Optimal Cell Segmentation and Counting Strategy for Embedding in Low-Power AIoT Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Optimization of Cell Segmentation: This study presents a performance optimization strategy for cell segmentation by evaluating various data augmentation techniques, segmentation backbones, and loss functions. The proposed approach enhances segmentation performance in terms of accuracy, Dice coefficient, sensitivity, and mIoU.

- Optimization of the End-to-End CSC Pipeline: To improve the accuracy of the CSC pipeline, multiple segmentation models and distance transform-based watershed threshold configurations were compared. Through this analysis, the optimal combination of segmentation and counting techniques for the CSC E2E pipeline was derived.

- Model Lightening and AIoT Deployment Optimization: A model lightening methodology was proposed to enable efficient deployment on low-power AIoT devices. This includes strategies for balancing accuracy, latency, and model size to achieve optimal performance under hardware-constrained environments.

2. Related Works

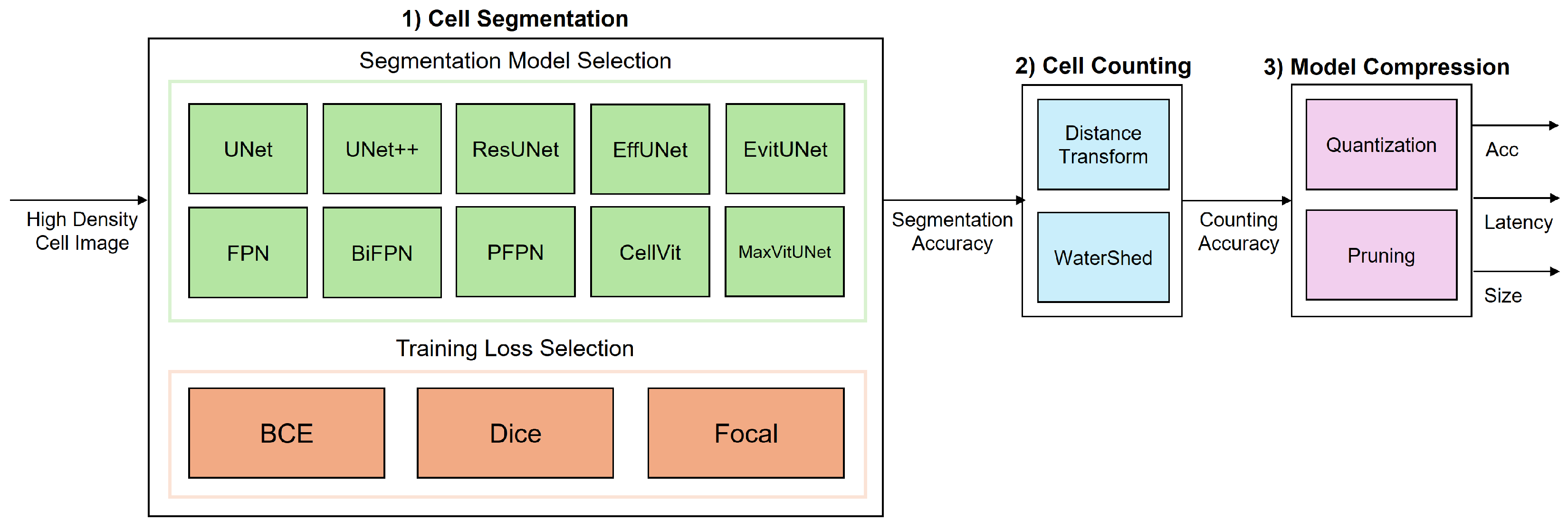

3. System Model

3.1. Cell Segmentation

3.1.1. Segmentation Model Selection

3.1.2. Training Loss Selection

3.2. Cell Counting

Distance Transform-Based Watershed

3.3. Model Compression

3.3.1. FP16 Quantization

3.3.2. INT8 Quantization

3.3.3. Structured Pruning

4. Experimental Results

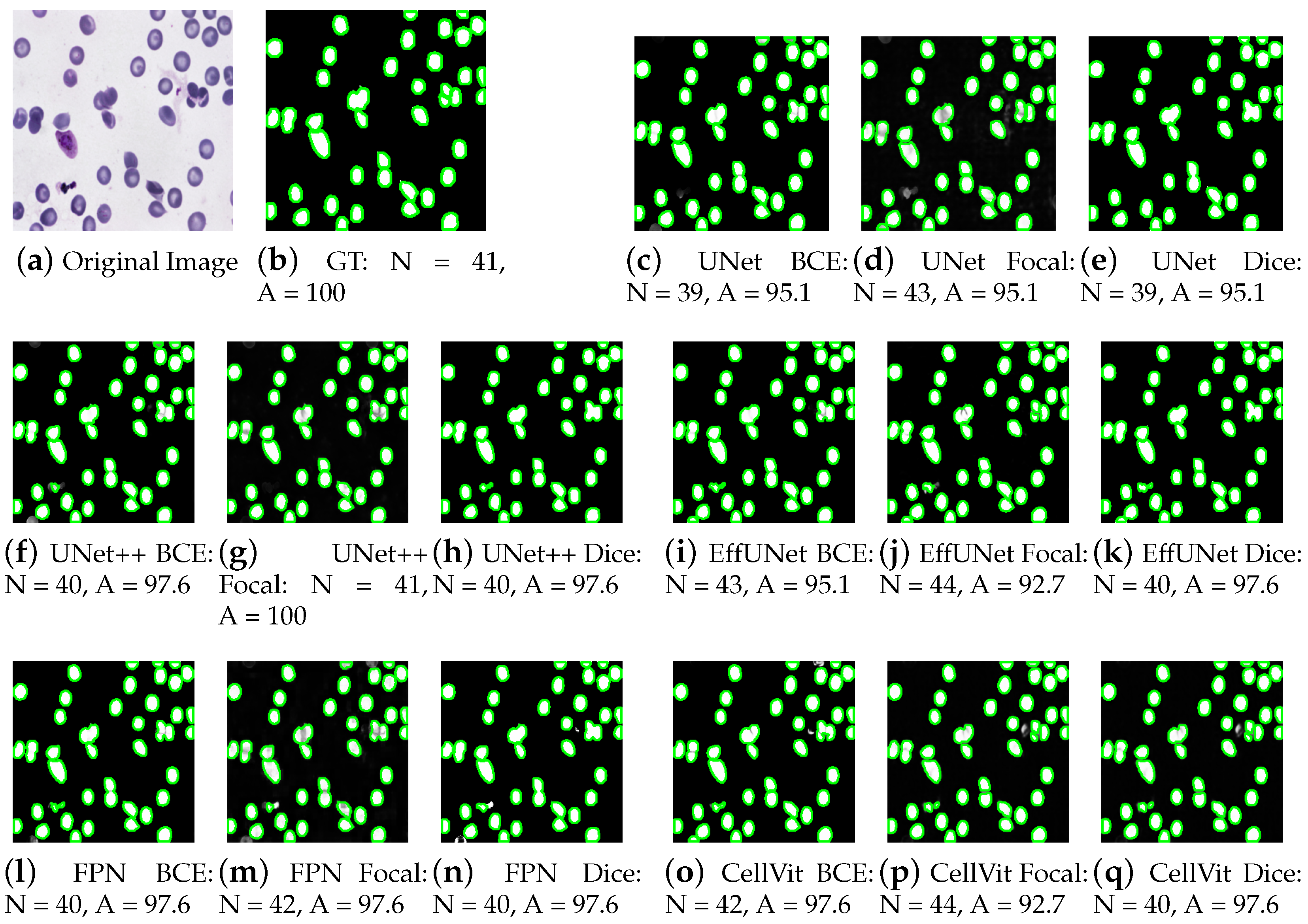

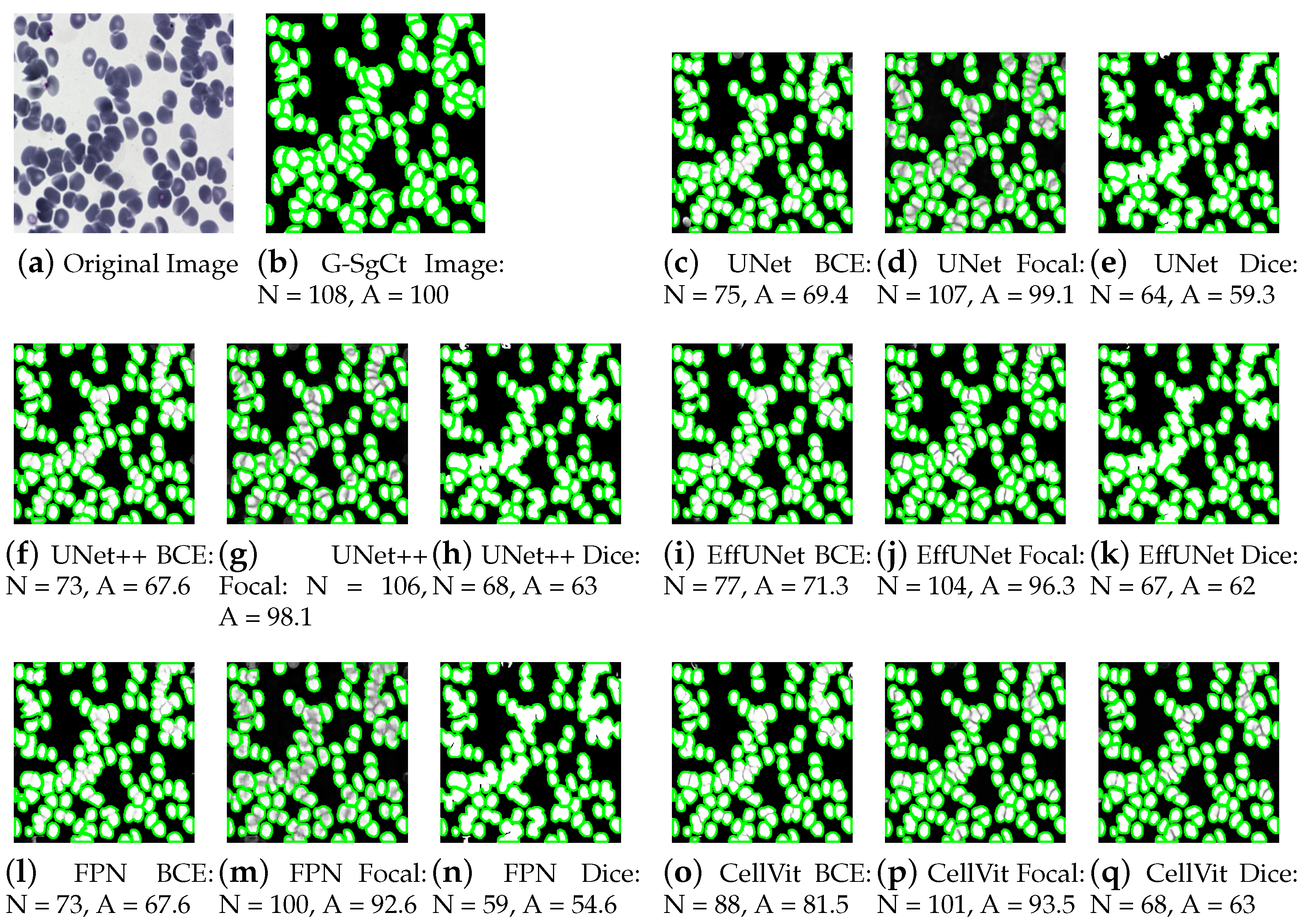

