1. Introduction

Digital Construction Management (DCM) represents a paradigm shift in how construction projects are planned, executed, and monitored, using digital technologies to enhance efficiency and communication across project lifecycles [

1,

2]. Project managers, site engineers, planners, and other professionals now heavily rely on computers to manage critical tasks such as scheduling, progress reporting, design coordination, and Building Information Modeling (BIM) activities [

3,

4,

5]. The integration of laptops into construction management practices, especially on-site in temporary offices or mobile workstations, has enhanced operational efficiency but has simultaneously introduced new occupational health concerns [

6,

7]. In dynamic environments, prolonged laptop use exposes users to awkward postures and repetitive stresses that contribute significantly to the development of Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs) including neck, shoulder, back, wrist, and finger pain, ultimately reducing productivity and increasing the risk of long-term disability [

8].

According to the World Health Organization (2019), MSDs affect 1.71 billion people globally and are the leading contributor to disability worldwide, accounting for 149 million disability-adjusted life years. The International Labour Organization (2019) reports that work-related MSDs constitute approximately 59% of all occupational diseases globally, with direct and indirect costs estimated at

$45–54 billion annually in the United States alone. In the construction sector specifically, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022) indicates that MSDs account for 31% of all nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses, while European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA, 2020) data shows that construction workers are 2.5 times more likely to develop work-related MSDs compared to workers in other industries. It is well-documented that MSDs represent 27.5% of nonfatal injuries in U.S. construction workplaces (Vijayakumar and Choi, 2022), and 59% occupational diseases are linked with MSDs (Chander, D.S.; Cavatorta, 2017). As construction workflows become increasingly digitized, it is imperative to recognize and address the ergonomic risks embedded within these emerging modes of operation [

9,

10].

Musculoskeletal Disorders represent a group of conditions that impair the muscles, bones, tendons, ligaments, and nerves, often resulting from chronic exposure to physical stresses such as static postures, repetitive motions, and forceful exertions [

11,

12]. Within the context of digital construction management, prolonged use of laptops without appropriate ergonomic accommodations results in sustained non-neutral postures, forward head tilt, hunched thorax, wrist flexion, and unsupported lower back, amplifying biomechanical stress across critical body regions [

13,

14].

To systematically identify and mitigate these risks, ergonomic assessment tools like the Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA) and the Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) are widely used [

15]. RULA focuses on the upper extremities including arms, wrists, and neck, while REBA provides a more holistic evaluation covering the entire body [

16]. Research using RULA, REBA, and surveys often centers on office environments and overlooks the unique ergonomic challenges faced by laptop users in transient construction settings. However, very few studies validate observational assessments through digital human modeling, leaving a significant gap in quantitative, simulation-based ergonomic analysis tailored to construction workflows. Complementing these observational tools, Digital Human Modeling (DHM) software such as HumanCAD

® (V6) enables precise simulation of biomechanical stress under various postural configurations, offering a quantitative validation of ergonomic assessments [

17]. Structured problem-solving approaches like the DMAIC methodology from Six Sigma are further employed to define, measure, analyze, improve, and control processes for continuous ergonomic optimization [

18,

19].

Existing research on ergonomics in construction has primarily focused on manual tasks performed by tradespeople, with limited attention to the growing population of professionals managing projects through digital interfaces [

20,

21]. Several notable studies have documented concerning trends regarding musculoskeletal health among construction management professionals, indicating higher rates of neck and shoulder pain among construction professionals who regularly use computers compared to field workers [

22]. Moreover, significant associations between computer use and musculoskeletal symptoms among construction management personnel are highlighted [

23]. Research has also established that the adoption of digital tools in construction has led to more sedentary work patterns among project managers [

24], with correlations between increased BIM usage and reports of work-related musculoskeletal disorders [

25].

The scope of ergonomic challenges in digital construction management extends across various professional roles and contexts, with evidence showing that job demands and workplace stress among construction managers are associated with increased prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders [

26]. Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of office ergonomics interventions in construction [

27], while highlighting the disconnect between advancing construction technologies and corresponding workplace health [

28]. While existing research establishes the presence of ergonomic issues in digital construction management, it typically relies on subjective assessment methods without employing validated ergonomic assessment tools, biomechanical analysis, and structured improvement methodologies, representing significant gaps that this research aims to address.

