1. Introduction

Urban scene classification based on high-resolution remote sensing images is of great significance in fields such as urban planning, power facility siting, and power grid safety monitoring [

1,

2]. It provides detailed information on the shapes, textures, and spatial structures of ground object in the urban scene, enhancing urban spatial cognition. High-resolution remote sensing imagery provides more detailed ground-level information, which is crucial for identifying various urban functional areas and enhancing fine-grained information extraction. Compared to low-resolution images, high-resolution imagery offers a greater amount of pixel data, enabling the capture of more detailed ground features, thus significantly improving the accuracy of urban scene classification. For specific tasks such as precise disaster monitoring, traffic flow analysis and site selection for energy facilities, the value of high-resolution imagery cannot be substituted by other data sources. However, accurately identifying both global and local features from diverse land-cover features remains a significant challenge.

Traditional remote sensing images classification relies on handcrafted feature and machine learning algorithms, such as the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method [

3]. These approaches perform well on lower-resolution data but face clear limitations with high-resolution remote sensing images. First, handcrafted features fail to fully represent the complex land-cover information, particularly when inter-class differences are subtle, leading to significant accuracy degradation. Second, traditional methods cannot effectively capture spatial and semantic features of the images. Moreover, they are highly sensitive to noise, which further restricting their applicability in high-resolution images classification.

In recent years, the rapid advancement of remote sensing technology has substantially improved the spatial resolution of imagery. It significantly enhances details such as the structures and boundaries of objects, but also introduces challenges in feature selection [

4]. Consequently, researchers have increasingly turned to advanced convolutional neural networks for high-resolution remote sensing images classification (e.g., FCN [

5], UNet [

6], UNet++ [

7], DeepLabv3+ [

8], and PSPNet [

9]). These networks can automatically learn hierarchical features, significantly improving classification performance. However, the fixed receptive field of convolutions limits their ability to capture global information, resulting in poor global semantic representation. To address this, the Transformer architecture, known for its strength in global information modeling, has been applied to high-resolution remote sensing images classification and achieved notable progress [

10,

11,

12]. Nevertheless, due to the quadratic computational complexity of the self-attention mechanism [

13], Transformers often impose high computational costs, making deployment in downstream tasks challenging. In response to the challenges posed by traditional convolutional neural networks and the high computational cost of Transformers, recent research has focused on developing more efficient Transformer-based models tailored to the needs of high-resolution remote sensing image classification. One such model is CMLFormer [

14], which leverages a hybrid approach combining local feature extraction with the global contextual awareness of Transformers. CMLFormer introduces a novel context-aware mechanism that efficiently captures both local and global information while minimizing computational complexity. A similar architecture is UNetFormer [

15]. It also adopts a method that combines CNN and Transformer, hoping to reduce computational complexity and enhance the feasibility of real-time tasks in this way. However, CMLFomer and UNetFormer retain the main structure of Transformer, which still limits the computational efficiency and inference speed of the model.

Table 1 shows the advantages and disadvantages of the existing methods.

To overcome this, researchers have explored a new deep learning architecture based on state space models (SSMs), namely visual state space models (VMamba) [

16]. VMamba employs a 2D cross-scan mechanism within the Mamba architecture to precisely capture relationships between pixels. Compared with Transformers, it provides stronger global modeling capability with only linear complexity, thereby reshaping the paradigm of global information modeling. VMamba has already been applied to remote sensing tasks such as change detection [

17], classification [

18], super-resolution reconstruction [

19], and cloud removal [

20], showing great potential. There are some of the latest structures such as CM-UNet [

21], which attempt to combine the CNN and VMamba architectures. However, enhancing the local feature perception capability of Mamba-based models remains an open question.

In summary, to more effectively capture global information while improving local feature perception, we propose a Global–Local Information Fusion Network (GLIFNet). GLIFNet adopts a dual-encoder architecture for feature extraction. Specifically, GLIFNet extracts features in parallel through CNN [

22] and VMamba. On the one hand, CNN structure excels at capturing local features and leveraging prior knowledge, enabling the extraction of fine-grained information. On the other hand, VMamba focuses on global feature modeling and can effectively capture long-term dependencies and global relationships in the data. The complementary strengths of these two models allow for a more comprehensive and effective feature extraction process, mitigating the inherent limitations of relying on a single model. In addition, we design a Haar Wavelet Transform-based Attention Mechanism (HWTAM) [

23]. It leverages frequency-domain components of features to generate channel attention weights, thereby enabling refined fusion of local and global features. HWTAM effectively enhances the feature fusion effect of the CNN-Mamba hybrid structure, which further boosts the unique innovation of GLIFNet. The experimental results on the ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen datasets demonstrate that GLIFNet can effectively capture both global and local features of diverse land-cover types, achieving state-of-the-art performance in high-resolution remote sensing image classification.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

GLIFNet: We propose the GLIFNet, which integrates the CNN and the VMamba to more effectively combine local details with global semantics, significantly enhancing the performance of high-resolution remote sensing image classification.

- (2)

HWTAM: We propose the HWTAM for refined fusion of local and global features. Unlike traditional methods that directly rescale input features across channels, HWTAM rescales wavelet components of the input features, fully exploiting frequency-domain information to enrich feature representation and compute more accurate channel attention weights.

- (3)

Superior performance: The experimental results on the ISPRS Potsdam and the ISPRS Vaihingen datasets confirm that GLIFNet achieves state-of-the-art performance in high-resolution remote sensing image classification.

