1. Introduction

Thermal recovery technologies primarily involving steam huff and puff, steam flooding, and Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) have been the main development technologies for extra-heavy and ultra-heavy oil reservoirs for many years. Statistics show that these steam injection thermal recovery technologies typically use coal- or gas-fired boilers to generate steam, with carbon emissions as high as 1.2 tCO

2/t oil. The reservoir operating temperature exceeds 250 °C, and heat losses to the overburden and underburden continuously increase during development, with an average steam thermal efficiency of 34.7% [

1,

2]. For extra-heavy and ultra-heavy oil reservoirs, extensive exploration and pilot testing of low-carbon green recovery technologies have been conducted domestically and internationally over the years, achieving certain results [

3,

4,

5]. Among them, Mr. Butler, the inventor of SAGD, proposed the Vapor Extraction (VAPEX) process in the 1980s. The technical principle involves injecting propane or butane solvents at reservoir temperature into the reservoir, utilizing molecular diffusion between the solvent and crude oil to achieve viscosity reduction and gravity drainage. Pilot tests were conducted in Canadian oil sands areas. However, due to the low molecular diffusion capacity between the cold solvent and heavy oil, production rates failed to reach commercial levels, leading to shutdowns. Subsequent research found that increasing the solvent temperature could significantly increase the diffusion rate and drainage rate. Based on this, from 2013 to 2015, Canada’s Suncor injected hot solvent at 80–120 °C into the reservoir, achieving successful trials with production rates reaching SAGD levels and a predicted recovery factor of 67% [

6]. By using pure solvent instead of steam, carbon emissions were reduced by 81% [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Compared to the pure solvent extraction process, adding small amounts of light hydrocarbon solvents to steam for Solvent Assisted SAGD (SA-SAGD) has matured and been commercially applied abroad [

11].

Statistics from abroad show that Solvent Assisted SAGD can increase oil production rates, but the extent of emission reduction is limited. Solvent extraction tests were all conducted in new wells. However, in domestic SAGD development areas, mainly represented by the Fengcheng Oilfield in Xinjiang, operations have largely transitioned to the SAGD production stage. The mechanisms of thermal field expansion, solvent chamber distribution, and drainage in already SAGD-developed wells differ, making it difficult to assess the suitability of solvent extraction. Furthermore, the production level and recovery factor of solvent extraction, its potential for carbon emission reduction, and technical feasibility are unclear. Additionally, the solvent thermal stability is not fully understood. Compared to surface boiler heating, using downhole electrical heating to vaporize the solvent is an efficient new approach, but its mechanism of action requires experimental verification [

12,

13,

14].

This paper addresses the above issues by primarily conducting molecular diffusion experiments between different solvents and heavy oil to optimize the best solvent system; deriving a theoretical model for drainage in electrical heating solvent extraction; and based on this, designing and conducting 3D-scaled physical simulation experiments of electrical heating solvent extraction to explore its drainage mechanisms and low-carbon production behavior.

2. Heat Transfer and Temperature Rise Characteristics of Electrical Heating in the Near-Wellbore Formation

The primary mechanism of electrical-heating-assisted SAGD and solvent extraction is to increase the temperature in the wellbore and near-wellbore formation, thereby significantly reducing crude oil viscosity and enhancing oil inflow capacity. However, the efficiency and extent of heat transfer and temperature rise are greatly influenced by the fluids in the near-wellbore formation. Therefore, before conducting physical simulation experiments on electrical-heating-assisted recovery, it is necessary to compare the heat transfer characteristics of different fluids to clarify the heating patterns.

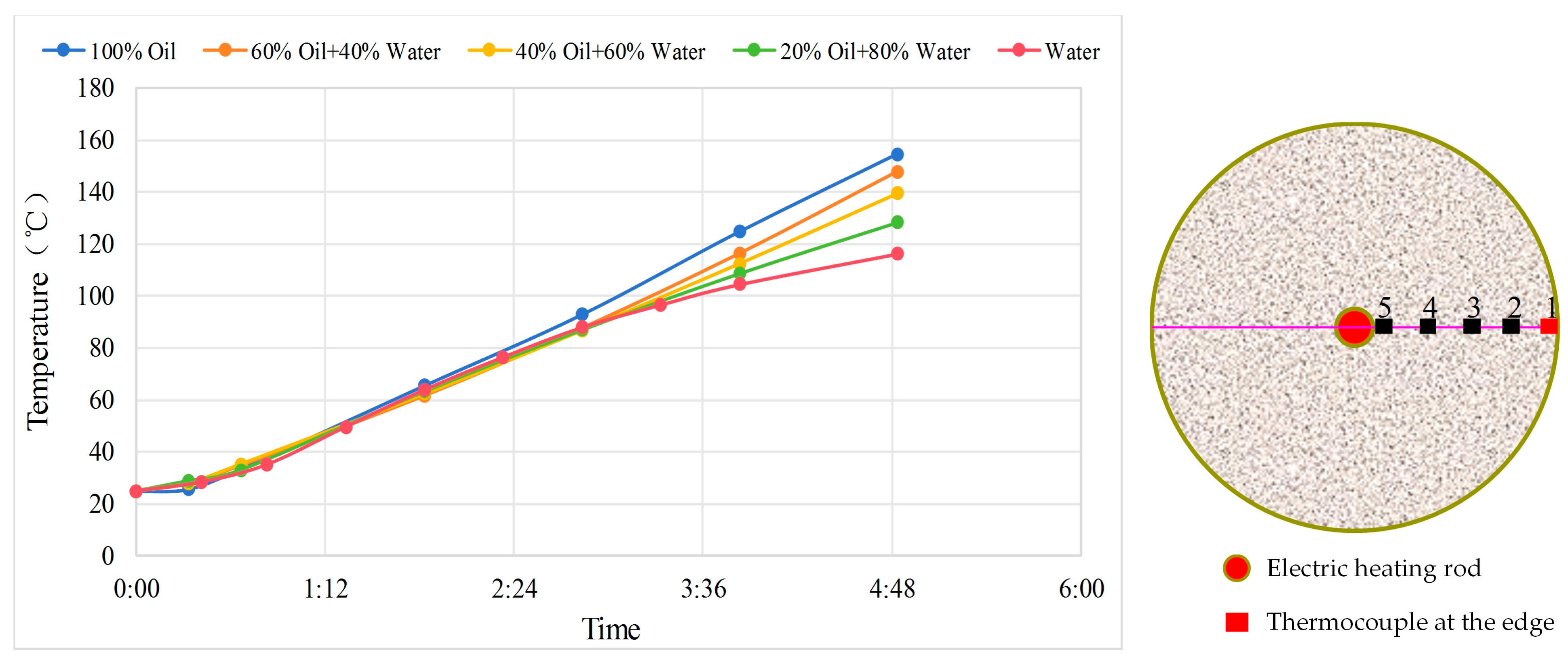

For this purpose, a packed sand cylindrical model was used, and five sets of experiments with different heat-transfer fluids were designed. The experimental setup consists of a 3D radial sand-packed model fabricated from special stainless steel and a heating compensation sleeve. The sand-packed model has dimensions of 17.8 cm in diameter × 60 cm in length as shown in

Figure 1, with a maximum operating pressure of 20.0 MPa and a temperature resistance range of up to 400 °C. An electric heating rod positioned at the center provides a maximum power of 1200 W/m and a maximum surface temperature of 300 °C. Five sets of thermocouples are uniformly distributed across the model cross-section for real-time monitoring.

After sand packing, the model was evacuated and then saturated with five different oil-water ratio combinations. Following electrical heating, temperature measurements from the thermocouples were compared to evaluate the heat transfer performance across different schemes. The specific wellbore fluids for each scheme are as follows: 100% water, 20% oil–80% water, 40% oil–60% water, 60% oil–40% water, 100% oil.

A comparison of the temperature rise rate at the edge measurement point (see

Figure 2) shows that for different media, the initial temperature rise at the edge differs slightly, attributed mainly to heat conduction before the high-temperature front arrives. After 3 h, the differences gradually amplify because the thermal conductivity of crude oil is higher, leading to faster heating.

