1. Introduction

The use of structural adhesives in sheet metal joining methods is increasingly prevalent in automotive body manufacturing. Compared to traditional welding techniques, structural bonding offers several advantages, including enhanced rigidity, improved crash resistance, and better damping performance [

1] (Morano et al., 2019). Moreover, the application of structural adhesives in automotive body production provides numerous benefits, particularly in reducing vehicle weight and improving structural performance. Additionally, their applicability in areas with limited weld accessibility facilitates design flexibility and can consequently shorten production times [

2] (Lutz, 2017).

Adhesive bonding enables the joining of dissimilar materials such as ferrous metals, non-ferrous metals, and fiber-reinforced composites, offering advantages over conventional joining methods [

3] (Agha & Abu-Farha, 2021). This capability of structural adhesives is critical for modern multi-material vehicle designs that aim to optimize weight and performance [

4] (Satoh, 1996). Epoxy resin-based, heat-curing, single-component adhesives are particularly important in automotive body manufacturing due to their ability to bond various metallic and composite materials where elastic strength is a key requirement [

5] (Kowatz et al., 2023). In body-in-white (BIW) production, surface preparation is typically omitted prior to adhesive application, and curing is performed during the baking process following electrophoretic coating [

1] (Morano et al., 2019). Reducing vehicle body weight is a high priority in contemporary automotive manufacturing, leading to increased use of lightweight materials such as aluminum and fiber composites in conjunction with high-strength steels [

2] (Lutz, 2017). However, the strength of adhesive joints is significantly influenced by factors such as surface preparation procedures and thermal load cycles [

6] (Kłonica, 2018).

Optimizing the structural bonding process requires careful consideration of various factors, including material selection, surface preparation, adhesive application, and curing conditions. Selecting the appropriate type of adhesive for the materials being joined is of critical importance. The method of adhesive application must ensure uniform distribution across the bonding surfaces and adequate wetting of those surfaces. Controlling the curing process—primarily in terms of temperature, pressure, and time—is essential for achieving optimal adhesion properties [

7] (Stockinger et al., 2021).

Structural adhesives are well-suited for joining pre-formed components and can be used in conjunction with spot welding when necessary to construct a robust and lightweight vehicle body [

1] (Morano et al., 2019). In the automotive industry, the growing demand for lightweight materials such as aluminum and carbon fiber composites has heightened the significance of structural adhesives, primarily due to the challenges associated with welding these materials.

Agha and Abu-Farha (2021) proposed an experimental method comprising a custom-designed oven equipped with a three-dimensional digital image correlation system to investigate thermal stresses induced by curing and the residual stresses developed in materials bonded with structural adhesives used in automotive applications [

3]. Upon analyzing the force–shear stress curves of the specimens obtained through this method, they observed that samples with residual stresses exhibited higher stiffness compared to stress-free specimens, while their yield and fracture forces were lower than those of the unstressed counterparts.

Anyfantis and Tsouvalis (2009) experimentally investigated the effect of surface preparation on steel-to-steel adhesive bonding by comparing force–displacement and strain–displacement graphs for specimens prepared via sandblasting and grinding [

8]. Selective Laser Melting (SLM) is an additive manufacturing technology in which energy input is delivered via a laser beam into a powder bed. In this process, metal powders are uniformly distributed on the build platform using a powder spreader, and then scanned in the desired cross-sectional geometry by a laser beam directed through scanning mirrors. During scanning, the metal powders melt and subsequently solidify to form the corresponding layer of the part. The build platform then descends by one layer thickness, and the previous steps are repeated. This cycle continues until the part reaches its designated total height, resulting in a fully consolidated component on the build platform. The adhesive used was Araldite 2015, a two-component epoxy adhesive, applied at a thickness of 0.5 mm. A uniaxial static tensile test setup was employed at a pulling rate of 0.1 mm/min, and due to the significantly greater thickness of the steel sheets compared to the adhesive layer, plastic deformation in the sheets was considered negligible. The experimental results revealed that the difference in toughness and fracture loads between the two surface preparation methods was approximately 10%, indicating that sandblasted surfaces exhibited superior adhesion characteristics. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that doubling the surface roughness led to a 10% increase in the fracture load of the bonded joints.

Morano et al. (2019) [

1] conducted an experimental investigation into the bonding of steels using heat-applied adhesives commonly employed in automotive manufacturing. In the study, FeP04 steel sheets with a thickness of 1.2 mm were fabricated in a single-lap T-joint configuration, and the curing of the adhesives was performed using a typical thermal cycle representative of automotive production processes. Two adhesives were selected: Betamate 1060S, a single-component epoxy-based adhesive, and Versilok 265/254, a two-component epoxy-modified acrylic adhesive. Notably, Versilok 265/254 contains glass bead particles that help prevent slippage between bonded surfaces. No surface preparation was performed, and the adhesive layer was applied at a thickness of 0.2 mm. To examine the effects of aging, specimens were subjected to thermal cycling in a controlled-humidity environment ranging from −40 °C to 80 °C. Tensile tests were conducted at a rate of 1 mm/min, and tensile strain was measured using an extensometer. The results indicated that the average shear strength of the single-component epoxy adhesive was approximately 46% higher than that of the two-component adhesive, while its average fracture toughness was about 20% lower. Furthermore, when comparing aged and non-aged specimens, shear strength was observed to decrease by approximately 22% and 24% for the single- and two-component adhesives, respectively [

1].

