Semantic-Aware 3D GAN: CLIP-Guided Disentanglement for Efficient Cross-Category Shape Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

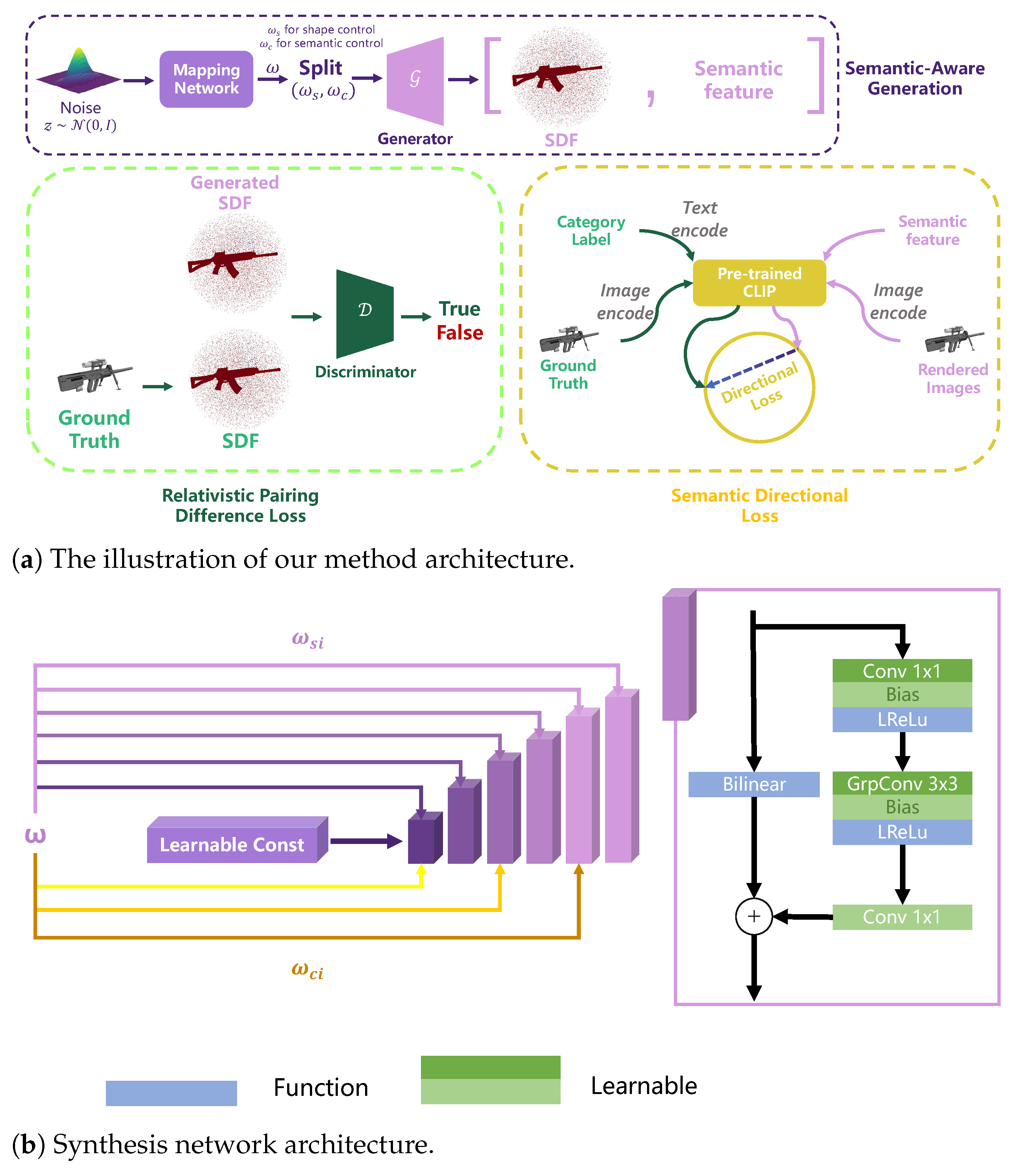

- We introduce a novel framework, a semantic-aware generator architecture that enhances the diversity and generalization ability of 3D GAN models.

