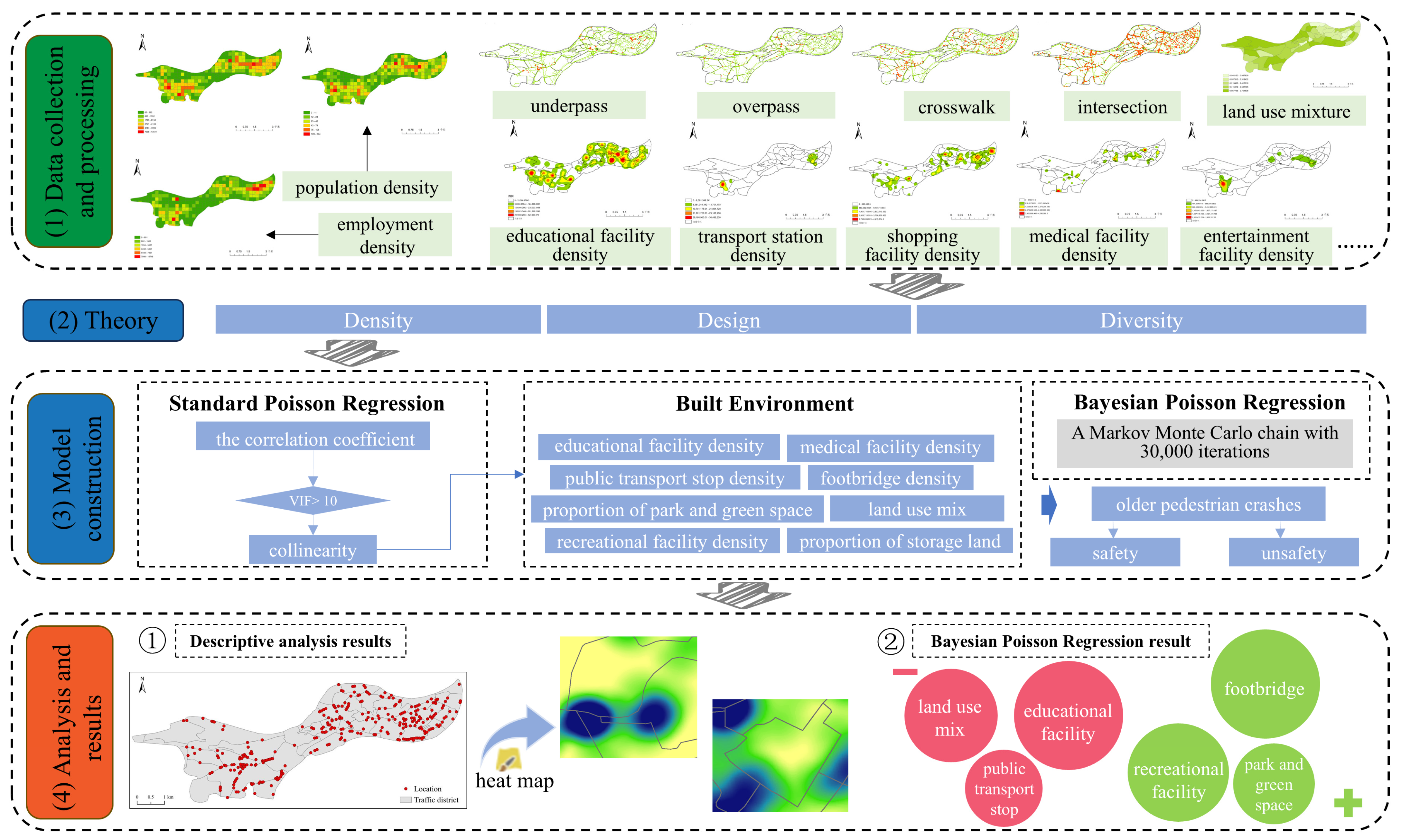

3.1. Research Framework

The conceptual framework of this study is illustrated in

Figure 1. The independent variable set (X) consists of built environment variables, which were collected and reconstructed from multiple data sources based on the “3Ds” theoretical framework (density, design, and diversity) [

36]. Among these independent variables, parameters representing pedestrian overpasses and underground passages—the most characteristic infrastructure elements in mountainous cities—have been incorporated. The target variable (Y) is the frequency of traffic accidents involving older adults, calculated from the traffic police patrol database within the study area and aggregated by traffic analysis zones.

