Influence of Noise Level and Reverberation on Children’s Performance and Effort in Primary Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Effects of Noise on Auditory Processing and Working Memory

1.2. Experimental Studies to Measure Noise Effects on Auditory Processing and Working Memory

1.3. Literature Gaps and Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Studies: Experimental Setup and Classrooms Characteristics

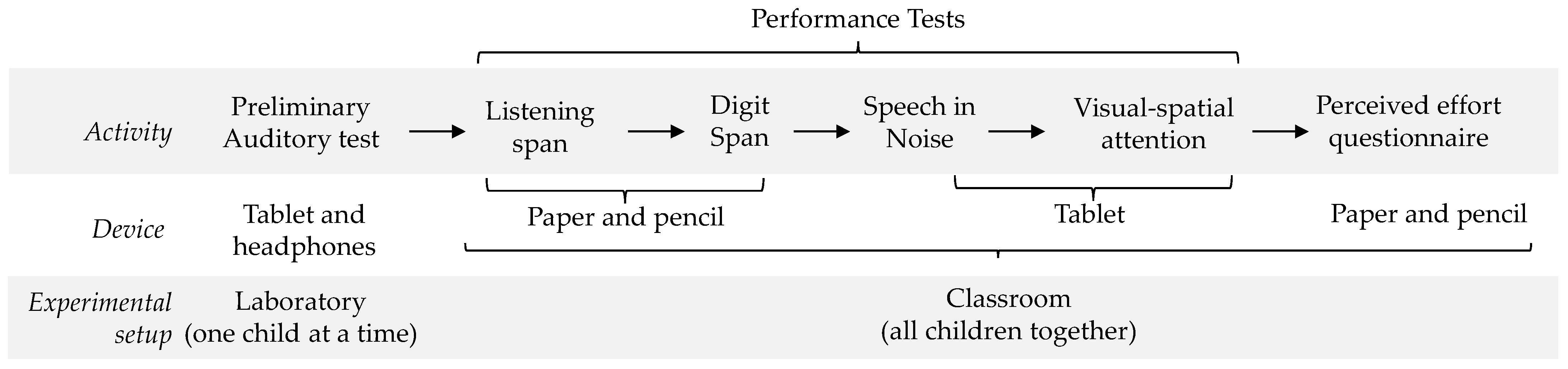

2.2. Cognitive and Listening Performance Tests

2.2.1. Listening Span Test

2.2.2. Digit Span Test

2.2.3. Speech-in-Noise Test

2.2.4. Visual–Spatial Attention Test

2.3. Cognitive Perceived Effort and Fatigue Questionnaire

2.4. Acoustic Conditions Experimented During Tests

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tests Performed in Ambient Noise

3.2. Perceived Effort and Fatigue Self-Assessment in Ambient Noise

3.3. Tests Performed in Induced Noise

3.4. Perceived Effort and Fatigue in Induced Noise

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Auditory working memory is significantly dependent on the equivalent continuous noise level measured during the tests. Despite the type of noise, condition regression analysis shows that at about 58 dBA, the average class performance is 2 points higher than the reference performance, which is the medium target for that kind of test. Moreover, an increment of 3 dBA determines a decrement of 1 point on the average performance of the class. In the tested conditions, the increase in noise level augments the performance variability, leading to the average performance exceeding the target value when classes are exposed to noise levels over 63–65 dBA (depending on the noise condition). Thus, this range may constitute a critical threshold for optimal classroom acoustic conditions, even though more statistical investigation is needed to support the finding.

- Visual–spatial working memory is significantly dependent on the equivalent continuous noise level measured during the tests, both in the Ambient and Induced Noise conditions. The mean performance score of the classes reaches the target score for 3rd to 5th school grades at 57 dBA in the Ambient Noise condition and 58 dBA in the Induced Noise condition, and it decreases with a slope of 2 points per 9 dBA. At 71 dBA, the mean score is about 2, which is very low considering that the students’ best performance does not exceed the score of 5, which is under the target value.

