Analysis of Passive Shielding Performance Stability in Hybrid Magnetic Shielding Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

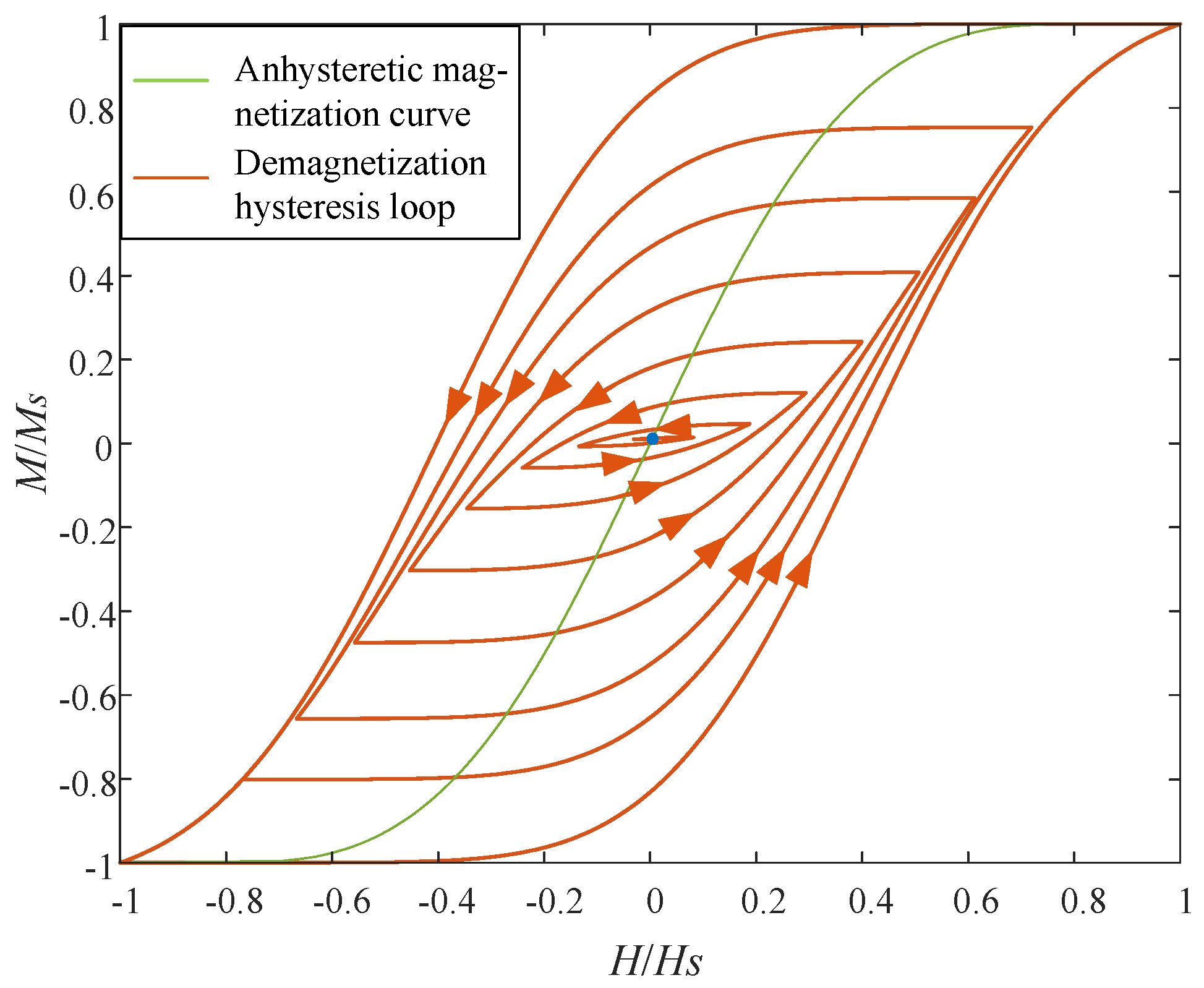

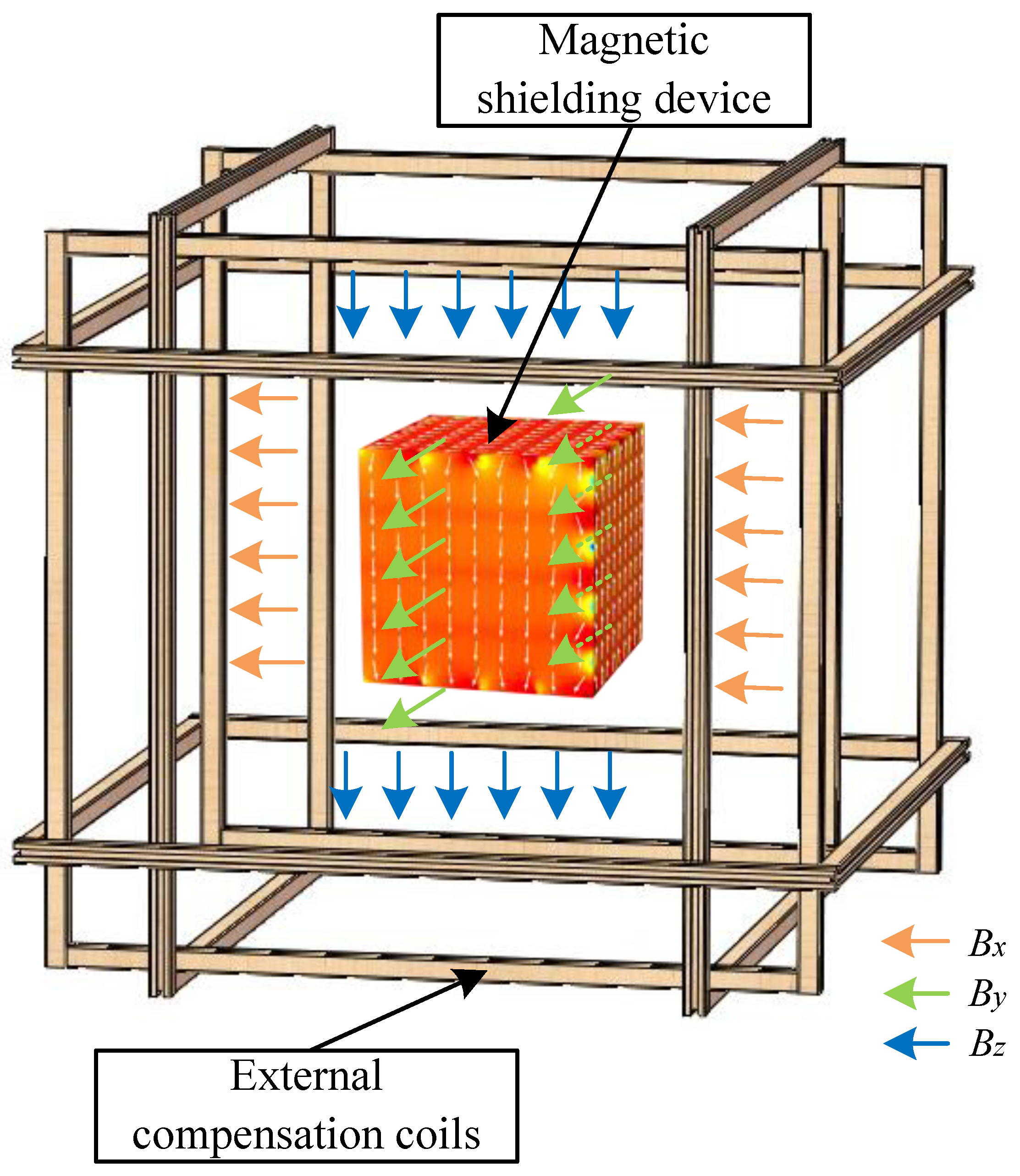