A comparison of the temperature rise rate near the electrical heater (see

Figure 3) shows that the temperature rise rate is higher for oil and slower for water, primarily because water undergoes vaporization phase change, transforming pure heat conduction into heat convection, accelerating the outward transfer and loss of heat.

Therefore, in the physical simulation experiments conducted in this paper, electrical-heating-assisted solvent extraction (without steam injection) was adopted. This ensures that, except for small residual amounts of water from the prior SAGD steam chamber, the formation near the wellbore contains a mixture of crude oil and solvent, thus achieving better heat transfer and temperature rise effects.

3. Coupled Theoretical Model for SAGD and Solvent Extraction Drainage

This paper simulates solvent extraction within a SAGD-developed reservoir. Therefore, during the SAGD production stage, it must conform to SAGD behavior; during the solvent extraction stage, production must conform to solvent extraction drainage behavior, considering the synergistic effect of electrical heating. Thus, a coupled theoretical model for SAGD and solvent extraction drainage needs to be established.

First, according to Butler’s classical drainage theory formula [

15,

16,

17], the oil production rate during the SAGD steam chamber rise stage is:

After the steam chamber reaches the top and spreads laterally, the peak oil production rate is:

When switching to solvent extraction production after the SAGD steam chamber has risen to the top of the reservoir and begun lateral expansion, the production conforms to the characteristics of solvent extraction. Considering the synergistic enhancement of electrical heating, the corresponding solvent extraction drainage theoretical model is as follows [

18]:

where

If solvent extraction is only conducted during the steam chamber expansion stage, and conventional SAGD operation is resumed when the chamber enters the decline stage, the oil production rate during the decline stage is:

By combining Equations (1), (3) and (5), the oil production rate under the SAGD—Electrical Heating Solvent Extraction—SAGD development mode at different times can be calculated.

4. Design of Physical Simulation for Electrical-Heating-Assisted Solvent Extraction

4.1. Scaling Based on Similarity Criteria

According to Butler’s 3D physical simulation similarity criteria for pure steam SAGD, and referencing reservoir parameters, the parameters selected for the experimental simulation need to conform to the following basic similarity criterion equation [

15,

16,

17]:

To characterize the effect of electrical heating temperature rise on oil viscosity, considering that electrical heating primarily affects oil viscosity, the following relationship between oil viscosity and temperature exists for heavy oil reservoirs:

For Equation (7), for a specific reservoir, the values of

m and

b are obtained by normalizing the relationship between oil viscosity and temperature. Transforming Equation (7) yields:

Substituting Equation (8) into Equation (6) gives the basic similarity criterion equation under electrical heating conditions:

Based on the similarity criteria, the physical model parameters were scaled, establishing the similarity scale model (see

Table 1) and experimental procedure for 3D-scaled physical simulation of electrical-heating-assisted recovery.

