1. Introduction

Water inrush from goaf is a major safety hazard in coal mining worldwide. Ma et al. [

1] analyzed the water inrush mechanism at Dongyu Coal Mine associated with syncline fractured zones, while Sun et al. [

2] provided a comprehensive hydrogeological classification of water inrush accidents in China’s coal mines. With increasing mining depth and intensity, high-pressure goaf water bodies and complex hydrogeological structures make inrush accidents more frequent and more destructive [

3]. Although mine water management has improved and the overall frequency of accidents has decreased, individual events can still cause severe casualties and economic losses [

4].

Field investigations show that water inrush from old goaf water, overlying goaf water of upper seams, and coal-floor aquifers remains one of the main threats to deep coal mining [

5]. During roadway excavation and coal extraction, mining-induced stress redistribution and fracture development may connect water-bearing zones to underground openings, forming water-conducting channels and leading to catastrophic water inrush processes similar to those observed at Dongyu and other mines [

6]. Once such a channel forms, pressurized groundwater can rapidly flow into the workings, and the inrush process often exhibits a staged pattern of slow seepage, sudden increase, and gradual decay [

7]. If timely control and drainage measures are not implemented, serious flooding, equipment damage, and casualties can occur [

3]. In addition, long-term water inflow can weaken the surrounding rock, induce secondary disasters such as roof collapse and floor heave, and aggravate roadway deterioration [

8].

Research on groundwater control and water-retaining structure technology is critical for coal mine safety. Water-retaining coal pillars are a commonly used method in coal mines to block accumulated water in goafs, and their safety depends on the strength degradation and water resistance after long-term water immersion.

Yuan et al. [

9] conducted a study on the long-term immersion process of coal pillar samples under different hydrochemical conditions and water pressures using a self-developed high-pressure mine water-rock coupling test device. They proposed the concept of “damage coefficient” to quantify the strength attenuation. The results showed that the mechanical strength of coal samples decreased significantly after 40 days of immersion, with the most severe damage occurring under acidic conditions. This research provides a basis for the optimal design and stability evaluation of water-retaining coal pillars in operating coal mines. For coal pillar dams in underground reservoirs, Wang et al. [

10] selected coal samples from the Daliuta Coal Mine in the Shendong Mining Area to carry out cyclic water immersion tests. They revealed the cumulative deterioration laws of water content, strength parameters and other properties, and established a damage constitutive model based on the number of water immersion cycles. This study provides support for determining the width of coal pillar dams and ensuring their long-term safe operation.

Underground water hazards are accompanied by multi-field coupling processes, and numerical simulation is an important means to study the instability mechanism of water-retaining coal pillars and optimize their width. Taking the Dongzhuang Coal Mine in Shanxi Province as the engineering background, Chen et al. [

11] established a fluid–solid coupling numerical model based on FLAC3D, and proposed an instability criterion based on the connection between the plastic zone and the seepage zone. The study clarified that coal pillars with a width of 3–5 m are prone to form water-conducting channels, while those with a width of 7–11 m can balance both load-bearing capacity and water-blocking capacity. Galav et al. [

12] constructed a hydro-mechanical coupling numerical model for protective water barrier pillars (PWBPs) using the finite difference method. The results indicated that a reasonable combination of coal pillar width and overburden thickness can effectively control seepage flux and prevent hydraulic failure.

Recent studies have also examined the role of interface mechanics in composite support systems, highlighting the importance of shear transfer, bonding degradation, and frictional behavior under coupled loading conditions. Farbák et al. performed shear tests on concrete-to-concrete interfaces and showed that interface roughness and bonding conditions significantly affect shear transfer and the overall strengthening performance of composite concrete structures [

13]. Similarly, Gago et al. conducted large-scale shear box tests on interfaces between construction materials and soils, demonstrating that interface shear strength varies substantially with normal stress and material type [

14]. These works have advanced understanding of contact responses in concrete-concrete and concrete-soil/steel-soil interfaces. However, the specific combination of a rigid water-blocking wall with a coal pillar under high hydraulic gradients remains underexplored, particularly with respect to the anti-sliding stability and load-transfer mechanisms at the wall-pillar interface. This gap is of practical importance in deep coal mines where old goaf water bodies exert strong seepage and mechanical influence on adjacent roadways.

Experimental analysis is likewise indispensable for assessing groundwater control and water-resisting structures. Zhang [

15] performed seepage experiments on karst collapse pillar (KCP) fillings and showed that when flow-path scale and filling porosity increase concurrently, permeability can surge by roughly two orders of magnitude; they attributed water-inrush initiation to particle washout and framework collapse. Li, Z. [

16] employed a meter-scale similarity model combined with numerical coupling to quantify the deformation-failure process of shallow, weakly cemented overburden and the evolution of WCFZ height, clarifying the layered cooperative caving that follows the failure of key weakly cemented layers.

Despite these advances, the seepage and load-bearing mechanisms of coal pillar-water-blocking wall composite structures remain insufficiently understood [

17]. In many deep mines, relocating roadways to avoid old goaf water can be uneconomical or even impossible, and there is a strong engineering demand to upgrade existing pillars by constructing rigid water-blocking walls [

18]. In the S5205 return airway of Yuwu Coal Mine, a severely flooded old goaf with a water head difference of approximately 40 m was encountered adjacent to a 10 m coal pillar. To avoid roadway relocation and ensure safe mining, it is necessary to enhance both the seepage resistance and the load-bearing capacity of this pillar through composite structural measures.

In this context, the present study develops a hydro-mechanical coupling model of a coal pillar-water-blocking wall composite structure under high water pressure using FLAC3D6.0 [

19]. By monitoring pore-water pressure, stress, and saturation at multiple stages, the spatio-temporal mechanism of seepage resistance and load bearing of the composite structure is revealed. Similar-material shear tests are conducted to assess the anti-sliding performance of the wall-pillar interface. This study makes several novel contributions: (1) systematic investigation of a coal pillar-water-blocking wall composite structure as an integrated load-bearing and seepage-resisting system; (2) introduction of a dual-index evaluation framework combining elastic core volume fraction and permeability connectivity index for comprehensive stability assessment; (3) experimental examination of anti-sliding behavior at the wall-pillar interface through similar-material shear testing. The results provide technical support and design guidance for coal pillar-water-blocking wall composite structures in high-pressure goaf water control.

3. Reconstruction of the Hydro-Mechanical Environment

3.1. Engineering Background

The mining depth of the 3# coal seam in Yuwu Coal Mine is approximately 610 m, with an average thickness of about 6.3 m.

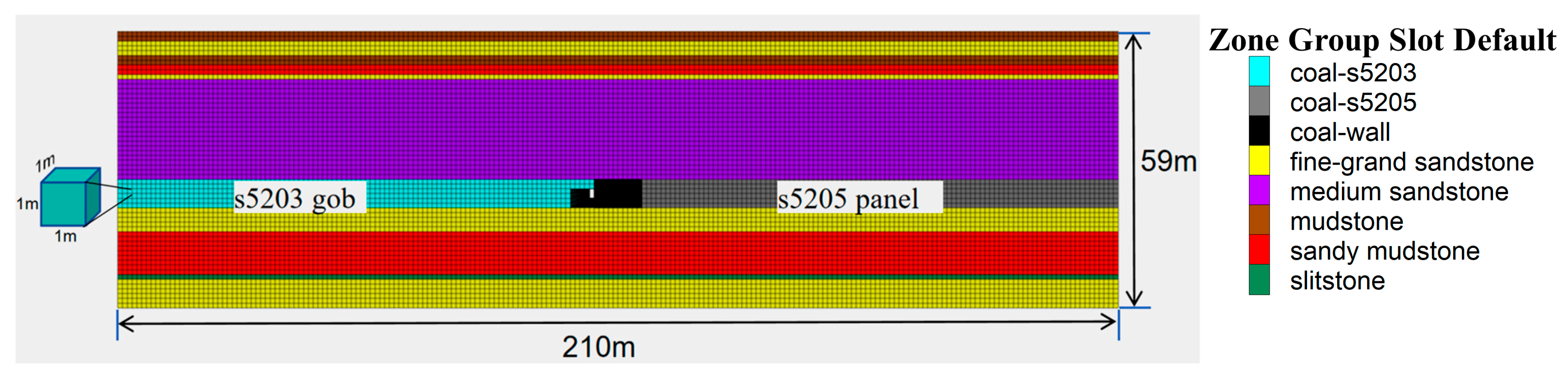

Figure 1 presents the layout of the S5203 and S5205 mining panels and a representative stratigraphic column from an exploration borehole in the S5205 return airway area. In the plan view, the S5203 panel (east) has been completely extracted and its goaf is flooded, forming a high-pressure water body with a measured water level elevation of +351.375 m, an inundated area of 200,724 m

