An Analysis of Applicability for an E-Scooter to Ride on Sidewalk Based on a VR Simulator Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. E-Scooter Crashes Analysis

2.2. Experiments with a VR Simulator

2.2.1. Apparatus

2.2.2. Experimental VR Scenario Design

- Scenario 1: 4 m width, 20 people/min

- Scenario 2: 4 m width, 40 people/min

- Scenario 3: 2 m width, 10 people/min

- Scenario 4: 2 m width, 20 people/min

2.2.3. Participants

2.2.4. Experiment Procedure

2.2.5. Analysis Method

3. Results

3.1. Results for Detailed Analysis of Traffic Crash Data

3.2. Results for Investigation of E-Scooter Rider Behavior

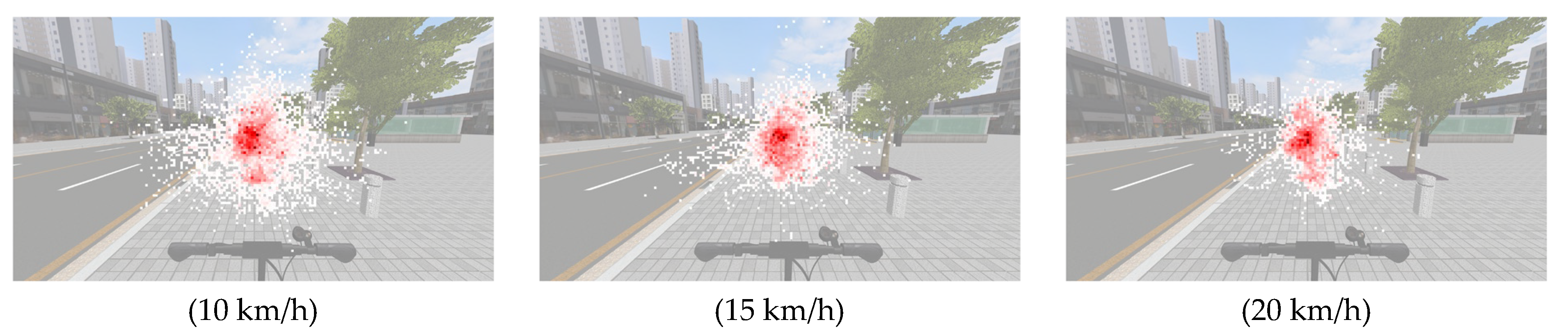

3.2.1. Gaze Behavior Analysis

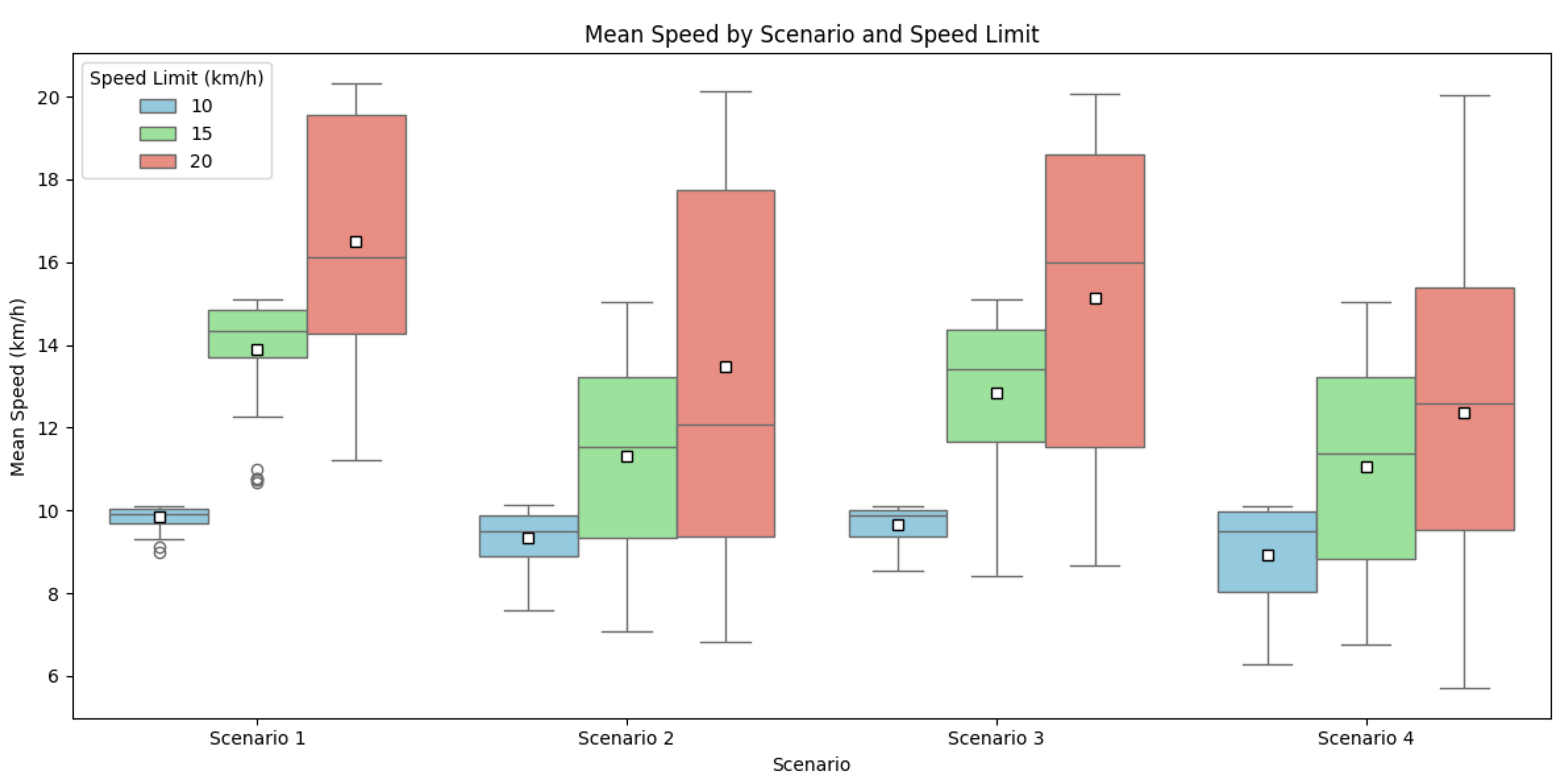

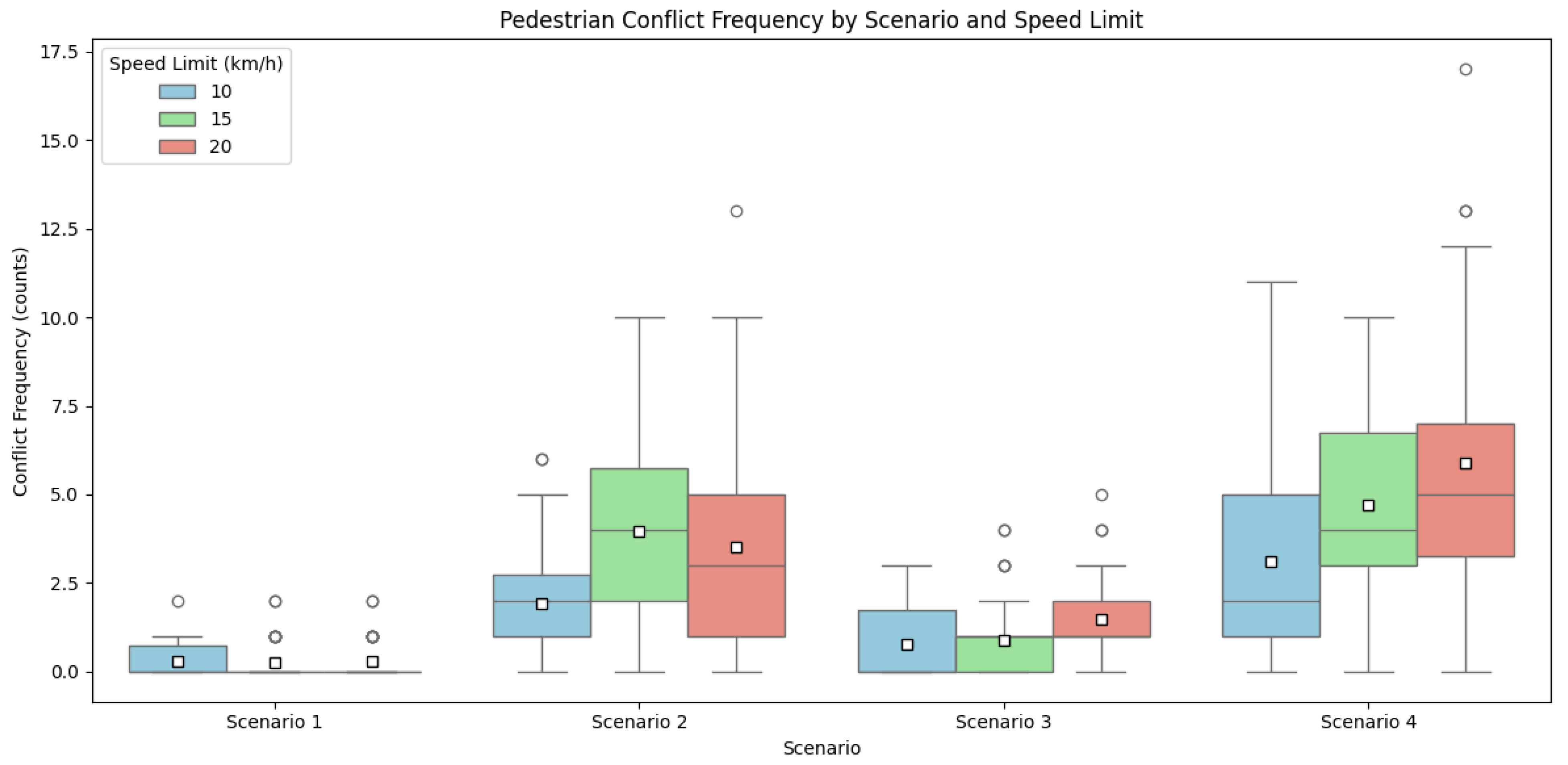

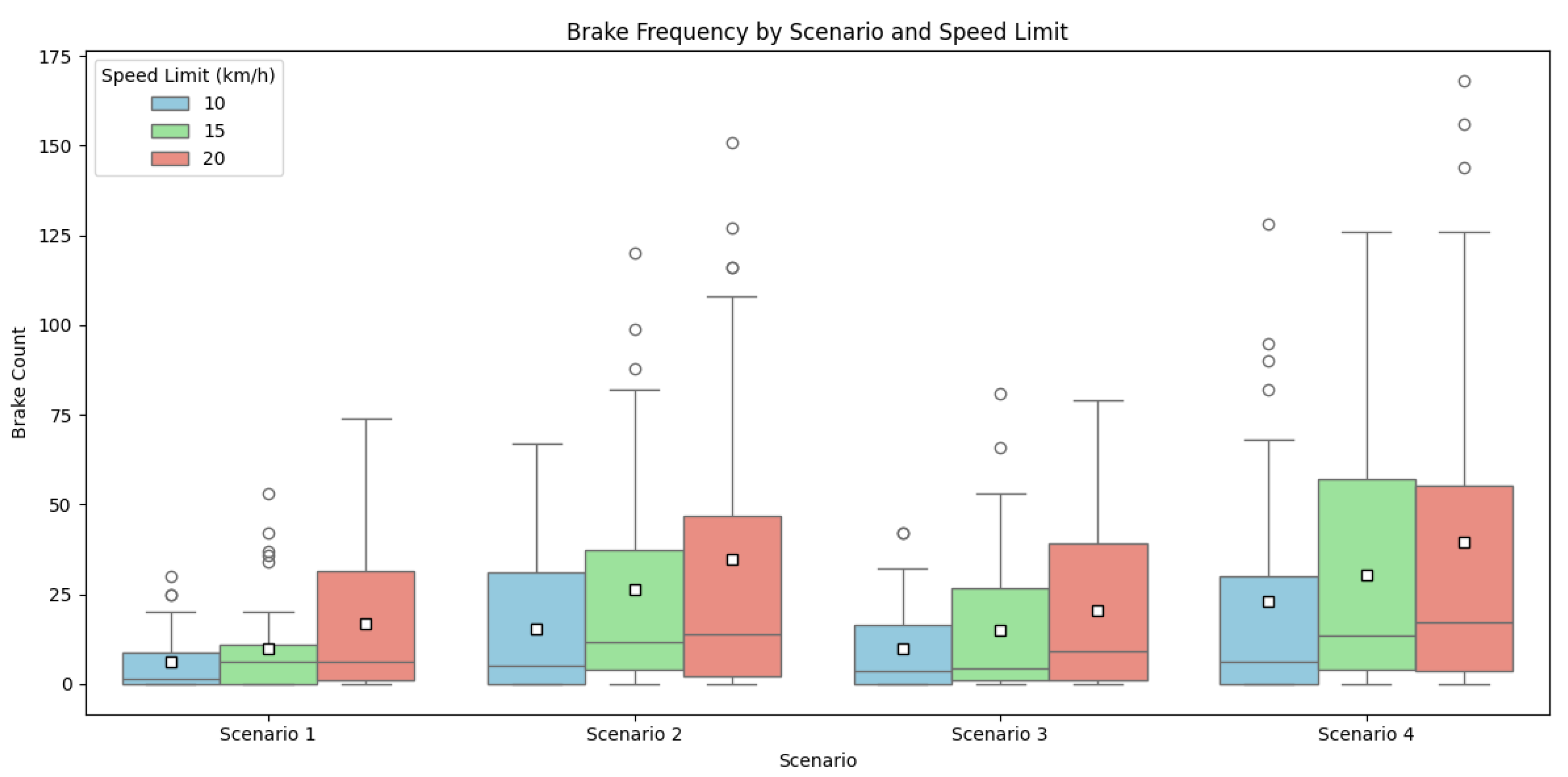

3.2.2. Riding Behaviors Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haworth, N.; Schramm, A.; Twisk, D. Changes in Shared and Private E-scooter Use in Brisbane, Australia and Their Safety Implications. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 163, 106451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, Z.; de Bortoli, A.; Gioldasis, C.; Seidowsky, R. Who Is Using E-scooters and How? Evidence from Paris. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 92, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distefano, N.; Leonardi, S.; Kieć, M.; D’aGostino, C. Comparison of E-scooter and Bike Users’ Behavior in Mixed Traffic. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2024, 2679, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Hess, P.M. Who Are the Potential Users of Shared E-scooters? An Examination of Socio-Demographic, Attitudinal and Environmental Factors. