1. Introduction

In the era of digital transformation, organizations in all industries are inundated with vast amounts of unstructured information, from technical manuals, regulatory policies, and customer support transcripts to internal wikis and multimedia logs [

1,

2,

3]. Businesses, especially in finance and healthcare, must organize, retrieve, and integrate knowledge to comply with regulations, accelerate innovation, and improve customer satisfaction [

4,

5,

6]. However, traditional knowledge management systems, which rely on keyword searches or manual categorization, struggle to handle rapidly evolving data or complex queries, as observed in legacy corporate archives [

1,

7,

8]. Currently, document automation workflows, including contract generation, report writing, and policy alignment, are hampered by labor-intensive processes, error risks, and reliance on rigid templates [

9,

10,

11].

Recent advances in LLMs, such as GPT, PaLM, and LLaMA, and open-source counterparts, such as OPT, GPT-NeoX, and BLOOM, have improved natural language understanding and generation, evidenced by their performance on benchmark tasks since 2020 [

6,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These models excel in generating coherent text, answering queries, summarizing documents, and producing code, but their reliance on fixed training data limits the precision of niche or dynamic topics, often leading to hallucinations [

17,

18]. The Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) approach addresses this limitation by integrating real-time knowledge retrieval with LLM generation, anchoring outputs in current domain-specific data [

1,

2,

19,

20]. This approach minimizes factual errors and improves accuracy, enabling LLM applications in enterprise tasks such as reviewing legal documents, monitoring regulatory compliance, financial analytics, and automation of technical support, based on initial case studies [

10,

21,

22].

Despite the potential of RAG + LLM integration, the current literature lacks detailed frameworks for their application in enterprise knowledge management and document automation, particularly in terms of scalability [

3,

9,

23]. Critical research questions arise, such as which retrieval indexes, vector databases, or knowledge graph representations are most effective for diverse types of documents, such as contracts or policies [

18,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. How are LLMs fine-tuned or prompted to integrate retrieved contexts without sacrificing fluency [

23,

29,

30]? What evaluation metrics and validation strategies reliably capture generative quality, latency, and factual correctness [

17,

31,

32]? This review assesses enterprise scenarios, including contract generation, policy compliance, and customer self-service, to evaluate successful RAG + LLM deployments and identify persistent challenges such as real-time integration and scalability [

32,

33,

34].

To address these gaps, a comprehensive systematic literature review (SLR) of RAG + LLM research was conducted in the context of enterprise knowledge management and document automation, covering publications from 2015 through mid-2025, with supplemental 2025 insights [

1,

2,

35]. For this review, six major academic databases were searched: IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar [

35]. The scope of the review was expanded to include both journal articles and conference proceedings. These RQs guided the analysis of 63 studies, detailed in

Section 3, structuring the inquiry into platforms, datasets, ML types, specific RAG + LLM algorithms, evaluation metrics, validation techniques, knowledge representation methods, best-performing configurations, and open challenges. After retrieving more than 500 candidate papers, exclusion criteria were applied to non-English works, abstracts without full text, non-empirical studies, and papers lacking detailed RAG + LLM methodology; a rigorous quality assessment then reduced the pool to 63 high-quality papers [

35]. Data were extracted and synthesized on each study’s technical approach, datasets, performance metrics, validation strategy, and reported challenges [

35].

The analysis reveals several notable trends. First, enterprise RAG + LLM research has grown dramatically since 2020, with a nearly equal split between journal articles and conference venues [

1,

2]. Second, supervised learning remains the dominant paradigm, although emerging work in semi-supervised and unsupervised retrieval shows promise for scenarios with limited labeled data [

7,

36,

37]. Third, hybrid architectures combining dense vector retrieval, symbolic knowledge graphs, and prompt LLM tuning are increasingly adopted to balance accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency [

18,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

38,

39,

40]. Fourth, evaluation practices remain heterogeneous: while standard metrics include precision and recall for QA tasks, few studies incorporate end-to-end measures of business impact [

7,

17,

31]. Finally, based on our analysis of enterprise case studies, a key challenge lies in maintaining data privacy when integrating LLMs with proprietary corpora—particularly in regulated sectors—while optimizing latency for real-time applications and developing robust methods to detect and mitigate hallucinations [

