Comparative Study of Ferrate, Persulfate, and Percarbonate as Oxidants in Plasma-Based Dye Remediation: Assessing Their Potential for Process Enhancement

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

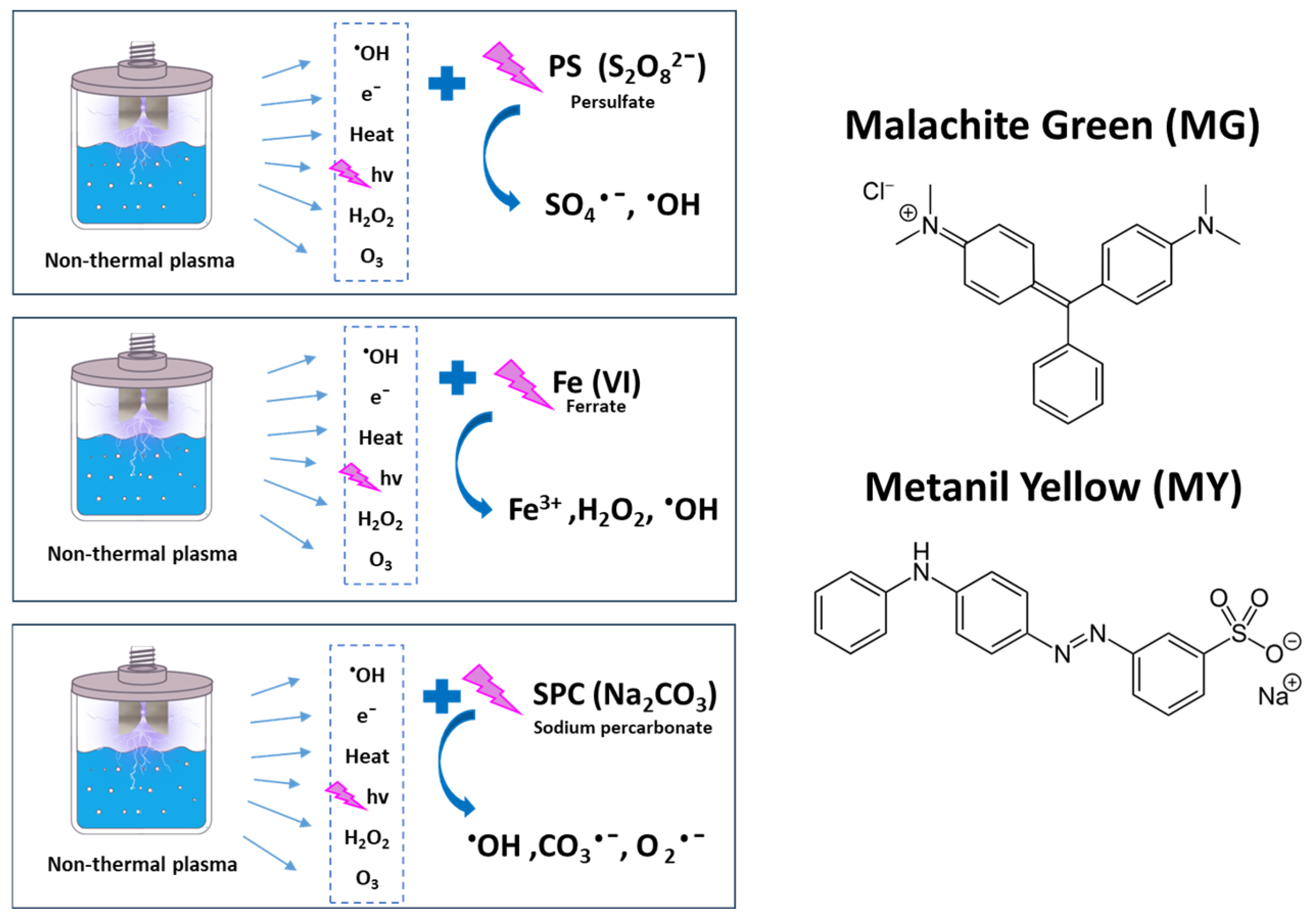

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

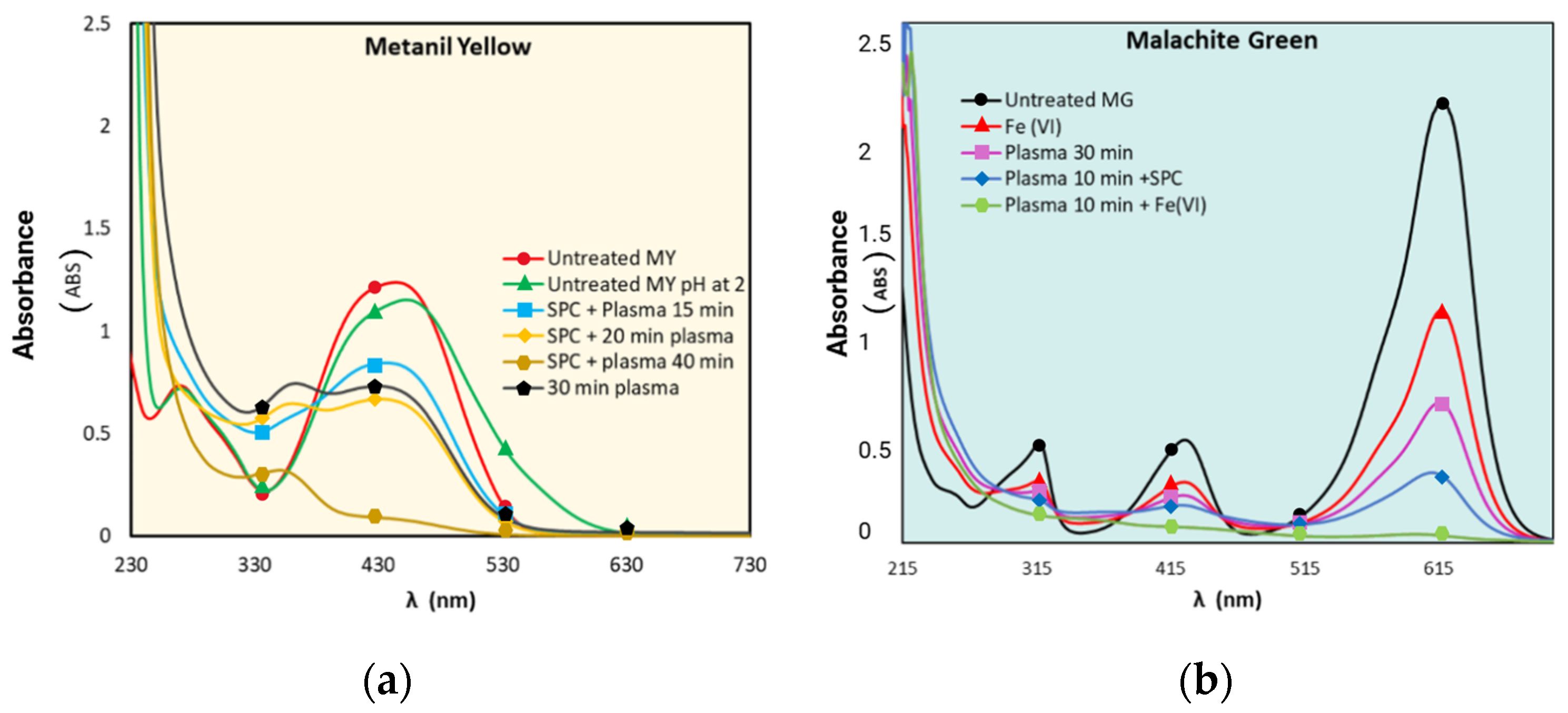

3.1. Decolorization Profiles

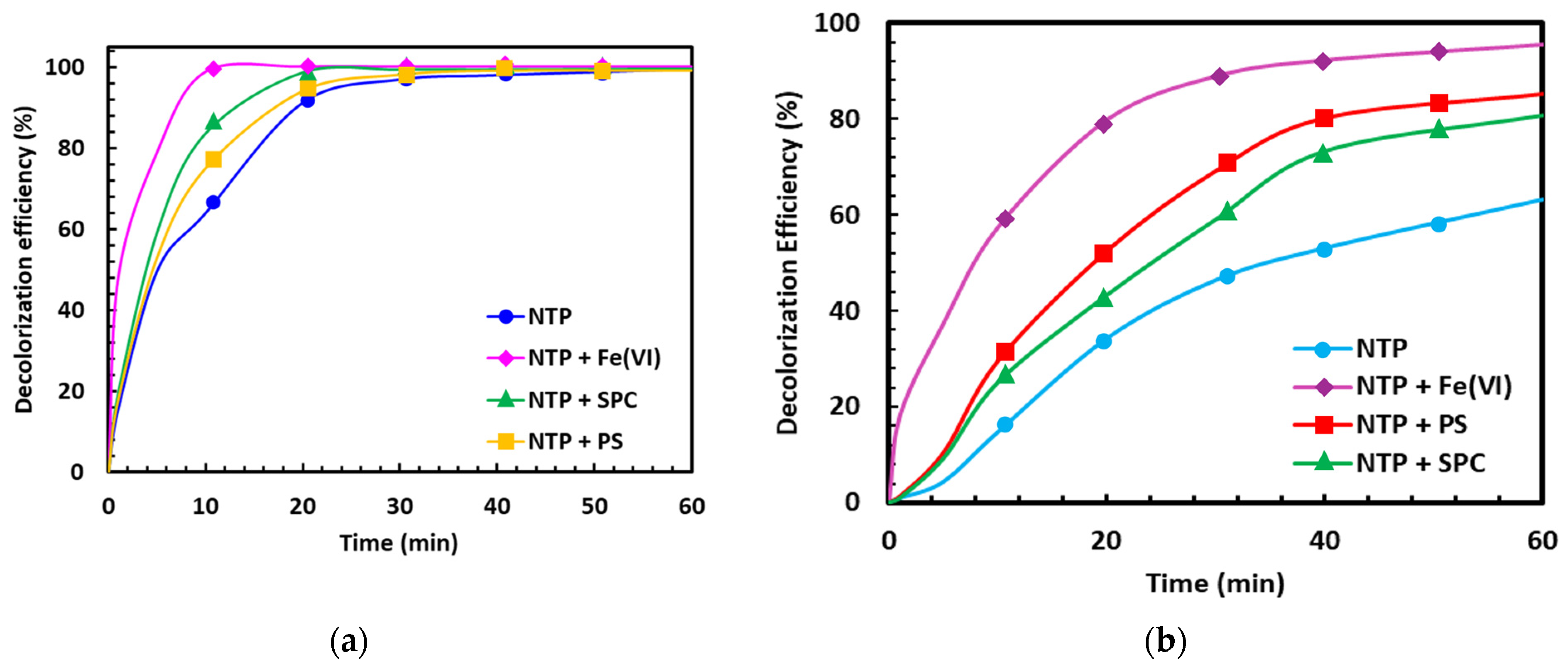

3.2. Decolorization Efficiency and Kinetics

3.3. Response Surface Modeling (RSM)

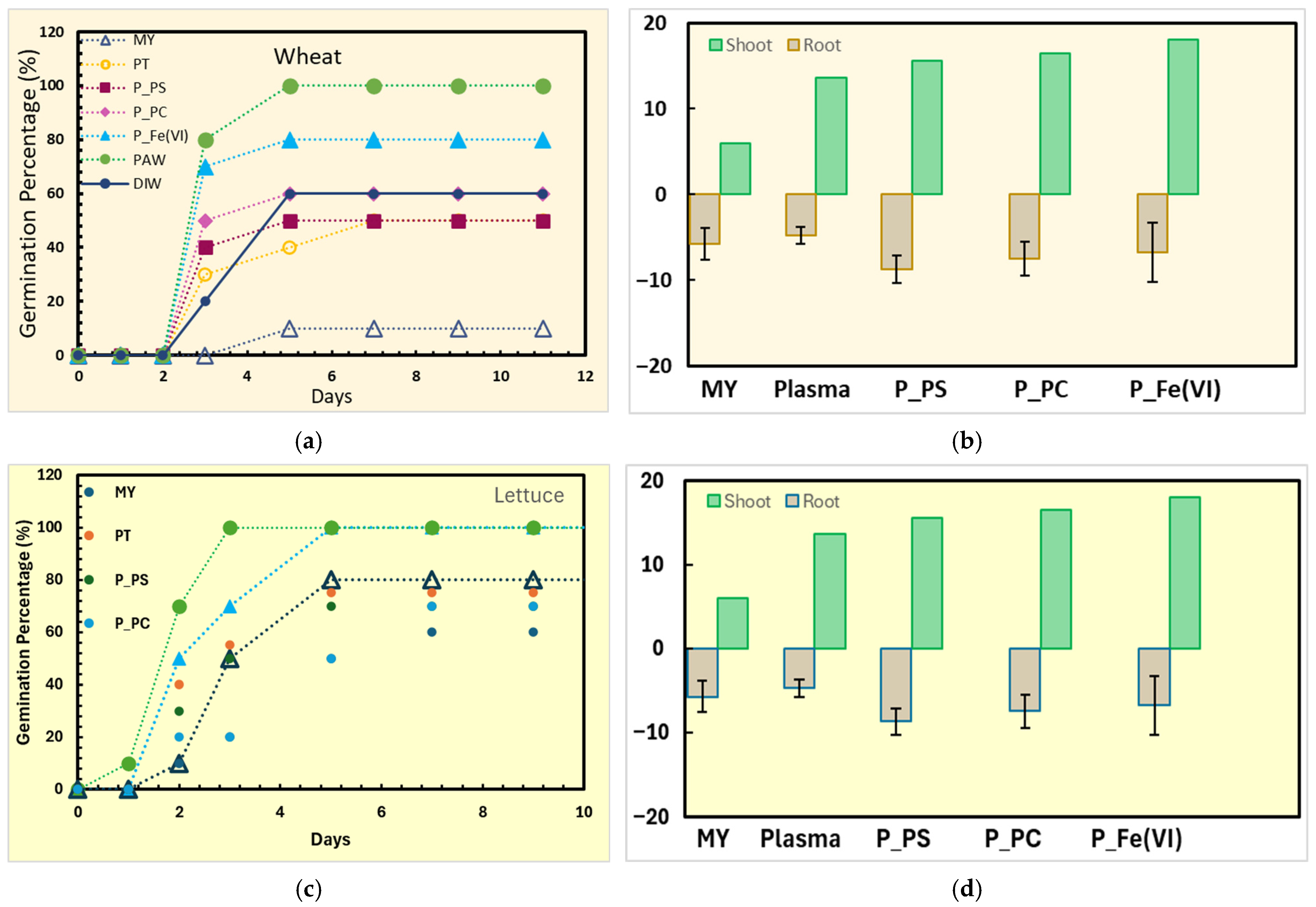

3.4. Phytotoxicity Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Decolorization Mechanisms

4.2. Kinetic Behavior and Mechanistic Interpretation

4.3. RSM-Based Process Optimization

4.4. Phytotoxicity Mechanism and Environmental Safety Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassan, M.M.; Carr, C.M. A critical review on recent advancements of the removal of reactive dyes from dyehouse effluent by ion-exchange adsorbents. Chemosphere 2018, 209, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, A.A.H.; Ahmed, M.A.; Khan, M.A.; Alothman, Z.A.; Rafatullah, M.; Islam, M.A.; Siddiqui, M.R. Quantitative analysis of malachite green in environmental samples using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Water 2021, 13, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A.G. Contaminants of emerging concern removal by high-energy oxidation-reduction processes: State of the art. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, W. Coupling of heterogeneous advanced oxidation processes and photocatalysis in efficient degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride by Fe-based MOFs: Synergistic effect and degradation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 369, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Bu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, S.; Shi, Z.; Dionysiou, D.D. Degradation of contaminants of emerging concern in UV/Sodium percarbonate Process: Kinetic understanding of carbonate radical and energy consumption evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 135995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, P.; Monica, V.E.