Yu Sekiguchi and Chiaki Sato experimentally investigated the fracture behavior of joints bonded with structural acrylic adhesives under varying loading rates, focusing on the influence of adhesive thickness. In their study, the fracture resistance of specimens bonded with second-generation acrylic adhesives was measured using the double cantilever beam (DCB) test [

9]. The second-generation acrylic adhesive exhibited a highly ductile nature and left a white mark upon fracture, which enabled observation of the relationship between crack propagation and the plastic zone. Accordingly, the correlation between fracture energy and adhesive thickness was explained in terms of the plastically deformed area. The fracture energy increased from approximately 2 kJ/m

2 at 0.2 mm adhesive thickness to around 4 kJ/m

2 at 0.6 mm, and exceeded 8 kJ/m

2 with further thickness increase. The study also revealed that increasing the loading rate altered the fracture behavior. As the loading rate increased, unstable crack propagation was observed in thicker adhesive layers, and under impact loading conditions, all adhesive thicknesses exhibited a transition to stick–slip crack propagation. Furthermore, the reduction in the whitened zone associated with higher loading rates led to a decrease in the critical fracture energy during stick-slip crack growth [

9].

1.1. Application Equipment for Adhesives Used in Automotive Body Joining

Adhesive application can be performed either manually or robotically. In contemporary automotive manufacturing, robotic systems are increasingly preferred due to their superior standardization in terms of application speed, position, diameter, and bead length. The main components of adhesive dispensing equipment include the adhesive pump, metering unit, system control unit, and application guns.

The adhesive pump transfers the adhesive supplied in barrels either to the metering unit in robotic applications or directly to the application gun in manual operations. Pumps can be hydraulic or pneumatic, and heating functions may be integrated depending on application requirements. Adhesive pumps are available in single-barrel and dual-barrel configurations (

Figure 1). While dual-barrel systems minimize downtime during barrel replacement, they require more installation space [

10] (Atlas Copco, n.d.).

The metering unit stores the adhesive and delivers the required quantity to the application nozzle at an appropriate pressure. Adhesive is transferred from the pump via a hose, and the unit builds up the necessary pre-pressure for application. There are two types of metering units: mechanical and servo-driven. Servo units enable precise dispensing in robotic applications, synchronized with the robot’s movement speed, while mechanical units are typically hydraulic or pneumatic.

The system control unit comprises modules that allow adjustment of all parameters related to adhesive application in industrial environments. The application gun is the final component of the bonding system, responsible for dispensing the adhesive onto the part in the desired bead diameter. In robotic applications, camera systems are integrated to ensure that the presence, continuity, position, and diameter of the adhesive remain within specified tolerances. These systems are categorized into two types. The first type enables real-time monitoring, with a camera and lighting module mounted directly on the application gun and mechanically adjusted to focus on the nozzle. The second type involves post-process inspection, where an image of the part is captured after adhesive application and compared with a reference image to verify conformity. This approach introduces additional inspection cycle time, and depending on part dimensions, multiple cameras may be required [

11] (Isra Vision, n.d.). For these reasons, real-time camera monitoring is generally preferred.

1.2. Atmospheric Pressure Plasma (APP)

To enhance the adhesion between components, various surface preparation methods are employed prior to adhesive application. These methods include abrasion, laser surface treatment, chemical coating, and thermal processing. Although abrasion is a low-cost technique, it is challenging to apply on non-flat or geometrically complex surfaces. Chemical coating methods may pose environmental and health risks to operators. Laser surface treatment offers advantages in terms of process design; however, it remains underdeveloped for composite materials. Plasma treatment, on the other hand, is an environmentally friendly approach [

12] (Wei et al., 2024). As an innovative method, plasma facilitates stronger bonding between the adhesive and the substrate. It increases the surface activation energy, thereby promoting higher joint strength [

13] (Shin et al., 2022). Beyond these benefits, plasma treatment is also considered an environmentally friendly and energy-efficient approach [

14,

15]. Nevertheless, its effectiveness can be limited by the presence of heavy surface contaminants, and certain plasma types may induce localized oxidation or surface damage [

16]. Moreover, long-term durability under service conditions remains an open research question [

16]. These advantages and limitations highlight the relevance of comparing different plasma approaches for automotive steel bonding.

CAP surface treatment is a non-thermal, low-temperature ionized gas process conducted at atmospheric pressure using only ambient air. While electrons in the plasma reach high temperatures (10

4–10

5 K), the gas and ions remain near room temperature (≈300 K). This “non-equilibrium” plasma delivers reactive species—such as ions, radicals, and UV photons—to the substrate without significant bulk heating. When cold air plasma interacts with polymer or metal surfaces, it breaks C–C, C–H, or metal oxide bonds, thereby removing contaminants and weak boundary layers. It also generates polar functional groups (e.g., –OH, –C=O, –COOH in polymers; metal–O or –N bonds in metals). Through nanometer-scale etching and roughening, it increases the actual contact area. These combined effects enhance the surface free energy, promoting stronger adhesive and chemical bonding at the interface [

17] (Zoltán Károly et al., 2018). These mechanistic effects—bond scission, contaminant removal, functional group generation, and nanoscale roughening—collectively explain how plasma treatment enhances interfacial chemical properties and adhesion performance.