2. Magnetization Process Analysis

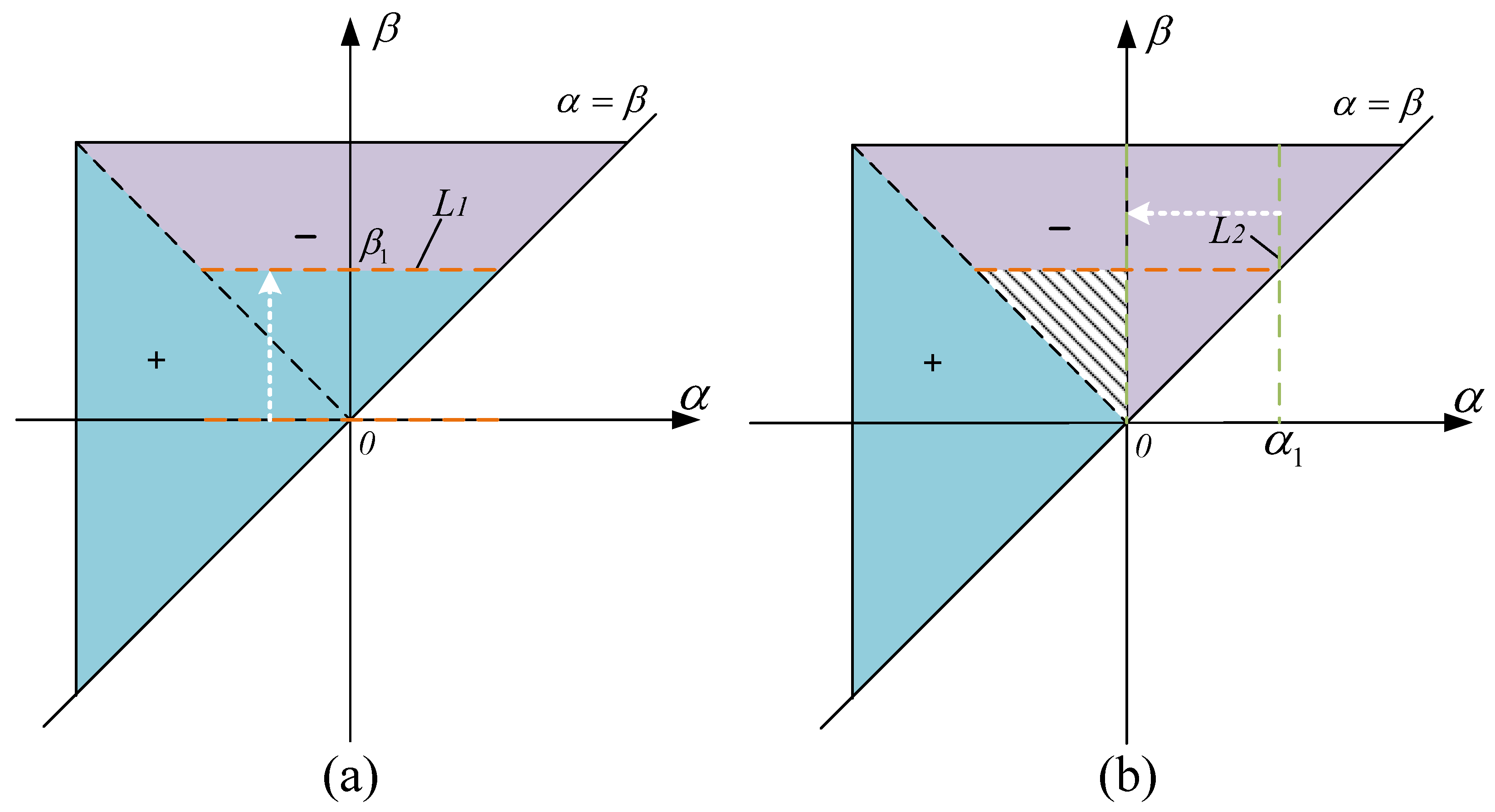

2.1. Static Magnetization Analysis

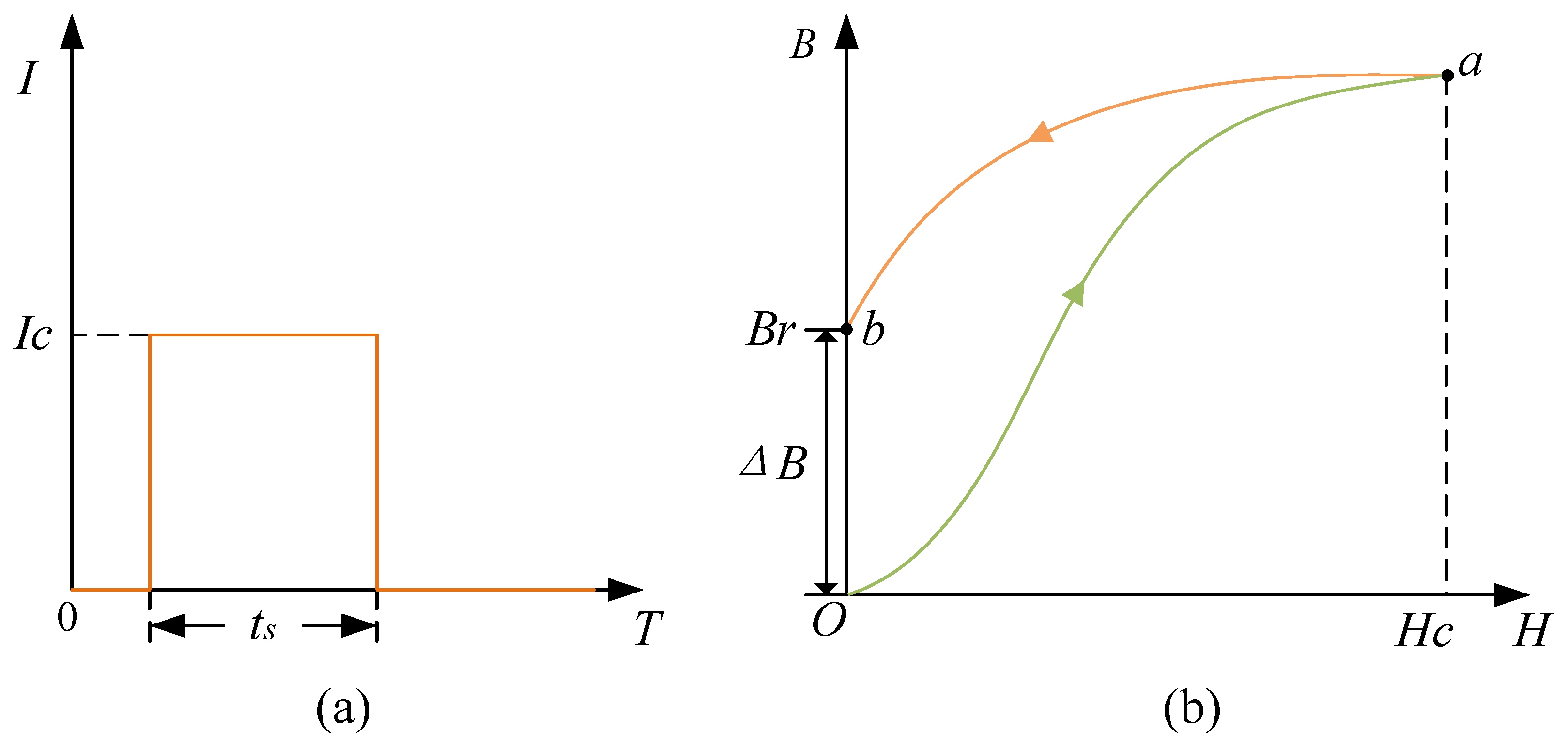

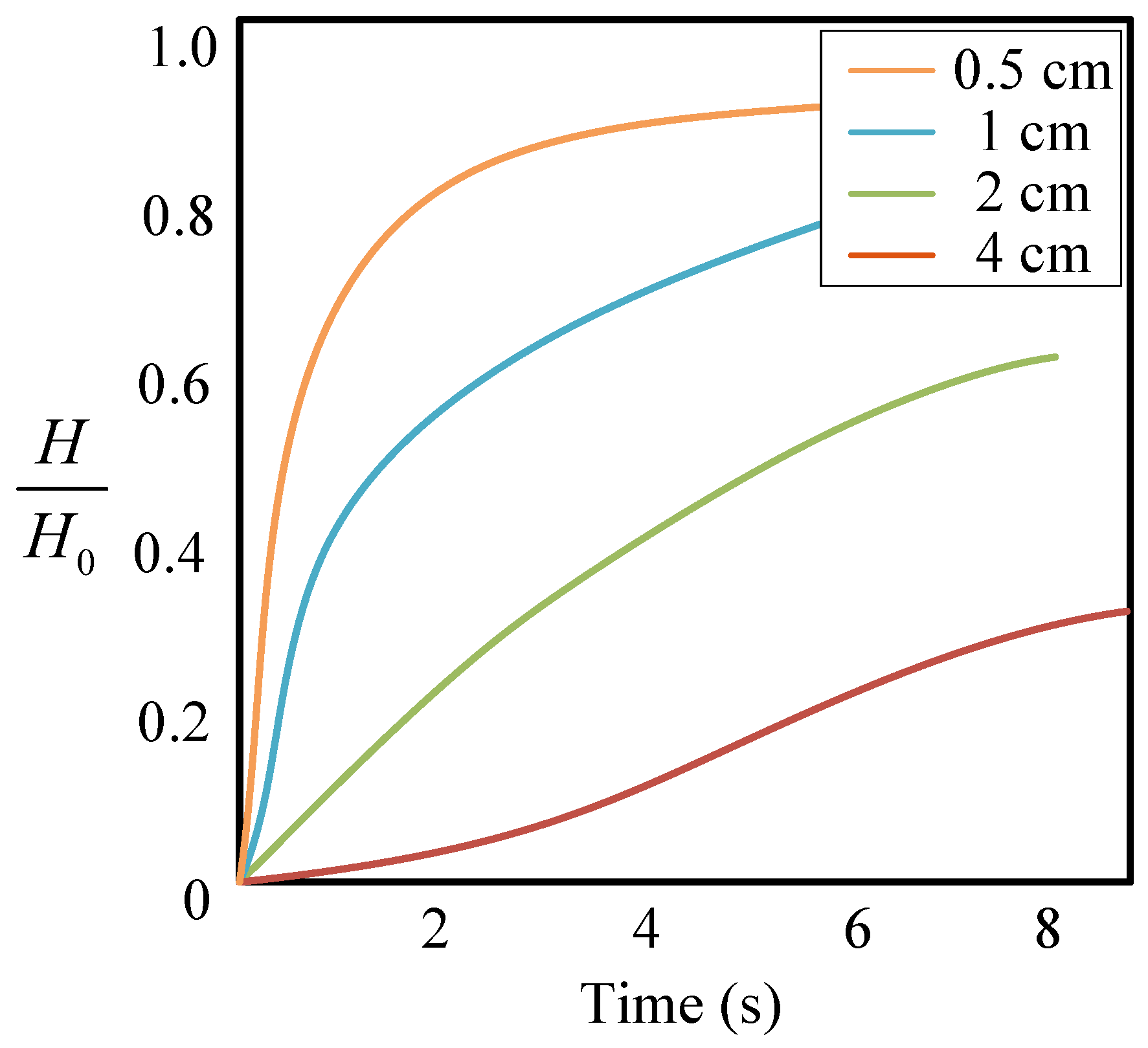

2.2. Transient Effects of Shielding Material

