Abstract

The significance of the quality issue in Industry 4.0 increases due to the dynamically changing economy. Not only selected workers who form the quality department must be aware of this fact, but each member of the staff must be as well. A considerable portion of responsibility concerning the proper preparation of workers in the field of quality relies on the education system that should help graduates develop a pro-quality attitude. In order to fulfill this aim, schools must use a number of tools, including, among others, the ISO 9001 quality management system—one of the elements introduced by the author’s model of factors influencing the development of students’ pro-quality attitude. The subject of this article is to determine the impact of the quality management system implemented in schools on the development of students’ pro-quality attitude—an issue that allows us, on the one hand, to ensure a higher level of education and, on the other hand, to use it as an element of smart learning. For the needs of the performed research, the author has collected secondary data from the literature analysis, as well as primary data from surveys performed on 1294 people. The research results deserve the attention of people who manage schools to improve the use of the quality management system implemented in schools in order to develop students’ attitudes towards quality and to improve the system itself more effectively. They are also important for enterprises, which can positively influence young people’s (future participants of the labor market based on Industry 4.0) education through cooperation with schools. The research performed by the author proved the hypothesis according to which the implementation of the quality management system is not sufficient to ensure effective development of students’ pro-quality attitudes.

1. Introduction

In the era of global economy and Industry 4.0, the issue of quality has become more and more relevant [1,2,3] (p. 27). For years, it has been constantly evolving, following the industry and transforming into Quality 4.0 [4]. Its current formula, as well as the circumstances that accompany it, requires undertaking ambitious and appropriately directed actions. It is no longer sufficient to use only selected tools to ensure an appropriate level of quality. People who use these tools should do so fully and consciously. To ensure the highest possible level of quality in their work, they should know how to implement it and understand why applying themselves is so important. Therefore, employees must have a pro-quality attitude [5]—preferably before they start work, i.e., while they get their education.

However, this creates a serious challenge for the educational system, which, according to researchers’ opinions, must transform into Education 4.0, just like the industry [6]. On the one hand, employers require from their employees knowledge and skills concerning quality issues [7]. On the other hand, employers’ willingness to invest in workers’ training is limited due to concerns related to the transfer of expertise to competitive companies in the case a worker decides to change the place of employment [8]. This problem mainly pertains to temporary workers [9], who constitute a significant portion of employees in the labor market.

This situation is particularly important, among other things, because of the urgency of action due to the aforementioned entry into the era of Industry 4.0. As Perales, Valero, and García [10] indicate, virtualization, interoperability, autonomization, real-time availability, flexibility, service orientation, and energy efficiency are the main features characteristic of Industry 4.0. Even though each of these elements demands separate analysis, their coherence and common purpose leading to a more autonomic economy, making use of less human support, aiming at environment protection, and, at the same time, higher orientation towards customers, are noticeable. As a result, time plays an even more significant role in Industry 4.0 [11] due to the greater capacities of robots, which are faster than people, decisions made by artificial intelligence in real time, and growing customers’ demands, which refer to getting their product or service faster. Moreover, Industry 4.0 directly corresponds to advanced technologies integrated into different branches of industry [12]. The above-mentioned issues clearly demonstrate the importance of quality with all its components related to human behavior such as meticulousness, precision, timeliness, diligence, or taking responsibility for quality. At the same time, there is a lack of full control of workers by their supervisors or the reward and punishment management system [13]. Industry 4.0 must make use of Total Quality Management (TQM) and Lean Management (LM) concepts. The characteristic feature of these concepts is the full engagement of employers in quality work [14,15], which contributes to developing a proper pro-quality attitude.

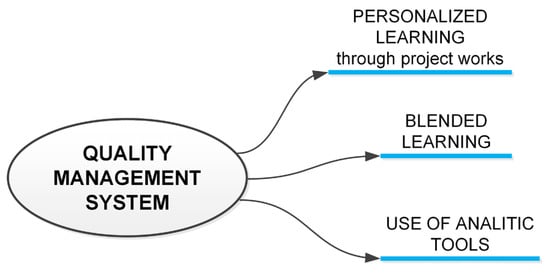

The tools used in education to ensure quality, such as the quality management system (QMS), can be considered an opportunity in this respect. Due to its nature, when used appropriately as a living example and as a basis for cooperation with students, the quality management system can go beyond the framework of an ordinary quality tool. Due to its nature and the numerous analytical tools that accompany it, it can be an excellent basis for engaging students in pro-quality processes, developing the right attitude (Figure 1), and supporting personalized learning thanks to the possibility of using project work. What is more, it can be an interesting and engaging way for students not only in the school building and during stationary classes but also when using blended learning [16].

Figure 1.

Possibilities related to the use of the quality management system in education. Source: Own study.

Based on the literature studies and previous studies, the author identified a research gap concerning the lack of research on the impact of the quality management system functioning at school according to the ISO 9001 standard [17] on students’ attitudes towards quality, which was also a contribution to the implementation of the research. On this basis, the research objective was formulated, assuming the determination of the impact of the system on students’ attitudes towards the issue of quality. According to the assumptions made, the implementation of the research would allow us not only to fill the aforementioned gap but also to obtain a practical value, i.e., develop a basis for improving the use of the system that promotes quality.

2. Literature Review

The issue of a pro-quality attitude is raised in the publications of many researchers. In a special way, the need to be guided by quality in one’s actions is raised in works discussing the issue of a quality culture, also called a pro-quality culture, by which we mean all pro-quality actions undertaken by an organization [18]. It constitutes an issue close to TQM philosophy; however, there is no unanimity concerning mutual relations between these two issues among researchers. The literature includes views treating them as separate, equivalent subject matters [19,20], identifying them [21] (p. 17), perceiving a quality culture as inferior to TQM philosophy, constituting one of its components, or deriving from TQM [22,23], as well as treating TQM philosophy as a way leading to the quality culture [24,25]. Depending on the way the problem is perceived, both of these approaches seem to be reasonable. From the pragmatic point of view, the author thinks that the latter thesis seems to be the most proper option, according to which TQM philosophy, even though extensive and comprehensive, is one of the tools bringing an organization closer to a quality culture, elusive in its nature.

TQM itself is not perceived in a consistent way either. A lot of researchers pay attention to this problem, as well as to a great number of existing definitions [26,27,28,29]. This results mainly from the lack of regulations within TQM, the lack of unambiguous criteria legitimizing an organization to state that this philosophy has been implemented, and—what seems to be of key importance—the lack of researchers’ unanimity in defining quality. However, according to one of the most cited definitions belonging to Kanji, Total Quality Management is a ‘management philosophy that fosters an organizational culture committed to customer satisfaction through continuous improvement’ [30] (p. 2).

At the same time, the quality culture can be defined as: ‘an organizational culture that intends to enhance quality permanently and is characterized by two distinct elements: on the one hand, a cultural/psychological element of shared values, beliefs, expectations and commitment towards quality and, on the other hand, a structural/managerial element with defined processes that enhance quality and aim at coordinating individual efforts’ [31] (p. 10). This definition shows the importance of a pro-quality attitude of an organization’s members, emphasizing, at the same time, the significance of organizational conditions.

It illustrates the complexity of the situation, in which, on the one hand, the structure of an organization and its regulations fostering the development of a pro-quality culture will not allow for its effective implementation and maintenance without the pro-quality attitudes of workers. On the other hand, the pro-quality attitude of workers is not sufficient to create a quality culture. Both of these elements are strongly inter-related; that is why a comprehensive impact is required. In accordance with the previously made assumption, the implementation of the TQM philosophy can be treated as a comprehensive impact. However, in this place, the basic attitude of the organization’s members is of great importance. As Ehlers notices, this idea has played a minor role in education for a long time due to the complexity of factors influencing quality in this field, including, among others, teachers’ attitudes [32]. It seems to lead to a vicious circle, in which a lack of brave decisions concerning the start of actions to develop pro-quality attitudes during the phase of school education will not allow breaking the created deadlock. These are the people, who are still students today, who will be teachers and representatives of different professions soon and who will be able to co-create the quality culture in schools and other entities.

