1. Introduction

Significant transformations marked the evolution of software architecture since the introduction of early computing systems. In particular, web application architecture has suffered major structural changes. The deployment of a single, monolithic application instance in a production environment is used less and less. Traditional monolithic systems have gradually evolved into modular monoliths and, more recently, into microservice-based architectures. Deploying applications on physical hardware has been replaced with the usage of virtual machines and containerized environments, with orchestrators such as Kubernetes increasingly dominating the deployment landscape.

These architectural and infrastructural changes have emerged under the influence of growing demands in a digitalized and globalized world. Limitations in scalability and latency prohibit the use of single servers for large, geographically distributed users. The emergence of cloud service providers—such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Platform, and Microsoft Azure—has also favored this transformation by enabling the deployment of scalable, fault-tolerant, and globally available applications with minimal investment. Consequently, the management of the infrastructure is now frequently delegated to cloud platforms to reduce operational burden on development teams.

Modern deployments commonly consist of hundreds or even thousands of individual services. For example, as of 2024, the multinational mobility company Bolt reported operating more than 1000 services in its production environment [

1]. Working in such complex ecosystems without sufficient monitoring can lead to service degradation or systemic failure, often resulting in financial losses and diminished user satisfaction. This operational fragility has led to the increasing prominence of observability as a critical aspect of software system management.

The scientific novelty of this work lies in the introduction of a unified analysis framework that evaluates exporters across heterogeneous storage and messaging systems—RabbitMQ (

https://www.rabbitmq.com, accessed 25 October 2025), SQL databases, and Cassandra (

https://cassandra.apache.org/_/index.html, accessed 25 October 2025)—using a consistent experimental methodology and identical workload patterns. Existing metrics frameworks, such as Prometheus exporters or vendor-specific collectors, typically document platform-dependent behaviors, but they do not provide a cross-technology comparison based on controlled, reproducible experiments. By contrast, our approach establishes a uniform basis for quantifying exporter performance, identifying bottlenecks, and comparing architectural trade-offs across fundamentally different persistence layers. This contributes new knowledge on how internal storage mechanisms and network I/O patterns impact exporter throughput and resource usage.

While traditional metrics frameworks primarily focus on metrics exposition and scraping mechanics, they rarely offer insights into how exporter implementations interact with underlying data stores under realistic load. Our study extends prior work by systematically relating exporter behavior to the intrinsic performance characteristics of the target storage systems and by identifying conditions under which standard exporter designs degrade.

To formalize our evaluation, we adopt the following experimental hypothesis: the performance of a metrics exporter is bounded not only by its implementation but also by the architectural properties and operational constraints of the underlying storage system it targets. This hypothesis drives the design of our experiments and guides the interpretation of results.

Observability tools, such as Prometheus (

https://prometheus.io, accessed 10 October 2025) and Grafana (

https://grafana.com, accessed 10 October 2025), are now essential components in contemporary software development workflows. These tools allow the collection, visualization, and analysis of system metrics, while also providing alerting mechanisms that notify operators of potential anomalies. Industry surveys, such as the ones conducted by Grafana Labs, emphasize the importance of observability [

2,

3,

4], identifying it as one of the most rapidly expanding trends in software engineering. Distributed systems grow in complexity, with the effect of a higher demand for comprehensive visibility into system behavior, as undetected faults and inefficiencies can propagate and amplify across service boundaries.

Another factor supporting the adoption of observability practices is the economic model employed by cloud infrastructure providers. Using Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), users are billed based on their actual consumption. Consequently, performance optimizations in cloud-hosted applications can save direct costs, especially as data processing and user interactions are increasing.

The same industry surveys [

2,

3,

4] highlight a strong preference for open-source solutions in observability stacks. However, they also reveal that system complexity and maintenance pose many challenges. Horizontal scaling—adding more resources to handle increased load rather than upgrading individual machines—strongly supports the capabilities of cloud platforms. Selecting and applying the software development methodology plays an important role [

5], while distributed systems improve scalability and fault tolerance, but also reduce latency by bringing services geographically closer to users.

Performance optimization in distributed environments can lower system resource consumption and strongly reduce operational overhead. However, optimization efforts should be driven by analysis rather than intuition. Developers should adopt a scientific approach by establishing baseline performance metrics and evaluating changes in conditions that mirror production settings [

6]. This methodology ensures that performance improvements are both measurable and reliable.

2. The Problem

System-level metrics such as CPU and memory utilization are generally straightforward to collect across most technology stacks, but they often fail to provide the granularity required for diagnosing performance issues in complex applications. Considering RESTful APIs or stream processing systems, measuring the total processing time per request is relatively simple. However, such coarse-grained measurements do not reveal much about the internal distribution of time across different components or operations inside the request lifecycle.

When a systemic increase in request processing time is observed, identifying the underlying cause can be particularly challenging. The source of the performance reduction may be hidden by the layered architecture of applications. Potential causes include, but are not limited to: increased database response latency, file I/O bottlenecks, network problems, or particular spikes in computational complexity. Localizing the precise source of latency may become difficult in the absence of the ability to isolate and measure the execution time of discrete functional units.

An easy approach may seem to capture the execution times at specific points in code, but the practical implementation introduces several challenges. Mixing the application code with the timing logic represents a cross-cutting concern and is generally intrusive. Simply embedding such logic can lead to code that grows and is both difficult to understand and to maintain. In the regular scenarios where the timing of an operation spans multiple classes or layers, additional complexity may arise, such as the need to modify method signatures or propagate timing data across component boundaries. These types of changes are typically undesirable in production-grade systems.

Even if accurate measurements are achieved, further challenges concern the aggregation and analysis of the resulting metrics. A common but naïve approach is to log the timing data directly. However, in high-throughput or computational-intensive systems, where fine-grained measurements are needed, the volume of generated logs may quickly become unmanageable, reducing their utility and potentially introducing performance overhead. These limitations emphasize the necessity for a dedicated tool capable of efficiently collecting, aggregating, and exposing execution time metrics in a non-intrusive and scalable manner.

3. Objectives

This paper introduces a novel framework for measuring execution times of individual operations within distributed systems. Considering the large adoption of Java and the Spring Framework for the development of enterprise applications [

7], the proposed framework is implemented using this technological stack to support broad compatibility and ease of integration.

The primary requirement of the framework is interoperability with widely used metrics collection and data processing systems. Capturing execution metrics is not useful without the ability to persist and analyze them through established tools. In this context, systems such as Prometheus (

https://prometheus.io, accessed 10 October 2025) [

8] and Graphite (

https://graphiteapp.org, accessed 25 October 2025) [

9] serve as natural endpoints for time-series data collection. Also, the framework is designed to support export to several platforms, including event-driven streaming systems as Apache Kafka (

https://kafka.apache.org, accessed 25 October 2025) [

10] and RabbitMQ (

https://www.rabbitmq.com, accessed 25 October 2025) [

11], traditional relational databases, and logging systems. This flexibility allows users to integrate the framework with components very likely to already be present in their operational environments, consequently reducing both the cost and complexity of adoption.

A second core requirement is ease of use. The framework targets software developers as its primary users, and its design promotes a minimal configuration and a low integration overhead. Observability tools are often considered auxiliary to the core business logic of an application; therefore, the framework aims to reduce the time and learning curve necessary to adopt them. The integration process should be straightforward, and the instrumentation of application code should be non-intrusive. Collecting metrics should involve minimal boilerplate code and avoid cluttering the primary logic of the application.

A third requirement is low resource overhead. The framework should preserve the original CPU and memory footprint of the host application to the greatest extent possible. This requirement is mainly important in resource-constrained environments or cost-sensitive deployments, such as those utilizing container orchestration platforms or operating under strict service-level objectives. Some performance cost is unavoidable, as additional processing is required for metric collection, but the framework is designed to minimize its impact on both execution time and system utilization.

To put these constraints in context, it is useful to consider the typical resource profile of a Spring-based application. Idle memory consumption can range from tens to hundreds of megabytes, depending on the presence of additional libraries and middleware. For instance, the default Tomcat thread pool can consume approximately 200 MB of RAM even in idle conditions. CPU usage is more variable and depends heavily on workload and hardware, making absolute measures less meaningful. Instead, relative metrics—such as the percentage increase in the usage of the CPU—are more appropriate. Latency under tens of milliseconds is typically considered acceptable, especially in web-based applications. Accordingly, the framework targets a few operational thresholds: a maximum memory overhead of 1 MB and an added sequential processing time of no more than 1 ms per measured operation.

