Study on the Synergistic Effect of Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits in Chamber-Type Mining of Steeply Inclined Coal Seams

Abstract

1. Introduction

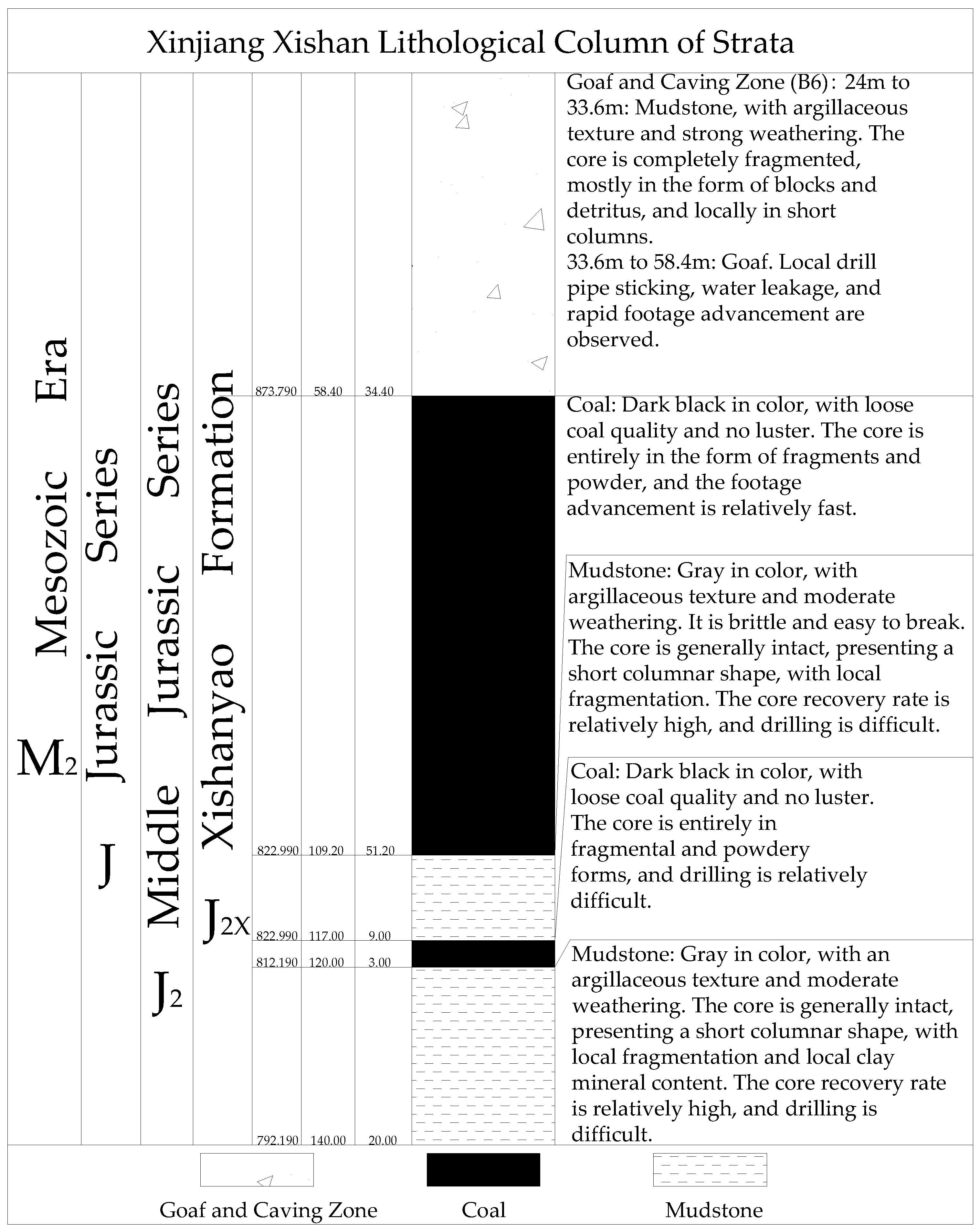

2. Geological Conditions

3. Synergistic Mechanism Between Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits

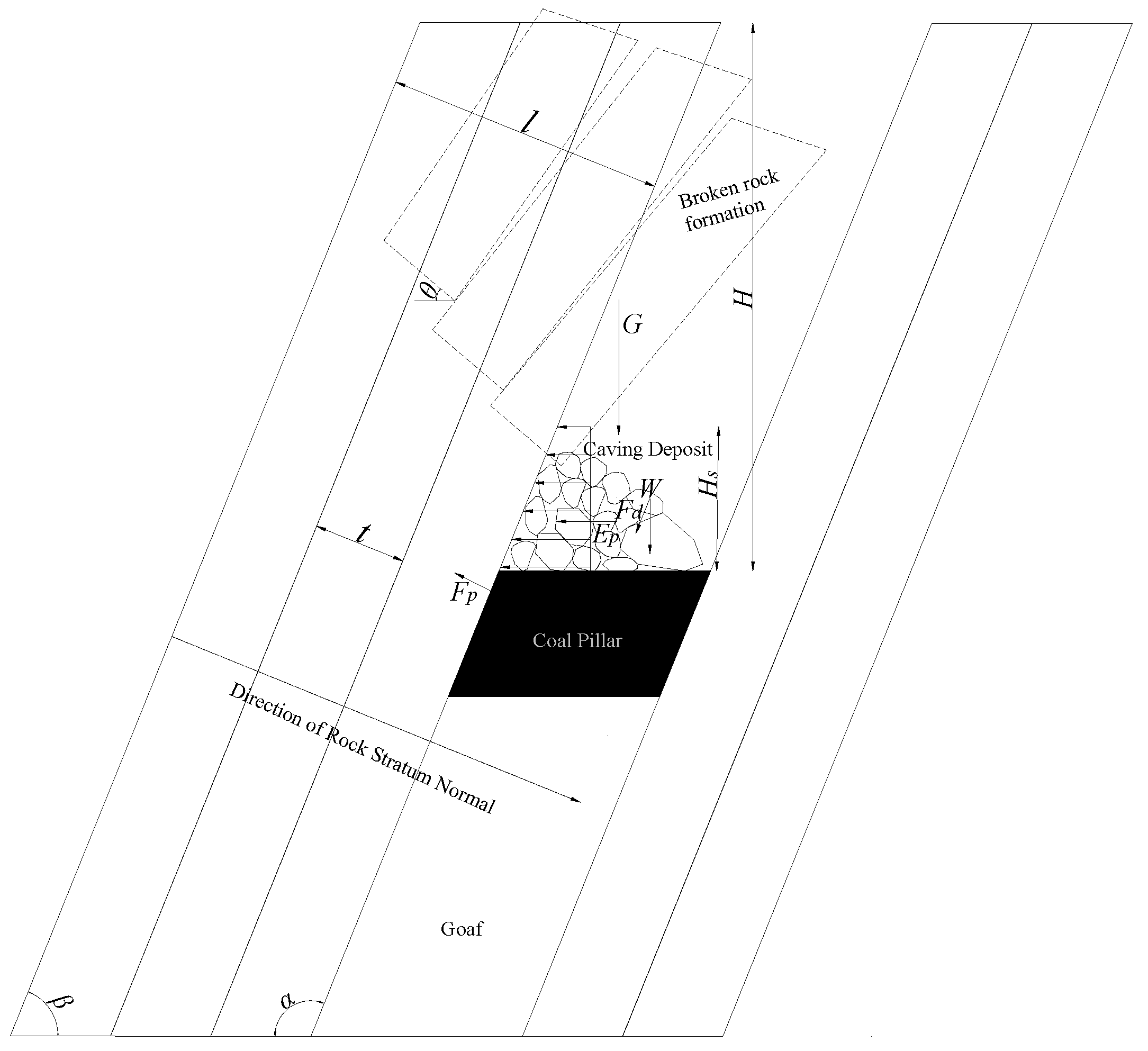

3.1. Mechanical Analysis of Synergistic Action Between Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits

3.2. Anti-Dip Failure Mode of Roof Mudstone

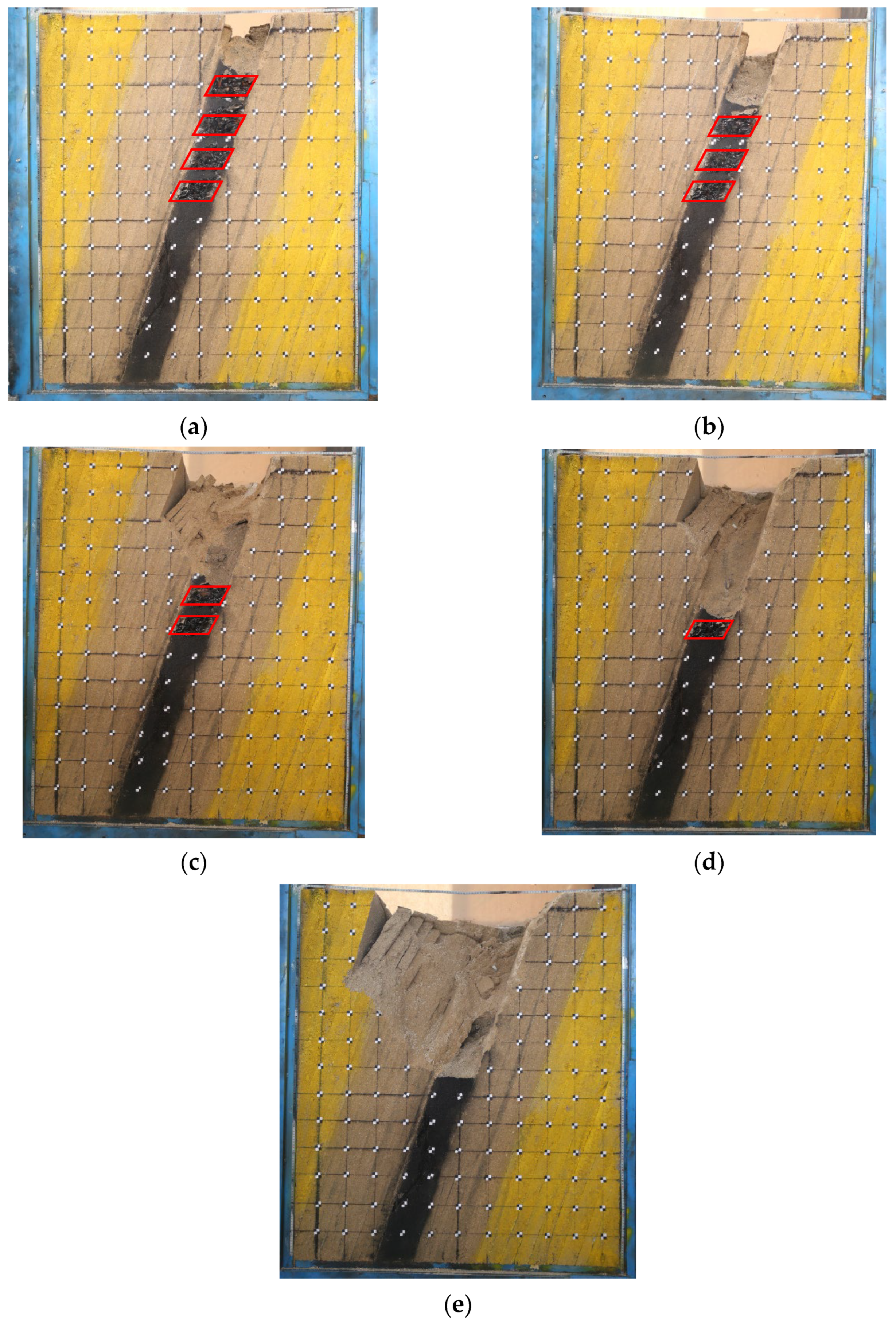

4. Physical Simulation of Synergistic Action Between Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits

4.1. Construction of Physical Similarity Model

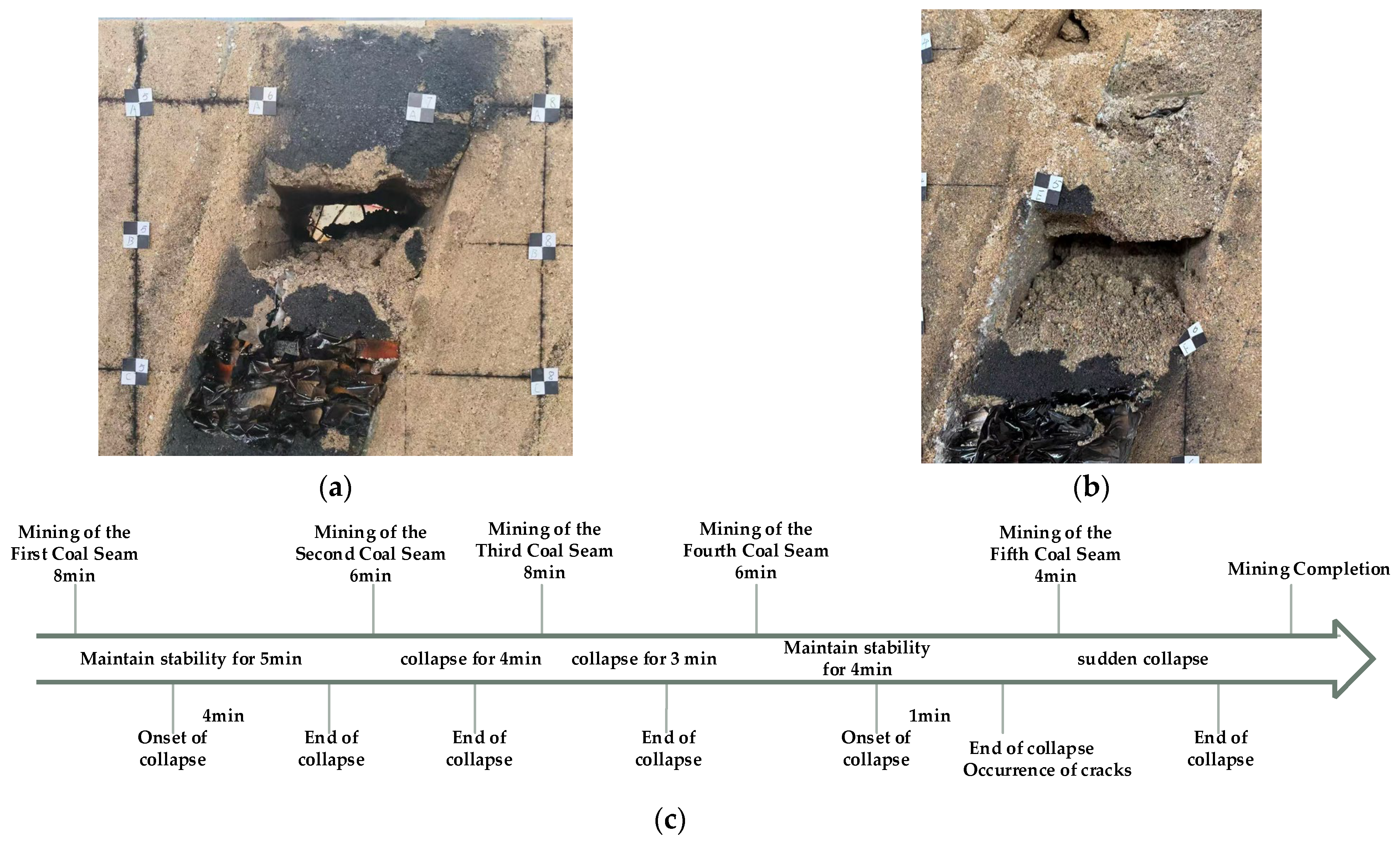

4.2. Coal Seam Mining Process and Monitoring

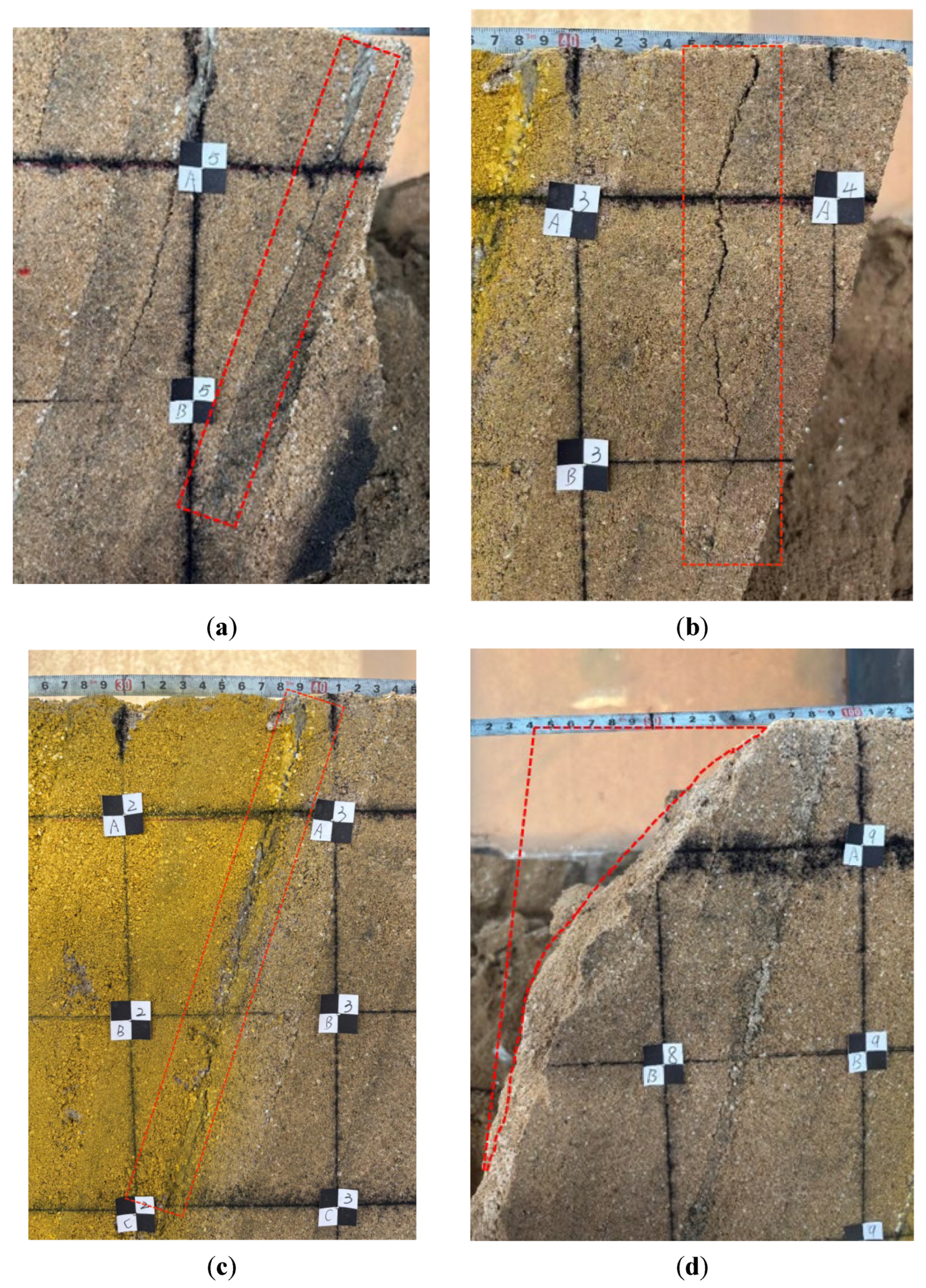

4.2.1. Sequential Characteristics of Coal Seam Mining and Collapse

4.2.2. Quantitative Analysis of Surrounding Rock Response and Stress in Coal Seam Mining

5. Result

5.1. Summary of Model Experiment Results

5.2. Comparison and Verification of Model Experimental Results with Theoretical Predictions

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The proposed mechanical mechanism model of the “synergistic