32,

33,

34,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Based on these insights, we outline the best practice recommendations for deployers: modular system design, continuous index updating, efficient nearest neighbor search, federated device retrieval, and hybrid evaluation frameworks that combine automated metrics with human feedback [

24,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Open research directions are also identified, such as multimodal RAG architectures integrating text, image, and tabular data [

49,

50,

51]; adaptive retrieval strategies that personalize context based on user profiles [

52,

53]; and benchmark suites that measure real-world business outcomes [

17]. This SLR offers a structured, data-driven overview of RAG + LLM for enterprise knowledge management and document automation, charting the evolution of methods, standard practices, and critical gaps. By synthesizing findings from the literature, a roadmap is defined to guide future research and innovation at the intersection of retrieval, generation, and enterprise scale AI [

3].

3. Research Methodology

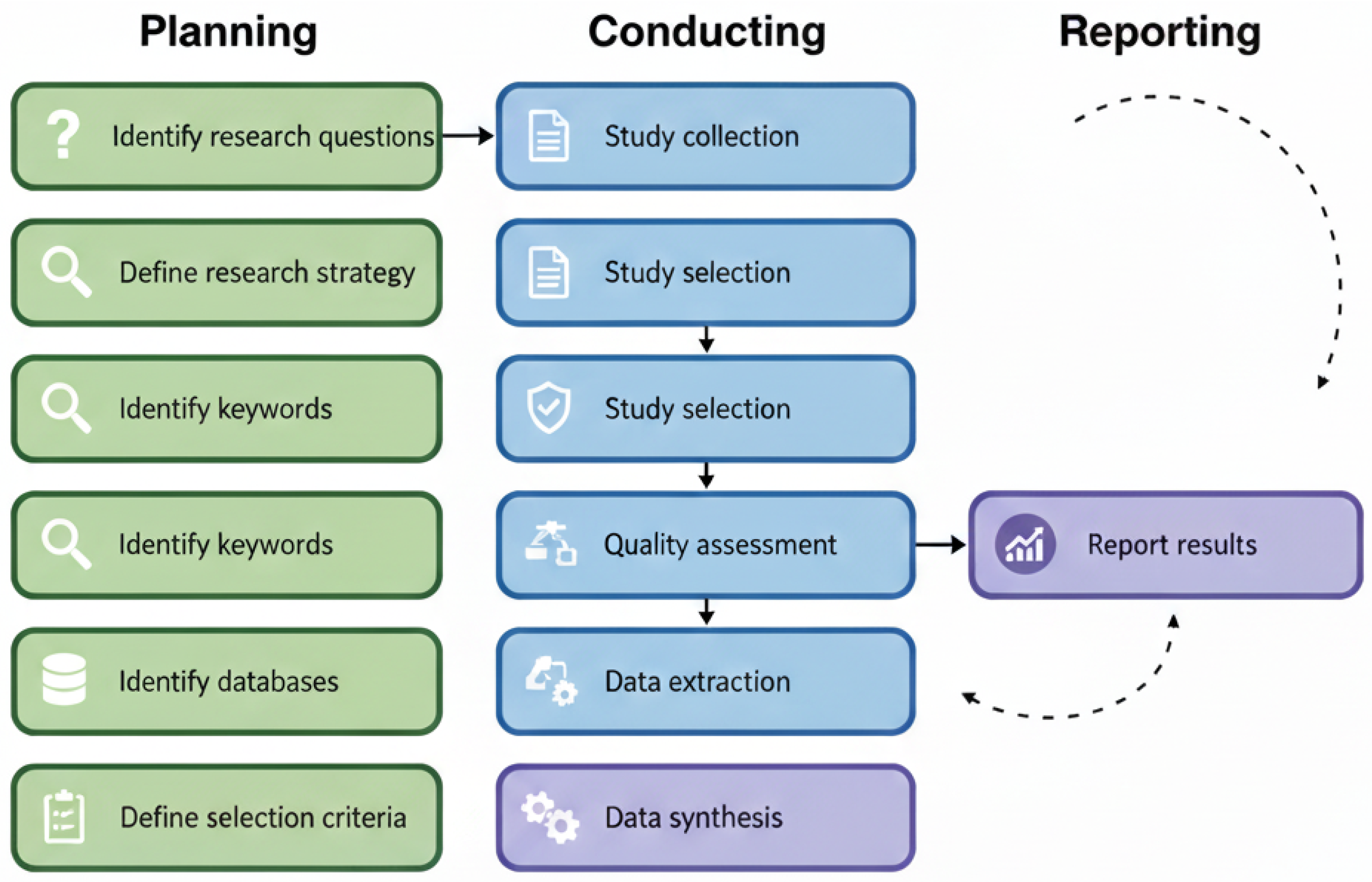

In this section, the systematic review methodology (SLR) was used to provide a rigorous and reproducible investigation of recovered Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Large Language Models (LLMs) in the context of enterprise knowledge management and document automation [

19,

57,

58]. This method involves three main stages: planning, conducting and reporting the review [

58]. Each stage incorporates specific protocols designed to minimize bias and improve transparency throughout the research process [

58].

During the planning phase, nine specific research questions were formulated to guide this investigation and address issues such as data sources, algorithmic approaches, evaluation criteria, and practical challenges [

19,

58]. The questions were then translated into precise Boolean search strings (

Figure 1). Six major academic databases were selected (

IEEE Xplore,

ACM Digital Library,

SpringerLink,

ScienceDirect,

Wiley Online Library, and

Google Scholar) to capture a comprehensive body of relevant studies published between 2015 and 2025 [

19,

26]. Explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to effectively filter the results [

58].

By exclusively selecting peer-reviewed English language studies with empirical results and detailed descriptions of the RAG + LLM method, a transparent and reproducible process was established that ensured the reliability of subsequent synthesis and analysis [

57,

58].

The research questions (RQs) addressed are as follows:

- RQ1:

Which platforms are addressed in enterprise RAG + LLM studies for knowledge management and document automation?

- RQ2:

