1. Introduction

Hydrogen-powered internal combustion engines (H

2ICEs) represent one of the most promising future technologies to achieve carbon-neutral transport. They combine the mechanism of traditional combustion engines, offering low carbon-based emissions and high thermal efficiency [

1,

2]. Their ability to utilize existing manufacturing infrastructure and mechanical platforms enables a cost-effective and rapid pathway toward low-carbon propulsion, particularly in heavy-duty and long-haul applications where full electrification remains challenging.

Two intrinsic properties of hydrogen make it especially suitable for clean combustion applications:

Carbon absence in the molecule eliminates direct CO2, CO, and hydrocarbon emissions.

Extremely wide flammability range (4–76 vol%) and high flame propagation velocity, allowing stable combustion even at highly lean mixtures.

Experimental investigations have shown that hydrogen-powered spark-ignition engines operating under ultra-lean conditions (λ ≥ 2) can achieve extremely low NO

x emissions, in some cases below 10 ppm or approaching the detection limit [

3,

4]. Conversely, when the equivalence ratio approaches stoichiometric conditions, NO

x formation increases rapidly and can exceed several hundred ppm depending on the load and in-cylinder temperature. This behavior highlights the sensitivity of NO

x production to mixture richness and confirms that lean operation remains a key strategy for reducing emissions in hydrogen engines.

Nevertheless, as load and equivalence ratio increase, the advantageous lean-burn characteristics become constrained. Very low ignition energy (approximately 0.02 mJ) and high diffusivity raise the tendency to pre-ignition and knock at high charge temperatures. Stoichiometric or rich operation, while enhancing power density, increases NOx formation and may trigger abnormal combustion phenomena. Thus, the development of advanced hydrogen combustion control strategies that combine direct injection (DI), turbocharging, cooled EGR, and numerical optimization has become a main focus of present research.

From a systemic viewpoint, H

2ICEs serve as a bridge technology toward future hydrogen ecosystems, complementing fuel-cell systems [

5]. Their compatibility with existing engine design presents an economically feasible medium-term decarbonization solution [

6].

Despite the growing interest in hydrogen propulsion, most of the current research efforts have focused either on combustion behavior or emission characteristics under different operating conditions, without sufficiently addressing the transient process of hydrogen–air mixing during the intake phase. For example, previous studies have investigated the optimization of hydrogen injection timing, ignition control, and abnormal combustion phenomena [

7,

8,

9], as well as the potential for improving the performance of direct injection and mixture formation strategies. However, these works usually analyze the mixture state near ignition or during combustion and rarely evaluate the spatial evolution of hydrogen concentration and in-cylinder flow structure at an early stage. This neglects a key aspect of DI-H

2ICE operation, as the mixture stratification created during the intake stroke decisively affects the local equivalence ratios, ignition stability, and subsequent NO

x formation.

Therefore, a detailed numerical analysis of the interaction of hydrogen flow with piston-induced swirl, injector targeting, and combustion chamber geometry as a function of crankshaft angle is still lacking in the literature. Addressing this research gap is essential for improving mixture homogeneity, reducing cyclic variability, and developing predictive tools that support the design of future high-efficiency hydrogen engines.

2. Materials and Methods

The dominant exhaust species in hydrogen combustion are nitrogen oxides (NOx), originating from the thermal oxidation of atmospheric nitrogen. The absence of carbon means that traditional pollutants (CO, CO2, and unburned hydrocarbons) are practically eliminated, except for minor contributions from lubricating oil oxidation.

Hydrogen’s lean-burn capability is a powerful tool for emission control. Experimental studies have shown that when operated at λ > 2, NO

x concentrations can drop below 10 ppm, approaching natural atmospheric background levels [

10]. However, the same properties that enable efficient combustion (high laminar flame speed and low ignition energy) also complicate control, leading to potential pre-ignition and knock under high-pressure or high-temperature conditions.

Hydrogen’s small molecular size also presents sealing and mixture-homogeneity challenges. Leakage through injector seats, valves, and piston rings can create safety risks and efficiency losses. Thus, precise fuel metering, injection control, and crankcase ventilation systems are essential.

In modern H2ICEs, apart from NOx, minor quantities of ammonia (NH3) and nitrous oxide (N2O) can form under specific operating conditions, especially during rich operation or in engines using aftertreatment catalysts. Anticipated emission regulations, such as EURO 7, strictly limit these emissions.

Hydrogen-specific aftertreatment solutions have been proposed, notably hydrogen-assisted selective catalytic reduction (H

2-SCR), in which hydrogen serves directly as the reducing agent for NO

x removal. Such systems achieve more than 90% conversion efficiency at only 150 °C, offering major advantages over urea-based SCR, which requires higher activation temperatures [

11].

2.1. Combustion System Adaptations for Hydrogen Operation

Adapting a conventional internal combustion engine to operate on hydrogen involves substantial mechanical, thermal, and control modifications, aimed at preventing pre-ignition, maintaining durability, and optimizing mixture formation.

Key adaptations include:

Combustion-chamber geometry: minimizing crevice volume and optimizing squish to suppress flame backflow;

Valve and seat materials: employing hydrogen-resistant alloys to prevent embrittlement and premature wear;

Enhanced cooling systems: multi-valve layouts, sodium-filled exhaust valves, and improved coolant routing to moderate local hot spots;

Ignition control: use of low-heat-range spark plugs and adaptive ignition phasing to avoid surface ignition;

Injector and seal materials: selection of coatings compatible with hydrogen’s low lubricity;

Safety ventilation: crankcase relief and hydrogen detection systems to prevent accumulation.

Hydrogen embrittlement is particularly critical for ferrous alloys, which means diffusion of atomic hydrogen into metal lattices reduces ductility and fatigue strength. Therefore, nickel-based alloys, austenitic stainless steels, or surface coatings (TiN, DLC) are typically employed to ensure long-term durability.

Combustion chamber cooling can be reinforced through variable valve timing (VVT) and residual-gas control, while ignition or injection phasing can be advanced or retarded to manage knock and reduce peak temperatures [

12,

13,

14].

2.2. Hydrogen Engine Concepts and Operation Modes

2.2.1. Spark-Ignition Hydrogen Engines (SI-H2ICE)

Hydrogen’s wide flammability limit (λ ≈ 0.4–10) and rapid flame propagation make it inherently compatible with spark-ignition combustion. Three main fueling approaches exist:

Port Fuel Injection (PFI): hydrogen is premixed with intake air in the manifold. The system is simple and cost-effective but limited by reduced volumetric efficiency and high backfire risk.

Direct Injection (DI): hydrogen is injected directly into the cylinder after intake-valve closure. This configuration eliminates backfire, enhances air utilization, and increases power density.

Cryogenic Direct Injection (L-H2 DI): uses liquid hydrogen, leveraging strong charge-cooling effects that reduce NOx and enable higher loads.

Under lean-burn operation, SI hydrogen engines can achieve brake thermal efficiency (BTE) above 40% and keep NO

x under 10 ppm. However, stoichiometric operation at higher loads elevates NO

x and pre-ignition risk, requiring countermeasures such as EGR or water injection [

15,

16].

2.2.2. Compression-Ignition and Dual-Fuel Hydrogen Engines (CI-H2ICE)

Pure hydrogen cannot autoignite due to its high auto-ignition temperature (approximately 585 °C). Thus, CI operation relies on pilot injection of diesel or another ignition fuel, forming dual-fuel systems where hydrogen supplies 70–90% of the energy.

Hydrogen addition improves combustion efficiency, reduces CO and HC emissions to near zero, and enhances charge reactivity. Nevertheless, high combustion temperatures retain NO

x formation. EGR, water injection, and variable compression ratio strategies are therefore applied to limit NO

x, although with modest trade-offs in volumetric efficiency (approximately 10–15% reduction) [

17,

18,

19].

2.3. Boosted and Direct-Injection Hydrogen Engines

2.3.1. Pressure-Boosted Operation

Boosting expands hydrogen engine output substantially but narrows the safe operating window due to the increased risk of pre-ignition and NO

x formation. Empirical data show that as intake pressure increases from 1 bar to 2.6 bar, the limited preignition equivalence ratio declines from 1.0 to 0.5 [

20].