4.1. Performance Analysis of Cell Segmentation

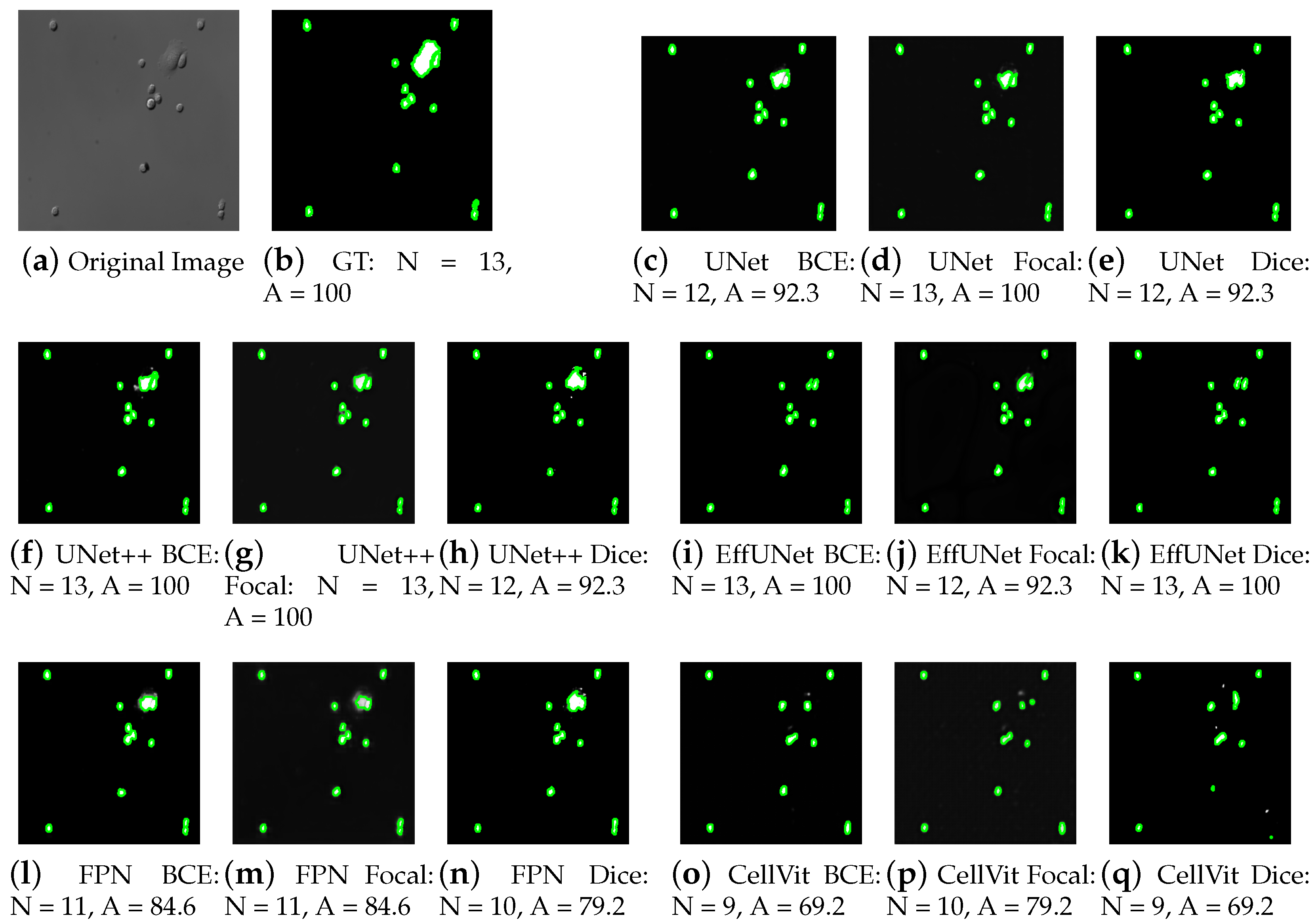

4.2. Performance Analysis of Cell Counting

4.3. Performance Analysis of Model Compression

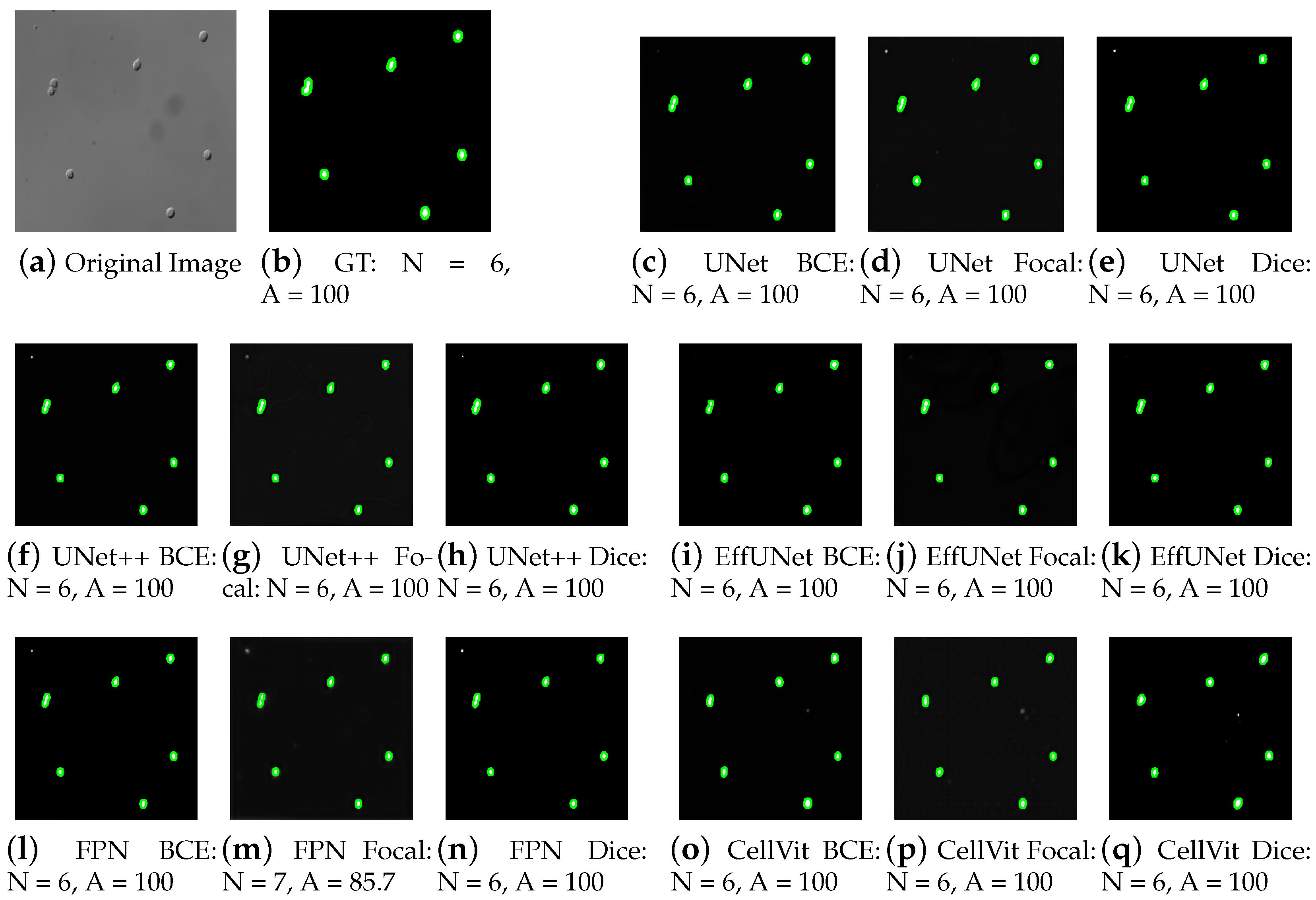

4.4. Cross-Dataset Validation on CHO Cell Images

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kobara, Y.M.; Akpan, I.J.; Nam, A.D.; AlMukthar, F.H.; Peter, M. Artificial intelligence and data science methods for automatic detection of white blood cells in images. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naouali, S.; Othmani, O.E. AI-driven automated blood cell anomaly detection: Enhancing diagnostics and telehealth in hematology. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abozeid, A.; Alrashdi, I.; Krushnasamy, V.S.; Gudla, C.; Ulmas, Z.; Nimma, D.; El-Ebiary, Y.A.B.; Abdulhadi, R. White blood cells detection using deep learning in healthcare applications. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 124, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, S.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H. Automatic recognition of five types of white blood cells in peripheral blood. Cytom. Part A 2011, 79A, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmy, T.; Sreejith, V. A Review on White Blood Cells Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advancements and Effectual Researches in Engineering Science and Technology (RAEREST), Kerala State, India, 20–21 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Farag, M.; Ghazal, H. Automatic white blood cell segmentation using deep learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 180449–180458. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Luo, F.; Li, S. AI-assisted digital hematology for remote blood cell analysis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 678913. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, H.E.; Wheeler, R.T.; Lakowicz, J.R. Quantitative analysis of leukocyte morphology and viability for drug toxicity testing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 2234–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Proceedings of the MICCAI 2015; Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015, Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.10165. [Google Scholar]