action between coal pillars and caved deposits” reveals that during the near-vertical chamber mining process, the dynamic evolution of the void ratio of the caved deposits directly affects the support performance, and clarifies that the compaction lag and inhomogeneity of the caved deposits are the key factors controlling the instability sequence, thereby regulating the overall stability of the goaf.

- (2)

- The toppling-sliding composite failure theory of anti-dip slopes can be applied to the instability analysis of the roof of near-vertical goafs. By integrating the support force of coal pillars and the lateral support force of caved deposits into a unified mechanical equilibrium system, the safety coefficient Ks for goaf stability under the synergistic action of coal pillars and caved deposits is constructed, which provides a new method for the quantitative prediction of the stability state of goafs.

- (3)

- Through the comparative verification between the similar simulation experiment and the theoretical analysis, it is confirmed that the proposed synergistic action model can more accurately reflect the stable state compared with the traditional model that only considers coal pillars. Quantitative analysis shows that the lateral support force generated by the caved deposits can increase the calculation result of the overall safety coefficient by more than 15%, and the support effect is most significant in the compacted area of the middle and lower parts of the goaf. This result provides a key basis for the accurate prediction of disaster risks.

- (4)

- The “structure-medium” synergistic analysis framework proposed in this study can be extended to the stability evaluation of goafs under the mining conditions of other large-dip-angle and steeply inclined coal seams, providing a new theory and engineering reference for the prevention and control of mine dynamic disasters.

