GIS-Based Analysis of Distribution Patterns and Underlying Motivations of Prehistoric Settlements in the Middle and Lower Yuanjiang River Basin, Central China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. GIS-Based Analysis Method

3. Results

3.1. Patterns of Prehistoric Settlement Distribution Across Different Periods

3.2. Spatial–Temporal Evolution

4. Discussion

4.1. Geographic Context Controlling the Spatial–Temporal Distribution

4.1.1. Topographic Feature in Relation to Prehistoric Settlements

4.1.2. Distance Away from the River

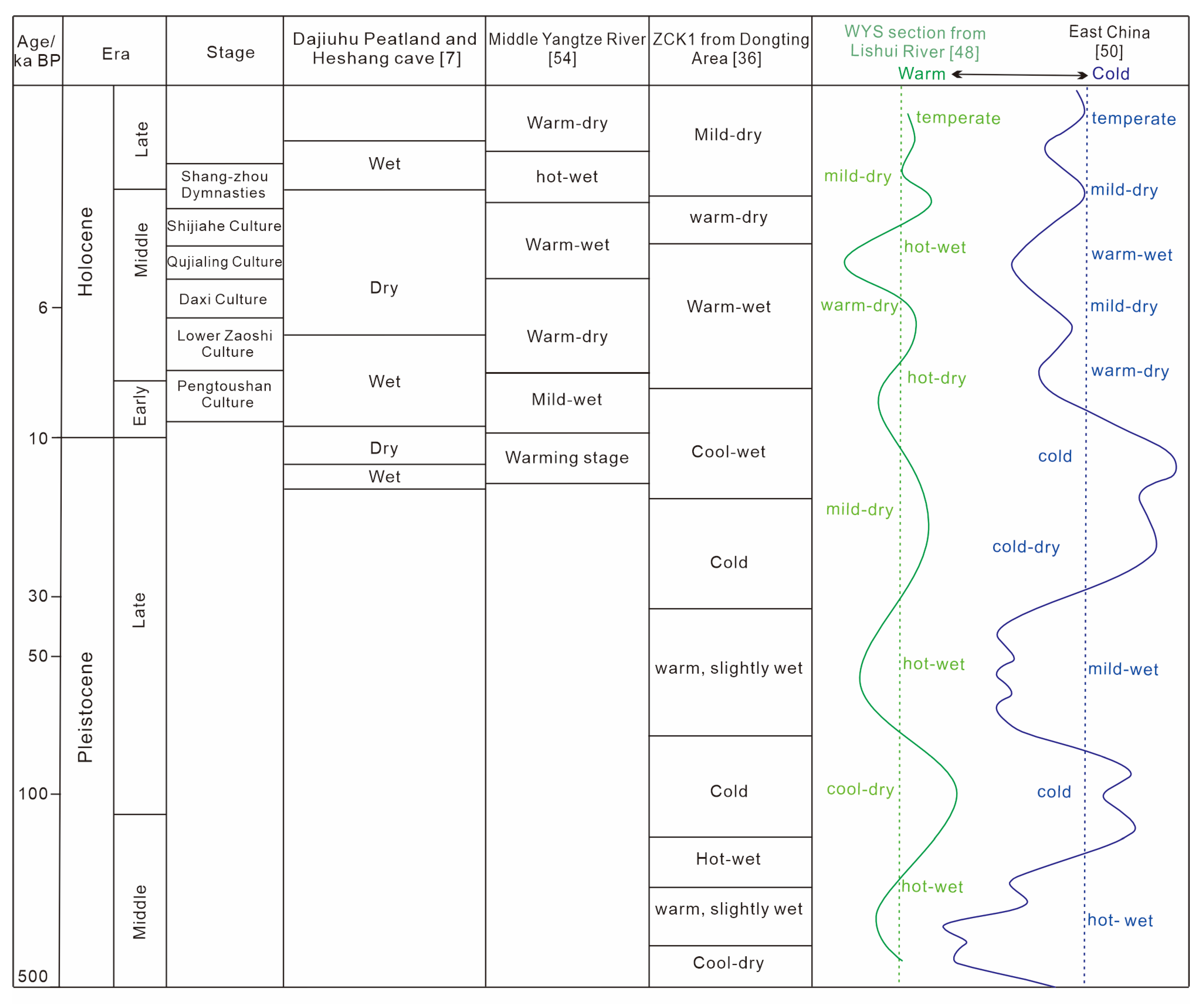

4.2. Climate Variations in Linkage to Prehistoric Occupation

4.3. Attribution of Ancient Cultural Groups

4.4. Regional Implications of Ancient Culture Lineages in the Middle Yangtze Catchmen

| Area | Early Paleolithic | Middle Paleolithic | Late Paleolithic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jianghan Plain [61] | Large tools including chopping implements, pointed tools, stone balls, and scrapers in the third–fourth-level terraces in Hanshui catchment | Large tools, such as chopping tools, pointed tools, and stone balls in the second- or third-level terraces in Hanshui catchment | Lightweight scrapers and small stone flakes (indicative of miniaturization) in Jianghan Plain |

| Along the Yangtze River [27] | --- | Large chopping and scraping tools in caves along the river | --- |

| Lishui River [33] | Large chopping tools, pointed tools, and scrapers in the third- or fourth-level terraces in middle-lower Lishui River | Large chopping tools, triangular pointed tools, stone balls, and others in the second- or third-level terraces in the middle-lower Lishui River | Sharp-shaped scrapers, standard scrapers, and small stone flakes indicative of iniaturization in the second- or first-level terraces in the middle-lower Lishui River |

| Yuanjiang River [41,62] | Large-sized chopping and scraping tools in the third- and second-level terraces in the middle Yuanjiang River | Large long-bodied side-blade choppers and double-sided blade choppers found in the second-level terraces of the middle Yuanjiang River | Large short-bodied sharp-edged choppers in the first or second-level terraces |