2, and a total volume of 64,231 m

3. The S5205 panel (west) is the currently active mining area. The two panels are separated by a 10 m waterproof coal pillar, which is the focus of this study. The S5205 return airway is driven along the western side of this pillar, placing it adjacent to the flooded goaf and subject to potential water hazard. The column displays the vertical sequence of rock layers from the overlying mudstone and sandstone units (including the main water-bearing fractured sandstone in the roof) through the 6.35 m thick No. 3 coal seam to the underlying strata. Layer thicknesses and lithological properties are consistent with the parameters adopted in the numerical model (

Table 1) and are derived from detailed geological survey data. The water head difference of approximately 40 m corresponds to the elevation difference between the goaf water level and the S5205 roadway floor.

If the existing 10 m pillar is not reasonably designed and reinforced, coupled “seepage-roadway excavation–mining” processes may induce water hazards and destroy the roadway in a manner similar to documented goaf water inrush accidents [

2]. To avoid relocating the roadway and to improve the efficiency of resource recovery, it is urgent to enhance the seepage resistance and bearing capacity of the existing waterproof pillar between S5203 and S5205.

3.2. Numerical Model Setup

Based on site investigation and geological data, a three-dimensional numerical model with dimensions of 100 m × 210 m × 59 m is established. The model dimensions of 100 m × 210 m × 59 m were determined based on established guidelines for geomechanical modeling [

33]. Horizontally, the model extends approximately 45–50 m on each side of the coal pillar-roadway system, exceeding the recommended minimum distance of 3–5 times the characteristic excavation dimension (~15 m) to minimize boundary effects. Vertically, the model encompasses the complete stratigraphic sequence influencing stress distribution and groundwater flow, including the main roof aquifer (medium-grained sandstone, 21.7 m), the No. 3 coal seam (6.35 m), and surrounding strata. The model consists of about 1.24 million zones, with local mesh refinement applied around the coal pillar, roadway, and wall-pillar interface to accurately capture stress gradients, seepage fronts, and plasticity development. (

Figure 2). Meshing parameters were adjusted to balance analysis accuracy, computation time, and element count, with special attention given to enhancing mesh quality in critical areas [

34], we have chosen a 1 m block as the base grid and further refined the grid resolution in the coal pillar area by applying a 0.5 m refined mesh. The assumption of horizontally layered strata with constant thickness is based on detailed borehole data and geological survey reports from the S5205 and S5203 panels, which show minimal dip and lateral variation within the modeled domain (dip < 1.5°). According to in situ stress measurements, a vertical stress of 9 MPa is applied on the model top, the bottom is fixed, and the four lateral boundaries are constrained horizontally. Prior to finalizing the computational mesh, a systematic mesh convergence study was conducted following established guidelines for geomechanical numerical modeling [

34]. Three mesh configurations were compared: a coarse mesh with 1.5 m base element size (~0.52 million zones), the adopted mesh with 1.0 m base size and 0.5 m refinement in critical regions (~1.24 million zones), and a fine mesh with 0.75 m base size and 0.25 m refinement (~2.18 million zones). Key response quantities including peak vertical stress, minimum elastic core width, elastic zone volume fraction, and permeability connectivity index were monitored at each simulation stage. Relative to the adopted mesh, the coarse mesh produced discrepancies of 8–12% in peak stress and underestimated the elastic core width by 0.4–0.6 m, while the fine mesh showed differences of less than 2.5% in all monitored quantities but required 3.2 times longer computation time. The adopted mesh configuration therefore provides an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, with local refinement ensuring adequate resolution of stress gradients and seepage fronts in the coal pillar-wall-roadway region.

The numerical simulation process is divided into three stages according to the actual mining sequence:

Stage I: Extraction and caving of the S5203 panel, compaction of the goaf, and infiltration of groundwater.

Stage II: Excavation of the S5205 return airway, casting of a reinforced concrete water-blocking wall adjacent to the coal pillar, and roadway support.

Stage III: Retreat mining of the S5205 panel.

The numerical analysis was performed as a staged construction simulation with full state continuity between stages, following established practices for path-dependent geomechanical modeling. After initial in situ stress equilibrium, Stage I (S5203 extraction and goaf caving) was solved to mechanical and hydraulic equilibrium. All field variables—including displacements, effective stresses, plastic strains, damage variables, pore-water pressures, and saturation levels—were retained at the end of this stage and used directly as initial conditions for Stage II (roadway excavation and wall construction) through FLAC3D’s sequential solution capability, without any field reset. Likewise, the end-of-Stage-II fields served as initial conditions for Stage III (panel retreat). This approach ensures that the deformations, stress redistributions, and damage accumulated during each stage are fully transferred to subsequent stages, capturing the path-dependent evolution of the composite structure. Such continuity is essential for realistic assessment of cumulative damage and long-term seepage behavior in barrier pillar systems [

11]. FLAC3D was selected for its explicit Lagrangian formulation that robustly handles large plastic deformations and strain-softening characteristic of coal pillar failure, its integrated hydro-mechanical coupling based on Biot’s theory with stress-dependent permeability updating, and its well-validated contact elements for wall-pillar interface simulation. Additionally, FLAC3D has extensive precedent in coal pillar and barrier pillar research [

11], providing a validated framework for this analysis.

Rock strata parameters used in the model (

Table 1) are derived from laboratory tests and field data and are consistent with typical coal measure sequences reported for deep mines [

33]. Numerical implementation of the coupled hydro-mechanical processes is conducted using FLAC3D, which has been widely used for similar problems in rock and coal engineering [

28]. The geological setting consists of competent coal-measure rocks at approximately 610 m depth, where the interfaces between rock layers are well-bonded and do not exhibit significant slip under typical mining conditions. Accordingly, all rock and coal layer contacts are modeled using a bonded continuum approach with perfect interlayer continuity, following standard practice for deep mining simulations [

33]. This assumption is justified by the relatively competent nature of the strata, the sub-horizontal bedding (<1.5° dip), and the high normal stresses at depth that inhibit interface separation.