CAP has not yet been extensively covered in the literature compared to other plasma treatment methods. Initially developed for the pre-treatment of thermoplastic polymer materials, it continues to be primarily used in this domain. Although research has gradually expanded to explore its application in preparing metal surfaces prior to bonding, its investigation remains significantly more limited compared to its use with thermoplastic polymers [

18] (Williams et al., 2017).

In TAPP, high-power discharges such as plasma arcs are used, where electrons, ions, and neutrals are brought into equilibrium at elevated temperatures (1000–10,000 K). TAPP combines thermal energy with reactive species and locally heats the surface (150–300 °C), thereby enhancing chemical reactivity and diffusion processes. The high gas temperatures in TAPP enable deeper surface activation by facilitating subsurface diffusion of radicals. Abundant ions and metastable compounds promote extensive bond cleavage and cross-linking. Thermal activation accelerates the formation of oxide or nitride layers on metals and polar functional groups on polymers. The combined effect of thermal and plasma energy significantly increases the surface activation energy, improving both mechanical interlocking and chemical bonding [

19] (Yuji Ohkubo et al., 2021).

1.3. Motivation

Although plasma treatment has been explored to a limited extent for metal bonding, its application in preparing metal surfaces for automotive body joining represents an innovative approach. The objective of this study is to optimize the parameters of plasma-based surface preparation for structural adhesives used in automotive applications. Not only the type of plasma (TAPP or CAP), but also the application distance and duration will be examined in terms of their influence on adhesive strength. The curing process, which involves thermal treatment after adhesive application between components, promotes chemical bonding and enhances joint integrity. Therefore, to evaluate the effect of curing on adhesive strength and to determine optimal values in conjunction with plasma surface preparation, curing temperature and duration will also be considered as experimental parameters. The ultimate aim of this study is to contribute to the literature in this emerging field.

2. Materials and Methods

The Taguchi method, developed by Dr. Genichi Taguchi, provides a systematic approach to design optimization and quality control by minimizing variability through statistical tools [

20]. It employs orthogonal arrays to efficiently design experiments while reducing the number of trials required [

21,

22]. In this study, the Taguchi L18 orthogonal array was applied to define parameter sets and optimize adhesive bonding performance.

The curing process involves the transition of the adhesive from a liquid or semi-liquid state to a solid and stable form, and is essentially a chemical reaction influenced by factors such as temperature, duration, and the chemical composition of the adhesive [

23] (Sullivan & Peterman, 2023). The integration of structural adhesives into manufacturing processes—such as automotive body production—leverages existing production infrastructure and is efficient for high-volume assembly lines. However, this approach requires adhesives that are compatible with the specific temperature and time profiles dictated by the broader manufacturing process, which in turn affects the final mechanical properties and bond strength [

1] (Morano et al., 2019). Therefore, in selecting the parameters to be optimized, conventional curing temperatures and durations used in automotive sheet metal bonding processes were included. Additionally, to prepare the bonding surfaces prior to adhesive application, plasma type, plasma application distance, and the number of plasma passes over the specimen surface at constant traverse speed were incorporated as experimental parameters. The selected parameters and their corresponding levels were defined, and an experimental matrix was constructed using a suitable Taguchi orthogonal array.

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation Techniques

To evaluate the bonding strength of sheet metal components using structural adhesives, experimental specimens were prepared. The dimensions of the sheet metal samples were specified as 135 mm × 35 mm with a thickness of 1.2 mm (

Figure 2).

FeP04 steel was selected as the material for the sheet metal specimens due to its widespread use in outer body panels of automotive structures. The mechanical properties of the selected material are presented in

Table 1, based on the flat products catalog of Eregli Iron and Steel Works Co., Eregli, Turkiye [

24].

Henkel 4552 GB was selected as the structural adhesive for the experiment. This material is specifically formulated for bonding sheet metal components in automotive body structures and is commonly applied in the hem flange areas of vehicle doors within the automotive industry. The strength properties of this adhesive are presented in

Table 2, based on the technical data sheet published by Henkel AG & Co. KGaA [

25].

To ensure traceability of the experimental results, the test specimens were numbered (

Figure 3).

2.2. Implementation of the Experiment

In automotive body manufacturing, plasma-based surface preparation of sheet metal components prior to structural adhesive application represents an innovative approach not commonly employed in conventional production. This experimental study aims to investigate the effect of plasma treatment parameters on the bonding performance of sheet metals. In determining the parameters to be optimized, conventional curing temperatures and durations used in automotive sheet metal bonding processes were initially selected. Additionally, to prepare the bonding surfaces prior to adhesive application, plasma type, plasma application distance, and number of plasma passes were included as experimental variables. Surface preparation was conducted on the sheet metal specimens before adhesive application. To evaluate the influence of CAP and TAPP as experimental parameters, specimens treated with CAP and TAPP were prepared. CAP treatment was performed using the Relyon Piezobrush PZ3 device (Relyon GmbH, Regensburg, Germany) while TAPP treatment was carried out using the Relyon PlasmaTool (Relyon GmbH, Regensburg, Germany).

