1. Introduction

The rind of grapefruit (

Citrus paradis, GF) accounts for 30–50% (

w/

w) of the total fruit weight [

1]. The GF juice industry produces considerable quantities of byproducts. To utilize citrus juice residues effectively, research on the extraction and functional evaluation of the polysaccharide pectin has recently been conducted. Pectin has potential applications as a gelling agent, thickener, and nutritional supplement in cosmetics and as a nutritional supplement [

2].

The conventional pectin extraction method involves the creation of an acidic environment using solvents such as hydrochloric, sulfuric, or nitric acid, followed by prolonged heating. Although this method is industrially cost effective, it requires large volumes of acidic solvents, which raises environmental concerns. Furthermore, the application of strong acids and heat treatment has been observed to induce pectin degradation [

3]. Pressurized carbon dioxide (pCO

2) extraction results in the highest pectin yield and molecular weight (MW) among the citrus residues from GF pomace [

4]. The pCO

2 extraction combined with sodium oxalate enabled the recovery of up to 40% of pectin. pCO

2 lowers the pH to solubilize pectin, and sodium oxalate acts as a chelating agent, binding calcium ions, and thereby promoting extraction [

5]. However, lignocellulose (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) remained after pectin extraction. Achieving complete utilization of these resources necessitates the development of an effective lignocellulose utilization method. Therefore, alternative methods for the effective utilization of GF juice residues beyond conventional pectin extraction techniques should be investigated.

Cellulose, a major component of plant cell walls, is an abundant and environment-friendly resource. Nanofibrillation increases the surface area, making it potentially suitable for applications such as emulsifiers and biodegradable composite films [

6,

7]. Lignin consists of nonpolar hydrocarbons and phenyl groups and is retained within nanocellulose, thereby enhancing its hydrophobicity and thermal stability [

8]. However, the removal of lignin and hemicellulose by chemical treatment is believed to substantially alter the structure of entangled lignocellulose. This alteration, in turn, changes the surface charge and improves cellulose nanofibers (CNF) dispersibility. In the case of nanofibers (NF), sonication was used as the “green” mechanical technique. This process utilizes the ultrasonic cavitation phenomenon, wherein the collapse of bubbles and resulting pressure fluctuations promote the nanofibrillation of cellulose fibers [

9].

The objective of this study was to investigate the production of lignocellulose nanofibers (LCNF) and CNF using GF juice residue and lignocellulose derived from GF juice residue processed using the pCO2 extraction method, which achieved the highest yield. The properties of the products were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Juice residues were prepared as described by Pattarapisitporn et al. [

5]. The residue remaining after juicing commercially available GF was washed five times with tap water to remove pigment components and sugars. The washed residue was dried in a dry oven at 60 °C for 24 h and then was pulverized using a grinder (Mini Speed Mill, MS-09, Labonect Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

