Assessment of Equilibrium Path Sensitivity in Truss Domes Vulnerable to Node Snap-Through with Respect to Load Distribution

Abstract

1. Introduction

- load multiplier µ = 1 was at every node,

- equilibrium paths using the incremental Newton–Raphson method were calculated,

- only geometric nonlinearity was considered (no material nonlinearity),

- in each nonlinear analysis, snap-through of the apex node (Node 1)—i.e., the apex node of the truss—was investigated.

2. Research Assumptions and Methods

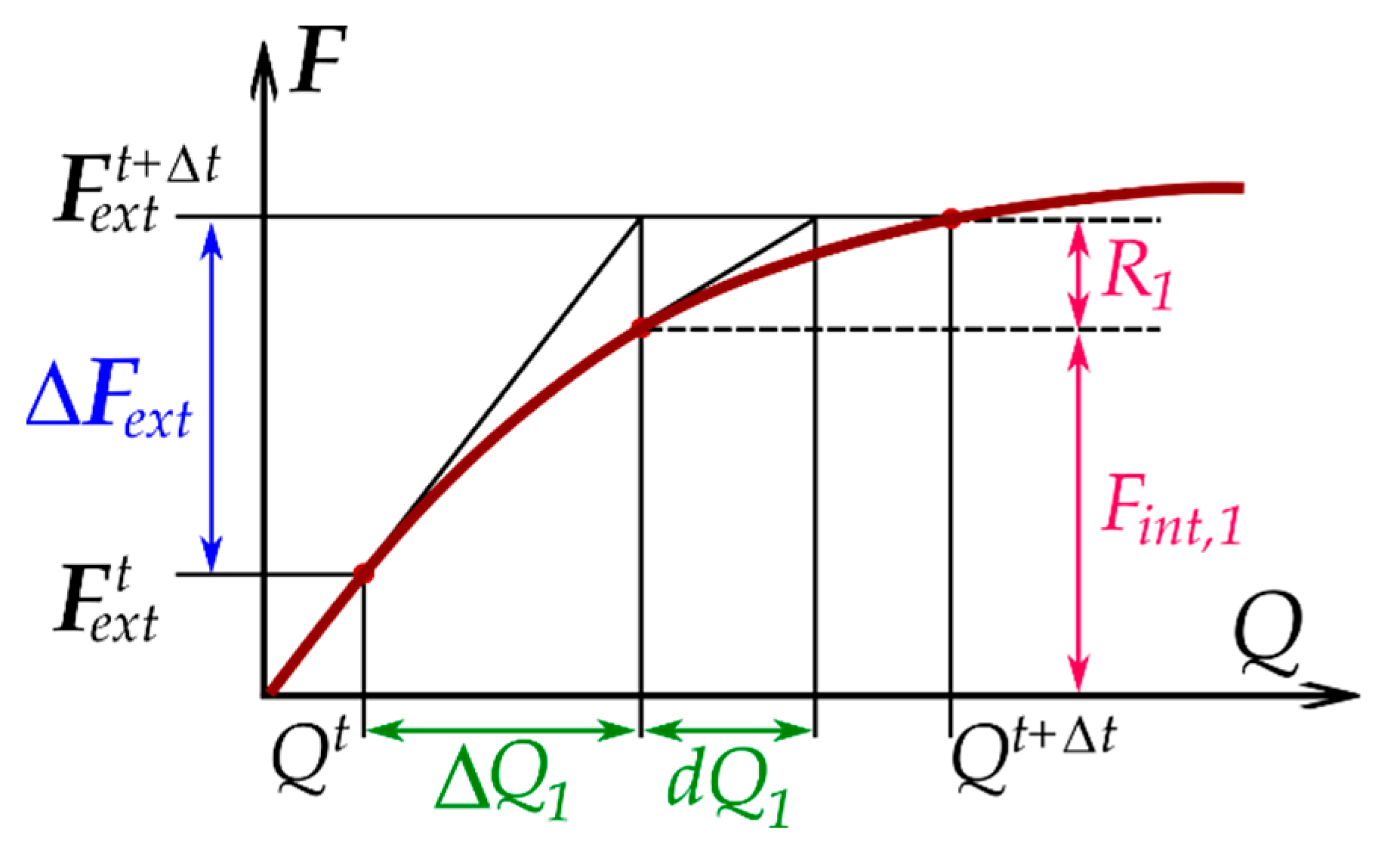

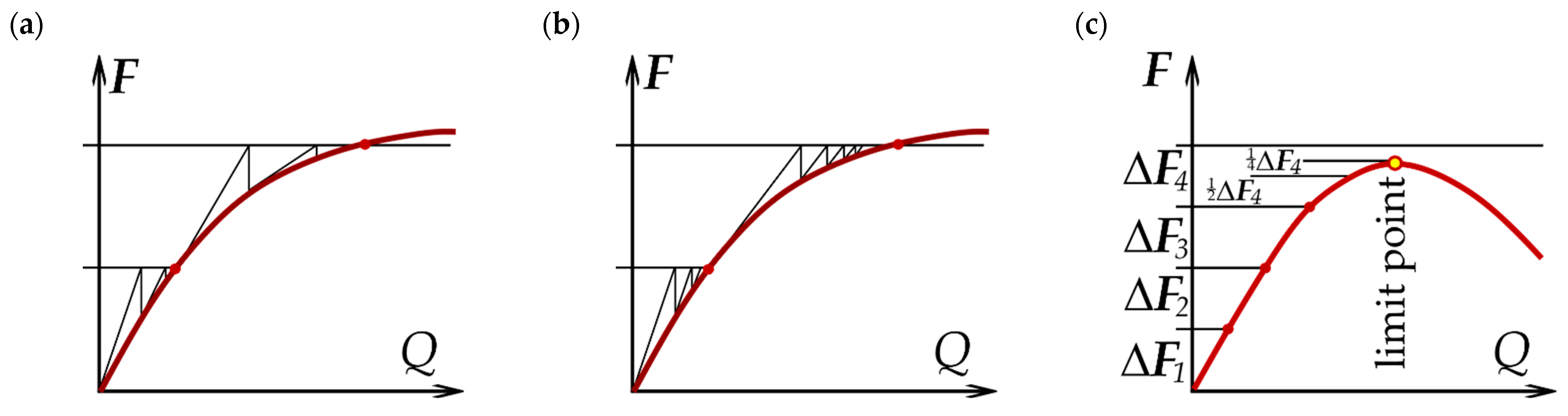

2.1. Incremental–Iterative Analysis

- load control,

- displacement control,

- arc-length control.

- First iteration j = 1 is as follows:

- Subsequent iterations, j = 2, 3, …, are performed until the adopted convergence criterion is satisfied as follows:where —residual (unbalanced) force vector.