Which datasets are used in these RAG + LLM studies?

- RQ3:

Which types of machine learning (supervised, unsupervised, etc.) are employed?

- RQ4:

Which specific RAG architectures and LLM algorithms are applied?

- RQ5:

Which evaluation metrics are used to assess model performance?

- RQ6:

Which validation approaches (cross-validation, hold-out, case studies) are adopted?

- RQ7:

What knowledge and software metrics are utilized?

- RQ8:

Which RAG + LLM configurations achieve the best performance for enterprise applications?

- RQ9:

What are the main practical challenges, limitations, and research gaps in applying RAG + LLMs in this domain?

The goal was to find studies exploring the application of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Large Language Models in the context of enterprise knowledge management and document automation [

1,

9]. A search was carried out on several academic databases (

Table 4), including

IEEE Xplore,

ScienceDirect,

ACM Digital Library,

Wiley Online Library,

SpringerLink, and

Google Scholar between 2015 and 2025 [

35]. The searches were finalized on 15 June 2025, which serves as the cutoff date for this review. To eliminate irrelevant results, a set of exclusion criteria was applied (see

Section 3), such as excluding non-English articles, abstract-only entries, non-empirical studies, and works that lacked a detailed explanation of RAG or LLM methodologies [

35]. The Boolean search string used in all databases was as follows:

((“Retrieval Augmented Generation” OR RAG) AND (“Large Language Model” OR LLM) AND (“Knowledge Management” OR “Document Automation” OR Enterprise))

Figure 2 presents the number of records retrieved from each database in three major stages of the selection process: initial retrieval, after applying exclusion criteria, and after quality assessment.

Exclusion Criteria:

- E1.

The paper includes only an abstract (we required full text, peer-reviewed articles).

- E2.

The paper is not written in English.

- E3.

The article is not a primary study.

- E4.

The content does not provide any experimental or evaluation results.

- E5.

The study does not describe how Retrieval-Augmented Generation or LLM methods work.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the 63 selected primary studies (

Table 5) in academic databases. Due to the rapid pace of innovation in Generative AI and RAG architectures, the majority of high-impact studies (55 papers) were retrieved via Google Scholar, which indexes preprints (arXiv) and top-tier computer science conferences (NeurIPS, ACL, ICLR) that are often published faster than traditional journals. Specialized databases such as IEEE Xplore (8) and ACM Digital Library (5) contributed foundational studies on information retrieval and software engineering aspects.