Thermal management techniques, including intercooling, water injection, and cooled exhaust valves, extend the knock region. Turbocharged hydrogen engines can operate around λ = 0.4–0.6, achieving BTE roughly 39%, BMEP around 11 bar, and NOx under 100 ppm even without aftertreatment. Adaptive operation that transitions between lean, stoichiometric, and boosted regimes enables optimized power-emission balance across the load range.

2.3.2. Direct-Injection Strategies

Direct injection (DI) remains the basis of modern hydrogen engine development. Introducing hydrogen directly into the combustion chamber, typically after intake valve closure, minimizes displacement of intake air and prevents backfire. However, it requires precise synchronization and control of injection timing, pressure, and spray characteristics.

Higher injection pressures increase jet penetration and turbulence intensity, leading to faster and more uniform mixing,

Delayed injection timing increases stratification—lowering NOx under high-load operation but potentially reducing efficiency under lean conditions,

Nozzle geometry strongly influences mixture distribution: larger diameters enhance jet momentum but risk local rich pockets, and smaller diameters improve homogeneity at the cost of higher pressure drop.

Dual-injection concepts, combining PFI for part-load operation with DI for high-load demand, have achieved up to 70% higher power and 15–30% efficiency improvement compared with single-mode fueling [

24].

2.4. Hydrogen Flow and Mixing During Intake and Early Compression

The in-cylinder flow and fuel-air mixing behavior during the intake and early compression strokes radically determine combustion efficiency, stability, and emission outcomes. The intake system generates complex swirl structures, which evolve during piston descent and strongly interact with the hydrogen jet.

In PFI configurations, hydrogen pre-mixes with intake air upstream of the valve. While this can yield homogeneous mixtures, early injection may lead to stratification near the valve, and backfire risk increases due to hydrogen accumulation in the manifold [

22]. Late-phase manifold injection enhances mixture homogeneity but can slightly reduce volumetric efficiency.

In DI systems, hydrogen is typically injected between 300 and 360° CA, corresponding to late intake or early compression phases. In the present simulation, hydrogen is injected from −130° to −118° of crankshaft angle Before Top Dead Center (BTDC). Although many DI studies report a nominal injection interval of 300–360° CA, this convention corresponds to the same physical phase when applied to the current crankshaft angle coordinate system. The apparent numerical difference arises solely from the adopted angular definition and the valve timing configuration of the analyzed engine. The available mixing duration (4–20 ms) demands supersonic jet velocities (Mach 1–1.2). The hydrogen jet entrains surrounding air, generating strong shear layers and turbulence that promote dispersion. Nevertheless, due to hydrogen’s low density, perfect homogeneity is rarely achieved before ignition, while stratified zones persist, affecting flame propagation and NO

x formation [

23,

24].

Therefore, the objective of this work is to test the DI system of hydrogen combined with a special design piston crown. This paper gives an idea for combustion chamber design with further development and optimalization of injector position and piston crown.

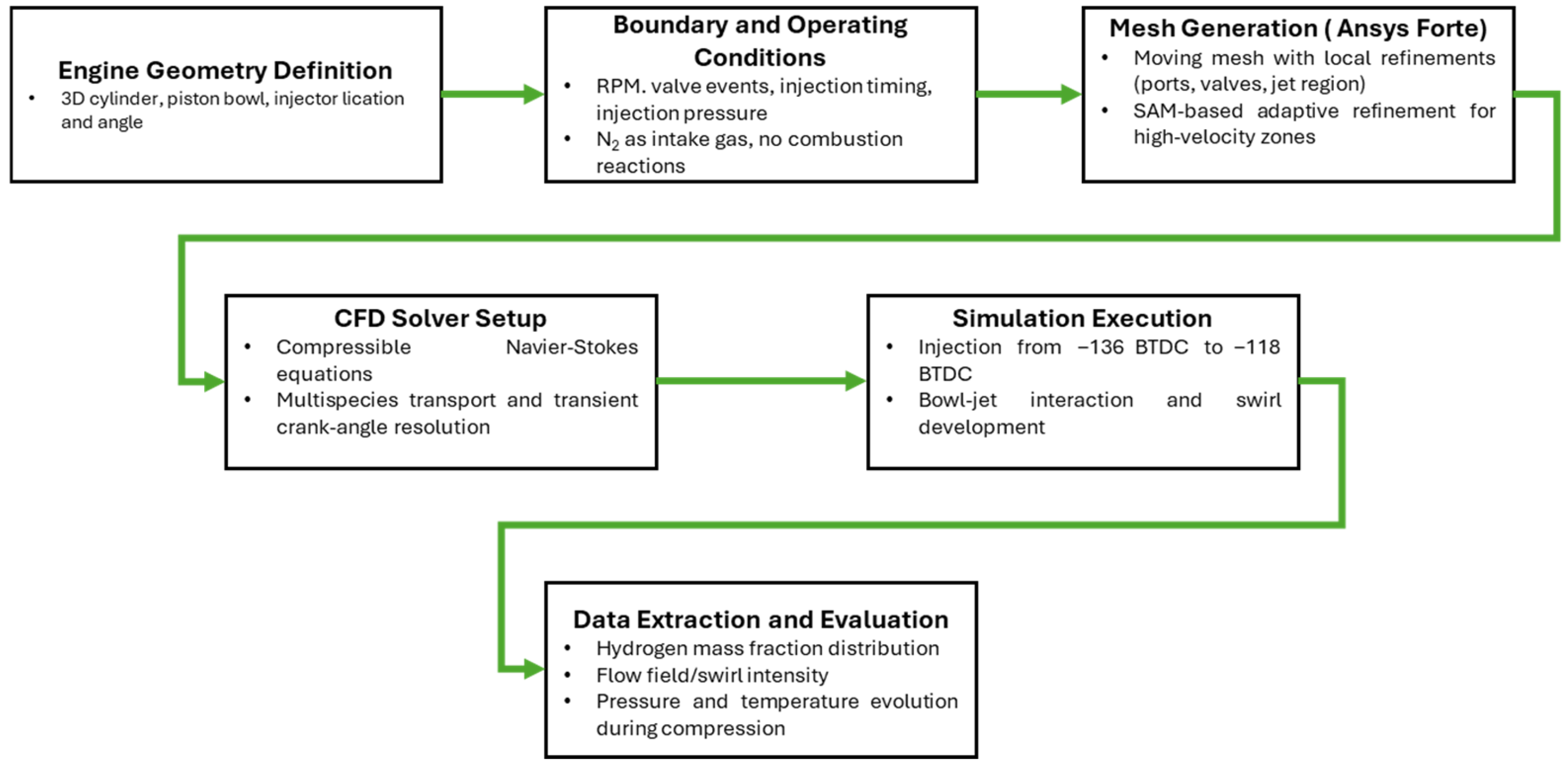

2.5. Simulation Workflow and Numerical Model

To clarify the methodological structure (

Figure 1) of this work and to meet the requirements of numerical repeatability, this section provides a detailed description of the simulation procedure, boundary conditions and evaluation criteria used for the CFD analysis. The purpose of the numerical investigation is to quantify the mixing behavior of hydrogen in the cylinder before ignition and to identify how the injector position, injection angle and combustion chamber geometry affect the mixture uniformity and the flow evolution in the cylinder.

This study was performed using ANSYS Forte 2022 R2, a CFD platform designed for internal combustion engine simulations. The solver applies compressible Navier–Stokes equations with multimodal transport and a moving mesh algorithm synchronized with the crankshaft angle progression. No combustion reactions were modeled at this stage; therefore, nitrogen (N2) was used as the input medium to isolate the influence of flow structures and fuel flow dynamics without thermal and chemical feedback of exothermic reactions.

The computational domain represents a four-cylinder hydrogen engine equipped with a bowl-shaped piston crown and a side-mounted injector. Hydrogen is injected at a pressure of 100 bar during the intake stroke, starting at a crankshaft angle of −129° before top dead center (BTDC) and ending at −59° BTDC. The injector is oriented at an angle of 73° with respect to the horizontal axis and located 27.5 mm from the center of the combustion chamber, which allows for direct interaction between the hydrogen jet and the vortex generated by the intake flow and the piston motion.

The simulation covers the crankshaft angle period from TDC after the exhaust stroke to the early compression phase after the hydrogen injection is complete. This range captures the formation and transport of stratified hydrogen zones, allowing for an assessment of the mixing intensity before ignition. The engine speed was set to 1500 rpm, which corresponds to a time resolution sufficient to analyze the short hydrogen–air mixing window characteristic of DI systems.

