Effects of Speech Level Shift Tested by a Non-Task-Oriented Dialog System on Text Chat Dialog with Users in Japanese: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Politeness Theory and Speech Level Shift

2.2. Effects of Speech Level and Politeness on Chatbot

3. Methods

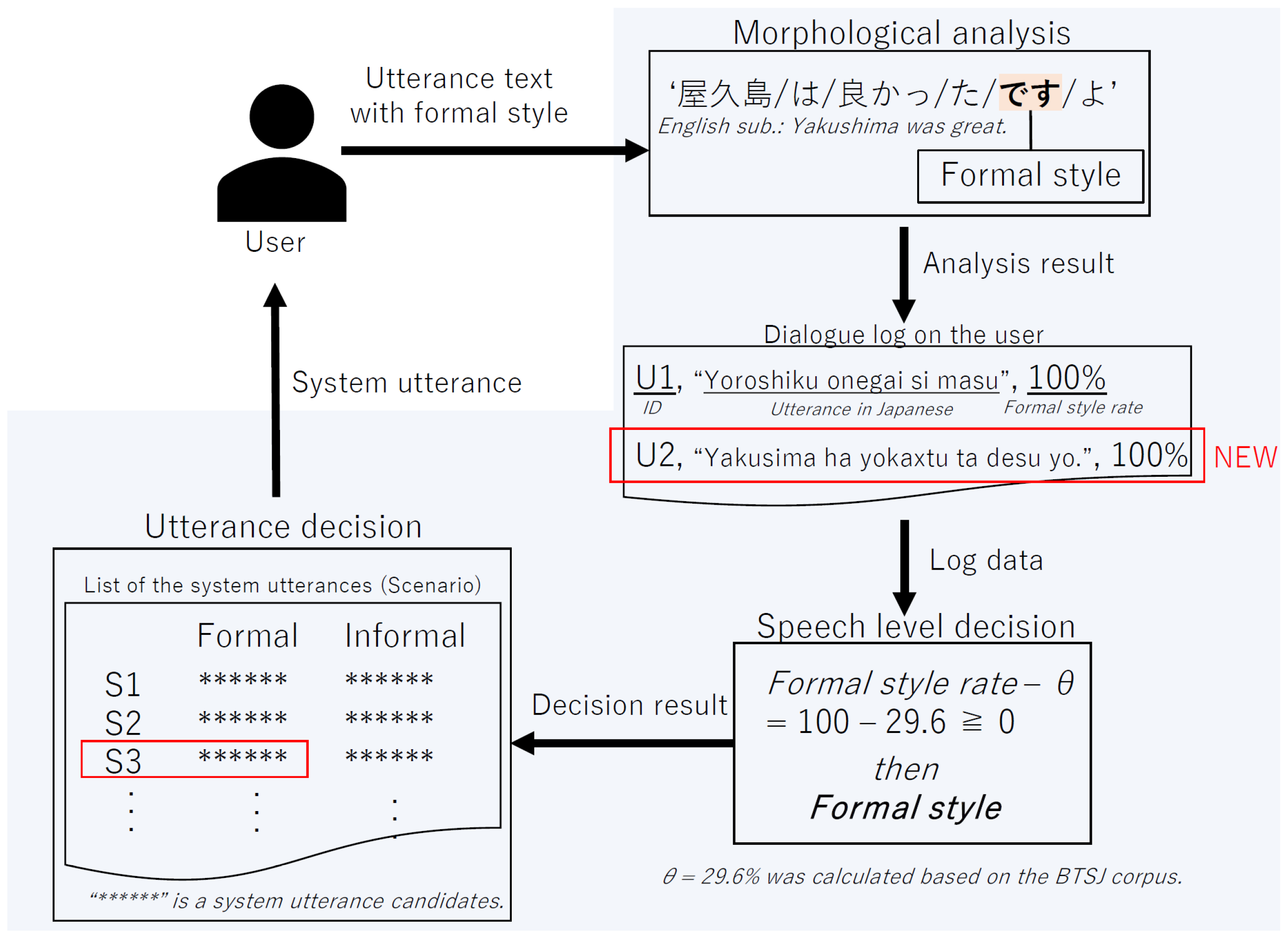

3.1. Dialog System with Speech Level Control

- The user and dialog system are meeting for the first time and are of the same generation.

