A Methodology for Beam Deformation Reconstruction Utilizing CEEMDAN-HT-GMM-Ko

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance and Challenges of Deformation Reconstruction

- (1)

- The modal method relies on accurate modal parameters, but the actual structure’s modal parameters change with temperature, load, and damage, leading to a decrease in the accuracy of the calculation based on static modes under environmental disturbances. In addition, noise can significantly affect modal identification;

- (2)

- The inverse finite element method is sensitive to structural parameters. Any material degradation, bolt loosening, or other factors can cause model deviations, increasing the error in deformation calculation and making it difficult to update in real time.

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Empirical Mode Decomposition Methods

1.3. Shortcomings of Existing CEEMDAN Vibration Signal Methods

2. Theory

2.1. Noise Reduction Method Based on CEEMDAN-HT-GMM

2.1.1. CEEMDAN

- (1)

- Add Gaussian white noise signal, ω0n(t), to the original signal, x(t), and to the new signal, x1(t):

- (2)

- x1(t) is decomposed by EMD method to obtain a set of L IMF components, IMF1i(t), and the average value is obtained to obtain the first IMF component, IMF1(t), of CEEMDAN, as shown in the following equation:

- (3)

- Decompose the residual component of adding Gaussian white noise:

- (4)

- Therefore, on the kth residual component, Resk(t) is

- (5)

- Decomposition step by step until it cannot be decomposed, and the final signal, x(t), is decomposed into