The computational mesh was generated automatically in ANSYS Forte 2022 R2 with local refinement applied in areas of expected high velocity gradients, specifically, the intake port, valve curtain area, and hydrogen jet path. Solution Adaptive Mesh (SAM) refinement was enabled based on flow velocity to improve numerical accuracy when hydrogen exits the injector at high velocity, thereby preventing excessive jet diffusion and preserving local mass fraction gradients.

Four quantities were extracted from the simulation results for each crankshaft rotation step:

Hydrogen mass fraction distribution, indicating mixture stratification and flow front advancement;

Velocity field and flow topology, capturing vortex–flow interaction and recirculation structures;

Pressure evolution, confirming compression trends and ensuring numerical stability;

Temperature evolution, monitored solely as a consequence of gas compression, not combustion.

These variables provide a basis for evaluating how piston cup geometry and hydrogen flow direction affect charge distribution, mixture preparation, and pre-spark timing conditions.

It should be noted that the ammonia (NH3) and nitrous oxide (N2O) formation pathways were not included in this simulation. Since the chemical reactions were deactivated and nitrogen (N2) was used instead of real air, this numerical study only describes the mixture preparation and does not consider the formation of reactive species or emission chemistry. These effects will be addressed in future work after the implementation of combustion and realistic intake air composition.

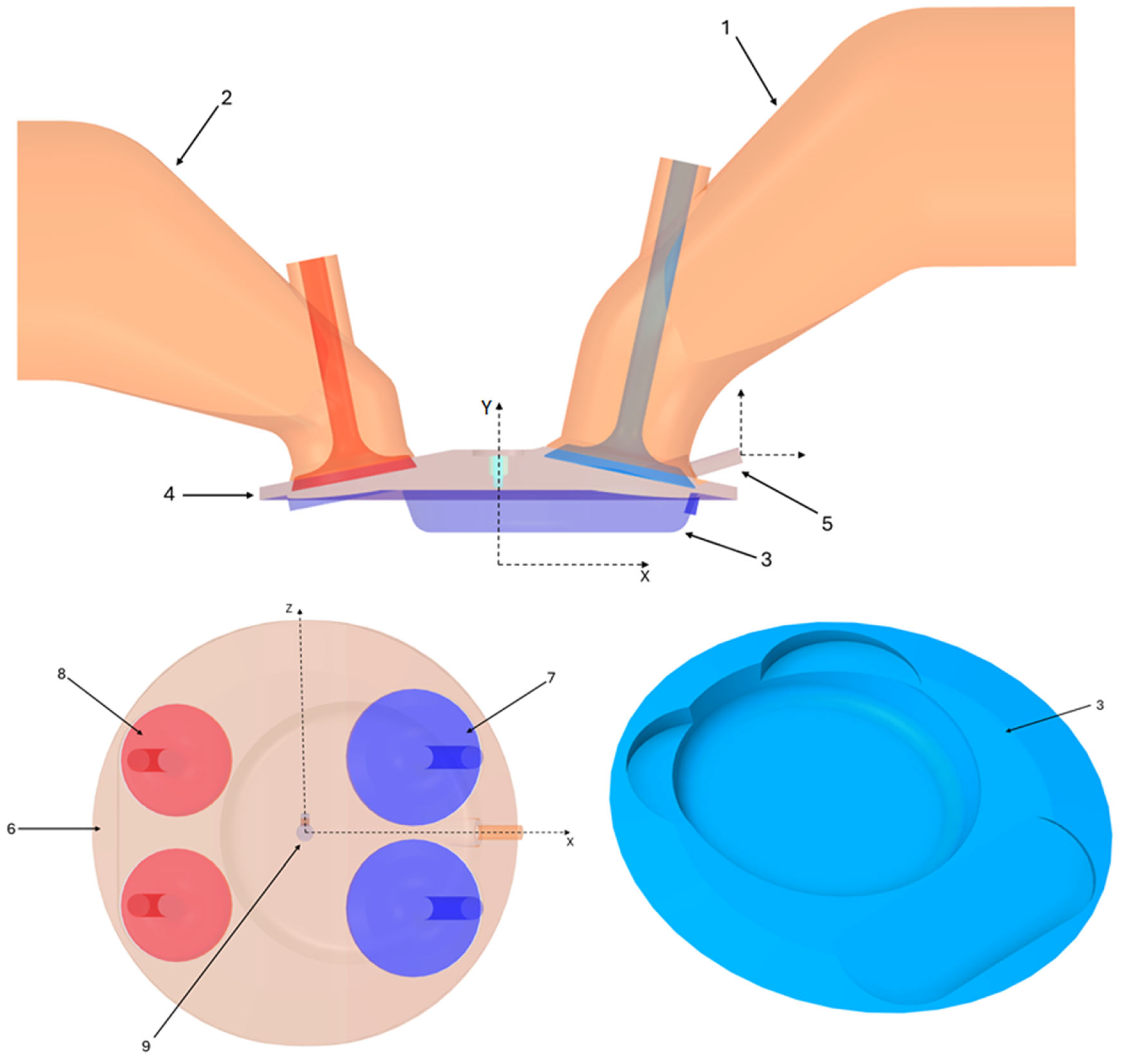

2.6. Three-Dimensional Engine Model

Designed 3D combustion chamber model (

Figure 2) represents the piston crown construction as well as the position of hydrogen jet located on the side of the cylinder head at angle of 73° relative to the vertical

Y axis and 27.5 mm from the combustion chamber center, i.e., from the

Y axis.

The coordinate system used in this study is defined such that the Y axis coincides with the cylinder axis and follows the piston stroke direction, while the X axis lies horizontally in the plane of the cylinder head. The injector is located 27.5 mm laterally from the center of the combustion chamber, measured along the X axis, and is oriented at an angle of 73° with respect to this horizontal direction, allowing direct targeting of the jet onto the piston bowl.

Further engine specifications are represented in

Table 1.

Mesh Modeling

The calculation of hydrogen injection into the designed combustion engine was established in Ansys Forte which generates a quality mesh of the whole domain. Forte mesh utilities offer area mesh refinement used to increase the quality and effectiveness of the calculation. The model was meshed by auto-meshing of Ansys Forte with piston, valves, walls, and intake and exhaust ports mesh refinement (

Table 2). Solution Adaptive Mesh was also interpreted for velocity to accurately refine the mesh when gas enters the combustion chamber at high speed.

The final computational mesh consisted of approximately 2.8 × 105 cells at the beginning of the intake stroke and up to 5.2 × 105 cells during hydrogen injection due to the activation of Solution Adaptive Mesh (SAM) refinement in regions with high velocity gradients. Although the global mesh size was set to 2 mm, the mesh was locally refined to 1/16 of the global size (≈0.125 mm) along the hydrogen jet axis and in the shear layer interaction zone. This refinement provided 8–12 cells across the effective jet diameter, allowing numerical resolution of the near-field jet structure, penetration behavior, and entrainment process.

The configuration of the moving mesh causes the number of cells to change with the crankshaft angle; nevertheless, the mesh quality remained within acceptable limits for transient CFD simulations in the cylinder, with diagnostic checks confirming compliance with the recommended skewness and orthogonality levels reported in similar ICE studies. The mesh density and refinement strategy used is therefore considered sufficient to resolve the dominant physical phenomena governing hydrogen jet penetration, mixing and vortex interaction.

3. Results and Discussion

The subsequent section will present a CFD-based simulation of the intake and mixing process in Ansys Forte, analyzing hydrogen jet dynamics and in-cylinder turbulence characteristics at engine rotation speed 1500 rpm.

