Students’ Perceptions of AI Digital Assistants (AIDAs): Should Institutions Invest in Their Own AIDAs?

Abstract

1. Introduction

RQ1: What are distance learning students’ perspectives of i-AIDA relative to using a p-AIDA, and do they change over time as students gain more experience with AI?

RQ2: To what extent are there particular subgroups of distance learners who have similar or distinctive perspectives on i-AIDA, and how are these related to individual characteristics?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Instruments

2.2. Procedure and Data Analysis

3. Results

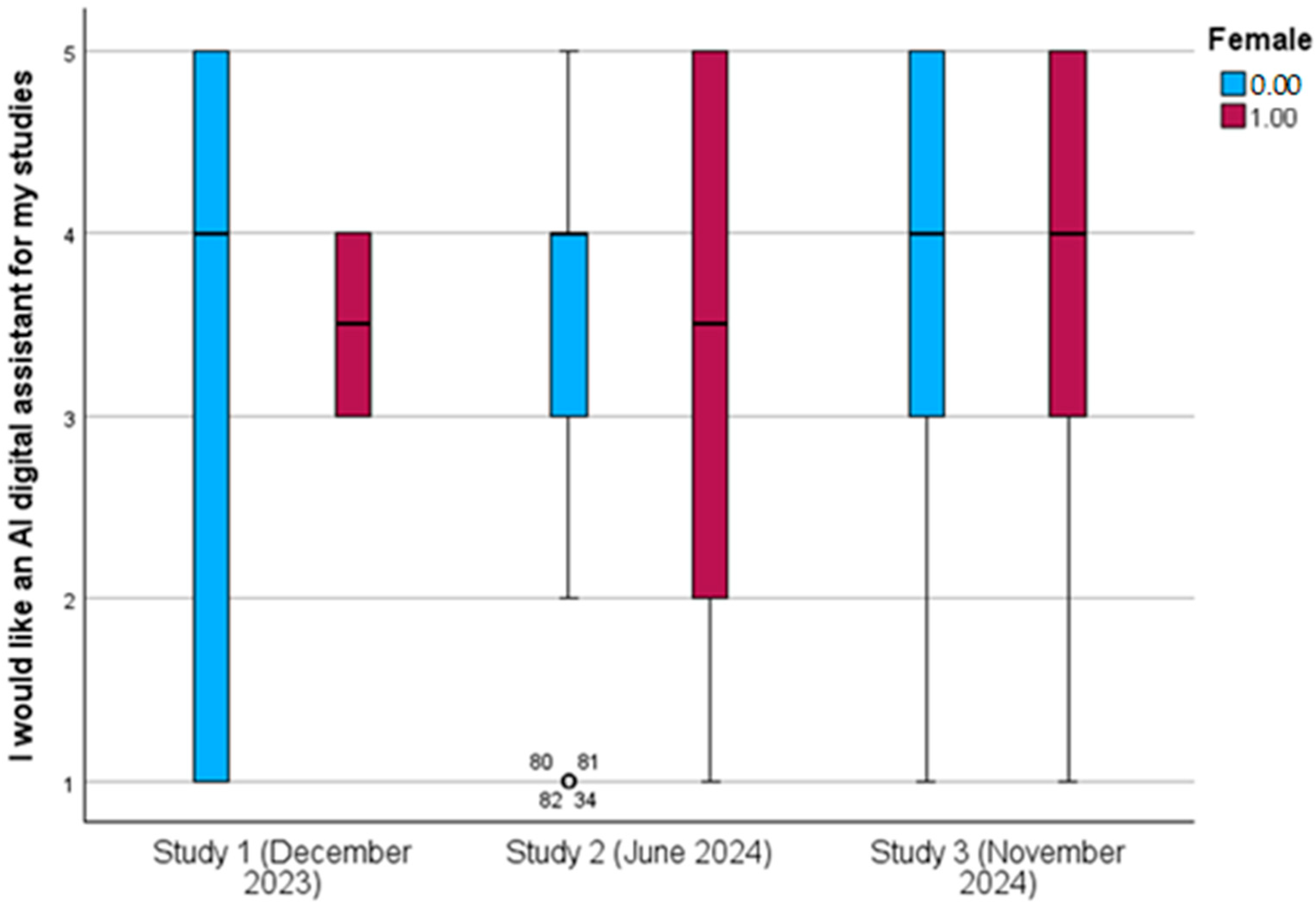

3.1. RQ1: What Are Distance Learning Students’ Perspectives of i-AIDA Relative to Using a p-AIDA, and Do They Change over Time as Students Gain More Experience with AI?

