1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of global marine resource development, the growth of underwater tourism, and the increasing depth of scientific exploration, safety risks associated with underwater operations have risen significantly [

1]. The corresponding increase in underwater accidents has created an urgent demand for efficient and reliable unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) to support rescue missions [

2]. However, many existing underwater rescue systems still show critical limitations. These include low emergency-response capability, insufficient usability, and weak functional integration. Such issues become more serious in complex and fast-changing marine environments, ultimately reducing the effectiveness of rescue operations [

3].

As integrated mechatronic systems integrating perception, navigation, and manipulation technologies, underwater rescue robots play a decisive role in the success of rescue operations [

4]. An ideal rescue robot should combine reliable task performance with balanced integration of functional diversity, ergonomic design, human–machine interaction, and technical performance [

5]. Existing research has achieved meaningful progress at the component and subsystem level. However, most studies still focus on isolated technical improvements. They lack a systematic approach for capturing mission-critical user needs and translating them into coherent design requirements [

6]. Importantly, this is not due to an absence of design methods, but rather due to the lack of a structured, context-specific workflow tailored to underwater rescue scenarios. This gap manifests as a persistent knowing–doing gap: designers know the methods but lack a proven procedure to apply them effectively under the extreme constraints of rescue operations.

Several fundamental development challenges contribute to this gap. First, although user-centered design (UCD) principles are well established in many design domains, their application to underwater rescue robotics is often superficial. Few studies explicitly model the high cognitive load, rapidly shifting visibility, and time-critical decision-making required in underwater rescue missions. As a result, existing UCD tools cannot fully capture the complex human–machine-environment interactions that characterize this domain [

7]. Second, knowledge remains siloed across robotics engineering, human factors, and rescue operation expertise. For example, while the human factors model proposed by [

8] provides valuable insights, it has not been operationally integrated with robotic design parameters for rescue-specific validation. Thus, the challenge is not merely applying known methods, but orchestrating a cross-disciplinary dialog that is codified into a repeatable design process. Third, evaluation methods are predominantly confined to controlled laboratory settings, which fail to stress-test designs under the psychological pressure and environmental unpredictability of real rescue scenarios.

To address these challenges, this study posits that the core problem is methodological translation rather than methodological invention. The affinity diagram (KJ method) and Kano model are indeed proven tools for organizing and prioritizing user needs. However, their standard application assumes relatively stable user contexts and allows for a slow, linear design cycle. Digital Twin (DT) technology is also a widely used prototyping tool. However, it is typically applied after design for performance optimization or operator training. It is rarely employed as a front-end mechanism for validating early-stage requirements.

The novel integration proposed here addresses a specific, unmet need: closing the feedback loop between upfront requirement prioritization and experiential validation in a high-fidelity, risk-free simulation. This is critical for underwater rescue because: (1) field testing of incomplete designs is prohibitively dangerous and expensive, and (2) operators cannot reliably articulate needs for scenarios they can rarely experience before deployment. Given these constraints, a simulation-driven approach is not merely beneficial but essential. Thus, the research question driving this work is: How can a closed-loop, simulation-driven workflow transform established KJ-Kano requirement analysis into dynamically validated design prototypes for underwater rescue robots.

Building upon these insights, this study proposes a DT-enhanced KJ-Kano framework for the conceptual design of underwater rescue robots. The key differentiation is not the components, but their sequence, tight coupling, and domain-driven adaptation. The framework first employs the KJ method to cluster user requirements derived from rescue scenario analysis. It then uses the Kano model to prioritize them based on their impact on operator effectiveness under stress. Crucially, these prioritized requirements are immediately instantiated within a mission-aware DT environment. This allows for the collection of behavioral and performance feedback from users within simulated rescue scenarios, creating a data-driven refinement loop that directly informs requirement adjustment and design iteration.

The main contributions of this research are threefold:

- (1)

Developing a prescriptive, domain-specific design workflow that formalizes the integration of KJ, Kano, and DT into a closed-loop conceptual design process for underwater rescue robots.

- (2)

Providing an empirically tested process that demonstrates how general UCD methods can be systematically contextualized for high-risk, rapidly changing underwater rescue scenarios.

- (3)

Demonstrating a validation paradigm shift moving from static requirement verification to a dynamic co-evolution of requirements and designs via interactive simulation, offering a generalizable model for mitigating requirement-design mismatches in other complex human–machine systems.

The novelty of this article lies in the formulation, application, and validation of a domain-adapted methodological chain for a critical application area. While KJ, Kano, and DT are individually well known, their orchestration into a seamless, iterative workflow where DT actively validates and refines the output of KJ-Kano analysis before physical prototyping is novel for underwater rescue robotics. This work moves beyond suggesting method integration to providing a tested protocol that answers how to achieve it effectively under domain constraints, thereby bridging the gap between general design knowledge and context-specific, reliable implementation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related studies on underwater rescue robot development, user-centered design in robotics and rescue systems, applications of the KJ method and Kano model, and recent advances in DT-based design.

Section 3 details the proposed KJ-Kano-DT framework in terms of key stages and iteration mechanism.

Section 4 presents key research results of each stage. Methodological innovation, practical implications, generalizability of the proposed framework, limitations and future work are discussed in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Research Progress in Underwater Rescue Equipment

UUVs have become essential for complex underwater missions, offering advantages in safety and operational flexibility over manned systems. Research has advanced rapidly globally, with significant contributions from diverse research communities. This section synthesizes progress by technological domain, highlighting convergent approaches and divergent emphases across studies.

In perception and navigation, enhancing situational awareness in turbid, feature-sparse environments is a universal challenge. A comparative analysis reveals two dominant, complementary strands of research. One focused on multi-sensor fusion to mitigate the limitations of any single modality. For instance, Zhang et al. [

9] systematically reviewed integrated and collaborative navigation as promising directions for AUVs. Similarly, Heshmat et al. [

10] argued that Visual–Inertial–Acoustic fusion is critical for complex missions. The other strand leverages AI and deep learning. Qin et al. [

11] combined geometric visual SLAM with deep learning for robustness. Correspondingly, Elmezain et al. [

12] identified Transformer-based models as effective for mitigating turbidity effects. A critical gap noted by both communities is the scarcity of validation in realistic, cluttered rescue scenarios, with most evaluations conducted in open water or controlled tanks.

In propulsion and maneuverability, the need for agility in currents and constrained spaces drives innovation in propulsion. Here, research shows clearer thematic specialization. International work often explores bio-inspired or novel mechanisms, such as the underwater snake-like robots noted for their potential, albeit with reliability challenges in soft materials [

13]. In contrast, several prominent Chinese studies (e.g., Zhao et al. [

14]) often integrate multi-thruster systems within more conventional robotic platforms to achieve stability. This difference may reflect a focus on incremental reliability versus exploratory mobility, a trade-off that directly impacts rescue robot design in different environments.

In system integration and rescue applications, the ultimate test of technology is in integrated systems performing rescue tasks. Comparative analysis shows a spectrum from task-specific devices to modular platforms. Studies like Zhang et al. [

15] cable-threading device demonstrate high efficiency for a focused task. On the other end, Bonfitto et al. [

16] and Jiko et al. [

17] emphasize modularity and adaptability of underwater robots for broader mission sets. Krieg et al. [

18] specifically integrated sensing and recovery for victim retrieval. A unifying limitation across these applied studies is the insufficient linkage between technical performance metrics and the cognitive load or operational workflow of the human operator, a point that segues into the need for UCD.

Overall, underwater rescue robots are evolving from single-purpose devices toward intelligent, adaptive, and networked systems. Despite these advancements, critical limitations persist from a design perspective. First, few studies deeply investigate the real needs of rescue personnel. Operators often face unpredictable underwater conditions requiring high functionality, reliability, and usability, yet man systems fail to fully address these user requirements, reducing real-world applications [

19]. Second, deficiencies in appearance design, color schemes, and user interface layout persist. Rough external forms and monotonous color palettes may diminish visual appeal and psychological comfort, while poorly structured control interfaces can impede rapid operation during emergencies, undermining overall rescue effectiveness [

20,

21]. These gaps collectively underscore a technology-centric paradigm that often overlooks the holistic integration of user needs, interdisciplinary knowledge, and human factors into the core design process. Notably, across both domestic and international research, technical advances are rarely evaluated against operator workload, situational stress, or decision-making constraints, indicating a persistent disconnect between engineering progress and mission-oriented usability.

2.2. UCD in Robotics and Rescue Systems

UCD places user needs, operational constraints, and experiential factors at the core of the design process, ensuring that usability, safety, and cognitive compatibility complement technical performance. Within underwater and rescue robotics, UCD has been shown to enhance operator efficiency, situational awareness, and decision-making accuracy. However, existing studies differ considerably in scope and methodological rigor. For example, survey-based analyses of novice ROV operators highlight environmental and human factors, such as lighting conditions, water turbidity, and outdoor operational stress, as primary determinants of perceptual clarity and cognitive load, thus emphasizing interface usability in early-stage design [

22]. In contrast, reviews of underwater human–robot and human–swarm interaction stress behavioral transparency, trust calibration, and motion legibility under extreme environmental uncertainty [

23], indicating that perceptual usability alone is insufficient for supporting high-stakes rescue collaboration.

Vision-based underwater experience studies further extend the UCD spectrum by demonstrating how enhanced visual encoding, multimodal sensory feedback, and immersive visualization can compensate for underwater perceptual limitations [

24]. Yet these approaches typically assume stable sensing conditions and therefore offer limited insight into rescue contexts where sensor degradation, occlusion, and real-time risk assessment are prevalent. Similarly, engineering-driven developments of underwater vehicles for survey, search, and rescue prioritize mechanical robustness, autonomy, and task coverage [

25], but often provide only minimal integration of systematic user modeling or interaction testing. Diver-support concepts such as the NADIA system attempt to bridge this gap by addressing emotional acceptance, safety signaling, and behavioral predictability [

26], but they remain scenario-specific and do not generalize into broader design methodologies.