The cycle is set from TDC before the intake cycle until the early stage of compression when the hydrogen injection is finished. Hydrogen is injected into the combustion chamber at 100 bars, increasing mixing ability, combined with a bowl-style piston crown to increase swirl and tumble motion inside the cylinder. The simulation assumes nitrogen (N2) as the intake gas in order to avoid chemical reactions and isolate the fluid-dynamic behavior of the hydrogen stream (jet) during this design phase. The choice of nitrogen instead of real air was deliberately made to eliminate chemical reactions and heat release phenomena that would otherwise alter the flow fields and temperatures during hydrogen injection. This simplification isolates the aerodynamic behavior of the hydrogen jet and allows for a controlled study of stratification, wall interaction, and vortex development without the influence of oxygen-driven combustion chemistry. However, this approach introduces some limitations: the absence of oxygen changes the thermophysical properties of the mixture, in particular, density, specific heat, and speed of sound, which can affect jet penetration and turbulence decay rates. Therefore, although the presented results accurately reflect the kinematic and geometric effects of direct hydrogen injection, they cannot be used to directly derive emission formation, ignition delay, or final equivalence ratio values. These aspects will be addressed in future work after implementing realistic air composition and combustion models.

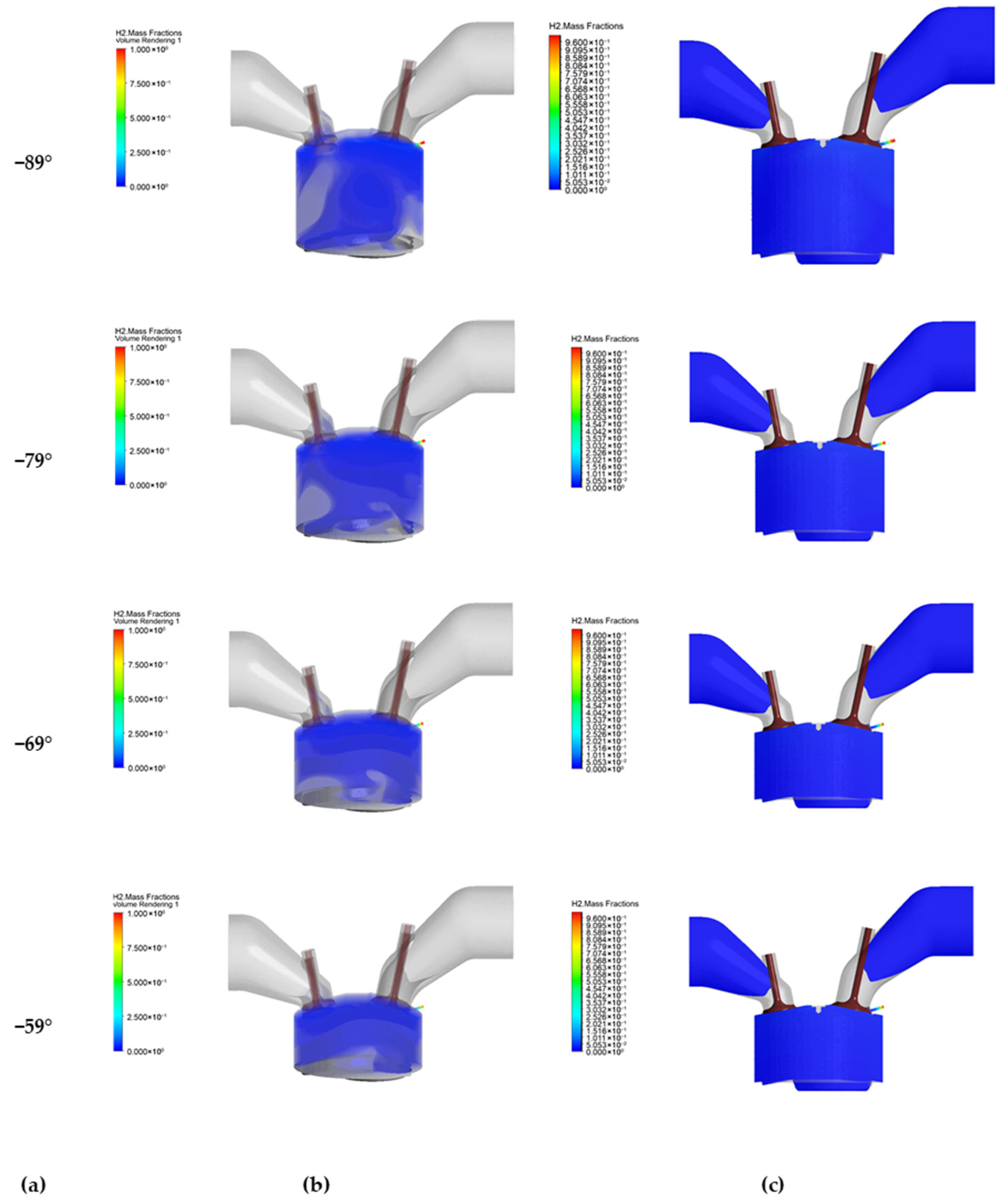

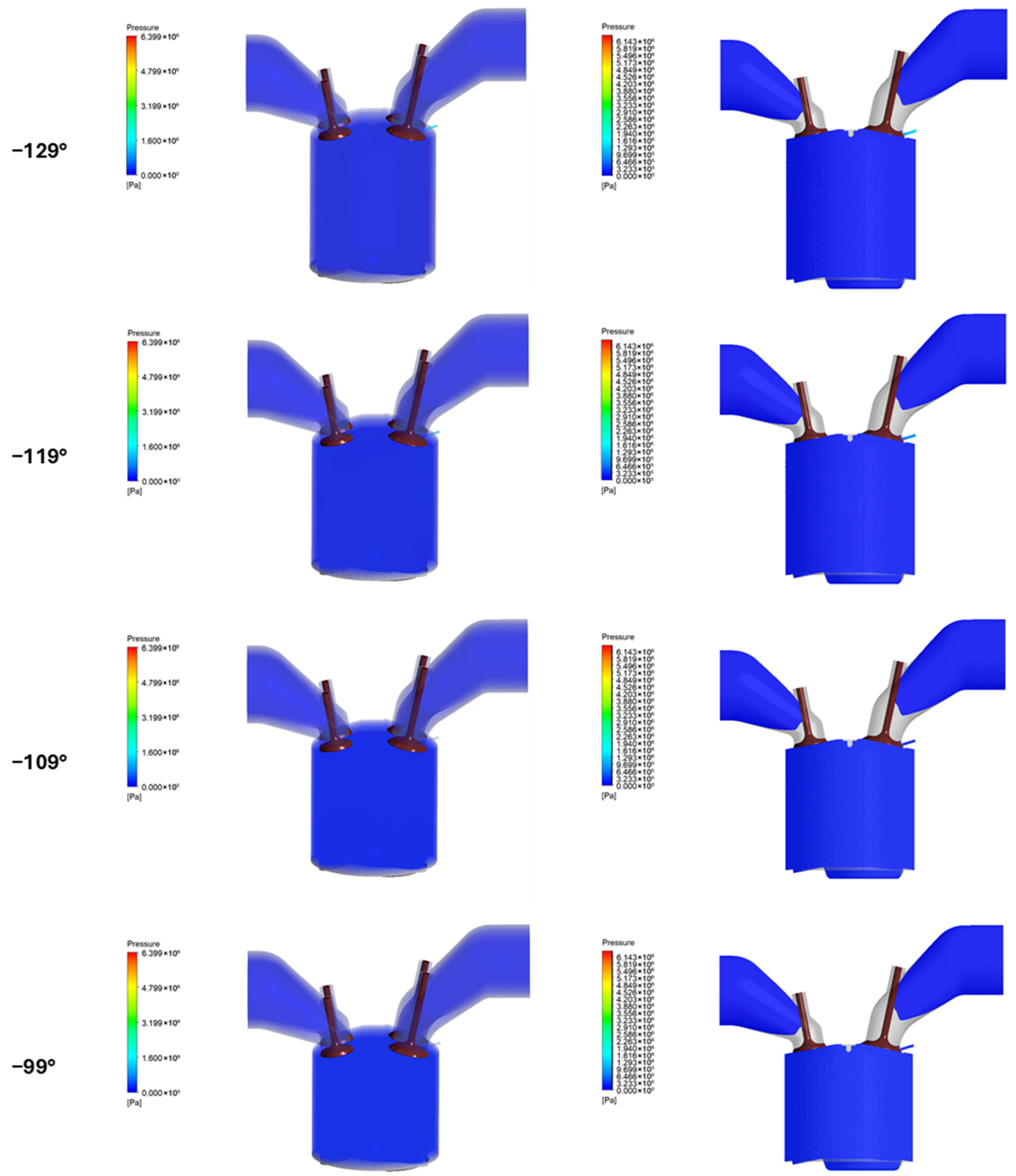

The flow in the cylinder during the late intake and early compression reveals a complex interaction between injected hydrogen, the chamber geometry, and the induced air motion. The combustion chamber geometry defined by a four-valve pent-roof cylinder head and bowl-shaped piston promotes a combination of swirl and tumble flow structures that highly influence the hydrogen distribution and mixture formation (

Figure 3).