This research addresses these gaps by developing a hybrid framework that integrates RULA, REBA, and HumanCAD® simulations within a structured DMAIC methodology. Unlike prior studies confined to static office environments, it focuses on dynamic construction site conditions and proposes practical workstation improvements. By offering a validated, scalable approach, this study advances ergonomic sustainability in digital construction management, promoting healthier and more productive work environments.

3. Methodology

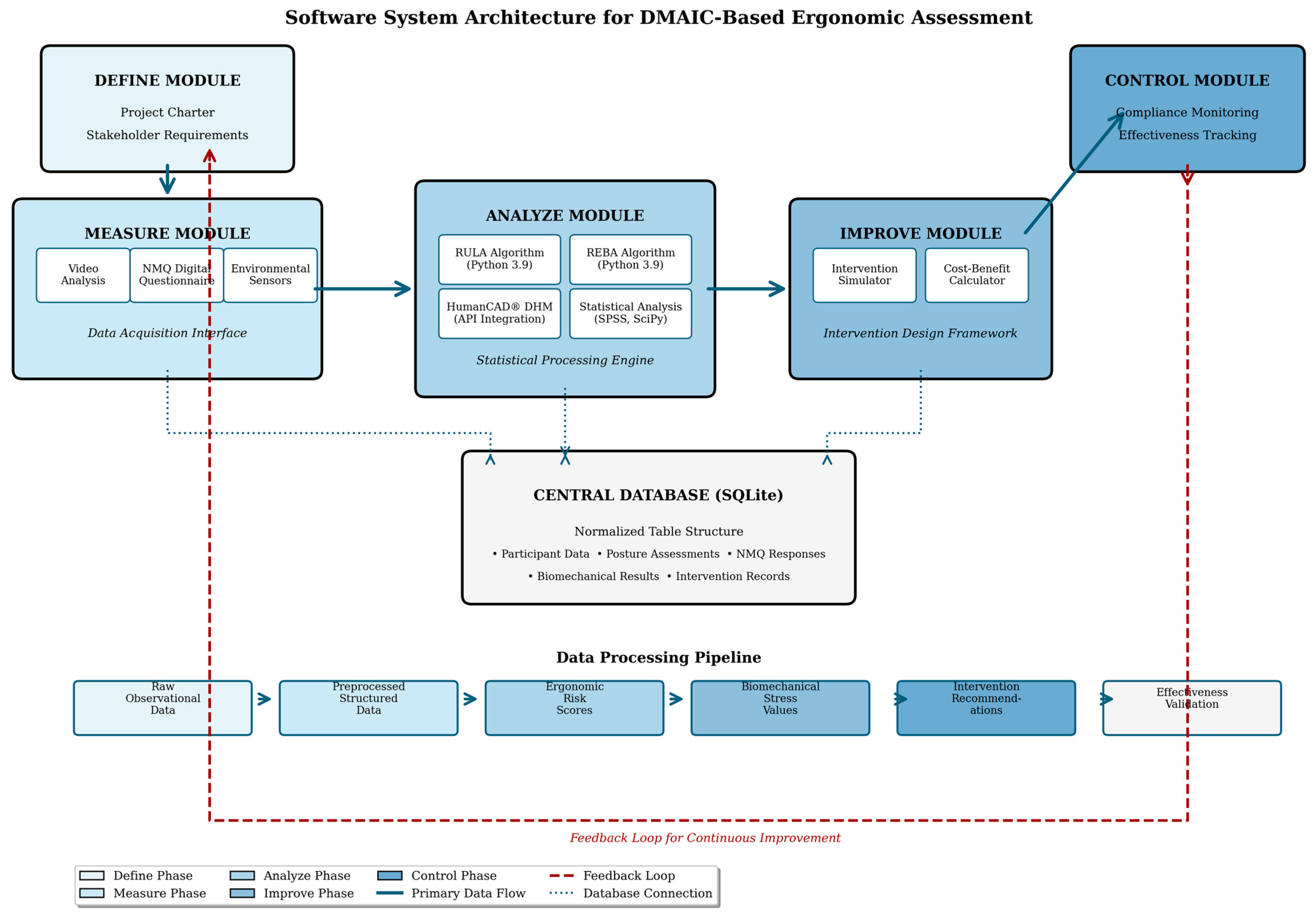

This research employed a comprehensive methodological approach integrating ergonomic assessment tools with biomechanical analysis and process improvement techniques to evaluate and address postural hazards in digital construction management contexts. The methodology followed a systematic framework based on the Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control (DMAIC) approach, as illustrated in

Figure 1, which provides structured progression from problem identification through solution implementation and validation.

The use of the DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) methodology, integrated with ergonomic tools such as RULA, REBA, and Digital Human Modeling (DHM), offers a systematic and evidence-based approach to identifying and mitigating ergonomic risks in industrial settings. This combination has been proven effective in diverse sectors, from automotive to manufacturing, for diagnosing postural risks and implementing corrective interventions [

29,

30]. Studies have validated that such integration not only enhances ergonomic assessment accuracy but also enables simulation-based redesigns that reduce musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) risks significantly [

31,

32,

33]. This methodology’s structured nature and proven track record across industries affirm its robustness and relevance for ergonomic problem-solving.

3.1. Research Design and Population

This study utilized a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative ergonomic assessments with qualitative observations to comprehensively capture the physical impacts of digital construction management activities. The target population consisted of construction management professionals who regularly use laptop computers and other digital devices to perform their work functions. Participants were involved from five construction firms of varying sizes in urban settings, representing diverse project types including commercial, residential, and infrastructure development. Selection criteria required participants to spend at least 60% of their working hours engaged with digital interfaces (mean daily usage: 6.8 ± 1.4 h) and have a minimum of one year of experience in their current role. A total of 160 participants were included in this study, comprising project managers (38%), site engineers (24%), BIM specialists (16%), construction estimators (12%), and project coordinators (10%), as summarized in

Figure 2. Demographics include 72% male and 28% female participants, with ages ranging from 24 to 58 years (mean age 37.6 years).