3.2. RQ2 Distinct Subgroups of Students’ Preferences Towards i-AIDA

We are not paying for a computer to replace tutors. This is a joke and will end badly. Stop pushing this agenda on us. It’s a disgrace that my university, which I pay real money for, is lazily making itself worthless. (S3_057, Female, level 3, unknown discipline)

I thought university was about studying, researching, discovering things that matter to me and my way of learning. Not about asking a bot for answers or even a path to them. (S3_066, Male, level 1, Computing)

I think this is the future, but until AI improves and proves it can provide accurate results while considering different viewpoints—especially in humanities, where there isn’t just one correct answer—it is dumbing down degrees. (S3_110, Female, level 3, Arts and Humanities)

It could allow me to see what I understand or not in the course, so I can revise/investigate the subject more in depth. It could be a good way to revise—but to do that, the questions need to be written clearly. (S2_80, Female, PG, Health and Social Care)

1. Where tutor-led tutorials don’t take place due to low attendance, an AI-generated email at the start of each study week could provide prompts, questions, or ideas to help students engage with the module materials. 2. It could refine plagiarism checks by disregarding references and essay questions to avoid skewing scores. It’s crucial to maintain real interactions with tutors to enhance learning through discussions and debates, rather than becoming overly reliant on AI. (S3_037, Female, level 1, Psychology)

An AI assistant could support students with time management difficulties, such as those with ADHD or executive functioning challenges, by prompting them to prepare for assignments or tutorials and notifying them of missed questions. It could also assist with referencing and transcription of dictation. AI has a high energy consumption, contributing to a significant carbon footprint. It’s important to be transparent about this, as many students are concerned about climate change. (S3_023, Female, level 1, Business)

AI could offer real-time feedback on coursework, helping identify areas for improvement before submission. It could also recommend resources based on study topics, supporting deeper exploration… Flexibility is key, especially for students balancing work, family, and studies. Data privacy is also crucial—students must feel secure when using AI in their studies. (S3_008, Male, level 1, Business)

To help and provide an on-track timetable based on recommended study speed and pace. To determinate if I’m one track to hit my assessment deadline at the pace I’m working at. (S3_061, Male, level 1, Computing)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| i-AIDA | Institutional AI digital assistant |