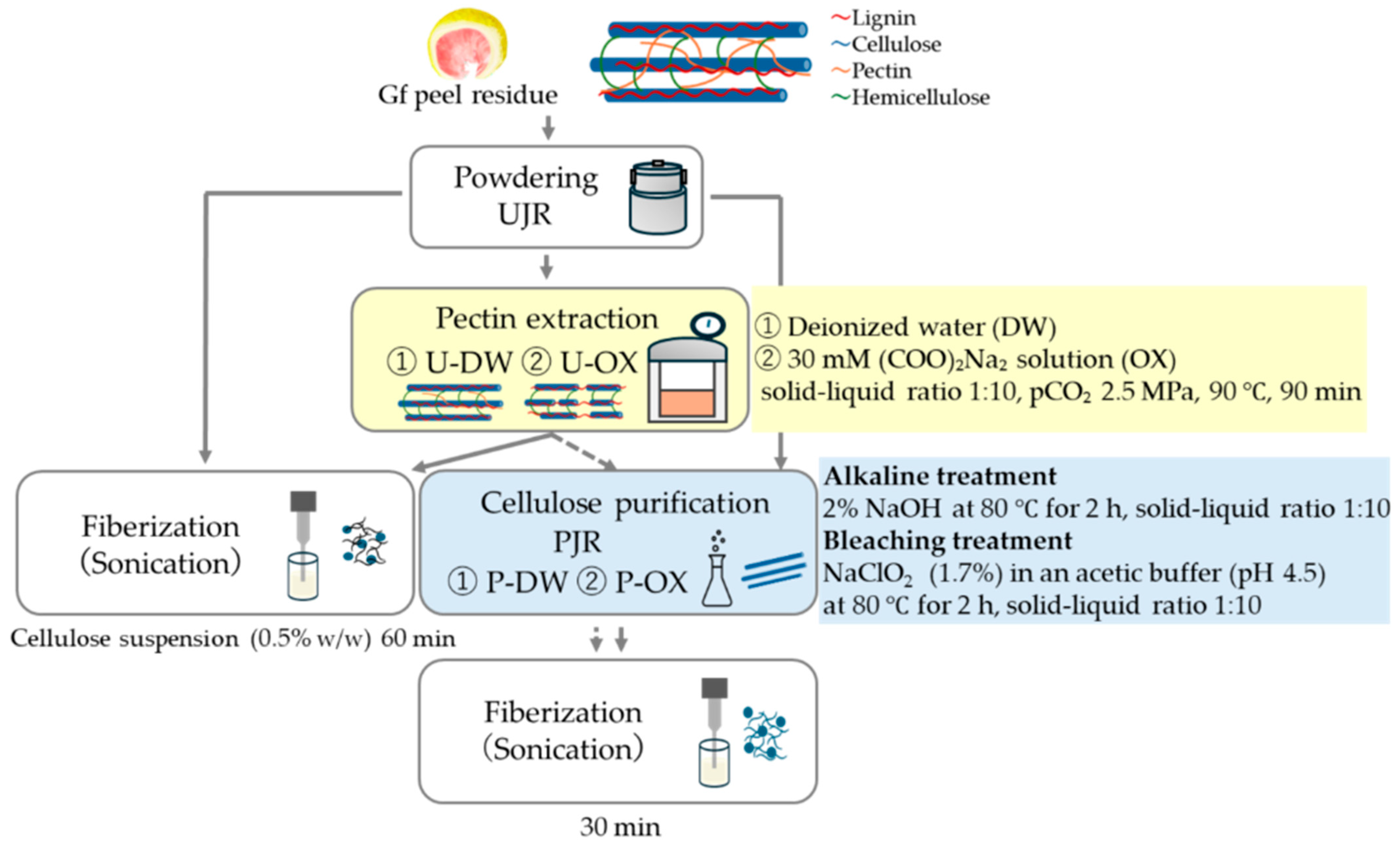

2.2. Preparation of LCNF and CNF

Six types of samples were prepared. The dried juice residue was designated untreated juice residue (UJR). The residues remaining after pectin extraction using pCO2 treatment in deionized water (DW) and sodium oxalate solutions (OX) were designated U-DW and U-OX, respectively. The residue obtained after cellulose purification was named PJR. The cellulose purification process was applied to both DW and OX, designated as P-DW and P-OX, respectively.

2.2.1. Pectin Extraction Using pCO2 and Cellulose Purification of the Residue

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the sample preparation process. Pectin was extracted using the procedure described by Pattarapisitporn et al. [

5]. Briefly, 30 mL of the solvent (deionized water or 30 mM sodium oxalate solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan)) was added to 1 g of juice residue powder and mixed. The suspension was placed in a pressure vessel [

10] and extracted under pCO

2 at 2.5 MPa and 90 °C for 90 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 12,000×

g and 4 °C for 15 min after cooling in an ice bath. The resulting supernatant was discarded to obtain the residue. The oil and pigment components of the residue were extracted as described by Taboada et al. [

11]. The residue was mixed with 85% (

v/

v) ethanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) (solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10) and heated at 85 °C for 20 min. The residue was recovered by centrifugation (26,740×

g, 4 °C, 10 min) and re-extracted with 85% ethanol. The extraction process was repeated until the supernatant was clear. Finally, the residue was washed with distilled water and recovered by centrifugation (26,740×

g, 4 °C, 10 min). This process was repeated five times.

2.2.2. Cellulose Purification

The cellulose was purified as described by Siqueira et al. [

12]. Firstly, 1 g of residue was heated in 10 mL of deionized water at 85 °C for 2 h. To remove hemicellulose, a 2% NaOH (sodium hydroxide) solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was added to the residue and heated at 80 °C for 2 h. To remove lignin, the residue was bleached with NaClO

2 (sodium chlorite) (1.7%) (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan) in acetic acid buffer (pH 4.5) at 80 °C for 2 h. After bleaching, the residue was washed with deionized water until the desired pH was reached.

2.2.3. Nanofiber Formation

The six residues were mixed with deionized water to obtain a final concentration of 0.5% (w/v). The mixture was subjected to ultrasonication (UD-200, TOMY SEIKO Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 200 W for 30 min for PJR, P-DW, and P-OX and for 60 min for UJR, U-DW, and U-OX.

2.3. Chemical Composition

The chemical compositions of UJR, U-DW, and U-OX were determined as described by Berglund et al. [

13], with minor modifications. Each sample (0.5 g) was boiled in ethanol for 15 min, and this process was repeated four times. The residue was then thoroughly washed with deionized water and dried overnight at 50 °C in a dry oven, and its 0.1 g (weight, A) was treated in 1 mL of 24% (

v/

v) KOH (potassium hydroxide) solution and incubated at 25 °C for 4 h, washed with deionized water, and dried again overnight at 50 °C. The weights of the dried samples (B) were measured. Fraction B was allowed to stand for 3 h at 25 °C in 72% (

v/

v) H

2SO

4 (sulfuric acid) solution for cellulose hydrolysis. Subsequently, 11.4 mL of deionized water was added, and the reaction was continued for 2 h at 80 °C in a 5% (

v/

v) H

2SO

4 solution. After the reaction, the mixture was washed with deionized water using centrifugation, and the residue was dried overnight in an oven at 50 °C and the weight was measured (C). The cellulose content was calculated as the difference in weight between B and C, the hemicellulose content as the difference between weights A and B, and the lignin content as the weight of C.

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT–IR)

The spectra of the six samples were measured using a Bruker Vertex 70v instrument (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) under ultrahigh-vacuum conditions. FT–IR spectra were recorded in transmission mode in the wave numbers 400–4000 cm

−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm

−1. To evaluate the changes in the crystalline structure and chemical composition, the lateral order index (LOI), which was used to estimate the relative crystallinity, was calculated according to Equation (1) [

14]:

where

A1427 and

A894 correspond to the absorbances of the crystalline band at 1427 cm

−1 and the amorphous band at 894 cm

−1, respectively.

The removal of hemicellulose and pectin (carbonyl index) was assessed using Equation (2):

where

A1735 and

A2900 correspond to the absorbances of the carbonyl band at 1735 cm

−1 and the reference band at 2900 cm

−1, respectively.

The lignin content was evaluated using the lignin index as per Equation (3) [

15]:

where

A1510 and

A2900 correspond to the absorbances of the aromatic skeletal vibration band at 1510 cm

−1 and the reference band at 2900 cm

−1, respectively.

2.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

The nanofiber suspensions in ethanol were dried at 25 °C for 24 h to obtain the film samples. A horizontal powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD-7000, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) was used for the analysis on six samples under the conditions; operating at 40 kV and 40 mA, scanning the angle range (2θ) from 10 to 40° at 2°/min. The cellulose crystallinity index (CrI) was obtained using the Segal equation:

where

represents the maximum intensity near 22° in the crystalline region, and

represents the minimum intensity near 18° in the amorphous region.