Across these works, a consistent limitation emerges, UCD is frequently treated as an auxiliary rather than a formative design principle, most studies rely on post hoc evaluations, such as surveys or isolated usability tests, rather than embedding user needs into iterative design verification loop or system-level decision-making processes. This leads to systems that nominally address user needs but fail to adapt to real-world operational complexity [

27]. Moreover, a methodological gap persists between ergonomic evaluation and system-level performance metrics, especially when balancing technical precision with usability and emotional acceptance [

28]. Insufficient interdisciplinary collaboration among engineers, cognitive scientists, and end users further constrains the creation of context-aware and dynamically adaptive systems. These deficiencies highlight the pressing need for a more structured and scenario-aware way of applying existing UCD principles to systematically translate user-centered insights into operationally grounded requirements, ensuring that underwater rescue robots remain both technically capable and practically usable in extreme environments.

2.3. KJ Method and Kano Model in Design Research

The KJ method [

29], also known as the affinity diagram method, is a qualitative method widely used in industrial design and interaction design to organize dispersed and unstructured user feedback. By clustering qualitative data into coherent themes, it helps designers reveal latent user needs and map relationships among functional requirements, user expectations, and contextual constraints. Conversely, the Kano model [

30] provides a quantitative framework for evaluating user satisfaction by classifying product attributes into categories such as must-be, one-dimensional, attractive, indifferent and reverse. This classification enables designers to identify which features most strongly influence user satisfaction or dissatisfaction, thereby aiding in resource allocation and requirement prioritization.

Because of their complementary strengths, the integration of KJ and Kano has gained popularity in consumer product design and service research. In such contexts, the hybrid framework facilitates a transition from open-ended qualitative exploration (via KJ) to structured, prioritized requirement sets (via Kano), thereby linking user perceptions with design decisions in a systematic manner. However, a critical examination of existing literature reveals two important limitations that constrain the applicability of this hybrid approach in rescue robotics and other extreme, safety-critical domains:

- (1)

Lack of contextual adaptability. Most applications target stable, predictable environments or consumer scenarios. They do not account for extreme environmental constraints (e.g., poor visibility, high-pressure underwater conditions), high operator stress, real-time decision-making under uncertainty, or the need for rapid response. As a result, requirement sets derived in such contexts often lack validity when translated into designs for rescue robots operating in dynamic, hazardous conditions.

- (2)

Absence of validation mechanisms tied to operational performance. The traditional KJ-Kano combination typically produces a prioritized requirement list based on subjective satisfaction measures or survey responses. What is generally missing is a mechanism for testing whether fulfilling these prioritized requirements actually improves system usability, safety, or performance under realistic operational scenarios. Without such validation, the prioritization remains a conceptual artifact rather than a proven design guideline.

Recognizing these limitations, this study adopts a modified KJ-Kano approach tailored to underwater rescue robotics. Specifically, this study combines qualitative need elicitation (via KJ) from domain experts (e.g., divers, rescue operators, engineers) with Kano-based prioritization, while embedding the process within a simulation-driven validation framework. This ensures that the requirements not only reflect real user and environmental constraints, but are also tested for operational effectiveness before committing to physical design. By doing so, this research aims to bridge the gap between user-centered requirement analysis and performance-validated design decisions, a necessary step toward developing rescue systems that are both human-centric and mission-ready.

2.4. DT in Product Design and Human–Machine Systems

DT technology has emerged as a transformative paradigm, creating a dynamic virtual counterpart of a physical system for simulation, analysis, and control. Its application in product design and human–machine systems is particularly critical for safety-driven domains like rescue robotics. This subsection synthesizes the literature along two primary and often distinct research streams: iterative, human-centric design prototyping and proactive safety validation.

In iterative prototyping, DT enables cost-effective refinement of human–machine interaction (HMI) and ergonomics. Studies such as Gallala et al. [

31] and Mo et al. [

32] demonstrate DT’s utility in simulating collaborative interfaces and gesture-based interactions, effectively de-risking the development of intuitive HMI for Industry 5.0 contexts. Further extending human-centricity, Xu et al. [

33] applied DT for ergonomic modeling, while Niu et al. [

34] integrated crowd-sourcing mechanisms to engage broader stakeholders in co-creative design. These studies affirm DT’s strength in evaluating and optimizing a design’s form and interaction after its core functions are defined.

In parallel, a significant research branch focuses on proactive safety validation. This involves simulating fault conditions, operator errors, and extreme environments to verify system resilience before physical deployment. For example, Kousi et al. [

35] explored DT-driven adaptive assembly system for operational resilience, while Das et al. [

36] developed an edge-assisted DT framework specifically for safety-critical robotics, showcasing how virtual monitoring can prevent physical accidents. These works highlight DT’s role not just as a design tool, but as a verification and certification platform for testing system integrity and reliability under predefined hazardous conditions.

However, a critical gap remains. While DT excels in performance simulation and safety testing, and methods like KJ-Kano excel in front-end requirement prioritization, they operate in separate silos. Few studies have proposed a closed-loop framework where user requirements (prioritized via KJ-Kano) are directly implemented and stress-tested within a safety-aware DT environment, allowing requirements to be validated and refined based on operational safety and performance data. This disconnect is particularly acute for high-stakes domains like underwater rescue, where both user-centricity and operational safety are non-negotiable. Consequently, the research imperative shifts from merely identifying this disconnect to constructing and empirically validating a specific, closed-loop procedural solution that is capable of bridging it. Therefore, this study seeks to bridge this gap by integrating requirement prioritization with DT-based, safety-informed validation.

2.5. Synthesis, Comparative Analysis, and Identified Gap

The preceding analysis reveals a critical, yet often overlooked, distinction: the existence of design methods is not synonymous with the existence of a reliable design process. This synthesis directly informs the methodological architecture presented in

Section 3, where these identified gaps are operationalized into a step-wise, closed-loop design workflow. While methods like KJ, Kano, and DT are mature, and their potential combination is conceptually apparent, the literature demonstrates a persistent failure to translate this potential into a validated, domain-effective workflow for safety-critical systems like underwater rescue robots. The purpose of this Section is to provide the analytical foundation that transforms the proposed ‘combination’ from a mere idea into a necessary and substantiated research endeavor. Unlike prior works that merely juxtapose multiple methods, this study introduces a procedural integration mechanism, specifically, a closed-loop requirement–configuration–validation cycle, that enables cross-phase constraint propagation and iterative refinement, which has not been formalized in previous KJ-Kano or DT-based studies.

A systematic comparison, presented in

Table 1, analyzes related works across three critical, yet disconnected, dimensions of design: (1) system design methodologies, (2) front-end user requirement analysis and prioritization, and (3) back-end simulation and validation. This analysis reveals that state-of-the-art contributions excel within one dimension but lack the mechanisms to bridge them.

Table 1 clarifies that the research gap is not a lack of methods, but a lack of a prescriptive, translational protocol. Prior works like the integrated mechatronic design methodologies [

37,

38] provide valuable high-level frameworks but are agnostic to the specific mechanisms of user requirement validation. Conversely, applied KJ-Kano studies or DT validation projects are typically depth-focused within their phase. The contribution is not the combination itself, but the domain-specific orchestration that answers ‘how’ to make this combination work effectively for underwater rescue robots. In contrast to these approaches, the proposed framework does not stop at aligning methods conceptually; instead, it operationalizes their integration through an executable sequence in which prioritized user attributes directly drive DT-based prototype instantiation, and DT feedback recursively updates requirement priorities.

This orchestration defines and operationalizes a new set of interdependent variables that flow in a closed loop, which prior combinations have not formalized:

User-need variables: Kano category, satisfaction coefficient, and weighted priority of functional and interaction attributes.

Design configuration variables: interface layout, autonomy level, feedback modality, module grouping, each derived from user-need variables rather than designer assumptions.

DT-validation variables: practical functionality, interactivity, intelligent experience, appearance under simulation conditions.

This explicit interdependence among variables ensures phase-to-phase traceability, whereas existing methods keep these phases analytically separated, resulting in fragmented decision-making.

Therefore, the proposed framework is ‘integrated’ and ‘comprehensive’ in a specific, procedural sense: it provides a detailed, actionable sequence that forces a continuous, data-informed dialog between user-value prioritization (Dimension (2)) and safety-critical performance validation (Dimension (3)), within the concrete context of underwater rescue. It establishes a formal feedback mechanism where empirical data (design configuration variables) actively validates or refines the initial requirement priorities (user-need variables) via the configurable prototype (DT-validation variables). This transforms the conceptual design process from a linear, assumption-driven sequence into an iterative, evidence-driven cycle. This constitutes the paper’s core scientific contribution: a tested methodological artifact that bridges the persistent knowing–doing gap in the design of complex, safety-critical human–machine systems.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts a mixed-method, procedural design workflow to support the conceptual design of underwater rescue robots. It focuses on formalizing how established methods, i.e., qualitative clustering (KJ method), quantitative prioritization (Kano model), and DT-based validation, are operationally orchestrated into a coherent, evidence-driven design process. Unlike a conventional linear design pipeline, the proposed framework implements a stage-gated, closed-loop architecture in which design progression is explicitly conditioned on validation evidence.