In the world, there are many known, usually grassroots, examples of influencing students’ attitudes towards quality. They concern both additional forms of quality promotion among students, as well as teaching about quality, with various forms of examples coming from the school. There are significantly fewer examples related to social and cultural factors, which the author mentioned in his earlier work [33]. In accordance with the literature recommendations [34,35,36,37], the berry-picking model by Bates [38] was used in the research process to determine the factors that may influence the formation of students’ attitudes towards quality. This model assumes a dynamic way of searching for information, which was crucial considering the topic undertaken by the author and the limited number of sources containing structured and comprehensive data, as well as the need to use diversified data sources.

The author used various data sources in the query: two widely available online databases, such as ProQuest and EBSCO (including the ERIC database), as well as other online sources and traditional books in stationary libraries. The query aimed to find information on various initiatives undertaken around the world, which affect students’ attitudes towards quality. In the first stage, available databases were searched for this purpose. Where possible, the author searched for sources using the main keyword, which was ’pro-quality attitude’, in combination with entries that narrowed it down, i.e., primarily: ‘school’, ‘education’, ‘school students’, ‘learning’, ‘teaching’, ‘shaping’, and ‘teachers’. The results were reviewed iteratively—individual publications containing the information sought were the starting point for subsequent queries. This way, the keywords were enriched with, among others, the names of individual initiatives, places where they were implemented, or the names of people responsible for them. Subsequent answers also determined the way of searching for further information—finding information in internet sources about initiatives undertaken in the USA at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s suggested to the author the need to use stationary libraries in order to find information about local initiatives whose sources have not yet been digitized. The author did not use a time restriction, which allowed for a review of initiatives undertaken around the world over many years.

The application of the berry-picking model allowed for the adjustment of keywords and search sources and changing expectations, i.e., primarily newly discovered initiatives. As a result, this allowed the author to find initiatives with different scales of impact, implemented at different times, in different types of schools, and undertaken in different parts of the world.

The precursor of activities shaping the right attitude of students towards quality can be considered Mount Edgecumbe High School—a small school in Sitka, Alaska [39], [40] (p. 273), [41] (p. 429). Thanks to the efforts of the people involved in running and supervising the school, the undertaken activities involving students were comprehensive and were related to the promotion, implementation, and improvement of quality:

- -

- Students were taught about quality, both in terms of theory and practical exercises.

- -

- Additional forms of promoting quality among students were used, including primarily involving them in work to improve quality and organizing visits to workplaces using quality instruments.

- -

- Efforts were made to make the school a model for quality: attention was paid to ensuring that all employees who had contact with students were characterized by a pro-quality attitude.

The effects of the activities were considered to have significantly changed the functioning of the school and its cooperation with the environment. These included:

- -

- Students’ participation in international trade cooperation;

- -

- Students’ participation in deciding on the allocation of the grant obtained by the school;

- -

- Students’ creation of their portfolios;

- -

- The resignation from giving students grades [21,42,43].

Evans and Lindsay [44] (p. 65), thanks to the latter, indicated that they became highly aware of the fact how much acquiring knowledge depends on ourselves.

King and Kovacs [45] (p. 17) point to another example of the positive impact of broadly understood pro-quality school activities on students’ attitudes towards quality. They mention Quality Learning Australasia (QLA)—an organization operating in Australia and cooperating with schools and their superior bodies. Its activity is based on the promotion of Deming’s philosophy among students and teachers and its implementation by them in practice [46]. Students in the schools where these activities were implemented successfully used quality tools to improve their academic results [47] or create system maps in the school [48]. The effects of QLA’s activity are very broad and include not only the impact on students’ attitudes towards quality but also the impact on teachers, principals, and even parents [45] (p. 17).

The largest initiative of this type known to the author is the ‘Koalaty Kid’ project, implemented by the American Society for Quality (ASQ) and based on the implementation of the TQM philosophy in schools. One of its assumptions was to require students to develop the habit of doing their job well the first time [49]. The program has covered over 800 schools, primarily in the USA, but also in Canada, Colombia, Bolivia, Brazil, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden [44] (p. 69), [50].

An interesting example of engaging students in pro-quality activities, due to its simplicity and achieved effects, was also the initiative of the Łódź Centre for Teacher Training and Practical Education (Poland), presented by Turska [51,52]. It consisted of preparing posters by students, the content of which corresponded to the title: ‘The best student project serving to improve the quality of work and life at school’. These projects were a potential source of real improvement for the school. The possibility of implementing ideas was an even greater motivation to submit their work as some of the projects ended with their actual implementation, as exemplified by:

- -

- Appointing a Student Rights Ombudsman at the Communication School Complex in Łódź;

- -

- Developing and updating documentation and markings for evacuation plans at the Post-Secondary School Complex No. 18 in Łódź;

- -

- Purchasing the necessary teaching aids to improve the conditions and quality of education at the Post-Secondary School Complex No. 4 in Łódź;

- -

- Organizing assistance for disabled students at the Post-Secondary School Complex No. 17 in Łódź.

It should be noted that the examples of activities shaping students’ pro-quality attitudes are not a closed catalog. At the same time, they indicate the possibility of shaping students’ attitudes towards quality in a very diverse way, which is presented by the author further in this work.

3. Shaping Students’ Pro-Quality Attitude

The author of this research paper considers the issue of attitude according to the definition presented by Mądrzycki [53] (p. 18), as a ‘relatively stable and coherent cognitive, emotional—motivational and behavioral representation of an entity, related to a certain subject or group of subjects’. Different authors defined this concept from various angles; however, from the work-related point of view, it was considered in very similar ways. For example, according to the definition presented by Kotler and Armstrong in 2018 [54], ‘attitude describes a person’s relatively consistent evaluations, feelings, and tendencies toward an object or idea’. It is a measurable issue, and in the case of students, its measurement plays an important role [55].

In accordance with both definitions, a pro-quality attitude should be based on a three-component model, which, from the viewpoint of consumers, entrepreneurs, and the economy—including Industry 4.0—must be concluded as:

- -

- Possessing knowledge concerning quality by a student (from general subject matter and practical issues, which are quality instruments and costs);

- -

- The sense of purpose and appropriateness of proper attitude towards quality in private life, as well as during the performance of work obligations;

- -

- Developed habits of including appropriate attitudes towards quality in one’s private and professional life.

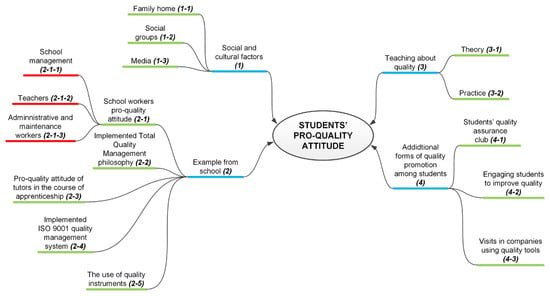

In the author’s opinion, based on literature research presented in the previous part of the paper and his own experience, a pro-quality attitude may be shaped by a number of factors, which are presented in Figure 2. Pursuant to the presented model, these are mainly social-cultural factors (1), examples from school (2), education about quality (3), and additional forms of quality promotion among students (4). For obvious reasons, it mainly refers to students’ attitude development; however, the influence of mentioned factors on different groups should also be emphasized. It concerns a direct impact, for example, in the case of an extensive impact created by media or chosen social groups, as well as an indirect impact when students share their attitudes towards quality with their closest environment. At least a partial change of attitude towards quality among people who, due to the engagement in the realization of presented issues, will try to shape other peoples’ attitudes, will be an anticipated added value of such interaction. These are mainly teachers changing their behavior related to quality and trying to be a role model for students or media workers expanding their knowledge concerning quality during media material realization.