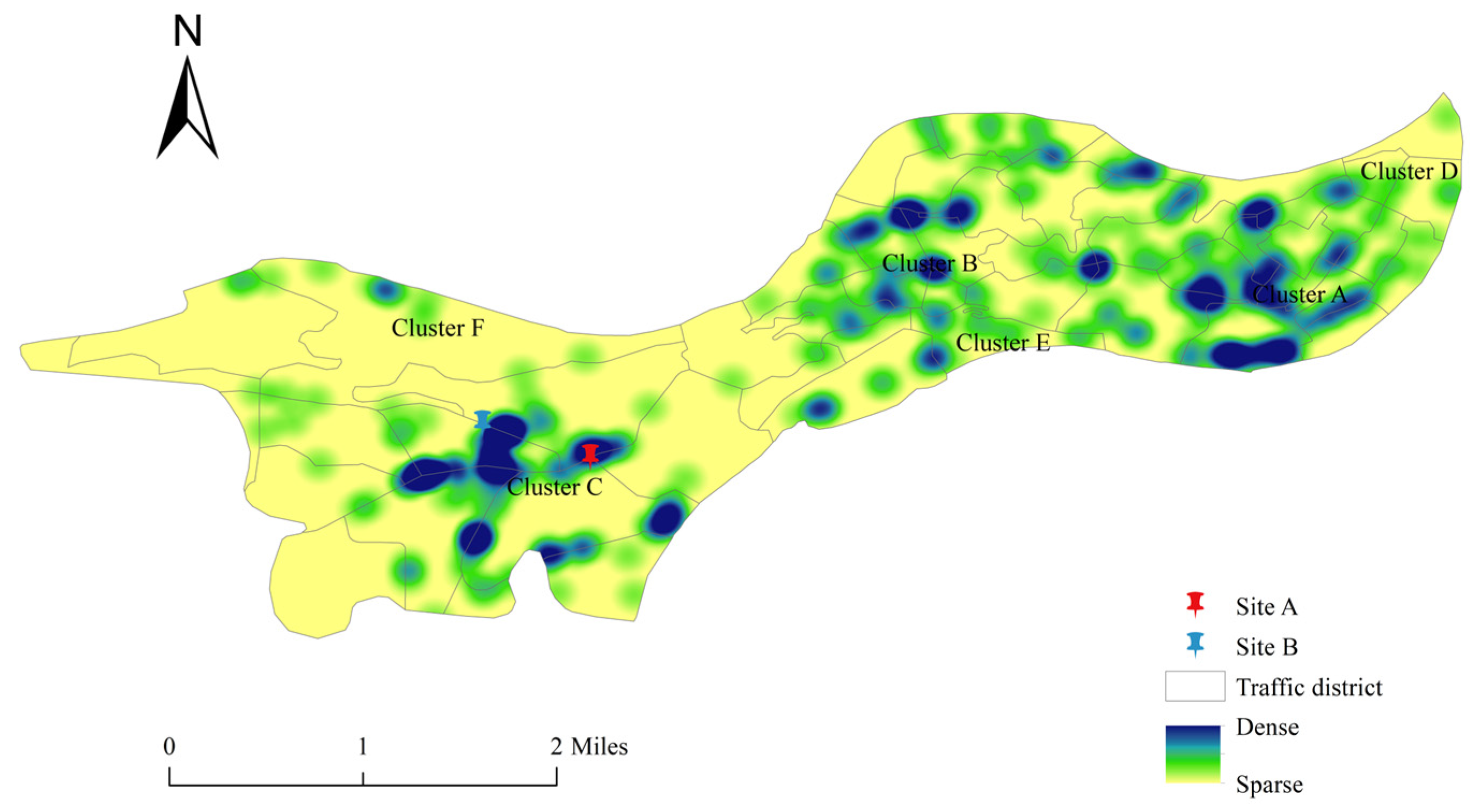

Methodologically, this study first eliminates collinearity among built environment factors through a correlation matrix screening process, then employs Standard Poisson Regression to identify statistically significant built environment variables, and subsequently utilizes Bayesian Poisson Regression to estimate both the direction (positive/negative) and magnitude of each built environment variable’s impact on pedestrian collision frequency. Additionally, kernel density estimation was applied to analyze the spatial clustering patterns of existing elderly traffic accidents, providing empirical support for localized traffic safety policy formulation.