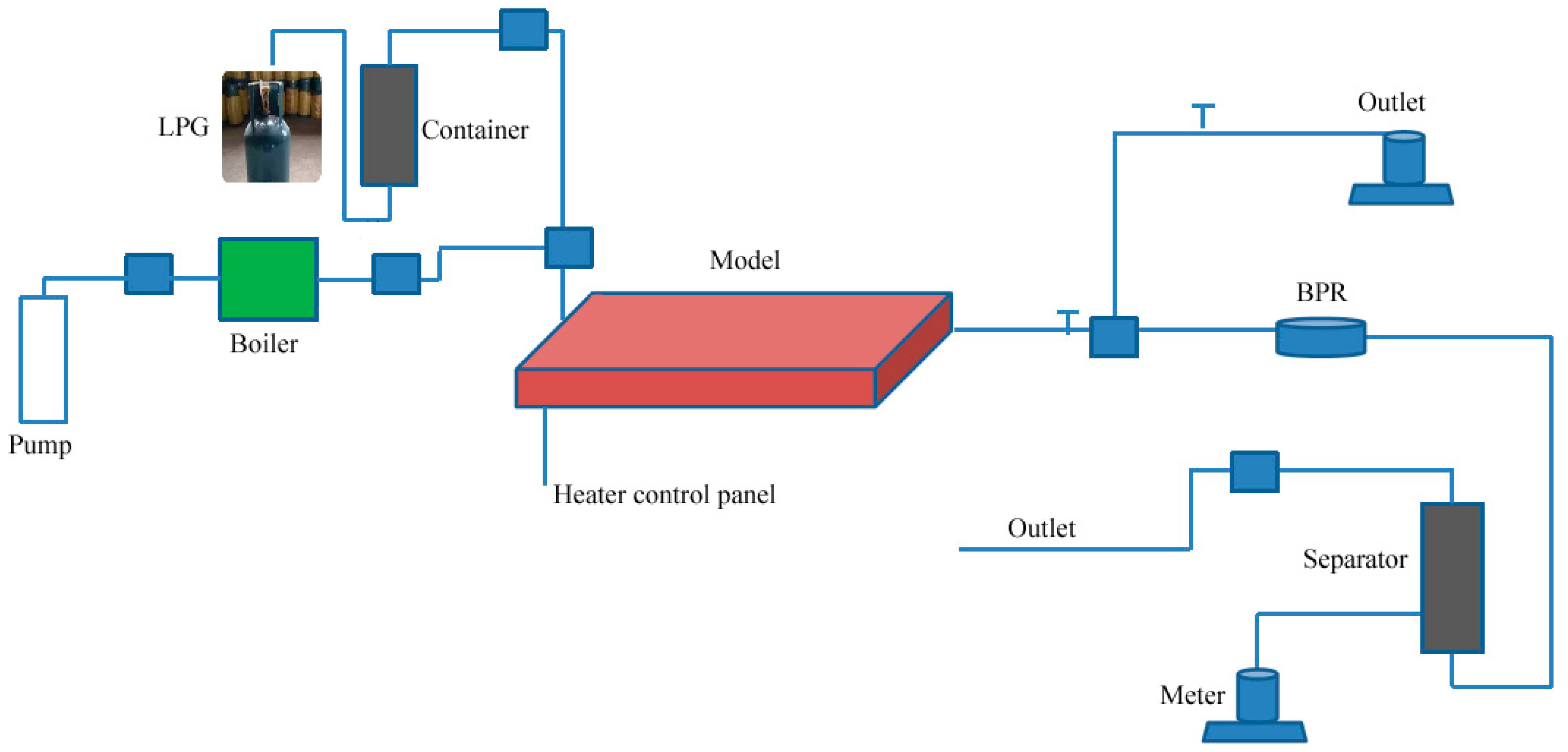

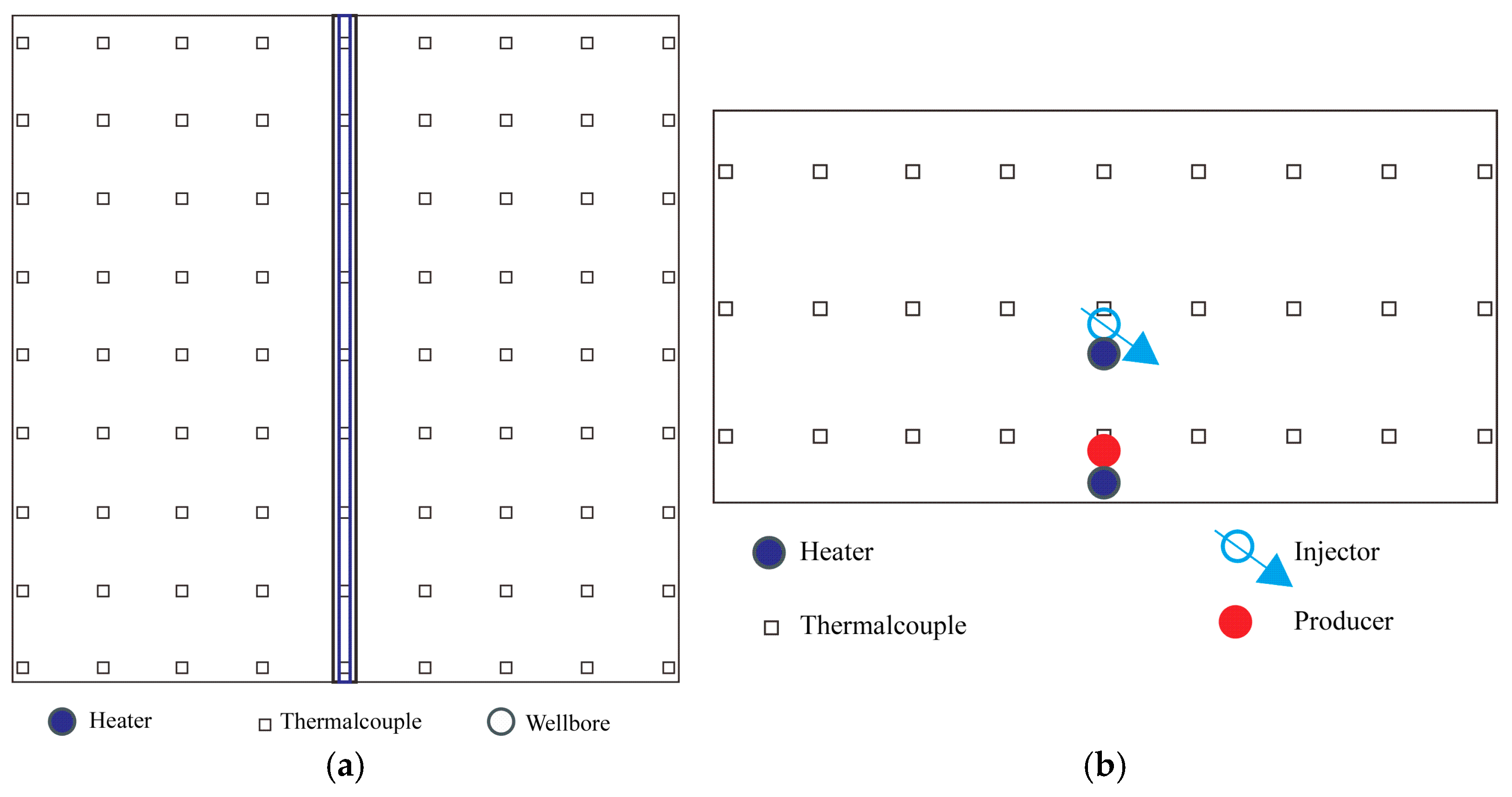

The 3D-scaled physical simulation experimental setup for electrical-heating-assisted steam injection mainly consists of five parts (see

Figure 4): (1) Injection module, including solvent gas cylinder (LPG used here), steam generator, high-pressure displacement pump, intermediate containers, etc.; (2) High-temperature high-pressure 3D model body (see

Figure 4), dimensions 40 cm × 40 cm × 20 cm, with 9 × 9 = 81 temperature measurement thermocouples uniformly deployed in the plane, and three layers deployed vertically, totaling 243 thermocouples (see

Figure 5). The model comprises a three-dimensional sand-packed model constructed from special stainless steel and a thermal insulation jacket, with a maximum operating pressure of 10.0 MPa and a maximum temperature of 380 °C. The center of the model contains a pair of slotted horizontal wells serving as the inlet (injection well) or outlet (production well), along with a pair of electric heating rods positioned adjacent to the horizontal wells to enable wellbore electrical heating. The thermal insulation jacket automatically adjusts its heating temperature via temperature sensors in contact with the model’s outer wall, maintaining consistency with the external boundary temperature of the model; (3) Data acquisition system, including a data acquisition box and monitoring/mapping software; (4) Production system, including high-temperature back-pressure valve, enclosed produced fluid/gas separator, electronic balance, etc.; (5) Electrical control module, including electrical heaters, intelligent control box, etc.

4.2. Experimental Procedure

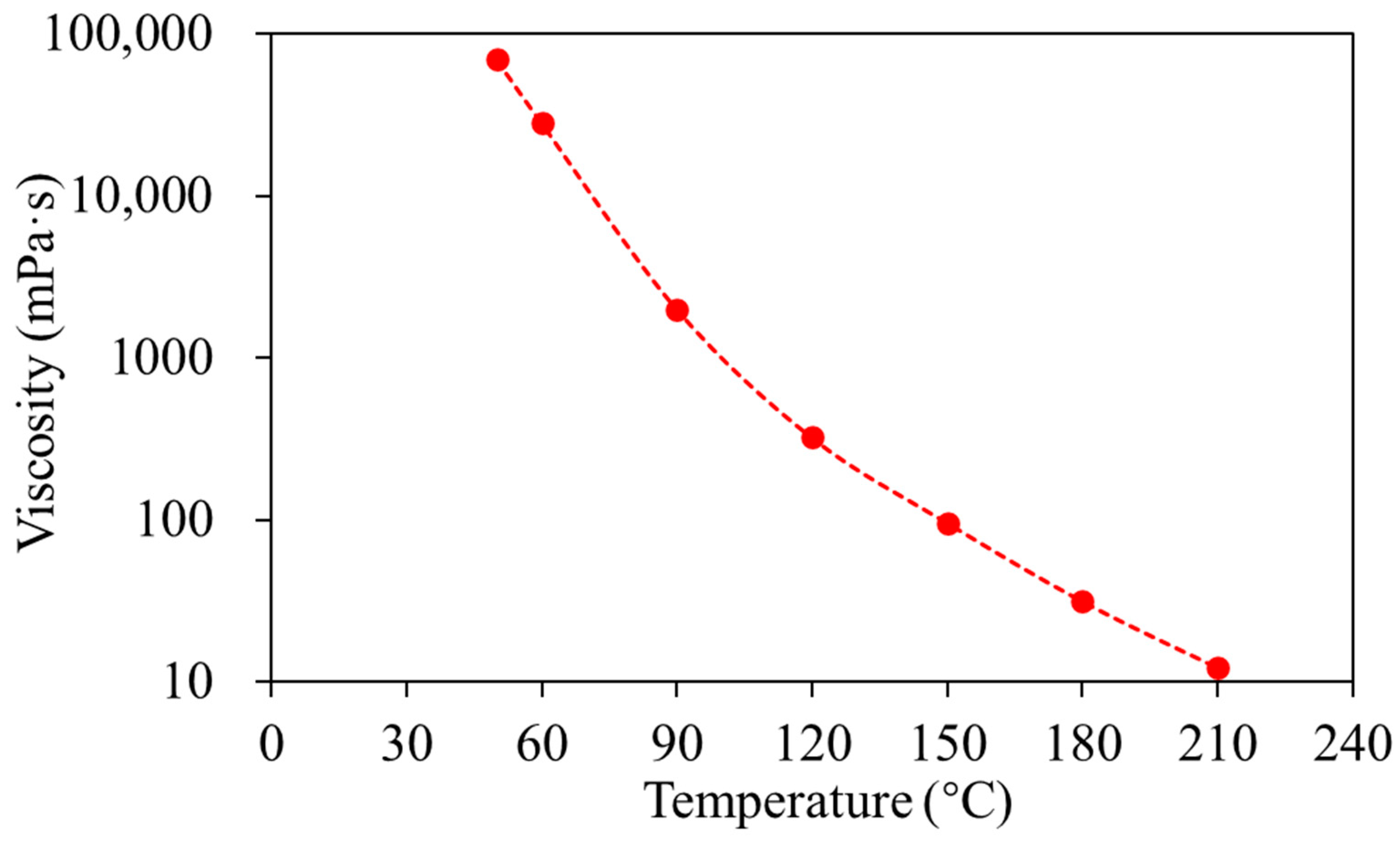

Conducting physical simulation experiments involving the superposition of electrical heating, steam injection, and solvent extraction is challenging. The experimental procedure also differs somewhat from conventional steam injection SAGD. The overall experiment consists of 13 steps: (1) Set up the experimental injection and production flow lines. (2) Based on the particle size distribution of unconsolidated sandstone in heterogeneous SAGD reservoirs, combined with the physical property similarity criteria, design the sand packing particle size distribution, perform heterogeneous reservoir packing, and compact using a top piston. (3) Evacuate the model to 0.01 MPa, hold for one hour. (4) Saturate the model with water by injecting the prepared formation water into the model body, age for 48 h after injection. (5) Saturate with oil: Use a multi-point injection method to inject heated crude oil into the model from different bottom locations.