The interpretation of the added processing time needs to be clarified in this context. Some portions of the logic of the framework necessarily execute in the critical path of the monitored operation, thereby increasing its latency. This is the segment of processing that the framework intends to minimize. Other components of the framework, such as data export or aggregation routines, may operate asynchronously or in parallel with the application logic. While the performance of these asynchronous components is also relevant, they have a lower impact on the responsiveness of the application.

4. Related Work

Observability has evolved into a central research theme in modern distributed systems, encompassing metrics, logs, and distributed traces. While industrial observability stacks have matured rapidly, the academic literature reveals ongoing challenges concerning overhead, instrumentation strategies, measurement fidelity, and architectural complexity. This section situates the present work within the broader scientific landscape, drawing on peer-reviewed studies and comparing the proposed framework with established observability tools in the Java ecosystem.

The conceptual foundations of observability in software systems have been explored in numerous studies that highlight the interplay between monitoring, tracing, and logging. Kosińska et al. [

12] provide a comprehensive review of State-of-the-Art observability practices in cloud-native environments, identifying trends and highlighting the most popular tooling. Their findings emphasize the challenges of performance, efficiency, and security, and the need for lightweight instrumentation strategies.

Pathak et al. [

13] introduce a timely and practical solution to the escalating cost and inefficiency of log-heavy observability pipelines in cloud-native environments, proposing SALO as an autonomous system that adaptively reduces log verbosity without compromising downstream AIOps tasks. The claimed 95% reduction in log volume, combined with maintained diagnostic quality, indicates strong potential impact on both operational cost and system efficiency.

From a more focused perspective, Janes, Li, and Lenarduzzi [

14] conduct a critical comparison of open tracing tools, including Jaeger (

https://www.jaegertracing.io, accessed 12 October 2025), Zipkin (

https://zipkin.io, accessed 12 October 2025), and OpenTelemetry (

https://opentelemetry.io, accessed 12 October 2025). Their work highlights substantial differences in data models, storage backends, propagation formats, and operational overhead, arguing that tracing systems entail non-trivial cost and integration complexity. This distinction is relevant because, while many industrial systems treat tracing as a core observability pillar, the present work intentionally limits itself to execution-time metrics, avoiding cross-service causality tracking and the associated overhead. The study covered a systematic multivocal literature review covering 30 open tracing tools, which gives the paper strong breadth and a rigorous methodology. A major strength is the fairly balanced conclusion: no single tracing tool is ideal for all use cases—each has a unique trade-off profile.

Zhuangbin Chen et al. [

15] propose an advanced sampling technique using locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) to dynamically cluster traces, reducing redundant trace storage while preserving diversity. This reflects a growing trend: not just sampling whole traces, but intelligently biasing sampling based on similarity and novelty, which helps reduce costs without losing signal.

The study from [

15] is extended in [

16], introducing a novel compression structure (Span Retrieval Tree) that avoids naive sampling by compressing trace data and reconstructing full traces on the backend. This indicates a shift in research from just dropping data (sampling) to compressing and deduplicating trace data—promising for reducing storage overhead while keeping trace fidelity.

Yulun Wu et al. [

17] present a method called Autoscope—it uses static code analysis to decide which spans to keep, preserving logical structure while reducing volume by ~81%. This is important: rather than dropping complete traces, you can drop parts of traces (rare or less “important” spans) in a smarter way.

Haiyu Huang et al. [

18] propose a framework (“Mint”) that captures all requests but drastically reduces trace volume by separating common patterns from variable parts. They show very strong storage and network savings (trace size to ~2.7%) while preserving essential trace semantics.

Linh-An Phan et al. [

19] introduce a zero-code instrumentation tracing system using eBPF to infer and correlate spans across threads and services without modifying the application source. This is especially useful for microservices where instrumenting each component manually is expensive or risky; the method is practical and claims high correlation accuracy.

4.1. Observability Overhead

A substantial body of scientific research has examined the performance overhead associated with software instrumentation and monitoring, highlighting that even lightweight observability mechanisms can impose non-trivial runtime costs.

Building on this line of inquiry, Reichelt et al. [

20] conducted a comparative study of modern instrumentation frameworks, evaluating bytecode manipulation, aspect weaving, and sampling-based approaches. Their findings showed that overhead varies considerably across frameworks and depends heavily on how instrumentation is implemented—whether through synchronous event hooks, asynchronous reporting, or dynamic bytecode injection. Importantly, they observed that instrumentation overhead does not scale linearly with event frequency; instead, bottlenecks often arise from queue contention, memory allocation patterns, and garbage collection pressure. These observations reflect several of the challenges addressed in the present work, particularly regarding exporter queue growth and threaded exporter behavior.

A recent study by Hammad et al. [

21] provides a detailed empirical assessment of instrumentation overhead in containerised microservices. Their experiments show that even relatively lightweight code instrumentation can degrade tail latency and reduce overall throughput when applied to services deployed in container-based environments. Importantly, they demonstrate that the interaction between microservice deployment patterns (such as fine-grained decomposition and high request rates) and instrumentation frequency amplifies overhead effects. The study further highlights that the degree of instrumentation—particularly when applied at high granularity—has a direct and measurable impact on response-time variability.

Borges and Werner [

22] examine a real and often underestimated problem in microservice observability: the ad hoc and error-prone nature of instrumentation and configuration decisions. Its contribution—integrating the OXN observability experiment tool into a structured method for continuous observability assurance—provides a practical and systematic approach.

Anders Nõu et al. [

23] perform a detailed measurement study of tracing overhead (latency, throughput) in microservices and serverless environments, focusing on OpenTelemetry and Elastic APM (

https://www.elastic.co/docs/solutions/observability/apm, accessed 14 October 2025). They identify serialization and export of trace data as major contributors to performance degradation, which is very relevant for production observability trade-offs.

A substantial body of research has also focused on techniques for reducing the overhead introduced by instrumentation-based monitoring. A notable example is the work of Kühne, Hasselbring, and Reichelt [

24], who present a systematic analysis of the performance costs that arise in Kieker’s monitoring pipeline and propose concrete optimizations targeting different stages of the data-collection process. Rather than relying on dynamic weaving through AspectJ (

https://eclipse.dev/aspectj/, accessed 15 October 2025)—which incurs additional join point dispatch and stack manipulation—they show that injecting monitoring code directly into the source substantially reduces the per-invocation cost of probe execution. Further reductions are achieved by limiting the amount of metadata stored in monitoring records, replacing the default LinkedBlockingQueue with a more lightweight circular buffer, and aggregating multiple measurement events before writing them to persistent storage. Their evaluation demonstrates that, when all optimizations are applied, the average overhead per monitored method invocation decreases from approximately 4.77 µs to 0.39 µs—an order-of-magnitude improvement. This work provides strong empirical evidence that monitoring overhead can be significantly reduced by redesigning instrumentation and buffering mechanisms, and it offers important conceptual parallels to the present framework’s emphasis on minimizing the cost of metric generation and export. In particular, their findings regarding queue behavior, metadata minimization, and aggregation directly relate to the bottlenecks observed in our evaluation, underscoring the broader need for lightweight, predictable, and bounded-overhead monitoring strategies.

Based on the examined sources, the identified key problems and trends are:

Smarter Sampling and Compression: There is a clear shift towards more advanced techniques—not just sampling entire traces, but compressing or performing span-level decisions—to reduce overhead without losing important data.

Multiplexed Backends: The backend ecosystem is more diverse: newer OpenTelemetry-native solutions (like Uptrace (

https://uptrace.dev, accessed 19 November 2025), OpenObserve (

https://openobserve.ai, accessed 19 November 2025)) are gaining traction alongside more established ones (Jaeger, Tempo (

https://grafana.com/oss/tempo/, accessed 10 October 2025)).

Cost and Scale Awareness: Cost remains a huge concern in industry (per Grafana surveys [

2,

3,

4]), driving adoption of more efficient storage (compression, sampling) and open-source stacks.

Adoption Gap: While OpenTelemetry is very popular, not all organizations are fully tracing: many still do not emit traces from all business-critical workloads.

Performance Trade-Offs Matter: Empirical studies show that tracing impacts latency/throughput; hence, any design has to weigh observability value vs. runtime cost.