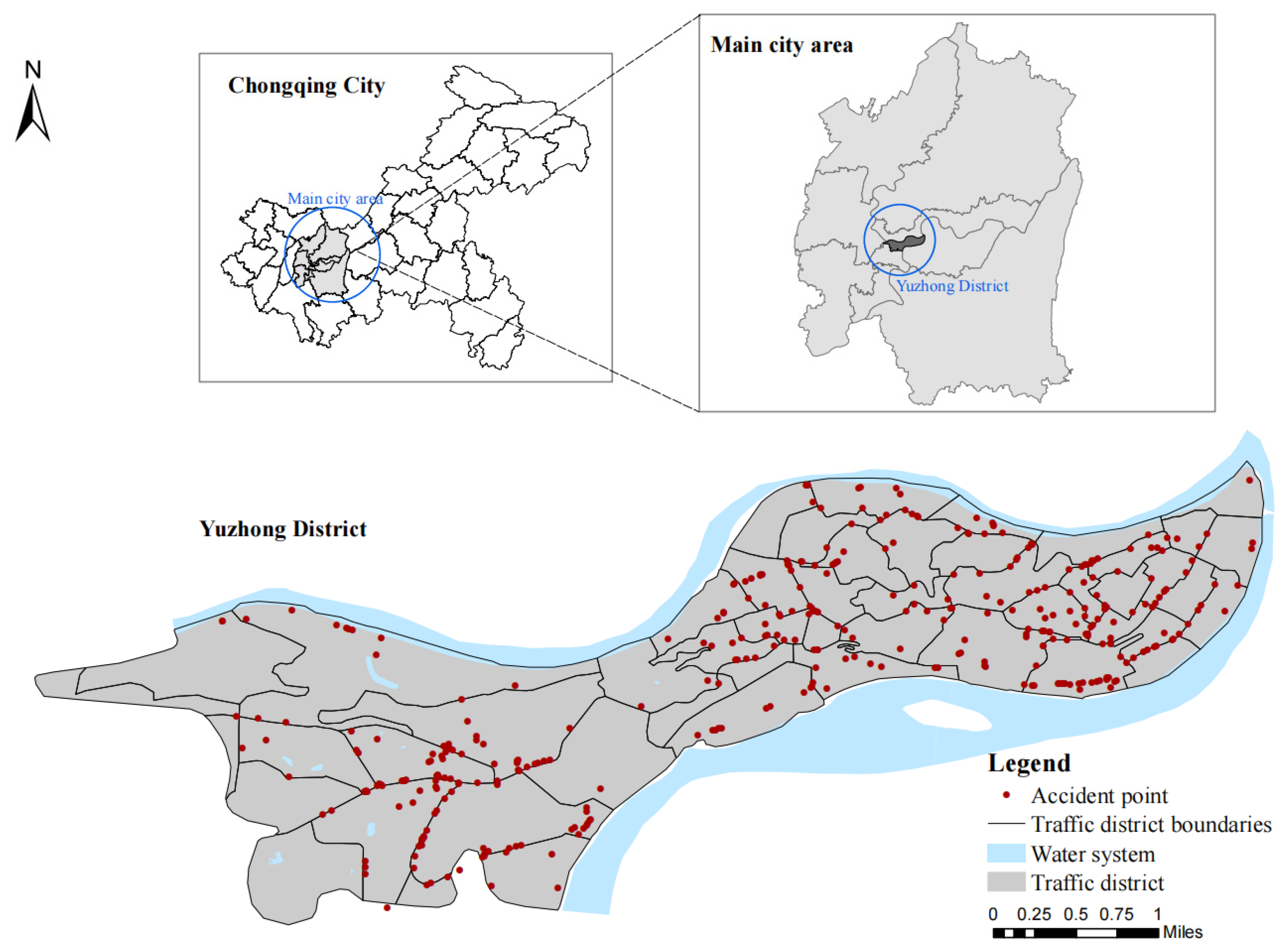

3.3. Data Sources

The traffic accident data of older pedestrians used in the study came from the traffic patrol police detachment of the study area, and we obtained a total of 2580 traffic accident data records in the study area from 2010 to 2021, including 854 walking accidents and 477 accidents involving older pedestrians. In the accident data, records involving two older pedestrians in the same accident were merged, and cases with unknown accident locations were excluded, resulting in a final dataset of 392 older-pedestrian crash records.