Based on the defined experimental parameter sets, surface preparation was completed using both TAPP and CAP methods, and curing was conducted at the specified temperatures and durations in accordance with the experimental design. The levels of the selected parameters are presented in

Table 3, comprising: plasma type—TAPP or CAP (P

1); curing time—20, 30, and 40 min (P

2); curing temperature—160, 180, and 200 °C (P

3); plasma application distance—1, 3, and 5 mm (P

4); and number of plasma passes (P

5), resulting in a total of 18 experimental groups. The curing time and temperature were determined based on the technical data sheet of the adhesive product, while the plasma application distances and number of plasma passes were referenced from the technical specifications of the plasma devices.

In this study, the L18 (2

1 3

4) orthogonal array was selected. Based on the experimental design constructed using the Taguchi L18 orthogonal series, a total of 54 experiments were planned across 18 experimental sets. The structure of this orthogonal array is presented in

Table 4.

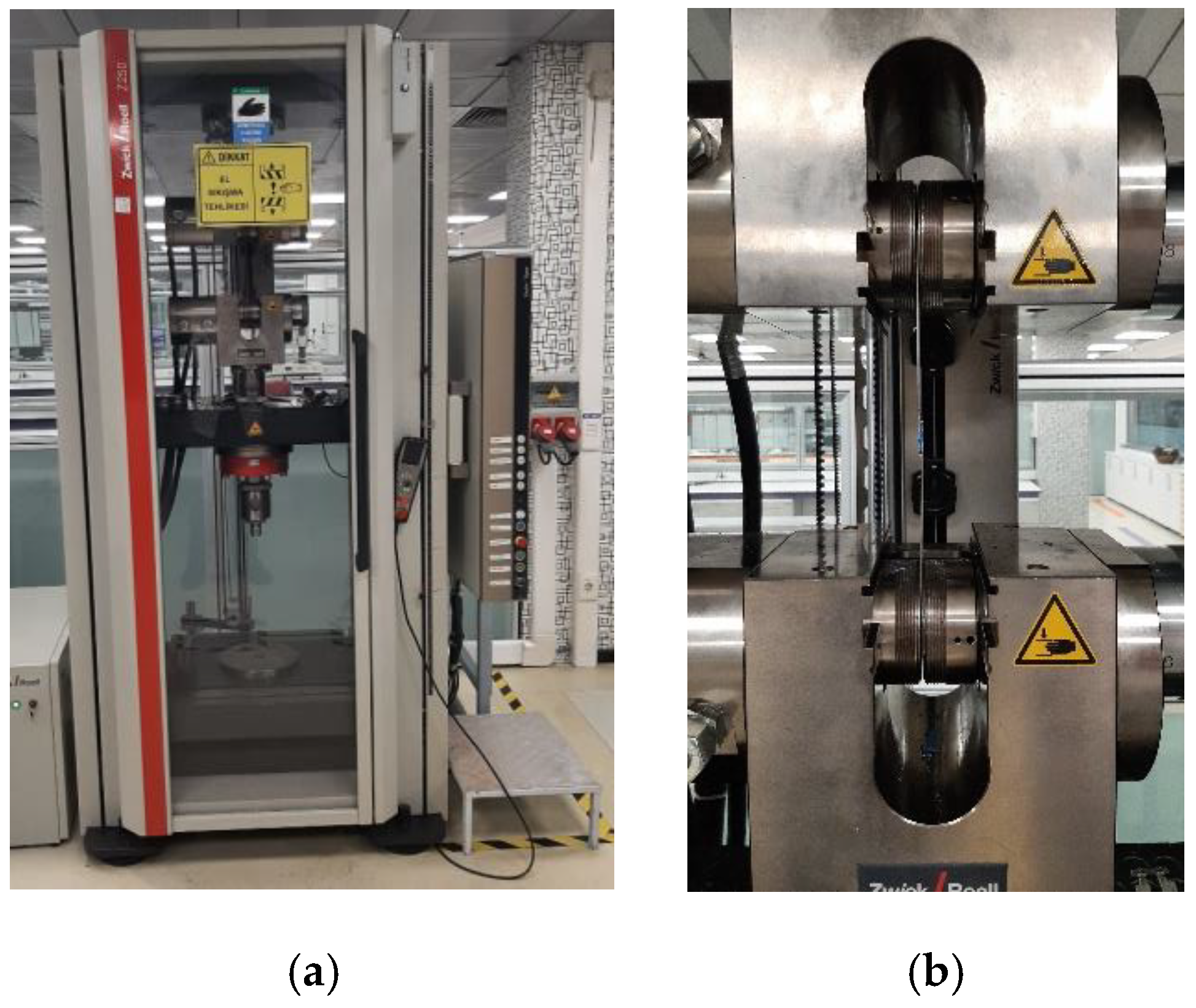

For each of the parameter sets defined in the experimental design, a total of 54 specimens (3 per each of the 18 Taguchi parameter combinations) were prepared by cutting sheet metal to the specified dimensions and applying either TAPP or CAP treatment. Following plasma treatment, adhesive was applied and the specimens were cured in an oven. Subsequently, the fracture loads of the prepared samples were measured using a Zwick/Roell Z250 tensile testing machine (Zwick/Roell GmbH, Ulm, Germany). The testing equipment and the specimen clamping configuration are shown in

Figure 4.