2.1.2. Hilbert Transform

2.1.3. Gaussian Mixture Model Clustering

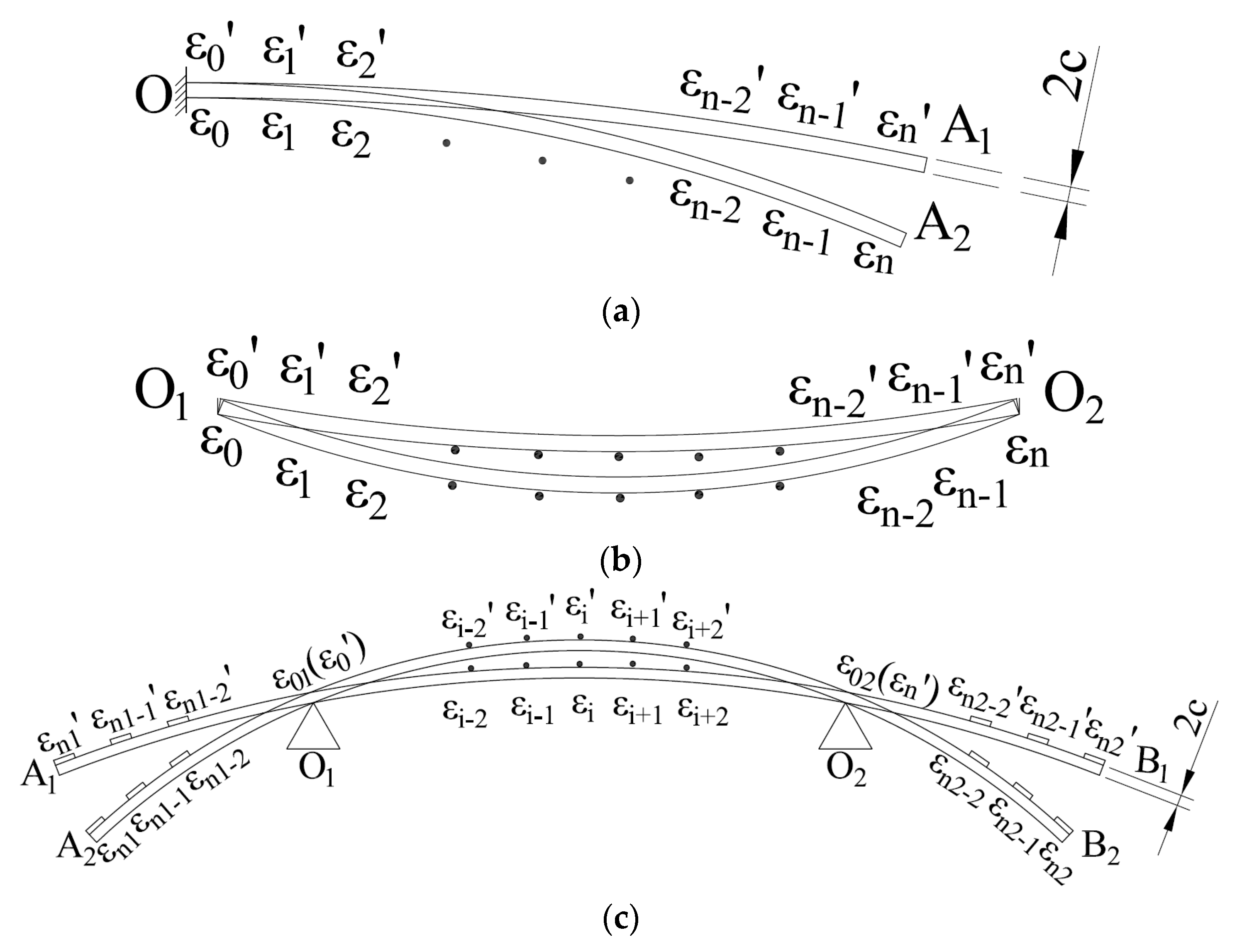

2.2. Deformation Reconstruction Method Based on Ko Displacement Theory

3. Beam Deformation Reconstruction Method Based on CEEMDAN-HT-GMM-Ko

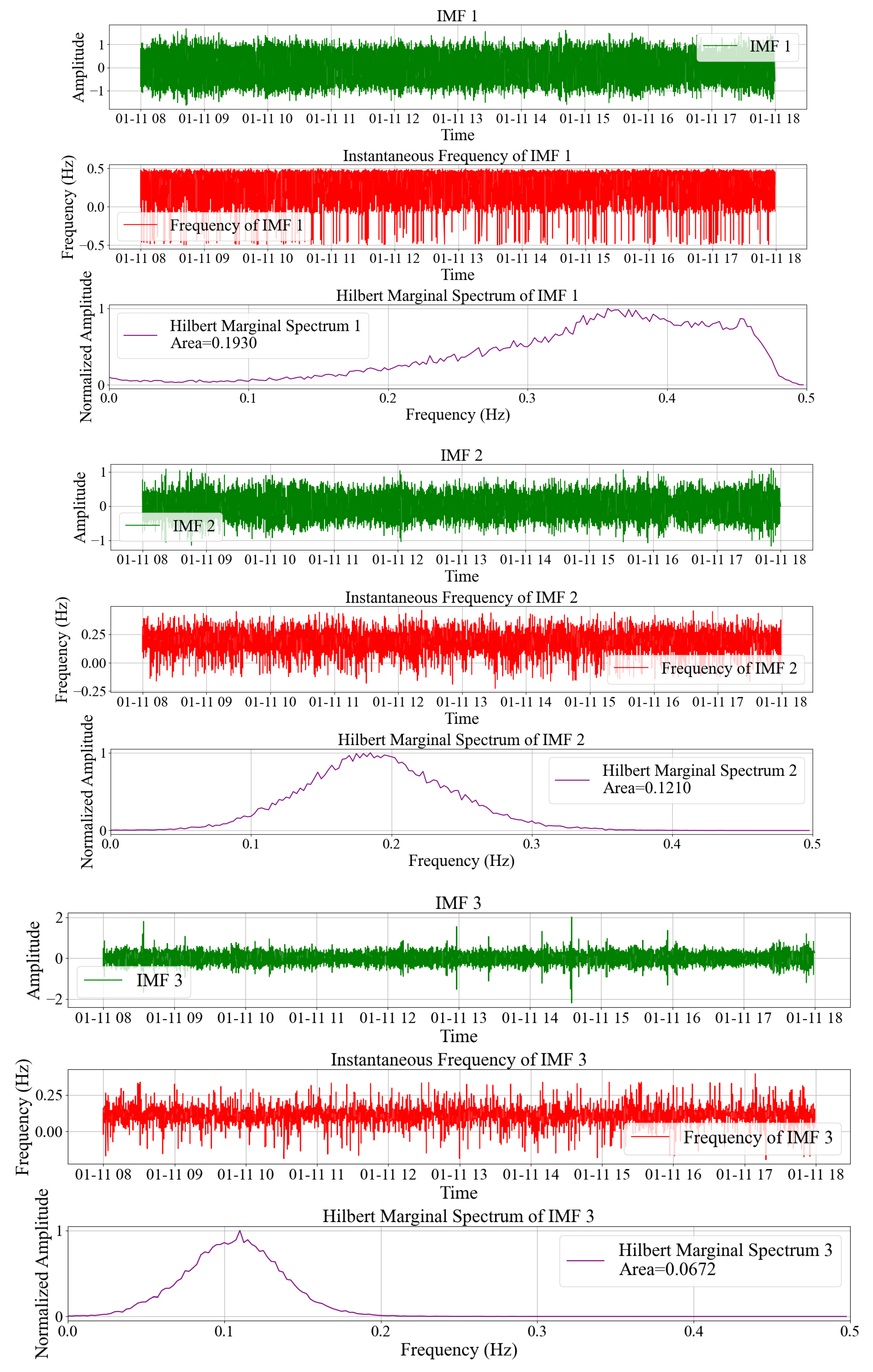

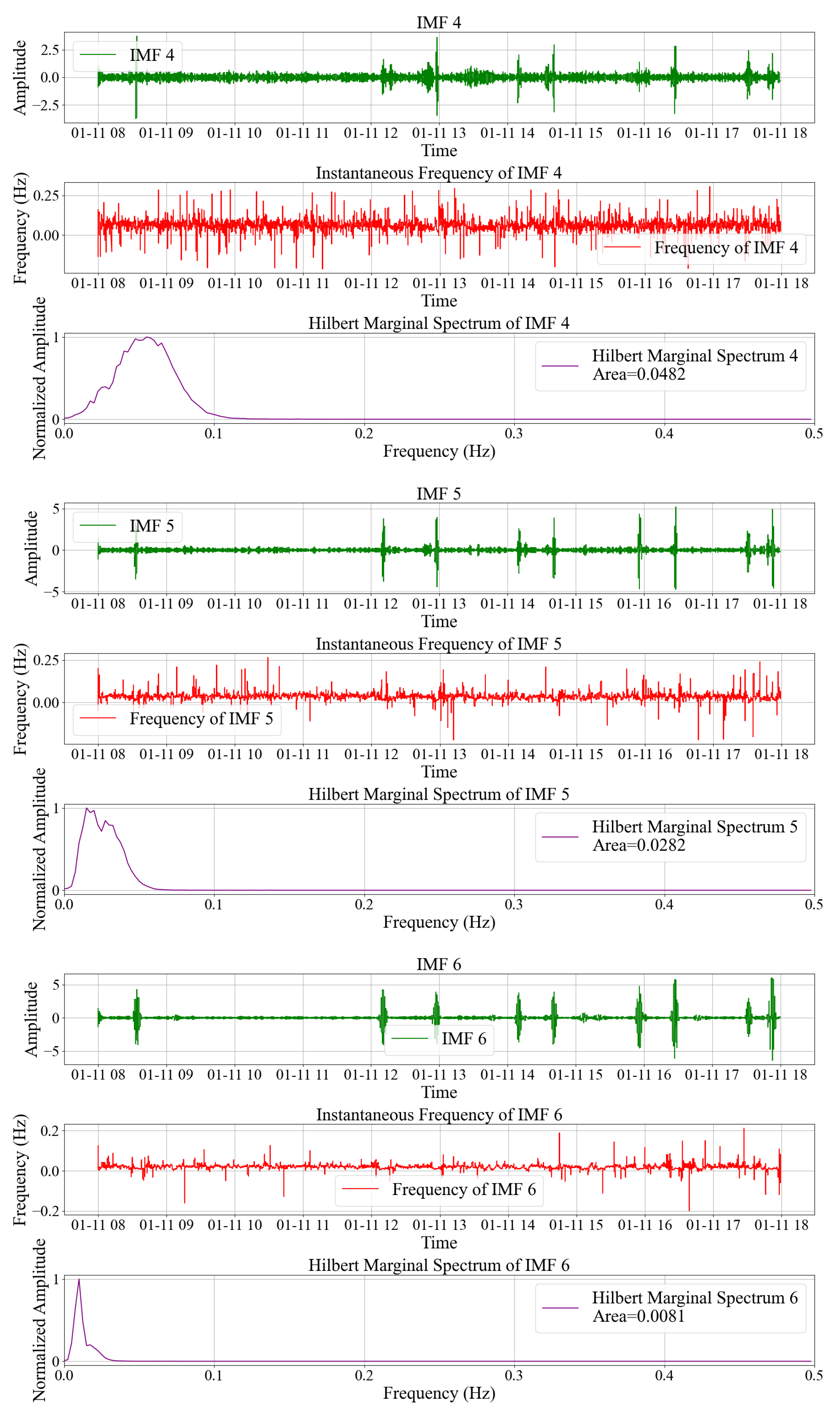

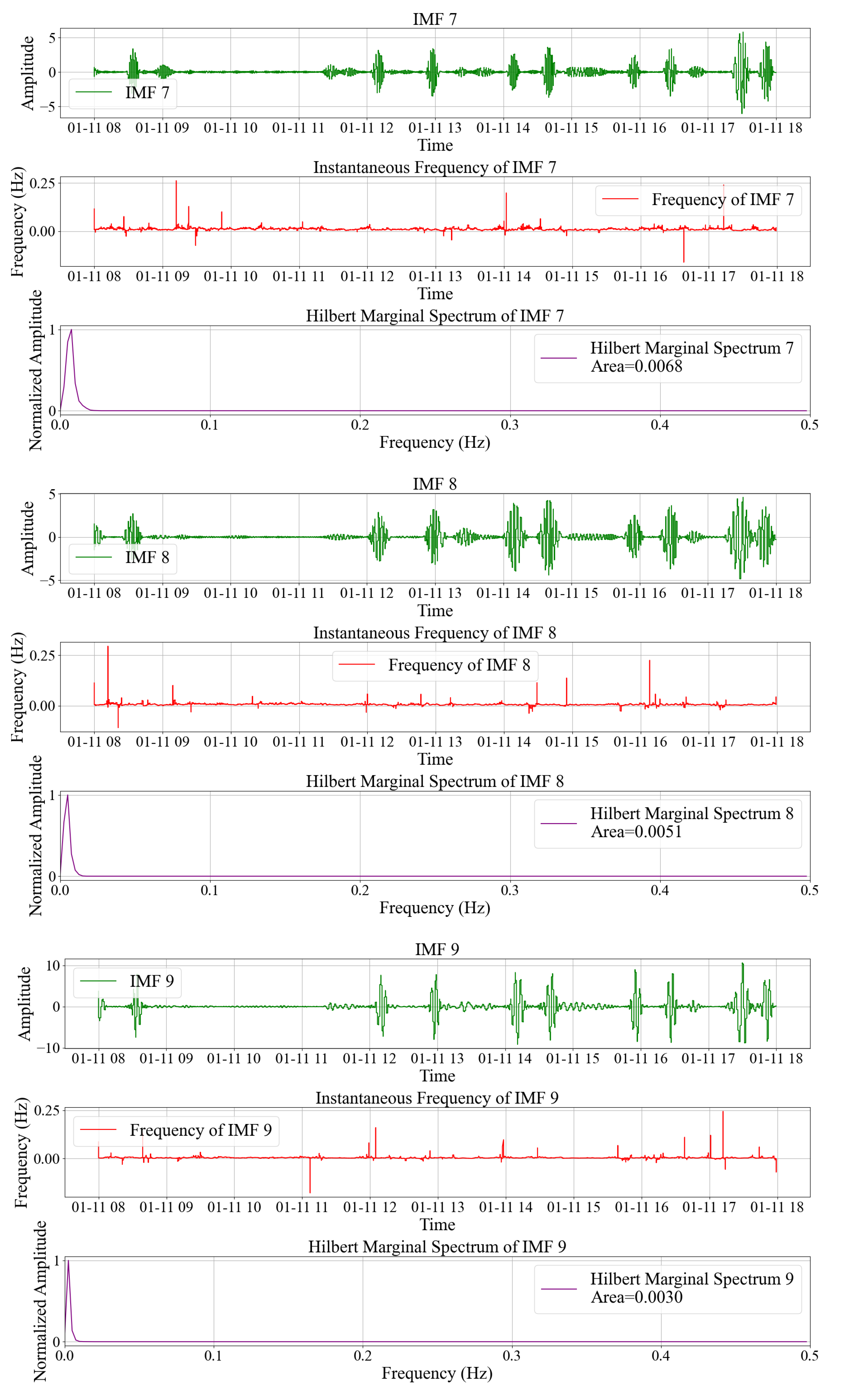

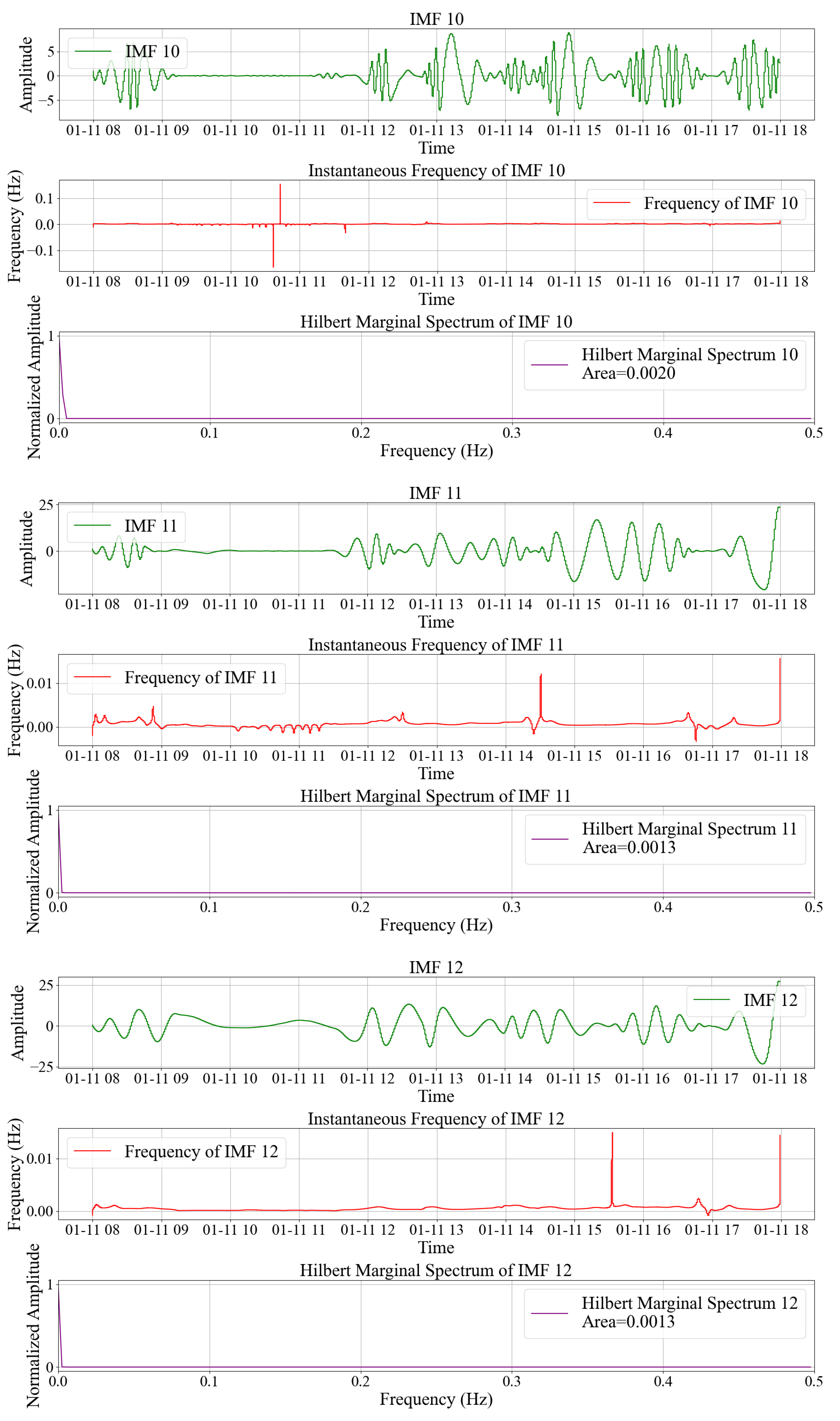

3.1. Obtain the IMF Component of Strain Signal

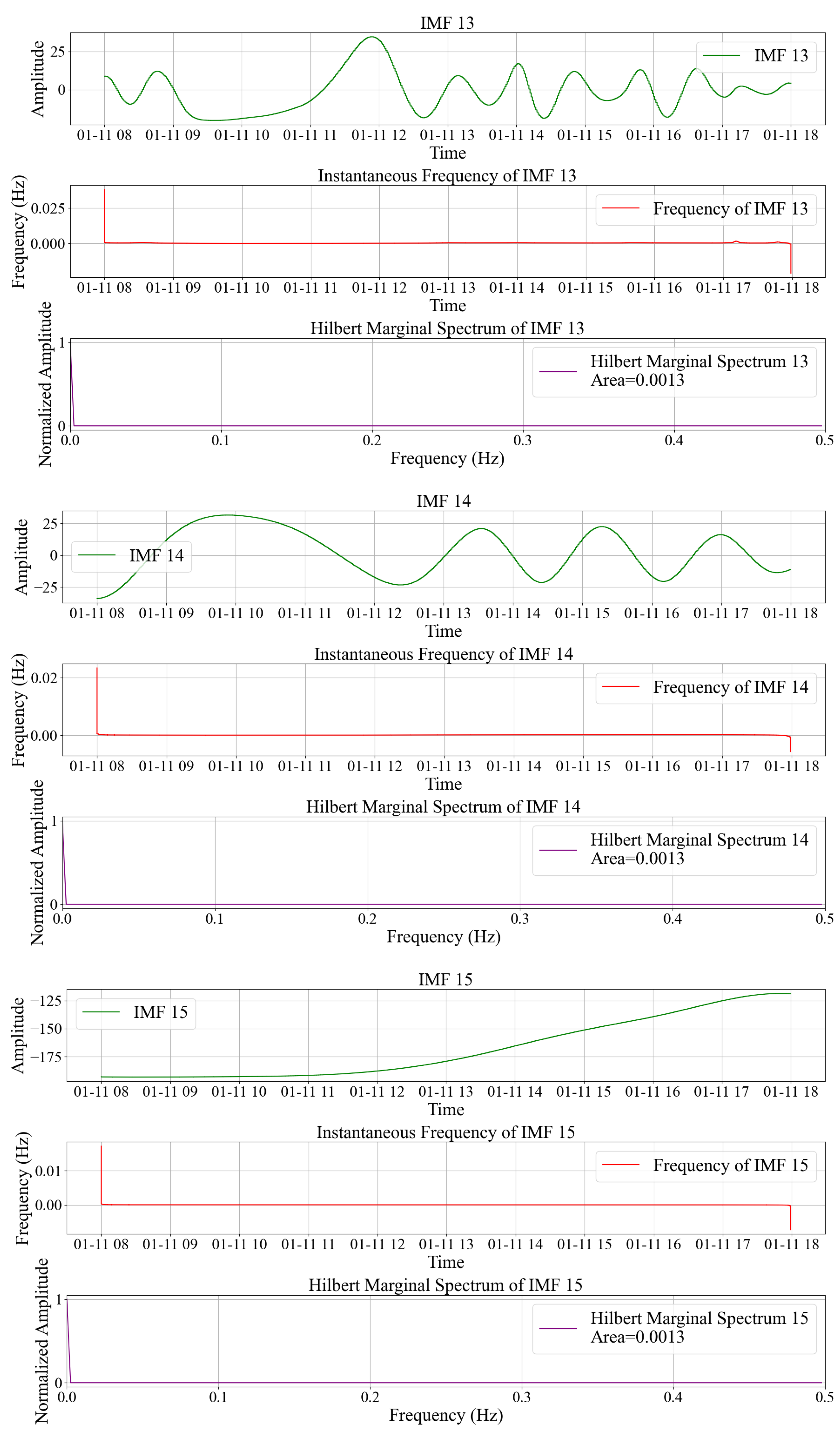

3.2. Obtain the Hilbert Marginal Spectrum and Its Area of the IMF Component

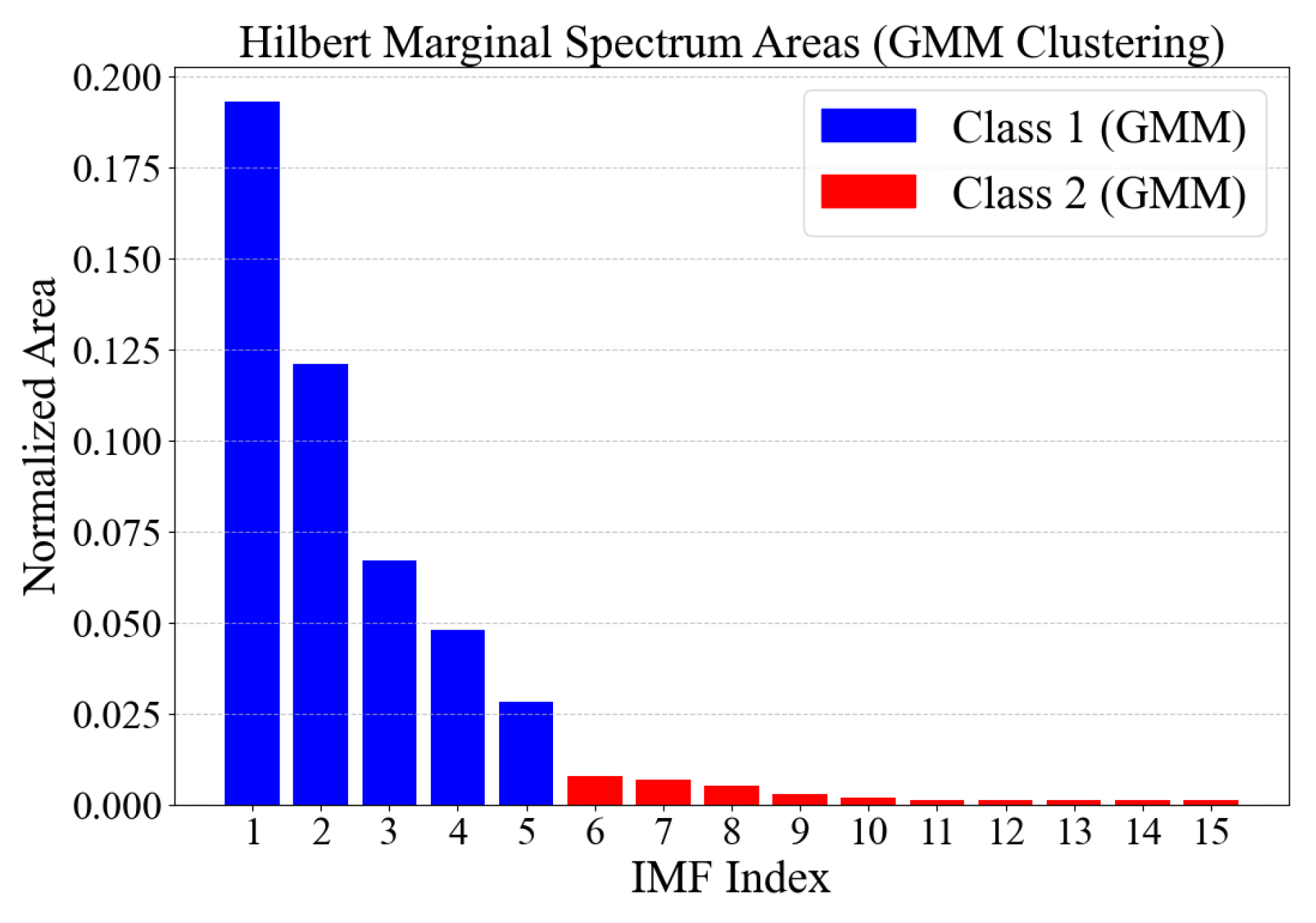

3.3. GMM Is Used to Classify the Area of Hilbert Marginal Spectrum

| Algorithm 1. The algorithm of Gaussian mixture clustering |

| Input: Sample set D = {A1, A2, …, An}; The number of Gaussian mixtures k, k = 2 |

| The process: 1: Initialize the model parameters of the Gaussian mixture distribution {(, , )|i = 1, 2} 2: repeat 3: for j = 1, 2, …, n do 4: Calculate the posterior probability of equation (18) xj generated by each of the mixed components, i.e., (i = 1, 2) 5: end for 6: for i = 1, 2 do 7: Calculate the new mean vector: 8: Calculate the new covariance matrix: 9: Calculate the new mixing coefficient: 10: end for 11: Update model parameter {(,,)|i = 1, 2} to {(,,)|i = 1, 2} 12: until the stop condition is met 13: (i = 1,2) 14: for j = 1, 2, …, n do 15: Determine the cluster marking λj of xj; 16: Divide xj into the corresponding cluster: 17: end for Output: Cluster partition |