Figure 2.

A model of factors influencing the development of students’ pro-quality attitude. Source: Own study.

It should be noted that the presented model shows a desired situation. The real interaction from certain directions may be not only neutral but even negative. Such effect is anticipated by the author mainly after the interaction of social-cultural factors (1), due to the constant too-low popularity of the issue of quality in public space, as well as in media (1-3), family talks (1-1) or peer talks (1-2) [33]. It leads to a situation in which a conscious, positive impact on the pro-quality attitude development at the site of the school is burdened with the necessity to provide counterweight.

In order to increase the effectiveness of performed actions, it is recommended not to limit to process of pro-quality attitude development only to chosen measures presented in the model. On the contrary, it should be multidimensional, coherent, and closely related to the typical activity of the school. As Skrzypek [56] notes: ‘Quality cannot function as a separate element. Integrating quality is necessary’.

In this article, the author concentrated on the analysis of one element of the system influencing students’ attitudes towards quality: school-implemented ISO 9001 quality management system (2-4), being a factor included in the group ‘example from school’ (2). At the same time, the author presented the results of empirical research referring to real influence of the school-implemented quality management system on its students.

As can be noticed, the majority of factor groups presented in the scheme, such as education about quality, additional forms of quality promotion among students, and examples from schools, are directly related to the school that a student attends and to the whole educational system of the country. This relation is most visible in the first of the enumerated groups. Discussing the issue of conducting classes about quality, attention should be mainly paid to the issue of system conditions. This subject matter has been widely presented in the author’s separate work [57]. As follows from the author’s previous research, despite the potential to create students’ pro-quality attitude in the educational system, this issue does not have its rightful place—it is ignored. It should be emphasized that it is a domain of educational systems in different countries [58].

Pro-quality actions of the school, having a direct effect on modeling the attitude towards the issue of quality, are a crucial element influencing students’ approaches to quality. The implementation of a quality management system, the use of quality tools, or prioritizing quality in the everyday life of an educational establishment can be included in pro-quality actions. This can be proved in a number of ways, such as quality principals, while shopping, maintain the school’s surroundings in tidiness and in order, engaging all workers and students in actions influencing quality or following TQM philosophy rules. Examples of such initiatives show their great effectiveness in promoting quality among children and teenagers [40,51,59].

As Stephens and Roszak state, shaping workers’ pro-quality attitudes constitutes a basic element in developing the quality culture of an organization [60]. However, the literature includes only a few references to the issue of a pro-quality attitude, even though, due to its components, it is complementary to both the quality culture and TQM philosophy [61,62,63]. Possible examples of references concern almost exclusively the attitudes of people who have already been active participants in a labor market; whereas, the influence on students before the start of their professional careers and uncontrolled development of their attitudes toward quality in the course of work should be treated as definitely more effective. In the era of Industry 4.0, this fact takes on additional importance.

4. Quality Management System in Educational Sector

A quality management system based on ISO Standard No. 9001 requirements currently constitutes one of the most well-known and commonly recognized instruments directed at ensuring and improving quality. As of the end of year 2023, the certificate confirming the implementation of this system was held by 837,000 organizations from 188 countries [64]. It is connected to a number of reasons, of which the most important are, among others, the ordered character of requirements presented to the organization, the possibility of achieving a recognizable, worldwide identifiable certificate awarded by independent entities, limitation of errors and costs, and management streamlining [65]. It seems that due to the mentioned recognizability, the system’s popularity became a self-perpetuating issue—subsequent organizations face the necessity of implementing the system because of the demand to keep up with competitive companies, which have already implemented the system, and due to a requirement to legitimize a widely recognized document certifying professional attitude to quality matters.

The implementation and maintenance of a quality management system compatible with ISO Standard No. 9001, notwithstanding related problems [66], is connected with a number of benefits, including, among others, improving the quality of offered products and services, ordering and facilitating performed processes, opening to new partners, or making personal changes inside the organization easier. All these aspects, but especially increasing customers’ satisfaction and the general morale of workers, should eventually lead to improvements in financial results, which is emphasized in ISO Standard No. 10014 [67].

One of the main features characterizing ISO Standard No. 9001 is its universality—its requirements can be used in organizations of different sizes, performing activities in various branches and having different defined organizational aims [68]. It also concerns schools; however, it is worth noting that the implementation of this standard, being prepared mainly for business goals, may sometimes be problematic in educational institutions [69]. Some authors even state that it only partially fulfills the requirements of the educational branch [70]. However, schools that managed to implement ISO Standard No. 9001 notice positive effects of introducing this system in different areas of their activity [71,72,73].

Quality management system within the educational area, based on ISO Standard No. 9001, was implemented in 11,202 organizations as of the end of year 2023 [64]. Due to the subject matter of this research, this fact seems to be of double importance: on the one hand, the system introduction should correspond to a quality increase in the organization; on the other hand, at the same time, it can be an example of the right attitude towards quality for teenagers attending school. As a result—according to presented in the previous part of this research work—it must serve as a crucial element of developing a pro-quality attitude in students. It can be achieved in a number of ways, starting from presenting students with a quality management system functioning and ending in engaging students in pro-quality actions [74]. Students’ participation in pro-quality actions may be realized as cooperation in preparing school internal regulations or collective solutions to quality-related problems in schools. ISO Standard No. 9001, due to its universal and rather general character, does not include elements directly corresponding to the ways of promoting quality or engaging clients—students should be treated as clients—in pro-quality actions [75]. In accordance with a definition presented in ISO Standard No. 9000, a client should be understood as ‘a person or organization that could or does receive a product or a service that is intended for or required by this person or organization’ [76] (p. 12). The standard distinguishes internal and external, direct, and indirect clients. The student of a school, even though from this point of view constituting a specific object [77], who does not purchase education like a product in a shop is absolutely included in its customers. All requirements of the standard, related to all customers should be applied to students. It is worth emphasizing that such an approach is also characteristic for schools that did not implement a quality management system [78,79].

The way these requirements are realized and the question if this realization will only aim at the literal fulfillment of necessity or conscious development of students’ pro-quality attitude depends on a school’s staff. However, the fact that a quality management system implemented in schools constitutes an important chance for developing students’ proper attitudes towards quality should be unquestionable. On the other hand, a system implemented in an improper way can have a negative effect on students’ attitudes towards quality. It can happen when students gain knowledge concerning the requirements of the standard and then observe that the school does not follow these regulations in practice. Cognitive dissonance and the awareness that it is possible to waive the realization of accepted policy may consequently lead to a lack of purposefulness and sense to undertake demanding actions to improve quality.

Moreover, provisions relating to communication with a client should include, among others, ‘providing information relating to products and services’ [17] (p. 10) and ‘obtaining customer feedback relating to products and services, including customer complaints’ [17] (p. 10). They are included in ISO Standard No. 9001 requirements. Requirements connected with the quality policy, which not only must be created but also must be communicated by an organization, are also introduced directly. The organization is also responsible for checking if the quality policy and related requirements have been properly understood and used. According to its definition, it accounts for the ‘intentions and direction of an organization as formally expressed by its top management’ [76] (p. 18) related to quality. In view of the above, it should be expected that in a school with the implemented quality management system, the knowledge about the document, and its contents will be shared by not only school workers but also students.

Taking into consideration the above-described subject matter, the author formulated the following research problem: What is the influence of the ISO 9001 quality management system implemented in a school on students’ attitudes towards quality? The author also made a research hypothesis, according to which quality management system implementation is not a sufficient factor to ensure the effective development of students’ pro-quality attitude.

