A Hybrid Framework of Gradient-Boosted Dendritic Units and Fully Connected Networks for Short-Term Photovoltaic Power Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- An integrated prediction framework (GBMDF) that combines the gradient boosting paradigm and dendritic neural structure is proposed. It gradually captures the nonlinear mapping between residual prediction and environmental variables through iterative error-correction optimization, while comprehensively utilizing multi-source meteorological inputs and maintaining strong interpretability and analytical transparency.

- Based on the flexibility of the GBMDF, the residual differences are offset by exploring the association between the error patterns of alternative predictors and weather attributes. This method is conceptually simple and demonstrates strong practical effectiveness.

- A short-term photovoltaic power prediction infrastructure based on dendritic networks was constructed, replacing the traditional neuron activation function with the Hadamard product operation, so that the model has both transparent white-box characteristics. At the same time, through the synergistic integration of the gradient boosting mechanism and the deep fully connected layer, the prediction accuracy and model robustness were improved, and the applicability of the gradient boosting paradigm in nonlinear energy prediction scenarios was expanded.

2. Theory and Methods

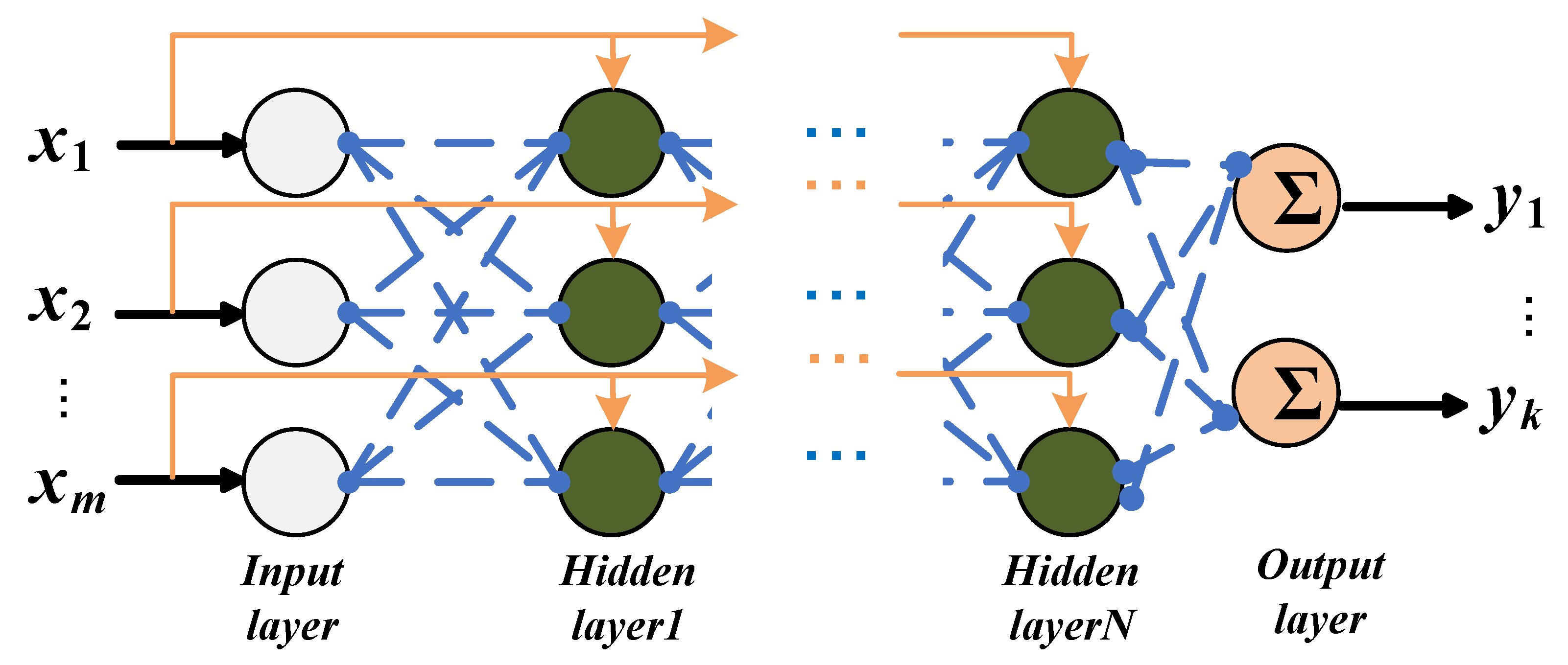

2.1. Dendrite Network

2.2. Gradient Boosting

2.3. Overall Architecture for PV Power Forecast

2.4. Experimental Data

3. Results

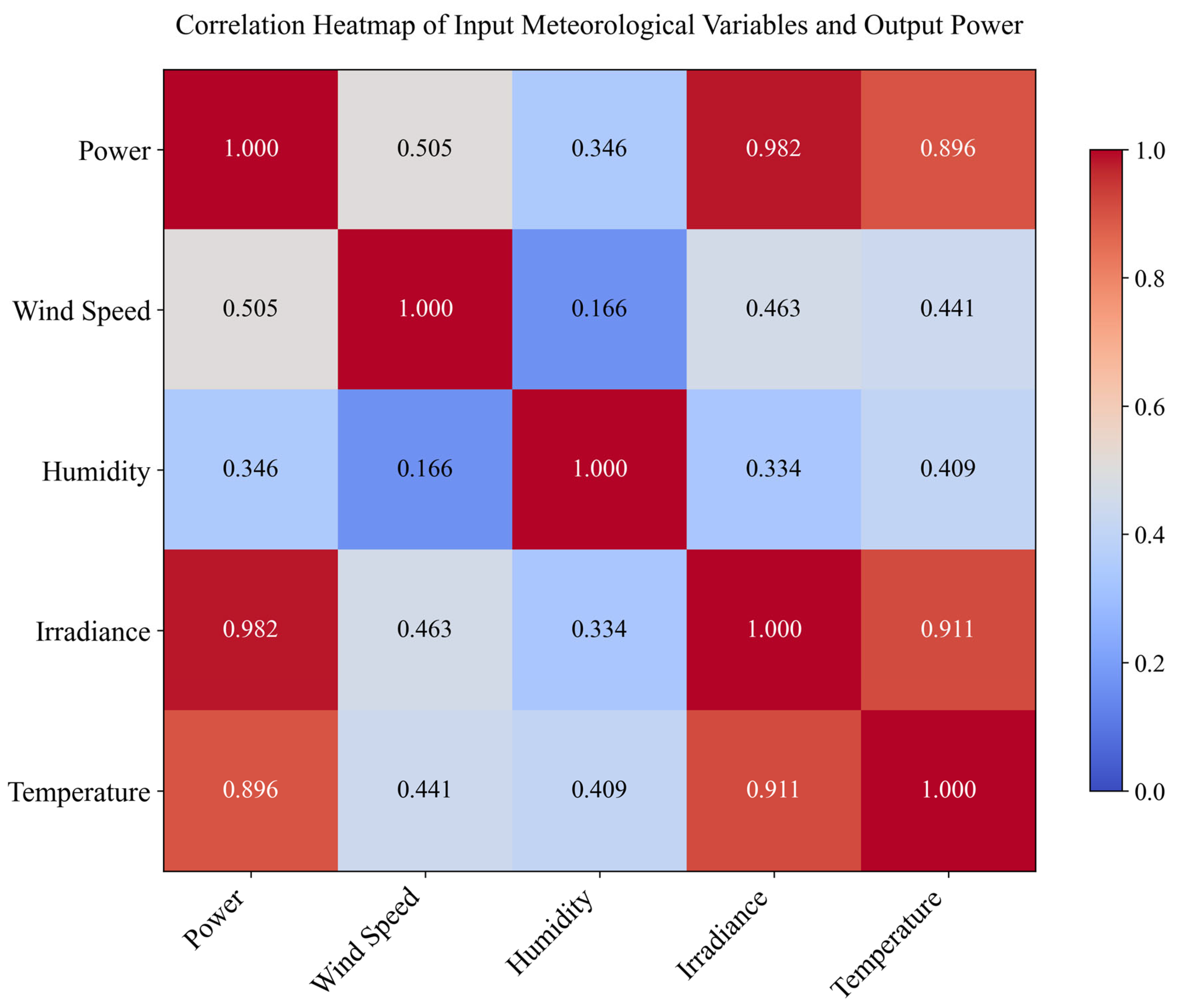

3.1. Feature Analysis

3.2. Experiment

3.3. Model Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khare, V.; Nema, S.; Baredar, P. Solar–wind hybrid renewable energy system: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2021; IEA: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Sobri, S.; Koohi-Kamali, S.; Rahim, N.A. Solar photovoltaic generation forecasting methods: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 156, 459–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Yousaf, A.; Noor, J.; Cao, Y.; Dong, M.; Yang, J.; Rizk-Allah, R.M.; Elkholy, M.H.; Talaat, M. Ann-based model predictive control for hybrid energy storage systems in dc microgrid. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, F.; Wang, C.; Cao, Y.; Hu, Y. Shared-Receiver Battery Equalizer Based on Inductive Power Transfer and Bidirectional DC-DC Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 41, 3879–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, M.; Cao, Y. A novel neural network model with cascaded structure for state-of-charge estimation in lithium-ion batteries. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 99, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- De la Nieta, A.A.S.; Paterakis, N.G.; Gibescu, M. Participation of photovoltaic power producers in short-term electricity markets based on rescheduling and risk-hedging mapping. Appl. Energy 2020, 266, 114741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolara, A.; Leva, S.; Manzolini, G. Comparison of different physical models for PV power output prediction. Sol. Energy 2015, 119, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardakos, E.G.; Alexiadis, M.C.; Vagropoulos, S.I.; Simoglou, C.K.; Biskas, P.N.; Bakirtzis, A.G. Application of time series and artificial neural network models in short-term forecasting of PV power generation. In Proceedings of the 2013 48th International Universities’ Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Dublin, Ireland, 2–5 September 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Peng, Z.; Lai, Y.; Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Wu, L. Short-term power prediction for photovoltaic power plants using a hybrid improved Kmeans-GRA-Elman model based on multivariate meteorological factors and historical power datasets. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C. An improved photovoltaic power forecasting model with the assistance of aerosol index data. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2015, 6, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Bae, K.Y.; Park, H.S.; Sung, D.K. Solar power prediction based on satellite images and support vector machine. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2016, 7, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.J.; Kuo, P.H. Multiple-input deep convolutional neural network model for short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 74822–74834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundu, V.; Simon, S.P. Short term solar power and temperature forecast using recurrent neural networks. Neural Process. Lett. 2021, 53, 4407–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Li, R.; Tao, Z. A novel adaptive discrete grey model with time-varying parameters for long-term photovoltaic power generation forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 227, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, N.; Gong, L.; Jiang, M. Prediction of photovoltaic power output based on similar day analysis, genetic algorithm and extreme learning machine. Energy 2020, 204, 117894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yin, W. Short-term photovoltaic power forecasting method based on irradiance correction and error forecasting. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 5495–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.Q.; Li, L.L.; Tseng, M.L.; Liu, H.M.; Yuan, D.D.; Tan, R.R. An improved moth-flame optimization algorithm for support vector machine prediction of photovoltaic power generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Li, C.; Gao, R.; Huang, Y.; You, H.; Gu, T.; Qin, F. Photovoltaic power forecasting based on a support vector machine with improved ant colony optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lv, C.; Ma, F.; Zhao, K.; Wang, H.; O’Hare, G.M. A photovoltaic power forecasting model based on dendritic neuron networks with the aid of wavelet transform. Neurocomputing 2020, 397, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhou, K.; Lu, X.; Yang, S. A hybrid deep learning model for short-term PV power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, M.K.; Nayak, N. A comparative study on short-term PV power forecasting using decomposition based optimized extreme learning machine algorithm. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2020, 23, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Wang, K.; Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Xu, X. Short-term photovoltaic power generation forecasting based on random forest feature selection and CEEMD: A case study. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 93, 106389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, T.; Jiao, C.; Wang, H.; Hu, W. A multi-step ahead photovoltaic power prediction model based on similar day, enhanced colliding bodies optimization, variational mode decomposition, and deep extreme learning machine. Energy 2021, 224, 120094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, M.; Cao, Y.; Lu, T. Gradient boosting dendritic network for ultra-short-term PV power prediction. Front. Energy 2024, 18, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Wang, C.; Cao, Y.; Chen, H. Photovoltaic power prediction under insufficient historical data based on dendrite network and coupled information analysis. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Photovoltaic power forecasting based on SVM optimized by improved ABC. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Sanya, China, 10–12 January 2020; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 474, p. 052036. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Ling, M.; Chang, H. Distributed solar photovoltaic power prediction algorithm based on deep neural network. J. Eng. Res. 2024, 13, 3352–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Su, Z. Research on Photovoltaic Power Generation Forecasting Based on a Combined CNN-LSTM Neural Network Model. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 7, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswat, R.; Jhanwar, D.; Gupta, M. Enhanced Solar Power Forecasting Using XG Boost and PCA-Based Sky Image Analysis. Trait. Signal 2024, 41, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.H. Predicting Future Promising Technologies Using LSTM. Informatics 2022, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, K.M. LightGBM Medium-Term Photovoltaic Power Prediction Integrating Meteorological Features and Historical Data. Energies 2025, 18, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J. Dendrite net: A white-box module for classification, regression, and system identification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 13774–13787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desert Knowledge Australia Solar Center. Available online: https://dkasolarcentre.com.au/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

