Limited Short-Term Reliability of Key Joint Angles in Biomechanical Running Gait Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

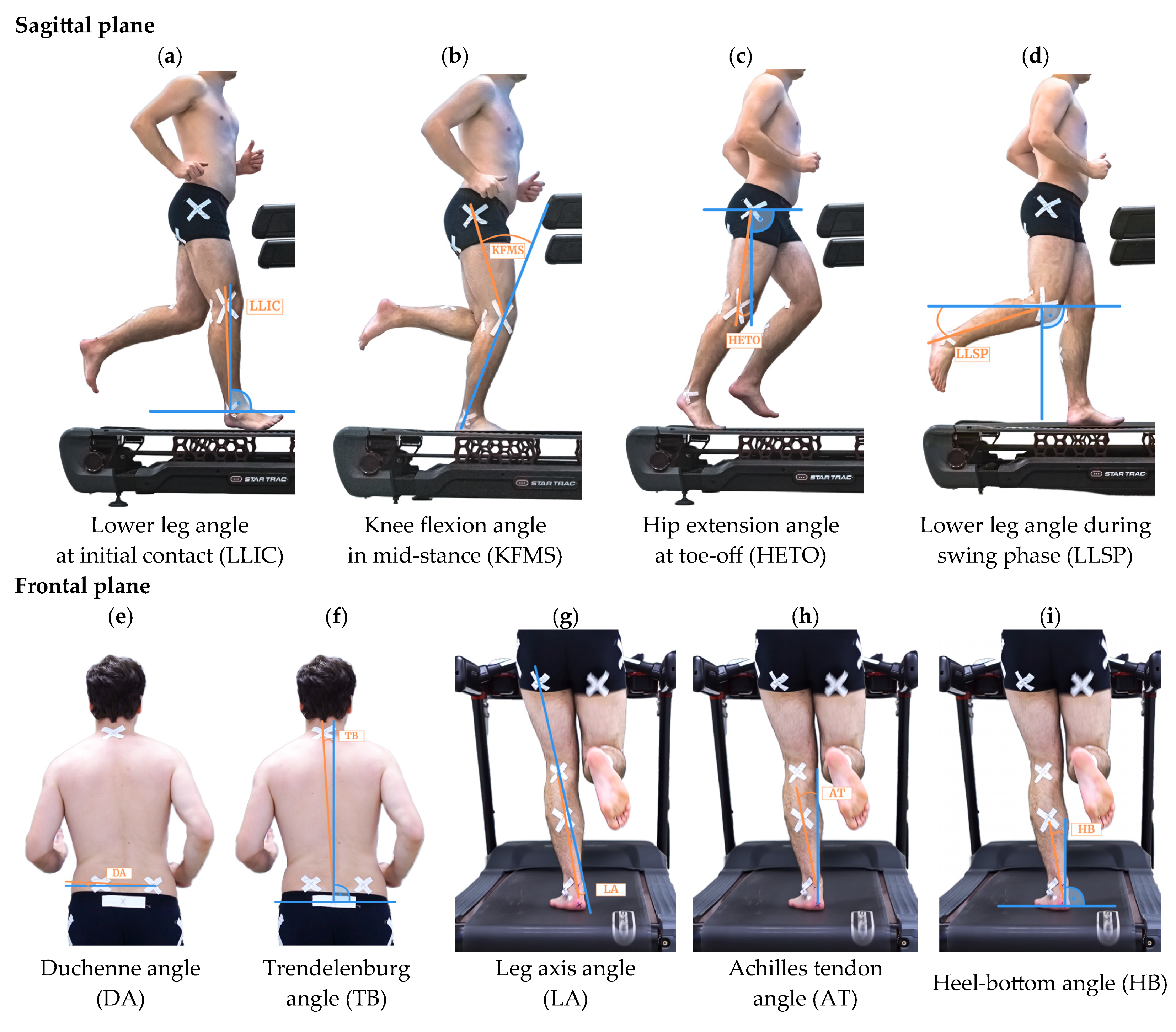

| LLIC | Lower Leg Angle at Initial Contact |

| KFMS | Knee Flexion Angle at Mid-Stance |

| HETO | Hip Extension Angle at Toe-Off |

| LLSP | Lower Leg Angle at Swing Phase |

| DA | Duchenne Angle |

| TB | Trendelenburg Angle |

| LA | Leg Axis Angle |

| AT | Achilles-Tendon Angle |

| HB | Heel Bottom Angle |

References

- Van Mechelen, W. Running injuries. A review of the epidemiological literature. Sports Med. 1992, 14, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; Pearson, L.T.; Barry, G.; Young, F.; Lennon, O.; Godfrey, A.; Stuart, S. Wearables for Running Gait Analysis: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Kokko, S.; Kujala, U.M.; Heinonen, A.; Kelly, P.; Koski, P.; Foster, C. Health benefits of different sport disciplines for adults: Systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willwacher, S.; Kurz, M.; Robbin, J.; Thelen, M.; Hamill, J.; Kelly, L.; Mai, P. Running-Related Biomechanical Risk Factors for Overuse Injuries in Distance Runners: A Systematic Review Considering Injury Specificity and the Potentials for Future Research. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueberschär, O.; Fleckenstein, D.; Warschun, F.; Kränzler, S.; Walter, N.; Hoppe, M.W. Measuring biomechanical loads and asymmetries in junior elite long-distance runners through triaxial inertial sensors. Sports Orthop. Traumatol. 2019, 35, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S.; Burke, A.; Whyte, E.F.; O’Connor, S.; Gore, S.; Moran, K.A. Running towards injury? A prospective investigation of factors associated with running injuries. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, L.; Evans, M.; Wade, L.; Cosker, D.P.; McGuigan, M.P.; Bilzon, J.L.; Colyer, S.L. The development and evaluation of a fully automated markerless motion capture workflow. J. Biomech. 2022, 144, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G. Smartphone videos-driven musculoskeletal multibody dynamics modelling workflow to estimate the lower limb joint contact forces and ground reaction forces. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 3841–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.S.; Galano, J.P.; Cardoso, F.; Buzzachera, C.F.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Fernandes, R.J. Kinematical and Physiological Responses of Overground Running Gait Pattern at Different Intensities. Sensors 2024, 24, 7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, S.; Prigent, G.; Stöggl, T.; Martínez, A.; Snyder, C.; Gremeaux-Bader, V.; Aminian, K. Biomechanical Response of the Lower Extremity to Running-Induced Acute Fatigue: A Systematic Review. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 646042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Fekete, G.; Baker, J.S.; Liang, M.; Xuan, R.; Gu, Y. Effects of running fatigue on lower extremity symmetry among amateur runners: From a biomechanical perspective. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 899818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrick, T.R.; Dereu, D.; McLean, S.P. Impacts and kinematic adjustments during an exhaustive run. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan-Roper, M.; Hunter, I.; Myrer, J.W.; Eggett, D.L.; Seeley, M.K. Kinematic changes during a marathon for fast and slow runners. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2012, 11, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boey, H.; Aeles, J.; Schütte, K.; Vanwanseele, B. The effect of three surface conditions, speed and running experience on vertical acceleration of the tibia during running. Sports Biomech. 2017, 16, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Collop, A.C.; Batt, M.E. Surface effects on ground reaction forces and lower extremity kinematics in running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 1919–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.R.; Snow, R.; Agruss, C. Changes in Distance Running Kinematics with Fatigue. Int. J. Sport. Biomech. 1991, 7, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzis, A.; Brüggemann, G.P.; Metzler, V. The effect of speed on leg stiffness and joint kinetics in human running. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, B.; De Clercq, D.; Aerts, P. Biomechanical analysis of the stance phase during barefoot and shod running. J. Biomech. 2000, 33, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khassetarash, A.; Vernillo, G.; Martinez, A.; Baggaley, M.; Giandolini, M.; Horvais, N.; Millet, G.Y.; Edwards, W.B. Biomechanics of graded running: Part II-Joint kinematics and kinetics. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1642–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, G.R.; Leary, B.K.; Nguyen, A.-D.; McCrory, J.L. A comparison of running biomechanics on track, asphalt, grass, and treadmill using wearable sensors. Sports Biomech. 2025, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.; Richards, J.; Taylor, P.J.; Edmundson, C.J.; Brooks, D.; Hobbs, S.J. Three-dimensional kinematic comparison of treadmill and overground running. Sports Biomech. 2013, 12, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.P.; Barton, C.; Jones, P.R.; Morrissey, D. The biomechanical differences between barefoot and shod distance running: A systematic review and preliminary meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 1335–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, V.; Knierim Correia, C.; Dell’Antonio, E.; Mochizuki, L.; Ruschel, C. Biomechanics of Shod and Barefoot Running: A Literature Review. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2020, 26, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.M.; Yawar, A.; Lieberman, D.E.; Walsh, C.J. Predicting overstriding with wearable IMUs during treadmill and overground running. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquardt, M. Laufen und Laufanalyse. Medizinische Betreuung von Läufern; Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012; Volume 1, p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, G. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, R.; Guadagnin, E.C.; Emilio de Carvalho, J.; Metsavaht, L.; Leporace, G. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change in pelvis and lower limb coordination during running assessed with modified vector coding. J. Biomech. 2024, 174, 112259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzuto, F.; de Oliveira, C.F.; Soares, T.S.A.; Rago, V.; Silva, G.; Oliveira, J. Relationship Between Running Economy and Kinematic Parameters in Long-Distance Runners. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Thorstensson, A.; Halbertsma, J. Changes in leg movements and muscle activity with speed of locomotion and mode of progression in humans. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1985, 123, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, J.P.; Sell, T.C.; Chu, Y.; Lovalekar, M.; Burdett, R.G.; Lephart, S.M. Running kinematics and shock absorption do not change after brief exhaustive running. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellis, E.; Liassou, C. The effect of selective muscle fatigue on sagittal lower limb kinematics and muscle activity during level running. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2009, 39, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandbergen, M.A.; Marotta, L.; Bulthuis, R.; Buurke, J.H.; Veltink, P.H.; Reenalda, J. Effects of level running-induced fatigue on running kinematics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture 2023, 99, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.; De Bie, J.; Vanfleteren, R.; Hoogkamer, W.; Vanwanseele, B. Novice runners show greater changes in kinematics with fatigue compared with competitive runners. Sports Biomech. 2018, 17, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzak, K.N.; Stickley, C.D. Fatigue-Induced Hip-Abductor Weakness and Changes in Biomechanical Risk Factors for Running-Related Injuries. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazati, S.; Caplan, N.; Matabuena, M.; Hayes, P.R. Fatigue Induced Changes in Muscle Strength and Gait Following Two Different Intensity, Energy Expenditure Matched Runs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogu, S.; Gandbhir, V.N. Trendelenburg Sign; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, F.; Li, N.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhu, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Tsai, T.Y.; Wang, S. The effects of marathon running on three-dimensional knee kinematics during walking and running in recreational runners. Gait Posture 2020, 75, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willwacher, S.; Sanno, M.; Brüggemann, G.P. Fatigue matters: An intense 10 km run alters frontal and transverse plane joint kinematics in competitive and recreational adult runners. Gait Posture 2020, 76, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barbero, S.; González-Mohíno, F.; Rodrigo-Carranza, V.; Santos-Garcia, D.J.; Boullosa, D.; González-Ravé, J.M. Acute effects of interval training on running kinematics in runners: A systematic review. Gait Posture 2023, 103, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Joint Angle | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t5 | t6 | t7 | t8 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | Mean | Med. | ±SD | |