- We propose a novel semantic modulation mechanism—powered by CLIP—to guide shape refinement, combined with a relativistic pairing difference loss for 3D shape optimization, leading to improvements in 3D GAN performance.

- We demonstrate through our experiments that the proposed approach can elevate the diversity of generation while maintaining quality and also improves the efficiency and stability on common large-scale datasets.

2. Related Works

2.1. 3D Generative Models

2.2. 3D GAN

3. Methodology

3.1. Semantic-Aware Generation

3.2. Semantically Guided Shape Optimization

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

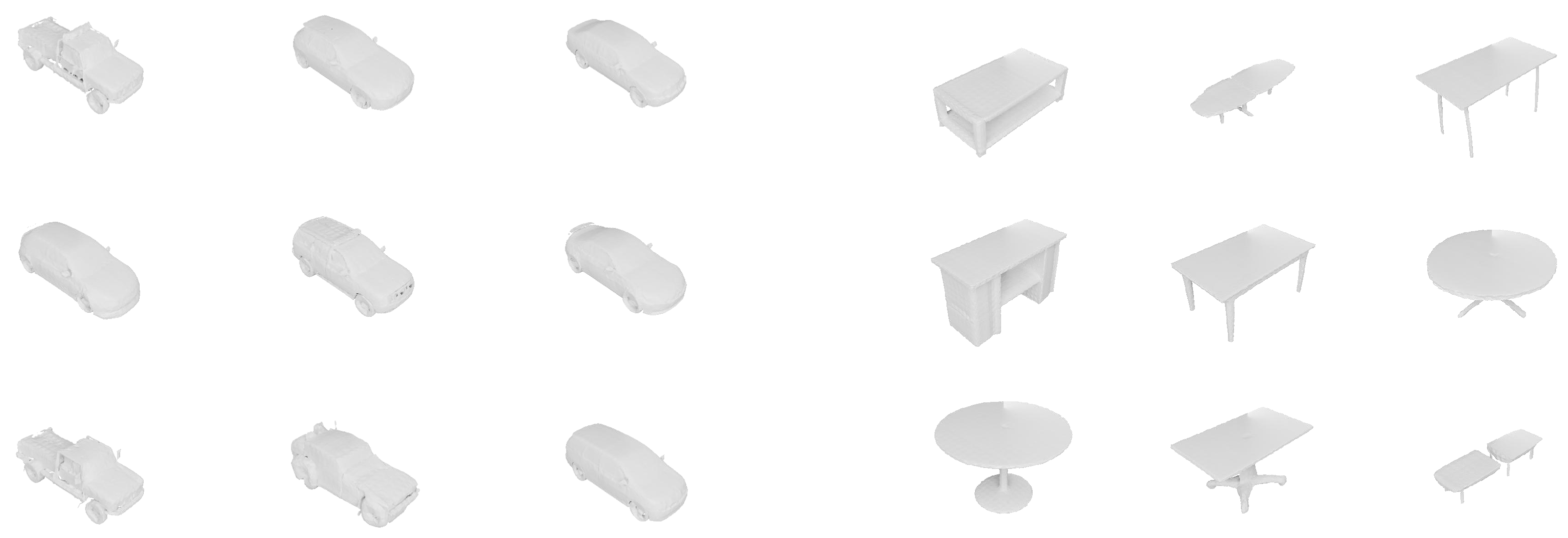

4.2. Qualitative Experiments

4.3. Quantitative Results

4.4. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| 3D | Three Dimension |

| NFE | single forward pass |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance |

| MMD | Maximum Mean Discrepancy |

| SDF | Signed Distance Field |

References

- Luo, S.; Hu, W. Diffusion probabilistic models for 3d point cloud generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2837–2845. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; Holynski, A.; Henzler, P.; Brussee, A.; Martin-Brualla, R.; Srinivasan, P.; Barron, J.T.; Poole, B. Cat3d: Create anything in 3d with multi-view diffusion models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.10314. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, T.; Fang, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, G.; Xie, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Tian, Q.; Wang, X. Gaussiandreamer: Fast generation from text to 3d gaussians by bridging 2d and 3d diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 6796–6807. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J. Stable-Dreamfusion: Text-to-3D with Stable-Diffusion, 2022. Available online: https://github.com/ashawkey/stable-dreamfusion (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Qian, G.; Mai, J.; Hamdi, A.; Ren, J.; Siarohin, A.; Li, B.; Lee, H.Y.; Skorokhodov, I.; Wonka, P.; Tulyakov, S.; et al. Magic123: One Image to High-Quality 3D Object Generation Using Both 2D and 3D Diffusion Priors. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.; Gokaslan, A.; Kuleshov, V.; Tompkin, J. The GAN is dead; long live the GAN! A Modern GAN Baseline. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A.C. Improved training of wasserstein gans. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5769–5779. [Google Scholar]