The demographic data were obtained from China Unicom’s mobile signaling data, with the dataset structured in 250 m × 250 m grid units for June 2021. This study calculated the monthly averages of both total population and older population for each grid within the study area. Employment population was defined as daytime-only population counts across all grids during the same one-month period. The mobile signaling data used in this research represent anonymized and expanded datasets of China Unicom users in the study area. While these processed data effectively preserve personal privacy by removing identifiable information, they maintain sufficient spatial resolution to reliably reflect population distribution patterns at the neighborhood scale. Subsequently, based on the vector maps of 50 traffic analysis zone (TAZ) boundaries, the constructed grids were spatially overlaid with TAZ boundaries using the spatial overlay analysis tool in ArcGIS 10.8 software, and the overlaid data were aggregated and calculated by TAZ affiliation, thereby yielding demographic data at the TAZ level.

The land use data was obtained by vectorizing remote sensing images using ArcGIS software. The remote sensing imagery consists of high-precision 2019 data for Yuzhong District, with a resolution of 2 m × 2 m, a spatial reference system of GCS_WGS_1984, and a datum of D_WGS_1984. The point of interest (POI) data was sourced from the Amap Open Platform (

https://lbs.amap.com/ (accessed on 14 July 2024)), covering various categories in Yuzhong District, Chongqing, including shopping, entertainment, healthcare, and more. The dataset includes geographic locations (latitude and longitude coordinates) and facility types.

The road network data was obtained from the OpenStreetMap (OSM) database (

https://www.openhistoricalmap.org/ (accessed on 17 July 2024)) and refined using ArcGIS software, incorporating both map references and field surveys. Additionally, data from roadside environmental facilities was collected through field survey.

3.4. Models

When the dependent variable follows a Poisson distribution, the Poisson Regression model is used; otherwise, a negative binomial model is used. This study conducted a distribution test on accident data of older pedestrians and found that it follows a Poisson distribution. For comparative purposes, the Standard Poisson Regression (SPR) model was also fitted as a baseline to evaluate the goodness-of-fit relative to the Bayesian approach.

3.4.1. Standard Poisson Regression (SPR)

Assuming that the number of older-pedestrian crashes, denoted as

, in the

i-th analysis zone follows a Poisson distribution with parameter

, the probability density function of the crash frequency is as follows:

where

i is TAZ ID,

Yi is the number of older-pedestrian crashes,

λi is the expected crash rate,

xi is the vector of independent variables,

Ei is the total older population, and

βj is the regression coefficient.

By taking the logarithm of both sides of Equation (2), we obtain the following:

where

is the exposure offset term, used to control the confounding effect of the older population base. The model ultimately predicts the crash rate per unit older population rather than the absolute count. All density-related variables (e.g., medical facility density, employment density) are built environment risk factors, not proxies for exposure. Only the total older population (target at-risk group) is selected as the exposure measure; the total population is not included since older pedestrians are the core research focus.

The maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) of parameter

β can then be obtained from the following log-likelihood function:

Substituting

into the equation, the log-likelihood function can be rewritten as follows:

