Enhanced Drilling Accuracy in Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap Using a Novel Drill-Fitting Hole Guide: A 3D Simulation-Based In Vitro Comparison with Conventional Guide Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

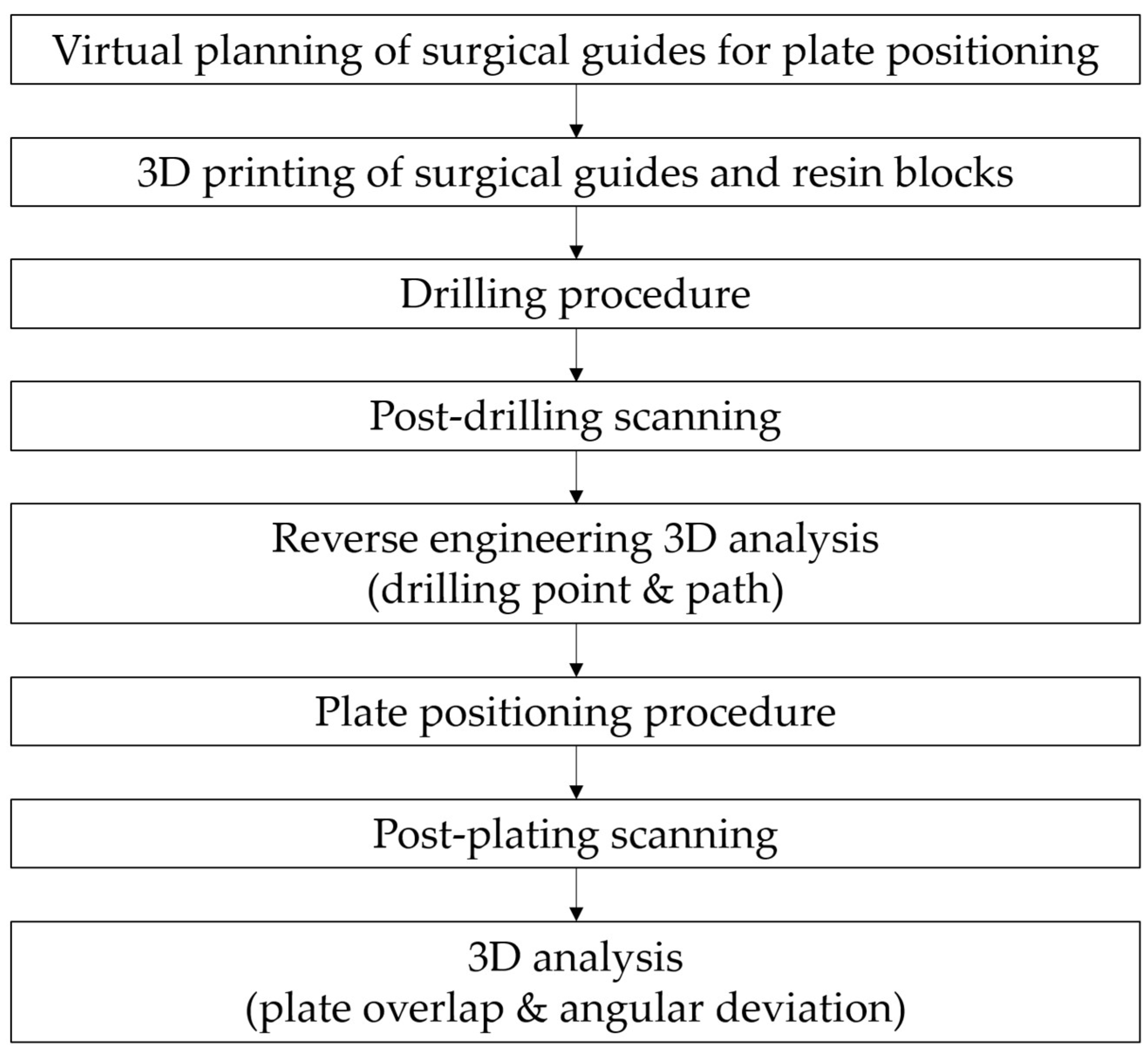

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

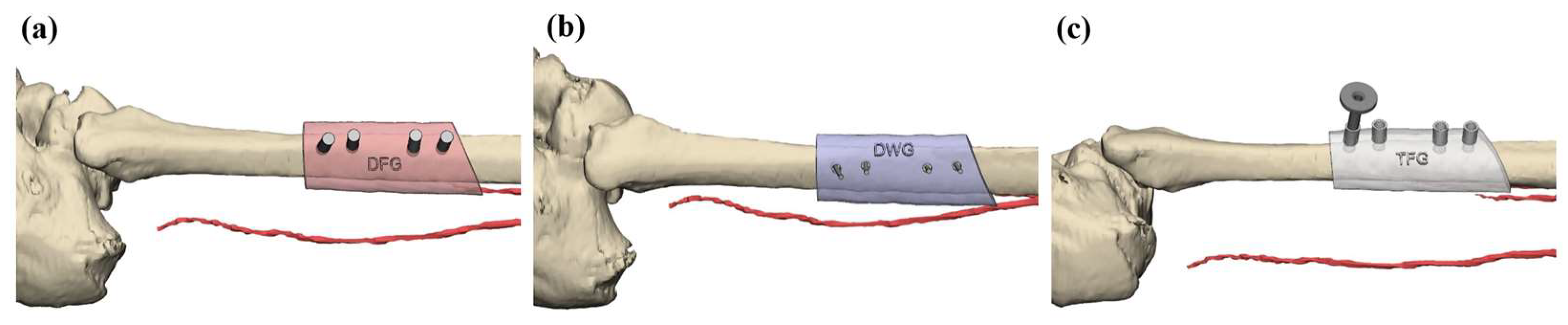

2.2. Virtual Planning and Surgical Guide Fabrication

2.3. Drilling Accuracy Test

2.4. Plate Positioning Accuracy Test

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

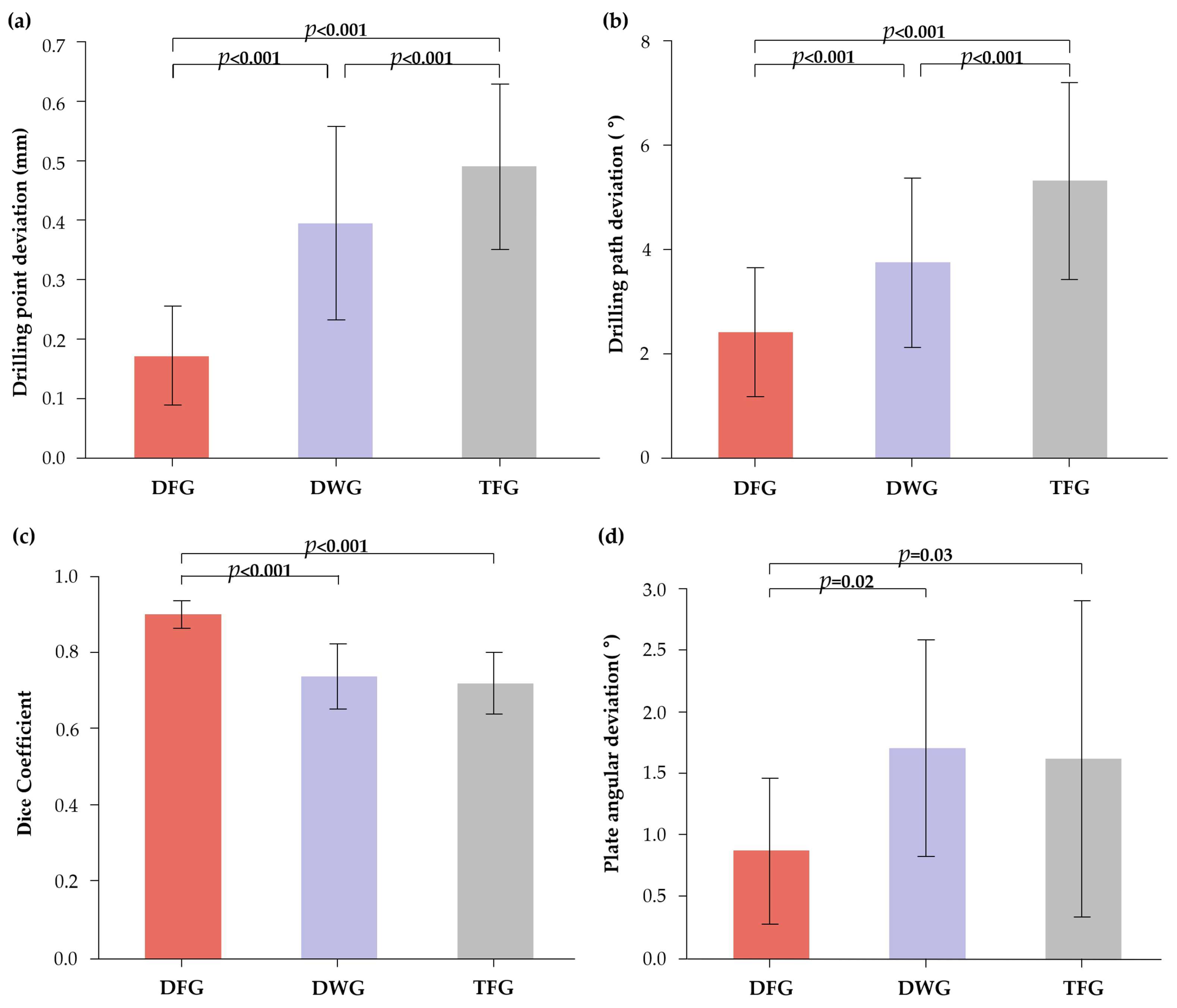

3.1. Drilling Point Deviation

3.2. Drilling Path Deviation

3.3. Plate Overlap Ratio (Dice Coefficient)

3.4. Plate Angular Deviation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirsch, D.L.; Garfein, E.S.; Christensen, A.M.; Weimer, K.A.; Saddeh, P.B.; Levine, J.P. Use of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing to produce orthognathically ideal surgical outcomes: A paradigm shift in head and neck reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, M.E.; Altman, A.; Elrefai, R.; Shipman, P.; Looney, S.; Elsalanty, M. The use of vascularized fibula flap in mandibular reconstruction; A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the observational studies. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.A. Fibula free flap: A new method of mandible reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1989, 84, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S.; Barry, C.; Ho, M.; Shaw, R. A new classification for mandibular defects after oncological resection. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e23–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsitano, A.; Battaglia, S.; Ricotta, F.; Bortolani, B.; Cercenelli, L.; Marcelli, E.; Cipriani, R.; Marchetti, C. Accuracy of CAD/CAM mandibular reconstruction: A three-dimensional, fully virtual outcome evaluation method. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 46, 1121–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascha, F.; Winter, K.; Pietzka, S.; Heufelder, M.; Schramm, A.; Wilde, F. Accuracy of computer-assisted mandibular reconstructions using patient-specific implants in combination with CAD/CAM fabricated transfer keys. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.M.; Howe, B.M.; O’Byrne, T.J.; Alexander, A.E.; Morris, J.M.; Moore, E.J.; Kasperbauer, J.L.; Janus, J.R.; Van Abel, K.M.; Dickens, H.J.; et al. Short and long-term outcomes of three-dimensional printed surgical guides and virtual surgical planning versus conventional methods for fibula free flap reconstruction of the mandible: Decreased nonunion and complication rates. Head Neck 2021, 43, 2342–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powcharoen, W.; Yang, W.F.; Yan Li, K.; Zhu, W.; Su, Y.X. Computer-Assisted versus Conventional Freehand Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 144, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Cai, X.; Sun, W.; Chen, C.; Meng, L. Application of dynamic navigation technology in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 29, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritschl, L.M.; Kilbertus, P.; Grill, F.D.; Schwarz, M.; Weitz, J.; Nieberler, M.; Wolff, K.-D.; Fichter, A.M. In-house, open-source 3D-software-based, CAD/CAM-planned mandibular reconstructions in 20 consecutive free fibula flap cases: An explorative cross-sectional study with three-dimensional performance analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 731336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baar, G.J.C.; Forouzanfar, T.; Liberton, N.; Winters, H.A.H.; Leusink, F.K.J. Accuracy of computer-assisted surgery in mandibular reconstruction: A systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2018, 84, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, F.; Hanken, H.; Probst, F.; Schramm, A.; Heiland, M.; Cornelius, C.P. Multicenter study on the use of patient-specific CAD/CAM reconstruction plates for mandibular reconstruction. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2015, 10, 2035–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, L.; Marchetti, C.; Mazzoni, S.; Baldissara, P.; Gatto, M.R.A.; Cipriani, R.; Scotti, R.; Tarsitano, A. Accuracy of fibular sectioning and insertion into a rapid-prototyped bone plate, for mandibular reconstruction using CAD-CAM technology. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, T.; He, J.; Yu, C.; Zhao, W.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H. Utilization of a pre-bent plate-positioning surgical guide system in precise mandibular reconstruction with a free fibula flap. Oral Oncol. 2017, 75, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, D.H.; Mills, P.; Duszak, R., Jr.; Weisman, J.A.; Rybicki, F.J.; Woodard, P.K. Medical 3D printing cost-savings in orthopedic and maxillofacial surgery: Cost analysis of operating room time saved with 3D printed anatomic models and surgical guides. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodby, K.A.; Turin, S.; Jacobs, R.J.; Cruz, J.F.; Hassid, V.J.; Kolokythas, A.; Antony, A.K. Advances in oncologic head and neck reconstruction: Systematic review and future considerations of virtual surgical planning and computer aided design/computer aided modeling. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2014, 67, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepers, R.H.; Raghoebar, G.M.; Vissink, A.; Stenekes, M.W.; Kraeima, J.; Roodenburg, J.L.; Reintsema, H.; Witjes, M.J. Accuracy of fibula reconstruction using patient-specific CAD/CAM reconstruction plates and dental implants: A new modality for functional reconstruction of mandibular defects. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, S.; Marchetti, C.; Sgarzani, R.; Cipriani, R.; Scotti, R.; Ciocca, L. Prosthetically guided maxillofacial surgery: Evaluation of the accuracy of a surgical guide and custom-made bone plate in oncology patients after mandibular reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 131, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodrabum, N.; Tianrungroj, J.; Sinmaroeng, C.; Rudeejaroonrung, K.; Pavavongsak, K.; Puncreobutr, C. How is a cutting guide with additional anatomical references better in fibular-free flap mandibular reconstruction? a technical strategy. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2024, 35, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gaba, S.; Nair, S. A Novel Trapezoid Concept of Fibula Cutting Guide for Mandible Angle Reconstruction. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2021, 32, e513–e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Kang, S.-H. Precision of fibula positioning guide in mandibular reconstruction with a fibula graft. Head Face Med. 2016, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Kim, Y.C.; Han, S.J.; Jeong, W.S. Dual Application of Patient-Specific Occlusion-Based Positioning Guide and Fibular Cutting Guide for Accurate Reconstruction of Segmental Mandibular Defect. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2023, 34, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Li, B.; Xie, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Bai, S. Comparative study of three kinds of fibula cutting guides in reshaping fibula for the reconstruction of mandible: An accuracy simulation study in vitro. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrum, H.; Breik, O.; Koria, H.; Idle, M.; Praveen, P.; Martin, T.; Parmar, S. Novel in-house design for fibula cutting guide with detachable connecting arm for head and neck reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppen, C.; Verhoeven, T.; Snoeijink, T.; Weijs, W.; Verhulst, A.; van Rijssel, J.; Maal, T.; Dik, E. Fibula free flap reconstruction: Improving the accuracy of virtual surgical planning using titanium inserts. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 54, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Huan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, C.; Li, J. In Vitro Experimental Study of the Effect of Adjusting the Guide Sleeve Height and Using a Visual Direction-Indicating Guide on Implantation Accuracy. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numajiri, T.; Nakamura, H.; Sowa, Y.; Nishino, K. Low-cost design and manufacturing of surgical guides for mandibular reconstruction using a fibula. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosc, R.; Hersant, B.; Carloni, R.; Niddam, J.; Bouhassira, J.; De Kermadec, H.; Bequignon, E.; Wojcik, T.; Julieron, M.; Meningaud, J.-P. Mandibular reconstruction after cancer: An in-house approach to manufacturing cutting guides. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 46, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottini, M.; Jafari, S.S.; Shafighi, M.; Schaller, B. New approach for virtual surgical planning and mandibular reconstruction using a fibula free flap. Oral Oncol. 2016, 59, e6–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Jung, J.; Ohe, J.-Y.; Eun, Y.-G.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.-W. Computer-assisted preoperative simulations and 3D printed surgical guides enable safe and less-invasive mandibular segmental resection: Tailor-made mandibular resection. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baar, G.J.; Liberton, N.P.; Forouzanfar, T.; Winters, H.A.; Leusink, F.K. Accuracy of computer-assisted surgery in mandibular reconstruction: A postoperative evaluation guideline. Oral Oncol. 2019, 88, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Guide | N | Mean (mm) | SD | F (df1, df2) | p Value | Post Hoc †† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. DWG | vs. TFG | ||||||