- D and P are even.

| System Profile | Dialog System Developed for Ages 20 to 30 |

|---|---|

| User profile | Age: 20 to 30, job: office worker |

| Place/Time | Own home/free time |

| Topic | Travel |

| Background | The dialog system is a communication system that runs on an anonymous text chat service. The user likes to travel and one day finds a dialgoue system on the chat service that is also interested in travel and decides to speak to the system regarding this common interest. |

3.2. Experimental Dialog Rules

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Outline

- Shifting speech level condition (males: 28, females: 18; average age: 41.3, S.D.: 10.0, max: 66, min: 22);

- Formal style condition (males: 28, females: 20; average age: 39.3, S.D.: 9.5, max: 56, min: 20);

- Informal style condition (males: 24, females: 16; average age: 42.3, S.D.: 11.7, max: 70, min: 24).

4.2. Procedure

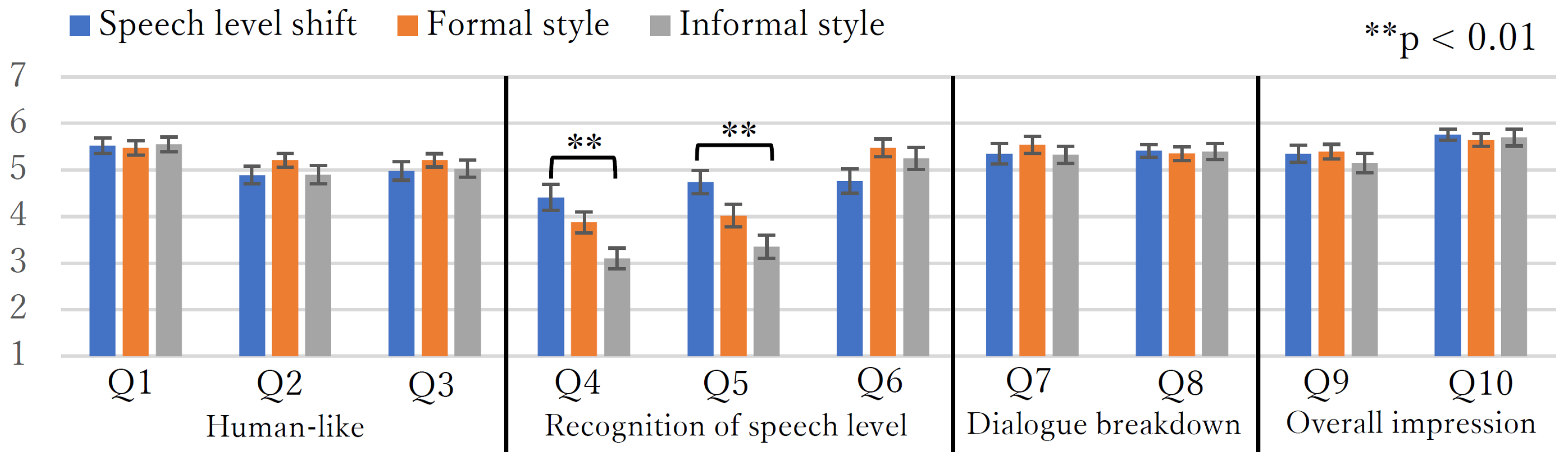

- Q1: The dialog system behavior was like a human being.

- Q2: The dialog system behaved in such a way that it maintained an appropriate social distance from me.

- Q3: The utterances of the dialog system considered the social relationship with me.

- Q4: There was a change in the wording of the dialog system (e.g., formal or informal style).

- Q5: I felt that the utterances of the dialog system were a mixture of formal and informal styles.

- Q6: I decided on my own wording with the wording of the dialog system in mind.