5. Conclusive Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timmermann, A.; Friedrich, T. Late Pleistocene climate drivers of early human migration. Nature 2016, 538, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.; Wang, H.W.; Wang, X.Q.; Zhou, J.; Ma, C.; Dai, X.Y. The study of early human settlement preference and settlement prediction in Xinjiang, China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curdy, P. Prehistoric settlement in middle and high altitudes in the Upper Rhone Valley (Valais-Vaud, Switzerland): A summary of twenty years of research. Preist. Alp. 2007, 42, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Da, H.B. The Research on the Relations Between Culture and Ecological Environment of Neolithic Age in the Middle Reaches of Yangtze River. Ph.D. Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2009. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.C.; Han, L.Y.; Zhang, G.M.; Su, Z.Z.; Zhao, Y.F. Temporal-spatial variations of human settlements in relation to environment change during the Longshan culture and Xia-Shang periods in Shanxi Province, China. Quat. Int. 2017, 436, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, J.Q.; Mo, D.W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Jiang, J.Q.; Liao, Y.N.; Lu, P.; Ren, X.L. Holocene geomorphic evolution and settlement distribution patterns in the mid-lower Fen River basins, China. Quat. Int. 2019, 521, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Evershed, R.P.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Pancost, R.D.; Meyers, P.A.; Gong, L.; Hu, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Concordant monsoon-driven postglacial hydrological changes in peat and stalagmite records and their impacts on prehistoric cultures in central China. Geology 2013, 41, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Ha, B.B.; Wang, S.J.; Chen, Z.J.; Ge, J.Y.; Long, H.; He, W.; Da, W.; Nian, X.M.; Yi, M.J.; et al. The earliest human occupation of the high-altitude Tibetan Plateau was 40 thousand to 30 thousand years ago. Science 2018, 362, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, R.D.; Simmons, A.H. Prehistoric occupation of late Quaternary landscapes near Kharga Oasis, Western Desert of Egypt. Geoarchaeology 2001, 16, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magny, M. Holocene climate variability as reflected by mid-European lake-level fluctuations and its probable impact on prehistoric human settlements. Quat. Int. 2004, 113, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoll, K. Recent environmental changes and prehistoric human activity in Egypt and Northern Sudan. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, Y.; Fujiki, T.; Nasu, H.; Kato, M.; Morita, Y.; Mori, Y.; Kanehara, M.; Toyama, S.; Yano, A.; Okuno, M.; et al. Environmental archaeology at the Chengtoushan site, Hunan Province, China, and implications for environmental change and the rise and fall of the Yangtze River civilization. Quat. Int. 2004, 123–125, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Zong, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, H.; Chen, J. Migration patterns of Neolithic settlements on the abandoned Yellow and Yangtze River deltas of China. Quat. Res. 2008, 70, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, Z.Y.; Sun, Q.L.; Finlayson, B. Migration of Neolithic settlements in the Dongting Lake area of the middle Yangtze River basin, China: Lake-level and monsoon climate responses. Holocene 2011, 22, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, F.; Zhu, C.; Li, L.; Li, B. Holocene environmental change and archaeology, Yangtze River valley, China: Review and prospects. Geosci. Front. 2012, 3, 875–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.J. Investigation of ancient cultural sites in the middle and lower reaches of the Yuanjiang River in Hunan. Archaeology 1980, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, D.H. Survey report on Paleolithic materials in the lower reaches of the Yuanjiang River. Hunan Archaeol. J. 1994, 8–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, D.H.; Xu, X.L.; Ma, Y.H. Second survey report on Paleolithic tools in the lower reaches of the Yuanshui River. Archaeology 1997, 41–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, J.J. A century review of Hunan archaeology. Archaeology 2001, 4, 3–12, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- He, J.J. The Neolithic culture in the Dongting Lake area. J. Archaeol. 