| DFG | 80 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 121.91 (2, 237) | <0.001 † | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DWG | 80 | 0.39 | 0.16 | <0.001 | |||

| TFG | 80 | 0.49 | 0.14 | ||||

| Guide | N | Mean (°) | SD | F (df1, df2) | p Value | Post Hoc †† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. DWG | vs. TFG | ||||||

| DFG | 80 | 2.41 | 1.24 | 65.34 (2, 237) | <0.001 † | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DWG | 80 | 3.75 | 1.64 | <0.001 | |||

| TFG | 80 | 5.31 | 1.89 | ||||

| Guide | N | Mean | SD | F (df1, df2) | p Value | Post Hoc †† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. DWG | vs. TFG | ||||||

| DFG | 20 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 38.88 (2, 57) | <0.001 † | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DWG | 20 | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.39 | |||

| TFG | 20 | 0.72 | 0.08 | ||||

| Guide | N | Mean (°) | SD | F (df1, df2) | p Value | Post Hoc †† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. DWG | vs. TFG | ||||||

| DFG | 20 | 0.87 | 0.59 | 4.60 (2, 57) | <0.014 † | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| DWG | 20 | 1.70 | 0.88 | 0.79 | |||

| TFG | 20 | 1.62 | 1.28 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, B.-Y.; Jeen, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.-W. Enhanced Drilling Accuracy in Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap Using a Novel Drill-Fitting Hole Guide: A 3D Simulation-Based In Vitro Comparison with Conventional Guide Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413144

Hwang B-Y, Jeen C, Kim J, Lee J-W. Enhanced Drilling Accuracy in Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap Using a Novel Drill-Fitting Hole Guide: A 3D Simulation-Based In Vitro Comparison with Conventional Guide Systems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413144

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Bo-Yeon, Chandong Jeen, Junha Kim, and Jung-Woo Lee. 2025. "Enhanced Drilling Accuracy in Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap Using a Novel Drill-Fitting Hole Guide: A 3D Simulation-Based In Vitro Comparison with Conventional Guide Systems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413144

APA StyleHwang, B.-Y., Jeen, C., Kim, J., & Lee, J.-W. (2025). Enhanced Drilling Accuracy in Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap Using a Novel Drill-Fitting Hole Guide: A 3D Simulation-Based In Vitro Comparison with Conventional Guide Systems. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413144