The Decomposition Mechanism of C4F7N–Ag Gas Mixture Under High Temperature Arc

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

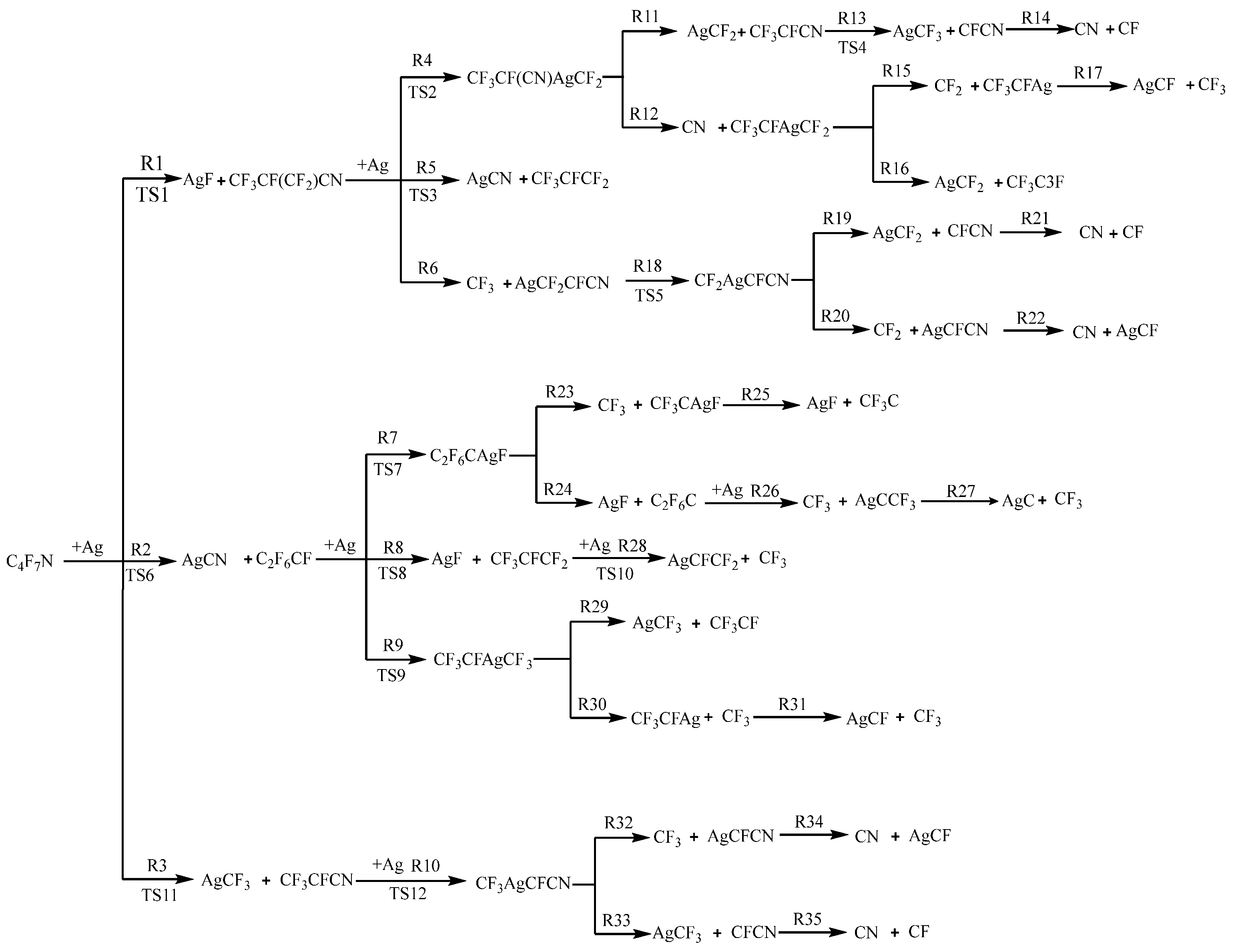

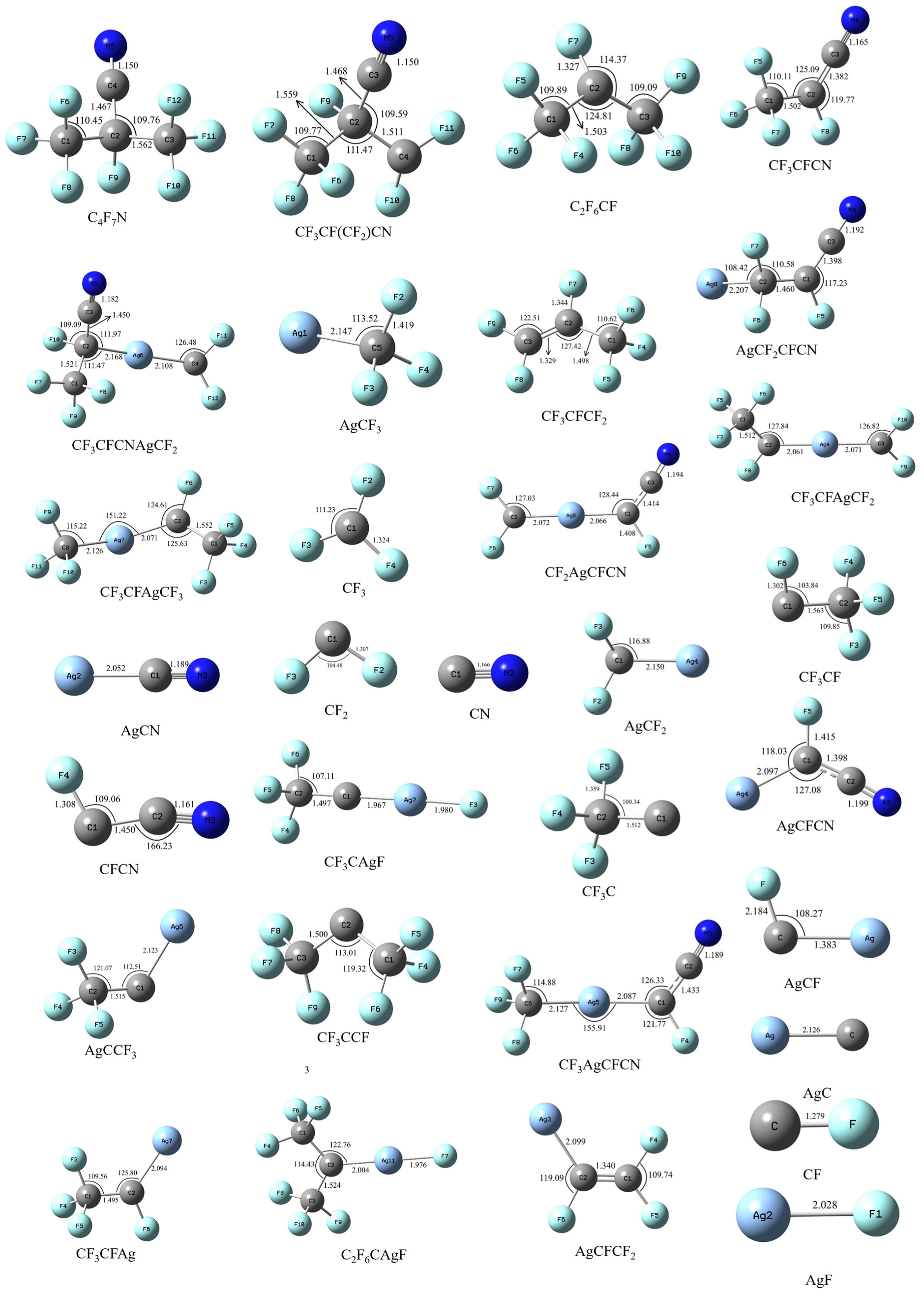

