Swirl Flame Stability for Hydrogen-Enhanced LPG Combustion in a Low-Swirl Burner: Experimental Investigation

Abstract

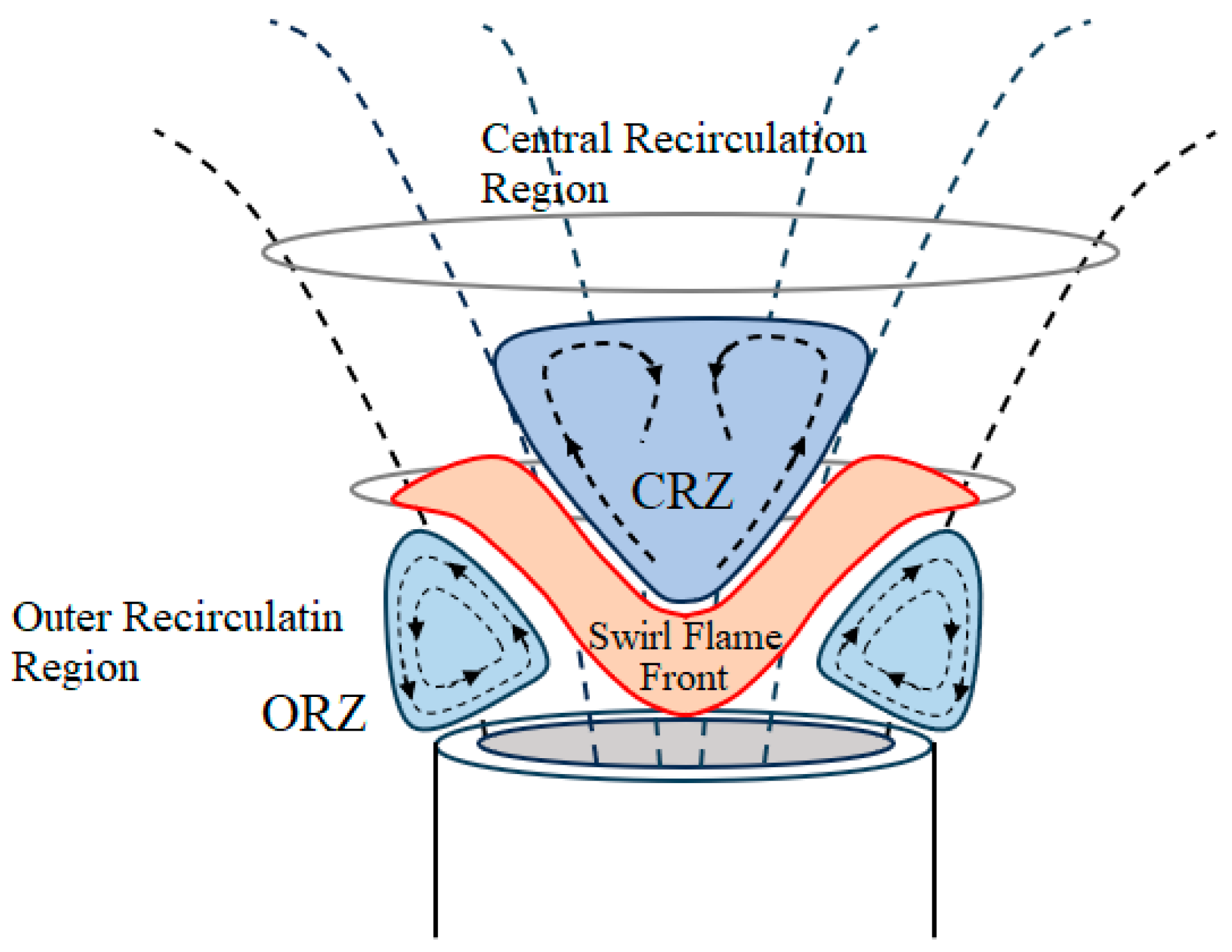

1. Introduction

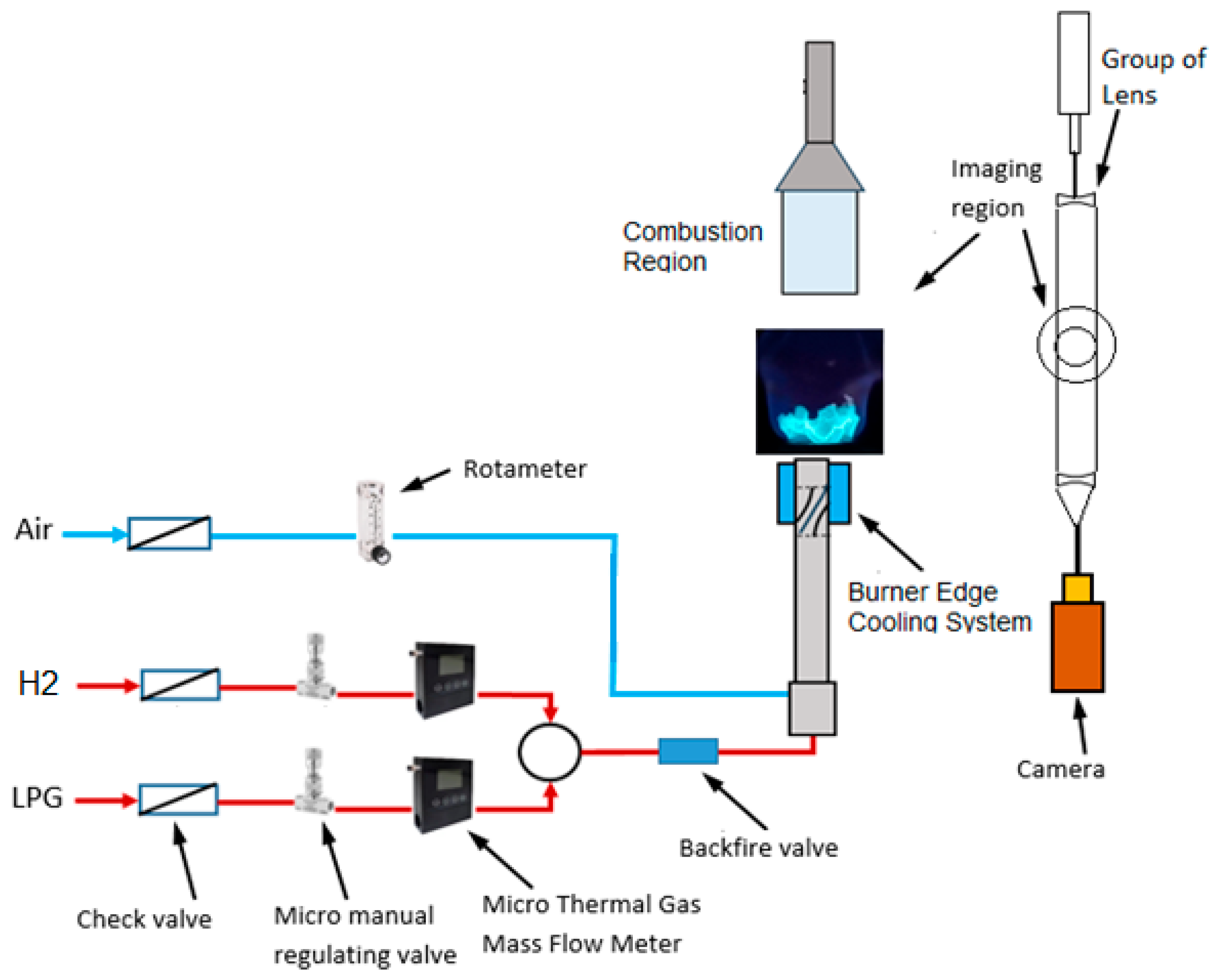