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehranfar, V.; Jones, C. Exploring Implications and Current Practices in E-scooter Safety: A Systematic Review. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 107, 321–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, S.; Brown, B. E-scooters on the Ground: Lessons for Redesigning Urban Micro-Mobility. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemzadeh, K. Assessing E-scooter Rider Safety Perceptions in Shared Spaces: Evidence from a Video Experiment in Sweden. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 211, 107874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chakraborty, R.; Mimi, M.S. Unraveling Crash Causation: A Deep Dive into Non-Motorists on Personal Conveyance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, 15–18 June 2024; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Useche, S.A.; O’HErn, S.; Gonzalez-Marin, A.; Gene-Morales, J.; Alonso, F.; Stephens, A.N. Unsafety on Two Wheels, or Social Prejudice? Proxying Behavioral Reports on Bicycle and E-scooter Riding Safety—A Mixed-Methods Study. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 89, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Q.; Xie, K.; Yang, D. Safety of Micro-Mobility: Analysis of E-scooter Crashes by Mining News Reports. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 143, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Lee, S.C.; Yoon, S.H. Exploring E-scooter Riders’ Risky Behaviour: Survey, Observation, and Interview Study. Ergonomics 2024, 68, 1371–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Road Traffic Authority. A Study on the Safety Evaluation of Bicycle Road Use by Personal Mobility Devices; Korea Road Traffic Authority: Wonju, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. Guidelines for the Installation and Management of Personal