3.1. Overview of the Procedural Framework

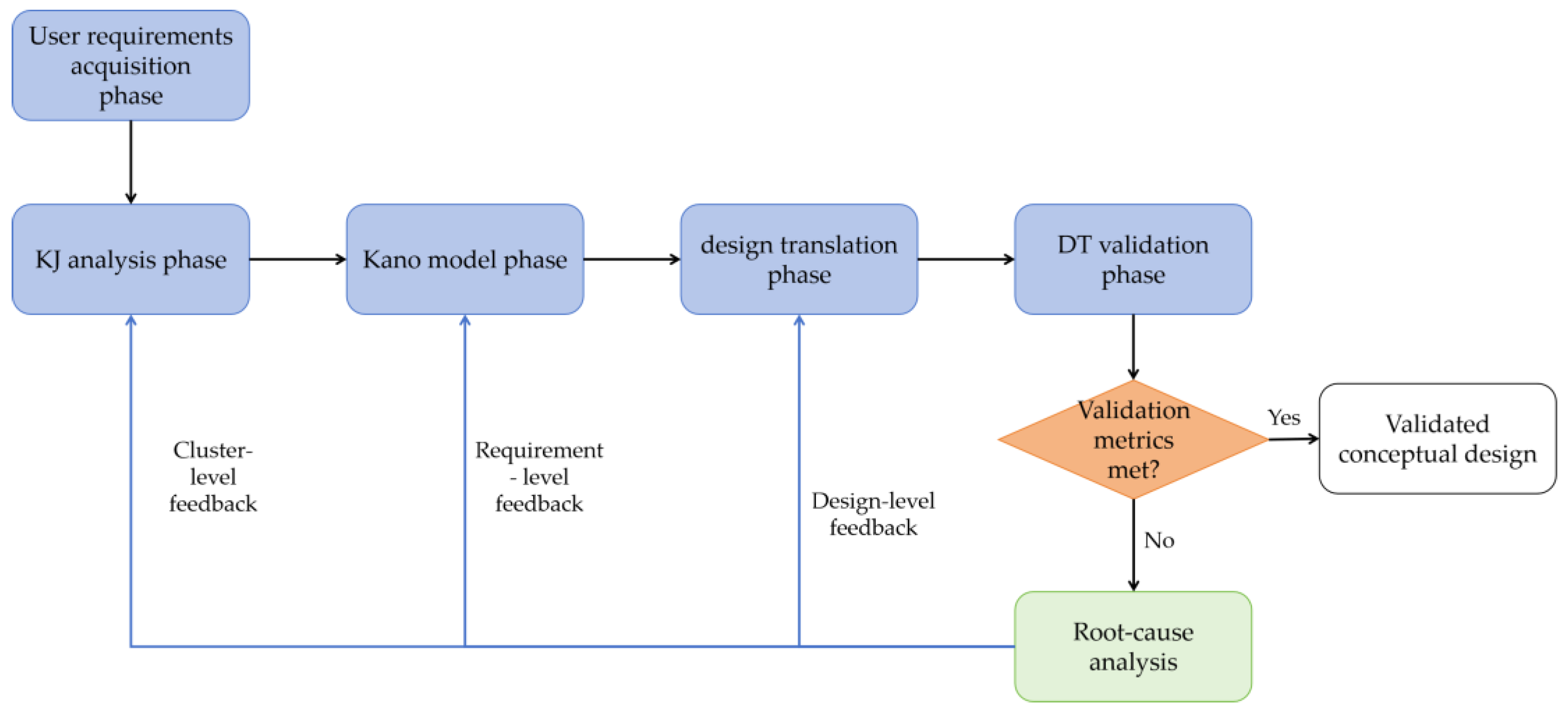

Figure 1 systematically illustrates the procedural architecture of the proposed KJ–Kano–DT framework, representing a complete, evidence-driven methodology that connects user needs to validated conceptual design. The framework comprises four key graphical elements: five core process stages (blue rectangles), three-level feedback mechanisms (blue arrows), and a decision node for validation-based iteration (orange diamond). Together, these elements establish full traceability from initial user input to design validation, while preventing uncontrolled or infinite iteration.

The five core stages constitute the methodological backbone of the framework:

- (1)

User requirements acquisition phase: Qualitative user needs are elicited through semi-structured interviews with domain experts, forming the starting point of the design procedural process.

- (2)

KJ analysis phase: Qualitative user needs are clustered using the KJ method. This stage transforms unstructured narratives into coherent requirement groups.

- (3)

Kano model phase: The clustered requirements are quantitatively evaluated using a Kano questionnaire. To ensure continuity between qualitative exploration and quantitative prioritization, the Kano questionnaire items were directly derived from the requirement clusters obtained through KJ analysis. Requirements are classified and ranked according to their impact on user satisfaction, generating prioritized input for design translation.

- (4)

Design translation phase: Prioritized requirements are translated into conceptual, modular design candidates. Importantly, this phase produces multiple candidate solutions for each requirement cluster, emphasizing functional intent rather than implementation detail.

- (5)

Digital Twin (DT) validation phase: Selected design candidates are instantiated in a DT environment and tested under representative rescue scenarios (e.g., low visibility, dynamic currents). Participants evaluate DT prototypes based on practical functionality, interactivity, intelligent experience, and appearance. This stage provides the final empirical input before design convergence.

Solid black arrows in

Figure 1 represent the primary data flow and output transfer between these stages, ensuring end-to-end traceability.

3.2. Evidence-Driven Feedback and Iteration Mechanism

The key contribution of the framework lies in its structured feedback logic, represented by the blue arrows in

Figure 1. Validation results from the DT phase are assessed at an explicit decision node (orange diamond). When predefined thresholds are not satisfied, the framework triggers targeted feedback, rather than indiscriminate repetition.

Three distinct feedback levels are defined based on root-cause analysis:

- (1)

Design-level feedback: If deficiencies are linked to configuration or interaction design, alternative design candidates are re-evaluated without changing requirement priorities.

- (2)

Requirement-level feedback: If performance issues indicate misaligned prioritization, Kano classifications and weights are recalibrated.

- (3)

Cluster-level feedback: If inconsistencies stem from fundamental requirement definitions, the framework re-enters the KJ clustering phase to re-structure user needs.

This multi-level feedback strategy differentiates the proposed framework from linear or loosely coupled method combinations, enabling precise, evidence-driven iteration.

The proposed workflow is goal-oriented. Design iteration terminates when: (1) DT validation metrics consistently exceed predefined thresholds, and (2) no further requirement- or cluster-level feedback is triggered. At this point, the conceptual design is considered sufficiently validated for downstream embodiment or engineering development, completing the methodological cycle.

4. Results

4.1. Stage 1 Results: Participants and Requirement Elicitation

User requirement data for the conceptual design of underwater rescue robots were obtained from questionnaire responses and expert interviews, forming the empirical basis for subsequent requirement structuring and prioritization.

The questionnaire results reflect user expectations regarding robot functionality, interface usability, operational safety, and overall rescue experience. Responses captured both perceived limitations of existing underwater rescue robots and anticipated features of next-generation systems. The survey involved three user groups: professional underwater rescuers, diving enthusiasts, and volunteer rescue personnel. A total of 110 questionnaires were distributed in Xi’an (Shaanxi Province) and Dalian (Liaoning Province). Among them, 109 responses were returned, and 106 were identified as valid, resulting in an effective response rate of 96%.

In addition to questionnaire data, qualitative insights were obtained from semi-structured interviews with three certified rescue divers. The interview results highlighted practical challenges encountered during real underwater rescue missions, user experiences with current robotic equipment, and expectations for future system capabilities. These narratives provided contextual explanations for the questionnaire findings and revealed operational needs that are difficult to quantify through survey data alone (The questionnaire is provided in

Appendix A).

Furthermore, the questionnaire survey and semi-structured interviews served complementary roles in the information-gathering process. The questionnaire provided broad, quantifiable patterns of user needs across multiple groups, while the interviews offered in-depth, experience-based insights that explained the rationale behind those patterns. Taken together, the two methods formed a mutually reinforcing data set, the structured survey quantified the prevalence of requirements, whereas the interviews contextualized, validated, and enriched those quantitative findings, ensuring both breadth and depth in the requirement elicitation stage.

All collected data were anonymized and systematically coded. The resulting data set represents the consolidated input for the subsequent KJ clustering of qualitative requirements (

Section 4.2) and Kano-based prioritization analysis (

Section 4.3), ensuring consistency and traceability across the stages of the proposed design process.

