The Therapeutic Loop: Closed-Loop Epilepsy Systems Mirroring the Read–Write Architecture of Brain–Computer Interfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

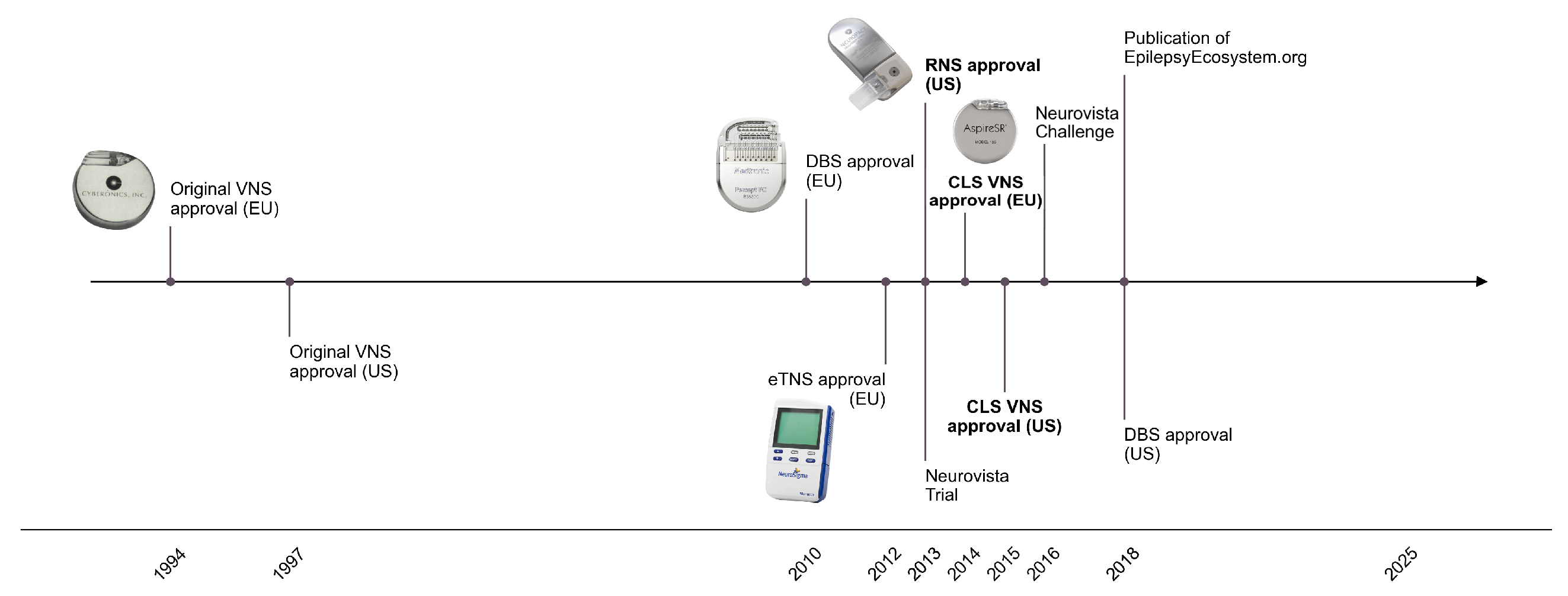

| System | Architecture | Approval Status | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| VNS (conventional) | OLS | Adjunctive therapy (CE 1994 (EU); FDA 1997 (US)) [62] | NeuroCybernetic Prosthesis System |

| VNS (latest) | CLS | Adjunctive therapy (CE 2014 (EU); FDA 2015 (US)) [63,64,65] | AspireSR® and SenTiva® |

| DBS | OLS with CLS capability | Adjunctive therapy (CE 2010 (EU); FDA 2018 (US)) [43,66] | Percept™ PC |