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

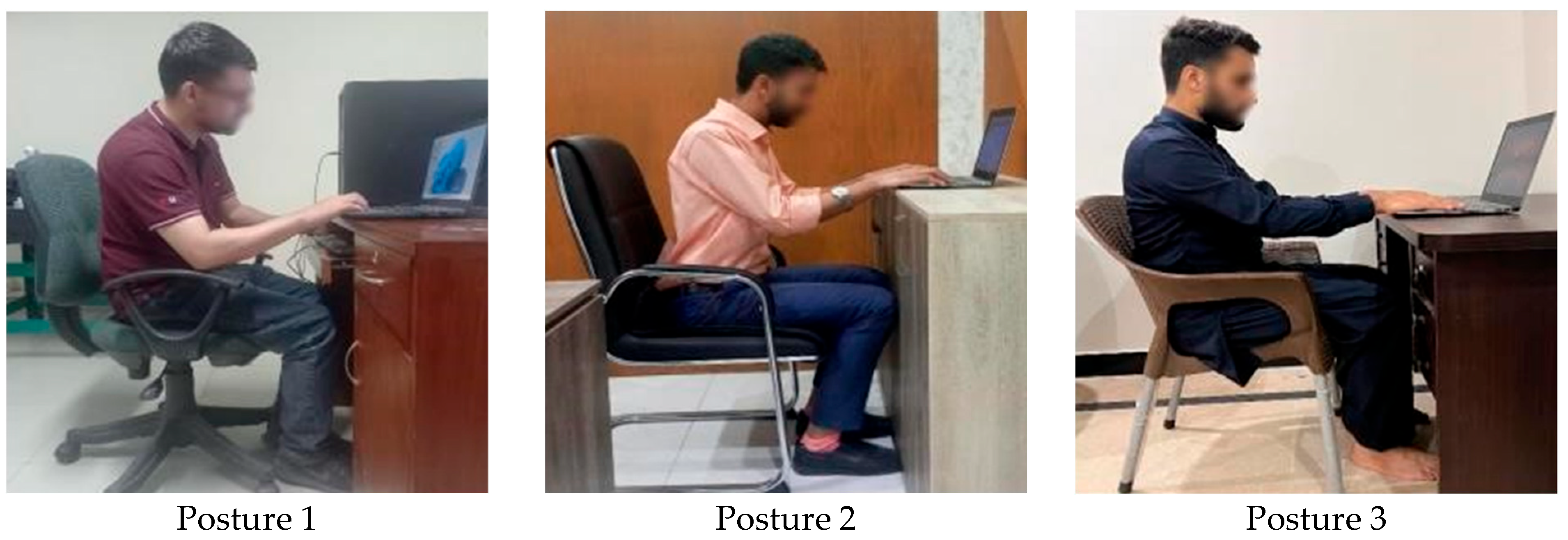

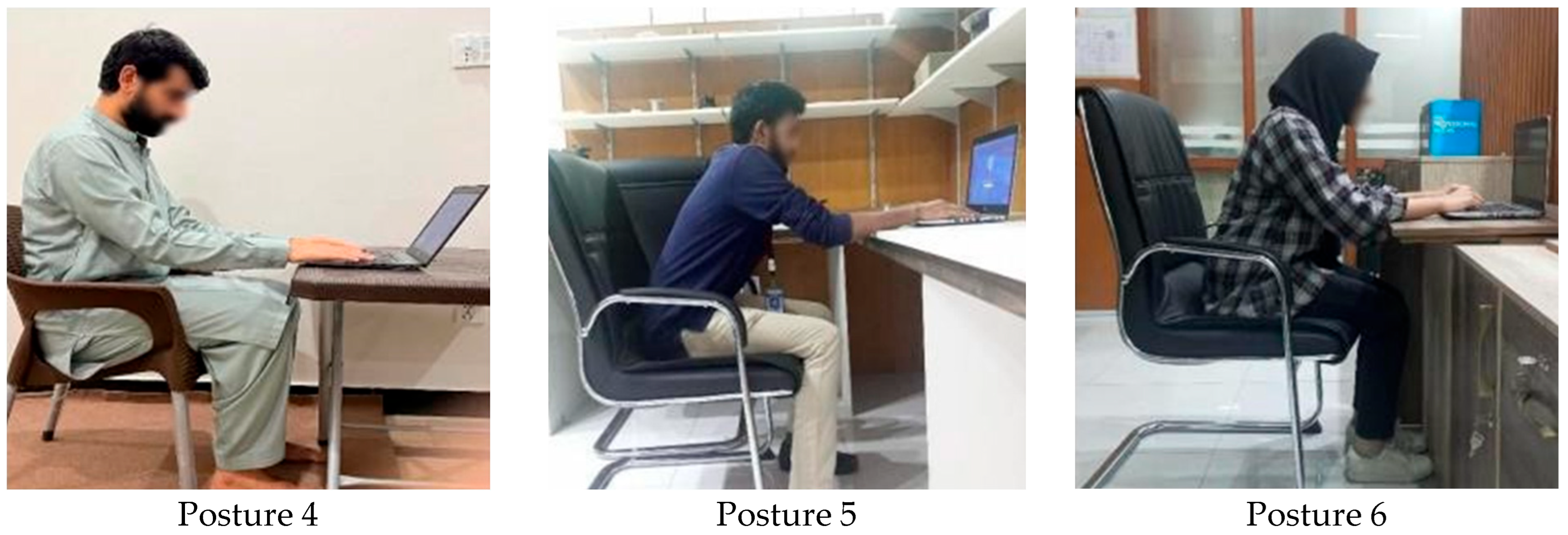

The data collection process was conducted across multiple environments where construction management professionals typically work, including permanent offices, temporary site facilities, and field locations. Each participant was observed during regular working activities for three sessions of 45 min each, scheduled to capture different times of day and work contexts. Video recordings of work postures were obtained with participant consent, supplemented by still photographs for posture assessment purposes, as shown in

Figure 3. The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) was administered to all participants to establish baseline prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms and their distribution across body regions. Environmental factors including workspace dimensions, furniture configuration, lighting conditions, and ambient noise levels were documented for each observation session to provide contextual data for analysis. Digital device usage patterns were tracked through a purpose-designed activity log where participants recorded task types, duration, and transition frequency between different digital interfaces.