3.4.2. Bayesian Poisson Regression (BPR)

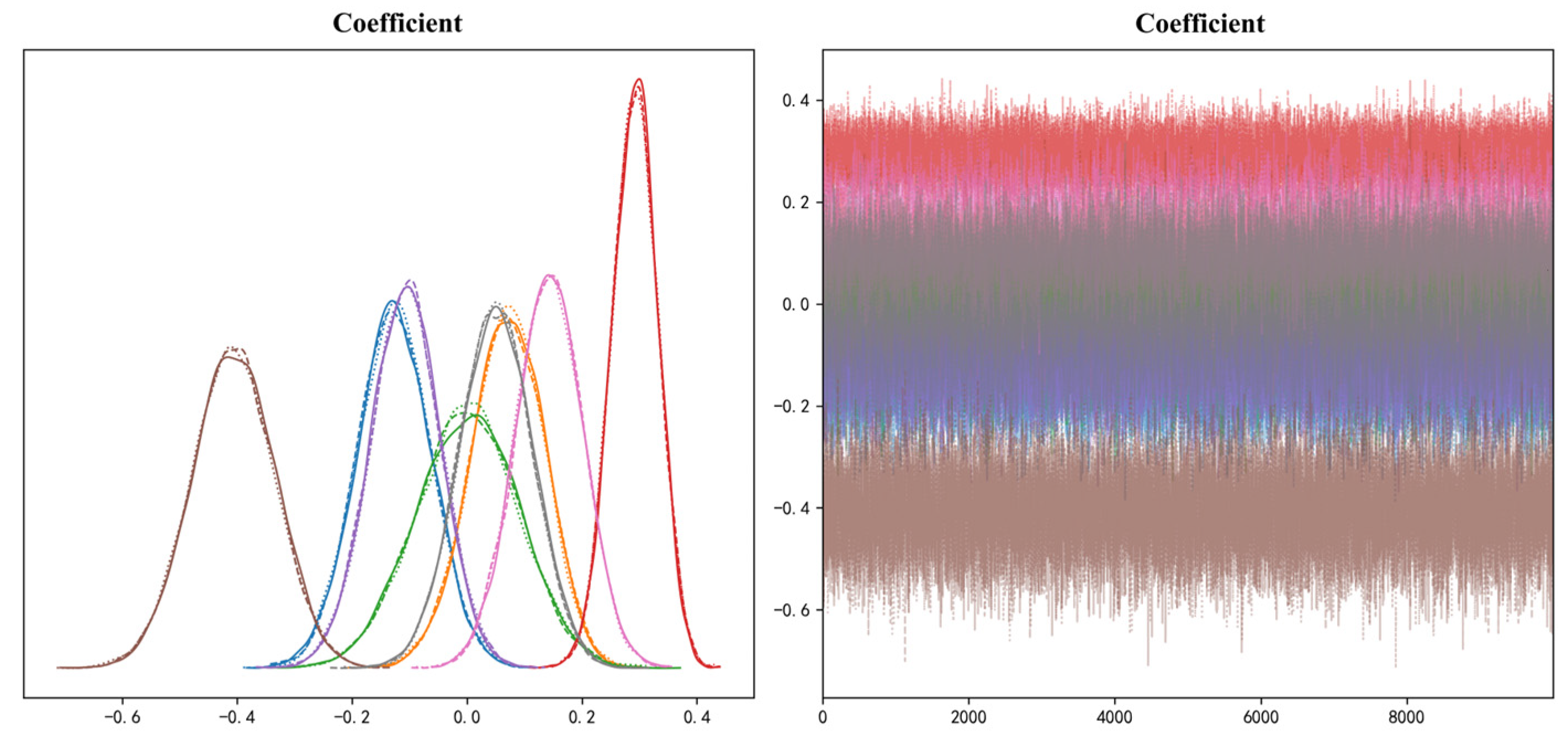

Bayesian Poisson Regression (BPR) adopts a framework where the likelihood function characterizes data patterns, the prior distribution incorporates parameter beliefs, and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling approximates the posterior distribution. It serves as a complement to the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) of Standard Poisson Regression (SPR), enabling the quantification of parameter uncertainty under small-sample conditions.

It is assumed that the regression coefficients follow weakly informative normal priors with different variances for intercept and slopes:

where

β0 is the intercept term,

βj are the coefficients of independent variables, 5

2 is the prior variance of the intercept, and 2

2 is the prior variance of slopes.