2. Methods

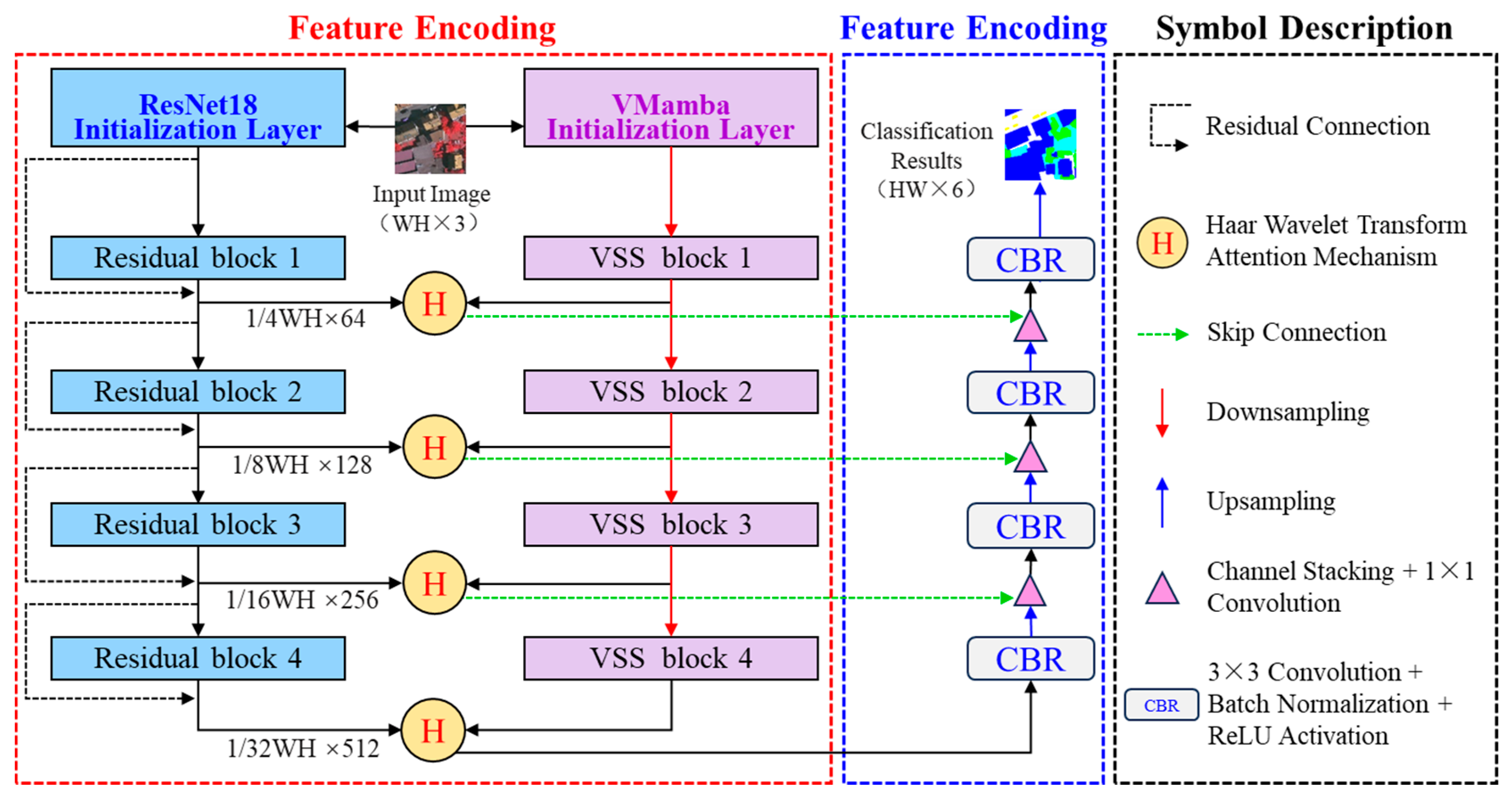

2.1. Overall Architecture of GLIFNet

The proposed GLIFNet model for high-resolution remote sensing image classification consists of two stages: feature encoding and decoding. The overall architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

In the feature encoding stage, ResNet18 and VMamba are employed to model local and global information, respectively. The residual connections of ResNet18 effectively alleviate the gradient vanishing and exploding problems in deep neural networks. In addition to alleviating the problems of vanishing gradients and explosion, the deep structure of ResNet18 ensures that the model can effectively capture features at different levels. By progressively refining local features through residual connections, ResNet18 enables efficient feature extraction while maintaining stability during training. ResNet18 is composed of four residual blocks, where convolution operations with local receptive fields are used to extract local features of the images layer by layer. VMamba, a novel image processing architecture based on state-space models, consists of four visual state-space (VSS) blocks. With its 2D cross-scanning mechanism and S6 model (where the Mamba architecture is abbreviated as the S6 model), VMamba ensures that each pixel in the feature maps can embed positional and semantic information from all other pixels, making it more suitable than Transformers for modeling long-range dependencies. In addition, VMamba can better handle the high computational demands of high-resolution images without losing important global context, making it an ideal solution for large-scale image analysis. Thus, VMamba is applied to progressively extract global features. The combination of ResNet18 and VMamba models has fully leveraged their respective advantages. This complementary combination enables the model to capture detailed information while accurately obtaining broader contextual information, thereby ensuring that the classification process is more accurate and efficient.