4.2. Stage 2 Results: KJ Clustering of User Requirements

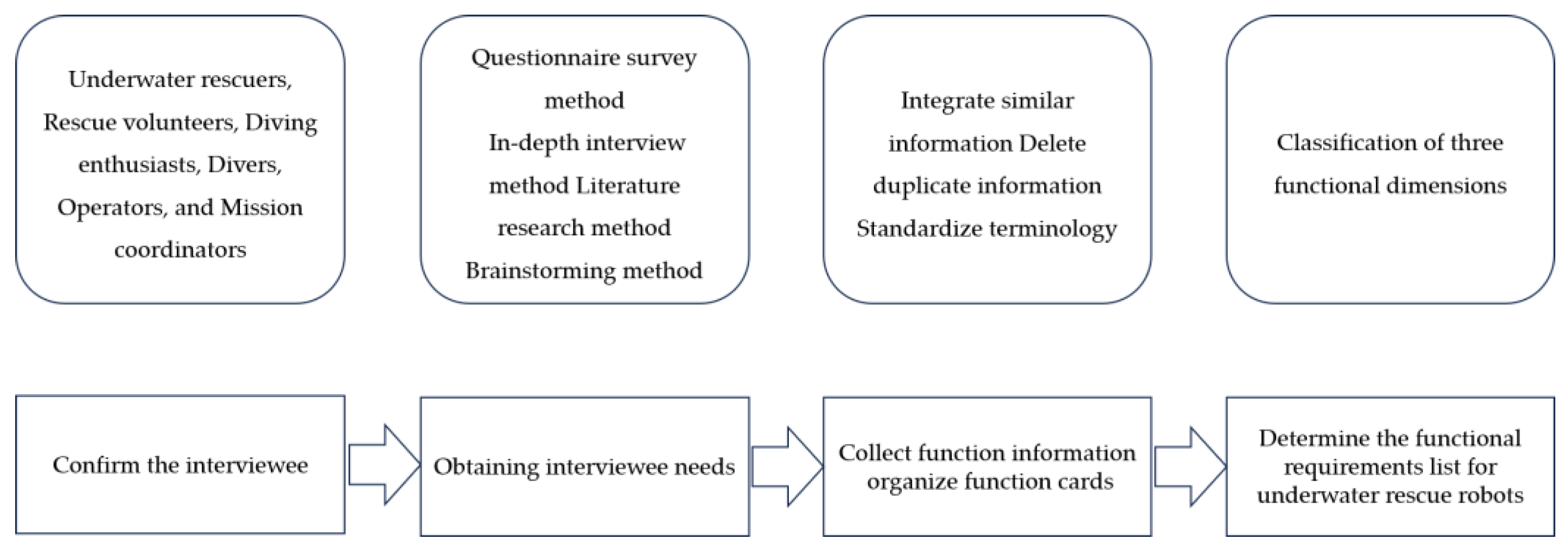

Based on the requirement data obtained in Stage 1, affinity clustering results were generated to structure user needs for underwater rescue robots. The KJ analysis transformed fragmented qualitative statements and survey inputs into a coherent and traceable requirement system, forming the basis for subsequent quantitative prioritization.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, individual user statements were first decomposed into discrete requirement fragments. These fragments were then grouped according to semantic similarity and functional relevance, resulting in several affinity clusters that reflected recurring user concerns across different participant groups. This clustering process reduced redundancy while preserving the diversity of user. The KJ-based requirement elicitation process shown in

Figure 2 is consistent with ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2018 guidelines for requirements engineering, particularly regarding stakeholder identification, needs elicitation, information structuring, and requirement synthesis.

The clustering results yielded a total of 18 functional requirement items, each represented as a requirement card and denoted as N1–N18. These requirements cover a broad spectrum of operational, interactional, and safety-related aspects, including image capture and recognition (N1), real-time video transmission (N2), expandability (N3), precise localization and navigation (N4), intelligent detection (N5), real-time data transfer (N6), dispersal of hazardous marine life (N7), prevention of misoperation (N8), high pressure resistance (N9), high reliability (N10), extended battery life (N11), corrosion resistance (N12), ease of operation (N13), simplified interface (N14), esthetic form (N15), moderate size (N16), remote control (N17), and user-friendly guidance (N18).

To facilitate structured analysis, the 18 requirement items were further organized into three higher-level requirement domains:

Practical functionality: referring to capabilities that directly support rescue tasks, operational efficiency, and intelligent assistance during missions.

Human–machine interaction: encompassing ease of operation, interface clarity, feedback mechanisms, and operator guidance.

Decision Safety: ensuring the accuracy of critical data feedback, timely hazard warnings, and the reliability of intelligent assistance to prevent misleading information that could compromise the rescue mission.

This three-tier requirement structure represents the primary outcome of the KJ clustering stage. It establishes a clear mapping between raw user input and abstracted design requirements, enabling traceable transition to quantitative evaluation. The resulting requirement set and hierarchical organization served as direct input for the Kano-based satisfaction analysis in Stage 3, ensuring that prioritization was grounded in empirically derived user needs.

4.3. Stage 3 Results: Kano-Based Requirement Prioritization

4.3.1. Kano Classification Results

Based on the requirement structure derived in Stage 2, a Kano survey was conducted to evaluate how each of the 18 functional requirements influences user satisfaction. To detect moderate effect sizes, G*power3 was used to determine the required sample size. A prior power analysis was conducted with a significance level of 0.05, a statistical power of 0.95, and an effect size of 0.4, resulting in a minimum required sample size of 70 participants. Accordingly, a total of 100 questionnaires were distributed, of which 86 were valid and included in the final analysis, yielding a valid response rate of 86%. Each Kano attribute category was determined by the dominant response frequency according to the standard Kano evaluation table.

The internal consistency of the questionnaire responses was verified through reliability analysis. The resulting Cronbach’s coefficient was 0.936, indicating a high level of response stability across functional attributes. Response coding and classification were conducted independently by two researchers, with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion, ensuring consistency in category assignment.

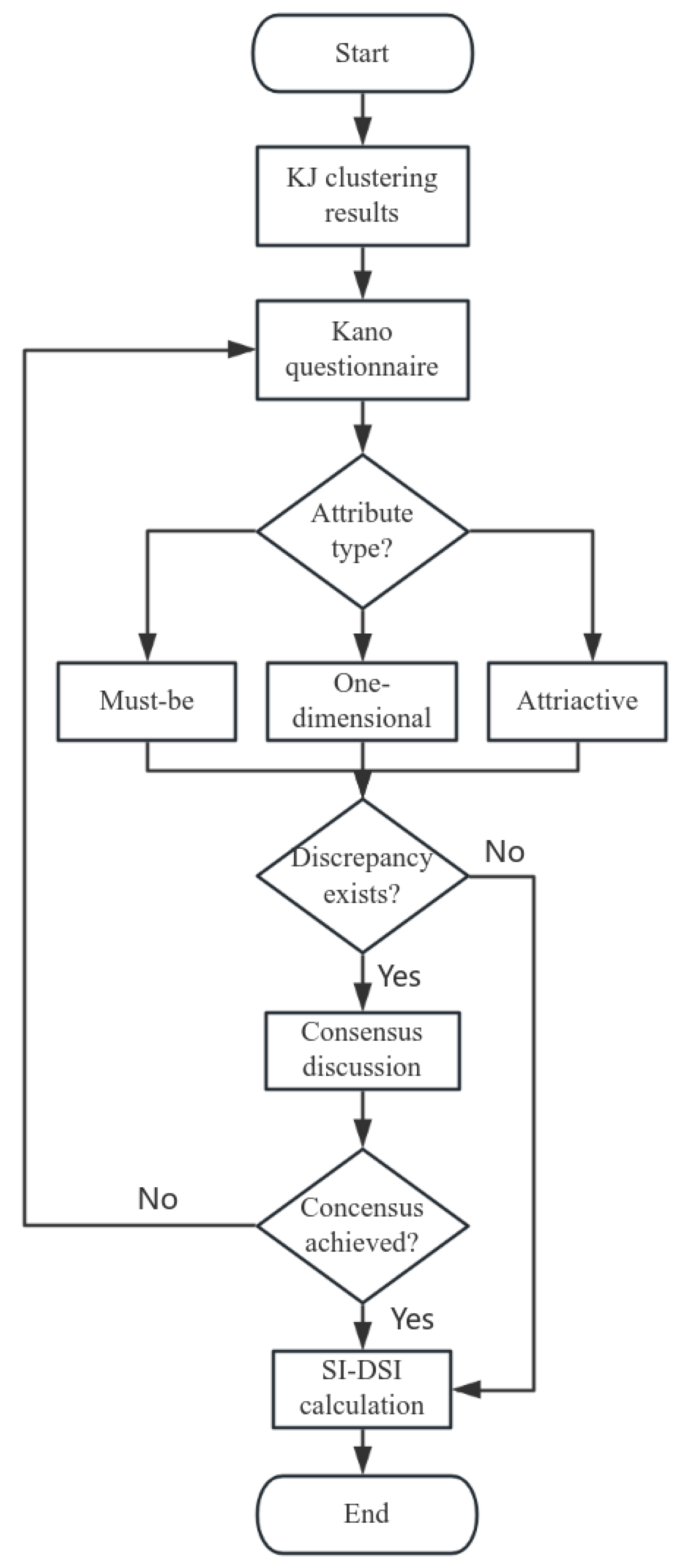

To increase methodological transparency and follow design-engineering conventions, the internal workflow of this stage (see

Figure 3) was formalized using Visio. The diagram clarifies how requirement items (N1–N18) enter the Kano evaluation stream, how functional/dysfunctional responses are coded, and how attribute types (A/O/M/I) are assigned through decision nodes (in the diagram, only A, O, and M attribute nodes are included). It further depicts the internal quality-control loop: if inconsistent, ambiguous, or low-confidence classifications emerge, responses are re-checked and recoded before SI/DSI indices are computed. This graphical representation highlights that Stage 3 contains an internal verification cycle, ensuring classification reliability without affecting upstream or downstream stages.

Table 2 summarizes the Kano classification results together with the corresponding SI and DSI values. Among the 18 requirements, three were classified as must-be (M), six as one-dimensional (O), five as attractive (A), and four as indifferent (I). Indifferent attributes were excluded from subsequent prioritization analysis, as their presence or absence was found to have minimal influence on user satisfaction.

Notably, must-be attributes were primarily associated with core operational reliability and interface clarity, whereas attractive attributes were concentrated in enhanced perception, situational awareness, and user guidance. One-dimensional attributes spanned multiple domains, reflecting functions that directly trade performance improvements for perceived value.

4.3.2. SI-DSI Quantitative Analysis and Priority Interpretation

To further interpret user sensitivity to individual requirements, Satisfaction Index (

) and Dissatisfaction Index (

) values were calculated for all 18 requirements. For a given requirement

, the Satisfaction Index

and Dissatisfaction Index

are calculated using Equations (1) and (2), respectively. In these formulas,

i ranges from 1 to 18, corresponding to the 18 functional requirements. The calculation example of

and

is supplemented in

Appendix B.

where

,

,

, and

represent the number of respondents who classified requirement

as attractive, one-dimensional, must-be, or indifferent, respectively.

