Abstract

This paper proposes a kinematic modeling method for robotic manipulators by extracting the modified Denavit–Hartenberg (MDH) parameters using line geometry. For single-branched manipulators, various joint axes can be represented as lines using Plücker coordinates. The forward kinematics is derived by performing the product of matrices which are the exponential maps lifted from two kinds of exponential coordinates using the MDH parameters. For extracting MDH parameters, line geometry systematically analyzes the following: (1) the closest point between a point and line, (2) the closest distance and twist angle between two lines, (3) the common perpendicular line and its intersection points, and (4) classifies line relationships into collinear, distant parallel, intersected, and skewed cases. For each case, five parameters including twist angle, closest distance, common perpendicular direction vector, and both feet on a common perpendicular line are sequentially computed as results of the line geometry block. Finally, the aforementioned line geometry blocks are utilized to extract the four MDH parameters according to their definitions. The effectiveness of the proposed algorithm is verified by four examples including a typical Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm (SCARA) robot and three different commercial manipulators.

1. Introduction

Kinematic modeling of articulated robots is commonly categorized into two approaches according to the number of parameters required to describe the relative motion between adjacent joint axes: screw-based and line-based formulations. The screw-based formulation employs six parameters, whereas the line-based counterpart needs four. Owing to its theoretical completeness, the screw framework has been widely adopted in robotics research [1,2,3,4]. In a screw-based model, the transformation of one link with respect to its predecessor is represented by an exponential map constructed from six exponential coordinates—three rotational and three linear components. Multiplying these exponential maps sequentially produces the forward kinematics of a single-branched manipulator and extends naturally to branched or closed-loop mechanisms.

When each joint axis is regarded as an infinite line, only four independent quantities—Plücker coordinates—are sufficient to describe its pose, because a line is invariant under self-rotation and self-translation. Consequently, line-based formulations require four parameters per axis. Although screw coordinates offer superior numerical robustness for calibration, the modified Denavit–Hartenberg (MDH) notation remains the interface in industrial robot controllers. Direct identification in the MDH, however, often suffers from convergence issues caused by the coupling inherent in its parameter structure [5]. To alleviate this limitation, the present study proposes a post-processing algorithm that converts screw-identified parameters into the MDH format. A concise comparison among the standard Product-of-Exponential (PoE) form, MDH notation, and the classical DH convention—including differences in parameter count, transformation dependencies, frame consistency, and automation suitability—is provided in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Among traditional kinematic conventions, the Denavit–Hartenberg (DH) notation remains the most widely adopted. Originally introduced by Denavit and Hartenberg, it expresses the relative transformation between successive frames with four scalar parameters [6,7]. Two variants have since emerged: the distal form [8] and the proximal form—also called the Modified DH (MDH) notation—[1,9,10]. This work adopts the proximal form because every parameter is referenced to the same coordinate frame, which simplifies implementation and numerical treatment [11,12,13,14]. Deriving MDH parameters, however, requires locating the common perpendicular between consecutive joint axes; line geometry therefore becomes an essential computational tool in our framework.

The studies most closely related to this work are those of Faria et al. [15] and Liu et al. [16]. Faria et al. extract line parameters by commanding axis-specific rotations and subsequently convert them to DH parameters, but their procedure requires user-defined joint-excitation trajectories for each axis during data acquisition and manual assignment of each frame’s x-axis. Liu et al. automate the extraction of conventional DH parameters, yet their method handles only revolute joints and is incompatible with the MDH formulation. The algorithm proposed in the present study overcomes all of these limitations: it requires no constrained excitation, supports both revolute and prismatic joints, and outputs parameters directly in the MDH notation.

Recent studies [17,18,19,20] have focused on kinematic parameter identification based on screw theory, typically performed with a robot equipped with sensors attached to a TCF for calibration. Although direct identification is not performed in this study, the proposed method can be subsequently applied to convert the identified screw-based parameters into an MDH representation. This allows for seamless integration with MDH-based kinematic modeling frameworks commonly used in industrial and simulation environments.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the exponential map using MDH parameters, the exponential coordinates using MDH, the joint twist, and the joint matrix. Section 3 analyzes the relationships between line and point and between two lines, finds the common perpendicular line and its feet, and finally lists up the important contents into the line geometry block. Section 4 proposes how to extract the MDH parameters using two consecutive line geometry blocks. Several examples are employed to verify the proposed method in Section 5, and finally we draw conclusions.

2. Exponential Map Using MDH

Since a joint connects the adjacent links, a single branched articulated robotic manipulator having N joints has links and an adjacent transformation is defined between a pair of adjacent links or joints. This adjacent transformation, a homogeneous transformation matrix, is described in terms of four MDH parameters. The last frame of the robot is called the tool coordinate frame (TCF) where robotic tasks are assigned. The forward kinematics of the robotic manipulator is expressed as:

where and denote ith generalized joint variables which can be one or two degrees-of-freedom (dof) according to the joint type, the prefixed superscript and postfixed subscript of the homogeneous transformation stand for the reference frame and target frame, respectively, e.g., represents the constant adjacent transformation from frame to .

2.1. MDH Parameters

The MDH notation describes the relationship between adjacent joint axes at zero-configuration which represents when every joint variable is zero. To define the four MDH parameters, the coordinate frames are determined according to the following procedures:

- 1.

- Set the -axis in the direction of the joint axis.

- 2.

- Define the -axis as the common perpendicular direction to the adjacent joint axes. In cases where adjacent axes are collinear, the previous -axis is retained as the current -axis.

- 3.

- Determine the -axis using the right-hand rule.

