An Enhanced Hybrid TLBO–ANN Framework for Accurate Photovoltaic Power Prediction Under Varying Environmental Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Artificial Neural Networks

2.2. Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization

2.2.1. Teacher Phase

2.2.2. Student Phase

2.3. Proposed TLBO-ANN Hybrid Model

2.4. Model Configuration and Hyperparameters

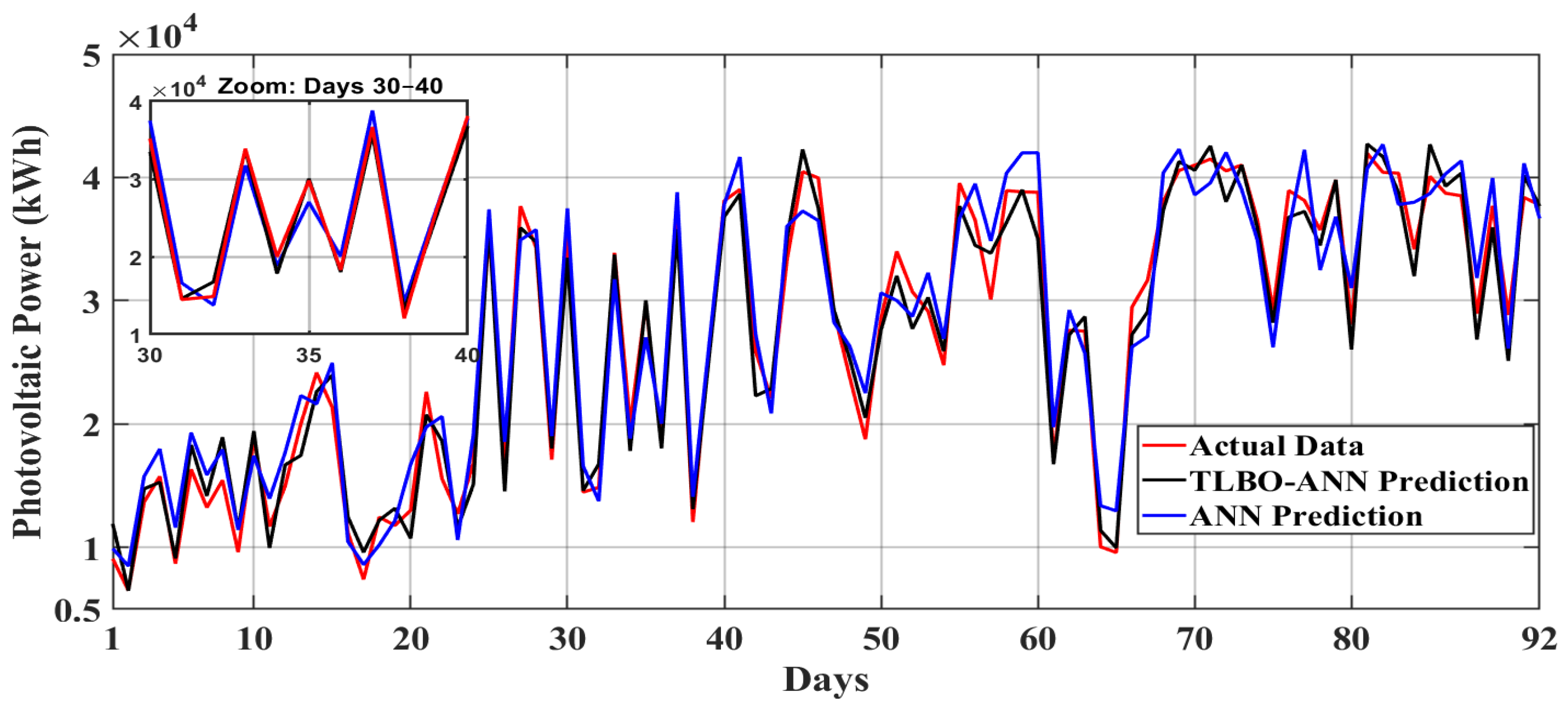

3. Prediction Results for Photovoltaic Power with TLBO-ANN and ANN

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mansouri, N.Y.; Crookes, R.J.; Korakianitis, T. A projection of energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions in the electricity sector for Saudi Arabia: The case for carbon capture and storage and solar photovoltaics. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayigh, A. Renewable energy—The way forward. Appl. Energy 1999, 64, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Lin, H.; Li, H.; Sun, Q. Power generation efficiency and prospects of floating photovoltaic systems. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamdari, P.; Nematollahi, O.; Alemrajabi, A.A. Solar energy potentials in Iran: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 21, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T.C. Enerji ve Tabii Kaynaklar Bakanlığı. 2023. Available online: https://enerji.gov.tr/bilgi-merkezi-enerji-elektrik (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Eltawil, M.A.; Zhao, Z. Grid-connected photovoltaic power systems: Technical and potential problems—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Lee, W.-J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P. Forecasting power output of photovoltaic systems based on weather classification and support vector machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2012, 48, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascikaraoglu, A.; Sanandaji, B.M.; Chicco, G.; Cocina, V.; Spertino, F.; Erdinc, O.; Paterakis, N.G.; Catalao, J.P. Compressive spatio-temporal forecasting of meteorological quantities and photovoltaic power. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2016, 7, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzalka, A.; Alam, N.; Duminil, E.; Coors, V.; Eicker, U. Large scale integration of photovoltaics in cities. Appl. Energy 2012, 93, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyte, A.; Thong, V.; Belmans, R.; Nijs, J. Voltage fluctuations on distribution level introduced by photovoltaic systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2006, 21, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, D.; Shepero, M.; Svensson, A.; Widén, J.; Munkhammar, J. Probabilistic forecasting of electricity consumption, photovoltaic power generation and net demand of an individual building using Gaussian Processes. Appl. Energy 2018, 213, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilbudak, M.; Colak, M.; Bayindir, R. What are the current status and future prospects in solar irradiance and solar power forecasting? Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. 2018, 8, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsinga, B.; van Sark, W.G. Short-term peer-to-peer solar forecasting in a network of photovoltaic systems. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1464–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleissl, J. Solar Energy Forecasting and Resource Assessment; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Qiao, Y.-H.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. Mid-to-long term wind and photovoltaic power generation prediction based on copula function and long short term memory network. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Peng, Z.; Lai, Y.; Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Wu, L. Short-term power prediction for photovoltaic power plants using a hybrid improved Kmeans-GRA-Elman model based on multivariate meteorological factors and historical power datasets. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izgi, E.; Öztopal, A.; Yerli, B.; Kaymak, M.K.; Şahin, A.D. Short–mid-term solar power prediction by using artificial neural networks. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wang, D.; Singh, V.P.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zou, Y.; He, R. A hybrid model-based framework for estimating ecological risk. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X. Comparative study of power forecasting methods for PV stations. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Power System Technology, Hangzhou, China, 24–28 October 2010; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, T.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, F.; Du, P. A hybrid forecasting method for solar output power based on variational mode decomposition, deep belief networks and auto-regressive moving average. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, W. Photovoltaic power forecasting based on EEMD and a variable-weight combination forecasting model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-P.; Pai, P.-F. Solar power output forecasting using evolutionary seasonal decomposition least-square support vector regression. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nespoli, A.; Ogliari, E.; Leva, S.; Pavan, A.M.; Mellit, A.; Lughi, V.; Dolara, A. Day-ahead photovoltaic forecasting: A comparison of the most effective techniques. Energies 2019, 12, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lian, W.; Lu, L.; Dai, S.; Hu, Y. An improved forecasting method for photovoltaic power based on adaptive BP neural network with a scrolling time window. Energies 2017, 10, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Wang, P. Resilience-oriented asynchronous decentralized restoration considering building and E-bus co-response in electricity-transportation networks. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 11701–11713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, Z.; Tian, X.; Su, J.; Chang, X.; Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, H. A two-stage distributionally robust low-carbon operation method for antarctic unmanned observation station integrating virtual energy storage and hydrogen waste heat recovery. Appl. Energy 2025, 400, 126578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.Q.; Nadarajah, M.; Ekanayake, C. On recent advances in PV output power forecast. Sol. Energy 2016, 136, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Savsani, V.J.; Vakharia, D.P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput.-Aided Des. 2011, 43, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaker, J.; Höller, R. Hybrid model for intra-day probabilistic PV power forecast. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDeventer, W.; Jamei, E.; Thirunavukkarasu, G.S.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Soon, T.K.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S.; Stojcevski, A. Short-term PV power forecasting using hybrid GASVM technique. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Yang, D. Probabilistic photovoltaic power forecasting using a calibrated ensemble of model chains. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Han, Z. A new method for short-term photovoltaic power generation forecast based on ensemble model. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 095008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoean, C.; Zivkovic, M.; Bozovic, A.; Bacanin, N.; Strulak-Wójcikiewicz, R.; Antonijevic, M.; Stoean, R. Metaheuristic-based hyperparameter tuning for recurrent deep learning: Application to the prediction of solar energy generation. Axioms 2023, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedinia, O.; Amjady, N.; Ghadimi, N. Solar energy forecasting based on hybrid neural network and improved metaheuristic algorithm. Comput. Intell. 2018, 34, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, E.; Yeşilbudak, M.; Taşdemir, O. Enhanced PV power prediction considering PM10 parameter by hybrid JAYA-ANN Model. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2024, 52, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, E.; Thirunavukkarasu, G.S.; Soon, T.K.; Mortimer, M.; Horan, B.; Stojcevski, A.; Mekhilef, S. Short-term forecasting of the output power of a building-integrated photovoltaic system using a metaheuristic approach. Energies 2018, 11, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J. Benefits of physical and machine learning hybridization for photovoltaic power forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, M.K.; Majumder, I.; Nayak, N. Solar photovoltaic power forecasting using optimized modified extreme learning machine technique. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2018, 21, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-F.; Li, L.-L.; Tseng, M.-L.; Lim, M.K. Prediction short-term photovoltaic power using improved chicken swarm optimizer-extreme learning machine model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Li, C.; Gao, R.; Huang, Y.; You, H.; Gu, T.; Qin, F. Photovoltaic power forecasting based on a support vector machine with improved ant colony optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallal, M.A.; Chabaa, S.; Zeroual, A. A novel deep neural network based on randomly occurring distributed delayed PSO algorithm for monitoring the energy produced by four dual-axis solar trackers. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Y.; Wang, B.; Zheng, T.; Liao, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Song, X. Time series prediction for output of multi-region solar power plants. Appl. Energy 2020, 257, 114001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; AlHakeem, D.; Mandal, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Wu, Y.-K.; Senjyu, T.; Paudyal, S.; Tseng, T.-L. Performance evaluation of probabilistic methods based on bootstrap and quantile regression to quantify PV power point forecast uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 31, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseye, A.T.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, D. Short-term photovoltaic solar power forecasting using a hybrid Wavelet-PSO-SVM model based on SCADA and Meteorological information. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ran, R.; Zhou, Y. A short-term photovoltaic power prediction model based on an FOS-ELM algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, N.; Gong, L.; Jiang, M. Prediction of photovoltaic power output based on similar day analysis, genetic algorithm and extreme learning machine. Energy 2020, 204, 117894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Armaghani, D.J.; Hatzigeorgiou, G.D.; Karayannis, C.G.; Pilakoutas, K. Predicting the shear strength of reinforced concrete beams using Artificial Neural Networks. Comput. Concr. Int. J. 2019, 24, 469–488. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.; Han, Y.; So, S.S. Overview of artificial neural networks. In Artificial Neural Networks: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, M.; Moselhi, O. Automated detection and location of leaks in water mains using infrared photography. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2010, 24, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbarufatti, C.; Corbetta, M.; Manes, A.; Giglio, M. Sequential Monte-Carlo sampling based on a committee of artificial neural networks for posterior state estimation and residual lifetime prediction. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 83, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; McClelland, J.L.; PDP Research Group. Parallel Distributed Processing, Volume 1: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition: Foundations; The MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kankal, M.; Uzlu, E. Neural network approach with teaching–learning-based optimization for modeling and forecasting long-term electric energy demand in Turkey. Neural Comput. Appl. 2017, 28, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Chen, Y. Hybrid teaching–learning-based optimization and neural network algorithm for engineering design optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 187, 104836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.V.; Savsani, V.J.; Balic, J. Teaching–learning-based optimization algorithm for unconstrained and constrained real-parameter optimization problems. Eng. Optim. 2012, 44, 1447–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshani, H.; Rahati, A. Snap-drift cuckoo search: A novel cuckoo search optimization algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 52, 771–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Methods | Based on mathematical modeling of PV panels and meteorological data. | No training data required; good for stable conditions. | Sensitive to rapid weather changes; requires precise system parameters. | [19] |