In addition, a Haar Wavelet Transform Attention Mechanism (HWTAM) is designed to focus on more discriminative local and global features, enabling refined fusion of both. GLIFNet outputs four layers of fused global–local features from the encoding stage to be used in decoding, with feature map dimensions of 1/4WH × 64, 1/8WH × 128, 1/16WH × 256, and 1/32WH × 512 (where W and H denote width and height, and 64, 128, 256, and 512 are the channel numbers).The decoding stage of GLIFNet consists of several 3 × 3 convolutions, batch normalization, ReLU activation functions, and upsampling, which restore the resolution of the fused features and reduce channel dimensions, ultimately generating classification results. To reduce information loss during feature extraction, skip connections are used to introduce shallow features from the encoding stage into the decoding stage. The algorithm implementation of GLIFNet can be referred to Algorithm A1 in

Appendix A.

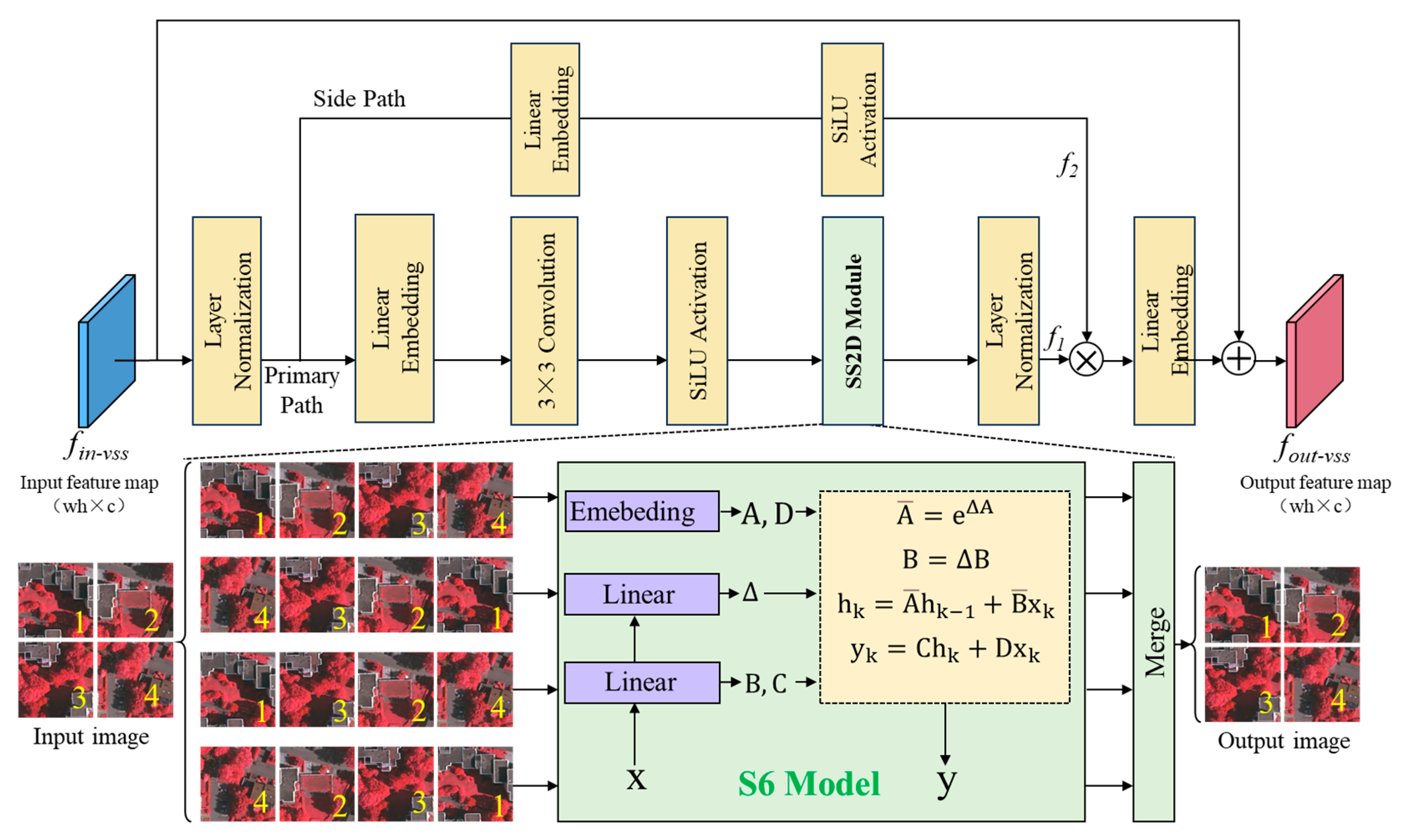

2.2. Visual State-Space Block

The visual state-space (VSS) block is a key component of VMamba, responsible for modeling pixel dependencies. Its structure is shown in

Figure 2.

After layer normalization, the input feature map is divided into a main path and an auxiliary path. In the main path, the feature map passes sequentially through linear embedding, 3 × 3 convolution, SiLU activation, the SS2D module, and layer normalization. In the auxiliary path, the feature map is processed by linear embedding and SiLU activation. The outputs from the two paths are then multiplied elementwise, followed by linear embedding and residual addition with the original input, producing the final output feature map. This process is defined as

where

f1 denotes the output from the main path,

f2 denotes the output from the auxiliary path,

LN denotes the layer normalization,

L denotes the linear embedding,

C3 denotes the 3 × 3 convolution,

S denotes the SiLU activation,

2D denotes the SS2D module, and × and + denote the elementwise multiplication and addition, respectively.