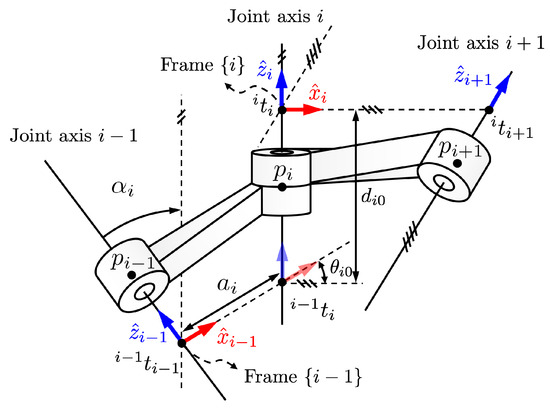

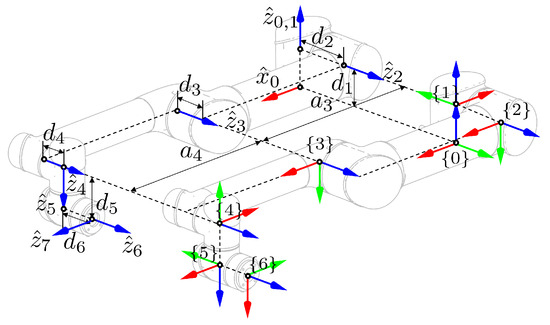

Figure 1 illustrates how to set up two coordinate frames and from three consecutive joint axes and . After setting up both coordinate frames, four MDH parameters are defined as follows:

Figure 1.

Modified Denavit–Hartenberg (MDH) parameters, where denotes the point on the th joint axis, the -axis is set along the th joint axis, the -axis is determined to be a common perpendicular direction from the -axis to the -axis, and the origin of the frame denoted by is an intersection point of the -axis and the -axis. Also, four MDH parameters are denoted as , , , and .

- 1.

- Link twist (): this parameter represents the angle from to about the -axis

- 2.

- Link length (): this denotes a distance from to along the -axis

- 3.

- Joint offset distance (): this is the distance from to along the -axis

- 4.

- Joint offset angle (): this expresses the angle from to about the -axis.

It is noted that three consecutive joint axes are required to define four MDH parameters, which are used to obtain the adjacent transformation between the frame and the frame . Figure 1 shows a typical example of MDH parameters. Note that the terms “joint offset distance” and “joint offset angle” correspond to the standard MDH parameters and , respectively. The subscript “0” is introduced to distinguish between constant geometric parameters and variable joint inputs (e.g., , ) and to clarify their role in generating the transformation matrix. Using the four constant MDH parameters, the adjacent transformation can be represented by adding joint variables for the revolute joint type and for the prismatic joint type. For this purpose, ith generalized joint variables and are defined differently according to the joint types as follows: where h implies a pitch to denote a moving distance along the joint axis per one revolution for the helical joint. It is noted that three consecutive joint axes are required to define four MDH parameters, which are used to obtain the adjacent transformation between the frame and the frame i, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The generalized joint variables with MDH parameters.

2.2. Exponential Map Using MDH

In this work, Lie group methods are employed to establish a connection between the Modified Denavit–Hartenberg (MDH) parameters and Lie algebra in the context of robot forward kinematics. For readers unfamiliar with the fundamentals of Lie groups and Lie algebras in robotic modeling, we recommend [3,4] as accessible introductions. For a more advanced treatment of Lie group integration and numerical methods, refer to [21]. In addition, screw theory, which underpins many geometric interpretations used here, is thoroughly discussed in [2]. The adjacent transformation from the coordinate frame to the frame in Figure 1 can be decomposed into two exponential maps because the link twist and the link length are represented with respect to the -axis and the generalized joint variables and with respect to the axis as follows:

where the matrix exponential, belonging to the Lie group , is defined by using the matrix , belonging to Lie algebra , as follows:

In other words, implies Lie algebra and is a Lie group lifted from the Lie algebra , where means the exponential coordinate vector. The series expansion of using Equation (2a) results in:

Since Lie algebra is isomorphic to a six-dimensional real vector , we can use it interchangeably

where and imply the linear and angular components of the exponential coordinate vector , respectively. Thus, we can find the exponential coordinates of MDH from Equations (2b) and (2c), respectively, as follows:

2.3. Joint Twist Using MDH

Since the exponential map (or adjacent transformation) of Equation (1) using MDH is obtained by the matrix product of Equations (3a) and (3b), the joint twist is derived from the left multiplication rule [21,22] as follows:

where implies the ith joint twist relative to the frame represented in the frame . It is noted that ith joint twist is represented in the frame . Now, we can define ith joint matrix by separating the time-derivative of joint variable from the joint twist as follows:

where because the joint offset distance and the joint offset angle as MDH parameters are constants. For given four joint types , each joint has its own joint matrix and time-derivative of joint variable as follows:

The joint matrix represented in the frame can be transformed into either the base frame or the tool coordinate frame ; for this purpose, the adjoint transformation is introduced as follows:

where and are called spatial screw and body screw in [4], respectively, and the adjoint transformation is defined by

using the homogeneous transformation , in which implies a three-dimensional rotation matrix, represents three-dimensional skew-symmetric matrix obtained from a three-dimensional displacement vector , and implies three-dimensional zero matrix. Till now, we have revealed how the MDH parameters influence the exponential map, the exponential coordinate vector, the joint twist, and the joint matrix. The next section will discuss the relationships between the joint axes using the line geometry, ultimately, to find the MDH parameters.

3. Line Geometry

A line can be represented by a set of three-dimensional direction vector and three-dimensional moment vector v, where and v are called the Plücker coordinate after Julius Plücker [23,24]. The Plücker coordinate to express the line has four independent elements because the line has two constraints that it remains the same line when rotated about itself and translated in its direction [25]. To improve readability and reduce the complexity of the main text, detailed derivations of the equations are provided in Appendix B.