- (5)

- This method boasts high application feasibility in practical engineering. From the perspective of data acquisition, all parameters required by the model can be obtained through conventional methods; from the perspective of engineering adaptability, it can be directly embedded into the existing mine goaf stability evaluation process, enabling graded assessment of goaf stability status via quantitative calculation of the safety factor Ks; from the perspective of expected engineering effects, the method can accurately identify the key stages of goaf instability (local shear failure, bending-shear composite failure, toppling-sliding dynamic instability). Based on this, coal pillar layout parameters and goaf caved material control measures are optimized, and it is expected to reduce the roof collapse accident rate of goafs in near-vertical coal seams by more than 20%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Parameters | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Kf | Criterion for toppling failure |

| W | Dangerous rock mass |

| αc | Inclination angle of contact surface |

| h0 | Vertical distance from center of gravity to overturning point |

| σmax | Maximum tensile stress |

| Pi−1 | Limit equilibrium of bending-toppling failure |

| Qi−1 | Limit equilibrium of shear failure |

| Fp | Ultimate strength of coal pillar |

| σp | Support force of roof |

| psh | Lateral pressure of accumulated mass |

| Hs | Height of accumulated material in goaf |

| Fb | Total lateral support of accumulated material |

| Fd | Component sliding force |

| Fs | Intrinsic shear strength of sliding surface |

| Fr | Total anti-sliding force |

| V | Water pressure in trailing edge fissures |

| Kc | Shape correction coefficient |

| σc | Average compressive strength of coal pillars |

| B | Coal pillar width |

| Hp | Coal pillar height |

| Ap | Empirical coefficient, with a value of 0.5 |

| Kp | Passive earth pressure coefficient |

| ηd | Particle size similarity deviation coefficient |

| dp,avg | Prototype average particle size |

| dm,avg | Model average particle size |

| φ0, c0 | Fine particle reference value |

References

- Liu, Y.X. Comprehensive Evaluation of Stability of Residual Coal-pillar after Room-and-pillar Mining. Coal Min. Technol. 2013, 18, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.B.; Deng, K.Z.; Zhang, L.Y. Research on Coal Pillar Stability of Room and Pillar Goaf. Saf. Coal Mines 2011, 42, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Miao, X.X.; Zhang, X.C. Analysis of the Time-dependence of the Coal Pillar Stability. J. China Coal Soc. 2005, 30, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Yang, J.; Ma, Z.G.; Mao, X. Research on Long-term Stability of Coal Pillar Group in Strip Mining of Inclined Coal Seam. Saf. Coal Mines 2024, 55, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L. Study on the Mechanism of Rock Strata Failure and the Theory of Surface Movement in Steeply Inclined Coal Seam Mining. Ph.D. Thesis, China Coal Research Institute, Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.C. The Analysis of Stability and Treatment to the Goaf of Steeply Seam in No.2 Eastern Ring Freeway around Urumqi City. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Science and Technology Shaanxi, Xi’an, China, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.S. Overlying Strata Movement Law and Control Mechanism of Fully Mechanised Longwall Mining Face in Thin and Medium Thickness Steeply Inclined Coal Seam. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Hao, B.Y.; Ren, X.Y. Investigating Coal Pillar Size in District Sublevel and Regional Surrounding Rock Controlling in Inclined Extra-thick Coal Seam. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2024, 41, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.W. Stability of roof structure and its control in steeply inclined coal seams. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L. Study on Creep Failure Mechanism and Stability Evaluation of Strip Coal Pillar under Water Immersion Condition. Ph.D. Thesis, China Coal Research Institute, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.P.; Huangfu, J.Y.; Xie, P.S.; Hu, B.S.; Liu, K.Z. Research on Laws of Stope Inclined Support Pressure Distribution with Large Dip Angle and Large Mining Height. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 3062–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Gu, S.; Ding, M. Mechanism and Prevention of Rock Burst in a Wide Coal Pillar under the Superposition of Dynamic and Static Loads. Processes 2024, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Kong, X.Y.; Lu, W.; Liu, S. Study of Strata Pressure Behaviors with Longwall Mining in Large Inclination and Thick Coal Seam under Close Distance Mined Gob. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2015, 34, 4278–4285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.L.; Yang, K.; Fu, Q.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Z.N. Study on Stress Distribution Law of Regenerated Roof in Fully-mechanized Layered Mining of Steeply Dipping Coal Seam. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2022, 39, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M.; Peng, X.P.; Yao, Y.P.; Xu, J.H. Application of SMP Failure Criterion to Computing Limit Strength of Coal Pillars. Rock Soil Mech. 2010, 31, 2987–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.S.; Tu, S.H.; Zhu, D.F.; Hao, D.Y.; Miao, K.J. Force-Fracture Characteristics of the Roof above Goaf in a Steep Coal Seam: A Case Study of Xintie Coal Mine. Geofluids 2019, 2019, 7639159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tu, S.H.; Tu, H.S.; Tang, L.