4.2. Metrics Collection

Micrometer is the de facto metrics abstraction layer for the Spring ecosystem, offering unified access to a variety of backends (Prometheus, Graphite, Datadog). Its strengths lie in standardized JVM/runtime metrics, HTTP request timing, and integration with Spring Boot Actuator. Very fine-grained developer-defined timings are possible, but require manual timers or custom interceptors, which increases boilerplate. Moreover, Micrometer does not provide general-purpose instrumentation for arbitrary code segments spanning multiple classes, which the proposed framework explicitly targets.

OpenTelemetry has emerged as a standard framework for observability, aiming to unify and standardize the instrumentation and collection of telemetry data across platforms and vendors. It abstracts the observability logic of the application from specific backend implementations, reducing the risk of vendor lock-in. OpenTelemetry can be instrumented automatically or manually, each option coming with advantages and shortcomings. Automatic instrumentation is easy to set up but lacks customization. Manual instrumentation enables the possibility for customization but comes with the need to write boilerplate code.

Elastic APM is a full-stack observability solution developed as part of the Elastic ecosystem, offering automatic instrumentation, distributed tracing, metrics collection, and application-level diagnostics. The Java agent—implemented using bytecode instrumentation via the Java Instrumentation API—injects probes into common frameworks (Spring, JDBC, servlet containers, HTTP clients) to capture spans and contextual metadata with minimal configuration effort. Elastic APM is designed to work within the Elastic stack, so it introduces vendor lock-in. This is something we are trying to avoid, offering integrations with multiple observability backends and storage systems.

4.3. Positioning of This Paper

The objective of the proposed framework is not to replace or compete with established observability ecosystems such as OpenTelemetry, Jaeger, or Zipkin, but rather to introduce an abstraction layer that enables seamless, plug-and-play integration with these and other monitoring backends. Whereas existing solutions focus primarily on distributed tracing, standardized telemetry formats, and cross-platform interoperability, the present framework targets fine-grained, developer-defined execution-time measurements with minimal configuration overhead. In this sense, it is complementary to existing systems, offering a lightweight mechanism for capturing micro-level performance metrics that can be exported into broader observability pipelines with minimal coupling.

5. System Design

5.1. Overview

Java maintains backwards compatibility but generally lacks forward compatibility. Therefore, selecting an appropriate target version is critical: it must be modern enough to include essential developer features, but also sufficiently established to ensure integration with a wide array of existing applications. Within the Java ecosystem, it is advisable to use Long-Term Support (LTS) versions [

25], narrowing the choices to Java 8, 11, 17, and 21. Versions prior to Java 17 are excluded, as Spring Framework 6 requires Java 17 or higher [

26]. On the other hand, Java 21, being around 2 years old, has limited enterprise adoption, as many organizations have not yet completed migration. Consequently, Java 17 represents an optimal balance.

The library will be developed targeting Java 17 and specifically optimized for integration with the Spring Framework. It will be distributed as a set of JAR [

27] artifacts compatible with mainstream build tools such as Maven (

https://maven.apache.org, accessed on 15 October 2025) [

28] and Gradle (

https://gradle.org, accessed 15 October 2025) [

29]. The configuration will be minimized, limited to declaring dependencies and specifying properties, so as to avoid tight coupling between client code and library internals.

To enforce loose coupling, principles such as Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP) and Spring’s Dependency Injection [

30] will be leveraged. Using the Spring context requires the registration of proper components and the creation of a dedicated configuration class, which client applications must import.

5.2. Aspect-Oriented Programming

Aspect-Oriented Programming (AOP) [

31] addresses cross-cutting concerns, which impact multiple distinct parts of an application. If an application is divided into horizontal layers, cross-cutting concerns form vertical slices across these layers. Examples of cross-cutting functionality include logging and exception handling, orthogonal to the core business logic.

Traditional procedural and object-oriented paradigms lack efficient mechanisms for managing cross-cutting concerns, often resulting in code scattering and tangling. AOP mitigates these challenges through weaving techniques.

An initial approach introduced AOP using annotations (e.g.,

@TimedMethod) to automate method execution timing. Both Spring AOP [

32] and AspectJ [

33] may be used for this purpose.

AspectJ, a prominent open-source extension maintained by the Eclipse Foundation, introduces join points [

34] representing program execution points such as method calls or field accesses. AspectJ supports compile-time, binary (bytecode), and load-time weaving. Compile-time weaving requires a specialized compiler that integrates aspect code into application classes. Binary weaving modifies the compiled JARs. Load-time weaving employs a custom class loader [

35] for runtime weaving.

Despite performance advantages, AspectJ comes with several setup complexities, including special compilers and class loaders, which may hinder adoption. Also, its integration with Spring beans can be cumbersome. Consequently, this complexity renders AspectJ unsuitable for a user-friendly library.

In contrast, Spring AOP offers easy integration with Spring applications [

36]. It shares core AOP semantics such as join points, pointcuts, and advices [

37], but employs proxy-based weaving rather than bytecode manipulation. Proxies, implementing the same interfaces as target beans, intercept method calls to execute additional logic before or after the invocation of a method. This proxy mechanism simplifies the configuration but introduces limitations: it only intercepts method calls, excludes the field access interception, and cannot intercept self-invocation within the same class [

38].

These constraints are significant. The inability to intercept private methods and self-invocations reduces the ability to fully monitor performance, which is critical for this library. The @TimedMethod annotation may remain an additional feature, while the enumerated limitations require alternative approaches.

Finally, AOP fundamentally restricts timing operations to entire method boundaries, conflicting with the library’s goal of enabling fine-grained, arbitrarily scoped performance measurement.

5.3. Class Structure

The metrics reporting system includes two main components: the Metrics Reporter and the Metrics Exporter. The Metrics Reporter is responsible for collecting performance data across the application, while the Metrics Exporter exposes this data to various aggregators and communication channels. Manual timing tasks must be removed; this responsibility falls to the Metrics Reporter.

The Metrics Reporter is implemented as a Spring bean offering a simple interface for metric collection, forwarding data to the exporter. The Metrics Exporter is designed as a modular, plug-and-play component adaptable to different backend solutions. A selection of exporters will be provided, with extensibility for custom implementations.

To maintain modularity and prevent circular dependencies, the dependency inversion principle [

39] is applied: exporters depend on the reporter interface, rather than vice versa (

Figure 1).

5.4. The Metrics Reporter

The MetricsReporter interface aims for simplicity and minimal developer overhead, exposing 2 primary methods: one to start an operation and another to end it. An operation is a unit of work defined by the developer, potentially spanning multiple lines of code and classes. Each operation instance requires a unique identification to measure execution time precisely.

The initial signature of the methods void startOperation(String operationName) and void endOperation(String operationName) is enough for single-threaded scenarios, but fails in concurrent contexts due to ambiguity in matching operation instances. If multiple threads execute the same operation in parallel, relying solely on the operation name makes it impossible to distinguish between different invocations. This can lead to incorrect measurements, such as ending the wrong operation instance or aggregating unrelated timings. To resolve this, each operation instance must receive a unique identifier.

The choice of the identifier creation is a trade-off: if the reporter generates it, the uniqueness is guaranteed, but the developers must propagate the identifier throughout the operation, complicating the code. Alternatively, developers may supply identifiers, which may already exist intrinsically within the domain objects (e.g., user IDs). This approach simplifies the usage at the expense of incorrect identifiers, leading to inaccurate metrics and misuse.

For clarity, the identifier type is standardized as a String. The user can choose whether to generate the identifier randomly or use an intrinsic identifier. Methods are thus refined to: void startOperation(String operationName, String operationId) and void endOperation(String operationName, String operationId).

Upon the invocation of

startOperation, the reporter records the current time. Correctness demands the use of a monotonic clock to avoid skew-related errors.

System.currentTimeMillis(), representing wall-clock time, is vulnerable to system clock adjustments [

40,

41]. Conversely,

System.nanoTime() provides a monotonic, high-resolution time source [

41], albeit at a higher computational cost.

A concurrent data structure (ConcurrentHashMap) is employed to track active operations efficiently and safely in multi-threaded environments. The map key combines the operation name and identifier, mapping to the recorded start time.

Time is captured immediately upon method entry, preceding parameter validation, ensuring accuracy.

Exception handling covers two scenarios: ending a non-existent operation and starting an already running instance. The former results in a null retrieval from the map, potentially causing NullPointerExceptions. To avoid disrupting core application logic, such exceptions are caught, and a warning is logged. The latter overwrites the existing start time, risking silent data corruption; this is similarly logged at the WARN level.