Mobility in Seoul; Seoul Metropolitan Government: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Useche, S.A.; Gonzalez-Marin, A.; Faus, M.; Alonso, F. Environmentally Friendly, but Behaviorally Complex? A Systematic Review of E-scooter Riders’ Psychosocial Risk Features. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioldasis, C.; Christoforou, Z.; Seidowsky, R. Risk-Taking Behaviors of E-scooter Users: A Survey in Paris. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 163, 106427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, D.J.; Hamilton, K. Predicting Undergraduates’ Willingness to Engage in Dangerous E-scooter Use Behaviors. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 103, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Krauss, D.; Zimmermann, J.; Dunning, A. Behavior of Electric Scooter Operators in Naturalistic Environments. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, F.W.; Hoffknecht, M.; Englert, F.; Edwards, T.; Useche, S.A.; Rötting, M. Safety-Related Behaviors and Law Adherence of Shared E-Scooter Riders in Germany. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Online, 24–29 July 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, E.G.; Harmon, K.J.; Sanders, R.L.; Shah, N.R.; Bryson, M.; Brown, C.T.; Cherry, C.R. Shared E-scooter Rider Safety Behaviour and Injury Outcomes: A Review of Studies in the United States. Transp. Rev. 2023, 43, 1263–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, H.; Mayhue, A.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ma, Y. E-scooter Safety: The Riding Risk Analysis Based on Mobile Sensing Data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 151, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Road Traffic Act (Japan), Article 17-2. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/2962/en (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Transport Operations (Road Use Management—Road Rules) Regulation 2009 (Queensland, Australia). Available online: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/sl-2009-0194 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Šucha, M.; Drimlová, E.; Rečka, K.; Haworth, N.; Karlsen, K.; Fyhri, A.; Wallgren, P.; Silverans, P.; Slootmans, F. E-scooter Riders and Pedestrians: Attitudes and Interactions in Five Countries. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Yamazoe, H. Preliminary Comparative Analysis of E-scooter and Pedestrian Speed Perception in a VR Environment. In Proceedings of the APMAR’24: The 16th Asia-PacificWorkshop on Mixed and Augmented Reality, Kyoto, Japan, 29–30 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goedicke, D.; Haraldsson, H.; Klein, N.; Zhou, L.; Parush, A.; Ju, W. ReRun: Enabling Multi-Perspective Analysis of Driving Interaction in VR. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2023 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–16 March 2023; pp. 889–890. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Rules on Standards for Road Structure and Facilities; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Road & Transportation Association. Korean Highway Capacity Manual; Korea Road & Transportation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. Rules on Standards for Structure and Facilities of Bicycle Utilization Facilities; Article 4; Ministry of the Interior and Safety; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Administration and Security. Enforcement Rule of the Road Traffic Act; Ordinance No. 554, Article 2–3; Effective 20 March 2025; Ministry of Public Administration and Security: Sejong, Republic of Korea.

