A Comprehensive Review of Analytical Approaches for Carotenoids Assessment in Plant-Based Foods: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Chromatographic Techniques for Carotenoids Analysis

2.1. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

2.2. Gas Chromatography (GC)

2.3. Thin-Layer Chromatography

2.4. Supercritical Fluid Chromatography

3. Sample Preparation for Carotenoids Determination

3.1. Sample Extraction Techniques

3.1.1. Solvent Extraction

3.1.2. Biobased Solvent Extraction

3.1.3. Green Extraction Technologies

- UAE utilizes sound waves above 20 kHz to generate acoustic cavitation, which disrupts plant cell walls, enhancing solvent penetration and accelerating extraction. Studies have shown significant efficiency gains using UAE. Bhimjiyani et al. (2021) reported a 50% increase in carotenoid yield from sea buckthorn, while Stupar et al. (2021) observed that UAE extracted 151.41 µg/mL of β-carotene, compared to 96.74 µg/mL with NADEs [73,74]. Similarly, Sharma et al. (2021) demonstrated that UAE combined with corn oil extracted 38.03 µg/g of carotenoids from pumpkin, nearly twice the amount obtained using hexane–isopropyl alcohol (19.21 µg/g) [71]. Extraction efficiency in the UAE depends on several parameters. Increasing ultrasound intensity produces a proportional rise in carotenoid yield [75]. Other influencing factors include extraction time, solvent-to-solid ratio, and temperature, with extraction time having the most significant effect, while temperature has minimal impact [76].

- SFE utilizes fluids in a supercritical state, characterized by solvent power as liquids and mass transfer properties as gas which accelerates extraction. Carbon dioxide is the most commonly used solvent due to its low critical temperature (31.1 °C) and pressure (7.38 MPa), making it suitable for heat-sensitive carotenoids [77]. SFE has demonstrated high extraction efficiencies. Lima et al. (2019) optimized SFE for carotenoids in 15 vegetable and fruit waste matrices, achieving up to 96.2% recovery, while Sanzo et al. (2018) reported a 98.6% recovery of astaxanthin from H. pluvialis [78,79]. Despite its advantages, slow extraction kinetics limit SFE’s efficiency. To address this, EAE and UAE can be combined with SFE to improve cell wall disruption and enhance carotenoid release [80].

- MAE applies microwave radiation to heat solvents through dipole rotation and ionic conduction, increasing cell permeability and accelerating extraction. It requires less solvent and shorter processing times but is unsuitable for thermolabile carotenoids. Comparisons between MAE and UAE show that while UAE achieved a higher yield (267 mg/100 g DW) at 200 W for 80 min, MAE still provided a notable improvement over conventional methods, yielding 262 mg/100 g DW at 120 W for 25 min. Additionally, UAE extracts exhibited higher antioxidant capacity and preserved more bioactive compounds, though they required significantly more energy consumption (229 kcal vs. 43 kcal for MAE). These findings highlight UAE’s effectiveness for carotenoid recovery while underscoring the need for energy optimization in industrial applications. [81].

- EAE utilizes cell-wall-degrading enzymes (e.g., cellulases, pectinases, proteases) to enhance carotenoid release [82,83]. Strati et al. (2015) observed a 10-fold increase in lycopene and a 6-fold increase in total carotenoids from tomato paste following enzyme pretreatment [82]. Similarly, Lavecchia and Zuorro (2008) reported a 20-fold rise in lycopene extraction from tomato waste using cellulase and pectinase [84]. EAE is particularly beneficial for wet samples, eliminating the need for drying before extraction [82,83].

- PEF extraction involves short-duration electric pulses (nanoseconds to milliseconds) to increase cell membrane permeability, facilitating carotenoid extraction. Moderate electric fields (up to 10 kV/cm) with low energy input have enhanced carotenoid recovery without degradation or isomerization [85].

- HHPE applies pressures between 100 MPa and 1000 MPa at moderate temperatures (<60 °C) to disrupt cell membranes, improving carotenoid release. Strati et al. (2015) found that 700 MPa treatment increased carotenoid yield by up to 64% [82].

- SWE exploits water’s unique properties under high temperatures (100–320 °C) and pressures (20–150 bar), allowing it to behave similarly to organic solvents. Studies have shown that SWE can achieve comparable efficiency to solvent extraction [80].

- OH extraction applies alternating electrical currents, generating uniform heating and inducing electroporation, which improves carotenoid release while minimizing oxidation and degradation [86].

3.2. Saponification and Chemical Modifications

4. Carotenoids Analysis in Plant-Based Foods

4.1. Vegetable Oils and Fats

4.2. Nuts, Seeds, and Legumes

4.3. Cereal Grains and Related Products

4.4. Emerging Plant-Based Protein Sources

5. Challenges and Limitations in Carotenoids Analysis

5.1. Challenges in Sample Preparation

- Exhaustive extraction requirements: Carotenoids are strongly bounded to plant cell matrices and lipophilic compounds, requiring high solvent volumes and prolonged processing times in techniques such as maceration, Soxhlet extraction, and solvent-assisted extraction. This increases the risk of degradation and variability in extraction efficiency [53,54,55,56,57,58,115]. To improve extraction selectivity and reduce solvent usage, techniques such as SWE and SFE have gained attention, as they offer cleaner, eco-friendly alternatives with reduced processing times [77,78,79,80,85].

- Extensive use of organic solvents and chemicals: Traditional extraction relies on solvents like hexane and acetone, posing environmental and safety concerns [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. While DES and ionic liquids (ILs) provide promising green alternatives, their validation for food applications remains incomplete. Further research is needed to standardize low-toxicity, biodegradable solvents for regulatory approval [42,59].

- Stability and degradation issues: Carotenoids are susceptible isomerization, and thermal degradation, affecting quantification accuracy [116]. Enzymatic-assisted extraction (EAE) and pulsed electric field (PEF) technologies have demonstrated the potential to reduce degradation by operating under mild conditions [81,110]. Additionally, nitrogen flushing and low-temperature extractions help preserve carotenoid integrity during sample preparation [117,118].

- Lack of universally applicable extraction methods: Due to matrix-dependent variations in carotenoid interactions with proteins, fibers, and lipids, extraction conditions must be tailored. [119]. A single standardized method applicable to all matrices is currently lacking, making interlaboratory comparisons and method validation even more complex. A promising solution lies in emerging hybrid approaches, such as combining UAE with enzymatic treatments, which have improved recovery in complex food matrices [75,86]. Further optimization of multi-step protocols is necessary for interlaboratory standardization.

5.2. Challenges in Detection Systems

- Low resolution of TLC: While TLC remains a cost-effective screening method, its low resolution restricts its ability to separate and quantify individual carotenoids, especially those with similar structures [23,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. This limitation makes TLC unsuitable for complex food matrices where multiple carotenoids coexist. To enhance separation efficiency, high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) with densitometric detection has been proposed, allowing for semi-quantitative analysis of carotenoids [23,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

- High cost and environmental concerns of HPLC, UHPLC, and SFC: While HPLC and UHPLC remain the gold standards for carotenoid analysis, their high solvent consumption and operational costs limit accessibility particularly in low-resource settings [123]. Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) has been introduced as a solvent-reducing alternative, particularly for nonpolar carotenoids. However, wider adoption requires greater standardization of SFC methodologies to improve reproducibility and regulatory acceptance [124].