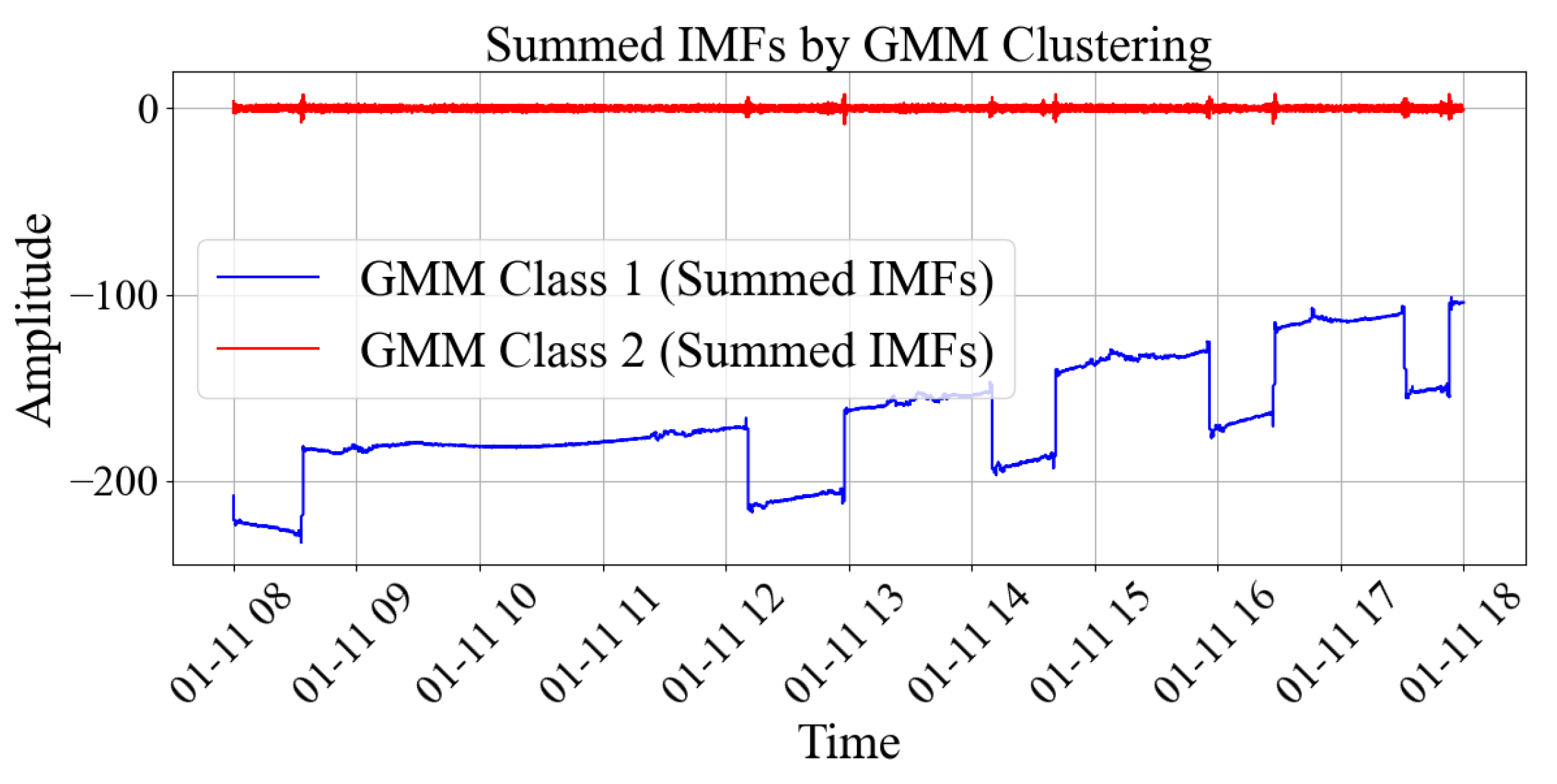

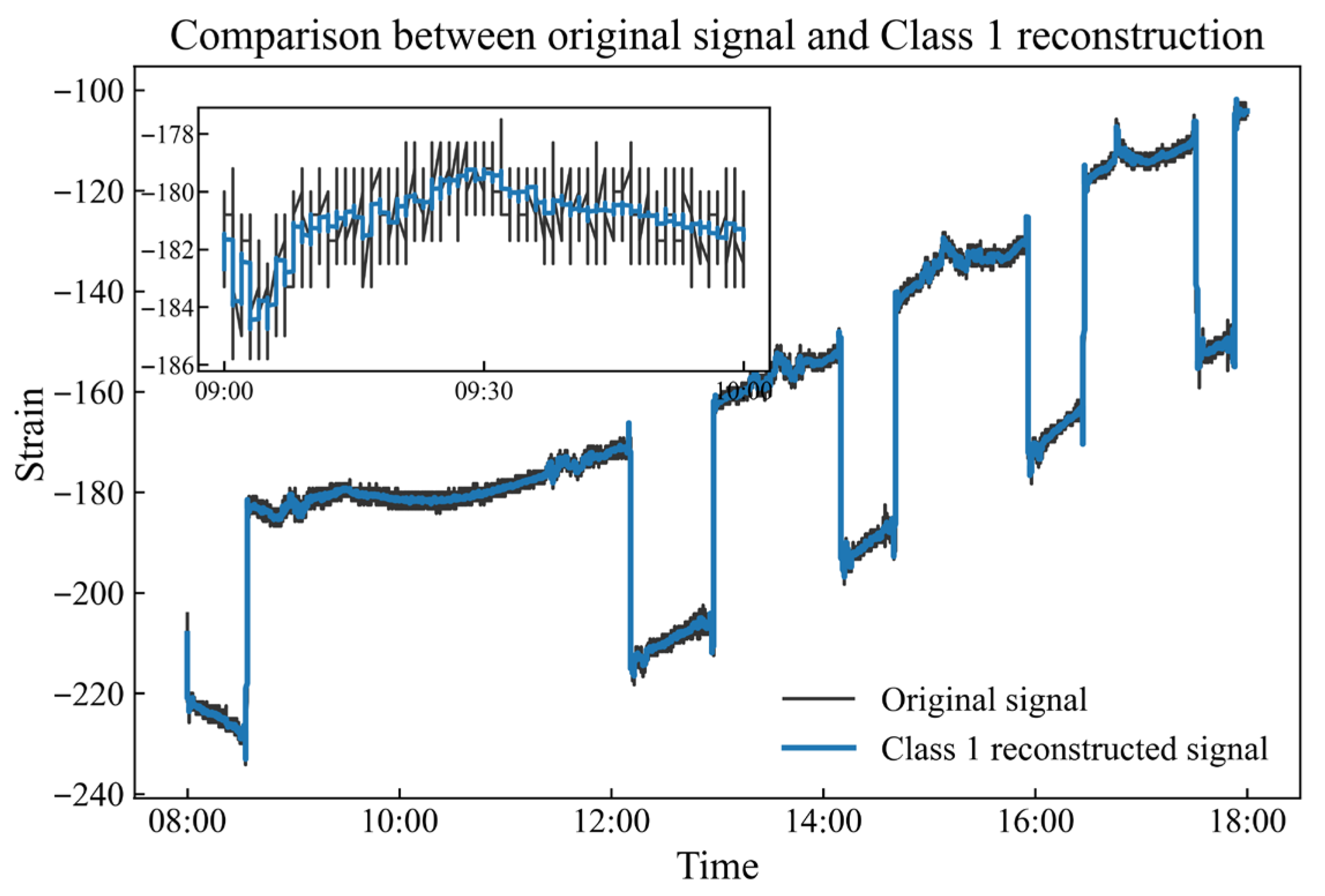

3.4. Obtain the Strain Information After Noise Reduction and Reconstruct the Deformation

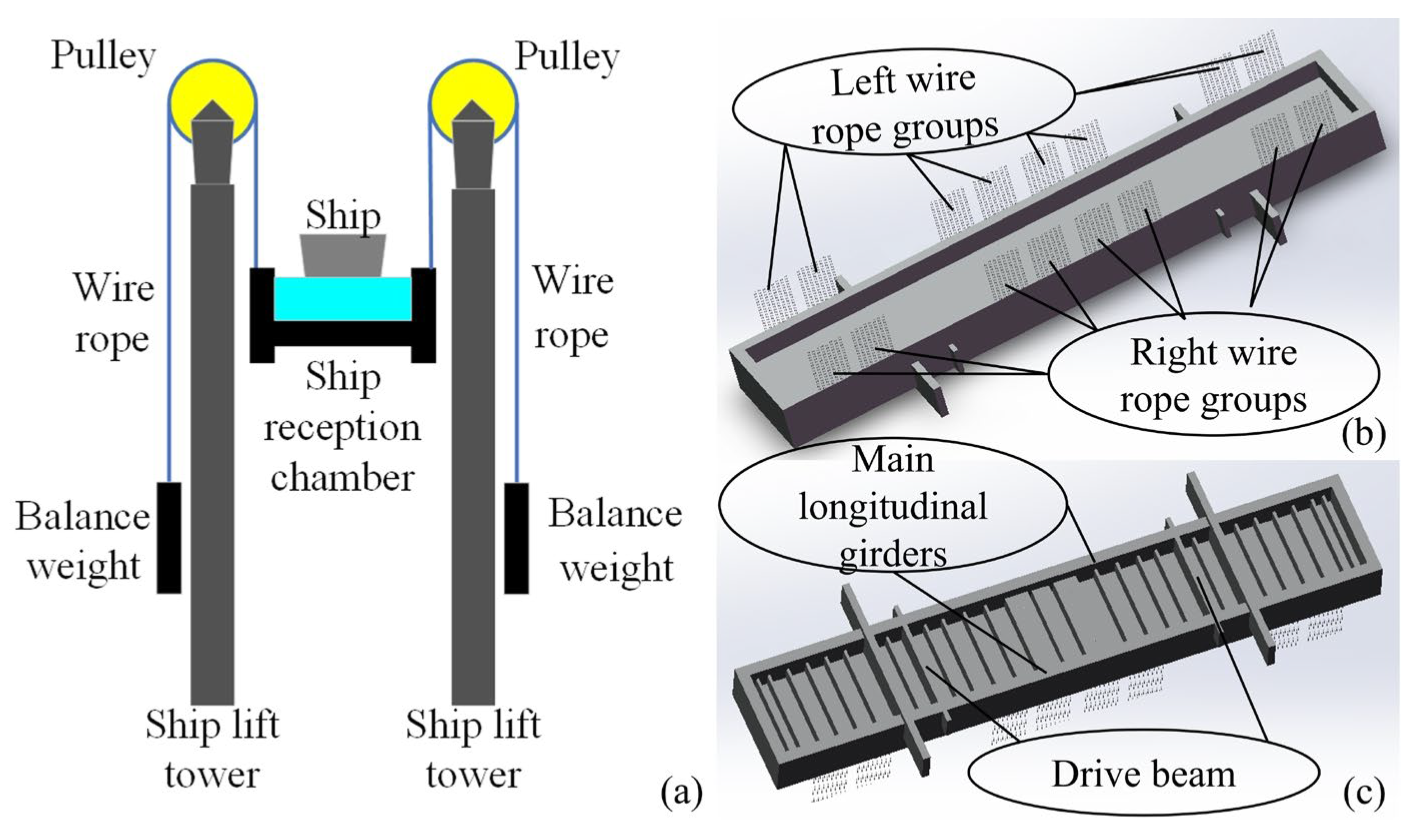

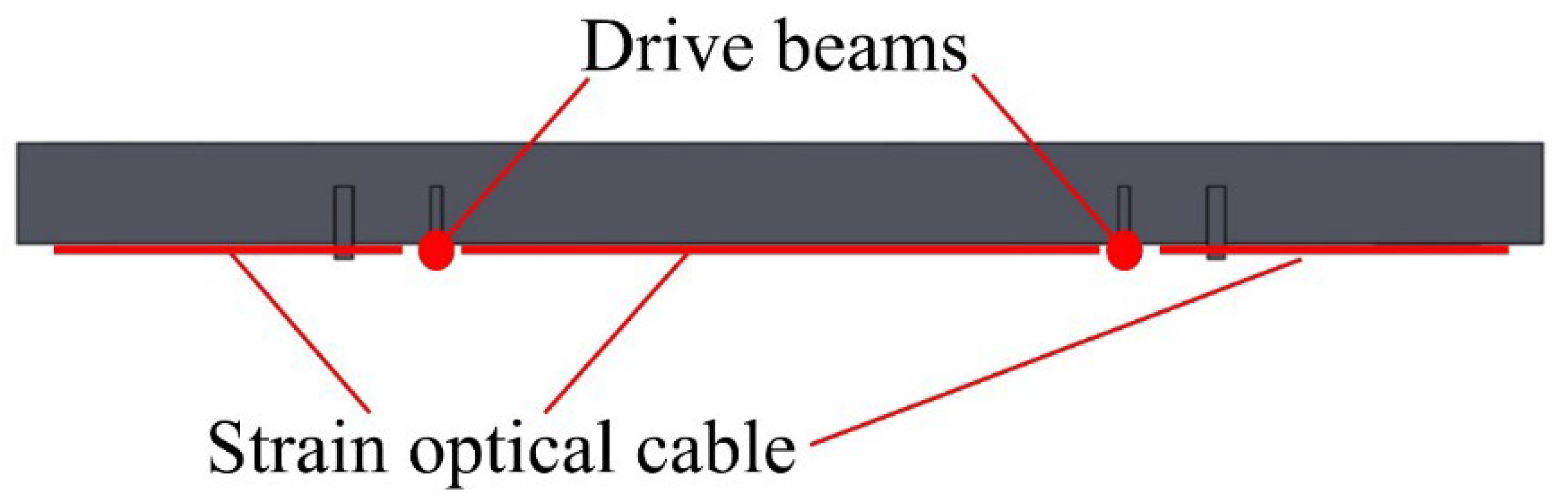

4. Three Gorges Ship Lift Chamber

5. Verification

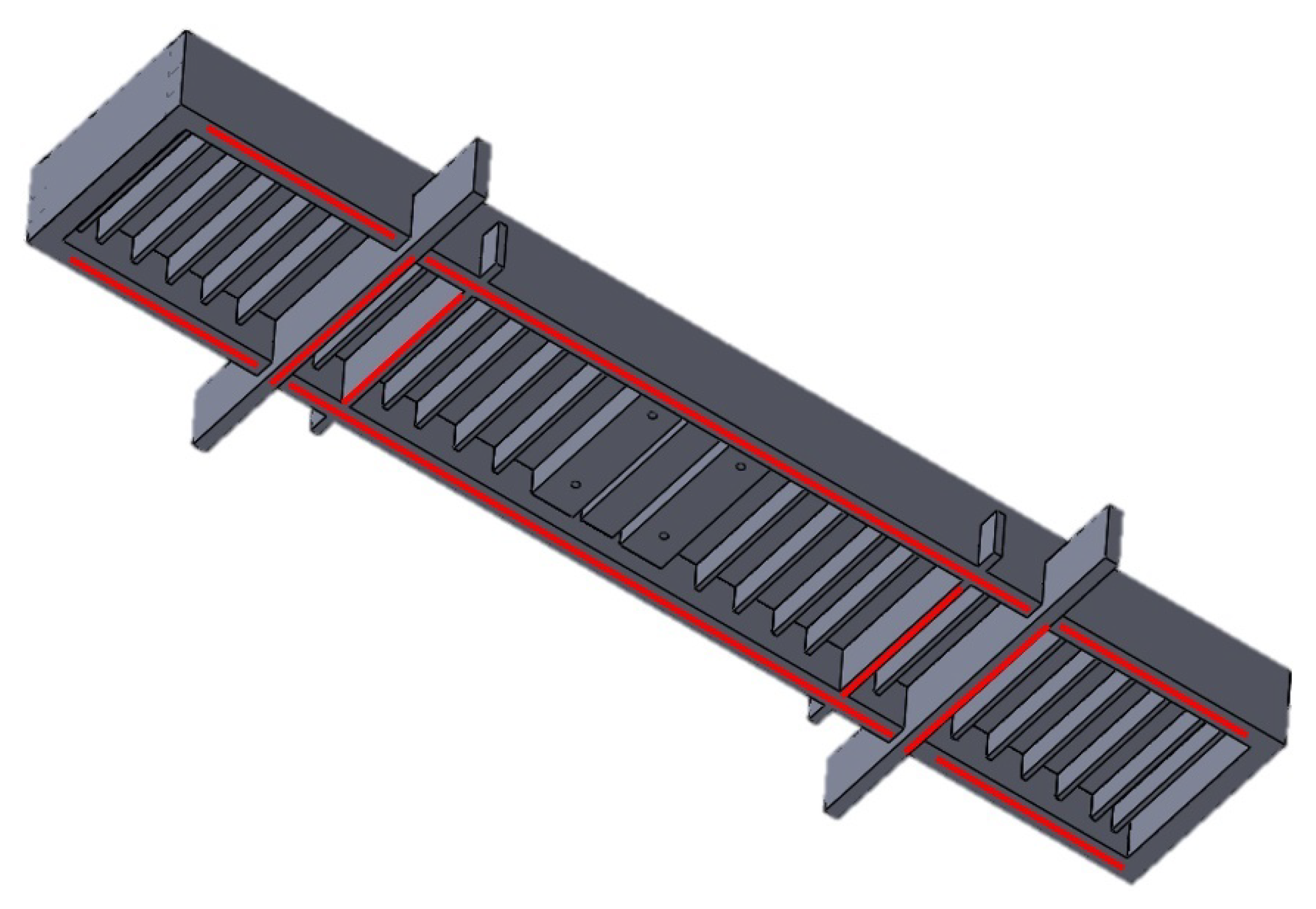

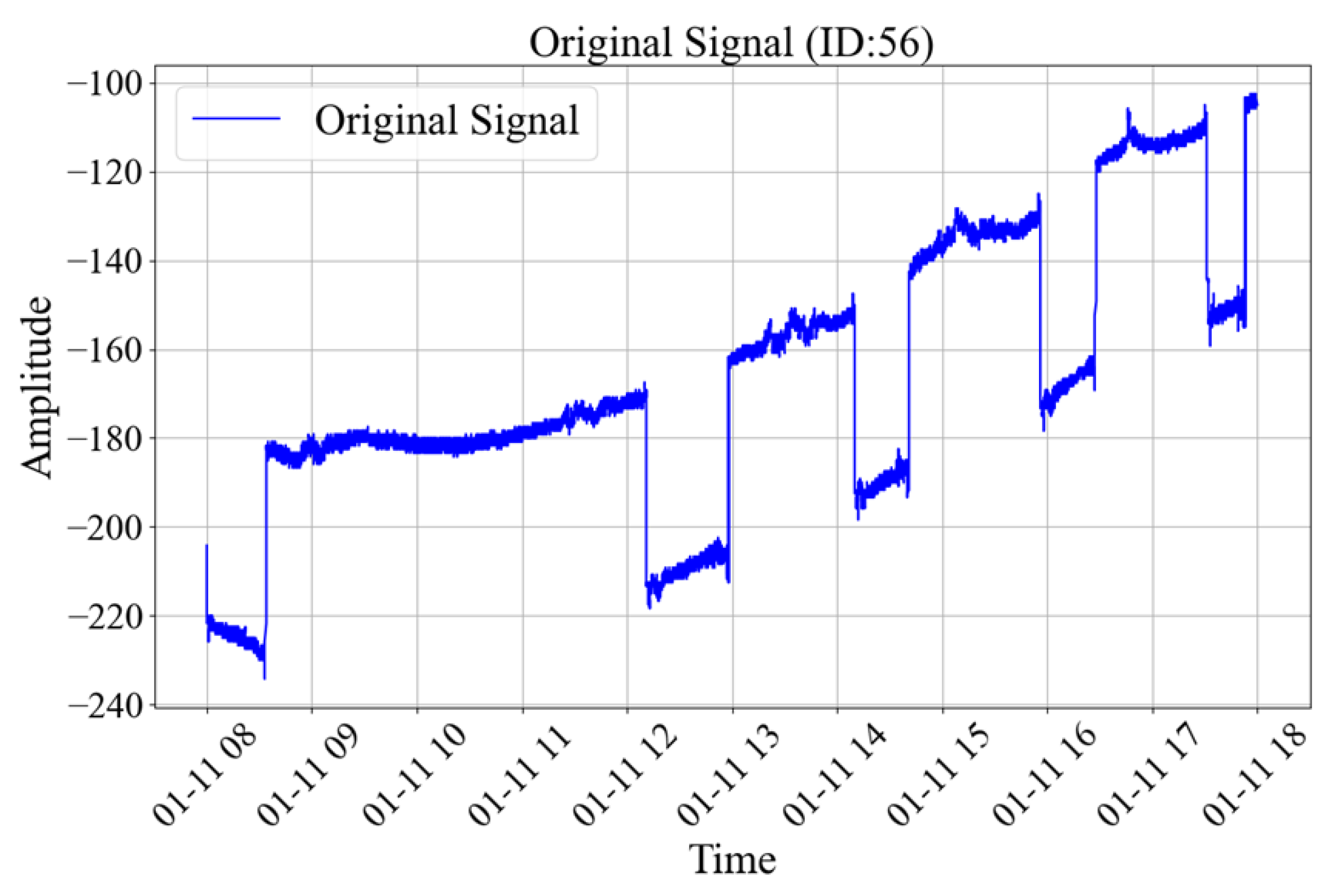

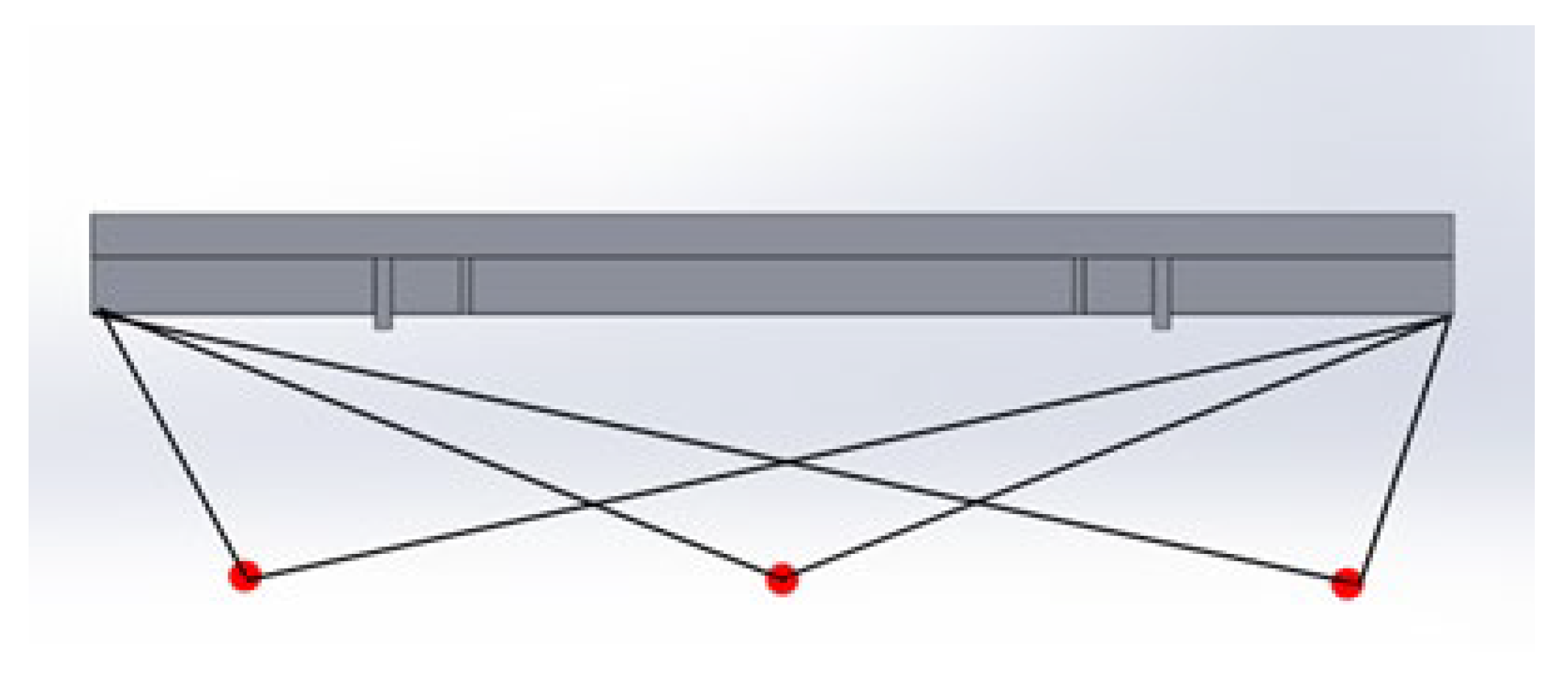

5.1. Data Acquisition

5.2. Data Processing

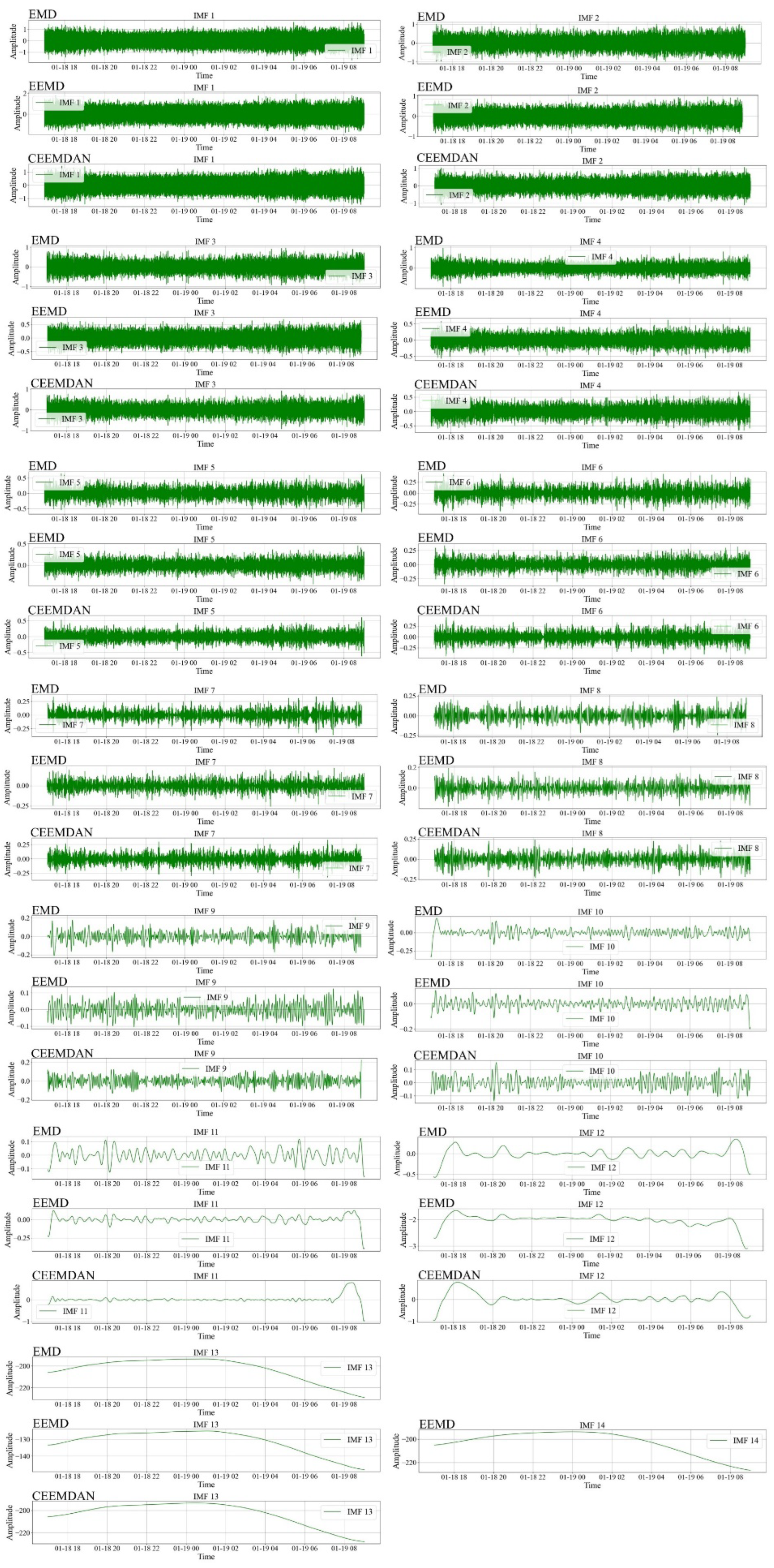

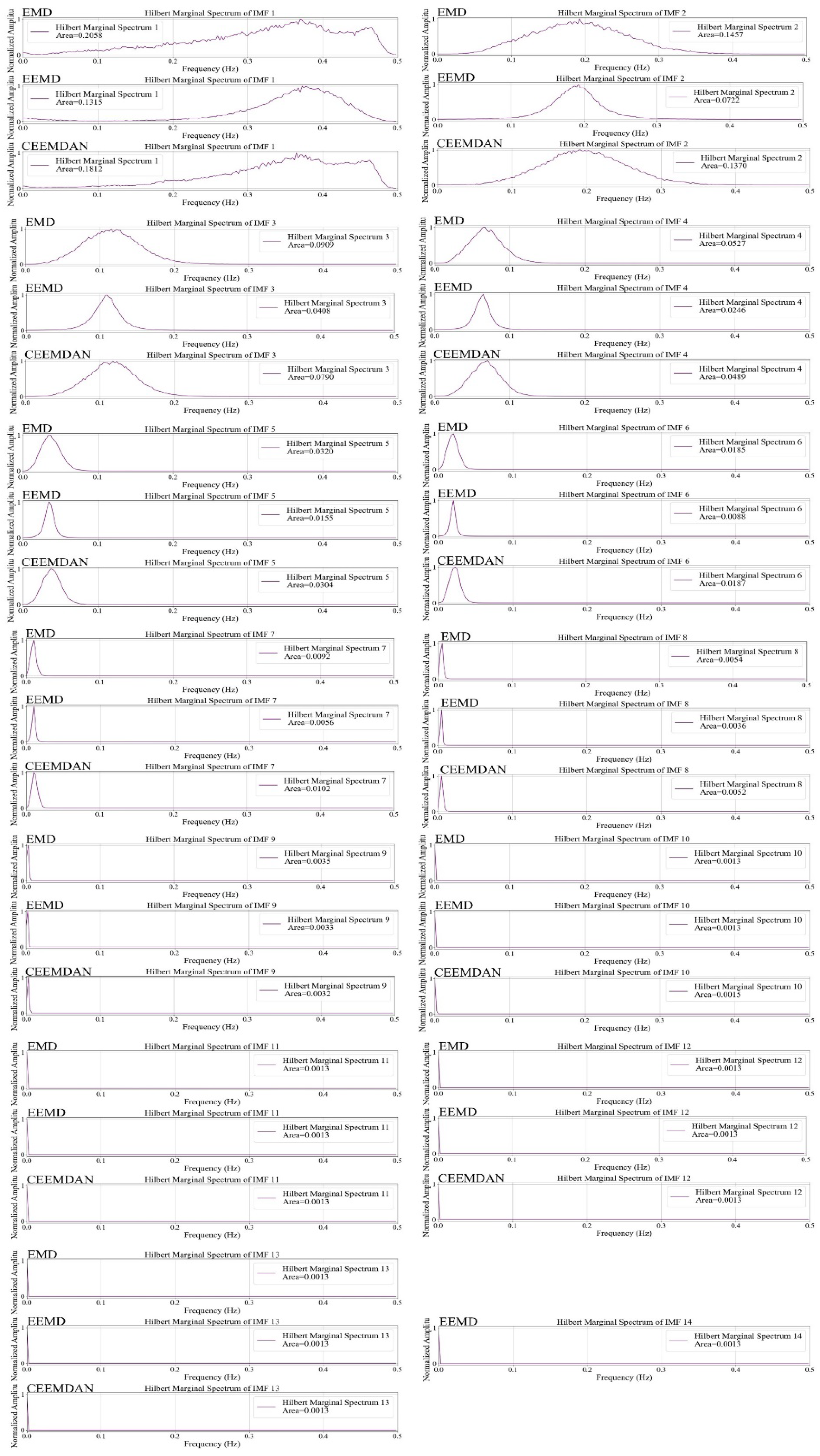

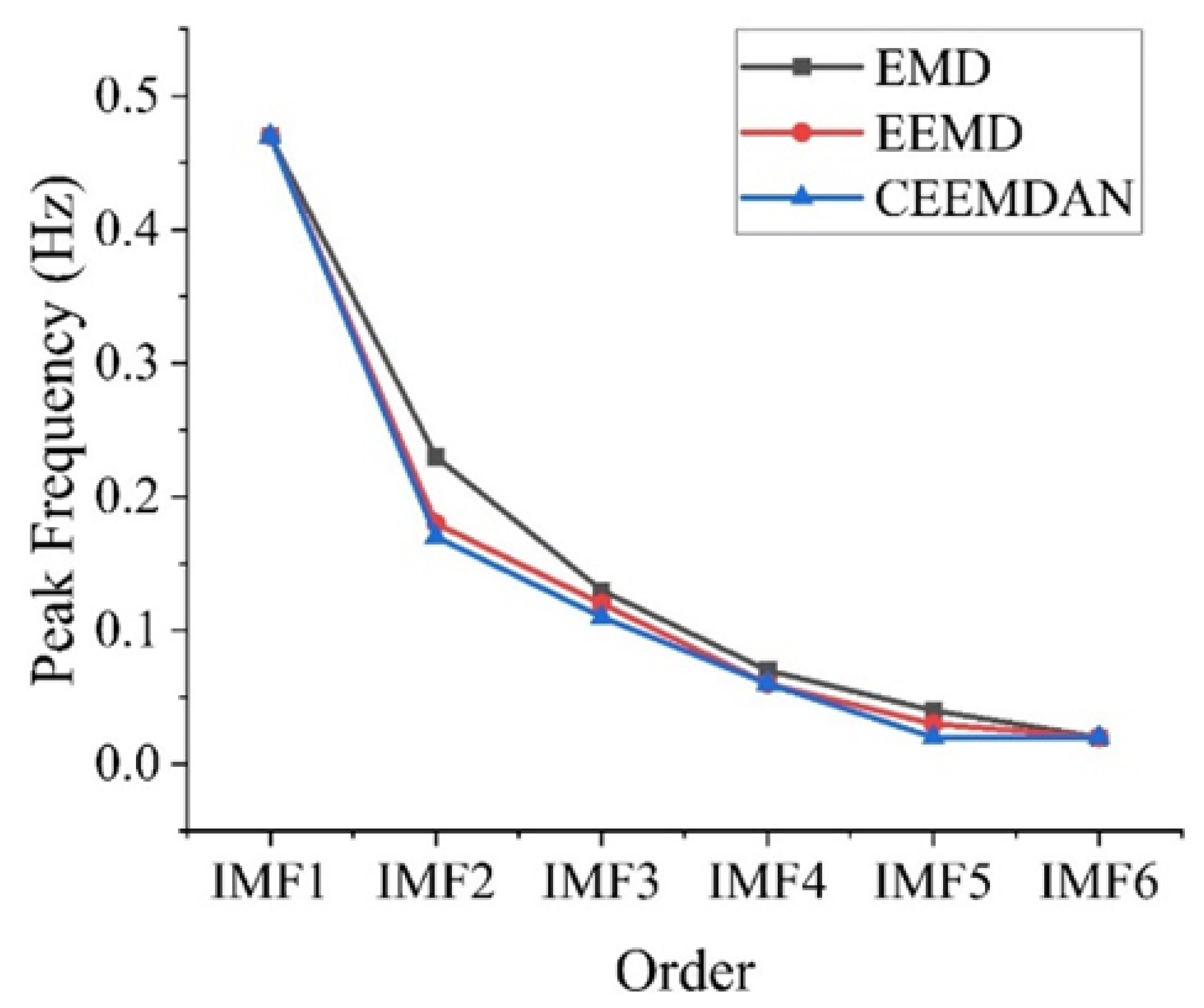

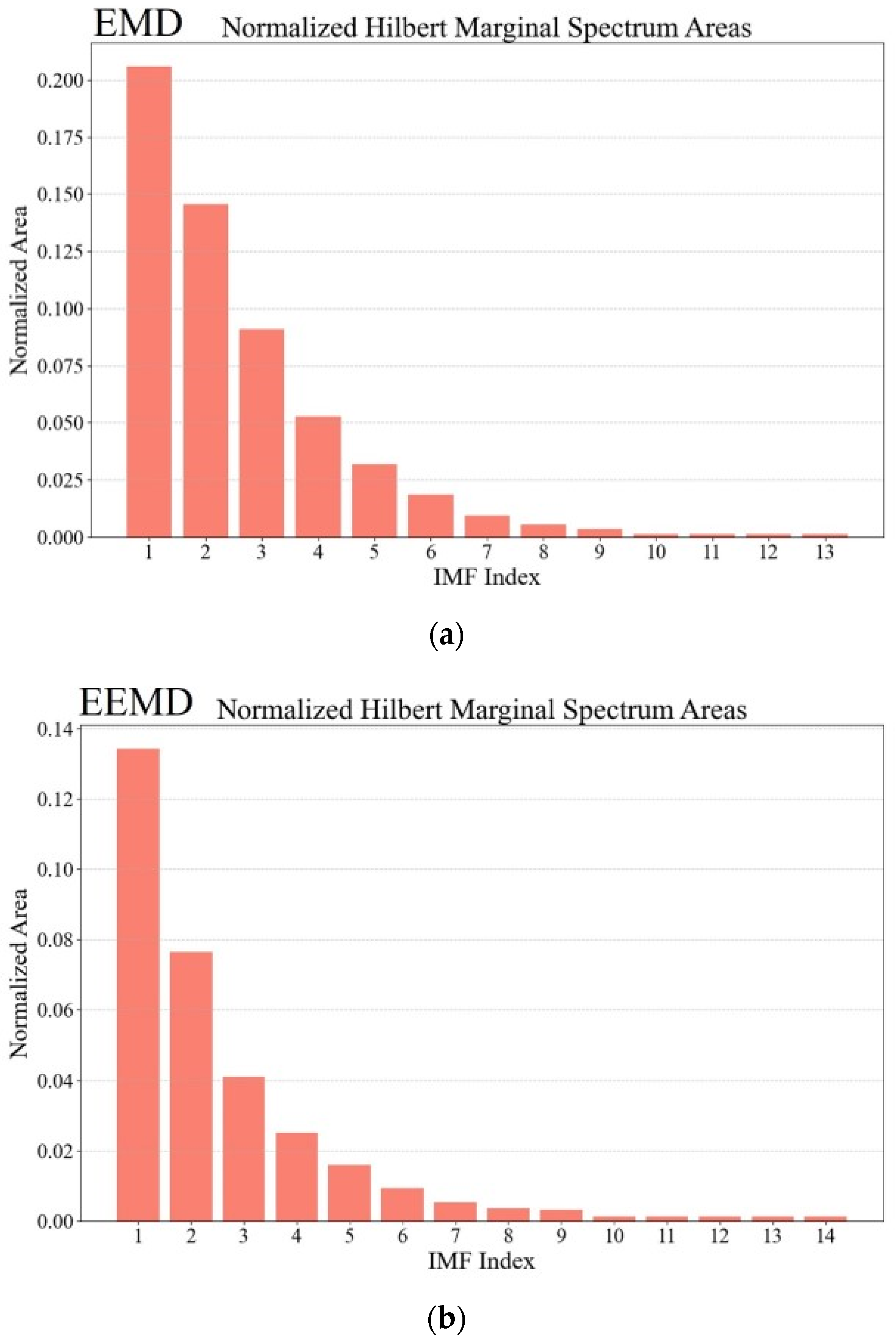

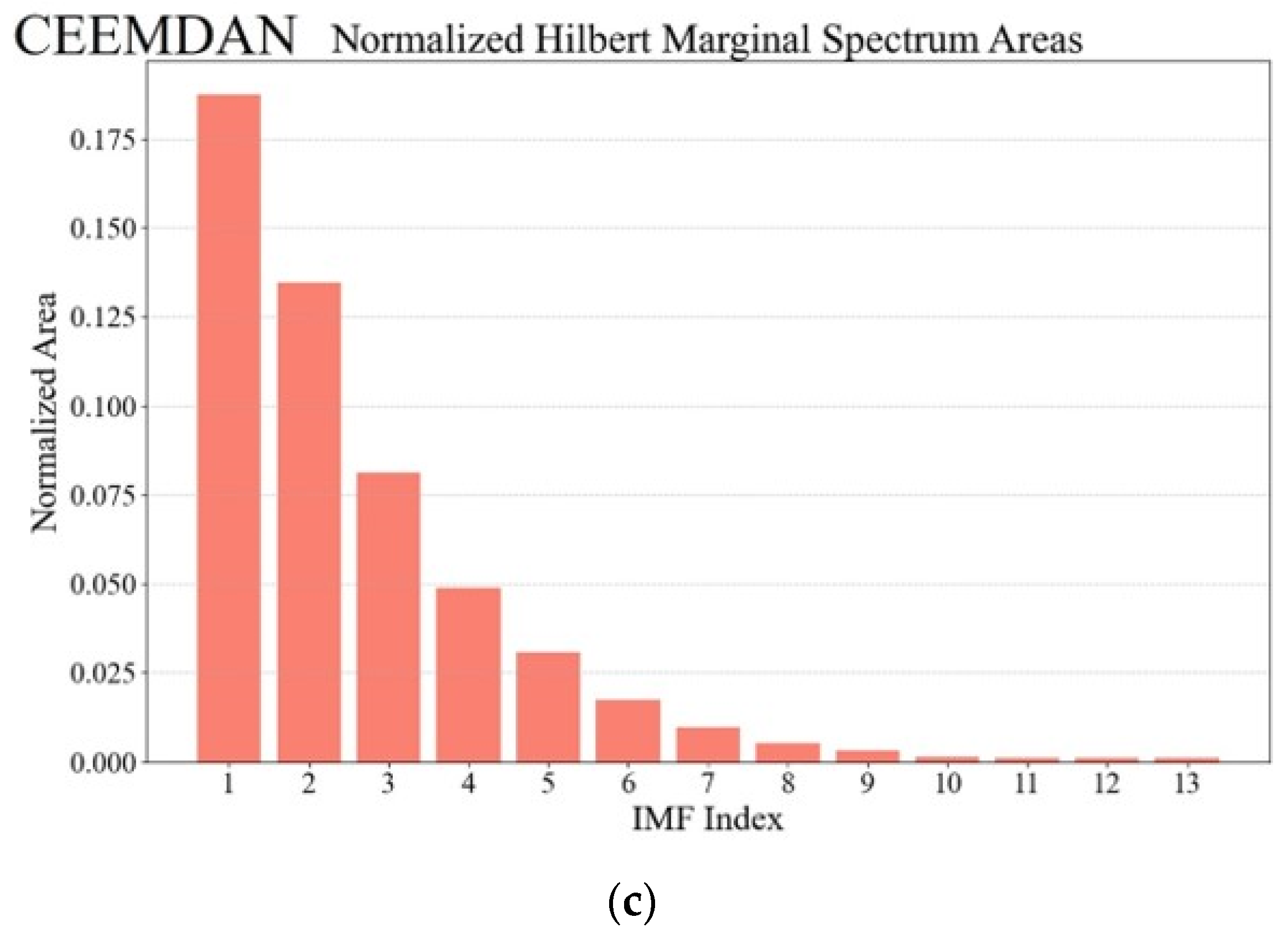

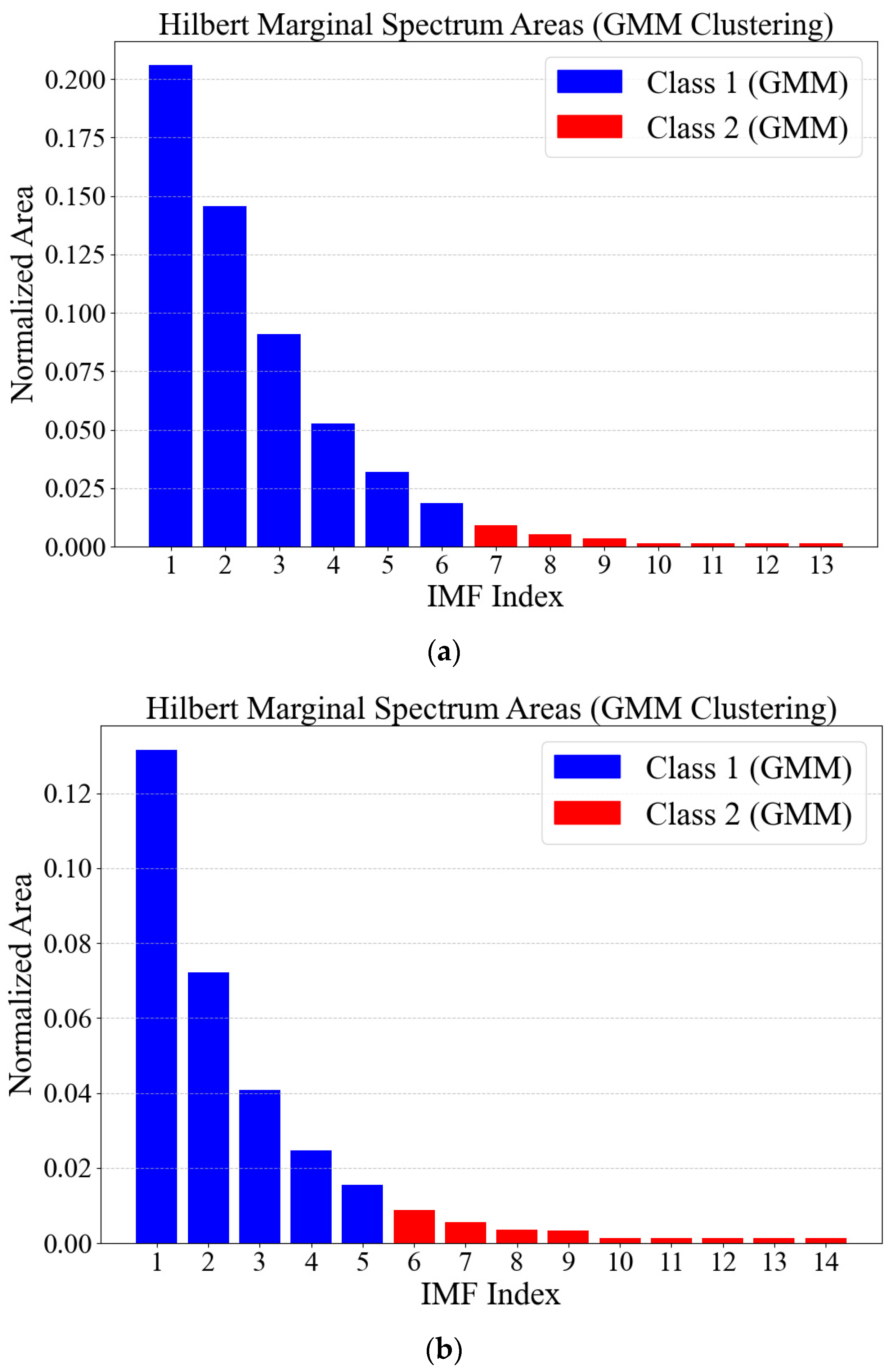

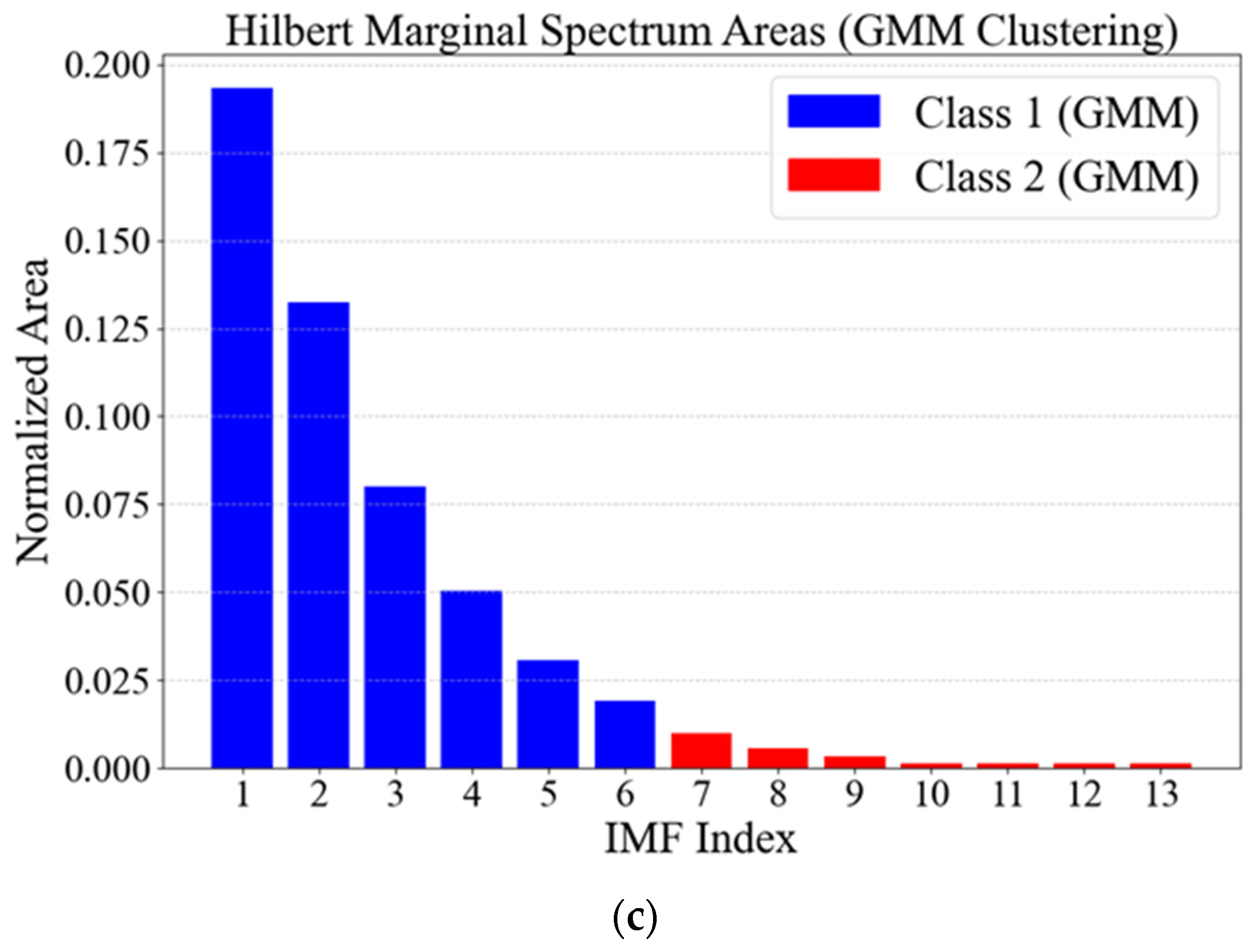

5.3. Comparison of EMD, EEMD, and CEEMDAN Methods

5.4. Result Evaluation

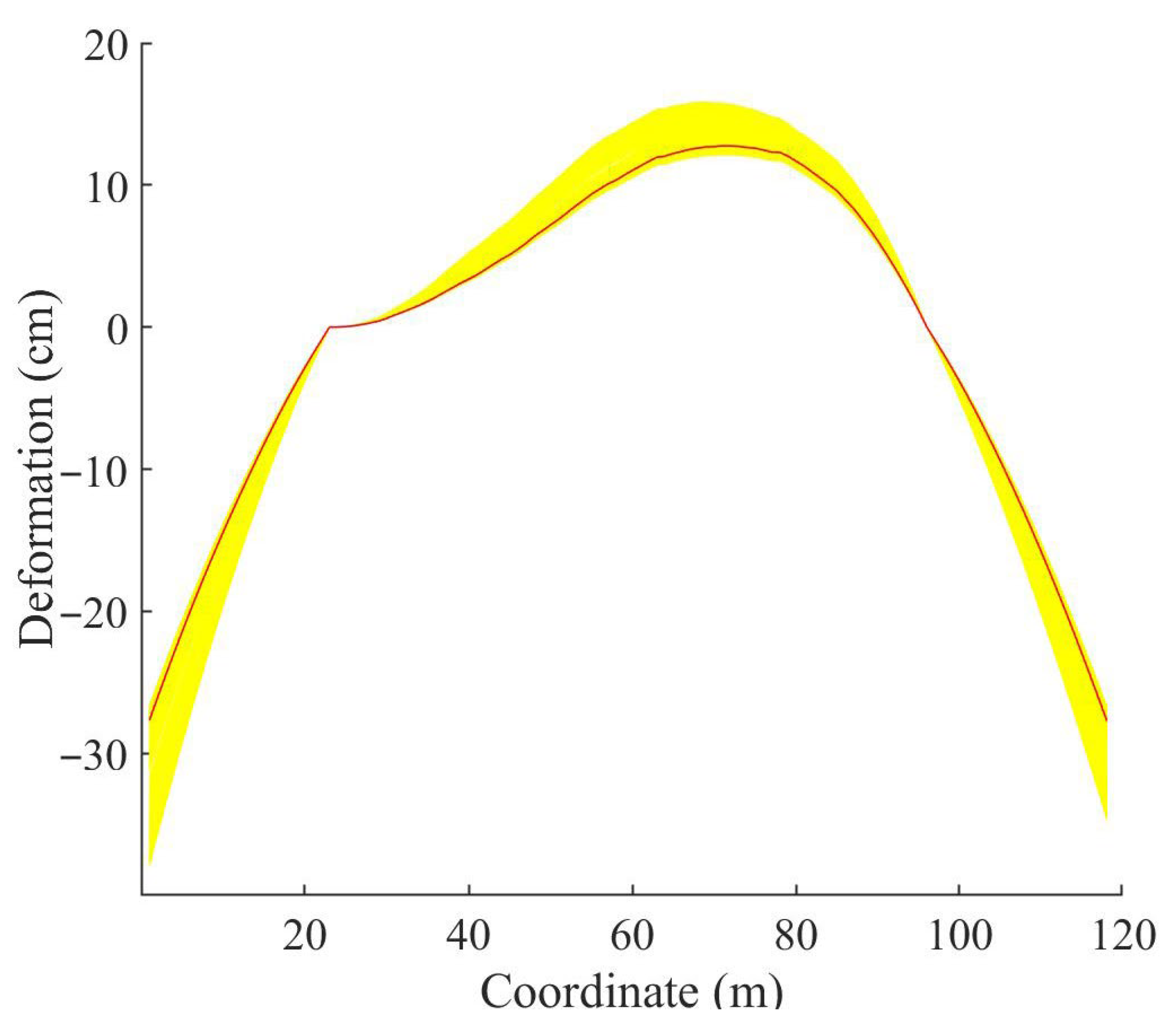

5.5. Deformation Reconstruction Based on Ko Displacement Theory

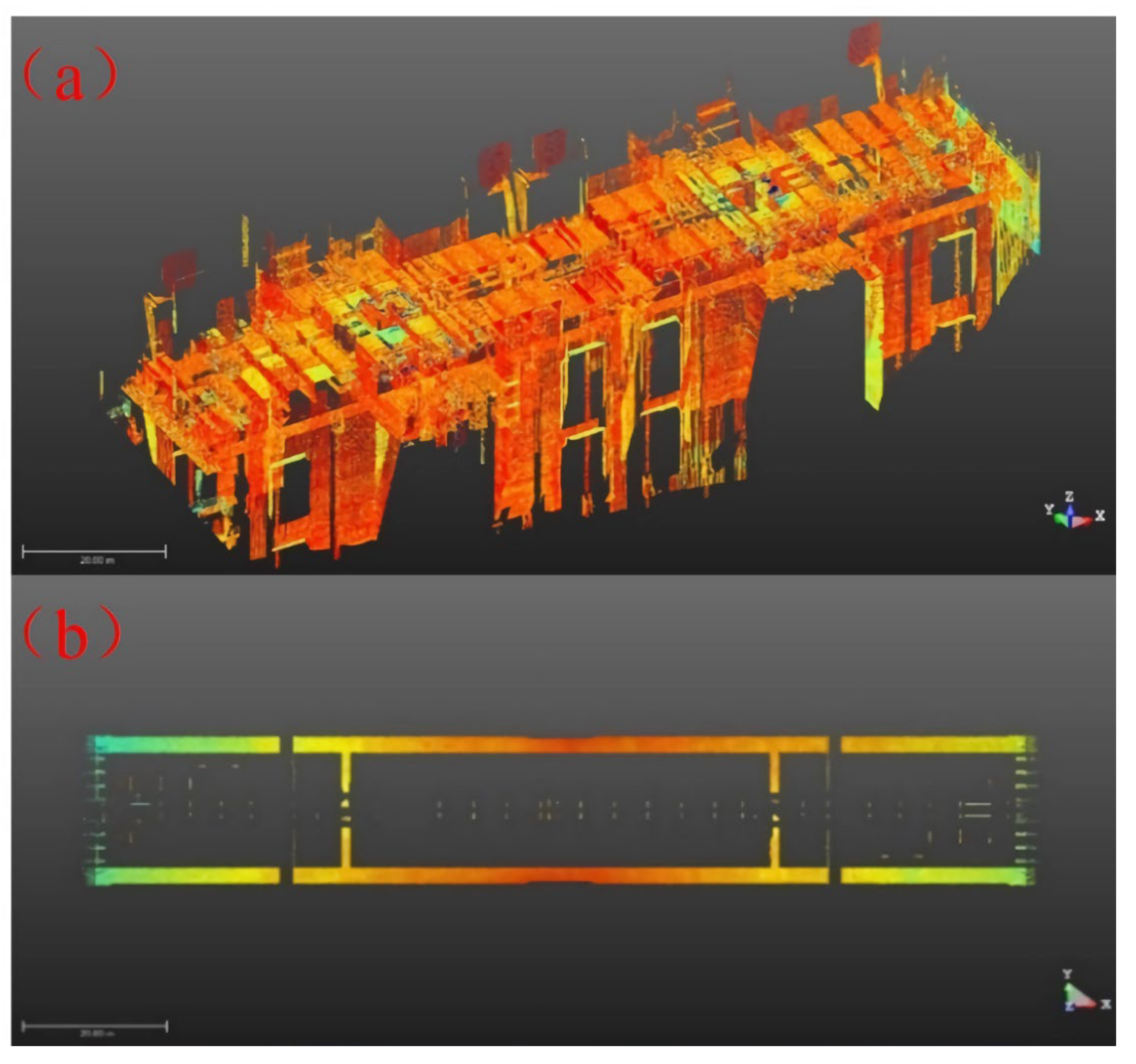

5.6. Measurement by 3D Laser Scanner

5.7. Evaluation

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foss, G.C.; Haugse, E.D. Using modal test results to develop strain to displacement transformations. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Modal Analysis, Nashvile, TN, USA, 13–16 February 1995; pp. 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.; Ding, K.; Shu, A.; Liu, Y. Study on deformation field reconstruction method of liquid storage tank based on Brillouin distributed fiber. Press. Vessel. Technol. 2021, 38, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-I.I.; Han, J.-H.; Bang, H.-J. Real-time deformed shape estimation of a wind turbine blade using distributed fiber Bragg grating sensors. Wind Energy 2014, 17, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freydin, M.; Rattner, M.K.; Raveh, D.E.; Kressel, I.; Davidi, R.; Tur, M. Fiber-Optics-Based Aeroelastic Shape Sensing. AIAA J. 2019, 57, 5094–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessler, A.; Dong, S. On a hierarchy of conforming Timoshenko beam elements. Comput. Struct. 1981, 14, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesssler, A.; Spangler, J.L. A Variational Principle for Reconstruction of Elastic Deformations in Shear Deformable Plates and Shells; NASA Formal Series Reports: Engineering; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tesssler, A.; Spangler, J.L. Inverse FEM for full-field reconstruction of elastic deformations in shear deformable plates and shells. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Munich, Germany, 7–9 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tesssler, A.; Spangler, J.L. A least-squares variational method for full-field reconstruction of elastic deformations in shear-deformable plates and shells. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkarayev, S.; Krashantisa, R.; Tessler, A. An inverse interpolation method utilizing in-flight strain measurements for determining loads and structural response of aerospace vehicles. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Stanford, CA, USA, 12–14 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shkarayev, S.; Ramsn, A.; Tessler, A. Computational experimental validation enabling a viable in-flight structural health monitoring technology. In Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Cachan, Paris, France, 10–12 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Wang, F.; Zhou, F. Optimization study of battery silo deformation monitoring deployment points. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2020, 42, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, X.; Lu, Z. Research on propeller deformation reconstruction based on FBG sensing network. Dig. Manuf. Sci. 2020, 18, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, G.; Yan, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, S. Reconstruction of propeller deformation based on FBG sensor network. Ocean Eng. 2022, 249, 110884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Wang, F.; Gao, X.; Jiang, S. Research on Deformation Reconstruction Based on Structural Curvature of CFRP Propeller With Fiber Bragg Grating Sensor Network. Photonic Sens. 2022, 12, 220412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, W.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Sui, Q. Fiber grating sensor-based morphology sensing and 3D reconstruction of slab-like structures. Chin. J. Lasers 2020, 47, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Yuan, S.; Ren, Y.; Xu, Y. Deformation reconstruction of deformed airfoil fishbone based on inverse finite element method. Acta Aeronaut Astronaut. Sin. 2020, 41, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, H.; Zhao, F. Dynamic Deformation Reconstruction of Variable Section WING with Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, W. Inverse Finite Element Method for Reconstruction of Deformation in the Gantry Structure of Heavy-Duty Machine Tool Using FBG Sensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhou, F.; Song, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, J. Deformation Reconstruction for a Heavy-Duty Machine Column Through the Inverse Finite Element Method. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 9218–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niu, S.; Bao, H.; Hu, N. Improved Adaptive Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization of Sensor Layout for Shape Sensing with Inverse Finite Element Method. Sensors 2022, 22, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Bao, H.; Xue, S.; Xu, Q. Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization of Sensor Distribution Scheme with Consideration of the Accuracy and the Robustness for Deformation Reconstruction. Sensors 2019, 19, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Cao, M.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Xu, H.; Wu, Z. Structural Damage Identification Based on Integrated Utilization of Inverse Finite Element Method and Pseudo-Excitation Approach. Sensors 2021, 21, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Yue, S.; Zhang, S.; Song, W. Strain—Deformation reconstruction of CFRP laminates based on Ko displacement theory. Nondestruct. Test. Evaluation 2021, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, G.C.; Lim, T.W.; Wiber, R.; Bosse, A.; Povich, C.; Fisher, S. Strain-based shape estimation algorithms for a cantilever beam. In Proceedings of the SPIE, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–5 March 1997; Volume 43, pp. 788–798. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, W.L.; Fleischer, V.T. Extension of Ko Straight-Beam Displacement Theory to Deformed Shape Predictions of Slender Curved Structures; NASA: Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jutte, C.V.; Ko, W.L.; Stephens, C.A.; Bakalyar, J.A.; Richards, W.L.; Parke, A.R. Deformed Shape Calculation of a Full-Scale Wing Using Fiber Optic strain DATA From a Ground Loads Test; NASA: Silicon Valley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, C.-G.; Truax, R.A. Acceleration and Velocity Sensing from Measured Strain; AIAA Infotech @ Aerospace: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; p. 1229. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, M.; Gherlone, M. Composite wing box deformed-shape reconstruction based on measured strains: Optimization and comparison of existing approaches. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 105758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wu, S.; Dong, E. Real-time reconstruction of displacement fields of typical thermal protection structures based on measured strains. J. Southeast Univ. 2021, 51, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Wang, D. A study on deformation estimation combining OFDR and Ko displacement theory. Opt. Commun. Technol. 