The SS2D module is the core of the VSS block. The input image is first divided into patches, which are unfolded into four directional sequences using the 2D cross-scanning mechanism (e.g., 1234, 4321, 1324, 4231 in

Figure 2). Each sequence is then processed by the S6 model for state-space modeling (detailed derivations of the S6 model are omitted here and can be found in the original reference [

16]). The specific process involves scanning in four directions: from top left to bottom right, from bottom right to top left, from top right to bottom left, and from bottom left to top right. This method captures the remote dependencies of each direction through a selective state space model and then merges the direction sequence to restore the two-dimensional structure. The cross-scanning mechanism and the S6 model ensure that each pixel can integrate both positional and semantic information from other pixels, thereby providing a global receptive field. Finally, the processed sequences from the four directions are merged to generate the final output. The parameter configuration of the VMamba architecture used in this study follows the default settings of the original version [

16].

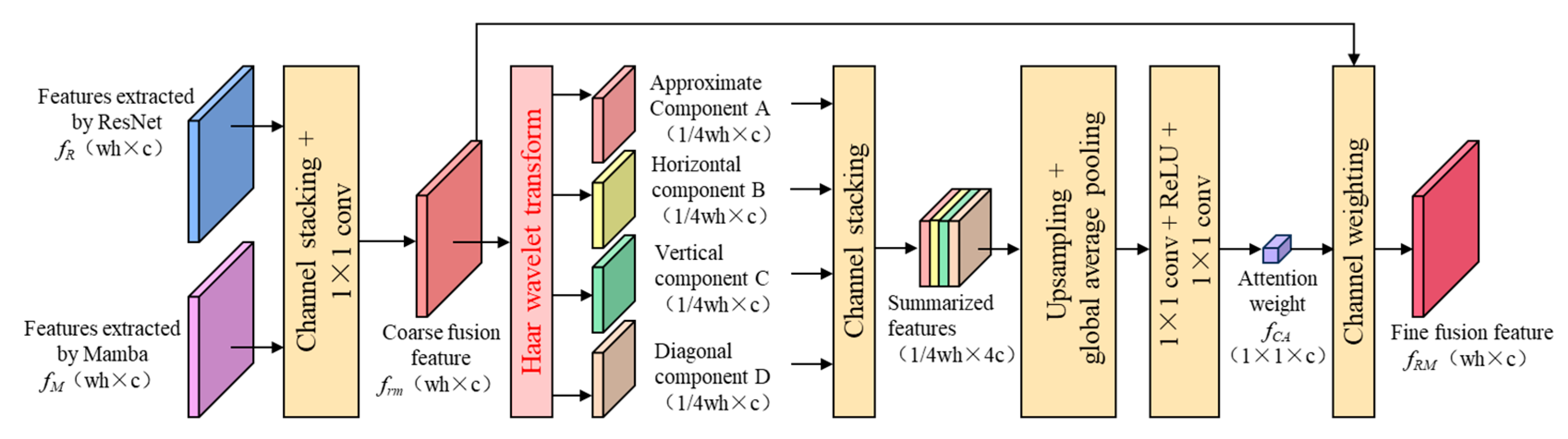

2.3. Haar Wavelet Transform Attention Mechanism

To finely fuse the local features extracted by ResNet18 and the global features extracted by VMamba, a Haar Wavelet Transform Attention Mechanism (HWTAM) is proposed, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

First, local and global features are coarsely fused using channel concatenation followed by a 1 × 1 convolution. Next, a Haar wavelet transform is applied to the coarsely fused features, producing four components: approximation, horizontal, vertical, and diagonal. For coarse fusion, we first perform channel stacking on the local and global features extracted by ResNet and Mamba. Then, a 1 × 1 convolution is used to reduce the dimensionality and fuse the channels of these two feature types, resulting in the coarse fusion features. No additional initialization is required for the coarse fusion features before the attention weighting step. The approximation component captures overall structural information, while the other three components capture directional details. These four components are then concatenated along the channel dimension and sequentially processed by upsampling, global average pooling, 1 × 1 convolution, ReLU activation, and another 1 × 1 convolution, resulting in channel attention weights based on wavelet components. Finally, the coarse features are multiplied by the channel attention weights to yield refined fused features. It is important to note that the component normalization is performed dynamically based on the intra-batch statistics of each wavelet component. Furthermore, to address the issue of resolution sensitivity, the scale of the Haar wavelet transform is uniformly fixed to a single level of decomposition. During wavelet decomposition, we use zero-padding and a stride of 1. The process is defined as

where Haar denotes the Haar wavelet transform,

A,

B,

C, and

D denote the approximation, horizontal, vertical, and diagonal components,

C1 denotes the 1 × 1 convolution,

S denotes the channel concatenation,

fR and

fM denote the local and global features from ResNet18 and VMamba,

R denotes the ReLU activation,

U denotes the upsampling,

fRM denotes the refined fused feature,

fCA denotes the channel attention weight, and

frm denotes the coarsely fused feature.

Unlike traditional attention mechanisms that directly scale feature channels, the proposed HWTAM computes channel attention weights by scaling wavelet components, thus leveraging frequency-domain information to enrich feature representations and achieve more accurate attention weighting.

2.4. Joint Loss Function

In remote sensing image classification, class imbalance often leads to insufficient learning of minority classes, ultimately affecting accuracy. To address this, a Joint Loss Function (

JL) is constructed by combining Cross-Entropy Loss (

CE) and Focal Loss (

F), enhancing the model’s focus on hard-to-classify samples. It is defined as

where

α ∈ [0, 1] is a weighting hyperparameter that adjusts the relative contributions of the two loss functions. In experiments,

α is set to 0.5. The

α serves as a hyperparameter to balance the contributions of each loss function, and setting it to 0.5 ensures that both losses contribute equally to the model’s training process.

