Cooling Performance of Impingement–Effusion Double-Wall Configurations Under Atmospheric and Elevated Pressures

Abstract

1. Introduction

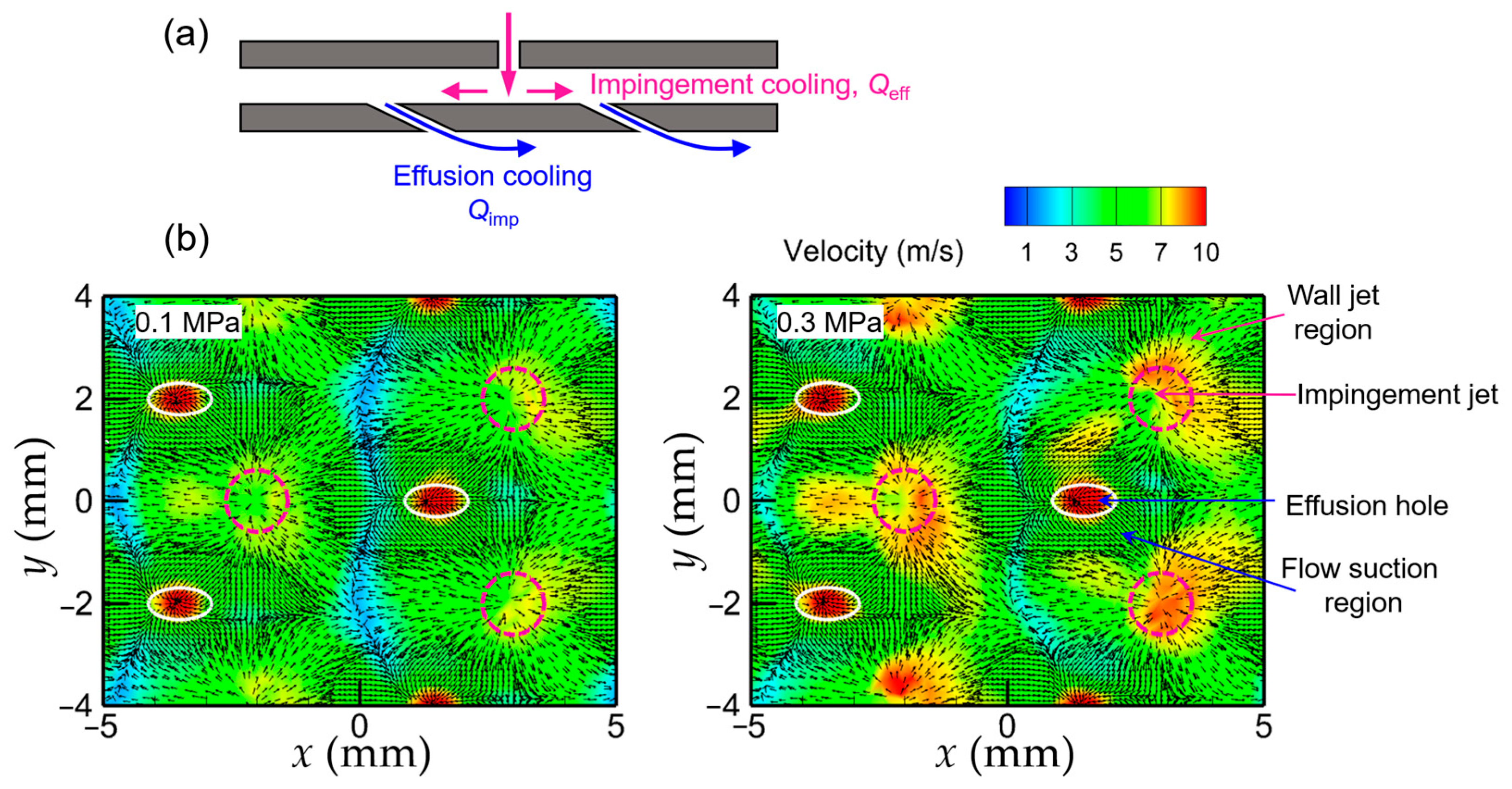

2. Methodologies

2.1. Experimental Setup and Test Section

2.2. Data Reduction and Operating Conditions