| RNS | CLS | Adjunctive therapy (FDA 2013 (US) [67]) | NeuroPace RNS® System |

| eTNS | OLS | Adjunctive therapy (CE 2012 (EU)) [68] | Monarch™ eTNS™ |

| FCS | OLS | Adjunctive therapy (CE 2022 (EU) [69]) | EASEE® |

| rTMS | OLS and CLS | Investigational | |

| tDC | OLS and CLS | Investigational |

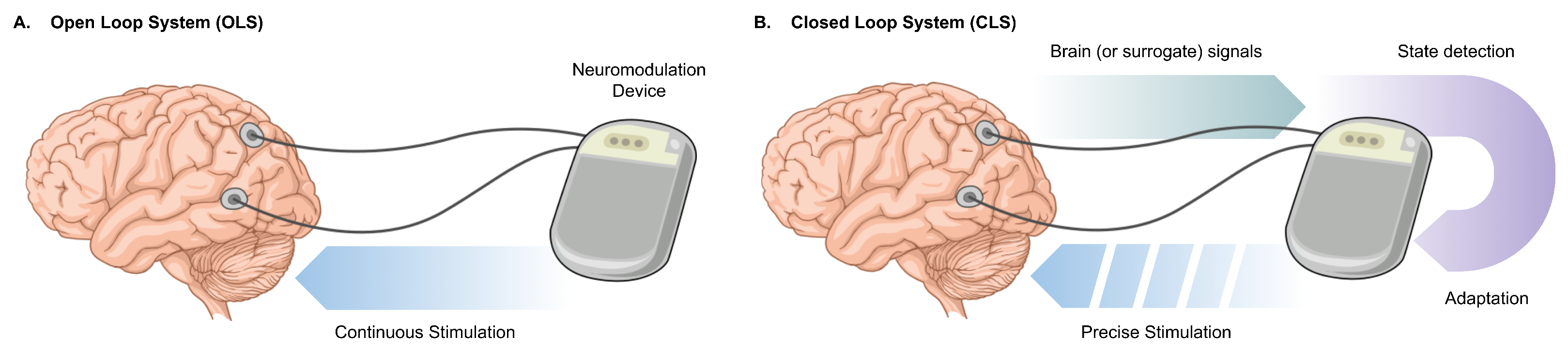

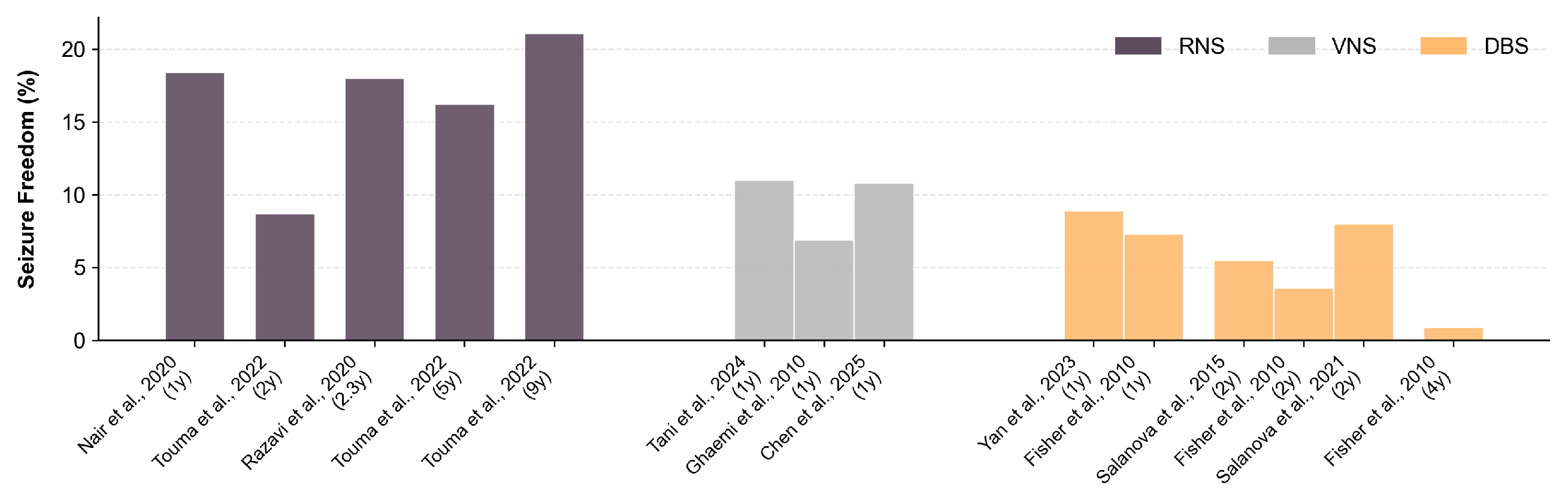

2. The Plateau of Clinically Deployable Devices

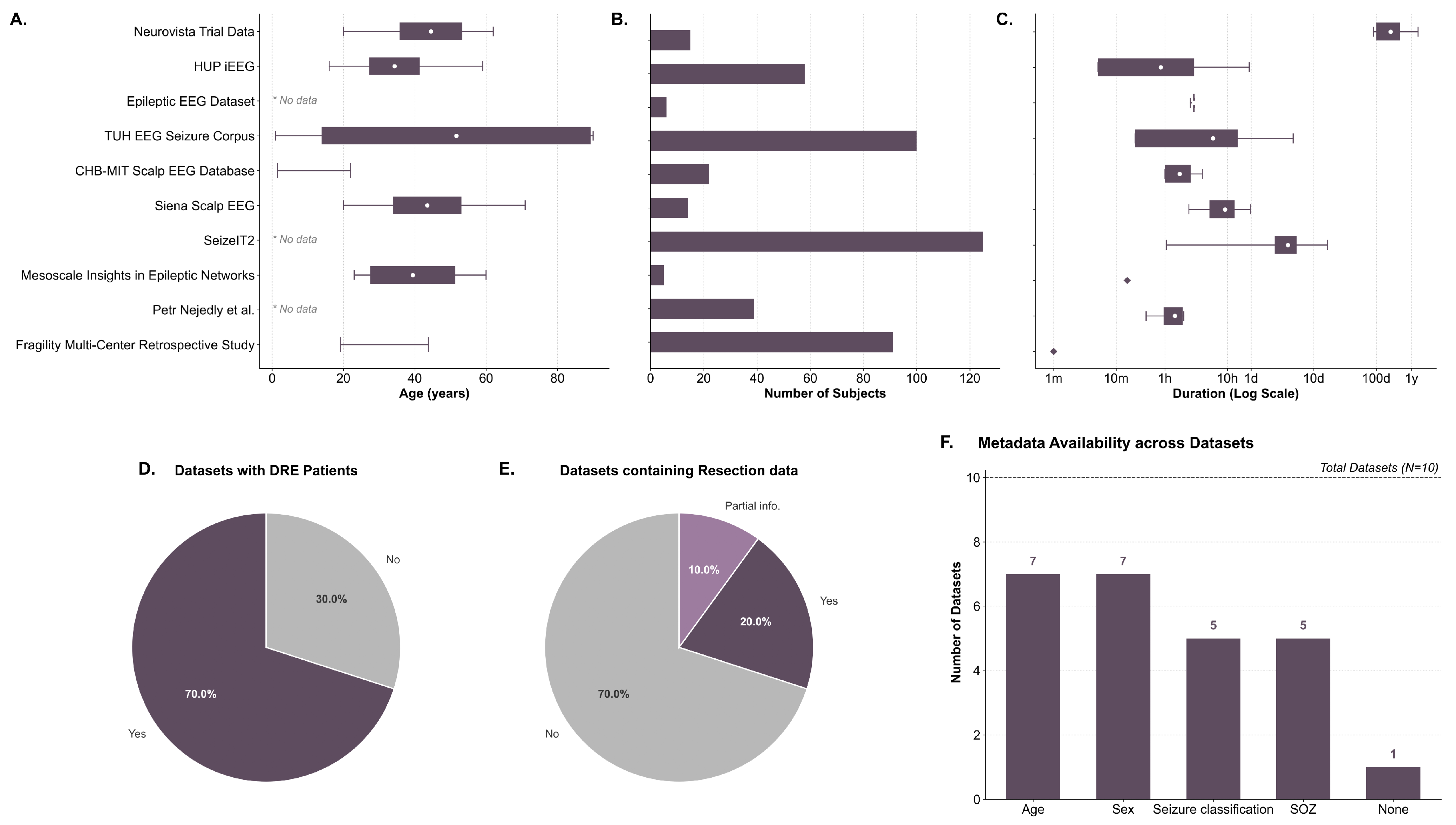

3. Scarcity of Complete Public Datasets

3.1. Current Available Datasets

3.2. Why Is It So Difficult to Find Data?

4. Intrinsic Limitations

4.1. State Definition

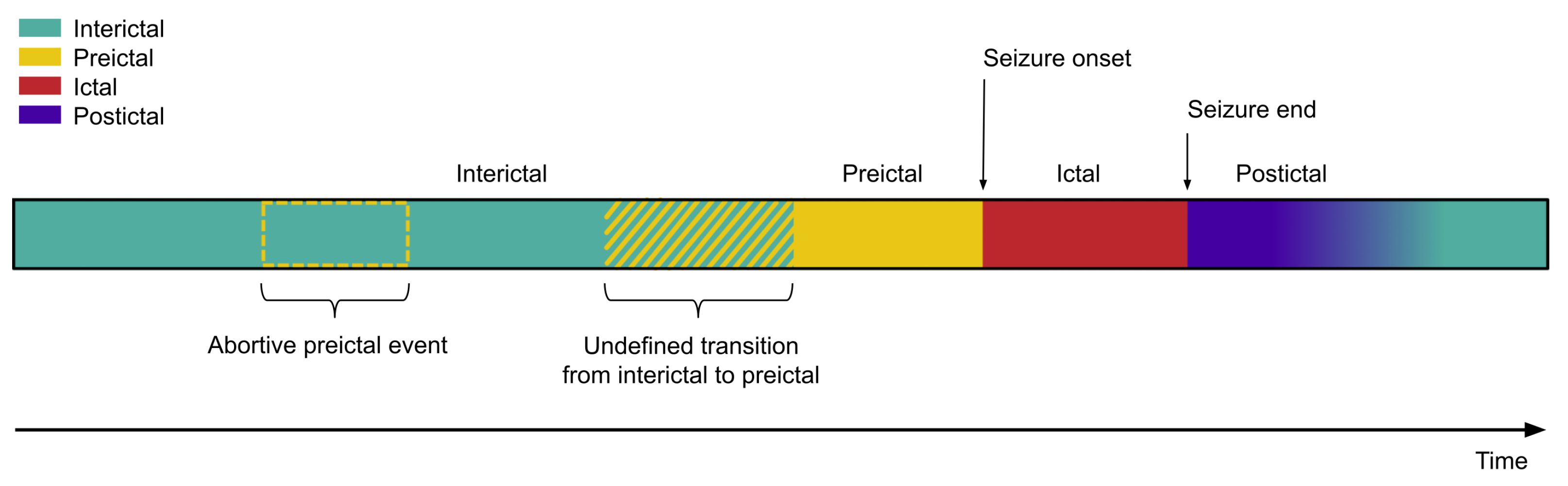

- The ictal state is the least controversial and the most clearly delineated [124,125]. Clinical experts have established behavioural and pathophysiological criteria that mark the onset and termination of seizures [126]. Minor discrepancies among clinicians are generally acceptable, and the community relies on these timepoint annotations as the de facto ground truth [127].