- Detection sensitivity and matrix interferences: DAD and UV-Vis spectroscopy are commonly used for carotenoid detection, but they face interference challenges in complex food matrices [125]. The integration of tandem MS (HPLC-MS/MS, UPLC-MS/MS) has significantly improved specificity and sensitivity, particularly for trace carotenoids in low-concentration samples [125,126]. These techniques are now widely used for food authentication and quality control.

5.3. Challenges in Regulatory and Standardization

- Lack of official standardized methods for all carotenoids: While regulatory agencies such as AOAC International and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) provide validated methods for β-carotene analysis, official methods covering a broader spectrum of carotenoids are still lacking [127]. This gap affects the accuracy and reproducibility of carotenoid quantification across different laboratories. Standardization efforts should focus on harmonizing protocols for food safety testing and nutritional labeling.

- Limited availability of analytical standards: Certified reference materials and analytical standards are not available for all carotenoids, especially for minor and newly identified carotenoids, limiting the ability to perform accurate quantification [128]. This challenge is particularly relevant for minor carotenoids and newly discovered derivatives, where standard synthesis and commercial availability remain constrained. Expanding the availability of commercially synthesized carotenoids could support regulatory compliance and method validation.

- High determination limits (low sensitivity) and incomplete validation: Many existing methods exhibit high limits of detection (LODs) and limits of quantification (LOQs), restricting their applicability to trace-level carotenoid analysis in specific food matrices [129]. The adoption of high-resolution MS and isotope dilution methods has enhanced precision, particularly in regulatory food testing laboratories. Furthermore, incomplete analytical validation of carotenoid determination methods, including interlaboratory reproducibility studies, hinders regulatory approval and method harmonization.

- Alignment with food safety regulations: Chromatographic techniques must align with food industry regulations, particularly in regions with strict labeling requirements. For example, HPLC and MS-based methods are widely accepted in FDA and EFSA regulations for carotenoid content verification in fortified foods [130,131]. Further regulatory updates may be needed to accommodate emerging techniques, such as SFC and novel solvent-free extractions.

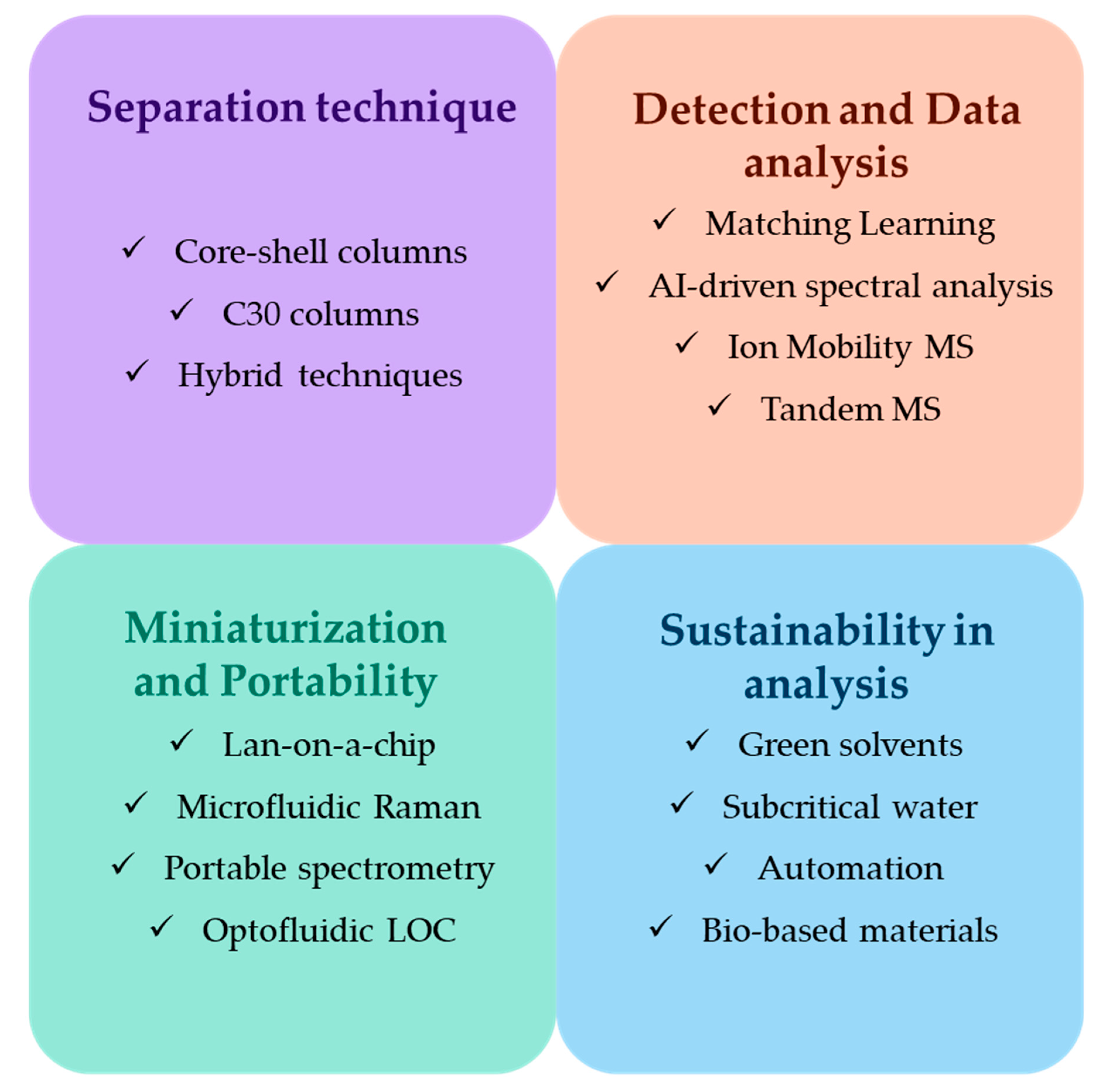

6. Advances in Analytical Strategies and Future Directions

6.1. Innovations in Separation Techniques for Carotenoids Analysis

6.2. Future Trends in Carotenoids Analysis

6.3. Sustainability in Carotenoid Analysis

7. Methodology for Bibliographic Search

8. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| UHPLC | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| HPTLC | High-performance thin-layer chromatography |

| SFC | Supercritical fluid chromatography |

| UPLC | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

| DAD | Diode array detector |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy |

| PAD | Photodiode array detector |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| MS/MS | Tandem mass spectrometry |

| APCI | Atmospheric pressure chemical ionization |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| QTOF-MS | Quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| IMS | Ion mobility spectrometry |

| SE | Solvent extraction |

| UAE | Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

| MAE | Microwave-assisted extraction |

| SFE | Supercritical fluid extraction |

| EAE | Enzyme-assisted extraction |

| PEF | Pulsed electric field extraction |

| HHPE | High-hydrostatic-pressure extraction |

| SWE | Subcritical water extraction |

| OHE | Ohmic heating extraction |

| SPE | Solid-phase extraction |

| LLE | Liquid–liquid extraction |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| MTBE | Methyl tert-butyl ether |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| EtOAc | Ethyl acetate |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| IPA | Isopropanol |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| ILs | Ionic liquids |