2.2.1. Data Reduction Methods and Measurement Error Evaluation

2.2.2. Operating Conditions

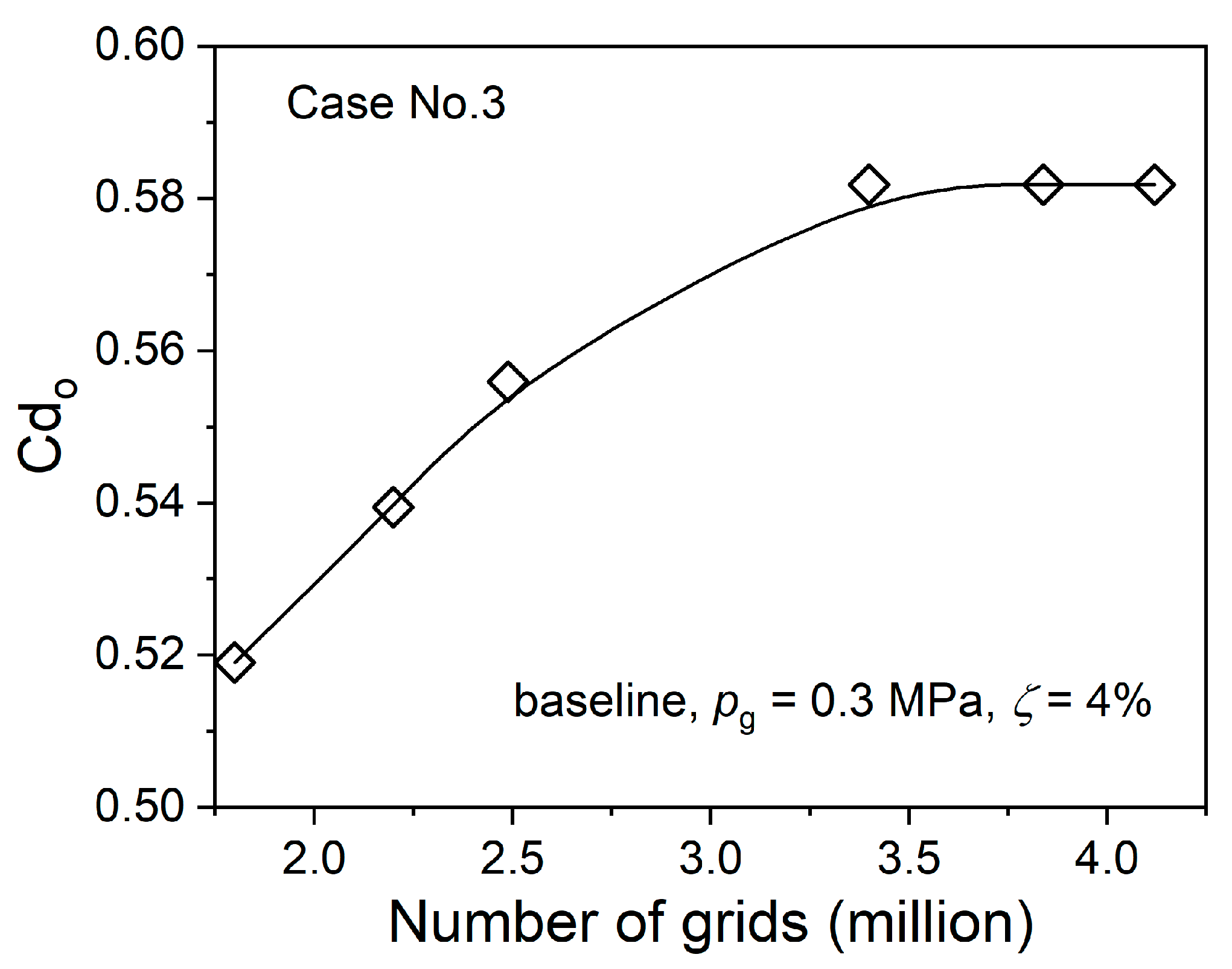

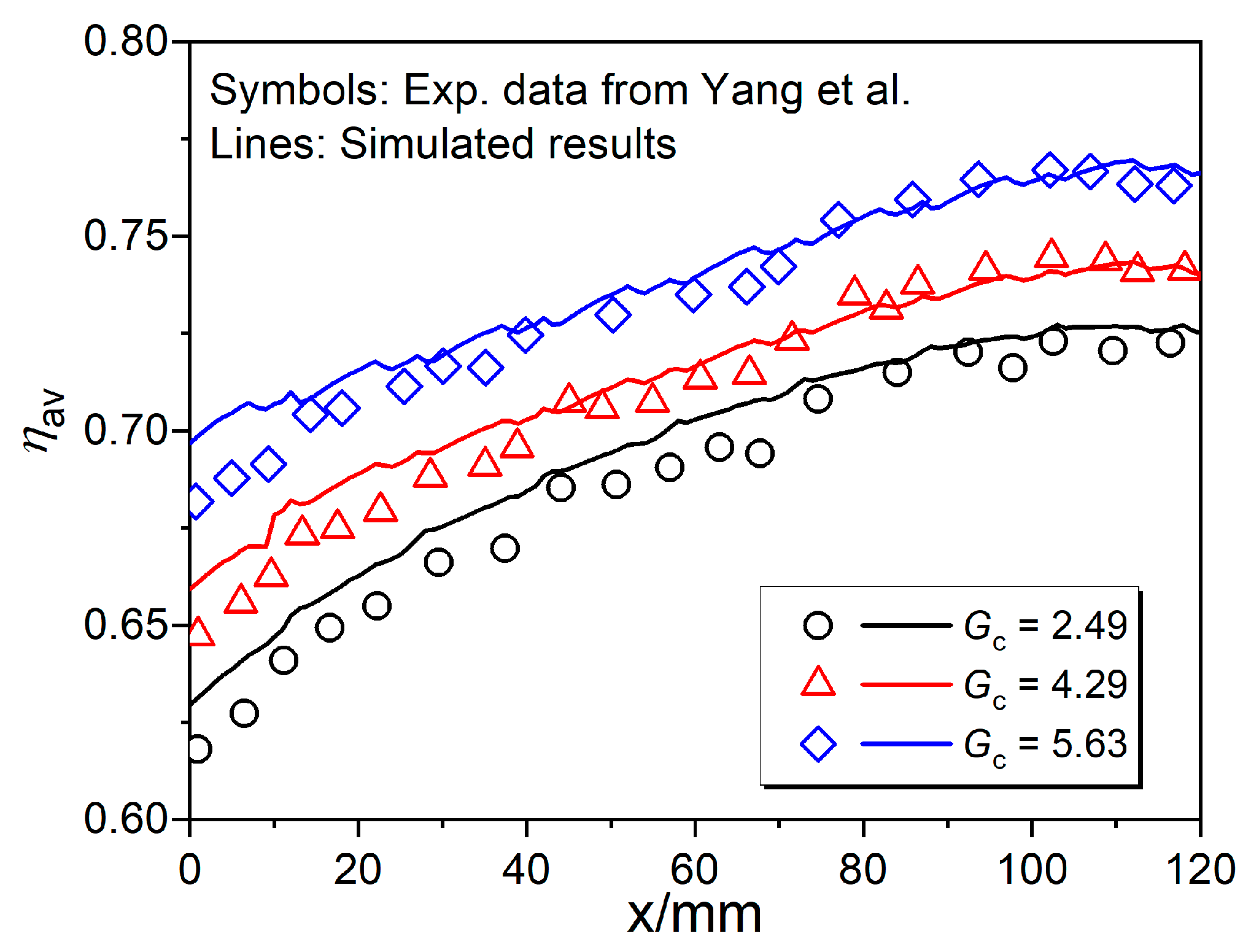

2.3. Numerical Simulation Approach

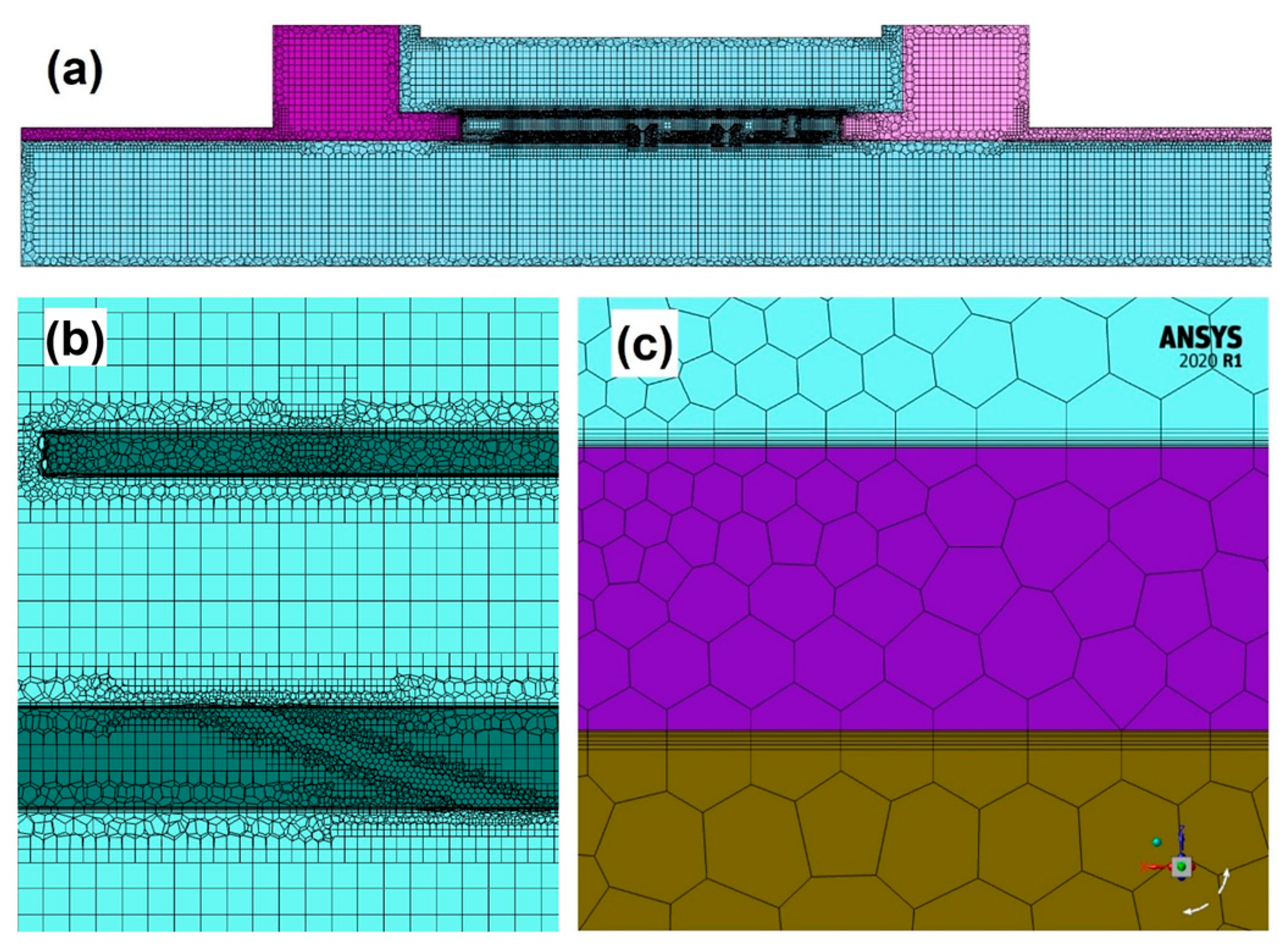

- Maximum global mesh size: 2 mm; minimum global mesh size: 0.1 mm.