3.3. Ergonomic Assessment Methods

3.3.1. Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA)

RULA evaluations were conducted for each participant based on video analysis of their most common working postures. This method specifically assesses upper body posture risk factors by assigning numerical scores to arm, wrist, neck, and trunk positions [

34]. The scoring system categorizes risk levels from 1 (negligible risk) to 7 (very high risk requiring immediate intervention). Three trained ergonomists independently evaluated each participant’s postures, with final scores determined by consensus to ensure reliability. Particular attention was given to neck flexion angles and wrist deviation during keyboard and mouse usage, as these represent high-risk factors identified in preliminary observations. RULA assessments were categorized by work location and task type to enable comparative analysis across different construction management contexts.

3.3.2. Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA)

REBA evaluations complemented RULA by providing comprehensive assessment of full-body posture, particularly valuable for field-based construction management activities where lower body positioning varies significantly from office environments. The REBA protocol assigns scores to neck, trunk, legs, upper arms, lower arms, and wrists, incorporating load/force and coupling quality factors. The resultant scores range from 1 (negligible risk) to 15 (very high risk requiring immediate action). REBA assessments were particularly valuable for evaluating temporary workstation setups and impromptu field working positions where non-standard furniture configurations were observed [

35]. Inter-rater reliability was established through independent scoring by multiple ergonomists with subsequent consensus discussion.

3.3.3. Biomechanical Analysis Using Digital Human Modeling

To validate and quantify observational findings, Digital Human Modeling was employed using HumanCAD version 8.2. DHM models were configured based on measured participant anthropometrics [

36,

37]: male participants (

n = 115) mean height 173.4 ± 7.2 cm (range: 158–189 cm), weight 76.3 ± 9.8 kg (range: 58–102 kg); female participants (

n = 45) mean height 160.2 ± 5.8 cm (range: 149–174 cm), weight 62.1 ± 8.4 kg (range: 48–84 kg). Three representative models (5th, 50th, 95th percentile) were created for each gender from ANSUR II database, adjusted to match participant distribution. Each participant was assigned to nearest percentile model based on Euclidean distance in anthropometric space.

Six representative postures were identified from video analysis. Anatomical landmarks (acromion process, lateral epicondyle, ulnar styloid process, greater trochanter, lateral femoral condyle, lateral malleolus) were digitally marked using Kinovea v0.9.5. Three-dimensional joint angles were calculated using coordinate transformation. For any joint, vectors v1 (proximal segment) and v2 (distal segment) were defined from anatomical landmarks. Joint angle θ was computed using: θ = arccos ((v1·v2)/(||v1|| ||v2||)), where v1·v2 represents the dot product and ||v|| represents vector magnitude. Validation of DHM-predicted versus video-measured angles showed strong agreement (ICC = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.91–0.96).

Postures were replicated in HumanCAD with ±1° precision. Inverse dynamics analysis calculated joint reaction forces and moments under quasi-static equilibrium assumptions (negligible acceleration, forces and moments balanced at each joint). Gravitational loading was applied based on model anthropometry. External forces (keyboard: 1.5–2.0 N, mouse: 2.5–3.5 N) were incorporated from literature. Note: HumanCAD v6 employs inverse dynamics without muscle force prediction algorithms; joint loads represent net reaction forces and moments. Biomechanical stress ratios compared joint torques in observed postures against neutral reference (ISO 11226:2000). Eight body regions were analyzed: cervical spine (C7/T1), thoracic spine (T8/T9), lumbar spine (L5/S1), shoulders (glenohumeral), elbows, wrists (radiocarpal), hips, knees. Output parameters included compressive forces (N), shear forces (N), and moments (N·m), compared against NIOSH thresholds.