Figure 6 shows the dependence of oil viscosity on temperature. When the outlet oil cut reaches 100%, continue injecting 0.1 PV, then stop the oil injection and age for 48 h. (6) Turn on the electrical heaters in both injector and producer simultaneously to conduct SAGD electrical preheating. Meanwhile, use the automatic control box to monitor the heater surface temperature, with the maximum temperature set not to exceed 320 °C. The electrical heating power is adjusted based on temperature control. When the temperature between the injector and producer reaches 140 °C, turn off the producer heater, retain only the injector heater, and start injecting steam into the injector at 220 °C. (7) Set the model outlet back pressure at 2 MPa to ensure the steam chamber operating pressure reaches 2–2.5 MPa. Conduct continuous steam injection, continuous electrical heating, and continuous production. (8) After the steam chamber rises to the top of the oil layer, switch to injecting pure LPG solvent. Rely on the electrical heating and the pre-existing temperature field from steam injection to vaporize the injected solvent, creating a solvent chamber. (9) After injecting the predetermined amount of solvent, stop the solvent injection. (10) Continue the production with steam injection. In this stage, stop electrical heating, rely on steam heat and the preheated model to maintain production. Use the back-pressure valve to control the production fluid rate, ensuring a produced/injected ratio between 1.1 and 1.2. (11) Handle the produced fluids and gases. During the solvent injection stage, to prevent the escape of flammable and explosive solvents, use a fully enclosed process. Use a gas–liquid separator at the outlet to separate the produced solvent gas, measure it with a wet gas flow meter, and combust it remotely. For produced liquids, use a digital balance for real-time weighing, and after oil–water separation, measure and analyze the samples. For the produced crude oil, conduct a full hydrocarbon chromatography and SARA analysis to reveal the mechanism of solvent extraction on the physicochemical properties of the crude oil.

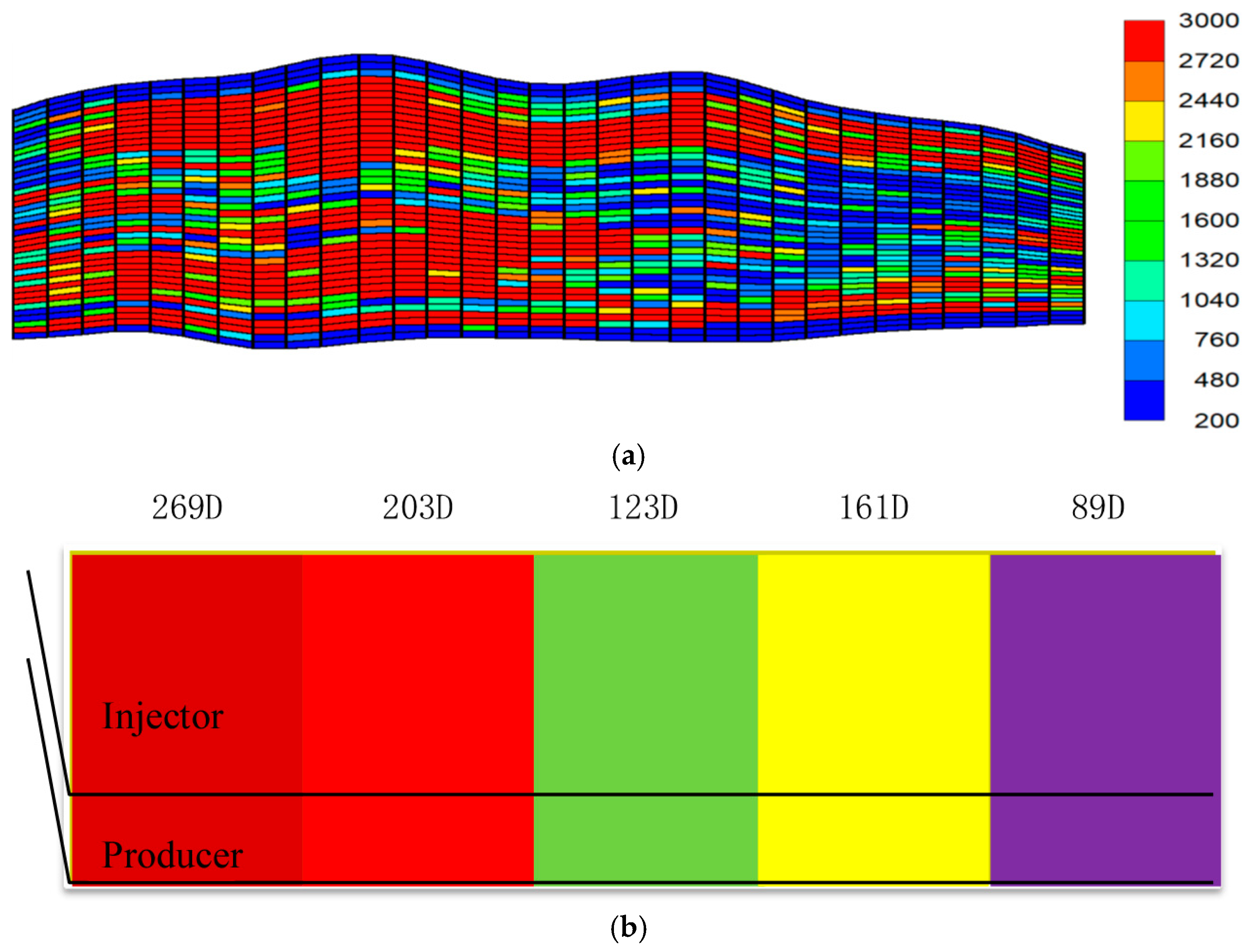

Among these, to represent the actual continental heterogeneous depositional environment of SAGD reservoirs, heterogeneous sand packing was used. Specifically, based on the common characteristic in SAGD development areas of better sweep near the heel and poorer sweep near the toe (see

Figure 7), and combined with the actual permeability profile of the oil layer in the electrical heating test area, heterogeneous sand packing along the horizontal section was performed to match the reservoir heterogeneity. The permeability contrast along the horizontal section is 269/89 = 3.02, consistent with reality.

4.3. Experimental Program Design

Given that domestic SAGD sites involve well pairs already in production, an experimental program of SAGD—Electrical Heating Solvent Extraction—SAGD was designed to clarify the composite mechanism of electrical heating and solvent, and to demonstrate the technical feasibility of a zero-carbon production method without steam injection during the mid-term of SAGD. Accordingly, the experimental program is divided into three stages, as follows:

- (1)

First, during the steam chamber rise stage, conduct conventional SAGD to establish the initial thermal field in the reservoir and create an initial steam chamber via steam.

- (2)

Transition stage to electrical heating solvent extraction. This stage occurs after the steam chamber has reached the top and begun lateral expansion. Production relies on multiple mechanisms including solvent viscosity reduction, solvent vaporization via electrical heating, extraction and upgrading, and gravity drainage.

- (3)

Transition back to conventional SAGD until production ends. Considering the flammable and explosive nature of solvents, and the fact that solvent gas channeling can be more severe than steam during the late production decline stage, posing greater safety risks, solvent is injected only during the steam chamber expansion stage. Afterwards, switch back to conventional SAGD. By measuring changes in temperature field, production rate, etc., clarify the long-term mechanism of the solvent’s effect on the subsequent SAGD stage.

During the experiment, using enclosed separation and wet gas flow meters, the produced gas and liquid are automatically separated, and the produced solvent gas is accurately measured to calculate the solvent-to-oil ratio and the solvent recovery factor.