3. Finite Element Modeling and Simulation Analysis

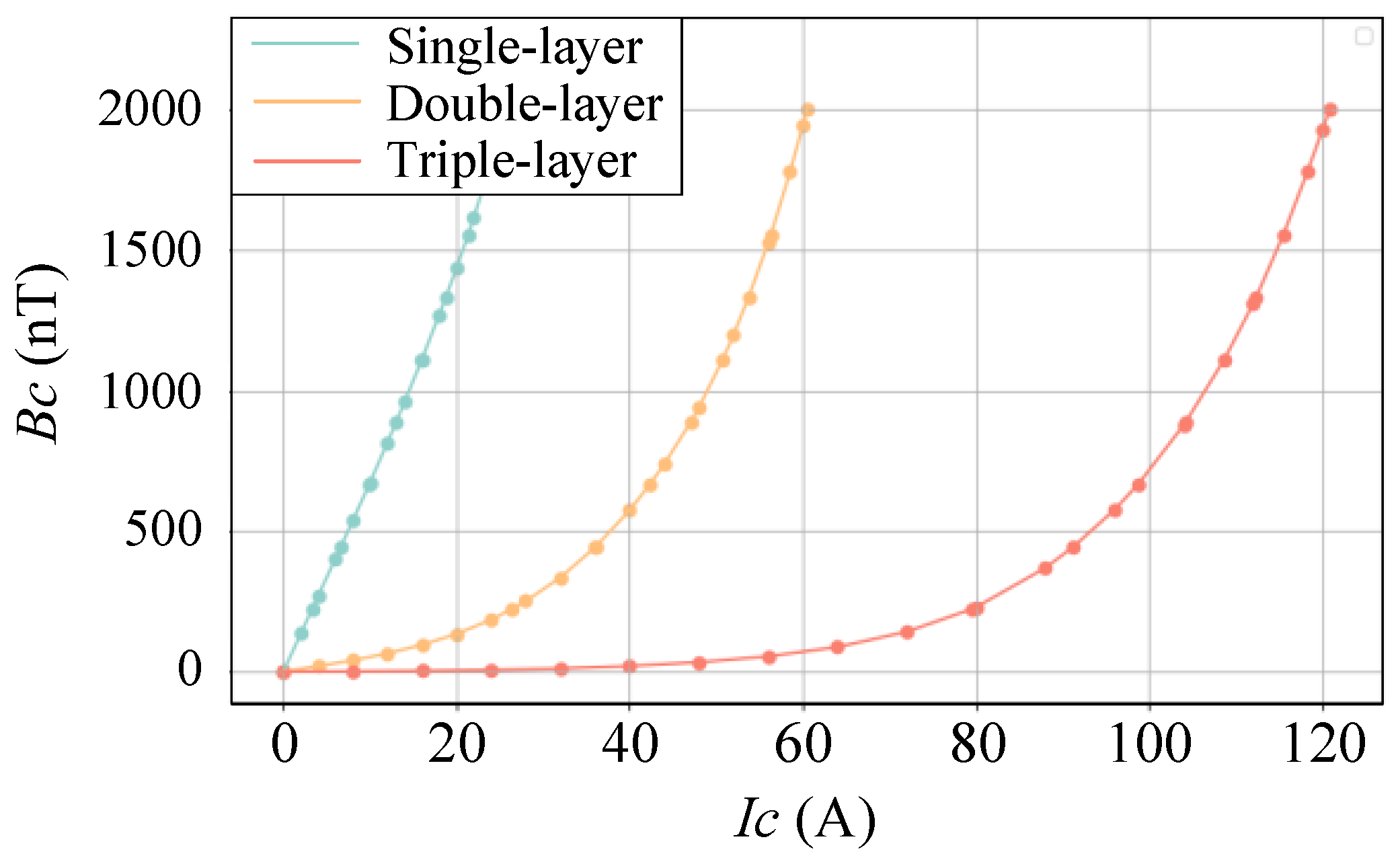

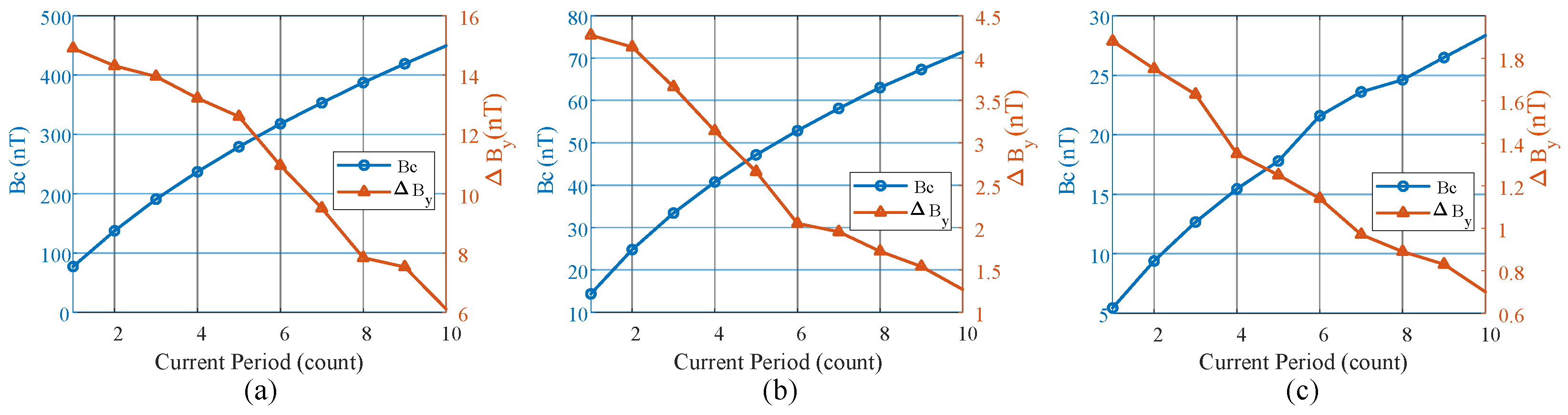

- For single-, double-, and triple-layer MSBs, with the number of turns on one side of the coil fixed at 50, a parametric sweep is performed by passing different compensation currents .

- The center point is selected as the reference point to measure the magnetic field. For a given compensation field at the center, the corresponding current is determined, and then the change in the central magnetic field relative to the initial residual magnetic field, , is calculated after the current is removed.