3.3. Mechanical Environment After Goaf Caving and Compaction

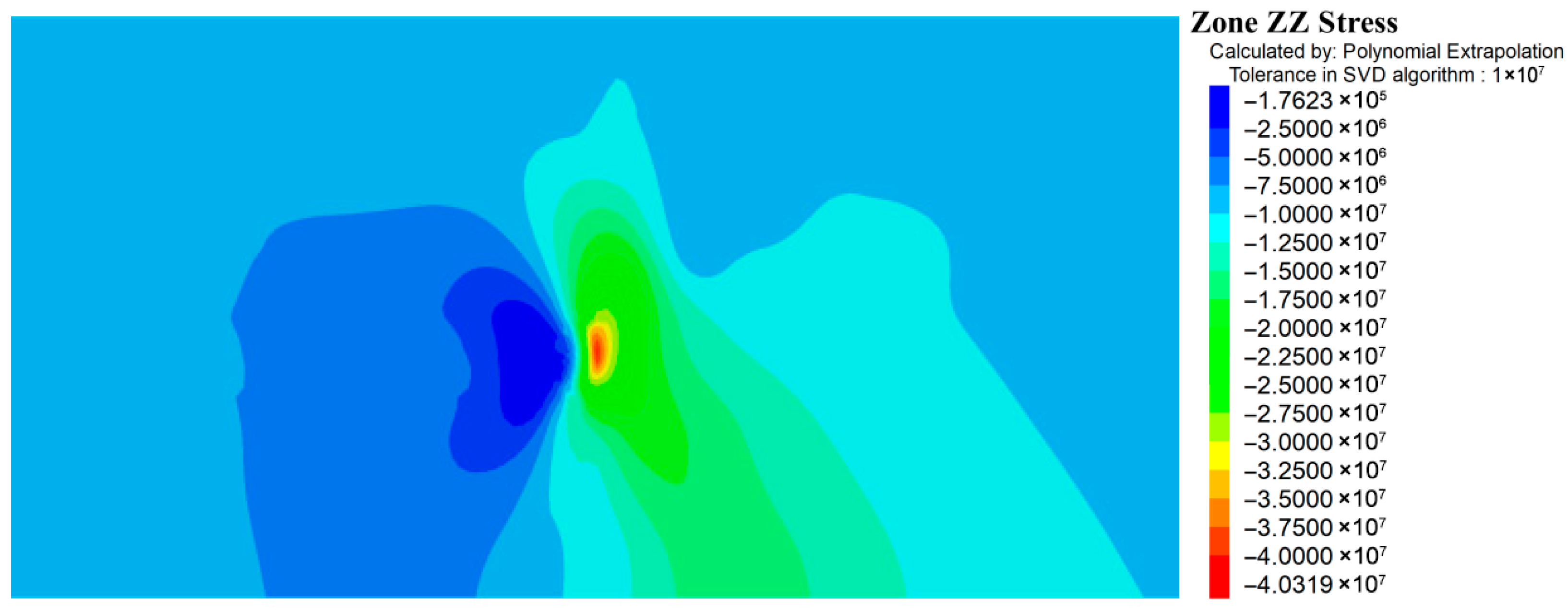

In Stage I, after initial in situ stress equilibrium, the S5203 panel is excavated and the goaf is allowed to cave and compact. The vertical stress distribution shows a typical three-zone pattern after caving (

Figure 3):

- (1)

Stress relief zone in the goaf:

The stress inside the goaf is significantly reduced, forming a low-stress zone. The vertical stress in the central region decreases to about 0.2–0.3 times the original in situ vertical stress, due to the loose stacking of caved rock with limited bearing capacity, similar to observations in other longwall panels [

33].

- (2)

Stress concentration zone in the coal pillar:

A pronounced stress concentration develops within about 3.5 m from the goaf side of the 10 m coal pillar. The vertical stress peak reaches 3–4 times the original vertical stress, with a concentration factor K ≈ 3–4, consistent with the load-transfer mechanism via a pressure arch in the overburden [

29].

- (3)

Stress transition zone:

Between the goaf and the pillar, a stress transition zone with a width of about 5–8 m forms. Stress gradually increases from low values in the goaf to high values in the pillar, indicating a gradual transfer of load through the surrounding rock.

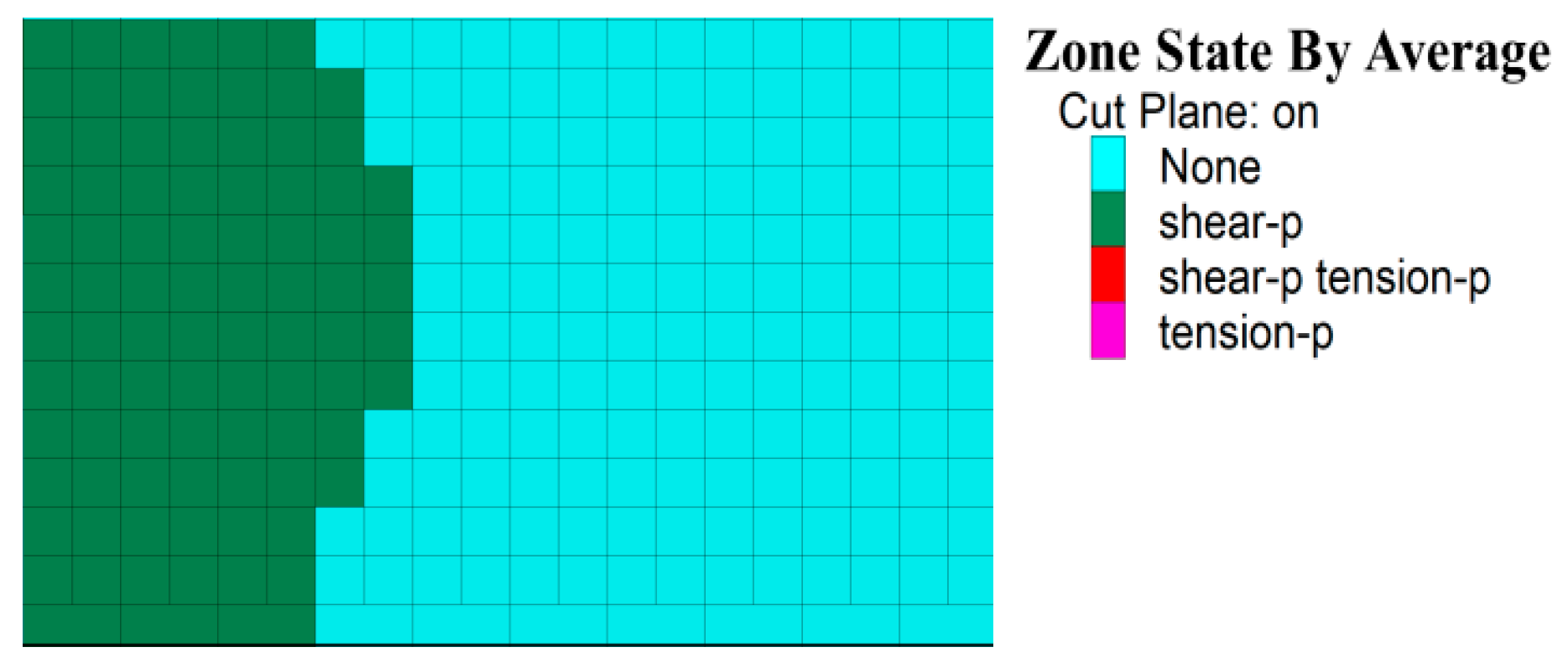

The plastic zone distribution after caving shows significant plastic failure at the pillar edges, especially on the goaf side due to stress concentration, as shown in

Figure 4. The plastic zone forms a band with a depth of about 2–3 m, indicating that the pillar is in an elastoplastic state. The effective load-bearing width of the pillar is therefore reduced to approximately 7–8 m, and the elastic zone volume fraction is about 64%.

3.4. Coal Pillar Under Long-Term Seepage from the Goaf

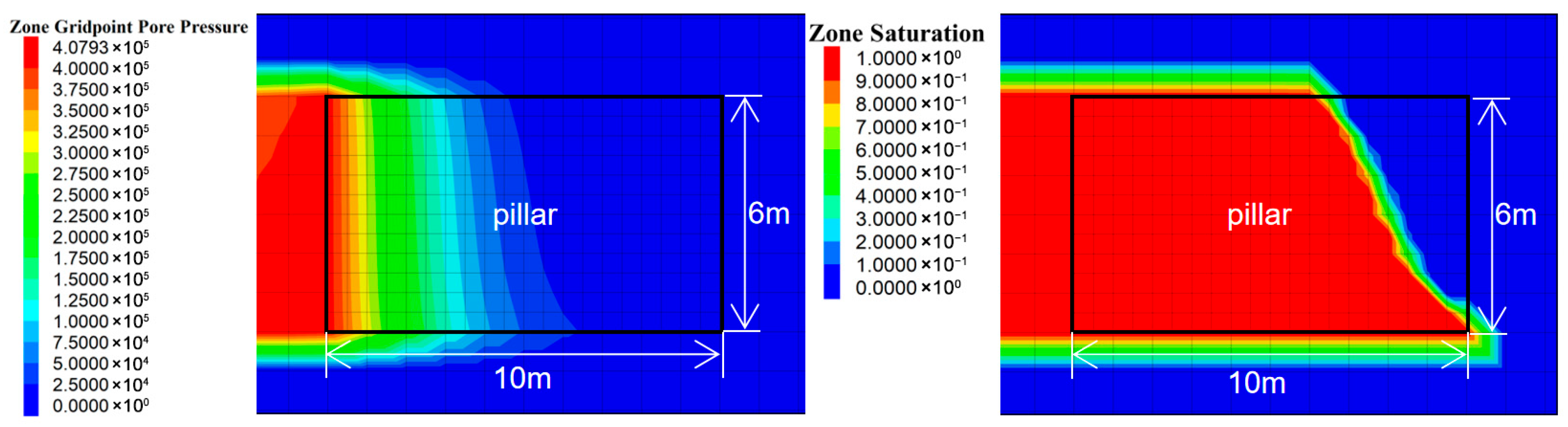

After complete caving and compaction of the S5203 goaf, a well-developed water-conducting fracture zone forms in the roof. The goaf is fully flooded, and the measured water pressure ranges from 0.07 to 0.4 MPa. For safety, the maximum water pressure of 0.4 MPa is uniformly applied along the sidewall of the pillar facing the goaf in the model.