Currently, metrics export is performed synchronously on the application thread, risking performance degradation if exporters conduct costly I/O operations. To mitigate this, exporting is offloaded to a dedicated

SingleThreadExecutor [

42]. Metrics submission and cache management occur on this thread, eliminating synchronization bottlenecks and isolating exporter latency.

This approach introduces new challenges: heavy concurrent workloads may overwhelm the single exporter thread, causing export delays, memory bloat due to queued metrics, and delayed application shutdown. Future improvements may involve multi-threaded exporters.

5.5. Caching Statistics

Immediate metric export imposes a continuous system load. Caching metrics and exporting them periodically addresses this, but introduces configuration complexity.

Export intervals must be developer-configurable, as no universal setting fits all applications. A minimum interval of 500 ms is enforced; no maximum limit is imposed.

Caching size limits complement time-based export triggers. A maximum cache size, configurable between 1 and 1000 entries, ensures memory consumption remains bounded. Metrics are exported when either the time interval elapses or the cache size limit is reached.

Upon operation completion, elapsed time data is encapsulated and added to the cache, which is cleared after each export.

To prevent loss of cached metrics on application shutdown, export logic is integrated into the Spring lifecycle via the

DisposableBean interface [

43]. The destroy method triggers a final export upon application context termination.

5.6. Addressing the Impact of Garbage Collection Pauses

The Garbage Collection mechanism present in Java can introduce non-deterministic latency during memory reclamation cycles. Specifics differ between garbage collectors, but pauses in the range of tens of milliseconds can be expected. This does pose problems for a framework aiming to measure even operations in the single-digit millisecond range.

Besides being a purely technical issue, this is also part of the realm of user needs. GC pause time being part of the measurements is not necessarily wrong, as it directly depicts the “real” time it took for the operation to complete, as perceived by an outside observer.

GC pause time varies a lot between different JVMs and garbage collector implementations; hence, users can expect non-deterministic results. As a general recommendation, if the latency of the operations is critical, users should consider using the Z Garbage Collector.

Another factor that could, in theory, introduce non-determinism is the Just In Time Compiler (JIT), but we consider it to be a negligible factor in the context of this framework due to the relatively stable execution state achieved after the initial warm-up phase.

6. Exporters

6.1. Apache Kafka Exporter

6.1.1. Overview and Architecture

Apache Kafka is a distributed event streaming platform developed and maintained by the Apache Software Foundation. Its features include high throughput, fault tolerance, scalability, and robust integration capabilities, and it is suitable for deployment in containerized environments, on bare-metal systems, and in cloud-based infrastructures [

44,

45].

The core concept of Kafka is the event, which is essentially a stream of bytes. Events are generated by producers and consumed by consumers, both of which interact with Kafka brokers, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Events are categorized into topics, which are logical groupings of related data. For instance, a financial application may use separate topics for account creation and payment transactions. Each topic is divided into partitions, which are immutable, append-only logs that facilitate parallel processing and scalability.

Kafka ensures resilience via replication. Each partition has a leader and one or more followers. The leader handles all read and write operations, while followers replicate its data. In case of failure, a follower may be elected as the new leader using a consensus algorithm.

Producers determine which partition an event is written to, typically based on a round-robin approach or a partitioning key [

10]. On the consumer side, consumer groups allow for horizontal scaling, with the following properties:

A single partition may only be consumed by one consumer within a group.

Events within a partition are strictly ordered, and no guarantees exist across partitions.

Kafka tracks consumer progress through offsets, which record the last acknowledged message per partition. This enables consumers to resume accurately in the case of interruption.

Kafka was selected as an exporter for this project due to the following attributes:

6.1.2. Implementation

The Kafka exporter is implemented as a Maven module: com.alexg.performance:kafka-exporter.

It depends on the com.alexg.performance: timer module and the Kafka client library org.apache.kafka:kafka-clients.

The KafkaExporter class extends PerformanceExporter and initializes a Kafka producer instance. For correct operation, users must:

The topic must preexist, as many Kafka clusters restrict automatic topic creation.

6.1.3. Experimental Setup

Traditionally, Kafka required Apache Zookeeper for cluster orchestration. Ever since version 3.1, Kafka has introduced the KRaft mode, meant to replace Zookeeper. Zookeeper was deprecated in release 3.5, and the support was dropped entirely in release 4.0. Nevertheless, this experimental setup uses Zookeeper.

Kafka and Zookeeper are deployed in Docker containers using the confluentinc/cp-kafka and confluentinc/cp-zookeeper images. A single broker configuration with plaintext communication is employed. Topic creation is scripted to run at container startup, and a health check mechanism ensures the application does not start until the broker is available.

For event inspection, Kafka UI is deployed in a separate container.

6.2. Prometheus Exporter

6.2.1. Overview and Architecture

Prometheus (

https://prometheus.io, accessed 10 October 2025) is an open-source monitoring and alerting system, originally developed by SoundCloud and later adopted by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) [

8]. Prometheus is well-suited for observability in distributed systems due to its scalability, simplicity, and native support for multi-dimensional time-series data.

Unlike Kafka, which relies on a push-based model, Prometheus uses a pull-based approach. It periodically scrapes metrics from configured targets via HTTP. These metrics are stored in a time-series database and queried via the Prometheus UI or third-party tools such as Grafana.

Queries are written using PromQL [

48], a purpose-built language for time-series data.

The Prometheus ecosystem consists of:

Prometheus Server: It is the central component with the time-series database and HTTP scraping service.

Alertmanager: Manages alert routing and notifications based on PromQL queries.

Web UI: Provides interactive data exploration.

Pushgateway (optional): Allows short-lived services to expose metrics, though its use is discouraged by the Prometheus maintainers [

49].

6.2.2. Implementation

Prometheus supports several metric types [

50]: counter, gauge, summary, and histogram. From these, the gauge and histogram are most appropriate for capturing performance metrics.

Gauge: Captures the latest value at the time of a scrape, suitable for instantaneous measurements but susceptible to missing outliers.

Histogram: Aggregates values into configurable buckets and stores cumulative counts and sums. Histograms are best used for the analysis of execution durations.

Given the nature of metric collection via scraping, some values may be lost if the application terminates before a scheduled scrape. This data loss is illustrated in

Figure 3.

To expose metrics, the exporter starts an embedded HTTP server, which serves data on the/metrics endpoint.

6.2.3. Experimental Setup

Prometheus is deployed using the official Docker (

https://www.docker.com, accessed 13 October 2025) image (

prom/prometheus:latest). Scraping targets and intervals are specified via a YAML configuration file mounted into the container. The web interface is exposed on host port 9000.

Each test application instance exposes metrics on a unique port (8082 and 8083) due to local conflicts. Prometheus is configured to scrape these endpoints every 5 s and verify their health status.

For visualization, Prometheus is paired with Grafana (grafana/grafana:latest). Dashboards are persisted via Docker volumes. The Grafana dashboard includes:

Two heatmaps showing the evolution of request time distributions.

A comparative panel for the two test instances.

A liveliness monitor for service availability.

The architecture validation imposes a series of tests to prove the ability of the created application to adapt and deliver an available service even under harsh conditions.

6.3. RabbitMQ Exporter

6.3.1. Architectural Overview

RabbitMQ is a widely adopted open-source message broker that implements the Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) [

51]. It serves as a fundamental component in distributed systems, facilitating asynchronous communication through a message-driven architecture. The core architectural entities in RabbitMQ include Producers, Exchanges, Queues, and Consumers.

Producers are responsible for publishing messages to the message broker. These messages are not sent directly to queues; instead, they are initially directed to Exchanges, which act as routing intermediaries. Exchanges determine the routing of messages based on their type and routing configuration.

RabbitMQ supports 4 types of exchanges:

Direct exchanges perform exact routing based on the routing key of the message.

Topic exchanges enable pattern-based routing, providing flexible matching of routing keys.

Fanout exchanges disregard the routing key entirely and broadcast messages to all bound queues.

Headers exchanges route messages based on the attributes in the message headers instead of the routing keys.

Queues serve as the primary message buffers, temporarily storing messages until they are retrieved and acknowledged by consumers. Queues may be transient (memory-based and non-persistent) or durable (persisted to disk and resilient across broker restarts).