- Auditory processing in the speech-in-noise test is significantly dependent on the equivalent continuous level in both the Ambient and Induced Noise conditions. In the Ambient Noise condition, the mean response time was about 1.8 s at 52 dBA and about 3 s at 66 dBA. In the Induced Noise condition, the most correlated indicator was the number of distractors; in this case, the average number was 0.8 of distractors at 55 dBA and about 2 at 69 dBA, even if some children selected up to 6 distractors at the highest noise level.

- The limited number of classes restricts the generalisation of the results, despite meeting the minimum recommended sample size of eighty pupils, as determined by the sample size calculation [51].

- Direct comparison with other research is constrained by variation in experimental protocols, noise typologies, test delivery approaches, and field versus laboratory conditions.

- Despite the implementation of the regressions in the two noise conditions, no statistical test was carried out to directly compare the two conditions (e.g., using a repeated-measures ANOVA with Noise Condition as a factor). The only comparison between the two conditions was based on the results of the regression analysis.

- Unexpected behaviours among children, particularly in group settings, may confound results. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between individual and group testing in cognitive research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Studd, B.M.; Dockrell, J.E. The effects of environmental and classroom noise on the academic attainments of primary school children. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 123, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatte, M.; Bergström, K.; Lachmann, T. Does noise affect learning? A short review on noise effects on cognitive performance in children. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klatte, M.; Meis, M.; Sukowski, H.; Schick, A. Effects of irrelevant speech and traffic noise on speech perception and cognitive performance in elementary school children. Noise Health 2007, 9, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicciarelli, G.; Gheller, F.; Celli, M.; Arfè, B. The effect of unintelligible speech noise on children’s verbal working memory performance. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1565112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianxin, P.; Peng, J. The Effects of the Noise and Reverberation on the Working Memory Span of Children. Arch. Acoust. 2018, 43, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandita, H.L.; Jain, C. Developmental trends of verbal working memory in typically developing children. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 2025, 41, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudner, M.; Lyberg-Åhlander, V.; Brännström, J.; Nirme, J.; Pichora-Fuller, M.K.; Sahlén, B. Listening effort and fatigue in school-age children who use bilateral cochlear implants and children with normal hearing: A comparison in classroom-like listening conditions. Ear Hear. 2019, 40, 639–648. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, H.; Gomerdinger, A.E.; Herzberg, D.W.Y. How Long Can They Focus in School-Age Children with Hearing Loss. J. Educ. Audiol. 2014, 20, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bess, F.H.; Gustafson, S.J.; Hornsby, B.W.Y. How Hard Can It Be to Listen? Fatigue in School-Age Children with Hearing Loss: A Preliminary Study. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2014, 57, 2113–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Gheller, F.; Spicciarelli, G.; Scimemi, P.; Arfé, B. The Effects of Noise on Children’s Cognitive Performance: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 698–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, C.; Pellegatti, M.; Garraffa, M.; di Domenico, A.; Prodi, N. Be Quiet Effects of Competing Speakers and Acoustic Conditions on Working Memory in Hearing-Impaired Children. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5066. [Google Scholar]

- Prodi, N.; Visentin, C.; Feletti, A. Systematic Review of Literature on Speech Intelligibility and Classroom Acoustics in Elementary Schools. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2023, 54, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, A.T.V.; Santos, J.N.; Oliveira, R.C.; Magalhães, M.D.C. Effect of classroom acoustics on the speech intelligibility of students. CoDAS 2014, 26, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.S.; Sato, H. Speech intelligibility of young school-aged children in the presence of real-life classroom noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 115, 2413. [Google Scholar]