2.6. Zeta Potential and Average Particle Size Analysis

The zeta potential and the average particle size of each sample suspended in water were measured using a zeta potential and particle size measurement system (ELSZ-2Plus; Otsuka Electronics, Osaka, Japan). Each sample, at a concentration of 0.5%, was diluted to 0.1% using deionized water. The particle size distribution was measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS), and the average particle size was calculated from the number distribution.

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Each sample was observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM-6510, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Samples (0.5%) were suspended in deionized water, washed with acetone to reduce aggregation, and then freeze-dried. The samples were coated with platinum using an Autofine coater (JFC-1600, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Observations were performed under high vacuum at an acceleration voltage of 10 or 15 kV and a magnification of 10,000 or ×20,000. The widths of the recognizable fibers were measured using an image analysis software (HALO v2.3.2089.34, Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM, USA) [

16].

2.8. Physical Property Measurements

The physical properties of each sample were measured using a physical-property tester (RHEONER II RE2-33005B; Yamaden Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Measurements were performed using a 2-N load cell and a 16 mm diameter acrylic resin plunger. Two compressions were performed at a compression speed of 1.0 mm/s, with a compression ratio of 50%, storage pitch of 0.8 s, and a return distance of 10 mm. Each sample, at a concentration of 0.5%, was transferred to a stainless steel dish (diameter 40 mm × height 15 mm) and adjusted such that the top surface of the dish was leveled. Three measurements were performed for all samples, and the following parameters were determined: maximum force (N), adhesive force (N), gumminess force (N), and adhesion (J/cm3).

2.9. Measurement of Dye Adsorption Capacity

The adsorption test was conducted according to Mehdinejad et al. [

17] with minor modifications. The samples were suspended in aqueous solutions of 0.1% (

w/

w) methylene blue (MB) (Katayama Chemical Industries Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and Congo red (CR) (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and stirred at 250 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. After removal of the solid of each sample using centrifugation (2300×

g, 4 °C, 2 min), an absorbance of the supernatant was measured at wavelengths of 668 nm for MB and 497 nm for CR using a ultraviolet (UV)-visible spectrophotometer (V-730, Japan Spectroscopic, Tokyo, Japan). All experiments were repeated thrice.

The amounts of MB and CR adsorbed on the adsorbent (mg/g) and the percentage removal (%R) were calculated as follows:

where

C0 and

Ce (mg/L) are the MB and CR concentrations at the input and output of each experiment, V (L) is the initial solution volume, and m (g) is the adsorbent weight.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, JMP Student Edition 18.2.2 (869054) (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [

18] was used. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for three independent trials per treatment. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), based on a completely randomized design, followed by Tukey’s test for one-way multiple comparisons, was performed to determine significant differences (

p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of UJR, U-DW, and U-OX

Table 1 lists the chemical compositions of UJR, U-DW, and U-OX. Both UJR and U-DW had a higher cellulose content than hemicellulose or lignin (

p < 0.05), and their contents were equivalent (

p > 0.05). The composition of U-DW was similar to that of UJR (

p > 0.05). This suggests that pCO

2 treatment in deionized water had a minimal impact on the structural changes in the residue or on the hemicellulose and lignin content.

In contrast, the cellulose content of U-OX was lower than that of UJR and U-DW (

p < 0.05). Although the pectin yield was approximately 40%, the FTIR analysis of the extracted pectin did not reveal any spectral features indicative of cellulose. Instead, absorption bands corresponding to carbonyl groups derived from galacturonic acid, which are characteristic of pectin, were identified, demonstrating the high purity of the obtained pectin [

5]. The absence of cellulose in the extracted pectin, combined with the reduced cellulose content in the residue, suggests that the combined effects of pCO

2 and sodium oxalate promote the partial degradation or solubilization of cellulose, leading to low-molecular-weight fragmentation. This was likely removed during the ethanol washing process rather than by co-precipitation with pectin [

5,

19,

20,

21].