Core samples and typical data for deep, relatively low-permeability coals indicate that the initial permeability is on the order of 10−12 m2. This value is used as the initial permeability, and a seepage time of three years is simulated under hydro-mechanical coupling. Due to stress concentration and partial plastic failure near the goaf, microcrack networks form and accelerate water penetration.

After three years, the pore pressure and saturation distributions exhibit a clear gradient in the penetration of high-pressure water, as shown in

Figure 5.

High-pressure infiltration front (0–3 m from the goaf): pore-water pressure reaches 0.25–0.35 MPa (62.5–87.5% of the applied pressure). Water quickly infiltrates into the pillar through the microfracture network in the plastic zone.

Transition zone (3–6 m): pore-water pressure decreases rapidly to 0.1–0.2 MPa. Coal in this region remains largely elastic with relatively low porosity, providing resistance to water penetration.

Low-pressure stable zone (6–10 m): pore-water pressure remains below 0.05 MPa, close to the initial condition, indicating that the pillar is not fully penetrated after three years and the deep part still retains effective water-blocking capacity, although some seepage channels may form near the floor causing mudded coal during excavation.

The saturation distribution shows that the pillar region adjacent to the goaf is nearly saturated, resulting in strength and stability degradation, whereas the deep region with lower saturation still maintains good structural integrity. Overall, long-term water infiltration substantially weakens the outer part of the pillar, while the inner part remains relatively intact but carries the risk of gradual deterioration if damage extends inward over time.

4. Seepage and Load-Bearing Performance of the Composite Structure

4.1. Performance During Roadway Excavation

Based on the reconstructed hydro-mechanical environment of the coal pillar-water-blocking wall system, Stage II simulates roadway excavation. The roadway cross-section is 5.2 m × 2.8 m. Water-blocking walls with thicknesses of 0 m (no wall), 0.5 m, 1.0 m, 1.5 m, 2.0 m, and 2.5 m are constructed adjacent to the pillar. After wall construction and support, hydro-mechanical coupling is activated and the system is simulated for three years. Twenty monitoring points are placed near the geometric center of the composite structure to track pore-water pressure and three-dimensional stress (

Figure 6).

Compared with Stage I, excavation of the roadway allows further ingress of groundwater. In the case without a wall (pure coal pillar), the pillar becomes fully penetrated, and the maximum pore pressure at the deep bottom of the pillar (roadway side) reaches about 0.0025 MPa. In an actual mine environment, such penetration would result in seepage and mudded coal and—if sufficiently conductive channels develop—could even lead to water inrush similar to those reported in old-goaf related accidents [

35].

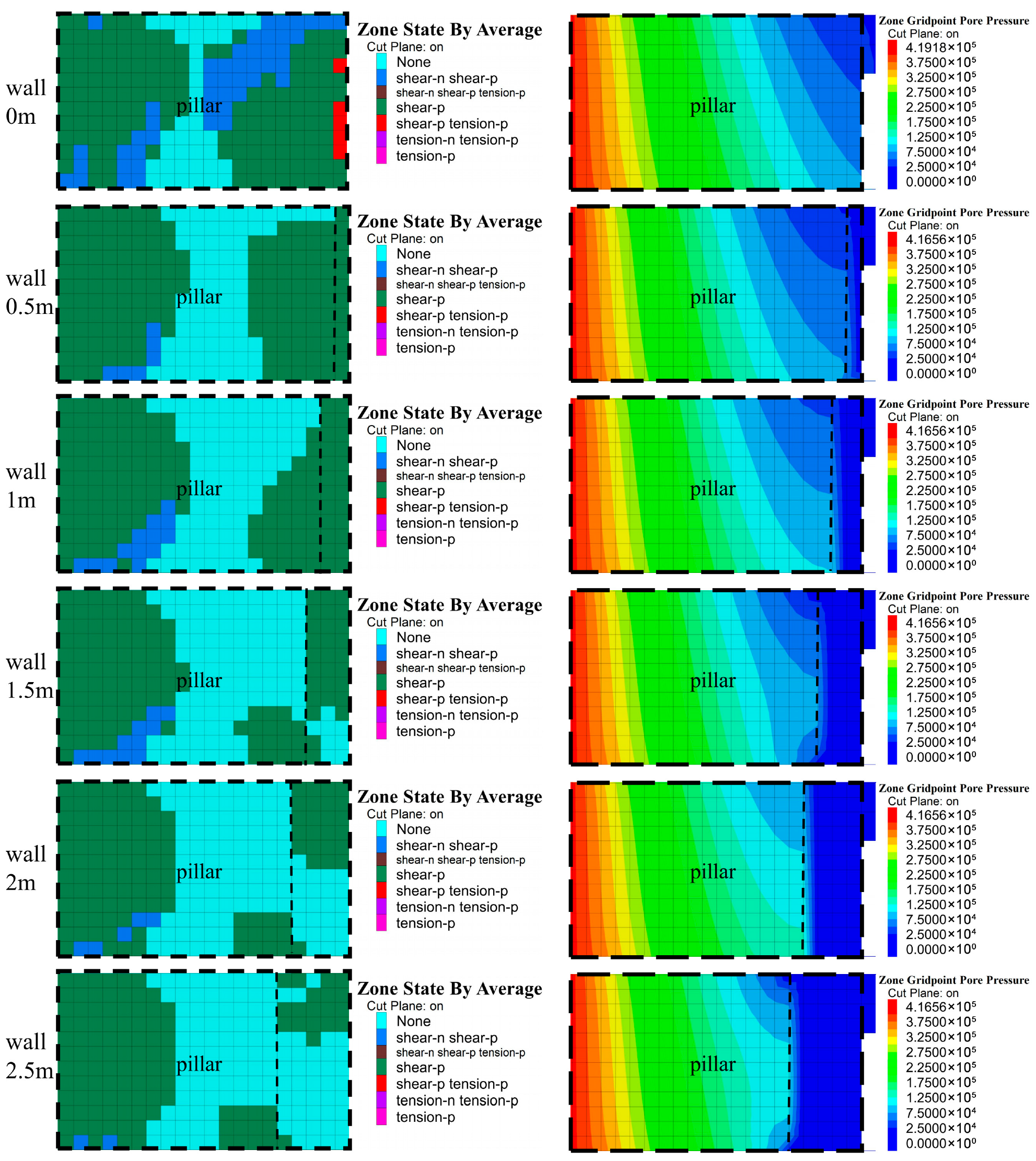

As shown in

Figure 7,when water-blocking walls with thicknesses of 0.5–2.5 m are installed, they provide effective seepage barriers, and the wall thickness becomes the primary seepage-resisting zone. Pore pressure in the pillar decreases significantly with increasing wall thickness, and the high-saturation zone shrinks towards the goaf side.

The element state and vertical stress distribution in the excavation stage show that different wall thicknesses lead to different failure patterns. In the pure coal pillar case, under the combined effects of goaf caving and roadway excavation, the pillar near the roadway suffers both shear and tensile failure, and plastic zones extend up to about 4 m from the roadway side. On the goaf side, a vertical stress peak of about 42.5 MPa develops at 3–4 m from the goaf. The plastic zones are significantly larger than in Stage I, and the minimum elastic core width is reduced to about 1.5 m, implying a high risk of instability during subsequent mining.