In the following part of the article, the author presents the method of conducting the research and its results. The article ends with a discussion and conclusions.

5. Materials and Methods

The author established the influence of the ISO 9001 quality management system implemented in schools on students’ pro-quality attitude for the needs of hypothesis verification. It was performed by the means of data comparison. Data were collected in high schools with implemented systems and in schools in which there was no such system. In the course of research, the author used survey methodology, being—according to researchers’ opinion—an adequate instrument for attitude studies [80,81,82]. For the needs of research realization, the author intended to verify all three before presenting the elements of a pro-quality attitude, such as:

- I.

- Student’s knowledge about quality;

- II.

- The sense of purposefulness and relevance of a proper attitude towards quality in private life, as well as during the performance of work obligations;

- III.

- Developed habits of incorporating a proper attitude towards quality in private life, as well as during the performance of work obligations.

Research data have been collected by surveying a group of 1294 students from 16 high schools in Poland: 4 schools with an already implemented quality management system (239 students) and 12 schools that did not have that system (1055 students). The schools were randomly chosen for the research, from within the catalog of high schools, as well as from the catalog of schools additionally fulfilling the criterion of the implemented quality management system. The analysis of students subjected to this research allowed us to state that these are people of different sexes, attending classes on various levels, from schools situated in different locations (city/country). The possibility of filling out surveys only by students with certain results in education was eliminated. Whole, randomly chosen classes were subjected to research, without distinguishing only particular students. The research was supplemented with unstructured interviews with representatives of the teaching staff.

While establishing the number of schools with implemented quality management systems for this research, the author tried to reflect the share of such schools in the total number of high schools in Poland. The combined number of high schools in Poland over the last few years has slightly fluctuated. According to the latest data from the year 2023/2024, there were 6935 such schools [83]. There is a lack of detailed data reflecting the number of schools with implemented quality management systems. Formerly presented data from the ISO survey are limited to presenting the number of certified organizations in particular countries and branches. In the case of the educational branch, the entities include—apart from high schools—among others, primary schools, universities, training companies, or Continuing Education Centers. According to data from Poland, the system is implemented in 366 organizations in the educational branch. Assuming that all these organizations were secondary schools, 5.28% of the 6935 schools mentioned would have implemented QMS. In order to ensure the appropriate minimum representativeness, the author had to ensure that in the group of surveyed schools, the share of those with implemented QMS was not smaller. Within the research, the author surveyed students from four schools with implemented QMS, which constitutes 25.00% of the total number of researched schools. It considerably exceeds the mentioned indicator.

The research was performed in schools after the oral consent of principals, ensuring full anonymity of both the surveyed, as well as schools.

The questionnaire, according to adopted recommendations [84,85] included three main parts:

- (1)

- Introductory instructions with the aim of the research;

- (2)

- The main part including questions to respondents;

- (3)

- Respondents’ particulars allowing us to identify a respondent’s profile—their age, sex, type of school, and class level.

The questionnaire was designed to determine students’ attitudes towards quality. The questions included in it referred to each of the three elements of students’ pro-quality attitude. Separate questions concerned students’ knowledge of topics related to the issue of quality, their sense of justification for being guided by quality in their everyday lives, and the actual performance of their duties in accordance with quality criteria. This allowed not only for verification of the degree to which individual attitudes were formed but also for a later comparison of the answers given by people attending schools with implemented QMS and other schools.

The survey included filtering questions indicating the next questions to which the respondent should proceed after providing specific answers. This allowed for sending selected additional questions to people from both groups, including primarily those verifying the impact of the quality management system on students. The verification questions included in the survey also allowed for initial verification of the correctness of completing the questionnaires. This concerned, among others, the actual knowledge of the QMS by people who had previously declared it.

All research participants were assured of full anonymity concerning collected data, the aim of the research, the lack of research-related risk, as well as of the fact that collected data would be used exclusively for the needs of research with no possibility of identification.

6. Research Results

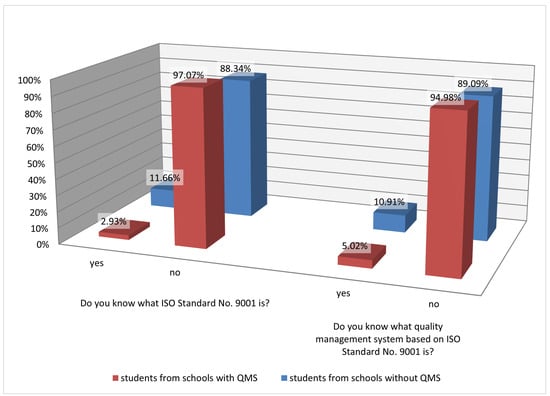

Firstly, the performed research allowed determining the level of students’ knowledge concerning ISO Standard No. 9001 and the quality management system based on this standard. As presented in Figure 3, 2.39% of the researched students from schools with implemented QMS confirmed their knowledge about ISO Standard No. 9001, and 5.02% of students knew what a quality management system according to ISO Standard No. 9001 was. The fact that these values are considerably lower than in the case of students from the rest of the schools is very important. A total of 11.66% of students in the first case and 10.91% in the second case, respectively, confirmed their knowledge.

Figure 3.

The structure of school students’ answers to questions concerning their knowledge of ISO Standard No. 9001 and quality management. Source: Own study.

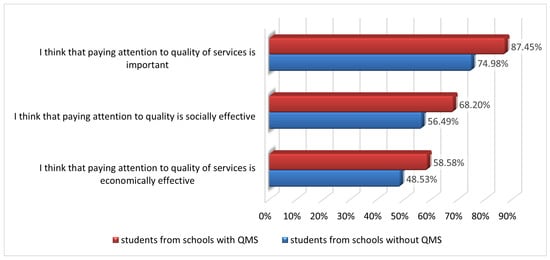

Verification of the second element of the three-component interpretation of the pro-quality issue, which is the sense of purposefulness of following quality rules in everyday life, has also been performed within the course of research. All surveyed students were asked to express their opinion on the importance of paying attention to the quality of offered services, as well as the efficiency of this phenomenon—both social and economic. As presented in Figure 4, in all three areas, the percentage of people convinced of the purposefulness of following quality rules was higher in the case of students attending schools with implemented quality management systems—on average by 11.41 percentage points.

Figure 4.

The structure of school students’ answers to questions concerning the sense of purposefulness of following quality rules. Source: Own study.

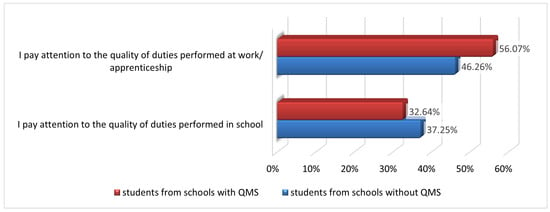

The surveyed people were asked about the importance of paying attention to the quality of performed actions at work and during school internships in order to verify the influence of the school on the third element of students’ pro-quality attitude, concerning following quality rules in everyday life. As presented in Figure 5, in the first area, a higher indicator of people paying attention to quality was observed among students attending schools with implemented quality management systems. However, in the second case, this indicator was higher in the second group of students.

Figure 5.

Structure of school students’ answers to questions related to paying attention to quality. Source: Own study.