Cross-Entropy Loss is one of the most commonly used loss functions for semantic segmentation, effectively optimizing pixel-level classification. However, under severely imbalanced class distributions, it tends to bias toward majority classes. It is defined as

where

C denotes the number of classes,

yc denotes the ground-truth label, and

pc denotes the predicted probability.

Focal Loss builds upon cross-entropy by introducing a modulation factor that emphasizes hard samples (low-confidence predictions), thus improving feature learning in class-imbalanced scenarios. It is defined as

where

β > 0 is the modulation factor. When

β = 0, the focal loss function simplifies to the standard cross-entropy loss, where all examples contribute equally to the total loss. In contrast, when

β > 0, the focal loss introduces a weighting factor that increases the emphasis on misclassified examples. This adjustment helps the model better handle class imbalance by focusing more on harder-to-classify instances, thereby improving overall performance. In experiment, the

β is set to 1, which is widely adopted in the literature [

24]. This choice provides a balanced contribution between easy and difficult examples, making it a reasonable starting point for the focal loss function.

It is important to emphasize that the Joint Loss Function is utilized in the model training process as an optimization mechanism, serving as a reference metric to facilitate the model’s learning.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Datasets

To verify the effectiveness of GLIFNet, experiments were conducted on two benchmark datasets: ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen. The ISPRS Potsdam dataset contains 38 high-resolution aerial images of the urban area of Potsdam, Germany, each with a size of 6000 × 6000 pixels and a spatial resolution of 5 cm. It is categorized into six classes: impervious surface, low vegetation, trees, cars, buildings, and clutter/background. The ISPRS Vaihingen dataset, collected from the Vaihingen region in Germany, consists of 33 high-resolution aerial images with sizes ranging between 2000 × 4000 pixels and a spatial resolution of 9 cm, and the same six classes. Both of these datasets contain high-resolution imagery and pixel-level annotations, making them ideal for remote sensing image analysis and computer vision research. Additionally, the datasets encompass a wide range of land cover types, which are well-suited for the precise extraction of buildings and urban elements.

LandCover.ai is an open-source remote sensing dataset designed for the automatic extraction of building, forest, water body, and road information from aerial imagery. The dataset is derived from aerial imagery of Poland in Central Europe, with RGB three-band images. It contains five categories: buildings, trees, water, low vegetation and roads. The dataset includes 33 orthophotos with a spatial resolution of 25 cm/pixel (approximately 9000 × 9500 pixels) and 8 orthophotos with a spatial resolution of 50 cm/pixel (approximately 4200 × 4700 pixels), covering a total area of 216.27 square kilometers. The primary advantage of this dataset is its provision of high-resolution aerial imagery and accurate pixel-level annotations, making it particularly suitable for the training and evaluation of models intended for high-precision map generation.

Table 2 shows the comparison among the datasets adopted in the study.

To fit memory constraints and improve training efficiency, all images were cropped into patches of 512 × 512 pixels. Finally, 3800 and 562 image patches were obtained for ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen, respectively. These patches were randomly split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 6:2:2. This split follows a standard approach in deep learning research. In this process, 60% of the data is allocated for training the model, ensuring that the model has enough samples to learn the underlying patterns of the data; 20% is used for validation, primarily to tune the model during training, including hyperparameter selection and avoiding overfitting; finally, 20% of the data is reserved for testing, allowing for the evaluation of the model’s generalization ability on unseen data. To prevent overfitting and improve generalization, data augmentation techniques such as random channel swapping, 90° clockwise rotation, and horizontal flipping were applied to the training set.

3.2. Experimental Settings

All experiments are performed on the same workstation with a 12 GB NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080Ti GPU, and the operating system kernel is Linux. The models were implemented and trained using the PyTorch deep learning framework. The version of Python, PyTorch and CUDA are 3.8, 1.7 and 10.1, respectively.

For optimization, the Adam optimizer and the joint loss function were used to ensure efficient gradient updates, fast convergence, and stable training. The batch size was set to 4 to balance stability and generalization under limited computational resources. The initial learning rate was set to 0.0001 to avoid gradient explosion or vanishing. The maximum number of training epochs was set to 100 to ensure sufficient feature learning and convergence. A step decay strategy was applied to gradually reduce the learning rate during training, decreasing it by 10% every 10 epochs. This strategy helped avoid local optima and improved overall training performance and generalization.

For accuracy evaluation, the overall accuracy (OA) and the mean F1 score (mF1) were adopted to assess the overall performance, while per-class F1 scores (F1) were computed to measure class-specific performance [

25]. OA measures the ratio of correctly predicted pixels, while F1 is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. mF1 is the average F1 score across all classes.

To demonstrate the advantages of the proposed method, GLIFNet was compared against several state-of-the-art semantic segmentation models: FCN [

5], UNet [

6], UNet++ [

7], DeepLabv3+ [

8], PSPNet [

9], UNetFormer [

15], CM-UNet [

21], MobileNetV2 [

26] and UANet [

27] with all models trained under default settings.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Results

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the accuracy comparison of different models on ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen, respectively. On ISPRS Potsdam, GLIFNet achieved the best F1-scores in all categories except trees (where it was only 0.04% lower than PSPNet). The slight decrease in performance for the trees category can be attributed to the complex and varying texture of trees in the dataset, which may pose challenges for accurate classification. Both mF1 and OA showed significant improvements, with mF1 exceeding the best compared model by 1.26% and OA by 2.28%. On ISPRS Vaihingen, GLIFNet achieved the best F1 scores across all categories, with mF1 and OA improving by 1.91% and 1.58%, respectively, compared to the best compared model. These results not only demonstrate GLIFNet’s superior performance on this benchmark dataset but also highlight its capability to effectively address the challenges posed by varying land cover types and complex urban environments. The consistent improvements in performance across both datasets further emphasize GLIFNet’s robustness and its potential for generalization. These findings suggest that GLIFNet is highly applicable to a broad range of high-resolution remote sensing tasks, showcasing its versatility in handling diverse and intricate imagery.