1986, 385–408, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.J.; Liu, C.Z. Overview of the Paleolithic culture in Shangbao, Huxi County, Western Hunan. J. Jishou Univ. Soc.Sci. 1990, 12, 110–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, D.H.; Lei, F. Prehistoric archaeological review in northwest Hunan in the past ten years. Jianghan Archaeol. 1993, 30–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.S. A brief discussion on the stone age culture on the north shore of Dongting Lake. Southeast Cult. 1994, 6, 59–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, K.W. Exploration of Beiqiu Site in the middle reaches of the Yuanjiang River. J. Huaihua Teach. Coll. 1998, 17, 39–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, D.H. Discussion on Paleolithic remnants along lower reaches of Yuan River. Jianghan Archaeol. 2002, 41–49, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.C.; Lv, J.M.; Qi, S.M.; Yu, J.S.; Yu, P.R. Human sites and ecological survey in northwest area of Hunan Province. J. Jishou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2007, 28, 117–120, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.M. Culture and Society on Liyang Plain and Handong Area During the Neolithic Period; Central Relics Press: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 1–336. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.S. From Huzhao Mountairo Tangjiagang: A study on ‘Huxiang Characteristics’ in the Process of Prehistoric Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2022. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Chinese Cultural Relics. The Atlas of Chinese Cultural Relics, Branch of Hunan Province; Cartographic Press of Hunan: Changsha, China, 1997; pp. 1–542. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y. Neolithic sites and historical environment in the Dongting Lake area. J. Cent. Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2002, 36, 516–520, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.Q. Distribution and Migration of Paleoculture Sites in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yuanjiang River. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geoscience, Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.M. Archaeological observation of the prehistoric era in Hunan Province. Yueshan J. 2022, 89–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.C. Correlations Between Archaeological Culture and Natural Environment in the Lishui River Basin. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hunan Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources. Hunan Regional Geology; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1988; pp. 1–718. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.M. On the new tectogenesis of northwestern Hunan. Hunan Geol. 1988, 7, 64–72, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bai, D.Y.; Li, C.A.; Chen, D.P.; Zhou, K.J.; Huang, W.Y. Geochemical recording of sediments responding to the Quaternary climatic evolution in Dongting Basin. J. Shandong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 31, 1–9, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shan, X.J.; Deng, Q.H. Shijunshan site in Yuajiang County. Archaeology 1984, 846–848. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Deng, B.H. On the formation and development of ethnic towns in western Hunan. J. Jishou Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 1986, 19–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, G. Neolithic site at Gaokanlong, Huaihua. J. Archaeol. 1992, 301–328. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.R. A brief discussion on several issues of the Paleolithic era in Hunan Province. In Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Meeting of the Chinese Archaeological Society; Cultural Relics Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1992; pp. 1–12. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.R. Regional types and status of Paleolithic culture in Hunan Province. Proceedings of the Second Asian Civilization Academic Symposium on Prehistoric Culture in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River. Yuelu Bookstore 1996, 20–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- State Administration of Cultural Heritage. Cultural Relics Maps of China: Hunan Province; Map Press of Hunan: Changsha, China, 1997; pp. 1–772. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mo, L.H.; Xu, J.L. Excavation of the paleolithic sites of Shiwuxi, Antian, and Changleping in Xinhuang County of Huaihua City, Hunan Province. Hunan Archaeol. Ser. 2018, 8, 7–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.B.; Wu, B. Research on the Culture of the Yuanjiang River Basin; Social Science Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 1–205. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.; Xie, S.Y.; Kuang, M.S. Geomorphic evolution of the Yangtze Gorges and the time of their formation. Geomorpholology 2001, 41, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y.M.; Yang, G.F.; Zhang, X.J.; Tian, M.Z.; Chen, A.Z.; Ge, Z.L.; Ni, Z.Y.; Yang, Z. Timing of Zhangjiajie sandstone landforms: Evidence from fluvial terraces and karst cave. Geol. Rev. 2011, 57, 118–124, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.F.; Zhang, X.J.; Tian, M.Z.; Brierley, G.; Chen, A.Z.; Ping, Y.M.; Ge, Z.L.; Ni, Z.Y.; Yang, Z. Alluvial terrace systems in Zhangjiajie of northwest Hunan, China: Implications for climatic change, tectonic uplift and geomorphic evolution. Quat. Int. 2011, 233, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.F.; Yao, C.H. Prehistoric cultural migration in the middle–lower Lishui Catchment of Central China in response to environmental changes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fang, M.X. The stages and zoning of paleolithic culture in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Archaeol. J. 2020, 21–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.R.; Xu, X. Quaternary environmental changes in eastern China. J. Nanjing Univ. Nat. Sci. 1980, 1, 121–144, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.P.; Wu, J.M. The relationship between the distribution of Neolithic sites in the Dongting Lake area and changes in an ancient environment. Southeast Cult. 1998, 119, 35–39, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.Z.; Mo, D.W.; Li, X.P. Research on the Quaternary laterite and paleoclimate in the Dongting Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2005, 23, 130–137, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Liu, H.; Wu, L.; McCloskey, T.A.; Li, K.F.; Mao, L.M. Linking the vicissitude of Neolithic cities with mid-Holocene environment and climate changes in the middle Yangtze River, China. Quat. Int. 2014, 321, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Cai, S.M.; Sun, S.C. Evolution of Dongting Lake since Holocene. J. Lake Sci. 1994, 6, 13–21, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.J.; Sun, Q.L.; Chen, J.; Li, M.T. Spatial characteristics of climate around 4.0 ka BP and its impacts on the evolution of prehistoric civilization in China. Geol. Rev. 2013, 59, 248–266, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H. Global megadrought, societal collapse and resilience at 4.2–3.9 ka BP across the Mediterranean and West Asia. Glob. Change Mag. 2016, 24, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.; Chen, L. The 4.2 ka BP climatic event and its cultural responses. Quat. Int. 2019, 521, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.L. The Study on the Sacrificial Remains in the Region West of Dongting Lake and Handong Area During the Neolithic Period. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Ji’nan, China, 2012. (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.G.; Zhu, C.; Zhong, Y.S.; Yin, P.L.; Bai, J.J.; Sun, Z.B. Relationship between the temporal-spatial distribution of archaeological sites and natural environment from the Paleolithic Age to the Tang and Song Dynasties in the Three Gorges Reservoir of Chongqing area. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.S.P.; Mo, D.W. Holocene hydro-environmental evolution and its impacts on human occupation in Jianghan-Dongting Basin, middle reaches of the Yangtze River, China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.F. Preliminary study on Paleolithic culture in Hubei Province. Huaxia Archaeol. 2002, 13–22, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.R. A study on the transition from Paleolithic culture to Neolithic culture in the western plain of Dongting Lake. Archaeological Study 2008, 317–332. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.S. A preliminary discussion on the primitive culture of the Xiangjiang River Basin. Relics South 1999, 51–63, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