- Lee, J.M. Incheon City Reduces Shared E-scooter Speed to 20 km/h and Mandates Age Verification for Under 16. Maeil Ilbo, 5 February 2024.

- Kim, S.; Lee, G.; Choo, S. Study on Shared E-scooter Usage Characteristics and Influencing Factors. J. Korean ITS Soc. 2021, 20, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. Analysis of Factors Influencing the Route Choice of E-scooter Users: Focusing on the Discrepancy between Actual Usage Paths and Shortest Paths. J. Korean Soc. Transp. 2025, 43, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N. 4 out of 10 Shared E-scooter Users are in their 30s and 40s. E-Today, 18 April 2021.

- SK Telecom. Analysis of Shared E-scooter Usage in Seoul; SK Telecom Geovision Puzzle: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pazzini, M.; Cameli, L.; Lantieri, C.; Vignali, V.; Dondi, G.; Jonsson, T. New Micromobility Means of Transport: An Analysis of E-scooter Users’ Behaviour in Trondheim. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Liu, Y. Pedestrians’ Safety Using Projected Time-to-Collision to Electric Scooters. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirdavani, A.; Bajestani, M.S.; Bunjong, S.; Delbare, L. The Impact of Perceptual Road Markings on Driving Behavior in Horizontal Curves: A Driving Simulator Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. Assessment and Importance Analysis of Driving Environment for Shared Personal Mobility Safety. Ph.D. Dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Dong, L.-L.; Xu, W.-H.; Zhang, L.-D.; Leon, A.S. Influence of Vehicle Speed on the Characteristics of Driver’s Eye Movement at a Highway Tunnel Entrance during Day and Night Conditions: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 656. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Kim, E.; Ji, M. Analysis of Severity Factors in Personal Mobility (PM) Traffic Accidents. J. Korean Soc. Transp. 2020, 38, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A.; Vinayaga-Sureshkanth, N.; Jadliwala, M.; Wijewickrama, R.; Griffin, G. Impact of E-scooters on Pedestrian Safety: A Field Study Using Pedestrian Crowd-Sensing. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops, Pisa, Italy, 21–25 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, N.J.; Gadiraju, R. Factors Affecting Speed Variance and Its Influence on Accidents. Transp. Res. Rec. 1989, 1213, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lehsing, C.; Ruch, F.; Kölsch, F.M.; Dyszak, G.N.; Haag, C.; Feldstein, I.T.; Savage, S.W.; Bowers, A.R. Effects of Simulated Mild Vision Loss on Gaze, Driving and Interaction Behaviors in Pedestrian Crossing Situations. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 125, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lim, J.; Ju, S.; Lee, S. A Study on the Compensation of the Difference of Driving Behavior between the Driving Vehicle and Driving Simulator. Int. J. Highw. Eng. 2015, 17, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Crash Factors | Specific Factors | Number of E-Scooter Crashes (%) | Number of All Vehicle Traffic Crashes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Careless or Illegal Driving | Signal Violation | 14 (8.92) | 6475 (14.47) | |

| Centerline Violation | Wrong-way Driving | 10 (6.37) | 1339 (2.99) | |

| Improper Overtaking and Turning | 3 (1.91) | |||

| Subtotal | 13 (8.28) | |||

| Driving Under the Influence (DUI) | 18 (11.46) | - | ||

| Violation of Traffic Regulations | Improper Intersection Proceeding | 9 (5.73) | 2823 (6.31) | |