Consumers are applications that subscribe to queues to retrieve and process messages. Unlike the pull-based approach of Kafka, RabbitMQ employs a push model in which the broker actively delivers messages to consumers. Although polling is technically supported, it is discouraged due to performance implications [

52]. Consumers must explicitly acknowledge messages upon successful processing. In cases of consumer failure or message rejection, unacknowledged messages are either requeued or discarded, depending on the acknowledgement mode.

6.3.2. Implementation Details

For integration with Spring-based applications, the org.springframework.amqp:spring-rabbit Maven artifact was employed. The RabbitMqPerformanceExporter class was developed to implement the PerformanceExporter interface. This class is designed to receive a RabbitTemplate instance, which is automatically provisioned by the Spring IoC container when using the library above.

Two configuration properties govern the runtime behavior of the exporter:

These parameters ensure precise and flexible routing of performance metrics within the messaging infrastructure of RabbitMQ.

6.3.3. Experimental Setup

The RabbitMQ broker was deployed using the official Docker image rabbitmq:3-management, which exposes both the AMQP port (5672) and the management console on port 15672. These were mapped directly to the host machine to facilitate configuration and monitoring.

A configuration file defining the object definitions of the broker was mounted into the container, along with a JSON-based definitions file. This file provisioned a durable queue, a direct exchange, a binding between them, and a default guest user for administrative access.

To ensure that the broker is fully initialized prior to starting the containers of the test application, a health check mechanism was implemented. This mechanism executes the rabbitmqctl status command at 10-s intervals until the container reports a healthy state. Following this, the test containers are initialized.

6.4. SQL Exporter

6.4.1. Performance Optimization Strategies

The exporter periodically inserts multiple metric entries into the database, corresponding to the size of the internal metric cache. Performing individual insert operations for each entry would result in significant network overhead due to repeated round trips.

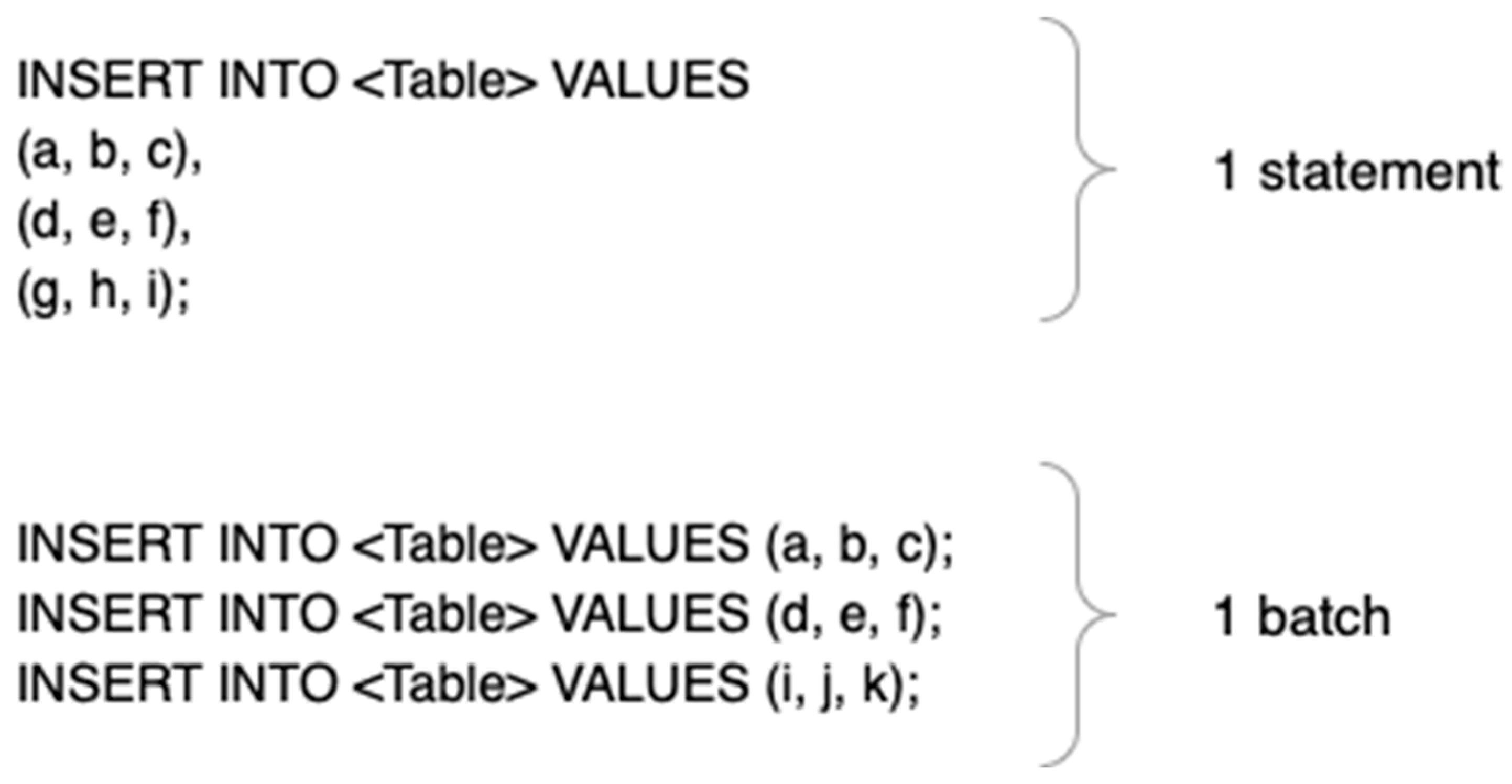

To address this, two optimization alternatives were evaluated:

Bulk Inserts: Constructing a single SQL statement containing multiple value tuples (

Figure 4, top).

Batching: Using JDBC batching to group multiple

PreparedStatement executions into a single round-trip (

Figure 4, bottom).

Although bulk inserts are straightforward to implement, they are subject to limitations imposed by RDBMS vendors. For example, Microsoft SQL Server limits insert statements to 1000 rows. Consequently, if the cache size exceeds this threshold, execution failure may occur. Therefore, batching was selected as the preferred approach. Empirical studies [

53] have shown that batch sizes of 50 yield a substantial reduction in insertion latency while maintaining robustness.

Another performance consideration involves database connection management. Establishing a new connection requires both TCP and TLS handshakes, which, though individually fast, can accumulate substantial latency when repeated. Connection pooling mitigates this by maintaining a pool of pre-established connections, reducing connection overhead.

Popular pooling libraries such as HikariCP are commonly used in conjunction with frameworks like Hibernate. Nevertheless, in this implementation, connection pooling was intentionally avoided. The exporter operates on a single thread and maintains a relatively small number of connections. Moreover, pooled connections could impair the performance of the hosting application, particularly if the pool size is tightly constrained.

Although integrating with an existing application-level pool is theoretically feasible, it risks overutilizing shared resources. As a compromise, a static Connection object could be retained within the exporter for its entire lifecycle. However, this approach introduces state management complexity and potential long-lived resource leaks. As long as the exporter performs adequately without pooling, additional complexity will be avoided.

6.4.2. Implementation Details

The SQL-based exporter is implemented within a Maven module identified as com.alexg.performance:sql-exporter. This module declares a dependency on org.springframework.boot:spring-boot-starter-data-jpa to facilitate database connectivity via the Java Persistence API (JPA). Additionally, it depends on the com.alexg.performance:performance-timer module, which provides the foundational PerformanceExporter interface.

Within the module, the primary component is a class named SqlExporter, which implements the PerformanceExporter interface. The constructor of SqlExporter requires three parameters: a DataSource object, a string denoting the application instance name, and another string specifying the name of the metrics table. These parameters can be injected by Spring’s dependency injection mechanism. The DataSource is automatically instantiated by Spring when the JPA starter is present in the classpath and when the appropriate connection properties are defined in the application’s configuration file. The instance name and table name must be explicitly provided in the properties file under keys such as instance.name and db.metrics.table.

Internally, SqlExporter employs a PreparedStatement to persist metric data into the specified table. The SQL statement includes three placeholders corresponding to the following parameters: an operation name (String), the execution time in nanoseconds (Long), and the application instance identifier (String), as illustrated in

Table 1. The implementation assumes the target table includes at least three columns: operation_name (text), execution_ns (numeric), and instance (text). Although additional columns are permitted, the absence of any of these three required columns results in runtime failures.