- Jolicoeur-Martineau, A. The relativistic discriminator: A key element missing from standard GAN. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.00734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Fang, T.; Schwing, A. Towards a better global loss landscape of gans. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 10186–10198. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, K.; Lucchi, A.; Nowozin, S.; Hofmann, T. Stabilizing training of generative adversarial networks through regularization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.W.; Jung, S.H.; Sim, C.B. NeXtSRGAN: Enhancing super-resolution GAN with ConvNeXt discriminator for superior realism. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 7141–7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.R.; Lin, C.Z.; Chan, M.A.; Nagano, K.; Pan, B.; Mello, S.D.; Gallo, O.; Guibas, L.; Tremblay, J.; Khamis, S.; et al. Efficient Geometry-aware 3D Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the CVPR, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pavllo, D.; Spinks, G.; Hofmann, T.; Moens, M.F.; Lucchi, A. Convolutional generation of textured 3d meshes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 870–882. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; Lv, Z.; Xu, S.; Deng, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; Tong, X.; Yang, J. Structured 3D Latents for Scalable and Versatile 3D Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Black, M.J.; Nowrouzezahrai, D.; Paull, L.; Liu, W. MeshDiffusion: Score-based Generative 3D Mesh Modeling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Kang, D.; Cheng, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Z.; Liao, J.; Cao, Y.P.; Shan, Y. Advances in 3d generation: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.17807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Shen, T.; Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Yin, K.; Li, D.; Litany, O.; Gojcic, Z.; Fidler, S. GET3D: A Generative Model of High Quality 3D Textured Shapes Learned from Images. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Amanda, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilharco, G.; Wortsman, M.; Wightman, R.; Gordon, C.; Carlini, N.; Taori, R.; Dave, A.; Shankar, V.; Namkoong, H.; Miller, J.; et al. OpenCLIP. Zenodo, 2021. If You Use This Software, Please Cite It as Below. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5143773 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Fu, Y.; Liu, W.; Jiang, Y.G. Pixel2mesh: Generating 3d mesh models from single rgb images. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14, September 2018; pp. 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gkioxari, G.; Malik, J.; Johnson, J. Mesh r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9785–9795. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Siegel, J.; Sarma, S. Pointgrow: Autoregressively learned point cloud generation with self-attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Snowmass Village, CO, USA, 1–5 March 2020; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Yoo, J.; Lee, J.; Hong, S. Setvae: Learning hierarchical composition for generative modeling of set-structured data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 15059–15068. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.; Jun, H.; Dhariwal, P.; Mishkin, P.; Chen, M. Point-e: A system for generating 3d point clouds from complex prompts. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.08751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Tulyakov, S.; Schwing, A.G.; Gui, L.Y. Sdfusion: Multimodal 3d shape completion, reconstruction, and generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 4456–4465. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Xu, C.; Jin, H.; Chen, L.; Varma T, M.; Xu, Z.; Su, H. One-2-3-45: Any single image to 3d mesh in 45 s without per-shape optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 22226–22246. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Wu, R.; Van Hoorick, B.; Tokmakov, P.; Zakharov, S.; Vondrick, C. Zero-1-to-3: Zero-shot one image to 3d object. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 9298–9309. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, B.; Jain, A.; Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B. Dreamfusion: Text-to-3d using 2d diffusion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.14988. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkühler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3d gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. Text-to-3d using gaussian splatting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 21401–21412. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Yifan, W.; Chen, H.; Yang, C.; Peng, S.; Shen, Y.; Wetzstein, G. Grm: Large gaussian reconstruction model for efficient 3d reconstruction and generation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Ren, J.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, G. Dreamgaussian: Generative gaussian splatting for efficient 3d content creation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16653. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Shi, H.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Liao, Y.; Wang, L.; Lee, L.h.; Zhou, P.Y. Dreamscene: 3d gaussian-based text-to-3d scene generation via formation pattern sampling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 214–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Xiong, W.; Nie, Y.; Jones, I.; Oğuz, B. 3dgen: Triplane latent diffusion for textured mesh generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.05371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shue, J.R.; Chan, E.R.; Po, R.; Ankner, Z.; Wu, J.; Wetzstein, G. 3d neural field generation using triplane diffusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 20875–20886. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, T.; Gao, J.; Yin, K.; Liu, M.Y.; Fidler, S. Deep marching tetrahedra: A hybrid representation for high-resolution 3d shape synthesis. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 6087–6101. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.H.; Gao, J.; Tang, L.; Takikawa, T.; Zeng, X.; Huang, X.; Kreis, K.; Fidler, S.; Liu, M.Y.; Lin, T.Y. Magic3d: High-resolution text-to-3d content creation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Xue, T.; Freeman, B.; Tenenbaum, J. Learning a probabilistic latent space of object shapes via 3d generative-adversarial modeling. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, T.; Li, C.; Theis, L.; Richardt, C.; Yang, Y.L. Hologan: Unsupervised learning of 3d representations from natural images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7588–7597. [Google Scholar]