- Mesh size on effusion plate: 0.5 mm.

- Boundary-layer grids were generated at all fluid–solid interfaces, with a first-layer height of 0.01 mm, a growth ratio of 1.2, and six layers in total.

- Mesh size of computional zone inside the orifices: 0.1 mm.

3. Results and Discussion

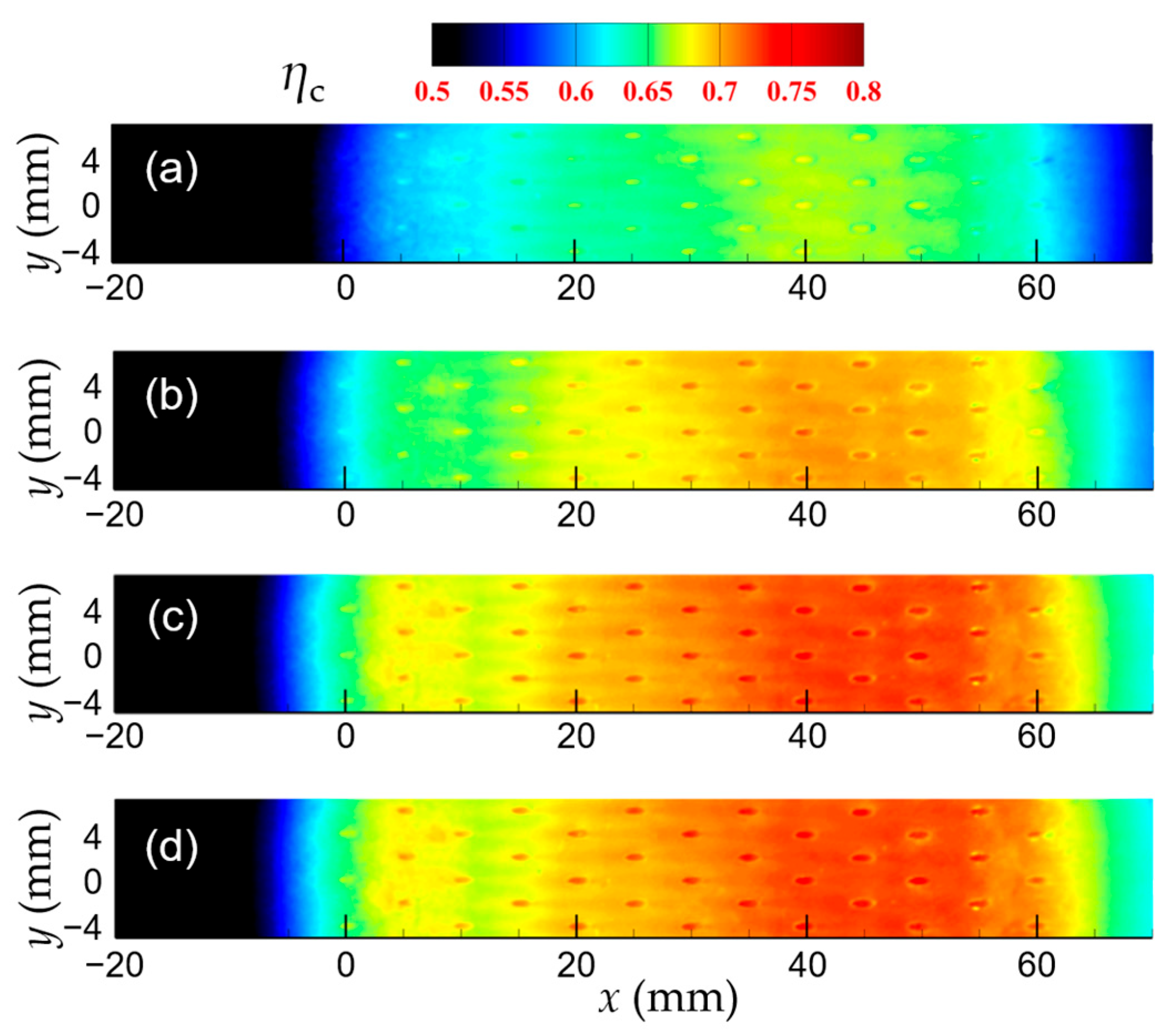

3.1. Measured Overall Cooling Effectiveness of Impingement–Effusion Configurations

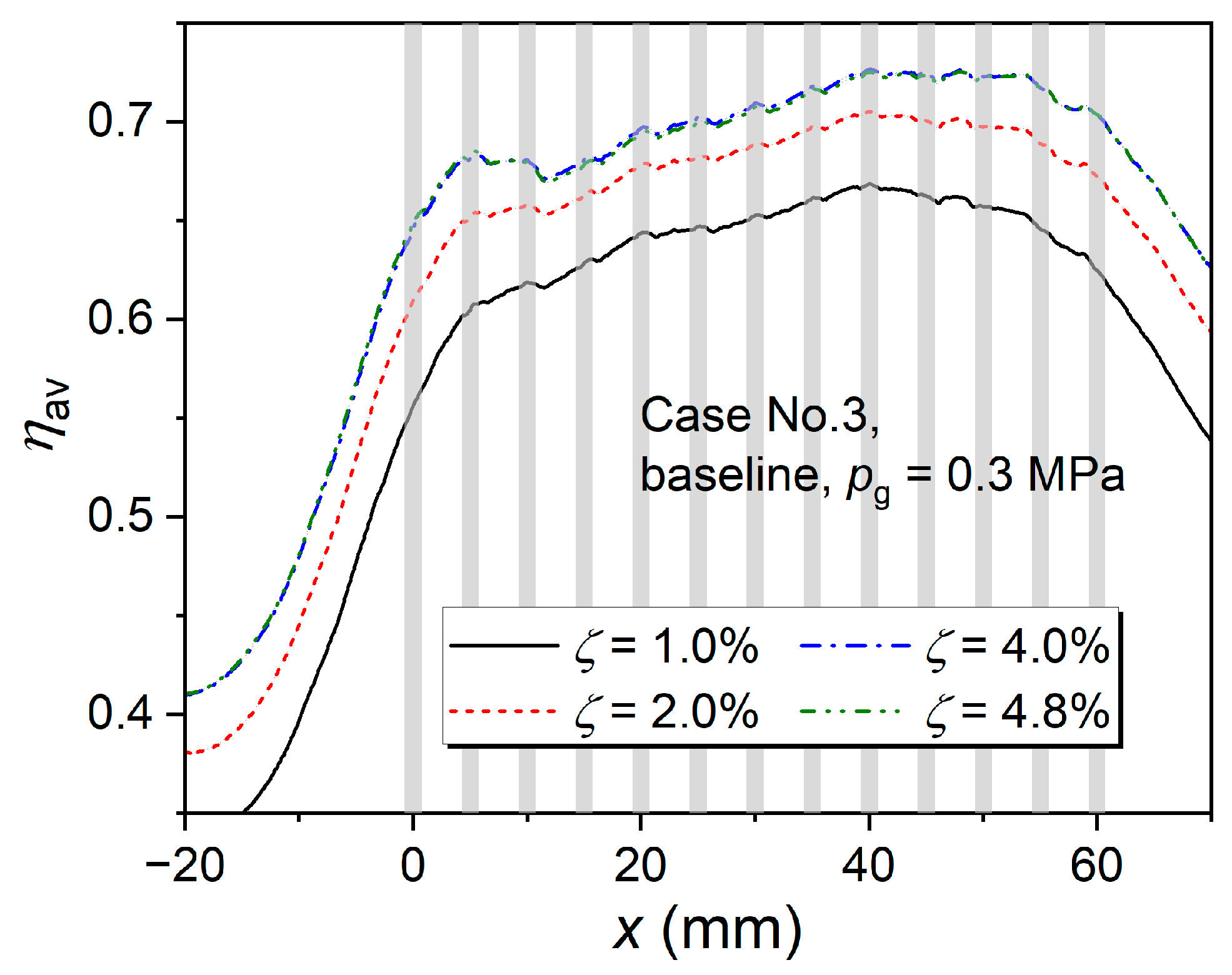

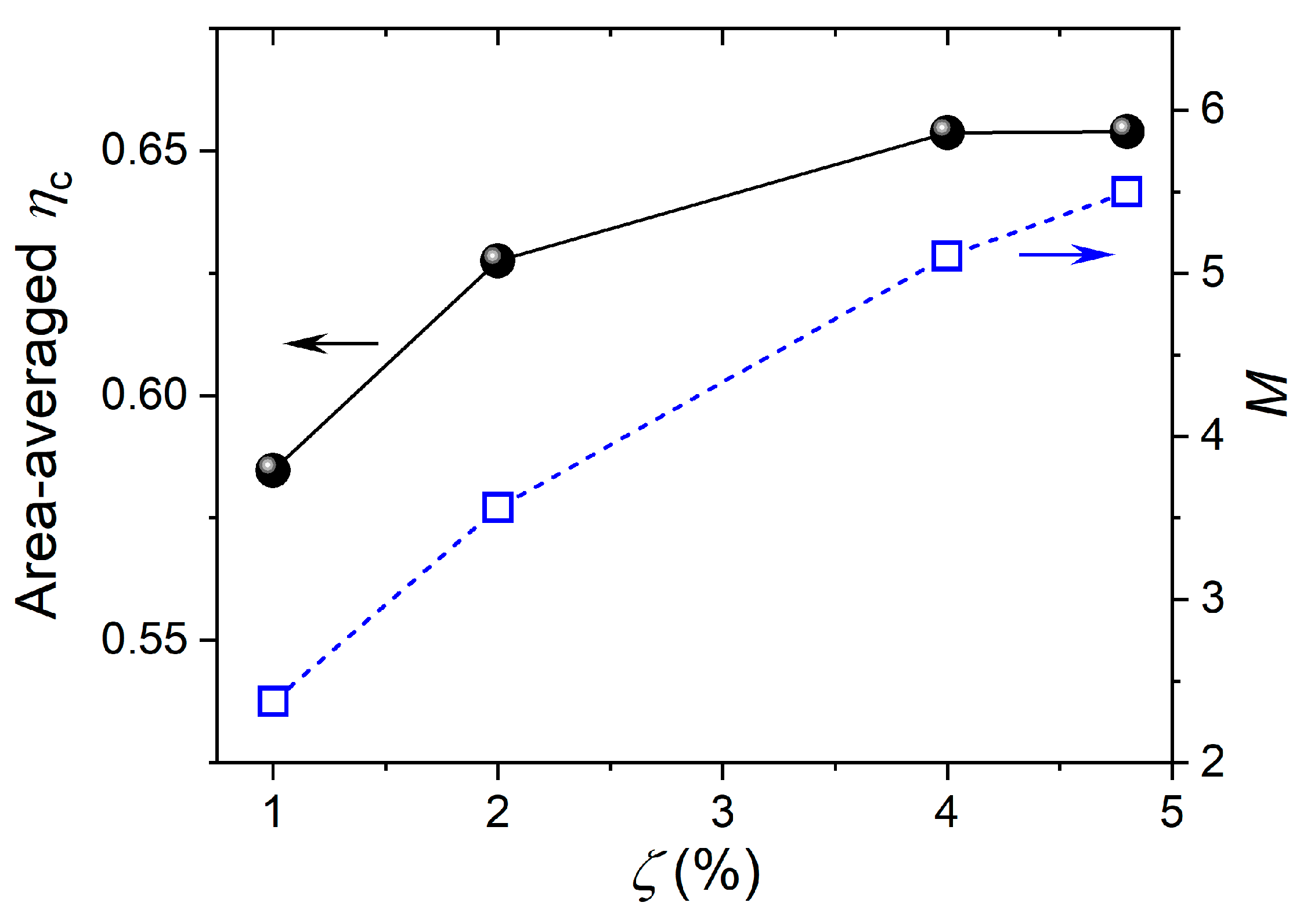

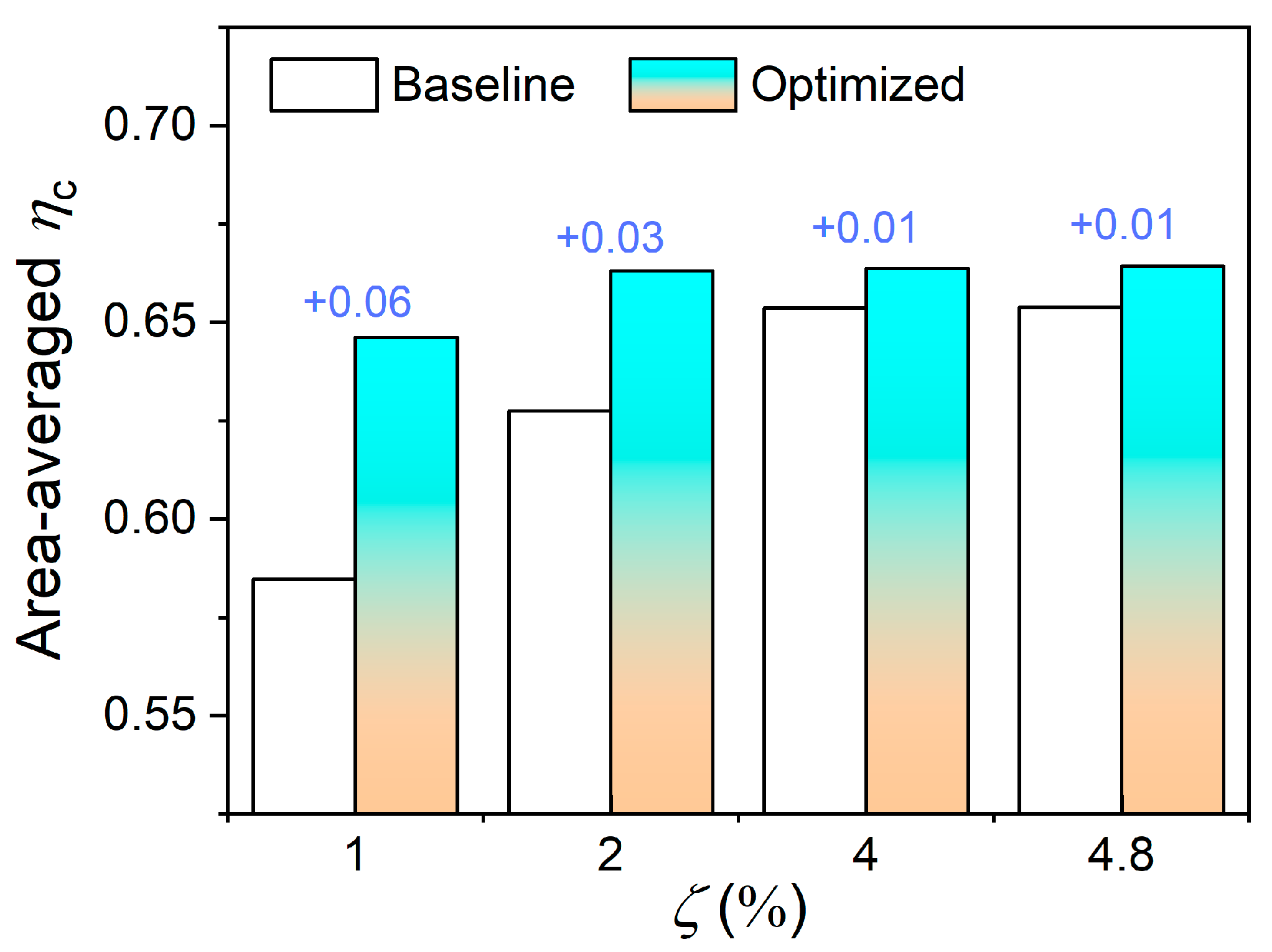

3.1.1. Effect of Pressure-Loss Coefficient