The likelihood function of the Bayesian model is consistent with that of SPR. Thus, the logarithmic likelihood function is as follows:

The joint distribution of the dataset

Y and parameter

β is the product of the likelihood function and the prior distribution. Further substituting the Standard Poisson Regression model into the above formula, we obtain the following:

The posterior distribution is as follows:

The posteriori expectation of parameter β is estimated as follows:

The core assumption of Poisson likelihood is conditional equidispersion (mean ≈ variance given covariates), and weakly informative priors cannot address overdispersion in the likelihood function. Diagnostic tests confirmed substantial overdispersion in our data, with the dispersion ratio for the Standard Poisson Regression (SPR) being 6.22 (

Table 1). While a negative binomial (NB) model can explicitly account for overdispersion, its dispersion parameter was estimated with high uncertainty (standard error > 0.5) due to our small sample size (n = 50), raising concerns about the stability of its estimates. However, priors can effectively stabilize coefficient estimates in small samples (n = 50) by avoiding extreme parameter values caused by overdispersion. The convergence of the BPR model was validated by R-hat < 1.01 and ESS > 20,000, and the predictive accuracy was confirmed by WAIC = 493.24.

The prior specification was strictly implemented in PyMC3, with the intercept term assigned a normal prior with a mean of 0 and a variance of 52, while all slope coefficients were assigned normal priors with a mean of 0 and a variance of 22. This prior structure avoids over-constraining the intercept term and ensures full consistency between the mathematical formulation and the computational implementation.

3.5. Variable Selection

For the unit of analysis, we use the spatial unit of traffic analysis zones (TAZs), which are widely employed in transportation analysis [

37]. On the basis of previous research and data availability, we divided the study area into 50 traffic districts. The average area of each traffic district is 0.37 km