For the 0.5 m wall, the thin wall experiences a peak stress as high as 98.7 MPa, making it susceptible to failure. The plastic zone map shows that the lower-middle part of the wall and the adjacent pillar region have yielded, yet the minimum elastic core width remains around 3 m and the composite structure retains acceptable load-bearing capacity.

For the 1.0 m wall, the stress peak drops to 67.8 MPa, and the wall remains elastic. However, the stress concentration at the wall base induces limited plasticity in the coal within 0.5–1.0 m of the interface; the minimum elastic core width is about 4 m, indicating good performance.

For wall thicknesses of 1.5–2.5 m, the peak stresses further decrease to 60.4, 58.5, and 57.4 MPa, respectively. The walls remain entirely elastic, and the stress distribution within the pillar becomes more uniform, with no additional plastic expansion on the wall side compared to Stage I. These trends are consistent with the concept of water-barrier pillars and composite support structures in which a rigid element undertakes a dominant share of the load [

36].

4.2. Performance During Panel Retreat

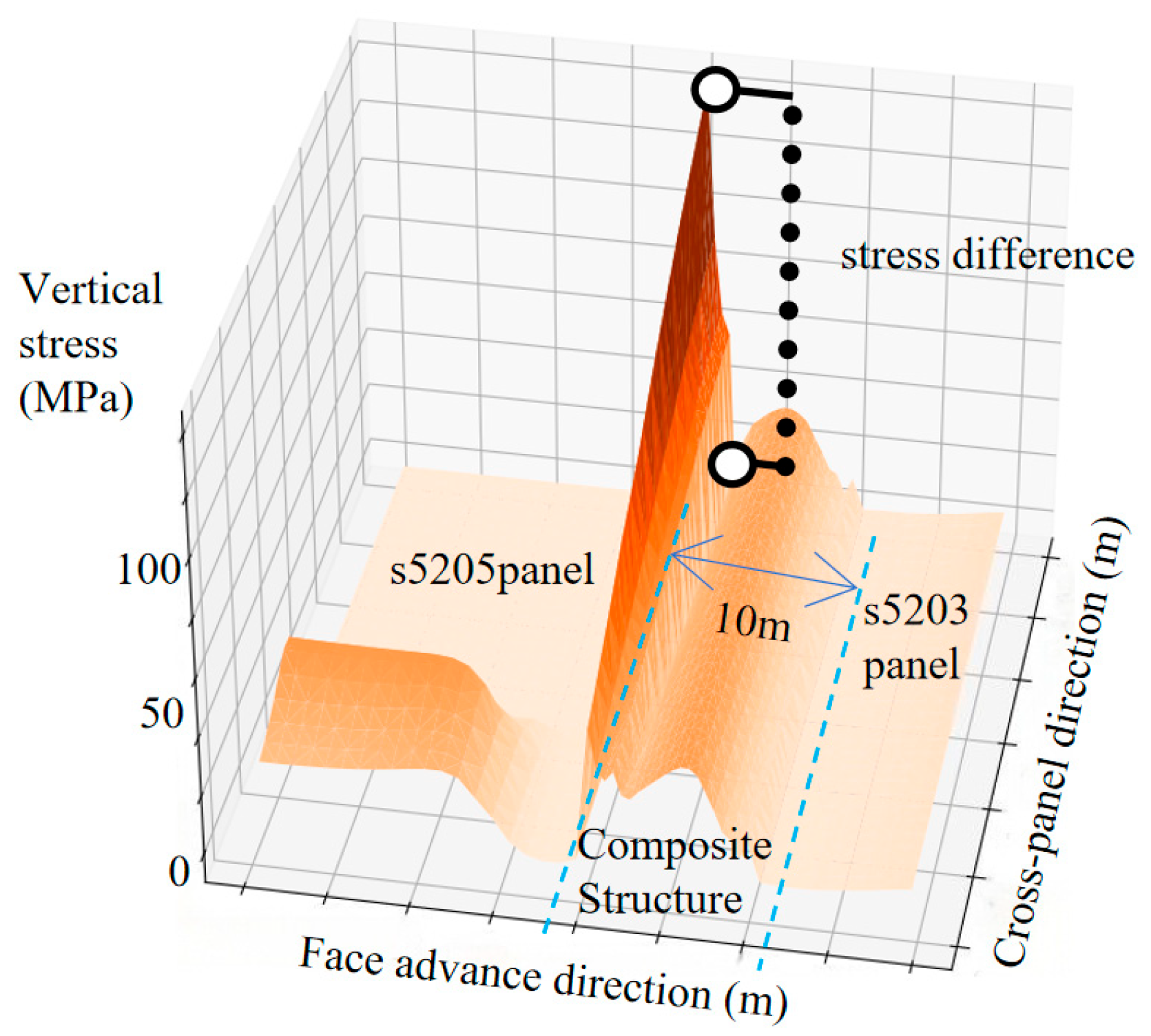

Based on the hydro-mechanical field at the end of Stage II, Stage III simulates retreat mining of the S5205 panel. A 50 m wide strip of coal is extracted, forming a new goaf. A 15 m rear unloading zone and a subsequent redistribution zone are defined above the mined-out area. The model is run to equilibrium, and the vertical stress on top of the coal seam is extracted, as shown in

Figure 8.

The S5205 panel exhibits a typical pattern of a front abutment pressure zone, an unloading zone behind supports, and a redistribution zone, in agreement with established longwall mining observations [

37]. In the absence of a wall, the creation of the new goaf redistributes roof loads, part of which transfers to the pillar. The pillar adjacent to the redistribution zone shows a distinct stress concentration with a peak of 54.2 MPa, forming a high-stress band 3–4 m wide in the pillar center. In the front abutment zone of the coal face, the peak stress is about 42.2 MPa.

With a 0.5 m wall, the wall exhibits good load-bearing performance, and the vertical stress peak shifts to the wall, reaching 55.6 MPa. The maximum stress inside the pillar is reduced to 47.7 MPa, and the front abutment pressure peak in front of the working face decreases to 38.8 MPa. This helps maintain roadway stability and reduces support difficulties.