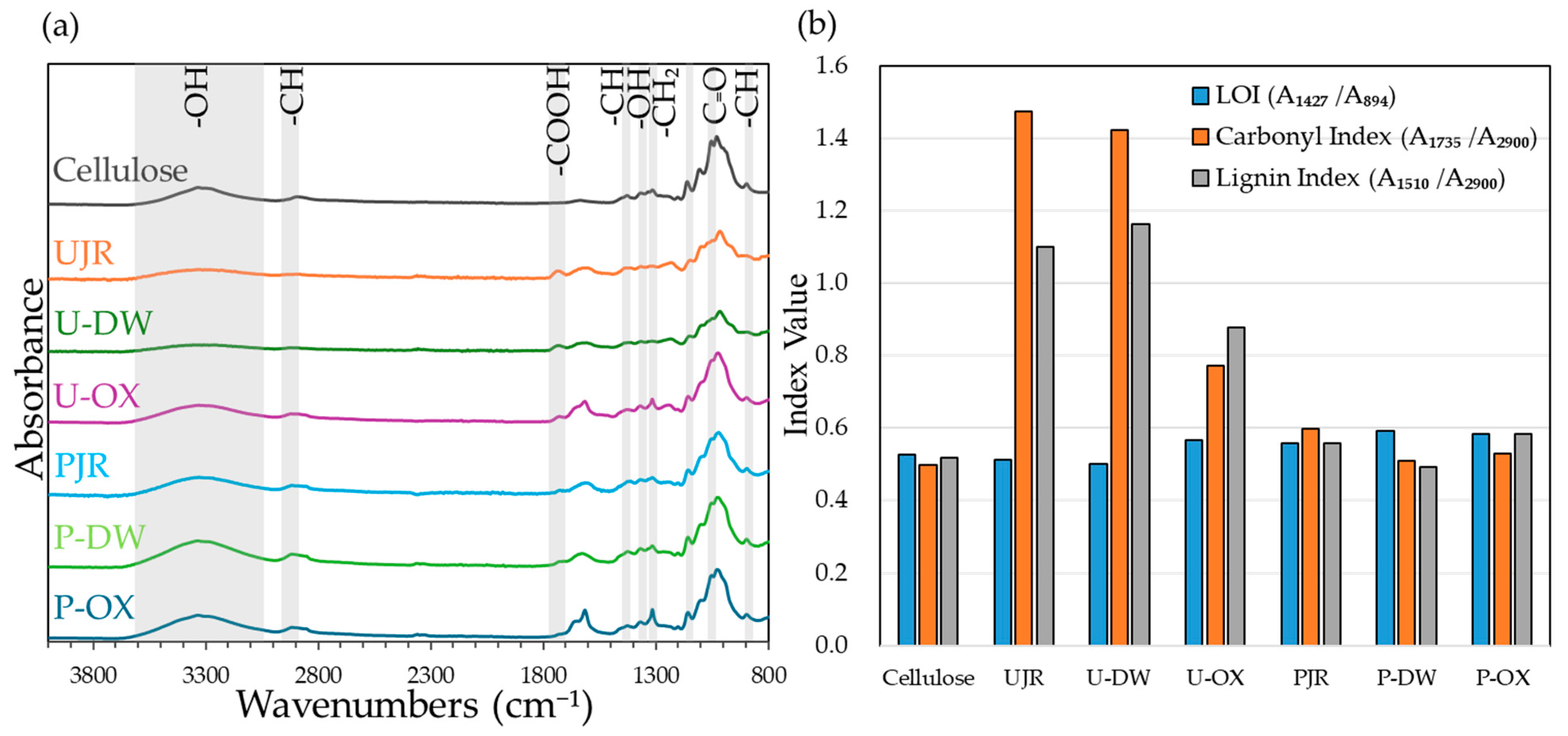

3.2. Chemical Group Structure with and Without Pectin Extraction and Cellulose Purification

Figure 2a shows the FT–IR spectra of the purified cellulose powder and six samples. For U-OX and cellulose-purified samples (PJR, P-DW, P-OX), the OH stretching vibrations originating from hydroxyl groups in the 3000–3650 cm

−1 range, CH stretching vibrations originating from methyl and methylene groups near 2900 cm

−1 were observed. In addition, characteristic peaks associated with cellulose structure were identified at 1427 cm

−1 for CH bending, and 1337 cm

−1 for OH in-plane bending, as well as 1317 cm

−1, 1161 cm

−1, 1056 cm

−1, and 894 cm

−1 [

22,

23]. These features indicate that the crystalline structure was preserved. Furthermore, the absorption at 1730–1740 cm

−1 originating from carbonyl groups was weak or negligible in the purified cellulose samples, indicating the effective extraction of pectin and the successful removal of hemicellulose and lignin through cellulose purification process.

Figure 2b shows the LOI, carbonyl index, and lignin index of each sample. Higher values indicate increased cellulose crystallinity, hemicellulose, and lignin content. The alterations in these indices support the findings shown in

Figure 2a.

Table 2 shows the CrI values of the purified cellulose powder and the six samples before and after sonication based on XRD analysis. Before sonication, U-OX exhibited a higher crystallinity than UJR and U-DW. This finding is supported by the FTIR results. This suggests that both pectin extraction and cellulose purification induced hydrolysis and removal of the non-crystalline cellulose regions during the extraction process, which concentrated the remaining crystalline regions. Furthermore, the crystallinities of both the purified cellulose powder and U-OX decreased after sonication for 60 min. This suggests that the 60 min treatment was excessive for these two types of samples, consequently leading to the destruction of the crystalline regions.

In contrast, the other samples exhibited increased crystallinity after sonication for 30 min and 60 min. This is likely because these samples contained more amorphous regions than purified cellulose powder and U-OX, and sonication preferentially destroyed the amorphous regions, inducing a relative increase in the crystalline regions without destruction. The combination of high crystallinity, cellulose purity before sonication, and short sonication time, or the opposite combination for these samples, meant that the treatment did not reach the stage of destroy the crystalline regions [

24].

3.3. Zeta Potential and Mean Particle Size

Table 3 lists the zeta potentials, average particle sizes, and polydispersity indices (PDI) of the six samples after sonication. For the samples with cellulose purification (PJR, P-DW, and P-OX), the absolute zeta potential values tended to be higher than those of the samples without cellulose purification (UJR, U-DW, and U-OX). PJR exhibited the highest value of −29.49 mV. During the bleaching process for cellulose purification, the improved dispersion stability may oxidize the aldehyde groups within cellulose into carboxyl groups. This chemical modification makes cellulose more prone to acquiring a negative charge, thereby increasing interparticle repulsion and preventing aggregation.

Furthermore, the average particle sizes of PJR (173.35 nm) and P-DW (85.35 nm) were smaller than those of the unpurified UJR and U-DW. Conversely, P-OX showed a smaller change in zeta potential than U-OX, and a tendency toward an increased average particle size. This suggests that the extraction of pectin with sodium oxalate and the high proportion of crystalline cellulose regions caused by purification may have resulted in aggregation because of insufficient dispersion stability after 30 min of sonication.