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Water decontamination using non-thermal plasma: Concepts, applications, and prospects. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Moussavi, G.; Ehrampoosh, M.H.; Giannakis, S. A systematic review of non-thermal plasma (NTP) technologies for synthetic organic pollutants (SOPs) removal from water: Recent advances in energy yield aspects as their key limiting factor. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 51, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Amusa, H.K.; Eniola, J.O.; Giwa, A.; Pikuda, O.; Dindi, A.; Bilad, M.R. Hazardous and emerging contaminants removal from water by plasma-based treatment: A review of recent advances. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 14, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cheng, J.; Chen, Q.; Yin, Z. The Types of Plasma Reactors in Wastewater Treatment. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 208, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Mahvi, A.H.; Salmani, M.H.; Sharifian, M.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Ehrampoush, M.H. Dielectric barrier discharge plasma combined with nano catalyst for aqueous amoxicillin removal: Performance modeling, kinetics and optimization study, energy yield, degradation pathway, and toxicity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 251, 117270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Hou, D.; Tang, Y.; Qie, H.; Xu, R.; Zhao, P.; Lin, A.; Liu, M. Natural magnetite as an efficient green catalyst boosting peroxydisulfate activation for pollutants degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, W.; Lu, W.; Mei, L.; Jia, D.; Cao, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhan, C.; Li, M. Research on different oxidants synergy with dielectric barrier discharge plasma in degradation of Orange G: Efficiency and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 277, 119473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yuan, D.; Rao, Y.; Li, M.; Shi, G.; Gu, J.; Zhang, T. Percarbonate promoted antibiotic decomposition in dielectric barrier discharge plasma. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y. Analysis of influencing parameters and reactive substance for enrofloxacin degradation in a dielectric barrier discharge plasma/peroxydisulfate system. Environ. Eng. Res. 2024, 29, 230717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzinfar, B.; Qaderi, F. Synergistic degradation of aqueous p-nitrophenol using DBD plasma combined with ZnO photocatalyst. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Lv, J.; Yang, G. Dielectric barrier discharge combined with Fe(III)-NTA activated persulfate for efficient degradation of enrofloxacin in water. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2024, 36, 2319250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzar, A.; Goutomo, B.T.; Nam, K.; Kim, I.K. Efficient removal of tetracycline antibiotic by nonthermal plasma-catalysis combination process. Environ. Eng. Res. 2025, 30, 240254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.L.; Wang, Y.S.; Liu, C.H. Preparation of potassium ferrate from spent steel pickling liquid. Metals 2015, 5, 1770–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sumita; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, C.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S.; Pang, W. A Review of Research Progress in the Preparation and Application of Ferrate(VI). Water 2023, 15, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gong, S.