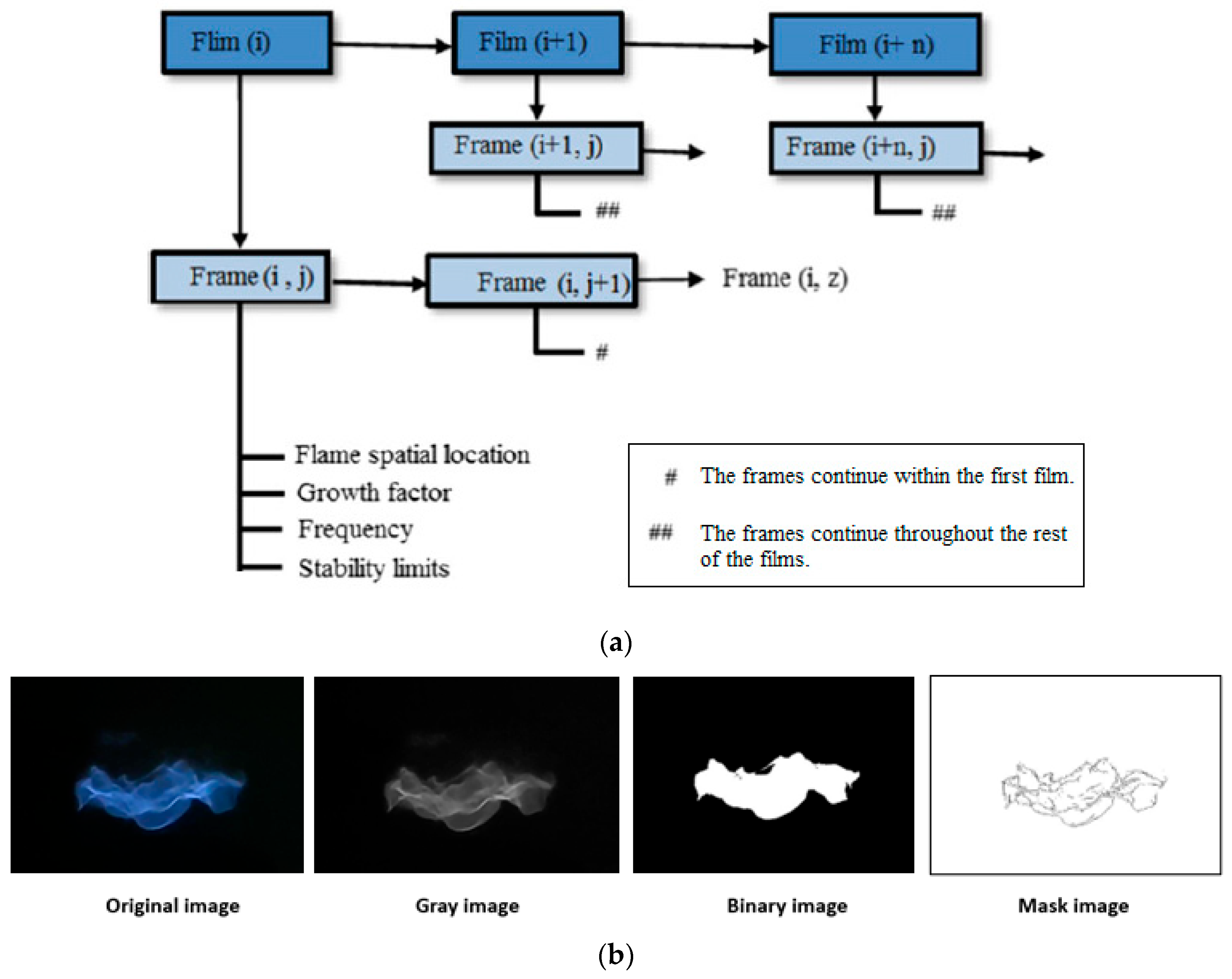

2. Experimental Setup

Uncertainty Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

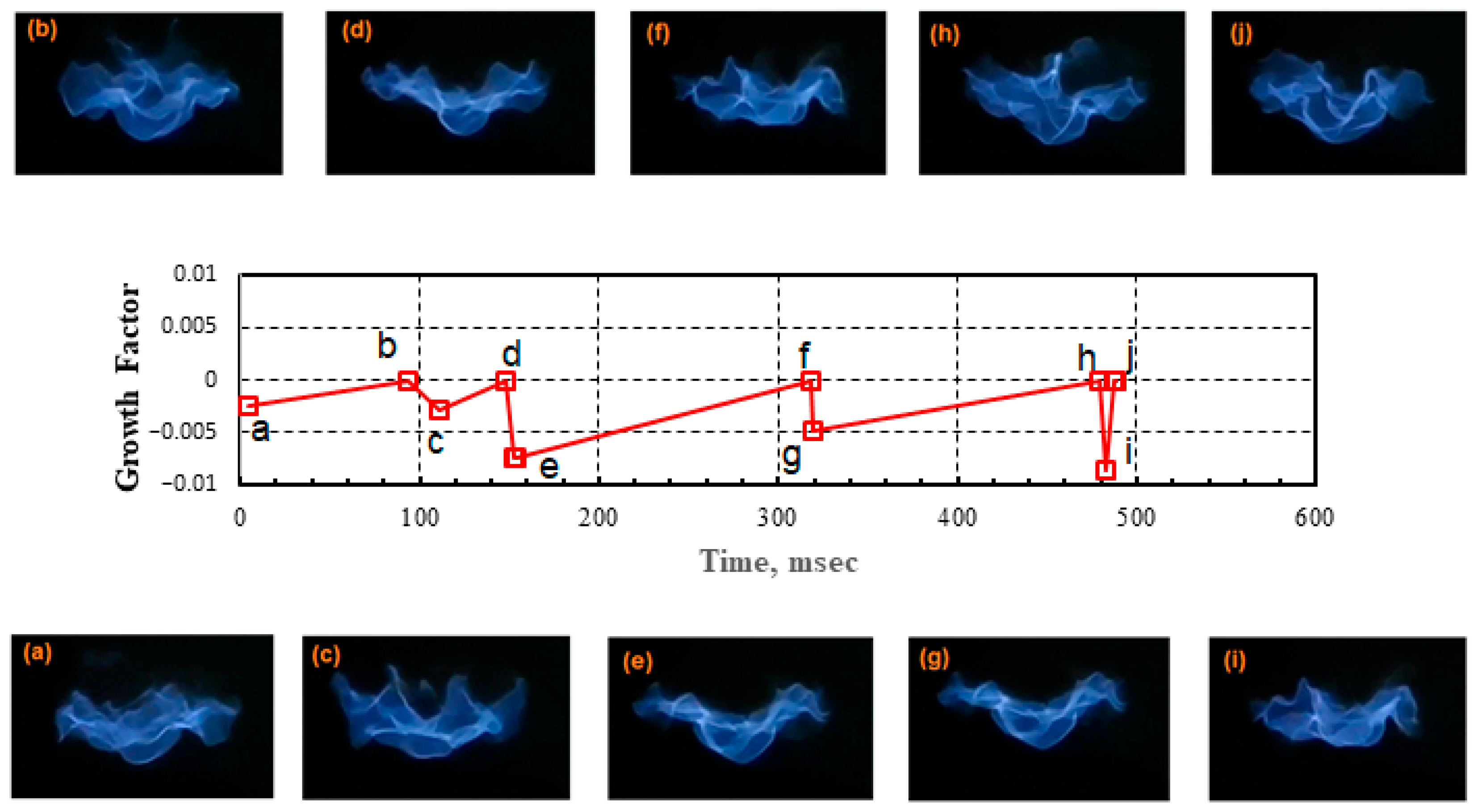

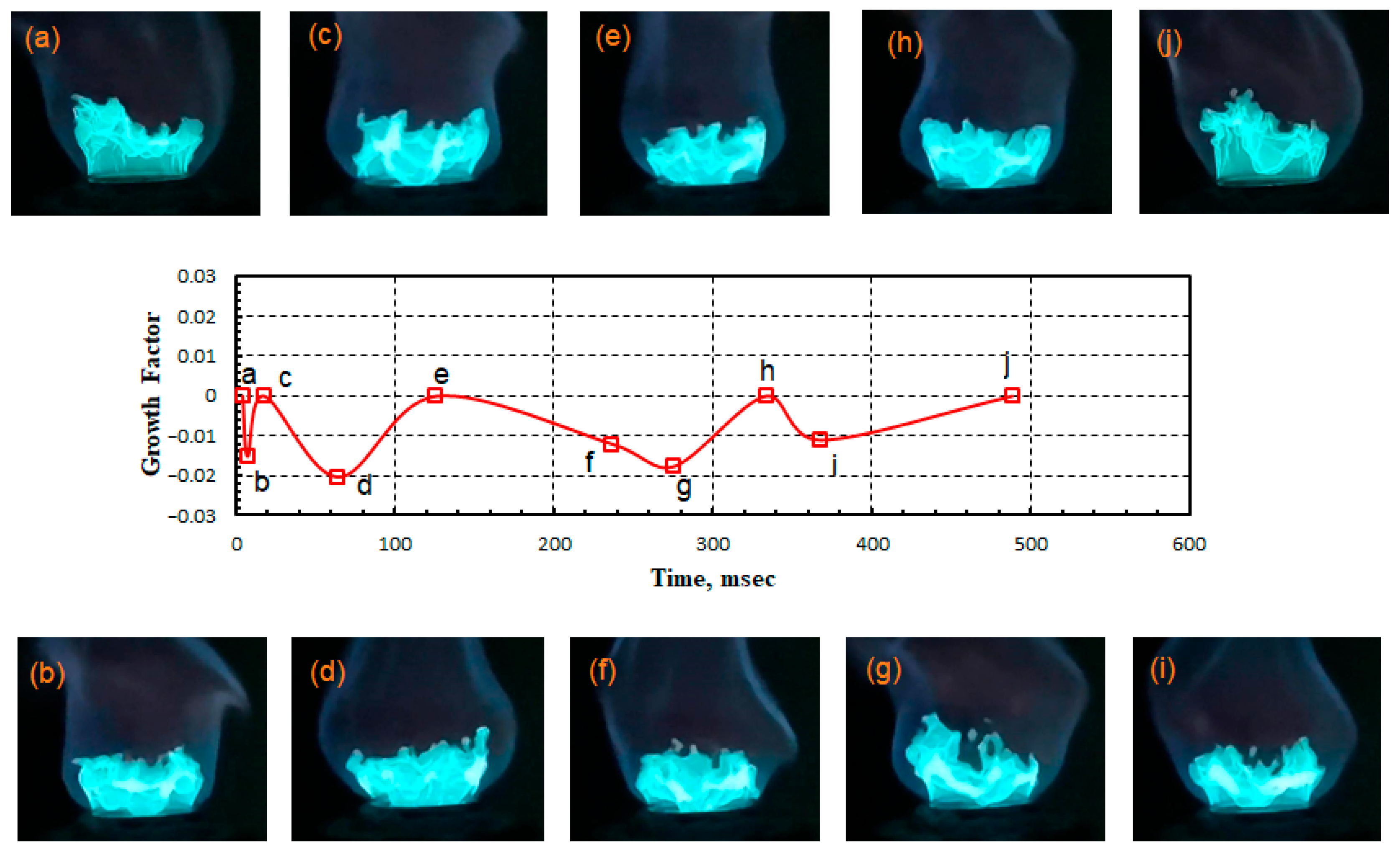

3.1. Dynamics of Swirl Flame for LPG