Once the exclusion criteria were enforced, the remaining articles were subjected to the eight-question quality assessment. Any paper scoring less than 10 out of 16 was removed.

Figure 3 shows the resulting distribution of quality scores (11–16), where each “yes” earned 2 points, “partial” earned 1 point, and “no” earned 0 points [

35].

Quality Evaluation Questions:

- Q1.

Are the aims of the study declared?

- Q2.

Are the scope and context of the study clearly defined?

- Q3.

Is the proposed solution (RAG + LLM method) clearly explained and validated by an empirical evaluation?

- Q4.

Are the variables (datasets, metrics, parameters) used in the study likely valid and reliable?

- Q5.

Is the research process (data collection, model building, analysis) documented adequately?

- Q6.

Does the study answer all research questions (RQ1–RQ9)?

- Q7.

Are negative or null findings (limitations, failures) transparently reported?

- Q8.

Are the main findings stated clearly in terms of credibility, validity, and reliability?

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal distribution of the selected studies, showing a sharp increase in RAG + LLM research since 2020.

Figure 5 shows that the selected publications are slightly favoring conference proceedings (58.4%) over journal articles (41.6%), which is typical for a fast-moving field like RAG. This suggests that, while conferences remain important for rapid dissemination, a substantial portion of the evidence base appears in peer-reviewed journals.

Data Extraction and Quality Assurance

To ensure the reliability of the quantitative analysis, a dual-coding procedure was employed. Both authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the initial candidates. For the final corpus of 63 primary studies, data extraction was performed using a standardized form capturing the following: (1) Deployment Platform, (2) Dataset Type, (3) RAG Architecture, and (4) Evaluation Metrics (see

Table S1 in Supplementary Materials for the complete data extraction form). Discrepancies in classification (e.g., whether a study was “Cloud-native” or “Hybrid”) were resolved through consensus meetings. Foundational papers describing generic model architectures (e.g., BERT, Transformer) were treated as background literature and excluded from the statistical analysis of primary RAG applications.

5. Discussion

In this section, answers to the nine research questions (RQ1–RQ9) are synthesized, the maturity and limitations of the current body of work are assessed, and a roadmap is outlined for moving RAG + LLM from academic prototypes to robust, production-ready enterprise systems. Across the reviewed studies, a practical guideline emerges: use

sequence-level retrieval for generative reasoning in open ended tasks, and employ

token-level methods for narrowly scoped extractive tasks (e.g., field lookup). The predominance of conference papers in recent years (2023–2024) aligns with the fast-moving nature of LLM and RAG research, where top venues such as NeurIPS, ICLR, and ACL serve as the primary dissemination channels. This aligns with the empirical comparison of RAG Sequence vs. RAG Token [

31] and with hybrid retrieval findings where dense vectors are complemented by knowledge graphs for structured contexts [

25,

27,

28].

The findings are summarized across tables and figures. To deepen interpretability in future reviews, advanced visualizations can further surface structure in the evidence. For instance, a Sankey diagram connecting core RAG components (data source, retrieval agent, LLM type) would reveal dominant architectural flows. Likewise, a relationship matrix heatmap between RQs and the algorithms or metrics used would highlight at a glance which areas are well-studied and where gaps persist. Finally, the publication trend in

Figure 4 could be annotated with event markers (e.g., major model releases) to contextualize inflection points [

1,

2,

3].

While we report aggregate findings like 30–50% reductions in manual editing time, these figures represent ranges observed primarily in the real world case studies (13% of the corpus) and are not meta-analytic confidence intervals. Representative examples include banking support and policy summarization deployments [

17,

58]. Future field trials should aim for standardized reporting that includes statistical variance to enhance comparability across enterprise deployments.