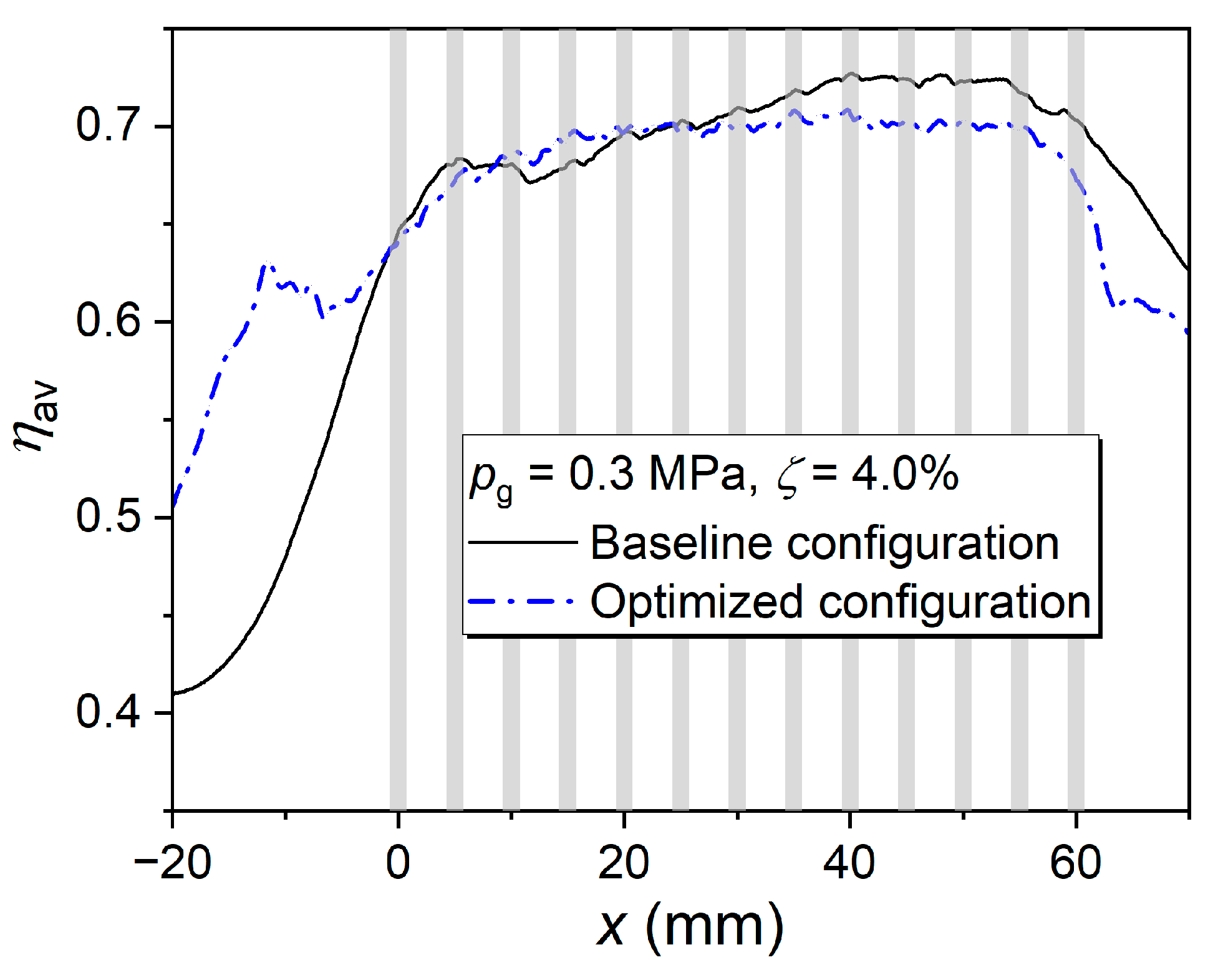

3.1.2. Effect of Initial Cooling Film

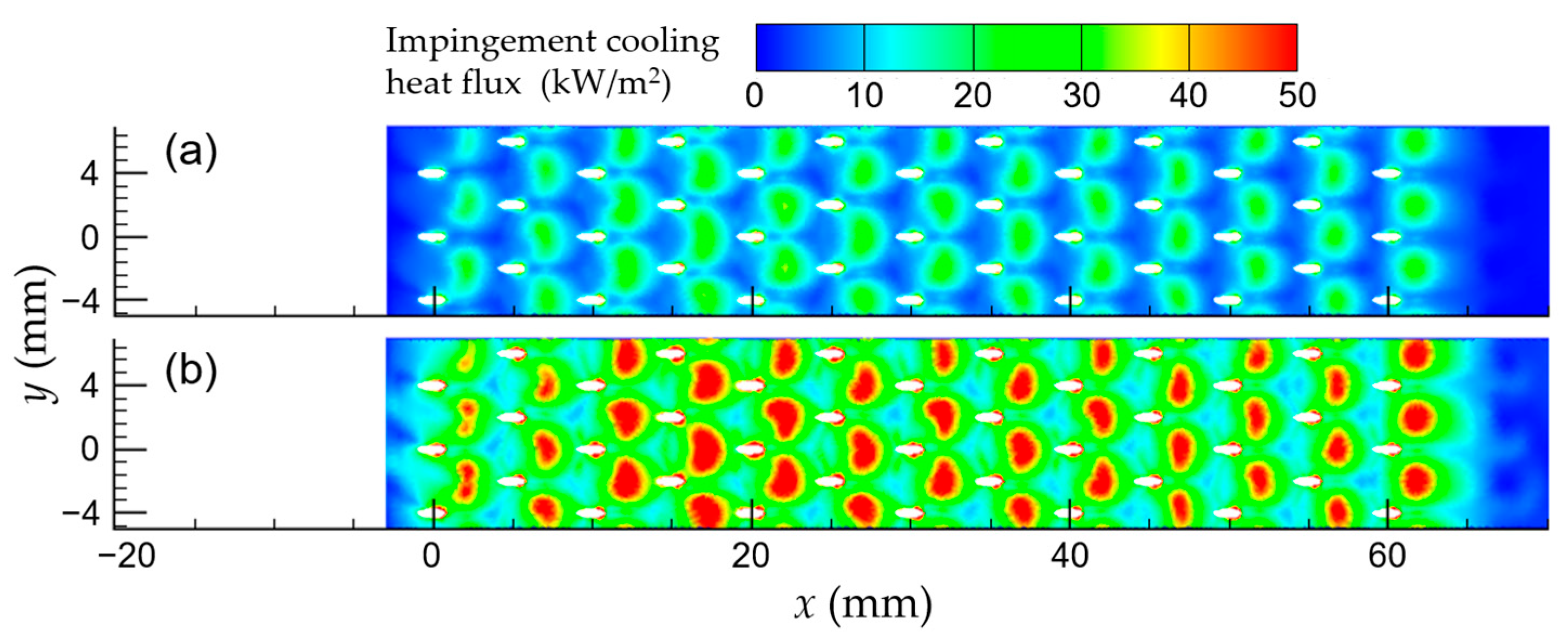

3.2. Insights into the Pressure Effects on Overall Cooling Performance

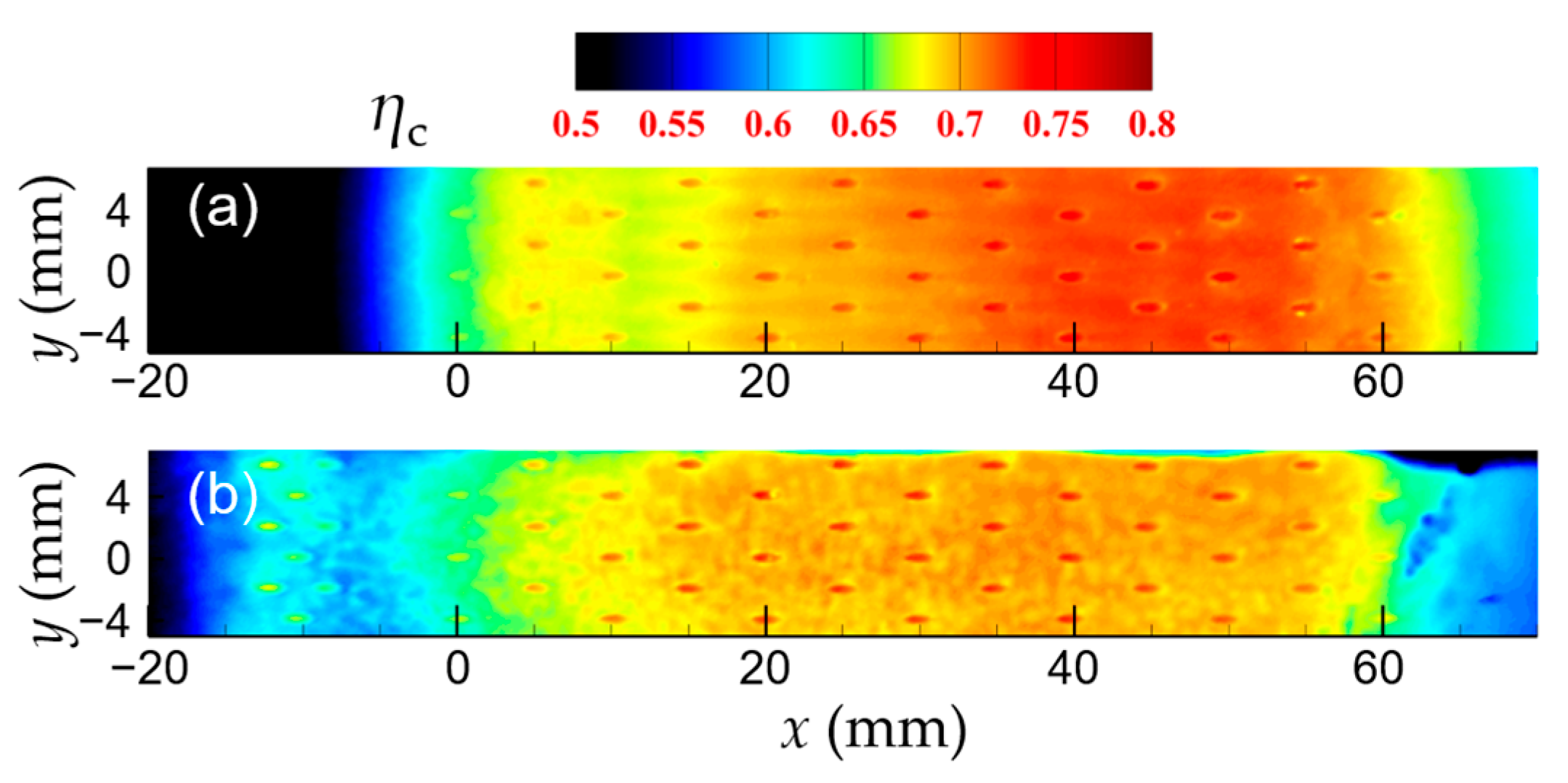

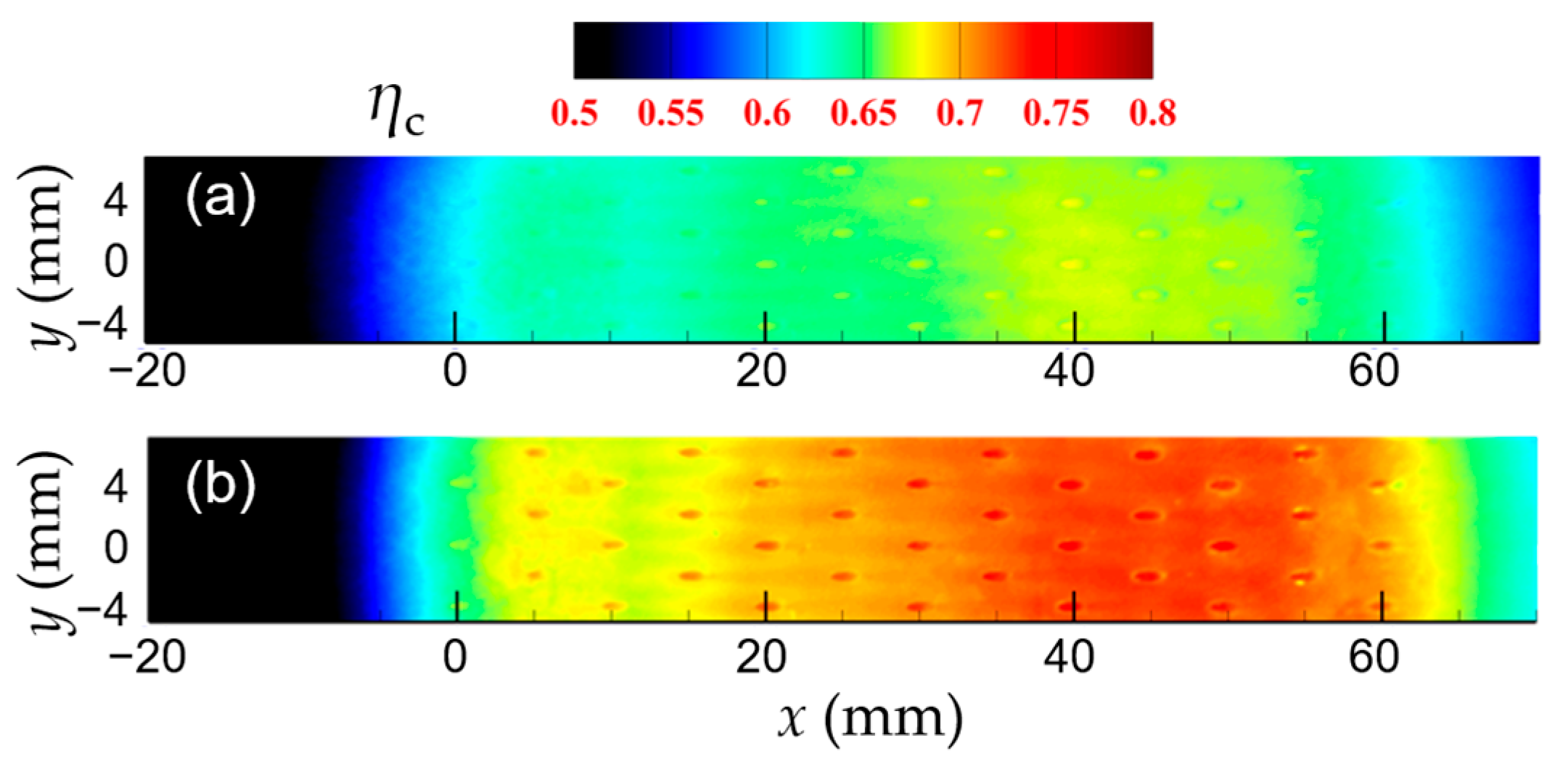