- In contrast, the preictal and postictal states are ambiguous [91,128]. For the preictal state, there is no agreement regarding its temporal onset. Proposed definitions range from minutes to hours, days, or even months before seizure onset [129,130,131,132]. Its underlying dynamics also remain unclear, both in terms of whether preictal states share common features across individuals with DRE, and whether a single patient experiences seizures preceded by distinct preictal patterns [132,133]. Pre-ictal definition relies on the seizure onset, however, it is possible that some preictal states never reach seizure transition due to regulatory brain activity. In these cases, an algorithm might correctly detect the pre-ictal state, but due to the lack of ground truth it would be regarded as a false positive.

- Finally, the interictal state is often defined simply as all remaining periods outside the preictal, ictal, or postictal windows. It is inherently dependent on the delineation of seizure-related states, and consequently liable to error.

4.2. Long-Term Changes in Brain Dynamics

5. The Depth–Breadth Dilemma

5.1. Breadth: General Paradigm

5.2. Depth: Patient-Specific Paradigm

5.3. Prevailing Trends and Emerging Solutions

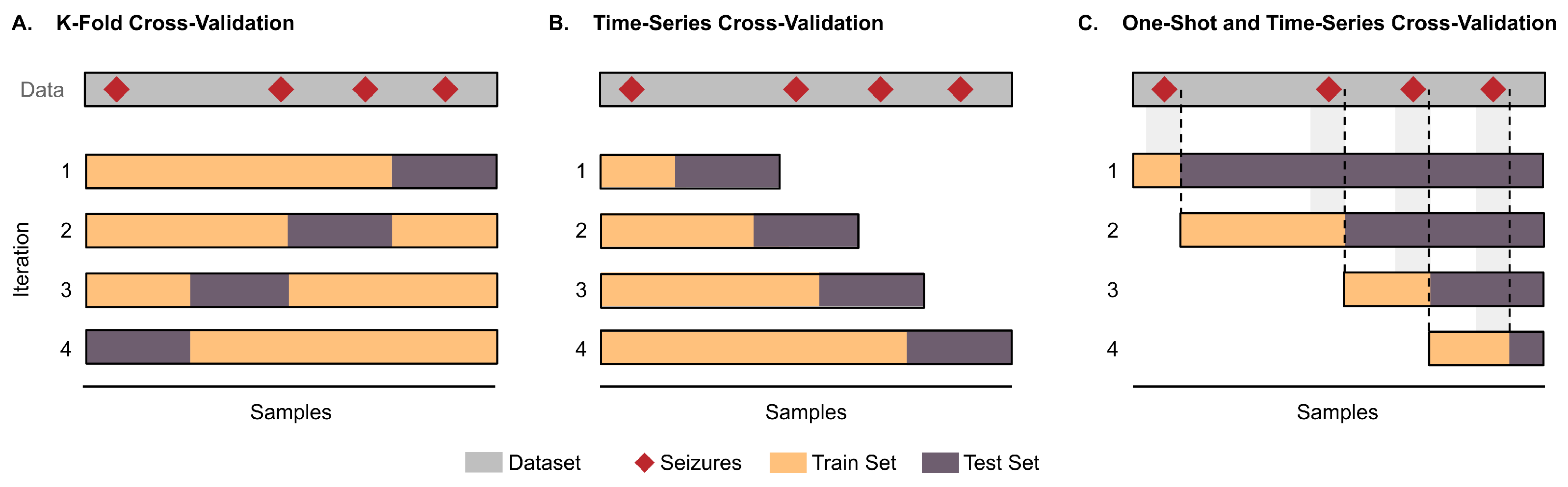

6. Methodological Issues in Performance Evaluation

7. Discussion

7.1. Dataset Improvement

7.1.1. Increasing Cohort Sizes

7.1.2. Mimicking Real-Life Data

7.1.3. DRE Focus

7.1.4. Metadata

7.1.5. The Surgical Resection as an Additional Ground Truth

7.2. Overcoming Intrinsic Limitations

7.2.1. Goal-Oriented State Definition

7.2.2. Addressing Brain Drift

7.3. Performance Evaluation: A Patient-Centric Approach

7.3.1. Preferences for Seizure Detection

7.3.2. Preferences for Seizure Prediction

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASM | Anti-seizure medication |

| aDBS | Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation |

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interface |

| CLS | Closed-Loop System |

| DBS | Deep Brain Stimulation |

| DRE | Drug Resistant Epilepsy |

| ECoG | Electrocorticography |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| eTNS | External Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation |

| FCS | Focal Cortex Stimulation |

| iEEG | Intracranial Electroencephalogram |

| OLS | Open-Loop System |

| RNS | Responsive Neurostimulation System |

| rTMS | Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SEEG | Stereotactic Electroencephalogram |