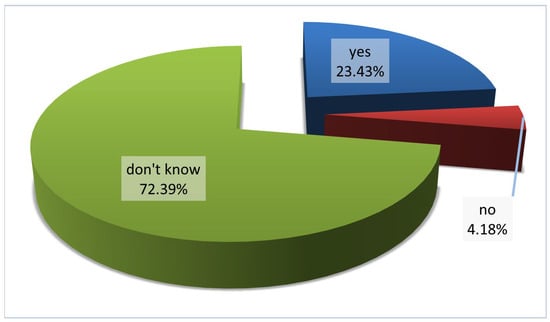

Part of the questions included in the survey was aimed at analysis of the implemented quality management system. Only students attending schools with implemented QMS were asked these questions. As collected data show, only 23.43% of students are familiar with the fact that their school has implemented this system. A total of 72.38% of students do not know if the system has been introduced in their schools, and 4.18% are sure that there is no such system in their schools (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The structure of answers received from students of schools with implemented QMS for the following question ‘Does your school have an ISO 9001 quality management system?’. Source: Own study.

One hundred percent of students who know that there is such system in their schools admit that they were not informed about the way it works in school.

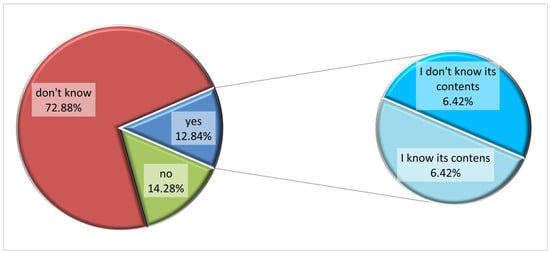

Only 12.84% of students from schools with implemented quality management systems know about the existence of a quality policy in their schools—one of the most important documents connected with QMS, also made public. In all, 72.88% of students do not know if their school has a quality policy and 14.28% stated definitely that there is no such document in their schools. Among the first indicated group—which includes people confirming the document’s existence—only half know its contents, that is 6.42% of the school students (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The structure of answers received from students of schools with implemented QMS for the following questions ‘Does your school have quality policy?’ and ‘Do you know your school’s quality policy?’. Source: Own study.

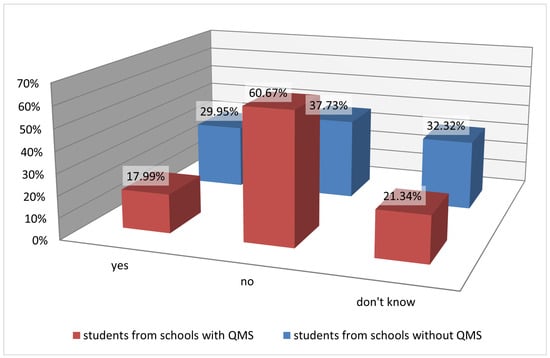

An organization with an implemented quality management system should check its customers’ satisfaction, and in the case of school—as it was previously stated—these are, among others, students. This group answered the question ‘Are there questionnaires checking students’ satisfaction with the quality of teaching in your school?’. In all, 60.67% of respondents answered ‘No’ and only 17.99% answered ‘Yes’ (Figure 8). Indicated values are significantly lower than those collected in other researched schools, in which these values were indicated, respectively, by 22.94 percentage points less frequently and by 11.96 percentage points more frequently.

Figure 8.

The structure of students’ answers to the question ‘Are there questionnaires checking students‘ satisfaction with the quality of teaching in your school?’. Source: Own study.

The indicator of answers for the same question collected from teachers seems to be interesting. According to this indicator, all sixteen schools realized questionnaires checking their students’ satisfaction with the quality of teaching.

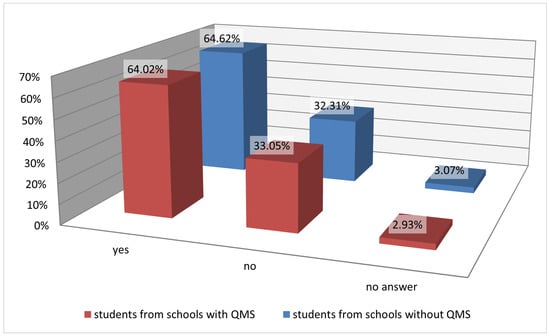

Due to the subject matter of this research, in the course of the study, attention was also paid to the quality of education in the schools that students attend, as well as to their opinions on this issue. The analysis of collected data allows the author to state that students of schools with implemented QMS and the rest of schools are interested in the quality of teaching to a comparable extent—positive answers were collected from 64.02% and 64.62% of the surveyed (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The structure of answers to the question ‘Do you pay attention to the quality of teaching in your school?’. Source: Own study.

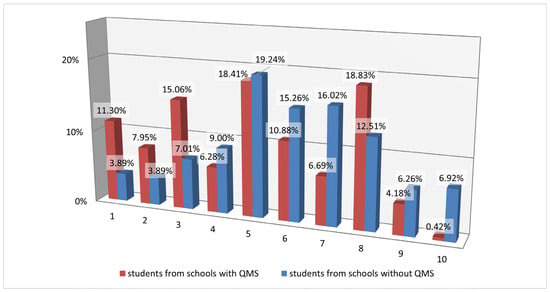

Interestingly enough, students attending schools with implemented QMS assess teaching quality more critically than students from the rest of the schools. As can be noticed in Figure 10, the students in the first case assessed their school using the lowest marks (on a ten-point scale: 1–2) and fewer high marks (9–10) than in the case of other schools. The average of all marks was also lower than in the case of schools with implemented quality management systems and reached 4.94 and in other schools 5.94 (Table 1).

Figure 10.

An assessment of teaching quality in researched schools proposed by students. Source: Own study.

Table 1.

The average of marks proposed by students within the area of teaching quality.

7. Discussion of Results and Conclusions

Data collected within the course of this research allowed the author to draw conclusions connected with the influence of the implemented quality management system according to ISO Standard No. 9001 on the pro-quality attitude of students.

- The number of students with knowledge of ISO Standard No. 9001 and related quality management systems appeared to be very low. The reason for this can be found in the lack of system conditions to convey knowledge concerning quality-related topics [57,86,87]. At the same time, the fact that the percentage of students possessing this knowledge is lower in the case of schools with implemented quality management systems seems to be surprising. It indicates untapped opportunities for schools to convey knowledge about both of these issues, even though in the case of the implemented system, it would be simpler and more effective due to the possibilities of presenting knowledge in practice also [88]. It could be performed, for example, through the presentation of ways of implementing particular requirements of the standard in practice or through attempts to engage students in perfecting the system, which additionally increases teaching effectiveness [89]. The issue discussed by Abrahams and Millar—the existence of situations in which practical education may, in spite of appearances, be less effective than theoretical [90]—should be also taken into consideration. The existence of a system as a ‘live’ training material, allowing for the use of analytical tools, would help to join both these forms of conveying knowledge, at the same time eliminating their rigid division, and due to QMS and Industry 4.0 complementary character, it would positively influence students’ preparation for future work in the modern economy [91]. This education could also take not only stationary forms but also blended learning opportunities [16].

- The vast majority of surveyed students have a sense of purposefulness in following quality rules in everyday life. Students attending schools with implemented quality management systems presented higher awareness of the discussed issue (subsequently by 12.47,11.71, and 10.05 percentage points) in all three researched areas (the essence of paying attention to the quality of offered services, social effectiveness of paying attention to quality, and economic effectiveness of paying attention to quality). These results correspond with answers given by students to the question concerning their interest in the issue of teaching quality, expressed by the vast majority of surveyed. However, this interest was independent of possessing QMS in school since in both types of schools, the indicator was very similar. It coincides with data presented by Billaiya, Malaiya, and Parihar, according to which students’ concern about the teaching quality increases [92]. Moreover, it is also consistent with observations made during the COVID-19 pandemic when online classes were a popular form of teaching. Before complications related to technical infrastructure interfering with participation in such classes, these were aspects concerning teaching quality (for example low quality of the educational environment, imprecise transfer of taught material, problems with understanding educational materials, and lower effectiveness of classes) that were the top list of problems indicated by students [93,94,95]. This interest of students in quality should be treated as the next reason to engage them in pro-quality actions in schools. At the same time, it proves that schools with QMS did not take the opportunity. While engaging students they could have influenced both, offered service and pro-quality attitude [42] (p. 28); [96] (p. 24, 25). The fact concerning the more critical assessment of teaching quality expressed by students of schools with QMS draws attention; however, finding the reasons for such a situation demands in-depth research.