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Miao, K.; Tian, H. Numerical Simulation Study on Stability Control Technology of Large-Area Wall Caving Area (LAWCA) in Large-Inclined Face. Geofluids 2023, 2023, 5352974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.D.; Hu, G.Z.; Zhao, G.C. Research on the Movement Law of Roof Structure in Large-Inclined Coal Seam Working Face: A Case Study in Liupanshui Mining Area. Shock. Vib. 2022, 2022, 6328851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.L.; Gao, X.G.; Li, S.S. Residual Void Ratio of Knife Pillar Mining Goaf under a New Substation Site in Majiliang Mine. Coal Eng. 2023, 55, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.F.; Chi, D.X.; Tian, S.G.; Ding, Y.P.; Chang, J.C. Similarity Model Test of Subway Line Passing Steeply Inclined Mined-out Subsidence Area. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2018, 18, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C. Modeling test-based study on roof cutting for pressure unloading in inclined coal seam. China Saf. Sci. J. 2019, 29, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.P.; Hu, B.S.; Lang, D.; Tang, Y.P. Risk assessment approach for rockfall hazards in steeply dipping coal seams. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 138, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.J. Study on Porosity Distribution Law of Roof Caving Zone and Goaf with Different Structures. Henan Sci. Technol. 2023, 42, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, E.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Tan, Y.; Guo, M.; Wen, P.; Ma, Z. Characteristics and Formation Mechanism of Surface Residual Deformation above Longwall Abandoned Goaf. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.Y.; Han, D.D.; Feng, G.R.; Guo, J.; Zhang, A.; Hao, G.C. The Effect of Stress Transfer on the Spatial Distribution of Void Ratios in Crushed Rock Mass. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2020, 37, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Y.; Chu, T.X.; Feng, X.W.; Dai, W.C. Fractal Model and Experimental Study on Porosity of Compacted Coal Particles. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Q.; Li, Y.S.; Yan, M. The Implication and Evaluation of Toppling Failure in Engineering Geology Practice. J. Eng. Geol. 2017, 25, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.F.; Pu, H.; Ni, H.Y.; Bian, Z.F. Research on Re-fracturing Mechanism and Cavity Structure Evolution Characteristics of Broken Rock Mass in Goaf of Closed Mine. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Q.; Tian, S. Research on prediction of residual deformation in goaf of steeply inclined extra–thick coal seam. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhu, P.R. Research on roof caving mechanism and influencing factors in inclined ore body caving mining. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zeng, Z.L.; Zhu, Y.J.; Luo, Y.F.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.C.; Liu, S.C. Study on the broken law of overlying rock in the steeply dipping medium-thick coal seam with thick and hard roofs. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.G.; Oh, J.; Si, G.Y. Fragmented rock block geometry affecting mechanical responses and fluid flow characteristics during compaction of caving zones. Powder Technol. 2026, 469, 121707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Li, G. Deformation Characteristics and Destabilization Mechanisms of the Surrounding Rock of Near-Vertical Coal-Rock Interbedded Roadway. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Qin, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, F.; Chu, X. Numerical Simulation of Deformation and Failure Mechanism of Main Inclined Shaft in Yuxi Coal Mine, China. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.X.; Zhang, H. Analytical Method for Flexural Toppling-Shear Sliding Failure of Counter-tilted Rock Slopes. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2021, 38, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.F.; Liu, Q.S.; Chen, C.X. Improvement of Cantilever Beam Limit Equilibrium Model of Counter-tilt Rock Slopes. Rock Soil Mech. 2012, 33, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.S.; Huang, B.F.; Wu, Y.P.; Luo, S.; Zhu, M.; Yi, L.; Xu, H.; Xu, H.; Chen, J. Three-dimensional Fracture Migration Evolution Law of Overburden Rock in Steeply Dipping Working Face. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; He, R.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H. Prediction of the Caved Rock Zones’ Scope Induced by Caving Mining Method. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Huang, R.Q. Stress and Flexibility Criteria of Bending and Breaking in a Countertendency Layered Slope. J. Eng. Geol. 2004, 12, 243–246, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, R.Q.; Nian, T.K. Analytical Method for Stability of Anti Dip Rock Slope Based on Flexural Toppling Failure Mode. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2019, 38, 3287–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Yang, S.L.; Li, L.H. Toppling-slumping Failure Mode in Horizontal Sublevel Top-coal Caving Face in Steeply-inclined Seam. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2018, 47, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiwaye, H.T.; Stacey, T.R. A Comparison of the Limit Equilibrium and Numerical Modelling Approaches to Risk Analysis for Open Pit Mine Slopes. J. South. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2010, 110, 571–580. [Google Scholar]