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Deng, H. Progress and problems of water treatment based on UV/persulfate oxidation process for degradation of emerging contaminants: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, S.; Yang, Y.; Yao, B.; Tang, Y.; Luo, L.; Zhi, D.; Wan, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Y. A review on percarbonate-based advanced oxidation processes for remediation of organic compounds in water. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoot-Nezhad, A.; Saebnoori, E.; Danaee, I.; Elahi, S.; Panah, N.B.; Khosravi-Nikou, M.R. Evaluation of the oxidative degradation of aromatic dyes by synthesized nano ferrate(VI) as a simple and effective treatment method. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 49, 103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort, O.; Usman, M.; Hanna, K. Ferrate(VI) oxidation of pentachlorophenol in water and soil. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, M.B.; Urynowicz, M.A.; Schultz, C.L.; Budhathoki, S. A comparison of the soil natural oxidant demand exerted by permanganate, hydrogen peroxide, sodium persulfate, and sodium percarbonate. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, T.; Schupp, N.; Sprang, F.; Horsten, T.; Wittgens, B.; Waldvogel, S.R. Peroxodicarbonate-a renaissance of an electrochemically generated green oxidizer. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 7136–7147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kyere-Yeboah, K.; Ge, Y.; Qiao, X. Effects of sodium persulfate and percarbonate on the degradation of 2,4- dichlorophenol in a dielectric barrier discharge reactor. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2024, 204, 109953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Pan, S.