- Diakogiannis, F.I.; Waldner, F.; Caccetta, P.; Wu, C. ResUNet-a: A deep learning framework for semantic segmentation of remotely sensed data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.00592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1612.03144. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2020), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Panoptic Feature Pyramid Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.02446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Hörst, F.; Rempe, M.; Heine, L.; Seibold, C.; Keyl, J.; Baldini, G.; Ugurel, S.; Siveke, J.; Grünwald, B.; Egger, J.; et al. CellViT: Vision Transformers for Precise Cell Segmentation and Classification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.15350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Dong, X.; Dumitrascu, O.M.; Wang, Y. EViT-Unet: U-Net Like Efficient Vision Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation on Mobile and Edge Devices. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2410.15036. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.R.; Khan, A. Multi-axis vision transformer for medical image segmentation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 158, 111251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depto, D.S.; Rahman, S.; Hosen, M.M.; Akter, M.S.; Reme, T.R.; Rahman, A.; Zunair, H.; Rahman, M.S.; Mahdy, M.R.C. Automatic segmentation of blood cells from microscopic slides: A comparative analysis. Tissue Cell 2021, 73, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, I.M.; Chachoo, M.A. A hybrid cell image segmentation method based on the multilevel improvement of data. Tissue Cell 2023, 84, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Vu, Q.D.; Raza, S.E.A.; Azam, A.; Tsang, Y.W.; Kwak, J.T.; Rajpoot, N. Hover-Net: Simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 58, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, N.; Umer, F.; Malik, S. Implementation of transfer learning for the segmentation of human mesenchymal stem cells—A validation study. Tissue Cell 2023, 83, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorali, F.; Khosravi, H.; Moradi, B. Automatic microscopic diagnosis of diseases using an improved UNet++ architecture. Tissue Cell 2022, 76, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood Cell Segmentation Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/jeetblahiri/bccd-dataset-with-mask (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells. Available online: https://bbbc.broadinstitute.org/BBBC030?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Lempitsky, V.; Zisserman, A. Learning to Count Objects in Images. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2010, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. CSRNet: Dilated Convolutional Neural Networks for Understanding the Highly Congested Scenes. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; He, Y.; Xu, D.; Kuo, J.Y.; Lei, H.; Lei, B. Joint segmentation and classification task via adversarial network: Application to HEp-2 cell images. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 114, 108156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archit, A.; Freckmann, L.; Nair, S.; Khalid, N.; Hilt, P.; Rajashekar, V.; Freitag, M.; Teuber, C.; Spitzner, M.; Contreras, C.T.; et al. Segment Anything for Microscopy. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.; Lalit, M.; McDole, K.; Funke, J. Unsupervised Learning of Object-Centric Embeddings for Cell Instance Segmentation in Microscopy Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 21206–21215. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, U.; Marks, M.; Dilip, R.; Li, Q.; Yu, C.; Laubscher, E.; Iqbal, A.; Pradhan, E.; Ates, A.; Abt, M.; et al. CellSAM: A foundation model for cell segmentation. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 2585–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lee, N.; Lee, S. A Method of Deep Learning Model Optimization for Image Classification on Edge Device. Sensors 2022, 22, 7344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. In Proceedings of the NIPS 2014 Deep Learning Workshop, Montreal, QC, Canada, 12–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Elsken, T.; Metzen, J.H.; Hutter, F. Neural Architecture Search: A Survey. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.05377. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Maaten, L.v.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1608.06993. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dice, L.R. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association Between Species. Ecology 1945, 26, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

| BCE Loss | Focal Loss | |||||||||||

| Model | Acc | Dice | Sens | mIoU | Acc | Dice | Sens | mIoU | ||||

| UNet | 98.0 | 96.5 | 96.8 | 93.4 | 97.9 | 96.3 | 96.4 | 93.0 | ||||

| UNet++ | 98.0 | 96.5 | 97.2 | 93.4 | 97.9 | 96.4 | 96.2 | 93.2 | ||||

| ResUNet | 98.0 | 96.5 | 97.3 | 93.2 | 97.8 | 96.2 | 95.3 | 92.8 | ||||

| EffUNet | 97.8 | 96.3 | 96.9 | 92.9 | 97.7 | 96.0 | 95.9 | 92.4 | ||||

| FPN | 97.9 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 93.1 | 97.9 | 96.3 | 96.2 | 93.0 | ||||