- Prodi, N.; Visentin, C.; Peretti, A.; Griguolo, J.; Bartolucci, G.B. Investigating listening effort in classrooms for 5- to 7-year-old children. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2019, 50, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magimairaj, B.M.; Nagaraj, N.K. Speech perception in noise, working memory, and attention in children: A scoping review. Int. J. Audiol. 2023, 62, 795–809. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J.R.; Carrano, C.; Osman, H. Working memory and speech recognition performance in noise: Implications for classroom accommodations. Commun. Disord. Deaf Stud. Hear. Aids 2015, 3, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Clair-Thompson, H.L.; Gathercole, S.E. Executive functions and achievements in school: Shifting, updating, inhibition, and working memory. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2006, 59, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.M. Irrelevant speech effect and children: Theoretical implications of developmental change. Mem. Cogn. 2002, 30, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, P.M. Human Memory and the Medial Temporal Region of the Brain. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, R.P.; Van Zandvoort, M.J.; Postma, A.; Kappelle, L.J.; De Haan, E.H. The Corsi block-tapping task: Standardization and normative data. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2000, 7, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waye, K.P.; Van Kamp, I.; Dellve, L. Validation of a questionnaire measuring preschool children’s reactions to and coping with noise in a repeated measurement design. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, e002408. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leonardo, L.; Secchi, S.; Vettori, G.; Bigozzi, L. The sound of silence: Children’s own perspectives on their hearing and listening in classrooms with different acoustic conditions. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 3803–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettori, G.; Di Leonardo, L.; Secchi, S.; Astolfi, A.; Bigozzi, L. Primary school children’s verbal working memory performance in classrooms with different acoustic conditions. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 203, 109256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massonnié, J.; Frasseto, G.L.; Mareschal, D. Is Classroom Noise Always Bad for Children? The Contribution of Age and Selective Attention to Creative Performance in Noise. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Ghrist, S.K.; Bourgignon, M.; Niesen, M.; Wens, V.; Hassid, S.; Choufani, G.; Joanisse, V.; Hari, R.; Goldman, S.; De Tiège, X.; et al. Impact of prematurity and co-morbidities on the auditory system and its development. Neuroscience 2019, 389, 2938–2950. [Google Scholar]

- Klatte, M.; Hellbrück, J. Effects of noise on children’s reading, writing and creative performance in a classroom-like setting. Appl. Acoust. 2013, 74, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, O.; Castro-Alonso, J.C.; Paas, F.; Sweller, J. Evaluation of children’s cognitive load in processing and storage of their spatial working memory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 918048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarrigle, R.; Munro, K.J.; Dawes, P.; Stewart, A.J.; Moore, D.R.; Barry, J.G.; Amitay, S. Listening effort and fatigue: What exactly are we measuring? A British Society of Audiology Cognition in Hearing Special Interest Group ‘white paper’. Int. J. Audiol. 2014, 53, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C.B.; Tharpe, A.M. Listening Effort and Fatigue in School-Age Children With and Without Hearing Loss. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2002, 45, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; Van Merriënboer, J.J.; Paas, F.G. Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 10, 251–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Van Merriënboer, J.J. The efficiency of instructional conditions: An approach to combine mental effort and performance measures. Hum. Factors 1993, 35, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, N.; Horne, J.; Barber, A.; Lindqvist, S. Willing to Think Hard? The Subjective Value of Cognitive Effort in Children. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3382-2; Acoustics—Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters—Part 2: Reverberation Time in Ordinary Rooms. International Organisation for Standardisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- CEI EN IEC 60268-16; Apparecchiature per Sistemi Elettroacustici, Parte 16: Metodi di Valutazione Dell’intelligibilità del Parlato per Mezzo Dell’indice di Trasmissione del Parlato. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- UNI 11532-2; Caratteristiche Acustiche Interne di Ambienti Confinati—Metodi di Progettazione e Tecniche di Valutazione—Parte 2: Settore Scolastico. Italian National Organisation for Standardisation: Milan, Italy, 2020.