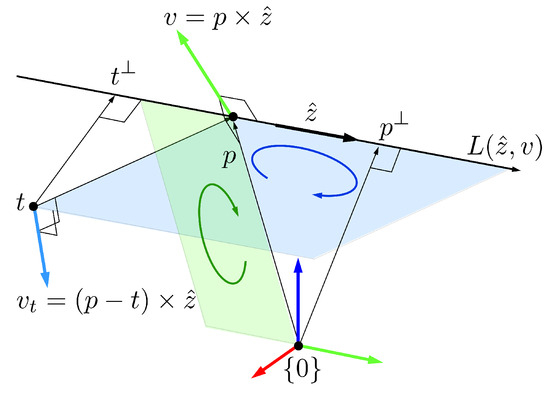

Here, is a unit vector to denote any direction in a three-dimensional space and is the moment of the line described from an arbitrary point p on the line represented in the frame as shown in Figure 2, which can be expressed as follows:

Figure 2.

Relationships between a line and a point p on the line, and between the line and a point t out of the line in three-dimensional space.

3.1. Relationships Between Line and Points

Since the moment vector v is orthogonal to by Equation (10), it provides information about the closest point from the origin of frame as shown in Figure 2. Namely, the closest point on the line L from the origin of frame is computed by

where the closest distance from the origin of frame to the line L is . Furthermore, the moment of the line L about an arbitrary point t out of the line in Figure 2 is defined by

and the closest point on the line L from a point t out of the line in Figure 2 is computed by

where it is represented in the frame , and the closest distance from an arbitrary point t out of the line to the line L is . It is interesting that the closest point on the line from a point t out of the line is obtained by taking the cross-product of the direction vector and the moment .

3.2. Relationships Between Two Lines

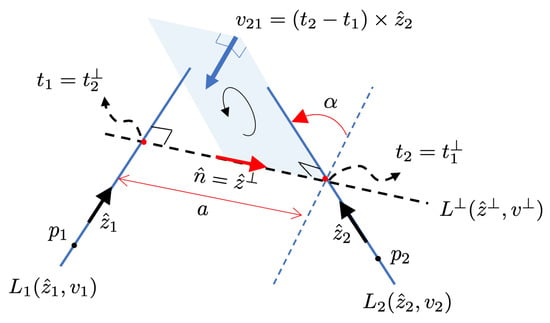

Another important property of the Plücker coordinate is the reciprocal product between two lines. When two lines are denoted as and , as shown in Figure 3, it is defined as follows:

where the reciprocal product implies the moment of line about line or the moment of about . It is interesting that the reciprocal product is independent of the location of on or on , and it is only dependent on the direction vectors and . In addition, the reciprocal product is scalar, not a vector. Let us denote the moment of the line about the point using Equation (12):

where and are feet of the common perpendicular line to the two lines and as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Relationships between two lines and , where a is the distance between two lines, and are feet of the common perpendicular line to two lines, and is the direction vector from to .

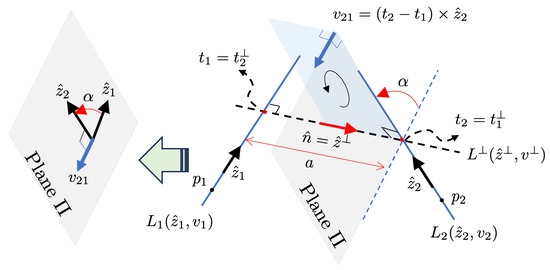

Let us define the plane containing and as shown in Figure 4, which is orthogonal to the common perpendicular line and parallel to . Consequently, the plane contains as shown in Figure 4. Using the fact that the link twist is the angle of rotation from to about the common perpendicular line, the reciprocal product can be recomputed as follows:

where implies the distance between and . Thus, it provides the information on the link length a in Figure 1 as follows:

Figure 4.

The plane contains and , which is orthogonal to the common perpendicular line and parallel to ; consequently, it contains as well, where implies the twist angle of rotation from to about the common perpendicular line, and is perpendicular to .

As a matter of fact, the reciprocal product becomes zero either when the two lines are intersected () or when the two lines are parallel (), where the link twist in Figure 1 is defined by the angle of rotation from to about the common perpendicular line, which is calculated as follows:

where it is effective for a positive range of . To cover its negative range of , the sign variable denoted by will be considered later.

3.3. Common Perpendicular Line

Let us find the common perpendicular line denoted by in Figure 4. Then, its direction vector emanating from is obtained as follows:

in fact, it is corresponding to the -axis required to express the MDH parameters in Figure 1, and the moment vector is computed by:

Since we have obtained the common perpendicular line, we are ready to derive two intersection points and in Figure 4, which are called feet of common perpendicular line, where the former is obtained as an intersection between and and the latter between and .

3.4. Feet of Common Perpendicular Line

The aforementioned intersection points (or feet) and in Figure 4 can be found through the following procedures. In fact, the related proof can be found in [25] as well. To begin with, let us set up a coordinate frame -- at the origin as shown in Figure 5, which is composed of three perpendicular unit vectors , , and . The basic idea in [25] is to project the point onto the coordinate frames -- in Figure 5 as follows:

Figure 5.

-- coordinate frame, where lies in the - plane, and thus and for .