The exact column data types may vary depending on the database dialect, and users must ensure that the lengths of text columns are sufficient to store the largest possible values. Failure to do so could result in data truncation or runtime exceptions, compromising correctness.

In addition to the parameters required by the SqlExporter, Spring mandates the presence of the following properties to correctly instantiate the DataSource: spring.datasource.url, spring.datasource.username, and spring.datasource.password. The URL must conform to the JDBC format for the selected database. The JDBC driver is typically inferred from the structure of the URL.

6.4.3. Test Setup

To evaluate the functionality of the SQL exporter, PostgreSQL (version 15) was selected as the underlying database due to its widespread adoption and open-source nature. The database was deployed using a Docker container based on the postgres:15 image. Port 5432, the default PostgreSQL port, was mapped to the host to enable communication. Container initialization was configured via environment variables to set a database name (metrics_db) and provide authentication credentials.

An SQL script (init.sql) is run for the schema initialization and is authored to create the required metrics table. This script was mounted into the container at /docker-entrypoint-initdb.d/init.sql, a path recognized by the PostgreSQL image for automatic execution during startup. As a result, the database is immediately prepared to receive metrics upon application launch.

The application was configured to use the following JDBC URL: jdbc:postgresql://postgres:5432/metrics_db. This format comprises the protocol, driver, host reference, port, and database name.

To verify database insertions, there are several options: querying from a command-line interface, utilizing the database view in IntelliJ IDEA, or employing a graphical management interface such as pgAdmin. The latter was selected for its comprehensive UI and ease of use. pgAdmin was deployed in a separate Docker container using the image dpage/pgadmin4:latest, thereby avoiding local installation.

6.5. Cassandra Exporter

6.5.1. Background and Characteristics

Non-relational databases, though conceptually established for decades [

54], gained prominence under the collective term “NoSQL” in the early 21st century. This term encompasses a broad spectrum of databases that diverge from the relational model, addressing the evolving scalability and flexibility demands of modern data-intensive applications.

NoSQL databases differ significantly in design and application. MongoDB (

https://www.mongodb.com, accessed 19 October 2025) uses a document-oriented approach, storing data as JSON-like structures [

55]. Key-value stores such as Redis (

https://redis.io, accessed 19 October 2025) [

56] and Memcached (

https://memcached.org, accessed 19 October 2025) [

57] serve high-throughput caching needs. Graph databases like Neo4j (

https://neo4j.com, accessed 19 October 2025) [

58] prioritize relationships, using node-edge models well-suited to GraphQL-enabled architectures [

59]. Wide-column stores, including Apache Cassandra (

https://cassandra.apache.org/_/index.html, accessed 25 October 2025) [

60], blend row-based storage with schema flexibility, also allowing dynamic column definitions across rows.

A notable contrast between NoSQL and relational systems lies in their adherence to ACID properties. While traditional RDBMSs typically enforce transactional guarantees to maintain atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability, NoSQL databases often relax these constraints to improve scalability. Many NoSQL systems favor eventual consistency and exhibit diverse trade-offs within the CAP theorem [

61]. According to the CAP theorem, no distributed system can simultaneously achieve consistency, availability, and partition tolerance. Relational databases often support CA configurations (consistency and availability), whereas NoSQL databases—Cassandra being a notable example—typically prioritize availability and partition tolerance (AP).

Apache Cassandra, released by Facebook in 2008, exemplifies this trade-off. It achieves high availability and fault tolerance through a masterless architecture, employing a gossip protocol to synchronize cluster state across nodes. Seed nodes play a critical role in cluster initialization and stability.

Cassandra’s data model bears surface similarity to relational databases, albeit with key distinctions. Instead of databases, Cassandra uses “keyspaces,” which contain tables with loosely defined schemas. Rows within a table are identified by a composite primary key, comprising a partition key used to distribute data across nodes. The query language of Cassandra (CQL) borrows SQL-like syntax but omits features like joins, necessitating careful denormalization during data modeling to align with its distributed nature.

6.5.2. Implementation Details

The Cassandra-based metrics exporter was implemented within a dedicated Maven artifact named

com.alexg.performance:cassandra-exporter. This module depends on the core performance instrumentation module

com.alexg.performance:performance-timer, which provides the base interface

PerformanceExporter. In addition, it includes the

com.datastax.oss:java-driver-core dependency to enable programmatic interaction with a Cassandra database (

Figure 5).

The primary class within this module, CassandraExporter, implements the PerformanceExporter interface. Its constructor requires several parameters essential for establishing connectivity and ensuring correct metric storage: a string representing the contact point address of the Cassandra node, an integer indicating the port number (typically 9042), a keyspace name, a table name for metric storage, and the logical identifier of the exporting application instance. These values are externally configurable and retrieved at runtime via Spring properties:

cassandra.contact.point (Cassandra host),

cassandra.port (port number),

cassandra.keyspace (Cassandra keyspace name),

cassandra.exporter.table (metrics table name), and

INSTANCE_NAME (application instance identifier).

Using these parameters, the exporter constructs a CqlSession object, which serves as the main communication channel with the Cassandra database for the lifetime of the exporter instance. For data insertion, the exporter utilizes a Cassandra-specific PreparedStatement class provided by the DataStax driver (com.datastax.oss.driver.api.core.cql.PreparedStatement). This statement is configured as an INSERT operation targeting the specified metrics table, with parameters corresponding to the operation name (text), execution duration (numeric), application instance (text), and the timestamp of insertion (temporal value). The name of the target table is dynamically resolved based on the value of the cassandra.metrics.table configuration property.

The exporter thereby enables seamless and consistent insertion of performance metrics into a Cassandra store using a parametrized, strongly typed, and precompiled query mechanism, which is robust under high-throughput workloads.

6.5.3. Test Setup

For the evaluation of the Cassandra exporter, the Apache Cassandra database (version 4.1) was deployed in a containerized environment using the official Docker image cassandra:4.1. The standard Cassandra communication port (9042) was exposed and mapped directly to the host system to facilitate external access.

To ensure proper initialization of the keyspace and schema prior to metric ingestion, a secondary container, named cassandra-provision, was introduced. This auxiliary container, also based on the cassandra:4.1 image, was designed exclusively for executing provisioning scripts. It was configured to run a shell script that repeatedly attempts to connect to the main Cassandra container using cqlsh in a loop. The delay interval between attempts is 2 s. Once a successful connection is established, the script executes a secondary CQL file that contains the statements required to create the schema, including the keyspace metrics_keyspace and the associated metrics table. The provisioning logic is initiated through the entrypoint directive of the container in the Docker Compose configuration.

This approach eliminates the need for separate container health probes, as the provisioning logic itself implicitly handles availability checks. However, the test application responsible for exporting metrics must not start prematurely, as failure to connect to a fully initialized Cassandra instance would result in runtime errors. To address this, the container orchestration logic enforces a dependency: the exporter application containers are only launched once the provisioning container reaches a terminal state of service_completed_successfully.

Once the test environment is operational, verification of metric insertion is performed using cqlsh, the native Cassandra command-line interface.

7. Testing

7.1. Test Application

To evaluate the performance of exporters, a minimal Spring Boot application was developed [

62]. The application creates a fixed-size thread pool and continuously submits two operations labeled

opname1 and

opname2, both instrumented by the metrics collection framework. These operations simulate computational work by invoking a sleep function for a randomly determined duration. Unless otherwise specified, the sleep duration is sampled from a normal distribution with a mean of 400 ms and a standard deviation of 100 ms.

The test environment was containerized to ensure repeatability, portability, and system isolation. Docker containers were used to simulate a distributed environment, with orchestration handled via Docker Compose [

63]. The test application container image is derived from

openjdk:17.0.1-jdk-slim. Two instances of the application are deployed to better replicate a distributed system’s behavior. Each exporter under evaluation is deployed in its own dedicated container, as described in the relevant subsections of Chapter 6.

7.2. Measurement Accuracy

Quantifying the accuracy of execution time measurements presented significant challenges, primarily due to the difficulty of establishing a ground truth for timekeeping. One natural candidate,

Thread.sleep(long millis), offers limited precision due to its dependence on operating system-level schedulers and timers [

64], rendering it unsuitable as an absolute reference. Similarly, comparing the custom

MetricsReporter to Java’s

System.nanoTime() is infeasible, as the framework internally relies on

System.nanoTime() for its own measurements.