Further experiments on varying image resolutions could provide deeper insights into its scalability and robustness.

Table 5 presents the accuracy comparison of different models on LandCover.ai. GLIFNet demonstrated the best classification performance in most scenarios. Its mF1 score and OA were both the highest among the participating comparison models, achieving excellent results of 88.39% and 92.23%, respectively. It was 0.3% and 0.28% higher, respectively, than the optimal model participating in the comparison. In terms of F1 scores for individual classes, GLIFNet only underperformed DeepLabv3+ in the “Buildings” category (where it was 2.32% lower). The classification performance for the “Buildings” category was relatively poor, which may be attributed to the limited amount of training data for this category in the dataset. The experimental results on the LandCover.ai dataset demonstrate the effectiveness of GLIFNet. It achieves robustness and accuracy in multi-class classification of remote sensing images. This is accomplished through the combination of CNN and SSM structures. Additionally, the incorporation of Haar Wavelet Transform Attention further enhances its performance.

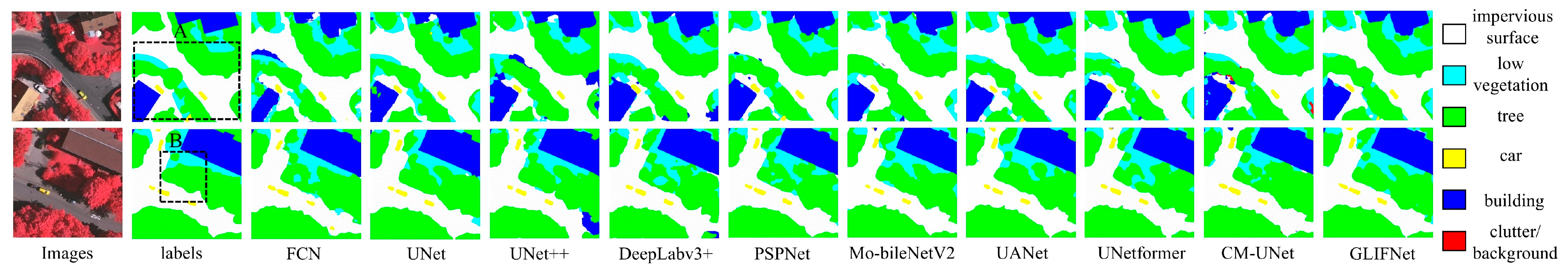

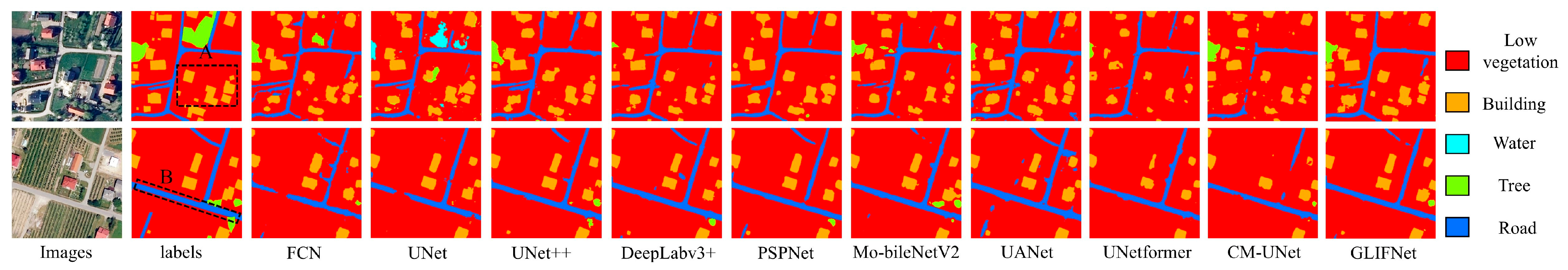

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the visual comparison of classification results on ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen. There are significant differences in ground features between Potsdam and Vaihingen. For Potsdam images, small objects on the ground are the difficulty in accurate classification. The difficulty in Vaihingen image classification lies in its complex interlacing and occlusion of vegetation. In ISPRS Potsdam, all compared models except GLIFNet suffered from obvious building misclassification or clutter omission in region A, and failed to fully detect vehicles in region B. In addition, the classification results of GLIFNet show better structural integrity of ground objects. The rate of incorrect classification is also significantly lower than that of other compared models. In ISPRS Vaihingen, all compared model exhibited building misclassification in region A, while grassland in region B contained evident holes or incorrect connectivity. In contrast, GLIFNet showed fewer misclassifications in both regions and successfully preserved the connectivity of the grassland without generating holes.

Figure 6 illustrate the visual comparison of classification results on LandCover.ai. In the LandCover.ai dataset, all models involved in the comparison showed some differences in structural restoration within region A. However, the classification results of GLIFNet performed better in terms of maintaining the structural integrity of buildings. In region B, some models experienced disconnection or deformation issues, whereas GLIFNet did not exhibit such problems. The visual comparison of the classification results and the quantitative indicators of the experiment mutually confirmed each other. Overall, GLIFNet achieved the fewest misclassifications and produced the most accurate results.