At −129° BTDC, the injected hydrogen under near-atmospheric pressure penetrated rapidly along its axis at a 73° incline relative to the horizontal plane. The large pressure gradient between the injector nozzle and the cylinder volume causes the hydrogen to exit the nozzle at sonic velocity, forming a high-momentum jet core. The jet entrains surrounding nitrogen, generating shear layers at the interface. As a result, high turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) zones are created, enhancing early entrainment but with limited coverage near the injector side.

At −119° BTDC, the hydrogen stream reaches the cylinder wall and falls at an oblique angle, which forms a stagnation region followed by a radial wall jet. The momentum dissipation produces two distinct counter-rotating vortices along the cylinder wall, which pull hydrogen down into the piston crown, bowl. A secondary circulation begins to form between the piston surface and the cylinder wall, which redistributes the hydrogen toward the center of the chamber.

At −109 BTDC, the piston starts to move upward to the TDC. The reflected stream from the wall collides with the flow generated by the upward-moving piston, producing a strong tumble vortex that dominates the central region. Hydrogen concentration increases in the piston bowl due to this convergence, forming a stratified pocket that gradually mixes with the surrounding air. The velocity vectors indicate swirl-tumble coupling, which is beneficial for mixing, but formation of nonuniform local equivalence ratios may be generated if the diffusion is not balanced.

By −99° BTDC, the mixture becomes more symmetrical as the turbulence redistributes the hydrogen radially and axially. As the stream core weakens, the hydrogen diffuses upwards to the spark plug region. Rich near cylinder wall zones start to dilute as entrained air increases local homogeneity.

Between −89° and −69° BTDC, turbulence dominates the flow. The kinetic energy peaks near the center of the bowl and disintegrates toward the walls. The hydrogen concentration gradient flattens as the vortex weakens. The uniformity index of the hydrogen mass fraction approaches unity, which indicates that the mixing efficiency reached its maximum before compression takes place.

At −59° BTDC, the piston compresses the entire mixture. The flow field is characterized by residual, low-intensity, directionally non-dominant vortices, which confirms that the motion has transformed into the fine turbulent structures. The evenly distributed hydrogen forms an almost homogenous mixture that is ready for the ignition phase.

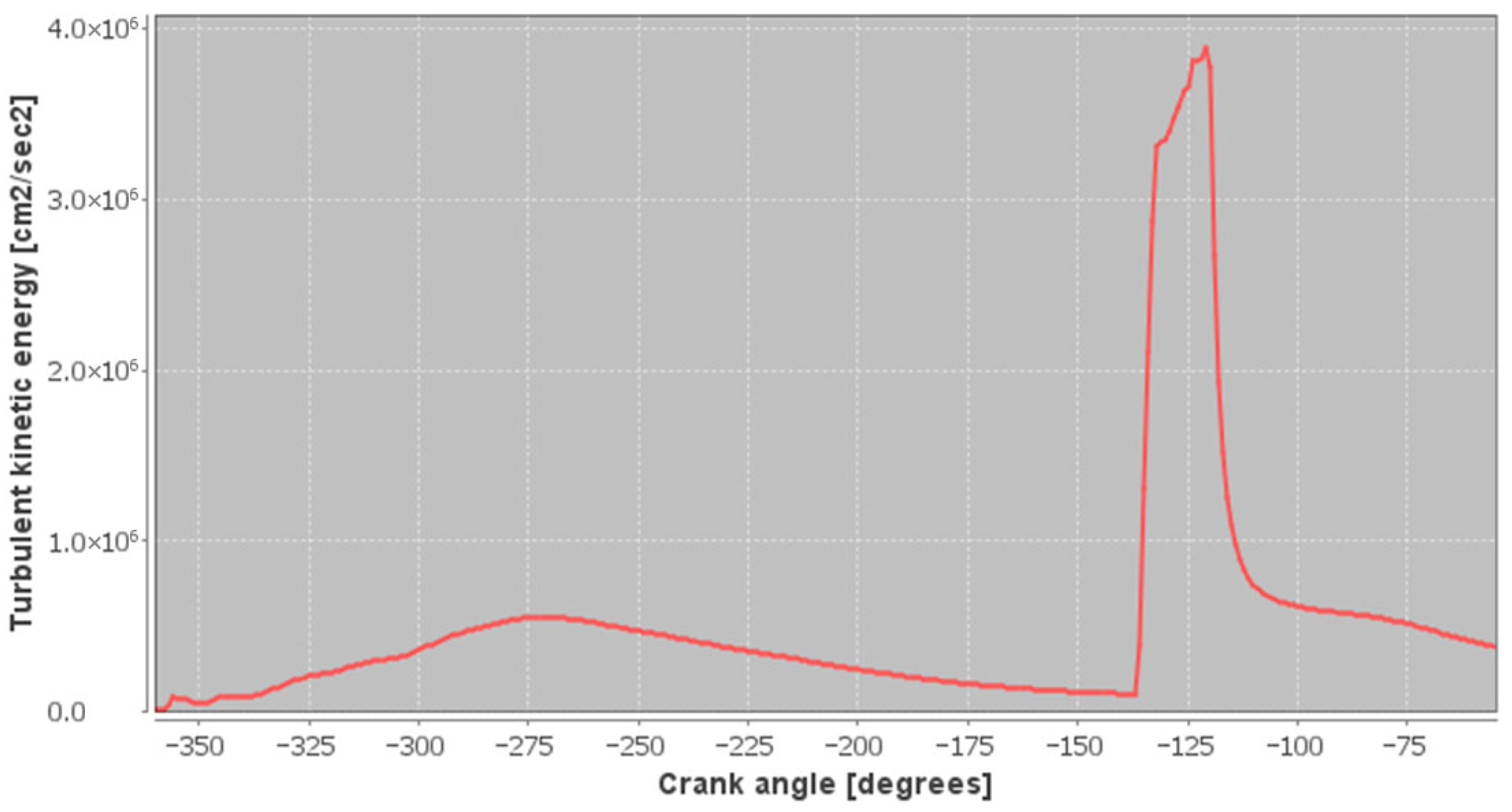

To support these observations, the development of turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) during the intake and early compression strokes was evaluated.

Figure 4 shows the gradual breakdown of large-scale motion into fine-scale turbulence as the hydrogen stream dissipates in the chamber.