Ultimately, the approach adopted in this study assumes that Thread.sleep() introduces a negligible error and attributes any measurement discrepancy entirely to the framework. To facilitate accuracy testing, a specialized exporter—StatisticsExporter—was implemented. This component records the number of invocations and computes the average duration reported by the framework over a fixed number of samples (n = 5000). Measurements were conducted for 3 sleep durations: 2 ms, 20 ms, and 200 ms.

Measurements were performed on 10 different AWS EC2 T3 Small instances. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

The relative error decreases with increasing sleep duration: ~7% for the 2 ms reference, <1% for 20 ms, and <0.1% for 200 ms. These findings indicate that the framework’s accuracy improves substantially for operations with non-trivial execution durations. Although some observed error may stem from inaccuracies inherent in Thread.sleep(), the results are satisfactory for performance monitoring purposes, where identifying trends is more critical than achieving nanosecond-level precision.

The Mean Absolute Error is very similar for all the references, especially considering the large differences between the references. This signifies that there is an almost fixed error of about 0.13–0.14 ms. Variability is higher when measuring small references, with the standard deviation decreasing when the reference is increased.

7.3. Impact on Throughput

To assess the runtime overhead introduced by instrumentation, throughput was measured in 3 scenarios: (i) without timing instrumentation, (ii) using the legacy single-threaded

MetricsReporter, and (iii) using the new asynchronous reporter. The test involved performing

Thread.sleep(20 ms) sequentially across 5000 invocations. Measurements were performed on 10 different AWS EC2 T3 Small instances. The Kafka exporter served as the target backend in all scenarios. The asynchronous nature of the reporter means that the choice of exporter would not make a difference when measuring the impact on throughput, as the part of the code that runs on the same thread as the business logic only adds the metrics to a queue. Execution times are presented in

Table 3.

The asynchronous reporter incurs very little noticeable overhead, with an average increase of 0.73% compared to the baseline. In contrast, the synchronous reporter introduces a measurable slowdown of 7.67% when compared to the baseline and 6.88% when compared to the asynchronous reporter, attributable to blocking operations.

The synchronous exporter produced a standard deviation an order of magnitude larger than that of the baseline, with the synchronous exporter faring even worse in this regard

7.4. Resource Consumption

In practical software engineering, every additional framework or module is evaluated against its resource cost. This cost includes (i) integration effort, (ii) maintenance overhead, and (iii) runtime resource consumption. The first 2 aspects have been addressed through the design philosophy of this framework, which emphasizes simplicity and non-invasiveness. The focus here is on evaluating the third component—specifically, the additional CPU and memory overhead introduced by the instrumentation logic.

To this end, the same Spring Boot 3.2 test application was used, with no functional logic apart from metrics collection and export. This setup serves as a proxy for real-world applications in which the framework is expected to be integrated. The test application was executed inside a Docker container on 10 different AWS EC2 T3 Medium virtual machines.

We chose EC2 because it is the main virtual machine offering of one of the biggest cloud providers, AWS. T3 Medium was chosen because the “T” instance family is the general-purpose instance family, suitable for running a regular web application. The Medium instance choice was based on its resource allocation, 2vCPU and 4 GiB of memory, which should be more than enough for our needs. As for the operating system, we chose the Amazon Linux 2034 6.1 Amazon Machine Image (AMI), the latest Amazon-provided AMI at the time of testing.

Developers can replicate the baseline (i.e., an idle Spring Boot application) on their own hardware to estimate the expected overhead introduced by the framework. CPU and memory statistics were collected using Docker’s container-level reporting tools. Since the test container was the sole active application, differences in resource usage across configurations are attributable to instrumentation.

To obtain the metrics, we created a script that runs the docker stats command every second and appends the result to a file. To retrieve that file from the EC2 instances, it was first uploaded to S3 and then downloaded to our local machines. The Docker image of our test application was uploaded to the AWS Elastic Container Registry for it to be available within the EC2 machine.

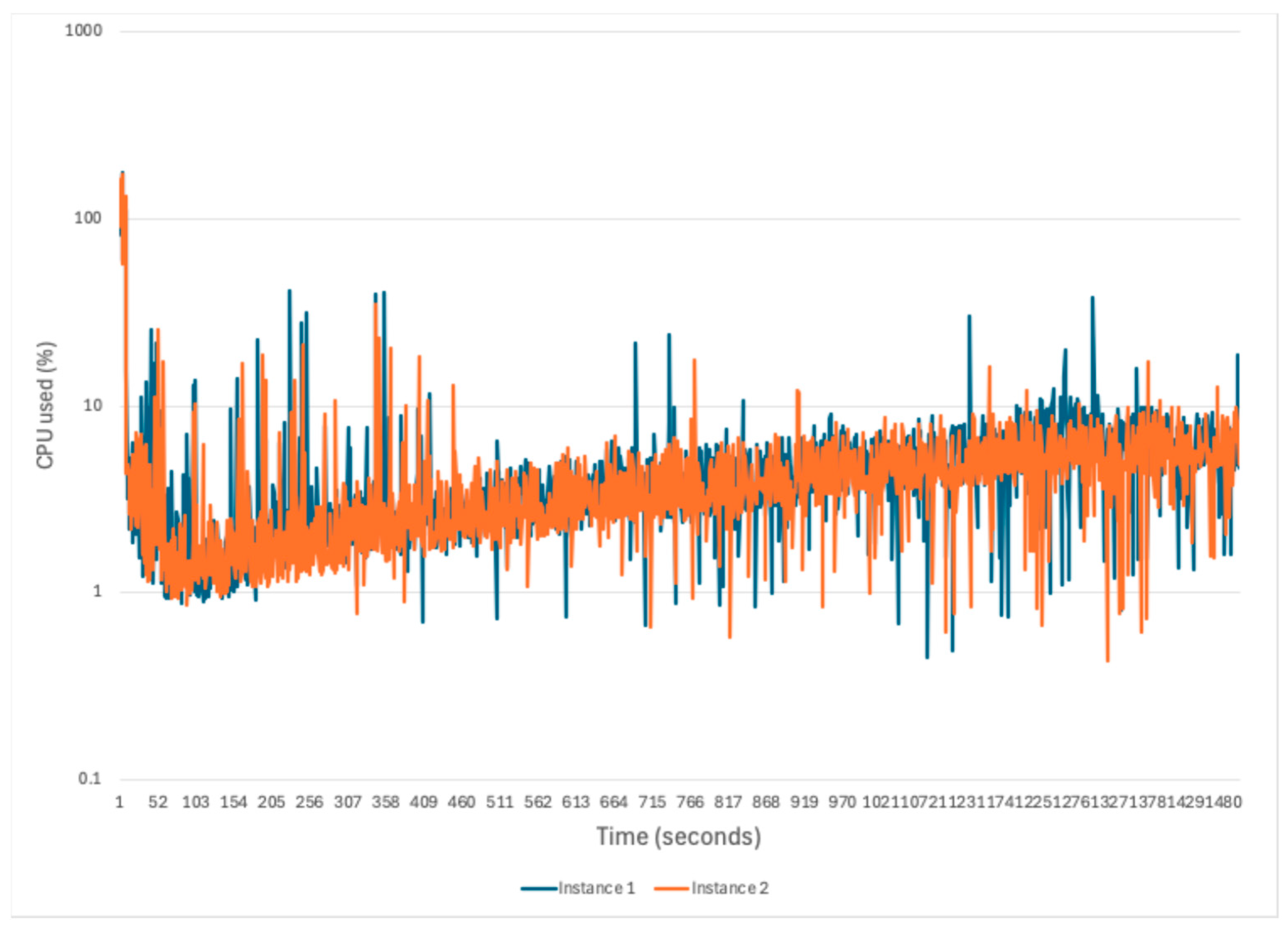

The results are presented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. In the interest of legibility, we chose only to depict the first two instances in

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. The data from all the runs is available in the annexes. Across all runs, we measured memory consumption (excluding initialization in the first 60 s) to have an average of 245.45 MiB, a median of 242.70 MiB, and a standard deviation of 7.55 MiB, signaling relatively constant memory consumption. Similarly, CPU consumption had an average of 3.94%, with a median of 3.98% and a standard deviation of 1.01%.

7.4.1. Worst-Case Resource Utilization

To evaluate the upper bounds of resource consumption, a stress test was conducted under a synthetic worst-case scenario in which all exporters were active simultaneously. While such a configuration is unlikely in production deployments, it provides a conservative estimate of the exporters’ combined demand on system resources.