For the third term () of the right-hand side of Equation (21), we can observe the following:

For the second term (), the definitions of and are used as follows:

For the first term , the direction vector lies in the plane spanned by and as shown in Figure 5, such that

then, using Equation (23), we have:

Also, from the following:

is obtained as:

Then using Equation (24), is derived using :

since appears in both sides of the above equation, rearranging it yields

By inserting the three terms of Equations (22), (23), and (25) into Equation (21), finally, we have , using and , as following form:

On the other hand, is obtained from Equation (26) for by switching subscripts 1 and 2, as follows:

3.5. Line Geometry Block,

The method to express how two adjacent lines (or joint axes) are located each other can be classified into four cases: collinear, distant parallel, intersected, and skewed. To begin with, criterion 1 is defined to check whether two lines are parallel or not, which is performed using the two direction vectors:

where denotes a small positive constant with units of radians, introduced to handle numerical issues when comparing angular values. If criterion 1 of Equation (25) is satisfied, the two lines are parallel to each other. The parallel lines can be further classified into two cases: collinear (parallel) and distant (parallel). For this purpose, criterion 2-1 is defined as the distance between the closest points from the origin of the coordinate frame to the lines using Equation (Section 3.1) as follows:

where

where is a small positive threshold with units of meters, introduced to ensure numerical robustness when comparing distances between points. If criterion 2-1 is satisfied, the two lines are collinear (parallel); otherwise, they are distant (parallel). These parallel cases are summarized in Figure 6.

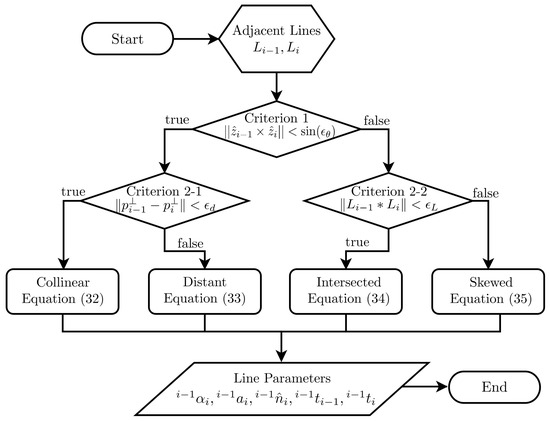

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the line geometry block . Given two input lines, and , the block uses two criteria to classify their relationship into one of the four cases: Collinear, Distant, Intersected, or Skewed. Based on the case, it returns five parameters: , , , , and .

On the other hand, if criterion 1 of Equation (27) is not satisfied, the two lines are not parallel to each other. The non-parallel lines can be further classified into two cases: intersected and skewed. For this purpose, criterion 2-2 is defined as the existence of the intersection point, which is conducted using the reciprocal product (Section 3.2):

where is a small positive threshold used to evaluate the reciprocal product. Note that unlike (in radians) and (in meters), the reciprocal product is inherently dimensionless. If criterion 2-2 of Equation (30) is satisfied, two lines are intersected at one point, otherwise, they are skewed.

The line geometry block to be designed in this section receives two lines () as inputs, selects one from the four cases using the criteria, and yields five parameters () as outputs, where it is noted that two lines as the inputs consist of the direction vectors of joint axes and the points on joint axes as follows:

3.5.1. Collinear

If and are satisfied, the two lines are collinear with the following five parameter descriptions:

where link twist can be either or . In fact, the two lines are either in the same direction () or in the opposite direction () according to the link twist value. In the collinear case, the common perpendicular direction -axis is not defined, and thus the -axis of the previous frame is identically assigned to the new frame.

3.5.2. Distant (Parallel)

If and are satisfied, the two lines are distant parallel to each other with the following five parameter descriptions:

where it is noted that when the two parallel lines are in the same direction and in the opposite direction. Additionally, the closest points on line and on line yield the link length a and the common perpendicular direction as follows:

In fact, is an arbitrary point on line , but we choose equal to for practical use. Then, since .

3.5.3. Intersected

If and are satisfied, the two lines are intersected at one point with the following five parameter descriptions:

where is a three-dimensional identity matrix. To find the intersection point, let us rearrange the second term of (27) using as follows:

where , then of Equation (27) is rewritten as follows:

Also, by using the property of cross-product operator, e.g., , we have

where the moments of the intersected lines are the same with each other, e.g., because .

3.5.4. Skewed

If and are satisfied, the two lines are skewed (not co-planar) with following the five parameters descriptions:

where the five results of line geometry such as link length a (17), link twist (18), -axis (19), and feet of common perpendicular line (26) and (27) are fully exploited for the skewed case.

The line geometry block denoted by summarizes the five parameters chosen according to criteria as shown in Figure 6, where the line geometry block is described by

where the inputs are two lines and the outputs are five parameters yielded from one of the four cases, which is selected using two criteria. As suggested in Figure 1, three joint axes (a set of three consecutive lines , and ) are required to extract four MDH parameters and thus two line geometry blocks are needed to describe four MDH parameters for ith joint.

4. Algorithmic MDH Parameter Extraction

This section describes how to algorithmically extract MDH parameters using the line geometry blocks suggested in the previous Section 3.5. This method can be directly applied to the single-branched articulated robotic manipulators. To extract a set of four MDH parameters for each joint, three consecutive lines (joint axes) are needed. Thus, line information is required with respect to the base frame including tcf denoted by for N-joint manipulators. Three coordinate axes of the base frame are defined by , and , respectively. Algorithm 1 summarizes the inputs and the outputs through the computations of intermediate variables. The inputs are listed as follows:

where . The adjacent two lines are applied consecutively to the line geometry blocks for ith joint as follows:

for .