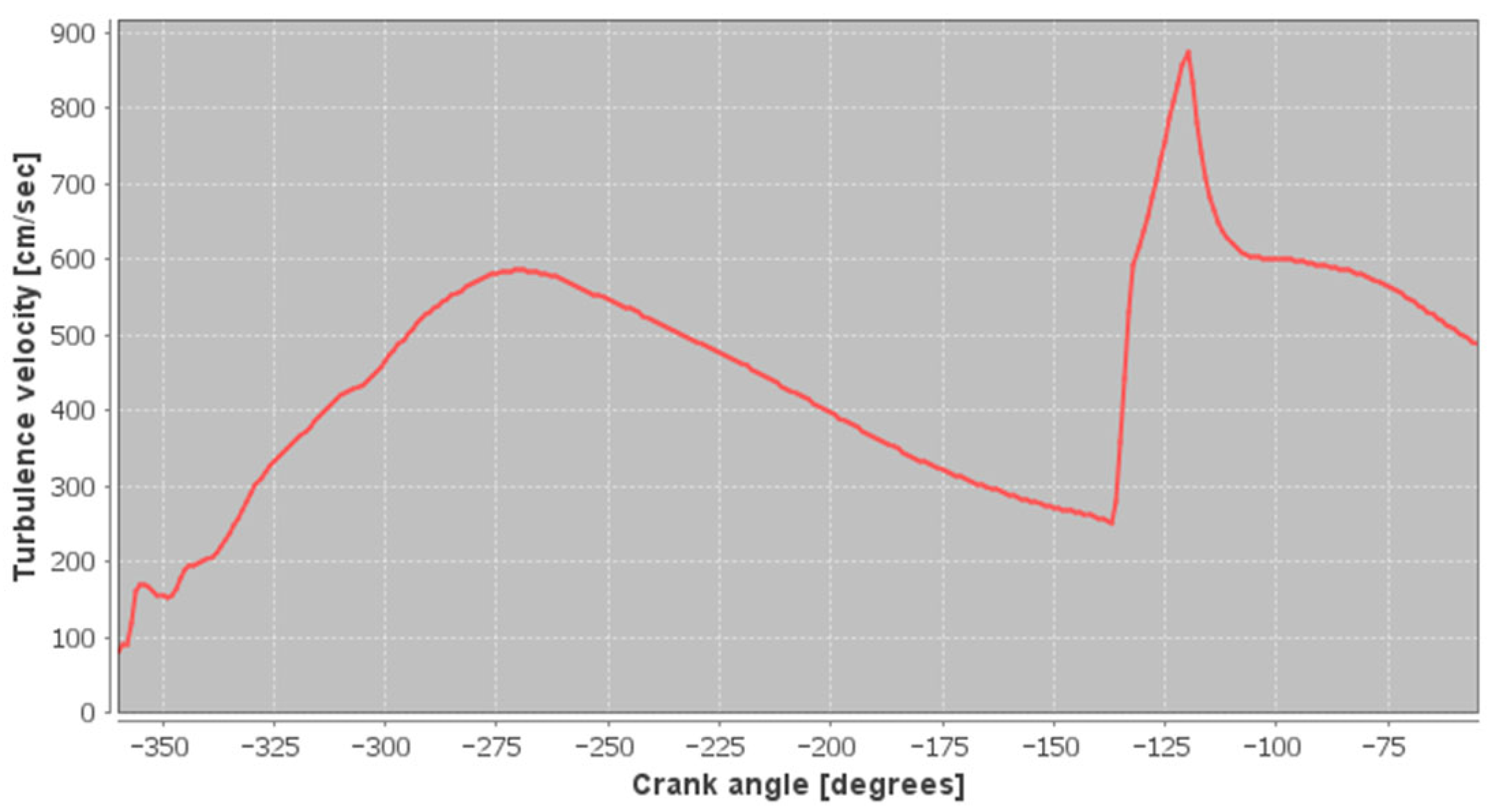

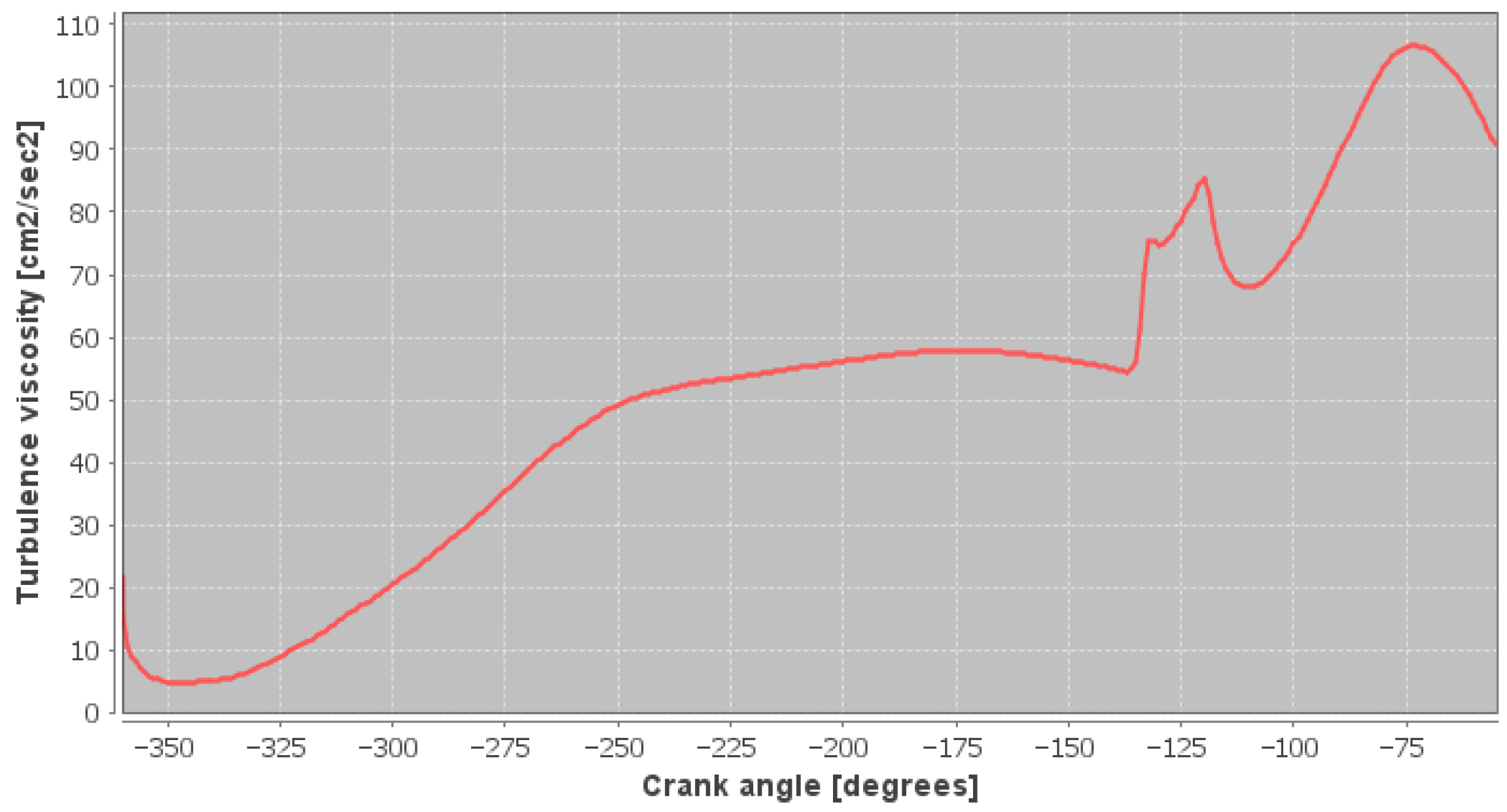

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 plots quantify the time evolution of the turbulent field during the intake and early compression strokes. The turbulent kinetic energy peaks at −128° BTDC, which coincides with the end of injection, where the flow-induced shear layers generate strong vortex motion. The turbulence velocity reaches approximately 850 cm/s at the same crankshaft angle, indicating intense near-wall interactions and promoting hydrogen dispersion. The corresponding turbulent viscosity also shows a sharp increase after injection, confirming the increased mixing intensity. These quantitative results support the qualitative structures observed in the flow field visualizations.

Figure 7 shows the development of the swirl ratio as a function of the crankshaft angle. The swirl intensity increases during the intake stroke due to the valve-controlled asymmetry and reaches a value of around 0.025 at −230° BTDC. After injection, a secondary swirl peak appears at around −125° BTDC, which is caused by the lateral momentum of the hydrogen jet, which transfers angular momentum to the bulk charge. The subsequent decrease towards TDC indicates dissipation during compression. These trends quantitatively confirm the swirl-assisted mixing mechanisms described above.