| SOZ | Seizure Onset Zone |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| VNS | Vagus Nerve Stimulation |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO); International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE); International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). EPILEPSY: A Public Health Imperative; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perucca, E.; Perucca, P.; White, H.S.; Wirrell, E.C. Drug resistance in epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.J.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Y.X.; Lin, H.W.; Gu, Z.C. Current trends and hotspots in drug-resistant epilepsy research: Insights from a bibliometric analysis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1023832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marouf, H.; Mohamed, L.A.; Ftatary, A.E.; Gaber, D.E. Prevalence and risk factors associated with drug-resistant epilepsy in adult epileptic patients. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2023, 59, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löscher, W.; Potschka, H.; Sisodiya, S.M.; Vezzani, A. Drug resistance in epilepsy: Clinical impact, potential mechanisms, and new innovative treatment options. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 606–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheims, S.; Sperling, M.R.; Ryvlin, P. Drug-resistant epilepsy and mortality—Why and when do neuromodulation and epilepsy surgery reduce overall mortality. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 3020–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Menachem, E.; Schmitz, B.; Kälviäinen, R.; Thomas, R.H.; Klein, P. The burden of chronic drug-refractory focal onset epilepsy: Can it be prevented? Epilepsy Behav. 2023, 148, 109435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alare, K.; Ogungbemi, B.; Fagbenro, A.; Adetunji, B.; Owonikoko, O.; Omoniyo, T.; Jagunmolu, H.; Kayode, A.; Afolabi, S. Drug resistance predictive utility of age of onset and cortical imaging abnormalities in epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2024, 60, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.R.; Jin, M.; Sun, S.Z. Etiological analysis of 167 cases of drug-resistant epilepsy in children. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, R.A.; Beers, L.; Farah, E.; Al-Akaidi, M.; Zhang, Y.; Locascio, J.J.; Properzi, M.J.; Schultz, A.P.; Chhatwal, J.P.; Johnson, K.A.; et al. The neurophysiology and seizure outcomes of late onset unexplained epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 2667–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potschka, H. The aging brain and late onset drug-refractory epilepsies. Seizure 2025, 128, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, B.; Panzini, M.A.; Carpentier, A.V.; Comtois, J.; Rioux, B.; Gore, G.; Bauer, P.R.; Kwon, C.S.; Jetté, N.; Josephson, C.B.; et al. Incidence and prevalence of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Neurology 2021, 96, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guery, D.; Rheims, S. Clinical Management of Drug Resistant Epilepsy: A review on current strategies. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2229–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyuran, R.; Mahadevan, A.; Mhatre, R.; Arimappamagan, A.; Sinha, S.; Bharath, R.D.; Rao, M.B.; Saini, J.; Raghavendra, K.; Mundlamuri, R.C.; et al. Neuropathological spectrum of drug resistant epilepsy: 15-years-experience from a tertiary care centre. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 91, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabbasy, D.; Evers, S.; Majoie, M.H.J.M.; Schijns, O.E.M.G.; M’Rabet, L.; Van Kranen-Mastenbroek, V.H.J.M.; Eekers, D.B.P.; Houben, R.; Hendriks, M.; Colon, A.; et al. The Economic and societal burden associated with drug-resistant epilepsy in the Netherlands: An AIM@EPILEPSY burden-of-disease study protocol. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e095123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, V.; Veronesi, C.; Cappuccilli, M.; Andretta, M.; Bacca, M.; Barbieri, A.; Bartolini, F.; Brega, A.; Cillo, M.R.; Colasuonno, F.; et al. Characteristics, therapeutic pathway and the economic burden of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: A real-world analysis following the introduction of cenobamate in Italy. Epilepsia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mula, M.; Kanner, A.M.; Jetté, N.; Sander, J.W. Psychiatric comorbidities in people with epilepsy. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2020, 11, e112–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.I.; Fatima, R.; Ullah, I.; Atta, M.; Awan, A.; Nashwan, A.J.; Ahmed, S. Perceived stigma, discrimination and psychological problems among patients with epilepsy. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1000870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeni, K. Stigma and psychosocial problems in patients with epilepsy. Explor. Neurosci. 2023, 2, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, Y.; Okanishi, T.; Noma, H.; Kanai, S.; Kawaguchi, T.; Sunada, H.; Fujimoto, A.; Maegaki, Y. Prognostic factors for employment outcomes in patients with a history of childhood-onset drug-resistant epilepsy. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1173126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharel, R.; Poudel, P.; Lama, S.; Thapa, K.; Sigdel, R.; Shrestha, E. Burden and Its Predictors among Caregivers of Patient with Epilepsy. J. Epilepsy Res. 2020, 10, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Lim, K.S.; Tang, L.Y.; David, P.; Ong, Z.Q.; Wong, K.Y.; Ji, M. Caregiving burden for adults with epilepsy and coping strategies, a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 164, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakis, I.; Flesler, S.; Ghorpade, S.; Pineda, R.C.; Joshi, K.; Cooper, J.; Patkar, S.; Schulz, A.; Anand, S.B.; Barnes, N. Caregiver burden and healthcare providers perspectives in epilepsy: An observational study in China, Taiwan, and Argentina. Epilepsy Behav. Rep. 2024, 30, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Shao, Q.; Hou, K.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X. The experiences of caregivers of children with epilepsy: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research studies. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 987892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.T.; Kaiser, K.; Dixon-Salazar, T.; Elliot, A.; McNamara, N.; Meskis, M.A.; Golbeck, E.; Tatachar, P.; Laux, L.; Raia, C.; et al. Seizure burden in severe early-life epilepsy: Perspectives from parents. Epilepsia Open 2019, 4, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, P.; Foster, D.L.; Sander, J.W.; Dupont, S.; Gil-Nagel, A.; O’Flaherty, E.D.; Alvarez-Baron, E.; Medjedovic, J. The burden of epilepsy and unmet need in people with focal seizures. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledano, R.; Villanueva, V.; Toledo, M.; Sabaniego, J.; Pérez-Domper, P. Clinical and economic implications of epilepsy management across treatment lines in Spain: A real-life database analysis. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 5945–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirker, S.; Graef, A.; Gächter, M.; Baumgartner, C. Costs of Epilepsy in Austria: Unemployment as a primary driving factor. Seizure 2021, 89, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerle, P.; Schneider, U.; Holtkamp, M.; Gloveli, T.; Dugladze, T. Outlines to Initiate Epilepsy Surgery in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzvari, T.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ranganatha, A.; Daher, J.C.; Freire, I.; Shamsi, S.M.F.; Anthony, O.V.P.; Hingorani, A.G.; Sinha, A.S.; Nazir, Z. A comprehensive review of recent trends in surgical approaches for epilepsy management. Cureus 2024, 16, e71715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Martinez, J.A. Epilepsy surgery in the last 10 years: Advancements and controversies. Epiliepsy Curr./Epilepsy Curr. 2025, 15357597251344166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, F.; Krueger, M.T.; Delev, D.; Theys, T.; Van Roost, D.M.; Fountas, K.; Schijns, O.E.; Roessler, K. Current state of the art of traditional and minimal invasive epilepsy surgery approaches. Brain Spine 2024, 4, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomei, F. The epileptogenic network concept: Applications in the SEEG exploration of lesional focal epilepsies. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2024, 54, 103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, H.; Nair, D.R.; Leahy, R.M. Multilayer brain networks can identify the epileptogenic zone and seizure dynamics. eLife 2023, 12, e68531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K. Effective connectivity predicts surgical outcomes in temporal lobe epilepsy: A SEEG study. Cns Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, A.; Jallul, T.; Alotaibi, F.; Amer, F.; Najjar, A.; Alhazmi, R.; Faraidy, M.A.; Alharbi, A.; Aldurayhim, F.; Barnawi, Z.; et al. Outcomes of resective surgery in pediatric patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: A single-center study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Epilepsia Open 2023, 8, 930–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englot, D.J.; Chang, E.F. Rates and predictors of seizure freedom in resective epilepsy surgery: An update. Neurosurg. Rev. 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobst, B.C.; Cascino, G.D. Resective Epilepsy Surgery for Drug-Resistant Focal Epilepsy. JAMA 2015, 313, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, G.K.; Rathore, C.; Jeyaraj, M.K.; Wattamwar, P.; Sarma, S.P.; Radhakrishnan, K. Predictors of seizure outcome following resective surgery for drug-resistant epilepsy associated with focal gliosis. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 130, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Sinha, J.K.; Ghosh, S.; Sharma, H.; Bhaskar, R.; Narayanan, K.B. A comprehensive review of emerging trends and innovative therapies in epilepsy management. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, O.; Grezenko, H.; Rehman, A.; Sher, H.; Sher, Z.; Kaakyire, D.A.; Hanifullah, S.; Dabas, M.; Saleh, G.; Shehryar, A.; et al. Role of Responsive Neurostimulation in Managing Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Systematic Review of Clinical outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e68032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, F. A review of epilepsy detection and prediction methods based on EEG signal processing and deep learning. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1468967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foutz, T.J.; Wong, M. Brain stimulation treatments in epilepsy: Basic mechanisms and clinical advances. Biomed. J. 2021, 45, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergey, G.K.; Morrell, M.J.; Mizrahi, E.M.; Goldman, A.; King-Stephens, D.; Nair, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Jobst, B.; Gross, R.E.; Shields, D.C.; et al. Long-term treatment with responsive brain stimulation in adults with refractory partial seizures. Neurology 2015, 84, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Menachem, E. Vagus-nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2002, 1, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, P.; Soryal, I.; Dhahri, P.; Wimalachandra, W.; Leat, A.; Hughes, D.; Toghill, N.; Hodson, J.; Sawlani, V.; Hayton, T.; et al. Clinical outcomes of VNS therapy with AspireSR® (including cardiac-based seizure detection) at a large complex epilepsy and surgery centre. Seizure 2018, 58, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangiabadi, N.; Ladino, L.D.; Sina, F.; Orozco-Hernández, J.P.; Carter, A.; Téllez-Zenteno, J.F. Deep Brain Stimulation and Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Review of the literature. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.M. Closed-Loop brain stimulation and paradigm shifts in epilepsy surgery. Neurol. Clin. 2022, 40, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Hirsch, M.; Knake, S.; Kaufmann, E.; Kegele, J.; Rademacher, M.; Vonck, K.; Coenen, V.A.; Glaser, M.; Jenkner, C.; et al. Focal cortex stimulation with a novel implantable device and antiseizure outcomes in 2 prospective multicenter Single-Arm trials. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, G.M.; Guadix, S.; Lavieri, M.T.; Uribe-Cardenas, R.; Kocharian, G.; Williams, N.; Sholle, E.; Grinspan, Z.; Hoffman, C.E. Closed-loop vagal nerve stimulation for intractable epilepsy: A single-center experience. Seizure 2021, 88, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.; DesMarteau, J.A.; Koontz, E.H.; Wilks, S.J.; Melamed, S.E. Responsive vagus Nerve Stimulation for Drug Resistant epilepsy: A review of new features and practical guidance for advanced practice providers. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 610379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramgopal, S.; Thome-Souza, S.; Jackson, M.; Kadish, N.E.; Fernández, I.S.; Klehm, J.; Bosl, W.; Reinsberger, C.; Schachter, S.; Loddenkemper, T. Seizure detection, seizure prediction, and closed-loop warning systems in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014, 37, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Jia, Q.; Xie, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Yang, G.; et al. Wireless Closed-Loop Optical regulation system for seizure detection and suppression in vivo. Front. Nanotechnol. 2022, 4, 829751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisterson, N.D.; Wozny, T.A.; Kokkinos, V.; Constantino, A.; Richardson, R.M. Closed-Loop Brain Stimulation for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: Towards an Evidence-Based Approach to Personalized Medicine. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 16, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, Y.M.; Park, H.R.; Lee, S. Deep Brain Stimulation Therapy for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: Present and Future Perspectives. J. Epilepsy Res. 2025, 15, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, C.; Yang, K.; Wang, N.; Yang, L.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L. Advancements in Surgical Therapies for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: A Paradigm Shift towards Precision Care. Neurol. Ther. 2025, 14, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y. Neurostimulation as a promising epilepsy therapy. Epilepsia Open 2017, 2, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo, A.E.; Nieminen, J.O.; Lioumis, P.; Metsomaa, J.; Souza, V.H.; Sinisalo, H.; Stenroos, M.; Sarvas, J.; Ilmoniemi, R.J. Closed-loop optimization of transcranial magnetic stimulation with electroencephalography feedback. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; Liu, H.; Jin, F.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Fan, L.; Song, M.; Zuo, N.; et al. A wearable repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation device. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.; Morales-Quezada, L.; Carvalho, S.; Thibaut, A.; Doruk, D.; Chen, C.F.; Schachter, S.C.; Rotenberg, A.; Fregni, F. Surface EEG-Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (TDCS) Closed-Loop System. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2017, 27, 1750026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, V.; Sisterson, N.D.; Wozny, T.A.; Richardson, R.M. Association of Closed-Loop brain stimulation neurophysiological features with seizure control among patients with focal epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afra, P.; Adamolekun, B.; Aydemir, S.; Watson, G.D.R. Evolution of the Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) therapy System Technology for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Front. Med. Technol. 2021, 3, 696543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, U.C.; Bohlmann, K.; Vajkoczy, P.; Straub, H.B. Implantation of a new Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Therapy® generator, AspireSR®: Considerations and recommendations during implantation and replacement surgery—Comparison to a traditional system. Acta Neurochir. 2015, 157, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Approval (PMA)—P970003. 2015. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=p970003s173 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Approval (PMA)—P970003. 2017. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfres/res.cfm?id=212010#:~:text=The%20physician%20uses%20the%20programming,Vagus%20Nerve%20Stimulation%20(VNS) (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Approval (PMA)—P960009S219. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=p960009s219 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Premarket Approval (PMA)—P100026. 2013. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P100026 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- DeGiorgio, C.M.; Soss, J.; Cook, I.A.; Markovic, D.; Gornbein, J.; Murray, D.; Oviedo, S.; Gordon, S.; Corralle-Leyva, G.; Kealey, C.P.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of trigeminal nerve stimulation for drug-resistant epilepsy. Neurology 2013, 80, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Hirsch, M.; Knake, S.; Mertens, A.; Rademacher, M.; Kaufmann, E.; Kegele, J.; Jenkner, C.; Coenen, V.; Glaser, M.; et al. Two-year outcomes of epicranial focal cortex stimulation in pharmacoresistant focal epilepsy. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 3242–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryvlin, P.; Rheims, S.; Hirsch, L.J.; Sokolov, A.; Jehi, L. Neuromodulation in epilepsy: State-of-the-art approved therapies. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa, J.A.; Marcuse, L.; Fields, M.; La Vega-Talbott, M.; Yoo, J.Y.; Wolf, S.M.; McGoldrick, P.; Ghatan, S.; Panov, F. Long-term outcomes after responsive neurostimulation for treatment of refractory epilepsy: A single-center experience of 100 cases. J. Neurosurg. 2023, 139, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawar, I.; Krishnan, B.; Mackow, M.; Alexopoulos, A.; Nair, D.; Punia, V. The Efficacy, Safety, and Outcomes of Brain-responsive Neurostimulation (RNS® System) therapy in older adults. Epilepsia Open 2021, 6, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Kim-McManus, O.; Sattar, S.; Rismanchi, N.; Ravindra, V.; Gonda, D.D. 271 A retrospective, chart review study of the efficacy and safety of the RNS system in pediatric populations for medically refractory focal epilepsy. Neurosurgery 2024, 70, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.R.; Laxer, K.D.; Weber, P.B.; Murro, A.M.; Park, Y.D.; Barkley, G.L.; Smith, B.J.; Gwinn, R.P.; Doherty, M.J.; Noe, K.H.; et al. Nine-year prospective efficacy and safety of brain-responsive neurostimulation for focal epilepsy. Neurology 2020, 95, e1244–e1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, B.; Rao, V.R.; Lin, C.; Bujarski, K.A.; Patra, S.E.; Burdette, D.E.; Geller, E.B.; Brown, M.M.; Johnson, E.A.; Drees, C.; et al. Real-world experience with direct brain-responsive neurostimulation for focal onset seizures. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touma, L.; Dansereau, B.; Chan, A.Y.; Jetté, N.; Kwon, C.; Braun, K.P.J.; Friedman, D.; Jehi, L.; Rolston, J.D.; Vadera, S.; et al. Neurostimulation in people with drug-resistant epilepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis from the ILAE Surgical Therapies Commission. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1314–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, N.; Dibué, M.; Verner, R.; Nishikawa, S.M.; Gordon, C.; Kawai, K.; Kishima, H. One-year seizure freedom and quality of life in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy receiving adjunctive vagus nerve stimulation in Japan. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 2154–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi, K.; Elsharkawy, A.E.; Schulz, R.; Hoppe, M.; Polster, T.; Pannek, H.; Ebner, A. Vagus nerve stimulation: Outcome and predictors of seizure freedom in long-term follow-up. Seizure 2010, 19, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Yang, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhao, X. Long-term outcome of vagus nerve stimulation therapy in drug-resistant epilepsy: A retrospective single-center study. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1564735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, V.; Witt, T.; Worth, R.; Henry, T.R.; Gross, R.E.; Nazzaro, J.M.; Labar, D.; Sperling, M.R.; Sharan, A.; Sandok, E.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of thalamic stimulation for drug-resistant partial epilepsy. Neurology 2015, 84, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, L.; Gao, R.; Ni, D.; Shu, W.; Xu, C.; Ren, L.; Yu, T. Deep brain stimulation for patients with refractory epilepsy: Nuclei selection and surgical outcome. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1169105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.; Salanova, V.; Witt, T.; Worth, R.; Henry, T.; Gross, R.; Oommen, K.; Osorio, I.; Nazzaro, J.; Labar, D.; et al. Electrical stimulation of the anterior nucleus of thalamus for treatment of refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salanova, V.; Sperling, M.R.; Gross, R.E.; Irwin, C.P.; Vollhaber, J.A.; Giftakis, J.E.; Fisher, R.S. The SANTÉ study at 10 years of follow-up: Effectiveness, safety, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, R.S.; Tarver, W.B.; Zabara, J. The implantable Neurocybernetic prosthesis system. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1991, 14, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisterson, N.D.; Wozny, T.A.; Kokkinos, V.; Bagic, A.; Urban, A.P.; Richardson, R.M. A rational approach to understanding and evaluating responsive neurostimulation. Neuroinformatics 2020, 18, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, P.; Vonck, K.; Van Rijckevorsel, K.; Tahry, R.E.; Elger, C.E.; Mullatti, N.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Wagner, L.; Diehl, B.; Hamer, H.; et al. A prospective, multicenter study of cardiac-based seizure detection to activate vagus nerve stimulation. Seizure 2015, 32, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.S.; Afra, P.; Macken, M.; Minecan, D.N.; Bagić, A.; Benbadis, S.R.; Helmers, S.L.; Sinha, S.R.; Slater, J.; Treiman, D.; et al. Automatic vagus Nerve stimulation Triggered by Ictal Tachycardia: Clinical Outcomes and Device Performance—The U.S. E-37 Trial. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2015, 19, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, W.T.; McFarlane, K.N.; Pucci, G.F. The present and future of seizure detection, prediction, and forecasting with machine learning, including the future impact on clinical trials. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1425490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoka, A.A.E.; Dessouky, M.M.; El-Sayed, A.; Hemdan, E.E.D. EEG seizure detection: Concepts, techniques, challenges, and future trends. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 42021–42051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Litscher, G.; Li, X. Epileptic Seizure Detection Using Machine Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejak, R.G.; Zaveri, H.P.