- Q7: The dialog with the dialog system was not broken down.

- Q8: The sentence endings of the dialog system were appropriate for the aforementioned situations (e.g., age and relationship between the user and system).

- Q9: The dialog with the dialog system was enjoyable.

- Q10: The dialog system was approachable.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.4. Results

- Human-like: 0.72 (0.10);

- Recognition of speech level: 0.77 (0.07) (without Q6), 0.40 (0.07) (include Q6);

- Dialog breakdown: 0.67 (0.11);

- Overall impression: 0.81 (0.09).

5. Discussion

5.1. User Impressions of Text Dialog System

5.2. Promotion of Speech Level Shift

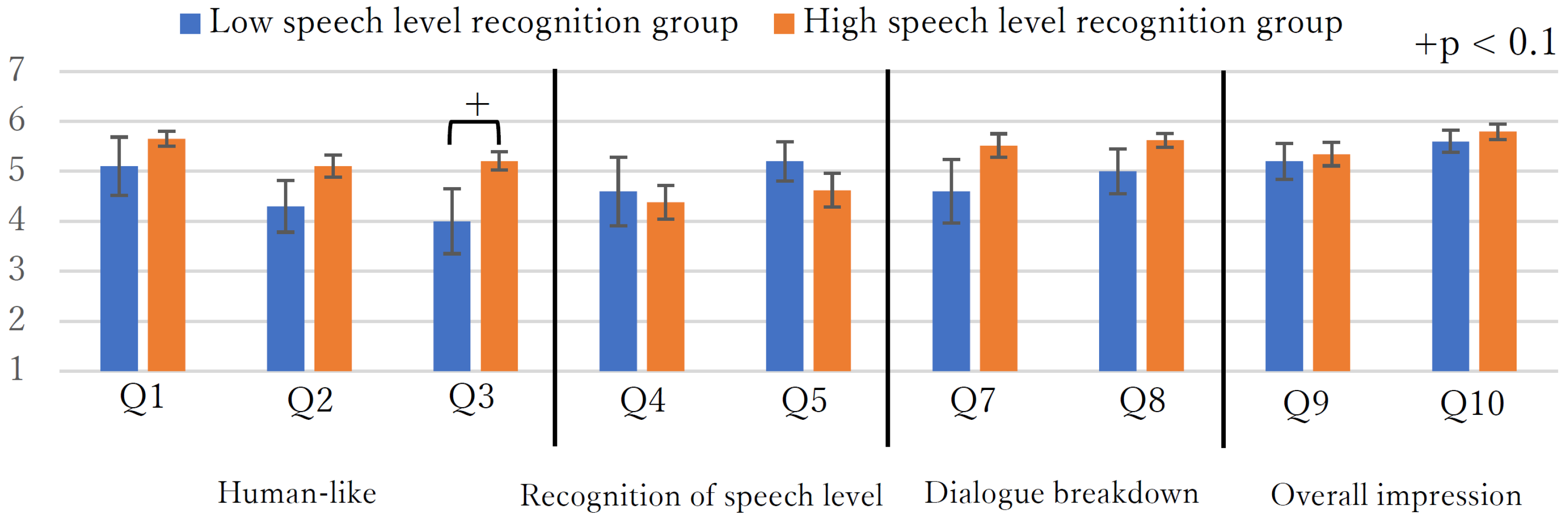

5.3. Speech Level Recognition and Users’ Impressions

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apple. Siri. Available online: https://www.apple.com/jp/siri/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Wu, X.; Ito, K.; Iida, K.; Tsuboi, K.; Klyen, M. Rinna: Zyosikousei zinkou tinou. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Second Annual Meeting of the Association for Natural Language Processing, Sendai, Japan, 8–10 March 2016; pp. 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Takiura, M. Honorifics seen from politeness, politeness seen from honorifics: An overview focusing on their pragmatic relativity. Jpn. J. Lang. Soc. 2008, 11, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Usami, M. On styles in Japanese language: Focusing on ’Speech-Level Shift’ in Japanese conversational discourse. Jpn. J. Lang. Soc. 2015, 18, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D.; Tanaka, T.; Kanamori, H.; Yoshihara, Y.; Fujikake, K. Should a driving support agent provide explicit instructions to the user? Video-based study focused on politeness strategies. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction, Virtual Event, 9–11 November 2021; pp. 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D.; Shigemitsu, Y.; Usami, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kanamori, H.; Yoshihara, Y.; Fujikake, K. Influence of Social Distance Expressed by Driving Support Agent’s Utterance on Psychological Acceptability. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 526942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Or, E.; Regev, T.; Shaviv, P.; Tractinsky, N. Towards a sociolinguistics-based framework for the study of politeness in human-computer interaction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.09901. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D.; Shigemitsu, Y. Improving relationships based on positive politeness between humans and life-like agents. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction, Bielefeld, Germany, 17–20 October 2017; pp. 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Johnson, W.L. The politeness effect in an intelligent foreign language tutoring system. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 23–27 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, M.; Ziadee, M.; Sakr, M. Effects of politeness and interaction context on perception and experience of HRI. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Robotics, Bristol, UK, 27–29 October 2013; pp. 531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey, C.; Fussell, S.R.; Kiesler, S. How a robot should give advice. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Tokyo, Japan, 3–6 March 2013; pp. 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama, L.; Groom, V.; Nass, C. I’m sorry, Dave: I’m afraid I won’t do that: Social aspects of human-agent conflict. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; pp. 2099–2108. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, V.; Takayama, L. Help me please: Robot politeness strategies for soliciting help from humans. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 4945–4955. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.G.; Lee, K.M.; Ryu, S.H. Vehicle politeness in driving situations. Future Internet 2019, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Lee, K.M. Polite speech strategies and their impact on drivers’ trust in autonomous vehicles. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtgraves, T.M.; Ross, S.J.; Weywadt, C.R.; Han, T.L. Perceiving artificial social agents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 2163–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, K.; Madaan, R.; Shukla, J. Effect of polite triggers in chatbot conversations on user experience across gender, age, and personality. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 August 2021; pp. 813–819. [Google Scholar]