- The surveyed students, contrary to their quite high awareness of quality issues, express less interest in following quality rules in everyday life, both while performing duties at work, in school, or during school internships. Collected answers do not indicate unambiguously the influence of the system on attitudes towards quality. Such ambiguity coincides with accessible research results, which show diversity in following the quality criterion by young people while making consumer decisions. Balance of both essence of quality and price [97], lack of significant influence of quality on their purchase decisions [98], and prioritizing the quality criterion over price are worth noting [99].

- A very low number of students attending schools with QMS are aware of the fact that their school has the system implemented. Consistent results were noted in the case of awareness of the fact that the school possessed a quality policy. It should be considered in two dimensions. On the one hand, it proved a lack of promoting the implemented system among the school society, including its customers—students. Taking into consideration the fact that the system implementation is usually related with presenting the certificate, information on the school’s webpage, exhibiting the quality policy, or appropriate labeling of all used documents (for example, different kinds of forms), the approach to these issues in researched schools requires in-depth analysis. The awareness of possessing QMS by an organization constitutes a starting point to engage customers and a higher value for them [100] (p. 12). As Dziedzic, Warmińska, and Wyrwa state, it is a key element of effective quality management, allowing for addressing their needs [101]. However, on the other hand, it emphasizes the lack of making use of a school-implemented quality management system to teach about quality: even though 23.43% of students know that their school has the system implemented, only 5.02% are familiar with the purpose and contents of this document. However, as the examples show, students can have considerable impact on school’s development in different aspects of its functioning [40,52,59]. It could be expected that in this case, their engagement in system’s processes, including, for example, perfecting the system and offered services and transmitting feedback through students, just as through customers, can bring measurable effects.

- The schools do not make use of possibilities connected with performing research checking customers’ satisfaction. This tool, which could be used for quality promotion and showing concern of the customer, is realized in schools in a way that brings students the lack of knowledge about this fact. The students play double role in school—on the one hand, they are school’s customers, and on the other hand, they are future suppliers of quality in their professional lives. When they are taught ensuring customer’s satisfaction, they will probably be more sensitive to this issue in the future, with the quality management system implementation where one of main rules is customer orientation [102]. Convincing to perform pro-quality actions, oriented at a customer, becomes more effective when the example comes from the top [103], in this case, from the school workers. However, these actions must be honest since apparent actions may be easily discovered and lead to adverse effects compared to what is expected. This is according to the requirements of the standard—coinciding strongly with its principle—leadership [104]. In order to achieve the promotional goal, surveying must be inseparably linked with clear information about its connections with teaching quality and, later, with feedback for students concerning research results and actions undertaken on that basis. Such information plays very important role for people to whom it is directed—even if it brings negative news [105]. Taking into consideration the fact that teachers from all schools stated that questionnaires checking students’ satisfaction are realized in schools, and only minority of students authenticated this information, the questions concerning the character of these questionnaires, whether they address real problems in schools and whether they help to plan further actions of school, stay open. Indicated discrepancy does not have to result from wrong answers given in a purposeful way by either of groups. It could be the effect of forgetting this fact by students or not matching questionnaires introduced in the course of teaching process with such aim. In this case, the analysis of the way questionnaires were realized in schools seems to be justified.

The above results allowed the author to determine and assess the influence of ISO 9001 quality management system implementation in schools on students’ pro-quality attitude. The analysis of collected data proved the hypothesis made by the author, according to which QMS implementation only is not enough to ensure effective pro-quality attitude development. Bearing in mind the three-component model of attitude, it is possible to consider a properly shaped pro-quality attitude in the case of possessing knowledge about quality, following quality criteria, and the need to pay attention to quality by students. This condition has not been realized, which proves the constructed hypothesis.

It is very significant information from the point of view of enterprises functioning in the era of Industry 4.0, a clear indication of the fact that the system of education must undertake additional actions aimed at developing proper attitudes towards quality in future labor market participants. The performed research suggests that, according to the above-presented model of students’ pro-quality attitude development, this process must be realized with the use of a number of elements influencing their approach. The quality management system itself, maintained without using its full potential, is not a factor ensuring effective development of students’ pro-quality attitude, consequently enabling them to prepare for functioning in sensitive Industry 4.0. It coincides with research results concerning school workers, according to which the implementation of a quality management system is not synonymous with changing their awareness concerning quality issues [106]. Therefore, it seems justified to develop students’ pro-quality attitude in many dimensions, encompassing not only the quality management system implementation but also including different areas: other elements related to the example coming from the school (2) (i.e., school workers’ pro-quality attitude (2-1), implemented Total Quality Management philosophy (2-2), a pro-quality attitude of tutors in the course of apprenticeship (2-3) and the use of quality instruments (2-5)), additional forms of quality promotion (4), and introduction of content concerning the quality issues in the course of classes (3), as well as affecting students through social and cultural factors (1). In this context, it is important to note that individual elements may affect students and their attitudes towards quality in a variety of ways. While there are many known cases of their positive influence [26,42,45,49,51], some of them may have a negative impact on students’ attitudes towards quality [33]. Awareness of this may require specific compensation of the impact of some factors with others. This issue becomes even more important when the necessity to meet Industry 4.0 requirements is taken into consideration. In Industry 4.0, the precision of work, meeting deadlines, and skills to use modern technologies become more intensive [107].

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The research results provide a contribution to the extension and analysis of the obtained results, in terms of the impact of the school on shaping the attitude of students towards quality, depending on the time that has passed since the implementation of the system in the school, the degree of formalization of the system, and the involvement of school staff in pro-quality activities. It is justified to extend them also to other groups—teachers, principals, and administrative staff, as well as to include them in other stages of education. It also seems justified to verify the reasons for a more rigorous assessment of the level of teaching quality given by students in schools with the implemented system.

The conducted research has also revealed other areas that require in-depth analysis. These include communication with students and partnerships with students, as a specific type of customer in the education market. Given the high interest of students in the issue of quality observed in this research, it also seems justified to implement pilot activities aimed at engaging students in comprehensive pro-quality activities, closely linked to the implementation of research analyzing their effects.

The performed research encompassed a limited number of schools located in one country. Even though, the author made efforts to ensure randomness of respondents, as well as include the right number of indicators of schools with implemented quality management systems, the realization of in-depth research, including a higher number of schools situated in more countries, is recommended.