3.4. Process Improvement Methodology

The DMAIC methodology structured the overall research approach, beginning with problem definition through baseline measurement and progressing to analysis, improvement, and control phases. In the Define phase, the problem scope was established through stakeholder interviews and preliminary observations, culminating in a comprehensive project charter. The Measure phase involved systematic data collection using RULA, REBA, and the Nordic Questionnaire to establish baseline ergonomic risk levels. The Analyze phase employed statistical analysis of the assessment results alongside fishbone diagramming and root cause analysis to identify primary ergonomic risk factors. The Improve phase developed tailored interventions including workstation redesign specifications and ergonomic guidelines specific to construction management contexts. Finally, the Control phase implemented sustainable solutions with verification protocols to ensure long-term effectiveness.

Data Preprocessing Protocol: Raw data underwent five-stage preprocessing. Stage 1: Data validation checked completeness, logical consistency, video timestamp cross-referencing, and RULA/REBA score verification. Stage 2: Missing data (<3% across variables) handled via multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE) for quantitative variables; mode imputation for categorical variables when missing <5%. Stage 3: Outlier detection via Mahalanobis distance (χ2 threshold, p < 0.001) and box plots identified three extreme outliers in task duration, which were winsorized to 95th percentile. Stage 4: Normality assessment via Shapiro–Wilk tests (RULA: p = 0.023, REBA: p = 0.031) supplemented with Q-Q plots indicated moderate departure, leading to both parametric and non-parametric test application. Stage 5: Data transformation applied log transformation to biomechanical stress ratios (pre-transformation skewness: 1.8; post-transformation: 0.3); RULA/REBA scores analyzed on original ordinal scale to preserve interpretability.

3.5. Data Analysis Techniques

Quantitative data from RULA, REBA, and biomechanical stress analysis underwent descriptive statistical analysis to determine average risk levels and their distribution across different body regions, work locations, and task types. One-way ANOVA was employed to identify significant relationships between ergonomic risk factors and variables including task duration, work environment type, and participant demographics. Correlation analysis explored relationships between NMQ-reported symptoms and objective risk assessment scores. For biomechanical data, stress ratios for each body region were calculated by comparing torques in observed postures against neutral reference postures, with values exceeding 1.0 indicating increased biomechanical stress. Root cause analysis techniques including 5-Whys and fishbone diagrams were applied to identify primary contributors to ergonomic risks, subsequently verified through focused observations. The root cause analysis incorporated multiple data sources including systematic observations documented during ergonomic assessments, structured interviews with participants regarding workplace constraints and behavioral factors, and environmental condition records from permanent offices, temporary site facilities, and field locations. Solution effectiveness was validated through before-and-after comparison of risk assessment scores and participant feedback.

3.6. Computational Implementation and Algorithmic Frameworks

3.6.1. System Architecture

This research employed an integrated system implementing DMAIC methodology as an executable framework as shown in

Figure 4. The system comprises five modules: Define Module (project charter management), Measure Module (data acquisition from video analysis, NMQ questionnaires, environmental sensors), Analyze Module (RULA/REBA algorithms, DHM integration, statistical processing), Improve Module (intervention simulation, cost–benefit analysis), and Control Module (compliance monitoring).

3.6.2. Algorithmic Specifications

The RULA and REBA scoring procedures were implemented as computational algorithms to ensure consistent, reproducible assessment across all participants and observation sessions.

Table 1 presents the RULA scoring algorithm, which processes postural observation data to generate risk scores and action level recommendations.

Table 2 presents the REBA scoring algorithm for comprehensive full-body assessment.

Table 3 presents the statistical analysis workflow algorithm implementing data preprocessing, normality testing, correlation analysis, ANOVA, and intervention effectiveness evaluation. These algorithms were implemented in Python 3.9 with input validation, error handling, and logging functionality to ensure robust operation during large-scale data processing.