3.4. Ablation Study

To validate the contributions of ResNet18, VMamba, and HWTAM on GLIFNet, we conducted ablation studies using two datasets from ISPRS. The results are shown in

Table 6. When using only ResNet18 or only VMamba in the encoder, both mF1 and OA decreased by more than 0.71% on both datasets compared with using both together. This is because relying on ResNet18 or VMamba alone cannot simultaneously capture detailed local information and global semantic information. Furthermore, when both ResNet18 and VMamba were used but without HWTAM, performance was also reduced. Incorporating HWTAM (i.e., full GLIFNet) improved mF1 and OA by 0.72% and 0.52% on ISPRS Potsdam, and by 0.82% and 0.69% on ISPRS Vaihingen, respectively. These results confirm that ResNet18, VMamba, and HWTAM each contribute significantly to GLIFNet’s performance.

Table 7 demonstrates the performance of three frequency transformation methods—Fourier, Laplace, and Haar in GLIFNet. The results show that the Haar wavelet transform achieved the best accuracy. This is mainly because Haar transforms combine computational simplicity with spatial locality. Additionally, it naturally captures structural changes within local regions, providing more discriminative frequency feature representations for attention weights. In contrast, the Fourier transform focuses on global frequency spectra and weakens spatial details, while the Laplace transform is more sensitive to noise. Both of these methods are less directly effective than the Haar wavelet transform in adapting to the requirements of the attention mechanism task.

Table 8 shows the impact of Mamba blocks and CNN blocks on the performance of GLIFNet under different depth configurations. The results indicate that the model achieves optimal performance when the depth configuration for the four stages is (2, 2, 4, 2). This suggests that network performance does not simply increase or decrease monotonically with depth, but rather requires a balance between depth and feature complexity at different stages. Specifically, shallower initial stages help preserve more spatial details, while deeper intermediate stages effectively extract high-level semantic features and model long-range dependencies. This optimal configuration reflects the effectiveness of hierarchical depth design, where different computational depths are applied at various feature extraction stages to achieve the best trade-off between overall efficiency and representational capacity.

3.5. Analysis of HWTAM Superiority

Attention mechanisms are widely used in computer vision for feature enhancement and fusion. To demonstrate the superiority of HWTAM in local–global feature fusion, three state-of-the-art attention mechanisms—CBAM [

28], SENet [

29], and TAM [

30]—were compared against HWTAM using two ISPRS datasets as examples. The classification accuracy of GLIFNet combined with different attention mechanisms is shown in

Table 9. The results reveal that HWTAM consistently achieved the best performance on both datasets across all evaluation metrics. On ISPRS Potsdam, HWTAM improved mF1 and OA by at least 0.52% and 0.40%, respectively. On ISPRS Vaihingen, the improvements were 0.68% and 0.84%, respectively. These findings confirm that HWTAM provides optimal local–global feature fusion, effectively enhancing classification accuracy in high-resolution remote sensing imagery.

3.6. Model Size and Efficiency Analysis

To assess the practicality of GLIFNet in the practical applications, the model size and FLOPs of different methods were compared, as shown in

Table 10. GLIFNet has a size of 44.26 MB, which is much smaller than FCN, DeepLabv3+, and PSPNet, and comparable to UNet and UNet++. Furthermore, GLIGNet’s FLOPs are only 10.21 G. This value is only marginally higher than the lightweight network MobileNetV2, comparable to UNetformer and CM-UNet, but significantly lower than the other compared networks. This indicates that GLIGNet achieves a moderate level in terms of both model scale and computational complexity. Considering its superior accuracy, this computational overhead is highly acceptable.

The training and inference times of the two ISPRS datasets as examples are shown in

Table 11. Specifically, training time and inference time refer to the training time per epoch and the inference time for the entire test set, respectively. In terms of training time, GLIFNet required 316s per epoch on ISPRS Potsdam and 38s per epoch on ISPRS Vaihingen. Regarding inference time, GLIFNet achieved 55 s and 14 s on the two datasets, respectively. It is evident that GLIFNet ranks among the faster models in both training and inference performance.

Overall, the model sizes and training times of all methods were within the same order of magnitude. Therefore, GLIFNet achieves a favorable balance between classification accuracy, model size, and training efficiency, providing an advanced foundation for practical remote sensing applications.