5.1. Synthesis of Key Findings

Most RAG + LLM research targets

cloud-native infrastructures (66.2%), while 33.8% explore on-premises, edge, or hybrid deployments (

Table 6). This reflects a trade-off between elasticity and control. On-device edge studies demonstrate low-latency, offline operation [

48], whereas privacy-preserving on-premises or federated settings address sovereignty and compliance [

42,

43,

47]. Hybrid topologies, though still limited (3.9%), foreshadow distributed RAG that partitions retrieval and generation across trust boundaries. Over half of the studies (54.5%) rely on public GitHub data; 15.6% use proprietary corpora, and 16.9% construct custom industrial datasets (

Table 7). Public sources aid reproducibility but risk domain shift. Bridging the public–private gap requires domain adaptation and continual updating [

45,

46], as well as privacy-preserving retrieval over sensitive stores [

42,

47].

Supervised learning dominates (92.2%). Unsupervised (3.9%) and semi-supervised (3.9%) remain underused, pointing to opportunities in contrastive embedding learning and self-few-shot and zero-shot adaptation for label-scarce domains [

29,

36,

37]. Classical learners (Naïve Bayes, SVM, Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Random Forest) remain staples for ranking and defect classification, while Transformer-based RAG variants gain ground. Hybrid indexing that combines dense vectors and knowledge graphs appears in 23.1% of studies and often boosts explainability and precision [

3,

25,

26]. The RAG Sequence vs. RAG Token contrast is documented in [

31].

Technical metrics (precision recall accuracy: 80.5%; Recall@K Precision@K: 72.7%; ROUGE BLEU: 44.2%) dominate (

Table 10). Human studies are reported in 19.5%, and business impact metrics in only 15.6% [

17,

31,

32]. This gap underscores the need to pair automated scores with user studies and operational KPIs.

k-fold cross-validation (93.6%) is standard, but may overestimate performance under non IID drift. Hold-out Splits (26%) and real-world case study field trials (13%) are crucial for deployment readiness and impact measurement. Object oriented code metrics are most common; web process performance metrics remain rare. As pipelines integrate retrieval, generation, and interaction, richer telemetry (latency distributions, provenance coverage, and user satisfaction) is needed.

Top results frequently pair RAG Token with fine-tuned encoder–decoder LLMs or use hybrid dense + KG retrieval feeding seq2seq models; zero-shot prompting of large decoder-only LLMs is competitive for generative tasks, but fine-tuning typically adds 10–20% factuality gains [

31,

58,

94]. Five recurring challenges emerge: privacy (37.7%), latency (31.2%), business impact evaluation (15.6%), hallucination control (48.1%), and domain adaptation (23.4%) (

Table 13). Privacy-preserving and federated retrieval with differential privacy or SMPC are active directions [

41,

42,

43,

47]; latency can be reduced by ANN search, model compression, and asynchronous retrieval [

32,

33,

48,

102]; hallucinations call for provenance graphs and causal explainable methods [

13,

34,

44,

101]; domain shift motivates continual RAG and incremental indexing [

45,

46]. Multimodal and multilingual enterprise settings remain nascent [

49,

50,

51,

72,

103].

5.2. Critical Analysis of Enterprise Constraints: The Lab-to-Market Gap

Our analysis reveals a distinct divergence between academic RAG research and enterprise requirements. While academic studies often prioritize leaderboard metrics (e.g., Recall@K on MS MARCO) [

17,

65], enterprise deployments face strictly operational constraints that are rarely simulated in benchmarks:

Latency vs. Accuracy Trade-off: Academic models often employ computationally expensive re-ranking steps (e.g., BERT-based cross-encoders) to maximize precision. However, in enterprise real-time document automation, the latency budget is often under 200 ms, forcing a reliance on lighter, less accurate bi-encoders or hybrid sparse-dense retrieval methods [

32,

33,

48].

Auditability and Traceability: Regulated industries (Finance, Healthcare) require determinism. End-to-end neural approaches (black-box RAG) are often rejected in favor of modular pipelines where the retrieved context can be manually audited before generation. This contrasts with the trend towards “end-to-end trained” RAG in recent academic literature [

25,

26].

Catastrophic Hallucination Risk: Unlike general QA, a hallucination in a generated contract or medical report carries legal liability. This necessitates “Strict RAG” configurations where the model is constrained to output “I don’t know” if the retrieval score is below a high confidence threshold—a behavior rarely optimized in standard academic benchmarks like TruthfulQA [

34,

44,

96].