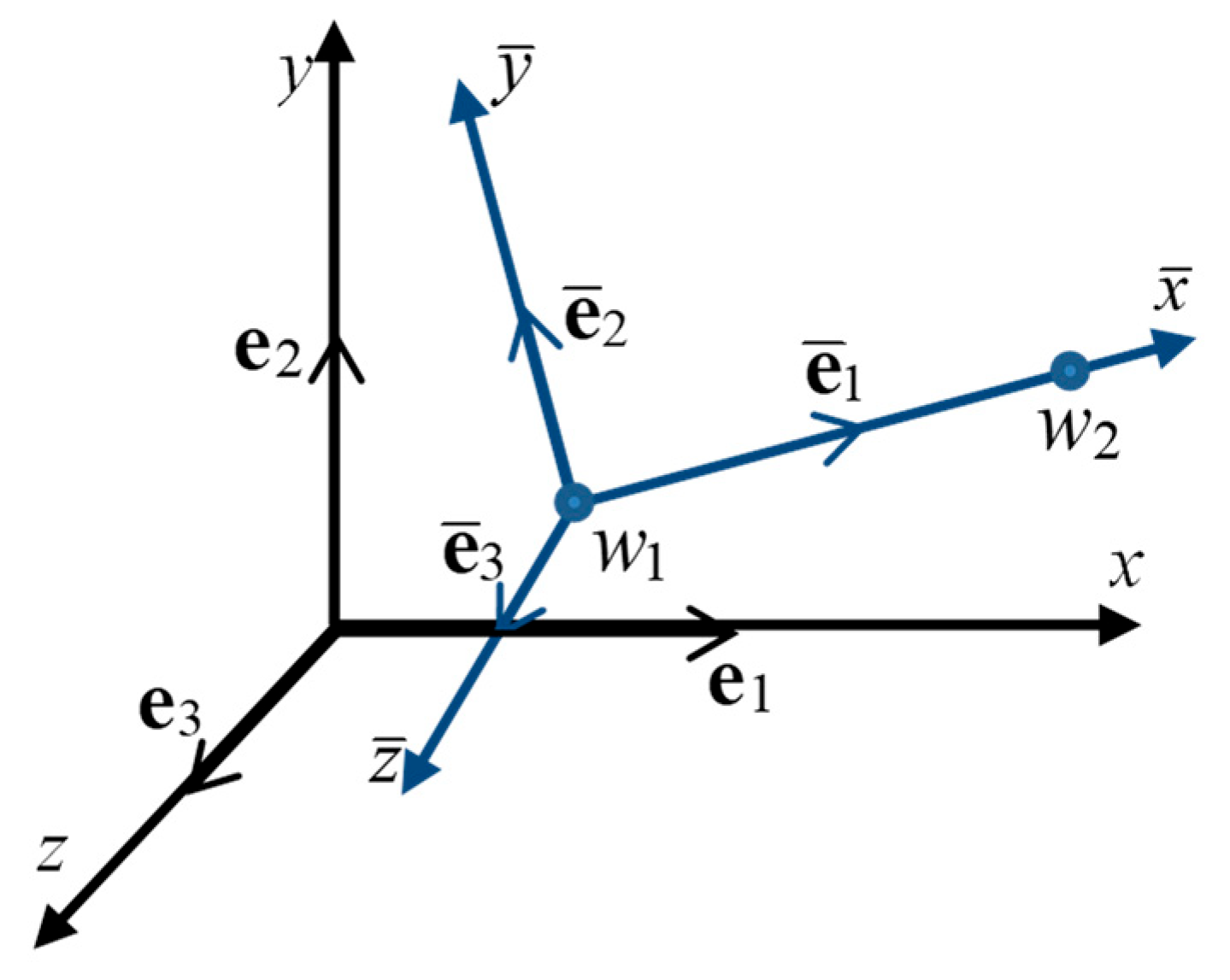

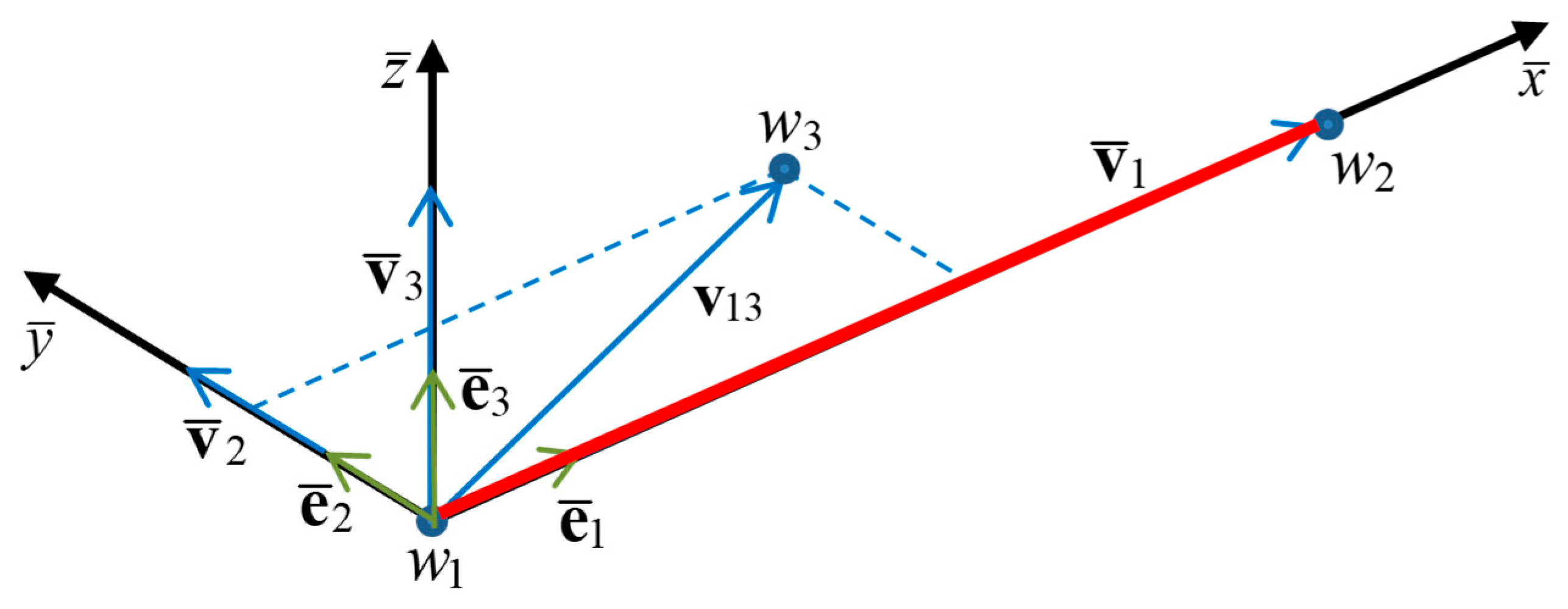

2.2. Description of a Spatial Truss Finite Element

2.3. Sensitivity Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

- location of concentrated load—describes the load application scenario for the structural model; each load Set (A–F) corresponds to a specific pattern of concentrated loads applied to selected nodes of the structure,

- Pult ultimate load—the magnitude of the load or total applied force at which the structure reaches the ultimate limit state associated with snap-through instability,

- the percentage error relative to load Set A,

- the displacement of the apex (top) node at the instant when snap-through instability occurs,

- the number of structural nodes to which concentrated loads are applied in the given load case,

- the total applied load acting in the considered load case at the moment when snap-through occurs. It depends on the number and distribution of loaded nodes.