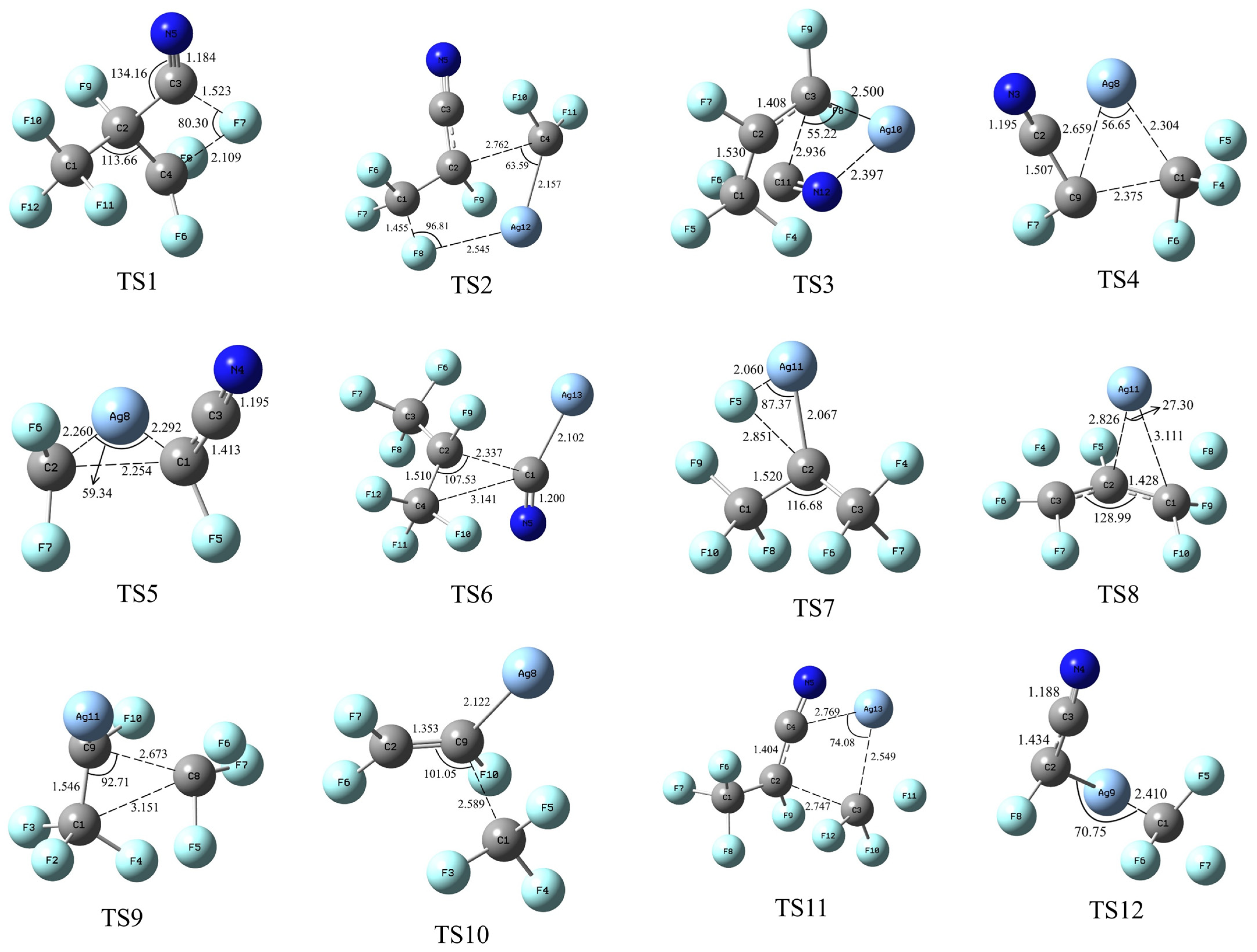

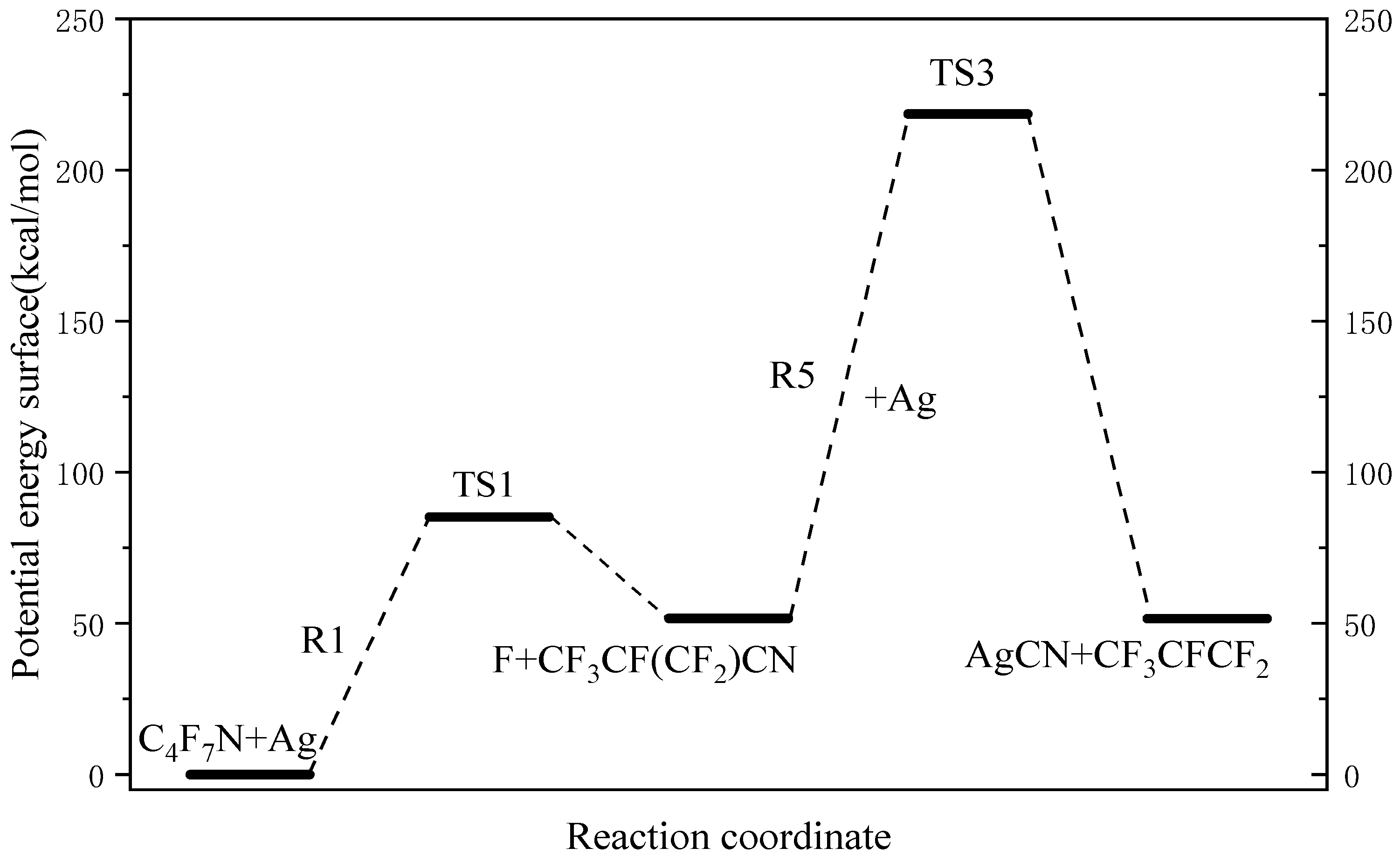

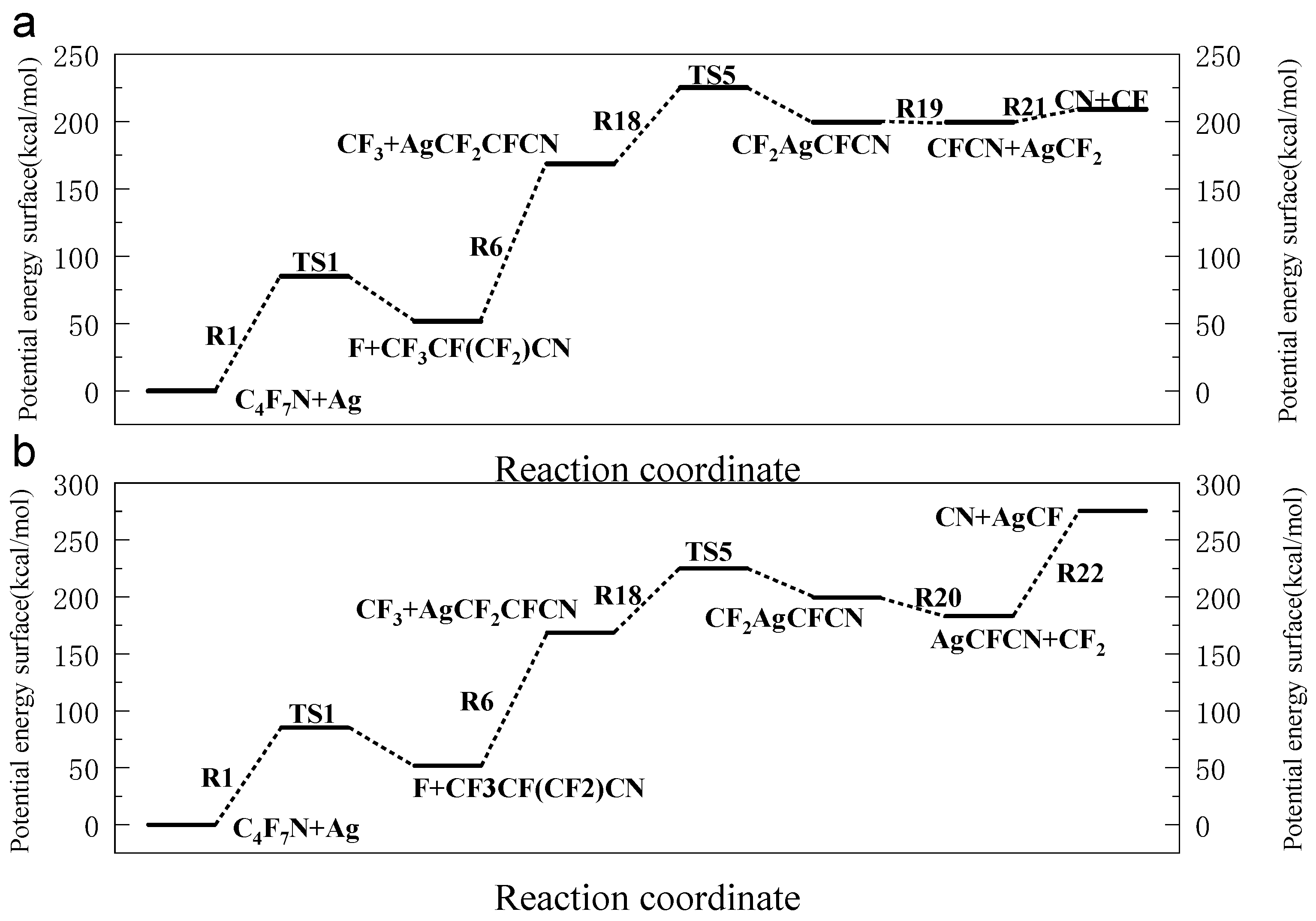

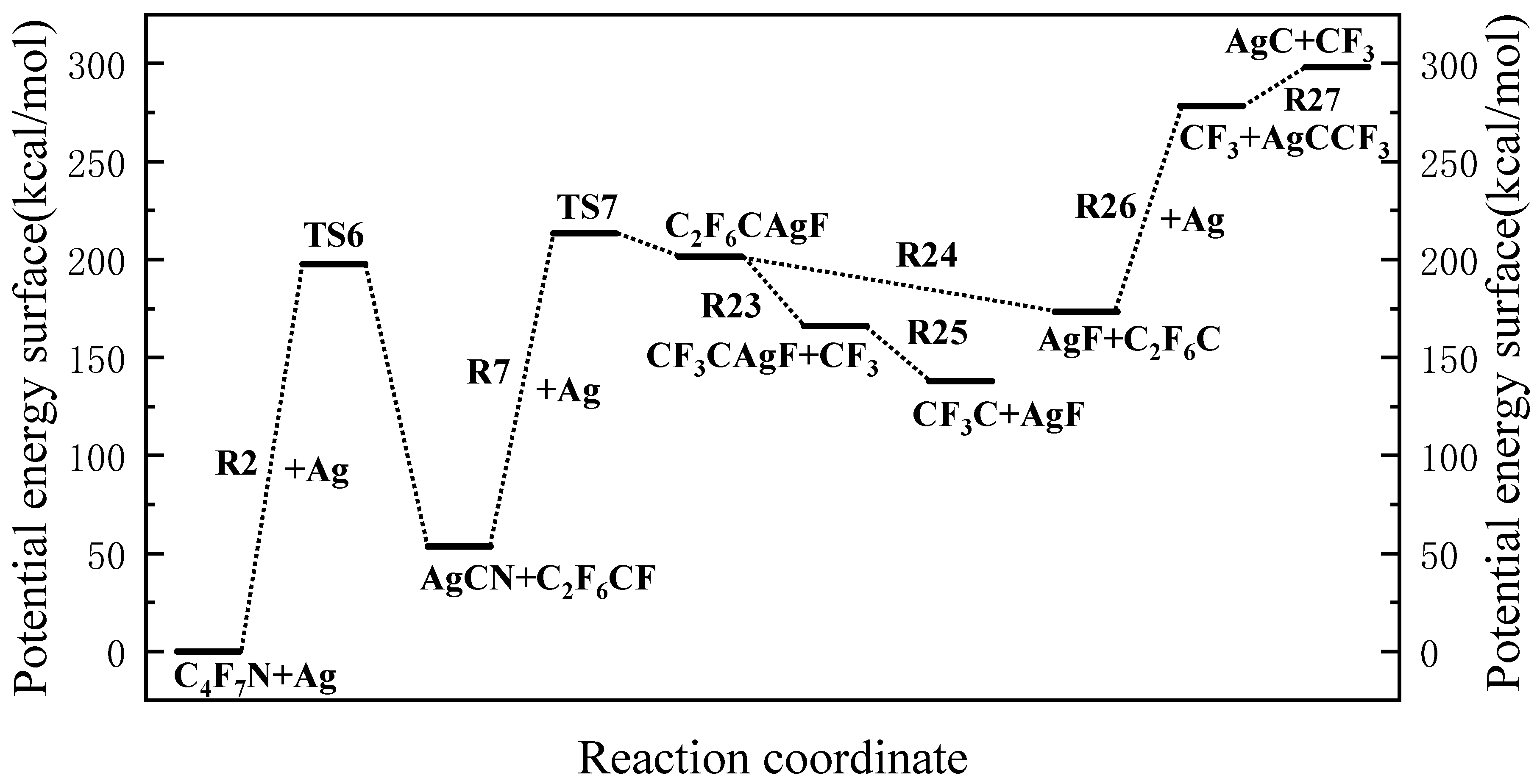

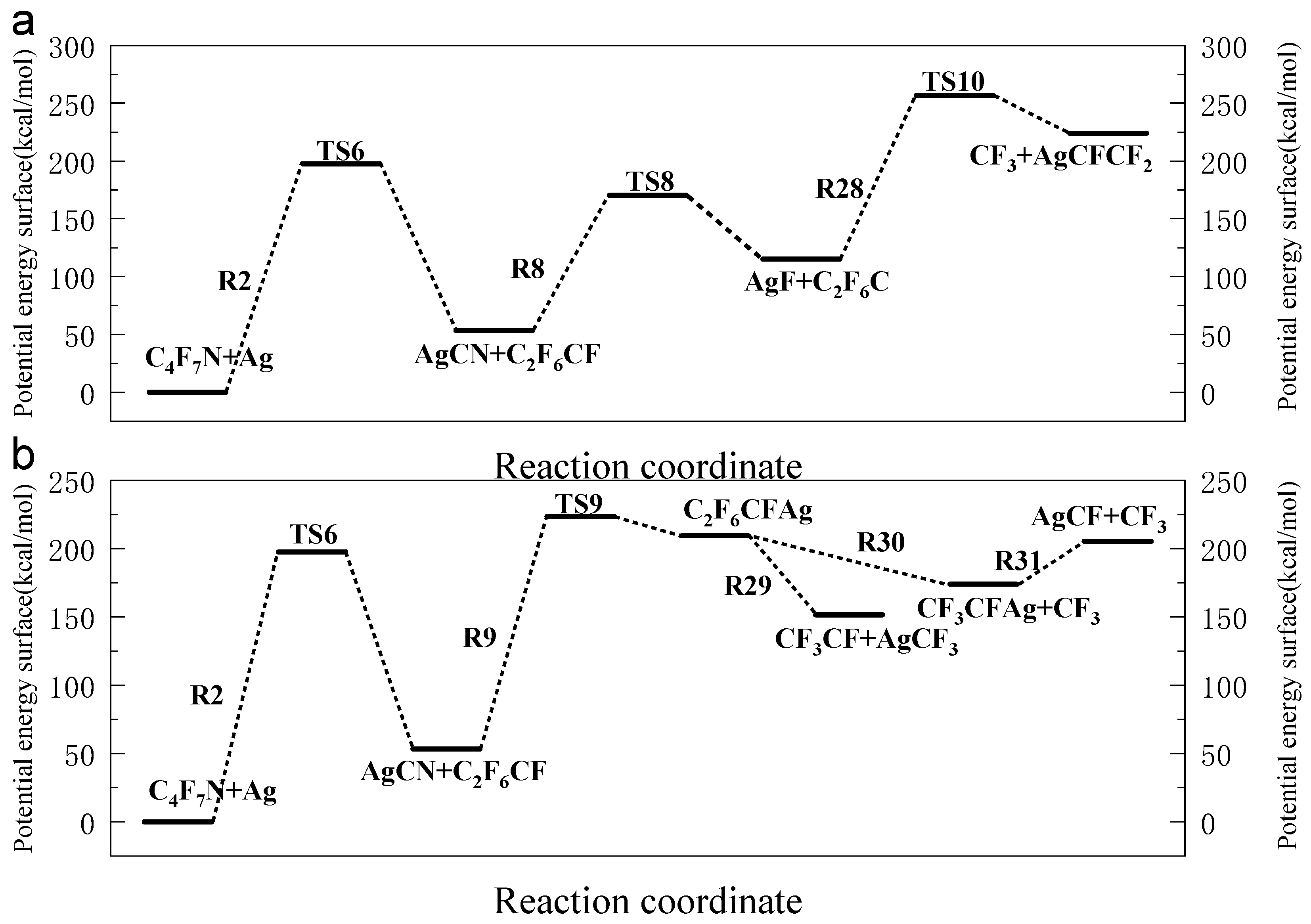