5.3. Practical Implications for Enterprise Adoption

Organizations aiming to deploy Retrieval-Augmented Generation and Large Language Model solutions will benefit from a hybrid infrastructure that uses cloud platforms for large-scale, low-sensitivity workloads; on-premises indexing to protect confidential data; and edge inference to deliver rapid, low-latency responses, with intelligent routing based on data sensitivity and response time requirements [

32,

33,

47,

48,

102].

To ensure regulatory compliance under frameworks like GDPR, CCPA, and HIPAA, privacy-preserving retrieval mechanisms such as encrypted embeddings, access-controlled vector stores, or federated retrieval should be adopted [

41,

42,

43,

47]. The scarcity of labeled data in niche domains can be addressed through semi-supervised and unsupervised methods like contrastive embedding learning, self training, and prompt-based few-shot adaptation [

29,

36,

37].

A comprehensive evaluation setup integrates quantitative metrics such as Recall, ROUGE, and BLEU with human in the loop evaluations and business KPIs (e.g., shortened manual workflows, fewer errors, higher user satisfaction) to assess technical performance and strategic impact [

16,

17,

31,

32]. To keep models current, establish continuous learning workflows that routinely refresh retrieval indices, fine tune on newly ingested data, and actively monitor and mitigate concept drift [

45,

46,

93]. Additionally, integrating structured knowledge graphs alongside dense retrieval ensures that domain specific ontologies, regulatory frameworks, and business rules are captured, boosting accuracy and real-world effectiveness [

18,

25,

26,

27,

28].

5.4. Limitations of This Review

While this systematic literature review (SLR) adheres to a rigorous methodology involving exhaustive database searches and stringent quality assessments, several intrinsic limitations must be acknowledged.

Firstly, a scope bias is present due to the exclusion of gray literature. The review was strictly limited to peer-reviewed academic articles to ensure scientific rigor. However, in the rapidly evolving field of Generative AI, significant operational data and novel architectural patterns are often first released in industry white papers, vendor technical reports, and non-peer-reviewed preprints, which were excluded from this analysis unless indexed in the selected academic databases.

Secondly, limitations related to the corpus and publication bias are recognized. Studies reporting positive outcomes or successful deployments are more likely to be published than those detailing failures or negative results, potentially overstating the realized benefits and reliability of RAG + LLM solutions in enterprise settings. Additionally, the predominance of English language studies introduces a language bias, leaving the specific challenges of multilingual enterprise deployments underrepresented.

Thirdly, the temporal constraints and the rapid pace of the field present a challenge. Although the search window spans 2015–2025, the majority of relevant RAG literature emerged post-2020. Consequently, innovations appearing during the final stages of this review process may be absent. Furthermore, metric heterogeneity across studies—specifically the lack of standardized reporting for latency and business ROI—precluded a direct quantitative meta-analysis.

Finally, this review did not analyze the geographic distribution of the primary studies. Future bibliometric analyses could address this gap to provide insights into global R&D trends and regional adoption maturity.

5.5. Future Research Directions

Several research avenues warrant prioritization to foster the advancement of RAG + LLM in enterprise contexts:

Secure Indexing: Developing end-to-end encrypted retrieval pipelines and differential privacy-aware embedding methods is imperative to enable secure indexing of proprietary corpora [

41,

42,

43,

47].

Ultra Low Latency RAG: Research on techniques such as approximate retrieval, model quantization, and asynchronous generation is needed to achieve sub-100 ms response times [

24,

32,

33,

67,

102].

Multimodal Integration: Expanding retrieval and generation to incorporate multimodal data, including images, diagrams, and tabular data commonly found in technical manuals and financial reports, is essential [

49,

50,

51].

Multilingual Support: To truly support a global environment, it is essential to create RAG + LLM systems that process non-English information and transfer knowledge across languages [

72,

103].

Standardized Benchmarks: Setting up business benchmarks that blend technical performance with real-world operations, user feedback, and compliance requirements is vital [

17].

Explainability and Trust: Investigating features like causal attribution, provenance graphs, and interactive explanation interfaces to boost user confidence and make auditing easier is crucial [

13,

26,

101].

Domain Adaptation, Privacy, and Robustness: Recent advances address key RAG challenges including domain adaptation techniques for improved generalization across enterprise contexts [

104], privacy-aware architectures that explore security issues in retrieval-augmented systems [

105], and self-supervised hallucination detection methods that enable zero-resource verification of generated outputs [

106]. These complementary approaches collectively enhance RAG reliability and trustworthiness in production environments.