2021, 45, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, C. Degradation assessment of bearings with trend-reconstruct-based features selection and gated recurrent unit network. Measurement 2020, 165, 108064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, R.; Kaddour, A.; Bendiabdellah, A.; Derouiche, Z. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis based on an Im-proved Denoising Method Using the Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition and the Optimized Thresholding Operation. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 7166–7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Xiao, J.; Li, C.; Xu, Z.; Yue, M. Fault diagnosis of rolling bearing using CNN and PCA fractal-based feature extraction. Measurement 2023, 223, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shao, Y. Fault feature extraction of rotating machinery using a reweighted complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise and demodulation analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 138, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Li, R.; Zhou, T.; Su, C. Fault feature extraction method for rotating machinery based on a CEEMDAN-LPP algorithm and synthetic maximum index. Measurement 2022, 189, 110636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Liu, L. Vibration signal denoising method based on CEEMDAN and its application in brake disc unbalance detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 187, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Ma, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, M.; Chen, X. A Study of Fault Signal Noise Reduction Based on Improved CEEMDAN-SVD. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Hu, M.; Jiang, A.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Hao, G. An Adaptive CEEMDAN Thresholding Denoising Method Optimized by Nonlocal Means Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 29, 6891–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, K.; Cheng, P. Fiber optic gyro noise reduction based on hybrid CEEMDAN-LWT method. Measurement 2020, 161, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hou, J.; Li, T.; Wen, G.; Jia, D.; Liu, T. Polarization characteristic parameters measurement of Y-waveguide multi-function integrated optic circuit based on noise reduction processing. Opt. Commun. 2024, 561, 130540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y. Seismic exploration desert noise suppression based on complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise. J. Appl. Geophys. 2020, 180, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L. Beam deformation reconstruction based on Ko displacement theory. Measurement 2024, 238, 115324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Machine Learning; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