| River | Terrace Level | Height/m a.s.l. | Height/m a.r.l. | Age/ka |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maoxi River from the middle Lishui River [47] | T7 T6 T5 T4 T3 T2 T1 | 311 297 272 256 235 206 188 | 136 122 94–100 78–83 57–62 28–33 10–15 | 928 ± 92 (ESR) 574 ± 57 (ESR) 689 ± 68 (ESR) 347 ± 34 (ESR) 151.05 ± 12.84/201.24 ± 17.11 (TL) 60.95 ± 5.18 (TL) Qh |

| Suoxi River from the middle Lishui River [46,47] | T4 T3 T2 T1 | – 205 188 173 | – 55 28 13 | Qp2-2 104.45 ± 8.88 (TL)/117.62 ± 9.99 (TL) Qp3 Qh |

| Middle-lower reaches of the Lishui River [48] | T4 in Huzhuashan site T3 in Houerpo site T2 in the Wuyashan site T1 in Yanerdong site | 95 80 55 40 | 63 40 22 13 | 500 ± 50 (ESR) 200 ± 15 (ESR) 57.8 ± 5.0 (ESR) 20-30 ± 2.0 (ESR) |

| Yuanjiang River [35,41] | T6 T5 T4 T3 T2 T1 | – – – – – – | 120–140 80–87 78 38 16 10 | Early Early Pleistocene Late Early Pleistocene Early Middle Pleistocene Middle Middle Pleistocene Late Middle Pleistocene Late Pleistocene |

| Yuanjiang River (our study) | T5 T4 T3 T2 T1 | – – – – – | 80–110 71–82 34–46 14–21 8–14 | Late Early Pleistocene 470 ± 47 (ESR) 151–305 ± 20 (ESR) 56–58 ± 5.0 (ESR) 9–31 ± 2.0 (ESR) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, G.; Yao, C. GIS-Based Analysis of Distribution Patterns and Underlying Motivations of Prehistoric Settlements in the Middle and Lower Yuanjiang River Basin, Central China. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15042064

Yang G, Yao C. GIS-Based Analysis of Distribution Patterns and Underlying Motivations of Prehistoric Settlements in the Middle and Lower Yuanjiang River Basin, Central China. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(4):2064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15042064

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Guifang, and Changhong Yao. 2025. "GIS-Based Analysis of Distribution Patterns and Underlying Motivations of Prehistoric Settlements in the Middle and Lower Yuanjiang River Basin, Central China" Applied Sciences 15, no. 4: 2064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15042064

APA StyleYang, G., & Yao, C. (2025). GIS-Based Analysis of Distribution Patterns and Underlying Motivations of Prehistoric Settlements in the Middle and Lower Yuanjiang River Basin, Central China. Applied Sciences, 15(4), 2064. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15042064