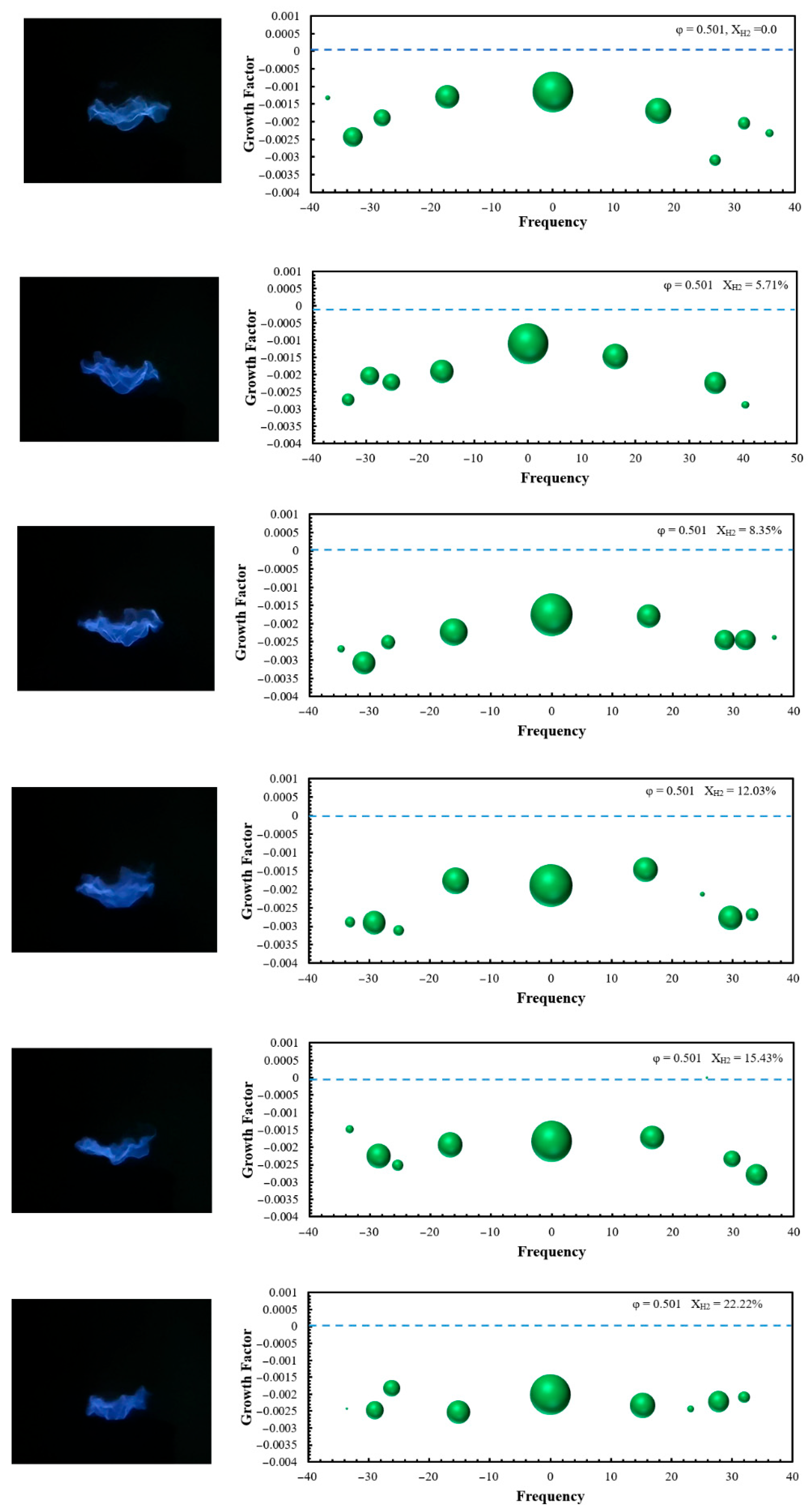

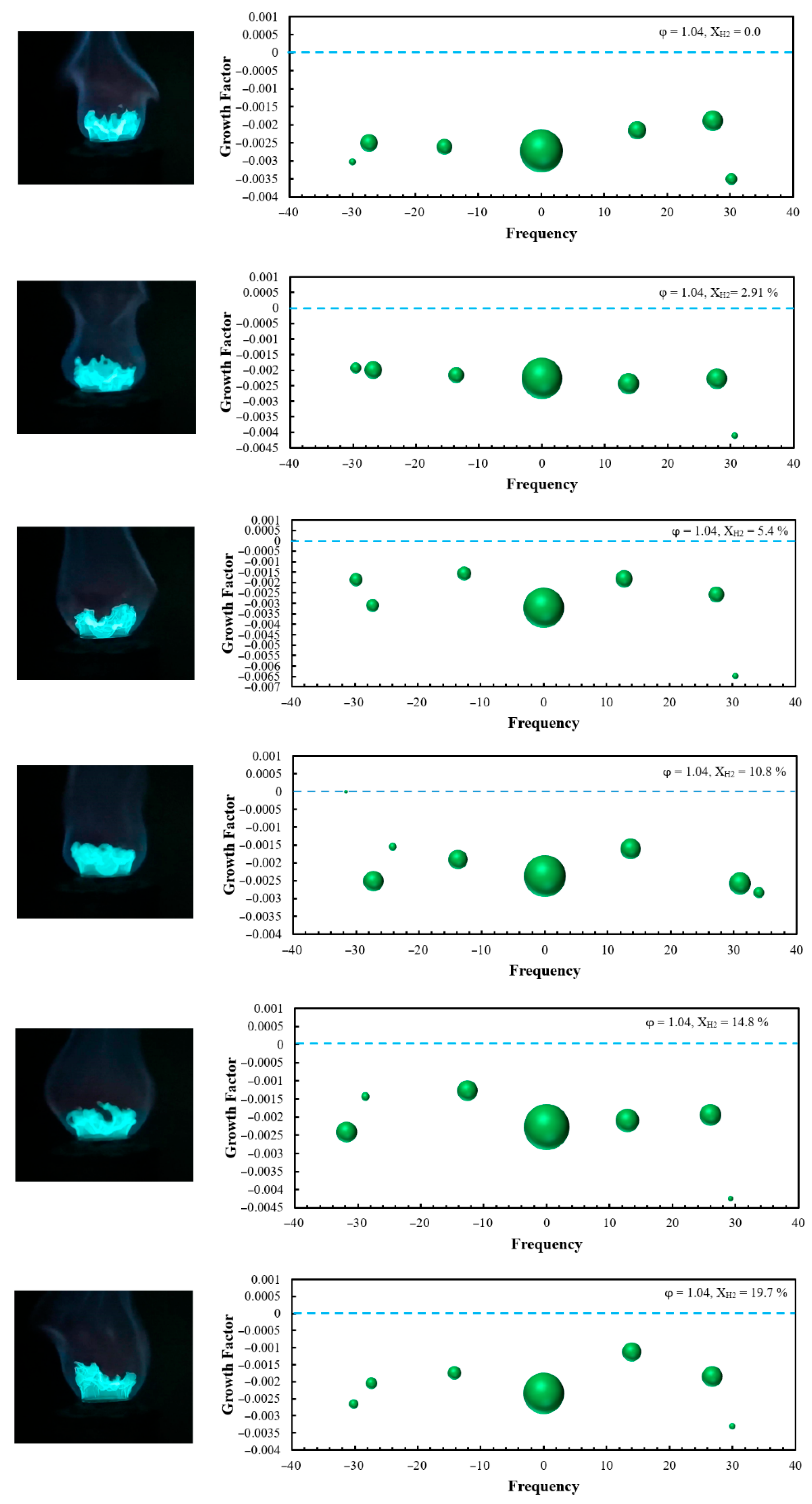

3.2. Dynamics of Swirl Flame for Enriched LPG with H2

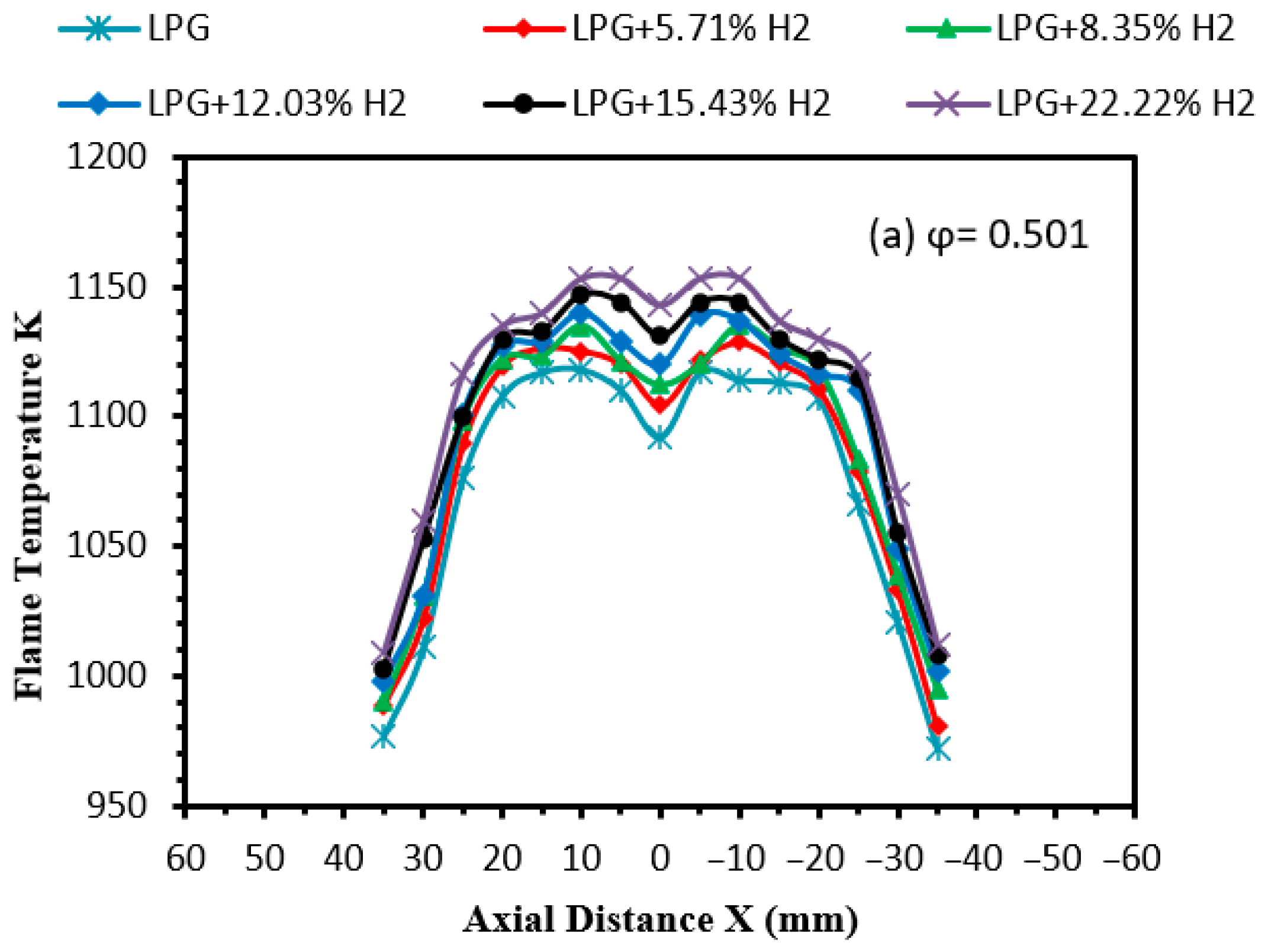

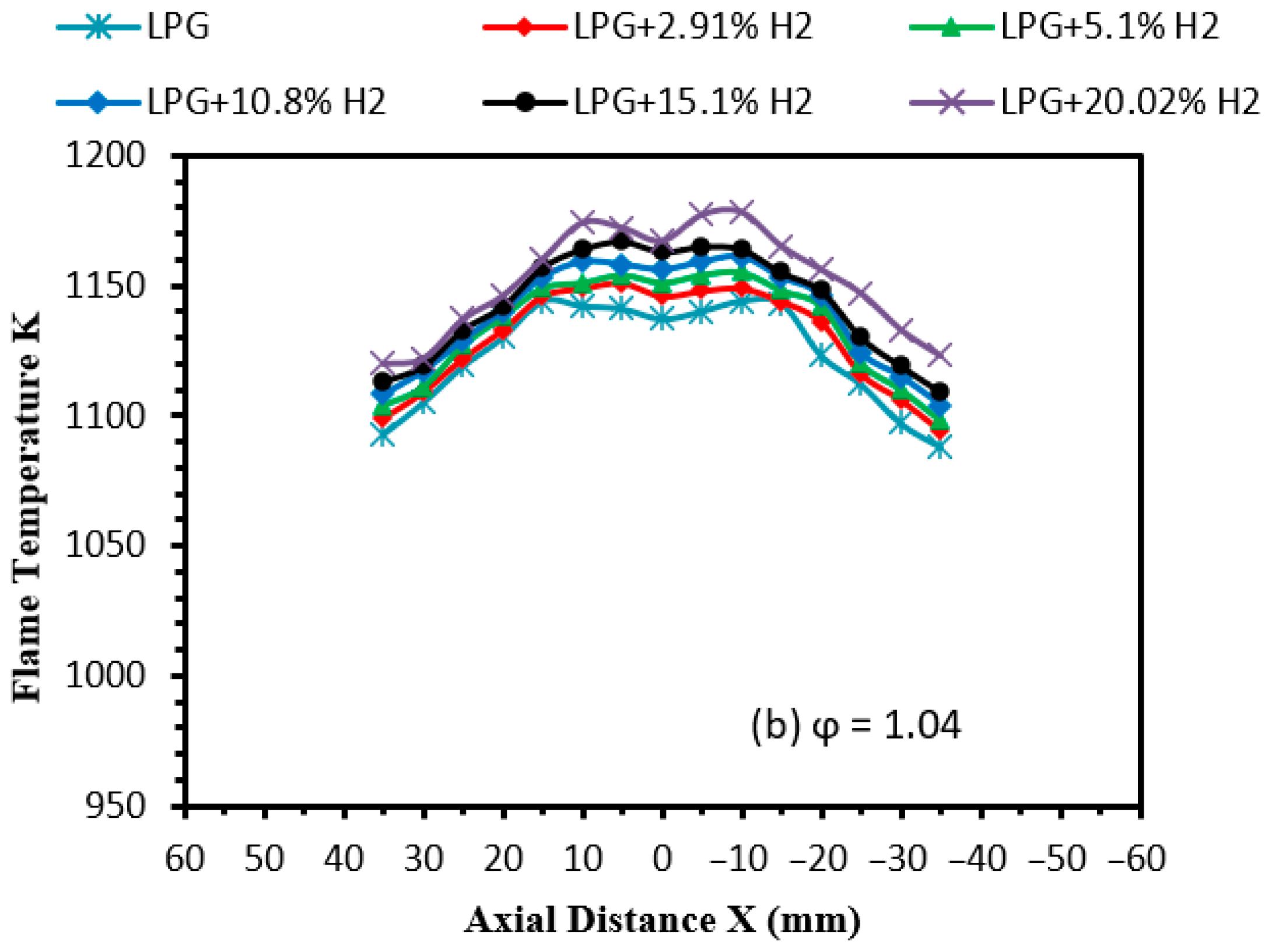