- Firdaus, M.; Shandilya, A.; Ekbal, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Being polite: Modeling politeness variation in a personalized dialog agent. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2022, 10, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Hudeček, V.; Dušek, O. Polite Chatbot: A Text Style Transfer Application. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Student Research Workshop, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2–4 May 2023; pp. 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Zhang, H.; Xing, X.; Duan, Y. Appreciation vs. apology: Research on the influence mechanism of chatbot service recovery based on politeness theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Levinson, S.C. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Usami, M. Politeness in Japanese dyadic conversations between unacquainted people: The influence of power asymmetry. In Proceedings of the 10th World Congress of Applied Linguistics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–14 August 1993; pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Usami, M. Politeness and Japanese Conversational Strategies: Implications for the Teaching of Japanese. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ide, S. Formal forms and discernment: Two neglected aspects of universals of linguistic politeness. Multilingua 1989, 8, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, Y.; Chiba, Y.; Nose, T.; Ito, A. Improving user impression in spoken dialog system with gradual speech form control. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual SIGdial Meeting on Discourse and Dialogue, Melbourne, Australia, 12–14 May 2018; pp. 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Fazil, M.; Imoize, A.L.; Alabduallah, B.I.; Albahlal, B.M.; Alajlan, S.A.; Almjally, A.; Siddiqui, T. Transformer Architecture-Based Transfer Learning for Politeness Prediction in Conversation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Firdaus, M.; Ekbal, A. GenPADS: Reinforcing politeness in an end-to-end dialogue system. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, K.; Priya, P.; Ekbal, A. Help me heal: A reinforced polite and empathetic mental health and legal counseling dialogue system for crime victims. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Limassol, Cyprus, 5–8 June 2023; Volume 37, pp. 14408–14416. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, P.; Firdaus, M.; Ekbal, A. A multi-task learning framework for politeness and emotion detection in dialogues for mental health counselling and legal aid. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Priya, P.; Ekbal, A. PAL to lend a helping hand: Towards building an emotion adaptive polite and empathetic counseling conversational agent. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 12254–12271. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, A.K.; Upadhyaya, A.; Holzer, A. ChatGPT in Healthcare: Exploring AI Chatbot for Spontaneous Word Retrieval in Aphasia. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Virtual Event, 23–27 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ribino, P. The role of politeness in human–machine interactions: A systematic literature review and future perspectives. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 445–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y. Reexamination of the universality of face: Politeness phenomena in Japanese. J. Pragmat. 1988, 12, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usami, M. Discourse politeness in Japanese conversation: Some implications for a universal theory of politeness. Jpn. Lang. Lit. 2002, 38, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Usami, M. BTSJ-Japanese Natural Conversation Corpus with Transcripts and Recordings. NINJAL Institute-Based Projects: Multiple Approaches to Analyzing the Communication of Japanese Language Learners; National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics: Tachikawa, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D.; Shigemitsu, Y.; Usami, M.; Tanaka, T.; Kanamori, H.; Yoshihara, Y.; Fujikake, K. Proposal of driving support agent which speak based on politeness theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction 2019, Gipuzkoa, Spain, 25–28 June 2019; Volume 11596. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, N.; Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D. Evaluation of dialogue systems with different end of sentences using Seq2Seq model. J. Jpn. Soc. Fuzzy Theory Intell. Inform. 2020, 32, 523–527. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D.; Usami, M. A politeness control method for conversational agents considering social relationships with users. In Proceedings of the Advances in Artificial Intelligence-Selected Papers from the Annual Conference of Japanese Society of Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 8–11 June 2021; pp. 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Iwashita, M.; Katagami, D. Psychological effects of compliment expressions by communication robots on humans. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Higashino, K.; Kimoto, M.; Iio, T.; Fujita, K. Is Politeness Better than Impoliteness? Comparisons of Robot’s Encouragement Effects Toward Performance, Moods, and Propagation. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2023, 15, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MeCab. Available online: https://taku910.github.io/mecab/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Higashinaka, R.; Funakoshi, K.; Inaba, M.; Tsunomori, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Aakama, R.; Usami, M.; Kawabata, Y.; Mizukami, M. The dialogue system live competition 2. JSAI Tech. Rep. SIG-SLUD 2019, 87, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Higashinaka, R.; Minato, T.; Sakai, K.; Funayama, T.; Nishizaki, H.; Nagai, T. Spoken dialogue system development at the dialogue robot competition. J. Acoust. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 77, 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Telegram. Available online: https://telegram.org/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Bartneck, C.; Kulić, D.; Croft, E.; Zoghbi, S. Measurement Instruments for the Anthropomorphism, Animacy, Likeability, Perceived Intelligence, and Perceived Safety of Robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2009, 1, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Heerink, M.; Kröse, B.; Evers, V.; Wielinga, B. Assessing Acceptance of Assistive Social Agent Technology by Older Adults: The Almere Model. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2010, 2, 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Higashinaka, R.; D’Haro, L.F.; Shawar, A.; Bayan, B.; Banchs, R.; Funakoshi, K.; Inaba, M.; Tsunomori, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Sedoc, J. Overview of the dialogue breakdown detection challenge 4. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Workshop on Spoken Dialogue Systems Technology, Syracuse, Italy, 24–26 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schmider, E.; Ziegler, M.; Danay, E.; Beyer, L.; Bühner, M. Is It Really Robust? Methodology 2010, 6, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Harwell, M.R.; Rubinstein, E.N.; Hayes, W.S.; Olds, C.C. Summarizing Monte Carlo Results in Methodological Research: The One- and Two-Factor Fixed Effects ANOVA Cases. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1992, 17, 315–339. [Google Scholar]

