Electromagnetic Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge: Physicochemical Changes and Leachability Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Physicochemical Analysis of the Water Treatment Sludge

2.2. Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge

2.3. Metal Analysis of the Sludge and Water Extracts

3. Results

3.1. Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge

3.1.1. Effect of Disintegration on Settling Properties of the Sludge (Settleability)

3.1.2. Effect of Disintegration on the CST Value

3.1.3. Effect of Disintegration on pH Value

3.1.4. Effect of Disintegration on the COD Value

3.1.5. The Disintegration Degree of Water-Treated Sludge After Microwave Disintegration

- DD—degree of disintegration according to Müller [%];

- COD1—supernatant COD of the disintegrated sludge [mg O2/L];

- COD2—supernatant COD of the undisintegrated sludge [mg O2/L];

- COD3—the maximum COD release in the supernatant after chemical disintegration (0.5 M NaOH, ratio of 1:1 for 22 h at 20 °C).

| Microwave Power [W] | Microwave Irradiation Time [s] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | 210 | 240 | 270 | 300 | |

| 180 W | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 5.4 | 6.3 |

| 360 W | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5.9 | 6.5 |

| 540 W | 0.0 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 9.3 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 13.4 |

| 720 W | 0.3 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 8.0 | 9.6 | 12.0 | 12.8 | 14.3 | 13.4 |

| 900 W | 1.2 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 12.1 | 13.0 | ||