| [°] | [°] | [°] | [°] | [°] | [°] | [°] | [°] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sagittal Plane | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LLIC | 9 | 9.29 | 8.73 | ±3.46 | 9.01 | 8.63 | ±3.38 | 9.13 | 7.92 | ±3.43 | 9.16 | 8.36 | ±3.39 | 9.32 | 8.95 | ±3.68 | 8.83 | 7.46 | ±3.66 | 9.44 | 8.54 | ±3.63 | 9.30 | 8.57 | ±3.98 |

| KFMS | 9 | 38.49 | 37.87 | ±5.76 | 38.65 | 38.26 | ±5.81 | 38.00 | 37.91 | ±5.63 | 38.35 | 36.89 | ±5.13 | 38.96 | 38.34 | ±5.58 | 39.38 | 37.47 | ±6.39 | 39.01 | 38.49 | ±5.55 | 38.98 | 38.21 | ±5.78 |

| HETO | 9 | 17.32 | 17.33 | ±5.65 | 17.38 | 18.40 | ±5.96 | 17.56 | 18.74 | ±5.71 | 18.17 | 18.67 | ±5.32 | 18.24 | 18.79 | ±5.36 | 18.29 | 18.32 | ±5.23 | 18.67 | 18.52 | ±5.65 | 19.14 | 19.01 | ±5.59 |

| LLSP | 9 | −10.79 | −12.33 | ±7.37 | −9.44 | −11.30 | ±7.15 | −9.28 | −10.99 | ±7.27 | −8.96 | −10.65 | ±7.17 | −9.27 | −9.65 | ±6.68 | −9.30 | −10.12 | ±6.55 | −9.49 | −10.54 | ±7.22 | −9.24 | −10.87 | ±7.54 |

| Frontal Plane | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DA | 8 | 4.00 | 3.80 | ±1.53 | 4.29 | 3.92 | ±1.24 | 4.42 | 4.22 | ±1.17 | 4.44 | 4.23 | ±1.16 | 4.57 | 4.55 | ±1.35 | 4.63 | 4.51 | ±1.32 | 4.81 | 4.42 | ±1.51 | 4.59 | 4.30 | ±1.37 |