| p-AIDA | Public AI digital assistant such as ChatGPT |

| OU | The Open University UK |

| GenAI | Generative artificial intelligence |

References

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, A.; Khosravi, H.; Sadiq, S.; Gašević, D.; Siemens, G. Impact of AI assistance on student agency. Comput. Educ. 2024, 210, 104967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Brusilovsky, P.; Cukurova, M.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Hernandez-Leo, D.; Järvelä, S.; Mavrikis, M.; Rienties, B. The promise and challenges of generative AI in education. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahić, I.; Ebner, M.; Schön, S.; Edelsbrunner, S. Exploring the Use of Generative AI in Education: Broadening the Scope; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, K.; Yan, L.; Echeverria, V.; Zhao, L.; Alfredo, R.; Milesi, M.; Fan, J.X.; Li, X.; Gasevic, D.; et al. Chatting with a Learning Analytics Dashboard: The Role of Generative AI Literacy on Learner Interaction with Conventional and Scaffolding Chatbots. In Proceedings of the 15th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 3–7 March 2025; pp. 579–590. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, M.; Liu, Q.; Jovanovic, J. AI for data generation in education: Towards learning and teaching support at scale. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2025, 56, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedrakyan, G.; Borsci, S.; van den Berg, S.M.; van Hillegersberg, J.; Veldkamp, B.P. Design Implications for Next Generation Chatbots with Education 5.0; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ravšelj, D.; Keržič, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L.; Brezovar, N.A.; Iahad, N.; Abdulla, A.A.; Akopyan, A.; Aldana Segura, M.W.; AlHumaid, J.; et al. Higher education students’ perceptions of ChatGPT: A global study of early reactions. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, J. Student Generative AI Survey 2025; Higher Education Policy Institute: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, R.; Jiang, M.; Yu, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, S. Does ChatGPT enhance student learning? A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. Comput. Educ. 2025, 227, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibani, A.; Knight, S.; Kitto, K.; Karunanayake, A.; Buckingham Shum, S. Untangling Critical Interaction with AI in Students’ Written Assessment. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Henderson, M.; Pepperell, N.; Slade, C.; Liang, Y. Student Perspectives on AI in Higher Education: Student Survey; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cotino-Arbelo, A.E.; González-González, C.; Molina Gil, J. Youth Expectations and Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2025, 9, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Sharma, R.C. Challenging the status quo and exploring the new boundaries in the age of algorithms: Reimagining the role of generative AI in distance education and online learning. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2023, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Domingue, J.; Duttaroy, S.; Herodotou, C.; Tessarolo, F.; Whitelock, D. What distance learning students want from an AI Digital Assistant. Distance Educ. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herodotou, C.; Maguire, C.; McDowell, N.; Hlosta, M.; Boroowa, A. The engagement of university teachers with predictive learning analytics. Comput. Educ. 2021, 173, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, F.J.H.; Díaz, I.A.; Reche, M.P.C.; Rodríguez, J.M.R. A tour of Open Universities through literature. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2019, 20, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, O.E.; Gasevic, D.; Jovanovic, J.M.; Pardo, A. From Study Tactics to Learning Strategies: An Analytical Method for Extracting Interpretable Representations. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2018, 12, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqr, M.; López-Pernas, S.; Murphy, K. How group structure, members’ interactions and teacher facilitation explain the emergence of roles in collaborative learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2024, 112, 102463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Talib, N.I.; Abd Majid, N.A.; Sahran, S. Identification of Student Behavioral Patterns in Higher Education Using K-Means Clustering and Support Vector Machine. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Herodotou, C.; Tessarolo, F.; Domingue, J.; Duttaroy, S.; Whitelock, D. An institutional AI digital assistant: What do distance learners expect and value? Ubiquity Proc. 2024, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienties, B.; Tessarolo, F.; Coughlan, T.; Herodotou, C.; Domingue, J.; Whitelock, D. A Design-Based Research Approach to what distance learners expect and value from an Institutional AI Digital Assistant. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J. Provide or Punish? Students’ Views on Generative AI in Higher Education; Higher Education Policy Institute: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Exploring the Use of Artificial Intelligence for Qualitative Data Analysis: The Case of ChatGPT. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231211248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Wiliam, D.; Hattie, J. The Future of AI in Education: 13 Things We Can Do to Minimize the Damage. 2023. EdArXiv Preprints 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 10 | 96 | 211 |

| Instrument | Online demo and interview Follow-up online survey 18 Likert-response questions [15] 5 open questions | Online survey 25 Likert-response questions 15 check-box items for GenAI usage 5 open questions [21,22] | Same survey as in Study 2 with two screenshots of i-AIDA |

| Time of measurement | December 2023–February 2024 | 15 May–15 June 2024 | November 2024 |

| Female | 60% | 52% | 63% |

| Age | 40.00 (SD = 13.09) | 52.30 (SD = 16.61) | 45.84 (SD = 16.37) |

| Response rate | 4% | 5% | 11% |

| Data previously reported in | [15] | [21,22] | New data |

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F-Value | Eta | |

| Personalisation and Accessibility: The AIDA is personalised to individual needs and learning approaches, including those with disabilities or specific learning requirements. | 4.13 | 1.46 | 3.81 | 1.21 | 4.02 | 1.11 | 1.196 | 0.008 |