- Daneman, M.; Carpenter, P.A. Individual differences in working memory and reading. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1980, 19, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beni, R.; Palladino, P.; Pazzaglia, F.; Cornoldi, C. Increases in intrusion errors and working memory deficit of poor comprehenders. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1998, 51, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, P. Listening span test for children. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bisiacchi, P.S.; Cendron, M.; Gugliotta, M.; Tressoldi, P.E.; Vio, C. BVN 5-11: Batteria Neuropsicologica per l’età Evolutiva; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, E.; Genovese, E.; Orzan, E.; Turrini, M. Valutazione Della Percezione Verbale nel Bambino Ipoacusico; Ecumenica Editrice: Bari, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A. Working memory. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.; Logie, R.H. Working memory: The multiple component model. In Models of Working Memory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 28–61. [Google Scholar]

- Borella, E.; De Ribaupierre, A. The role of working memory in text comprehension. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2014, 26, 785–799. [Google Scholar]

- Giofrè, D.; Mammarella, I.C.; Cornoldi, C. Visualspatial working memory in mathematics. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2013, 26, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mammarella, I.C.; Stefani, F.N.; Giofrè, D.; Toso, C. BVS-Corsi-2. Batteria per la Valutazione Della Memoria di Lavoro Visuospaziale (8-12 Anni); Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brännström, K.J.; Rudner, M.; Carlie, J.; Sahlén, B.; Gulz, A.; Andersson, K.; Johansson, R. Listening effort and fatigue in native and non-native primary school children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2021, 210, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massonnié, J.; Frasseto, P.; Ng-Knight, T.; Gilligan-Lee, K.; Kirkham, N.; Mareschal, D. Children’s Effortful Control Skills, but Not Their Prosocial Skills, Relate to Their Reactions to Classroom Noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, F.; Gasparella, A.; Tzempelikos, A.; Pittana, I.; Cappelletti, F. Impact of personal and contextual factors on multi-domain sensation in classrooms: Results from a field study. Build. Environ. 2025, 280, 112892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockrell, J.E.; Shield, B.M. Acoustical barriers in classrooms: The impact of noise on performance in the classroom. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 32, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.D.; Eliasziw, M.; Donner, A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| School Grade | Class | Ambient Noise | Induced Noise | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | F/M (%) | n | F/M (%) | ||

| 3rd | DG-3A | 19 | 53/47 | 20 | 50/50 |

| DG-3B | 20 | 60/40 | 19 | 58/42 | |

| 4th | MA-4A | 17 | 47/53 | 16 | 50/50 |

| MA-4B | 12 | 42/58 | 10 | 50/50 | |

| DE-4A | 15 | 53/47 | 18 | 56/44 | |

| DE-4B | 15 | 73/27 | 16 | 69/31 | |

| 5th | MO-5A | 17 | 59/41 | 15 | 63/37 |

| MO-5B | 16 | 50/50 | 15 | 53/47 | |

| T20 [s] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom | 125 Hz | 250 Hz | 500 Hz | 1 kHz | 2 kHz | 4 kHz |

| MA-4A | 0.84 | 0.9 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 1.21 | 0.96 |

| MA-4B | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 0.8 |

| DE-4A | 1.96 | 1.52 | 1.53 | 1.51 | 1.38 | 1.16 |

| DE-4B | 1.86 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.62 | 1.49 | 1.22 |

| DG-3A | 1.47 | 1.44 | 1.17 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.72 |

| DG-3B | 1.05 | 1.03 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.5 | 0.51 |

| MO-5A | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| MO-5B | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.51 |

| C50 [dB] | STI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom | 125 Hz | 250 Hz | 500 Hz | 1 kHz | 2 kHz | 4 kHz | |

| MA-4A | 3.2 | 3.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 0.79 |

| MA-4B | 3 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 0.8 |

| DE-4A | −5.9 | −4.2 | −3 | −2.1 | −0.9 | 0.3 | 0.72 |

| DE-4B | −5.1 | −2.2 | −2.4 | −1.8 | −0.3 | 1.3 | 0.74 |

| DG-3A | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 0.8 |

| DG-3B | 2 | 3 | 5.6 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 0.88 |