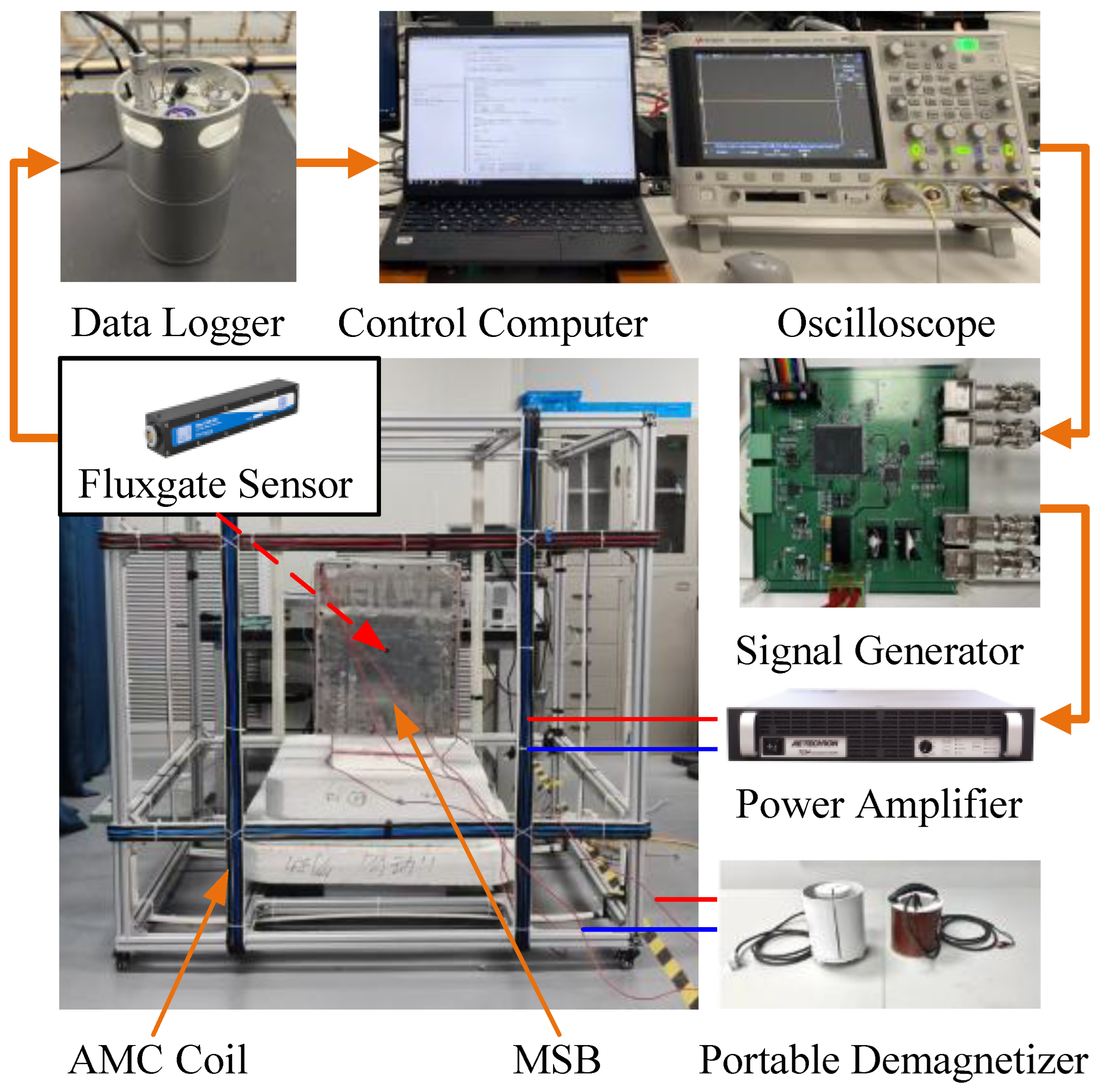

4. Experimental Validation

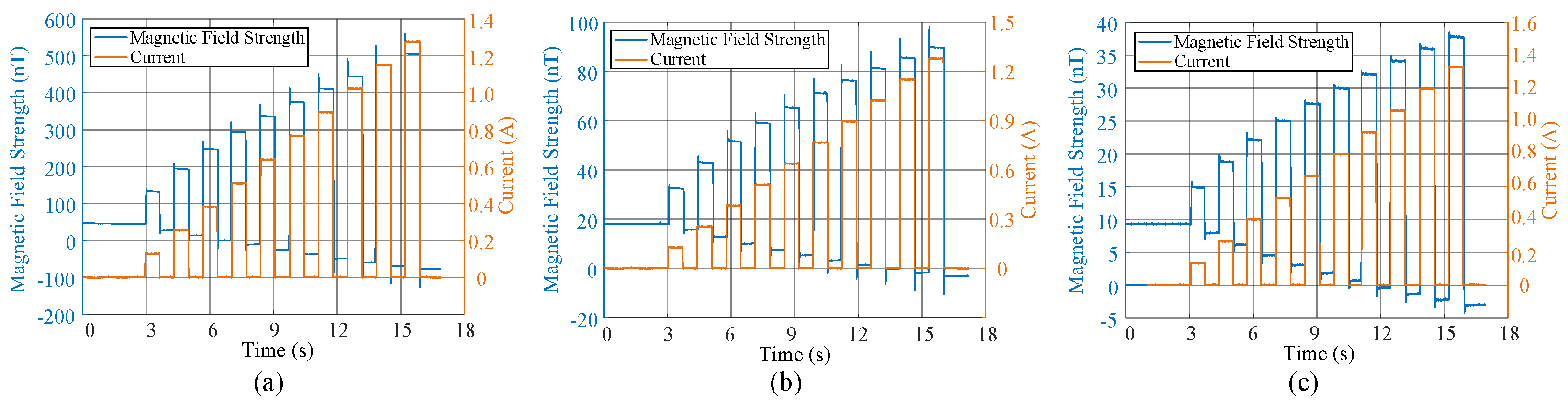

- Initial State Setting: Before testing each layer configuration, the MSB is thoroughly demagnetized using a portable demagnetizer to eliminate remanence interference and ensure consistent initial conditions.

- Sensor Deployment: A high-precision triaxial fluxgate sensor is accurately placed at the geometric center of the MSB to monitor the magnetic field changes at that point in real-time.