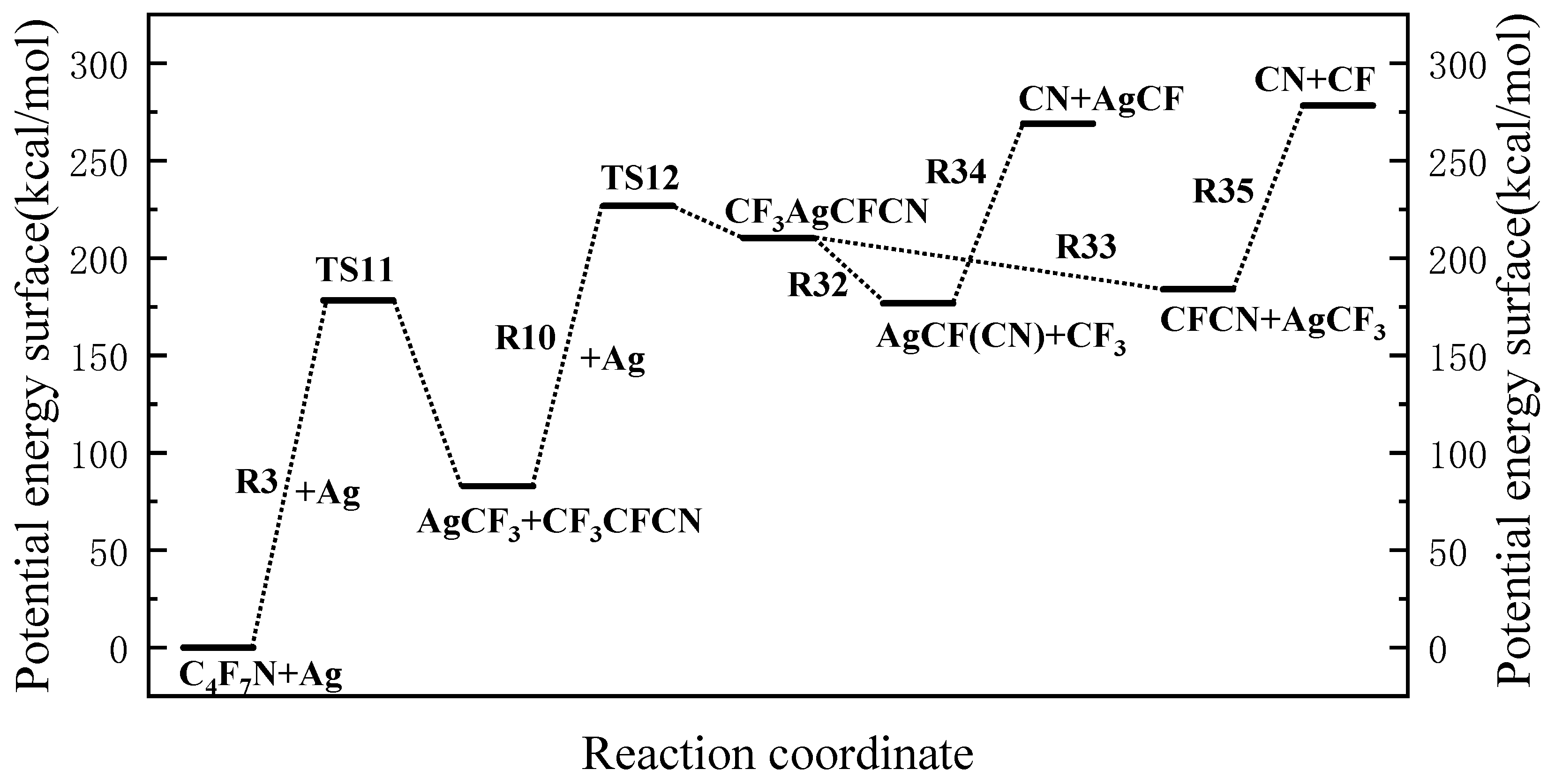

3.1. The Decomposition Pathway of C4F7N Under Ag Vaper

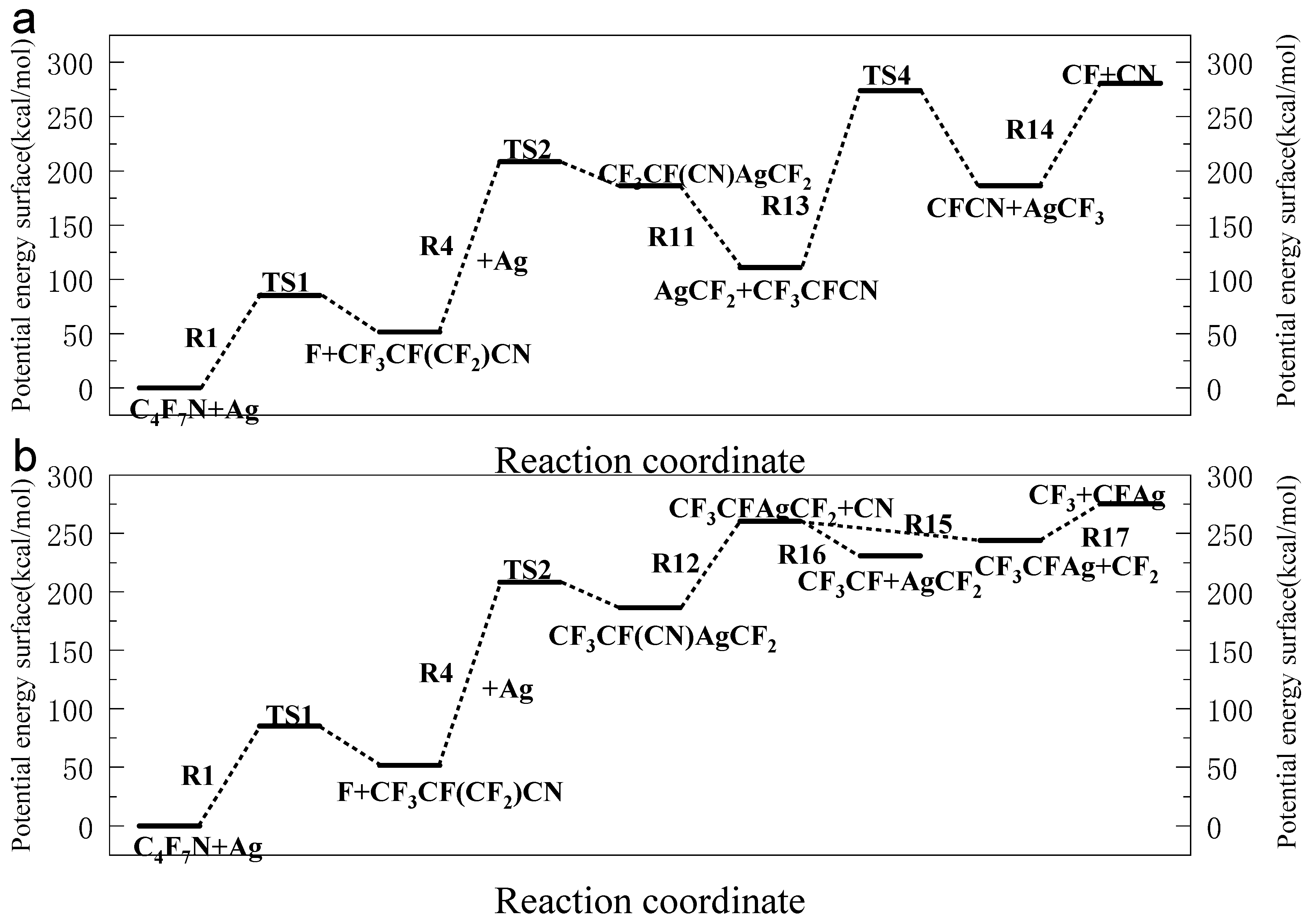

3.2. Decomposition Mechanisms of C4F7N

3.3. Main Degradation Pathways of C4F7N

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Key findings indicate that C4F7N undergoes three primary initial decomposition routes in the presence of Ag vapor, leading to the formation of various intermediate species such as C4F6N, C2F6CF, and C3F4N. Subsequent reactions involve bond cleavage, fluorine transfer, and the formation of Ag-containing compounds such as AgF, AgCN, and AgCF3.

- (2)