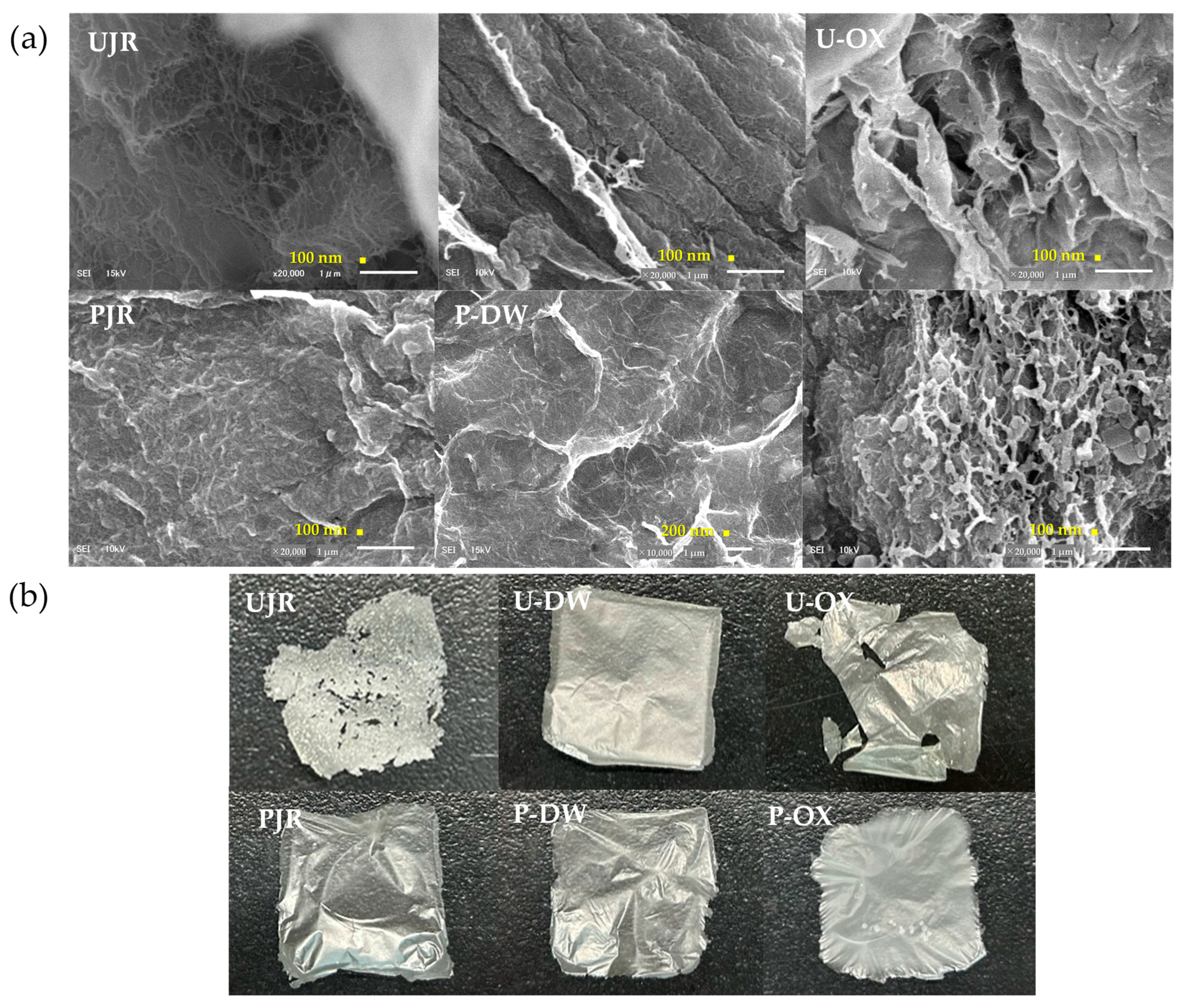

3.4. Surface Structure

Figure 3a shows the SEM images of the six samples after sonication. Extensive surface fibrillation was observed in both UJR and U-DW. The fiber width for UJR was 32.4 ± 5.6 nm, whereas that for U-DW was 50.6 ± 21.7 nm. Although distinct fiber structures were hardly to identify in U-OX, some measurable fibers were found, with widths of 59.9 ± 15.2 nm. This suggests that pectin extraction using pCO

2 with sodium oxalate decreases fiberization efficiency. A possible explanation for this result is that effective pectin extraction reduces cellulose content and increases crystallinity. Additionally, the partial degradation of comparatively high proportions of hemicellulose and lignin by sonication may have contributed to the decrease in fiberization efficiency [

25].

In the cellulose-purified samples, P-OX showed clear fiberization, with measured fiber widths of 39.6 ± 17.7 nm. P-OX had a distinctive surface structure with a high degree of fibrillation uniformity, even when compared with the other samples. In PJR and P-DW, distinct fiber formation was not clearly confirmed, whereas fibers smaller than 100 nm were observed. Although surface aggregation prevented a clear confirmation, it is possible that fibers smaller than 100 nm were formed on the surface.

Figure 3b shows the appearance of the film upon visual inspection after the sample preparation procedure. The prepared nanofiber suspended in ethanol was dried for 24 h at 25 °C for XRD analysis. Small aggregates were observed in the UJR, and the surface appeared rough. The films generated from U-DW, U-OX, and P-OX appeared to have smooth white surfaces; U-OX tended to tear more easily upon handling. PJR and P-DW exhibited smooth transparent surfaces. The mechanical strength improves with increasing cellulose content [

26]. Therefore, these films are expected to be useful as packaging materials and in other applications. Because lignocellulose contains lignin, which possesses UV absorption capacity [

8], the lignocellulose nanofilms obtained in this study could be used as UV-shielding materials.

3.5. Physical Properties

Figure 4a shows the photographs of the samples suspended in deionized water and dispersed by sonication. Each suspension was visually stable during the 12-day storage period. In addition, the physical properties of the samples, including maximum force, adhesion force, gumminess force (

Figure 4b), and adhesion force (

Figure 4c), were evaluated. The maximum force represents the peak force during the initial push-pull action, indicating hardness. The adhesion force measures strength during pulling, whereas the gumminess force reflects the hardness and cohesion of the internal structure.