To extract four MDH parameters, we need to define -axis to be the common perpendicular direction denoted by as shown in Figure 1. As a special case, the common perpendicular direction is not defined in the collinear case as suggested in Equations (32a)–(32d), and thus we assign the previous -axis to as follows:

where it is noted that the origin of frame is specified as . Once defining -axis through Equation (37), the sign of link twist and link length can be determined by using the dot-product between and . To begin with, the sign is assigned into when two lines are parallel. Subsequently, if , then the sign will be , and if , then the sign will be . As a summary, the sign is determined as follows:

The sign of the joint offset angle can be also determined by using the dot-product between and as follows:

where it is noted that the sign of joint offset distance does not have to be considered because it is obtained already by dot-product implying the projection onto the -axis. Using the signs of (38) and (39), four MDH parameters are determined in the following sections.

| Algorithm 1 Algorithmic MDH parameter extraction. |

|

4.1. Twist Angle

It is defined as the angle from to about -axis as shown in Figure 1. Since the twist angle provided from is in the range of , the sign should be reflected in the following form:

4.2. Link Length

It is defined as the distance from to along -axis as shown in Figure 1. Since the distance is positive, the sign is also reflected in the following form:

4.3. Joint Offset Distance

It is defined as the distance from to along the -axis as shown in Figure 1. The distance projected into -axis is defined as follows:

4.4. Joint Offset Angle

It is defined as the angle from to about the -axis as shown in Figure 1. Since the -axis is determined by Equation (37), the sign should be reflected as follows:

The outputs of Algorithm 1 are consecutively arranged into:

where it is noted that the -axis is required in advance and it is commonly chosen as . To verify the completeness of Algorithm 1, several examples are suggested in the following section.

The algorithm does not include any iterative procedures and is composed of fixed geometric operations such as dot products and cross products. The line geometry block contains no loops, and Algorithm 1 uses a single for-loop over N joints. The overall computational complexity is .

5. Verification

Algorithm 1 was implemented in both Python and MATLAB (The implementation for algorithmic DH parameter extraction is available at https://github.com/MinchangSung0223/AlgorithmicMDH (accessed on 27 April 2025)) and is also referenced in [26]. The algorithm was tested using PyBullet [27] and MATLAB simulations. For each joint i, the joint axis and a point on the axis were extracted from the URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) model [28]. The verification was first conducted on a simple SCARA robot, followed by testing on three commercial robotic manipulators, as described in the following sections. All verifications were conducted entirely in simulation without using the experimental hardware.

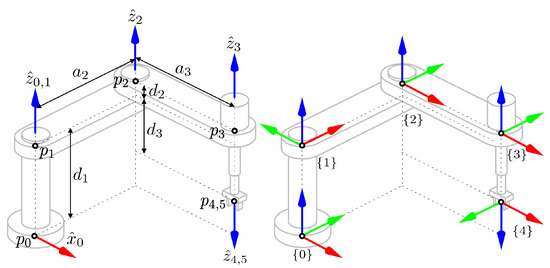

5.1. SCARA

A typical SCARA robot consists of three revolute joints and one prismatic joint, where the left side of Figure 7 shows the line information as inputs and the right side shows the extraction results of MDH parameters. For the first joint, the following three consecutive lines are applied to the Algorithm 1:

where for . The zeroth line and first line have a collinear relation, and the first line and second line have a distant parallel relation by the proposed criteria in Section 3.5 regarding the line geometry block . And finally, the outputs of Algorithm 1 regarding the first joint are listed as follows:

where these results make us to denote the frame in the right side of Figure 7. The aforementioned processes are repeated until the fourth joint. As a result, a pair of input and output data for all joints are listed in Table 2 and denoted on the right side of Figure 7. During the processes, the relations between the lines are found in Table 3.

Figure 7.

The SCARA robot example, where the left side shows six line information including the base and TCF and the right side illustrates the result of MDH parameters extracted using Algorithm 1, in which the red arrow denotes the -axis, the green arrow expresses the -axis, and the blue arrow represents the -axis, respectively. In addition, the circle ∘ on the left side denotes the point , and ∘ on the right side expresses the origin of the ith frame.

Table 2.

MDH parameters of the Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm (SCARA) robot extracted when inputs are -axis, on the ith joint axis, and its moments denoted by , where outputs of Algorithm 1 are obtained as a set of -axis, link twist , link length , joint offset distance , and joint offset angle for the ith joint. Additionally, and are both feet of the common perpendicular line.

Table 3.

Relations between adjacent joint axes computed from the SCARA model.

Using the constant MDH parameters suggested in Table 2, the adjacent transformation can be represented by adding joint variables for the first, second, and third revolute joints and for the fourth prismatic joint. The generalized joint variables for each joint are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The generalized joint variables with MDH parameters for the SCARA robot.

The forward kinematics can be obtained using the MDH parameters () about/along the -axis and the generalized joint variables () about/along the -axis as follows:

where implies and ith adjacent transformation belonging to is obtained as, for ,

in which the exponential coordinates and isomorphic to the Lie algebras and are described using Equation (4) and summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Exponential coordinates , , and joint matrices for SCARA robot joints.

Additionally, we can derive the joint twist represented by and the joint matrix as suggested in Section 2.3. Furthermore, the joint matrix represented in the base frame () and the joint matrix represented in the tool coordinate frame () can be obtained using the corresponding adjoint transformations and , respectively. Two types of joint matrices denoted by and are called spatial screw axes and body screw axes in [4], respectively.