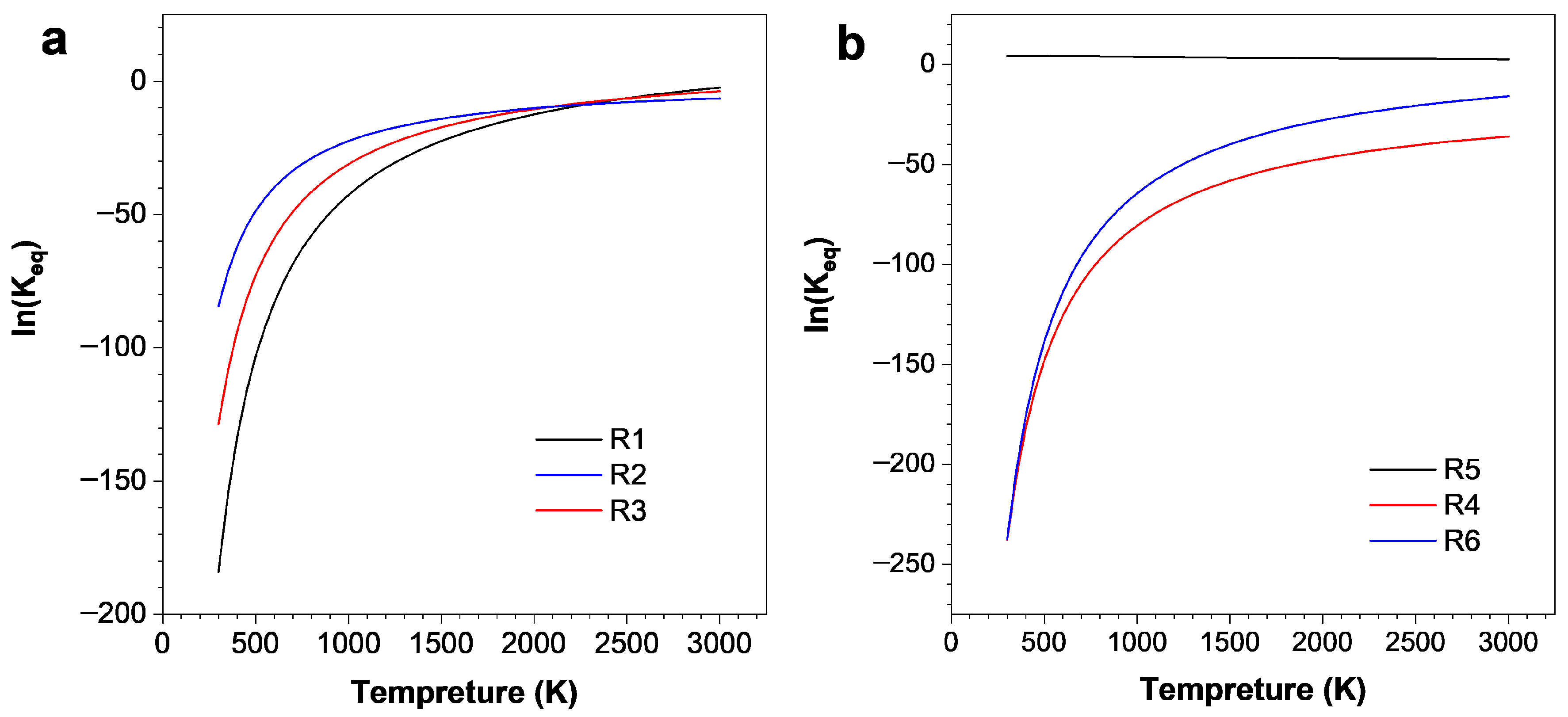

- The reaction equilibrium constants (Keq) were calculated, revealing temperature-dependent behavior, with ln(Keq) values between 300 K to 3000 K. The most possible decomposition pathway of C4F7N under Ag vapor is R1 → R5.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, W.; Wei, W. Transregional electricity transmission and carbon emissions: Evidence from ultra-high voltage transmission projects in China. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Deng, Y.; Kong, J.; Fu, W.; Liu, C.; Jin, T.; Jiao, L. Toward the High-Voltage Stability of Layered Oxide Cathodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Challenges, Progress, and Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2402008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Zhou, D.; Pang, L.; Sun, S.; Zhou, T.; Su, J. Perspectives on Working Voltage of Aqueous Supercapacitors. Small 2022, 18, 2106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Yuan, K.; Chen, Y. Wide Voltage Aqueous Asymmetric Supercapacitors: Advances, Strategies, and Challenges. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.M.; Jang, Y.S.; Nguyen, H.V.T.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, Y.; Park, B.J.; Seo, D.H.; Lee, K.-K.; Han, Z.; Ostrikov, K.; et al. Advances in high-voltage supercapacitors for energy storage systems: Materials and electrolyte tailoring to implementation. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, D. A review of multiphase energy conversion in wind power generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Guo, Q.; Qi, J.; Ajjarapu, V.; Bravo, R.; Chow, J.; Li, Z.; Moghe, R.; Nasr-Azadani, E.; Tamrakar, U.; et al. Review of Challenges and Research Opportunities for Voltage Control in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 2790–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaqing, Z.; Yubiao, H.; Xinjie, Q.; Taiyun, Z. A Review on Fire Research of Electric Power Grids of China: State-Of-The-Art and New Insights. Fire Technol. 2024, 60, 1027–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Chen, B.-H.; Liang, P.; Sun, Y.; Fang, Z.; Huang, S. Experimental Evaluation of Protecting High-Voltage Electrical Transformers Using Water Mist with and without Additives. Fire Technol. 2019, 55, 1671–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, E.A.; Moore, F.L.; Elkins, J.W.; Rosenlof, K.H.; Laube, J.C.; Röckmann, T.; Marsh, D.R.; Andrews, A.E. Quantification of the SF6 lifetime based on mesospheric loss measured in the stratospheric polar vortex. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2017, 122, 4626–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Z.; Pu, Y.; Tang, N. Evaluating the dielectric strength of promising SF6 alternatives by DFT calculations and DC breakdown tests. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2020, 27, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Han, B. Theoretical studies on dielectric breakdown strength increasing mechanism of SF6 and its potential alternative gases. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2015, 31, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Franck, C.M. High voltage insulation properties of HFO1234ze. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2015, 22, 3260–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.; Tang, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, D. Decomposition Properties of C4F7N/N2 Gas Mixture: An Environmentally Friendly Gas to Replace SF6. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 5173–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xie, S.; Wu, S.; Cui, H. Adsorptions of C5F10O decomposed compounds on the Cu-decorated NiS2 monolayer: A first-principles theory. Mol. Phys. 2023, 121, e2163715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, M.; Franck, C.M. Computational screening of new high voltage insulation gases with low global warming potential. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2015, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, A.; Rong, M.; Zhu, F. The decomposition mechanism of C4F7N-Cu gas mixtures. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Rong, M. Effects of Buffer Gases on Plasma Properties and Arc Decaying Characteristics of C4F7N–N2 and C4F7N–CO2 Arc Plasmas. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2019, 39, 1379–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Luo, B. The variation of C4F7N, C5F10O, and their decomposition components in breakdown under different pressures. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 065010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Cui, Z.; Xiao, S.; Tang, J. Study on the thermal interaction mechanism between C4F7N-N2 and copper, aluminum. Corros. Sci. 2019, 153, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Feng, X.; Lei, Z.; Xia, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S.; Yao, Q.; Tang, J. Thermal Decomposition Mechanism of Environmental-Friendly Insulating Gas C5F10O on Cu (1 1 1) Surface. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2021, 41, 1455–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.T.; Pietrzak, P.; Franck, C.M. Cu/W Electrode Ablation and Its Influence on Free-Burning Arcs in SF6 Alternatives. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2022, 50, 3715–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Cui, Z. Insight into the compatibility between C4F7N and silver: Experiment and theory. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 126, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Yang, T. Decomposition pathway of C4F7N gas considering the participation of ions. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 143303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, P.; Perret, M.; Boening, M.; Glomb, S.; Kurte, R.; Franck, C.M. Wear of the Arcing Contacts and Gas Under Free Burning Arc in SF6 Alternatives. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 2133–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Geng, Z.; Lin, Y. The Decomposition Pathways of C4F7N/CO2 Mixtures in the Presence of Organic Insulator Vapors. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 9335–9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Deng, Z.; Tang, J. Effects of micro-water on decomposition of the environment-friendly insulating medium C5F10O. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 065017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, X.; He, M. Theoretical study of the decomposition mechanism of C5F10O in the presence of Cu vapor. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 115010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Dai-Jun, L.; Jian-Jun, C. Molecular structure and properties of sulfur dioxide under the external electric field. Acta Phys. Sin. 2016, 65, 053101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Sun, Q.; Duan, X.; Huang, H. Theoretical study by density functional theory calculations of decomposition processes and primary products of C5F10O with moisture content. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 485204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, C.; Zeng, F.; Dai, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Tang, J. Theoretical Analysis on the Self-Recovery Ability of C5F10O: An Environmental-Friendly Substitute for SF6. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2022, 50, 4620–4627. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Chen, Q. Shermo: A general code for calculating molecular thermochemistry properties. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2021, 1200, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Reaction Formula |