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Leguia, M.G.; Stacey, W.C.; Richardson, M.P.; Kuhlmann, L.; Lehnertz, K. Seizure forecasting: Where do we stand? Epilepsia 2023, 64, S62–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.J.; O’Brien, T.J.; Berkovic, S.F.; Murphy, M.; Morokoff, A.; Fabinyi, G.; D’Souza, W.; Yerra, R.; Archer, J.; Litewka, L.; et al. Prediction of seizure likelihood with a long-term, implanted seizure advisory system in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy: A first-in-man study. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, L.; Karoly, P.; Freestone, D.R.; Brinkmann, B.H.; Temko, A.; Barachant, A.; Li, F.; Titericz, G.; Lang, B.W.; Lavery, D.; et al. Epilepsyecosystem.org: Crowd-sourcing reproducible seizure prediction with long-term human intracranial EEG. Brain 2018, 141, 2619–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, M.; Ke, Y.; An, X.; Liu, S.; Ming, D. Cross-Dataset variability problem in EEG decoding with deep learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, B.; Qiu, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Xia, X. A large EEG dataset for studying cross-session variability in motor imagery brain–computer interface. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajadini, B.; Seydnejad, S.R.; Rezakhani, S. Short-term epileptic seizures prediction based on cepstrum analysis and signal morphology. BMC Biomed. Eng. 2024, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliwowski, M.; Martin, M.; Souloumiac, A.; Blanchart, P.; Aksenova, T. Impact of dataset size and long-term ECoG-based BCI usage on deep learning decoders performance. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1111645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poziomska, M.; Dovgialo, M.; Olbratowski, P.; Niedbalski, P.; Ogniewski, P.; Zych, J.; Rogala, J.; Żygierewicz, J. Quantity versus Diversity: Influence of Data on Detecting EEG Pathology with Advanced ML Models. Neural Netw. 2025, 193, 108073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Rong, F.; Xie, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Shi, G.; Gao, X. A multi-day and high-quality EEG dataset for motor imagery brain–computer interface. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, R.; Mathieson, S.R.; Luca, A.; Ventura, S.; Griffin, S.; Boylan, G.B.; O’Toole, J.M. Scaling convolutional neural networks achieves expert level seizure detection in neonatal EEG. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niso, G.; Gorgolewski, K.J.; Bock, E.; Brooks, T.L.; Flandin, G.; Gramfort, A.; Henson, R.N.; Jas, M.; Litvak, V.; Moreau, J.T.; et al. MEG-BIDS, the brain imaging data structure extended to magnetoencephalography. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, C.R.; Appelhoff, S.; Gorgolewski, K.J.; Flandin, G.; Phillips, C.; Delorme, A.; Oostenveld, R. EEG-BIDS, an extension to the brain imaging data structure for electroencephalography. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgolewski, K.J.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Auer, T.; Bellec, P.; Capotă, M.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Churchill, N.W.; Cohen, A.L.; Craddock, R.C.; Devenyi, G.A.; et al. BIDS apps: Improving ease of use, accessibility, and reproducibility of neuroimaging data analysis methods. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Lamers, D.; Kayhan, E.; Hunnius, S.; Oostenveld, R. Enhancing reproducibility in developmental EEG research: BIDS, cluster-based permutation tests, and effect sizes. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2021, 52, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.; Simmons, A.; Rivera-Villicana, J.; Barnett, S.; Sivathamboo, S.; Perucca, P.; Ge, Z.; Kwan, P.; Kuhlmann, L.; Vasa, R.; et al. EEG datasets for seizure detection and prediction—A review. Epilepsia Open 2023, 8, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.X.; Ng, N.; Seger, S.E.; Ekstrom, A.D.; Kriegel, J.L.; Lega, B.C. Machine learning classifiers for electrode selection in the design of closed-loop neuromodulation devices for episodic memory improvement. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 8150–8163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, J.M.; Li, A.; Revell, A.Y.; Smith, R.J.; Gunnarsdottir, K.M.; Ong, I.Z.; Davis, K.A.; Sinha, N.; Sarma, S.; Litt, B. HUP iEEG Epilepsy Dataset; Stanford Center for Reproducible Neuroscience: Stanford, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, W. Epileptic EEG Dataset V1, Mendeley Data: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Obeid, I.; Picone, J. The Temple University Hospital EEG data corpus. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttag, J. CHB-MIT Scalp EEG Database, version 1.0.0; PhysioNet Data: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Detti, P. Siena Scalp EEG Database, version 1.0.0; PhysioNet: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bhagubai, M.; Chatzichristos, C.; Swinnen, L.; Macea, J.; Zhang, J.; Lagae, L.; Jansen, K.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Sales, F.; Mahler, B.; et al. SeizeIT2: Wearable dataset of patients with focal Epilepsy. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bougou, V.; Vanhoyland, M.; Cleeren, E.; Janssen, P.; Van Paesschen, W.; Theys, T. Mesoscale insights in Epileptic Networks: A Multimodal Intracranial Dataset. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejedly, P.; Kremen, V.; Sladky, V.; Cimbalnik, J.; Klimes, P.; Plesinger, F.; Mivalt, F.; Travnicek, V.; Viscor, I.; Pail, M.; et al. Multicenter intracranial EEG dataset for classification of graphoelements and artifactual signals. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Huynh, C.; Fitzgerald, Z.; Cajigas, I.; Brusko, D.; Jagid, J.; Claudio, A.O.; Kanner, A.M.; Hopp, J.; Chen, S.; et al. Neural fragility as an EEG marker of the seizure onset zone. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, C.N.; King-Stephens, D.; Massey, A.D.; Nair, D.R.; Jobst, B.C.; Barkley, G.L.; Salanova, V.; Cole, A.J.; Smith, M.C.; Gwinn, R.P.; et al. Two-year seizure reduction in adults with medically intractable partial onset epilepsy treated with responsive neurostimulation: Final results of the RNS System Pivotal trial. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarie, B.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Gianlorenco, A.C.; Eltawil, Y.; Sanchez, A.; Fregni, F. Clinical trial design in FDA submissions for neuromodulation devices, 1960–2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2025, 22, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, R.B.; Kolberg, M.; Reed, W.; Mikkelsen, O.L.; Kvam, S.; Halgunset, J.; Budin-Ljøsne, I. Toward a more general consent for the use of patients’ biological material and health information for Medical Research—The Patient Perspective. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2025, 23, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köngeter, A.; Schickhardt, C.; Jungkunz, M.; Bergbold, S.; Mehlis, K.; Winkler, E.C. Patients’ willingness to provide their clinical data for research purposes and acceptance of different consent models: Findings from a representative survey of patients with cancer. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e37665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L119, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik, A.; Barcellona, C.; Mandyam, N.K.; Tan, S.Y.; Tromp, J. Challenges and opportunities for data sharing related to Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools in healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and case study from Thailand. (Preprint). J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 27, e58338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beusink, M.; Koetsveld, F.; Van Scheijen, S.; Janssen, T.; Buiter, M.; Schmidt, M.K.; Rebers, S. Health Research with Data in a Time of Privacy: Which Information do Patients Want? J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2023, 18, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlobin, N.A.; Campbell, J.M.; Rosenow, J.M.; Rolston, J.D. Ethical considerations in the surgical and neuromodulatory treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 127, 108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucca, P.; Dubeau, F.; Gotman, J. Intracranial electroencephalographic seizure-onset patterns: Effect of underlying pathology. Brain 2013, 137, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Berkovic, S.; Capovilla, G.; Connolly, M.B.; French, J.; Guilhoto, L.; Hirsch, E.; Jain, S.; Mathern, G.W.; Moshé, S.L.; et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.S.; Cross, J.H.; D’Souza, C.; French, J.A.; Haut, S.R.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F.E.; Lagae, L.; Moshé, S.L.; et al. Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, M.L.; Wilson, S.B.; Antony, A.; Ghearing, G.; Urban, A.; Bagić, A.I. Seizure detection: Interreader agreement and detection algorithm assessments using a large dataset. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 38, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karoly, P.J.; Rao, V.R.; Gregg, N.M.; Worrell, G.A.; Bernard, C.; Cook, M.J.; Baud, M.O. Cycles in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, N.M.; Attia, T.P.; Nasseri, M.; Joseph, B.; Karoly, P.; Cui, J.; Stirling, R.E.; Viana, P.F.; Richner, T.J.; Nurse, E.S.; et al. Seizure occurrence is linked to multiday cycles in diverse physiological signals. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, J.; Pinto, M.F.; Tavares, M.; Lopes, F.; Oliveira, A.; Teixeira, C. EEG epilepsy seizure prediction: The post-processing stage as a chronology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.C.; Kudlacek, J.; Jiruska, P.; Jefferys, J.G.R. Transition to Seizure from Cellular, Network, and Dynamical Perspectives; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.; Curty, J.; Lopes, F.; Pinto, M.F.; Oliveira, A.; Sales, F.; Bianchi, A.M.; Ruano, M.G.; Dourado, A.; Henriques, J.; et al. Unsupervised EEG preictal interval identification in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Cash, S.S.; Sejnowski, T.J. Heterogeneity of preictal dynamics in human epileptic seizures. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 52738–52748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, L.N.; Duncker, L.; Harvey, C.D. Representational drift: Emerging theories for continual learning and experimental future directions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2022, 76, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, V.L.; Johnson, G.W.; Cai, L.Y.; Landman, B.A.; Schilling, K.G.; Englot, D.J.; Rogers, B.P.; Chang, C. MRI network progression in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy related to healthy brain architecture. Netw. Neurosci. 2021, 5, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, F.; Yao, D.; Xu, P.; Yu, L. Altered Functional Connectivity after Epileptic Seizure Revealed by Scalp EEG. Neural Plast. 2020, 2020, 8851415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; He, C.; Hu, W.; Xiong, K.; Hu, L.; Chen, C.; Xu, S.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; et al. Pre-ictal fluctuation of EEG functional connectivity discriminates seizure phenotypes in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2023, 151, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Feng, Y.; Gan, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y. Microstate-based brain network dynamics distinguishing temporal lobe epilepsy patients: A machine learning approach. NeuroImage 2024, 296, 120683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, E.D.; Pinto, M.; Lopes, F.; Teixeira, C. Concept-drifts adaptation for machine learning EEG epilepsy seizure prediction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivankovic, K.; Principe, A.; Zucca, R.; Dierssen, M.; Rocamora, R. Methods for Identifying Epilepsy Surgery Targets using Invasive EEG: A Systematic review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouelleil, M.; Deshpande, N.; Ali, R. Emerging Trends in Neuromodulation for treatment of Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Front. Pain Res. 2022, 3, 839463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadoon, Y.A.; Khalil, M.; Battikh, D. Machine and Deep Learning-Based Seizure Prediction: A scoping review on the use of temporal and spectral features. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, I.; Abou-Abbas, L.; Henni, K.; Mitiche, A.; Mezghani, N. Domain adaptation for EEG-based, cross-subject epileptic seizure prediction. Front. Neuroinform. 2024, 18, 1303380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, Y.M.; Abdelzaher, M.; Kuhlmann, L.; Ghany, M.A.A.E. General and patient-specific seizure classification using deep neural networks. Analog. Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 2023, 116, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguia, M.G.; Rao, V.R.; Tcheng, T.K.; Duun-Henriksen, J.; Kjær, T.W.; Proix, T.; Baud, M.O. Learning to generalize seizure forecasts. Epilepsia 2022, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, B.S.; Mollaei, M.R.K.; Ebrahimi, F.; Rasekhi, J. Generalizable epileptic seizures prediction based on deep transfer learning. Cogn. Neurodynamics 2022, 17, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari, J.; Nasrabadi, A.M.; Menhaj, M.B.; Raiesdana, S. Epilepsy seizure prediction with few-shot learning method. Brain Inform. 2022, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yang, J.; Sawan, M. Bridging the gap between patient-specific and patient-independent seizure prediction via knowledge distillation. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 036035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saemaldahr, R.; Ilyas, M. Patient-Specific Preictal Pattern-Aware Epileptic Seizure Prediction with Federated Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qin, X.; Wen, H.; Li, F.; Lin, X. Patient-specific approach using data fusion and adversarial training for epileptic seizure prediction. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1172987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Pinto, M.F.; Dourado, A.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Dümpelmann, M.; Teixeira, C. Addressing data limitations in seizure prediction through transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Velasco, S.; Santamaria-Vazquez, E.; Martinez-Cagigal, V.; Marcos-Martinez, D.; Hornero, R. EEGSYM: Overcoming Inter-Subject Variability in Motor Imagery Based BCIs with Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2022, 30, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Alawieh, H.; Racz, F.S.; Fakhreddine, R.; Del R Millán, J. Transfer learning promotes acquisition of individual BCI skills. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, V.; Wyser, D.; Lambercy, O.; Spies, R.; Gassert, R. A penalized time-frequency band feature selection and classification procedure for improved motor intention decoding in multichannel EEG. J. Neural Eng. 2019, 16, 016019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Shao, H.M.; Yao, Y.; Liu, J.L.; Ma, S.W. A personalized feature extraction and classification method for motor imagery recognition. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2021, 26, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yao, L.; Wang, Y. Enhanced motor imagery decoding by calibration Model-Assisted with Tactile ERD. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 4295–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Angrick, M.; Coogan, C.; Candrea, D.N.; Wyse-Sookoo, K.; Shah, S.; Rabbani, Q.; Milsap, G.W.; Weiss, A.R.; Anderson, W.S.; et al. Stable Decoding from a Speech BCI Enables Control for an Individual with ALS without Recalibration for 3 Months. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2304853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pale, U.; Teijeiro, T.; Rheims, S.; Ryvlin, P.; Atienza, D. Combining general and personal models for epilepsy detection with hyperdimensional computing. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 148, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Luo, X.; Ye, L.; Geng, W.; He, J.; Mu, J.; Hou, X.; Zan, X.; Ma, J.; Li, F.; et al. Automated seizure detection in epilepsy using a novel dynamic temporal-spatial graph attention network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, R.; Kanaga, E.G. Theoretical and methodological analysis of EEG based seizure detection and prediction: An exhaustive review. J. Neurosci. Methods 2022, 369, 109483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pale, U.; Teijeiro, T.; Atienza, D. Importance of methodological choices in data manipulation for validating epileptic seizure detection models. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Golmohammadi, M.; Obeid, I.; Picone, J. Objective Evaluation Metrics for Automatic Classification of EEG Events; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiezadeh, S.; Duma, G.M.; Mento, G.; Danieli, A.; Antoniazzi, L.; Del Popolo Cristaldi, F.; Bonanni, P.; Testolin, A. Methodological issues in evaluating machine learning models for EEG seizure prediction: Good Cross-Validation accuracy does not guarantee generalization to new patients. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Bozorgi, Z.D.; Herron, J.; Chizeck, H.J.; Chambers, J.D.; Li, L. Machine learning seizure prediction: One problematic but accepted practice. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 20, 016008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, J.; Pale, U.; Amirshahi, A.; Cappelletti, W.; Ingolfsson, T.M.; Wang, X.; Cossettini, A.; Bernini, A.; Benini, L.; Beniczky, S.; et al. SzCORE: Seizure Community Open-Source Research Evaluation framework for the validation of electroencephalography-based automated seizure detection algorithms. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Zhu, J.; Sawan, M. Power efficient refined seizure prediction algorithm based on an enhanced benchmarking. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanos, C.; Dan, J.; Atienza, D. Benchmark of EEG-based seizure detection algorithms with SzCORE*. In Proceedings of the 2025 47th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Copenhagen, Denmark, 14–18 July 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, A.S.; Abreu, M.; Baptista, M.F.; De Oliveira Carvalho, M.; Peralta, A.R.; Fred, A.; Bentes, C.; Da Silva, H.P. Automated algorithms for seizure forecast: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 6573–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, I.; Teixeira, C.; Pinto, M. On the performance of seizure prediction machine learning methods across different databases: The sample and alarm-based perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1417748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, K.; Qadir, J.; JO’Brien, T.; Kuhlmann, L.; Razi, A. A generative model to synthesize EEG data for epileptic seizure prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2021, 29, 2322–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Zhuo, W.; Xie, Y. An epileptic EEG detection method based on data augmentation and lightweight neural network. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2023, 12, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Y.; Wei, Z.; An, G.; Chen, H. Combining data augmentation and deep learning for improved epilepsy detection. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1378076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, A.; Faria, D.R. Boosting EEG and ECG Classification with Synthetic Biophysical Data Generated via Generative Adversarial Networks. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.P.; Gummadavelli, A.; Farooque, P.; Bonito, J.; Arencibia, C.; Blumenfeld, H.; Spencer, D.D. Association of seizure spread with surgical failure in epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 76, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Guan, Y.; Chen, S. A longitudinal study of surgical outcome of pharmacoresistant epilepsy caused by focal cortical dysplasia. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 2403–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, W.B.; Brunette-Clement, T.; Wang, A.; Phillips, H.W.; Von Der Brelie, C.; Weil, A.G.; Fallah, A. Long-term outcomes of pediatric epilepsy surgery: Individual participant data and study level meta-analyses. Seizure 2022, 101, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Keller, S.; Nicolson, A.; Biswas, S.; Smith, D.; Farah, J.O.; Eldridge, P.; Wieshmann, U. The long-term outcomes of epilepsy surgery. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, S.; Jung, Y.; Ko, D.S.; Kim, H.W.; Yoon, J.P.; Cho, S.; Song, T.J.; Kim, K.; Son, E.; et al. Exploring the Smoking-Epilepsy Nexus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Yuan, S.; Liu, X. Alcohol, coffee, and milk intake in relation to epilepsy risk. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratu, I.; De Clerck, L.; Catenoix, H.; Valton, L.; Aupy, J.; Nica, A.; Rheims, S.; Aubert-Conil, S.; Benoit, J.; Makhalova, J.; et al. Cerebral Cavernous Malformations and Focal Drug-Resistant Epilepsy: Behind a quid pro quo of lesion and Epileptogenic Networks. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025, 32, e70276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Leal, A.; Pinto, M.F.; Dourado, A.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Dümpelmann, M.; Teixeira, C. Removing artefacts and periodically retraining improve performance of neural network-based seizure prediction models. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiezadeh, S.; Duma, G.M.; Mento, G.; Danieli, A.; Antoniazzi, L.; Del Popolo Cristaldi, F.; Bonanni, P.; Testolin, A. Calibrating deep learning classifiers for Patient-Independent Electroencephalogram Seizure Forecasting. Sensors 2024, 24, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Gong, P.; Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. A survey on machine learning from few samples. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 139, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Peixoto, R.; Lopes, L.; Beniczky, S.; Ryvlin, P.; Conde, C.; Claro, J. User involvement in the design and development of medical devices in epilepsy: A systematic review. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 2087–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.E.; Vanderboll, K.; Parent, J.M.; Skolarus, L.E.; Zahuranec, D.B. Health priorities and treatment preferences of adults with epilepsy: A narrative literature review with a systematic search. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 166, 110359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzeskowiak, C.L.; Dumanis, S.B. Seizure Forecasting: Patient and caregiver perspectives. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 717428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse, S.A.; Dumanis, S.B.; Huwig, T.; Hyman, S.; Fureman, B.E.; Bridges, J.F. Patient and caregiver preferences for the potential benefits and risks of a seizure forecasting device: A best–worst scaling. Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 96, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, D.F.T.; Britton, J.W.; Wirrell, E.C. Patient and caregiver view on seizure detection devices: A survey study. Seizure 2016, 41, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset | N | Age | L | DRE | Resect. | Img.Tech. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroVista Trial Data [92] | 15 | >20 | 170 days | Yes | No | iEEG |