Adhesion energy quantifies the energy required for adhesion, with higher values indicating greater adhesion. The purified cellulose samples (PJR, P-DW, and P-OX) showed higher values for all parameters than the unpurified cellulose samples. Statistical differences in adhesion were observed between UJR and PJR, and between U-OX and P-OX. This was because the increased repulsion between the negatively charged particles improved the dispersion stability, and the fibrils formed a three-dimensional network structure. In contrast, relatively high adhesion was observed for U-DW, even though it was a sample without cellulose purification. This aligns with the clear fibrillation observed on the surface by SEM. The fine fibrous structure enhanced water retention of the gel, resulting in high adhesion.

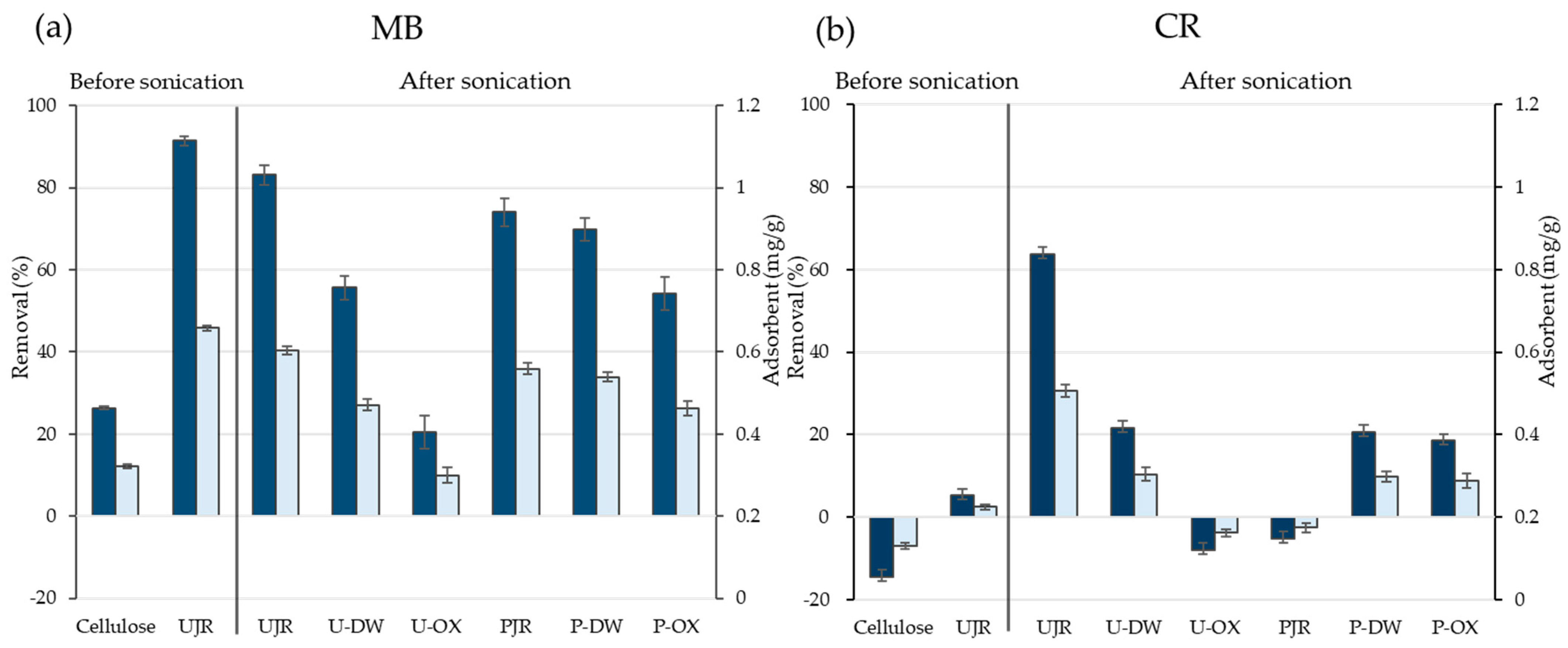

3.6. Pigment Adsorption

Figure 5a,b show the removal rates and adsorption capacities of each sample for MB and CR, respectively. The sonicated UJR exhibited a high removal rate and adsorption capacity for both MB and CR. A study of the adsorption capacity of unsonicated UJR showed a similarly high removal rate for MB but a low adsorption capacity for CR. This observation suggests that surface fibrillation owing to sonication increases the specific surface area, providing more adsorption sites for CR adsorption [

27]. In usual, decrease in average particle size induces increase in surface area, increasing adsorbent ability. However, such simple relationship was not observed in both MB and CR.

Compared to UJR, U-DW and U-OX exhibited lower MB removal efficiencies. This is likely because the extraction step leads to the loss of carboxyl groups from galacturonic acid residues prevalent in pectin, resulting in a less negative surface charge [

20]. Zeta potential measurements confirmed this reduced negative charge, which is believed to be the reason for lower MB adsorption.

In contrast, the surfaces of the cellulose-purified samples were more prone to negative charges, as suggested by the zeta potential results. For this reason, they showed a higher adsorption capacity for cationic MB, but a decrease in the adsorption capacity for anionic CR due to electrostatic repulsion. Although the average particle size showed that the NFs in group P were smaller than those in group U, the comparison between UJR and PJR suggested that a reduction in particle size does not necessarily improve surface adsorption. This observation indicates that the surface functional group structure and degree of fibrillation may have a greater effect on the adsorption performance than particle size.

4. Conclusions

This study describes the valorization of GF residue with a focus on cellulose purification and sonication and provides novel perspectives on the utilization of the residue. Our findings highlight the distinct application directions based on the treatment method.

First, sonication produced a fibrous structure, suggesting an increase in the surface area. The adsorption capacity of anionic substances was enhanced only by sonication. This suggests that sonication can substantially enhance the functionality of the waste products.

Second, the NF suspension prepared from the residue after pectin extraction enabled the formation of films containing lignin, suggesting potential UV absorption capabilities.

Finally, the NF suspension prepared by purifying cellulose exhibited a gel-like texture with increased hardness and adhesiveness and was able to form films with high crystallinity. These cellulose NFs also adsorb cationic substances.