| Failure to Stop at Crosswalk | 12 (7.64) | 80 (0.18) | ||

| Subtotal | 21 (13.38) | 2903 (6.49) | ||

| Failure to Fulfill Safe Driving Duty | Inattention | 4 (2.55) | 25,291 (56.53) | |

| Distractions Due to Using a Smart Device | 1 (0.64) | |||

| Failure to Keep Lookout | 49 (31.21) | |||

| Loss of Vehicle Control | 15 (9.55) | |||

| Subtotal | 69 (43.95) | |||

| Failure to Yield to Pedestrian | Failure to Keep Lookout | 17 (10.83) | 1659 (3.71) | |

| Loss of Vehicle Control | 1 (0.64) | |||

| Subtotal | 18 (11.46) | |||

| Failure to Maintain Safe Distance | 1 (0.64) | 4738 (10.59) | ||

| Subtotal | 154 (98.09) | 42,405 (94.78) | ||

| Road Surface and Mechanical Defect | 3 (1.91) | 3 (0.01) | ||

| Others | - | 2333 (5.21) | ||

| Subtotal | 3 (1.91) | 2336 (5.22) | ||

| Total | 157 (100.00) | 44,741 (100.00) | ||

| Descriptive Statistics of Riders’ Gaze Distance from Centerline by Speed Limit (Unit: cm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed Limit | Mean | S.D. | |

| 10 km/h | 16.10 | 5.84 | |

| 15 km/h | 13.88 | 5.63 | |

| 20 km/h | 13.07 | 5.88 | |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA by Speed Limit Conditions | |||

| F-test (p-value) | 11.51 (<0.001 **) | ||

| Post hoc Paired t-tests (p-value) | |||

| 10 km/h vs. 15 km/h | 3.26 (0.002 **) | ||

| 10 km/h vs. 20 km/h | 4.59 (<0.001 **) | ||

| 15 km/h vs. 20 km/h | 1.31 (0.198) | ||

| Descriptive Statistics of E-Scooter Riding Speed by Experimental Conditions (Unit: km/h) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed Limit | Scenario #1 | Scenario #2 | Scenario #3 | Scenario #4 | ||||

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| 10 km/h | 9.84 | 0.28 | 9.34 | 0.66 | 9.65 | 0.46 | 8.93 | 1.19 |

| 15 km/h | 13.99 | 1.31 | 11.54 | 2.20 | 13.04 | 1.77 | 11.34 | 2.38 |

| 20 km/h | 16.79 | 2.99 | 13.74 | 4.62 | 15.61 | 3.57 | 12.73 | 3.84 |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA by Speed Limit Conditions | ||||||||

| F-test (p-value) | 130.43 (<0.001 **) | 20.69 (<0.001 **) | 63.28 (<0.001 **) | 19.28 (<0.001 **) | ||||

| Post hoc Paired t-tests (p-value) | ||||||||

| 10 km/h vs. 15 km/h | −21.41 (<0.001 **) | −6.92 (<0.001 **) | −12.90 (<0.001 **) | −8.51 (<0.001 **) | ||||

| 10 km/h vs. 20 km/h | −14.74 (<0.001 **) | −6.22 (<0.001 **) | −10.99 (0.001 **) | −7.64 (<0.001 **) | ||||

| 15 km/h vs. 20 km/h | −5.88 (<0.001 **) | −4.13 (<0.001 **) | −5.13 (<0.001 **) | −3.51 (<0.001 **) | ||||

| Descriptive Statistics of Pedestrian Conflict Frequency by Experimental Conditions (Unit: Count) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed Limit | Scenario #1 | Scenario #2 | Scenario #3 | Scenario #4 | ||||

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| 10 km/h | 0.29 | 0.52 | 1.79 | 1.68 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 2.82 | 3.08 |

| 15 km/h | 0.24 | 0.54 | 3.90 | 2.63 | 0.85 | 1.13 | 4.93 | 2.81 |

| 20 km/h | 0.39 | 0.67 | 3.61 | 3.13 | 1.46 | 1.32 | 5.83 | 3.54 |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA by Speed Limit Conditions | ||||||||

| F-test (p-value) | 0.03 (0.972) | 8.31 (0.001 **) | 4.44 (0.015 *) | 12.36 (<0.001 **) | ||||

| Post hoc Paired t-tests (p-value) | ||||||||

| 10 km/h vs. 15 km/h | - | −3.89 (<0.001 **) | −0.61 (0.548) | −2.67 (0.011 *) | ||||

| 10 km/h vs. 20 km/h | - | −3.38 (0.002 **) | −2.64 (0.012 *) | −5.88 (<0.001 **) | ||||

| 15 km/h vs. 20 km/h | - | 0.73 (0.468) | −2.14 (0.039 *) | −1.98 (0.055) | ||||

| Descriptive Statistics of Brake Frequency by Experimental Conditions (Unit: Count) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed Limit | Scenario #1 | Scenario #2 | Scenario #3 | Scenario #4 | ||||