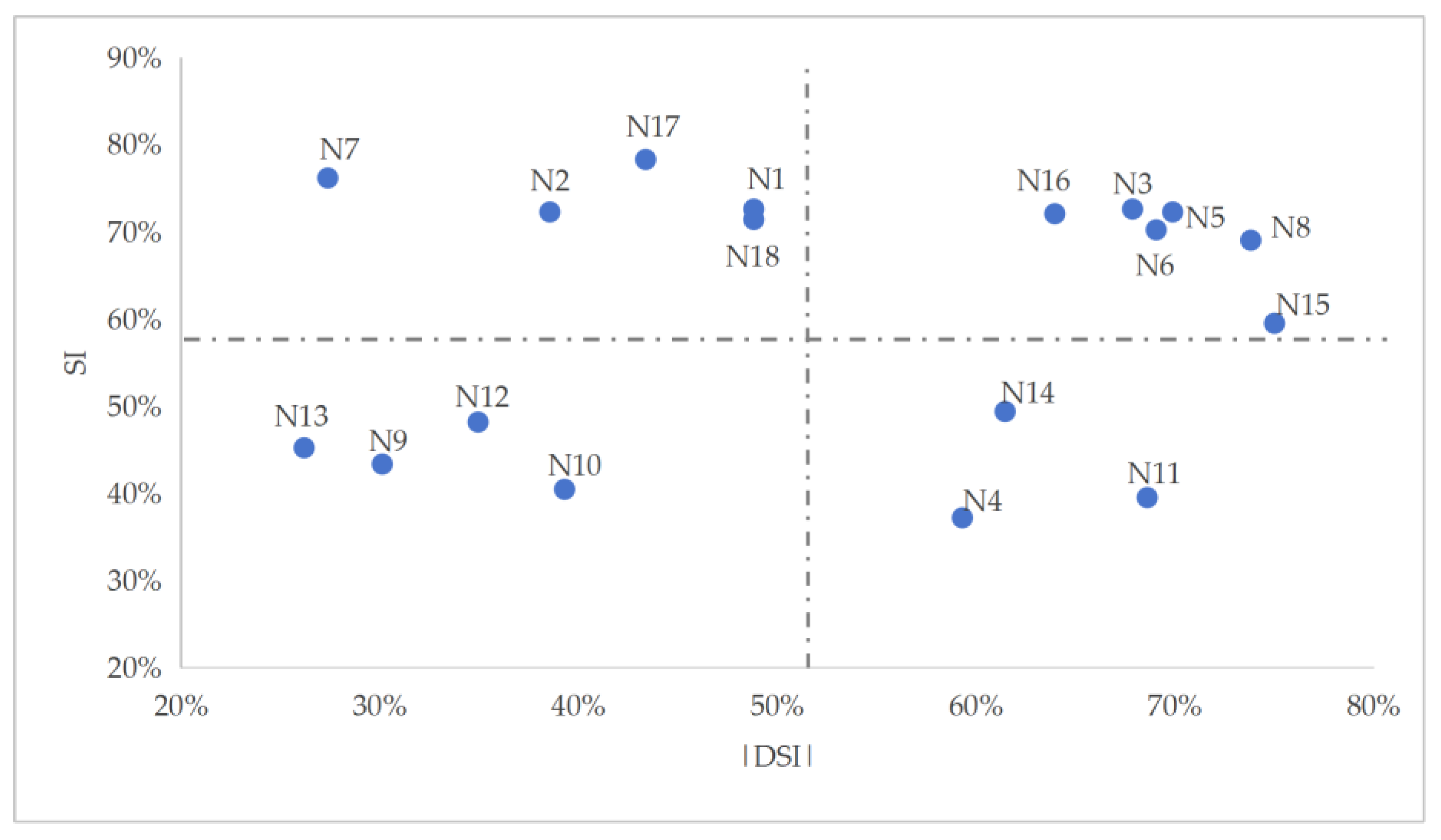

These indices quantify the extent to which satisfaction increases when a requirement is fulfilled and dissatisfaction increases when it is not, respectively.

The calculated

SI,

DSI values are listed in

Table 2 and

SI-|

DSI| visualized in the two-dimensional matrix shown in

Figure 4, where

SI is plotted on the vertical axis and the absolute value of

DSI (|

DSI|) on the horizontal axis. This matrix reveals four distinct behavioral zones corresponding to different satisfaction mechanisms.

One-dimensional attributes (high SI, high |DSI|): including expandability (N3), intelligent detection (N5), misoperation prevention (N8), real-time data transmission (N6), esthetic form (N15), and moderate size (N16), exert a strong bidirectional effect on user experience. Improvements in these attributes proportionally increase satisfaction, while deficiencies directly lead to dissatisfaction. These requirements therefore represent primary optimization targets in the conceptual design stage.

Attractive attributes (high SI, low |DSI|): such as hazardous marine life deterrence (N7), real-time video transmission (N2), image capture and recognition (N1), user-friendly guidance (N18), and remote control capability (N17), function as satisfaction amplifiers. Their inclusion significantly enhances perceived usability and operational confidence, particularly in complex rescue scenarios, although their absence does not critically undermine baseline acceptance.

Must-be attributes (low SI, high |DSI|): notably precise localization and navigation (N4), extended battery life (N11), and an intuitive interface (N14), constitute non-negotiable expectations. Users tend to take these functions for granted, but failure to meet them results in disproportionate dissatisfaction. In underwater rescue contexts, these attributes correspond directly to safety assurance and mission feasibility.

Indifferent attributes (low SI, low |DSI|) were excluded from design prioritization, as their contribution to user-perceived value was marginal.

The concentration of must-be attributes in the high |DSI| zone underscores that failure in core localization and navigation, power, or interface clarity is unforgivable in rescue contexts. The one-dimensional attributes form the key value proposition, and improving them directly increases satisfaction. The attractive attributes offer a strategic differentiation opportunity to exceed expectations once baseline performance is secured. Therefore, conceptual design for underwater rescue robots should first ensure compliance with must-be requirements, then prioritize one-dimensional attributes with strong bidirectional effects, and finally incorporate attractive attributes when design constraints permit. This layered prioritization strategy provides a quantitative basis for downstream design translation, ensuring that design effort is aligned with user-perceived value rather than merely functional completeness.

4.4. Stage 4 Results: Conceptual Design Translation and Modular Solution

Based on the prioritized requirements derived from the Kano-SI/DSI analysis in Stage 3, this stage translates user expectations into coherent conceptual design strategies. Rather than focusing on detailed engineering implementation, the results emphasize how different categories of requirements (must-be, one-dimensional, and attractive) inform design decisions at the levels of system architecture, functional configuration, and interaction logic.

4.4.1. Requirement-to-Concept Translation Based on Kano Categories

- (1)

Translation of must-be requirements

Must-be requirements represent baseline expectations for underwater rescue operations and are directly associated with operational safety and mission feasibility. Accordingly, their design translation prioritizes robustness, redundancy, and cognitive clarity.

(1) Precise Localization and Navigation

Underwater perception is fundamentally constrained by low visibility and signal attenuation. Visual sensing alone becomes unreliable in turbid or low-light environments, whereas acoustic sensing provides broader spatial awareness but lower resolution. To address this limitation, a hybrid perception strategy combining sonar and optical vision was adopted. Sonar modules support wide-area scanning and preliminary target localization, while onboard cameras enable local inspection and confirmation. This complementary configuration ensures reliable positioning across diverse underwater conditions and satisfies users’ baseline expectations for rescue effectiveness [

39].

(2) Extended Battery Life

Endurance is closely related to propulsion layout and thrust distribution. Prior studies indicate that the number and spatial arrangement of thrusters significantly influence energy efficiency and maneuvering stability [

40]. A cross-layout configuration with 4–6 thrusters was therefore selected, balancing fine-grained motion control with reduced energy consumption. This configuration supports prolonged missions while maintaining operational precision, directly addressing the must-be requirement for sufficient working duration [

41].

(3) Intuitive Interface

Given the time-critical and high-pressure nature of rescue tasks, interface intuitiveness is treated as a non-negotiable requirement. The interaction interface adopts a clear hierarchical layout, symbolic representations, and color-coded functional zones to minimize cognitive load and facilitate rapid comprehension [

42,

43]. Emergency-related functions are visually distinguished to support immediate recognition and response.

- (2)

Translation of one-dimensional requirements

One-dimensional requirements exhibit a strong bidirectional effect on satisfaction and dissatisfaction, making them key leverage points in conceptual optimization. Their translation focuses on scalability, adaptability, and performance–value balance.

To address expandability and multi-mission adaptability, a modular system architecture was developed. The robot is divided into a stationary core platform, including navigation, propulsion, power, and communication subsystems, and a set of interchangeable functional modules (e.g., manipulation units, sonar payloads, medical kits) [

44]. Sensors such as sonar and cameras are integrated as detachable modules, allowing the system to be reconfigured for different mission requirements and enabling rapid adaptation to diverse rescue scenarios. Standardized mechanical and electrical interfaces allow rapid module replacement in the field without structural modification, enabling flexible task reconfiguration.

For intelligent detection, traditional sonar perception is augmented with AI-assisted recognition to improve target identification and environmental awareness. Misoperation prevention is supported through real-time feedback, explicit functional zoning, and warning cues embedded within the interaction interface. Real-time data transmission is enabled through integrated communication and cloud-based data management, allowing operators to access mission data synchronously. With respect to esthetic form and size, the robot adopts moderate dimensions and rounded contours to ensure maneuverability in confined spaces and to reduce the risk of secondary injury during rescue.

- (3)

Translation of attractive requirements

Attractive requirements function as satisfaction enhancers, contributing to perceived system intelligence and operational confidence without being strictly essential for mission completion. Their design translation emphasizes experiential quality and situational support.

To address hazardous marine life deterrence, an auxiliary deterrent module combining visual monitoring and ultrasonic emission is integrated, enabling the robot to repel potentially dangerous organisms while minimizing ecological disturbance. Remote control functionality allows operators to manage the robot from land-based stations or vessels, improving operational flexibility. User-friendly guidance is implemented through clearly labeled controls and customizable interface panels, supporting rapid onboarding for users with varying experience levels.