As a result, juicing residues and products obtained through NF processing are promising biomass materials with the potential for diverse applications. In addition to their use as adsorbents for wastewater treatment, their compositional characteristics suggest potential applications beyond wastewater treatment. The lignin-containing NF suspension, known for its thermal stability and UV-absorbing properties, has excellent potential for use in active packaging (e.g., films for fresh food preservation) and as a natural ingredient in sunscreen. In contrast, the purified cellulose NF suspension exhibits high whiteness, increased hardness, and excellent adhesiveness, making it ideal for use as a food texture modifier, cosmetic base, and reinforcing filler in transparent composites. To advance these materials toward practical applications, future research must clarify their desorption and regeneration capabilities, tensile strength, ultraviolet absorption properties, biocompatibility, thermal stability, pH, and ionic strength.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I. and S.N.; methodology, M.I., A.P. and N.R.; validation, M.I.; investigation, M.I.; resources, A.P.; data curation, M.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I.; writing—review and editing, M.I., A.P. and S.N.; supervision, S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The research data used in this paper is stored at Saga University. It can be provided to researchers upon request.

Acknowledgments

Physical properties, FT-IR analysis, X-ray diffraction analysis, zeta potential/particle size measurements, SEM observations, ultrasonic treatment, and image analysis were conducted with support from the Analytical Research Center for Experimental Sciences, Saga University. We also acknowledge that the equipment used for the physical properties, FT-IR analysis, X-ray diffraction analysis, and zeta potential/particle size measurements was shared through the MEXT Project for promoting the public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (Program for supporting the introduction of the new sharing system), Grant Number JPMXS0422400025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| UJR | Untreated juice extraction residue |

| U-DW | Juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water |

| U-OX | Juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution |

| PJR | Purified cellulose from UJR |

| P-DW | Purified cellulose from U-DW |

| P-OX | Purified cellulose from U-OX |

References

- Xiao, Y.F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, G. Utilization of pomelo peels to manufacture value-added products: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 351, 129247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumuganainar, D.G.; Ramesh, D.L.; Pandurangan, P.; Sunkar, S.; Abraham, S.; Samrot, A.V.; Sainandhini, R.; Thirumurugan, A.; Moovendhan, M. Sustainable pectin extraction: Navigating industrial challenges and opportunities with fruit by-products—A review. Process Biochem. 2025, 154, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.S.; Muruganandam, L.; Moorthy, I.G. Pectin from fruit peel: A comprehensive review on various extraction approaches and their potential applications in pharmaceutical and food industries: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 9, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattarapisitporn, A.; Noma, S.; Klangpetch, W.; Demura, M.; Hayashi, N. Extraction of citrus pectin using pressurized carbon dioxide and production of its oligosaccharides. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattarapisitporn, A.; Nagatoshi, Y.; Klangpetch, W.; Hamanaka, D.; Inoue, N.; Noma, S. Enhanced extraction and functional characterization of pectin and pectic oligosaccharide from grapefruit residue using sodium oxalate-assisted pressurized CO2. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 9594–9614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Shen, H.; Yan, S.; Zhao, R.; Wang, F.; Shen, X.; Li, Z.; Yao, X.; Wang, Y. Application potential of wheat bran cellulose nanofibers as Pickering emulsion stabilizers and stabilization mechanisms. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Optimization of bleaching process for cellulose extraction from apple and kale pomace and evaluation of their potentials as film forming materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Gao, X.; Fang, X.; Huo, C.; Zhang, J. Corn Stover-derived nanocellulose and lignin-modified particles: Pickering emulsion stabilizers and potential quercetin sustained-release carriers. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Emerging technologies for the production of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuru, C.; Umada, A.; Noma, S.; Demura, M.; Hayashi, N. Extraction of Pectin from Satsuma Mandarin Orange Peels by Combining Pressurized Carbon Dioxide and Deionized Water: A Green Chemistry Method. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, E.; Fisher, P.; Jara, R.; Zúñiga, E.; Gidekel, M.; Cabrera, J.C.; Pereira, E.; Gutiérrez-Moraga, A.; Villalonga, R.; Cabrera, G. Isolation and characterisation of pectic substances from murta (Ugni molinae Turcz). Food Chem. 2021, 123, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, G.; Oksman, K.; Tadokoro, S.K.; Mathew, A.P. Re-dispersible carrot nanofibers with high mechanical properties and reinforcing capacity for use in composite materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 123, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, L.; Noël, M.; Aitomäki, Y.; Öman, T.; Oksman, K. Production potential of cellulose nanofibers from industrial residues: Efficiency and nanofiber characteristics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 92, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjarski, P.; Gawron, J.; Andres, B.; Obiedzinska, A.; Lisowski, A. FTIR Analysis of changes in chipboard properties after pretreatment with Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. Energies 2022, 15, 9101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Boyneburgk, C.L.; Heim, H.-P. Effect of changing climatic conditions on properties of wood textile composites. Materials 2025, 18, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HALO Software, Version 2.3.2089.34; SAS Institute Inc.: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2019. Available online: https://indicalab.com/halo/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Mehdinejad, M.H.; Mengelizadeh, N.; Bay, A.; Pourzamani, H.; Hajizadeh, Y.; Niknam, N.; Moradi, A.H.; Hashemi, M.; Mohammadi, H. Adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solutions by cellulose and nanofiber cellulose and its electrochemical regeneration. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 110, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JMP Student Edition, Version 18.2.2 (869054); SAS Institute, Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.jmp.com/ja/home (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Konwar, J.; Purkayastha, M.D.; Kalita, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Dutta, J. Current progress in valorization of food processing waste and by-products for pectin extraction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Henschen, J.; Ek, M. Esterification and hydrolysis of cellulose using oxalic acid dihydrate in a solvent-free reaction suitable for preparation of surface-functionalised cellulose nanocrystals with high yield. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 5564–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarno; Trisanti, P.N.; Airlangga, B.; Mayangsari, N.E.; Haryono, A. The degradation of cellulose in ionic mixture solutions under the high pressure of carbon dioxide. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 3484–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiasa, S.; Iwamoto, S.; Endo, T.; Edashige, Y. Isolation of cellulose nanofibrils from mandarin (Citrus unshiu) peel waste. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Du, X.; Yin, Z.; Xu, S.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanofibrils from coconut coir fibers and their reinforcements in biodegradable composite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafid, H.S.; Omar, F.N.; Bahrin, E.K.; Wakisaka, M. Extraction and surface modification of cellulose fibers and its reinforcement in starch-based film for packaging composites. Bioresour. Bioprocess 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Green and sustainable pretreatment methods for cellulose extraction from lignocellulosic biomass and its applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyerere, G.; Kyokusiima, S.; Nabaterega, R.; Tumusiime, G.; Kavuma, C. The synergy of maize straw cellulose and sugarcane bagasse fibre on the characteristics of bioplastic packaging film. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 28, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, A.; Hedenqvist, M.; Brolin, A.; Wågberg, L.; Malmström, E. Highly Ductile Cellulose-Rich Papers Obtained by Ultrasonication Assisted Incorporation of Low Molecular Weight Plasticizers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 8836–8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Sample preparation flowchart. UJR, untreated juice extraction residue; U-DW, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water; U-OX, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution; PJR, purified cellulose from UJR; P-DW, purified cellulose from U-DW; P-OX, purified cellulose from U-OX; OX, Oxalate.

