | 19.49 ± 0.24 | 37.42 ± 0.30 | 38.23 ± 0.31 | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 1.96 ± 0.07 | 1.88 ± 0.05 |

| Peak Stress [MPa] | Energy Absorption Density [MJ m−3] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Z | X | Y | Z | X | Y |

| ISOTR | 2.21 ± 0.12 | 2.22 ± 0.11 | 2.02 ± 0.14 | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.75 ± 0.04 |

| ELONG | 2.33 ± 0.17 | 1.87 ± 0.14 | 1.67 ± 0.12 | 0.97 ± 0.06 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.04 |

| COMPR | 2.13 ± 0.11 | 2.30 ± 0.18 | 2.30 ± 0.17 | 0.64 ± 0.02 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.88 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kavafaki, S.; Maliaris, G. Triaxial Compression of Anisotropic Voronoi-Based Cellular Structures. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010471

Kavafaki S, Maliaris G. Triaxial Compression of Anisotropic Voronoi-Based Cellular Structures. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010471

Chicago/Turabian StyleKavafaki, Sofia, and Georgios Maliaris. 2026. "Triaxial Compression of Anisotropic Voronoi-Based Cellular Structures" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010471

APA StyleKavafaki, S., & Maliaris, G. (2026). Triaxial Compression of Anisotropic Voronoi-Based Cellular Structures. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010471