3.3. Temperature Distribution in the Swirl Flame

4. Conclusions

- ▪

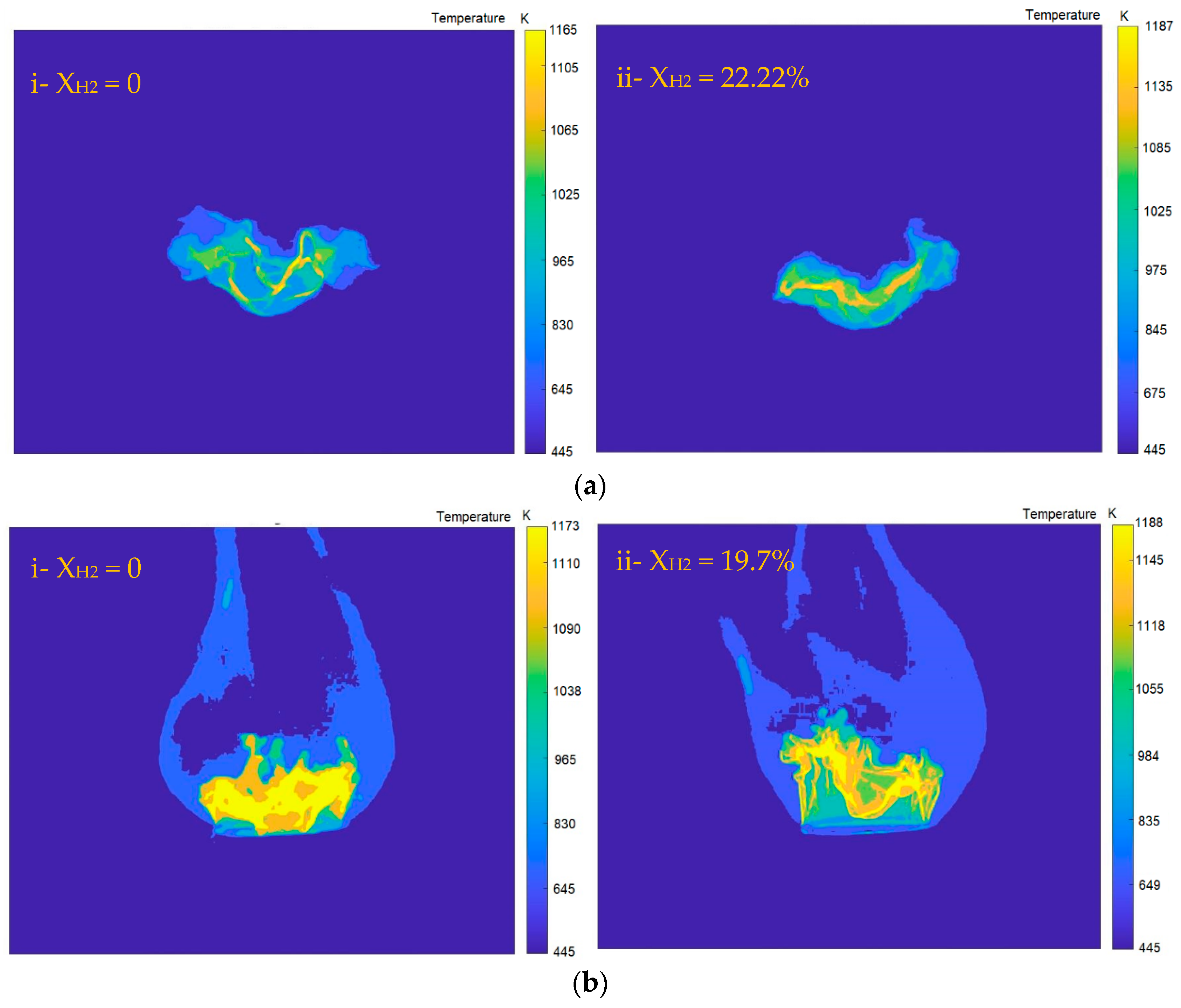

- The hydrogen addition enhances the intensity of chemical reactions per unit volume within the swirl flame front. This leads to a more compact flame structure, changing its shape and reducing its overall size.

- ▪

- The results show that the growth factor changes in an oscillating manner. This behavior reflects a sensitive balance between airflow mixing and chemical reaction rates under lean mixture conditions (φ = 0.501). The findings also indicate that an equivalence ratio of 1.04 provides a practical compromise, offering sufficient flame speed while still benefiting from the stabilizing effects of the swirling flow.