2, and the biggest area is 1.71 km

2. This study used the frequency of older adult-involved traffic crashes per traffic zone as the dependent variable.

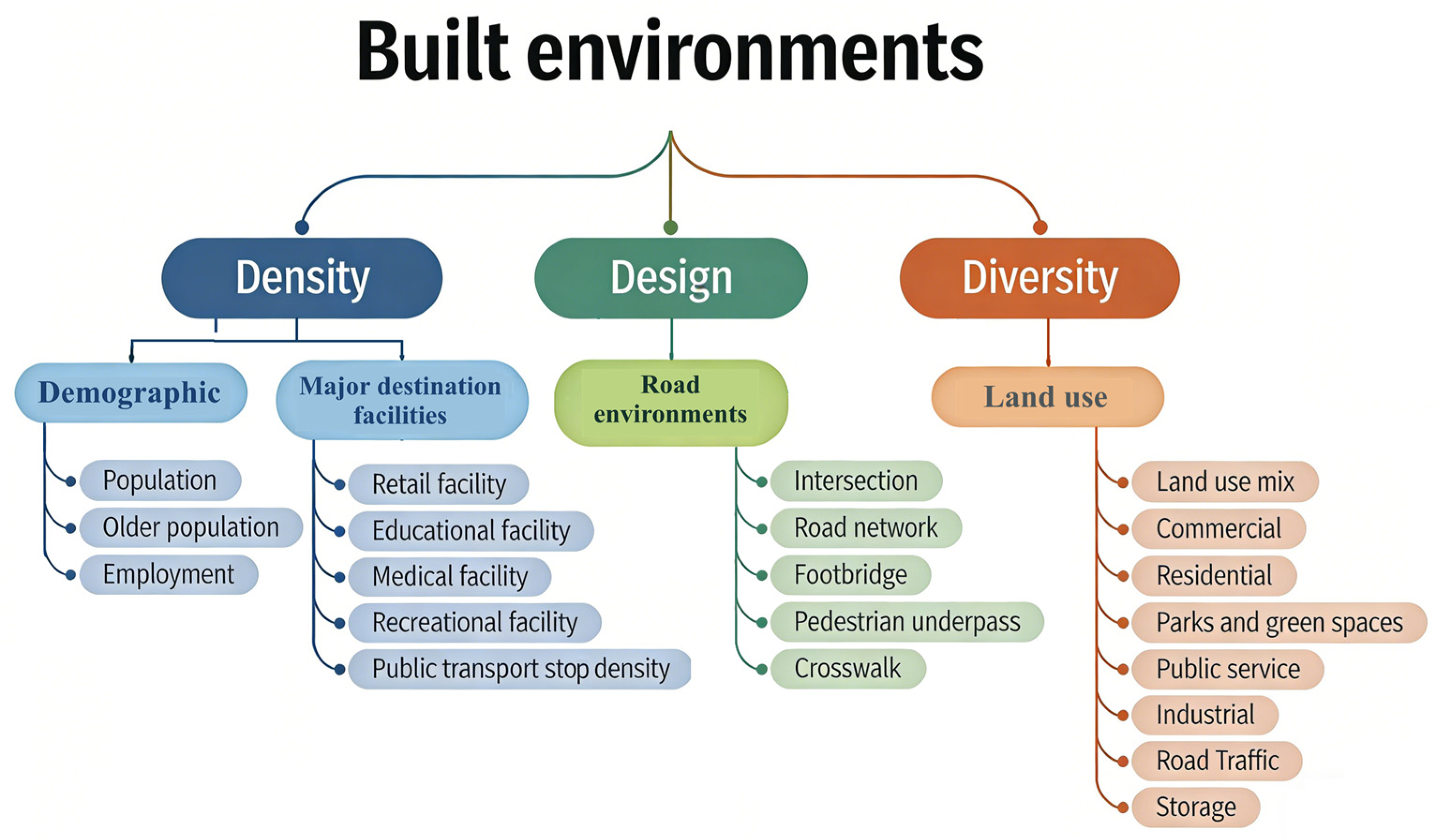

As shown in

Table 2, the independent variables were categorized into three types, specifically density, design, and diversity. Density-related variables measure the degree of spatial agglomeration of various elements, including demographic factors and major destination facilities; design-related variables reflect the characteristics of the road environment; diversity-related variables characterize the mix and composition of land use functions (

Figure 3). Regions with high population density, employment density, and activity facility density typically exhibit significantly elevated pedestrian flows and increased traffic volume, consequently heightening the likelihood of pedestrian–vehicle collisions [

38]. Areas with greater older population density demonstrate increased traffic exposure among older adults, correspondingly raising their accident risk. Furthermore, pedestrian collisions involving older individuals predominantly occur near key destination facilities that support their daily activities, including essential living amenities and public transportation hubs. Therefore, this study incorporates the following density indicators: retail facility density, educational facility density, medical facility density, recreational facility density, and public transport stop density.

Road environmental variables included intersection density, road network density, crosswalk density, and the density of underground passages and pedestrian overbridges. Higher intersection density is associated with a greater likelihood of pedestrian collisions [

39]. However, some studies also suggest that increased intersection density may actually reduce collision rates [

40], as drivers tend to concentrate their attention more when approaching road junctions, thereby decreasing the probability of accidents at intersections. Higher road network density tends to increase traffic flow, consequently compromising older pedestrians’ travel safety [

22]. At signal-controlled crosswalks, older pedestrians typically exhibit slower walking speeds than average [

41]. Pedestrian signal timing that fails to accommodate older pedestrians’ needs, combined with excessively wide roadways, prevents seniors from completing crossings within safe time intervals, thereby elevating their accident risks [

42]. In addition, in view of the undulating terrain, underpasses and pedestrian footbridges are common vehicular–pedestrian separation facilities in mountain cities, aiming to alleviate ground traffic pressure and reduce pedestrian–vehicle conflict points.

In terms of land use, we identified land use mix and the proportion of land use types. Land use mix (or mixed-use index) refers to a metric that quantifies the spatial integration of diverse functional land types within a given area. We calculated the land use mix for each traffic analysis zone (TAZ). To comprehensively characterize the land use patterns in our study area, we incorporated three specialized variables beyond conventional urban land categories (commercial, residential, park, and green space): (1) industrial land ratio, (2) road traffic land ratio, and (3) storage land ratio. This selection specifically addresses the unique spatial configuration of the study area.

The variable screening process consists of three sequential steps designed to ensure robustness and avoid multicollinearity. First, we perform Pure Poisson LASSO variable selection. The ElasticNetCV 1.7.2 tool (with l1_ratio = 1 for pure LASSO) is utilized to automatically select variables with non-zero coefficients. A 3-fold cross-validation was adopted to determine the optimal regularization parameter (α), given the small sample size (n = 50). Second, VIF-based multicollinearity diagnosis is conducted. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of the selected variables is calculated with a threshold set at 10. Variables with values exceeding this threshold are excluded. Third, variable number adjustment is carried out. If an excessive number of variables were eliminated in the preceding steps, additional variables with the highest correlation with crash counts are supplemented to ensure sufficient model degrees of freedom. If relatively few variables were eliminated earlier, no elimination is performed in this step.