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| 10 km/h | 6.32 | 8.51 | 15.37 | 19.95 | 9.71 | 12.63 | 22.87 | 33.55 |

| 15 km/h | 9.68 | 13.40 | 26.39 | 32.53 | 15.05 | 20.65 | 30.32 | 34.68 |

| 20 km/h | 16.68 | 21.99 | 34.79 | 42.75 | 20.61 | 24.36 | 39.45 | 49.08 |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA by Speed Limit Conditions | ||||||||

| F-test (p-value) | 7.43 (0.001 **) | 8.76 (<0.001 **) | 6.80 (0.002 **) | 5.84 (0.004 **) | ||||

| Post hoc Paired t-tests (p-value) | ||||||||

| 10 km/h vs. 15 km/h | −1.79 (0.081 *) | −3.23 (0.003 **) | −2.33 (0.025 *) | −2.01 (0.052) | ||||

| 10 km/h vs. 20 km/h | −3.24 (0.002 **) | −3.43 (0.002 **) | −3.64 (0.001 **) | −2.85 (0.007 **) | ||||

| 15 km/h vs. 20 km/h | −2.35 (0.024 *) | 1.83 (0.076) | −1.60 (0.118) | −1.90 (0.066) | ||||

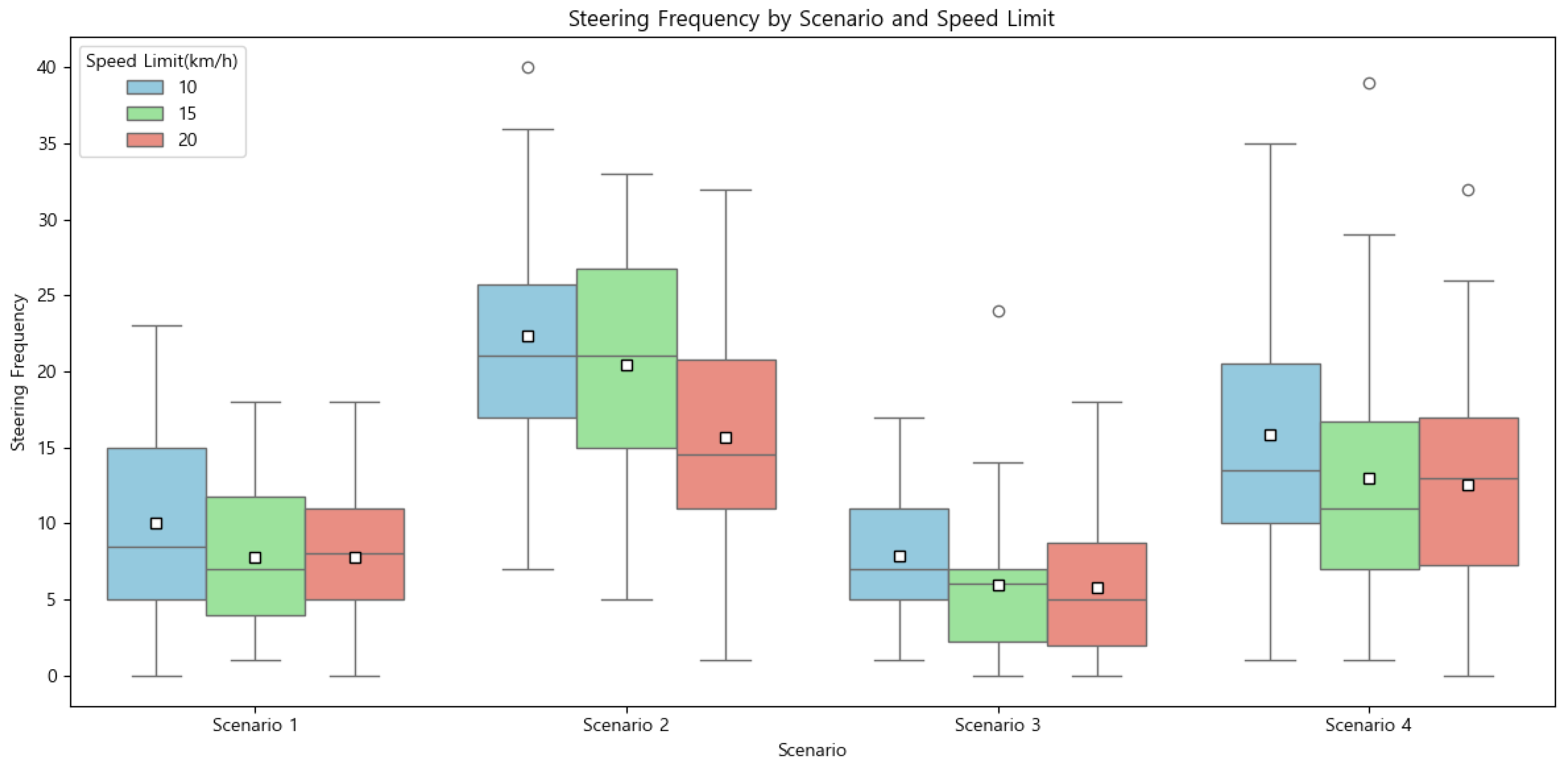

| Descriptive Statistics of Steering Frequency by Experimental Conditions (Unit: Count) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed Limit | Scenario #1 | Scenario #2 | Scenario #3 | Scenario #4 | ||||

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| 10 km/h | 10.03 | 6.16 | 22.37 | 7.36 | 7.87 | 4.28 | 15.82 | 8.97 |

| 15 km/h | 8.27 | 5.35 | 21.02 | 7.91 | 6.32 | 5.35 | 13.59 | 8.70 |

| 20 km/h | 8.63 | 5.11 | 16.00 | 7.54 | 6.49 | 5.42 | 13.37 | 8.59 |

| Repeated Measures ANOVA by Speed Limit Conditions | ||||||||

| F-test (p-value) | 2.72 (0.072) | 10.59 (<0.001 **) | 3.44 (0.037 *) | 2.85 (0.064) | ||||

| Post hoc Paired t-tests (p-value) | ||||||||

| 10 km/h vs. 15 km/h | - | 1.20 (0.238) | 2.16 (0.037 *) | - | ||||

| 10 km/h vs. 20 km/h | - | 4.25 (<0.001 **) | 2.40 (0.021 *) | - | ||||

| 15 km/h vs. 20 km/h | - | 3.59 (0.001 **) | 0.15 (0.884) | - | ||||

| Brake Only | Steering Only | Brake and Steering | None | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 km/h | Scenario #1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Scenario #2 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 11 | 66 | |