- ▪

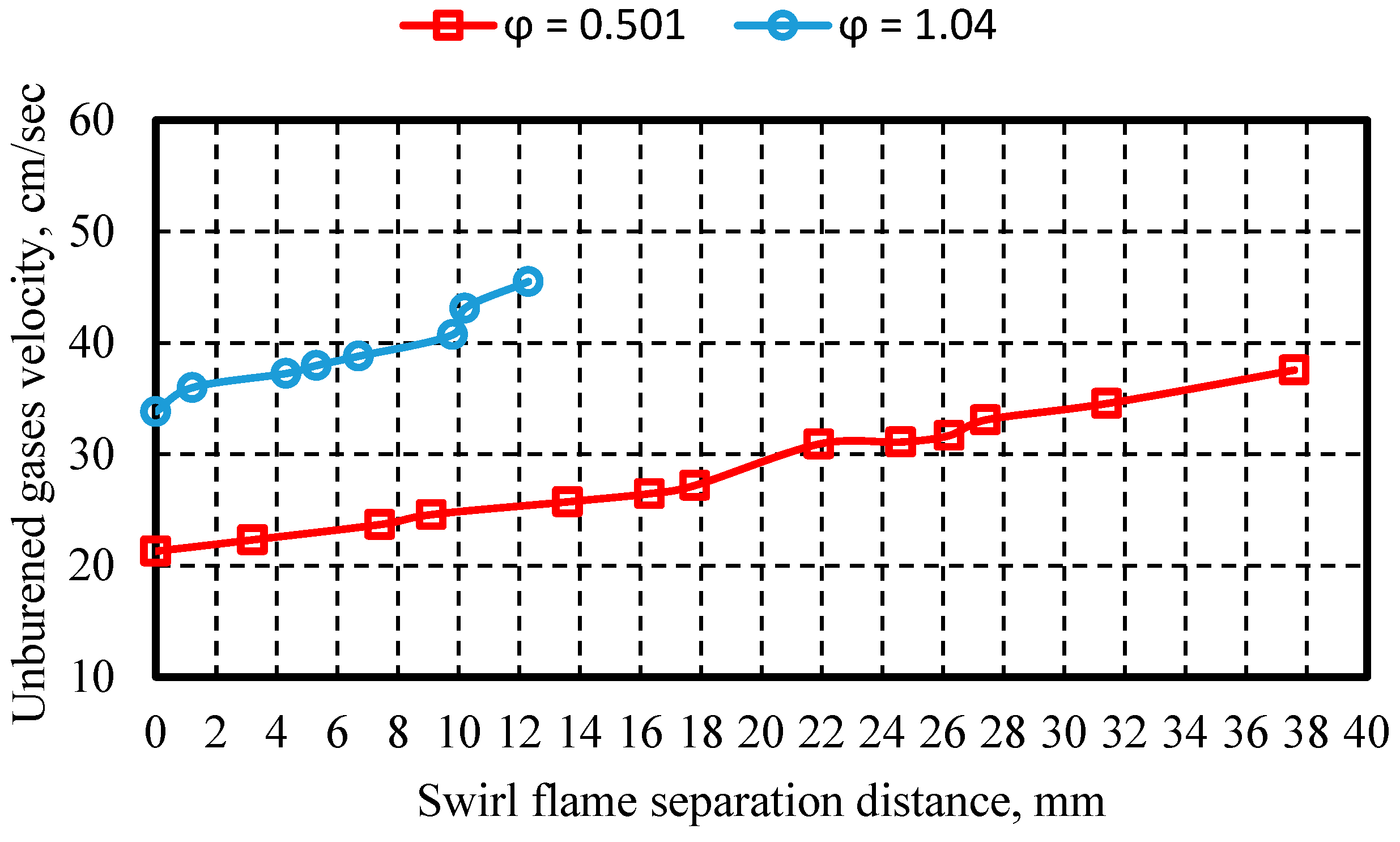

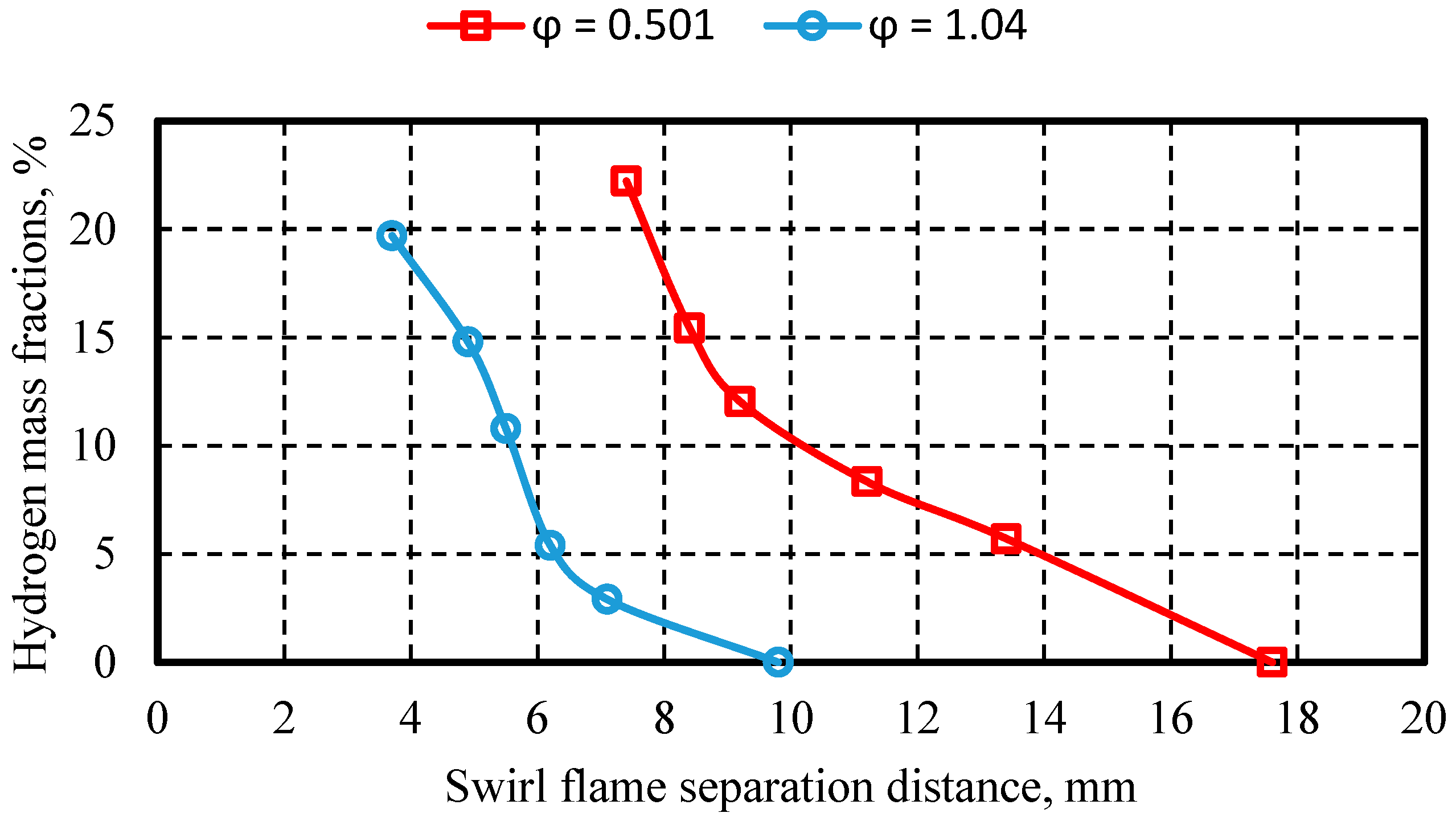

- The findings are that, as the unburned gas velocity increases, the separation distance from the burner increases slowly at φ = 0.501, whereas at φ = 1.04, the separation distance shortens. While hydrogen enrichment of LPG in a swirl burner generally reduces the flame separation distance at the burner edge, resulting in a more compact, stable, and anchored flame.

- ▪

- The analysis highlights that hydrogen enrichment up to ~20% enhances flame compactness, intensifies heat release, and sustains stability without triggering blow-off or flashback, making hydrogen blending a promising strategy for stabilizing swirl flames at rich operating conditions.