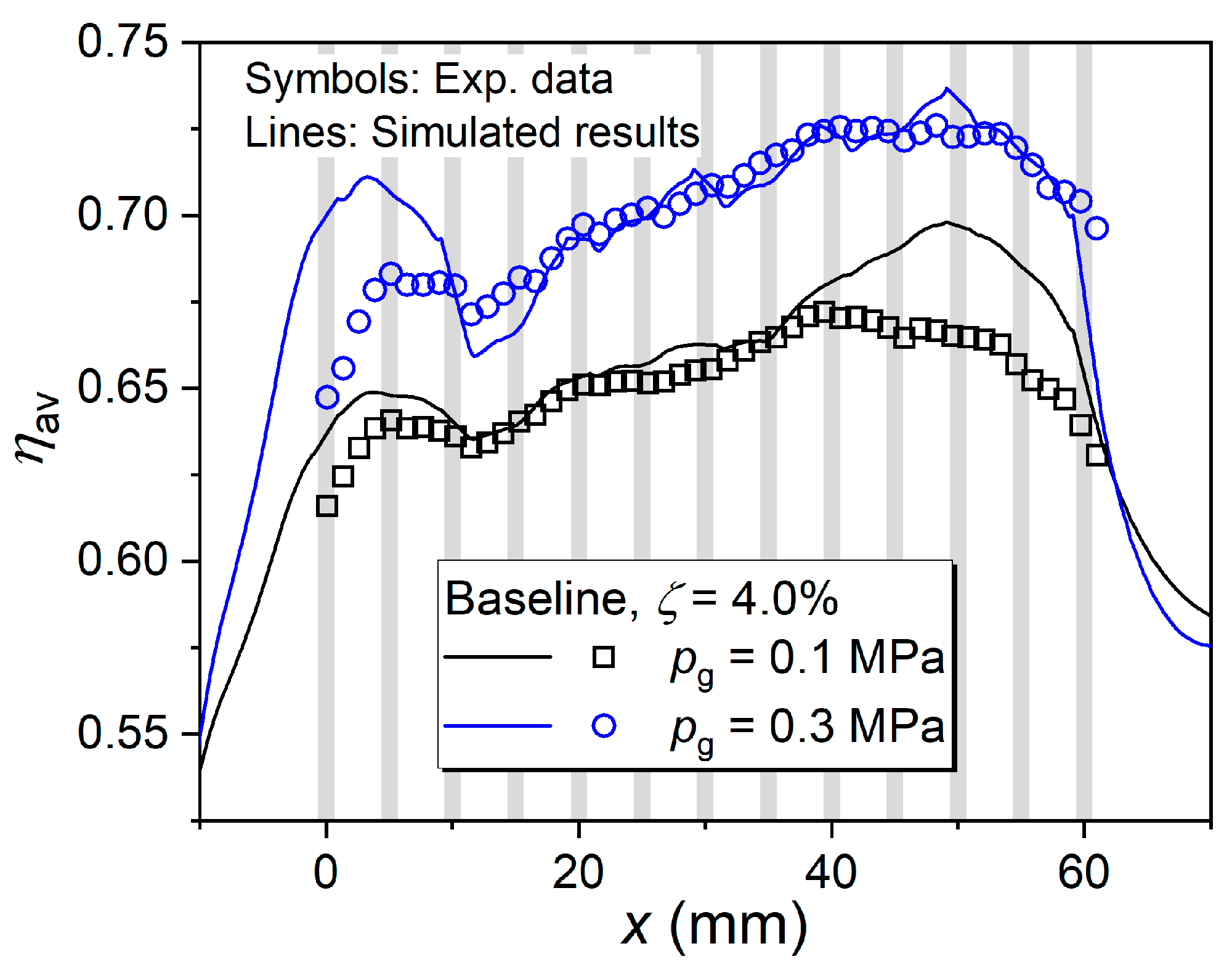

3.2.1. Comparisons of Cooling Effectiveness Under Atmospheric and Elevated Pressures

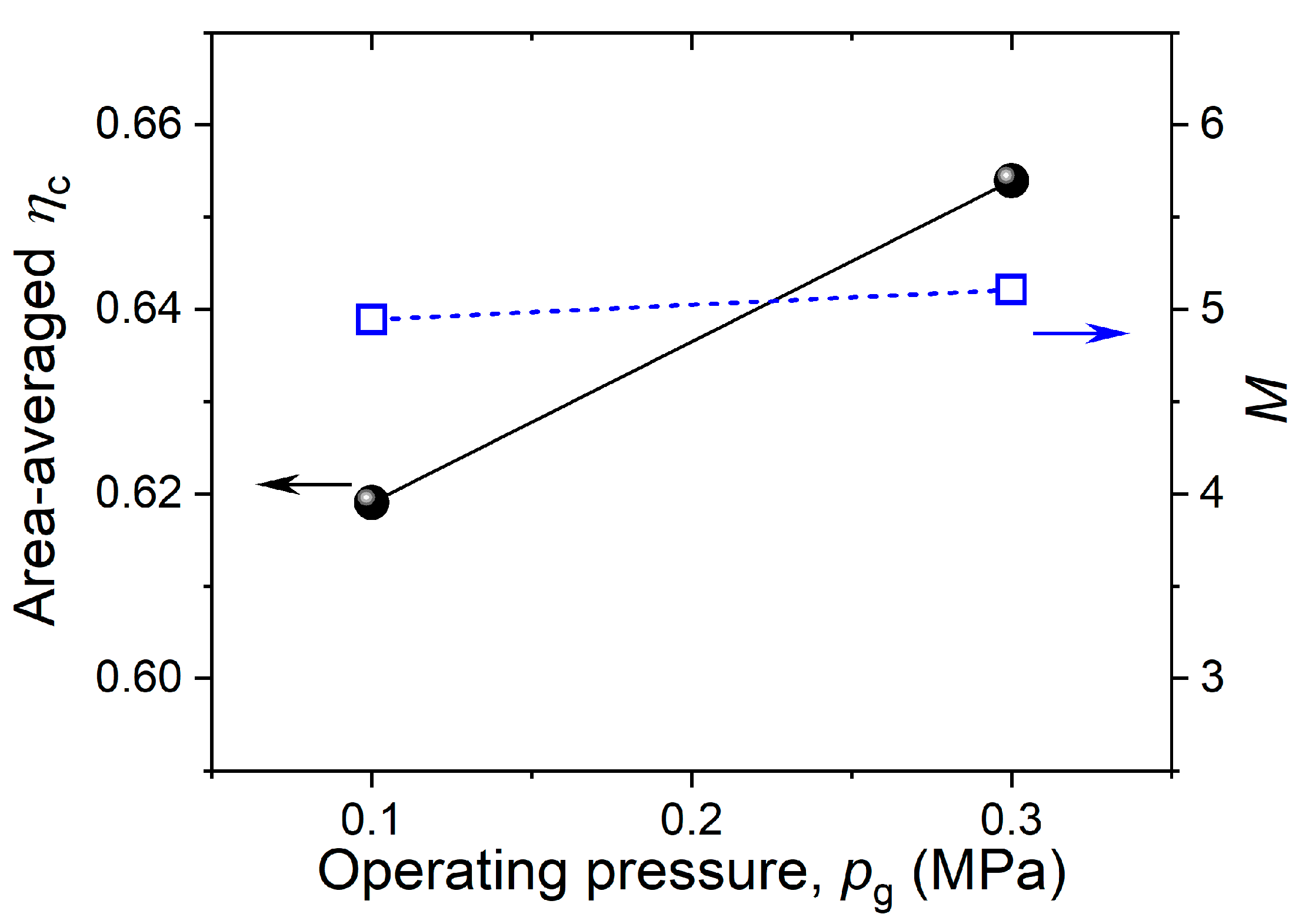

3.2.2. Contributions of Impingement and Convective Cooling Under Different Pressures

4. Conclusions

- Pressure drop strongly affects cooling effectiveness. Increasing the pressure drop across the impingement wall enhances jet momentum and cooling-film attachment, thereby improving overall cooling. However, when the drop exceeds about 4%, further gains diminish, as excessive blowing weakens cooling-film adhesion.