At the same time, it is worth noting that notwithstanding the collected results, the author does not undertake to assess the correctness of quality management systems introduced in schools. Collected data allow us to assess only fragments of the system, which is insufficient for holistic assessment and was not the aim of this research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks all participants in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rowlands, H.; Milligan, S. Quality-driven Industry 4.0. In Key Challenges and Opportunities for Quality, Sustainability and Innovation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2021; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, M.; Tonelli, F. Quality management in the industry 4.0 era. In Proceedings of the Summer School Francesco Turco, Palermo, Italy, 12–14 September 2018; pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypek, A.; Skrzypek, E. Jakość 4.0 w Warunkach Czwartej Rewolucji Przemysłowej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej: Lublin, Poland, 2023; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, R.R.; Abu Talib, M.; Dweiri, F.; Roman, J. An Artificial Intelligence (AI) Framework to Predict Operational Excellence: UAE Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, L.; Titu, M.A.; Oprean, C. The quality and the management of human resources quality within the knowledge based economy and organization. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Scientific Conference SAMRO, Sibiu, Romania, 14–16 October 2016; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Akturk, C.; Talan, T.; Cerasi, C.C. Education 4.0 and University 4.0 from Society 5.0 Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2022 12th International Conference on Advanced Computer Information Technologies (ACIT), Ruzomberok, Slovakia, 26–28 September 2022; pp. 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidbauer, H.J. The Effect of the Use of the Ohio Baldrige Initiative Training in the Pilot Districts on the Sustained Use of Quality Tools by Classroom Teachers. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA, 2010; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy, M.; Mani, C. Company Training, Initial Training: Initial In-Company Vocational Training in India: Implications and Challenges for Indian Companies. In India: Preparation for the World of Work; Pilz, M., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulissen, D.; De Grip, A.; Fouarge, D.; Künn-Nelen, A. Employers’ willingness to invest in the training of temporary versus permanent workers: A discrete choice experiment. Labour Econ. 2023, 84, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales, D.P.; Valero, F.A.; García, A.B. Industry 4.0: A Classification Scheme. In Closing the Gap Between Practice and Research in Industrial Engineering. Lecture Notes in Management and Industrial Engineering; Viles, E., Ormazábal, M., Lleó, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleko, A.T.; Kamsu-Foguem, B.; Ngouna, R.H.; Tongne, A. Artificial intelligence and real-time predictive maintenance in industry 4.0: A bibliometric analysis. AI Ethics 2022, 2, 553–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotov, O.; Aleksieva-Petrova, A. Data-Driven Prediction Model for Analysis of Sensor Data. Electronics 2024, 13, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Beckmann, M. Digital technologies and performance incentives: Evidence from businesses in the Swiss economy. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 2025, 161, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkirov, A.M. Transforming higher education in emerging markets through integrated TQM practices. Int. Sci. J. 2025, 4, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, D.; Martinez, M.; Yakir, M.; Gray, C. Implementing a lean management system in primary care: Facilitators and barriers from the front lines. Qual. Manag. Healthc. 2015, 24, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moica, S.; Gherendi, A.; Veres, S.; Moica, T. The Integration of the Blended Learning Concept into Employee Training as a Factor in Shifting Mentalities towards the Industry 4.0 Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 8th International Conference on Industrial Technology and Management (ICITM), Cambridge, UK, 2–4 March 2019; pp. 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO Standard no. 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Wolniak, R.; Olkiewicz, M. The Relations Between Safety Culture and Quality Culture. Syst. Saf. Hum.-Tech. Facil.-Environ. 2019, 1, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinandhita, G.; Latief, Y. Implementation strategy of total quality management and quality culture to increase the competitiveness of contractor companies in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 930, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfirman; Sutawijaya, A.H. The Effect of Total Quality Management Implementation on Quality Performance through Knowledge Management and Quality Culture as Mediating Variable at PT XYZ. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2022, 7, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, E. Total Quality Management in Education, 3rd ed.; Kogan Page Ltd.: London, UK, 2002; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ilieș, I.; Sălăgean, H.C.; Bâlc, B. Quality culture: Essential component of TQM. Manag. Chall. Contemp. Soc. 2015, 8, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, P. An Investigational Study on Factors of Quality Culture in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Sectors. Shanlax Int. J. Manag. 2022, 9, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka-Ortyl, A. The impact of organizational culture for company’s innovation strategy. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2019, 3, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, E.W. Organizational culture, TQM, and business process reengineering: An empirical comparison. Team Perform. Manag. 1999, 5, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Chang, W.-J.; Wu, C.-C. Exploring TQM-innovation relationship in continuing education: A system architecture and propositions. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2010, 21, 14783363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel-Uz-Zaman, A.; Anjalin, U. Implementing Total Quality Management in Education: Compatibility and Challenges. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 4, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R. Revisiting a TQM research project: The quality improvement activities of TQM. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2008, 19, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, H.; Khan, K.I.A.; Ullah, F.; Tahir, M.B.; Alqurashi, M.; Alsulami, B.T. Key factors for implementation of total quality management in construction Sector: A system dynamics approach. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, G.K. Measuring Business Excellence; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- European University Association. Quality Culture in European Universities: A Bottom-up Approach. Report on the Three Rounds of the Quality Culture Project 2002–2006; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, U.D. Understanding quality culture. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2009, 17, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychalski, B. Socio-cultural factors shaping the attitude of Generation Z and Generation Alpha youth towards quality. J. Sustain. Dev. Transp. Logist. 2023, 8, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, H.; Bliemel, M.; Nassiri, N.; Toze, S.; Peet, L.M.; Banerjee, R. A review of models of information seeking behavior. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth HCT Information Technology Trends (ITT), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, 20–21 November 2019; pp. 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, D.E. Information seeking in the age of the data deluge. Libr. Hi Tech. News 2019, 36, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillard, L.L.; Ha, Y. Bates’ Berrypicking Model (1989, 2002, 2005). In Information Retrieval and Management: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; I. Management Association, Ed.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A. Unpacking your literature search toolbox: On search styles and tactics. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2008, 25, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, M.J. The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Rev. 1989, 13, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T. Quality in learning. Romancing the Journey. In Exemplary Institute. Proceedings of the Annual Conference; Native American Scholarship Fund, Inc.: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1998; pp. 7–57. [Google Scholar]