- Excitation Field Application: A signal generator, controlled by a computer, produces a square wave current signal with linearly increasing amplitude. This signal, after being amplified by a power amplifier, drives the AMC coil to generate a dynamically changing magnetic field outside the MSB.

- Data Acquisition: While applying the excitation field, a data logger and an oscilloscope simultaneously record the current waveform in the compensation coil and the magnetic field strength data from the fluxgate sensor at the internal center point.

- Repetitive Testing: The above experimental procedure is repeated for single-, double-, and triple-layer MSBs to obtain performance data for different configurations for subsequent comparative analysis.

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, H.; Tian, P. Composite suppression method for gradient and uniform field disturbance in magnetic shielding cylinders using DL-LESO-PDR. Measurement 2026, 258, 115906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillet, S. Magnetoencephalography for brain electrophysiology and imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gröbner, J.; Rüdhamer, M.; Fierlinger, P. A Method to Measure and Compensate Temperature-Dependent Magnetic Field Fluctuations in a Magnetically Shielded Room. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon, I.; Bales, M.; Beck, D.H.; Chupp, T.; Fierlinger, K.; Fierlinger, P.; Kuchler, F.; Lins, T.; Marino, M.G.; Naessen, B.; et al. A large-scale magnetic shield with 105 damping at millihertz frequencies. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 183903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Fierlinger, P.; Han, J.; Li, L.; Liu, T.; Schnabel, A. Limits of Low Magnetic Field Environments in Magnetic Shields. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 5385–5395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Song, X.; Duan, Z.; Suo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Jia, L. Suppression of Amplitude and Phase Errors in Optically Pumped Magnetometers Using Dual-PI Closed-Loop Control. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 73, 4001412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Schnabel, A.; Burghoff, M.; Li, L. Calculation of an optimized design of magnetic shields with integrated demagnetization coils. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 075114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, J.; Jin, C.; Liu, T.; Lin, S.; Li, L. A new calibration method for triaxial fluxgate magnetometer based on magnetic shielding room. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 4183–4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelhä, V.O.; Pukki, J.M.; Peltonen, R.S.; Penttinen, A.J.; Ilmoniemi, R.J.; Heino, J.J. The effect of shaking on magnetic shields. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1980, 16, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarev, I.; Babcock, E.; Beck, D.; Burgdorf, M.; Chesnevskaya, S.; Chupp, T.; Degenkolb, S.; Fan, I.; Fierlinger, P.; Freifrei, A.; et al. A magnetically shielded room with ultra low residual field and gradient. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 85, 075106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasada, I.; Shiokawa, M. Noise characteristics of Co-based amorphous tapes to be applied as magnetic shielding shell for magnetic shaking. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2003, 39, 3435–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Lin, S.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Jin, Y.; Sun, Z. Research on the Design Method of Uniform Magnetic Field Coil Based on the MSR. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Liu, X.; Shangguan, S.; Wen, T.; Zheng, S.; Han, B. Design of biplane coils based on funnel algorithm for generating a near-zero magnetic environment in MSR. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 6004211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wen, T.; Fang, Y.; Han, B.; Liu, X. Highly homogeneous and low-noise magnetic field compensation based on the high-uniform magnetic field coils with small coil constant. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 6004309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, F.; Li, H. Disturbance suppression based high-precision magnetic field compensation method for magnetic shielding cylinder. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, S.; Jin, C.; Dai, X.; Pan, D.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, L. Optimization Method for Weak Magnetic Measurement Environments Using Active–Passive Coupled Magnetic Shielding Analysis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Reisner, M.; Fierlinger, P.; Schnabel, A.; Stuiber, S.; Li, L. Dynamic modeling of the behavior of permalloy for magnetic shielding. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 193901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, F.; Schnabel, A.; Knappe-Grueneberg, S.; Stollfuß, D.; Burgdorf, M. Demagnetization of magnetically shielded rooms. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007, 78, 035106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupp, T.E.; Fierlinger, P.; Ramsey-Musolf, M.J.; Singh, J.T. Electric dipole moments of atoms, molecules, nuclei, and particles. Rev. Modern Phys. 2019, 91, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Lu, J.; Sun, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X. Optimal Design of Self-Shielded Biplanar Coil Assembly with Miniaturized Structure. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 9005209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zhou, W.; Xu, X.; Sun, J.; Zhao, F.; Jiang, Q. Asymmetric Cylindrical Coils Design for Uniform Magnetic Field. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 6009710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, T.M.; Holmes, N.; Mellor, S.; López, J.D.; Roberts, G.; Hill, R.M.; Boto, E.; Leggett, J.; Shah, V.; Brooks, M.J.; et al. Optically pumped magnetometers: From quantum origins to multi-channel magnetoencephalography. NeuroImage 2019, 199, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayergoyz, I.D. The classical Preisach model of hysteresis. In Mathematical Models of Hysteresis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gupta, B.; Ducharne, B.; Sebald, G.; Uchimoto, T. Preisach’s Model Extended with Dynamic Fractional Derivation Contribution. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2018, 54, 6100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, E. A Preisach model for accommodation. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1994, 30, 2701–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charap, S.H.; Ktena, A. Vector Preisach modeling (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 73, 5818–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shang, H.; Xia, D.; Wang, S.; Peng, T.; Zang, C. A Modified Vector Jiles-Atherton Hysteresis Model for the Design of Hysteresis Devices. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2023, 38, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