| TB | 10 | 4.51 | 5.05 | ±1.47 | 4.78 | 5.04 | ±1.46 | 4.81 | 5.29 | ±1.48 | 4.98 | 5.20 | ±1.45 | 5.11 | 5.22 | ±1.37 | 5.09 | 5.21 | ±1.35 | 5.20 | 5.41 | ±1.37 | 5.26 | 5.60 | ±1.38 |

| LA | 10 | −6.15 | −6.52 | ±2.99 | −6.21 | −6.68 | ±2.83 | −6.39 | −6.48 | ±2.90 | −6.55 | −6.33 | ±2.66 | −6.74 | −6.41 | ±2.80 | −6.62 | −6.74 | ±2.93 | −6.80 | −6.19 | ±3.02 | −6.87 | −6.53 | ±3.07 |

| AT | 11 | 11.08 | 11.32 | ±3.43 | 11.19 | 10.95 | ±3.61 | 11.37 | 11.72 | ±3.59 | 11.38 | 10.99 | ±4.02 | 11.53 | 11.00 | ±3.56 | 11.28 | 10.82 | ±3.56 | 11.52 | 11.44 | ±3.65 | 11.67 | 12.14 | ±3.68 |

| HB | 11 | 2.31 | 2.34 | ±3.36 | 2.04 | 1.79 | ±3.20 | 1.95 | 1.91 | ±3.19 | 1.94 | 2.03 | ±3.07 | 1.87 | 1.88 | ±3.05 | 1.82 | 2.07 | ±2.95 | 1.77 | 2.14 | ±2.99 | 1.80 | 1.87 | ±2.82 |

| Time | Running Condition | Time × Running Condition | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Angle | Df | F | p | ηp2 | Df | F | p | ηp2 | Df | F | p | ηp2 |

| Sagittal plane | ||||||||||||

| LLIC | 3.52 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 1.15 | 22.15 | <0.001 | 0.74 | 14.00 | 1.26 | 0.34 | 0.14 |

| KFMS | 3.55 | 7.70 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 1.46 | 4.33 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 14.00 | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| HETO | 2.40 | 10.21 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 1.39 | 12.33 | <0.01 | 0.61 | 14.00 | 1.22 | 0.27 | 0.13 |

| LLSP | 1.69 | 1.59 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 1.42 | 67.91 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 14.00 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.01 |

| Frontal Plane | ||||||||||||

| DA | 4.31 | 4.41 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 1.72 | 21.07 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 6.26 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.04 |

| TB | 4.17 | 13.13 | <0.001 | 0.39 | 1.71 | 21.31 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 7.41 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.03 |

| LA | 4.08 | 2.86 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 1.49 | 29.23 | <0.001 | 0.59 | 7.38 | 3.45 | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| AT | 4.60 | 1.02 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 1.41 | 12.10 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 4.72 | 1.75 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| HB | 2.50 | 3.68 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 1.23 | 1.85 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 14.00 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.06 |

| Joint Angle | ICC | MDC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | [°] | |

| Sagittal plane | ||||

| LLIC | 0.842 | 0.751 | 0.916 | 3.94 |

| KFMS | 0.921 | 0.869 | 0.960 | 4.50 |

| HETO | 0.959 | 0.931 | 0.979 | 3.12 |

| LLSP | 0.927 | 0.882 | 0.961 | 5.33 |

| Frontal Plane | ||||

| DA | 0.867 | 0.786 | 0.930 | 1.35 |

| TB | 0.929 | 0.890 | 0.960 | 1.05 |

| LA | 0.920 | 0.874 | 0.955 | 2.27 |

| AT | 0.903 | 0.851 | 0.944 | 3.14 |

| HB | 0.971 | 0.954 | 0.984 | 1.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pökel, C.; Bartsch, J.; Schödel, C.; Ueberschär, O. Limited Short-Term Reliability of Key Joint Angles in Biomechanical Running Gait Analyses. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010133

Pökel C, Bartsch J, Schödel C, Ueberschär O. Limited Short-Term Reliability of Key Joint Angles in Biomechanical Running Gait Analyses. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010133

Chicago/Turabian StylePökel, Christoph, Julia Bartsch, Cindy Schödel, and Olaf Ueberschär. 2026. "Limited Short-Term Reliability of Key Joint Angles in Biomechanical Running Gait Analyses" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010133

APA StylePökel, C., Bartsch, J., Schödel, C., & Ueberschär, O. (2026). Limited Short-Term Reliability of Key Joint Angles in Biomechanical Running Gait Analyses. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010133