- Initial film-cooling addition redistributes coolant flow, slightly reducing local peak effectiveness but broadening surface protection and improving cooling uniformity. Comparable effectiveness to the baseline case at a high pressure drop can thus be achieved with lower coolant consumption.

- Elevated operating pressure substantially enhances cooling persistence and stability. Higher gas density increases jet momentum flux, promotes coherent impingement, and stabilizes cooling-film coverage, yielding greater overall effectiveness compared to the same at atmospheric pressure.

- Blowing-ratio-based similarity fails to account for pressure-dependent density and jet-mainstream interactions. Reliable scaling from laboratory to engine conditions, therefore, requires explicit inclusion of pressure effects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bunker, R.S. Gas turbine cooling: Moving from macro to micro cooling. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2013: Turbine Technical Conference and Exposition, San Antonia, TX, USA, 3–7 June 2013. V03CT14A002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, D.H.; Choi, J.H.; Cho, H.H. Heat (mass) transfer on effusion plate in impingement/effusion cooling systems. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 2003, 17, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Liu, C.-L.; Ye, L.; Wang, R.; Niu, J.; Zhai, Y. Effects of impingement gap and hole arrangement on overall cooling effectiveness for impingement/effusion cooling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 152, 119449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.-J.; Liu, C.-L.; Liu, H.-Y.; Xiao, X.; Lin, J.-F. Theoretical and experimental analysis of overall cooling effectiveness for afterburner double-wall heat shield. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 176, 121360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, D.; You, R.; Zou, Y.; Liu, S. Numerical investigation of the effects of the hole inclination angle and blowing ratio on the characteristics of cooling and stress in an impingement/effusion cooling system. Energies 2023, 16, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Z. Comparisons between forward- and backward-inclined film injection over an effusion wall with internal jet-array impingement: Cooling effectiveness, heat transfer, and analytical model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 262, 125280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wan, C. Multiple-jet impingement heat transfer in double-wall cooling structures with pin fins and effusion holes. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 133, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Liu, C.; Li, X. Analysis of flow characteristics and cooling performance of a novel impingement/effusion structure with bypass hollow holes. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 105150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, Y.; Lao, X.; Chen, Y.; Dong, L. Flow and heat transfer analysis on impingement/effusion cooling configuration including jet orifices with conformal pins. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 076122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhu, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, R.; Wu, Z.; Yao, C. Numerical investigation of fow and heat transfer in vane impingement/effusion cooling with various rib/dimple structure. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 32, 1357–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.; Verhiel, J.; McCaldon, K. Low emission technology for small aviation gas turbine engines. In Proceedings of the AIAA International Air and Space Symposium and Exposition: The Next 100 Years, Dayton, OH, USA, 14 July 2003. AIAA 2003-2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollworth, B.R.; Lehmann, G.; Rosiczkowski, J. Arrays of impinging jets with spent fluid removal through vent holes on the target surface, part 2: Local heat transfer. J. Eng. Power 1983, 105, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Q.; Du, Q.; Zhou, W.; Peng, D.; Liu, Y. A comprehensive heat transfer investigation for impingement/effusion cooling under crossflow conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 220, 124950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.H.; Rhee, D.H. Local heat/mass transfer measurement on the effusion plate in impingement/effusion cooling systems. J. Turbomach. 2001, 123, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollworth, B.R.; Dagan, L. Arrays of impinging jets with spent fluid removal through vent holes on the target surface—Part 1: Average heat transfer. J. Eng. Power 1980, 102, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.H.; Rhee, D.H.; Goldstein, R.J. Effects of hole arrangements on local heat/mass transfer for impingement/effusion cooling with small hole spacing. J. Turbomach. 2008, 130, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.E.; Asere, A.A.; Hussain, C.I. Transportation and impingement/effusion cooling of gas turbine combustion chambers. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Air Breathing Engines, Beijing, China, 2–6 September 1985; pp. 794–803. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, G.E.; Aldabagh, A.M.; Asere, A.A.; Bazdidi-Tehrani, F.; Mkpadi, M.C.; Nazari, A. Impingement/effusion cooling. In AGARD, Heat Transfer and Cooling in Gas Turbines; AGARD: Neuilly sur Seine, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, R.; Xi, W. Parametric and correlation study of effusion cooling applied to gas turbine blades. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ao, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, T.; Li, F. Improving film cooling efficiency with lobe-shaped cooling holes: An investigation with large-eddy simulation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, H.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, D. Conjugate heat transfer advancements and applications in aerospace engine technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, M.K.; McWaters, M.A.; Bogard, D.G.; Lemmon, C.A.; Thole, K.A. Full-coverage film cooling with short normal injection holes. J. Turbomach. 2001, 123, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, D.H.; Nam, Y.W.; Cho, H.H. Local heat/mass transfer with various rib arrangements in impingement/effusion cooling system with crossflow. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2004: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Vienna, Austria, 14–17 June 2004. GT2004-53686. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Cao, J.; Shi, R.; Hao, X.; Song, S. Experimental investigation on impingement-effusion film-cooling behaviors in curve section. Acta Astronaut. 2011, 68, 1782–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Moon, H.; Park, J.S.; Cho, H.H. Optimal design of impinging jets in an impingement/effusion cooling system. Energy 2014, 66, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Ligrani, P.M.; Vanga, S.R.; Park, H. Flow structure and surface heat transfer from numerical predictions for a double wall effusion plate with impingement jet array cooling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 183, 122049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS Fluent User Manual (Release 20.0); ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2020.

- Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Rao, Y.; He, J.; Qu, Y. Numerical investigation on conjugate heat transfer of impingement/effusion double-wall cooling with different crossflow schemes. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 155, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untuç, A.H.; Unverdi, S.O. Heat transfer enhancement by mitigating the adverse effects of crossflow in a multi-jet impingement cooling system in hexagonal configuration by coaxial cylindrical protrusion-guide vane pairs. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Shi, D.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Y. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of the turbine blade variable cross-section internal cooling channel with turning vane. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pg, MPa | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Tg, K | 473 | 473 | 473 |

| 4% | 4% | 1%, 2%, 4%, 4.8% | |

| ug, m/s | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Orifice arrangement | baseline | optimized | baseline |

| General Variables, ϕ | Diffusion Coefficients, Γ | Source Term, S |

|---|---|---|

| u, v, w (uj, j = 1–3) | ||

| T |

| pg (MPa) | Gc (kg/(m2·s·MPa)) | Cdo | M | Qimp (W/m2) | Qeff (W/m2) | Qimp/pg (W/(m2·MPa)) | Qeff/pg (W/(m2·MPa)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 5.32 | 0.502 | 5.1 | 9629 | 3095 | 96,292 | 30,955 |

| 0.3 | 5.88 | 0.556 | 5.6 | 23,665 | 7025 | 78,549 | 23,417 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Li, W.; Jiang, J.; Lang, X.; Dai, J.; Lian, T.; Shi, X.; Li, W. Cooling Performance of Impingement–Effusion Double-Wall Configurations Under Atmospheric and Elevated Pressures. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010297

Zhang R, Li W, Jiang J, Lang X, Dai J, Lian T, Shi X, Li W. Cooling Performance of Impingement–Effusion Double-Wall Configurations Under Atmospheric and Elevated Pressures. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010297

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Rongxing, Wei Li, Jianbai Jiang, Xudong Lang, Jinxin Dai, Tianyou Lian, Xiaoxiang Shi, and Wei Li. 2026. "Cooling Performance of Impingement–Effusion Double-Wall Configurations Under Atmospheric and Elevated Pressures" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010297

APA StyleZhang, R., Li, W., Jiang, J., Lang, X., Dai, J., Lian, T., Shi, X., & Li, W. (2026). Cooling Performance of Impingement–Effusion Double-Wall Configurations Under Atmospheric and Elevated Pressures. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010297