- Main, J. Quality Wars: The Triumphs and Defeats of American Business; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden, G.; Vos, J. The New Learning Revolution, 3rd ed.; Network Educational Press Ltd.: Stafford, UK, 2005; p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, S.; Menzel, S. Study of School-to-Work Reform Initiatives. Volume II: Case Studies; Studies of Education Reform Series; Academy for Educational Development, National Institute for Work and Learning: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, K. Applying Total Quality Management Principles to Secondary Education. Mt. Edgecumbe High School, Sitka, Alaska; Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory: Portland, OR, USA, 1994; Available online: https://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/ApplyingQualityManagementPrinciples.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Evans, J.R.; Lindsay, W.M. Managing for Quality and Performance Excellence; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- King, M.; Kovacs, J. Enough About WHAT School Excellence Looks Like! Now, What About the “HOW TO”? Quality Learning Australia Pty Ltd.: North Melbourne, Australia, 2007; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- King, M. Getting better together: Quality improvement theory and tools that actively enable collaboration for learning and success. In Proceedings of the NZEALS Conference 2016: Leading Social Justice in Education, Dunedin, New Zealand, 20–22 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- King, M.; Kovacs, J. Improving Our System of Learning: Redefining the Job of Everyone in Education. Keynote Paper. North Coast Region Quality Teaching Conference. 2009. Available online: http://www.qla.com.au/pathtoitems/Improving%20Our%20Systems%20of%20Learning.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Quality Learning Australasia. Resources. Examples. (n.d). Available online: http://www.qla.com.au/Examples/2 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Smith, K.; Koalaty Kid. A Student Focused Initiative to Improve the Quality of Education. (n.d). Available online: http://www.qualitydigest.com/aug02/articles/07_article.shtml (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Quality Digest. Koalaty Kid Keeps Growing and Growing. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.qualitydigest.com/june00/html/news.html (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Turska, L. Kształtowanie Postawy Współodpowiedzialności Uczniów za Szkołę z Wykorzystaniem Idei Edukacji Projakościowej; Wydawnictwo i Pracownia Poligraficzna Łódzkiego Centrum Doskonalenia Nauczycieli i Kształcenia Praktycznego: Łódź, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Turska, L. Edukacja Projakościowa Uczniów w Procesie Doskonalenia Pracy Szkoły; Wydawnictwo i Pracownia Poligraficzna Łódzkiego Centrum Doskonalenia Nauczycieli i Kształcenia Praktycznego: Łódź, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mądrzycki, T. Psychologiczne Prawidłowości Kształtowania Się Postaw; Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 1977; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing, 17th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2018; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, B.; Uzunboylu, H. Developing an attitude scale towards distance learning. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 41, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, E. Ranga jakości w społeczeństwie wiedzy. Probl. Jakości 2006, 38, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Spychalski, B. Holistic Education for Sustainable Development: A Study of Shaping the Pro-Quality Attitude of Students in the Polish Educational System. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozberk, O.; Sharma, R.C.; Dagli, G. School Teachers’ and Administrators’ Opinions about Disability Services, Quality of Schools, Total Quality Management and Quality Tools. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2019, 66, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.D. The Koalaty Kid process in action. In ASQ’s 52nd Annual Quality Congress Proceedings; American Society for Quality: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1998; pp. 466–732. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, K.; Roszak, M. Quality culture—A contemporary challenge in the approach to management systems in organizations. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2021, 105, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.; Kehoe, D. Factors affecting the implementation and success of TQM. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1995, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J.; Ullrank, P. Total quality management as a cultural phenomenon. Qual. Manag. J. 2004, 11, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonza’lez, T.F.; Guille’n, M. Leadership ethical dimension: A requirement in TQM implementation. TQM Mag. 2002, 14, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization of Standardization. The ISO Survey of Management System Standard Certifications—2023. Available online: https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Lushi, I.; Mane, A.; Kapaj, I.; Keco, R. A Literature Review on ISO 9001 Standards. Eur. J. Bus. Econ. Account. 2016, 4, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Spychalski, B. Threats for ISO 9001. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2022, 3, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO Standard no. 10014:2021; Quality Management Systems. Managing an Organization for Quality Results Guidance for Realizing Financial and Economic Benefits. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Zimon, D.; Madzik, P.; Sroufe, R. The Influence of ISO 9001 & ISO 14001 on Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Textile Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, A.J.; Melão, N.F. The impacts and success factors of ISO 9001 in education. Experiences from Portuguese vocational schools. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2012, 29, 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyova, O.; Horokhova, M.; Iliichuk, L.; Tverezovska, N.; Drachuk, O.; Artemchuk, L. ISO Standards as a Quality Assurance Mechanism in Higher Education. Rev. Românească Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2022, 14, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cruz, F.J.; Rodríguez-Mantilla, J.M.; Fernández-Díaz, M.J. Assessing the impact of ISO: 9001 implementation on school teaching and learning processes. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2019, 27, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mantilla, J.M.; Martínez-Zarzuelo, A.; Fernández-Cruz, F.J. Do ISO:9001 standards and EFQM model differ in their impact on the external relations and communication system at schools? Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 80, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cruz, F.J.; Rodríguez-Mantilla, J.M.; Fernández Díaz, M.J. Impact of the application of ISO 9001 standards on the climate and satisfaction of the members of a school. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 34, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtuwene, S.J.; Lahinta, F.C.; Munaiseche, M.; Mengerongkonda, C.; Ngosa, J.; Rompas, R.; Medau, E.; Lumeta, A.; Angkow, S. Implementation of ISO 9001 Standard in Increasing the Quality of College Students. Interdiscip. J. Adv. Res. Innov. 2023, 1, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wibowo, F.I.S. ISO 9001 and IWA-2 Quality Management System in Education. J. Educ. Innov. Curric. Dev. 2023, 1, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- ISO Standard no. 9000:2015; Quality Management Systems—Fundamentals and Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Muncy, J.A. The Orientation Evaluation Matrix (OEM): Are Students Customers or Products? Mark. Educ. Rev. 2008, 18, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, S.M. Developing relationships with school customers: The role of market orientation. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, H. Impact of Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction: A Case Study in Educational Institutions. ADPEBI Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanur, J.M. Questions About Questions: Inquiries into the Cognitive Bases of Surveys; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, K.A.; Johnson, F.R.; Maddala, T. Measuring what people value: A comparison of “attitude” and “preference” surveys. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 37, 1659–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherdoost, H. What Is the Best Response Scale for Survey and Questionnaire Design; Review of Different Lengths of Rating Scale/Attitude Scale/Likert Scale. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2019, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Urząd Statystyczny w Gdańsku. Oświata i Wychowanie w Roku Szkolnym 2023/2024 (Wyniki Wstępne). Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/edukacja/edukacja/edukacja-w-roku-szkolnym-20232024-wyniki-wstepne,21,2.html (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Podgórski, R.A. Metodologia Badań Socjologicznych. In Kompendium Wiedzy Metodologicznej dla Studentów; Oficyna Wydawnicza Branta: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2007; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Gruszczyński, L.A. Kwestionariusze w Socjologii. Budowa Narzędzi do Badań Surveyowych; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2001; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, K.; Metrejean, C.; Schweitzer, K.; Cooley, J.; Warholak, T. Quality Improvement and Safety in US Pharmacy Schools. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, T. Attitude and Preference of Rehab Sciences Students on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Education. Pak. J. Rehabil. 2021, 10, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-Y.; Ye, J.-H. The Effectiveness of Inquiry and Practice During Project Design Courses at a Technology University. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 859164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munna, A.S.; Kalam, M.A. Teaching and learning process to enhance teaching effectiveness: A literature review. Int. J. Humanit. Innov. 2021, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I.; Millar, R. Does Practical Work Really Work? A study of the effectiveness of practical work as a teaching and learning method in school science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2008, 30, 1945–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambare, P.; Meshram, C.; Lee, C.-C.; Ramteke, R.J.; Imoize, A.L. Performance Measurement System and Quality Management in Data-Driven Industry 4.0: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billaiya, R.; Malaiya, S.; Parihar, K.S. Impact of socio economic trends on students in quality education system. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2017, 1, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Anwar, K. Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ perspectives. J. Pedagog. Sociol. Psychol. 2020, 2, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efriana, L. Problems of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic in EFL classroom and the solution. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Lit. 2021, 2, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanto, A. University Students Online Learning System during COVID-19 Pandemic: Advantages, Constraints and Solutions. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 570–576. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, D.P.; Cleary, B.A. Orchestrating Learning with Quality; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1995; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Marcellyna, R.; Usman, O. The Influence of Lifestyle, Price, and Product Quality on Make Up Product Purchase Decisions in Students. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincencia, M.; Christiani, N. The Effect of Product Quality, Price, and Promotion toward Students’ Purchase Decision for Telkomsel Products. Rev. Manag. Entrep. 2021, 5, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulida, R.A.; Sudarman, S.; Sutrisno, S. The Influence of Price and Service Quality on the Decision to Purchase of Reference Books in Students of Economics Education Program 2020–2021. Educ. Stud. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochomo, D.O. The Effect of ISO 9001 Certification on Non-Financial Performance in the Local Authorities Provident Fund as Perceived by the External Customers. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Dziedzic, S.; Warmińska, A.; Wyrwa, D. Perspectives of the analysis of organisation’s context in the light of the ISO 9001:2015 standard and the subject literature. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2023, 181, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviantoro, R.; Maskuroh, N.; Santoso, B.; Abdi, M.N.; Fahlev, M.; Pramono, R.; Purwanto, A.; Purba, J.T.; Munthe, A.P. Did Quality Management System ISO 9001 Version 2015 Influence Business Performance? Evidence from Indonesian Hospitals. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, K.N.; Goolsby, J.R.; Arnould, E.J. Implementing a Customer Orientation: Extension of Theory and Application. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R. Leadership in ISO 9001:2015. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2019, 133, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piezunka, H.; Dahlander, L. Idea rejected, tie formed: Organizations’ feedback on crowdsourced ideas. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 503–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltori, P.F.S.; Rampasso, I.S.; Martins, V.W.B.; Anholon, R.; Silva, D.; Pinto, J.S. Analysis of ISO 9001 certification benefits in Brazilian companies. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 1614–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]