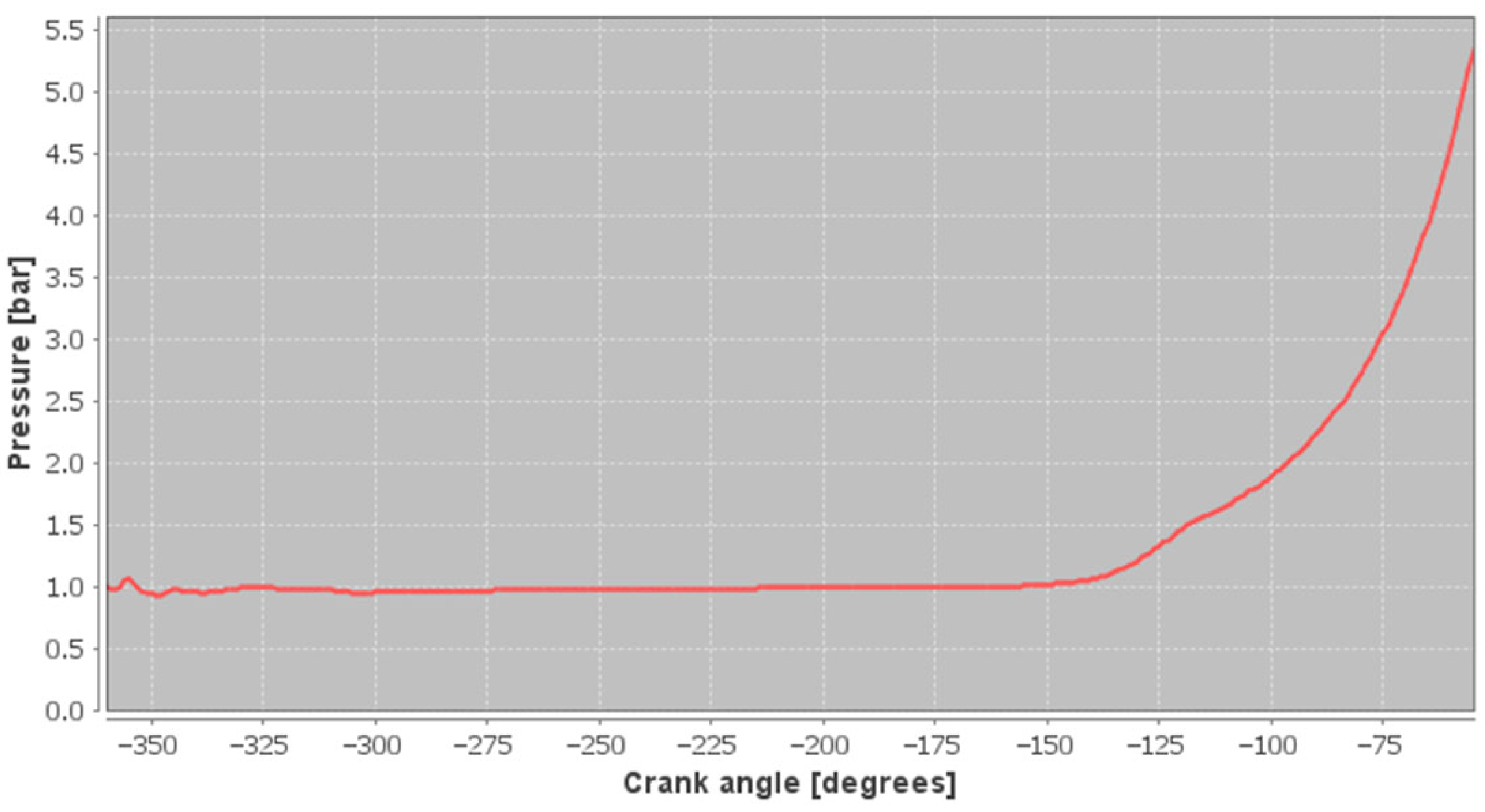

The pressure inside the combustion chamber evolves in parallel with the flow development, which reflects both the aerodynamic and thermodynamic changes (

Figure 8).

At −129° BTCD, the cylinder pressure is approximately equal to the intake manifold pressure (around 1 bar). Except for the region near the injection region, the pressure contours are uniform, caused by the hydrogen stream momentum. These micro-gradients result from local stagnation zones formed at the stream region, have very small to no global impact.

At −119° BTDC, the average cylinder pressure remains nearly constant, but local Δp within the stagnation zone can reach several percent above the mean.

By −109° BTDC, the upward piston motion begins to dominate the flow. The gas trapped inside the cylinder starts to compress, which increases the overall chamber pressure. The bowl region shows slightly higher values due to convergence and the rebound of the hydrogen stream from the piston crown.

At −99° BTDC, pressure continues to rise as the piston moves toward TDC. The swirl and the compression motion promote smooth redistribution of gas momentum and pressure.

Between −89° and −69° BTDC, the compression effect becomes more dominant. The pressure rises uniformly with a monotonic increase. The flow structure stabilizes, and the isentropic compression trend begins to emerge.

At −59° BTDC, the entire charge shows a consistent pressure rise, with uniform contours across the symmetry plane. At this point, the mixture is prepared for full compression and further ignition.

Figure 9 shows the time evolution of the cylinder pressure as a function of the crankshaft angle. The pressure increases monotonically from approximately 1.0 bar at −150° BTDC to approximately 5.3 bar at −59° BTDC, confirming the expected trend of isentropic compression. This quantitative trend supports the qualitative observations shown in

Figure 8 and provides numerical evidence of the thermodynamic state before ignition.

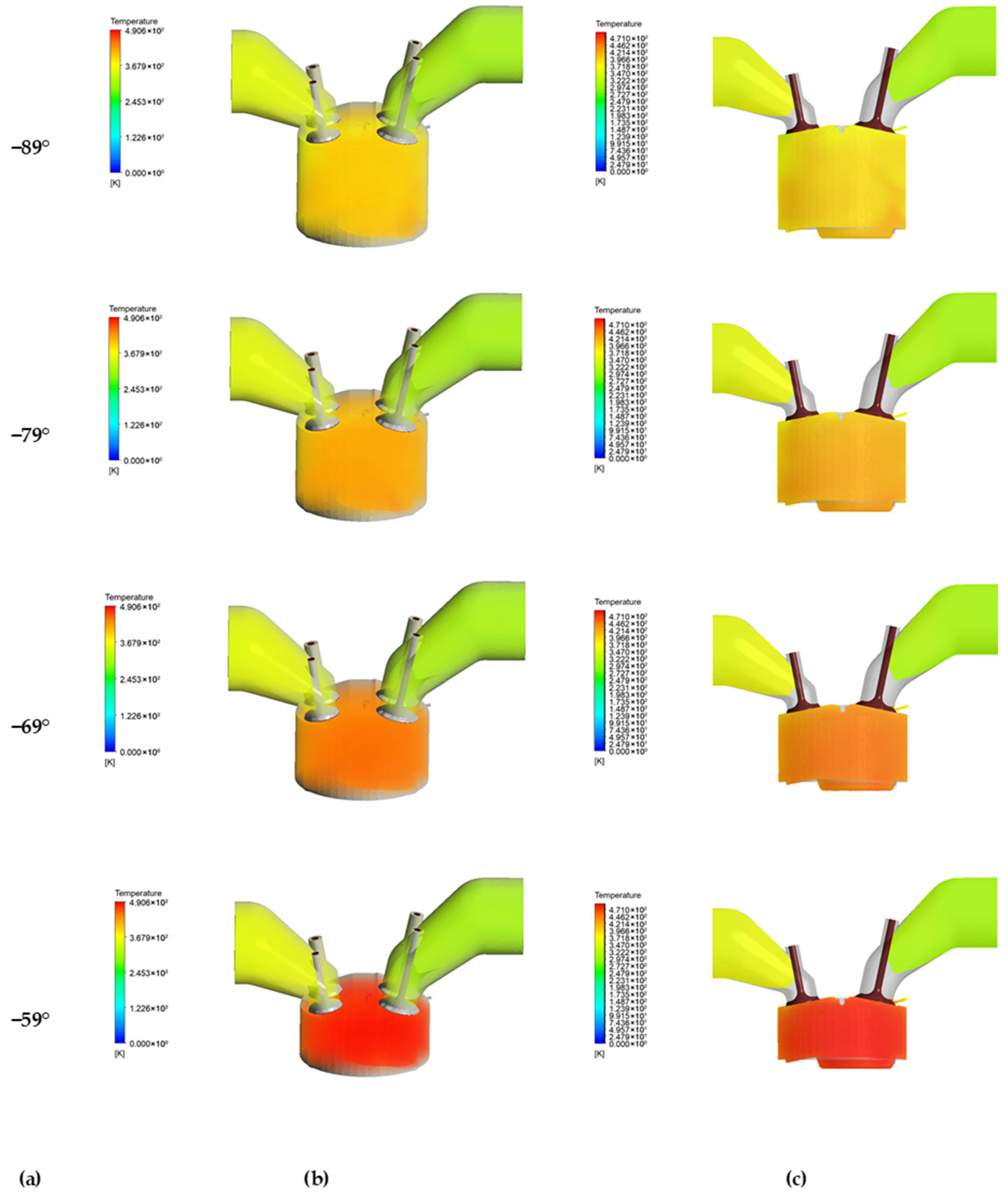

The temperature evolution is managed by a combination of aerodynamic effects, viscous dissipation, and adiabatic compression, since combustion heat release is not present in this stage of the simulation (

Figure 10).