| Rock Stratum Numbering | Lithology | Model Volume /cm3 | Ratio | River Sand /kg | Gypsum /kg | CaCO3 /kg | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1 | Sandstone 1 | 2.345 × 105 | 755 | 245 | 52.5 | 52.5 | The first digit of the Formulation No. indicates the sand-to-binder ratio, while the second and third digits represent the proportion of the two types of binders in the total amount. |

| Y2 | Mudstone 1 | 1.400 × 105 | 973 | 324 | 10.8 | 25.2 | |

| Y3 | coal | 9.100 × 104 | 937 | 144 | 4.8 | 11.2 | |

| Y4 | Mudstone 2 | 2.100 × 105 | 973 | 216 | 7.2 | 16.8 | |

| Y5 | Sandstone 2 | 1.950 × 105 | 755 | 280 | 60 | 60 |

| Mechanical Parameters | Sandstone | Sandstone/Model | Mudstone | Mudstone/Model | Coal | Coal/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniaxial Tensile Strength/Mpa | 32.52 | 0.29 | 8.81 | 0.08 | 5.63 | 0.05 |

| Elastic Modulus/GPa | 4.91 | 0.04 | 1.82 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.01 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Cohesion/MPa | 5.62 | 0.05 | 2.15 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.01 |

| Monitoring Point | Mining Stage | Initial Stress/kPa | Mining Stress/kPa | Collapse Stress/kPa | Stable Stress/kPa | Recovery Duration/min | Maximum Drop/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 1st | 2.1/2235.0 | 1.3/1310.0 | 1.5/1125.0 | 1.7/1856.25 | 8/69.28 | 44.4 |

| 8 | 1st and 2nd | 6.2/2250.0 | 2.9/900.0 | 3.8/675.0 | 3.9/2081.25 | 12/103.92 | 70.0 |

| 7 | 3rd | 7.2/2475.0 | 4.2/1012.5 | 5.1/618.75 | 5.3/2250.0 | 10/86.60 | 75.0 |

| 6 | 4th | 7.4/2362.5 | 5.2/843.75 | 5.6/562.5 | 5.9/2137.5 | 9/77.94 | 76.2 |

| 5 | 5th | 9.2/2587.5 | 6.0/787.5 | 7.4/506.25 | 7.8/2306.25 | 7/60.62 | 80.4 |

| 4 | Mining Completed | 8.8/2700.0 | 6.9/731.25 | 7.7/450.0 | 7.9/2362.5 | 11/95.26 | 83.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Li, M.; Cao, W.; Song, H. Study on the Synergistic Effect of Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits in Chamber-Type Mining of Steeply Inclined Coal Seams. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413188

Chen Z, Wu S, Wang J, Shi J, Li M, Cao W, Song H. Study on the Synergistic Effect of Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits in Chamber-Type Mining of Steeply Inclined Coal Seams. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413188

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhuo, Shenglin Wu, Jilin Wang, Jibiao Shi, Mingliang Li, Wan Cao, and Hao Song. 2025. "Study on the Synergistic Effect of Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits in Chamber-Type Mining of Steeply Inclined Coal Seams" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413188

APA StyleChen, Z., Wu, S., Wang, J., Shi, J., Li, M., Cao, W., & Song, H. (2025). Study on the Synergistic Effect of Coal Pillars and Caved Deposits in Chamber-Type Mining of Steeply Inclined Coal Seams. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413188