| HUP iEEG [107] | 58 1 | >16 | 51 min | Yes | Yes | ECoG or SEEG |

| Epileptic EEG Dataset [108] | 6 | Unk. | 3 h | No | No | EEG |

| TUH EEG Seizure Corpus [109] | 100 | >1 | 5.9 h | No | No | EEG |

| CHB-MIT Scalp EEG Database [110] | 22 | >1.5 | 1 or 4 h | Yes | No | EEG |

| Siena Scalp EEG [111] | 14 | >20 | 9.2 h | No | No | EEG |

| SeizeIT2 [112] | 125 | Both 2 | 3.9 days | Yes | No | Var. 3 |

| Mesoscale Insights [113] | 5 | >23 | Unk. 4 | Yes | Yes | ECoG & SEEG |

| Petr Nejedly et al. [114] | 39 | Unk. | 0.5 or 2 h 5 | Yes | No | SEEG |

| Fragility Multi-Center [115] | 91 | >19 | 1 min 6 | Yes | Yes | ECoG or SEEG |

| Feature | General Paradigm | Patient-Specific Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Training approach | Large, heterogeneous datasets from multiple patients | Unique data for each patient |

| Data requirements | Less data per patient | Substantial patient-specific data |

| Performance | Lower sensitivity and specificity | Superior performance |

| Scalability | High scalability | Low scalability |

| Key advantage | Ease of deployment | Patient-tailored |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Montoya-Gálvez, J.; Ivankovic, K.; Rocamora, R.; Principe, A. The Therapeutic Loop: Closed-Loop Epilepsy Systems Mirroring the Read–Write Architecture of Brain–Computer Interfaces. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010294

Montoya-Gálvez J, Ivankovic K, Rocamora R, Principe A. The Therapeutic Loop: Closed-Loop Epilepsy Systems Mirroring the Read–Write Architecture of Brain–Computer Interfaces. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):294. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010294

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontoya-Gálvez, Justo, Karla Ivankovic, Rodrigo Rocamora, and Alessandro Principe. 2026. "The Therapeutic Loop: Closed-Loop Epilepsy Systems Mirroring the Read–Write Architecture of Brain–Computer Interfaces" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010294

APA StyleMontoya-Gálvez, J., Ivankovic, K., Rocamora, R., & Principe, A. (2026). The Therapeutic Loop: Closed-Loop Epilepsy Systems Mirroring the Read–Write Architecture of Brain–Computer Interfaces. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010294