INPUT: Posture observation data P = {arm, forearm, wrist, neck, trunk}

OUTPUT: RULA score (1–7) and action level (1–4)

INPUT: Full body posture data P = {neck, trunk, legs, upperArm, lowerArm, wrist}

OUTPUT: REBA score (1–15) and risk level classification

INPUT: Raw assessment data D = {RULA_scores, REBA_scores, NMQ_responses, biomechanical_data}

OUTPUT: Statistical results R = {descriptives, correlations, ANOVA_results, effect_sizes}

3.6.3. Experimental Environment and Reproducibility

Hardware: Dell Precision 7920 workstation with dual Intel Xeon Gold 6238R (2.2 GHz, 28 cores), 64 GB DDR4 ECC RAM (2933 MHz), NVIDIA Quadro RTX 4000 (8 GB GDDR6), 1 TB NVMe SSD.

Software: Windows 10 Enterprise (Build 19044, 64-bit), HumanCAD v6 (Nexgen Ergonomics Inc., Pointe Claire, QC, Canada), IBM SPSS Statistics v28.0.1.1, Python 3.9.7 with NumPy v1.21.2, SciPy v1.7.1, Pandas v1.3.3, Matplotlib v3.4.3, Seaborn v0.11.2, Kinovea v0.9.5, Microsoft Excel 2019.

HumanCAD Configuration: ANSUR II (2012) anthropometric database. Male models: 5th percentile (H: 164.5 cm, W: 62.3 kg), 50th percentile (H: 175.6 cm, W: 81.6 kg), 95th percentile (H: 185.4 cm, W: 103.2 kg). Female models: 5th percentile (H: 151.9 cm, W: 51.8 kg), 50th percentile (H: 162.6 cm, W: 70.3 kg), 95th percentile (H: 172.9 cm, W: 94.3 kg). Joint constraints: anatomically accurate ROM limits. Posture resolution: 1° angular precision. Computation: quasi-static equilibrium analysis.

Data Formats: Raw video (MP4, 1920 × 1080, 30 fps), posture data (CSV), NMQ responses (SQLite database), statistical results (JSON), HumanCAD models (native .HCD with CSV exports).

3.7. Ethical Considerations

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and following ethical guidelines for human subjects research. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, Pakistan (Ethics Committee Reference Number: NUST-IRB-2023-047).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in this study. The informed consent process included explanation of study objectives, data collection procedures including video recording and photography, voluntary participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without consequence. All participants provided explicit written consent for observation during work activities, video recording and photography for posture assessment, completion of musculoskeletal questionnaires, and use of anonymized data for research publication.

Data confidentiality was maintained by assigning numerical identifiers to participants, with personally identifiable information stored separately from research data. Video and photographic data were securely stored and accessed only by research team members for assessment purposes. Participation was voluntary, and observation sessions were scheduled to accommodate participants’ work requirements to minimize disruption.

5. Discussion

This study reinforces a growing body of evidence highlighting the ergonomic risks associated with digital work in the construction sector, particularly among professionals such as BIM specialists, project managers, and site engineers. The findings expand on prior research by offering a validated hybrid methodology using RULA, REBA, and Digital Human Modeling (DHM) while also implementing structured ergonomic interventions grounded in the DMAIC framework.

The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among digital construction professionals in this study aligns with established ergonomic research across the broader construction sector. Studies have consistently documented high rates of discomfort in the neck, back, and upper limbs due to poor posture and prolonged static activities [

38,

39,

40]. However, these studies primarily focus on manual laborers. This study uniquely targets digital professionals operating in transient and dynamic environments, thus addressing a notable research gap identified by reviews of ergonomic risk assessment trends in construction safety management [

41].

Furthermore, the use of biomechanical modeling in this study to quantify stress ratios in different body regions advances beyond subjective or observational-only techniques that dominate the field [

42,

43]. These quantitative insights revealed critical risk levels in the thoracic and cervical regions, underscoring the limitations of standard office-centric ergonomic guidelines when applied in construction field conditions.

The ergonomic interventions implemented, particularly the use of adjustable laptop stands and external input devices, demonstrated significant improvements in RULA and REBA scores, far outperforming standalone training modules. This pattern is in line with the findings from prior interventions in the construction sector where physical modifications produced more consistent risk reductions than educational strategies alone [

44,

45]. Similarly, training was found to be only partially effective unless coupled with organizational support and ergonomic redesign, reinforcing findings of this study.