| BiFPN | 97.4 | 95.6 | 96.3 | 91.5 | 97.9 | 96.3 | 96.2 | 93.0 | ||||

| PFPN | 97.9 | 96.4 | 96.5 | 93.1 | 97.9 | 96.3 | 96.2 | 93.0 | ||||

| CellVit | 97.2 | 95.2 | 95.6 | 90.8 | 96.9 | 94.7 | 93.9 | 89.9 | ||||

| EvitUNet | 97.8 | 96.1 | 96.8 | 92.5 | 97.4 | 95.5 | 94.6 | 91.5 | ||||

| MaxViTUNet | 97.9 | 96.4 | 96.7 | 93.0 | 97.8 | 96.1 | 96.0 | 92.6 | ||||

| Dice Loss | Efficiency | |||||||||||

| Model | Acc | Dice | Sens | mIoU | size (MB) | latency (ms) | ||||||

| UNet | 98.0 | 96.6 | 97.1 | 93.4 | 124.3 | 21.6 | ||||||

| UNet++ | 98.0 | 96.5 | 97.1 | 93.3 | 138.8 | 28.9 | ||||||

| ResUNet | 98.0 | 96.5 | 97.3 | 93.3 | 26.9 | 21.5 | ||||||

| EffUNet | 97.9 | 96.4 | 97.0 | 93.1 | 69.8 | 46.4 | ||||||

| FPN | 98.0 | 96.5 | 97.1 | 93.2 | 16.7 | 21.5 | ||||||

| BiFPN | 97.4 | 95.6 | 96.3 | 91.7 | 32.4 | 56.3 | ||||||

| PFPN | 98.0 | 96.5 | 96.8 | 93.3 | 47.5 | 27.2 | ||||||

| CellVit | 97.2 | 95.3 | 95.8 | 91.0 | 33.5 | 27.3 | ||||||

| EvitUNet | 97.6 | 96.0 | 97.0 | 92.3 | 68.4 | 26.5 | ||||||

| MaxViTUNet | 97.9 | 96.4 | 96.9 | 93.1 | 133.5 | 42.7 | ||||||

| BCE Loss | Threshold | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| UNet | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| UNet++ | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| ResUNet | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| EffUNet | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| FPN | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| BiFPN | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| PFPN | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| CellVit | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.90 |

| EvitUNet | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| MaxViTUNet | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Focal Loss | ||||||||||

| Model | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| UNet | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| UNet++ | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| ResUNet | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.84 |

| EffUNet | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| FPN | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| BiFPN | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| PFPN | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| CellVit | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.80 |

| EvitUNet | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| MaxViTUNet | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Dice Loss | ||||||||||

| Model | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| UNet | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| UNet++ | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| ResUNet | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| EffUNet | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| FPN | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| BiFPN | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| PFPN | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| CellVit | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| EvitUNet | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| MaxViTUNet | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Model | No Quantization | FP16 Quantization | Pruning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | Size | Latency | Acc | Size | Latency | Acc | Size | Latency | |

| UNet | 93 | 124.3 | 21.6 | 93 | 62.2 | 23.6 | 91 | 79.4 | 25.5 |

| UNet++ | 95 | 138.8 | 28.9 | 95 | 67.0 | 29.5 | 93 | 85.4 | 31.2 |

| ResUNet | 91 | 26.9 | 21.5 | 91 | 13.4 | 21.4 | 88 | 17.1 | 22.7 |

| FPN | 92 | 16.7 | 21.1 | 92 | 8.4 | 22.7 | 89 | 13.2 | 23.1 |

| BiFPN | 91 | 32.4 | 41.3 | 91 | 16.4 | 36.1 | 87 | 27.2 | 43.4 |

| PFPN | 92 | 47.5 | 27.2 | 92 | 23.8 | 24.3 | 88 | 30.2 | 20.4 |

| EffUNet | 91 | 69.8 | 26.4 | 92 | 35.0 | 29.8 | 87 | 44.8 | 25.1 |

| CellVit | 92 | 33.5 | 27.3 | 91 | 16.8 | 28.4 | 89 | 28.1 | 29.3 |

| EvitUNet | 92 | 68.4 | 26.5 | 91 | 34.2 | 26.9 | 88 | 42.7 | 31.2 |

| MaxViTUNet | 96 | 133.5 | 44.9 | 96 | 63.8 | 44.0 | 57 | 117.28 | 50.6 |

| BCE Loss | Focal Loss | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Acc | Dice | Sens | mIoU | Acc | Dice | Sens | mIoU | ||||