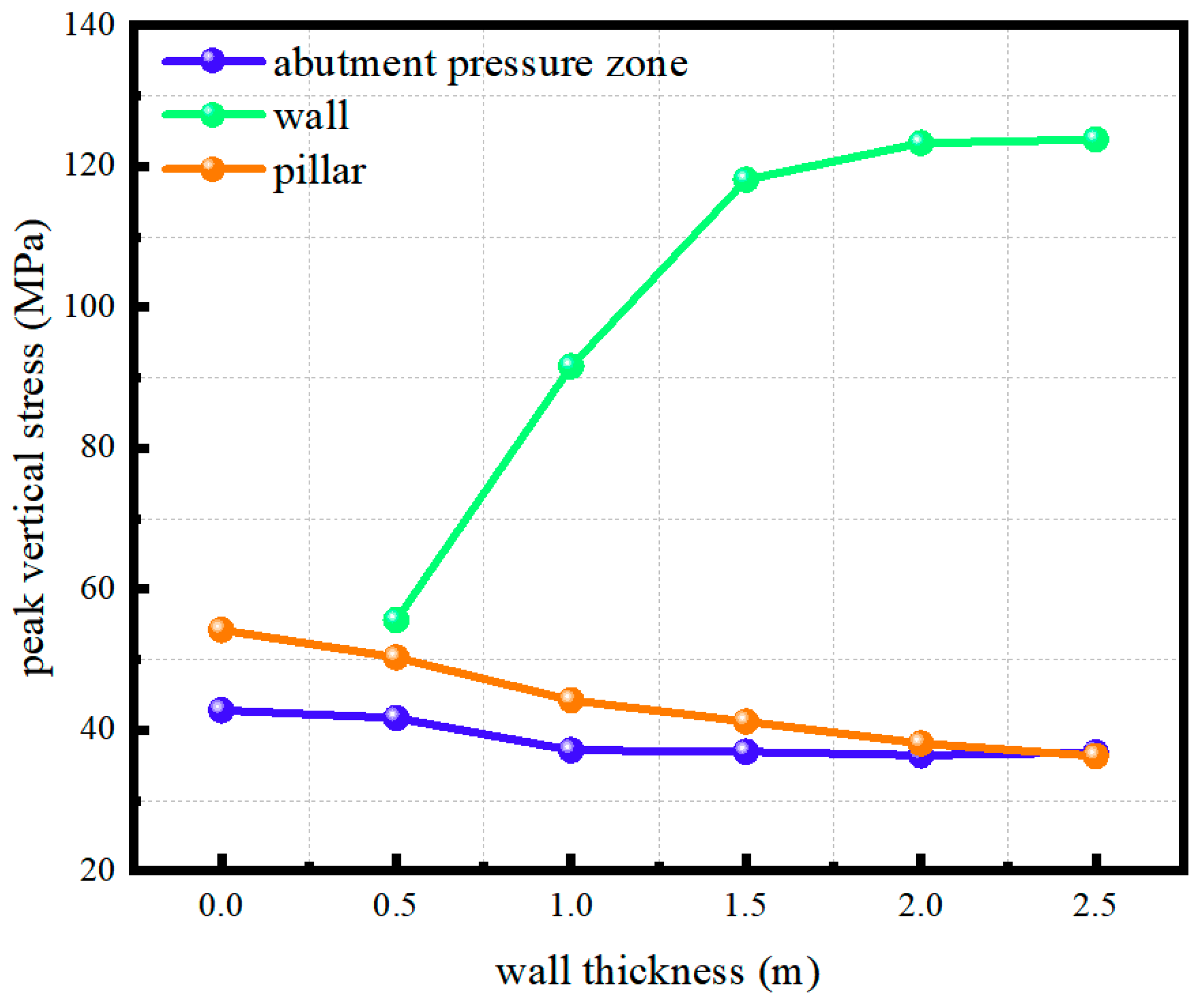

For wall thicknesses of 1.0–2.5 m, the load sharing by the wall becomes more pronounced. The peak vertical stresses at the wall top increase to about 91.6, 118.1, 123.3, and 123.8 MPa, respectively (

Figure 9), while the peak stresses inside the pillar decrease and the stress distribution becomes more uniform with no localized high-stress zones. The front abutment pressure ahead of the face continues to decrease and becomes more evenly distributed, significantly improving roadway stability.

To assess failure patterns, a vertical slice is taken through the composite structure at the boundary with the redistribution zone, as shown in

Figure 10. For the case without a wall, the minimum elastic core width of the pillar is only about 0.5 m, and the elastic zone volume fraction is merely 16.7%. Plastic zones are nearly connected, indicating a high risk of instability. For wall thicknesses of 0.5 and 1.0 m, the minimum elastic core width is about 2 m, and the elastic volume fractions are 30.4% and 40.0%, respectively; plastic zones have not yet penetrated the pillar, and the structure still retains some bearing and water-blocking capacity, though the wall undergoes partial shear failure.

For wall thicknesses of 1.5–2.5 m, the minimum elastic core width decreases slightly to about 1.5 m. Nonetheless, a continuous elastic block measuring approximately 4.0–4.5 m in height and 3.5–4.5 m in width remains inside the pillar, and the elastic volume fractions are 45.8%, 48.3%, and 50.4%, respectively. Thus, the pillar can withstand additional loads induced by mining and retains excellent seepage-resistant capacity.

Pore-pressure analysis reveals that, without a wall, the pillar becomes fully penetrated by this stage, with water-conducting channels extending to the roadway side. With a 0.5–2.5 m wall, however, the wall effectively blocks the influx of water from the old goaf into the retreating working face, consistent with the function of well-designed water barrier pillars [

30].

4.3. Mechanisms of Performance Enhancement

The above results show that the coal pillar-water-blocking wall composite structure significantly outperforms a single coal pillar in both load-bearing and seepage resistance. Two key mechanisms are identified:

- (1)

Vertical load redistribution:

Owing to its higher stiffness and strength, the wall undertakes a greater share of the overburden load, causing vertical stress concentration to shift from the pillar to the wall. As a result, the high-stress region within the pillar shrinks, stress peaks decrease, and the elastic core is better preserved, thereby improving the stability of both the pillar and the roadway [

38].

- (2)

Enhanced lateral confinement (confinement effect):

The coal pillar is subject to multi-axial loading in the in situ stress field, but its exposed surfaces (toward the goaf and roadway) lack restraint and are prone to lateral expansion and plastic failure. Installing a rigid wall along one free side significantly strengthens lateral confinement, changing the internal stress state from partially constrained multi-axial stress to a more fully confined triaxial compression state. Classical rock mechanics studies have shown that the peak strength of rock or coal under confining pressure is much higher than its unconfined compressive strength [

39]. In essence, the wall increases the effective confining pressure acting on the coal pillar, delays plastic zone expansion and penetration, and thus improves ultimate load-bearing capacity.

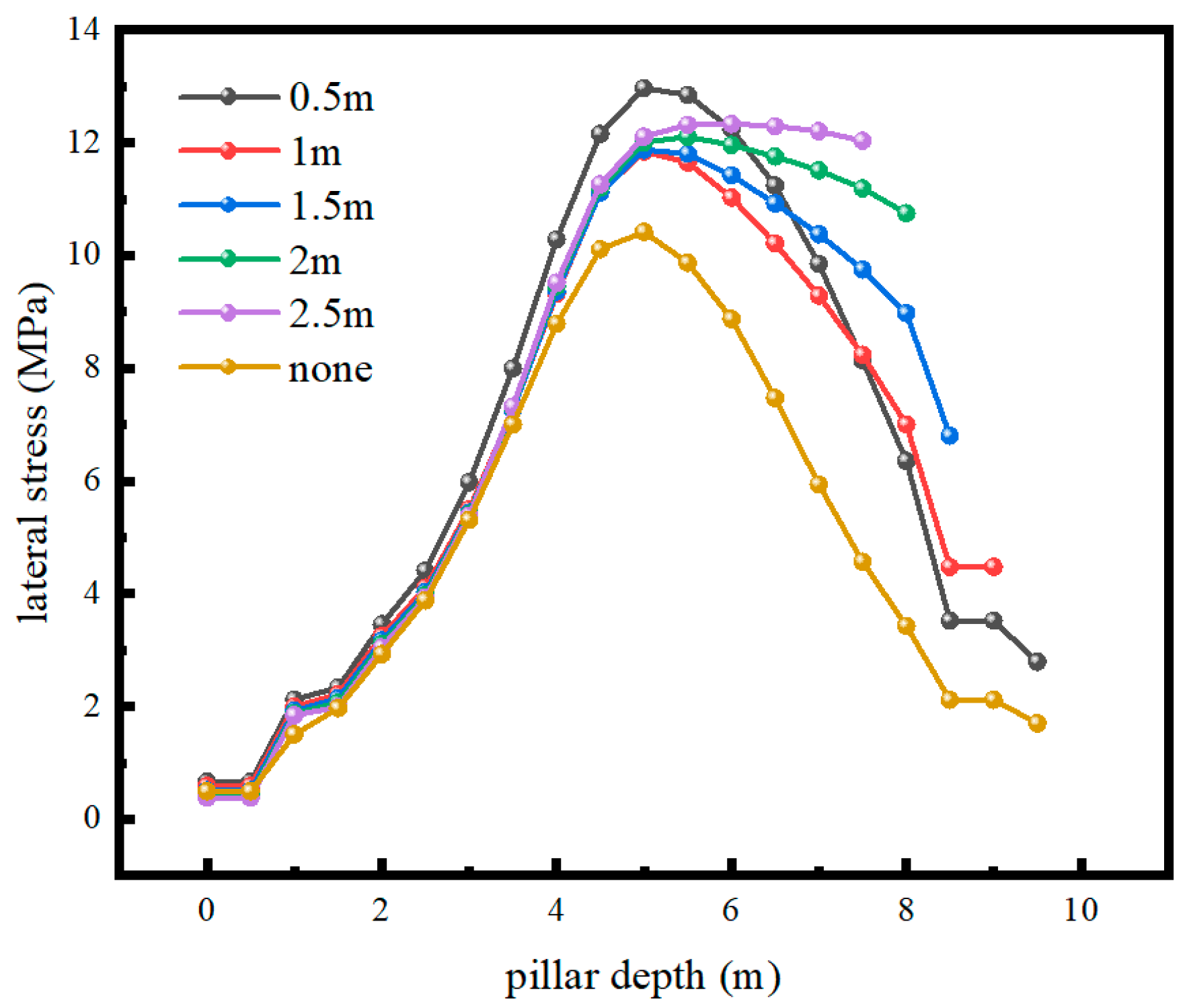

Monitoring results show that, compared with a single pillar, the composite structure exhibits higher lateral stresses and lower vertical stress peaks throughout the pillar width, as shown in

Figure 11. For example, with a 0.5 m wall, the lateral stress at mid-depth increases significantly relative to the pure pillar; with a 2.5 m wall, the lateral stress near the wall can be more than 1.5 times that of the pure pillar while the vertical peak stress inside the pillar is simultaneously reduced. This pattern is consistent with the preservation of a larger and more continuous elastic core.