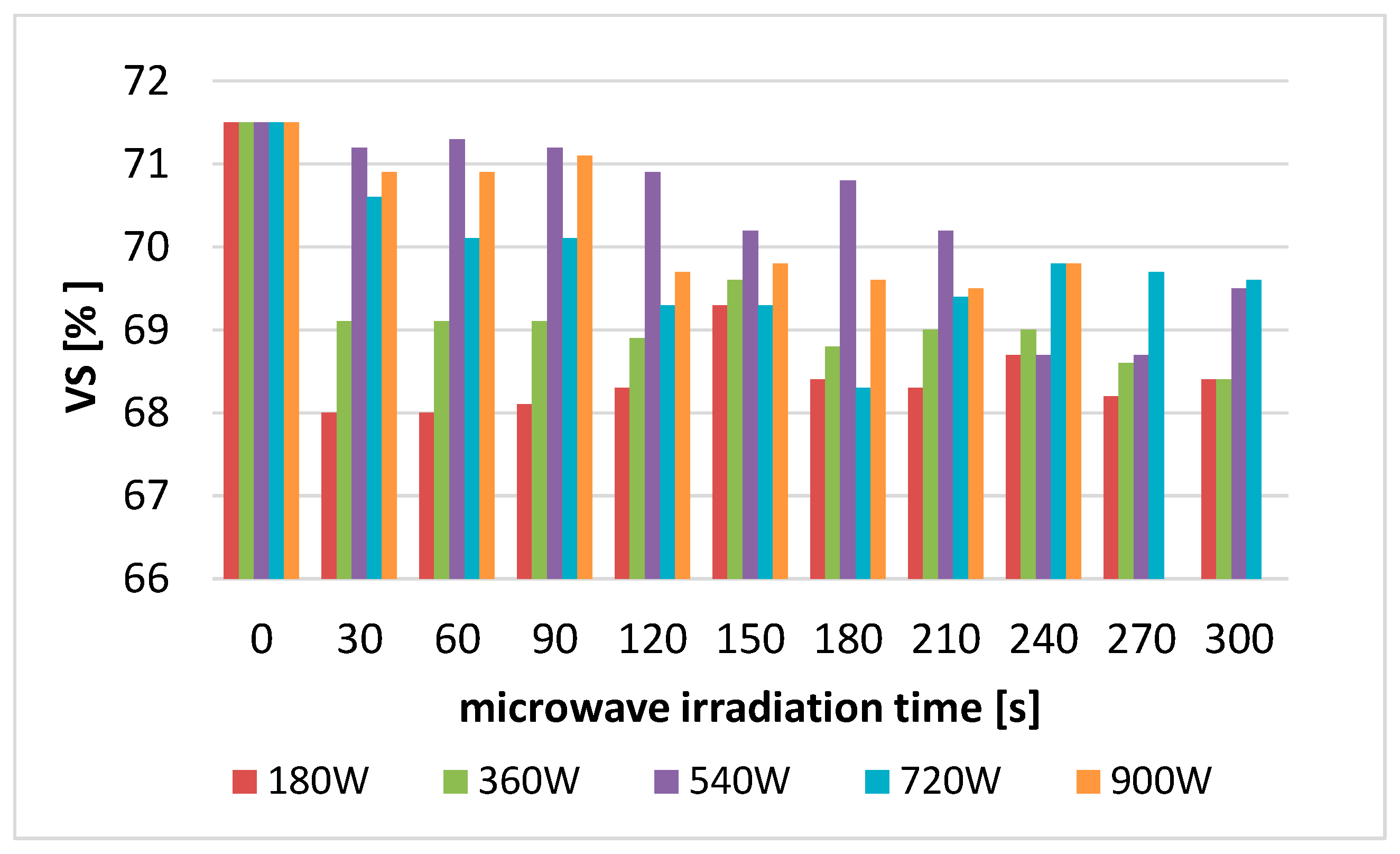

3.1.6. Effect of Disintegration on the TS and VS Values

3.1.7. Microscopy Images of the Water Treatment Sludge

- Microwave power = 180 W and t = 270 s;

- Microwave power = 360 W and t = 270 s;

- Microwave power = 540 W and t = 180 s;

- Microwave power = 900 W and t = 150 s.

3.2. Metal Concentrations in the Sludge Liquid

- Microwave power = 180 W and t = 270 s;

- Microwave power = 360 W and t = 270 s;

- Microwave power = 540 W and t = 180 s;

- Microwave power = 900 W and t = 150 s.

3.3. Metal Concentrations in the Water Extract

- Microwave power = 180 W and t = 270 s;

- Microwave power = 360 W and t = 270 s;

- Microwave power = 540 W and t = 180 s;

- Microwave power = 720 W and t = 150 s;