| MO-5A | 3.8 | 7.8 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 9.9 | 0.9 |

| MO-5B | 3.6 | 8.6 | 10.5 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 0.9 |

| Test Type | Cognitive/Listening Function | Type of Check | Performance Indicator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory tests | Listening Span | Verbal working memory | Number of correct true/false responses | Score standard deviation |

| Number of correctly recalled words | Score standard deviation | |||

| Digit Span | Verbal working memory | Number of correct responses | Calculated score | |

| Speech in noise | Intelligibility | Accuracy and response time | Number of errors | |

| Number of distractors | ||||

| Response time | ||||

| Non-auditory test | Corsi visual–spatial test | Visual–spatial working memory | Number of correct responses | Calculated mean score |

| # | Statement | Evaluation Scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you feel tired? | 1 = “not at all” 2 = “a little” 3 = “moderately” 4 = “very” 5 = “extremely” |

| 2 | Do you have headache? | |

| 3 | Were the games difficult? | |

| 4 | Was it hard to pay attention? | |

| 5 | Was it hard to understand words/numbers? | |

| 6 | Was it hard to remember words/numbers? |

| Classroom | LAeq [dBA] During Test/Questionnaire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listening Span | Digit Span | Visuospatial Attention | Speech in Noise | Cognitive Effort | |

| MA-4A | 65.0 | 66.4 | - | 56.3 | 64.8 |

| MA-4B | 67.5 | 68.0 | - | 66.2 | 66.6 |

| DE-4A | 65.2 | 66.5 | 69.1 | 59.7 | 66.4 |

| DE-4B | 61.5 | 65.0 | 69.6 | 57.5 | 64.5 |

| DG-3A | 67.4 | 69.6 | 69.1 | - | 68.8 |

| DG-3B | 66.2 | 67.0 | 68.8 | 61.4 | 66.7 |

| MO-5A | 57.9 | 57.9 | 57.4 | 52.3 | 57.3 |

| MO-5B | 57.6 | 64.3 | 56.6 | 52.0 | 59.3 |

| Classroom | LAeq [dBA] During Test/Questionnaire | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listening Span | Digit Span | Visual–Spatial Attention | Speech in Noise | Cognitive Effort | |

| MA-4A | 64.5 | 64.8 | 67.8 | 63.1 | 65.7 |

| MA-4B | 69.1 | 70.8 | 66.7 | 69.1 | 69.2 |

| DE-4A | 62.7 | 65.2 | 69.1 | 68.7 | 66.7 |

| DE-4B | 66.2 | 67.6 | 69.6 | 64.4 | 65.9 |

| DG-3A | 67.6 | 68.8 | 70.2 | 64.2 | 68.8 |

| DG-3B | 66.6 | 71.4 | 70.8 | 69.1 | 69.8 |

| MO-5A | 59.2 | 59.5 | 61.5 | 57.3 | 60.2 |

| MO-5B | 56.7 | 58.8 | 57.8 | 55.5 | 57.5 |

| Test Type | Pearson Analysis (131 Scores) | Regression Analysis (8 Mean Values) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Slope | p-Value | R2 | |

| Listening Span (T/F) | −0.01 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Listening Span (recalled words) | −0.67 | −0.3253 | <0.001 * | 0.73 |

| Digit Span | 0.00 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Visual–spatial attention | −0.55 | −0.2668 | <0.001 * | 0.95 |

| Speech in noise (correct ans.) | −0.28 | −1585 | 0.003 * | 0.30 |

| Speech in noise (# distractors) | 0.27 | 0.1046 | 0.004 * | 0.27 |

| Speech in noise mean RT | 0.48 | 0.0665 | <0.001 * | 0.84 |

| Test Type | Pearson Analysis (131 Scores) | Regression Analysis (8 Mean Values) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Slope | p-Value | R2 | |