| DES | Deep eutectic solvents |

| NADES | Natural deep eutectic solvents |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| GAC | Green analytical chemistry |

| WOS | Web of Science |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

References

- Eroglu, A.; Al’Abri, I.S.; Kopec, R.E.; Crook, N.; Bohn, T. Carotenoids and their health benefits as derived via their interactions with gut microbiota. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swapnil, P.; Meena, M.; Singh, S.K.; Dhuldhaj, U.P.; Marwal, A. Vital roles of carotenoids in plants and humans to deteriorate stress with its structure, biosynthesis, metabolic engineering, and functional aspects. Curr. Plant Biol. 2021, 26, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as natural functional pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D. Status of carotenoid analytical methods and in vitro assays for the assessment of food quality and health effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 1, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Bonet, M.L.; Borel, P.; Keijer, J.; Landrier, J.-F.; Milisav, I.; Ribot, J.; Riso, P.; Winklhofer-Roob, B.; Sharoni, Y.; et al. Mechanistic aspects of carotenoid health benefits—Where are we now? Nutr. Res. Rev. 2021, 34, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, M.D.; Pitts, S.J.; Jahns, L.; Firnhaber, G.C.; Loofbourrow, B.M.; Zeng, A.; Scherr, R.E. Criterion-related validity of spectroscopy-based skin carotenoid measurements as a proxy for fruit and vegetable intake: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.M.; Mein, J.R.; Chaudhuri, S.K.; Constant, H.L. An improved UHPLC-UV method for separation and quantification of carotenoids in vegetable crops. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Patil, B.S. Improved sample preparation and optimized solvent extraction for quantitation of carotenoids. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2021, 76, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesellier, E.; West, C. Supercritical fluid chromatography for the analysis of natural dyes: From carotenoids to flavonoids. J. Sep. Sci. 2022, 45, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricarte, G.N.; Coelho, M.A.Z.; Marrucho, I.M.; Ribeiro, B.D. Enzyme-assisted extraction of carotenoids and phenolic compounds from sunflower wastes using green solvents. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzakovich, M.P.; Gas-Pascual, E.; Orchard, C.J.; Sari, E.N.; Riedl, K.M.; Schwartz, S.J.; Francis, D.M.; Cooperstone, J.L. Analysis of tomato carotenoids: Comparing extraction and chromatographic methods. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Lin, J.; Peng, S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Rao, L.; Zhao, L. Development of an HPLC-PDA method for the determination of capsanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, β-cryptoxanthin, and β-carotene simultaneously in chili peppers and products. Molecules 2023, 28, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebregziabher, B.S.; Zhang, S.; Qi, J.; Azam, M.; Ghosh, S.; Feng, Y.; Huai, Y.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Sun, J. Simultaneous determination of carotenoids and chlorophylls by the HPLC-UV-VIS method in soybean seeds. Agronomy 2021, 11, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; Sánchez-Prieto, M.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Assessment of carotenoid concentrations in red peppers (Capsicum annuum) under domestic refrigeration for three weeks as determined by HPLC-DAD. Food Chem. X 2020, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, M.V.; Piccoli, P.; Fontana, A. Simultaneous determination of carotenoids with different polarities in tomato products using a C30 core-shell column-based approach. Microchem. J. 2020, 159, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Carreira-Casais, A.; Silva, A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. A HPLC-DAD method for identifying and estimating the content of fucoxanthin, β-carotene and chlorophyll a in brown algal extracts. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, J.P.; Nohr, D.; Biesalski, H.K. Rapid and easy carotenoid quantification in Ghanaian starchy staples using RP-HPLC-PDA. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 67, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Giraldo, L.M.; Bueno, M.; Corpas-Iguarán, E.; Taborda-Ocampo, G.; Cifuentes, A. HPLC-DAD-APCI-MS as a tool for carotenoid assessment of wild and cultivated cherry tomatoes. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpino-Rius, A.; Eras, J.; Marsol-Vall, A.; Vilaró, F.; Balcells, M.; Canela-Garayoa, R. Ultra performance liquid chromatography analysis to study the changes in the carotenoid profile of commercial monovarietal fruit juices. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1331, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujić, V.J.; Todorović, B.; Kranvogl, R.; Ciringer, T.; Ambrožič-Dolinšek, J. Diversity and content of carotenoids and other pigments in the transition from the green to the red stage of Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae identified by HPLC-DAD and LC-QTOF-MS. Plants 2022, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multari, S.; Carlin, S.; Sicari, V.; Martens, S. Differences in the composition of phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and volatiles between juice and pomace of four citrus fruits from Southern Italy. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yu, Q.; Li, B.; Kan, J. Comparative analysis of carotenoids and metabolite characteristics in discolored red pepper and normal red pepper based on non-targeted metabolomics. LWT 2022, 153, 112398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, P.; Viñas, M.; Steingass, C.B.; Gruschwitz, M.; Guevara, E.; Carle, R.; Jiménez, V.M. Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) by-products as a source of carotenoids and phenolic compounds—Evaluation of varieties with different peel color. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 590597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintea, A.; Dulf, F.V.; Bunea, A.; Socaci, S.A.; Pop, E.A.; Oprița, V.A.; Mondello, L. Carotenoids, fatty acids, and volatile compounds in apricot cultivars from Romania—A chemometric approach. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.M.; Weesepoel, Y.; Socaciu, C.; Pintea, A.; Vincken, J.P.; Gruppen, H. Carotenoid composition of berries and leaves from six Romanian sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) varieties. Food Chem. 2014, 147, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.H.; Kaykhaii, M.; Mirmoghaddam, M.; Boczkaj, G. Preconcentration and analytical methods for determination of methyl tert-butyl ether and other fuel oxygenates and their degradation products in the environment: A review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 582–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Thuy, N.T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Sugiyama, H.; Noda, M.; Hirao, M. Techno-economic and environmental assessment of bioethanol-based chemical process: A case study on ethyl acetate. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2011, 30, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Varala, R.; Seema, V. A Decennial Update on the Applications of Trifluroacetic Acid. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2024, 21, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP). Scientific Opinion on the safety and efficacy aliphatic and aromatic amines (chemical group 33) when used as flavourings for all animal species. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Cao, K.; Wang, X.; Fang, W.; Zhu, G.; Wang, L. Integrated ESI-MS/MS and APCI-MS/MS based metabolomics reveal the effects of canning and storage on peach fruits. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fang, K.; Chen, S.; Xu, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, H. Profiling fragments for carotenoid esters in Penaeus monodon by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 35, e8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Tkacz, K.; Turkiewicz, I.P. Fruit tree leaves as unconventional and valuable source of chlorophyll and carotenoid compounds determined by liquid chromatography-photodiode-quadrupole/time of flight-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-PDA-qToF-ESI-MS). Food Chem. 2021, 349, 129156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stutz, H.; Bresgen, N.; Eckl, P.M. Analytical tools for the analysis of β-carotene and its degradation products. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 650–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Gou, M.; Wu, X.; Bi, J. Influence of different pre-treatments on flavor quality of freeze-dried carrots mediated by carotenoids and metabolites during 120-day storage. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 113050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, T.D.; Dixon, L.R.; Schmidt, F.C.; Blakeslee, J.J.; Bennett, A.E.; Schultz, Z.D. Identification and quantification of pigments in plant leaves using thin-layer chromatography-Raman spectroscopy (TLC-Raman). Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 2449–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynstova, V.; Sterbova, D.; Klejdus, B.; Hedbavny, J.; Huska, D.; Adam, V. Separation, identification and quantification of carotenoids and chlorophylls in dietary supplements containing Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina platensis using high-performance thin-layer chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 148, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardowska, N.P. Enhanced pigment content estimation using the Gauss-peak spectra method with thin-layer chromatography for a novel source of natural colorants. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migas, P.; Stempka, N.; Krauze-Baranowska, M. The use of thin-layer chromatography in the assessment of the quality of lutein-containing dietary supplements. JPC-J. Planar Chromatogr. 2020, 33, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starek, M.; Guja, A.; Dąbrowska, M.; Krzek, J. Assay of β-carotene in dietary supplements and fruit juices by TLC-densitometry. Food Anal. Methods 2015, 8, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Gupta, P.; De, B. Thin-layer chromatographic characterization of carotenoid isolates in sugar date palm (Phoenix sylvestris) fruit epicarp and inflorescence axis. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2017, 9, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwack, W.; Pellissier, E.; Morlock, G. Analysis of unauthorized Sudan dyes in food by high-performance thin-layer chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 5641–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheokand, P.; Tiwari, S.K. Characterization of carotenoids extracted from Haloferax larsenii NCIM 5678 isolated from Pachpadra salt lake, Rajasthan. Extremophiles 2024, 28, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spangenberg, B.; Seigel, A.; Brämer, R. Screening of orange peel waste on valuable compounds by gradient multiple-development diode-array high-performance thin-layer chromatography. JPC-J. Planar Chromatogr. 