5. Analysis of Experimental Results

5.1. Steam Chamber Expansion Characteristics in Heterogeneous Reservoir

5.1.1. Conventional SAGD Stage

During the SAGD steam chamber rise stage, given the permeability heterogeneity of the SAGD horizontal section reservoir (permeability near the heel is three times that near the toe), the steam chamber primarily develops near the heel of the horizontal section, with poorer development towards the toe. From the temperature field (see

Figure 8), the temperature in the well-developed steam chamber section reaches above 200 °C, while in sections with poorer development and near the toe, the temperature is 160–180 °C.

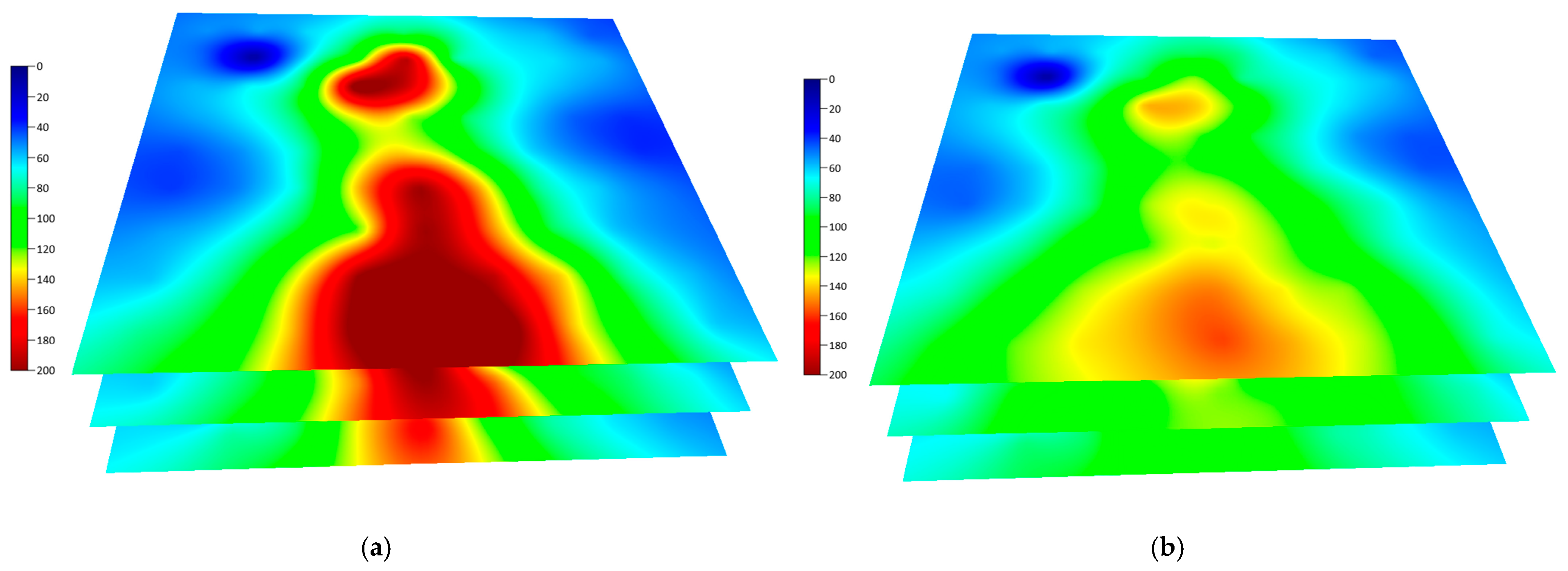

5.1.2. Comparison of Temperature Field Before and After Solvent Extraction

There are two main differences in the temperature field before and after solvent injection (see

Figure 9):

(1) The steam chamber temperature field decreases significantly, dropping noticeably from above 200 °C for steam to around 150 °C, presenting a truly ‘green’ steam chamber. (2) In terms of expansion morphology, continuous electrical heating at the injection well, combined with the pre-existing thermal field from prior pure steam SAGD, enables in situ vaporization and override of the injected solvent, promoting continuous expansion of the solvent vapor chamber [

19,

20]. For SAGD field operations, this proves that the solvent can completely replace steam for zero-carbon oil production during the SAGD steam chamber expansion stage.

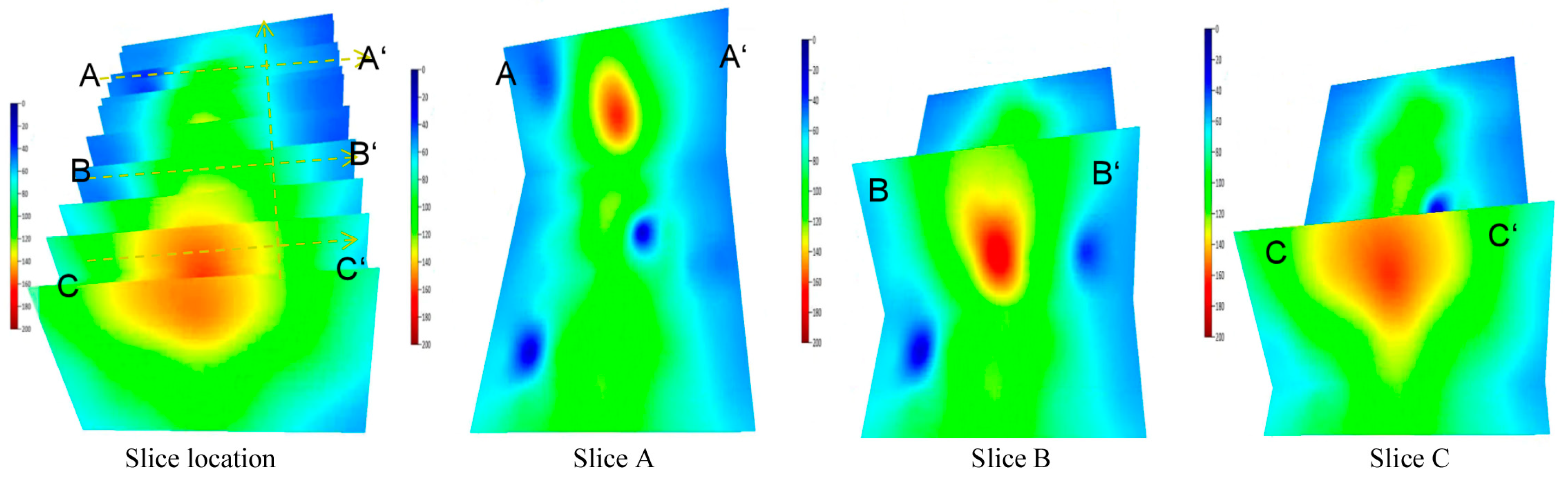

5.1.3. Zoned Drainage Characteristics in Solvent Extraction Stage

During the solvent extraction stage, influenced by the volume of the pre-existing SAGD steam chamber, the development of the solvent chamber varies significantly along the horizontal section. The solvent chamber near the heel has expanded to the reservoir edge, the chamber in the middle section has expanded to the middle of the reservoir, while the chamber near the toe has just begun to expand.

From the temperature zones shown in

Figure 10, it can be seen that during the solvent extraction stage, the drainage zone along the flanks of the horizontal section is divided into three intervals: the high-temperature zone of vaporized solvent from electrical heating, the medium-low temperature oil dissolution zone from the solvent, and the untouched zone. Along the horizontal section, it can be divided into three intervals: the solvent chamber rising zone, the slow expansion zone, and the rapid expansion zone. Relying on molecular diffusion and mass transfer, the solvent enables gravity drainage production [

21,

22].