| Listening Span (T/F) | −0.11 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Listening Span (recalled words) | −0.15 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Digit Span | 0.00 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Visual–spatial attention | −0.36 | −2.156 | <0.001 * | 0.40 |

| Speech in noise (correct ans.) | −0.34 | −1.886 | <0.001 * | 0.44 |

| Speech in noise (# distractors) | 0.35 | 1.318 | <0.001 * | 0.45 |

| Speech in noise mean RT | 0.25 | 0.336 | <0.001 * | 0.22 |

| Cognitive Effort/Fatigue | Pearson Analysis (131 Scores) | Regression Analysis (8 Mean Values) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Slope | p-Value | R2 | |

| 1. Do you feel tired? | 0.03 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 2. Do you have headache? | 0.02 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 3. Were the games difficult? | 0.11 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 4. Was it hard to pay attention? | 0.30 | 0.094 | 0.001 * | 0.81 |

| 5. Was it hard to understand words/numbers? | 0.21 | 0.051 | 0.026 * | 0.47 |

| 6. Was it hard to remember words/numbers? | 0.31 | 0.102 | 0.001 * | 0.64 |

| Test Type | Pearson Analysis (131 Scores) | Regression Analysis (8 Mean Values) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Slope | p-Value | R2 | |

| Listening Span (T/F) | 0.11 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Listening Span (words recalling) | −0.56 | −0.2625 | <0.001 * | 0.75 |

| Digit Span | −0.04 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Visual–spatial attention | −0.38 | −0.2474 | <0.001 * | 0.75 |

| Speech in noise (correct ans.) | −0.27 | −0.1502 | 0.012 * | 0.56 |

| Speech in noise (# distractors) | 0.32 | 0.0982 | 0.003 * | 0.91 |

| Speech in noise mean RT) | 0.02 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Test Type | Pearson Analysis (131 Scores) | Regression Analysis (8 Mean Values) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Slope | p-Value | R2 | |

| Listening Span (T/F) | 0.07 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Listening Span (recalled words) | 0.04 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Digit Span | 0.10 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Visual–spatial attention | −0.08 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Speech in noise (correct ans.) | −0.15 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Speech in noise (# distractors) | 0.10 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Speech in noise mean RT | −0.10 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| Cognitive Effort/Fatigue | Pearson Analysis (131 Scores) | Regression Analysis (8 Mean Values) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | Slope | p-Value | R2 | |

| 1. Do you feel tired? | 0.14 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 2. Do you have headache? | 0.08 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 3. Were the games difficult? | 0.22 | 0.0524 | <0.001 * | 0.43 |

| 4. Was it hard to pay attention? | 0.08 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 5. Was it hard to understand words/numbers? | 0.13 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 6. Was it hard to remember words/numbers? | 0.11 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

| 7. Have you been bothered by noises? | −0.02 | n.c. | n.c. | n.c. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pittana, I.; Pavarin, C.; Pavanello, I.; Di Bella, A.; Romagnoni, P.; Scimemi, P.; Cappelletti, F. Influence of Noise Level and Reverberation on Children’s Performance and Effort in Primary Schools. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413213

Pittana I, Pavarin C, Pavanello I, Di Bella A, Romagnoni P, Scimemi P, Cappelletti F. Influence of Noise Level and Reverberation on Children’s Performance and Effort in Primary Schools. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413213

Chicago/Turabian StylePittana, Ilaria, Cora Pavarin, Irene Pavanello, Antonino Di Bella, Piercarlo Romagnoni, Pietro Scimemi, and Francesca Cappelletti. 2025. "Influence of Noise Level and Reverberation on Children’s Performance and Effort in Primary Schools" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413213

APA StylePittana, I., Pavarin, C., Pavanello, I., Di Bella, A., Romagnoni, P., Scimemi, P., & Cappelletti, F. (2025). Influence of Noise Level and Reverberation on Children’s Performance and Effort in Primary Schools. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13213. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413213