| Real-time Assistance and Query Resolution: The AIDA provides 24/7 support for academic queries and guidance. | 4.25 | 1.04 | 3.72 | 1.26 | 3.96 | 1.22 | 1.638 | 0.010 |

| Support for Academic Tasks: The AIDA assists with academic activities like summarizing key points from study materials, providing feedback on assignments, helping with grammar and writing, and offering study resources. | 3.88 | 1.13 | 3.35 | 1.40 | 3.60 | 1.44 | 1.245 | 0.008 |

| Emotional and Social Support: The AIDA provides emotional support or motivation if needed, especially in the context of distance learning or for students with social anxieties. | 3.25 | 1.28 | 2.95 | 1.33 | 3.36 | 1.39 | 2.982 | 0.019 |

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F-Value | Eta | |

| Academic Integrity: potential misuse of AI for completing assignments, potential plagiarism, and academic integrity. | 4.38 | 0.74 | 4.16 | 1.08 | 4.13 | 1.00 | 0.222 | 0.001 |

| Data Privacy and Use: how student data and inputs to the AI are used, stored, and potentially shared, emphasizing the need for transparency and consent. | 4.13 | 0.84 | 4.11 | 1.05 | 4.08 | 1.02 | 0.976 | 0.000 |

| Operational Challenges: how AI might inadvertently affect learning outcomes and student interaction, and the importance of ensuring that AI tools are accurate and reliable. | 4.25 | 0.71 | 4.03 | 0.99 | 4.05 | 0.93 | 0.199 | 0.001 |

| Ethical and Social Implications: the potential impact of AI on learning processes and the necessity of balancing technological advancement with human-centric educational practices, keeping the human (student/tutor/academic staff) in the process, and being able to talk to a human. | 4.13 | 0.84 | 4.13 | 1.05 | 4.05 | 1.06 | 0.831 | 0.001 |

| Future of Education: how AI integration might change the nature of education and assessments, necessitating a shift in teaching methods and learning expectations. | 4.00 | 0.76 | 4.03 | 1.10 | 3.95 | 1.04 | 0.811 | 0.001 |

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F-Value | Eta | |

| Accuracy and Specificity: I value the accuracy in responses as it is based upon institutional curated content. It not only provides relevant answers but also directs students to specific resources for further learning. | 4.13 | 0.99 | 3.72 | 1.27 | 4.01 | 1.17 | 2.209 | 0.013 |

| 24/7 Availability and Immediate Feedback: i-AIDA would be available round-the-clock for immediate feedback and support in an academic setting. | 4.00 | 1.07 | 3.85 | 1.15 | 3.99 | 1.20 | 0.422 | 0.003 |

| User Experience and Interface Design: i-AIDA would be easy to use, user-friendly, and integrated (e.g., in OU module websites). | 4.25 | 1.04 | 3.81 | 1.19 | 3.96 | 1.22 | 0.444 | 0.005 |

| Language and Accessibility: i-AIDA would be multi-lingual and accessible, catering to a diverse student body. | 4.43 | 0.79 | 3.77 | 1.18 | 3.94 | 1.20 | 1.386 | 0.009 |

| Personalisation and Relevance: i-AIDA would provide personalised responses, tailored to my academic needs and context, differentiating it from generic AI tools. | 3.75 | 1.49 | 3.69 | 1.20 | 3.83 | 1.22 | 0.414 | 0.003 |

| 1 Highly Critical of i-AIDA | 2 Supporters of i-AIDA | 3 Keen Support. of i-AIDA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F-Value | Eta | |

| New or continuing student (1–2) | 1.85 | 0.36 | 1.83 | 0.38 | 1.81 | 0.40 | 0.257 | 0.002 |

| Highest level of education (1–5) | 3.51 | 0.93 | 3.47 | 1.04 | 3.10 | 1.07 | 5.008 ** | 0.033 |

| Age (18–80+) | 45.10 | 17.70 | 62.80 | 10.30 | 37.60 | 11.60 | 140.175 *** | 0.486 |

| Female (0–1) | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 2.533 | 0.017 |

| Use of GenAI in general (0–1, 6 items) | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 13.509 *** | 0.083 |