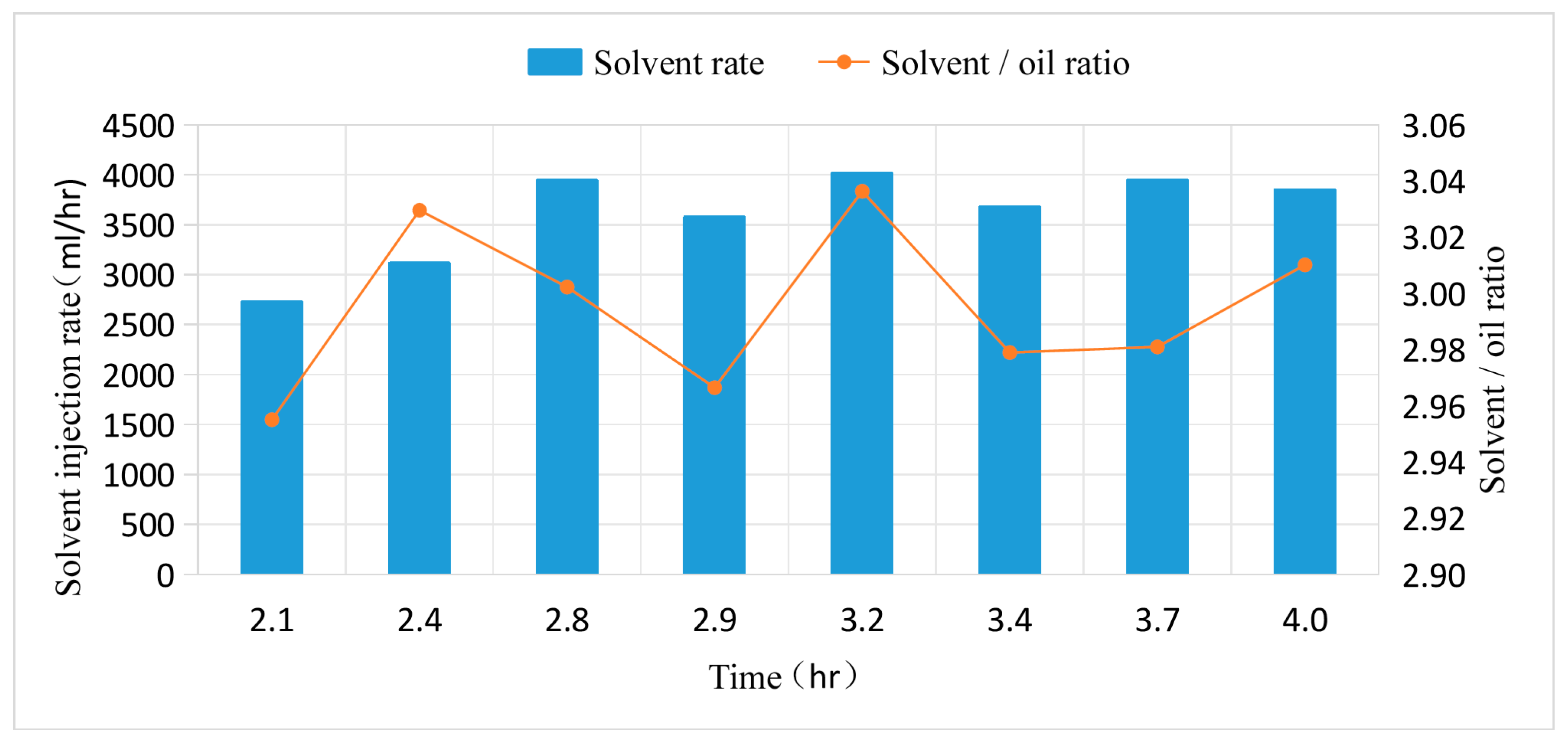

5.2. Comparison of Production Performance Characteristics

A comparison of oil production rates before and after solvent extraction in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 indicates that after injecting the solvent slug, the oil production rate increased from 1017 g/h to 1213 g/h, an increase of 25.1%. Furthermore, after stopping the solvent injection and switching back to conventional steam SAGD, the production rate remained, on average, 5.2% higher than conventional SAGD. This shows that the solvent stranded in the steam chamber continues to improve the rheological properties of the crude oil during the subsequent SAGD stage. Considering the mechanisms of high-temperature solvent displacement improving sweep efficiency and significantly increasing movable oil saturation by reducing residual oil saturation, the production history of the SAGD—Solvent Extraction—SAGD process was matched based on the above mechanisms, achieving a match rate of 95.3%. Compared with calculations from Butler’s conventional SAGD theory formula [

23], the recovery factor increased from 64.4% to 71.2%, an improvement of 6.9%. This indicates that switching from SAGD to electrical heating solvent extraction can increase the production rate and recovery factor.

5.3. Comparison of Physicochemical Properties of Produced Crude Oil

A comparison of full hydrocarbon chromatography of crude oil produced before and after electrical heating solvent extraction in

Figure 13 shows that for crude oil produced by conventional SAGD before solvent extraction, light components are mainly concentrated in the C20–C26 range. After electrical heating solvent extraction, the produced crude oil shows a significant increase in light hydrocarbon components in the C7–C15 range, indicating that electrical heating triggered a lightening reaction in the crude oil, generating light components. Given that the electrical heater surface temperature was set to 300 °C, it is analyzed that the light components result from significant hydrothermal reactions between the oil and residual water steam from prior injection under high temperature.

To further identify the cause of the light component generation, elemental analysis was conducted on crude oil before and after electrical heating solvent extraction. The comparison in

Table 2 shows that the H/C atomic ratio in the produced crude oil increased from 1.3 for conventional SAGD to 1.62–2.09 during the solvent extraction stage, indicating significant hydrogenation reactions. Meanwhile, the S content in the crude oil decreased from 0.85% to 0.32–0.75%, showing significant desulfurization reactions. These hydrogenation and desulfurization reactions conform to the typical characteristics of hydrothermal reactions.

SARA analysis in

Figure 14 was conducted on the crude oil before and after solvent extraction. The results show that under the hydrothermal reactions induced by high-temperature electrical heating, the saturate content of the crude oil increased, and the asphaltene content decreased from 6.9 wt% to 2.3–4.15 wt%. This indicates the coexistence of hydrogenation and bond scission reactions, with high temperature providing the key activation energy for the hydrothermal reactions [

24,

25].

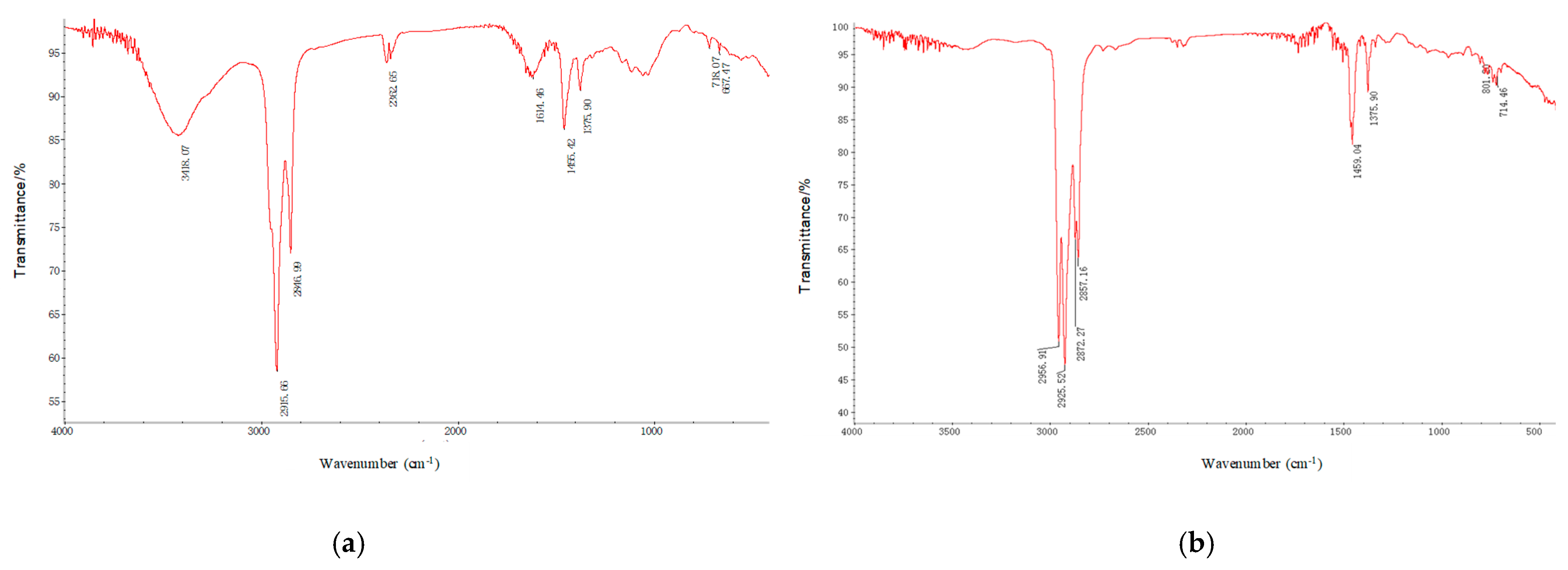

Figure 15 shows the FTIR spectra comparison of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages. From

Figure 15, a comparison of functional groups in the produced crude oil before and after solvent extraction shows that after solvent extraction, the characteristic peaks for methyl, methylene, and long-chain hydrocarbons become broader and stronger at their respective positions. This indicates an increase in methyl/methylene saturates and long-chain hydrocarbons in the extracted oil, another important characteristic of deasphalting and upgrading via solvent extraction.