- ▪

- Hydrogen enrichment consistently increases swirl flame temperature, but the effect is more pronounced under lean swirl flames. At φ = 0.501, the addition of 5.71–22.22% H2 results in an increase in peak flame temperature of approximately 1.1–4.3% in the CRZ. While at φ = 1.04, the addition of 2.91–20.02% H2 results in an increase in peak flame temperature of approximately 0.53–3.14% in the CRZ. So, lean mixtures benefit more from hydrogen, as it counteracts the lower flame speed and prevents potential blow-off. While slightly rich mixtures show improved temperature uniformity and slight peak enhancement, which may enhance combustion efficiency.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdul Wahhab, H.A. Influence of Swirl Flow Pattern in Single Tube Burner on Turbulent Flame Blow-Off Limit. In ICPER 2020: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Production, Energy and Reliability; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Herff, S.; Pausch, K.; Loosen, S.; Schröder, W. Impact of non-symmetric confinement on the flame dynamics of a lean-premixed swirl flame. Combust. Flame 2022, 235, 111701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, R.M.; Akroot, A.; Abdul Wahhab, H.A.; Alhamd, A.E.J.; Hamzah, A.H.; Bdaiwi, M. The Influence of Gas Fuel Enrichment with Hydrogen on the Combustion Characteristics of Combustors: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, R.M.; Akroot, A.; Abdul Wahhab, H.A. Flame Evolution Characteristics for Hydrogen/LPG Co-Combustion in a Counter-Burner. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöhr, M.; Boxx, I.; Carter, C.; Meier, W. Dynamics of lean blowout of a swirl-stabilized flame in a gas turbine model combustor. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 2953–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, B.; Fang, A.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, X. Analyzing lean blow-off limits of gas turbine combustors based on local and global Damköhler number of reaction zone. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhao, D.; Chen, Y.; Ma, G.; Wan, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, J. Blow-off characteristics of a premixed methane/air flame response to acoustic disturbances in a longitudinal combustor. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 107003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, Z.; Aouissi, M.; Boushaki, T. A Numerical Study of Swirl Effects on the Flow and Flame Dynamics in a Lean Premixed Combustor. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2016, 34, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Choi, K.W.; Kang, D.W.; Muhammad, H.A.; Lee, Y.D. Experimental investigation of combustion characteristics of a CH4/O2 premixed flame: Effect of swirl intensity on flame structure, flame stability, and emissions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 55, 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, V. Effect of swirl on combustion dynamics in a lean-premixed swirl-stabilized combustor. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2005, 30, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsada, M.; Griffiths, A.; Syred, N.; Morris, S.; Bowen, P. Effect of Swirl Number and fuel type upon the combustion limits in Swirl Combustors. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 Turbo Expo: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–10 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, A.S.; Saleh, F.A. Study of the Impact of LPG Composition on the Blowoff and Flashback Limits of a Premixed Flame in a Swirl Burner. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2024, 17, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellan, D.; Balusamy, S. Turbulent Premixed LPG/air Flames Structures in Double Swirl Burner. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA & Virtual, 3–7 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, C.; Menon, S. Swirl control of combustion instabilities in a gas turbine combustor. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2002, 29, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacleto, P.M.; Fernandes, E.C.; Heitor, M.V.; Shtork, S.I. Swirl flow structure and flame characteristics in a model lean premixed combustor. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2003, 175, 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafra, M.R.; Fassani, F.L.; Zanoelo, E.F.; Bizzo, W.A. Influence of swirl number and fuel equivalence ratio on NO emission in an experimental LPG-fired chamber. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2010, 30, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, M.B.; Gupta, A.K. Twin-fluid atomization and novel lifted swirl-stabilized spray flames. J. Propuls. Power 2009, 25, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I. Effect of swirl number on combustion characteristics in a natural gas diffusion flame. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2013, 135, 042204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J.M.; Lin, C.A. Reynolds stress modelling of jet and swirl interaction inside a gas turbine combustor. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 1999, 29, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilares, L. Numerical Simulation of the Dynamics of Turbulent Swirling Flames. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, München, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdeli, Y.M.; Masri, A.R. Stability characteristics and flow fields of turbulent non-premixed swirling flames. Combust. Theory Model. 2003, 7, 731–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellan, D.; Balusamy, S. Topology of turbulent premixed and stratified LPG/air flames. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 107253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellan, D.; Balusamy, S. Experimental study of swirl-stabilized turbulent premixed and stratified LPG/air flames using optical diagnostics. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2021, 121, 110281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taamallah, S.; Dagan, Y.; Chakroun, N.; Shanbhogue, S.J.; Vogiatzaki, K.; Ghoniem, A.F. Helical vortex core dynamics and flame interaction in turbulent premixed swirl combustion: A combined experimental and large eddy simulation investigation. Phys. Fluids 2019, 31, 025108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostiyarov, A.M.; Umyshev, D.R.; Kibarin, A.A.; Yamanbekova, A.K.; Tumanov, M.E.; Koldassova, G.A.; Anuarbekov, M.A. Experimental Investigation of Non-Premixed Combustion Process in a Swirl Burner with LPG and Hydrogen Mixture. Energies 2024, 17, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, P.W.; Laera, D.; Chterev, I.; Boxx, I.; Gicquel, L.; Poinsot, T. On the impact of H2 -enrichment on flame structure and combustion dynamics of a lean partially-premixed turbulent swirling flame. Combust. Flame 2022, 241, 112120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.H.; Emara, A.A.; Elkady, M.A. An Influence of a Fluidic Oscillator Insertion in a Swirl-Stabilized Burner on Turbulent Premixed Flame. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2019, 141, 061001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta-Luna, D.A.; Vigueras-Zúñiga, M.O.; Herrera-May, A.L.; Zamora-Castro, S.A.; Tejeda-del-Cueto, M.E. Optimized Design of a Swirler for a Combustion Chamber of Non-Premixed Flame Using Genetic Algorithms. Energies 2020, 13, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Lavadera, M.L.; Brackmann, C.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Konnov, A.A. Experimental and kinetic modeling study of NO formation in premixed CH4+O2+N2 flames. Combust. Flame 2021, 223, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, L.; Bai, X. FGM modeling of ammonia/n-heptane combustion under RCCI engine conditions. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2024, 40, 105601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burner Geometry (for low swirl, S = 0–0.3 [28]) | Burner tube diameter | D | 40 mm |

| Burner tube length | L | 680 mm | |

| Number of helical strips | - | 4 | |

| Hub diameter | Do | 7 mm | |

| Relative blade angle with the axial direction | δ | 17.3° | |

| Swirl number | S | 0.21 | |

| Gas Fuel, Liquid Petroleum Gas Iraqi (LPG) | Propane | - | 64.25 Mol % |

| n-Butane | - | 24.22 Mol % | |

| i-Butane | - | 11.01 Mol % | |

| Ethane | - | 0.09 Mol % | |

| Pentane | - | 0.43 Mol % | |

| Operation conditions | Gas fuel (LPG) flow rate | Vf | 1.75 and 4.5 SLPM |

| Hydrogen flow rate | VH | 0.1 to 0.98 SLPM | |

| Air flow rate | Va | 92 and 118 SLPM | |

| Equivalence Ratio | φ | 0.501 and 1.04 | |

| Mixture temperature | Tm | 303 K | |

| Parameter | Min. for Recorded Value | Max. for Recorded Value | Average Error % (Uncertainty) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air flow rate (L/min) | 92 | 118 | ±0.589 |

| LPG flow rate (L/min) | 1.75 | 4.5 | ±0.1456 |

| Hydrogen flow rate (L/min) | 0.1 | 0.98 | ±0.0221 |

| Flame temperature (K) | 977 | 1178 | ±1.452 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alhamd, A.E.J.; Akroot, A.; Abdul Wahhab, H.A. Swirl Flame Stability for Hydrogen-Enhanced LPG Combustion in a Low-Swirl Burner: Experimental Investigation. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010347

Alhamd AEJ, Akroot A, Abdul Wahhab HA. Swirl Flame Stability for Hydrogen-Enhanced LPG Combustion in a Low-Swirl Burner: Experimental Investigation. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):347. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010347

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhamd, Abdulrahman E. J., Abdulrazzak Akroot, and Hasanain A. Abdul Wahhab. 2026. "Swirl Flame Stability for Hydrogen-Enhanced LPG Combustion in a Low-Swirl Burner: Experimental Investigation" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010347

APA StyleAlhamd, A. E. J., Akroot, A., & Abdul Wahhab, H. A. (2026). Swirl Flame Stability for Hydrogen-Enhanced LPG Combustion in a Low-Swirl Burner: Experimental Investigation. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010347