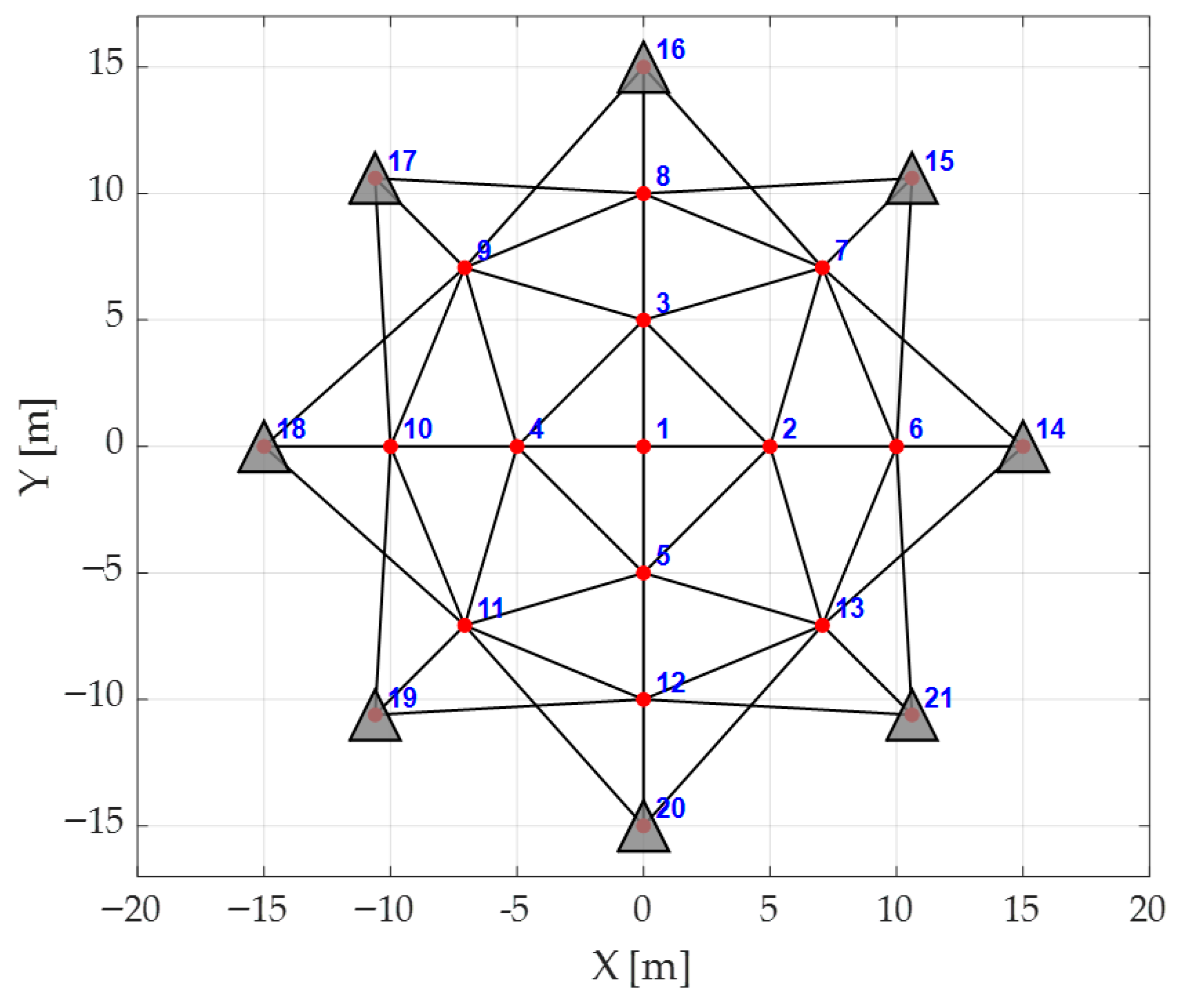

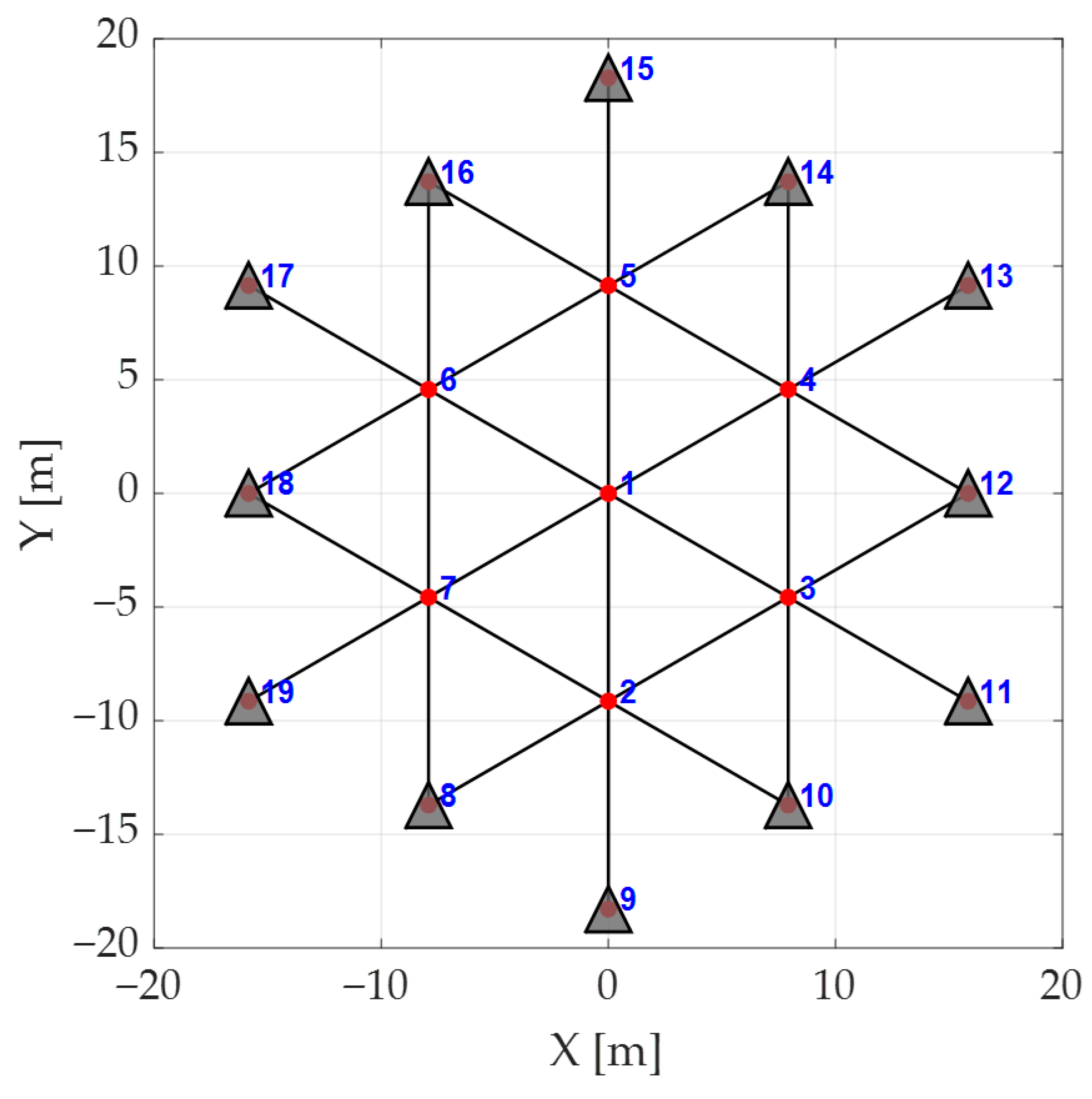

3.1. Description of Analyzed Structures

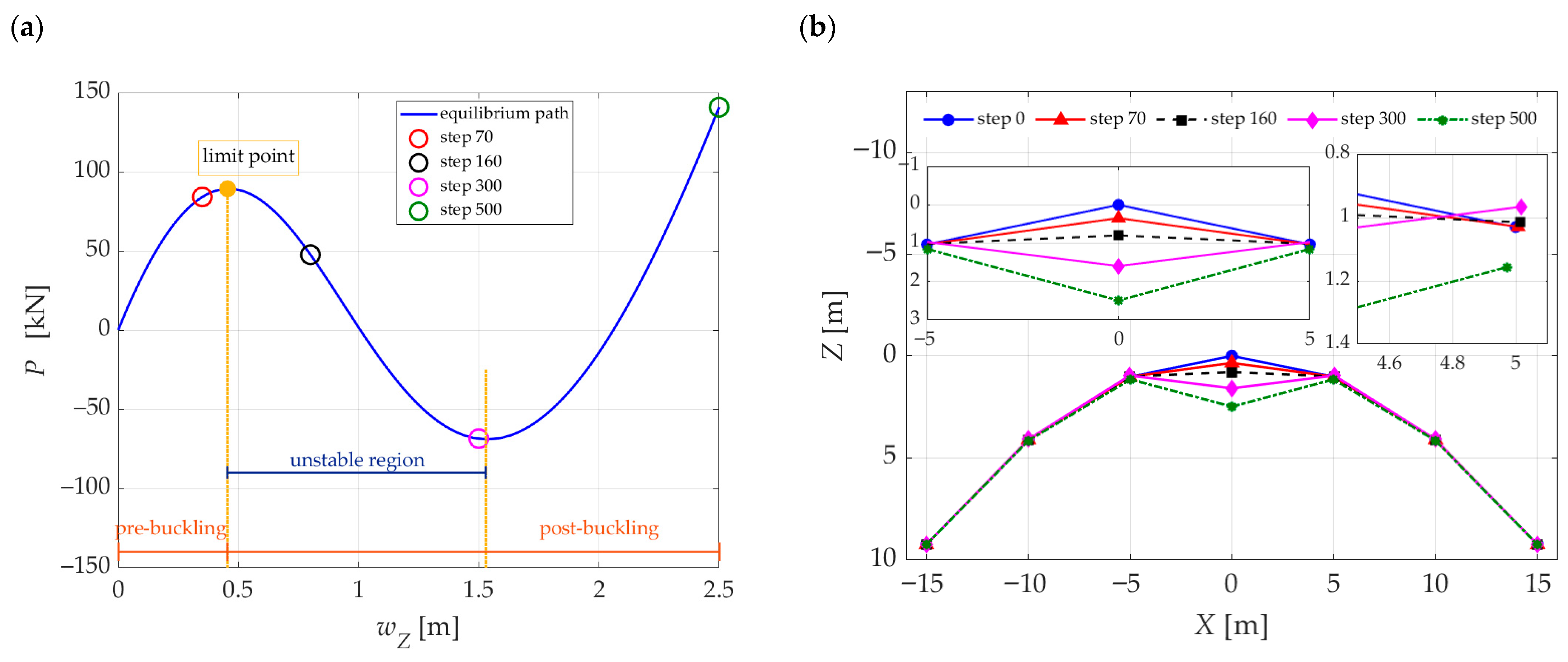

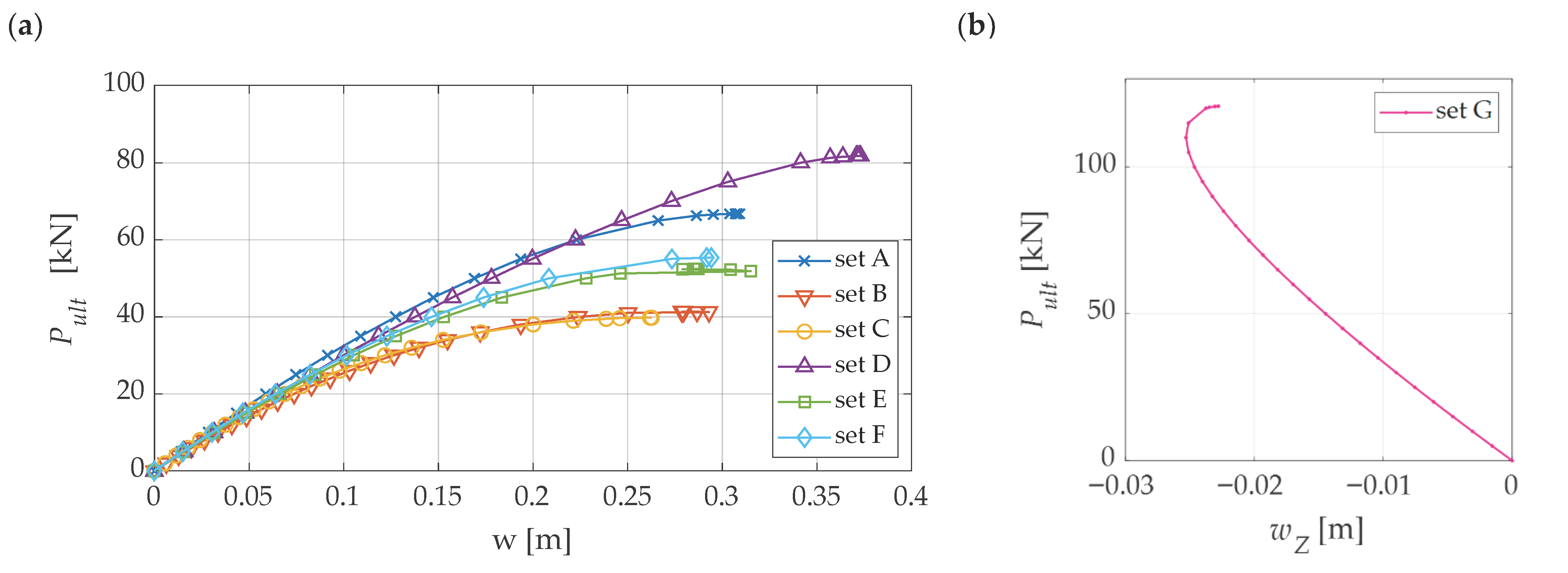

3.2. Analysis of the Stability-Loss Mechanism for Case 1: Local Snap-Through of the Apex Node

3.3. Results of the Stability Assessment