For real-time video transmission and image capture, multi-directional imaging sensors are installed. A primary forward-facing camera supports navigation and inspection, while additional cameras provide 360° environmental awareness, enhancing situational perception and information richness during rescue operations.

4.4.2. Design Expression Across Esthetic, Functional, and Interaction Dimensions

- (1)

Esthetic design

Guided by the relative importance of requirements revealed by the SI–DSI analysis, esthetic design was developed as an integrated response to hydrodynamic efficiency, recognizability, and psychological reassurance. Biomimetic principles were employed to emulate streamlined aquatic forms, reducing drag and enhancing endurance while conveying visual affinity. Structural compactness supports navigation in complex underwater environments without compromising maneuverability.

Anti-jamming thrusters enable omnidirectional motion and precise hovering, while an integrated design reduces corrosion risk in wet conditions. To enhance visibility and recognizability in emergency contexts, the exterior adopts high-saturation rescue colors, primarily yellow and orange, with contrasting black and white accents [

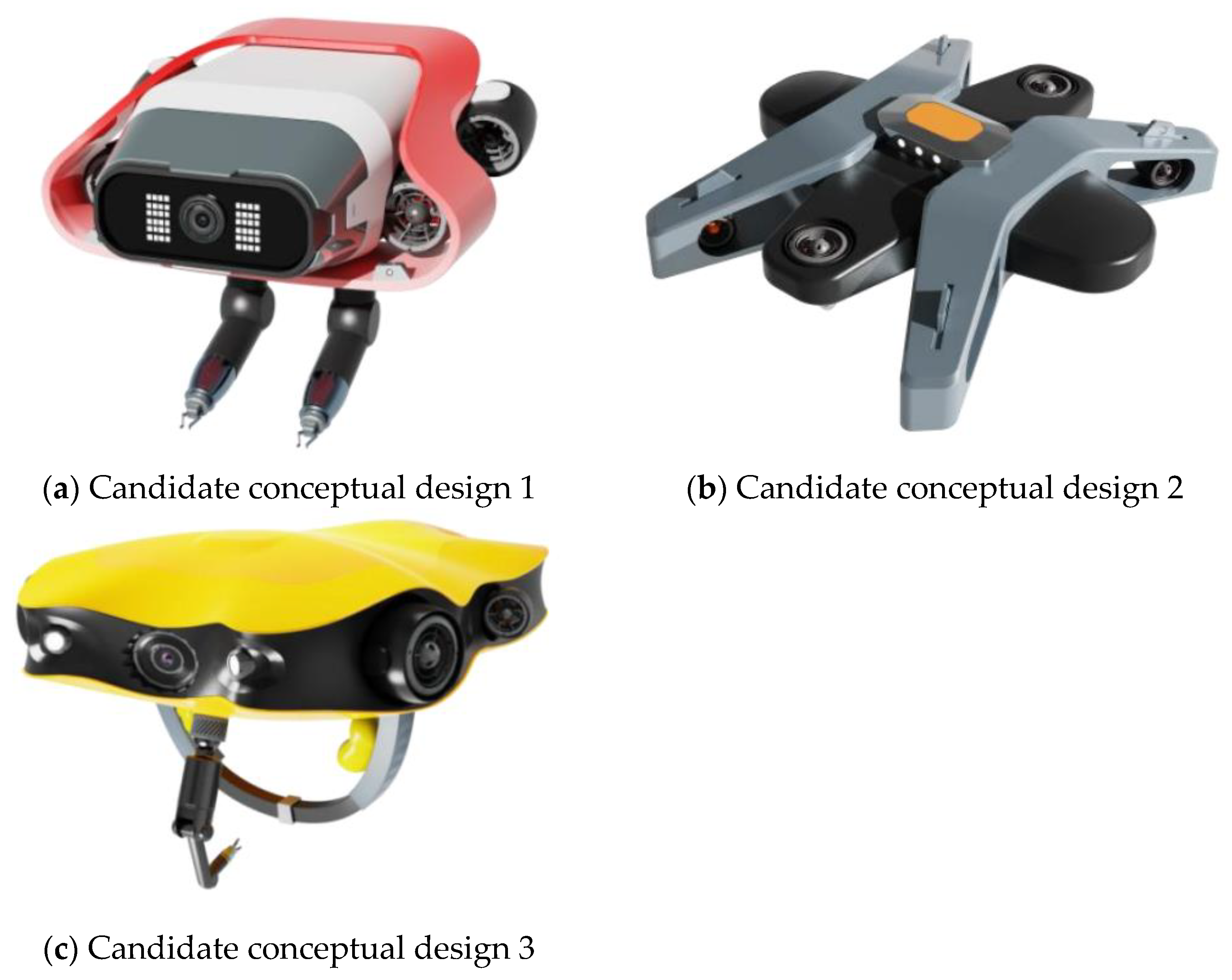

45]. Color differentiation is used to indicate functional zones, and emergency controls are highlighted in red for immediate identification. Three candidate conceptual designs developed are shown in

Figure 5. During the requirement-to-concept translation, multiple alternative implementations were considered for each key functional and interaction requirement. Different combinations of sensor modalities, propulsion layouts, and module configurations were explored for each must-be, one-dimensional, and attractive requirement. For each requirement, the design team evaluated these alternatives and integrated them into three distinct candidate conceptual designs (see

Figure 5), allowing comparative assessment of functionality, feasibility, and modular compatibility before finalizing the most suitable design choices.

- (2)

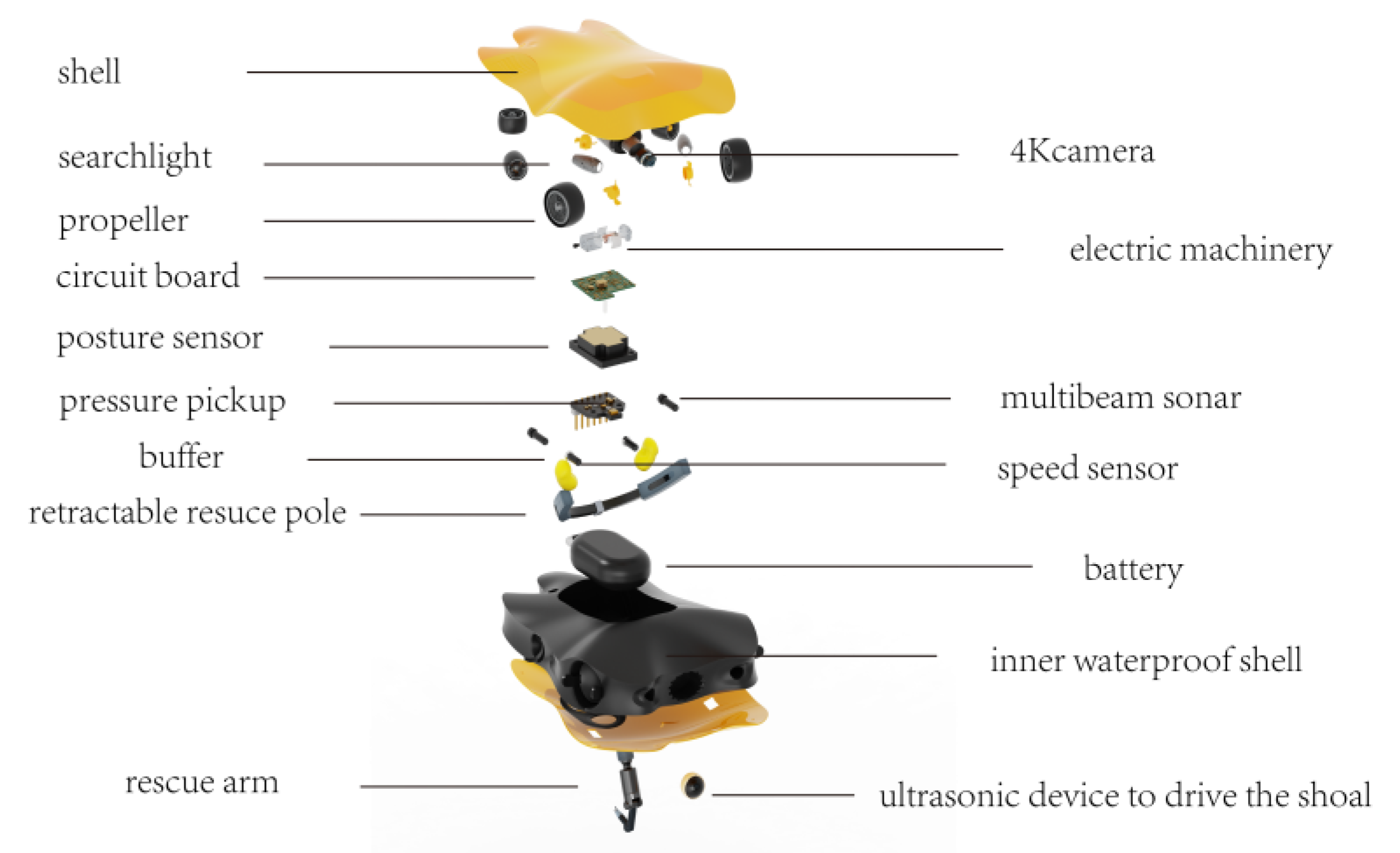

Functional design

Functionally, the robot is organized around three core capabilities: precise positioning, environmental monitoring, and rescue execution. The functional design described here emphasizes capability configuration and operational intent rather than finalized engineering specifications. Representative parameters or examples are provided only to illustrate possible conceptual ranges for user evaluation, not as fixed implementation decisions.

Precise positioning is designed to reliably determine its location in diverse underwater environments, using complementary sensing strategies to maintain localization under challenging conditions.