| Use of GenAI for educational purposes (0–1, 6) | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 11.160 *** | 0.070 |

| Want an AI digital assistant (real-time, personalised, academic tasks, emotional/social, 1–5, 4) | 1.60 | 0.59 | 3.58 | 0.81 | 4.25 | 0.64 | 233.132 *** | 0.611 |

| Want an i-AIDA specifically developed by the OU relative to other systems (1–5, 6) | 1.67 | 0.79 | 3.90 | 0.67 | 4.41 | 0.59 | 288.176 *** | 0.660 |

| AI challenges (1–5, 5) | 4.31 | 1.12 | 4.17 | 0.67 | 3.92 | 0.84 | 5.023 ** | 0.033 |

| AI for quizzes (1–5, 5) | 1.79 | 0.91 | 3.89 | 0.75 | 4.33 | 0.67 | 191.746 *** | 0.564 |

| M | SD | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Use of GenAI in general | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.634 | |||||||||||

| 2. Use of GenAI for educational purposes | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.686 | 0.484 ** | ||||||||||

| 3. Like an AI digital assistant for my studies | 3.55 | 1.37 | - | 0.315 ** | 0.359 ** | |||||||||

| 4. Want an AI digital assistant (real-time, personalised, academic tasks, emotional/social) | 3.65 | 1.11 | 0.877 | 0.265 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.779 ** | ||||||||

| 5. Want an i-AIDA specifically developed by the OU relative to other systems | 3.86 | 1.10 | 0.956 | 0.280 ** | 0.300 ** | 0.756 ** | 0.891 ** | |||||||

| 6. AI challenges | 4.06 | 0.84 | 0.873 | −0.107 | −0.077 | −0.196 ** | −0.144 * | −0.056 | ||||||

| 7. AI for quizzes | 3.83 | 1.11 | 0.932 | 0.266 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.733 ** | 0.785 ** | 0.789 ** | −0.091 | |||||

| 8. Comfortable with institution using my data | 3.14 | 1.36 | - | 0.204 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.517 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.510 ** | −0.094 | 0.544 ** | ||||

| 9. New or continuing student | 1.83 | 0.38 | - | 0.161 * | 0.002 | 0.025 | −0.047 | −0.017 | −0.052 | −0.101 | −0.077 | |||

| 10 Highest level of education | 3.29 | 1.06 | - | −0.015 | −0.014 | −0.174 ** | −0.208 ** | −0.139 * | 0.161 ** | −0.177 ** | −0.144 * | 0.053 | ||

| 11 Age | 47.82 | 16.69 | - | −0.131 * | −0.109 | −0.079 | −0.096 | −0.056 | 0.122 * | −0.016 | 0.008 | 0.1 | 0.136 * | |

| 12. Female | 0.59 | 0.49 | - | −0.07 | −0.101 | 0.045 | 0.09 | 0.097 | −0.003 | 0.002 | 0.021 | −0.061 | −0.068 | −0.154 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rienties, B.; Tessarolo, F.; Coughlan, E.; Coughlan, T.; Domingue, J. Students’ Perceptions of AI Digital Assistants (AIDAs): Should Institutions Invest in Their Own AIDAs? Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4279. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15084279

Rienties B, Tessarolo F, Coughlan E, Coughlan T, Domingue J. Students’ Perceptions of AI Digital Assistants (AIDAs): Should Institutions Invest in Their Own AIDAs? Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(8):4279. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15084279

Chicago/Turabian StyleRienties, Bart, Felipe Tessarolo, Emily Coughlan, Tim Coughlan, and John Domingue. 2025. "Students’ Perceptions of AI Digital Assistants (AIDAs): Should Institutions Invest in Their Own AIDAs?" Applied Sciences 15, no. 8: 4279. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15084279

APA StyleRienties, B., Tessarolo, F., Coughlan, E., Coughlan, T., & Domingue, J. (2025). Students’ Perceptions of AI Digital Assistants (AIDAs): Should Institutions Invest in Their Own AIDAs? Applied Sciences, 15(8), 4279. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15084279