2022, 35, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyachandran, S.; Kiyun, P.; Ihn-Sil, K.; Baskaralingam, V. Identification and characterization of bioactive pigment carotenoids from shrimps and their biofilm inhibition. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiszewski, M.; Namieśnik, J.; Pena-Pereira, F. Environmental risk-based ranking of solvents using the combination of a multimedia model and multi-criteria decision analysis. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Moon, S.H.; Gansukh, E.; Keum, Y.S. An efficient one-step scheme for the purification of major xanthophyll carotenoids from lettuce, and assessment of their comparative anticancer potential. Food Chem. 2018, 266, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Qiu, J.; Kong, F. Simultaneous determination of pigments in tea by ultra-performance convergence chromatography (UPC2). Anal. Lett. 2020, 53, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumaah, F.; Plaza, M.; Abrahamsson, V.; Turner, C.; Sandahl, M. A fast and sensitive method for the separation of carotenoids using ultra-high-performance supercritical fluid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 5883–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nováková, L.; Sejkorová, M.; Smolková, K.; Plachká, K.; Švec, F. The benefits of ultra-high-performance supercritical fluid chromatography in determination of lipophilic vitamins in dietary supplements. Chromatographia 2019, 82, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, D.; Zoccali, M.; Giofre, S.V.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L. Apocarotenoids determination in Capsicum chinense Jacq. cv. Habanero, by supercritical fluid chromatography-triple-quadrupole/mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2017, 231, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Du, L.; Tang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Li, F.; Yao, X.; Meng, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, J. Development and application of a SFC–DAD–MS/MS method to determine carotenoids and vitamin A in egg yolks from laying hens supplemented with β-carotene. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, P.; Giuffrida, D.; Oteri, M.; Inferrera, V.; Dugo, P.; Mondello, L. Supercritical fluid chromatography × ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography for red chili pepper fingerprinting by photodiode array, quadrupole-time-of-flight and ion mobility mass spectrometry (SFC × RP-UHPLC-PDA-Q-ToF MS-IMS). Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 3331–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, D.; Zoccali, M.; Mondello, L. Recent developments in the carotenoid and carotenoid derivatives chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis in food matrices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 132, 116047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uquiche, E.; Antilaf, I.; Millao, S. Enhancement of pigment extraction from B. braunii pretreated using CO₂ rapid depressurization. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.-Y.; Vijayan, D.; Praveenkumar, R.; Han, J.-I.; Lee, K.; Park, J.-Y.; Chang, W.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Oh, Y.-K. Cell-wall disruption and lipid/astaxanthin extraction from microalgae: Chlorella and Haematococcus. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, M. Methods of analysis (extraction, separation, identification, and quantification) of carotenoids from natural products. J. Ecosyst. Ecogr. 2016, 6, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimboor, R.; Natarajan, R.B.; Menon, K.R.; Chandrasekhar, L.P.; Moorkoth, V. Red pepper (Capsicum annuum) carotenoids as a source of natural food colors: Analysis and stability—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1258–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.; Socaciu, C.; Pintea, A. Xanthophyll esters in fruits and vegetables. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2014, 42, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Flora, G.; Sevanan, M.; Sripriya, R.; Chen, W.H.; Park, J.-H.; Banu, J.R.; Kumar, G. Technological advances in the production of carotenoids and their applications: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Flores, F.G.; Monteagudo-Arrebola, M.J.; Dobado, J.A.; Isac-García, J. Green and bio-based solvents. Top. Curr. Chem. (Z) 2018, 376, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Ravi, H.K.; Khadhraoui, B.; Hilali, S.; Perino, S.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S. Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of food and natural products: Panorama, principles, applications, and prospects. Molecules 2019, 24, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morón-Ortiz, Á.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Sustainable green extraction of carotenoid pigments: Innovative technologies and bio-based solvents. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morón-Ortiz, Á.; Mapelli-Brahm, P.; León-Vaz, A.; Benitez-González, A.M.; Martín-Gómez, A.N.; León, R.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J. Assessment of milling and the green biosolvents ethyl lactate and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-methyloxolane) for the ultrasound-assisted extraction of carotenoids in common and phytoene-rich Dunaliella bardawil microalgae. LWT 2024, 213, 117007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkowska, K.; Simińska, D.; Kunicka-Styczyńska, A. Bioactivities and microbial quality of Lycium fruits (goji) extracts derived by various solvents and green extraction methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, C.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Claux, O.; Rapinel, V.; Tomao, V.; Stathopoulos, P.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Tabasso, S.; Jacques, L.; Chemat, F. Higher yield and polyphenol content in olive pomace extracts using 2-methyloxolane as bio-based solvent. Foods 2022, 11, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murador, D.C.; Braga, A.R.C.; Martins, P.L.G.; Mercadante, A.Z.; de Rosso, V.V. Ionic liquid associated with ultrasonic-assisted extraction: A new approach to obtain carotenoids from orange peel. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, K.S.; Chong, Y.M.; Chang, W.S.; Yap, J.M.; Foo, S.C.; Khoiroh, I.; Lau, P.L.; Chew, K.W.; Ooi, C.W.; Show, P.L. Permeabilization of Chlorella sorokiniana and extraction of lutein by distillable CO₂-based alkyl carbamate ionic liquids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Lima, F.; Ribeiro, B.D.; Marrucho, I.M. Deep eutectic solvents: Overcoming 21st century challenges. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 18, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, C.; Casadei, E.; Valli, E.; Tura, M.; Ragni, L.; Bendini, A.; Toschi, T.G. Sustainable drying and green deep eutectic extraction of carotenoids from tomato pomace. Foods 2022, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñas-Ospino, A.; López-Malo, D.; Esteve, M.J. Improving carotenoid extraction, stability, and antioxidant activity from Citrus sinensis peels using green solvents. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2349–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Bhat, R. Extraction of carotenoids from pumpkin peel and pulp: Comparison between innovative green extraction technologies (ultrasonic and microwave-assisted extractions using corn oil). Foods 2021, 10, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elik, A.; Yanık, D.K.; Göğüş, F. Microwave-assisted extraction of carotenoids from carrot juice processing waste using flaxseed oil as a solvent. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 123, 109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimjiyani, V.H.; Borugadda, V.B.; Naik, S.; Dalai, A.K. Enrichment of flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum) oil with carotenoids of sea buckthorn pomace via ultrasound-assisted extraction technique. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar, A.; Šeregelj, V.; Ribeiro, B.D.; Pezo, L.; Cvetanović, A.; Mišan, A.; Marrucho, I. Recovery of β-carotene from pumpkin using switchable natural deep eutectic solvents. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukroufa, M.; Boutekedjiret, C.; Chemat, F. Development of a green procedure of citrus fruits waste processing to recover carotenoids. Resour.-Efficient Technol. 2017, 3, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic Gajic, I.M.; Savic, I.M.; Gajic, D.G.; Dosic, A. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of carotenoids from orange peel using olive oil and its encapsulation in Ca-alginate beads. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Nutrizio, M.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. Green extraction of natural products: Concept and principles. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 2325–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.D.; Kestekoglou, I.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Supercritical fluid extraction of carotenoids from vegetable waste matrices. Molecules 2019, 24, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzo, G.D.; Mehariya, S.; Martino, M.; Larocca, V.; Casella, P.; Chianese, S.; Musmarra, D.; Balducchi, R.; Molino, A. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of astaxanthin, lutein, and fatty acids from Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, M.; Pandey, P.; Martin, G.J.O.; Mishra, H.N.; Ashokkumar, M. Innovative technologies for extraction and microencapsulation of bioactives from plant-based food waste and their applications in functional food development. Foods 2021, 10, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutia, H.; Mahanta, C.L. Green ultrasound and microwave extraction of carotenoids from passion fruit peel using vegetable oils as a solvent: Optimization, comparison, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, I.F.; Gogou, E.; Oreopoulou, V. Enzyme and high-pressure assisted extraction of carotenoids from tomato waste. Food Bioprod. Process. 2015, 94, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuyen, H.V.; Nguyen, M.H.; Roach, P.D.; Golding, J.B.; Parks, S.E. Microwave-assisted extraction and ultrasound-assisted extraction for recovering carotenoids from Gac peel and their effects on antioxidant capacity of the extracts. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavecchia, R.; Zuorro, A. Improved lycopene extraction from tomato peels using cell-wall degrading enzymes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 228, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.N.; Jaeschke, D.P.; Rech, R.; Mercali, G.D.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Pueyo, J.R. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of carotenoids from Chlorella zofingiensis. Algal Res. 2024, 79, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loypimai, P.; Nakthong, A.; Sitthisuanjik, K. Enrichment of soybean oil with β-carotene and lycopene from Gac (Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng) powder using ohmic heating and ultrasound extraction. Food Meas. 2024, 18, 8865–8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yan, J.; Dong, H.; Gao, K.; Yu, K.; He, C.; Mao, X. Astaxanthin with different configurations: Sources, activity, post-modification, and application in foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 49, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.d.M.R.; Bobrowski Rodrigues, D.; Brison, R.; Nepomuceno, F.; Bento, M.L.; Oliveira, L.d.L.d. A scoping review on carotenoid profiling in Passiflora spp.: A vast avenue for expanding the knowledge on the species. Molecules 2024, 29, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. A Guide to Carotenoid Analysis in Foods. In A Guide to Carotenoid Analysis in Foods, 2nd ed.; ILSI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 1, pp. 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.T.; Agarwal, R.; Takagi, T.; Netzel, M.E.; Harper, S.M.; O’Hare, T.J. A Modified Extraction and Saponification Method for the Determination of Carotenoids in the Fruit of Capsicum annuum. Agriculture 2025, 15, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebregziabher, B.S.; Gebremeskel, H.; Debesa, B.; Ayalneh, D.; Mitiku, T.; Wendwessen, T.; Getachew, T. Carotenoids: Dietary sources, health functions, biofortification, marketing trend and affecting factors—A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, A.; Dal Bosco, C.; Fanali, S.; Fanali, C. Large-scale profiling of carotenoids by using non-aqueous reversed-phase liquid chromatography–photodiode array detection–triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometry: Application to some varieties of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 164, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes Silva, J.V.; Silva Santos, A.; Araujo Pereira, G.; Campos Chisté, R. Ultrasound-assisted extraction using ethanol efficiently extracted carotenoids from peels of peach palm fruits (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) without altering qualitative carotenoid profile. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topan, C.; Nicolescu, M.; Simedru, D.; Becze, A. Complex evaluation of storage impact on maize (Zea mays L.) quality using chromatographic methods. Separations 2023, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.C.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.L.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Bisinella, R.Z.; de Oliveira, C.S.; Schnitzler, E.; Bet, C.D.; Maciel, G.M.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Biological activities, chromatographic profile and thermal stability of organic and conventional goji berry. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, V.; Marini, F.; Boccacci Mariani, M.; Livi, G. Accelerated solvent extraction for liquid chromatographic determination of carotenoids in durum wheat pasta: A chemometric approach using statistical experimental design. Microchem. J. 2023, 190, 108650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Liao, X.; Xu, Z. Development and validation of an analytical method for the quantification of capsanthin in chili peppers and products by high-performance liquid chromatography. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2343–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Herrera, C.; Chacón, A.; Artavia, G.; Granados-Chinchilla, F. Simultaneous LC/MS analysis of carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins in Costa Rican avocados (Persea americana Mill.). Molecules 2019, 24, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Shehzad, Q.; Yu, L.; Tian, A.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Zheng, L.; Xu, L. Comparative study on quality characteristics of Bischofia polycarpa seed oil by different solvents: Lipid composition, phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Clemente, G.; García-González, M.A.; González-González, M. Soil lipid analysis by chromatography: A critical review of the current state in sample preparation. J. Chromatogr. Open 2024, 6, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, L.C.; Rimmer, C.A.; Wilson, W.B. Characterization of triacontyl (C-30) liquid chromatographic columns. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1614, 460732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, D.; Rocchetti, G.; Cossignani, L.; Senizza, B.; Pollini, L.; Lucini, L.; Blasi, F. Untargeted metabolomics to evaluate the stability of extra-virgin olive oil with added Lycium barbarum carotenoids during storage. Foods 2019, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, C.; La Motta, C.; Valoppi, F. Improving the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of carotenoids by means of nanostructured delivery systems: A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E.; Beltrán-de-Miguel, B.; Samaniego-Aguilar, K.X.; Sánchez-Prieto, M.; Estévez-Santiago, R.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B. Extraction and analysis by HPLC-DAD of carotenoids in human feces from Spanish adults. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, D.-N.G.; Rashed, A.A.; Noh, M.F.M. Determination of retinol and carotenoids in selected Malaysian food products using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, P.; Faienza, M.F.; Naeem, M.Y.; Corbo, F.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Muraglia, M. Overview of the potential beneficial effects of carotenoids on consumer health and well-being. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Mandić, A.I.; Bantis, F.; Böhm, V.; Borge, G.I.A.; Brnčić, M.; Bysted, A.; Cano, M.P.; Dias, M.G.; Elgersma, A.; et al. A comprehensive review on carotenoids in foods and feeds: Status quo, applications, patents, and research needs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodedji, K.A.F.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Lee, B.; Kim, H.Y. An integrated approach for biofortification of carotenoids in cowpea for human nutrition and health. Plants 2024, 13, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosibo, O.K.; Ferrentino, G.; Udenigwe, C.C. Microalgae proteins as sustainable ingredients in novel foods: Recent developments and challenges. Foods 2024, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, A.; Park, J.; Baritugo, K.A.; Kim, B.; Sil Moon, S.; Rahman, A.; Park, S. A holistic approach toward development of plant-based meat alternatives through incorporation of novel microalgae-based ingredients. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, C.; Capriotti, A.L.; La Barbera, G.; Montone, C.M.; Piovesana, S.; Laganà, A. Liquid chromatographic strategies for separation of bioactive compounds in food matrices. Molecules 2018, 23, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, P.S.; Morais Júnior, W.G.; Martins, A.A.; Caetano, N.S.; Mata, T.M. Microalgae biomolecules: Extraction, separation and purification methods. Processes 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haładyn, K.; Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P. Isolation of bioactive compounds (carotenoids, tocopherols, and tocotrienols) from Calendula officinalis L., and their interaction with proteins and oils in nanoemulsion formulation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iddir, M.; Porras Yaruro, J.F.; Cocco, E.; Hardy, E.M.; Appenzeller, B.M.R.; Guignard, C.; Larondelle, Y.; Bohn, T. Impact of protein-enriched plant food items on the bioaccessibility and cellular uptake of carotenoids. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.S. Carotenoid extraction methods: A review of recent developments. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Nayak, J.J.; Alagoz, Y.; Wojtalewicz, D.; Cazzonelli, C.I. Purification and use of carotenoid standards to quantify cis-trans geometrical carotenoid isomers in plant tissues. Methods Enzymol. 2022, 670, 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Tadmor, Y.; Li, L. Pathways for carotenoid biosynthesis, degradation, and storage. In Plant and Food Carotenoids; Rodríguez-Concepción, M., Welsch, R., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénicaud, C.; Achir, N.; Dhuique-Mayer, C.; Dornier, M.; Bohuon, P. Degradation of β-carotene during fruit and vegetable processing or storage: Reaction mechanisms and kinetic aspects—A review. Fruits 2011, 66, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, L.; Colle, I.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Palmero, P.; Van Loey, A.; Hendrickx, M. Carotenoid bioaccessibility in fruit-and vegetable-based food products as affected by product (micro)structural characteristics and the presence of lipids: A review. TrAC Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 38, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, E.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving carotenoid extraction from tomato waste by pulsed electric fields. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaluddin, S.A.; Thiruvenkadam, S.; Izhar, S.; Hiroyuki, Y.; Danquah, M.K.; Harun, R. Subcritical water technology for enhanced extraction of biochemical compounds from Chlorella vulgaris. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5816974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke, D.P.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Mercali, G.D. Evaluation of non-thermal effects of electricity on ascorbic acid and carotenoid degradation in acerola pulp during ohmic heating. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.W.; Zhang, K. Ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC) in method development. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 63, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzera, M.; Zwerger, M. Analysis of natural products by SFC–applications from 2015 to 2021. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 145, 116463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrecilla, J.S.; Cámara, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Piera, G.; Caceres, J.O. Solving the spectroscopy interference effects of β-carotene and lycopene by neural networks. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6261–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Z.; Cooks, R.G. Miniature mass spectrometers. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2009, 2, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). Carotenes and xanthophylls in dried plant materials and mixed feeds. AOAC Off. Methods Anal. 1990, 970, 1048–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpless, K.E.; Thomas, J.B.; Christopher, S.J.; Greenberg, R.R.; Sander, L.C.; Schantz, M.M.; Welch, M.J.; Wise, S.A. Standard reference materials for foods and dietary supplements. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 389, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotter, M.J. Methods for the determination of European Union-permitted added natural colours in foods: A review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2011, 28, 527–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). Determination of Color Additives in Foods and Cosmetics Using HPLC. FDA Laboratory Methods. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/158010/download (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Flavourings (FAF). Safety assessment of carotenoid-rich extract from Paracoccus carotinifaciens as a food additive. EFSA J. 2024, 22, 8905. [Google Scholar]