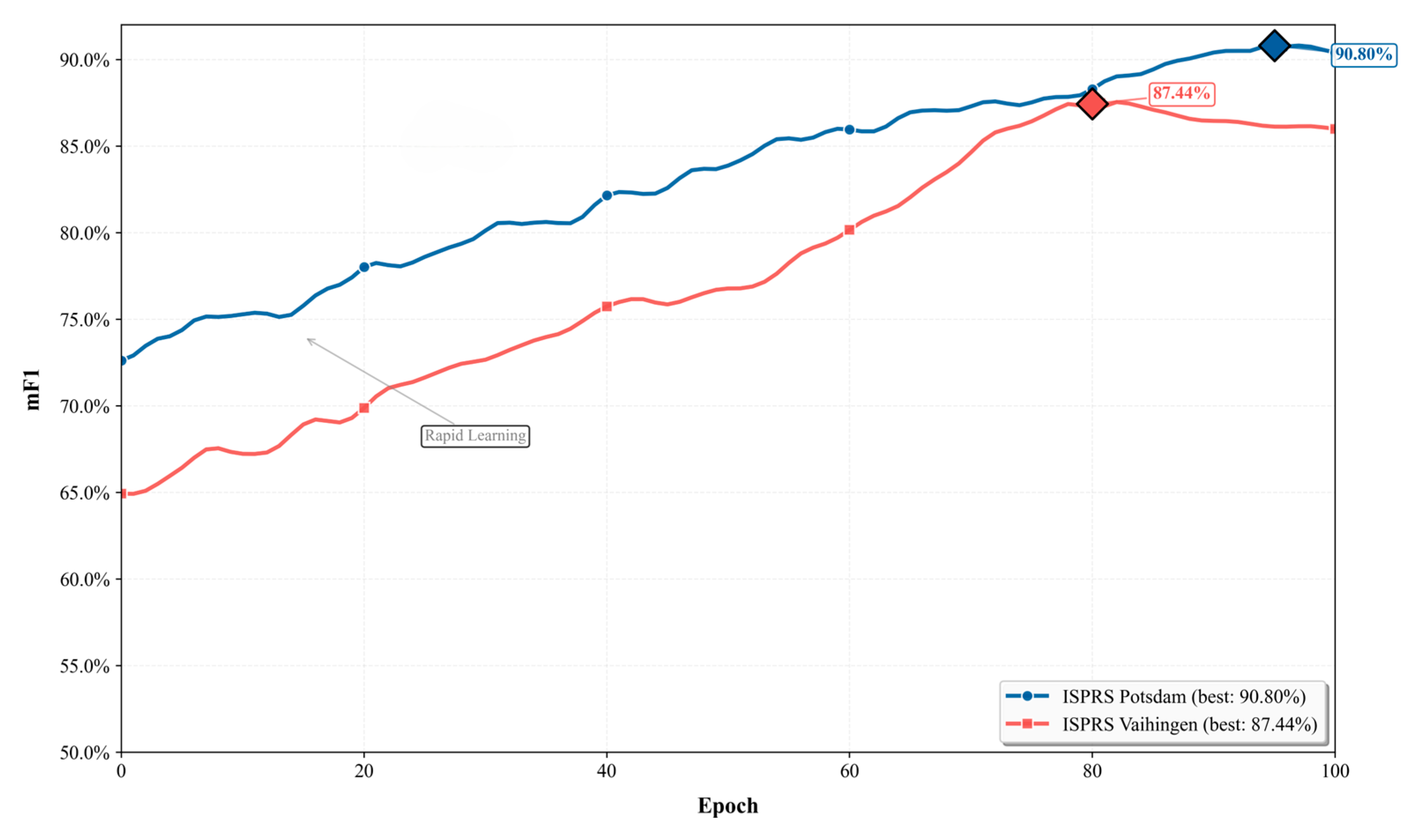

3.7. Training Process of GLIFNet

Figure 7 illustrates the convergence process of the validation set mF1 score for GLIFNet trained over 100 cycles on two ISPRS datasets. The blue curve represents the ISPRS Potsdam dataset, where performance starts from an initial value of approximately 73%. After a rapid learning phase, it steadily improves, ultimately reaching a peak of 90.80% around the 95th cycle, demonstrating strong learning capability and convergence stability. The red curve represents the ISPRS Vaihingen dataset, starting at approximately 65%. Its convergence rate is relatively gradual, reaching an optimal value of 87.44% around the 80th epoch before experiencing a slight decline. A noticeable performance gap of about 7.1% persists between the two curves during the mid-training phase (around the 50th epoch), reflecting the distinct learning dynamics of the model across different datasets. Overall, the model exhibits favorable convergence trends on both datasets, with the Potsdam dataset achieving significantly superior final performance compared to the Vaihingen dataset.

4. Conclusions

To address the limitations of CNNs and Transformers in modeling global information and computational complexity, respectively, the GLIFNet was proposed by combining ResNet18 and VMamba. ResNet18 captures local features to preserve detailed information, while VMamba extracts global features to model semantic dependencies. HWTAM further computes channel attention weights based on frequency-domain components, enabling refined fusion of local and global features. In addition, skip connections incorporate shallow features into the encoder for fusion with deeper features, reducing information loss.

The experimental results demonstrated that GLIFNet achieved mF1 scores of 90.08% and 87.44% on ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen, improving by 1.26% and 1.91% compared to baselines, respectively, while maintaining reasonable model size and computational efficiency. OA achieved 90.43% and 92.87%, respectively, on ISPRS Potsdam and ISPRS Vaihingen. It has improved by 2.28% and 1.58% compared to baselines. In the LandCover.ai experiment, GLIFNet achieved the best performance among the compared models, with an outstanding mF1 score of 88.39% and OA of 92.23%. Meanwhile, GLIFNet has also demonstrated the best performance in visual classification. The classification results demonstrate excellent structural integrity and accuracy. Moreover, HWTAM was shown to effectively enhance classification accuracy.

However, this study still has some limitations. First, the model struggles to identify highly heterogeneous urban features (such as small vehicle objects, vegetation, or weather shadows), primarily due to their highly nonlinear structural and spectral characteristics, which make it difficult for single-scale modeling to capture their complex semantics. Second, the CNN-Mamba hybrid architecture incurs high computational and memory costs when processing large-scale images. Additionally, the model exhibits sensitivity to hyperparameters such as image size and learning rate, which impacts its generalization capability. Future work should extend beyond enhancing local modeling to develop adaptive multi-scale fusion mechanisms, lightweight strategies, and physics-guided spectral analysis methods to improve model robustness, efficiency, and interpretability.