6. Solvent Evaporation Control and Disposal

Precision Control of the Injection Process: During the solvent slug injection phase, the key objective is to maintain the solvent in liquid state and prevent premature vaporization. A fully enclosed high-pressure injection system must be employed, with precise control of injection pressure to ensure it consistently exceeds the saturation vapor pressure of the solvent at the prevailing wellbore temperature. Additionally, highly sensitive combustible gas detectors should be installed at the wellhead and pump areas to enable real-time leakage monitoring. An interlocked shutdown procedure must be implemented to automatically terminate injection upon anomaly detection, thereby mitigating risks at the source.

Closed-Loop Handling of Return Fluids: The production return phase following the injection represents a critical period for risk management. Fluids returning to the surface along with crude oil are immediately directed into a closed three-phase separation system. The separated solvent-rich gas is not vented but instead channeled to a vapor recovery unit, where it is compressed and cooled for re-liquefaction into product solvent, enabling recycling and risk elimination. If the gas volume exceeds processing capacity, the system automatically diverts surplus gas to a flare stack in a safe area for complete combustion, thereby converting combustible hazards into controlled combustion reactions.

Systematic Barriers and Emergency Preparedness: To establish a defense-in-depth framework, wellbore integrity must be rigorously ensured, with both downhole and surface safety valves capable of reliable closure in emergencies. All electrical equipment installed in hazardous areas shall adopt the highest level of explosion-proof design to thoroughly eliminate potential ignition sources. Furthermore, detailed emergency response plans should be developed, specifying leakage handling procedures, personnel evacuation routes, and on-site rescue measures—ultimately forming a comprehensive safety protection system spanning from downhole to surface, and from prevention to response.

7. Conclusions

Experimental Validation and Decision Basis: Electrical heating experiments confirmed that a higher oil saturation in the wellbore and near-wellbore regions leads to faster heat transfer rates. This critical finding validates the decision to conduct electrically-assisted solvent extraction (without steam injection) in SAGD-developed reservoirs for performance evaluation.

Technical Strategy and Model Establishment: In response to safety concerns in domestic SAGD blocks and solvent extraction operations, a phased development strategy of “SAGD—Electrical Heating Solvent Extraction—SAGD” was formulated. Accordingly, a multi-stage coupled drainage theoretical model was established, achieving a 95.3% consistency between production predictions and experimental/analytical solutions, demonstrating high reliability.

Physical Simulation and Drainage Zoning: The similarity coefficients for 3D physical modeling of electrical heating were revised, enabling a precise similarity parameter design. Based on the temperature field analysis, drainage zones in heterogeneous reservoirs were identified: along the lateral direction of the horizontal section, the regions include the solvent-vaporized high-temperature zone, solvent-gas mixed zone, and unutilized zone; along the horizontal section, the zones consist of the solvent chamber rising region, slow expansion region, and rapid expansion region.

Development Performance and Synergistic Mechanism: Experiments revealed that after switching from SAGD to electrically-assisted solvent extraction, the solvent continuously vaporizes to expand the drainage chamber, remaining effective long-term upon SAGD resumption, ultimately increasing recovery from 64.4% to 71.2%. Under high-temperature electrical heating, the residual steam in SAGD significantly reacts with heavy oil through hydrothermal reactions (hydrogenation, desulfurization), reducing asphaltene content, increasing the hydrogen-to-carbon ratio, and upgrading the oil quality. This unveils a synergistic mechanism between electrical heating and solvent extraction.

Author Contributions

X.S.: Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Funding; Y.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—review and editing; W.H.: Investigation, Resources; J.Z.: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft; C.L.: Supervision, Project administration; C.W.: Conceptualization, Investigation; S.L.: Supervision; Q.W.: Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2024YFF0506503, the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number U22B6004, and the Technology Project of China National Petroleum Corporation, grant number 2023ZZ04-03.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xinge Sun, Wanjun He, Chihui Luo, Shan Liang, Qing Wang were employed by the company Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, Xinjiang Oilfield Company, PetroChina. Authors Yongbin Wu, Chao Wang were employed by the company Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, PetroChina. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| q | Oil production rate, m3/d; |

| L | Length of horizontal well section, m; |

| K | Absolute permeability, m2; |

| g | Gravitational acceleration, 7.323126 × 1010 m2/d |

| a | Thermal diffusivity, m2/d; |

| m | Viscosity-temperature curve exponent, dimensionless; |

| φ | Porosity, %; |

| t | Time, d; |

| ΔSo | Movable oil saturation, %; |

| vmix | Kinematic viscosity of solvent-oil mixture, m2/d; |

| vs | Kinematic viscosity of solvent-oil mixture at electrical heating temperature, m2/d; |

| Ns | Intermediate variable; |

| cs | Concentration of solvent in crude oil considering electrical heating temperature rise, %; |

| cmin | Minimum concentration of solvent in flowing oil, %; |

| cmax | Maximum concentration of solvent in flowing oil considering electrical heating temperature rise, %; |

| Δρ | Density difference between solvent and oil, g/cm3; |

| D | Molecular diffusion coefficient of solvent into oil considering electrical heating temperature rise, m2/s; |