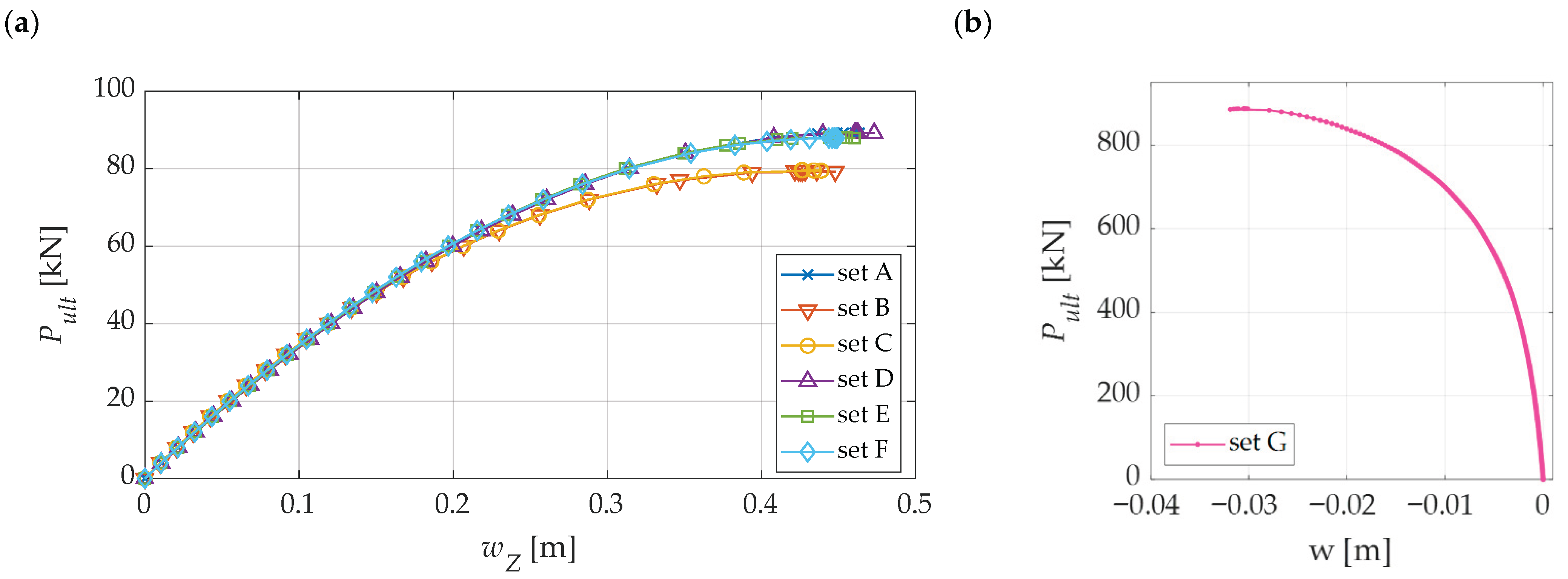

3.3.1. Case 1

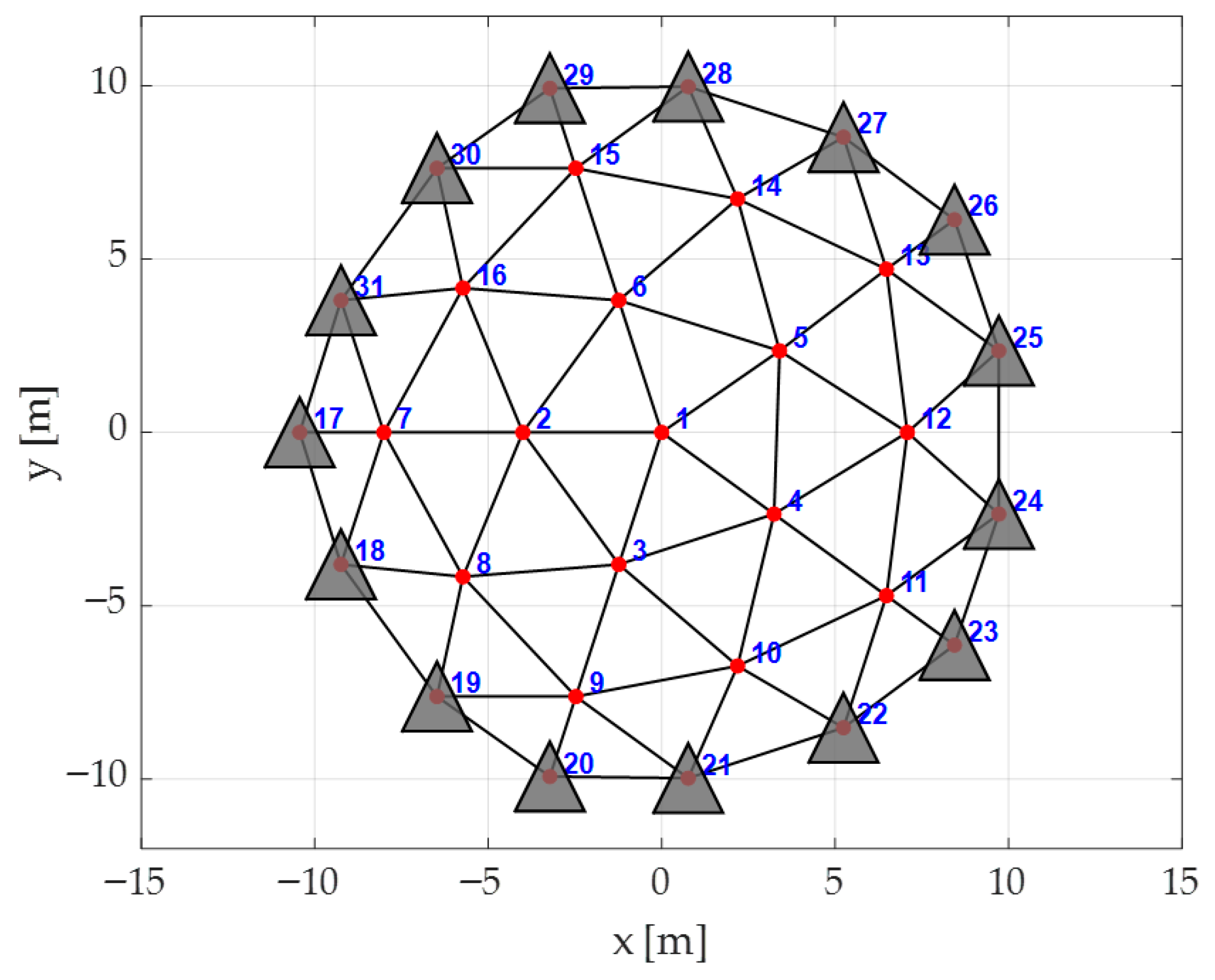

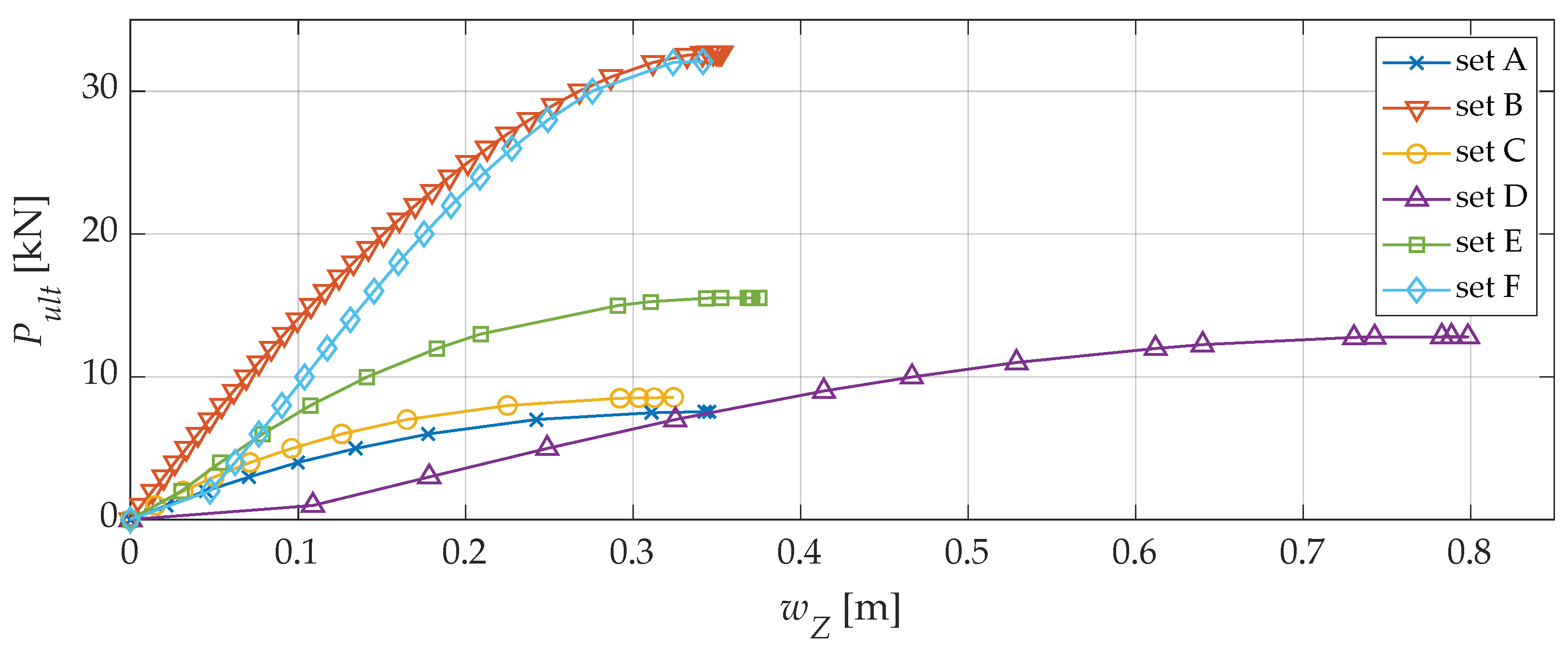

3.3.2. Case 2

3.3.3. Case 3

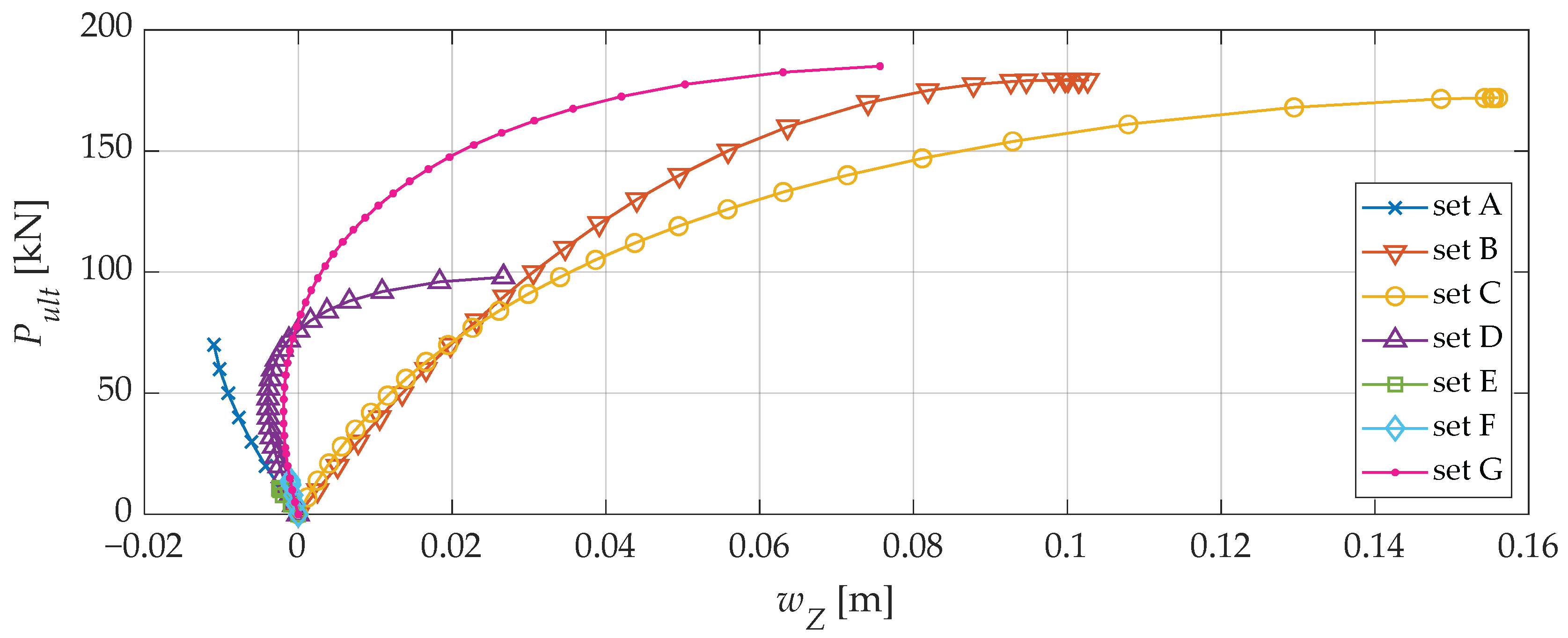

3.3.4. Case 4

4. Conclusions

- The analysis of different configurations of concentrated load arrangements showed that, despite significant differences in the critical force , the global response of the structure at the moment of snap-through remains similar.

- The structures where the ratio of the rise (H) to the span (L) (the horizontal distance covered) is H/L ≪ 0.2 (Case 3 and Case 4) exhibit greater sensitivity to changes in load location than snap-through susceptible domes with a ratio H/L > 0.2 (Case 1 and Case 2).

- The displacement of the apex node (Node 1) at the moment of snap-through remains similar across most of the proposed load sets, which confirms that this mechanism is primarily determined by the system’s geometry and, to a lesser extent, by the local concentration of forces.