Environmental monitoring helps the robot continuously monitors environmental conditions, including depth, pressure, velocity, and attitude, and supports adaptive navigation and stability under dynamic flow conditions. Depth and pressure sensing ensures safe operation within structural limits [

46], while velocity and attitude data support navigation stability. Conceptual analysis methods help guide these capabilities without specifying exact algorithms or hardware

The system is functionally capable of assisting in underwater rescue tasks, including safe interaction with casualties and adaptation to environmental risks. Mechanisms for securing and supporting casualties are conceptually described to ensure versatility and safety, without detailing specific actuators or devices. Structural concepts and simulation of functional performance are shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, respectively.

- (3)

Interaction design

The interaction design prioritizes workflow clarity and decision support under time pressure. The interface is structured to reflect operators’ cognitive expectations, reducing unnecessary complexity while maintaining information completeness. A blue-to-black gradient background provides visual stability, with blue (#2CADFF) indicating functional areas and red (#FF2323) highlighting warnings and critical alerts (

Figure 8).

A persistent status bar displays connectivity information, while the main screen presents real-time environmental data to support navigation and search tasks. Directional controls provide immediate visual feedback, and camera functions support real-time viewing, recognition, and recording. Media galleries for images and videos include timestamped metadata and intuitive file management features. A structured settings panel and help module assist users in rapid problem resolution.

4.5. Stage 5 Results: DT-Based Validation of Conceptual Design

The final stage evaluates whether the conceptual solutions derived from the KJ-Kano prioritization can effectively support underwater rescue tasks under representative operational conditions. While the integration of KJ clustering, Kano analysis, and DT simulation does not constitute a methodological innovation per se, it provides a systematic framework for concept validation, enabling designers to iteratively assess requirement fulfillment, functional plausibility, and user experience before detailed engineering implementation. A functional DT prototype was employed to validate design decisions at the perceptual, interactional, and experiential levels, providing empirical evidence for design convergence rather than engineering-level performance optimization.

4.5.1. DT Prototype and Validation Scenarios

- (1)

DT Prototype Construction

A DT prototype representing the proposed underwater rescue robot and its interaction system was implemented based on the conceptual outcomes of Stages 2–4. The objective was to establish a high-fidelity virtual environment that enables immersive operation and quantitative user evaluation under simulated rescue scenarios. Validation focused on perceptual realism, interaction clarity, and functional plausibility.

The DT environment was developed using Unity3D (version 2022.3.5 LTS) as the core simulation platform. Unity was selected for its stable long-term support, physics integration, and capacity for multi-modal interaction development. The DT architecture consisted of four coordinated layers:

(1) Physical model layer.

The robot geometry was modeled in Rhino and imported into Unity via FBX format. Key structural features including the modular interfaces and biomimetic streamlined surface were preserved. Polygon optimization was applied to balance visual fidelity and simulation efficiency.

(2) Physical simulation layer.

Robot motion was simulated using Unity’s built-in PhysX engine, supporting six-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) movement. Buoyancy behavior was approximated using a simplified density-based model (ρ = 1000 kg/m

3 for seawater), and each propulsion unit was assigned a thrust of 45N (the maximum thrust is 120N), corresponding to typical small-class underwater rescue robots [

40]. These parameters were selected to ensure perceptually plausible simulation behavior rather than to represent finalized engineering specifications. While simplified, these parameters provided sufficiently realistic motion cues for user evaluation.

(3) Sensor simulation layer.

Virtual sensors were implemented to replicate core perceptual channels required for rescue operations, including: (a) a monocular camera with adjustable resolution (default 720 p at 30 fps); (b) a simplified sonar module based on spherical ray casting (range 0–10 m, 20 beams); and (c) depth-dependent light attenuation to emulate underwater turbidity. These abstractions enabled controlled testing of perception-driven interaction without introducing unnecessary computational complexity.

(4) Interaction interface layer.

User interfaces were first prototyped in Figma and then implemented using Unity UI Toolkit with C# scripting (.NET Framework 4.7). The interface supported real-time control and feedback, enabling systematic evaluation of usability, hierarchy clarity, and operational intuitiveness.

All layers were integrated into a unified DT system supporting real-time interaction, forming the experimental platform for subsequent user validation.

- (2)

Validation Experiment Setup

Following Bonett’s recommendation that a minimum of 30 observations ensures reliable estimation of measurement reliability [

47], 55 participants with diverse backgrounds were recruited to operate the DT system in simulated underwater rescue missions. The respondents consisted of 32 males (58.2%) and 23 females (41.8%), with ages ranging from 20 to 45 years (M = 28.4, SD = 5.7). The sample included 20 professional divers or underwater engineers (36.4%), 18 graduate students in robotics or marine engineering (32.7%), and 17 general users with no prior professional experience (30.9%). This distribution provided a balanced perspective combining expert and non-expert perspectives on the DT prototype. Participants performed predefined tasks and subsequently completed a structured questionnaire using a five-point Likert scale. For evaluation, the following dimensions were assessed:

Practical functionality, focusing on navigation effectiveness, rescue assistance, and modular adaptability.

Esthetic design, emphasizing underwater visibility and perceived form reliability.

Interactivity, measuring ease of operation, feedback clarity, and information hierarchy.

Intelligent experience, evaluating perceived assistance from intelligent detection and decision-making support.

The DT validation environment incorporated a structured task script reflecting realistic rescue scenarios. Participants completed three sequential operational tasks:

- (1)

Navigation task: guiding the robot through a constrained underwater corridor toward a designated waypoint;

- (2)

Search-and-identification task: locating a simulated target and confirming recognition using the intelligent detection module;

- (3)

Stabilization and reporting task: maintaining hover stability while selecting appropriate interaction commands.

The script ensured consistency across participants and enabled controlled comparison of functional, interaction, and intelligent performance dimensions.

In this research, the DT prototype was used as a conceptual validation baseline. Participants evaluated the modular expandability and upgrade potential by interacting with detachable modules, performing functional switching, and observing task adaptability within the DT environment. They rated each aspect using structured Likert-scale items, allowing quantitative assessment of perceived flexibility and usability. It should be emphasized that participants were presented with a high-fidelity conceptual model rather than detailed engineering specifications, ensuring that evaluations reflected functional plausibility and design intent rather than finalized hardware design.

4.5.2. User Evaluation and Statistical Results

Overall, participants reported positive perceptions of the DT prototype, with a mean satisfaction score of 3.83 across the four evaluated dimensions. Descriptive statistics for all evaluation metrics are summarized in

Table 3.

Among the four dimensions, intelligent experience received the highest average score (Mean = 3.95), followed by practical functionality (Mean = 3.90), interactivity (Mean = 3.78), and appearance (Mean = 3.70). These results indicate that users most strongly perceived benefits from intelligent assisted detection and decision-making support, while esthetic aspects, although acceptable, played a secondary role. The standard deviation (SD) values provide insight into the consistency of user perception across design dimensions. Lower SD values in intelligent experience (SD = 0.15 at the dimensional level) indicate a relatively consistent positive perception among participants, suggesting that intelligent assisted functions were intuitively understood regardless of prior experience. In contrast, higher SD values observed in appearance-related metrics reflect greater subjective variability, which is expected given individual differences in esthetic preference. Variability in interactivity-related items suggests that operational familiarity plays a role in perceived usability, reinforcing the need for adaptive or role-specific interface configurations.

Internal consistency analysis demonstrated strong questionnaire reliability. Cronbach’s coefficients were 0.86 for the overall scale, with high reliability for each sub-dimension: practical functionality ( = 0.91), interactivity ( = 0.89), intelligent experience ( = 0.92), and appearance ( = 0.94). The high Cronbach’s values confirm excellent internal consistency within each sub-scale, which is desirable for reliable measurement in this validation stage. However, it also suggests potential item redundancy or that the constructs are very narrowly defined. Future work should examine the theoretical structure of the scale through confirmatory factor analysis and refine the item set to enhance its discriminant validity, thereby enabling clearer differentiation between sub-dimensions.

A Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted to examine differences across the four design dimensions. This non-parametric approach was selected given the ordinal nature of the Likert-scale data and to avoid assumptions of normality required by parametric tests. The analysis revealed a statistically significant effect of evaluation dimension on user ratings, H(3) = 71.42, p < 0.05. Although the test indicated significant differences in the distribution of scores among the dimensions. The observed effect size () corresponds to a strong practical effect. Analysis of the mean ranks suggests that users tend to prioritize cognitive and decision-support benefits (intelligent experience) over esthetic refinement when operating under simulated emergency conditions. Since the Kruskal–Wallis test indicates global significance, post hoc pairwise comparisons (e.g., Dunn-Bonferroni tests) could be employed in future detailed analyses to identify specifically which dimensions differ significantly from one another.

4.6. Synthesis of Results and Design Convergence

The DT-based validation results confirm that the proposed conceptual design achieves balanced and satisfactory performance across functional, interactive, esthetic, and intelligent dimensions, while also revealing priorities for further refinement.

Participants particularly endorsed modular expandability (Mean = 4.01), validating the design strategy derived from one-dimensional Kano attributes and confirming the perceived value of task adaptability. In contrast, ease of operation (Mean = 3.60) received the lowest score within the practical functionality dimension, indicating the need to further simplify interaction logic and reduce cognitive load.

Within the interactivity dimension, intuitive understanding achieved the highest score (4.07), whereas information hierarchy clarity (3.64) scored lower, suggesting that interface structure requires optimization to support faster decision-making under high-pressure rescue conditions. The intelligent experience dimension achieved the highest overall evaluation (3.95), reinforcing the effectiveness of intelligent assisted detection and decision support mechanisms. Appearance ratings (Mean = 3.70) indicate acceptable visual performance while leaving room for refinement of biomimetic form and visual coherence.