- Blanca, M.; Alarcón, R.; Arnau, J.; Bono, R.; Bendayan, R. Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option? Psicothema 2017, 29, 552–557. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.B.; Forsythe, A.B. The Small Sample Behavior of Some Statistics Which Test the Equality of Several Means. Technometrics 1974, 16, 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Open AI. ChatGPT. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Makany, T.; Roh, S.; Hara, K.; Hua, J.M.; Goh Si Ying, F.; Teh Yang Jie, W. Beyond anthropomorphism: Unraveling the true priorities of chatbot usage in SMEs. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 19–21 July 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, D.C. The Intentional Stance; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, B.; Nass, C. The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People And Places; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Luger, E.; Sellen, A. “Like having a really bad PA”: The gulf between user expectation and experience of conversational agents. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 5286–5297. [Google Scholar]

- Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, C.; Sudhof, M.; Jurafsky, D.; Leskovec, J.; Potts, C. A computational approach to politeness with application to social factors. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL, Sofia, Bulgaria, 4–9 August 2013; pp. 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, T.; Bansal, M. Polite dialogue generation without parallel data. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, T. Cultural differences in social acceptance of robots. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Lisbon, Portugal, 28 August 2017–1 September 2017; pp. 534–538. [Google Scholar]

- Bartneck, C.; Suzuki, T.; Kanda, T.; Nomura, T. The influence of people’s culture and prior experiences with Aibo on their attitude towards robots. AI Soc. 2007, 21, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Koda, T.; Takeda, Y. Perception of culture-specific gaze behaviors of agents and gender effects. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction, Southampton, UK, 15–18 December 2018; pp. 138–143. [Google Scholar]

| Attributes and Situation | |

|---|---|

| D | First meeting or Friend |

| P | Younger or Same generation or Older |

| Rx | Chat or Request |

| Speaker | Utterances |

|---|---|

| S1 | Hazimemasite. Yorosiku onegai itasi masu. (Nice to meet you. Thank you for joining us.) |

| U1 | Yorosiku onegai si masu. (Nice to meet you, too.) |

| S2 | Kaiwa no te-ma ga ryokou tte koto na n desu kedo, sassoku desu kedo nanika imamade ixtu ta tokoro de yokaxtu ta ba syotte ari masu ka? (We’re going to talk about travel today. So, have you been to any great places you’d like to recommend?) |

| U2 | Yakusima ha yokaxtu ta desu yo. (Yakushima was a great place to visit.) |

| S3 | He-! Watasi ha ixtu ta koto nai n desu yo ne. Doko ga osusume desu ka? (Oh, really? I’ve never been there. What would you recommend?) |

| U3 | Yaku sugi rando ga osusume desu. (I would recommend Yakusugi Land.) |

| S4 | Naruhodo! Watasi mo sugoi i ki taku naxtu te ki ta n da kedo, sore tte dou ixtu ta n desu ka? (I see! I really want to go there too. How did you get there?) |

| U4 | Rentaka- wo tukai masi ta. (I rented a car.) |

| S5 | A- nara watasi mo ike sou da kara, kondo taimingu wo mi te ixtu te miru ne! Sorenisitemo ii tokoro da ne, kekkou ryokou tte suru no? (Ah, I see. I might be able to go, too. Do you travel a lot?) |

| U5 | Hima sae are ba, ryokou ni dekake teru yo. (Whenever I have free time, I go on trips.) |

| S6 | I ya- ii tokoro wo sixtu teru nante sugoi ne! Sonna anata ni kiki tai koto ga aru n desu kedo, kore kara saki kou iu tokoro ni ixtu te mi tai na tte omoxtu teru tokoro ha ari masu ka! Aimai demo ii n da kedo. (Wow, you know some great places. I have a question for you. Do you have any places you want to go in the future, even if it’s vague?) |

| U6 | Mon san misheru toka ixtu te mi tai na. (I’d like to visit Mont Saint-Michel.) |

| S7 | Humu, itugoro iko u to katte aru? (Hmm, do you have a specific time in mind?) |