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, T. Persulfate activated by non-thermal plasma for organic pollutants degradation: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghernaout, D.; Elboughdiri, N. Communication Water Disinfection: Ferrate (VI) as the Greenest Chemical-A Review. Appl. Eng. 2019, 3, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst Dose (mmole·L−1) | Decolorization Efficiency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 min | 15 min | 30 min | |

| 0 (NTP Alone) | 42.24 | 66.11 | 96.26 |

| 0.05 | 65.37 | 81.58 | 99.48 |

| 0.5 | 91.66 | 99.89 | 99.89 |

| 1.5 | 98.07 | 99.70 | 99.99 |

| 3 | 93.54 | 99.99 | 99.99 |

| 5 | 75.99 | 89.13 | 95.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouzar, A.; Goutomo, B.T.; Lee, K.-M.; Kim, I.-K. Comparative Study of Ferrate, Persulfate, and Percarbonate as Oxidants in Plasma-Based Dye Remediation: Assessing Their Potential for Process Enhancement. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13158. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413158

Ouzar A, Goutomo BT, Lee K-M, Kim I-K. Comparative Study of Ferrate, Persulfate, and Percarbonate as Oxidants in Plasma-Based Dye Remediation: Assessing Their Potential for Process Enhancement. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13158. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413158

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuzar, Amina, Bimo Tri Goutomo, Kyung-Min Lee, and Il-Kyu Kim. 2025. "Comparative Study of Ferrate, Persulfate, and Percarbonate as Oxidants in Plasma-Based Dye Remediation: Assessing Their Potential for Process Enhancement" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13158. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413158

APA StyleOuzar, A., Goutomo, B. T., Lee, K.-M., & Kim, I.-K. (2025). Comparative Study of Ferrate, Persulfate, and Percarbonate as Oxidants in Plasma-Based Dye Remediation: Assessing Their Potential for Process Enhancement. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13158. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413158