4.4. Anti-Sliding Tests of the Composite Structure

Numerical results indicate that, due to the strength contrast between the wall and the pillar, the vertical load at the top of the wall can reach up to about 123 MPa, while stress in the adjacent pillar drops sharply to about 14 MPa, as shown in

Figure 12. According to Equation (9), such a sharp change in stress across the wall-pillar interface may induce sliding along the interface and compromise structural stability and safety. To better understand this phenomenon and its influence on composite performance, similar-material tests were designed and conducted.

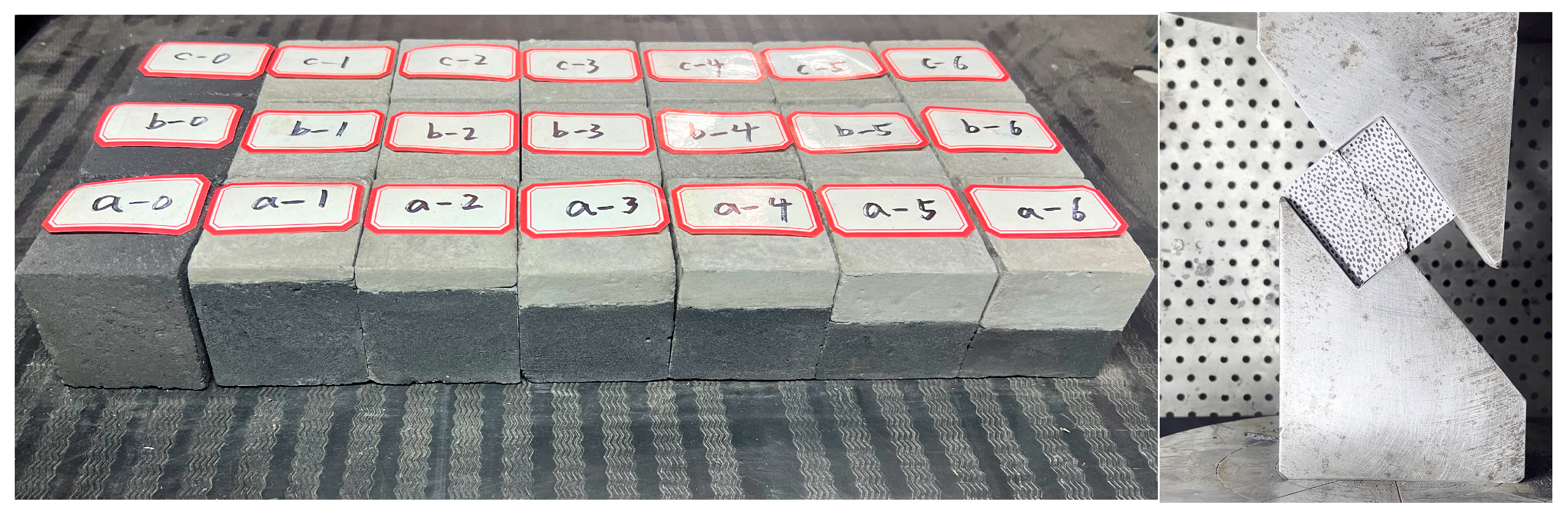

A geometrical scale ratio of 1:100 is adopted, and stress similarity principles are followed. The elastic-dominated region from 5 to 10 m depth in the pillar (where 0–5 m is already plastic) is used as the prototype for the model. The similar-material mix for the coal pillar is: 0.1 mm coal powder/cement/water = 5:1.1:1.9 (by mass), and for the concrete wall it is cement/river sand/water = 1:1:1.2. Specimens are cured under controlled temperature and humidity.

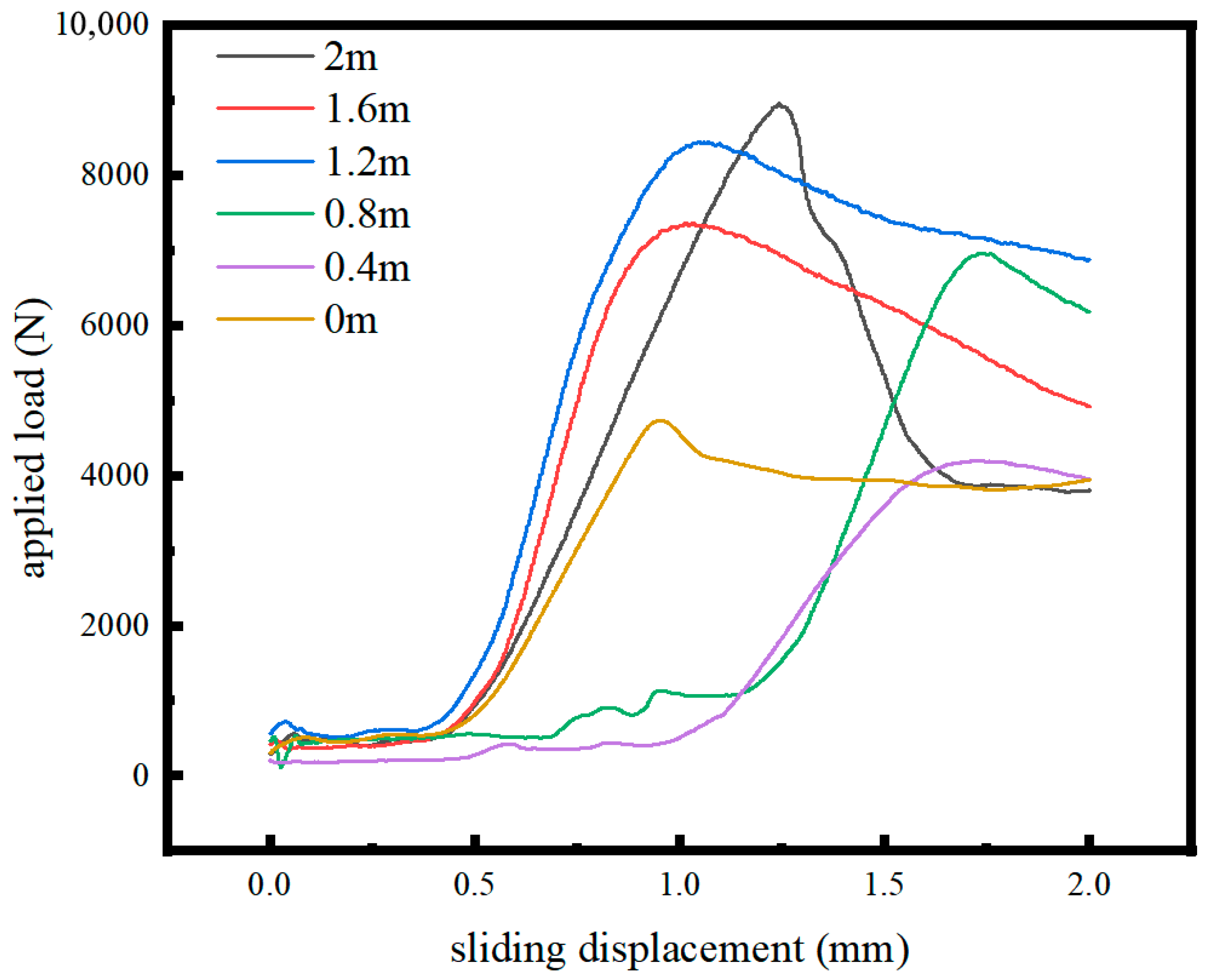

Combined wall-pillar specimens are subjected to quasi-static shear loading, as shown in

Figure 13. The distance between the shear load application surface and the wall-pillar interface is set to 0, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, and 2.0 m (prototype values) in different groups. Sliding displacement is monitored throughout the tests.