A thorough review of 63 studies shows that RAG + LLM systems could revolutionize how businesses manage information and automate documents [

1,

2,

3]. However, researchers must work together across different fields to achieve this and rigorously test systems in real-world scenarios [

16,

17,

102].

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This systematic literature review, based on 63 rigorously quality-assessed studies, synthesized the state of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Large Language Models (LLMs) in enterprise knowledge management and document automation. Among the nine research questions, several clear patterns emerged.

The native cloud is dominant (66.2%), while the remainder (33.8% combined) explore on-premises, edge, or hybrid deployments to satisfy sovereignty, latency, and compliance constraints. Representative efforts span cloud middleware and federated settings to edge pipelines on devices [

42,

43,

47,

48,

75]. Studies commonly rely on public GitHub data (54.5%), while proprietary repositories (15.9%) and custom industrial corpora (17.4%) are less frequent, underscoring the need for privacy-preserving retrieval and domain adaptation to bridge public–private gaps [

42,

45,

46,

47,

95]. Supervised learning is the norm (92.1%), with limited use of unsupervised (4.8%) and semi-supervised (3.2%) methods, pointing to opportunities in contrastive self-training and few/zero-shot transfer [

29,

36,

37]. Architecturally, the RAG Sequence is reported in 36 studies and the RAG Token in 28 studies; hybrid dense + KG designs appear in 18 studies. Comparative evidence and hybrid benefits are documented in [

3,

25,

26,

27,

28,

31].

Evaluation skews toward technical metrics (precision, recall, accuracy; Recall@K, Precision@K; ROUGE, BLEU), with relatively scarce human evaluation (19.0%) and measurement of business impact (15.9%) [

17,

31,

32]. Validation of retrieval components is heavily based on k-fold cross-validation (93.6%), whereas end-to-end generative performance is typically assessed via hold-out sets. Field trials in the real world remain limited (12.7%), despite their importance to demonstrate production readiness and ROI [

17].

Recurring issues include hallucination and factual consistency (47.6%) [

34,

44,

101], data privacy (38.1%) [

42,

43,

47], latency and scalability (31.7%) [

32,

33,

48], limited business impact evaluation (15.9%) [

17], and domain adaptation transfer (23.8%) [

45,

95]. In general, RAG + LLM mitigates stale knowledge and reduces hallucinations through retrieval grounding, but substantial work remains to meet enterprise requirements around privacy, latency, compliance, and measurable value.

To bridge the gap between promising prototypes and robust, production-ready systems, we outline six priority directions:

Security and Privacy: Develop end-to-end encrypted federated retrieval and differential privacy embeddings for proprietary corpora; harden access-controlled vector stores and SMPC-based pipelines [

42,

43,

47].

Latency Optimization: Achieve <100 ms E2E latency via faster ANN search, model quantization/distillation, and asynchronous retrieval–generation coupling; report full-latency distributions under load [

32,

33,

48].

Advanced Learning Strategies: Advance semi-supervised strategies (contrastive representation learning, self-training) and prompt-based few/zero-shot adaptation for label-scarce domains [

29,

36,

37].

Holistic Evaluation: Pair automated scores with human studies and operational KPIs (cycle time, error rate, satisfaction, compliance); contribute to shared benchmarks that foreground business impact [

17].

Multimodal & Multilingual Capabilities: Extend retrieval and generation beyond text to images, figures, and tables; strengthen multilingual compliance and cross-lingual transfer for global enterprises, leveraging multilingual open-source foundations like BLOOM [

49,

50,

51,

72,

103].

Continual Maintenance: Implement continual index/model updating to handle concept drift; explore incremental, cost-effective fine-tuning, and lifecycle governance for evolving corpora [

45,

46].

In sum, RAG + LLM offers a powerful paradigm for enterprise knowledge workflows and document automation. Realizing its full potential will require security-by-design retrieval, latency-aware systems, data-efficient adaptation, holistic measurement of business value, multimodal/multilingual capability, and disciplined continual learning—validated through rigorous field trials at scale.