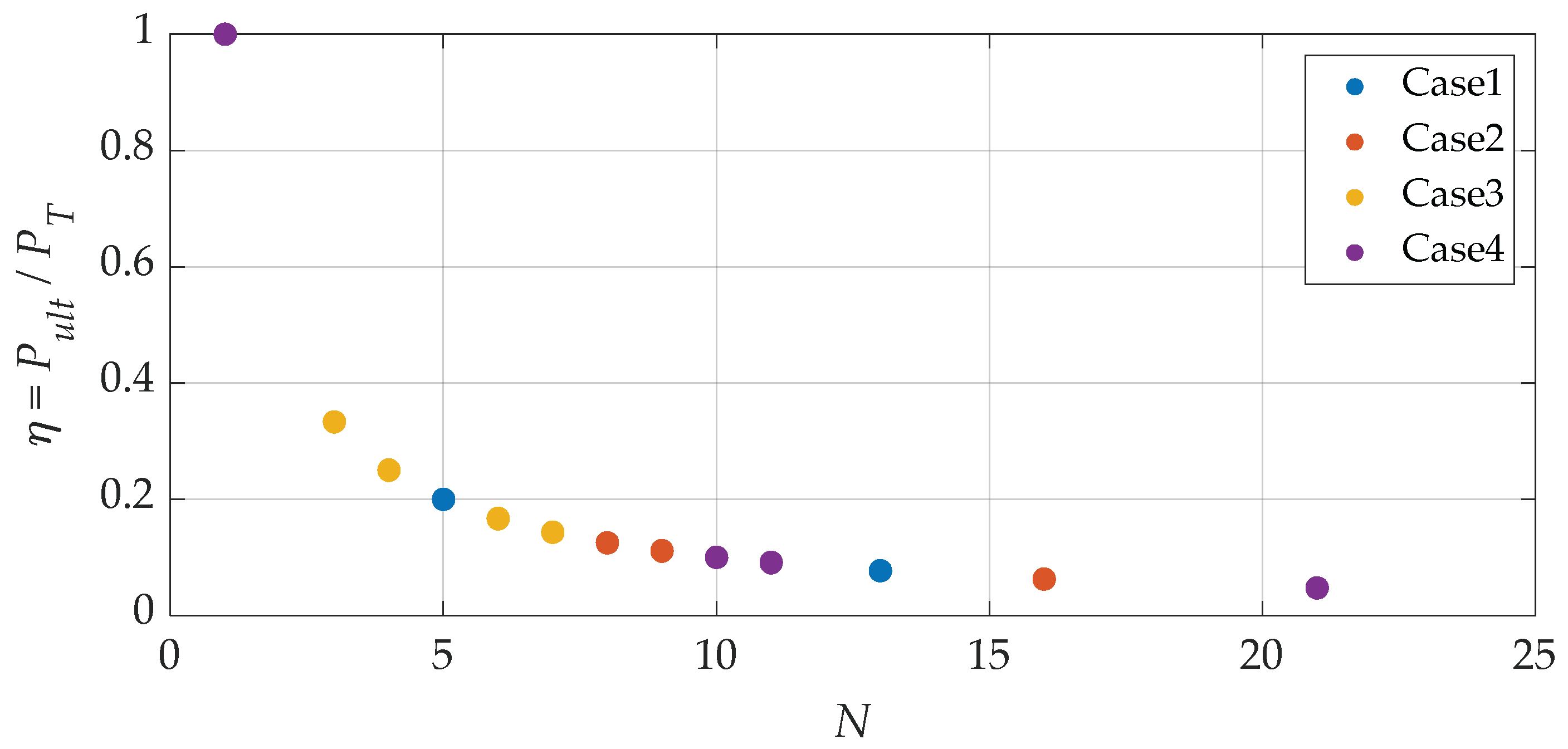

- The sensitivity analysis showed that the dimensionless parameter η (defined as the ratio of the total load applied to the nodes to the critical load ) decreases as the number of loaded nodes increases. It was also observed that this does not cause significant changes in the global characteristics of the snap-through phenomenon.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| FE | Finite Element |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NR | Newton–Raphson Algorithm |

| FORM | First Order Reliability Method |

| SORM | Second Order Reliability Method |

References

- Koiter, W.T. Over de Stabiliteit van Het Elastisch Evenwicht. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Delft, Delft, The Netherlands, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Mises, R.V.; Ratzersdorfer, J. Die Knicksicherheit von Fachwerken. ZAMM-J. Appl. Math. Mech./Z. Für Angew. Math. Und Mech. 1925, 5, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, K.J.; Cimento, A.P. Some Practical Procedures for the Solution of Nonlinear Finite Element Equations. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1980, 22, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, K.J. Finite Element Procedure in Engineering Analysis; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Belytschko, T.; Liu, W.K.; Moran, B.; Elkhodary, K. Nonlinear Finite Elements for Continua and Structures, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-63270-3. [Google Scholar]

- Crisfield, M.A. Non-Linear Finite Element Analysis of Solids and Structures, Volume 2: Advanced Topics; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- de Borst, R.; Crisfield, M.A.; Remmers, J.J.C.; Verhoosel, C.V. Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis of Solids and Structures, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-66644-9. [Google Scholar]

- Saffari, H.; Mansouri, I. Non-Linear Analysis of Structures Using Two-Point Method. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2011, 46, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari, H.; Mirzai Nadia, M.; Mansouri, I.; Bagheripour Mohammad, H. Efficient Numerical Method in Second-Order Inelastic Analysis of Space Trusses. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2013, 27, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Ji, J. Nonlinear Stability Analysis for Schwedler Reticulated Dome. In Applied Mechanics and Mechatronics Automation; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Baech, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 182, pp. 1609–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaiee-Pajand, M.; Salehi-Ahmadabad, M.; Ghalishooyan, M. Structural Geometrical Nonlinear Analysis by Displacement Increment. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 15, 633–653. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Groh, R.M.J.; Schenk, M.; Pirrera, A. Experimental Path-Following of Equilibria Using Newton’s Method. Part II: Applications and Outlook. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2021, 213, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Virgin, L.N.; Helm, D. Structural Behavior of Shallow Geodesic Lattice Domes. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2018, 155, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabojszcza, P.; Radoń, U. Experimental and Numerical Verification of the Influence of the Covering Height on the Shape of Equilibrium Paths. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T. Machine Learning for Structural Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review. Structures 2022, 38, 448–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.T.; Lieu, Q.X.; Kang, J.; Lee, J. A Robust Unsupervised Neural Network Framework for Geometrically Nonlinear Analysis of Inelastic Truss Structures. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 107, 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, F.; Marinković, M. PINN Surrogate Model for Nonlinear Equilibrium Path Analysis of von Mises Shallow Truss. J. Big Data 2025, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.T.; Lee, S.; Kang, J.; Lee, J. A Damage-Informed Neural Network Framework for Structural Damage Identification. Comput. Struct. 2024, 292, 107232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, V.; Pantὸ, B.; Nicosia, G. Adaptive Search Space Decomposition Method for Pre- and Post-Buckling Analyses of Space Truss Structures. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 117, 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzik, A.; Potrzeszcz-Sut, B. Hybrid Approach to the First Order Reliability Method in the Reliability Analysis of a Spatial Structure. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzik, A.; Potrzeszcz-Sut, B. The Structural Reliability Analysis Using Explicit Neural State Functions. In Proceedings of the 64 Scientific Conference of the Committee for Civil Engineering of the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Science Committee of the Polish Association of Civil Engineers (PZITB) (KRYNICA 2018), Krynica-Zdrój, Poland, 16–20 September 2018; Volume 262. [Google Scholar]