Figure 1.

Sample preparation flowchart. UJR, untreated juice extraction residue; U-DW, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water; U-OX, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution; PJR, purified cellulose from UJR; P-DW, purified cellulose from U-DW; P-OX, purified cellulose from U-OX; OX, Oxalate.

Figure 2.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra (a) and LOI, Carbonyl index, and Lignin index (b) of the samples calculated from the FT-IR data. LOI, the lateral order index.

Figure 2.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra (a) and LOI, Carbonyl index, and Lignin index (b) of the samples calculated from the FT-IR data. LOI, the lateral order index.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscope images of the samples: (a) appearance of films upon visual inspection after sonication (b) after sonication followed by ethanol replacement and air-drying. UJR, untreated juice extraction residue; U-DW, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water; U-OX, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution; PJR, purified cellulose from UJR; P-DW, purified cellulose from U-DW; P-OX, purified cellulose from U-OX.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscope images of the samples: (a) appearance of films upon visual inspection after sonication (b) after sonication followed by ethanol replacement and air-drying. UJR, untreated juice extraction residue; U-DW, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water; U-OX, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution; PJR, purified cellulose from UJR; P-DW, purified cellulose from U-DW; P-OX, purified cellulose from U-OX.

Figure 4.

Sample appearance (a) after sonication and (b) texture profiles including (b) maximum (blue), adhesive (red), gumminess forces (green), and (c) adhesion. UJR, untreated juice extraction residue; U-DW, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water; U-OX, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution; PJR, purified cellulose from UJR; P-DW, purified cellulose from U-DW; P-OX, purified cellulose from U-OX.

Figure 4.

Sample appearance (a) after sonication and (b) texture profiles including (b) maximum (blue), adhesive (red), gumminess forces (green), and (c) adhesion. UJR, untreated juice extraction residue; U-DW, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in deionized water; U-OX, juice extraction residue after pectin extraction in sodium oxalate solution; PJR, purified cellulose from UJR; P-DW, purified cellulose from U-DW; P-OX, purified cellulose from U-OX.

Figure 5.

Removal (blue) and adsorbing capacities (light blue) of samples to (a) MB and (b) CR (50 mg/L of MB and CR were used for the adhering test, and 1 g/L was used for adsorbing test). MB, methylene blue; CR, Congo red.

Figure 5.

Removal (blue) and adsorbing capacities (light blue) of samples to (a) MB and (b) CR (50 mg/L of MB and CR were used for the adhering test, and 1 g/L was used for adsorbing test). MB, methylene blue; CR, Congo red.

Table 1.

The chemical composition of UJR, U-DW and U-OX.

Table 1.

The chemical composition of UJR, U-DW and U-OX.

| Materials | Cellulose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) |

|---|

| UJR | | | |

| U-DW | | | |

| U-OX | | | |

Table 2.

Cellulose crystallinity index (CrI) of each sample before and after sonication.

Table 2.

Cellulose crystallinity index (CrI) of each sample before and after sonication.

| Samples | CrI (%) |

|---|

| Before | After |

|---|

| Cellulose | 80.2 | 74.7 |

| UJR | 44.0 | 51.3 |

| U-DW | 45.0 | 64.0 |

| U-OX | 60.5 | 55.3 |

| PJR | 61.1 | 76.9 |

| P-DW | 66.3 | 71.1 |

| P-OX | 63.4 | 70.0 |

Table 3.

Zeta potential, average particle size, and polydispersity index (PDI) of the samples after sonication.

Table 3.

Zeta potential, average particle size, and polydispersity index (PDI) of the samples after sonication.

| | Zeta Potential (mV) | Average Particle Size (nm) | PDI |

|---|

| UJR | −16.86 ± 0.95 | 252.34 ± 37.07 | 0.34 ± 0.02 |

| U-DW | −14.64 ± 0.16 | 259.02 ± 35.04 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| U-OX | −16.23 ± 0.28 | 180.19 ± 3.41 | 0.27 ± 0.01 |

| PJR | −29.49 ± 0.54 | 173.35 ± 7.66 | 0.39 ± 0.01 |

| P-DW | −20.57 ± 0.64 | 85.35 ± 36.61 | 0.37 ± 0.02 |

| P-OX | −16.94 ± 0.57 | 221.96 ± 15.13 | 0.36 ± 0.02 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).