3. Results

3.1. Tensile Test Results

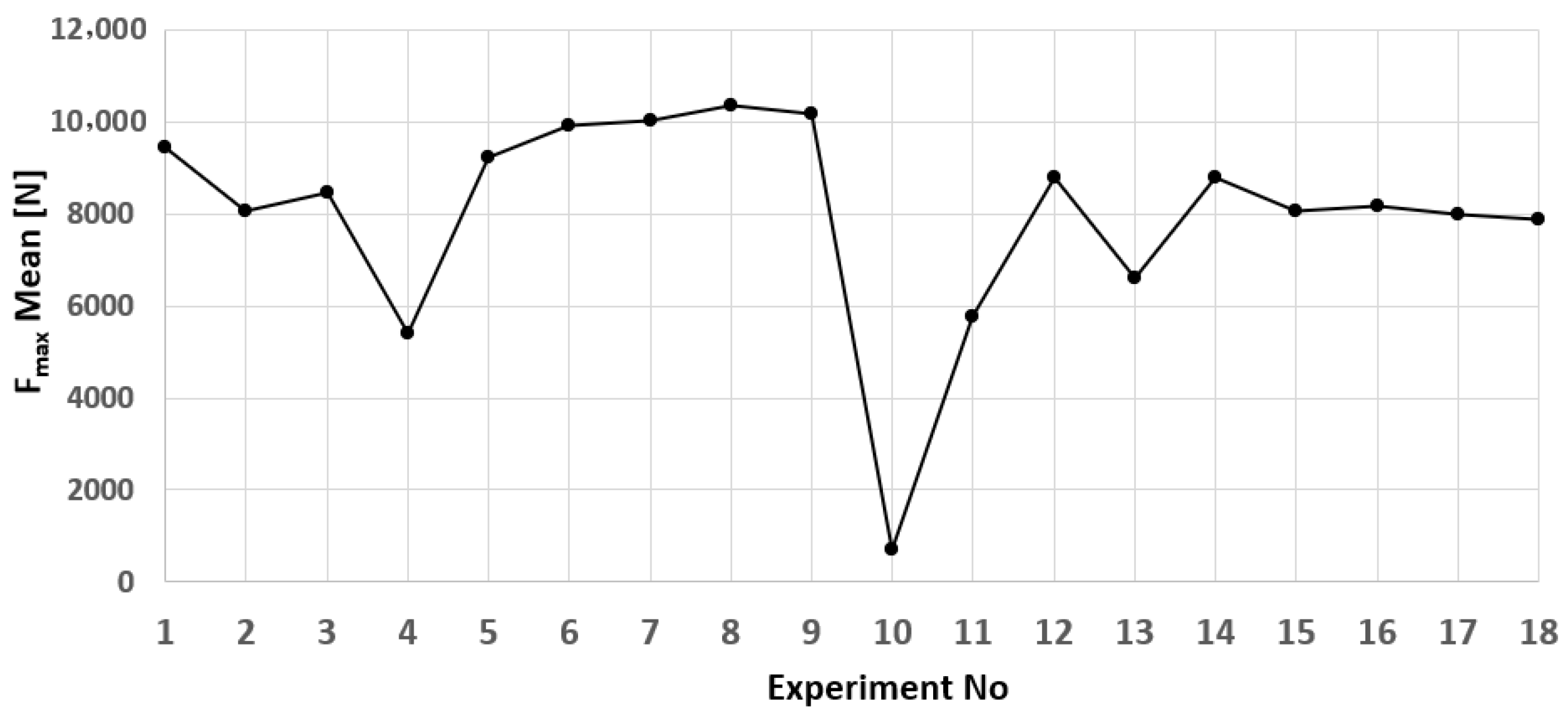

Tensile testing was conducted to evaluate the bonding strength of each specimen prepared according to the respective parameter sets, and the fracture loads were measured accordingly. The fracture loads obtained from the tensile tests, together with their average values, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV%), and the dominant failure modes observed, are presented in

Table 5. The classification of failure modes was carried out in accordance with ISO 10365:2022. [

26] A graphical representation of the fracture loads is provided in

Figure 5.

Among the test specimens, the highest fracture load was recorded for specimen No. 8, reaching 10,352 N. The process parameters associated with this result were a curing temperature of 180 °C, a curing duration of 40 min, and CAP applied from a 5 mm distance for in 2 passes. Additionally, specimens No. 7 and No. 9 exhibited fracture loads close to the maximum value. Notably, all three specimens—No. 7, 8, and 9—were treated with CAP and subjected to a curing time of 40 min, indicating a potential correlation between these parameters and enhanced bonding performance.

To illustrate the typical fracture characteristics observed in this study, representative images of selected experiments are presented below. These figures highlight both the best-performing samples and those with less favorable outcomes, providing visual support for the subsequent analysis.