|---|---|

| 1 | C4F7N + Ag → TS1 → C4F6N + AgF |

| 2 | C4F7N + Ag → TS6 → C2F6CF + CNAg |

| 3 | C4F7N + Ag → TS11 → C3F4N + CF3Ag |

| 4 | CF3CF(CF2)CN + Ag → TS2 → CF3CF(CN)AgCF2 |

| 5 | CF3CF(CF2)CN + Ag → TS3 → CF3CFCF2 + AgCN |

| 6 | CF3CF(CF2)CN + Ag → AgCF2CFCN + CF3 |

| 7 | C2F6CF + Ag → TS7→ C2F6CAgF |

| 8 | C2F6CF + Ag → TS8→ CF3CFCF2 + AgF |

| 9 | C2F6CF + Ag → TS9→ CF3CFAgCF3 |

| 10 | CF3CFCN + Ag → TS12 → CF3AgCFCN |

| 11 | CF3CF(CN)AgCF2 → CF3CFCN + AgCF2 |

| 12 | CF3CF(CN)AgCF2 → CF3CFAgCF2 + CN |

| 13 | CF3CFCN → TS4 → AgCF3 + CFCN |

| 14 | CFCN → CN + CF |

| 15 | CF3CFAgCF2 → CF2 + CF3CFAg |

| 16 | CF3CFAgCF2 → CF2Ag + CF3CF |

| 17 | CF3CFAg → AgCF + CF3 |

| 18 | AgCF2CFCN → TS5 → CF2AgCFCN |

| 19 | CF2AgCFCN → CF2Ag + CFCN |

| 20 | CF2AgCFCN → CF2 + AgCFCN |

| 21 | CFCN → CF + CN |

| 22 | AgCFCN → AgCF + CN |

| 23 | C2F6CAgF → CF3CAgF + CF3 |

| 24 | C2F6CAgF → C2F6C + AgF |

| 25 | CF3CAgF → CF3C + AgF |

| 26 | C2F6C + Ag → CF3 + AgCCF3 |

| 27 | AgCCF3 → AgC + CF3 |

| 28 | CF3CFCF2 + Ag → TS10 → AgCFCF2 + CF3 |

| 29 | CF3CFAgCF3 → CF3CF + AgCF3 |

| 30 | CF3CFAgCF3 → CF3CFAg + CF3 |

| 31 | CF3CFAg → CF3 + CFAg |

| 32 | CF3AgCFCN → CF3 + AgCFCN |

| 33 | CF3AgCFCN → AgCF3 + CFCN |

| 34 | AgCFCN → AgCF + CN |

| 35 | CFCN → CN + CF |

| Number | Vibrations (cm−1) |

|---|---|

| TS 1 | −548.95, 47.50, 60.76, 133.44, 156.36, 181.94, 228.76, 257.09, 274.48, 307.59, 346.69, 357.02, 390.07, 489.13, 533.11, 552.02, 585.62, 620.21, 675.90, 693.48, 758.47, 882.20, 1030.27, 1150.39, 1190.26, 1226.80, 1282.71, 1449.66, 1460.18, 2015.55 |

| TS 2 | −149.54, 9.67, 48.69, 77.54, 96.29, 104.87, 128.51, 139.15, 177.14, 194.3, 214.9, 231.14, 322.66, 368.45, 398.65, 449.71, 495.48, 515.79, 576.74, 596.33, 616.18, 708.94, 913.77, 969.33, 1054.41, 1066.83, 1097.09, 1123.91, 1275.48, 2226.98 |

| TS 3 | −470.19, 36.09, 65.24, 79.33, 100.95, 113.69, 126.81, 149.45, 206.78, 248.78, 250.14, 280.25, 300.87, 318.29, 339.46, 369.43, 443.47, 485.61, 538.49, 583.16, 643.75, 683.8, 913.17, 1055.14, 1081.64, 1086, 1153.07, 1270.25, 1476.16, 2011.15 |

| TS 4 | −193.30, 31.71, 54.65, 102.60, 112.19, 155.26, 188.40, 199.06, 247.28, 274.78, 428.16, 438.70, 446.15, 572.39, 610.57, 779.05, 788.95, 950.89, 1016.76, 1056.82, 2086.17 |

| TS 5 | −335.28, 47.58, 85.64, 103.81, 110.3, 140, 182.74, 225.22, 285.59, 379.06, 454.58, 542.93, 601.58, 945.92, 978.76, 1040.92, 1124.19, 2079.92 |

| TS 6 | −254.52, 13.73, 35.27, 52.55, 66.09, 80.75, 94.27, 147.1, 153.73, 196.17, 236.73, 260.55, 276.62, 306.95, 323.09, 361.62, 411.29, 450.37, 478.99, 496.75, 564.67, 615.53, 624.53, 701.58, 903.79, 994.2, 1021.73, 1078.58, 1102.31, 1133.6, 1247.65, 1315.63, 2028.06 |

| TS 7 | −119.38, 18.13, 51.72, 55.78, 91.79, 106.53, 156.69, 221.86, 237.41, 277.08, 308.88, 417.89, 455.03, 469.69, 474.79, 481.61, 601.36, 617.41, 656.25, 824.02, 867.63, 994.62, 1039.04, 1040.74, 1116.84, 1134.79, 1252.2 |

| TS 8 | −118.86, 34.58, 46.37, 69.7, 90.7, 141.49, 167.99, 256.21, 295.74, 317.43, 322.26, 336.7, 385.16, 400.45, 426.37, 441.71, 546.14, 559.7, 639.02, 654.98, 789.26, 967.77, 1093.7, 1119.09, 1182.09, 1392.01, 1482.94 |

| TS 9 | −188.37, 32.44, 58.1, 66.33, 95.73, 122.14, 151.59, 160.52, 211.81, 217.38, 239.35, 390.01, 399.31, 439.46, 446.49, 511.46, 527.05, 614.9, 633.71, 822.82, 898.17, 970.82, 1019.64, 1036.46, 1099.25, 1107.88, 1181.86 |

| TS 10 | −85.53, 10.4, 44.76, 52.11, 73.32, 86.36, 99.77, 105.02, 217.35, 263.76, 289.87, 438.05, 441.69, 462.11, 483.6, 589.73, 592.5, 844.99, 911.91, 1044.88, 1056.75, 1107.96, 1183.78, 1634.44 |

| TS 11 | −177.98. 18.43, 26.94, 44.33, 60.4, 69.82, 82.63, 111.08, 150.77, 165.04, 172.83, 195.05, 242.96, 357.2, 372.27, 400.86, 415.57, 420.85, 463.04, 523.12, 540.79, 571.28, 614.91, 694.43, 731.5, 914.94, 983.44, 999.66, 1047.02, 1111.46, 1248.34, 1314.41, 2144.78 |

| TS 12 | −200.35, 25.3, 70.25, 105.38, 124.02, 151.93, 154.01, 210.53, 276.59, 322.8, 428.89, 440.4, 496.16, 611.35, 615.36, 905.43, 958.29, 995.49, 1018.62, 1099.84, 2181.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, C.; Kang, X. The Decomposition Mechanism of C4F7N–Ag Gas Mixture Under High Temperature Arc. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010356

Liu T, Ding Y, Zhang C, Kang X. The Decomposition Mechanism of C4F7N–Ag Gas Mixture Under High Temperature Arc. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010356

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Tan, Yi Ding, Congrui Zhang, and Xingjian Kang. 2026. "The Decomposition Mechanism of C4F7N–Ag Gas Mixture Under High Temperature Arc" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010356

APA StyleLiu, T., Ding, Y., Zhang, C., & Kang, X. (2026). The Decomposition Mechanism of C4F7N–Ag Gas Mixture Under High Temperature Arc. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010356