This study also supports conclusions that ergonomic success depends on environmental adaptability and organizational commitment [

46,

47]. Implementation challenges in field settings due to space and equipment constraints also mirror difficulties reported in earlier participatory ergonomics projects [

48,

49].

The implications of this study extend beyond individual health outcomes. MSDs among digital construction managers affect not only worker well-being but also productivity, continuity of operations, and ultimately project performance. Ergonomic discomfort may contribute to decision fatigue, increased absenteeism, and reduced coordination efficiency, critical issues in digitally managed construction projects.

From a policy standpoint, the findings advocate for the integration of ergonomic risk assessments into construction safety management systems and procurement standards. Portable ergonomic equipment and construction-specific digital work protocols should become baseline requirements, not optional add-ons. Moreover, regulatory frameworks must evolve to recognize digital task ergonomics as a legitimate occupational health concern within construction, a shift currently lacking in many national safety codes [

50,

51].

6. Limitations and Recommendations

This study has limitations worth noting. The three-month follow-up provides initial effectiveness data but insufficient insight into long-term sustainability, as MSDs develop over years and behavioral compliance may decline. Future research should include 12–24 month follow-up assessments. Sample limitations include restriction to five medium-to-large urban Pakistani firms, potentially limiting generalizability across different geographic contexts, firm sizes, project types, and workforce demographics. Methodologically, this study focused primarily on physical ergonomics with limited exploration of cognitive (mental workload, decision-making) and organizational (work structure, management) factors. Observational methods involve subjective posture categorization and may miss dynamic variations. Intervention compliance varied substantially (permanent offices: 92%, temporary sites: 78%, field: 63%), indicating practical implementation barriers requiring further investigation. This study evaluated laptop/desktop ergonomics but did not address emerging technologies (AR headsets, tablets, wearables) that introduce novel challenges.

7. Conclusions

This research addressed occupational health risks from digital transformation in construction management through systematic integration of RULA, REBA, DHM, and DMAIC methodology, documenting significant risks and demonstrating substantial risk reduction.

Principal Findings: 87.5% MSD prevalence (76.2% neck, 59.4% back) establishes digital work as a new occupational health challenge. Quantified biomechanical stress (thoracic: 9.7× neutral; neck: 3.1× neutral) provides objective evidence of strain magnitude. Environment-dependent differentials (temporary sites: 25% higher REBA; field: 38% higher) demonstrate construction-specific amplification beyond standard offices. Intervention effectiveness (34% RULA, 33% REBA, 46% symptom reduction, p < 0.001) proves systematic interventions substantially mitigate risks. Differential effectiveness (adjustable equipment: 44.7% vs. training: 8.5%) guides resource allocation prioritizing portable, adjustable equipment.

Theoretical Contributions: This research advances human factors engineering by demonstrating necessity of context-specific frameworks accounting for industry constraints. Integration of RULA/REBA with DHM validates complementary value, offering methodological template for dynamic occupational contexts. DMAIC operationalization as construction-implementable framework bridges construction management, industrial engineering, and occupational health disciplines.

Practical and Policy Implications: This study provides validated, scalable framework adaptable to organizational diversity while maintaining rigor. Break-even periods (3.2–5.7 months) offer economic justification addressing adoption barriers. Proactive ergonomic management integrated with digital transformation supports workforce sustainability and skill retention, preserving human capital investments. For policymakers, this research demonstrates gaps in current standards lacking guidance for digital construction professionals. Developed guidelines (

Table 6) provide foundation for industry standards addressing temporary workplaces, mobile devices, and environment-adaptive practices.

Broader Significance: Implications extend to other industries with mobile knowledge work (field engineering, mobile healthcare, emergency response, natural resource management) sharing variable locations, temporary infrastructure, and environmental constraints. This study demonstrates digital tools introduce significant ergonomic risks requiring systematic health impact assessment concurrent with technology deployment, establishing ergonomics as integral to implementation rather than remedial afterthought.