5.2. SCARA with Modeling Uncertainties

In practical robotic systems, modeling uncertainties often lead to deviations in the direction and displacement vectors from their ideal values. Despite such deviations, the proposed algorithm is capable of robustly computing the MDH parameters from non-ideal inputs, provided that the joint axes are correctly defined as lines, as described in Section 3. In conventional approaches to kinematic modeling using MDH or DH parameterizations, the transformations from the base frame to the first joint frame and from the last joint frame to the tool coordinate frame are typically treated as known rigid transformations. If needed, they may be modeled with additional parameters and identified separately. In our method, it is also possible to estimate the MDH parameters associated with such rigid transformations by allocating additional virtual lines to represent them. However, because these transformations are typically fixed and known with high accuracy (e.g., derived from CAD models or mechanical assembly), our algorithm assumes them to be given and instead focuses on calibrating the internal joint transformations between successive links using the line geometry-based approach (see Algorithm 1). To evaluate the robustness of the proposed method, we introduced synthetic modeling uncertainties into a simple SCARA robot. Table 6 compares the nominal and perturbed (“actual”) joint parameters encoded in the URDF. Perturbations were applied to each joint with approximately deviation in orientation and m deviation in displacement, mimicking realistic sensor or modeling noise. Based on the perturbed URDF data in Table 6, the MDH parameters extracted using the proposed algorithm are listed in Table 7. Compared to the ideal case, the modeling uncertainties caused several joint axis pairs, previously identified as “distant” in line geometry, to be reclassified as “skewed”. As a result, the joint offset distances increased noticeably. The updated relationships between adjacent joint axes under perturbation are summarized in Table 8.

Table 6.

Comparison of nominal and perturbed URDF parameters for the SCARA robot.

Table 7.

Extracted MDH parameters from the perturbed SCARA robot, using small positive threshold .

Table 8.

Relations between adjacent joint axes computed from the perturbed URDF model.

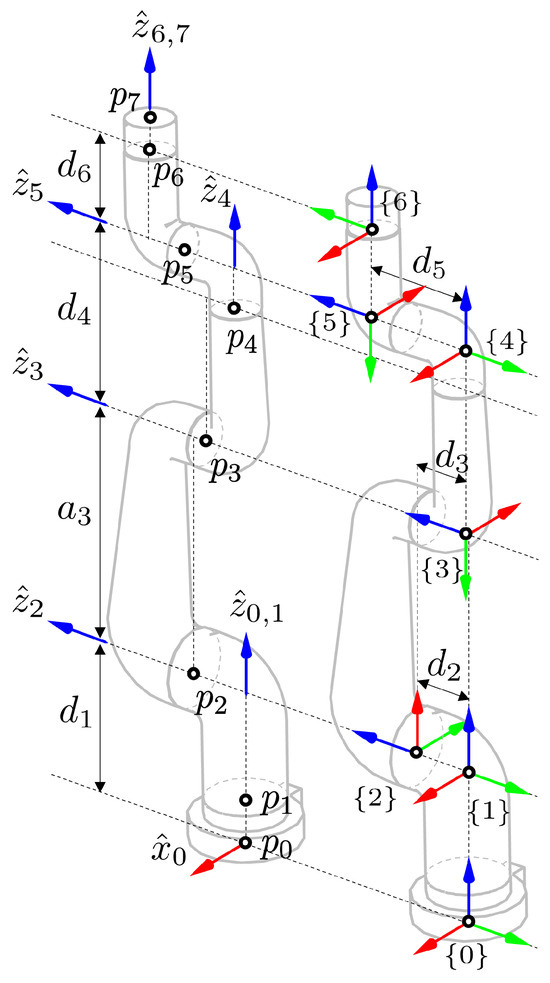

5.3. Indy7

Let us consider the MDH parameters of Indy7 manufactured by Neuromeka, which has six revolute joints based on electrical current-based control. The left side of Figure 8 shows line information denoted by including the base frame and TCF, where the line information was extracted from the -axis and the origin of the joint frame written in the URDF in [29]. The right side of Figure 8 illustrates the coordinate frames defined by MDH parameters, which were extracted from Algorithm 1. Indeed, the MDH parameters of Indy7 have been discussed in [30], but the results are different from ours. The differences between the proposed method and the reference [30] happen because the proposed method makes use of the line geometry and [30] uses the user-defined -axis, respectively. Specifically, in [30] while in Table 9, and -axis of [30], have opposite directions with the -axis shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

MDH parameters of Indy7, where the left side shows the input data regarding and denoted by the circle ∘, and the right side illustrates the frames obtained from the MDH parameters. Numerical data of input/output for Algorithm 1 are given in Table 9.

Table 9.

Indy7, where upper part and lower part imply the input data to the Algorithm 1 and the output yielded from the algorithm, respectively.

For Indy7, when the input data suggested in Table 9 are applied to Algorithm 1, the line geometry blocks are called by the algorithm, and the spatial relationships between the joint axes are determined as summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Relations between adjacent joint axes computed from the Indy7 model.

The aforementioned selections yield the MDH parameters for Indy7 in the Algorithm 1. As a result, a pair of input and output data for all joints are listed in Table 9 and denoted on the right side of Figure 8. Note that any point can be arbitrarily chosen along the line (i.e., the joint axis) since the MDH parameterization only requires that lies on the axis direction . For example, if is selected as the intersection point between and , then the resulting value of becomes zero.