- Si, T.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Liang, X.; Guo, Y. Metal-organic framework-based core-shell composites for chromatographic stationary phases. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 149, 116545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, X.; Wei, Y.; Xu, T.; Li, D.; Luo, X.; You, W.; Ke, C. Applying deep learning algorithms for non-invasive estimation of carotenoid content in foot muscle of different colors in Pacific abalone. Preprint 2024. [CrossRef]

- Revett, K. A machine learning investigation of a beta-carotenoid dataset. In Granular Computing: At the Junction of Rough Sets and Fuzzy Sets; Bello, R., Falcón, R., Pedrycz, W., Kacprzyk, J., Eds.; Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, A.; Rohrlack, T.; Bellouard, Y. Lab on a chip technologies for algae detection: A review. J. Biophotonics 2012, 5, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítek, P.; Jehlička, J.; Edwards, H.G.; Hutchinson, I.; Ascaso, C.; Wierzchos, J. Miniaturized Raman instrumentation detects carotenoids in Mars-analogue rocks from the Mojave and Atacama deserts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014, 372, 20140196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishampayan, V.; Kapoor, A.; Gumfekar, S.P. Enhancement in the limit of detection of lab-on-chip microfluidic devices using functional nanomaterials. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 5208–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallone, J.A.L.; dos Santos Caramês, E.T.; Alamar, P.D. Green analytical chemistry applied in food analysis: Alternative techniques. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 22, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Böhm, V.; Borge, G.I.A.; Cano, M.P.; Fikselová, M.; Gruskiene, R.; O’Brien, N.M. Carotenoids: Considerations for their use in functional foods, nutraceuticals, nutricosmetics, supplements, botanicals, and novel foods in the context of sustainability, circular economy, and climate change. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, L.; Marcovich, N.E.; Gomez-Zavaglia, A. Valorization of fruit and vegetables agro-wastes for the sustainable production of carotenoid-based colorants with enhanced bioavailability. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Analytes | Stationary Phase | Mobile Phase | Flow Rate (mL/min) | Detector System | Analysis Time (min) | LOD (ng/g) | LOQ (ng/g) | Recovery (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red chili peppers (9 varieties) | Capsanthin, Zeaxanthin, Lutein, β-Cryptoxanthin, β-Carotene | Spherisorb ODS-2 C18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) | MeOH/THF/ACN/Acetone | 0.5/1.0/1.5 | DAD | 25 | 20–63 | 67–209 | 88–107 | [12] |