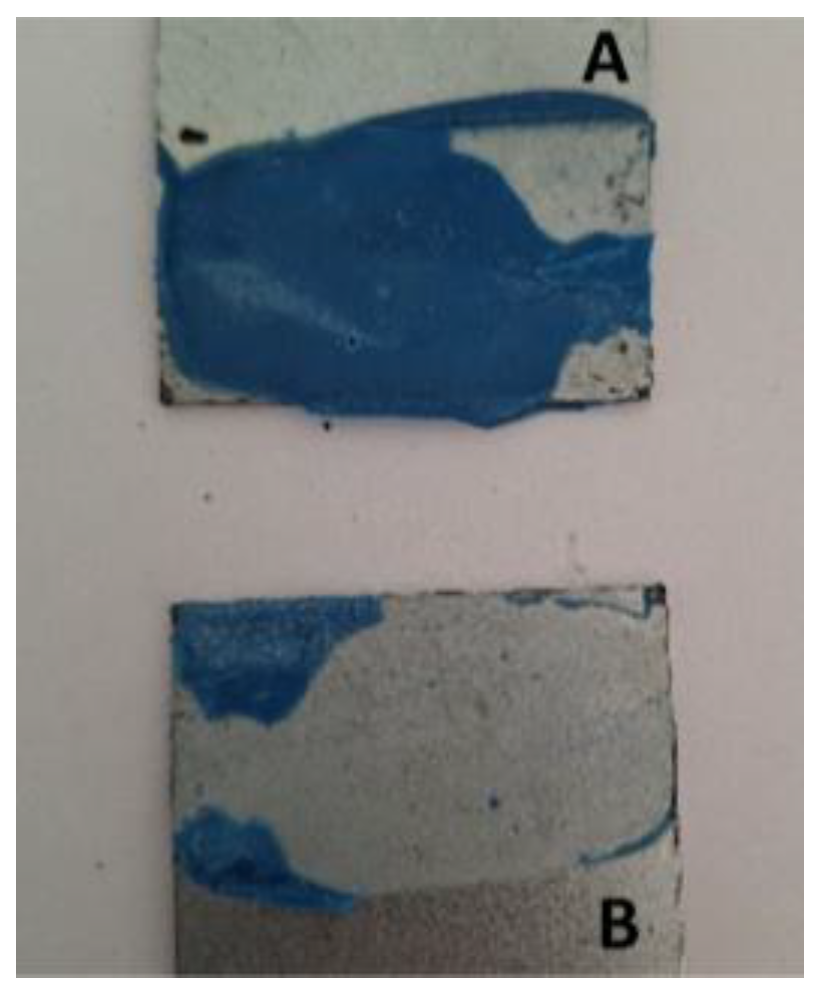

Experiment 10 showed extensive bare metal regions on both adherends, indicating adhesive failure. Adhesive residue was primarily located on Sheet A, with complementary voids on Sheet B. No cohesive fracture features were observed (

Figure 6).