- Potrzeszcz-Sut, B.; Dudzik, A.; Kossakowski, P.G. Quantitative Assessment of the Reliability Index in the Safety Analysis of Spatial Truss Domes. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoń, U.; Zabojszcza, P. Stability Analysis of the Single-Layer Dome in Probabilistic Description by the Monte Carlo Method. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2020, 58, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrinda, G. Snap-Through Instability Patterns in Truss Structures; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gawade, S. The Newton-Raphson Method: A Detailed Analysis. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakowski, G.; Kacprzyk, Z. Metoda Elementów Skończonych w Mechanice Konstrukcji; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Warszawskiej: Warsaw, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, O.C.; Taylor, R.L. The Finite Element Method, 6th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 0-7506-6320-0. [Google Scholar]

- Iwicki, P. Sensitivity Analysis of Buckling Loads of Bisymmetric I-Section Columns with Bracing Elements. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2010, 56, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, E.; Schwiezerhof, K.; Vielsack, P. Measures to judge the sensitivity of thin-walled shells concerning stability under different loading conditions. Comput. Mech. 2006, 37, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsaki, M. Design Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization for Nonlinear Buckling of Finite-Dimensional Elastic Conservative Structures. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2005, 194, 3331–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguri, A.; Magisano, D.; Jankowski, R. Gradient-Based Weight Minimization of Nonlinear Truss Structures with Displacement, Stress, and Stability Constraints. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2025, 126, e70096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoń, U. Zastosowanie Metody FORM w Analizie Niezawodności Konstrukcji Kratowych Podatnych Na Przeskok; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Świętokrzyskiej: Kielce, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dudzik, A.; Radoń, U. The Evaluation of Algorithms for Determination of the Reliability Index. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2015, LXI, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaut, R. Snap-through of Shallow Reticulated Domes under Unilateral Displacement Control. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2017, 148–149, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Span (X) [m] | 30 | 20.15 | 31.68 | 30.00 |

| Width (Y) [m] | 30 | 19.94 | 36.57 | 28.54 |

| Height (Z) [m] | 9.25 | 6.45 | 2.18 | 1.49 |

| Z/X | 0.308 | 0.320 | 0.069 | 0.050 |

| Z/Y | 0.308 | 0.323 | 0.060 | 0.052 |

| Number of nodes | 21 | 31 | 19 | 61 |

| Number of bars | 52 | 75 | 30 | 150 |

| Material, E [GPa] | 69 | 210 | 69 | 210 |

| Cross-sectional area A [cm2] | 2.10, 18.50, 7.50 | 6.66 | 11.20, 9.06, 1.82 | 43.23 |

| Node Location of Concentrated Load | Pult [kN] | err [%] | wZ [m] | N | PT [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set A: All internal nodes | 89.21 | 0 | 0.44 | 13 | 1159.73 |

| Set B: 1 | 79.40 | 11.00 | 0.43 | 1 | 79.40 |

| Set C: 1, 6–13 | 79.54 | 10.85 | 0.43 | 9 | 715.86 |

| Set D: 1, 2–5 | 89.18 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 5 | 445.90 |

| Set E: 1, 2, 4, 9, 7, 11, 13 | 87.98 | 1.38 | 0.44 | 7 | 615.86 |

| Set F: 1, 3–5, 8–12 | 87.89 | 1.48 | 0.45 | 9 | 791.01 |

| Set G: 6–13 | 887.98 | - | -0.03 | 8 | - |

| Node Location of Concentrated Load | Pult [kN] | err [%] | wZ [m] | N | PT [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set A: All internal nodes | 66.74 | 0 | 0.309 | 16 | 1067.84 |

| Set B: 1 | 41.13 | 38.38 | 0.278 | 1 | 41.13 |

| Set C: 1, 7–16 | 39.97 | 40.10 | 0.263 | 11 | 439.67 |

| Set D: 1, 2–6 | 81.17 | 21.60 | 0.373 | 6 | 487.02 |

| Set E: 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 | 52.39 | 21.50 | 0.275 | 8 | 418.12 |

| Set F: 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 15, 16 | 55.32 | 17.10 | 0.294 | 9 | 497.88 |

| Set G: 7–16 | no snap: last step load = 120.70 kN | ||||

| Node Location of Concentrated Load | Pult [kN] | err [%] | wZ [m] | N | PT [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set A: All internal nodes | 7.65 | 0 | 0.346 | 7 | 53.55 |

| Set B: 1 | 32.68 | 76.59 | 0.352 | 1 | 32.68 |

| Set C: 2–7 | 8.55 | 11.76 | 0.324 | 6 | 51.30 |

| Set D: 1, 3, 5, 7 | 12.81 | 40.59 | 0.811 | 4 | 51.24 |

| Set E: 2, 4, 6 | 13.15 | 41.82 | 0.589 | 3 | 39.45 |

| Set F: 6 | 32.06 | 76.14 | 0.342 | 1 | 32.06 |

| Node Location of Concentrated Load | Pult [kN] | err [%] | wZ [m] | N | PT [kN] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set A: All internal nodes | no snap: last step load = 70 kN | ||||

| Set B: 1 | 179.36 | 0 | 0.099 | 1 | 179.36 |

| Set C: 1, 12–31 | 171.98 | 4.29 | 0.156 | 21 | 3611.58 |

| Set D: 1, 2–11 | 98.00 | 83.02 | 0.026 | 11 | 1078.00 |

| Set E: All odd nodes | no snap: last step load = 11.01 kN | ||||

| Set F: 1, 2–8, 14–16 | no snap: last step load = 14.19 kN | ||||

| Set G: 12–31 | 185.00 | 3.13 | 0.077 | 20 | 3700 |

| Case1 | Case2 | Case3 | Case4 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set | A | B | C | D | E | F | A | B | C | D | E | F | A | B | C | D | E | F | B | C | D | G |

| N | 13 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 11 | 10 |

| η | 0.077 | 1.000 | 0.111 | 0.200 | 0.143 | 0.111 | 0.063 | 1.000 | 0.091 | 0.167 | 0.125 | 0.111 | 0.143 | 1.000 | 0.167 | 0.250 | 0.333 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.048 | 0.091 | 0.100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dudzik, A.; Potrzeszcz-Sut, B.; Grzyb, M. Assessment of Equilibrium Path Sensitivity in Truss Domes Vulnerable to Node Snap-Through with Respect to Load Distribution. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010128

Dudzik A, Potrzeszcz-Sut B, Grzyb M. Assessment of Equilibrium Path Sensitivity in Truss Domes Vulnerable to Node Snap-Through with Respect to Load Distribution. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleDudzik, Agnieszka, Beata Potrzeszcz-Sut, and Marta Grzyb. 2026. "Assessment of Equilibrium Path Sensitivity in Truss Domes Vulnerable to Node Snap-Through with Respect to Load Distribution" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010128

APA StyleDudzik, A., Potrzeszcz-Sut, B., & Grzyb, M. (2026). Assessment of Equilibrium Path Sensitivity in Truss Domes Vulnerable to Node Snap-Through with Respect to Load Distribution. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010128