In this scenario, metrics were generated artificially through two continuously active threads, each submitting a metric at fixed intervals. The first configuration involved one metric submission every 400 ms per thread, while maintaining the default maximum of 10 cached metrics.

A sample of the results after running the measurements on 10 machines is presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. The average CPU consumption was 4.27%, with a median of 3.73% and a standard deviation of 3.28%. The difference in CPU consumption is negligible, measuring 0.33%. These spikes are attributed to synchronized metric flush operations across all exporters. As seen in

Figure 9, memory consumption increased from the baseline to a new average of 309.22 MiB, with a median of 306.5 MiB and a standard deviation of 13.77 MiB. This outcome was expected due to the initialization of exporter-related data structures, including caches and thread pools.

To intensify the load, the metric production interval was reduced to 40 ms. Under this configuration, the average CPU usage increased to approximately 4.59%, with a median of 4.06% and a standard deviation of 3.27% (

Figure 10). This represents a difference of only 0.65 percentage points compared to the baseline. Memory usage increased slightly (

Figure 11), to a new average of 321.61 MiB, with a median of 323 MiB and a standard deviation of 9.92 MiB. This plateau in memory utilization suggests that memory consumption is dominated by static components (e.g., beans, thread pools, buffer structures), and is largely invariant to the frequency of metric creation.

7.4.2. Per-Exporter Resource Profiling

To further refine the analysis, each exporter was profiled individually on the 10 EC2 T3 Small virtual machines to assess its isolated impact on resource consumption. Results are summarized in

Table 4 and

Table 5. The tests were run for 600 s for each scenario.

Among the evaluated exporters, the Prometheus exporter and the Logger exporter demonstrated the lowest resource consumption. For Prometheus, this efficiency is primarily due to its passive architecture: it exposes metrics via an HTTP endpoint, placing the responsibility of retrieval on the external Prometheus server via periodic scraping. This model offloads computational effort and is less resource-intensive compared to exporters that actively push metrics (e.g., Kafka, SQL, Cassandra). For the logger exporter, its efficiency comes from a lack of network calls.

It is important to emphasize that the measurements in

Table 4 should be interpreted qualitatively rather than quantitatively. Actual resource usage is influenced by a variety of factors, including runtime environment, container configuration, host system architecture, and workload characteristics. Consequently, developers are advised to evaluate exporter performance in staging environments that closely mirror production deployments. This includes using realistic metric volumes and exporter configurations, reflective of expected operational conditions.

7.5. Impact of Garbage Collectors

Due to their popularity, we decided to test the potential impact of the G1 and the Z garbage collector on application throughput. We used the same methodology from

Section 7.3, with 5000 20-ms operations on 10 different T3 Small virtual machines. The results were very close, with the G1 garbage collector having an average execution time of 100,779.304 ms, while the Z garbage collector had an average execution time of 100,849.783 ms. This is well within the margin of error and could be attributed to the fact that there were not a lot of objects to be collected. Every application has specific needs depending on its memory usage pattern, so it is difficult to create a good generalization. We maintain our stance that garbage collection pauses are very unlikely to affect the measurement performance because, if a GC pause happens in the middle of the operation, that delay is reflected in the operation time and should be measured.

8. Addressing the Limitations of a Single-Threaded Exporter

The single-threaded approach to metrics reporting and exporting presents a number of significant advantages. The most important thing is its conceptual simplicity and reduced likelihood of implementation defects. In software engineering, minimizing complexity is a key design principle. However, under certain operational conditions—particularly high-throughput scenarios—this design may prove inadequate. This section explores the inherent limitations of the single-threaded model and examines potential strategies for enhancing performance and scalability.

In environments characterized by high-frequency metric generation, the processing capacity of the exporter may become a bottleneck. For stable system behavior, the rate of metric production must not exceed the average export rate. Caching can temporarily mask discrepancies between production and consumption rates, but persistent imbalances will eventually exhaust available memory resources.

To illustrate this point, we consider a simplified scenario in which a single producer thread generates a metric every 10 ms, and the cache holds up to 10 entries. Assuming an export time of 10 ms per metric, the exporter will operate at full capacity, expending 100 ms to process a full cache. As long as export and production rates remain balanced, the system is stable. However, when export latency exceeds the production interval, metrics will accumulate indefinitely, eventually leading to resource exhaustion.

Such conditions pose a critical threat to application stability. Unbounded growth in queued metrics—particularly in memory-constrained environments—will culminate in out-of-memory (OOM) errors. Crucially, this failure mode is difficult to detect preemptively, as standard logging mechanisms may not capture indicators of resource pressure. From the perspective of the operator, the only observable symptom may be a gradual increase in memory usage.

Several strategies can be employed to mitigate this issue. A naïve yet effective solution involves rejecting new metrics once the internal queue of the exporter surpasses a predefined threshold. While this method guarantees bounded memory usage and is trivial to implement, it suffers from a significant drawback: loss of data. Metrics rejected under such conditions are irretrievable, which compromises the accuracy of the observability of the system. Furthermore, this behavior introduces non-determinism into monitoring, as neither the presence nor the absence of a given metric can be guaranteed.

An alternative approach involves parallelizing the exporter using a multi-threaded architecture. In theory, this should improve throughput by distributing workload across multiple threads. In practice, however, such an approach introduces considerable implementation complexity and heightened susceptibility to concurrency-related defects. Moreover, the extent of performance gains is difficult to predict, as it depends on numerous factors, including JVM behavior, hardware characteristics, the number of available database connections, and I/O latency.

The challenge of determining an optimal thread count is non-trivial. A fixed-size thread pool must be appropriately dimensioned for the target environment, a task made difficult by the heterogeneity of deployment configurations. Delegating this decision to the framework’s users via configuration parameters may alleviate the problem, but it also places the burden of tuning and performance validation on the developers integrating the framework.

Dynamic thread management, such as that offered by cached thread pools, provides an appealing compromise. Cached pools dynamically adjust the number of active threads in response to load, offering increased flexibility compared to fixed pools. However, this approach introduces new risks: excessive thread creation under sustained load can lead to memory pressure and degraded performance due to increased context switching. These considerations are particularly remarkable in I/O-bound workloads where concurrency does not always translate into improved performance, especially when backend resources (e.g., database connections) are saturated.

A more modern alternative is the use of Java’s virtual threads, introduced in version 21. Virtual threads are lightweight and well-suited for I/O-intensive workloads. They can be effectively managed using the

Executors.newVirtualThreadPerTaskExecutor(), which schedules tasks onto a shared pool of platform threads [

65]. This model mitigates the cost of context switching and reduces the memory overhead associated with thread management. However, adoption of this feature is currently limited by the conservative upgrade cycles of the industry. Many production systems continue to rely on Java 11 or 17, both of which remain under long-term support. As a result, reliance on Java 21 features may restrict the applicability of the framework.

To empirically evaluate the performance implications of the previously mentioned threading models, a worst-case scenario was constructed. A thread pool comprising 50 threads was tasked with generating 100,000 metrics per thread, yielding a total of 5 million operations per test container. The SQL exporter was selected as the benchmark. Under the single-threaded model, CPU utilization remained modest, with occasional spikes likely attributable to garbage collection activity (

Figure 12). Memory usage surged from approximately 200 MB to 1.2 GB, as shown in

Figure 13, and remained elevated. Notably, garbage collection failed to reclaim memory for an extended duration. Total export duration was approximately 25 min.

Contrary to expectations, replacing the single-threaded exporter with a fixed thread pool (2 or 5 threads), a cached thread pool, or a virtual thread executor led to application crashes due to memory exhaustion. This result appears to stem from differences in queuing behavior. In the single-threaded model, lightweight tasks (e.g., list insertions) are queued within the metrics reporter. In contrast, the multi-threaded models queue heavier operations, such as those involving database connections, directly in the exporter. Consequently, memory usage scales more aggressively with load in the latter case.

An alternative mitigation strategy involves adaptive metrics merging. In overload scenarios, incoming metrics of the same type could be aggregated (e.g., by computing mean execution times) rather than enqueued individually. This would reduce queue size but at the cost of metric fidelity. Such an approach is best regarded as a fallback mechanism, suitable only when complete observability is infeasible. Moreover, defining a principled threshold for initiating this behavior remains an open challenge.