- Microwave power = 900 W and t = 150 s.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mañosa, J.; Formosa, J.; Giro-Paloma, J.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Quina, M.J.; Chimenos, J.M. Valorisation of Water Treatment Sludge for Lightweight Aggregate Production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Ahmad, K.; Ahad, A.; Alam, M. Characterization of Water Treatment Sludge and Its Reuse as Coagulant. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony, M.A. Valorization of Undervalued Aluminum-Based Waterworks Sludge Waste for the Science of “The 5 Rs’ Criteria”. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.T.; Ahammed, M.M. The Reuse of Water Treatment Sludge as a Coagulant for Post-Treatment of UASB Reactor Treating Urban Wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płonka, I.; Adamkowska, M. Application of Ultrasonic Disintegration of Post-Coagulation Sludge Zastosowanie Dezintegracji Ultradźwiękowej Dla Osadu Pokoagulacyjnego. Instal 2024, 2, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shamaki, M.; Adu-Amankwah, S.; Black, L. Reuse of UK Alum Water Treatment Sludge in Cement-Based Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 275, 122047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Liu, S.; Meng, X. Arsenic Leachability and Speciation in Cement Immobilized Water Treatment Sludge. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho Gomes, S.; Zhou, J.L.; Zeng, X.; Long, G. Water Treatment Sludge Conversion to Biochar as Cementitious Material in Cement Composite. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 306, 114463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwane, Q.I.; Tshangana, C.S.; Mahlangu, O.T.; Snyman, L.W.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Muleja, A.A. Hierarchical Approach to the Management of Drinking Water Sludge Generated from Alum-Based Treatment Processes. Processes 2024, 12, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuldeyev, E.; Ospanov, K.; Andraka, D.; Merkýreva, S. Experimental Study on the Application of Sludge from Water Treatment Plant as a Reagent for Phosphate Removal from Wastewater. Water 2023, 15, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pająk, M. Alum Sludge as an Adsorbent for Inorganic and Organic Pollutants Removal from Aqueous Solutions: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 10953–10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Lyczko, N.; Zhao, Y.; Nzihou, A. Alum Sludge as an Efficient Sorbent for Hydrogen Sulfide Removal: Experimental, Mechanisms and Modeling Studies. Chemosphere 2020, 248, 126010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Li, X.; Yan, H.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Lian, K. Recycling of Sludge Residue as a Coagulant for Phosphorus Removal from Aqueous Solutions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, M.; Afify, H.; Abdelfattah, A. Chemically Enhanced Primary Treatment of Sewage Using the Recovered Alum from Water Treatment Sludge in a Model of Hydraulic Clari-Flocculator. J. Water Process Eng. 2017, 19, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawal, N.B.M.; Razali, N.A.; Hairom, N.H.H.; Yatim, N.I.I.; Rasit, N.; Harun, M.H.C.; Kasan, N.; Hamzah, S. Parametric Study of Coagulant Recovery from Water Treatment Sludge towards Water Circular Economy. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 3142–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieczykolan, B. Investigation of Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherms of Synthetic Dyes on Biochar Derived from Post-Coagulation Sludge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bułkowska, K.; Zielińska, M. Thermal Disintegration of Waste-Activated Sludge. Energies 2024, 17, 4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhao, T.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L. New Strategies and Mechanisms for Enhancing Sludge Disintegration Using Waste Heat-Enhanced Circulating Fluidisation Method. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.; Capannelli, G.; Comite, A. Effect of Different Pretreatments on Sludge Solubilization and Estimation of Bioenergy Potential. Processes 2021, 9, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlicka, A.; Umiejewska, K.; Nielsen, P.H.; Muszyński, A. Hydrodynamic Disintegration of Thickened Excess Sludge and Maize Silage to Intensify Methane Production: Energy Effect and Impact on Microbial Communities. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 376, 128829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jery, A.; Kosarirad, H.; Taheri, N.; Bagheri, M.; Aldrdery, M.; Elkhaleefa, A.; Wang, C.; Sammen, S.S. An Application of Ultrasonic Waves in the Pretreatment of Biological Sludge in Urban Sewage and Proposing an Artificial Neural Network Predictive Model of Concentration. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S.; Rajesh Banu, J.; Vinoth Kumar, J.; Rajkumar, M. Improving the Biogas Production Performance of Municipal Waste Activated Sludge via Disperser Induced Microwave Disintegration. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 217, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, T.M.M.; Kavitha, S.; Ravi, Y.K.; Banu, J.R.; Adishkumar, S. Impact of Exopolymeric Substance Removal on Microwave Disintegration of Waste Activated Sludge for Enhanced Biohydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 145, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Ping, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Comparison of Different Sewage Sludge Pretreatment Technologies for Improving Sludge Solubilization and Anaerobic Digestion Efficiency: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.; Siles, J.A.; Martin, M.A.; Chica, A.F.; Estevez-Pastor, F.S.; Toro-Baptista, E. Effect of Microwave Pretreatment on Semi-Continuous Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge. Renew. Energy 2018, 115, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenezer, A.V.; Kaliappan, S.; Kumar, S.A.; Yeom, I.; Banu, J.R. Bioresource Technology Influence of Deflocculation on Microwave Disintegration and Anaerobic Biodegradability of Waste Activated Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 185, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Y.C.; Lafaille, R.; Lu, D.; Zhang, X.; Giles, R.; Apul, G. Bioresource Technology Reports Effects of Carbonaceous Susceptors on Microwave Pretreatment of Waste Activated Sludge and Subsequent Anaerobic Digestion. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 13, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodom, P.; Aragón-Barroso, A.J.; Koledzi, E.K.; Segbeaya, K.; González-López, J.; Osorio, F. Microwave Treatment of Three Different Types of Sewage Sludge Based on Their Solar Drying Exposure Time: Effect on Microorganisms, Water Content and Agronomic Aspects. Water 2024, 16, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Y.C.; Apul, O.G. ScienceDirect Critical Review for Microwave Pretreatment of Waste-Activated Sludge Prior to Anaerobic Digestion. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaralleh, R.M.; Kennedy, K.; Delatolla, R. Microwave vs. Alkaline-Microwave Pretreatment for Enhancing Thickened Waste Activated Sludge and Fat, Oil, and Grease Solubilization, Degradation and Biogas Production. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 12880:2004; Characterization of Sludges—Determination of dry Residue and Water Content. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004; (Polish version).

- PN-EN 12879:2004; Characterization of Sludges—Determination of the Loss on Ignition of Dry Mass. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004; (Polish version).

- PN-EN 14701:2007; Characterization of Sludges—Filtration Properties—Part 1: Capillary Suction Time (CST). European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; (Polish version).

- ISO 15705:2002; Water Quality—Determination of the Chemical Oxygen Demand Index (ST-COD)—Small-Scale Sealed-Tube Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- PN-EN 12457-2:2006; Characterisation of Waste. Leaching. Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2006; (Polish version).