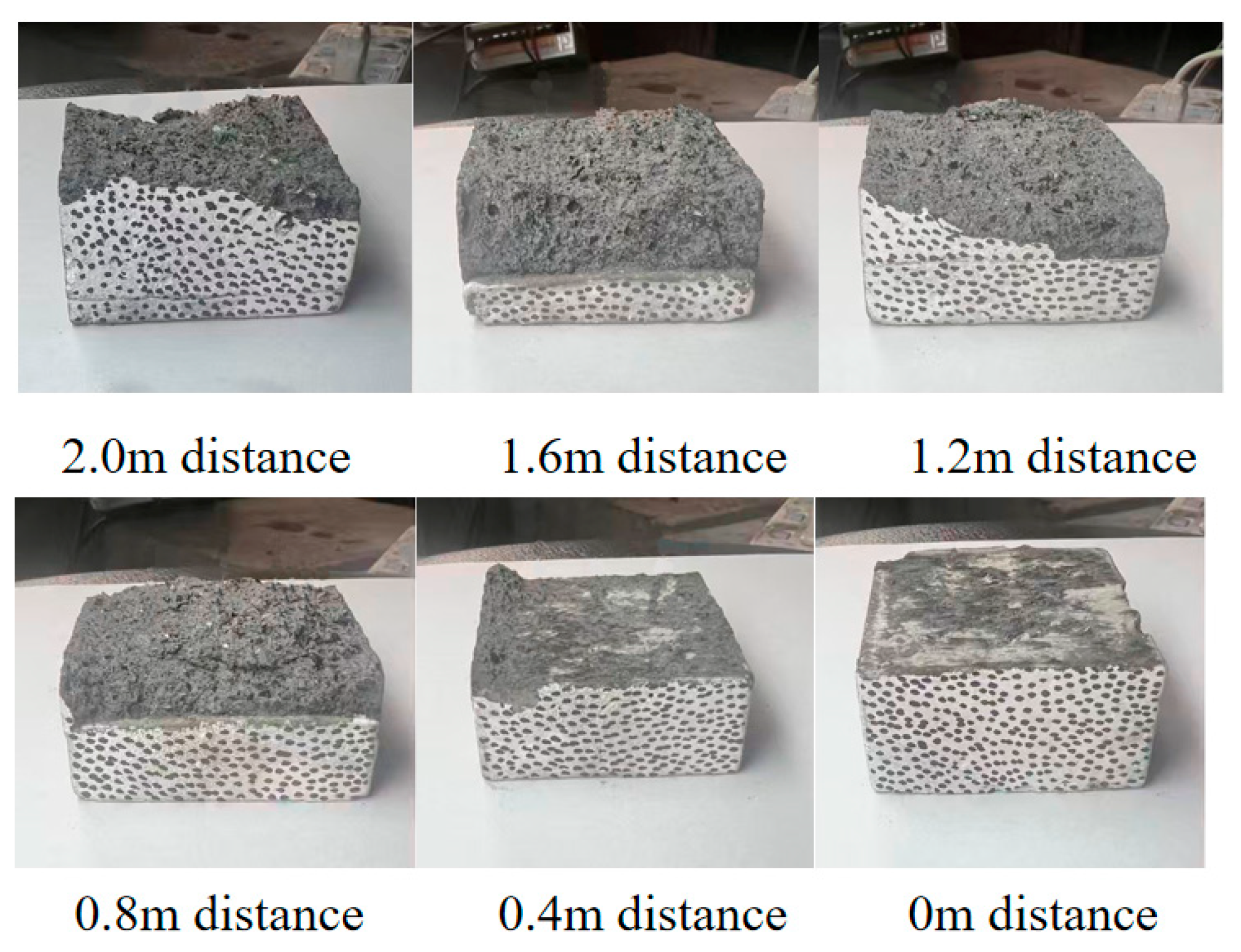

The failure sections (

Figure 14) indicate that, when the distance between the shear load application point and the interface is ≥0.8 m, shear forces are primarily carried by intact coal, as shown in

Figure 15. The critical shear loads for distances of 0.8–2.0 m are significantly higher than those for shorter distances, and failure planes develop mainly inside the coal pillar, producing partial exposure of the interface. When the distance is ≤0.4 m, the critical shear load drops markedly. In this case, the failure plane coincides with the wall–pillar interface, where shear stress exceeds frictional resistance and large-scale sliding occurs along the interface, severely reducing the cooperative load-bearing capacity.

These results demonstrate that targeted measures are needed to enhance anti-sliding capacity in engineering practice. Structurally, anti-sliding stability can be improved by installing rock bolts, cables, or shear keys, as commonly adopted in composite support structures and barrier pillars [

12]. For example, grooves can be cut into the coal pillar and matching convex shear keys formed on the wall edge to achieve mechanical interlocking between the two materials, thereby improving the interface shear resistance and overall composite stability.

5. Conclusions

Focusing on the key problem of controlling high-pressure water hazards in deep coal mine goaf, this study proposes and systematically investigates a coal pillar–water-blocking wall composite structure. FLAC3D numerical simulations combined with similar-material mechanical tests are used to reveal the seepage–bearing mechanism of the composite structure under multi-physical (stress–seepage–damage) coupling. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

The composite structure exhibits significantly better load-bearing capacity than a single coal pillar. The water-blocking wall effectively shares the overburden load and redistributes vertical stress, reducing stress peaks and plastic zone extent in the pillar and preserving an elastic core. For wall thicknesses ≥0.5 m, the minimum width of the elastic core exceeds about 2 m under the studied conditions, ensuring good structural stability, which is in line with pillar design principles under confined conditions.

- (2)

The wall provides a pronounced lateral confinement enhancement effect. As a rigid structure, the wall restricts lateral deformation on the pillar’s free side, increases lateral stress within the pillar, and transforms the stress state into a more confined triaxial compression condition. This substantially raises the pillar’s peak strength, delays plastic zone propagation, and enhances its resistance to failure and overall stiffness, consistent with experimental observations on rock and coal strength under confining pressure.

- (3)

The composite structure has excellent seepage resistance. Seepage simulations demonstrate that the wall effectively prevents high-pressure water in the goaf from penetrating into the pillar and roadway, reducing pore-pressure gradients and saturation levels in the pillar. For wall thicknesses ≥1.0 m, the composite structure forms a distinct low-pressure zone and water-blocking barrier on the wall side, significantly inhibiting the formation of continuous water-conducting channels, similar in function to engineered water-barrier pillars.

- (4)

Anti-sliding tests reveal the critical role of shear loading position and structural reinforcement. Similar-material tests show that when the distance between the shear load application point and the wall–pillar interface is ≥0.8 m, failure predominantly occurs within the coal, and the composite structure exhibits high shear resistance. When the loading point is located close to the interface (≤0.4 m), sliding along the interface is likely to occur, severely weakening cooperative load-bearing. It is therefore recommended that engineering designs adopt measures such as fully grouted rock bolts, cables, and shear keys to enhance interface roughness and mechanical interlocking, thereby improving the anti-sliding capacity and overall stability of the composite structure.

The present study is subject to several limitations that should be considered when applying the findings. The coal–rock mass is modeled as a layered continuum without explicit joints or discrete fractures, which may not capture fracture-dominated seepage behavior. Furthermore, validation is based on a single case study, and generalization to other mining conditions requires further verification. Future work should address these limitations through discrete fracture modeling, dynamic hydro-mechanical coupling, long-term degradation testing, and validation with additional field cases.