As a multi-objective conceptual design study, the potential interdependence among evaluation dimensions warrants consideration. Although Pareto analysis is commonly applied in later-stage engineering optimization to explicitly identify trade-offs among competing performance objectives, this study focuses on the earlier, formative stage of conceptual design validation.

Unlike scenarios where evaluation dimensions are perceived uniformly, the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a strong differentiation in user priorities (H(3) = 71.42, p < 0.05), with a substantial effect size (). This result challenges the assumption that all design aspects are equally critical at the conceptual phase. Instead, it highlights a distinct hierarchy where users prioritize intelligent experience and practical functionality significantly over appearance.

These findings provide decisive inputs for subsequent engineering implementation. Rather than seeking a neutral compromise, future Pareto optimization should be directed by this observed user hierarchy. For instance, during the detailed design stage, resources and computational power should be disproportionately allocated to enhancing algorithmic intelligence and functional reliability, treating esthetic refinement (which received significantly lower priority) as a flexible constraint rather than a competing primary objective. This ensures that the final engineering embodiment aligns strictly with the utilitarian and cognitive demands of emergency rescue scenarios.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the DT serves not merely as a visualization tool but as an evidence-generating validation mechanism that closes the design loop depicted in

Figure 1. The DT enables continuous integration of user feedback, simulated operational data, and intelligent optimization, transforming validation from a static endpoint into a dynamic convergence process.

Although the current validation was conducted under simulated conditions, the DT-based approach ensures reproducibility and scalability for future empirical studies and physical prototyping. This DT–UCD coupling significantly shortens the design–test–refine cycle and reduces development risk, supporting a structured transition from conceptual design to downstream embodiment and engineering development.

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological Contribution of the KJ-Kano-DT Framework

The integration of the KJ method, Kano model, and DT technology represents a procedural, rather than merely combinatorial, contribution to conceptual design methodology. Traditional requirement analysis approaches tend to remain static, focusing either on qualitative clustering or quantitative prioritization, with limited mechanisms for validating user needs under realistic operational conditions.

What distinguishes the proposed framework from prior hybrid approaches is the explicit introduction of DT as a central validation and convergence mechanism within a closed-loop protocol. Existing studies combining KJ or Kano methods largely terminate at requirement ranking, implicitly assuming that prioritized attributes translate directly into effective design solutions. In contrast, this study operationalizes a domain-specific orchestration protocol that embeds requirement prioritization outcomes into a DT environment, where they are transformed into testable interactional and perceptual parameters.

By integrating qualitative elicitation, quantitative prioritization, and simulation-based validation into a unified workflow, the framework establishes a closed-loop requirement-design-validation cycle that moves systematically from requirement elicitation, through prioritization, to evidence-based design convergence. This study empirically demonstrates that this protocol functions effectively: (1) Kano-derived priorities (e.g., the low score for ‘ease of operation’) directly triggered design-level feedback, prompting interface iteration; (2) The DT generated the quantitative evidence presented in

Table 3, moving beyond conceptual illustration to substantiate the feedback decisions. This loop explicitly addresses the gap of the lack of feedback mechanisms that connect abstract user requirements with experiential validation under representative operational scenarios. Such an integrated process minimizes the likelihood of overlooking latent user needs and provides dynamic, data-driven evidence for continuous requirement refinement.

In particular, the DT component transforms abstract Kano attributes by mapping them onto observable user behaviors, satisfaction ratings, and interaction performance indicators. This transformation enhances requirement traceability, improves design transparency, and enables iterative refinement based on empirical evidence rather than designer intuition alone. Therefore, the core value of the framework lies in its executability and empirical demonstrability. It provides a concrete, testable methodological case study that addresses the pervasive user need-validation disconnect. From a methodological perspective, the methodological value lies in repositioning DT from a downstream verification artifact to a central analytical instrument within early-stage conceptual design.

5.2. Practical Implications for Underwater Rescue Robots

The proposed KJ-Kano-DT framework contributes directly to improving the reliability, usability, and adaptability of underwater rescue robots. Through DT-based esthetic validation, the biomimetic streamlined form and high-visibility color schemes were shown to support perceptual clarity and user confidence under low-visibility conditions, which are critical in emergency deployment scenarios.

Functional validation results highlighted the perceived effectiveness of camera–sonar integration for spatial awareness, sensor fusion for operational stability, and manipulator–fixation mechanisms for safe casualty handling. These findings confirm that the conceptual design aligns with user expectations and operational mental models at the interaction and perception levels. Furthermore, interaction design evaluation demonstrated that interface layouts and feedback logic were broadly consistent with operator habits and cognitive expectations, contributing to reduced cognitive workload and improved decision efficiency. These implications underscore that the primary value of the framework lies in de-risking early design decisions before costly physical prototyping, particularly for safety-critical robotic systems.

5.3. Generalizability to Other Complex Human–Machine Systems

Although the present study focuses on underwater rescue robots, the KJ–Kano–DT framework is inherently extensible to other complex human–machine systems, including unmanned aerial vehicles, autonomous ground vehicles, and medical service robots. These systems share core challenges, such as heterogeneous user populations, uncertain operational environments, and stringent safety and reliability requirements.

The proposed framework can be adapted by customizing requirement elicitation instruments, redefining Kano attributes based on contextual factors, and developing domain-specific DT models to simulate relevant operational scenarios. Its scalability lies in its hybrid structure, which combines qualitative insights, quantitative prioritization, and simulation-driven validation, ensuring that the framework remains both flexible and methodologically rigorous across different application contexts.

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

The limitations of this study include: First, the DT models constructed in Unity3D employed approximate hydrodynamic and sensor simulations, which cannot fully replicate the complexity of real-world fluid dynamics or acoustic propagation in underwater environments. Consequently, the validation results could be only interpreted as conceptual and interaction-level evidence. Second, the DT-based evaluation mainly focused on perceptual, interactional, and experiential metrics within representative rescue scenarios. While this aligns with the formative goals of conceptual design, the study lacked a controlled comparison with an existing benchmark robot or alternative design concept. As a result, the framework’s relative advantage in producing superior designs remains unquantified. Furthermore, the evaluation did not systematically explore edge cases or rare failure modes that might emerge in prolonged or extreme field deployments. Third, regarding participant sampling, while the study included a mix of experts, students, and general users, recruitment primarily occurred through professional and academic networks. This approach may introduce selection bias, as the sample may not fully or proportionally represent the entire spectrum of potential end-user populations, such as frontline rescue team members. Consequently, the generalizability of the findings to all professional rescuers should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the sample size of 55 participants imposes limitations on the statistical generalizability of subjective evaluations. From a statistical perspective, this sample size exceeds commonly accepted thresholds for reliability analysis and exploratory user studies: Cronbach’s values above 0.85 across all dimensions indicate stable internal consistency, and prior methodological research suggests that samples above 30 participants are adequate for detecting medium effect sizes in usability and perception studies. However, the sample remains insufficient for fine-grained subgroup comparisons (e.g., expert vs. novice operators) or inferential generalization to the entire population of professional rescuers.

Future research should therefore expand participant diversity and sample size through broader and more randomized sampling strategies, include benchmark comparisons, incorporate hardware-in-the-loop experiments, and conduct field trials in controlled aquatic environments. In such contexts, the DT can evolve from a virtual surrogate into a hybrid predictive and diagnostic instrument. Moreover, integrating machine learning techniques within the DT architecture would allow automatic correlation of user behavior, performance metrics, and environmental variables, enabling adaptive and data-driven requirement refinement. Such extensions will further enhance the robustness, fidelity, and applicability of the KJ–Kano–DT framework for designing safety-critical human–machine systems.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed and empirically examined a user-centered conceptual design framework for underwater rescue robots by procedurally integrating the KJ method, Kano model, and DT technology. Rather than introducing new individual methods, the contribution of this research lies in formalizing how qualitative requirement elicitation, quantitative satisfaction-driven prioritization, and simulation-based validation can be coherently orchestrated into a stage-gated, evidence-driven design workflow suitable for early-stage conceptual design.

At a theoretical level, this work contributes to design methodology research by clarifying the complementary roles of KJ clustering and Kano analysis within a unified requirements engineering process. The study demonstrates how open-ended qualitative insights derived from semi-structured interviews can be systematically structured, quantified, and translated into design priorities, thereby reducing the common disconnect between exploratory user research and downstream design decision-making. Furthermore, by embedding requirement validation within a DT environment, the framework extends traditional user-centered design by introducing a dynamic, feedback-enabled mechanism that supports requirement refinement before physical embodiment. This procedural integration provides a replicable methodological reference for conceptual design in safety-critical human–machine systems.

From a design perspective, the research results show that the framework effectively transforms heterogeneous user needs into validated conceptual solutions across functional, interactional, esthetic, and intelligent dimensions. The Kano-SI/DSI analysis revealed clear priority structures among must-be, one-dimensional, and attractive requirements, which directly informed modular architecture, interaction logic, and form development. DT-based validation further confirmed that intelligent assisted detection and modular expandability were perceived as the most valuable attributes, while also identifying interaction simplicity and interface hierarchy as key areas for refinement. In this sense, the DT functioned not merely as a visualization tool, but as an evidence-generating validation medium that supported design convergence under controlled, repeatable conditions.

The practical implications of this research extend beyond underwater rescue robots. The proposed KJ-Kano-DT framework is particularly suitable for conceptual design contexts characterized by complex operational environments, heterogeneous user groups, and limited availability of real-world test data. By enabling early identification of critical requirements and perceptual trade-offs, the framework helps reduce development risk and shortens the design-test-refine cycle prior to costly prototyping and field trials.

In summary, this study establishes a structured and transparent pathway from user requirement elicitation to validated conceptual design. By positioning Digital Twins as a bridge between user perception and design decision-making, the proposed framework advances user-centered conceptual design practice for complex, high-risk human–machine systems.