- PN-ISO 8288:2002; Water Quality—Determination of Cobalt, Nickel, Copper, Zinc, Cadmium and Lead—Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometric Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; (Polish version).

- Li, Y.; Campos, L.C.; Hu, Y. Microwave Pretreatment of Wastewater Sludge Technology—A Scientometric—Based Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 26432–26451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Xin, X.; Qiu, W.; Li, D.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J. Waste Sludge Disintegration, Methanogenesis and Final Disposal via Various Pretreatments: Comparison of Performance and Effectiveness. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2021, 8, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaja, A.; Szulżyk-cieplak, J.; Łagód, S.; Kuzioła, E. Recent Developments in the Application of Ultrasonication in Pre-Treatment of Municipal Sewage Sludge. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tytła, M. The Effects of Ultrasonic Disintegration as a Function of Waste Activated Sludge Characteristics and Technical Conditions of Conducting the Process—Comprehensive Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, S.; Alhraishawi, A. Improving the Energy Balance between Microwave Pretreatment and Anaerobic Digestion with Centrifuged Biosludge. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vialkova, E.; Obukhova, M.; Belova, L. Microwave Irradiation in Technologies of Wastewater and Wastewater Sludge Treatment: A Review. Water 2021, 13, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubel, K.; MacHnicka, A. Impact of Microwave Disintegration on Activated Sludge. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2011, 18, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Lei, H.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, K. Physical and Chemical Properties of Waste-Activated Sludge after Microwave Treatment. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2841–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawieja, I.; Wolyn, L. Wpływ Stopnia Dezintegracji Osadów Ściekowych Poddanych Alkalicznej Modyfikacji Na Wartość Jednostkowej Produkcji Biogazu. Inżyneria Ochr. Sr. 2014, 17, 503–512. [Google Scholar]

- Tytła, M.; Zielewicz, E. The Effect of Ultrasonic Disintegration Process Conditions on the Physicochemical Characteristics of Excess Sludge. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2016, 42, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Power [%] | Power [W] |

|---|---|

| 100 | 900 |

| 80 | 720 |

| 60 | 540 |

| 40 | 360 |

| 20 | 180 |

| CST Value [s] | Microwave Power [W] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 180 | 360 | 540 | 720 | 900 | 0 | |

| average | 33.07 | 29.51 | 28.66 | 23.06 | 25.72 | 29.11 |

| min | 30.33 | 22.14 | 20.93 | 19.96 | 22.66 | 28.08 |

| max | 34.62 | 37.39 | 31.62 | 29.47 | 27.34 | 29.51 |

| Parameter | Before Disintegration | After Disintegration Process | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 180 W 270 s | 360 W 270 s | 540 W 180 s | 900 W 150 s | ||

| K [mg/L] | 3.13 | 3.25 | 3.23 | 9.49 | 7.75 |

| Na [mg/L] | 8.68 | 13.02 | 13.10 | 12.36 | 11.78 |

| Cu [mg/L] | <0.02 | <0.02 | 0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 |

| Zn [mg/L] | <0.02 | <0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Ni [mg/L] | <0.02 | <0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Pb [mg/L] | <0.03 | 0.06 | <0.03 | 0.03 | <0.03 |

| Cd [mg/L] | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 |

| Parameter | Before Disintegration | After Disintegration Process | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 180 W 270 s | 360 W 270 s | 540 W 180 s | 720 W 150 s | 900 W 150 s | ||

| Ca [mg/L] | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 |

| K [mg/L] | 1.92 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 2.37 | 2.33 | 2.74 |

| Cu [mg/L] | <0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Zn [mg/L] | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Ni [mg/L] | <0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 | <0.02 |

| Pb [mg/L] | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 |

| Cd [mg/L] | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 | <0.04 |

| Cr [mg/L] | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Płonka, I.; Pieczykolan, B.; Thomas, M. Electromagnetic Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge: Physicochemical Changes and Leachability Assessment. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010110

Płonka I, Pieczykolan B, Thomas M. Electromagnetic Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge: Physicochemical Changes and Leachability Assessment. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010110

Chicago/Turabian StylePłonka, Izabela, Barbara Pieczykolan, and Maciej Thomas. 2026. "Electromagnetic Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge: Physicochemical Changes and Leachability Assessment" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010110

APA StylePłonka, I., Pieczykolan, B., & Thomas, M. (2026). Electromagnetic Disintegration of Water Treatment Sludge: Physicochemical Changes and Leachability Assessment. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010110