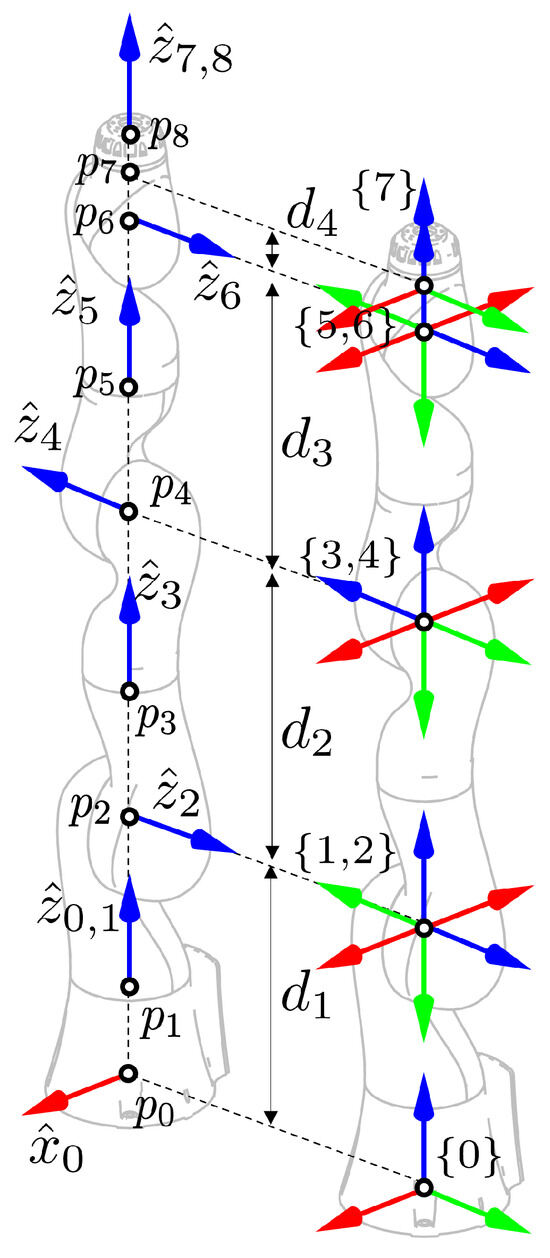

5.4. KUKA LBR Iiwa

The KUKA LBR iiwa is one of the widely used seven-dof robotic manipulators, which has seven revolute joints. The left side of Figure 9 shows line information denoted by including the base frame and TCF, where the line information was extracted from the -axis and the origin of the joint frame written in the URDF in [31]. The right side of Figure 9 illustrates the coordinate frames defined by MDH parameters extracted from Algorithm 1. When the input data suggested in Table 11 are applied to Algorithm 1, the line geometry blocks are called by the algorithm, and the spatial relationships between the joint axes are determined as summarized in Table 12.

Figure 9.

MDH parameters of KUKA LBR iiwa, where the left side shows the input data regarding and denoted by the circle ∘, and the right side illustrates the frames obtained from the MDH parameters. Numerical data of input/output related to Algorithm 1 are given in Table 11.

Table 11.

KUKA LBR iiwa, where upper part and lower part imply the input data to the Algorithm 1 and the output yielded from the algorithm, respectively.

Table 12.

Relations between adjacent joint axes computed from the KUKA LBR iiwa model.

5.5. UR5

The UR-5 is one of the widely used six-dof robotic manipulators, which has six revolute joints. The left side of Figure 10 shows line information denoted by including the base frame and TCF, where the line information was extracted from the -axis and the origin of the joint frame written in the URDF [32]. The right side of Figure 10 illustrates the coordinate frames defined by MDH parameters extracted from Algorithm 1. When the input data suggested in Table 13 are applied to Algorithm 1, the line geometry blocks are called by the algorithm, and the spatial relationships between the joint axes are determined as shown in Table 14.

Figure 10.

MDH parameters of UR5, where the left side shows the input data regarding and denoted by the circle ∘, and the right side illustrates the frames obtained from the MDH parameters. Numerical data of input/output related to Algorithm 1 are given in Table 13.

Table 13.

UR5, where the upper part and lower part imply the input data to the Algorithm 1 and the output yielded from the algorithm, respectively.

Table 14.

Relations between adjacent joint axes computed from the UR5 model.

6. Conclusions

This paper has presented how to extract the MDH parameters of single-branched robotic manipulators using the line geometry, ultimately, for kinematic modeling. The extracted MDH parameters could be used to define the adjacent transformation between the coordinate frames while finding out the exponential coordinates, joint twists, and joint matrices derived from the MDH parameters. The line geometry played core roles in extracting the MDH parameters based on the relation between line and points, the relation between two lines, a common perpendicular line, and the feet of a common perpendicular line, which are concatenated into the line geometry block. Also, it was important to classify how two adjacent lines are located relative to each other such as collinear, distant parallel, intersected, and skewed. Finally, the MDH extraction method was summarized in the algorithm to yield four parameters such as link twist, link length, joint offset distance, and joint offset angle. By combining parts of MDH parameters into the generalized joint variables, forward kinematics could be completed. The completeness of the proposed algorithm was verified through the conventional SCARA robot and three different commercial Indy7, KUKA LBR iiwa, and UR5 robots. Although the kinematic modeling using the MDH parameters was not new, the proposed algorithm was able to overcome the disadvantage that the MDH parameters are differently defined by user-defined coordinate frames, because the line geometry provides a unique and systematic method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; Methodology, M.S.; Software, M.S.; Validation, M.S.; Formal analysis, M.S.; Investigation, M.S.; Data curation, M.S.; Writing—original draft, M.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.S. and Y.C.; Supervision, Y.C.; Project administration, Y.C.; Funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Institute of Civil-Military Technology Cooperation funded by the Defense Acquisition Program Administration and the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy of the Korean government under grant No. 22-CM-EC-36, and in part by the Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy, under grant No. 20023257, South Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The source code and sample data used for the algorithmic MDH parameter extraction are openly available at https://github.com/MinchangSung0223/AlgorithmicMDH (accessed on 27 April 2025). Additional simulation results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the organizations that provided data and simulation models used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Abbreviations

- DH—Denavit–Hartenberg

- MDH—Modified Denavit–Hartenberg

- PoE—Product of Exponentials

- SCARA—Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm

- URDF—Unified Robot Description Format

- TCF—Tool Coordinate Frame

Appendix A. Comparison of Kinematic Parameterizations

Table A1.