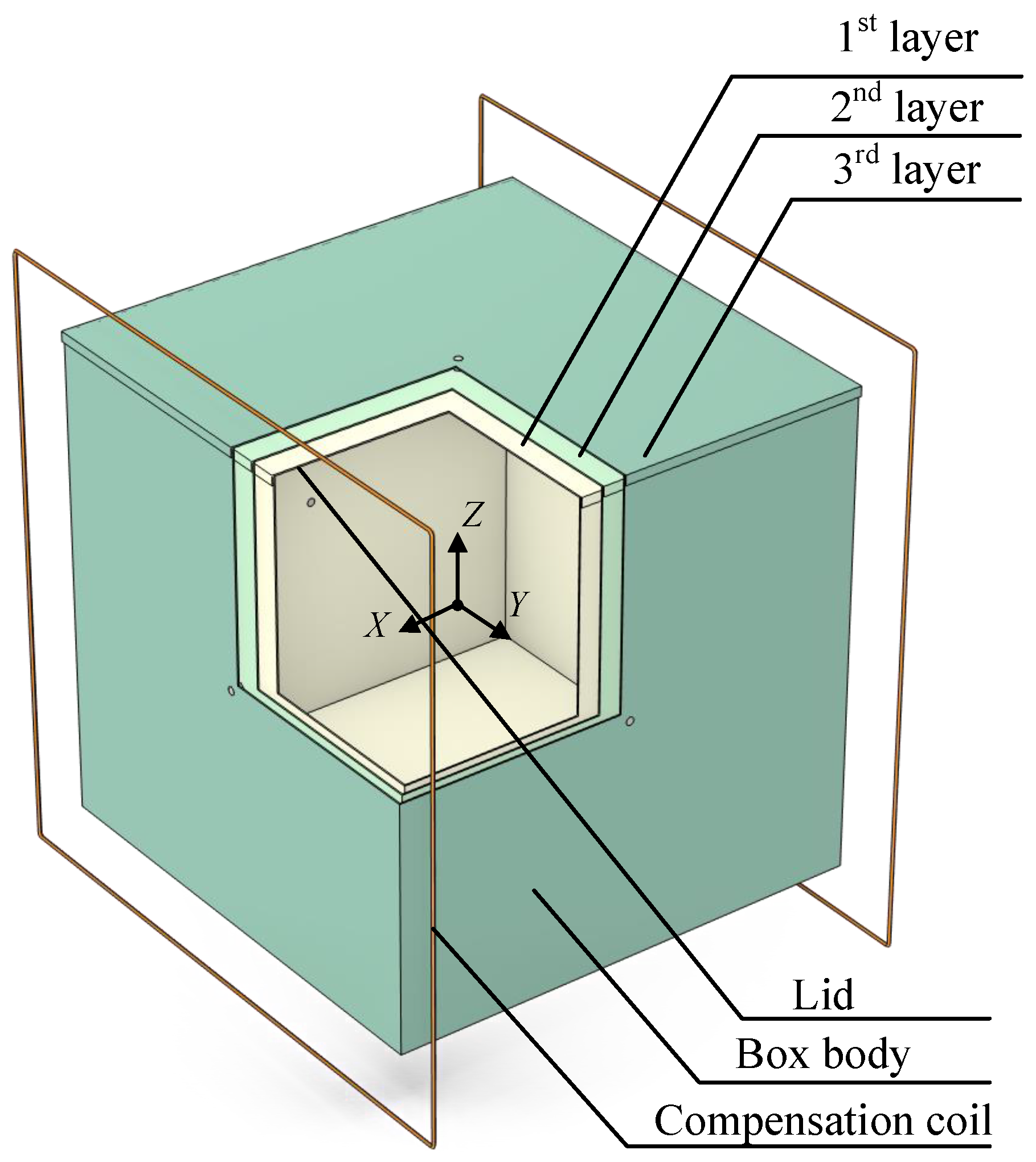

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| 1st layer box dimensions | 46 cm × 46 cm × 46 cm |

| 2nd layer box dimensions | 48 cm × 48 cm × 48 cm |

| 3rd layer box dimensions | 50 cm × 50 cm × 50 cm |

| Hole diameter | 1 cm |

| Lid height | 1 cm |

| Material thickness | 1.5 mm |

| Gap between lid and body | 5 mm |

| Coil dimensions | 60 cm × 60 cm |

| Coil distance from box | 10 cm |

| Number of Layers | Parameter a | Parameter b |

|---|---|---|

| Single-layer | 2.065 | 1.785 |

| Double-layer | 3.131 | 1.654 |

| Triple-layer | 3.221 | 1.208 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, H.; Han, B.; Yang, Z. Analysis of Passive Shielding Performance Stability in Hybrid Magnetic Shielding Devices. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13173. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413173

Yu S, Sun J, Zhang H, Han B, Yang Z. Analysis of Passive Shielding Performance Stability in Hybrid Magnetic Shielding Devices. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13173. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413173

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Shicheng, Jinji Sun, Haifeng Zhang, Bangcheng Han, and Zhouqiang Yang. 2025. "Analysis of Passive Shielding Performance Stability in Hybrid Magnetic Shielding Devices" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13173. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413173

APA StyleYu, S., Sun, J., Zhang, H., Han, B., & Yang, Z. (2025). Analysis of Passive Shielding Performance Stability in Hybrid Magnetic Shielding Devices. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13173. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413173