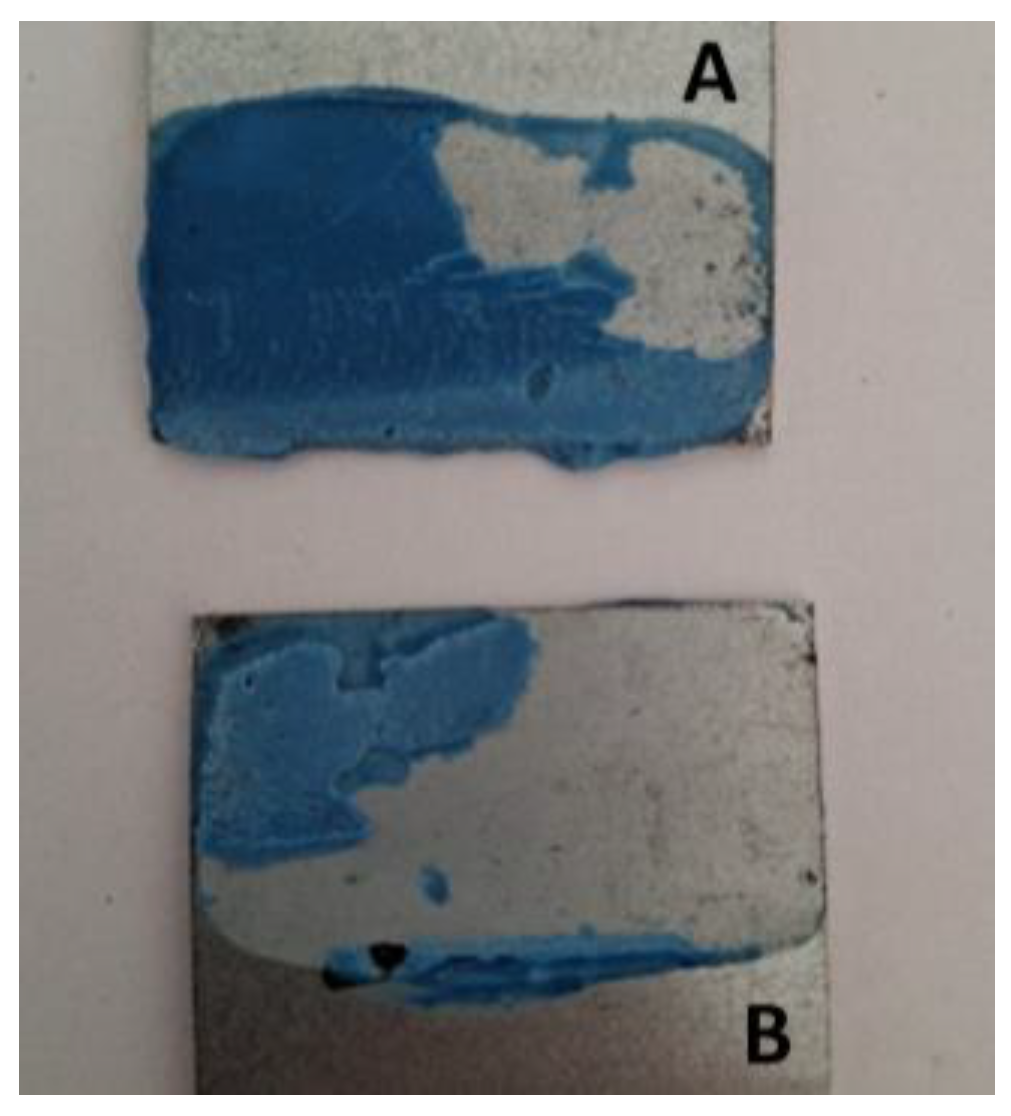

Experiments 7–9 exhibited cohesive-dominant failure with high adhesive coverage on both adherends. No bare metal regions were observed, and fracture surfaces were consistent across the group (

Figure 7).

Experiment 4 exhibited a mixed failure mode with patchy adhesive coverage and small bare substrate regions concentrated near the lower edge (

Figure 8).

Experiment 11 exhibited a mixed failure mode with partial adhesive coverage and widespread bare substrate regions, especially along the lower interface (

Figure 9).

Experiment 13 exhibited a mixed-to-adhesive failure mode with extensive bare substrate regions and limited cohesive residue, indicating weak interfacial bonding (

Figure 10).

The effect of APP on the adhesion performance of the specimens was also investigated within the scope of this study. For this purpose, in addition to the parameter set yielding the highest fracture load (Experiment No. 8), three further specimens were prepared under identical curing conditions (180 °C for 40 min) but without APP treatment. The tensile tests of these specimens resulted in an average fracture load of 10,056 N. For each group (

n = 3), mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV%) are reported in

Table 5 to summarize central tendency and dispersion. Given the limited sample size, formal significance testing was not performed; instead, variability was quantified using SD and CV%, and differences were interpreted in terms of practical effect relative to the untreated reference group.

3.2. Process Parameter Optimization for Adhesive Bonding

The experimental design results obtained in this study were analyzed using regression analysis in the Minitab 17 software, enabling the calculation of optimal parameter values. In constructing the regression model, the P1 parameter was defined as a categorical predictor, while P2, P3, P4, and P5 were treated as continuous predictors. The resulting model included first-order terms of the parameters, their second-order self-interactions, and second-order interactions between different parameters. Subsequently, four regression models were generated using the stepwise command: stepwise without elimination, forward elimination, backward elimination, and standard stepwise. Each model was evaluated and compared based on R2, adjusted R2 (R2 adj), and predicted R2 (R2 pred) values. The rationale for including R2 adj and R2 pred in the comparison—rather than relying solely on R2—is to avoid misinterpretation caused by the artificial inflation of R2 when statistically insignificant variables are added to the model. The analysis yielded R2, R2 adj, and R2 pred values of 100%, 100%, and 99.75%, respectively, indicating that the constructed regression model is highly successful and possesses strong generalization capability.

The regression equations derived for predicting fracture load following CAP and TAPP treatments are presented below.

Fracture Load Achieved via CAP:

Fracture Load Achieved via TAPP:

Using the “Response Optimizer” module in the Minitab 17 software, the optimal parameter values that maximize fracture load were calculated based on the lower and upper limits of the parameters presented in

Table 6. These parameters include plasma type (P

1), curing time (P

2), curing temperature (P

3), plasma application distance (P

4), and number of plasma passes (P

5).

The optimal values for the adhesive bonding process are presented in

Figure 8.

In the regression analysis performed with Minitab, categorical parameters were treated by assigning a fixed baseline level (‘Hold Value’), which serves as the reference category for comparison.

Based on the Taguchi analysis, the parameter combination yielding the maximum fracture load was identified, with the corresponding calculated F-value being 14,340 N. This optimal condition reflects the most effective balance of curing temperature, curing time, and plasma treatment parameters. The outcome indicates that CAP treatment, under these optimized conditions, provides superior bonding performance compared to other parameter sets. The optimization results are consistent with the observed cohesive failure modes, which confirm strong interfacial bonding under these conditions.

4. Discussion

This study focused on APP as a surface cleaning method. Although APP has been addressed only to a limited extent in the literature for metal bonding applications, its use in joining metal components in automotive body structures represents an innovative approach. The optimization of process parameters for structural adhesives used in automotive body manufacturing via plasma treatment was investigated. CAP and TAPP types, plasma application distance and duration, as well as the resulting fracture strength, were all examined in this study.

The curing process—essential for achieving improved chemical bonding—was included in the experiments alongside plasma surface preparation, involving the application of heat after adhesive deposition between components. Therefore, curing temperature and curing time were incorporated into the experimental design to determine optimal values. The Taguchi method was employed for experimental design, and regression analysis was used to derive equations for predicting fracture strength. Optimal parameter values were determined using the Response Optimizer module in Minitab.

The failure mode classification presented in

Table 5 provides further insight into the bonding performance of the investigated specimens. Experiments 7–9 predominantly exhibited cohesive failures, which are typically associated with strong interfacial bonding and superior mechanical performance. In contrast, Experiment 10 showed adhesive failure, reflecting insufficient surface activation and weak adhesion at the interface. Experiments 4 and 11 revealed mixed failure modes with adhesive features being dominant, indicating unstable bonding and localized stress concentrations that reduced overall strength. Experiment 13 displayed an adhesive-dominant mixed failure, characterized by extensive bare substrate regions and limited cohesive residue, which explains its relatively poor performance. These observations highlight the direct correlation between fracture behavior and fracture load, confirming that cohesive failures correspond to optimal bonding conditions, whereas adhesive or mixed failures are linked to inferior results.