- Henzler, P.; Mitra, N.J.; Ritschel, T. Escaping plato’s cave: 3d shape from adversarial rendering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9984–9993. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, T.H.; Richardt, C.; Mai, L.; Yang, Y.; Mitra, N. Blockgan: Learning 3d object-aware scene representations from unlabelled images. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6767–6778. [Google Scholar]

- Pavllo, D.; Kohler, J.; Hofmann, T.; Lucchi, A. Learning Generative Models of Textured 3D Meshes from Real-World Images. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Li, T.; Zhang, W.H.; Lee, T.S. Surfgen: Adversarial 3d shape synthesis with explicit surface discriminators. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 16238–16248. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.J.; Florence, P.; Straub, J.; Newcombe, R.; Lovegrove, S. Deepsdf: Learning continuous signed distance functions for shape representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lorensen, W.E.; Cline, H.E. Marching cubes: A high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. ACM SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 1987, 21, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1812.04948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, T.; Aila, T.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J. Progressive Growing of GANs for Improved Quality, Stability, and Variation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10196. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, S.; Shi, B.; Pollefeys, M.; Cui, Z. Dist: Rendering deep implicit signed distance function with differentiable sphere tracing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2019–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.X.; Funkhouser, T.; Guibas, L.; Hanrahan, P.; Huang, Q.; Li, Z.; Savarese, S.; Savva, M.; Song, S.; Su, H.; et al. Shapenet: An information-rich 3d model repository. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.S.; Liu, Y.; Tong, X. Dual Octree Graph Networks for Learning Adaptive Volumetric Shape Representations. ACM Trans. Graph. (SIGGRAPH) 2022, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Hong, F.; Wu, T.; Pan, L.; Liu, Z. DiffTF++: 3D-aware Diffusion Transformer for Large-Vocabulary 3D Generation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.08055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Y.; Alliegro, A.; Artemov, A.; Tommasi, T.; Sirigatti, D.; Rosov, V.; Dai, A.; Nießner, M. MeshGPT: Generating Triangle Meshes with Decoder-Only Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Category |

|---|---|

| Single-Category Dataset | Airplane |

| Rifle | |

| Motorbike | |

| Chair | |

| Two-category Dataset | Airplane + Rifle |

| Airplane + Chair | |

| Airplane + Motorbike | |

| Rifle + Chair | |

| Rifle + Motorbike | |

| Chair + Motorbike | |

| Three-category Dataset | Airplane + Rifle + Motorbike |

| Airplane + Rifle + Chair | |

| Rifle + Chair + Motorbike | |

| Airplane + Chair + Motorbike | |

| Full-set Dataset | Airplane + Rifle + Chair + Motorbike |

| Category | Method | MMD ↓ | FID ↓ | COV(%) ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG3D [13] | 11.68 | 101.97 | 24.60 | |