| Legumes (7 species, including beans, peas, and lentils) | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-Carotene, α-Carotene, β-Cryptoxanthin | C30 (250 × 4.6 mm I.D., S-5 μm) | MTBE, MeOH-20 mM ammonium acetate, and water | 0.9 | UV-Vis | 45 | 51–300 | 155–909 | 83–107 | [13] |

| Sweet red peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, α-Carotene, β-Carotene, β-Cryptoxanthin, Violaxanthin, Capsanthin, Phytoene, Phytofluene | C30 YMC column (5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm i.d.) | 0.1% TMA in MeOH and MTBE | NR | DAD | 21 | NR | NR | NR | [14] |

| Tomatoes (Cherry and Pear varieties; Solanum lycopersicum) | Lutein, β-Carotene, Lycopene | C30 column (3.0 mm × 150 mm, 2.6 μm) | MeOH/MTBE/H₂O | 0.4 | DAD | 20 | 3–46 | 8–1530 | 86–116 | [15] |

| Brown algal extracts | Fucoxanthin and β-Carotene | Nova-Pak C18 (3.9 × 150 mm, 4 µm) | AAc/MeOH/EtOAc | 0.5 | DAD | 40 | 500–560 | NR | 93–103 | [16] |

| Starchy staples (potato, cassava, sweet potato, yam, taro) | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-Cryptoxanthin, α-Carotene, β-Carotene | Prontosil 200–3-C30 (150 × 4.6 mm; 3 μm) | MeOH/H₂O (95:5) and MTBE/MeOH/H₂O (85:10:5) | 2 | DAD | 15 | 65.5 –113 | 241–410 | NR | [17] |

| Wild cherry tomatoes | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-carotene, Lycopene | YMC-C30 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | MeOH/MTBE/H₂O | 0.8 | DAD-MS | 33 | 3.66–8.11 | 17.2–244 | NR | [18] |

| Fruit juices (commercial and fresh samples from citrus, berries, and tropical fruits) | β-Carotene, (all-E)-Lutein, β-Cryptoxanthin, (all-E)-Zeaxanthin, Phytoene, (all-E)-Violaxanthin, (9′Z)-Neoxanthin, (all-E)-Antheraxanthin | BEH C18 (100 mm × 2.1 mm; 1.7 μm) | ACN–MeOH and H₂O | 0.5 | DAD | 16.6 | 22–157 | 70–52 | 75–104 | [19] |

| Microalgae | 30 identified carotenoids | Poroshell 120 EC-C18 (150 mm × 3.0 mm; 2.7 μm) | 0.1% FA in H2O-MeOH (1:1 v/v) and in MTBT-MeOH (8:2 v/v) | 0.2 | DAD-QTOF-MS | 55 | NR | NR | NR | [20] |

| Citrus fruits (mandarin, lemon, sweet orange, bergamot) | Violaxanthin, Neoxanthin, Lutein Epoxide, Antheraxanthin, Luteoxanthin, Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-Cryptoxanthin, α-Carotene, β-Carotene | C30 (250 × 2.1 mm; 3 μm) | ACN/MBTE/MeOH and water | 0.4 | DAD | NR | NR | NR | NR | [21] |

| Dried red peppers (Capsicum frutescens var.) | 23 identified carotenoids | ORBAX Eclipse XDB C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm) | H₂O and Acetone | 0.6 | DAD-APCI/MS/MS | 37 | NR | NR | NR | [22] |

| Soybean seeds | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, β-Carotene, α-Carotene, β-Cryptoxanthin | C30 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | EtOH/ACO | 0.9 | UV-Vis | 77–84 | 5.1–30 | 15.5–90.9 | 83–106 | [13] |

| Coffee berries | Violaxanthin, Neoxanthin, Chlorophyll b, Lutein, Chlorophyll a, α-Carotene, β-Carotene | C30 (150 × 3 mm; 3 μm) | MeOH/MTBE/water | 0.42 | DAD-APCI/MS | 90 | 0.5 –3.8 | 0.48 –12 | NR | [23] |

| Apricots | 27 identified carotenoids | C30 (250 × 4.6 mm; 5 μm) | MeOH/MTBE/water | 1 | DAD-APCI/MS | 140 | NR | NR | NR | [24] |

| Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) | 19 identified carotenoids | BEH C18 (150 mm × 2.1 mm; 1.7 μm) | EtOAc/ACN/water | 0.4 | DAD-ESI/MS | 27 | NR | NR | NR | [25] |

| Sample | Analyte | Stationary Phase | Developing Solvent | Determination | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato leaf extracts | β-carotene, and lutein | TLC silica gel 60 F254 plates (5 cm × 10 cm) | PE:CE:EtOAc:ACO: tOH (60:16:10:10:6 v/v) | Raman Spectroscopy (Handheld Metrohm MiraDS, 785 nm laser) | [35] |

| Dietary supplements | β-carotene, canthaxanthin, astaxanthin, lutein and zeaxanthin | HPTLC Silica Gel 60 F254 Plates 20 × 10 cm | PE:CH:EtOAc:Ac:EtOH (60:16:10:10:6, v/v/v/v/v) | UV (440 nm) using a TLC Scanner | [36] |

| Aesculus hippocastanum leaves | Alloxanthin, β,β-Carotene, 9′-cis-Neoxanthin, Diadinoxanthin, Diatoxanthin, Fucoxanthin, Lutein, Myxoxanthophyll, Peridinin, Violaxanthin | TLC Silica gel 60; 20 × 20 cm aluminum sheets | 0.8% n-PA in light PE (v/v) | UV-Vis (350–750 nm, 390–710 nm, 400–700 nm); Handheld UV lamp; JENWAY 7315 spectrophotometer | [37] |

| Dietary supplements | Lutein, zeaxanthin | TLC Si60 F254s glass plates | n-hept:EtOAc (9:1, v/v) and n-hept:Ac: EtOAc (55:25:20, v/v/v) sequentially | UV detection (450 nm) with densitometry; BMD-TLC combined with HPLC–DAD–ESI–MS | [38] |

| Dietary supplements and fruit juices | β-Carotene | TLC Aluminiumoxid 60 F254 neutral | CH3Cl:MeOH:Ac:NH4OH (10:22:53:0.2, v/v/v/v) | Densitometric detection at 450 nm using TLC Scanner 3 (CAMAG, Muttenz, Swirzerland) with Cats 1.3.4 software | [39] |

| Phoenix sylvestris fruit epicarp | β-carotene, lutein | HPTLC Silica Gel 60 F254, 10 × 20 cm plates | PE (60–80 °C): Ac (70:30, v/v) | UV detection at 450 nm, densitometry | [40] |

| various spices, pastes, sauces, and palm oils | Carotenoids (unspecified), for authentication | HPTLC Silica Gel 60 Nano-SIL-PAH caffeine-impregnated plates | Isohex–EMK (5:1, v/v) | UV-Vis detection, post-chromatographic UV irradiation, HPTLC-vis-HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS | [41] |