| Scenario #3 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 29 | |

| Scenario #4 | 38 | 21 | 40 | 19 | 118 | |

| 15 km/h | Scenario #1 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 9 |

| Scenario #2 | 30 | 51 | 55 | 24 | 160 | |

| Scenario #3 | 11 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 35 | |

| Scenario #4 | 53 | 27 | 80 | 42 | 202 | |

| 20 km/h | Scenario #1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 16 |

| Scenario #2 | 28 | 22 | 80 | 18 | 148 | |

| Scenario #3 | 15 | 14 | 22 | 9 | 60 | |

| Scenario #4 | 73 | 42 | 75 | 49 | 239 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | β | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedestrian Density (Low, High) | 4.087 | 0.208 | 1.875 | <0.001 ** |

| Sidewalk Width (2 m, 4 m) | −0.505 | 0.174 | −0.562 | 0.004 ** |

| Pre-Conflict Speed (km/h) | 0.145 | 0.017 | 0.490 | <0.001 ** |

| R2 | 0.722 | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.720 | |||

| F-statistics (p-value) | 412.43 (<0.001 **) | |||

| AIC | 2157.15 | |||

| N | 480 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Hwang, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. An Analysis of Applicability for an E-Scooter to Ride on Sidewalk Based on a VR Simulator Study. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010218

Kim J, Lee D, Hwang S, Lee J, Kim S. An Analysis of Applicability for an E-Scooter to Ride on Sidewalk Based on a VR Simulator Study. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010218

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihyun, Dongmin Lee, Sooncheon Hwang, Juehyun Lee, and Seungmin Kim. 2026. "An Analysis of Applicability for an E-Scooter to Ride on Sidewalk Based on a VR Simulator Study" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010218

APA StyleKim, J., Lee, D., Hwang, S., Lee, J., & Kim, S. (2026). An Analysis of Applicability for an E-Scooter to Ride on Sidewalk Based on a VR Simulator Study. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010218