| EMD | Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Area | 0.2058 | 0.1457 | 0.0909 | 0.0527 | 0.0320 | 0.0185 | 0.0092 | |

| Order | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

| Area | 0.0054 | 0.0035 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | ||

| EEMD | Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Area | 0.1315 | 0.0772 | 0.0408 | 0.0246 | 0.0155 | 0.0088 | 0.0056 | |

| Order | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| Area | 0.0036 | 0.0033 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | |

| CEEMDAN | Order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Area | 0.1812 | 0.1370 | 0.0790 | 0.0489 | 0.0304 | 0.0187 | 0.0102 | |

| Order | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

| Area | 0.0052 | 0.0032 | 0.0015 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 | 0.0013 |

| Coordinate Points | 8 | 21 | 34 | 47 | 60 | 73 | 86 | 99 | 112 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deformation (cm) | −18.7957 | −2.8838 | 1.3480 | 5.6101 | 10.7843 | 12.7797 | 9.6740 | −1.8800 | −17.4621 |

| Coordinate Points (m) | 8 | 21 | 34 | 47 | 60 | 73 | 86 | 99 | 112 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deformation value (cm) | −17.80 | −2.72 | 1.29 | 5.37 | 10.34 | 12.31 | 9.26 | −1.79 | −16.69 |

| Coordinate Points (m) | 8 | 21 | 34 | 47 | 60 | 73 | 86 | 99 | 112 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute error (cm) | 0.9957 | 0.1638 | 0.058 | 0.2401 | 0.4443 | 0.4697 | 0.4140 | 0.09 | 0.7721 |

| Relative error | 5.30% | 5.68% | 4.30% | 4.28% | 4.12% | 3.68% | 4.30% | 4.79% | 4.42% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xing, S.; Zhou, X. A Methodology for Beam Deformation Reconstruction Utilizing CEEMDAN-HT-GMM-Ko. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010349

Xing S, Zhou X. A Methodology for Beam Deformation Reconstruction Utilizing CEEMDAN-HT-GMM-Ko. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):349. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010349

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Shaopeng, and Xincong Zhou. 2026. "A Methodology for Beam Deformation Reconstruction Utilizing CEEMDAN-HT-GMM-Ko" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010349

APA StyleXing, S., & Zhou, X. (2026). A Methodology for Beam Deformation Reconstruction Utilizing CEEMDAN-HT-GMM-Ko. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 349. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010349