| Haloferax larsenii NCIM 5678 (isolated from Pachpadra Salt Lake, Rajasthan) | Bacterioruberin and its derivatives | Silica gel F254 TLC plate | ACO:n-hept (50:50, v/v) | UV-Vis detection (460, 490, 520 nm) | [42] |

| Orange peel waste | ζ-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, other carotenoids | HPTLC Silica Gel 60 F254 plates | Cyclohex–MTBE (various ratios, v/v) | UV-Vis detection (200–500 nm); Densitometry at 450 nm | [43] |

| Shrimp (Penaeus semisulcatus, Fenneropenaeus indicus, Metapenaeus ensis, Penaeus monodon) | Astaxanthin, β-carotene, zeaxanthin | Silica Gel G TLC plates | EtOAc:hex (7:7, v/v) | UV-Vis detection (461 nm); TLC analysis (Rf values 0.65, 0.85) | [44] |

| Sample | Analyte | Stationary phase | BPR Bar | T °C | MP | Detector | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemp Seed Oil and Waste Fish Oil | α-tocopherol, β-tocopherol, γ-tocopherol, δ-tocopherol, ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol | HSS C18 SB (3.0 × 100 mm; 1.8 μm). | 124.1 | 35 | MeOH + CO2 | DAD | [47] |

| Microalgae, rosehip. | α-carotene, β-carotene, lycopene, canthaxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, neoxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, astaxanthin, and violaxanthin. | 1-AA (3.0 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm). | 160 | 35 | MeOH + CO2 | PDA–QTOF MS | [48] |

| Dietary supplements | α-tocopherol, α-tocotrienol, β-tocopherol, β-tocotrienol, γ-tocopherol, γ-tocotrienol, δ-tocopherol, δ-tocotrienol, tocopherol acetate. | BEH-2-EP (3.0 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm). | 130 | 50 | MeOH + CO2 | DAD | [49] |

| Capsicum chinense (Habanero pepper) | Apocarotenoids (10) | Ascentis Express C30 (150 × 4.6 mm, 2.7 µm) | 150 | 35 | MeOH + CO2 | APCI-QqQ/MS | [50] |

| Egg yolk (from laying hens supplemented with β-carotene) | β-Carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin | Venusil XBP C30 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) | 160 | 60 | IPA + CO2 | DAD-MS/MS | [51] |

| Carotenoid | Food Source | Determination | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene | Tomatoes, Microalgae, rosehip | HPLC-DAD UHPLC-DAD SFC-PDA-QTOF MS | [8,45] |

| β-Carotene | Tomatoes, Sweet Pepper, Soybean, Peach Palm, Maize (Zea mays L.), Microalgae, rosehip, orange peel, Phoenix sylvestris fruit epicarp | HPLC-DAD HPLC-PAD-MS/MS HPLC-UV-VIS SFC-PDA-QTOF MSHPTLC-UV | [8,21,37,40,45,92,93,94] |

| Lutein | Tomatoes, Soybean, Goji Berry, Durum Wheat Pasta, Microalgae, rosehip, Phoenix sylvestris fruit epicarp | HPLC-DAD HPLC-UV-VIS SFC-PDA-QTOF MS HPTLC-UV | [12,21,37,40,45,95,96] |

| Zeaxanthin | Sweet Pepper, Soybean, Goji Berry, Microalgae, rosehip | HPLC-PAD-MS/MS HPLC-UV-VIS SFC-PDA-QTOF MS | [21,45,92,95] |

| Capsanthin | Sweet Pepper, Chili Peppers | HPLC-PAD-MS/MS HPLC-UV/Vis | [92,97] |

| Astaxanthin | Microalgae, rosehip | HPLC-MS SFC-PDA-QTOF MS | [45,95] |

| γ-Carotene | Peach Palm | HPLC-DAD | [93] |

| Extraction | Advantages | Limitations | Extracted Carotenoids | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | Simple, widely used, effective for lipophilic carotenoids | High solvent consumption, environmental concerns, potential for oxidation and carotenoid degradation | β-carotene, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin, phytoene, phytofluene, violaxanthin, neoxanthin | [57,58] |

| UAE | Reduced time, lower solvent use, enhanced mass transfer | Ultrasound intensity and frequency must be optimized, risk of oxidation due to cavitation effects | β-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, astaxanthin, lycopene, canthaxanthin, neoxanthin | [5,73,74,75,76] |

| MAE | Highly selective, fast, efficient, improved extraction yields | Heat-sensitive carotenoids may degrade, potential formation of cis-isomers, solvent selection is critical | β-carotene, lutein, lycopene, violaxanthin, zeaxanthin, canthaxanthin, capsanthin | [8,70,71,81] |

| SFE | Use of sostainable solvent (CO2), high purity, solvent-free extraction | Expensive equipment, requires specific pressure and temperature control for optimal yield | Lycopene, β-carotene, phytoene, phytofluene, lutein, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin | [77,78,79,80] |

| EAE | Mild conditions, environmentally friendly, preserves carotenoid bioactivity | Long extraction times, enzyme cost, enzyme specificity affects efficiency, limited applications | Lutein, β-carotene, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, astaxanthin, neoxanthin, antheraxanthin | [80,82,83] |

| PEF | Enhances cell permeability, facilitates solvent penetration, low energy input | Requires optimization for each matrix, may not be effective for all carotenoid-rich tissues | Lutein, β-carotene, zeaxanthin, capsanthin, astaxanthin, lycopene, neoxanthin | [84,110,120] |

| HHPE | Effective for cell disruption, moderate temperatures prevent degradation, retains bioactivity | High-pressure equipment required, limited scalability, requires precise control of pressure conditions | Lutein, β-carotene, astaxanthin, zeaxanthin, lycopene, phytoene, phytofluene | [81,82] |

| SWE | Comparable to solvent efficiency, avoids organic solvents, effective for polar carotenoids | High temperatures can degrade carotenoids, may favor cis-isomerization, risk of oxidation if not properly controlled | Lutein, β-carotene, violaxanthin, neoxanthin, zeaxanthin, canthaxanthin, astaxanthin | [85,121] |

| OH | Uniform heating reduces oxidation risk, enhances mass transfer | Requires specialized equipment, temperature control is critical to prevent carotenoid isomerization | β-carotene, lycopene, astaxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, capsanthin | [86,122] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurek, M.A.; Aktaş, H.; Pokorski, P.; Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Custodio-Mendoza, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of Analytical Approaches for Carotenoids Assessment in Plant-Based Foods: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073506

Kurek MA, Aktaş H, Pokorski P, Pogorzelska-Nowicka E, Custodio-Mendoza JA. A Comprehensive Review of Analytical Approaches for Carotenoids Assessment in Plant-Based Foods: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(7):3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073506

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurek, Marcin A., Havva Aktaş, Patryk Pokorski, Ewelina Pogorzelska-Nowicka, and Jorge A. Custodio-Mendoza. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review of Analytical Approaches for Carotenoids Assessment in Plant-Based Foods: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions" Applied Sciences 15, no. 7: 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073506

APA StyleKurek, M. A., Aktaş, H., Pokorski, P., Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E., & Custodio-Mendoza, J. A. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Analytical Approaches for Carotenoids Assessment in Plant-Based Foods: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions. Applied Sciences, 15(7), 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15073506