It should be noted that Experiment No. 4 exhibited unusually high scatter among the three replicates, with fracture loads ranging from 3736 N to 8401 N. Such variation may be attributed to non-uniform adhesive application or slight misalignment during specimen gripping. While the mean value and associated SD and CV% are reported in

Table 5, this case highlights the limitations of reproducibility under the given laboratory conditions and should be interpreted with caution.

When compared with the reference specimens cured under identical conditions without plasma treatment, the application of APP increased the joint strength by approximately 3%. This improvement, although modest in magnitude, is consistent with previous studies reporting that plasma treatment enhances surface activation and wettability, thereby improving adhesive bonding performance. These findings indicate that APP can provide an additional contribution to bond strength even under optimized curing conditions, highlighting its potential as a complementary surface modification technique in adhesive joining applications.

The results of the study revealed that, under the identified optimal conditions, the CAP method yielded superior fracture resistance. Conventionally, it is expected that TAPP—due to its higher energy output—would produce stronger bonding effects. However, the experimental findings contradicted this expectation. The failure mode analysis further supports this outcome: cohesive failures were predominantly observed in CAP-treated specimens, whereas adhesive or mixed failures were more common in TAPP-treated specimens. This difference can be attributed to the fact that CAP treatment enhances the polar component of the surface energy without inducing thermal damage, thereby promoting stronger interfacial bonding. In contrast, the higher energy input of TAPP may cause localized oxidation or uneven surface modification of the steel substrate as suggested in previous studies (Kim et al., 2025) [

15], resulting in weaker adhesion unless significant contaminants are present on the surface. Although oxidation was not directly characterized in this study, the observed failure modes are consistent with such mechanisms It was concluded that CAP treatment led to more effective surface cleaning and enhanced the polar component of the surface energy, thereby improving adhesive bonding performance.

This interpretation is further supported by the optimization analysis presented in

Figure 11. which clearly demonstrates the superior performance of cold atmospheric plasma and its consistency with the observed failure modes.

This outcome, which is rarely emphasized in the literature, suggests that CAP may be more effective for bonding metal substrates. Nevertheless, this effectiveness is contingent upon the absence of high concentrations of surface contaminants such as oils. In cases where such contaminants are present, TAPP may offer superior bonding performance by actively removing these impurities from the surface.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides an applied comparison of CAP and TAPP treatments for adhesive bonding of automotive-grade steel substrates. CAP treatment consistently yielded superior fracture resistance compared to TAPP, with cohesive failures dominating under optimized conditions. This outcome highlights that CAP not only enhances the polar component of surface energy but also avoids detrimental thermal effects, thereby promoting stronger and more reliable interfacial bonding. In contrast, TAPP-treated specimens exhibited lower fracture loads and a higher incidence of adhesive or mixed failures. These results suggest that the higher energy input of TAPP may induce localized oxidation or uneven surface modification of the steel substrate, which can weaken adhesion unless significant contaminants are present. Thus, while TAPP may be advantageous in cases where heavy surface impurities must be removed, CAP offers a more effective and stable solution for clean or moderately contaminated steel surfaces.

A comparison between the optimal parameter set and the untreated condition revealed that CAP treatment provided higher fracture loads than the plasma-free case, thereby confirming its effectiveness for steel bonding. In contrast, TAPP did not achieve comparable improvement under the same conditions. The optimization analysis further supports these findings. The Taguchi-based approach identified the parameter set yielding the maximum predicted fracture load (14,340 N). This value represents a mathematically derived optimum rather than a directly measured experimental result. Experimentally, the highest fracture load obtained was 10,352 N, which, although lower than the predicted optimum, still reflects the superior performance of CAP-treated specimens. The consistency between the statistical prediction, the experimental trend, and the plasma-free comparison strengthens the conclusion that CAP provides the most effective bonding conditions for automotive steel substrates.

Overall, the applied comparison demonstrates that CAP treatment delivers clear advantages over TAPP in automotive adhesive bonding, both in terms of mechanical performance and failure mode behavior. These findings provide practical benefits for industrial applications, offering a reliable and energy-efficient method to improve joint quality in vehicle body manufacturing. Future research should extend this approach to other metallic substrates, investigate long-term durability under service conditions, and employ advanced surface characterization techniques such as Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), or contact angle measurements to further elucidate the mechanisms of plasma-induced adhesion.

Limitations

Although the present study demonstrates measurable improvements in bonding strength, a comprehensive economic cost–benefit analysis was not conducted. The actual investment required for plasma integration varies significantly with production line design, automation level, and product-specific requirements. Furthermore, the industrial relevance of a 3% improvement depends on whether the achieved strength is near the design tolerance limits. Such evaluations require production-scale data and will be considered in future research.

Another limitation of the present study is that advanced surface characterization techniques such SEM/EDS, XPS, or contact angle measurements were not performed. The scope was restricted to mechanical performance evaluation, and these analyses are suggested for future work to provide deeper insights into plasma-induced surface modifications.