| Networks/Paper | Data Scale | Advantage | Limitation | Robustness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM/Liu, L. et al. (2020) [27] | Small | not prone to overfitting. | Not friendly to large-scale data. | better |

| BPNN/Zhao, M. et al. (2024) [28] | Small or medium | easy to implement. | unable to handle spatiotemporal features. | Poor |

| CNN/Qiu, R., & Su, Z. (2024) [29] | Large | Spatial feature extraction and weight sharing. | Ignore long-term timing. | medium |

| XGBoost/Saraswat, R et al. (2024) [30] | Medium to very large | High prediction accuracy; Good at handling missing values. | Requires manual feature engineering. | Good |

| LSTM/Noh, S. H. (2022) [31] | Large | Capturing long-term temporal dependencies. | Weak ability to capture spatial features. | Moderate preference |

| LightGBM/Yang, Y et al. (2025) [32] | Large to very large | Extremely fast training speed and lower memory consumption. | Prone to overfitting on small datasets. | Good, but sensitive on small data |

| Name | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Array Rating | 6.05 kW |

| Panel Rating | 275 W |

| Number of Panels | 22 |

| Panel Type | Q.PLUS BFR-G4.1 275 |

| Array Area | 36.74 m2 |

| Array Tilt/Azimuth | Tilt = 20, Azi = 0 (Solar North) |

| Name | Parameters |

|---|---|

| epoch | 256 |

| 0.05 | |

| Layer number | 8 |

| batch | 2 |

| bias | 1 |

| ve | 0.8 |

| Model | MAPE (%) | MAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| FNN | 10.4371 | 0.1553 | 0.2542 |

| CNN | 7.8323 | 0.0797 | 0.1618 |

| XGBoost | 8.9421 | 0.8543 | 0.1723 |

| DN | 7.2524 | 0.0821 | 0.1688 |

| LightGBM | 6.9427 | 0.0843 | 0.1572 |

| LSTM | 7.1342 | 0.0817 | 0.1621 |

| Informer | 6.1042 | 0.0781 | 0.1371 |

| GBMDF | 6.6429 | 0.0732 | 0.1537 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, K.; Wu, X.; Zheng, K.; Nie, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Sheng, X. A Hybrid Framework of Gradient-Boosted Dendritic Units and Fully Connected Networks for Short-Term Photovoltaic Power Forecasting. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010406

Cai K, Wu X, Zheng K, Nie C, Yang Y, Li Y, Cao Y, Sheng X. A Hybrid Framework of Gradient-Boosted Dendritic Units and Fully Connected Networks for Short-Term Photovoltaic Power Forecasting. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010406

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Kunlun, Xiucheng Wu, Kangliang Zheng, Chufei Nie, Yuantong Yang, Yiqing Li, Yuan Cao, and Xilong Sheng. 2026. "A Hybrid Framework of Gradient-Boosted Dendritic Units and Fully Connected Networks for Short-Term Photovoltaic Power Forecasting" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010406

APA StyleCai, K., Wu, X., Zheng, K., Nie, C., Yang, Y., Li, Y., Cao, Y., & Sheng, X. (2026). A Hybrid Framework of Gradient-Boosted Dendritic Units and Fully Connected Networks for Short-Term Photovoltaic Power Forecasting. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010406