| U7 | San nen i nai kana. (Within the next three years, I think.) |

| S8 | Unun. Doko ni ryokou ni iku to si te mo yappari kesi ki wo mi ni iku ryokou ni naru no kana? (I see. When it comes to traveling, it’s all about seeing the scenery, isn’t it?) |

| U8 | Umi ga kirei da to omou. (I think the sea is beautiful.) |

| S9 | Demo ryokou to ie ba oisii gohan mo sute gatai yo ne, nani ka osusume no gohan tte aru no? (But when it comes to traveling, it’s hard to pass up on delicious food, right? Do you have any food recommendations?) |

| U9 | Oosaka no tako ya ki kana. (Osaka-style takoyaki.) |

| S10 | Naruhodo! Ryokou tte i ku no mo tano sii kedo zyunbi si tari sira beru no mo tano sii yo ne-. (I see. It’s fun not only to travel, but also to prepare and research for the trip.) |

| U10 | Sou da ne. (That’s right.) |

| S11 | Demo yappari ryokou no hanasi wo suru no ha tano sii ne! (So talking about travel is really fun, isn’t it?) |

| U11 | Tano sii yo ne! (It’s so fun!) |

| S12 | Gomen. Hito ni kou iu hanasi ki ku koto ga amari nai node katte ni sugoku mo ri a gaxtu tyai masi ta. (I’m sorry. I don’t get to talk to people about this kind of stuff very often, so I got really excited.) |

| U12 | Sonna koto nai yo. (Don’t worry.) |

| S13 | Ano- mosi yokaxtu tara kondo ryokou si ta toki ni syasin toka oku xtu te kure mase n ka? Mata hana si tai desu si. (Um, if it’s okay with you, could you send me some pictures when you travel next time? I’d love to talk again.) |

| U13 | Okke-. (Sure.) |

| S14 | Maa ki ga mu i tara o nega i si masu! (Well, if you feel like it, please do!) |

| U14 | Ha-i. (Okay.) |

| S15 | Axtu, sorosoro o wari no zikan mitai desu. Kyou ha arigatou gozai masi ta! (Oh, it looks like our time is almost up. Thank you for joining us today!) |

| U15 | Un, arigatou. (Yes, thank you.) |

| S16 | Otukare sama desi ta-. (Thank you and good job!) |

| Speaker | Utterances |

|---|---|

| U6 | Tōkyō ni itte mitai desu ga, Tōkyō tte kankōchi to iu kanji ga amari shimasen yo ne? (I would like to visit Tokyo, but it doesn’t really give off the vibe of a tourist destination, does it?) |

| S7 | Fumu… itsu goro ikou toka tte arimasu ka? (Hmm… do you have any plans on when you might go?) |

| (Omission) | |

| U8 | Keshiki o miru no mo ii desu ga, watashi wa gotōchi gurume mo tanoshimi ni shiteimasu. (While enjoying the scenery is nice, I’m also looking forward to trying local cuisine.) |

| S9 | Demo ryokō to ieba oishii gohan mo sute-gatai desu yo ne… Nanika osusume no gohan tte arun desu ka? (But when it comes to traveling, delicious food is irresistible, right? Do you have any recommended dishes?) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagai, N.; Miyamoto, T.; Katagami, D. Effects of Speech Level Shift Tested by a Non-Task-Oriented Dialog System on Text Chat Dialog with Users in Japanese: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073897

Nagai N, Miyamoto T, Katagami D. Effects of Speech Level Shift Tested by a Non-Task-Oriented Dialog System on Text Chat Dialog with Users in Japanese: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(7):3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073897

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagai, Nozomu, Tomoki Miyamoto, and Daisuke Katagami. 2025. "Effects of Speech Level Shift Tested by a Non-Task-Oriented Dialog System on Text Chat Dialog with Users in Japanese: A Pilot Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 7: 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073897

APA StyleNagai, N., Miyamoto, T., & Katagami, D. (2025). Effects of Speech Level Shift Tested by a Non-Task-Oriented Dialog System on Text Chat Dialog with Users in Japanese: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences, 15(7), 3897. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073897