| UNet | 99.7 | 91.9 | 92.9 | 85.3 | 99.7 | 92.2 | 91.6 | 85.7 | ||||

| UNet++ | 99.7 | 93.1 | 93.8 | 87.3 | 99.7 | 92.5 | 92.5 | 86.3 | ||||

| ResUNet | 99.7 | 92.5 | 92.2 | 86.3 | 99.7 | 92.0 | 90.0 | 85.5 | ||||

| EffUNet | 99.5 | 86.0 | 81.6 | 75.9 | 99.4 | 83.8 | 75.1 | 72.7 | ||||

| FPN | 99.7 | 92.3 | 93.8 | 85.9 | 99.6 | 91.0 | 89.6 | 83.8 | ||||

| BiFPN | 99.3 | 81.9 | 80.9 | 69.6 | 99.3 | 79.6 | 74.3 | 66.6 | ||||

| PFPN | 99.7 | 91.7 | 91.8 | 84.9 | 99.7 | 91.3 | 90.9 | 84.3 | ||||

| CellVit | 99.2 | 78.6 | 76.3 | 65.5 | 99.2 | 77.4 | 69.7 | 63.9 | ||||

| EvitUNet | 99.7 | 92.0 | 91.9 | 85.4 | 99.6 | 90.7 | 89.4 | 83.3 | ||||

| MaxViTUNet | 99.7 | 91.5 | 92.0 | 84.5 | 99.6 | 91.1 | 91.5 | 84.0 | ||||

| Dice Loss | Efficiency | |||||||||||

| Model | Acc | Dice | Sens | mIoU | size (MB) | latency (ms) | ||||||

| UNet | 99.7 | 92.8 | 92.7 | 86.7 | 124.3 | 11.28 | ||||||

| UNet++ | 99.7 | 93.2 | 95.0 | 87.3 | 138.8 | 17.04 | ||||||

| ResUNet | 99.7 | 92.8 | 93.2 | 86.8 | 26.9 | 11.33 | ||||||

| EffUNet | 99.5 | 88.0 | 84.3 | 79.1 | 69.8 | 19.35 | ||||||

| FPN | 99.7 | 92.6 | 94.2 | 86.3 | 16.7 | 10.46 | ||||||

| BiFPN | 99.3 | 80.5 | 78.6 | 67.8 | 32.4 | 32.09 | ||||||

| PFPN | 99.7 | 92.8 | 93.2 | 86.8 | 47.5 | 11.41 | ||||||

| CellVit | 99.0 | 73.2 | 69.6 | 58.4 | 33.5 | 20.72 | ||||||

| EvitUNet | 99.6 | 91.0 | 91.5 | 83.8 | 68.4 | 13.34 | ||||||

| MaxViTUNet | 99.7 | 92.0 | 92.3 | 85.4 | 133.5 | 31.52 | ||||||

| BCE Loss | Threshold | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| UNet | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| UNet++ | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| ResUNet | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| EffUNet | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| FPN | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| BiFPN | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| PFPN | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| CellVit | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| EvitUNet | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| MaxViTUNet | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Focal Loss | ||||||||||

| Model | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| UNet | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| UNet++ | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| ResUNet | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| EffUNet | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| FPN | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| BiFPN | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| PFPN | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| CellVit | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| EvitUNet | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| MaxViTUNet | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Dice Loss | ||||||||||

| Model | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 |

| UNet | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| UNet++ | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| ResUNet | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| EffUNet | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| FPN | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| BiFPN | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| PFPN | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| CellVit | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| EvitUNet | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| MaxViTUNet | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, G.; Park, J.; Lee, S. Optimal Cell Segmentation and Counting Strategy for Embedding in Low-Power AIoT Devices. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010357

Park G, Park J, Lee S. Optimal Cell Segmentation and Counting Strategy for Embedding in Low-Power AIoT Devices. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010357

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Gunwoo, Junmin Park, and Sungjin Lee. 2026. "Optimal Cell Segmentation and Counting Strategy for Embedding in Low-Power AIoT Devices" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010357

APA StylePark, G., Park, J., & Lee, S. (2026). Optimal Cell Segmentation and Counting Strategy for Embedding in Low-Power AIoT Devices. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010357