At −129° BTDC, uniform temperature distribution is present, with slightly cooler regions near the intake port due to the inflow of fresh charge. The mean temperature remains close to ambient, which shows that the process is dominant in mixture mixing rather than compression.

By −119 BTDC, localized temperature increases appear at the liner where the hydrogen stream impacts. These thermal gradients arise from velocity deceleration and the conversion of kinetic energy into heat in the stagnation region. This stage gives a prediction where hot spots could form in a reactive case.

At −109 BTDC, when vortical structures intensify, shear heating becomes evident along the stream boundaries and near the central tumble vortex. High-shear zones show temperature changes in several Kelvins due to energy dissipation.

At −99 BTDC, noticeable thermal increases are present due to the piston’s upward motion while compressing the mixture. The piston bowl region exhibits the highest temperatures due to flow convergence and mild adiabatic heating.

Between −89° and −69° BTDC, compression becomes the dominant source of temperature rise. The temperature field becomes smoother as turbulence homogenizes the gas while reducing local peaks. The mean temperature rises constantly with early-stage adiabatic compression.

At −59 BTDC, the entire combustion chamber reaches nearly uniform temperature distribution. The slight gradient near the liner indicates residual velocity effects, but the mixture reaches thermal equilibrium before the ignition stage. This thermal uniformity is crucial for ensuring consistent ignition and minimizing hot-spot-induced preignition risks.

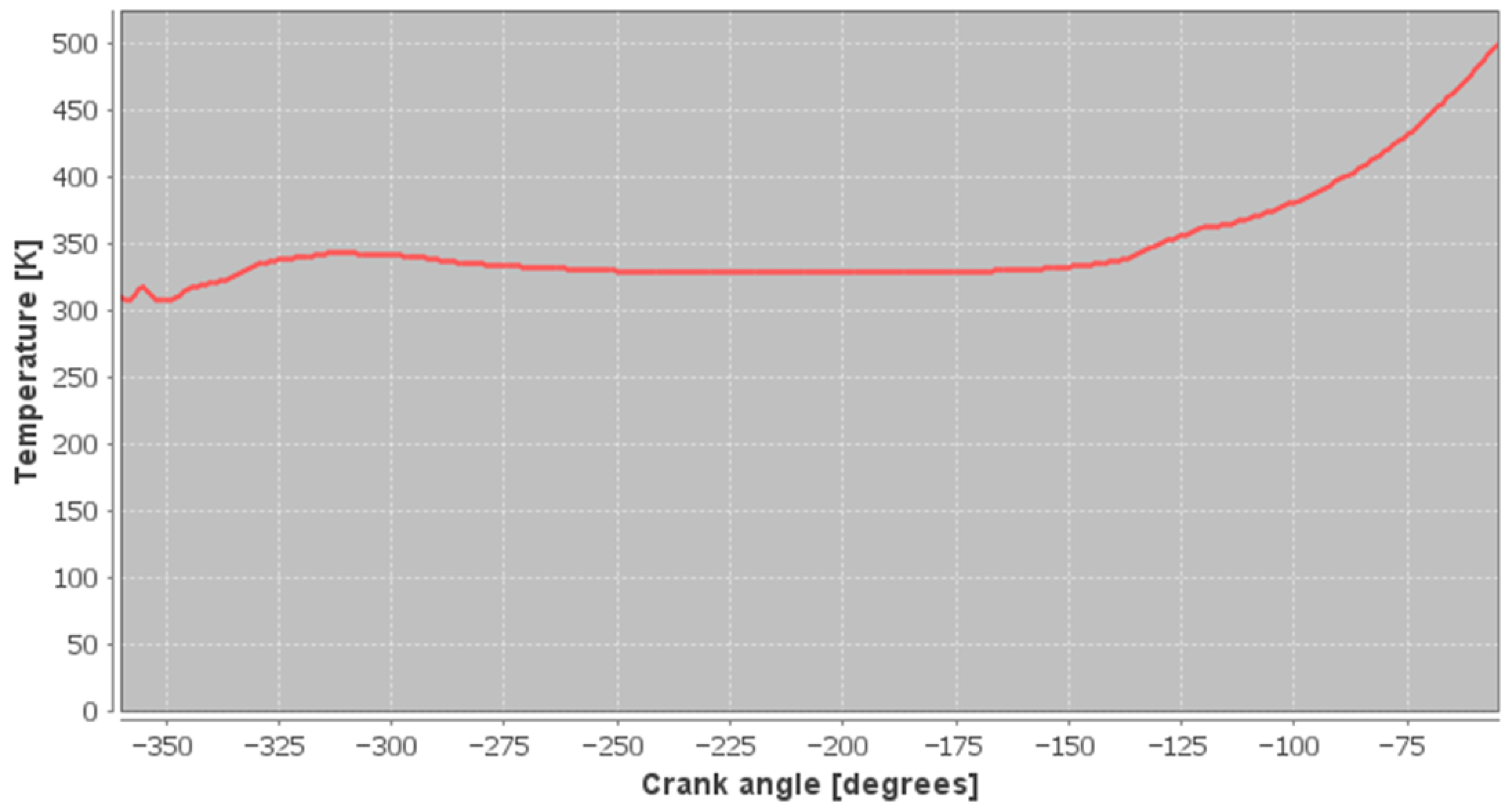

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show the evolution of the mean and maximum temperatures in the cylinder. The mean temperature gradually increases from approximately 315 K at the beginning of the suction to more than 480 K at −59 °B at the beginning of the suction, while the maximum values reach almost 500 K. These results quantify the adiabatic compression effect and confirm the thermal trends observed in

Figure 10.

The qualitative evolution of mass fraction, turbulence, pressure, and temperature confirms the gradual transition from a highly stratified hydrogen stream at the beginning of injection (−129° BTDC) to a nearly homogeneous mixture at −59° BTDC. The global performance indicators summarized in

Table 3 show that the combined effects of stream–wall interaction, piston-induced overturning, and bowl geometry enhance the mixture uniformity before ignition.

The results show that hydrogen direct injection and subsequent diffusion significantly influence mixture formation and local equivalence ratios. Quantitative evaluation of the hydrogen distribution in the cylinder confirmed that the mixture remained globally lean throughout the injection and early compression phases. For typical mass fraction levels observed in the chamber (0.01–0.05), the corresponding equivalence ratios ranged from φ = 0.35 to φ = 1.81, corresponding to λ = 2.85–0.55. Only the immediate core of the jet reached a momentary hydrogen mass fraction of 0.96, corresponding to an undiluted fuel stream and not representing a flammable region. No persistent zones with φ > 1 were detected, confirming that the injection strategy used prevents the formation of a locally rich mixture. These findings indicate that further optimization of in-cylinder flow structures and turbulence levels could improve mixture homogeneity and combustion stability. Therefore, future research will focus on refining the injector position and angle, valve timing, and injection strategy to enhance the overall combustion process and reduce cyclic variability.

Although experimental verification is planned for the next phase of the project, the reliability of the numerical predictions was assessed by comparing the main trends with the basic physical expectations and with previously published CFD studies on mixture formation in direct hydrogen injection engines [

25,

26,

27]. First, the evolution of the in-cylinder pressure and temperature during the intake and early compression stroke follows the expected isentropic behavior for a non-reacting gas at 1500 rpm, and the absolute values and gradients with respect to the crankshaft angle remain in the range reported for similar DI-H

2 simulations. Second, the simulated jet penetration, wall impact and subsequent formation of bowl-induced vortex structures are consistent with the experimentally observed hydrogen jet dynamics and with previous numerical investigations of DI hydrogen mixture formation [

25,

26,

27]. Third, the locally refined mesh in the flow domain (down to approximately 0.125 mm) provides on the order of 8–12 cells across the effective diameter of the flow, which is sufficient to resolve the development of the main shear layer and the emergence of turbulence without excessive numerical diffusion. Finally, no unphysical oscillations, false recirculation zones, or unrealistic mixture stratification were observed in the flow field, indicating that the solver behaved stably over the entire simulated crankshaft angle range. Together, these aspects support the claim that the presented CFD results form a solid basis for the analysis of the early mixture formation process before spark timing.