| GET3D [18] | 9.91 | 94.90 | 28.67 | |

| Motorbike | DiffTF [53] | 6.78 | 80.51 | 31.96 |

| MeshGPT [54] | 6.64 | 81.78 | 27.51 | |

| Ours (Semantically Guided 3D GAN) | 7.71 | 87.63 | 29.01 | |

| EG3D | 10.41 | 40.93 | 35.85 | |

| GET3D | 9.65 | 36.18 | 38.43 | |

| Chair | DiffTF | 6.31 | 33.58 | 42.24 |

| MeshGPT | 6.48 | 32.05 | 49.31 | |

| Ours (Semantically Guided 3D GAN) | 7.94 | 35.67 | 48.79 | |

| EG3D | 4.74 | 30.11 | 42.73 | |

| GET3D | 3.74 | 22.07 | 47.24 | |

| Airplane | DiffTF | 3.28 | 14.73 | 50.33 |

| MeshGPT | 3.45 | 14.63 | 55.22 | |

| Ours (Semantically Guided 3D GAN) | 3.23 | 17.84 | 47.16 | |

| EG3D | 5.43 | 35.74 | 25.45 | |

| GET3D | 3.67 | 22.20 | 29.32 | |

| Rifle | DiffTF | 3.24 | 13.30 | 47.48 |

| MeshGPT | 3.50 | 13.89 | 51.03 | |

| Ours (Semantically Guided 3D GAN) | 3.54 | 16.64 | 50.60 |

| Dataset Setting | Categories | MMD ↓ | FID ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two Category | Rifle + Chair | 9.81 | 18.87 |

| Rifle + Airplane | 5.02 | 21.81 | |

| Rifle + Motorbike | 3.68 | 89.03 | |

| Chair + Airplane | 10.02 | 21.14 | |

| Chair + Motorbike | 16.57 | 90.28 | |

| Airplane + Motorbike | 12.83 | 83.46 | |

| Average | 9.66 | 54.10 | |

| Three Category | Rifle + Chair + Airplane | 10.82 | 18.23 |

| Rifle + Chair + Motorbike | 20.18 | 99.07 | |

| Rifle + Airplane + Motorbike | 17.93 | 92.35 | |

| Chair + Airplane + Motorbike | 19.54 | 93.04 | |

| Average | 17.12 | 75.67 | |

| Full Set | Rifle + Chair + Airplane + Motorbike | 23.35 | 103.77 |

| Method | Parameters | Inference Time (ms) | VRAM (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GET3D | 0.34B | 151 | 4.58 |

| DiffTF | 1.2B | 20,000 ± 15,000 | 8.02 |

| Ours (Semantically Guided 3D GAN) | 0.32B | 139 | 4.5 |

| Ours (two-category dataset) | 0.32B | 267 | 4.5 |

| Categories | Semantic Optimization | R3GAN Loss | MMD ↓ (‰) | FID ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifle + Chair | ✓ | ✓ | 9.81 | 18.87 |

| ✓ | × | 10.39 | 20.56 | |

| × | ✓ | 12.39 | 21.28 | |

| × | × | 12.50 | 21.60 | |

| Rifle + Chair + Airplane | ✓ | ✓ | 10.82 | 18.23 |

| ✓ | × | 11.58 | 21.50 | |

| × | ✓ | 13.06 | 24.17 | |

| × | × | 15.74 | 28.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, J. Semantic-Aware 3D GAN: CLIP-Guided Disentanglement for Efficient Cross-Category Shape Generation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13163. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413163

Cai W, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zeng Z, Li X, Liu J. Semantic-Aware 3D GAN: CLIP-Guided Disentanglement for Efficient Cross-Category Shape Generation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13163. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413163

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Weinan, Zongji Wang, Yuanben Zhang, Zhihong Zeng, Xinming Li, and Junyi Liu. 2025. "Semantic-Aware 3D GAN: CLIP-Guided Disentanglement for Efficient Cross-Category Shape Generation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13163. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413163

APA StyleCai, W., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Zeng, Z., Li, X., & Liu, J. (2025). Semantic-Aware 3D GAN: CLIP-Guided Disentanglement for Efficient Cross-Category Shape Generation. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13163. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413163