| B3,B3′ | Similarity coefficient, dimensionless; |

| w | Width of model or prototype reservoir, m; |

| T | Electrical heating operating temperature, °C. |

References

- Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Luo, S. Research and Prospects on Efficient and Low-Carbon Development Technology for Shallow Ultra-Heavy Oil SAGD in Xinjiang Oilfield. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2024, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, Y. Scaled Physical Simulation Experiment on Solvent Assisted Gravity Drainage for Ultra-Heavy Oil Reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, S.; Salem, K.G.; El-hoshoudy, A.N. Enhanced heavy and extra heavy oil recovery: Current status and new trends. Petroleum 2023, 10, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H.; Nagabandi, N.; Temizel, C.; Jamal, D. Heavy Oil Reservoir Management—Latest Technologies and Workflows. In Proceedings of the SPE Western Regional Meeting, Bakersfield, CA, USA, 26–28 April 2022. SPE-209328-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.; Liu, T.; Xie, J.; Rong, G.; Yang, L. A review of SAGD technology development and its possible application potential on thin-layer super-heavy oil reservoirs. Geosci. Front. 2022, 13, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, H.; Rabiei Faradonbeh, M.; Harding, T. Numerical simulation of solvent and water assisted electrical heating of oil sands including aquathermolysis and thermal cracking reactions. AIChE J. 2017, 63, 4243–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azom, P.; Ben-Zvi, A. Optimal Degree of Upgrading from Solvent Processes. In Proceedings of the SPE Canadian Energy Technology Conference and Exhibition, Calgary, AB, Canada, 13–15 June 2023. SPE-212763-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Bayestehparvin, B.; Farouq Ali, S.M. Nonequilibrium Phase Behavior Plays a Role in Solvent-Aided Processes. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 3–5 October 2022. SPE-210016-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, A.; Boustani, A.; Hassanzadeh, H. Optimization of the Operating Envelope of a Hot-Solvent Injection Process for Bitumen Recovery. SPE J. 2022, 27, 2268–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, K.; Okuno, R.; Al-Gawfi, A.; Nakutnyy, P.; Imran, M.; Nakagawa, K. An Experimental Study of Steam-Solvent Coinjection for Bitumen Recovery Using a Large-Scale Physical Model. SPE J. 2022, 27, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Sabet, N.; Bashiani, F. Horizontal producers deliverability in SAGD and solvent aided-SAGD processes: Pure and partial solvent injection. Fuel 2021, 294, 120363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, D.; Diao, B.; Tan, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, K. Comparative performance of electric heater vs. RF heating for heavy oil recovery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 160, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Taleghani, A.D. Numerical study on non-Newtonian Bingham fluid flow in development of heavy oil reservoirs using radiofrequency heating method. Energy 2022, 239, 122385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, A.; Bhadauriya, D.S.; Sharma, R.; Deka, B. Recovery of heavy crude oil with electrical enhanced oil recovery using lignin nanoparticles: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 99, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motahhari, H.R.; Khaledi, R. General Analytical Model for Thermal-Solvent Assisted Gravity Drainage Recovery Processes. In Proceedings of the SPE Canada Heavy Oil Technical Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 13–14 March 2018. SPE-189754-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.M. Thermal Recovery of Oil and Bitumen; Prentice Hall Publishing Company: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lifan, P. Prediction of SAGD Production of Ultra-Heavy Oil in Xinjiang F-Oilfield; Southwest Petroleum University: Chengdu, China, 2014; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam, S.; Nobakht, M.; Gu, Y. Theoretical and physical modeling of a solvent vapour extraction (VAPEX) process for heavy oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2009, 65, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yu, G.; She, Y.; Gu, Y. A parabolic solvent chamber model for simulating the solvent vapor extraction (VAPEX) heavy oil recovery process. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 149, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jia, X.; Chen, Z. Mathematical modeling of the solvent chamber evolution in a vapor extraction heavy oil recovery process. Fuel 2016, 186, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gawfi, A.; Nourozieh, H.; Ranjbar, E.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Abedi, J. Mechanistic modelling of non-equilibrium interphase mass transfer during solvent-aided thermal recovery processes of bitumen and heavy oil. Fuel 2019, 241, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Z. Transient mass transfer ahead of a hot solvent chamber in a heavy oil gravity drainage process. Fuel 2018, 232, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Berg, S.; Castellanos-Diaz, O.; Wiegmann, A.; Verlaan, M. Solvent-dependent recovery characteristic and asphaltene deposition during solvent extraction of heavy oil. Fuel 2020, 263, 116716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Kim, M.Y.; Im, S.I.; Go, K.S.; Nho, N.S.; Lee, K.B. Development of correlations between deasphalted oil yield and Hansen solubility parameters of heavy oil SARA fractions for solvent deasphalting extraction. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 107, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhametshina, A.; Kar, T.; Hascakir, B. Asphaltene precipitation during bitumen extraction with expanding-solvent steam-assisted gravity drainage: Effects on pore-scale displacement. SPE J. 2016, 21, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A 3D radial sand-packed model with an electric heating rod in the center.

Figure 1.

A 3D radial sand-packed model with an electric heating rod in the center.

Figure 2.

The comparison curves of the temperature rise at the edge measurement point for different wellbore fluids.

Figure 2.

The comparison curves of the temperature rise at the edge measurement point for different wellbore fluids.

Figure 3.

The comparison curves of the temperature rise near the electrical heater for different wellbore fluids.

Figure 3.

The comparison curves of the temperature rise near the electrical heater for different wellbore fluids.

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram of the electrical heating 3D-scaled physical simulation experimental apparatus.

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram of the electrical heating 3D-scaled physical simulation experimental apparatus.

Figure 5.

A schematic diagram of the internal layout of heaters, temperature measurement points, and wells in the model body. (a) Top view of the model ontology; (b) Side view of the model ontology.

Figure 5.

A schematic diagram of the internal layout of heaters, temperature measurement points, and wells in the model body. (a) Top view of the model ontology; (b) Side view of the model ontology.

Figure 6.

Change in oil viscosity at different temperatures.

Figure 6.

Change in oil viscosity at different temperatures.

Figure 7.

The design of the heterogeneous reservoir sand packing scheme. (a) Horizontal section permeability profile; (b) Non-uniform sand filling in the horizontal section.

Figure 7.

The design of the heterogeneous reservoir sand packing scheme. (a) Horizontal section permeability profile; (b) Non-uniform sand filling in the horizontal section.

Figure 8.

The steam chamber development profile in the heterogeneous reservoir during SAGD.

Figure 8.

The steam chamber development profile in the heterogeneous reservoir during SAGD.

Figure 9.

Comparison of steam/solvent chamber temperature fields during SAGD and solvent extraction stages. (a) Steam injection stage; (b) Solvent injection stage.

Figure 9.

Comparison of steam/solvent chamber temperature fields during SAGD and solvent extraction stages. (a) Steam injection stage; (b) Solvent injection stage.

Figure 10.

Drainage interface characteristics of the solvent chamber for different solvent systems.

Figure 10.

Drainage interface characteristics of the solvent chamber for different solvent systems.

Figure 11.

Comparison of oil production rates between SAGD and solvent extraction.

Figure 11.

Comparison of oil production rates between SAGD and solvent extraction.

Figure 12.

Comparison of solvent injection rates and solvent-oil ratios between SAGD and solvent extraction.

Figure 12.

Comparison of solvent injection rates and solvent-oil ratios between SAGD and solvent extraction.

Figure 13.

Comparison of full hydrocarbon components of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages.

Figure 13.

Comparison of full hydrocarbon components of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages.

Figure 14.

Comparison of asphaltene content in produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages.

Figure 14.

Comparison of asphaltene content in produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra comparison of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages. (a) Crude oil is produced before solvent extraction; (b) Crude oil is produced in the solvent extraction stage. Note: Peaks at 2956 cm−1, 2857 cm−1 correspond to C-H stretching vibrations of methyl and methylene groups; peaks at 1459 cm−1, 1375 cm−1 correspond to bending vibrations of methyl and methylene groups; peak at 722 cm−1 is characteristic of long-chain hydrocarbons.

Figure 15.

FTIR spectra comparison of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages. (a) Crude oil is produced before solvent extraction; (b) Crude oil is produced in the solvent extraction stage. Note: Peaks at 2956 cm−1, 2857 cm−1 correspond to C-H stretching vibrations of methyl and methylene groups; peaks at 1459 cm−1, 1375 cm−1 correspond to bending vibrations of methyl and methylene groups; peak at 722 cm−1 is characteristic of long-chain hydrocarbons.

Table 1.

Scaling results of key parameters for physical simulation.

Table 1.

Scaling results of key parameters for physical simulation.

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Model Value | Reservoir Value |

|---|

| Porosity | φ | / | 0.35 | 0.3 |

| Oil saturation | ΔSo | / | 0.88 | 0.69 |

| Average permeability | K | μm2 | 169 | 1.69 |

| Reservoir thickness | h | m | 0.2 | 25 |

| Well spacing | w | m | 0.4 | 70 |

| Electric heating temperature | T | °C | 150–220 | 100–220 |

| Similarity coefficient | B3′ | / | 5.53 | 5.53 |

Table 2.

Comparison of elemental content of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages.

Table 2.

Comparison of elemental content of produced oil during SAGD and solvent extraction stages.

| Number | N | C | H | S | O | H/C |

|---|

| Conventional SAGD | 1.35 | 86.12 | 9.35 | 0.75 | 2.43 | 1.30 |

| Solvent Extraction 1# (Initial extraction stage) | 0.78 | 82.08 | 11.09 | 0.85 | 5.19 | 1.62 |

| Solvent Extraction 2#(Mid-term extraction) | 0.66 | 61.42 | 10.67 | 0.32 | 26.93 | 2.09 |

| Solvent Extraction 3#(At the end of extraction) | 0.54 | 80.46 | 11.81 | 0.56 | 6.62 | 1.76 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).