Comparison of PoE, MDH, and DH formulations for n-DOF serial manipulators.

Table A1.

Comparison of PoE, MDH, and DH formulations for n-DOF serial manipulators.

| Category | PoE | MDH | DH |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of parameters | |||

| required | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| required | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Frame consistency | global | local | local |

| x-axis assignment | unnecessary | systematic | manual and ambiguous |

| Multi-DOF joint support | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

Note: ✓ = supported; ✗ = not supported.

Appendix B. Derivation of Line Geometry Formulas

In this appendix, detailed derivations of the equations presented in the main text are provided.

Appendix B.1. Deviation of Equation (11)

This derivation shows the step-by-step procedure to obtain the closest point :

Appendix B.2. Deviation of Equation (13)

This derivation shows the step-by-step procedure to obtain the closest point from an arbitrary point t:

Appendix B.3. Deviation of Equation (16)

This derivation shows the procedure to calculate the moment vector of the common perpendicular line connecting two lines and :

Appendix B.4. Deviation of Equation (20)

This derivation shows the procedure to calculate the moment vector of the common perpendicular line connecting two lines and :

Appendix B.5. Deviation of Equation (22)

This derivation shows how the scalar projection of the intersection point onto the vector is computed:

For the third term () of the right-hand side of Equation (21), since we can observe the following

then we have

Appendix B.6. Deviation of Equation (23)

This derivation shows the procedure to calculate the projection of the intersection point onto the vector :

Appendix B.7. Deviation of Equation (25)

This derivation shows the procedure to calculate the scalar projection :

Appendix B.8. Deviation of Equation (26)

This derivation shows the procedure to obtain the explicit expression for intersection point :

References

- Featherstone, R. Robot Dynamics Algorithms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J.K.; Hunt, K.H.; Pennock, G.R. Robots and screw theory: Applications of kinematics and statics to robotics. J. Mech. Des. 2004, 126, 763–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.M.; Li, Z.; Sastry, S.S. A Mathematical Introduction to Robotic Manipulation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K.M.; Park, F.C. Modern Robotics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayati, S.; Mirmirani, M. Improving the absolute positioning accuracy of robot manipulators. J. Robot. Syst. 1985, 2, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denavit, J.; Hartenberg, R.S. A kinematic notation for lower-pair mechanisms based on matrices. J. Appl. Mech. 1955, 22, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartenberg, R.; Danavit, J. Kinematic Synthesis of Linkages; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, M.E.; Roth, B. The near-minimum-time control of open-loop articulated kinematic chains. J. Dyn. Sys. Meas. Control 1971, 93, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, R. A Program for Simulating Robot Dynamics; Working Paper 155; Department of Artificial Intelligence, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J.J. Introduction to Robotics; Pearson Educacion: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin, H. A note on Denavit-Hartenberg notation in robotics. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Long Beach, CA, USA, 24–28 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, K.J.; Schmiedeler, J. Chapter 1 Kinematics, Handbook of Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Corke, P.I. A Simple and Systematic Approach to Assigning Denavit–Hartenberg Parameters. IEEE T. Rob. 2007, 23, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ye, C.; Ding, H. A computationally efficient and robust kinematic calibration model for industrial robots with kinematic parallelogram. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Macau, China, 5–8 December 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, C.; Vilaça, J.L.; Monteiro, S.; Erlhagen, W.; Bicho, E. Automatic Denavit-Hartenberg Parameter Identification for Serial Manipulators. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; Volume 1, pp. 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeevlochana, C.G.; Saha, S.K.; Kumar, S. Automatic Extraction of DH Parameters of Serial Manipulators using Line Geometry. In Proceedings of the 2nd Joint International Conference on Multibody System Dynamics, Stuttgart, Germany, 29 May–1 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Pan, H.; Lu, K.; Cheng, Y. POE-based kinematic calibration for serial robots using left-invariant error representation and decomposed iterative method. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 186, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, W. An integrated kinematic calibration and dynamic identification method with only static measurements for serial robot. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 28, 2762–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, S. Kinematic-parameter identification for serial-robot calibration based on POE formula. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2010, 26, 411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Löwe, H.; Li, Z. POE-based robot kinematic calibration using axis configuration space and the adjoint error model. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1264–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserles, A.; Munthe-Kaas, H.Z.; Nørsett, S.P.; Zanna, A. Lie-group methods. Acta Numer. 2000, 9, 215–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullo, F.; Murray, R.M. Proportional Derivative (PD) Control on the Euclidean Group; CDS Technical Report 95-010; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, W.V.D.; Pedoe, D. Methods of Algebraic Geometry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, M.T. Mechanics of Robotic Manipulation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.B. Plücker coordinates for lines in the space. In Problem Solver Techniques for Applied Computer Science, Com-S-477/577 Course Handout; Iowa State University: Ames, Iowa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, M. Algorithmic MDH. Available online: https://github.com/MinchangSung0223/AlgorithmicMDH (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Coumans, E.; Bai, Y. Pybullet, a Python Module for Physics Simulation for Games, Robotics and Machine Learning. 2016. Available online: http://pybullet.org (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- ROS.org. URDF. Available online: http://wiki.ros.org/urdf (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Neuromeka. Indy7 URDF. Available online: https://github.com/neuromeka-robotics/indy-ros (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Tadese, M.; Pico, N.; Seo, S.; Moon, H. A Two-Step Method for Dynamic Parameter Identification of Indy7 Collaborative Robot Manipulator. Sensors 2022, 22, 9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KUKA. KUKA lbr Iiwa URDF. Available online: https://github.com/rtkg/lbr_iiwa (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Universal Robotics. UR5 URDF. Available online: https://github.com/ros-industrial/universal_robot (accessed on 27 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).