| Statistical Methods | Uses historical time series data to predict future values. | Simple computation; effective for linear patterns. | Struggles with non-linear and chaotic weather data. | [20,21] |

| Conventional ANN | Data driven AI model mimicking neural networks. | Strong non-linear mapping capability. | Prone to getting stuck in local minima; slow convergence. | [27] |

| Hybrid metaheuristic algorithm | Optimization algorithms coupled with ANN. | Improved accuracy over a standalone ANN. | Requires tuning of complex parameters (mutation, inertia); computationally expensive. | [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] |

| Proposed TLBO-ANN | Parameterless optimization coupled with ANN. | Fast convergence; robust against local minima; no parameter tuning. | Dependent on the quality of training data. | [This Study] |

| Parameter | Value/Description |

|---|---|

| ANN Architecture | |

| Input Layer Neurons | 4 (PV Power, Solar Radiation, Temperature, Wind Speed) |

| Hidden Layers | 1 |

| Hidden Layer Neurons | 5 |

| Output Layer Neurons | 1 (PV Power Output) |

| Activation Function (Hidden) | Sigmoid |

| Activation Function (Output) | Linear (Purelin) |

| TLBO Settings | |

| Population Size | 50 |

| Maximum Iterations | 100 |

| Stopping Criterion | Maximum iterations reached or Min. Error |

| Models | (%) | (kWh) | (kWh) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN (test) | 7.38 | 2732.1 | 2606.5 | 0.96 |

| TLBO-ANN (test) | 4.43 | 1773 | 1533 | 0.98 |

| ANN (training) | 11.55 | 2494.3 | 2299.7 | 0.94 |

| TLBO-ANN (training) | 7.26 | 1733.8 | 1440.5 | 0.97 |

| ANN (all) | 10.73 | 2542.6 | 2359.8 | 0.95 |

| TLBO-ANN (all) | 6.71 | 1741.5 | 1458.6 | 0.97 |

| Models | (%) | (kWh) | (kWh) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLBO-ANN (test) | 4.43 | 1773 | 1533 | 0.98 |

| PSO-ANN (test) | 5.49 | 2035.3 | 1935 | 0.97 |

| GA-ANN (test) | 6.42 | 2404.3 | 2289.6 | 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ermiş, S.; Taşdemir, O. An Enhanced Hybrid TLBO–ANN Framework for Accurate Photovoltaic Power Prediction Under Varying Environmental Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010157

Ermiş S, Taşdemir O. An Enhanced Hybrid TLBO–ANN Framework for Accurate Photovoltaic Power Prediction Under Varying Environmental Conditions. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleErmiş, Salih, and Oğuz Taşdemir. 2026. "An Enhanced Hybrid TLBO–ANN Framework for Accurate Photovoltaic Power Prediction Under Varying Environmental Conditions" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010157

APA StyleErmiş, S., & Taşdemir, O. (2026). An Enhanced Hybrid TLBO–ANN Framework for Accurate Photovoltaic Power Prediction Under Varying Environmental Conditions. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010157